Abstract

Spores of Bacillus subtilis are significantly more resistant to wet heat than are their vegetative cell counterparts. Analysis of the effects of mutations in and the expression of fusions of a coding gene for a thermostable β-galactosidase to a number of heat shock genes has shown that heat shock proteins play no significant role in the wet heat resistance of B. subtilis spores.

The gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis undergoes the process of sporulation when nutrients become exhausted, and the resulting spores are more resistant than are the growing cells to a variety of environmental insults including heat, UV and gamma radiation, and a number of toxic chemicals (8, 34). Wet heat resistance is probably the most dramatic resistance property of dormant spores, as spores are resistant to about 40°C-higher temperatures than are vegetative cells (8). Spore wet heat resistance is due to a number of factors including dehydration of the spore protoplast or core (8), mineralization of the spore core (8), saturation of spore DNA with α/β-type small acid-soluble proteins (33, 34), and thermal adaptation, as spores of a single species formed at higher temperatures are more wet heat resistant than are spores formed at lower temperatures (8, 39).

Although many factors contribute to spore wet heat resistance, the identity of the target for wet heat killing of spores is not known. However, two different types of studies have indicated that spore DNA is not the killing target and suggested that some spore protein might be the target (2, 7, 30). If spore killing by wet heat is indeed through protein damage, then it is possible that repair or removal of a damaged protein might be important in spore wet heat resistance. Proteins that can repair or remove denatured proteins in vivo are often members of the heat shock regulon, which is important in the survival of many different bacteria after a heat shock (9, 17). Since sporulation at elevated temperatures results in spores with increased heat resistance and heat shock protein synthesis is increased at elevated temperatures (12, 38), then spores prepared at higher temperatures may also have increased levels of heat shock proteins which may in turn contribute to their increased heat resistance. In order to investigate whether proteins of the heat shock regulon play any role in wet heat resistance of B. subtilis spores, we have examined (i) the effect of mutations in known heat shock genes on spore wet heat resistance, (ii) the effect of mild heat shock at various times during sporulation on spore wet heat resistance, and (iii) the expression of heat shock genes during germination of spore populations which had been killed ∼50% by wet heat treatment.

Effects of mutations in heat shock genes on spore wet heat resistance.

The heat shock genes of B. subtilis are grouped into at least three classes based on the precise mechanism for the regulation of their expression (11); we examined the effects of mutations in representatives from each of the three classes. Mutations in class I genes included a polar mutation in dnaK, a polar mutation in hrcA, and a nonpolar mutation in hrcA. The mutated class II gene was sigB (14) encoding the RNA polymerase sigma factor, ςB, which directs transcription of other class II genes; consequently, a mutation in sigB abolishes transcription of all class II genes (1, 3, 4, 38). Mutations in class III genes included a mutation in lonA (24, 26) and a nonpolar mutation in ctsR (6); ctsR is a negative regulator of the clpP, clpC, and clpE operons (5, 6, 15), so a mutation in ctsR results in the overexpression of those operons. We had hoped to also study strains with a mutation in clpC, but such strains sporulated extremely poorly, as noted previously (22).

All of the mutations noted above were introduced into our wild-type B. subtilis (PS832) background and into the isogenic strain (termed α−β−) lacking the genes, sspA and sspB, that encode the two major α/β-type small acid-soluble proteins (PS356) (19) (Tables 1 and 2). The ctsR mutant strain was constructed by congression of plasmid pHTΔctsR along with the cat marker in chromosomal DNA of strain QB4903, since pHTΔctsR does not carry an antibiotic resistance marker (6). Because a number of the mutations that we wished to analyze were available, we had only to construct the polar mutation in dnaK and the polar and nonpolar mutations in hrcA. For construction of the dnaK mutation, a DNA fragment containing the 5′ end of the dnaK gene (−186 to +74 relative to the dnaK translation start site [+1]) was PCR amplified from strain PS832 chromosomal DNA with primers ΔdnaK1w and ΔdnaK1x, and the PCR product was cut with HindIII (site within ΔdnaK1w) and EcoRI (site within ΔdnaK1x) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pJL74 (16) to generate plasmid pdnaK1. The 3′ end of the dnaK gene (+1740 to +2037 relative to the dnaK translation start site [+1]) was amplified similarly with primers ΔdnaK2y and ΔdnaK2z, and the PCR product was cut with BamHI (site within ΔdnaK2y) and EagI (site within ΔdnaK2z) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pdnaK1 to generate plasmid pdnaK1/2. In this plasmid, the two cloned PCR products flank a spectinomycin resistance (Spr) marker. For construction of the polar hrcA mutation, a DNA fragment containing the 5′ end of the hrcA gene (−208 to +236 relative to the hrcA translational start site [+1]) was PCR amplified from strain PS832 chromosomal DNA with primers ΔhrcA1w and ΔhrcA1x, and the PCR product was cut with HindIII (site within ΔhrcA1w) and EcoRI (site within ΔhrcA1x) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pJL74 (16) to generate plasmid phrcA1. The 3′ end of the hrcA gene (+988 to +1184 relative to the hrcA translational start site [+1]) was amplified in the same manner with primers ΔhrcA2y and ΔhrcA2z, cut with BamHI (site within ΔhrcA2y) and EagI (site within ΔhrcA2z), and cloned between the same sites in plasmid phrcA1 to generate phrcA1/2, in which the two cloned PCR products flank a Spr marker. In order to construct a nonpolar mutation in hrcA, this gene's promoter and translation start site plus an in-frame stop codon were placed immediately before the downstream grpE gene which is cotranscribed with hrcA, resulting in production of a truncated HrcA protein (16 amino acids as opposed to 343 amino acids in the wild-type protein) while still allowing translational coupling of hrcA to the remainder of the operon. A DNA fragment containing 500 bp from hemN, the gene upstream of hrcA (+592 to +1092 relative to the hemN translational start site [+1]) was PCR amplified from strain PS832 chromosomal DNA with primers Δhem/A and Δhem/B, and the PCR product was cut with HindIII (site within Δhem/A) and EcoRI (site within Δhem/B) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pJL74 (16) to generate plasmid pJLhem. A DNA fragment containing the promoter region and a small fragment of the 5′ end of hrcA (−190 to +33 relative to the hrcA translational start site [+1]) was amplified similarly with primers ΔphrcAlong and ΔphrcBlong, and the PCR fragment was cut with BamHI (site within ΔphrcAlong) and EagI (site within ΔphrcBlong) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pJLhem to generate plasmid pJLhemhrc. Finally, a DNA fragment containing the translational start site of the grpE gene immediately downstream of hrcA (−76 to +506 relative to the grpE translational start site [+1]) was amplified with primers Δpgrp/A and Δpgrp/B, and the PCR fragment was cut with EagI (site within Δpgrp/A) and SstI (site within Δpgrp/B) and cloned between the same sites in plasmid pJLhemhrc to generate plasmid phrcA-np, in which the hemN and hrcA fragments flank a Spr marker and the grpE fragment is cloned downstream of the truncated hrcA gene. The sequences of the primers used in these PCRs are available upon request. After confirmation of the expected DNA sequence in these plasmids, they were used to transform B. subtilis strains PS832 and PS356 to Spr (100 μg/ml). Southern blot analysis of appropriately digested chromosomal DNA from Spr transformants confirmed that the clones used for further analysis had the indicated deletions (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used

| Plasmid | Description (antibiotic resistance) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pPctc-bgaB | Derivative of pMLK83 carrying a ctc-bgaB fusion (Kmr) | W. Schumann |

| pPclpC-bgaB | Derivative of pMLK83 carrying a clpC-bgaB fusion (Kmr) | W. Schumann |

| pPlon-bgaB | Derivative of pMLK83 carrying a lonA-bgaB fusion (Kmr) | W. Schumann |

| pPdnaK-bgaB | Derivative of pMLK83 carrying a dnaK-bgaB fusion (Kmr) | 20 |

| pDL2/pgroE-bgaB | Derivative of pDL carrying a groEL-bgaB fusion (Cmr) | 40 |

| pHTΔctsR | Derivative of pHT315 used in introducing ΔctsR (Cmr) | 6 |

| pJL74 | Shuttle plasmid replicating in both E. coli and B. subtilis (Apr Spr) | 16 |

| pdnaK1/2 | Derivative of pJL74 used to generate ΔdnaK strains (Spr) | This work |

| phrcA1/2 | Derivative of pJL74 used to generate the polar ΔhrcA mutation (Spr) | This work |

| phrcA-np | Derivative of pJL74 used to generate the nonpolar ΔhrcA mutation (Spr) | This work |

TABLE 2.

B. subtilis strains used

| Strain | Genotype and phenotype | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| ML6 | sigB::cat Cmr | 14 |

| PS356 | ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− | 19 |

| PS832 | Wild-type, trp+ revertant of strain 168 | Laboratory stock |

| PS2538 | sigB::cat Cmr | ML6→PS832 |

| PS2539 | sigB::cat ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Cmr | ML6→PS356 |

| PS2542 | Δlon::cat Cmr | RS359→PS832 |

| PS2543 | Δlon::cat ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Cmr | RS359→PS356 |

| PS2567 | amyE::groEL-bgaB Cmr | WBG2→PS832 |

| PS2643 | amyE::ctc-bgaB Kmr | pPctc-bgaB→PS832 |

| PS2645 | amyE::dnaK-bgaB Kmr | pPdnaK-bgaB→PS832 |

| PS2647 | amyE::clpC-bgaB Kmr | pPclpC-bgaB→PS832 |

| PS2549 | amyE::lon-bgaB Kmr | pPlon-bgaB→PS832 |

| PS3044 | ΔdnaK::spc Spr | pdnaK1/2→PS832 |

| PS3045 | ΔdnaK::spc ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Spr | pdnaK1/2→PS356 |

| PS3046 | ΔhrcA::spc Spr | phrcA1/2→PS832 |

| PS3047 | ΔhrcA::spc ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Spr | phrcA1/2→PS356 |

| PS3085 | amyE::clpP′-bgaB cat ΔctsR Cmr | QB4903 + pHTΔctsR→PS832 |

| PS3086 | amyE::clpP′-bgaB cat ΔctsR ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Cmr | QB4903 + pHTΔctsR→PS356 |

| PS3302 | ΔhrcA::spc Spr | phrcA-np→PS832 |

| PS3303 | ΔhrcA::spc ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Spr | phrcA-np→PS356 |

| QB4903 | amyE::clpP′-bgaB cat trpC2 Cmr | 6 |

| RS359 | Δlon::cat Cmr | 26 |

| WBG2 | amyE::groEL-bgaB Cmr | 40 |

DNA(s) from the plasmid or strain left of the arrow was used to transform the bacterial strain to the right of the arrow.

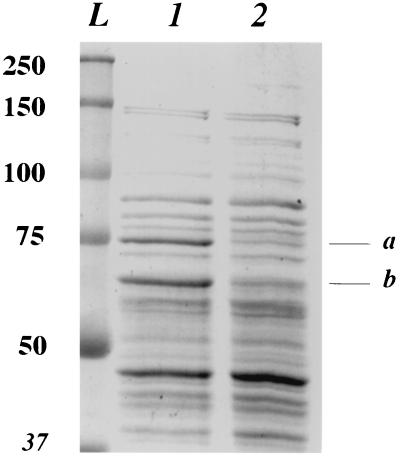

Since the hrcA gene is a negative regulator of class I gene expression including that of dnaK and the groESL operons, a nonpolar mutation in hrcA should result in the overexpression of all of these genes, while a polar mutation in hrcA should result in the overexpression of just the groESL operon, since hrcA is the first gene in the dnaK operon (27, 40). In order to demonstrate this point directly, cleaned spores (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼30) (see below) were decoated with 1 ml of 0.1 M NaOH–0.1 M NaCl–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–0.1 M dithiothreitol for 2 h at 37°C; washed 10 times by centrifugation with 1 ml of H2O; and suspended in 500 μl of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–5 mM EDTA–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride–40 μg of lysozyme. After incubation for 5 min at 37°C and 30 min at 4°C, the extract was centrifuged, an aliquot of the supernatant fluid was run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, either the gel was stained with Coomassie blue or the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose-based paper, and DnaK and GroEL were detected using anti-Escherichia coli GroEL (Sigma) or anti-Chlamydia trachomatis DnaK (a gift of Svend Birkelund) antisera (10). These analyses showed that the hrcA polar and nonpolar mutations did indeed result in overexpression of GroEL or DnaK and GroEL, respectively, in both vegetative cells and spores (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Presumably, the nonpolar hrcA mutation also caused overexpression of GroES, but we have not yet shown this directly.

FIG. 1.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of extracts from wild-type (PS832) and nonpolar hrcA mutant (PS3032) B. subtilis spores. Spores were decoated, washed, and lysed as described in the text; 25 μg of protein was run on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel; and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane L contains molecular mass markers whose kilodaltons are given on the left side of the gel, lane 1 is the hrcA spore extract, and lane 2 is wild-type spore extract. The bands labeled a and b are DnaK and GroEL, respectively.

Spores of all strains were prepared at 37°C in 2× SG medium (23) without antibiotics, cleaned as described previously (23), and stored in water at 10°C; all spores whose resistance was to be compared were prepared, cleaned, and tested together. All spore preparations used were free (>98%) of vegetative or sporulating cells, germinated spores, and cell debris. In order to determine the spore titer, an aliquot (100 μl) of spores at an OD600 of 1 was diluted in distilled water and multiple samples of several dilutions were plated on Luria-Bertani medium plates (18, 25) containing kanamycin (10 μg/ml), spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) as needed. The remaining spores at an OD600 of 1 were incubated at 90°C (wild-type strains) or 85°C (α−β− strains) for various times, and aliquots were removed, diluted, and plated as described above. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h prior to enumeration. All experiments were performed on at least two independent spore preparations, and all spore preparations were tested at least twice.

With one exception (see below), the wet heat resistance of spores from strains with mutations in heat shock genes was essentially identical to that of the parental spores (Table 3). Although there was slight variability in spore heat resistance between different experiments and spore preparations, when spores were tested and prepared together, the relative heat resistance of wild-type and mutant spores was essentially identical. The only mutant spores which differed significantly in heat resistance from that of wild-type spores were sigB spores, which had a small but reproducibly lower wet heat resistance compared with that wild-type spores. This effect of the sigB mutation was even more dramatic in the α−β− genetic background (Table 3). Density gradient centrifugation of decoated spores as described previously (37) showed that there were no differences in core water content between the sigB and parental spores with either wild-type or α−β− backgrounds (data not shown). In addition, we found that both wild-type and α−β− spores exhibited the same mutation frequency,∼4.5% auxotrophic or asporogenous colonies among survivors of wet heat treatments giving 90% killing (7). We also measured the dry heat resistance of dnaK, sigB, ctsR, and PS832 spores at 120°C as described previously (32) and again found no differences (data not shown). It is important to note again that the nonpolar hrcA mutant overexpresses DnaK and GroEL in spores (Fig. 1), and presumably also GroES. However, these spores had the same wet heat resistance as did the wild-type spores (Table 3), indicating that overexpression of class I heat shock proteins does not affect spore heat resistance.

TABLE 3.

Wet heat resistance of spores of various strainsa

| Expt no.b | Heat shock gene mutated | Wild-type background, D90-minc (strain) | α−β− background, D85-minc (strain) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 14 (PS832) | 9 (PS356) |

| 1 | dnaK | 14 (PS3044) | 8 (PS3045) |

| 2 | None | 14 (PS832) | 12 (PS356) |

| 2 | hrcA (polar) | 14 (PS3046) | 10 (PS3047) |

| 3 | None | 13 (PS832) | 13 (PS356) |

| 3 | hrcA (nonpolar) | 12 (PS3302) | 15 (PS3303) |

| 4 | None | 8 (PS832) | 6 (PS356) |

| 4 | lon | 7 (PS2542) | 6 (PS2543) |

| 5 | None | 7 (PS832) | 14 (PS356) |

| 5 | sigB | 5 (PS2538) | 4 (PS2539) |

| 6 | None | 12 (PS832) | 15 (PS356) |

| 6 | ctsR | 11 (PS3085) | 13 (PS3086) |

Spores were prepared and cleaned and wet heat resistance was measured as described in the text.

Spores used in individual experiments were from separate preparations, but within an experiment, spores from different strains were prepared and tested together.

Time in minutes to kill 90% of spores at either 90 or 85°C.

Effect of heat shock during sporulation on spore wet heat resistance.

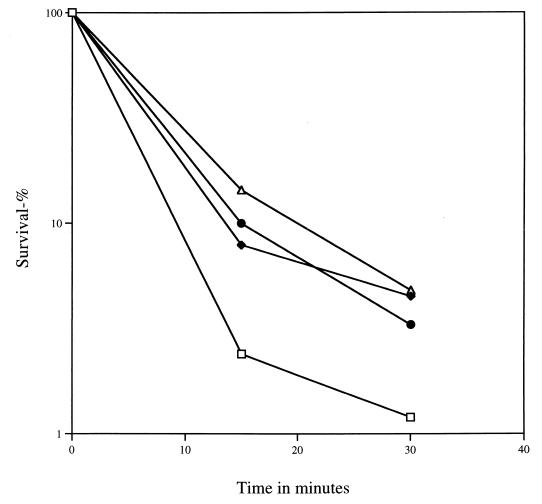

As noted above, it is known that, when cultures of the same strain are sporulated at different temperatures, the spores from cultures sporulated at the higher temperature are more wet heat resistant than are those sporulated at lower temperatures (8, 39). It has also been reported previously that when Bacillus megaterium or B. subtilis cultures at 27 or 30°C were shifted to 45 or 48°C for 30 min at 1 to 2 h into sporulation, the resultant spores were more heat resistant than were those from cultures which had not been subjected to a temperature shift or had been shifted earlier or later in sporulation (21, 28), and we obtained similar results. Cultures were sporulated at 30°C by the resuspension method (36) to ensure the maximum synchrony of the sporulation process, shifted to 45°C for 30 min at various times during sporulation, and returned to 30°C for the remainder of sporulation, and the heat resistance of the resulting spores was measured (Fig. 2). The same experiment was also performed during sporulation in 2× SG medium (23) (data not shown). In both cases, spores from cultures that were shifted to 45°C at various times in sporulation were more heat resistant than were those from cultures not shifted at all, with cultures shifted 2 h into sporulation consistently giving spores with slightly more heat resistance (Fig. 2 and data not shown). We also used Western blot analysis to examine the level of DnaK and GroEL in spores from cultures sporulated at 30°C in 2× SG medium and either shifted to 45°C for 30 min or not shifted. Cleaned spores (OD600 of ∼75) were lyophilized and dry ruptured for 8 min with glass beads as the abrasive, and the dry powder was suspended in 500 μl of cold 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM EDTA–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After incubation for 30 min at 4°C, the extract was centrifuged, an aliquot of the supernatant fluid was run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose-based paper, and DnaK and GroEL were detected as described above. There was no (<15%) difference in the levels of either GroEL or DnaK in the more heat-resistant spores from the appropriately heat-shocked culture compared to the spores from the non-heat-shocked culture (data not shown). These results agree with those of a recent study using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (21) which found a transient, but no permanent, increase in the levels of a number of heat shock proteins in cells from sporulating cultures that had been heat shocked. These latter results thus strongly suggest that increased spore levels of heat shock proteins are not responsible for the increased heat resistance of spores from appropriately heat-shocked cultures. To prove this point conclusively, we performed the same temperature shift during sporulation of sigB and dnaK strains. Again, spores from cultures of these mutant strains that were shifted to 45°C at ∼2 h into sporulation exhibited increased wet heat resistance compared to that of spores from unshifted cultures (data not shown), strongly indicating that heat shock proteins are not involved in the elevated wet heat resistance of spores from cultures subjected to a heat shock. We also analyzed the core wet density (37) of spores from cultures which had or had not been subjected to a 30-min shift from 30 to 45°C at the second hour of sporulation. Since these values were both 1.355 ± 0.01 g/ml, there was no difference in the core wet density and thus the core water content of these spores, indicating that this is not the cause of the increased heat resistance of spores from appropriately heat-shocked sporulating cultures (8).

FIG. 2.

Heat resistance of spores from wild-type B. subtilis cultures shifted from 30 to 45°C for 30 min during sporulation. Sporulation of strain PS832 was in resuspension medium with the time of initiation of sporulation defined as the time of resuspension. Spores were cleaned and wet heat resistance at 90°C was measured as described in the text. Similar results were obtained in experiments performed twice, as well as during sporulation in nutrient exhaustion (2× SG) medium. The symbols used are as follows: □, unshifted culture; ⧫, culture shifted at the initiation of sporulation; ▵, culture shifted at the second hour of sporulation; ●, culture shifted at the fourth hour of sporulation. Error bars have been omitted for clarity, but the spores produced in the culture that was shifted at the second hour of sporulation had D90 values (see Table 3) that were from 28 to 110% (±10%) greater in multiple experiments than values for spores from unshifted cultures or from cultures shifted earlier or later in sporulation.

Expression of heat shock genes during germination of heat-treated spores.

The results given above strongly suggest that heat shock proteins play no significant role in spore wet heat resistance and suggest that repair or removal of heat-damaged proteins during spore germination and outgrowth is not important to spore survival after heat treatment. Heat shock of growing cells is known to induce the synthesis of a number of heat shock proteins in a variety of species (17). If removal or renaturation of damaged proteins is not important in spore heat resistance, then wet heat treatment of dormant spores would not result in the production of heat shock proteins during subsequent spore germination. In order to test this prediction, we examined the expression of a number of heat shock genes during germination of wet heat-treated spores. The genes examined were groEL, dnaK, ctc, lonA, and clpC, and their expression was monitored by measuring β-galactosidase synthesis from transcriptional fusions in which the promoter of the gene in question was fused to the promotorless bgaB gene encoding the thermostable β-galactosidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus; these bgaB fusions were inserted into the amyE locus on the B. subtilis chromosome (20). If any of these gene products are important in repairing or removing a heat-damaged protein, we would expect to see an increase in β-galactosidase synthesis from the bgaB fusion during germination of heat-treated spores compared to synthesis in germinating unheated spores (31). Cleaned spores carrying the various bgaB fusions were prepared at 37°C in 2× SG medium (23) and treated with wet heat to give ∼50% killing. Both heated and unheated spores (OD600 of 20) were germinated at 37°C in 25 ml of Spizizen's minimal medium (35) plus 0.1% Casamino Acids and also containing 5 μCi of [3H]leucine in order to measure total protein synthesis (31). Samples were taken throughout germination and outgrowth (∼3 h), β-galactosidase activity and total protein synthesis were determined, and the β-galactosidase specific activity was calculated relative to total protein synthesized (31), since there is essentially no β-galactosidase from any of these bgaB fusions in spores (data not shown). The β-galactosidase specific activity would be higher in the culture from heated spores if expression of the heat shock gene in question had been induced during germination and outgrowth by prior spore heat treatment (31). However, upon analysis of the expression of all five heat shock genes, we found less than a 25% difference in the β-galactosidase specific activities in germinating-outgrowing cultures from heated versus unheated spores (data not shown). In contrast, in vegetatively growing cells, heat shock results in a 4- to 25-fold induction of expression of these same genes (11, 24, 38). From these data, we conclude that the heat shock genes that we tested are not induced by prior heat treatment of spores.

Conclusions.

The findings in this work allow three major conclusions. First, as reported by two other groups (13, 21, 28), a heat shock at an early time in sporulation results in an increase in wet heat resistance of the resultant spores. This effect does not appear to involve the heat shock response, as there was no elevation in the level of heat shock proteins in the spores with elevated wet heat resistance, as also found in a recent study (21), and we also found that mutations in several heat shock genes did not abolish this phenomenon. While the specific reason for the effect of a heat shock at the second hour of sporulation is not clear, it may be simply the result of a minor, albeit global, alteration in transcription at a key time in sporulation which results in production of spores with slightly altered properties, including slightly increased wet heat resistance. Indeed, recent work has indicated that global alterations in transcription during sporulation can significantly alter spore properties (29).

The second conclusion is that a sigB mutation has a significant effect on spore heat resistance, with this effect being greater in an α−β− background. Our studies also show that this effect is not to due to increased transcription of heat shock genes by ςB. The specific reason for this effect is not clear, although it may well result from a subtle alteration in transcription of multiple genes during sporulation.

The third conclusion from this work is that heat shock proteins appear to play no role in spore wet heat resistance. A role for the heat shock regulon in spore wet heat resistance has been suggested previously (28), but our findings clearly show that (i) mutations in heat shock genes (with the exception of sigB) do not alter spore wet heat resistance, (ii) loss-of-function mutations in heat shock genes do not eliminate the increase in wet heat resistance of spores from heat-shocked cultures, (iii) expression of heat shock genes is not induced during germination of wet heat-treated spores, and (iv) overexpression of class I heat shock genes does not result in increased spore heat resistance. We have clearly shown that class I and class II heat shock genes are not involved in spore heat resistance, since a mutation in dnaK and overexpression of class I genes do not affect spore heat resistance and neither groEL nor dnaK is transcribed during germination of heat-treated spores. In addition, mutation of sigB, the gene encoding the ς factor necessary for the transcription of all class II genes, results in only a slight reduction in spore heat resistance, which is likely due to an indirect effect on sporulation. We have not tested mutations in all possible heat shock genes, as mutations in some of these genes are lethal or abolish sporulation. Thus, it is not possible to definitively rule out all class III heat shock genes as playing a role in spore heat resistance. However, our analyses of the major players in the heat shock response in vegetative cells strongly indicate that the heat shock response as it functions in growing cells plays no role in spore wet heat resistance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM19698) and the Army Research Office.

We thank David Dubnau, Michael Hecker, Richard Losick, Tarek Msadek, Svend Birkelund, Wolfgang Schumann, and Sui-Lam Wong for their gifts of strains, plasmids, and antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann H J, Bernhardt J, Schmid R, Mach H, Volker U, Hecker M. First steps from a two-dimensional protein index towards a response-regulation map for Bacillus subtilis. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1451–1463. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belliveau B H, Beaman T C, Pankratz H S, Gerhardt P. Heat killing of bacterial spores analyzed by differential scanning calorimetry. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4463–4474. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4463-4474.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhardt J, Volker U, Volker A, Antelmann H, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Specific and general stress proteins in Bacillus subtilis—a two dimensional protein electrophoresis study. Microbiology. 1997;143:999–1017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Price C W. Transcription factor ςB of Bacillus subtilis controls a large stationary-phase regulon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3957–3963. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3957-3963.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derre I, Rapoport G, Devine K, Rose M, Msadek T. ClpE, a novel type of HSP100 ATPase, is part of the CtsR heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:581–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derre I, Rapoport G, Msadek T. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clp and molecular chaperone gene expression in gram positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;176:1359–1363. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairhead H, Setlow B, Setlow P. Prevention of DNA damage in spores and in vitro by small, acid-soluble proteins from Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1367–1374. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1367-1374.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhardt P, Marquis R E. Spore thermoresistance mechanisms. In: Smith I, Slepecky R A, Setlow P, editors. Regulation of prokaryotic development. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert H. Protein chaperones and protein folding. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1994;5:534–539. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecker M, Schumann W, Volker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecker M, Volker U. Non-specific, general and multiple stress resistance of growth-restricted Bacillus subtilis cells by the expression of the ςB regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1129–1136. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hlavacek O, Adamec J, Vomastek T, Babkova L, Sedlak M, Vohradsky J, Vachova L, Chaloupka J. Expression of dnaK and groESL operons during sporulation of Bacillus megaterium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;165:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igo M M, Lampe M, Ray C, Shafer W, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Genetic studies of a secondary RNA polymerase sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3464–3469. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3464-3469.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruger E, Hecker M. The first gene of the Bacillus subtilis clpC operon, ctsR, encodes a negative regulator of its own operon and other class III heat shock genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6681–6688. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6681-6688.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeDeaux J R, Grossman A D. Isolation and characterization of kinC, a gene that encodes a sensor kinase homologous to the sporulation sensor kinases KinA and KinB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:166–175. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.166-175.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund P A. The roles of molecular chaperones in vivo. Essays Biochem. 1995;29:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason J M, Setlow P. Essential role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to UV light. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:174–178. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.174-178.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mogk A, Hayward R, Schumann W. Integrative vectors for constructing single-copy transcriptional fusions between Bacillus subtilis promoters and various reporter genes encoding heat-stable enzymes. Gene. 1996;182:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Movahedi S, Waites W. A two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis study of the heat stress response of Bacillus subtilis during sporulation. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4758–4763. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4758-4763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanamiya H, Ohaski Y, Asai K, Moriya S, Ogasawara N, Fujita M, Sadie Y, Kawamura F. ClpC regulates the fate of a sporulation initiation sigma factor, ςH protein, in Bacillus subtilis at elevated temperatures. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:505–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riethdorf S, Volker U, Gerth U, Winkler A, Engelmann S, Hecker M. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Bacillus subtilis lon gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6518–6527. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6518-6527.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt R, Decatur A L, Rather P N, Moran C P J, Losick R. Bacillus subtilis Lon protease prevents inappropriate transcription of genes under the control of the sporulation transcription factor ςG. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6528–6537. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6528-6537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz A, Schumann W. hrcA, the first gene of the Bacillus subtilis dnaK operon, encodes a negative regulator of class I heat shock genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1088–1093. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1088-1093.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedlak M, Vinter V, Adamec J, Vohradsky J, Voburka Z, Chaloupka J. Heat shock applied early in sporulation affects heat resistance of Bacillus megaterium spores. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:8049–8052. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.8049-8052.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setlow B, McGinnis K A, Ragkousi K, Setlow P. Effects of major spore-specific DNA binding proteins on Bacillus subtilis sporulation and spore properties. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6906–6912. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6906-6912.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setlow B, Setlow P. Heat inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores lacking small, acid-soluble spore proteins is accompanied by generation of abasic sites in spore DNA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2111–2112. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2111-2113.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setlow B, Setlow P. Role of DNA repair in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3486–3495. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3486-3495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setlow B, Setlow P. Small, acid-soluble proteins bound to DNA protect Bacillus subtilis spores from killing by dry heat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2787–2790. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2787-2790.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setlow P. Small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function, and their degradation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:319–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setlow P. Mechanisms which contribute to the long-term survival of spores of Bacillus species. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:49S–60S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb04357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spizizen J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sterlini J M, Mandelstam J. Commitment to sporulation in Bacillus subtilis and its relationship to development of actinomycin resistance. Biochem J. 1969;113:29–37. doi: 10.1042/bj1130029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tisa L S, Koshikawa T, Gerhardt P. Wet and dry bacterial spore densities determined by buoyant sedimentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:1307–1310. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.6.1307-1310.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volker U, Engelmann S, Maul B, Riethdorf S, Volker A, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:741–752. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams O B, Robertson W J. Studies on heat resistance. VI. Effect of temperature of incubation at which formed on heat resistance of aerobic thermophilic spores. J Bacteriol. 1954;67:377–378. doi: 10.1128/jb.67.3.377-378.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan G, Wong S-L. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis groE regulatory mutants: evidence for orf39 in the dnaK operon as a repressor gene in regulating the expression of both groE and dnaK. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6462–6468. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6462-6468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]