Abstract

We extended characterization of mutational substitutions in the ligand-binding region of Trg, a low-abundance chemoreceptor of Escherichia coli. Previous investigations using patterns of adaptational methylation in vivo led to the suggestion that one class of substitutions made the receptor insensitive, reducing ligand-induced signaling, and another mimicked ligand occupancy, inducing signaling in the absence of ligand. We tested these deductions with in vitro assays of kinase activation and found that insensitive receptors activated the kinase as effectively as wild-type receptors and that induced-signaling receptors exhibited the low level of kinase activation characteristic of occupied receptors. Differential activation by the two mutant classes was not dependent on high-abundance receptors. Cellular context can affect the function of low-abundance receptors. Assays of chemotactic response and adaptational modification in vivo showed that increasing cellular dosage of mutant forms of Trg to a high-abundance level did not significantly alter phenotypes, nor did the presence of high-abundance receptors significantly correct phenotypic defects of reduced-signaling receptors. In contrast, defects of induced-signaling receptors were suppressed by the presence of high-abundance receptors. Grafting the interaction site for the adaptational-modification enzymes to the carboxyl terminus of induced-signaling receptors resulted in a similar suppression of phenotypic defects of induced-signaling receptors, implying that high-abundance receptors could suppress defects in induced-signaling receptors by providing their natural enzyme interaction sites in trans in clusters of suppressing and suppressed receptors. As in the case of cluster-related functional assistance provided by high-abundance receptors for wild-type low-abundance receptors, suppression by high-abundance receptors of phenotypic defects in induced-signaling forms of Trg involved assistance in adaptation, not signaling.

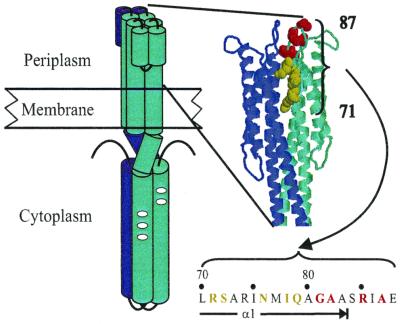

Transmembrane signaling and interreceptor interactions of the receptors that mediate chemotaxis in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium are being studied extensively. This family of closely related receptors is an attractive subject for such investigations because there is extensive functional and structural information about these proteins (15). X-ray crystallographic studies of water-soluble receptor fragments (7, 24, 32), in combination with cysteine and disulfide scanning of intact receptors (3, 4, 10, 13, 25, 26, 38), have provided a detailed model of the three-dimensional organization of a native receptor (Fig. 1). In this model, the chemoreceptor homodimer is an extended helical bundle in which the ligand-binding site is located near the membrane-distal end of the periplasmic domain, and the histidine kinase CheA and coupling protein CheW are associated in a noncovalent complex at the opposite end of the bundle, over 350 Å away, at the membrane-distal end of the cytoplasmic domain.

FIG. 1.

Chemoreceptor structure and positions of mutational substitutions in Trg. The cartoon on the left shows a chemoreceptor dimer as an extended helical bundle. Ovals near the middle of the cytoplasmic domain mark methyl-accepting sites. On the right is a model of the Trg periplasmic domain based on the structure of the Tar periplasmic domain (32) and an alignment of chemoreceptor sequences (Megan Peach, unpublished results). Below the model is the amino acid sequence of the relevant segment of Trg with the extent of helix α-1 indicated. Positions of induced-signaling (green) and reduced-signaling (red) substitutions used in this study are indicated with colored Corey-Pauling-K representations of the native side chains in the structural model and by color in the sequence.

Chemoreceptors.

Chemoreceptors function by controlling kinase activity. Interaction of an unoccupied receptor with kinase activates the enzyme, but binding of chemoattractant to the receptor lowers the activity of the interacting kinase, causing a reduction in the cellular content of the phosphorylated form of response regulator CheY, a resulting shift in the pattern of flagellar rotation, and, ultimately, an effect on motility. Ligand binding also activates a feedback loop of sensory adaptation in which methylation of specific adaptational glutamyl residues in the receptor's cytoplasmic domain causes compensatory changes that restore kinase activity to its null, receptor-activated state. Thus, signaling from a ligand-binding site has two effects on the other side of the membrane, a transient effect on kinase activity and a persistent effect on receptor methylation. Signaling neither causes (33) nor requires (12, 16, 26) dimer dissociation but instead appears to be an allosteric change within a stable dimer that initiates at the ligand-binding site, traverses the membrane, and affects both methyl-accepting sites and the kinase.

Mutational substitutions near ligand-binding sites.

Residues in and near ligand-binding sites would be expected to be involved in initiation of conformational signaling. Evidence for such involvement was provided by mutagenic analysis of a 20-residue ligand interaction region of chemoreceptor Trg of E. coli (43), a receptor that mediates taxis toward the attractants galactose and ribose via recognition of two respective sugar-occupied, periplasmic binding proteins. The analysis used in vivo patterns of adaptational methylation to identify two signaling phenotypes: (i) insensitive, characterized by little or no increase in adaptational methylation in the presence of attractant, suggesting reduced sensitivity to ligand and thus reduced signaling; and (ii) mimic ligand occupancy, characterized by increased adaptational methylation in the absence of attractant, suggesting that the mutational substitutions themselves mimicked the effect of ligand occupancy to induce signaling and that the sensory system responded as usual to persistent signaling by a compensatory increase in adaptational methylation. Alignment of chemoreceptor sequences (22) allows placement of the sites of these mutational substitutions in Trg on the known structure of the periplasmic domain of Tar (7, 32). Substitutions that confer the insensitive phenotype are near the membrane-distal end of helix α-1 and in the solvent-exposed loop that extends from α-1, reasonable locations for changes that perturb effective ligand binding (Fig. 1). Substitutions that mimic ligand occupancy are in the adjacent segment of α-1, deeper in the domain and packed on surrounding helices, in locations at which altered side chains could influence the relative positioning of interacting helices and thus induce signaling.

Low- and high-abundance receptors.

Trg is a low-abundance receptor in E. coli, present in a wild-type cell at ∼10% the content of the two high-abundance receptors, Tsr and Tar (19). In the absence of high-abundance receptors, methylation of Trg, adaptation to Trg-linked attractants, and chemotactic responses to those compounds are all detectable but inefficient (1, 17, 18, 20). These functional defects are correlated with a crucial difference between high- and low-abundance receptors, a conserved, carboxyl-terminal pentapeptide, present only in the high-abundance class, that interacts with both enzymes of adaptational modification, the methyltransferase (42) and the methylesterase-deamidase (2). Grafting a carboxyl-terminal sequence that carries the pentapeptide enzyme interaction site onto Trg creates a low-abundance receptor that is close to fully functional in methylation, adaptation, and mediation of the tactic response in the absence of high-abundance receptors (1, 18). This implies that high-abundance receptors improve Trg function by providing the enzyme interaction site in trans, creating an increased local concentration of modification enzymes in clusters of heterologous receptors (31). This notion is supported by the observations that, in the absence of high-abundance receptors, adaptational methylation and tactic efficiency of Trg are improved by overproduction of the methyltransferase (37) and that, in vitro, the inefficient methylation of a high-abundance receptor deleted for the enzyme interaction site is enhanced by the presence of the same kind of receptor carrying the site (27, 30).

Extending characterization of substitutions in the ligand-binding region of Trg.

Transmembrane signaling initiated at a ligand-binding site affects both methyl-accepting sites and kinase activity. The mutational substitutions in the ligand-binding region of Trg had been tested for effects on methyl-accepting activity (43) but not for effects on kinase activity. In addition, the mimicked occupancy receptors mediated taxis in one cellular context (low dosage in the presence of high-abundance receptors) but not in another (high dosage in the absence of high-abundance receptors) (43). The origin of this difference had not been pursued, but as we began to understand how high-abundance receptors assist functional activities of low-abundance receptor Trg, we became interested in investigating whether high-abundance receptors could also suppress mutational defects in Trg. Thus, we extended characterization of substitutions in the ligand-binding region of Trg, determining the ability of insensitive and mimic-occupancy receptors to activate the histidine kinase in vitro and assessing the influence of cellular dosage and of high-abundance receptors on the function and signaling of mutant receptors.

(Portions of this work were performed by B.D.B. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. in genetics and cell biology at Washington State University.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

CP177 (39), CP362 (39), and CP553 (9) are strains of E. coli K-12, derived from OW1, that contain, respectively, deletions of the chromosomal copies of trg; tar, tsr, tap, and trg; or tar, tsr, tap, trg, cheB, and cheR. Mutational changes in trg originally described and characterized by Yaghmai and Hazelbauer (43) were transferred, using a 1,155-bp CpoI-Eco52I fragment, from pMG2-derived plasmids to pGB1 (9), which contains the trg coding sequence fused to a tac promoter, lacIq, and bla. Transfer of mutations into a gene coding for Trg fused to the final 19 residues of Tsr was accomplished by moving the same fragment into pAL75 (18). All plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing and transformed into appropriate host strains.

In vivo assays.

Assays were performed with CP362 (lacking high-abundance receptors) or CP177 (containing high-abundance receptors) harboring pGB1-derived plasmids. Quantitative immunoblotting demonstrated that growth of such strains in minimal medium without an inducer resulted in a cellular dosage of Trg slightly lower than that produced from chromosomal trg expressed from its natural promoter (∼50%) (X. Feng and G. L. Hazelbauer, unpublished results). Induction by 20 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) resulted in cells containing sevenfold more Trg than was produced from chromosomal trg (17), making the cellular amount of the usually low-abundance receptor Trg comparable to that of a high-abundance receptor. These two levels of induction were used for both in vivo assays. Assays of chemotactic-ring formation in semisolid agar were performed essentially as described by Hazelbauer et al. (22). Plates containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml were inoculated with 1.5 μl (∼ 7.5 × 105) of logarithmic-phase, motile cells growing in tryptone broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, incubated for 12 h at 35°C in a humid environment, and photographed with an Alpha Innotech digital camera.

To assay transmembrane signaling in vivo, we used long-term exposure to attractant in a growing culture rather than stimulation by a temporal gradient in order to reduce the possibility that the patterns used to deduce features of transmembrane signaling would be affected by significantly different rates of adaptation in different cellular backgrounds (20). Four-milliliter volumes of H1 minimal salts medium (21) containing required amino acids at 1 mM, 50 μg of ampicillin/ml, IPTG as appropriate for induction to a high-abundance dosage (see above), and 20 mM sodium succinate or 20 mM ribose were inoculated to ∼2.5 × 107 cells/ml with overnight cultures in tryptone broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and incubated with agitation at 35°C. At a cell density of ∼2.5 × 108/ml, samples were removed and placed in 10% trichloroacetic acid. Material from 2.5 × 107 cells was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under conditions known to provide maximal resolution of the various methylated species of Trg (11% acrylamide, 0.073% bisacrylamide; pH 8.2) (23) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Trg serum under conditions in which the intensity of staining of the bands was a linear function of the amount of protein. Since signaling assays involve comparison of cells grown in different cultures, the amount of Trg, and thus the intensities of the stained bands under unstimulated (succinate-grown) or stimulated (ribose-grown) conditions, were not always the same. However, for all the comparisons shown in the figures in this study, adjustment of the amount of sample loaded on the gel confirmed that the differences seen in the figures (for which the same amount of cellular material was loaded for all strains and conditions) were not a function of the amount of stained Trg in a sample.

For cells lacking high-abundance receptors, our anti-Trg serum was sufficiently specific that Trg was the only protein visible in the immunoblots of whole-cell samples. However, the antiserum reacts with high-abundance receptors (36), consistent with extensive conservation of sequence in the cytoplasmic domains (5), and thus there was a problem in specific detection of Trg in cells containing high-abundance receptors, the multiple forms of which have electrophoretic mobilities very similar to those for the various forms of Trg. For cells in which Trg was induced to a level of expression equivalent to that of the high-abundance receptors, the problem could be overcome since the antiserum has an approximately 10-fold higher sensitivity for Trg than for Tsr or Tar (36), and thus we could adjust the ratio of sample to antiserum to display only Trg bands on immunoblots. At the low-abundance level of Trg expression in the presence of high-abundance receptors, such a differential display was not possible, and thus the modification-based signaling assay could not be performed under this particular set of conditions.

In vitro kinase assay.

Trg-containing membranes were prepared from CP553 cells harboring an appropriate plasmid and stored at −70°C (1). Trg content (usually ∼10% of the total protein) was determined by quantitative immunoblotting with purified Trg as a standard, using an AlphaImager 950 digital camera system (Alpha Innotech Corporation) and ImageQuant software (version 4.2; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). As described by Barnakov et al. (1), CheA was mixed with the accessory protein CheW, the response regulator CheY, and isolated membrane containing either no receptor, wild-type Trg, or a mutant receptor. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h to allow formation of receptor-kinase complexes, radiolabeled ATP was added, and the reaction was stopped after 5 s. Relative levels of phospho-CheY were determined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. Under the conditions used, production of phospho-CheY was a direct reflection of CheA activity.

RESULTS

Kinase activation by mutant forms of Trg.

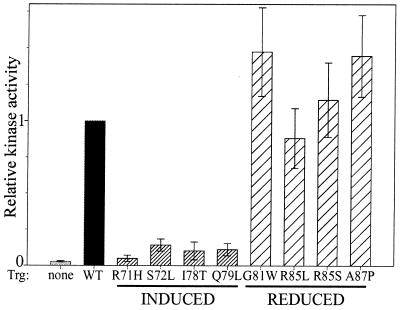

Yaghmai and Hazelbauer (43) interpreted patterns of in vivo covalent modification to indicate that one class of mutational substitutions in the ligand interaction region of Trg induced transmembrane signaling and another class reduced signaling. We tested this notion by examining activation of the CheA kinase in vitro by a representative set of these mutant receptors, four from the insensitive class and four from the mimic-ligand-occupancy class (Fig. 2). A substituted receptor characterized as insensitive because it exhibited little or no change in adaptational methylation upon stimulation with ligand might do so because its cytoplasmic domain was generally disrupted and thus not available for effective adaptational modification or because it was specifically and locally perturbed near the ligand-binding site. Interaction of CheA and the coupling protein CheW with wild-type Trg increases kinase activity approximately 100-fold over its low level in the absence of receptor (1). All four insensitive receptors provided approximately the same substantial activation (Fig. 2), indicating that their cytoplasmic domains were indistinguishable from that of the wild type in this function and supporting the notion that those mutant receptors were perturbed only in the region of the ligand-binding site near the sites of substitution. Unfortunately, we could not extend the characterization to effects of ligand occupancy on kinase activity in the in vitro system because the very weak affinity of Trg for its binding protein ligands (dissociation constants, ∼0.5 mM [44]) made addition of saturating ligand technically infeasible.

FIG. 2.

Activation of kinase by wild-type and mutant forms of Trg. Membranes containing no chemoreceptors (none), wild-type Trg (WT), or a mutant form of Trg (designated by the wild-type amino acid, residue number, and replacing amino acid) were assayed for activation of CheA by measuring levels of phospho-CheY in a coupled system. Values were normalized to those for the wild-type receptor in the same experiment and are averages of six determinations (two trials each on three different membrane preparations) ± standard error. Labels at the bottom of the figure indicate induced-signaling (INDUCED) or reduced-signaling (REDUCED) forms of Trg.

If mutational substitutions that increase in vivo receptor methylation in the absence of ligand induce the same conformational signaling as ligand binding, then receptors containing those substitutions should exhibit in vitro the same reduced activation of kinase characteristic of ligand-occupied receptors (6). Alternatively, the substitutions might alter the receptor in a way that results in increased methyl-accepting activity without reducing kinase activation, as observed in some cases of cysteine-substituted and oxidatively cross-linked forms of receptor (11). All four substitutions thought to mimic ligand occupancy reduced kinase activation by Trg (Fig. 2). Thus, those substitutions in the periplasmic domain had a transmembrane effect on the activity of the cytoplasmic domain. The effect was the same as if ligand were bound. It seems unlikely that this effect is a nonspecific disruption of the domain on the other side of the membrane since the same substitutions increase the in vivo methyl-accepting activity of the cytoplasmic domain. In vitro, the transmembrane mutational effect might be to reduce activation without perturbing the complex with the kinase, the common view of the way ligand occupancy affects the enzyme (15), or it might affect complex assembly-disassembly, a recently noted effect of ligand occupancy (29). In either case, the substitutions in the periplasmic domain have transmembrane effects on the cytoplasmic domain that mimic those created by ligand occupancy. Taken together, the in vitro and in vivo data prompt us to refer to the mutant proteins as reduced-signaling and induced-signaling receptors, respectively.

Signaling mutants in different cellular contexts.

The original study of mutational substitutions in the ligand-binding region of Trg indicated that the ability of mimicked-occupancy receptors to mediate chemotaxis was a function of cellular context (43). Cells containing chromosomal copies of the genes for the high-abundance receptors and of trg coding for a mimicked-occupancy mutant exhibited significant Trg-mediated chemotaxis, but cells containing a higher dosage of the same mutant Trg, produced from multiple copies of a plasmid-borne gene, and lacking high-abundance receptors exhibited no tactic response. This difference could have reflected effects of Trg dosage, high-abundance receptors, or both. Thus, we investigated the influence of receptor dosage and of high-abundance receptors on in vivo activities of Trg proteins containing representative substitutions in the ligand interaction region, six previously characterized as inducing signaling and six known to reduce signaling. We utilized plasmid-borne copies of trg under the tight control of a modified lac promoter-operator, appropriate levels of inducer, and host cells containing or lacking high-abundance receptors to test wild-type Trg and the 12 mutant receptors for their ability to mediate chemotaxis in four different cellular contexts: (i) Trg at a low-abundance dosage in cells lacking high-abundance receptors, (ii) Trg at a high-abundance dosage in cells lacking high-abundance receptors, (iii) Trg at a low-abundance dosage in cells containing high-abundance receptors Tar and Tsr, and (iv) Trg at a high-abundance dosage in cells containing the two high-abundance receptors. To make direct comparisons of responses in the four different contexts, we assayed taxis by monitoring formation of chemotactic rings in semisolid agar plates containing an attractant sugar as the sole source of carbon and energy. Of the available assays, only that for ring formation is sufficiently sensitive to detect the weak Trg-mediated responses of cells lacking high-abundance receptors (17). Experience with many trg mutants has shown us that this assay is a sensitive and reliable means of characterizing functional activities and mutational defects in Trg (see, for instance reference 17). Cells performing Trg-mediated taxis form distinct rings. The better the taxis, the faster the ring moves. Cells incapable of Trg-mediated taxis form fuzzy disks lacking a distinct boundary. The rate of movement of that disk is unrelated to the Trg-mediated response. The mutant and wild-type proteins were assayed for transmembrane signaling in vivo in all contexts except condition iii, in which the low ratio of Trg to heterologous but structurally related chemoreceptors prohibited specific detection of patterns of adaptational modification of Trg by immunoblotting (see Material and Methods).

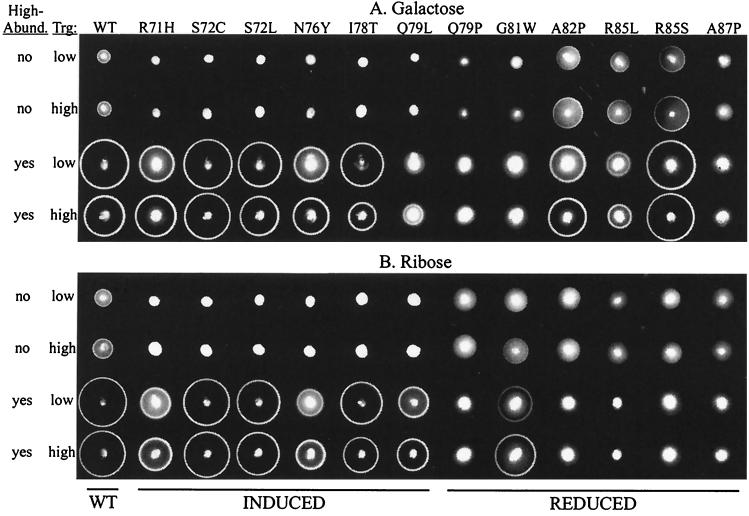

Mediation of taxis.

Altering the cellular content of the wild-type (17) or mutant forms of Trg from their characteristic low abundance level to a high abundance level had little effect on their ability to mediate taxis toward galactose (Fig. 3A) or ribose (Fig. 3B). In Fig. 3, the upper two rows and lower two rows of the panels each represent paired sets of responses mediated by the wild type and each of the mutant forms of Trg in cellular contexts that differed only in the dosage of that receptor. In different cellular contexts and for different mutant receptors, responses ranged from essentially wild type to not detectable, but for any particular receptor a change in dosage from low abundance (upper member of the pair) to high abundance (lower member) had little or no effect on ring sharpness or rate of movement. In contrast, the presence of high-abundance receptors had a profound effect on the functional ability of induced-signaling receptors. In cells lacking high-abundance receptors, all induced-signaling receptors were incapable of mediating formation of chemotactic rings in response to galactose (Fig. 3A) or ribose (Fig. 3B). However, those same receptors mediated formation of distinct rings in the presence of high-abundance receptors (Fig. 3, lower two rows of each panel), the only exception being response to galactose mediated by Trg-Q79L, a receptor previously shown to exhibit a differential defect in responses to the two Trg-mediated attractants (44). Substitutions that reduce signaling can have equivalent and drastic effects on the responses to both Trg-linked attractants, as seen for Q79P and A87P, or can affect the two responses differentially (44), as observed for G81W (which has a greater effect on the response to galactose) as well as for A82P, R85L, and R85S (which have a greater effect on the response to ribose). The former situation would occur if the altered side chain participated equally in productive interaction with both sugar-binding proteins recognized by Trg, and the latter would occur if the side chain were more important for one of the interactions. Responses mediated by reduced-signaling receptors that were undetectable in the absence of high-abundance receptors remained undetectable in their presence, a pattern quite different from the major improvement in response observed for the induced-signaling receptors. Detectable responses mediated by reduced-signaling receptors in the absence of high-abundance receptors were quantitatively improved by the presence of the high-abundance receptors, paralleling the effect observed for wild-type Trg (17).

FIG. 3.

Chemotaxis mediated by wild-type and mutant forms of Trg. Shown are representative responses mediated by Trg in its wild-type (WT) or signaling-mutant forms (designated as in the legend to Fig. 2) expressed from plasmid-borne genes. Cells were assayed for the ability to form chemotactic rings on semisolid agar plates containing galactose (A) or ribose (B). Assays were performed on cells lacking or containing the high-abundance receptors (designated in the first column as “no” or “yes,” respectively) and containing each respective form of Trg expressed to a level characteristic of a low- or high-abundance receptor (designated in the second column as “low” or “high,” respectively). Images were recorded 12 h after inoculation and incubation at 35°C. Labels at the bottom of the figure indicate wild-type (WT), induced-signaling (INDUCED), or reduced-signaling (REDUCED) forms of Trg.

Signaling phenotypes.

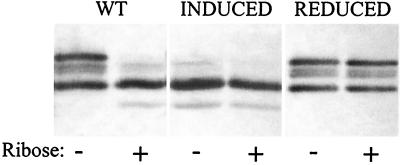

We assessed effects of cellular context on the signaling phenotype by using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting to determine in vivo patterns of adaptational modification (43). In immunoblots, Trg appears as an array of bands corresponding to different numbers of covalent modifications per polypeptide chain (34, 35). Receptors with glutamates at all methyl-accepting sites migrate most slowly, and, with the exception of one methyl-accepting position among the five in Trg, each added methyl group results in a characteristic increase in electrophoretic mobility. As in other chemoreceptors, two methyl-accepting glutamates in Trg are created by deamidation of gene-encoded glutamines (35). Deamidation is catalyzed by the methylesterase and controlled by the same factors as demethylation. An amide group has the same effect on electrophoretic migration as a methyl ester, resulting in a more rapidly migrating species (35). Figure 4 shows representative examples of signaling assays, comparing unstimulated and ribose-stimulated cells, performed under the conditions used by Yaghmai and Hazelbauer (43). For wild-type Trg (leftmost pair of lanes), the pattern for unstimulated cells has four bands, designated bands 1 (highest) through 4 (lowest), corresponding to a distribution of, on average, ∼1.5 methylated or amidated sites per receptor (34, 35). In cells that have adapted to persistent stimulation, methylation has increased and the pattern is dominated by the fastest-migrating, most modified band (band 4) of the original set. This shift indicates signaling from the periplasmic to the cytoplasmic domain. Trg containing a substitution that induced signaling (Fig. 4, middle pair) exhibits this shift even in the absence of ligand. In contrast, the pattern of a reduced-signaling receptor (Fig. 4, rightmost pair) is indistinguishable from that of the wild type in the absence of ligand and is essentially unchanged in its presence.

FIG. 4.

Signaling in vivo assessed in an immunoblot assay. Modification state was used to assay transmembrane signaling in vivo by a wild-type (WT), induced-signaling (INDUCED), or reduced-signaling (REDUCED) form of Trg. Cells lacking chromosomal copies of tsr, tar, tap, and trg but harboring a plasmid coding for one of the forms of Trg were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium in the absence (−) or presence (+) of excess ribose. Samples from each actively growing culture were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-Trg serum. The forms of Trg were expressed at levels significantly higher than the level characteristic of a high-abundance receptor approximating the cellular content used in reference 43. The figure shows the region of the immunoblots containing chemoreceptor bands; the lowest band in the leftmost lane has an apparent Mr of ∼60,000.

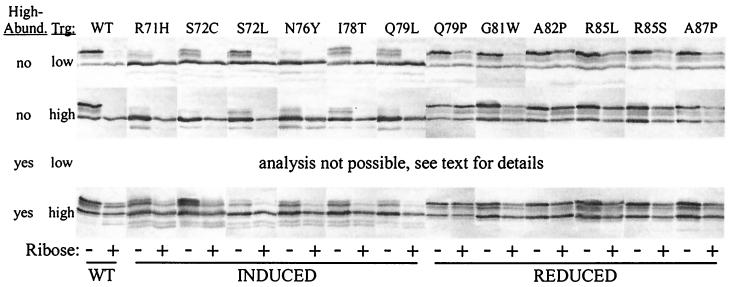

Cellular context had little influence on signaling assay patterns for reduced-signaling receptors but had discernable effects on induced-signaling receptors (Fig. 5). For reduced-signaling receptors, the patterns observed in the absence of stimulation were very similar to the pattern for unstimulated, wild-type Trg and were shifted little, if at all, upon stimulation. The greatest effect was for ribose stimulation of Trg-G81W, consistent with the ability of this mutant receptor to mediate a tactic response to ribose. Neither changing the dosage of reduced-signaling receptors nor introducing high-abundance receptors significantly altered either the patterns obtained in the absence of stimulation or the lack of a significant shift in the presence of ligand. For induced-signaling receptors, signaling assay patterns in the absence of stimulation all exhibited a characteristic shift toward more rapidly migrating, more adaptationally modified bands (Fig. 5). The degree of shift, and presumably the degree of signaling, correlated with the particular mutational substitution. In all cellular contexts, stimulation of induced-signaling receptors by ligand resulted in an additional shift to faster-migrating, more highly modified forms from the already shifted pattern of the unstimulated receptor, indicating that induced-signaling receptors were capable of transmembrane signaling in response to occupancy by their natural ligands. Evidence for such signaling was not clear in the signaling assays performed in the original study of these mutant receptors (see reference 43 and the example in Fig. 4), probably because those assays were done with cells containing receptor dosages at least 25-fold above a normal high-abundance dosage and thus had an abnormal receptor-modification enzyme stoichiometry. Increasing the dosage of induced-signaling receptors from a low abundance to a high abundance level resulted in only a modest shift to more-rapidly migrating electrophoretic forms, consistent with the lack of a discernible effect of dosage on the tactic response. In cells containing high-abundance receptors, the electrophoretic patterns of induced-signaling receptors all exhibited an increased number of electrophoretic forms (Fig. 5, compare rows 2 and 4), indicating that adaptational covalent modification was more active in the cells in which the mutant receptors were able to mediate taxis. This correlation is likely to reflect the crucial contribution of high-abundance receptors in functionally assisting induced-signaling forms of Trg (see Discussion).

FIG. 5.

Signaling by wild-type and mutant forms of Trg. The forms of Trg analyzed in the study shown in Fig. 3 were tested for signaling in vivo, as described in the legend to Fig. 4, by immunoblotting of cells grown in minimal medium in the absence (−) or presence (+) of excess ribose. Assays were performed on cells lacking or containing the high-abundance receptors (designated in the first column as “no” or “yes,” respectively) and containing each respective form of Trg expressed to a level characteristic of a low- or high-abundance receptor (designated in the second column as “low” or “high,” respectively). Recognition of conserved regions of the high-abundance receptors by anti-Trg serum prohibited specific staining of Trg expressed at a low-abundance level in cells containing the high-abundance receptors. Labels are as for Fig. 3.

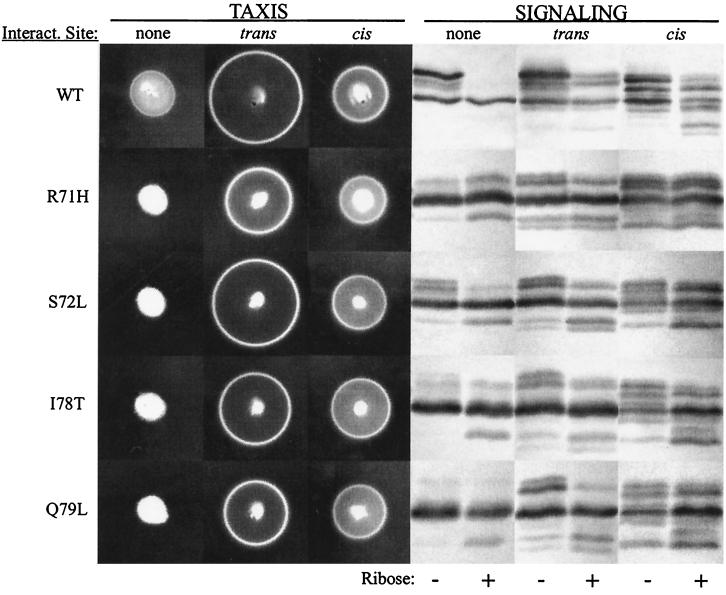

Effects of the enzyme interaction site.

The inefficient taxis and adaptational modification mediated by the wild-type form of the low-abundance receptor Trg in cells lacking high-abundance receptors are significantly improved by addition to Trg of the 19-residue, carboxyl-terminal segment (from a high-abundance receptor) that contains the pentapeptide site for interaction with the enzymes of adaptational modification (1, 18). Since the presence of high-abundance receptors greatly improved the function of induced-signaling forms of Trg, we examined the effects of introducing the interaction site at the carboxyl terminus of induced-signaling receptors. Four such constructs were created and assayed for their ability to mediate taxis and for patterns of covalent modification in the signaling assay (Fig. 6). Grafting the enzyme interaction site onto induced-signaling forms of Trg conferred the ability to mediate taxis in the absence of high-abundance receptors and resulted in an increase in the number of electrophoretic forms seen in the immunoblot assay. Thus, the presence of the enzyme interaction site exerted a corrective influence on induced-signaling forms of Trg whether present in trans (on high-abundance receptors) or in cis (grafted to the carboxyl terminus).

FIG. 6.

Effects on induced-signaling forms of Trg of the interaction site for the enzymes of adaptational modification provided in trans or in cis. Abilities to mediate taxis and signaling phenotypes of wild-type (WT) and four induced-signaling forms of Trg are shown in cells lacking high-abundance receptors and, thus, lacking the carboxyl-terminal sequence that interacts with the enzymes of adaptational modification (none), in cells containing high-abundance receptors and thus providing the interaction sequence in trans relative to Trg (trans), and in cells containing Trg proteins with carboxyl-terminal extensions comprising the final 19 residues of the high-abundance receptor Tsr (18) and thus having the interactions sequence in cis relative to Trg (cis). Assays were performed as detailed in the legends to Fig. 3 and 5 and were done on cells with Trg expressed at a high-abundance dosage. Signaling assays were performed with (+) or without (−) ribose.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we extended our investigation of mutational substitutions in the ligand interaction region of chemoreceptor Trg to in vitro assays of kinase activation and to characterization of the effects of cellular context on mutational phenotype. Results of the kinase assays supported the notion that the two classes of substitutions induced or reduced signaling. The effects of cellular context revealed that the phenotypic effects of one class of substitutions were suppressed by heterologous, high-abundance receptors that acted to enhance adaptational modification of the mutant, low-abundance receptors, probably as the result of physical proximity and receptor clustering

Signaling mutants.

The notion that substitutions in the ligand interaction region of Trg induced or reduced signaling was based exclusively on patterns of receptor modification in vivo (43). An important test was to determine the effects of the mutations on kinase activation, a determination that required an in vitro assay. The results (Fig. 2) confirmed and strengthened the definition of the two phenotypic classes, one that reduced signaling and the other that induced signaling, and indicated that differential activation of kinase by the two mutant classes was not dependent on high-abundance receptors. The effects of cellular context were also consistent with the two postulated classes of signaling mutants. Reduction of signaling by disruption of effective ligand binding should not have been corrected by the presence of high-abundance receptors, and it was not (Fig. 3 and 5). In contrast, persistent signaling generated by a mutational substitution could disrupt the sensory system if methylation were not sufficiently efficient to balance that signaling. In this light, the inability of induced-signaling receptors to mediate taxis in the absence of high-abundance receptors and the much-improved function of the mutant receptors in their presence can be readily understood as a reflection of the inefficiency of adaptational modification in the former context and of its efficiency in the latter.

Since Trg is a low-abundance receptor, it was important to determine whether the phenotypes of signaling mutants would be affected by receptor dosage. We found that changing the cellular content of the mutant forms of Trg from one approximating the natural dosage of a low-abundance receptor to one approximating the dosage of a high-abundance receptor had only modest effects for a few mutants. This lack of a substantial effect of cellular dosage parallels observations that the efficiency of wild-type Trg in mediating taxis is minimally affected over a wide range of dosages (17). The mutant receptors for which we observed modest improvement in function at a higher cellular dosage were those with differential defects in responses to galactose and ribose. These substitutions are likely to reduce, but not eliminate, effective binding to the affected ligand (44), so it is plausible that an ∼10-fold increase in receptor dosage could increase that interaction and thus improve taxis.

Covalent modification, signaling, and taxis.

The patterns exhibited by reduced-signaling receptors in the signaling assay correlated directly with the ability of these receptors to mediate taxis. Five reduced-signaling receptors exhibited little, if any, shift to more highly methylated forms in the presence of stimulating ribose, and those same five were unable to mediate taxis toward that sugar. One reduced-signaling receptor (Trg-G81W) exhibited detectable, although reduced, signaling in response to ribose, and it mediated detectable taxis. For the induced-signaling receptors, the situation was more complicated. Signaling, as detected by a significant shift to faster-migrating electrophoretic forms in the persistent presence of attractant, was observed for all six induced-signaling receptors in all cellular contexts that could be examined. However, these receptors mediated taxis only in the presence of high-abundance receptors (Fig. 3) or when provided with a carboxyl-terminal tail carrying the interaction site for the enzymes of adaptational covalent modification (Fig. 6). For each induced-signaling receptor, effective mediation of taxis was correlated with an increased number of different electrophoretic forms in the signaling assay (Fig. 5 and 6). This can be explained by a greater efficiency of covalent modification of induced-signaling receptors in cells containing the enzyme interaction site on heterologous receptors in a cluster or on the mutant receptor itself. The reduced number of electrophoretic forms in the absence of the enzyme interaction site is reminiscent of Trg with alanines at the positions of glutamines usually deamidated by the methylesterase-deamidase to create methyl-accepting glutamates (34). The similarity suggests that the reduced number of electrophoretic forms of induced-signaling receptors in the absence of enzyme interaction sites reflects incomplete deamidation, resulting in fewer methyl-accepting sites. It is likely that deamidation of Trg would be incomplete because the reaction is inefficient in the absence of the enzyme interaction site (2), and persistent inhibition of the kinase by mutational signaling would result in low cellular levels of phosphorylated and, therefore, activated deamidase.

Slow and probably incomplete adaptational modification in the absence of the enzyme interaction site is likely to be the origin of the inability of induced-signaling receptors alone to mediate taxis. In the absence of high-abundance receptors, wild-type Trg is capable of mediating detectable taxis (17, 22) and of adapting to low levels of receptor occupancy, although at a reduced rate (20). At higher levels of occupancy, adaptation times are greatly extended and it appears that the native receptor, lacking an enzyme interaction site, is not capable of becoming sufficiently methylated to balance the signal generated by ligand binding (20). This is likely the situation for the induced-signaling receptors, in which the mutational substitutions generate a signal too strong to be balanced by the relatively inefficient methylation of a receptor lacking the enzyme interaction site. By this reasoning, it is easy to understand the correlation between the larger array of electrophoretic forms, an indication of more efficient adaptational modification, with the ability of induced-signaling receptors to mediate chemotaxis.

Functional interactions among heterologous receptors.

Recently there has been much interest in chemoreceptor clustering (31) and the possibility that clustering and physical interaction between receptors is crucial for the functions of receptor sensitivity, signaling, and signal amplification (8, 14, 24, 28). There are only a few documented examples of functional interactions between receptors in vivo, and all concern the dependence of low-abundance receptors on high-abundance receptors for effective function (17, 18, 20, 40, 41). The present study extends this set of data by providing examples in which high-abundance receptors suppress, via adaptational improvement, mutational defects in a specific class of mutant forms of the low-abundance receptor Trg. This mutational suppression provided independent evidence for adaptation-related, functional interaction between heterologous chemoreceptors.

In the absence of high-abundance receptors, the induced-signaling forms of Trg were unable to mediate chemotaxis, but the presence of high-abundance receptors made the mutant receptors functional (Fig. 3). This was not a general effect on all types of Trg signaling mutants, since the phenotype of reduced-signaling mutants was unaltered by the presence of high-abundance receptors. The inability of induced-signaling forms of Trg to mediate taxis was also corrected by introducing the interaction site for the enzymes of adaptational modification at the carboxyl terminus of the mutant receptors (Fig. 6). This implies that suppression of the mutant phenotype of induced-signaling receptors by high-abundance receptors was mediated by provision of the enzyme interaction site naturally present at the carboxyl terminus of high-abundance receptors. Enhanced adaptational modification of mutant, low-abundance receptors by the presence of high-abundance receptors carrying interaction sites for the modification enzymes indicates that the heterologous receptors must be in physical proximity. As for functional interactions in vivo between wild-type forms of low-abundance and high-abundance receptors (17, 18, 41), suppression of mutational defects in Trg by high-abundance receptors implicates receptor interaction and clustering (31) in adaptation rather than signaling.

In contrast, although signaling from a low-abundance receptor like Trg must involve significant amplification to have an effect on cellular behavior in the presence of an excess of high-abundance receptors, there is as yet no evidence that signaling from the low-abundance receptor Trg is dependent on other receptors. In cells lacking high-abundance receptors, binding of ligand to Trg generates signaling that effectively alters cellular behavior even though adaptation is drastically inefficient (20). In vitro, Trg activates the kinase in the absence of any heterologous receptor (1), and the present study indicates that mutationally induced signaling from the periplasmic domain of Trg reduces kinase activity without assistance from high-abundance receptors. In summary, investigations of both mutant and wild-type forms of low-abundance receptors emphasize the importance of heterologous, high-abundance receptors for effective adaptation, not for excitatory signaling. Receptor proximity and, presumably, clustering have an important role in effective sensory adaptation of low-abundance receptors. A role in signaling has yet to be documented.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alexander Barnakov and Ludmilla Barnakova for purified CheA, CheW, CheY, and Trg; Xiuhong Feng for guidance on the kinase assay; Megan Peach for her model of the Trg periplasmic domain; and Douglas Banks and Angela Lilly for introduction of signaling mutations into the hybrid gene coding for Trgt and for initial characterization of those constructs.

This work was supported in part by research grant GM29963 and Biotechnology Training Grant T32 GM08336 from the National Institutes of General Medical Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnakov A N, Barnakova L A, Hazelbauer G L. Comparison in vitro of a high- and a low-abundance chemoreceptor of Escherichia coli: similar kinase activation but different methyl-accepting activities. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6713–6718. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6713-6718.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnakov A N, Barnakova L A, Hazelbauer G L. Efficient adaptational demethylation of chemoreceptors requires the same enzyme-docking site as efficient methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10667–10672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass R B, Coleman M D, Falke J J. Signaling domain of the aspartate receptor is a helical hairpin with a localized kinase docking surface: cysteine and disulfide scanning studies. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9317–9327. doi: 10.1021/bi9908179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bass R B, Falke J J. Detection of a conserved α-helix in the kinase-docking region of the aspartate receptor by cysteine and disulfide scanning. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25006–25014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bollinger J, Park C, Harayama S, Hazelbauer G L. Structure of the Trg protein: homologies with and differences from other sensory transducers of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3287–3291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkovich K A, Alex L A, Simon M I. Attenuation of sensory receptor signaling by covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6756–6760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowie J U, Pakula A A, Simon M I. The three-dimensional structure of the aspartate receptor from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1995;51:145–154. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994010498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray D, Levin M D, Morton-Firth C J. Receptor clustering as a cellular mechanism to control sensitivity. Nature. 1998;36:11851–11857. doi: 10.1038/30018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burrows G G, Newcomer M E, Hazelbauer G L. Purification of receptor protein Trg by exploiting a property common to chemotactic transducers of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17309–17315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler S L, Falke J J. Cysteine and disulfide scanning reveals two amphiphilic helices in the linker region of the aspartate chemoreceptor. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10746–10756. doi: 10.1021/bi980607g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chervitz S A, Falke J J. Lock on/off disulfides identify the transmembrane signaling helix of the aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24043–24053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chervitz S A, Lin C M, Falke J J. Transmembrane signaling by the aspartate receptor: engineered disulfides reveal static regions of the subunit interface. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9722–9733. doi: 10.1021/bi00030a010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danielson M A, Bass R B, Falke J J. Cysteine and disulfide scanning reveal a regulatory α-helix in the cytoplasmic domain of the aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32878–32888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duke T A J, Bray D. Heightened sensitivity of a lattice of membrane receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10104–10108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falke J J, Bass R B, Butler S L, Chervitz S A, Danielson M A. The two-component signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis: a molecular view of signal transduction by receptors, kinases, and adaptation enzymes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:457–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falke J J, Koshland D E., Jr Global flexibility in a sensory receptor: a site-directed cross-linking approach. Science. 1987;237:1596–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.2820061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng X, Baumgartner J W, Hazelbauer G L. High- and low-abundance chemoreceptors in Escherichia coli: differential activities associated with closely related cytoplasmic domains. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6714–6720. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6714-6720.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng X, Lilly A A, Hazelbauer G L. Enhanced function conferred on low-abundance receptor Trg by a methyltransferase-docking site. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3164–3171. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3164-3171.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazelbauer G L, Engström P. Multiple forms of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins distinguished by a factor in addition to multiple methylation. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:35–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.35-42.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazelbauer G L, Engström P. Parallel pathways for transduction of chemotactic signals in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1980;238:98–100. doi: 10.1038/283098a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazelbauer G L, Mesibov R E, Adler J. Escherichia coli mutants defective in chemotaxis toward specific chemicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;64:1300–1307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazelbauer G L, Park C, Nowlin D M. Adaptational “crosstalk” and the crucial role of methylation in chemotactic migration by Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1448–1452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kehry M R, Engström P, Dahlquist F W, Hazelbauer G L. Multiple covalent modifications of Trg, a sensory transducer of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5050–5055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K K, Yokota H, Kim S-H. Four-helical-bundle structure of the cytoplasmic domain of a serine chemotaxis receptor. Nature. 1999;400:787–792. doi: 10.1038/23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee G L, Burrows G G, Lebert M R, Dutton D P, Hazelbauer G L. Deducing the organization of a transmembrane domain by disulfide cross-linking: the bacterial chemoreceptor Trg. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29920–29927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee G L, Lebert M R, Lilly A A, Hazelbauer G L. Transmembrane signaling characterized in bacterial chemoreceptors by using sulfhydryl cross-linking in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3391–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Moual H, Quang T, Koshland D E., Jr Methylation of the Escherichia coli chemotaxis receptors: intra- and interdimer mechanisms. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13441–13448. doi: 10.1021/bi9713207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levit M N, Liu Y, Stock J B. Stimulus response coupling in bacterial chemotaxis: receptor dimers in signalling arrays. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:459–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li G, Weis R M. Covalent modification regulates ligand binding to receptor complexes in the chemosensory system of Escherichia coli. Cell. 2000;100:357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Li G, Weis R M. The serine chemoreceptor from Escherichia coli is methylated through an inter-dimer process. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11851–11857. doi: 10.1021/bi971510h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddock J R, Shapiro L. Polar location of the chemoreceptor complex in the Escherichia coli cell. Science. 1993;259:1717–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.8456299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milburn M V, Prive G G, Milligan D L, Scott W G, Yeh J, Jancaric J, Koshland D E, Jr, Kim S-H. Three-dimensional structures of the ligand-binding domain of the bacterial aspartate receptor with and without a ligand. Science. 1991;254:1342–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1660187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milligan D L, Koshland D E., Jr Site-directed cross-linking. Establishing the dimeric structure of the aspartate receptor of bacterial chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6268–6275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowlin D M, Bollinger J, Hazelbauer G L. Site-directed mutations altering methyl-accepting residues of a sensory transducer protein. Proteins. 1988;3:102–112. doi: 10.1002/prot.340030205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowlin D M, Bollinger J, Hazelbauer G L. Sites of covalent modification in Trg, a sensory transducer of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6039–6045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowlin D M, Nettleton D O, Ordal G W, Hazelbauer G L. Chemotactic transducer proteins of Escherichia coli exhibit homology with methyl-accepting proteins from distantly related bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:262–266. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.262-266.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okumura H, Nishiyama S-I, Sasaki A, Homma M, Kawagishi I. Chemotactic adaptation is altered by changes in the carboxy-terminal sequence conserved among the major methyl-accepting chemoreceptors. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1862–1868. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1862-1868.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pakula A A, Simon M I. Determination of transmembrane protein structure by disulfide cross-linking: the Escherichia coli Tar receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4144–4148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park C, Hazelbauer G L. Mutations specifically affecting ligand interaction of the Trg chemosensory transducer. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:101–109. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.101-109.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Springer M S, Goy M F, Adler J. Sensory tranduction in Escherichia coli: two complementary pathways of information processing that involve methylated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3312–3316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weerasuriya S, Schneider B M, Manson M D. Chimeric chemoreceptors in Escherichia coli: signaling properties of Tar-Tap and Tap-Tar hybrids. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:914–920. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.914-920.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu J, Li J, Li G, Long D G, Weis R M. The receptor binding site for the methyltransferase of bacterial chemotaxis is distinct from the sites of methylation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4984–4993. doi: 10.1021/bi9530189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaghmai R, Hazelbauer G L. Ligand occupancy mimicked by single residue substitutions in a receptor: transmembrane signaling induced by mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7890–7894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaghmai R, Hazelbauer G L. Strategies for differential sensory responses mediated through the same transmembrane receptor. EMBO J. 1993;12:1897–1905. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]