Abstract

The rapid development of tissue engineering makes it an effective strategy for repairing cartilage defects. The significant advantages of injectable hydrogels for cartilage injury include the properties of natural extracellular matrix (ECM), good biocompatibility, and strong plasticity to adapt to irregular cartilage defect surfaces. These inherent properties make injectable hydrogels a promising tool for cartilage tissue engineering. This paper reviews the research progress on advanced injectable hydrogels. The cross-linking method and structure of injectable hydrogels are thoroughly discussed. Furthermore, polymers, cells, and stimulators commonly used in the preparation of injectable hydrogels are thoroughly reviewed. Finally, we summarize the research progress of the latest advanced hydrogels for cartilage repair and the future challenges for injectable hydrogels.

Keywords: injectable hydrogels, tissue engineering, cartilage defect, osteoarthritis, advanced

1 Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common chronic disease of joints, affecting approximately 90 million adults in the United States alone (approximately 37% of the adult population) and hundreds of millions worldwide (Krishnan and Grodzinsky, 2018; Luo et al., 2021). It is characterized by degeneration and defect of articular cartilage, which can cause joint pain, reduced mobility, and stiffness (Das and Farooqi, 2008). Unlike most other organizations, cartilage is a type of special connective tissue without blood vessels, nerves, and lymph nodes, characterized by immersing chondrocytes in ECM, which consists mainly of a matrix (polysaccharides), fibrous components (fibrin), and interstitial fluid (mainly water) (Armiento et al., 2019; Sirong et al., 2020). Therefore, cartilage cannot repair itself due to insufficient nutritional support and proper progenitor cell differentiation. When cartilage defects go untreated, joints inevitably deteriorate, leading to OA and disability (Simon and Jackson, 2006; Gao et al., 2014).

Non-surgical conservative treatment and drug (painkillers and NSAIDs) therapy can effectively relieve pain in the early stages of articular cartilage lesion but cannot reverse cartilage degeneration defect (Poddar and Widstrom, 2017). Transplantation (using allogeneic or autologous cells or tissues) and stimulation (stimulating self-repair of articular cartilage) are commonly used in the late treatment of OA (Tuan et al., 2013). The former includes allograft or autologous cartilage transplantation, perichondrium and periosteum transplantation, osteochondral transplantation, ACI, and other graft repair techniques. The latter include joint cleansing and debridement, cartilage grinding and shaping, microfractures, drilling, osteotomy, and joint traction (Fuggle et al., 2020). For patients with severe OA, severe invasive total joint replacement surgery is generally considered the last resort (Katz et al., 2021).

Hydrogels are widely used in tissue engineering and are advanced cross-linked 3D hydrophilic polymer network biomaterials because of their unique properties such as high-water content, biocompatibility, porosity and biodegradation, solid elastic properties, deformability, and softness (Yang et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021a). The hydrogel properties are similar to the characteristics of natural cartilage ECM and are easy to prepare. Hydrogel development is the most promising method for treating cartilage defects and cartilage regeneration (Wei et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022). Injectable hydrogels have attracted the attention of biomaterial scientists in cartilage tissue engineering (Schaeffer et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021a) (Figure 1). Because it can replace open implants with minimally invasive injections, it has the advantages of being less invasive, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and forming any desired shape in situ to match irregular defects (Liu et al., 2017a; Pascual-Garrido et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2021a). Injectable hydrogels provide hydration similar to the height of cartilage ECM. Biocompatibility and biodegradability of 3D structure and elastic properties can be controlled by improving cell metabolites and the supply of nutrients. The stimulus-response release mechanism can encapsulate cells and deliver efficient and effective bioactive molecules to the target of cartilage regeneration (Park et al., 2009; Pereira et al., 2009; Li et al., 2019). An ideal injectable hydrogel has several requirements, such as no toxic byproducts during in vivo gelation, appropriate solubility and gelation under physiological conditions, and a controlled gelation rate suitable for clinical practice (Jeznach et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of hydrogel injection in repairing cartilage defect. Adapted with permission of Wu et al. (2020).

This review aims to clarify the application of advanced injectable hydrogels in cartilage repair and regeneration. The progress and advantages of injectable hydrogels in cartilage repair and regeneration are reviewed, including the manufacturing technology (crosslinking method and structure) and suitable materials (polymers, cells and stimulators). Then, we summarize the research progress of the latest advanced injectable hydrogels in cartilage tissue engineering. Finally, the challenges in applying injectable hydrogels and their prospects in tissue engineering are also discussed.

1.1 Formation of injectable hydrogels

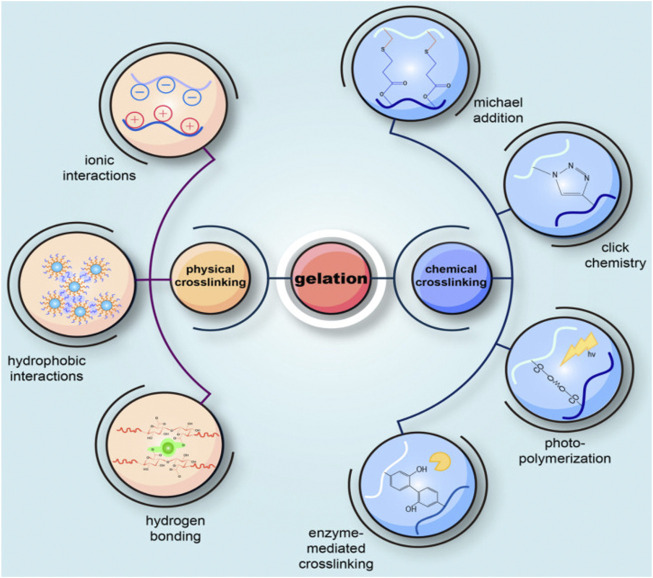

Gelation is a crucial step in the formation of an injectable hydrogel. According to the design structure and standard application, it is imperative to select the appropriate formation method to prepare injectable hydrogels (Li et al., 2012). There are several ways of preparing injectable hydrogels based on their reactivity or the connections they contain. The cross-linking mechanism of the hydrogel can be divided into chemical cross-linking and physical cross-linking (Liu et al., 2020) (Figure 2). One of the distinctions between them is whether or not covalent bonds are formed (Wu et al., 2020).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic diagram of common methods for preparing injectable hydrogels. Injectable hydrogels can be roughly divided into two gel methods: physical cross-linking and chemical cross-linking reactions. The difference between them is whether or not covalent bonds are formed. Physical cross-linking is non-covalent bonding via reversible and instantaneous connections, including physicochemical or molecular entanglement interactions (hydrogen bonding, ionic or hydrophobic interactions). Chemical cross-linking forms covalent bonds in various chemical processes, including enzyme-mediated cross-linking, photopolymerization, click chemistry, Michael’s addition, Schiff base chemistry, and cross-linking agents. Adapted with permission of Wu et al. 2(2020).

1.2 Physical cross-linking

Hydrogels can be cross-linked via reversible networks or physical cross-links through physicochemical or molecular entanglement interactions, such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, ionic interaction, supramolecular chemistry, crystal formation, or charge condensation (Lu et al., 2018; Niemczyk et al., 2018). The mutual effects that occur in this hydrogel are fragile. However, they are numerous and lead to complex behaviors (Lynch et al., 2017; Bustamante-Torres et al., 2021; Muir and Burdick, 2021). Some injectable hydrogels by physical cross-linking are described below.

1.2.1 Hydrophobic interactions

Hydrophobic interactions (also known as hydrophobic bonding) play a significant role in the self-healing course of soft materials (Tu et al., 2019). This interaction is stronger than the van der Waals and hydrogen bond interaction. Hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts are usual in molecules that form gels through hydrophobic interactions. Hydrophobic interactions are constituted between non-polar parts to reduce their contact with water (Skopinska-Wisniewska et al., 2021).

1.2.2 Hydrogen bonding cross-linking

Hydrogen bonds can form cross-linking networks between hydrogen and electronegative atoms (He et al., 2019). Supramolecular hydrogels enhanced by multiple hydrogen bonds have good self-recovery, toughness, and recoverability as a driving force (Yu et al., 2021a).

1.2.3 Ionic interaction

The cross-linked hydrogel structure is formed when molecules with opposite electric charges interact electrostatically (Abdulghani and Morouço, 2019). Ion interactions have been widely used to physically cross-link natural polysaccharides, such as chitosan and alginate, to prepare hydrogels (Huang et al., 2017). Alginate can gelate in the presence of polyvalent cations such as Sr2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, Co2+, and Ba2+, which is related to cation binding through G blocks of alginate and the formation of so-called “egg boxes” (Lee and Mooney, 2012; Abasalizadeh et al., 2020). CaCl2 is the most commonly used ion cross-linking agent in alginate hydrogel. Due to the high solubility of CaCl2 in aqueous media, alginate gelation rates are too fast to control. In addition, reduced gel rate results in greater mechanical integrity and a more uniform structure. CaCO3 and CaSO4 can be used instead to slow down the gelling speed. In addition, a buffer containing phosphate (such as sodium hexametaphosphate) can be used because the phosphate group in the buffer competes with the carboxylic group of alginate in the reaction with calcium ions, thereby reducing gelation (Abasalizadeh et al., 2020; Piras and Smith, 2020; Hu et al., 2021a). Cai et al. (2021). successfully prepared an injectable hydrogel by in situ cross-linking sodium alginate with divalent cations released from strontium-doped bioglass. The hydrogel’s biocompatibility and mechanical properties promoted BMSC proliferation, cartilage-specific gene expression, and glycosaminoglycan secretion.

1.2.4 Supramolecular chemistry

Supramolecular chemistry hydrogels have been widely used in tissue engineering, bioelectronics, and drug delivery. It has good biocompatibility and biodegradation and contains many cell adhesion sites (Kim et al., 2011). As a key sense in supramolecular chemistry, self-assembly is mainly based on non-covalent interactions (hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, π-π stacking, and host-guest complexation) between molecules (Antoniuk and Amiel, 2016; Wang et al., 2020a). The substrate of supramolecular hydrogels, a basic molecular process, is usually non-covalent, structural, three-dimensional, responsive, dynamic, adaptive, and organized. Such molecular processes can easily interact with, interfere with, and even simulate cellular events in various biological systems (Zhou et al., 2017). Supramolecular interactions can promote physical cross-linking to form hydrogels in two ways. The first method is commonly used to create supramolecular materials, molecular gels made of small molecules with high aspect ratios, such as peptides. Once assembled, supramolecular stacks of small particles constitute long, typically rigid fibers. The second approach is that the interactions act as connections between polymer chains, including motifs based on host-guest complexation, metal-ligand ligands, and biomolecular binding (Mantooth et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2020). Cyclodextrin-mediated host-guest interaction is an effective material for hydrogel construction, mainly because of its bioavailability, ease of chemical modification, and high reversibility and specificity of inclusion complexes composed of many hydrophobic guest molecules (Antoniuk and Amiel, 2016).

1.3 Chemical cross-linking

The convergence of years of research has led to the development of mild chemistry that can be set at temperature, physiology, osmotic pressure, and pH while avoiding using toxic reagents. Chemical cross-linking depends on the formation of covalent bonds between the reactive groups grafted to the main chain of the polymerization, and it can occur under certain conditions (Flégeau et al., 2017). These conditions include click chemistry, Michael addition, disulfide cross-linking, enzyme-mediated cross-linking, silanization, Schiff base chemistry, photopolymerization, and cross-linking agents (Radhakrishnan et al., 2014; Piantanida et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021)

1.3.1 Click chemistry

Click chemistry includes copper-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition, copper-free click (strain-promoted azylene cycloaddition click, Diels-Alder click chemistry, oxime, mercaptan, and mercaptan alkyne), and pseudo click (Gopinathan and Noh, 2018; Li et al., 2021a). Click chemistry is widely used in constructing injectable hydrogels due to its mild reaction conditions, high chemical selectivity, and fast gelation time, without adding or producing cytotoxic cross-linking agents, chemical additives, and byproducts in the gelation process (Yao et al., 2020).

1.3.2 Michael addition

Michael addition reaction hydrogels are prepared by adding polymers containing thiol groups to α, β-unsaturated carbonyl polymers under standard conditions (Quadrado et al., 2021). PEG-based hydrogels based on the Michael addition reaction have been widely used in tissue engineering (Guo et al., 2021). Pupkaite et al. (Pupkaite et al., 2019) tried to overcome the shortcomings of partially injectable hydrogels, such as complex, overexpanding, potentially toxic cross-linking processes, or lack of self-healing and shear thinning. Mercaptan groups were introduced into collagen. The hydrogel was prepared by cross-linking with 8-arm polyethylene glycol maleimide. The hydrogel is cytocompatible and can be used to encapsulate and deliver cells.

1.3.3 Enzyme-mediated cross-linking

Enzyme cross-linking reactions are mild. Most enzymes catalyze reactions in water environments at neutral pH and moderate temperatures. This means that they can also be used to form hydrogels in situ, avoiding the loss of biological activity caused by natural polymers that cannot withstand the harsh chemical conditions required for crosslinking (Teixeira et al., 2012). Several enzyme-mediated injectable hydrogels are used for cartilage defect repairs, such as tyrosinase, lysyl oxidase, and transferase enzyme systems (Liu and Lin, 2019; Wang and Wang, 2021). HRP and H2O2 are the most common enzyme-mediated cross-linking agents by phenol partial carbon-oxygen/nitrogen bond or carbon-carbon bond oxidative coupling. They can easily control the physical properties of the hydrogel by changing their concentration (Ren et al., 2015). These hydrogels are formed in a matter of minutes. They showed excellent biocompatibility and supported chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation (Jin et al., 2010). Enzyme-mediated hydroxyapatite hydrogel has the advantages of injectable, non-cytotoxic, and rapid cross-linking (Jin et al., 2020). Zhang and his team proposed a biomimetic enzyme complex of ferrous glycine (Fe [Gly]2) and glucose oxidase for rapid (less than 5 s) and mild preparation of injectable tough hydrogels (Zhang et al., 2021a).

1.3.4 Schiff base chemistry

Schiff base chemistry involves the formation of dynamic covalent imine bonds by cross-linking aldehyde and amine groups. Schiff base chemistry has the advantages of being reversible, simple, pH-sensitive, and biocompatible (Xu et al., 2019; Sahajpal et al., 2022). For the formation of biopolymer hydrogels, the functions of hydrazones and imines are most commonly used to achieve dynamic cross-linking behavior (Muir and Burdick, 2021). Chen et al. (2021). prepared injectable HA hydrogels modified with methacrylate and aldehyde group through dynamic Schiff base reaction. The results showed that the hydrogel was easy to prepare quickly in situ, had good biocompatibility, promoted BMSC proliferation, and promoted the regeneration of rat cartilage.

1.3.5 Photopolymerization

Visible or near ultraviolet photopolymerization is one of the most widely studied gelation processes in the development of injectable hydrogels. Some types of hydrogels can be photopolymerized in vitro and in vivo by the interaction of photoinitiators with visible or ultraviolet light to generate free radicals and polymerize free radical chains (Meng et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Photopolymerization is a fascinating method with the following characteristics: 1) It is based on chemical reactions unaffected by water, making it suitable for use in aqueous media. 2) This is usually a very rapid process, allowing the synthesis of free-standing hydrogels in minutes or seconds. 3) It allows space and time control of the cross-linking process. 4) It is very little cytotoxic under the appropriate conditions and thus does little harm to cell survival and proliferation (Nicol, 2021; Pierau and Versace, 2021). The researchers altered collagen with Methacrylamide to photo-crosslinking under ultraviolet stimulation, enabling fast in situ gelation (Zhang et al., 2020a). GelMA injectable hydrogel is formed by introducing a double bond into a gelatin polymer chain that rapidly forms a hydrogel under light initiation. The blue light initiator lithium phosphonate makes the gelation approach faster and the preparation approach easier (Yue et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2021c).

1.4 Comparison of physical and chemical cross-linking

The ideal injectable hydrogel has several requirements, including: 1) no evil byproducts are produced after gelation; 2) solubility of the gelated aqueous solution under physiological conditions (pH, temperature, and ion concentration); 3) the rate of gelation is rapid enough to meet the clinical efficacy. Nevertheless, in the presence of an additional agent such as a cell or bioactive molecule, there is adequate time for appropriate mixing and injection; 4) Suitable rate of biodegradation (Salavati-Niasari and Davar, 2006; Naahidi et al., 2017; Elkhoury et al., 2021). Both physical and chemical gelation must fulfill the above requirements. However, both physical and chemical techniques have benefits and deficiencies. Therefore, the most suitable method should be selected to design injectable hydrogels.

Compared to chemical cross-linked hydrogels, physically cross-linked hydrogels typically exhibit lower mechanical properties because the physical interactions are reversible and weak, so the hydrogels that form loosen easily when physical conditions (temperature, ionic strength, electrolyte, and pH) change (Mathew et al., 2018). For example, thermosensitive cross-linked hydrogels are one of the most widely studied injectable hydrogels in tissue engineering (Xu et al., 2020; Torres-Figueroa et al., 2021). Sol-gel transformations occur during hydration and dehydration at different temperatures (Shi et al., 2021a). The CST of such hydrogels is close to the body temperature during the sol-gel transition. The polymer chain expands in a random coil conformation due to its hydrophilic interaction with water molecules. However, when the system is heated beyond CST, the polymer chains collect and collapse due to a major hydrophobic interaction between the polymer chains (Sala et al., 2017; Dethe et al., 2022). Different PEG-based polymers, Poloxam and NIPAAm, are typical examples of thermosensitive hydrogels. The polar groups in the hydrogel can form hydrogen bonds with the water molecules between the polymer chains under CST, making it soluble. Above CST, the polymer chain contracts and becomes insoluble and hydrophobic, resulting in gelation (Eslahi et al., 2016).

Furthermore, ion-sensitive injectable hydrogels for cartilage defect repair have been developed. By adding Ca2+, the alginate solution can easily constitute hydrogel through ion cross-linking through the calcium bridge between the guluronic acid residues on nearby chains (Hu et al., 2019). pH-responsive hydrogels consist of polymers with basic or acidic groups, and their mechanisms involve dissociation and binding with hydrogen ions in response to ambient pH. This hydrogel has been extensively studied in drug delivery applications because the pH curves of pathological tissues (such as infection, inflammation, and cancer) differ from those of normal tissues (Eslahi et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2020a).

These physically cross-linked injectable hydrogels can be converted from liquid to gel and organized in situ hydrogels when injected into the body without additional cross-linking agents, chemical reactions, or environmental treatments (Gao et al., 2020). Physical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, electrostatic attraction) or reversible chemical bonds (e.g., imine bonds) can form cross-linked pre-gel hydrogels whose structures are reversible (Arkenberg et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2020). Pre-gelated hydrogels are in vitro-formed hydrogels that can be injected at the target and self-heal (Oliva et al., 2017). Pre-gelated hydrogels are injectable due to their self-healing and shear thinning (Riley et al., 2019). As the shear rate increased (during injection), the stickiness of the hydrogel decreased dramatically, reflecting the shear-thinning behavior (Thambi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021d). Although the injection forces may interfere with the cross-linking structure and trigger the gel-sol transition, the following self-healing process can rebuild the gel after removing the strain (Liu and Hsu, 2018). Shear-thinning injectable hydrogels protect encapsulated cells from high shear forces, improving the effectiveness of cell-based therapies (Thakur et al., 2016).

On the other hand, chemically cross-linked gels typically have stronger mechanical properties because covalent bonds are permanent and rigid (Zhao et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2022). The main drawback of chemical cross-linked hydrogels is the problem of cytotoxicity, which binding reactive compounds and light radiation may cause. Fortunately, recent developments in chemical cross-linking methods have enabled good biocompatible hydrogels to be gelated under mild reaction conditions (Lee et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

Advanced injectable hydrogel preparation methods need to be further developed to improve physiological stability and mechanical properties, reduce adverse effects and cytotoxicity of hydrogels in vivo, and ensure gelation occurs at a rate suitable for clinical practice. Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages. Future research will explore how to correctly select the appropriate method and improve the existing manufacturing method.

1.5 Multiscale structure of injectable hydrogels

The bearing capacity of materials is a crucial characteristic in cartilage tissue engineering. Cartilage reduces friction, shear, and compression forces between bones. Its modulus is 0.5–2 MPa (Cross et al., 2016). Hydrogel has a stiffness of two orders of magnitude lower than natural cartilage (Li et al., 2019). Poor mechanical properties and limited functionality of traditional injectable hydrogels hinder their application in cartilage (Song et al., 2015). In addition to high water content and biocompatibility, the rigid multiscale hydrogel system also has super tensile property and large fracture energy (Xin, 2022). Multiscale injectable hydrogels with high mechanical strength and stability are of particular interest in cartilage tissue engineering (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The schematic diagram depicts injectable hydrogels with different structures for cartilage regeneration engineering (A). Traditional single polymer networks. (B–F). Different multiscale structure of injectable hydrogels. Reproduced with permission of Vega et al. (2017).

1.6 Interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels

The IUPAC defines IPN as a unique polymer mixture consisting of two or more cross-linked networks whose parts are intertwined but not covalently connected and which cannot be separated unless the chemical bond breaks (Matricardi et al., 2013). IPN hydrogel was exploited to improve its mechanical properties (Zhang et al., 2015). Compared with hydrogels formed by a single polymer model, hydrogels with IPN often exhibit superior mechanical properties (Zoratto and Matricardi, 2018). Shojarazavi et al. (2021) used an IPN structure combined with silk fibroin nanofibers, alginate, and sodium cartilage ECM to enhance the mechanical properties of ECM to achieve the mechanical stiffness required for cartilage repair.

1.7 Semi-interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels

Unlike IPN, the chains of the second type of polymer in Semi-IPN are only dispersed in the network formed by the first type of polymer, rather than forming another network interpenetrating with the first type of polymer (Aminabhavi et al., 2015). IUPAC defined Semi-IPN as a polymer consisting of one or more networks and branched or linear polymers characterized by the penetration of at least one network at the molecular scale by at least some branched or linear macromolecules (Rinoldi et al., 2021). Furthermore, branched or linear polymers composed of Semi-IPN can be separated from the composed polymer network without breaking the chemical bond (Dhand et al., 2021). Thermosensitive hydrogels based on the chitosan/β-glycerophosphate system are widely used in cartilage regeneration engineering because of their good injectable properties, rapid gelation at the injection site, and ability to repair cartilage defects (Saravanan et al., 2019). However, due to their physical cross-linking network, chitosan/-glycerophosphate hydrogels exhibit high degradation rates and poor mechanical properties under physiological conditions, limiting their application (Jalani et al., 2015; Saravanan et al., 2019). Panyamao et al. (2020) used GE covalent cross-linking and pullulan Semi-IPN to improve the mechanical properties and swelling capacity of injectable thermosensitive hydrogels ground on the chitosan/β-glycerophosphate organization. Moreover, Wang et al. (2020a) prepared an injectable Semi-IPN hydrogel based on HA-SH and BPAA-AFF-OH supramolecular short peptides. The injectable hydrogel exhibits reliable mechanical strength. Moreover, compared with HA-SH hydrogel, it can enhance the expression of chondrogenesis-related genes and matrix secretion and further promote the maintenance of the hyaline cartilage phenotype.

1.8 Double networks hydrogels

Double-network hydrogels consist of two cross-linked networks with significantly different mechanical properties. The first network provides a rigid structure, and the second network is malleable. This is due to some structural parameters, namely the rate of the two hydrogel components, cross-linking density, swelling rate, and molecular weight allocation of the network polymer (Jonidi Shariatzadeh et al., 2021; Xin, 2022). Wang et al. 2(2021b) studied a double injectable hydrogel based on HAMA and GelMA. The double hydrogel combines the strong mechanical properties of HAMA with GelMA’s role in chondrocyte phenotype maintenance and ECM formation.

1.9 Dual networks hydrogels

Unlike a double network using two different mechanical properties materials, a dual network is defined as two cross-linked materials to form the same network and have a similar cross-linking mechanism. Although the dual network does not have the toughness of the double network, each material in the dual network can inject other useful properties into the hydrogel. For example, one material attracts cells and encourages migration into the injectable hydrogel, while the other effectively binds to surrounding tissue (Vega et al., 2017). Kim et al. (2021). (investigated poly(N‐isopropyl acrylamide) and PLL-based dual network injectable hydrogels encapsulating articular chondrocytes and MSCs. The model experiment of cartilage transplantation in vitro showed that dual hydrogel could promote cartilage defect repair.

1.10 Nano/micro-composite hydrogels

Mixed hydrogels integrated with nano/micron composites are networks of hydrated polymers physically or chemically cross-linked with N/MPs or other nano micron structures (Mehrali et al., 2017; Kouser et al., 2018).

N/MPs have excellent mechanical properties, surface reactivity, bioavailability, and a larger surface-to-volume ratio (Asadi et al., 2018; Zinatloo-Ajabshir et al., 2018; Piantanida et al., 2019; Ahmadian-Fard-Fini et al., 2020). The hard N/MPs enhance the soft organic polymer matrix, and the resulting nano/micron composites hydrogel can exhibit novel or enhanced biological, mechanical, conductive, optical, or magnetic properties (Motahari et al., 2015; Motealleh and Kehr, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017; Ravari et al., 2021). Inorganic materials such as clay, graphene, CNCs, hydroxyapatite, and metal nanoparticles can be used as fillers to enhance the hydrogel matrix (Davar et al., 2010; Zazakowny et al., 2016; Asadi et al., 2018; Zinatloo-Ajabshir and Salavati-Niasari, 2019). Nano-silicates with high cellular and biocompatibility could form shear-thinning hydrogels when combined with long-chain polymers (Thakur et al., 2016; Lokhande et al., 2018). POEGMA precursor polymer was physically cross-linked with CNCs, which made CNCs have excellent hydrogel dispersibility and significantly enhanced gel mechanical properties. Other gel properties, including swelling, degradation kinetics, and gelation rate, also changed significantly (De France et al., 2016). GelMA injectable hydrogel microspheres prepared by microfluidic technology are widely used in cartilage repair due to their enhanced high injectivity, structural stability, and uniform size (Han et al., 2021). Lei and his team reduced articular cartilage friction by coating the surface of injectable hydrogel microspheres with liposomes to form a self-renewing hydration layer through friction and wear. In addition, the release of an autophagy activator (rapamycin) promotes cartilage repair (Lei et al., 2022).

Moreover, the N/MPs adsorbs and retain essential stimulating factors, prolonging their release time due to the larger surface-to-volume ratio and high encapsulation efficiency of stimulating factor (Amiri et al., 2017; Nagahama et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2018; Ishihara et al., 2019; Bian et al., 2021; Zewail et al., 2021; Luu et al., 2022; Seo et al., 2022). Wang et al. (2020b) loaded the water-soluble antibiotic isoniazid into a cross-linked PEG network and encapsulated the hydrophobic antibiotic rifampicin into mesoporous silica nanoparticles. The addition of nanoparticles can significantly adjust and enhance injectable hydrogels' mechanical strength and elasticity. The release time of rifampicin was significantly longer than isoniazid and promoted cartilage repair. Lin et al. (2021b) developed PLGA microspheres loaded with TGF-β3, and injectable hydrogel-coated PLGA microspheres could sustainably release TGF-β3. This synthetic micron composite injectable hydrogel system regulates chondrocyte differentiation and biosynthesis.

The electroactive nanomaterials promote the migration, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of preosteoblasts and MSCs. Aniline oligomers (Penta aniline or tetra aniline) are the most commonly used conductive oligomers, with the advantages of good biocompatibility, low cost, easy synthesis, good stability, easy processing, electrochemical behavior similar to conductive polymers, and due to low MW, easy to be eliminated from the body by renal excretion (Wang et al., 2016; Hassanpour et al., 2017; Zinatloo-Ajabshir et al., 2020; Monsef and Salavati-Niasari, 2021).

2 Material of injectable hydrogels

Injectable hydrogels are generally required to have the following characteristics, including low toxicity, adequate biocompatibility, support for cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation, biodegradability, appropriate degradation rate, and fine structure similar to the tissue or organ to be repaired, and controlled release of biomolecules (Jiang et al., 2021). Strategies for cartilage repair based on natural and synthetic injectable hydrogels and their combination were studied.

2.1 Natural polymers

Natural polymers can be broadly divided into three categories: those based on proteins, polysaccharides, and protein nucleotides. Because ECM is a complex combination of fibrin (such as laminin, collagen, and ficonin) and hydrophilic proteoglycan. A simple and effective way to simulate ECM is to prepare injectable hydrogels using natural polymers that mimic many of its characteristics (Farrell et al., 2017). Natural polymers have several advantages over synthetic polymers:1) they are more biocompatible; 2) They can contain cell-binding motifs, realize cell adhesion, proliferation, and biological activity cues, and influence cell behavior; 3) They can exhibit fibrous structures that mimic the ECM of natural tissues; 4) They can be recognized and processed metabolically by the body, allowing cells to reshape them along with cell-secreted ECM deposition (Gomez-Florit et al., 2020). On the other hand, natural polymers have low mechanical strength and vary from batch to batch and from natural source to natural source, making their molecular weight, chemical structure, and rate of degradation difficult to control (Yan et al., 2014; Coenen et al., 2018).

2.2 Protein polymer

2.2.1 Silk fibroin

SF polymers can be easily processed into various forms, including micron/nanoparticles, membranes, films, fibers, and mainly hydrogel scaffolds (Zheng et al., 2022). Chemical and physical methods can prepare SF injectable hydrogels through the β-sheet formation. Various chemical reagents, including alcohols, acids, salts, and surfactants, have been used as SF crosslinkers (Yuan et al., 2021a).

2.2.2 Gelatin

Gelatin is a commercial biomaterial whose biological properties are widely used in biomedical engineering due to its similarity to more expensive collagen as an adhesive protein (Tonda-Turo et al., 2017). Gelatin is produced by regional hydrolysis of collagen and can promote cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation due to RGD sequence in its structure (García-Fernández et al., 2020). In addition, one of the main characteristics of this water-soluble protein is its thermal response, with reversible sol-gel transformations occurring when cooled above the critical solution temperature (25–35°C). Gelatin is therefore widely used in cartilage tissue engineering (Echave et al., 2019).

2.2.3 Collagen

Two-thirds of the dry weight of the adult joints cartilage is collagen. The fibrous network of developing cartilage is a copolymer of collagen XI, IX, and II and small amounts of other types of collagen (Eyre, 2004). Varieties of combinations of collagen with other natural polymers like inulin, combinations of fibrin, alginate, and gelatin have been transformed into formulations for injectable hydrogels, enabling in-situ formation (Rigogliuso et al., 2020).

2.3 Polysaccharide polymer

2.3.1 Alginate

Alginate is a polysaccharide extracted from brown seaweed and composed of α-l-guluronate (G block) and β-D-mannuronate (M block) copolymers linked by 1, 4-glycosidic bonds. G block of alginate is cross-linked with divalent cations such as Ba2+ and Ca2+ to form gel (Balakrishnan et al., 2014). It is widely used due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ease of manufacture. However, alginate lacks the property of cell adhesion. Alginate was mixed with other polymers for cartilage repair to improve its biological properties (Jaikumar et al., 2015).

2.3.2 Chitosan

Chitosan natural polymer is a widely available polysaccharide created by completely deacetylating chitin, a structural component extracted from insect and crustacean bones. Importantly, chitosan-based materials have received much attention as hydrogels because of their good cellular compatibility, pH sensitivity, and biodegradability. In general, chitosan could dissolve in acidic solutions, and its viscosity properties can be easily adjusted by adjusting the concentration (Zheng et al., 2022). The insolubility of chitosan in water limits its use. Therefore, many studies have focused on soluble chitosan derivatives (Fattahpour et al., 2020). For example, chitosan becomes a thermosensitive polymer when mixed with polyol phosphate salts like β -glycerophosphate (BGP) (Panyamao et al., 2020).

2.3.3 Hyaluronic acid

HA is the primary component of glycosaminoglycan in ECM. It consists of repeated disaccharide units of n-acetyl-D-glucosamine and β -D-glucuronic acid, alternately linked by β-1,4 and β-1,3 glycosidic bonds (Graça et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021b). Natural HA does not affect cell adhesion or gel formation. Hence, it is necessary to chemically alter the functional groups of HA, adjusting their physical, chemical, or biological properties according to special requirements of specific applications (Zaviskova et al., 2018). In the absence of chemical cross-linking agents, hydrogels are formed by Schiff bases between the amino group of ethylene glycol-chitosan and the aldehyde group of oxidized hyaluronate. These hydrogels show good bio durability and compatibility under physiological cases, and they may be a potential injectable cell delivery system in cartilage tissue engineering (Kim et al., 2017).

2.3.4 Agar

Agar is a water-extracted cell-wall polysaccharide from Gracilariaceae and Gelidiaceae plants of seaweeds, consisting mainly of (1–3) 3, 6-hydroxy-lactose repeated units and alternating (1–4) D-galactose. Agar is solvable in water at temperatures beyond 65°C and forms a gel between 17 and 40°C (Tonda-Turo et al., 2017). Agar and gellan gum promote cartilage regeneration by inhibiting inflammatory mediators and inducing chondrogenesis and autophagy-related gene expression (Heo et al., 2020).

2.3.5 Gellan gum

Gellan gum is a bacterial polysaccharide extracted from Sphingomonas elodea. Its main glycoside chain is a repeating tetrasaccharide unit, each repeating unit contains one acetate and one L-glyceride, and one esterified substituent occurs in every two sequences (Oliveira et al., 2021). Gellan gum can form a thermally reversible injectable gel with no cytotoxicity in different test environments. It is commonly used in the food industry and has previously been used for drug delivery in the biomedical field. Gellan gum can effectively regenerate hyaline cartilage tissue in the defect (Oliveira et al., 2010). Choi et al. (2020) loaded 6-(6-amino-hexyl) amino-6-deoxy-β-cyclodextrin onto the Gellan gum chain to reduce gel temperature, enhance physicochemical properties, and improve drug delivery efficiency and release.

2.3.6 Cellulose

The physical capabilities of cellulose depend on the presence of three hydroxyl groups (OH) at the C-6, C-3, and C-2 positions. Cellulose injectable hydrogels made from carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), methylcellulose (MC), and hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC) have good mechanical properties and are biocompatible (Zhang et al., 2021b).

2.3.7 CS

CS is a GAG consisting of alternating units of (β-L, 4) n-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and β-1,3-linked glucuronic acid (Glca). The residues of galactosamine at position 4 or 6 can be sulphated (Yuan et al., 2021b). Furthermore, CS is the most abundant GAG in the human body and the main component of chondrocyte ECM, which has attracted great attention as a biomaterial for cartilage defect repair. CS in cartilage has multifold key roles, including supporting chondrogenesis, providing resistance to stress, chondrocyte signaling, and intercellular communication (Thomas et al., 2021).

2.4 Protein nucleotide polymer

2.4.1 Deoxyribonucleic acid

DNA is a brilliant molecule because of its biocompatibility, minimal toxicity, precise molecular recognition, and easy programming (Li et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2022). Physical tangles between DNA strands or chemical connections between DNA molecules can be used to create DNA hydrogels. Chemically, polymers are held together by covalent bonds, which confer great mechanical strength and environmental stability (Kahn et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020b; Khajouei et al., 2020). DNA injectable hydrogels are widely used in cartilage repair engineering due to their injectable properties, adjustable mechanical properties, and good permeability (Yan et al., 2021).

2.5 Extracellular matrix

ECM hydrogel provides cells with a natural adhesion surface and superior biological activity. Preparing acellular ECM hydrogels can maximize the retention of growth factors and low molecular weight peptides present in natural ECM (Gong et al., 2021). At present, bionic and tissue-specific injectable hydrogels are prepared from various acellular ECM (amniotic membrane, cartilage, bone, heart, and lung) for cartilage regeneration engineering (Bhattacharjee et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2021; Bhattacharjee et al., 2022). Bordbar et al. (2020) developed an injectable hydrogel derived from acellular sheep chondrocyte ECM. The cells embedded in the hydrogel can differentiate into chondrocytes. Sevastianov et al. (2021) compared the effects of injectable collagen hydrogels and acellular porcine articular cartilage injectable hydrogels on rabbit BMSCs differentiation. Injectable collagen hydrogel is more beneficial in stimulating BMSCs to repair cartilage in vivo, and injectable porcine articular cartilage is an inducer for BMSCs to form chondroid tissue in vitro.

2.6 Synthetic polymer

Synthetic polymer hydrogels have been developed to meet the need for more alternative materials in tissue engineering. Synthetic polymers mainly include polymers based on PLA, PGA, PLGA, PCL, PVA, and polyester copolymers (Werkmeister et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2014). Synthetic polymers of glycopeptides mimic natural glycoproteins or glycopeptides and have great potential in biomedical applications. The extracts of glycopeptide copolymer and glycopeptide hydrogel showed good cytocompatibility in vitro. When injected subcutaneously into rats, glycopeptide hydrogels formed rapidly in situ (Ren et al., 2015). A one-component synthetic methacrylate type II collagen can be photo-crosslinked to form a firm injectable hydrogel. MSCs encapsulated in this hydrogel showed good activity and could coagulate and undergo chondrogenesis (Behan et al., 2022).

2.6.1 Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid

PLGA is a synthetic polypeptide formed by natural l-glutamic acid through an amide bond, biodegradable, avoids antigenicity or immunogenicity, and is non-toxic and hydrophilic. In addition, abundant side-chain carboxyl groups on the PLGA chain enable it to undergo chemical modification. These properties make PLGA an ideal biomedical material (Yan et al., 2014).

2.6.2 Polyethylene glycol

PEG is a non-toxic, non-immunogenic, and pollution-resistant synthetic polymer widely used as a substrate in tissue engineering, such as articular cartilage, bladder, and nerve tissue regeneration (Li et al., 2021c). A PEGDA hydrogel involved in chondroitin sulfate binder has entered clinical trials for repairing cartilage defects and has shown improved results in combination with microfractures (Qi et al., 2018; Qi et al., 20182021).

2.6.3 Polyglycolic acid

PGA is a polypeptide secreted by Bacillus subtilis natto. Many carboxylic acid groups (-COOH on the side chain of -PGA) are easily functionalized to achieve precise functions. The ultimate degradation product of PGA is glutamate, a component of collagen. Due to its excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity, PGA is used to prepare hydrogels with various functions for tissue engineering matrix, especially cartilage (Wei et al., 2022).

2.7 Natural/synthetic polymer

Synthetic polymers are easy to manufacture and replicate. However, they have poor biodegradability and biocompatibility. Naturally derived polymers are widely used in injectable hydrogels for repairing cartilage defects due to their excellent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and similar 3D microenvironment in vivo. However, rapid degradation, poor mechanical properties, and enhanced microenvironment for cell proliferation and differentiation are challenges in practical applications (Jian et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2021). The combination of natural and synthetic polymers can play to their respective strengths and compensate for their weaknesses (Peng et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021c). Yang et al. (2021) mixed injectable hydrogels of 2%DF-PEG/1.5%GCS, which significantly improved the mechanical properties and biocompatibility of hydrogels, and the hydrogels loaded with ADSCs promoted cartilage repair. Shi’s team researched and prepared an injectable hydrogel with natural antioxidant capacity. A dynamic covalent bond between PVA and phenylboronic acid grafted to HA-PBA forms hydrogels, which are further stabilized by secondary cross-linking between the acrylate portion of the HA-PBA and the free sulfhydryl group in the vulcanized gelatin (Shi et al., 2021b). The existence of a dynamic covalent bond contributes to the shear thinning of hydrogels, which makes hydrogels have suitable printing. Hydrogels protected coated chondrocytes from ROS-induced upregulation of Chondrocyte-specific catabolic genes (MMP13) and downregulation of anabolic genes (COL2 and ACAN) after incubation with H2O2.

2.8 Cells and stimulating factors integrated into injectable hydrogels

Injectable hydrogels can integrate appropriate cells and stimulating factors to stimulate damaged tissue’s original microenvironment and thus help regenerate damaged cartilage (Yang et al., 2017; Ngadimin et al., 2021). Injectable hydrogels act as the matrix to promote cell-cell interactions and cell-matrix interactions, while stimulating factors are part of signals that mediate cell adhesion and migration to scaffolds. Hence, cells and stimulating factors are important for applying injectable hydrogels in tissue engineering, as they play a vital role in cell differentiation and tissue growth (Sun et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2020; Stampoultzis et al., 2021). Living tissue cells migrate from the surrounding to the hydrogel and interact within the hydrogel to reconstruct the desired tissue at the implant site. Injectable hydrogels can also transport cells that interact with protocell populations and deliver growth factors or other therapeutic biomolecules to recapture abnormal biology (Dimatteo et al., 2018).

2.9 Cell source and cell capsulation

The requirements of injectable hydrogel-encapsulated cells for cartilage repair are as follows: 1) they can constitute cartilage tissue; 2) suitable for clinical application, that is, the source is vast, the trauma is minor, and the extraction is easy; 3) after many passages, they can obtain the required number of cells while maintaining the cartilage phenotype (Kwon et al., 2019). Embedding cells into injectable hydrogels can be achieved by embedding cells during gel formation or by inoculating cells into prefabricated porous gels (Armiento et al., 2018; Jabbari and Sepahvandi, 2022).

2.9.1 Chondrocytes

ACI has been successfully used to promote articular cartilage regeneration. Hu et al. 2(2021b). loaded chondrocytes in IPN injectable hydrogel composed of chitosan/HA/Si-HPMC. The chondrocytes proliferated well in vitro, promoting cartilage defect repair in rat models in vivo. Chiang et al. (2021) prepared an injectable HA-PAA hydrogel with magnetic navigation and glutathione release. The chondrocytes embedded in the hydrogel proliferated and differentiated at the site of cartilage damage through magnetic interaction of internal iron nanoparticles and adhesion of CD44 receptors on HA chain. The rabbit cartilage defect model produced uniform and smooth, regenerated cartilage 8 weeks after hydrogel implantation, and the columnar arrangement of chondrocytes in the deep tissue was similar to that of normal chondrocytes (Chiang et al., 2021).

However, some shortcomings still need to be addressed, such as the low number of cells that are difficult to extract and harvest. With the increase of amplification generations, chondrocytes lose their chondrogenic phenotype. Eventually, this results in lower cartilage repair (Cai et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2022). Autologous chondrocytes are mainly derived from natural cartilage in the non-weight-bearing region of the joint, which may lead to donor site disease (Chen et al., 2018). hNCs are a clinically valuable source of cartilage tissue regeneration. hNCs are relatively easier to obtain through a marginally invasive collection program during septal surgery for nasal obstruction, with a lower incidence than chondrocytes obtained from articular cartilage (Lim et al., 2020).

2.9.2 Stem cells

Due to the insuperable limitations of chondrocytes in the treatment of damaged cartilage, a significant amount of research has focused on the research of stem cells in recent years. Stem cells are self-renewing cells that, due to their undifferentiated biology, can produce more stem cells through mitosis or can differentiate into specialized cells (Ma et al., 2018; Yin and Cao, 2021). Various types of stem cells such as ESCs, CSPCs, MSCs, and iPSCs are used to treat cartilage defects (Deng et al., 2020; Johnstone et al., 2020).

2.9.3 Embryonic stem cells

ESCs are derived from inner cell masses of blastocyst embryos and are essentially pluripotent stem cells with the ability to differentiate into all cell types in the body, potentially providing an unlimited supply of cells for cell and tissue therapy and replacement (Toh et al., 2011). However, using ESCs is linked with ethical issues, as induction of ESCs destroys embryos. In addition, ESCs will form teratoma. Because of safety concerns, it is inappropriate to use ESCs for cartilage tissue engineering at this time (Im and Shin, 2015).

CSPCs: Articular cartilage has a single cell type, chondrocytes. Although lacking intrinsic repairability, articular cartilage has been proved to contain a population of stem or progenitor cells, similar to those discovered in many other tissues, thought to be relevant to maintaining tissue homeostasis (Jiang et al., 2016). These CSPCs have been found in human, bovine, and horse articular cartilage (Jiang and Tuan, 2015). Li et al. verified the injectable hydrogels based on THA and HB-PEG multi-acrylate macromer containing CSPCs. The secretion of extracellular chondrocyte ECM was enhanced under chondrogenic conditions, and inflammatory gene expression was down-regulated (Li et al., 2020b).

MSCs are undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells characterized by the ability to self-renew when exposed to specific growth signals (Mohamed-Ahmed et al., 2018; Gonzalez-Fernandez et al., 2022). MSCs could differentiate into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, muscle cells, and adipose cells, providing great potential for cartilage tissue engineering. They can be collected from tissues such as bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, adipose, amniotic fluid, pulp, synovium, and even breast milk (Deng et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2015; Mohamed-Ahmed et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2022). MSCs also have immune-enhancing and immunosuppressive effects on the deficiency of primary histocompatibility class II antigens and the secretion of helper T cell type 2 cytokines (Ding et al., 2021).

In particular, BMSCs are considered important seed cells in the treatment of cartilage injury due to their advantages of extensive sources, easy access, strong proliferation ability, significant multidirectional differentiation potential, and the ability to regulate inflammation (Muscolino et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022a). Ji et al. studied a temperature-sensitive GM-HPCH injectable hydrogel loaded with BMSCs and TGF-β1. Composite hydrogels can promote the migration of BMSCs, increase the expression of migrated genes, promote the differentiation of BMSCs cartilage, and effectively repair cartilage (Ji et al., 2020). However, ADSCs showed lower levels of immunogenicity than BMSCs. ADSCs showed better stability in the treatment of osteoarthritis. This finding was supported by single-cell analysis results, which clearly showed that ADSCs were more conspecific than BMSCs (Wu et al., 2013; Mazini et al., 2019). Compared with in vitro culture conditions, the cell microenvironment in vivo can be relatively deficient in oxygen and nutrition. The failure of transplanted cells to adapt to environmental changes may be one of the reasons for the low survival rate of MSCs. Under serum deprivation and hypoxia, ADSCs were more resistant to apoptosis, implying that they may be better adapted to post-transplant conditions (Xu et al., 2017a; Zhou et al., 2019). Boyer et al. and Dehghan-Baniani et al. studied injectable hydrogels loaded with ADSCs in vivo and in vitro, promoting cartilage defect repair (Boyer et al., 2020; Dehghan-Baniani et al., 2020).

hUCMSCs are also an alternative stem cell source for cartilage tissue engineering. Compared with BMSCs, regarded as standard stem cell sources, which produced more intense type II collagen staining, the hUCMSCs produced more type I collagen and aggregative proteoglycans (Talaat et al., 2020).

iPSCs: IPSCs refer to the reprogramming of somatic cells with the potential to be self-renewing and pluripotent stem cells, similar to ESCs, but without the ethical issues and immune response that plague ESCs (Tsumaki et al., 2015; Castro-Viñuelas et al., 2018). In contrast to MSCs' limited differentiation ability after the fourth generation, IPSCs can provide abundant unlimited cell sources with low tumorigenicity (Chang et al., 2020). The potential of IPSCs to differentiate into chondrocytes and its application in cartilage defect modeling have been successfully demonstrated in several researches (Zhang et al., 2020c; Csobonyeiova et al., 2021). He et al. (He et al., 2016) successfully cultured mouse IPSCs to differentiate into chondrocytes based on the sodium alginate hydrogel platform. Xu et al. (Xu et al., 2017b) inoculated human IPSCs with PLCG hydrogel scaffolds and showed repaired chondroid tissues in rabbit cartilage defect models without teratoma.

2.10 Stimulating factor

Stimulating factors play an important role in regulating cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation (Zhong et al., 2016; Fan et al., 2020). Many studies have revealed that many cytokines are generally involved in the chondrogenic differentiation of stem cells and maintenance of chondrocyte phenotypes, IGF-1, TGF-β1 or TGF-β3, BMP-2, BMP-4 or BMP-7, and GDF-5 (Campos et al., 2019). Moreover, through genetic engineering to enhance the expression of biologically active molecules, gene therapy offers an alternative method for locally delivering the appropriate stimulus (Huang et al., 2018). Due to the fast clearance of drugs in the joint, much traditional cartilage repair drug therapy has limited efficacy. Injectable hydrogels can maintain drug release and prolong drug retention in the articular cavity. Many studies have been done on injectable hydrogels loaded with drugs (Li et al., 2019).

2.10.1 Transforming growth factor-β

The TGF-β family plays a crucial role in homeostasis and the development of various tissues. Signaling in this protein family mainly activates SMAD-dependent transcription and signaling and SMAD-independent signaling through MAPK such as TAK1 and ERK (Thielen et al., 2019). They regulate cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis and control the degradation and synthesis of ECM. In mammals, there are three isotypes of TGF-β. TGF-β is an inactive soluble protein complex composed of TGF-β dimer, latent TGF-β binding protein, and pre-peptide latency (Blaney Davidson et al., 2007). TGF-β1 is abundant in natural cartilage and controls cartilage ECM production by affecting the synthesis of fibronectin, proteoglycan, and collagen (Zheng et al., 2022). Zhang et al. 2(2021b) developed an injectable hydrogel system based on cross-linked thiolated chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose as carriers for TGF-β1 in cartilage tissue engineering applications. At 8 weeks postoperatively, hydrogels loaded with TGF-β1 showed excellent repairability in a rat model of full-thickness cartilage defects of the knee. TGF-β3 is also shown to have chondrogenic properties (Martin et al., 2021). Lin et al. 2(2021b) demonstrated in vitro that injectable hydrogels loaded with TGF-β3 promoted the expression of chondrogenic genes (Col-2α and ACAN) and decreased the expression of osteogenic genes (Col-1α) in chondrocytes.

2.10.2 Bone morphogenetic protein

BMPs are protein molecules secreted by varieties of cells and are members of TGF-β superfamily. BMP plays a vital role in cartilage and bone formation and is named after its ability to induce cartilage and bone (Deng et al., 2018). BMP promotes SOX9 expression in chondrogenic MSCs. BMP acts upstream of SOX9, and SOX9 is critical for BMP-induced chondrogenesis. SOX9 and BMP participate in a positive feedback loop (Pogue and Lyons, 2006).

2.10.3 Growth/differentiation factor-5

GDF-5 is also a member of TGFβ superfamily. It is a large precursor protein consisting of two main domains: the active C-terminal domain and the N-terminal precursor domain with signal sequences and cleavage sites. GDF-5 overexpression can promote chondrogenesis, which improves MSC adhesion and chondrocyte proliferation (Sun et al., 2021). However, GDF-5 promotes osteogenesis and hypertrophy, limiting its therapeutic effect on cartilage repair. Therefore, it is better to control the anabolism and anti-catabolism of GDF-5 on chondrocytes and apply it to cartilage tissue engineering (Mang et al., 2020).

2.10.4 Insulin-like growth factor-1

IGF-1 is an anabolic growth factor that promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis and is vital in chondrogenesis and homeostasis. IGF-1 is a crucial factor promoting cartilage matrix anabolism in synovial fluid and serum. In addition to stimulating ECM production, IGF-1 can stimulate MSCs proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation (Wen et al., 2021). Many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of IGF-1 in articular cartilage repair, and it is dose-dependent (Wei et al., 2020). High-dose IGF-1 is more conducive to the formation and integration of cartilage regeneration, while low-dose IGF-1 is more conducive to subchondral bone (Zhang et al., 2017).

2.10.5 Platelet-rich plasma

PRP is rich in various growth factors, cytokines, and proteins, and many studies have demonstrated the potential effectiveness and excellent biocompatibility of PRP for cartilage defect repair (Yan et al., 2020). PL is a natural GFs pool consisting of TGF-β1, TGF-β3, IGF-1, and VEGF and can be prepared by simple PRP thermal cycling. Due to the removal of platelet fragments by gradient centrifugation, the immunogenicity of PL is lower than that of PRP (Li et al., 2021b). Tang and his team encapsulated PL using EPL and heparin NPs into injectable hydrogels. The injectable hydrogel ameliorated early cartilage degeneration and promoted late cartilage repair in rats with knee arthritis (Tang et al., 2021).

2.10.6 Kartogenin

KGN is a stable, nonprotein small molecule with a structure of 2- [(4-phenyl) carbamoyl] benzoic acid that induces the differentiation of BMSCs into chondrocytes regulating the CBFβ-RUNX1 signaling pathway (Yuan et al., 2021b). It is more effective than growth factors in inducing cartilage regeneration and has been processed and applied in various forms in cartilage tissue engineering (Cai et al., 2019). Dehghan Baniani et al. (Dehghan-Baniani et al., 2020) incorporated KGN into a thermosensitive injectable chitosan hydrogel. KGN can be released continuously for more than 40 days and promote chondrogenic differentiation of human ADSCs in vitro (including upregulation of COL2A, SOX9, and ACAN chondrogenic genes).

2.10.7 Gene therapy

It refers to delivering nucleic acids to tissues of interest by direct (in vivo) or transduced cell-mediated (in vitro) methods using viral and non-viral vectors. In the past few decades, the strategy of expressing therapeutic transgenes at injured sites has been adopted to promote cartilage repair (Grol and Lee, 2018). However, the problems associated with non-standard procedures remain unresolved. In addition, the association of gene therapy with tissue engineering may be a promising strategy for treating cartilage and osteochondral damage (Bellavia et al., 2018). Several clinical trials of gene therapy have been conducted in patients with end-stage knee OA by intraarticular injection of human adolescent chondrocytes overexpressing cDNA encoding TGF-β1 with retroviral vectors. In the latest placebo-controlled randomized trial, clinical scores improved in the gene therapy group compared with placebo (Madry and Cucchiarini, 2016). Zhu et al. (2022b) used an injectable hydrogel to deliver miR-29b-5p (aging-associated miRNA), which was functionalized by binding to stem cell homing peptide SKPPGTSS for SMSCs recruitment contemporaneously. Sustained miR-29b-5p transport and recruitment of SMSCs, followed by chondrocyte differentiation, results in successful chondrocyte regeneration and cartilage repair. Yu et al. (2021b) implanted genetically modified ADSCs overexpressing TGF-β1 into injectable ECM hydrogels. In the rat OA model, intraarticular injection of hydrogels loaded with ADSCs overexpressing TGF-β1 significantly reduced joint inflammation, cartilage degeneration, and subchondral bone loss.

2.10.8 Drug

Until now, the conventional treatment for OA has been to reduce the main symptoms with oral or topical injections of various drugs, including NSAIDs, analgesics, and corticosteroids. The efficacy of local injection is hampered by their rapid diffusion, instability, and low retention at the target site (Mok et al., 2020). More importantly, frequent oral use of these drugs can cause serious side effects, such as increased throw of cardiovascular disease and stimulus of the gastrointestinal tract (García-Couce et al., 2022). Suitable injectable hydrogel delivery systems could sustainably release therapeutic drug concentrations in cartilage (Cao et al., 2021a; Cao et al., 2021b; Shi et al., 2021b; Khan et al., 2022). Hanafy and El-Ganainy, 2020 prepared an injectable hydrogel based on Poloxamer 407 and HA loaded with the anti-inflammatory drug DK. 40% of DK was released after 4 days. Injectable hydrogels maintain DK content and drug release percentage after 3 months of storage. Loaded DK injectable hydrogel had the greatest anti-edematous and anti-nociceptive effect compared to oral and direct injection DK. Both histomorphology and radiology showed regeneration of cartilage defects. Branco et al. (2022) prepared an injectable PVA-based hydrogel that continuously released diclofenac for cartilage regeneration.

Some of the following drugs are also used in injectable hydrogels to repair cartilage damage. Dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid, has 20–30 times the anti-inflammatory potency of natural hydrocortisone. It can reduce the loss of collagen and proteoglycan in ECM, maintain ECM synthesis, and maintain the viability of chondrocytes. In addition, it is a key reagent for inducing chondrogenesis of MSCs in vitro (García-Fernández et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021e; García-Couce et al., 2022). GlcN is a naturally occurring amino monosaccharide, widely used to reduce joint pain and repair cartilage (Suo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021c). Quercetin and naringin are flavonoids widely found in fruits and vegetables with strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. It can inhibit ECM degradation, reduce the inflammatory response and maintain chondrocyte phenotype (Yu et al., 2020b; Li et al., 2021d). Icariin can improve cartilage ECM synthesis and restrain ECM degradation, up-regulate chondrogenic specific gene expression of chondrocytes, and induce oriented chondrogenesis of BMSCs without hypertrophic differentiation (Zhu et al., 2022a).

3 Advanced injectable hydrogels for cartilage repair tissue engineering

In recent years, various injectable hydrogels with good plasticity and biological properties have been widely studied for cartilage repair tissue engineering (Table 1). Many studies have investigated the regeneration potential of injectable hydrogel cartilage in vitro and in vivo. Fattahpour et al. (2020) developed and characterized MC-CMC-Pluronic and ZnCl2 injectable hydrogels containing meloxicam. The release time of meloxicam in hydrogels containing nanoparticles was significantly longer than in hydrogels without nanoparticles. This injectable hydrogel showed good chondrocyte adhesion and proliferation. Qi et al. (2018) prepared a photo-crosslinked injectable SerMA hydrogel loaded with chondrocytes. After 8 weeks of implantation, SerMA hydrogel loaded with chondrocytes successfully formed regenerative cartilage in rabbits. Most importantly, regenerated cartilage is structurally similar to natural cartilage (Qi et al., 2018, Qi et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Application of some advanced injectable hydrogels in cartilage tissue engineering.

| Model | Formation | Technique | Structure | Major materials | Cell | Stimulating factor | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minipig | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | Nanocomposite hydrogel | HA/ PLGA | — | KGN | Cao et al. (2021a) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Dual networks | Alginate/ Bioglass | — | Quercetin | Wen et al. (2021) |

| Rabbit | Chemical crosslinking | Schiff base chemistry/Photopolymerization | Dual networks | Alginate/Amino gelatin< | — | TGF-β3/KGN | Deng et al. (2014) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | Dual networks | Col I/ tyramine hyaluronic acid | BMSCs | TGF-β1 | Tang et al. (2021) |

| In vitro | Physical crosslinking | — | — | Amnion membrane | ADSCs (rat) | — | Kim et al. (2017) |

| In vitro | Physical crosslinking | Ionic interaction | Nanocomposite hydrogel | Carboxymethyl chitosan/ methylcellulose/ Pluronic F127/ ZnCl2 | Chondrocytes (sheep) | Meloxicam | Jiang et al. (2021) |

| Mice | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | Dual networks | HA/ gelatin/ EGCG | — | — | Liu and Lin, (2019) |

| Rabbit | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Microspheres hydrogel | Pluronic F127/ PLGA | BMSCs | BMP-2 | Yan et al. (2020) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | particle scaffolding hydrogel | PEG-MAL/ PEG thiol/ arginine-glycine-aspartic acid cell adhesive peptide/ CS | — | — | Fu et al. (2018) |

| Rabbit | Chemical crosslinking | Schiff base chemistry | Semi-IPN | Gelatin/ HA/ Dex-ox | — | Naproxen/ Dexamethasone | Wang et al. (2020b) |

| Canine | — | — | — | Silanised hydroxypropymethyl cellulose/ silanised chitosan | ADSCs | - | Johnstone et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | Dual networks | Collagen/ gelatin/ hydroxy-phenyl-propionic acid | Chondrocytes (bovine) | - | Monsef and Salavati-Niasari, (2021) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Click chemistry | Nanocomposite hydrogel | PEGDGE/ PAMAM/ silica nanoparticles/ silver nanoparticles | — | Isoniazid/ rifampicin | De France et al. (2016) |

| Human ex vivo / rabbit | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | Traditional | GelMA/ FITC fluorophore | ADSCs/ BMSCs | - | García-Couce et al. (2022) |

| Rat | Physical/chemical crosslinking | Thermosensitive/photopolymerization | Traditional | Hydroxypropyl chitin/ methacrylate | BMSCs | TGF-β1 | Chen et al. (2018) |

| In vitro | Physical/chemical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Microspheres hydrogel | methoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (alanine)/ PLGA | Chondrocytes (rat) | TGF-β3 | Han et al. (2021) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Ionic interaction | Microspheres hydrogel | sodium alginate / bioglass/ δ-Gluconolactone | — | Strontium | Lee and Mooney, (2012) |

| Goat | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | Dual networks | Silk fibroin/ CMC/ gelatin | ADSCs | — | Cai et al. (2019) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Nanocomposite hydrogel | PLEL/ EPL | — | Platelet lysate | Castro-Viñuelas et al. (2018) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Disulfide crosslinking | Dual networks | Thiolated chitosan/ carboxy-methyl cellulose | — | TGF-β1 | Echave et al. (2019) |

| Rat | — | — | Microspheres hydrogel | PLGA/ chitosan/ gelatin | — | Platelet lysate | Gomez-Florit et al. (2020) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | Traditional | Sericin/ methacrylogy groups | Chondrocytes | — | Yuan et al. (2021b) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | IPN | Alginate/ cartilage silk fibroin extracellular matrix/ | Chondrocytes (human) | — | Song et al. (2015) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | Microspheres hydrogel | GelMA | — | Diclofenac sodium | Zinatloo-Ajabshir et al. (2018) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | IPN | GelMA | — | — | Nicol, (2021) |

| Rabbit | - | - | - | DNA | BMSCs | — | Graça et al. (2020) |

| Rabbit | Chemical crosslinking | Schiff base chemistry | Dual networks | Chitosan/ HA | ADSCs | Chondrocyte EVs | Mok et al. (2020) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Silanization | IPN | Chitosan/ HA/ silanized-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | Chondrocytes | - | Li et al. (2021c) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Enzyme-mediated crosslinking | Double networks | Alginate/ dopamine/ CS/ silk fibroin | — | BMSCs EVs | Zhu et al. (2022b) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Chemical crosslinking | Microspheres hydrogel | PLGA/ carboxymethyl chitosan-oxidized chondroitin sulfate | BMSCs (rabbit) | KGN | Eyre, (2004) |

| In vitro | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Microspheres hydrogel | Chitosan/ human acellular cartilage ECM | BMSCs (human) | - | Mehrali et al. (2017) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Dual networks | PDLLA-PEG-PDLLA | - | SMSCs EVs/ circRNA3503 | Yu et al. (2021b) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Click chemistry | Dual networks | PEG/ CS | ADSCs (rat) | — | Zhang et al. (2021b) |

| Rabbit | Physical crosslinking | Guest-host complexation | Microspheres hydrogel | HA–cyclodextrin/ polyacrylic acid–ferrocene/ PLGA | Chondrocytes | GSH/ iron oxide nanoparticles | Qi et al. (2018) |

| Pig explants | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Dual networks | PLL/ poly (N-isopropylacrylamide | Chondrocytes/ MSCs (rabbit) | — | Saravanan et al. (2019) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Dual networks | Sodium alginate/ bioglass | — | Naringin | Wei et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Physical/chemical crosslinking | Ionic interaction | IPN | GelMA/ HA | — | — | Rinoldi et al. (2021) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Nanoparticle hydrogel | Poly organosphosphazenes | — | TCA | Lokhande et al. (2018) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | pH-responsive | IPN | Thiolated HA/ Col I | Gene-engineered ADSCs overexpressing TGF-β1 | — | Fan et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Traditional | Chitosan/ N-(β- maleimidopropyloxy) succinimide ester/ β-glycerophosphate | ADSCs (human) | KGN | Deng et al. (2020) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | Dynamic chemical bonds | Dual networks | Glycol chitosan/ GCS/DF-PEG | ADSCs | — | Kahn et al. (2017) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Ionic interaction | Microspheres hydrogel | Decellularized bovine articular Cartilage/ alginate | BMSCs (human) | — | Werkmeister et al. (2010) |

| Rat | Chemical crosslinking | — | — | SAP | — | miR-29b-5p | Xu et al. (2017b) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | IPN | HA/ Poloxamer 407 | BMSCs | Icariin | Cai et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Chemical crosslinking | Photopolymerization | Double networks | GelMA/ HA/ hyaluronic acid methacrylate | Chondrocytes (rabbit) | — | Meng et al. (2019) |

| Rat | Physical crosslinking | Thermosensitive | Nanoparticle hydrogel | Chitosan/ silk fibroin/ glycerophosphate | BMSCs | TGF-β1 | Luu et al. (2022) |

Numerous studies have investigated injectable hydrogel strategies that guide stem cell phenotypic expression and manipulate cartilage matrix properties. Liu et al. (2021b) revealed that hydrogel scaffolds with gradient distribution could better simulate the function of natural cartilage and promote stem cell differentiation than homogeneous hydrogel scaffolds. In rabbit models, injectable hydrogels containing BMSCs that sustained-release BMP-2 were more effective than microfractures alone in treating cartilage damage (Vayas et al., 2021). Zhang and his team prepared injectable hydrogels composed of hyaluronic acid-tyramine and collagen type I-tyramine-loaded BMSCs and TGF-β1 (Zhang et al., 2020d). The injectable hydrogel supports the differentiation of BMSCs into chondrocytes. In vivo experiments further demonstrated that this injectable hydrogel can achieve good repair of transparent articular cartilage. Mahajan et al. (2022) developed a silk fibroin/CMC/gelatin complex hydrogel that increases contraction and hardness over time. The contractile-mediated mechanical stimulation promotes the formation of ADSCs cartilage. The regenerated cartilage of goats is very similar to natural cartilage. The cells may have a therapeutic effect because EVs derived from them can induce stem cell differentiation and chondrocyte proliferation (Liu et al., 2017b; Saveh-Shemshaki et al., 2019; Song et al., 2021). Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2021d) prepared the load with BMSCs-EVs alginate/dopamine/CS/silk fibroin composite injectable hydrogel.

When the hydrogel was injected into a rat cartilage defect model, EVs released by injectable hydrogel could recruit BMSCs into the hydrogel through a chemokine signaling pathway and promote BMSCs proliferation and differentiation to promote cartilage repair. Tao et al. (2021) implanted circRNA3503 carried by SMSCS-EVS into PDLLA-PEG-PDLLA injectable hydrogel. EVs promoted chondrocyte migration and proliferation, while circRNA3503 reduced chondrocyte apoptosis and ECM degradation, and both of them combined with regenerating damaged cartilage in rats. Heirani-Tabasi et al. (2021) demonstrated that human articular chondrocytes EVs in chitosan-HA injectable hydrogels have chondrogenic differentiation effects on ADSCs. In the rabbit cartilage defect model, EVS-treated ADSCs had greater cartilage regeneration ability than untreated MSCs or ADSCs treated with EVS without gel.

In addition, injectable hydrogels have been studied to detect cartilage repair ability dynamically. According to Onofrillo et al. (Onofrillo et al., 2021), FLIH was considered a sensitive tool for monitoring the photo-crosslinked injectable hydrogels in cartilage tissue engineering structure. The generation of cartilage ECM in injectable hydrogels is related to the fluorescence loss curve, which describes the hydrogels’ degradation rate. Using FLIH can be achieved through an extensible system for sample maintenance and fluorescence recording, resulting in an analytical real-time monitoring system suitable for non-contact high-throughput evaluation of chondrogenesis.

4 Summary and perspectives

The repair of cartilage defects still faces many challenges. Injectable hydrogel is the main development direction of cartilage tissue engineering, not only because of its bionic properties similar to cartilage ECM due to its high moisture content but also because of its minimally invasive properties and strong plasticity ability to match irregular defects. First, to improve the biomechanical properties of injectable hydrogels, traditional single-network hydrogels are added with different polymer mixtures or networks, and many nano/micron-composite materials are used to alter the mechanical properties and sustained-release properties of the matrix. Integrating cells and cytokines or other stimulators into injectable hydrogels can improve the integration of hydrogels with surrounding cartilage and promote cartilage regeneration. Controlling the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells into chondrocytes is of great interest.

Despite many relatively successful preclinical studies and several advanced manufacturing methods for engineered tissues, there remain limitations that must be addressed in preparing injectable hydrogels with excellent performance for optimal regeneration of cartilage defects. First, the injectable hydrogel matrix must be able to fill the defect area with a smooth surface similar to natural cartilage without fusing with the surrounding healthy tissue. Second, rapid degradation of the hydrogel matrix before replacement by regenerative ECM may compromise its mechanical stability and therapeutic efficacy. To address this issue, appropriate exogenous cells (such as MSCs) can be added to the hydrogel matrix, or peripheral cartilage cells can be recruited to the defect area, where they generate new cartilage tissue to replace the degraded hydrogel smatrix. Therefore, the signaling pathway from stem cells to specific chondrocytes and the specific stimulation mechanism in hydrogel must be further understood. Finally, injectable hydrogels need to be further studied at the clinical level, from experimental animals to human experiments, and thoroughly evaluated factors such as biocompatibility, degradability, and comfort of hydrogel materials.

Author contributions

SZ, YL, and ZH contributed to conception and design of the study. LJ organized the database. WZ performed the statistical analysis. YT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JL, DY, QZ, and QB wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by Professor QB. National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81672769); QZ. Prof. Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (Grant 2021KY028) and Basic Public Welfare Research Program of Zhejiang Province (Grant LGF22H060029) and DY. Prof. Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (Grant 2020KY018).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- ACI

Autologous chondrocyte implantation

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- CST

Critical solution temperature

- NIPAAm

N-isopropyl acrylamide

- IPN

Interpenetrating Polymer Network

- IUPAC