Abstract

The m6A methylation is the most numerous modification of mRNA in mammals, coordinated by RNA m6A methyltransferases, RNA m6A demethylases, and RNA m6A binding proteins. They change the RNA m6A methylation level in their specific manner. RNA m6A modification has a significant impact on lipid metabolic regulation. The “writer” METTL3/METTL14 and the “eraser” FTO can promote the accumulation of lipids in various cells by affecting the decomposition and synthesis of lipids. The “reader” YTHDF recognizes m6A methylation sites of RNA and regulates the target genes’ translation. Due to this function that regulates lipid metabolism, RNA m6A methylation plays a pivotal role in metabolic diseases and makes it a great potential target for therapy.

Keywords: METTL3, obesity, FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) gene, M6A, lipid

Introduction

Lipid metabolism exerts a profound impact on the maintenance of human physiology and health status. Adipose tissue is an important site for lipid storage, and energy homeostasis (1, 2). It is important to understand the mechanisms involved in adipose tissue development (3). Adipogenesis of the white and brown adipocytes is regulated by several endocrine hormones (1, 3). Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) pro-obesity rs1421085 T-to-C single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) shifts differentiation programming towards white adipocytes in subcutaneous fat (4). Meanwhile in community, unhealthy lifestyles such as nutrient surplus and unhealthy eating patterns (5) act as the main reason for the high incidence of lipid metabolism disorder. Furthermore, types of diseases caused by abnormal lipid metabolisms like diabetes (6), hyperlipidaemia (7), cardiovascular disease (8, 9), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (10) are becoming more and more pervasive all over the world. Therefore, there is a great desire to deepen the understanding of the regulation of lipid metabolism.

In mammals, the m6A methylation is the most numerous modification of mRNA and accounts for more than sixty percent of all RNA modifications (11, 12). The RNA m6A modification is a kind of methylation modification positioned at the nitrogen atom in the sixth position of adenosine (13). The process of RNA m6A methylation is dynamically and reversibly coordinated by m6A demethylases, m6A methyltransferases, and m6A binding proteins, which are also referred to as “Writer”, “Eraser”, and “Reader”, respectively (14). The writers methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14), and Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP) have m6A methylation activity to catalyze m6A modification (15). Demethylases are predominantly made out of ALKB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) and FTO (16), catalyzing the demethylation process (17). Furthermore, m6A binding proteins are found principally in the YT521-B homology (YTH) family (18), which have the potency to recognize and specifically bind to m6A-modified transcripts (19). All kinds of RNA m6A methylation regulators are involved in different physiological processes, while many remain unknown.

In this article, we introduce the novel RNA modification and its regulatory function for RNA. We summarize the main regulators of RNA m6A methylation and describe their function and regulatory mechanism toward mRNA. The possible target gene by which RNA m6A methylation regulators affect lipid metabolism is claimed. Finally, we reviewed the RNA m6A methylation regulators on the NAFLD, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases and its regulating pathway to provide some reference to the clinical prevention, diagnosis, and therapy research in lipid metabolism-related diseases.

Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of RNA m6A methylation

M6A methylation is a newly discovered epigenetic regulatory mechanism in recent years. Among the more than 170 RNA modifications (20), m6A modification accounts for a large proportion in eukaryocyte (21). It is a methylation substitution reaction that takes place on the sixth nitrogen atom of the RNA molecule adenosine, which is observed enriching in 3’UTR and consensus motif RRACH in coding region (22, 23).

M6A methylation is essential in determining the fate of RNA, showing a regulatory function in multiple mRNA biological processes. Firstly, it can regulate the stability of mRNA. Facts that mRNA with lower m6A methylation level had longer half-life was first revealed in 1978 (24). The m6A reader YTHDF2 can recognize methylation sites in the coding region of mRNA and destabilized mRNA (25, 26) while, the newly identified reader Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins (IGFBP) recognized m6A in 3‘UTR inversely make the mRNA more stable (27, 28). The opposite regulatory effect may account for the different recognizing mRNA sites. Secondly, m6A facilitates the initiation of the translation process of mRNA. After reading the m6A methylation site, the m6A reader like YTHFD1/3 can recruit eIF3 to connect to mRNA. In addition, m6A at 5‘UTR can directly connect to eIF3 to enhance mRNA translation (29–31). Furthermore, it also regulates mRNA splicing, processing, and nuclear export (32, 33). Recent research also shows it to to exist in lncRNA, microRNA, and non-coding RNA (32, 34, 35), considered a widespread RNA modification.

In RNA molecules, methylation levels are regulated by a series of enzymes reversibly and dynamically, which can be identified as “Writer”, “Eraser”, and “Reader” and all specifically interact with the m6A methylation site as follow.

The writer of m6A can catalyze mRNA methylation

METTL3 is a high molecular weight subcomplex whose component is still not fully understood, and METTL14 is its homologues (21, 36). WTAP is the regulatory subunit of methyltransferase by which METTL3 and METTL14 anchor to mRNA to methylate subsequent target adenosine residues. WTAP recruits METT3 and METT14, enabling the METTL3- METT14 complex to perform m6A methyltransferase activity, affecting m6A methylation, and thus RNA shearing (37). Junho Choe’s team found that METTL3-elF3h interacts with each other to mediate mRNA cycling and translation through the association between the elF3h subunit at the mRNA 5‘end and METTL3 binding to the specific site near the translation termination codon. METTL3-elF3h mediates mRNA cyclization. Thus, efficient translation of target mRNA was promoted (38).

The eraser of m6A can remove m6A from RNA

FTO was the first eraser to be identified, in 2011 (21). Since its discovery, much research on its regulation in enormous physiological and pathological processes has been carried out. FTO in humans is an approximate 400 kb gene, containing 8 introns and 9 exons, located on 16q12.2 (39). FTO can remove the m6A methylation from multiple mRNAs through an α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG) and Fe (II)-dependent manner (40). Its modification process is claimed in detail in previous research. In brief, initially, FTO oxidizes m6A methylation to the intermediate N6-hydroxymethyl adenosine (hm6A). In the second step, FTO oxidizes metastable hm6A in the same way as m6A, forming further oxidized production N6 -formyladenosine (f6A) (41). As a result, hm6A and f6a spontaneously break down to adenine and the m6A methylation in RNA is removed (41, 42).

ALKBH5 is another eraser identified later which demethylates the RNA efficiently (43). Research has shown its regulator function in many regulator pathways by mRNA methylation. However, the underlying mechanism remains mysterious.

The reader of m6A can capture mRNA methylation

YTH domain is a module recognizing the methylation of m6A dependently, consisting of YTHDC1, YTHDC2, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 (25). The stability of m6A methylation modified mRNA is regulated by YTHDF2 in the way of recognizing m6A methylation and reducing the stability of the target transcript. In addition, another m6A reading protein, YTHDF1, was found to interact with the translation machinery of the related genes and promote protein synthesis. The m6A mRNA modification enforces rapid response of gene expression and controlled protein production, improved translation efficiency through YTHDF1-mediated translation, and controls target transcripts’ lifetime through YTHDF2-mediated degradation (29).

RNA m6A methylation regulates the lipid metabolism

Lipid, which mainly consists of triglycerides, cholesterol, phospholipids, and glycolipid, is involved in body energy metabolism and is the component of the cell membrane. It is also the precursor of various molecules that play important biological roles. Thus, lipid metabolism, such as digestion, absorption, synthesis, and decomposition is essential for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis (44, 45).

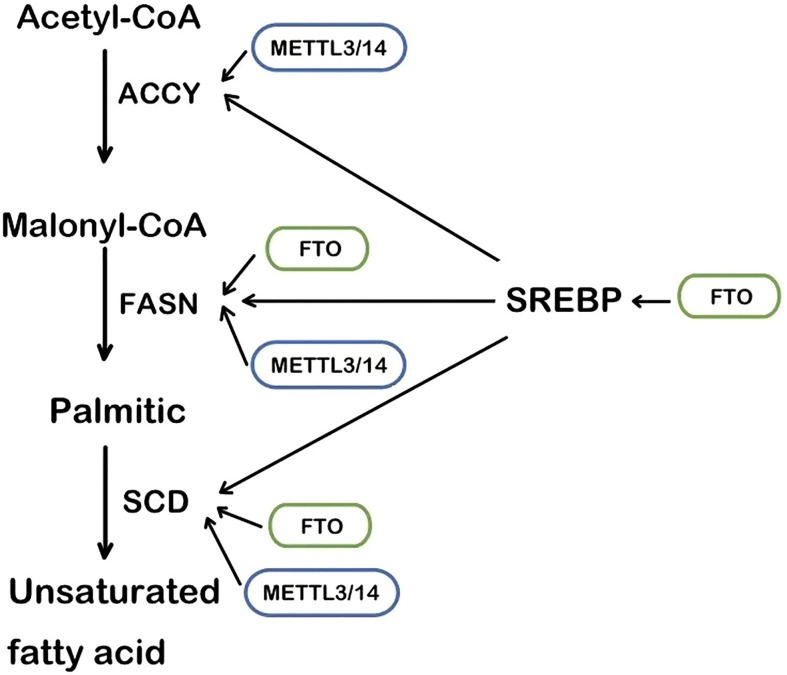

The RNA m6A methylase METTL3 and METTL4 are also involved in the regulation of lipid accumulation in cells. METTL3-mediated m6A methylation makes the metabolism-related gene’s mRNA more unstable, leading to metabolic disorders and lipid accumulation in the liver (46). Likewise, in cardiac cells, METTL3 deficiency decreases the RNA m6A methylation and the triglyceride deposition (47). Fatty acid synthase (FASN), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCY), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) are the regulator targets, as recently reported ( Figure 1 ). Mechanistically, METTL3/METTL14 complex induces the increase of mRNA to accelerate the production of lipid (48, 49). Consistently, METTL3 and the recognizing and binding protein YTHDF2 increase the m6A methylation level of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorα(PPARα) and its expression, impacting the downstream lipid accumulation (50). Inflammation is also involved in the lipid accumulation procedure. METTL3 deficiency induces a lower level of m6A methylation of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and therefore the transcripts are entrapped in the nucleus, leading to the downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB) to be suppressed. In consequence, inflammation and the absorption of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) are reduced (51).

Figure 1.

The main steps of lipogenesis and the regulation of FTO and METTL3/14. SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein; FASN, fatty acid synthase; ACCY, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase.

Once introduced in 1974 (52), RNA m6A methylation modification was found to affect diverse physiological and pathological progressions in cardiomyocytes (53), hepatocyte (54), axoneuron (11), and so on. Its regulation function in the lipid metabolism is revealed over decades. In general, its regulation function depends on the enhancement or reduction of the m6A level and recognition of the m6A site by various regulatory enzymes. But its interaction with genes related to lipid synthesis and decomposition is complicated and remains to be elucidated by research.

The first identified RNA m6A demethylase, FTO, is strongly connected with lipid accumulation in multiple cells and tissues. In the obesity group, high FTO level is positively correlated with Body Mass Index (BMI) and body fat (55, 56). In vitro, it promotes intracellular lipid accumulation by RNA demethylation while FTO knockdown did not (57, 58).

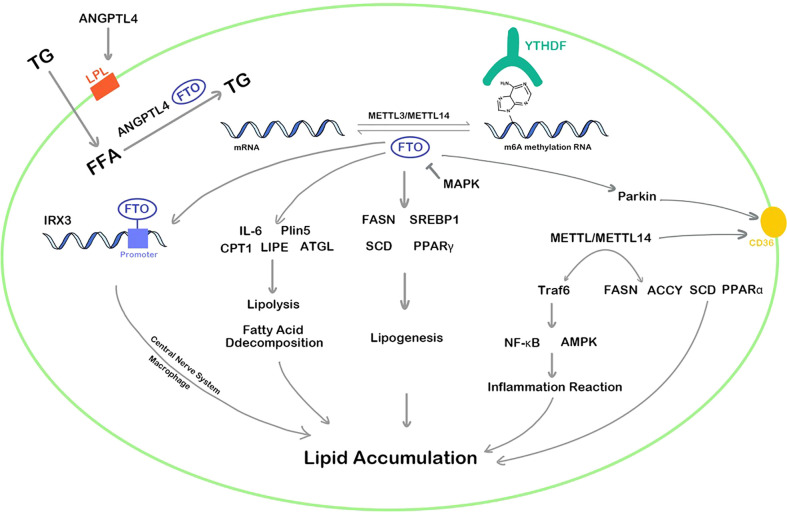

As an enzyme that demethylates m6A (59), FTO regulates m6A methylation levels of multiple RNA in lipid anabolism and catabolism. The process of lipid synthesis can be improved by FTO-mediated RNA demethylation. In the 3’UTR region of multiple lipogenic genes’ mRNA such as SCD, PPARγ, and sterol regulatory element-bindin protein-1 (SREBP1), which are all involved in the triacylglycerol and Cholesterol Synthesis. ( Figure 1 ) FTO decreases their level of m6A methylation to improve the stability of mRNA (60, 61). In the hepatocyte, the m6A methylation level in FASN mRNA is enhanced and lipogenesis is inhibited by the FTO knockdown and YTHDF2 recognition (62). Angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4) is also the key target of triglycerides synthesis and hydrolysis intracellularly and extracellularly. It inhibits lipoprotein lipase(LPL), leading to inhibiting extracellular lipolysis (63). FTO decreases the level of the translation of ANGPTL4, hence hydrolysis of extracellular triglycerides is promoted. The fatty acid is transported into adipocytes, inducing lipid accumulation (39, 63). Conversely, ANGPTL4 promotes intracellular lipolysis (64). Evidence has shown knockout of FTO affects intracellular ANGPTL4 level and intracellular lipolysis (65). The different results may account for the different mRNA sites where the m6A methylation is located. It is an interesting issue to explore.

Nevertheless, the role played by FTO in lipolysis remains disputed. FTO decreases the expression of interleukin 6 (IL-6) mRNA in adipose tissues (66) and consequently inhibits the lipolysis genes (67). In addition, FTO reduces lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation by reducing the adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), hormone-sensitive lipase (LIPE), and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) mRNA expression (68).

Interestingly, another FTO regulator pathway revealed that the promotion of FTO downregulated the obesity-related gene iroquois homeobox protein 3 (IRX3) level in the hypothalamus and macrophage. So, lipolysis was inhibited through affecting whole body modulated energy expenditure and metabolic inflammation (69, 70). However, it should be noted that the interaction of FTO and IRX3 is not the traditional m6A methylation modification, but the noncoding regions of FTO serve as a long-range regulatory element to influence the expression of IRX3 (71).

Furthermore, FTO-mediated RNA m6A methylation shows a close correlation with cellular triglyceride (TG) uptaking that is regulated by adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (72, 73). AMPK suppresses the expression of FTO to upregulate the m6A level of Parkin2 mRNA and promote its decay. Then CD36 was translocated to the membrane and LCFA uptaking of cells is increased (74, 75).

In summary, both FTO and METTL3 play vital regulatory roles in lipid metabolism and can promote the accumulation of lipids in various cells, affecting the decomposition and synthesis of lipids. The regulation pathways of FTO and METTL3/METTL14 are complex and diverse, which can methylate or demethylate the RNA m6A of targets in multiple pathways such as inflammation, energy homeostasis, nerve-related lipid regulation, lipid metabolism balance, resulting in corresponding high or low gene expression ( Figure 2 ). In addition, YTHDF protein plays an epigenetic role in recognizing m6A methylation sites of RNA and regulates the translation. Although the area of RNA m6A methylation is a popular spot in recent years, a convincing and authoritative theory is urgently needed. The function of RNA m6A methylation in many genes remains controversial and the deeply regulation process requires further investigation.

Figure 2.

RNA m6A regulators influence lipid cellar accumulation in various ways. TG, triglyceride; ANGPTL4, angiopoietin-like protein 4; IRX3, iroquois homeobox protein 3; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; FFA, free fatty acid; IL-6, interleukin 6; Plin5, perilipin5; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1; LIPE, hormone-sensitive lipase; ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; FASN, fatty acid synthase; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; SREBP1, sterol regulatory element-bindin protein-1; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase; Traf6, TNF receptor associated factor 6; ACCY, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; NF-κb, nuclear factor kappa-B; AMPK, adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase.

m6A methylation and lipid-related metabolic diseases

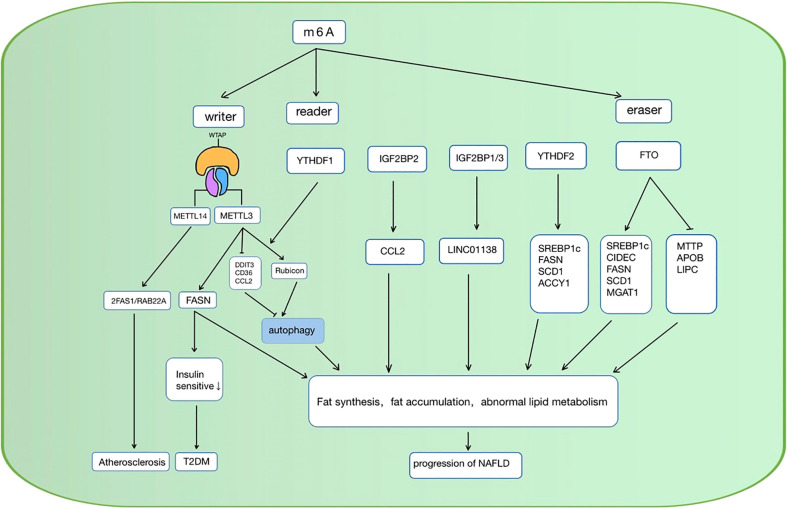

When the cellular lipid metabolism is disordered, excessive lipid accumulation or lipid accumulation in ectopic tissues due to the imbalance of lipid uptake, decomposition, and synthesis in the cell, can result in a series of intracellular pathophysiological reactions. Inflammation (76), oxidative stress (77), chromatin histone modification (78), etc. caused by lipid accumulation can lead to cellular dysfunction, apoptosis, and even death. As mentioned above, RNA m6A methylation is involved in multiple pathways in lipid metabolism, and it also shows a vital function in the occurrence and development of lipid metabolic diseases ( Table 1 ). Over the past decades, studies have investigated some possible targets for the diagnosis, physiopathology process, and therapy of metabolic diseases such as NAFLD, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis ( Figure 3 ).

Table 1.

Multiple functions of RNA m6A methylation regulator in lipid metabolic disease.

| Regulator | Disease | Influence towards disease | Target | Function | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METTL3 | NAFLD | NEGATIVE | DDIT3 | Loss of METTL3 results in increasing in DDIT | 2021 | (79) |

| METTL3 | NAFLD | NEGATIVE | Rubicon axis | METTL3 and its partner YTHDF1 promote the stability of Rubicon mRNA | 2021 | (80) |

| METTL3 | NAFLD/NASH | POSITIVE | CD36,CCL2 | METTL3 inhibits the expression of CD36 and CCL2 | 2015 | (81) |

| FTO | NAFLD | NEGATIVE | SREBP1c, CIDEC | Knockdown of FTO down-regulates the expression of SREBP1c and CIDEC | 2018 | (82) |

| FTO | NAFLD | NEGATIVE | FASN, SCD, MGAT1, MTTP, APOB, LIPC | FTO overexpression in HepG2 cells positively regulate FASN, SCD1, MAGT1 while negatively regulate MTTP, APOB, LIPC | 2018 | (57) |

| IGF2BP2 | NAFLD | NEGATIVE | CCL2 | Overexpression of p62/IMP2-2/IGF2BP2-2 elevated CCL2 expression levels | 2014 | (83) |

| IGF2BP1/IGF2BP3 | NAFLD/HCC | NEGATIVE | LINC01138 | IGF2BP1/IGF2BP3 stabilized LINC01138 transcript | 2018 | (84) |

| METTL3 | T2DM | NEGATIVE | FASN | METTL3 silencing could decrease the m6A mRNA levels of FASN | 2019 | (48) |

| METTL3 | HCC | NEGATIVE | SOCS | YTHDF2 cooperates with METTL3 depressing the level of SOCS | 2018 | (85) |

| YTHDC2 | NAFLD | CRITICAL | SREBP1c, FASN, SCD1, and ACCY1 | YTHDC2 decreases the stability of mRNA of SREBP1c, FASN, SCD1, and ACCY1 and inhibit gene expression | 2020 | (86) |

| FTO | HYPERLIPIDAEMIA | NEGATIVE | – | the secretion of inflammatory factors IL-1βand the expression of FTO was high in dyslipidemia induced by LPS |

2016 | (87) |

| METTL14 | ATHEROSCLEROSIS | NEGATIVE | ZFAS1/RAB22a | METTL14 mediated m6A modification to LncRNA ZFAS1/RAB22a | 2020 | (88) |

Figure 3.

RNA m6A regulators are involved in the regulation of lipid metabolic diseases in various ways. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; SREBP1c, sterol regulatory element-bindin protein-1; FASN, Fatty acid synthase; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACCY1, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, CIDEC, cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector C; MAGAT, monoacylglycerol acyltransferases; LIPC, hepatic lipase; APOB, apolipoprotein; ZFAS1/RAB22a, zinc finger antisense 1/ras-related protein rab-22a; DDIT3, DNA damage-inducible transcript 4; T2DM, diabetes mellitus type 2; METTL, methyltransferase-like 3; YTHFD, YT521-B homology domain family; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; IGFBP, Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins; MTTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein.

m6A methylation and the lipid metabolism in NAFLD

The liver is one of the most significant organs in fatty acid synthesis and decomposition. Recent studies have revealed that RNA m6A methylation happened in hepatocyte matters in lipid metabolism disorder. Patients who suffered from NAFLD were detected to have a higher level of FTO mRNA in the liver (46). Similar results were observed in several studies (89–91), which have been widely acknowledged by researchers.

Thus, exploring the further mechanism is imperative. The “writer” METTL3 is also considered to be related to liver lipid accumulation (50, 92). Forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), Enoyl-CoA Hydratase And 3-Hydroxyacyl CoA Dehydrogenase (EHHADH), PPARα, FASN, and Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) were the regulator targets that had been reported (93). Furthermore, in the recent 2 years of research, some other regulation targets have been put forward. METTL3, as the m6A writer, improves DNA damage-inducible transcript 4 (DDIT4) mRNA the methylation level, as a result, affects its stability. When METTL3 is knocked down, DDIT4 reduces the level of lipid accumulation and the activity of inflammation in hepatocytes of the NAFLD patients by the signaling pathway of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and NF-κB (79). Autophagy also plays a role in RNA m6A methylation of the NAFLD progression. METTL3 and its partner YTHDF1 inhibit the autophagic flux in hepatocytes and block the clearance of lipid droplets by the means of promoting the stability of Rubicon mRNA, which inhibited the autophagy process of autophagosome-lysosome fusion (80).

Conversely, METTL3 knockdown increased the free fatty acid uptake mediated by CD36, and the inflammation reaction induced by C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), as the result, lead to the progression from NAFLD to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (81). The regulation of METTL3 on NAFLD may be diverse.

FTO can affect the expression of FASN, SCD, Monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MAGAT), SREBP1c, and cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector C (CIDEC) (82) to regulate the lipogenesis in hepatocytes. Meanwhile, FTO up/down-regulates the lipid transport protein of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP), hepatic lipase (LIPC), apolipoprotein B (APOB) (57), inducing the process of lipid transport (93). As a result, excessive lipid deposition in hepatocytes results in hepatocyte steatosis.

Furthermore, the “reader” YTHDF2 is also involved in the regulation of TG homeostasis and lipogenesis in NAFLD, and SREBP1c, FASN, and SCD1, and ACCY1 is the gene related to the process (86). In the next section, IGF2BP2, a recently identified m6A reader, was also reported to be a promoter of NAFLD (83), which can promote the stability of mRNA (28), and IGF2BP1/IGF2BP3 was also reported to be associated with poor outcomes of liver cancer (84).

NAFLD is a complex metabolic disease and many pathological changes happened in liver tissue (94).The RNA m6A methylation regulator FTO, METTL3, and the recognition protein family YTHDF affect the progression of NAFLD to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by the means of disorder lipid metabolism, oxidative stress (87), and autophagy (80), making it an important potential treatment target. Altering the RNA m6A methylation level of various proteins reduces the hepatic abnormal lipid accumulation, thereby further relieving the abnormal state of cells. This epigenetic regulation may significantly improve the development of NAFLD and even reverse hepatocyte degeneration.

m6A methylation and lipid metabolism in diabetes

Diabetes is one of the highest prevalence diseases and over 400 million patients live with this disease worldwide. Its complication causes severe disease burden (95, 96). It has been revealed that multiple m6A methylations target pathways like Insulin-like growth factor 1-protein kinase B-pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1(IGF1-AKT-PDX1) and genes like diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), glucose-6-phsophatase catalytic subunit (G6PC), and FOXO1, are involved in the glucose and insulin secretion regulation of pancreatic islet B cell (97, 98). Besides, lipid metabolism disorder related to m6A methylation also plays an important part in insulin resistance.

FASN, the key protein in lipid metabolism, has proved to be closely connected to insulin resistance by research that in adipose tissue, FASN expression was increased and insulin sensitivity was impaired (99). METTL3 also inhibits insulin sensitivity via the modification of FASN mRNA. Along with the overexpression or the METTL3 deficiency in high-fat diet (HFD) rats, the level of FASN mRNA and lipid content in the liver is higher or lower accordingly, and the insulin sensitivity is improved (46, 48). However, further studies are still needed to claim how exactly m6A interacts with insulin sensitivity.

RNA m6A methylation and lipid metabolism in cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, while hyperlipidemia is responsible for about one-third of all cardiovascular diseases (100, 101). The RNA m6A methylation involved lipid metabolism disorder and chronic inflammation reaction has been reported as a possible mechanism in the past few years. Research has revealed that hyperlipidemia level is highly connected with m6A-SNPs (102) and FTO-associated inflammatory factor IL-1β, IL-6, and LPS which induce hyperlipidemia may be the factors in the development of chronic heart disease (38, 87). Additionally, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD) is also considered a key point. YTHDF2 binds to 6PGD mRNA and promotes its translation, while 6PGD deficiency can lead to lower blood cholesterol making YTHDF2 a possible target for lowering blood cholesterol (103–105). Moreover, very recent research mentioned that the METTL14 mediating lncRNA zinc finger antisense 1/ras-related protein rab-22a (ZFAS1/RAB22a) m6A methylation modification is also a possible pathway to atherosclerosis (88).

Conclusion and discussion

After decades of research, RNA m6A methylation remains a broad research space that structures functions and regulation mechanisms of many regulators remain critical and unknown (106). RNA m6A methylation is an important and novel regulatory manner in epigenetics. It has a regulatory role in adipogenicity differentiation and adipogenesis in adipose tissue (107, 108). In addition, it also exerts vital functions in lipid metabolism, which is interwoven with human health. A greater understanding of the regulatory mechanism of lipid metabolism also leads to advances in life science research.

In the process of RNA m6A methylation regulating the lipid metabolism, the m6A “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers” can add, remove, or recognize the RNA m6A methylation sites in mRNA and affect its translation, decay, splicing, and export, leading to thousands of biological processes (109). Inflammation is one of the parts, and it has proved closely connected with obesity and fatty acid absorption (110, 111). In the process of RNA m6A methylation regulating lipid metabolism, IL-6, CCL2, IRX3, TRAF6, and many inflammation factors-related proteins become the central regulatory targets. The lipid synthesis and decomposition genes such as FASN, SREBP, and CES2 (112) are also affected by mRNA m6A methylation and demethylation. Lipogenesis and lipolysis are directly regulated. In addition, some other cell signaling pathways are also involved. The regulation of RNA m6A methylation is a complex process that involves a variety of mechanisms in multiple cells. Research in this area still has much to be done.

Disorder of the global or partial lipid metabolism causes intractable chronic diseases. In the occurrence and development of NAFLD, abnormal lipid accumulation in hepatocytes is one of the major pathological changes, and METTL3, METTL14, FTO, and YTHDF mediated key gene mRNA m6A methylation are all related to it. Furthermore, lipid metabolism disorder is responsible for insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis (113), in which RNA m6A methylation all plays a critical part, making it a great potential therapeutic target.

At the present stage, further research on m6A mRNA methylation in its effective metabolism is needed. Many studies remain controversial, and m6A mRNA methylation may affect the expression of mRNA or protein levels of different key positive or negative regulatory factors in different pathophysiological processes, so, likely, the “Writer”, “Eraser”, and “Reader” of the same RNA m6A methylation regulators may coregulate two pathophysiological processes with opposite effects. Moreover, future studies on the regulatory mechanism of m6A mRNA methylation on adipose metabolism should not be limited to METTL3, FTO, and YTHDF2, and other “Writer”, “Eraser”, and “Reader” of m6A mRNA methylation may also participate in the occurrence of lipid metabolism through different pathways while researches remain limited. In summary, RNA m6A methylation regulates many targets, including lipid synthesis, breakdown, as well as accumulation. Moreover, RNA m6A methylation has the therapeutic potential to be a target for metabolic diseases like obesity, NAFLD, and diabetes which will foster the treatment of them and related diseases better in humans in the future.

Author contributions

YF conceived the study and designed the study protocol. YTW and YJW conducted the literature review and drafted the manuscript. TS and JG reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, and XG made revisions as needed. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 82070838 to FY, 82170831 to GX), National Tutorial System Training Project for Youth Key Talents in the Suzhou Health system(Grant numbers Qngg2021007 to FY), Project of medical application of nuclear technology in discipline construction(Grant numbers XKTJ-HRC2021007 to GX).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Gohlke S, Zagoriy V, Cuadros Inostroza A, Méret M, Mancini C, Japtok L, et al. Identification of functional lipid metabolism biomarkers of brown adipose tissue aging. Mol Metab (2019) 24:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng L, Zhang S, Shang F, Ning Y, Huang Z, He R, et al. Emodin improves glucose and lipid metabolism disorders in obese mice via activating brown adipose tissue and inducing browning of white adipose tissue. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2021) 12:618037. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.618037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, Scherer PE. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med (2013) 19:1338–44. doi: 10.1038/nm.3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tóth BB, Arianti R, Shaw A, Vámos A, Veréb Z, Póliska S, et al. FTO intronic SNP strongly influences human neck adipocyte browning determined by tissue and PPARγ specific regulation: A transcriptome analysis. Cells (2020) 9:987. doi: 10.3390/cells9040987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Y, Ma KL, Ruan XZ, Liu BC. Dysregulation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor pathway is involved in lipid disorder-mediated organ injury. Int J Biol Sci (2016) 12:569–79. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watt MJ, Miotto PM, De Nardo W, Montgomery MK. The liver as an endocrine organ-linking NAFLD and insulin resistance. Endocr Rev (2019) 40:1367–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2019-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xenoulis PG, Steiner JM. Lipid metabolism and hyperlipidemia in dogs. Vet J (2010) 183:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deprince A, Haas JT, Staels B. Dysregulated lipid metabolism links NAFLD to cardiovascular disease. Mol Metab (2020) 42:101092. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aryal B, Price NL, Suarez Y, Fernández-Hernando C. ANGPTL4 in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med (2019) 25:723–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zakaria Z, Othman ZA, Nna VU, Mohamed M. The promising roles of medicinal plants and bioactive compounds on hepatic lipid metabolism in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in animal models: molecular targets. Arch Physiol Biochem (2021) 21, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2021.1939387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Geng X, Li Q, Xu J, Tan Y, Xiao M, et al. m6A modification in RNA: biogenesis, functions and roles in gliomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2020) 39:192. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01706-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen M, Nie ZY, Wen XH, Gao YH, Cao H, Zhang SF, et al. m6A RNA methylation regulators can contribute to malignant progression and impact the prognosis of bladder cancer. Biosci Rep (2019) 39:BSR20192892. doi: 10.1042/BSR20192892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li J, Pei Y, Zhou R, Tang Z, Yang Y. Regulation of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification and its emerging roles in skeletal muscle development. Int J Biol Sci (2021) 17:1682–92. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.56251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Du Y, Ma Y, Zhu Q, Liu T, Jiao Y, Yuan P, et al. An m6A-related prognostic biomarker associated with the hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment. Front Pharmacol (2021) 12:707930. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.707930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y, Zheng Y, Guo D, Zhang X, Guo S, Hui T, et al. m6A methylation analysis of differentially expressed genes in skin tissues of coarse and fine type liaoning cashmere goats. Front Genet (2019) 10:1318. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang J, Chen J, Fei X, Wang X, Wang K. N6-methyladenine RNA modification and cancer. Oncol Lett (2020) 20:1504–12. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feng ZY, Gao HY, Feng TD. Immune infiltrates of m(6)A RNA methylation-related lncRNAs and identification of PD-L1 in patients with primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol (2021) 9:672248. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.672248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang L, Chen S, Ma J, Liu Z, Liu H. REW-ISA V2: A biclustering method fusing homologous information for analyzing and mining epi-transcriptome data. Front Genet (2021) 12:654820. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.654820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bai Y, Yang C, Wu R, Huang L, Song S, Li W, et al. YTHDF1 regulates tumorigenicity and cancer stem cell-like activity in human colorectal carcinoma. Front Oncol (2019) 9:332. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5' terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell (1975) 4:379–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet (2014) 15:293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature (2012) 485:201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell (2012) 149:1635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sommer S, Lavi U, Darnell JE, Jr. The absolute frequency of labeled n-6-methyladenosine in HeLa cell messenger RNA decreases with label time. J Mol Biol (1978) 124:487–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90183-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature (2014) 505:117–20. doi: 10.1038/nature12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2019) 20:608–24. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0168-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feng M, et al. YBX1 is required for maintaining myeloid leukemia cell survival by regulating BCL2 stability in an m6A-dependent manner. Blood (2021) 138:71–85. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20:285–95. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell (2015) 161:1388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu T, Wei Q, Jin J, Luo Q, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. The m6A reader YTHDF1 promotes ovarian cancer progression via augmenting EIF3C translation. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48:3816–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res (2017) 27:315–28. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roundtree IA, Luo GZ, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou T, Cui Y, et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife (2017) 6:BSR20192892. doi: 10.7554/eLife.31311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun T, Wu R, Ming L. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer. BioMed Pharmacother (2019) 112:108613. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu N, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine–encoded epitranscriptomics. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2016) 23:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T, et al. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45:6051–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. Rna (1997) 3:1233–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res (2014) 24:177–89. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhong H, Tang HF, Kai Y. N6-methyladenine RNA modification (m(6)A): An emerging regulator of metabolic diseases. Curr Drug Targets (2020) 21:1056–67. doi: 10.2174/1389450121666200210125247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang Z, Yu GL, Zhu X, Peng TH, Lv YC. Critical roles of FTO-mediated mRNA m6A demethylation in regulating adipogenesis and lipid metabolism: Implications in lipid metabolic disorders. Genes Dis (2022) 9:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2021.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Su R, Dong L, Li Y, Gao M, Han L, Wunderlich M, et al. Targeting FTO suppresses cancer stem cell maintenance and immune evasion. Cancer Cell (2020) 38:79–96.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, Zhao YL, Yang YG. FTO and obesity: mechanisms of association. Curr Diabetes Rep (2014) 14:486. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0486-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol (2011) 7:885–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fu Y, Klungland A, Yang YG, et al. Sprouts of RNA epigenetics: The discovery of mammalian RNA demethylases. RNA Biol (2013) 10:915–8. doi: 10.4161/rna.24711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bian X, Liu R, Meng Y, Xing D, Xu D, Lu Z, et al. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J Exp Med (2021) 218:e20201606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Röhrig F, Schulze A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2016) 16:732–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li Y, Zhang Q, Cui G, Zhao F, Tian X, Sun BF, et al. m(6)A regulates liver metabolic disorders and hepatogenous diabetes. Genomics Proteomics Bioinf (2020) 18:371–83. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu Z, Qin Y, Lv B, Tian Z, Zhang B. Intermittent fasting improves high-fat diet-induced obesity cardiomyopathy via alleviating lipid deposition and apoptosis and decreasing m6A methylation in the heart. Nutrients (2022) 14:251. doi: 10.3390/nu14020251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xie W, Ma LL, Xu YQ, Wang BH, Li SM. METTL3 inhibits hepatic insulin sensitivity via N6-methyladenosine modification of fasn mRNA and promoting fatty acid metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2019) 518:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang Y, Cai J, Yang X, Wang K, Sun K, Yang Z, et al. Dysregulated m6A modification promotes lipogenesis and development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Ther (2022) 30:2342–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhong X, Yu J, Frazier K, Weng X, Li Y, Cham CM, et al. Circadian clock regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism by modulation of m(6)A mRNA methylation. Cell Rep (2018) 25:1816–1828.e1814. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zong X, Zhao J, Wang H, Lu Z, Wang F, Du H, et al. Mettl3 deficiency sustains long-chain fatty acid absorption through suppressing Traf6-dependent inflammation response. J Immunol (2019) 202:567–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1974) 71:3971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Qin Y, Li L, Luo E, Hou J, Yan G, Wang D, et al. Role of m6A RNA methylation in cardiovascular disease (Review). Int J Mol Med (2020) 46:1958–72. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen M, Wong CM. The emerging roles of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) deregulation in liver carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer (2020) 19:44. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01172-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tews D, Fischer-Posovszky P, Wabitsch M. Regulation of FTO and FTM expression during human preadipocyte differentiation. Horm Metab Res (2011) 43:17–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Czogała W, Czogała M, Strojny W, Wątor G, Wołkow P, Wójcik M, et al. Methylation and expression of FTO and PLAG1 genes in childhood obesity: Insight into anthropometric parameters and glucose-lipid metabolism. Nutrients (2021) 13:1683. doi: 10.3390/nu13051683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kang H, Zhang Z, Yu L, Li Y, Liang M, Zhou L, et al. FTO reduces mitochondria and promotes hepatic fat accumulation through RNA demethylation. J Cell Biochem (2018) 119:5676–85. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu R, Liu Y, Yao Y, Zhao Y, Bi Z, Jiang Q, et al. FTO regulates adipogenesis by controlling cell cycle progression via m(6)A-YTHDF2 dependent mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2018) 1863:1323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Huang Y, Su R, Sheng Y, Dong L, Dong Z, Xu H, et al. Small-molecule targeting of oncogenic FTO demethylase in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell (2019) 35:677–691.e610. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hu Y, Feng Y, Zhang L, Jia Y, Cai D, Qian SB, et al. GR-mediated FTO transactivation induces lipid accumulation in hepatocytes via demethylation of m(6)A on lipogenic mRNAs. RNA Biol (2020) 17:930–42. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1736868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sun L, Gao M, Qian Q, Guo Z, Zhu P, Wang X, et al. Triclosan-induced abnormal expression of miR-30b regulates fto-mediated m(6)A methylation level to cause lipid metabolism disorder in zebrafish. Sci Total Environ (2021) 770:145285. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sun D, Zhao T, Zhang Q, Wu M, Zhang Z. Fat mass and obesity-associated protein regulates lipogenesis via m(6) a modification in fatty acid synthase mRNA. Cell Biol Int (2021) 45:334–44. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yoshida K, Shimizugawa T, Ono M, Furukawa H. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 is a potent hyperlipidemia-inducing factor in mice and inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase. J Lipid Res (2002) 43:1770–2. doi: 10.1194/jlr.C200010-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dijk W, Kersten S. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase by Angptl4. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2014) 25:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang CY, Shie SS, Wen MS, Hung KC, Hsieh IC, Yeh TS, et al. Loss of FTO in adipose tissue decreases Angptl4 translation and alters triglyceride metabolism. Sci Signal (2015) 8:ra127. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Terra X, Auguet T, Porras JA, Quintero Y, Aguilar C, Luna AM, et al. Anti-inflammatory profile of FTO gene expression in adipose tissues from morbidly obese women. Cell Physiol Biochem (2010) 26:1041–50. doi: 10.1159/000323979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zeng B, Wu R, Chen Y, Chen W, Liu Y, Liao X, et al. FTO knockout in adipose tissue effectively alleviates hepatic steatosis partially via increasing the secretion of adipocyte-derived IL-6. Gene (2022) 818:146224. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mizuno TM. Fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene and hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. Nutrients (2018) 10:1600. doi: 10.3390/nu10111600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. de Araújo TM, Velloso LA. Hypothalamic IRX3: A new player in the development of obesity. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2020) 31:368–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yao J, Wu D, Zhang C, Yan T, Zhao Y, Shen H., et al. Macrophage IRX3 promotes diet-induced obesity and metabolic inflammation. Nat Immunol (2021) 22:1268–79. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01023-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Smemo S, Tena JJ, Kim KH, Gamazon ER, Sakabe NJ, Gómez-Marín C, et al. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature (2014) 507:371–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhao L, Zhang C, Luo X, Wang P, Zhou W, Zhong S, et al. CD36 palmitoylation disrupts free fatty acid metabolism and promotes tissue inflammation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol (2018) 69:705–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jeppesen J, Albers PH, Rose AJ, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Dzamko N, et al. Contraction-induced skeletal muscle FAT/CD36 trafficking and FA uptake is AMPK independent. J Lipid Res (2011) 52:699–711. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wu W, Wang S, Liu Q, Shan T, Wang X, Feng J, et al. AMPK facilitates intestinal long-chain fatty acid uptake by manipulating CD36 expression and translocation. FASEB J (2020) 34:4852–69. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901994R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhou X, Chen J, Chen J, Wu W, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. The beneficial effects of betaine on dysfunctional adipose tissue and N6-methyladenosine mRNA methylation requires the AMP-activated protein kinase α1 subunit. J Nutr Biochem (2015) 26:1678–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med (2016) 8:42. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0303-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McGarry JD, Mannaerts GP, Foster DW. A possible role for malonyl-CoA in the regulation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis. J Clin Invest (1977) 60:265–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI108764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McDonnell E, Crown SB, Fox DB, Kitir B, Ilkayeva OR, Olsen CA, et al. Lipids reprogram metabolism to become a major carbon source for histone acetylation. Cell Rep (2016) 17:1463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Qin Y, Li B, Arumugam S, Lu Q, Mankash SM, Li J, et al. m(6)A mRNA methylation-directed myeloid cell activation controls progression of NAFLD and obesity. Cell Rep (2021) 37:109968. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Peng Z, Gong Y, Wang X, He W, Wu L, Zhang L, et al. METTL3-m(6)A-Rubicon axis inhibits autophagy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol Ther (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Li X, Yuan B, Lu M, Wang Y, Ding N, Liu C, et al. The methyltransferase METTL3 negatively regulates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) progression. Nat Commun (2021) 12:7213. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27539-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen A, Chen X, Cheng S, Shu L, Yan M, Yao L, et al. FTO promotes SREBP1c maturation and enhances CIDEC transcription during lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2018) 1863:538–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Simon Y, Kessler SM, Bohle RM, Haybaeck J, Kiemer AK. The insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) mRNA-binding protein p62/IGF2BP2-2 as a promoter of NAFLD and HCC? Gut (2014) 63:861–3. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Li Z, Liu X, Li S, Wang Q, Di Chen. The LINC01138 drives malignancies via activating arginine methyltransferase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun (2018) 9:1572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04006-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chen M, Wei L, Law CT, Tsang FH, Shen J, Cheng CL, et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase-like 3 promotes liver cancer progression through YTHDF2-dependent posttranscriptional silencing of SOCS2. Hepatology (2018) 67:2254–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.29683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zhou B, et al. N(6) -methyladenosine reader protein YT521-b homology domain-containing 2 suppresses liver steatosis by regulation of mRNA stability of lipogenic genes. Hepatology (2021) 73:91–103. doi: 10.1002/hep.31220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhang Y, Guo F, Zhao R. Hepatic expression of FTO and fatty acid metabolic genes changes in response to lipopolysaccharide with alterations in m(6)A modification of relevant mRNAs in the chicken. Br Poult Sci (2016) 57:628–35. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1201199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gong C, Fan Y, Liu J. METTL14 mediated m6A modification to LncRNA ZFAS1/ RAB22A: A novel therapeutic target for atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol (2021) 328:177. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Guo J, Ren W, Li A, Ding Y, Guo W, Su D, et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated gene enhances oxidative stress and lipogenesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci (2013) 58:1004–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2516-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chen J, Zhou X, Wu W, Wang X, Wang Y. FTO-dependent function of N6-methyladenosine is involved in the hepatoprotective effects of betaine on adolescent mice. J Physiol Biochem (2015) 71:405–13. doi: 10.1007/s13105-015-0420-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sun L, Ling Y, Jiang J, Wang D, Wang J, Li J, et al. Differential mechanisms regarding triclosan vs. bisphenol a and fluorene-9-bisphenol induced zebrafish lipid-metabolism disorders by RNA-seq. Chemosphere (2020) 251:126318. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Heng J, Wu Z, Tian M, Chen J, Song H, Chen F, et al. Excessive BCAA regulates fat metabolism partially through the modification of m(6)A RNA methylation in weanling piglets. Nutr Metab (Lond) (2020) 17:10. doi: 10.1186/s12986-019-0424-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhao Z, et al. Epitranscriptomics in liver disease: Basic concepts and therapeutic potential. J Hepatol (2020) 73:664–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Eslam M, Valenti L, Romeo S. Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: Clinical impact. J Hepatol (2018) 68:268–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet (2017) 389:2239–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Vijan S. In the clinic. type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med (2015) 162:Itc1–16. doi: 10.7326/AITC201503030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. De Jesus DF, Zhang Z, Kahraman S, Brown NK, Chen M, Hu J, et al. m(6)A mRNA methylation regulates human β-cell biology in physiological states and in type 2 diabetes. Nat Metab (2019) 1:765–74. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yang Y, Shen F, Huang W, Qin S, Huang JT, Sergi C, et al. Glucose is involved in the dynamic regulation of m6A in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2019) 104:665–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Menendez JA, Vazquez-Martin A, Ortega FJ, Fernandez-Real JM. Fatty acid synthase: association with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Clin Chem (2009) 55:425–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.115352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhao D, Liu J, Wang M, Zhang X, Zhou M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat Rev Cardiol (2019) 16:203–12. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gazzola K, Reeskamp L, van den Born BJ. Ethnicity, lipids and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol (2017) 28:225–30. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Mo X, Lei S, Zhang Y, Zhang H. Genome-wide enrichment of m(6)A-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the lipid loci. Pharmacogenomics J (2019) 19:347–57. doi: 10.1038/s41397-018-0055-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sheng H, Li Z, Su S, Sun W, Zhang X, Li L, et al. YTH domain family 2 promotes lung cancer cell growth by facilitating 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase mRNA translation. Carcinogenesis (2020) 41:541–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Batetta B, Bonatesta RR, Sanna F, Putzolu M, Mulas MF, Collu M, et al. Cell growth and cholesterol metabolism in human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient lymphomononuclear cells. Cell Prolif (2002) 35:143–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2002.00231.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zheng N. Research progress of N6-methyladenosine in the cardiovascular system. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2020) 26:. doi: 10.12659/MSM.921742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Jiang X, Liu B, Nie Z, Duan L, Xiong Q, Jin Z, et al. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther (2021) 6:74. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00450-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Song T, Yang Y, Wei H, Xie X, Lu J, Zeng Q, et al. Zfp217 mediates m6A mRNA methylation to orchestrate transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation to promote adipogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res (2019) 47:6130–44. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Song T, Yang Y, Jiang S, Peng J. Novel insights into adipogenesis from the perspective of transcriptional and RNA N6-Methyladenosine-Mediated post-transcriptional regulation. Adv Sci (Weinh) (2020) 7:2001563. doi: 10.1002/advs.202001563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wu S, Zhang S, Wu X, Zhou X. m(6)A RNA methylation in cardiovascular diseases. Mol Ther (2020) 28:2111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Vogel A, Brunner JS, Hajto A, Sharif O, Schabbauer G. Lipid scavenging macrophages and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids (2022) 1867:159066. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.159066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cox AJ, West NP, Cripps AW. Obesity, inflammation, and the gut microbiota. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2015) 3:207–15. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Takemoto S, Nakano M, Fukami T, Nakajima M. m(6)A modification impacts hepatic drug and lipid metabolism properties by regulating carboxylesterase 2. Biochem Pharmacol (2021) 193:114766. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Bäck M, Yurdagul A, Jr., Tabas I, Öörni K, Kovanen PT. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol (2019) 16:389–406. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0169-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]