Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of changes in use of care and implementation of hospital reorganisations spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic (first wave) on the acute management times of patients who had a stroke and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Design

Two cohorts of patients who had an STEMI and stroke in the Aquitaine Cardio-Neuro-Vascular (CNV) registry.

Setting

6 emergency medical services, 30 emergency units (EUs), 14 hospitalisation units and 11 cathlabs in the Aquitaine region.

Participants

This study involved 9218 patients (6436 patients who had a stroke and 2782 patients who had an STEMI) in the CNV Registry from January 2019 to August 2020.

Method

Hospital reorganisations, retrieved in a scoping review, were collected from heads of hospital departments. Other data were from the CNV Registry. Associations between reorganisations, use of care and care management times were analysed using multivariate linear regression mixed models. Interaction terms between use-of-care variables and period (pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave) were introduced.

Main outcome measures

STEMI cohort, first medical contact-to-procedure time; stroke cohort, EU admission-to-imaging time.

Results

Per-wave period management times deteriorated for stroke but were maintained for STEMI. Per-wave changes in use of care did not affect STEMI management. No association was found between reorganisations and stroke management times. In the STEMI cohort, the implementation of systematic testing at admission was associated with a 41% increase in care management time (exp=1.409, 95% CI 1.075 to 1.848, p=0.013). Implementation of plan blanc, which concentrated resources in emergency activities, was associated with a 19% decrease in management time (exp=0.801, 95% CI 0.639 to 1.023, p=0.077).

Conclusions

The pandemic did not markedly alter the functioning of the emergency network. Although stroke patient management deteriorated, the resilience of the STEMI pathway was linked to its stronger structuring. Transversal reorganisations, aiming at concentrating resources on emergency care, contributed to maintenance of the quality of care.

Trial registration number

Keywords: COVID-19, health policy, organisation of health services, quality in health care, myocardial infarction, stroke

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study analysed two large high-quality data cohorts comprising almost 10 000 patients who had a stroke and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), managed in a large panel of care structures throughout the Aquitaine region, over a period of several months before and after the first wave.

We evaluated reorganisations implemented by care structures in the management of patients who had a stroke and STEMI to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The explanatory analyses yielded robust results due to the large amount of data collected (clinical characteristics, sociogeographical factors, acute care management pathway data), enabling integration of confounding factors identified by the directed acyclic graph method.

The exclusion of patients who did not enter the healthcare system prevented quantification of avoidance of the healthcare system, which is thought to have been more frequent during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data were restricted to the Aquitaine region, which was less affected by the first wave of the pandemic; this hampers the geographical generalisability of results on the effects of reorganisations focused on emergency units, which were more sensitive to patient influx.

Introduction

Governments worldwide responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with unprecedented policies that affected healthcare systems, and that were designed to slow the growth rate of the infection.1–3 France was one of the most affected countries in the early months of the pandemic.4 From March to May 2020, French authorities implemented a nationwide lockdown and a series of policies to curb the surge of patients requiring critical care. The French healthcare system was at that time almost entirely devoted to the fight against SARS-CoV-2.

These profound changes were likely to have had a negative impact on the delivery of medical and surgical services. Use of care was altered5; all countries that implemented policies to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 experienced a marked decrease in the number of patients entering emergency rooms for reasons other than COVID-19, revealing a tendency to delay or even forego care.6–9

Concerns rose about the quality of management of acute conditions other than COVID-19, particularly stroke and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the most highly time-sensitive conditions.10 11 Management pathways for these two diseases have long been established, based initially on the patient’s use of the emergency medical service (EMS) system in the event of an extreme emergency, followed by relays between emergency structures and specialised technical platforms (cathlabs, stroke units). These care pathways depend on collaboration among various professionals in prehospital and intrahospital areas. These predefined pathways may have been undermined by the organisational and societal upheavals associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, international literature agrees that the COVID-19 pandemic substantially decreased the rate of stroke and STEMI admissions and the number of procedures, and increased the interval from symptom onset to hospital treatment; these latest appearing driven predominantly by delays in use of care and transfers.12

However, results on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the intrahospital quality of care of these two diseases are diverse.13–16 We hypothesised that this may be due to the organisational environment of hospitals and the timing and type of reorganisations implemented to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond national directives, each hospital had authority over its reorganisation, according to local capacity. To date, no study has quantified the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delivery of stroke and STEMI care.

Since 2012, the Aquitaine region (southwestern France, 3 million inhabitants) has implemented a regional registry of Cardio-Neuro-Vascular pathologies (CNV Registry), enabling analysis of the care pathway of patients who had an STEMI and stroke in Aquitaine hospitals. Therefore, there is a unique opportunity to study changes in care management in the region over time.17

We assessed the impact of changes in use of care and health reorganisation spurred by the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on care management times of patients who had an STEMI and stroke hospitalised in the Aquitaine region. We also analysed the use and quality of care provided to these patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was based on two retrospective cohorts of patients who had a stroke and STEMI. We performed ad hoc evaluation of the reorganisations implemented by healthcare structures in the Aquitaine region during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The two cohorts comprised adult patients, living in metropolitan France, and admitted to a care structure involved in the CNV Registry with recent stroke or STEMI, from 1 January 2019 to 31 August 2020.17 The STEMI cohort comprised recent patients who had an STEMI<24 hours from symptom onset, managed in 6 EMSs, 30 emergency units (EUs) and 11 cathlabs in Aquitaine. The stroke cohort comprised patients who had a recent ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke diagnosed by brain imaging with validation by a neurovascular physician (exclusion of transient ischaemic attacks), managed in 5 of the 6 EMSs and 14 (including 7 stroke units) of the 20 hospitals caring for >30 strokes per year in Aquitaine. The CNV Registry has been approved by the French authority on data protection and meets the regulatory requirements for patient information (file 2216283).

Data collection

Stroke and STEMI cohorts

Data were collected from each care structure at each step of the care pathway:

In EMSs, data entered in electronic care records were extracted from the hospital information system.

In EUs, data were entered prospectively by physicians in dedicated paper or electronic care records and extracted or collected retrospectively by clinical research assistants.

In cathlabs or stroke hospitalisation units, data were entered prospectively by physicians, and then extracted.

Data of the two cohorts were consolidated and incorporated into one data warehouse, allowing the reconstruction of the STEMI or stroke management pathway.

The CNV Registry collects information on:

Patient sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, place of residence.

Patient clinical characteristics: medical history, cardiovascular risk factors, stroke clinical severity (modified Rankin Scale and National Institute of Health Stroke Score (NIHSS)) and stroke type (ischaemic/haemorrhagic).

Use of care (table 1): calls to emergency services, first medical contact (FMC) and symptom-to-care time.

Acute care management quality (table 1): intervals between key management steps (stroke, EU admission-to-imaging time; STEMI, FMC-to-procedure time), prehospital and hospital pathways, mode of transport to the EU, orientation to stroke unit or cathlab and treatment (stroke, first imaging type, IV thrombolysis (IVT) in ischaemic stroke, mechanical thrombectomy in ischaemic stroke; STEMI, fibrinolysis, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary angiography alone).

Structural characteristics of care: care during on-call activity, calls to emergency services during care, administrative status of the hospital and FMC-to-cathlab distance. For the stroke cohort, availability of MRI 24 hours a day, stroke unit and interventional neuroradiology unit.

Table 1.

Definition of use of care variables, acute care management quality variables and geographical indexes

| Variables | Definition |

| Use of care | |

| Calls to emergency services | Patient call to emergency services after the onset of symptoms. |

| FMC | First medical team to take care of the patient:

|

| Symptoms-to-care time | Delay in minutes between symptoms onset and start of management by the healthcare system, either call to emergency services or EU admission in case of no call to emergency services. |

| Acute care management quality | |

| EU admission-to-imaging time | Delay in minutes between EU admission and start of the first imaging (MRI or CT scan). |

| FMC-to-procedure time | Delay in minutes between FMC and the start of the treatment procedure (coronary angiography or PCI). |

| IVT in ischaemic stroke | Two variables:

|

| Geographical indexes | |

| Urbanicity | Urban defined as commune or group of communes with a continuous built-up area with at least 2000 inhabitants. |

| FDep15 | Validated social level index calculated from four variables attributed to each commune: median household income, proportion of baccalaureate, proportion of workers in the active population and unemployment rate. |

| APL MG 2018 | Index calculated from the supply of general practitioners, the demand for care and the distance between the place of residence and the supply of care. |

Created by the authors.

APL MG 2018, potential accessibility indicator to general practitioners; CT, computerized tomography scan; EU, emergency unit; FDep15, deprivation index; FMC, first medical contact; IVT, IV thrombolysis; MICU, mobile intensive care units; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Place of residence was used to calculate distances between residence and care structures and three geographical indices: urbanicity, deprivation index (FdeD15), potential accessibility to general practitioners (APL MG 2018) (table 1).18–20

Reorganisations implemented in healthcare structures

A scoping review was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations21 to evaluate the structural reorganisations implemented in care structures related to acute management of patients who had a stroke and STEMI, to deal with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (online supplemental material 1).22 The retrieved reorganisations were classified according to care structure: in EMSs (‘increase in the telephone reception capacities’, ‘restriction of helicopter transport for COVID-19 patients’), EUs (‘systematic COVID-19 testing’, ‘separate COVID-19/non-COVID-19 patients pathway’, ‘decrease in non-COVID-19 patients management and admission capacities’, plan blanc (emergency plan to cope with a sudden increase of activity)) and stroke or STEMI hospitalisation units (‘coronary angiography room dedicated to COVID-19 patients in cathlabs’, ‘deprogramming of non-urgent procedures or hospitalisations’, ‘decrease in bed capacity for non-COVID patients’, ‘specific access to imaging for COVID-19 patients’). The retrieved reorganisations were compiled into a questionnaire addressed to the care-structure heads who were asked to indicate, for each reorganisation, whether it had been implemented and, if so, its dates of implementation and of termination.

bmjopen-2022-061025supp001.pdf (173.8KB, pdf)

Care management times

The primary endpoints were the FMC-to-procedure time and EU admission-to-imaging time for the STEMI and stroke cohorts, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed separately for each cohort. Three periods were defined according to the dates of implementation of the first hospital reorganisations and termination of national lockdown: pre-wave (1 January 2019 to 9 February 2020), per-wave (10 February to 10 May 2020) and post-wave (11 May, to 31 August 2020). Use-of-care and acute-care management quality variables were compared among the three periods (χ2 test or Fisher exact test for qualitative variables, and Kruskal-Wallis test for quantitative variables. P values were corrected by the false discovery rate method to account for the multiplicity of tests).

The associations between reorganisations (STEMI, nine variables; stroke, five variables), use of care (STEMI, two variables; stroke, two variables) and care management times (introduced as continuous variables after logarithmic transformation) were analysed using a multivariate linear regression mixed model (two random effects on hospital and health territory). Interaction terms between the use-of-care variables and period (pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave) were introduced. The confounding variables were identified by means of a directed acyclic graph (DAG) (online supplemental material 2).

bmjopen-2022-061025supp002.pdf (151.3KB, pdf)

The relationships between reorganisations or use of care and care management times were quantified (β) by the contrast method (statistical significance p<0.05) and the exponentials of the betas (exp (β)); their 95% CIs and percentage changes (1−exp (β)) were calculated.

For the stroke cohort, a sensitivity analysis was carried out by adding the variable symptoms-to-care time to the model. This variable was not introduced in principal analysis because it presented more than 20% missing data. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement statement

As members of the CNV Registry scientific boards, patient representatives were involved in study conception, implementation and dissemination; they validated data collection and analysis, and results diffusion. Dissemination of results was conducted on the CNV Registry website, to the scientific boards and to care-structure physicians.

This study is reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04979208).

Results

Study sample

The study sample comprised 9218 patients: 6008 pre-wave, 1487 per-wave and 1723 post-wave. The mean number of included patients was stable during the pre-wave and post-wave periods (weekly mean number (SD) of inclusions: 32 (6) STEMIs pre-wave, 32 (5) STEMIs post-wave; 83 (8) strokes pre-wave, 75 (7) strokes post-wave). At the beginning of the per-wave period (weeks 7–15), inclusions of stroke (lowest weekly number, 56) and STEMI (lowest weekly number, 22) patients decreased, followed by a slow increase that continued into the post-wave period.

A total of 6436 patients who had a stroke (5669 (88.1%) with ischaemic stroke and 767 (17.9%) with haemorrhagic stroke) was managed in 5 EMSs, 14 EUs and 14 hospitalisation units (7 stroke units); the 2782 patients who had an STEMI were managed in 6 EMSs, 30 EUs and 11 cathlabs. The median age was younger in the stroke cohort during the per-wave and post-wave compared with the pre-wave periods (77 and 76 years vs 79 years) and the median age of patients who had an STEMI was similar in the three periods. In the STEMI cohort, a lower proportion of women (24.1% vs 27.6% and 26.6%) and a higher proportion of patients with hypertension history (54.1% vs 48.0% and 47.1%) were observed during the per-wave period compared with the pre-wave and post-wave periods. In the stroke cohort, the frequency of severe strokes was lower in the per-wave and post-wave periods (56.2% and 57.3%, respectively, of patients who had a stroke with NIHSS<7) than in the pre-wave period (52.8%) (online supplemental file 3).

bmjopen-2022-061025supp003.pdf (198.2KB, pdf)

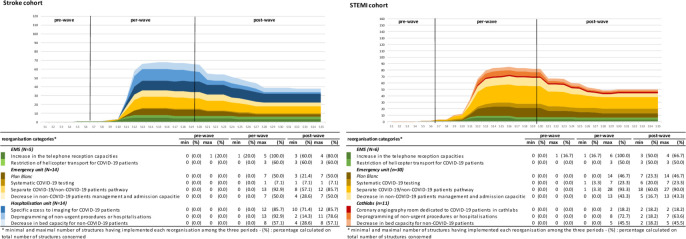

Reorganisations implemented in care structures

Reorganisations began in early February 2020. In the middle of the per-wave period, 83% of EMSs, 90% of EUs, 93% of stroke hospitalisation units and 64% of cathlabs had implemented at least one reorganisation. The two most frequently implemented reorganisations were ‘increase in the telephone reception capacities’ (implemented in all EMSs) and ‘separate COVID-19/non-COVID-19 patients pathways’ (implemented by 93% of EUs; n=13 for stroke, n=28 for STEMI). Half of the EUs implemented plan blanc. Most reorganisations implemented during the per-wave period were maintained in the post-wave period (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weekly cumulated number of care structures having implemented reorganisations, by reorganisation category—minimum and maximum number and proportion of care structures having implemented reorganisation, by reorganisation category and by period (pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave). EMS, emergency medical service; EU, emergency unit; plan blanc, emergency plan to cope with a sudden increase of activity; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Use of care and acute care management quality in the pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave periods

Use of care

In the per-wave compared with the pre-wave periods, calls to emergency services (stroke, 65.5% vs 61.5%; STEMI, 81.8% vs 77.4%) and the median symptom-to-care interval (stroke, 139 min vs 121 min; STEMI, 84 min vs 76 min) increased in both cohorts. These values returned to their previous levels during the post-wave period, except for calls to emergency services for stroke, which remained high (see tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of use of care and acute care management quality characteristics between the pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave periods

| Global (N=6436) | Pre-wave (N=4140) | Per-wave (N=1080) | Post-wave (N=1216) | P value corrected (FDR) | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Use of care | |||||||||

| Calls to emergency services | 6430 | 4135 | 1079 | 1216 | 0.083* | ||||

| No | 2399 | (37.3) | 1590 | (38.5) | 372 | (34.5) | 437 | (35.9) | |

| Yes | 4031 | (62.7) | 2545 | (61.5) | 707 | (65.5) | 779 | (64.1) | |

| Missing values | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| FMC | 6436 | 4140 | 1080 | 1216 | 0.332* | ||||

| EU | 6278 | (97.5) | 4040 | (97.6) | 1059 | (98.1) | 1179 | (9.0) | |

| MICU | 158 | (2.5) | 100 | (2.4) | 21 | (1.9) | 37 | (3.0) | |

| Symptoms-to-care time (min) | 3157 | 1991 | 556 | 610 | 0.232† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 126 | (38;401) | 121 | (38;384) | 139 | (46;488) | 125 | (38;392) | |

| Missing values | 3279 | 2149 | 524 | 606 | |||||

| Acute care management quality | |||||||||

| EU admission-to-imaging time (min) | 4819 | 3014 | 889 | 916 | 0.332† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 86 | (47;194) | 83 | (45;201) | 91 | (51;175) | 88 | (52;191) | |

| Missing values | 1617 | 1126 | 191 | 300 | |||||

| Prehospital pathway type | 6430 | 4135 | 1079 | 1216 | 0.040* | ||||

| Optimal pathway: calls to emergency services/MICU transport/EU | 3719 | (57.8) | 2368 | (57.3) | 642 | (59.5) | 709 | (58.3) | |

| Calls to emergency services/non-MICU transport/EU | 312 | (4.9) | 177 | (4.3) | 65 | (6.0) | 70 | (5.8) | |

| EU direct entry | 2399 | (37.3) | 1590 | (38.5) | 372 | (34.5) | 437 | (35.9) | |

| Missing values | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Mode of transport to the EU | 6436 | 4140 | 1080 | 1216 | 0.812* | ||||

| Personal transport | 732 | (11.4) | 475 | (11.5) | 117 | (10.8) | 140 | (11.5) | |

| Non-MICU transport | 4495 | (69.8) | 2902 | (70.1) | 758 | (70.2) | 835 | (68.7) | |

| MICU transport | 222 | (3.4) | 149 | (3.6) | 34 | (3.1) | 39 | (3.2) | |

| Unknown | 987 | (15.3) | 614 | (14.8) | 171 | (15.8) | 202 | (16.6) | |

| Transfer to a stroke unit | 6436 | 4140 | 1080 | 1216 | 0.923* | ||||

| No | 752 | (11.7) | 484 | (11.7) | 123 | (11.4) | 145 | (11.9) | |

| Yes | 5684 | (88.3) | 3656 | (88.3) | 957 | (88.6) | 1071 | (88.1) | |

| First imaging type | 6041 | 3870 | 1019 | 1152 | 0.332‡ | ||||

| MRI | 3782 | (62.6) | 2395 | (61.9) | 650 | (63.8) | 737 | (64.0) | |

| CT scan | 2245 | (37.2) | 1463 | (37.8) | 369 | (36.2) | 413 | (35.9) | |

| None | 14 | (0.2) | 12 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.2) | |

| Missing values | 395 | 270 | 61 | 64 | |||||

| IVT (all ischaemic strokes) | 5660 | 3616 | 938 | 1106 | 0.011* | ||||

| No | 4635 | (81.9) | 2913 | (80.6) | 801 | (85.4) | 921 | (83.3) | |

| Yes | 1025 | (18.1) | 703 | (19.4) | 137 | (14.6) | 185 | (16.7) | |

| Missing values | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||||

| Exclusion | 767 | 523 | 139 | 105 | |||||

| IVT in ‘thrombolysis alert’ patients (ischaemic stroke) | 1758 | 1100 | 310 | 348 | 0.011* | ||||

| No | 1060 | (60.3) | 634 | (57.6) | 213 | (68.7) | 213 | (61.2) | |

| Yes | 698 | (39.7) | 466 | (42.4) | 97 | (31.3) | 135 | (38.8) | |

| Missing values | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Exclusion | 4676 | 3039 | 770 | 867 | |||||

| Mechanical thrombectomy (all ischaemic stroke) | 5620 | 3585 | 938 | 1097 | 0.332* | ||||

| No | 4998 | (88.9) | 3170 | (88.4) | 842 | (89.8) | 986 | (89.9) | |

| Yes | 622 | (11.1) | 415 | (11.6) | 96 | (10.2) | 111 | (10.1) | |

| Missing values | 49 | 32 | 3 | 14 | |||||

| Exclusion | 767 | 523 | 139 | 105 | |||||

Stroke cohort (N=6436).

*χ2 test.

†Kruskal-Wallis test.

‡Fisher exact test.

CT, computerized tomography scan; EU, emergency unit; FDR, correction of p value by false discovery rate method; FMC, first medical contact; IVT, IV thrombolysis; MICU, mobile intensive care units; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 3.

Comparison of use of care and acute care management quality characteristics between the pre-wave, per-wave and post-wave periods

| Global (N=2782) | Pre-wave (N=1868) | Per-wave (N=407) | Post-wave (N=507) | P value corrected (FDR) | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Use of care | |||||||||

| Calls to emergency services | 2782 | 1868 | 407 | 507 | 0.704* | ||||

| No | 607 | (21.8) | 422 | (22.6) | 74 | (18.2) | 111 | (21.9) | |

| Yes | 2175 | (78.2) | 1446 | (77.4) | 333 | (81.8) | 396 | (78.1) | |

| FMC | 2782 | 1868 | 407 | 507 | 0.704* | ||||

| MICU | 1597 | (57.4) | 1069 | (57.2) | 247 | (60.7) | 281 | (55.4) | |

| EU with cathlab | 458 | (16.5) | 321 | (17.2) | 51 | (12.5) | 86 | (17.0) | |

| EU without cathlab | 727 | (26.1) | 478 | (25.6) | 109 | (26.8) | 140 | (27.6) | |

| Symptoms-to-care time (min) | 2360 | 1581 | 349 | 430 | 0.799† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 77 | (30;206) | 76 | (30;212) | 84 | (31;202) | 75 | (30;178) | |

| Missing values | 422 | 287 | 58 | 77 | |||||

| Acute care management quality | |||||||||

| FMC-to-procedure time (min) | 2364 | 1577 | 353 | 434 | 0.799† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 99 | (71;157) | 100 | (71;158) | 95 | (69;152) | 102 | (71;153) | |

| Missing values | 418 | 291 | 54 | 73 | |||||

| Pathway type | 2742 | 1841 | 400 | 501 | 0.799* | ||||

| Optimal pathway: calls to emergency services/MICU transport/direct referral to cathlab | 1557 | (56.8) | 1042 | (56.6) | 240 | (60.0) | 275 | (54.9) | |

| Calls to emergency services/EU/direct referral to cathlab | 550 | (20.1) | 356 | (19.3) | 82 | (20.5) | 112 | (22.4) | |

| No call to emergency services/EU/direct referral to cathlab | 591 | (21.6) | 412 | (22.4) | 72 | (18.0) | 107 | (21.4) | |

| Calls to emergency services/EU/no direct referral to cathlab | 28 | (1.0) | 20 | (1.1) | 4 | (1.0) | 4 | (0.8) | |

| No call to emergency services/EU/no direct referral to cathlab | 16 | (0.6) | 11 | (0.6) | 2 | (0.5) | 3 | (0.6) | |

| Missing values | 40 | 27 | 7 | 6 | |||||

| Mode of transport to the first hospital | 2782 | 1868 | 407 | 507 | 0.722* | ||||

| Personal transport | 444 | (16.0) | 311 | (16.6) | 55 | (13.5) | 78 | (15.4) | |

| Non-MICU transport | 558 | (20.1) | 372 | (19.9) | 77 | (18.9) | 109 | (21.5) | |

| MICU transport (road) | 1523 | (54.7) | 1010 | (54.1) | 243 | (59.7) | 270 | (53.3) | |

| MICU transport (helicopter) | 123 | (4.4) | 84 | (4.5) | 11 | (2.7) | 28 | (5.5) | |

| Unknown | 134 | (4.8) | 91 | (4.9) | 21 | (5.2) | 22 | (4.3) | |

| Direct referral to cathlab | 2782 | 1868 | 407 | 507 | 0.799* | ||||

| No | 84 | (3.0) | 58 | (3.1) | 13 | (3.2) | 13 | (2.6) | |

| Yes | 2698 | (97.0) | 1810 | (96.9) | 394 | (96.8) | 494 | (97.4) | |

| Fibrinolysis | 2560 | 1724 | 366 | 470 | 0.799* | ||||

| No | 2428 | (94.8) | 1633 | (94.7) | 345 | (94.3) | 450 | (95.7) | |

| Yes | 132 | (5.2) | 91 | (5.3) | 21 | (5.7) | 20 | (4.3) | |

| Missing values | 222 | 144 | 41 | 37 | |||||

| PCI | 2364 | 1577 | 353 | 434 | 0.799* | ||||

| No | 330 | (14.0) | 211 | (13.4) | 50 | (14.2) | 69 | (15.9) | |

| Yes | 2034 | (86.0) | 1366 | (86.6) | 303 | (85.8) | 365 | (84.1) | |

| Missing values | 418 | 291 | 54 | 73 | |||||

| Fibrinolysis or PCI | 2359 | 1576 | 349 | 434 | 0.704* | ||||

| No | 292 | (12.4) | 190 | (12.1) | 38 | (10.9) | 64 | (14.7) | |

| Yes | 2067 | (87.6) | 1386 | (87.9) | 311 | (89.1) | 370 | (85.3) | |

| Missing values | 423 | 292 | 58 | 73 | |||||

STEMI cohort (N=2782).

*χ2 test.

†Kruskal-Wallis test.

EU, emergency unit; FDR, correction of p value by false discovery rate method; FMC, first medical contact; MICU, mobile intensive care units; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Care management quality

The stroke median EU admission-to-imaging time increased (91 min vs 83 min) and the STEMI median FMC-to-procedure time decreased (95 min vs 100 min) in the per-wave compared with the pre-wave period. The management time remained high for stroke (88 min) and increased for STEMI (102 min) in the post-wave period.

In the stroke cohort, the proportion of IVT decreased during the per-wave compared with the pre-wave and post-wave periods (all ischaemic strokes, 14.6% vs 19.4% and 16.7%, p=0.011; IVT alert patients, 31.3% vs 42.4% and 38.8%, p=0.011) and the proportion of patients with an optimal pathway (calls to emergency services/mobile intensive care units (MICU) transport/EU) was larger during the per-wave period (59.5%) compared with the pre-wave (57.3%) and post-wave (58.3%, p=0.040) periods.

Associations between use of care, reorganisations, and care management times

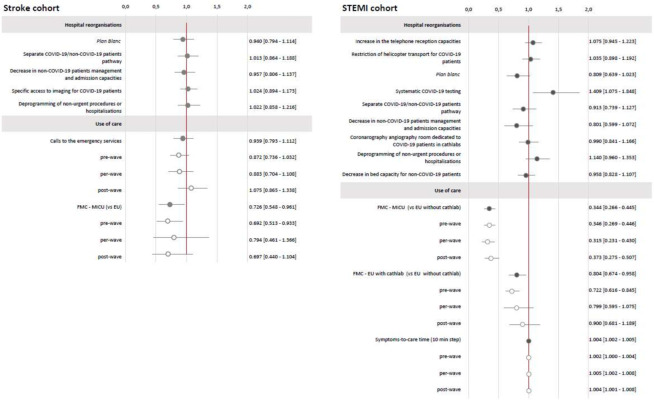

Stroke cohort model (4603 patients)

The final model showed no statistically significant association between reorganisations and EU admission-to-imaging time. FMC by MICU transport was associated with a significant decrease of 27% in the EU admission-to-imaging time (expβ=0.726, 95% CI 0.548 to 0.961, p=0.034), with no interaction with COVID-19 period (p=0.807). The association between calls to emergency services and EU admission-to-imaging time was not significant (expβ=0.939, 95% CI 0.793 to 1.112, p=0.360) during the study period but differed according to COVID-19 period (significant interaction with the COVID-19 period, p=0.039). Calls to emergency services were associated with an 8% increase in admission-to-imaging time during the post-wave compared with the pre-wave and per-wave periods. Sensitivity analysis of 2458 patients confirmed the absence of an association between reorganisations or use-of-care changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and care management times (see figure 2 and online supplemental material 4).

Figure 2.

Stroke and STEMI cohorts. Estimation of the reorganisations and use of care effects (95% CI) on care management times. Stroke cohort (N=4603)—estimated overall effects expressed as exp(β) with 95% CI; results of multivariate linear regression mixed models; variable to be explained: Y=log (EU admission-to-imaging time); results adjusted on period, age, gender, urbanicity of residence, FDep15, APL MG 18, residence-EU distance, presence of stroke unit, MRI 24 hours a day, presence of interventional neuroradiology unit, care during on-call activity, mode of transport, calls to emergency services activity, mRS less than 1 before stroke, NIHSS at entry, previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. STEMI cohort (N=1843)—estimated overall effects expressed as exp(β) with 95% CI; results of multivariate linear regression mixed models; variable to be explained: Y=log (FMC-to-procedure time); results adjusted on period, age, gender, urbanicity of residence, FDep15, APL MG 18, residence-to-cathlab distance, cathlab hospital status, care during on-call activity, mode of transport, calls to emergency services activity, FMC-to-cathlab distance, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease or STEMI history). Light grey: interaction with the COVID-19 period, Dark grey: raw results without interaction with the COVID-19 period. APL MG 2018, potential accessibility to general practitioners; EU, emergency unit; FDep15, deprivation index; FMC, first medical contact; MICU, mobile intensive care units; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Score; plan blanc, emergency plan to cope with a sudden increase of activity; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

bmjopen-2022-061025supp004.pdf (272.7KB, pdf)

STEMI cohort model (1843 patients)

Systematic COVID-19 testing was associated with a 41% increase (expβ=1.409, 95% CI 1.075 to 1.848, p=0.013) in the FMC-to-procedure time. The implementation of plan blanc was associated with a 19% decrease (expβ=0.801, 95% CI 0.639 to 1.023, p=0.077) in the FMC-to-procedure time. Compared with FMC ‘EU without cathlab’, FMC ‘MICU transport pathway’ was associated with a 66% decrease (expβ=0.344, 95% CI 0.266 to 0.445, p<0.001) in the FMC-to-procedure time and FMC ‘EU with cathlab’ with a 20% decrease (expβ=0.804, 95% CI 0.674 to 0.958, p<0.001). The interaction with the COVID-19 period was not significant (p=0.492). Finally, each 10 min increase in symptom-to-care time increased the FMC-to-procedure time by 0.36% (expβ=1.004, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.005, p<0.001), and there was no effect of COVID-19 period (p=0.206).

Discussion

We evaluated the global impact of the health system transformations spurred by the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on use of care by, and the acute management of, patients who had a stroke and STEMI.

Beginning in the per-wave period, most hospitals in Aquitaine adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the reorganisations were maintained several months after the end of the national lockdown. Stroke management times deteriorated during the pandemic, but this was not directly related to the reorganisations implemented. By contrast, STEMI patients’ quality of care was maintained during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, to which plan blanc, by concentrating resources in emergency activities, contributed. Implementation of systematic COVID-19 screening at admission was associated with an increase in STEMI patient management time. In the STEMI and stroke cohorts, more frequent calls to emergency services and longer times to access the healthcare system were observed during the per-wave compared with the pre-wave period.

The contrasting changes in STEMI and stroke management times during the per-wave period may be explained by the different structures and performances of the related networks in France. The STEMI network is structured as a dedicated pathway. By contrast, the stroke network is more recent and not fully structured. Highly structured patient-centred clinical pathways improve the quality of care of chronic or acute conditions with predictable trajectories.23–27 Moreover, guidelines on stroke and STEMI patient management and national stroke and STEMI improvement programmes recommend the implementation of structured pathways that include close collaborations between healthcare professionals as well as patient orientation to specialised technical platforms (cathlabs, stroke units) and to the EMS system.28 29

The results suggest the absence of a change in the functioning of the emergency pathway during the pandemic. Indeed, calls to the emergency services by patients who had an STEMI and orientation to the optimal pathway using MICU were associated with decreased stroke and STEMI management times. Therefore, the management of these two highly time-sensitive pathologies was not disrupted during the pandemic.

Plan blanc, which enhanced the quality of care of COVID-19 patients, improved that of patients who had an STEMI by decreasing management times. In the stroke cohort, plan blanc non-significantly decreased management times. The different results may be explained by use of different primary endpoints in the two cohorts. In the STEMI cohort, the FMC-to-procedure time, which accounted for coordination of care among multiple actors pre- and in-hospital, was sufficiently extensive to detect an effect. In the stroke cohort, the EU admission-to-imaging time, which focused on the beginning of in-hospital care, involved so little a part of the patient pathway that it had difficulty in detecting an effect. Most reorganisations implemented in EUs or hospitalisation units had little effect on STEMI and stroke care management times.

Only the ‘systematic COVID-19 testing’ reorganisation increased the STEMI management time. This effect was marked in patients arriving late after symptom onset. In these patients, whose symptoms were often atypical and included respiratory signs suggestive of COVID-19, management was delayed until availability of screening results. Patients who had an STEMI arriving very early were regarded as requiring extreme emergency management before screening. The ‘systematic COVID-19 testing’ reorganisation was not included in the stroke cohort model, but the only hospital in the stroke cohort that implemented it exhibited results similar to the STEMI cohort.

The increased time to contact the healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic is consistent with prior reports from France and elsewhere.6 13 30 Mesnier et al, in a French cohort of 1167 patients who had an STEMI, found that symptom onset to hospital admission times were stable from 4 weeks before to 4 weeks after lockdown implementation. However, comparison of that work and ours is hampered by differences in management times and study periods.7

By calling the emergency services more frequently, patients followed the national recommendations, which were widely publicised in the French media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although a global decrease in STEMI and stroke patient admissions during the per-wave period has been reported, the average figures over the period31 suggest an initial decrease at the beginning of the per-wave period and a progressive increase thereafter. These findings, mirrored by other surveys at the regional or national level in France, are based on analysis of changes in hospital admissions during the per-wave period.32 33 Patients who had a stroke were younger, and had less severe strokes during the per-wave compared with the pre-wave period. Although several studies, including one meta-analysis, reported more severe and older patients during the first wave of the pandemic, others reported findings consistent with ours.31 34–38 Wallace et al suggested this to be a consequence of regional variation in virus spread and the fear of contracting COVID-19 in hospital. Alternatively, most studies included patients with transient ischaemic attacks; these were excluded in this work. Patients with resolving and less-severe symptoms were more likely to avoid hospital admission for fear of contracting COVID-19 in hospital. Lastly, information on the origin of hospitalised patients (home, nursing homes, other hospitals) would have been useful but was not available in the databases.

Prior studies investigating the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and the quality of stroke and STEMI management reported diverse results.13–16 Our data suggest that these discordant results are a result of the variety of policies implemented and the heterogeneity of hospital organisations. To our knowledge, no study has analysed at a regional level the effect of reorganisations implemented by hospitals to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. Those extant simply provide feedback on reorganisations at a local level.11 39 40

We analysed two high-quality databases with a large number of patients who had a stroke and STEMI managed in numerous healthcare institutions in Aquitaine. This broad geographical scope, which ensured diverse clinical and management characteristics, and the historical depth of the data are major strengths of this study.

The sample was representative of patients who had a stroke and STEMI managed in hospitals. However, patients who did not enter the healthcare system because they had died or did not benefit from hospital care were not included. This precluded quantification of avoidance of the healthcare system, which is thought to have been more frequent during the COVID-19 pandemic and may have generated selection bias. Moreover, the STEMI cohort included patients who experienced STEMI within 24 hours of admission. The proportion of patients who had an STEMI presenting>24 hours after symptom onset increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and these individuals had more so called ‘mechanical complications’ and a higher mortality rate.41 The exclusion of these patients may have generated selection bias, leading to a risk of underestimation of the increased delay to use of care.

We conducted a systematic evaluation of hospital reorganisations implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of errors in the responses of the healthcare professionals, particularly concerning the dates on which reorganisations were implemented or terminated, due to memory bias. It was not feasible to interview several individuals and cross-check the responses.

Explanatory analyses by the DAG method yielded several confounding factors. The large amount of data enabled integration of a variety of confounders—clinical and sociogeographic factors, acute care management pathways and hospital activity. In the stroke cohort, 20% of the symptom-to-FMC data were missing, so we excluded this variable from the main model to increase the statistical power. The lack of a reason for these missing data precluded their analysis by the multiple imputation method. A sensitivity analysis with symptom-to-FMC time as an explanatory variable did not alter the results, confirming their robustness.

The primary endpoints were the care management times, which are major prognostic issues in the management of stroke and STEMI and sensitive to intrahospital organisational changes. They were used as continuous variables to maximise the statistical power. Use of the proportion of patients managed within the recommended time frame as an endpoint would have had marked operational implications. However, this was not possible for statistical reasons (3.3% of patients underwent the first imaging within 20 min, the target time).

A major methodological issue was per-wave period, which was defined according to implementation of healthcare reorganisations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the per-wave period began simultaneously with the first hospital reorganisations, and ended at the end of the lockdown, which corresponded to restoration of normal hospital activity and a reduction in the number of reorganisations. The post-wave period was an important component of our analysis of changes in patient management. However, the follow-up ended at the end of August, to produce not too late results. The inclusion of summer is unlikely to have generated bias because no summer variation in stroke and STEMI inclusion or management delay has been reported.

This study was restricted to Aquitaine, one of the regions least affected by the first wave of the pandemic.6 We hypothesised that the ‘decrease in non-COVID patients management and admission capacities’, which did not affect STEMI and stroke patient management times, would have degraded the management of non-COVID-19 conditions in regions with many EUs. Indeed, the impact of EU reorganisations may be sensitive to patient influx. Moreover, the effects of global and structural reorganisations such as plan blanc should not differ geographically. Because use of care did not differ according to pandemic intensity, our results are unlikely to apply only to Aquitaine.33 It would be interesting to repeat the study in another region of France or in another country more affected by the pandemic to test the external validity of the results.

Stroke and STEMI are managed by means of defined pathways. Our results may be extrapolated to similar conditions requiring urgent management in a coordinated pathway, such as respiratory distress or life-threatening bleeding.

Perspectives

This study is the first step of a three-step analysis of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on stroke and STEMI patient management. Other issues are the clinical and social health inequalities in stroke and STEMI patient management induced or reinforced by the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the long-term mortality and morbidity of stroke and STEMI patients.

Conclusions

There was no alteration of emergency pathway structure during the COVID-19 pandemic, but stroke patient management deteriorated. The resilience of the STEMI pathway was due to its stronger structuring. Also, transversal reorganisations, aimed at concentrating resources within the emergency care network, such as plan blanc, contributed to maintaining the quality of care of patients who had a stroke and STEMI. Our results can be extrapolated to other time-sensitive conditions that require coordination of EMSs and benefit from a defined pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank funders of the project ('Alliance Tous unis contre le virus', which includes the 'Fondation de France', the 'AP-HP' and the 'Institut Pasteur'), of the CNV Registry ('Nouvelle-Aquitaine Regional Health Agency'), association of patients ('AVC tous concernés', 'France assos santé'), the CNV Registry team (Charlotte Boureau, Sandrine Domecq, Déanna Duchateau, Céline Dupuis, Florian Gilbert, Cristelle Gill, Camille Glenisson, Majdouline Lahrach, Leslie Larco, Jean-Pierre Legrand, Mélanie Maugeais, Sahal Miganeh-Hadi, Corinne Perez, Lucas Perez, Théo Poncelet, Olivia Rick, Floriane Sevin, Gwenaëlle Soudain), Julien Asselineau, Vincent Bouteloup, Moufid Hajjar, Marion Kret, Caroline Ligier, Vincent Thevenet, Rodolphe Thiebaut and all healthcare professionals participating in the CNV Registry.

Footnotes

Collaborators: AVICOVID group: JM Faucheux, E Leca Radu, G Seignolles, C Chazalon, M Dan, L Lucas, J Péron, L Wong So, M Martinez, C Nocon, V Hostyn, J Papin, P Bordier, P Casenave, L Maillard, B Ondze, I Argacha, E Tidahy, L Ferraton, Y Mostefai, S Demasles, R Hubrecht, D Bakpa, C Bartou, S Bannier, P Bernady, E Ellie, D Higue, G Marnat, J Berge, C Goze-Dupuy, H Lavocat, F Senis, V Delonglee, D Darraillans, T Mokni, B Bataille, JP Lorendeau, A Eclancher, B Trogoff, V Chartroule, P Touchard, H Leyral, C Ngounou Fogue, C Scouarnec, F Orcival, N Goulois, L Wong-So, V Heydel, B Tahon, E Py, S Bidian, J Fabre, N Cherhabil, L Baha, PA Fort, V Maisonnave, L Verhoeven, P Claveries, E Ansart, B Lefevre, MP Liepa, M Lacrouts, JB Coustere, P Fournier, P Jarnier, N Delarche, JL Banos, N Marque, B Karsenty, JM Perron, JL Leymarie, A Hassan, F Casteigt, B Larnaudie, X Combes, G Laplace.

Contributors: EL, FSaillour, SD and FSevin were responsible for the study concept and design. EL, FF, FSaillour conducted the literature review and MB, QL the scoping review. EL and FSevin had full access to all of the data and takes responsibility for their integrity and accuracy. SD, SM-H performed the statistical analysis. FSaillour, EL, SD, FF, FSevin, LC, PC, FR, IS, CP interpreted the data. EL, FSaillour, FF and SD wrote the manuscript. FSevin, LC, PC, FR, IS and CP critically reviewed the manuscript. EL accept full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This work was supported by 'Alliance Tous unis contre le virus', which includes the 'Fondation de France', the 'AP-HP' and the 'Institut Pasteur' grant number 00107870 and the 'Nouvelle-Aquitaine Regional Health Agency'.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: AVICOVID group, JM Faucheux, E Leca Radu, G Seignolles, C Chazalon, M Dan, L Lucas, J Péron, L Wong So, M Martinez, C Nocon, V Hostyn, J Papin, P Bordier, P Casenave, L Maillard, B Ondze, I Argacha, E Tidahy, L Ferraton, Y Mostefai, S Demasles, R Hubrecht, D Bakpa, C Bartou, S Bannier, P Bernady, E Ellie, D Higue, G Marnat, J Berge, C Goze-Dupuy, H Lavocat, F Senis, V Delonglee, D Darraillans, T Mokni, B Bataille, JP Lorendeau, A Eclancher, B Trogoff, V Chartroule, P Touchard, H Leyral, C Ngounou Fogue, C Scouarnec, F Orcival, N Goulois, L Wong-So, V Heydel, B Tahon, E Py, S Bidian, J Fabre, N Cherhabil, L Baha, PA Fort, V Maisonnave, L Verhoeven, P Claveries, E Ansart, B Lefevre, MP Liepa, M Lacrouts, JB Coustere, P Fournier, P Jarnier, N Delarche, JL Banos, N Marque, B Karsenty, JM Perron, JL Leymarie, A Hassan, F Casteigt, B Larnaudie, X Combes, and G Laplace

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified participant data will be available upon reasonable request. Proposals may be submitted to the corresponding author. Data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

According to French authority on data protection 'Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés', in the category of studies not involving humans based on secondary use of health data, the CNV registry met regulatory requirements for patient information and do not require a patient consent form.

References

- 1.Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2020;584:262–7. 10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brauner JM, Mindermann S, Sharma M, et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science 2021;371:eabd9338. 10.1126/science.abd9338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pullano G, Valdano E, Scarpa N, et al. Evaluating the effect of demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and risk aversion on mobility during the COVID-19 epidemic in France under lockdown: a population-based study. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e638–49. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30243-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaudart J, Landier J, Huiart L, et al. Factors associated with the spatial heterogeneity of the first wave of COVID-19 in France: a nationwide geo-epidemiological study. Lancet Public Health 2021;6:e222–31. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moroni F, Gramegna M, Ajello S, et al. Collateral damage: medical care avoidance behavior among patients with myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep 2020;2:1620–4. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olié V, Carcaillon-Bentata L, Thiam M-M, et al. Emergency department admissions for myocardial infarction and stroke in France during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: national temporal trends and regional disparities. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2021;114:371–80. 10.1016/j.acvd.2021.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesnier J, Cottin Y, Coste P, et al. Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after lockdown according to regional prevalence of COVID-19 and patient profile in France: a registry study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e536–42. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30188-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santana R, Sousa JS, Soares P, et al. The demand for hospital emergency services: trends during the first month of COVID-19 response. Port J Public Health 2020;38:30–6. 10.1159/000507764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markus HS, Brainin M. COVID-19 and stroke—A global world stroke organization perspective. Int J Stroke 2020;15:361–4. 10.1177/1747493020923472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fersia O, Bryant S, Nicholson R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiology services. Open Heart 2020;7:e001359. 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bersano A, Kraemer M, Touzé E, et al. Stroke care during the COVID‐19 pandemic: experience from three large European countries. Eur J Neurol 2020;27:1794–800. 10.1111/ene.14375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiss P, Carcel C, Hockham C, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the care and management of patients with acute cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021;7:18–27. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwok CS, Gale CP, Kinnaird T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart 2020;106:1805–11. 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegler JE, Zha AM, Czap AL, et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on treatment times for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2021;52:40–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinkel LA, Prick JCM, Slot RER, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on acute stroke care. J Neurol 2021;268:403–8. 10.1007/s00415-020-10069-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aktaa S, Yadegarfar ME, Wu J, et al. Quality of acute myocardial infarction care in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic: linked nationwide cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf 2022;31:1–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesaine E, Saillour-Glenisson F, Leymarie J-L, et al. The ACIRA registry: a regional tool to improve the healthcare pathway for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions and coronary Angiographies in the French Aquitaine region: study design and first results. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2020;19:1–8. 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Insee . Définition - Aire urbaine, 2020. Available: https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/definition/c2070

- 19.Rey G, Jougla E, Fouillet A, et al. Ecological association between a deprivation index and mortality in France over the period 1997 – 2001: variations with spatial scale, degree of urbanicity, age, gender and cause of death. BMC Public Health 2009;9:33. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barlet M, Coldefy M, Collin C. L’accessibilité potentielle localisée (APL):une nouvelle mesure de l’accessibilité aux médecins généralistes libéraux. Etudes et résultats DRESS-IRDES 2012;795 https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/er795.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;134:103–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Champagne F, Contandriopoulos AP, Brousselle A. L’évaluation dans le domaine de la santé : concepts et méthodes. In: L’évaluation : concepts et méthodes. Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2018: p.49–70. http://books.openedition.org/pum/6300 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sulch D, Perez I, Melbourn A. Evaluation of an integrated care pathway for stroke unit rehabilitation. Age Ageing 2000;29:87. 10.1093/ageing/29.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3:CD006632. 10.1002/14651858.CD006632.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen D, Rixson L. How has the impact of 'care pathway technologies' on service integration in stroke care been measured and what is the strength of the evidence to support their effectiveness in this respect? Int J Evid Based Healthc 2008;6:78–110. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2007.00098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: what works, for whom, in which circumstances? Int J Evid Based Healthc 2009;7:61–74. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2009.00127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trimarchi L, Caruso R, Magon G, et al. Clinical pathways and patient-related outcomes in hospital-based settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Biomed 2021;92:e2021093. 10.23750/abm.v92i1.10639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke 2018;49:e46–110. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunetti V, Broccolini A, Caliandro P, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures on the local stroke network. Neurol Sci 2021;42:1237–45. 10.1007/s10072-021-05045-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katsanos AH, Palaiodimou L, Zand R, et al. The Impact of SARS‐CoV ‐2 on Stroke Epidemiology and Care: A Meta‐Analysis. Ann Neurol 2021;89:380–8. 10.1002/ana.25967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ORU NA . Panorama d’activité des structures d’urgences de la région Nouvelle-Aquitaine, 2020. Available: https://www.oruna.fr/actualites/panorama-des-urgences-2020

- 33.Mariet A-S, Giroud M, Benzenine E, et al. Hospitalizations for stroke in France during the COVID-19 pandemic before, during, and after the National Lockdown. Stroke 2021;52:1362–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsouras C, Karapanayiotides T, Papafaklis M, et al. Greater decline of acute stroke admissions compared with acute coronary syndromes during COVID‐19 outbreak in Greece: Cerebro/cardiovascular implications amidst a second wave surge. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:3452–5. 10.1111/ene.14666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Marchis GM, Wright PR, Michel P, et al. Association of the COVID‐19 outbreak with acute stroke care in Switzerland. Eur J Neurol 2022;29:724–31. 10.1111/ene.15209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amukotuwa SA, Bammer R, Maingard J. Where have our patients gone? the impact of COVID‐19 on stroke imaging and intervention at an Australian stroke center. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2020;64:607–14. 10.1111/1754-9485.13093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hecht N, Wessels L, Werft F-O, et al. Need for ensuring care for neuro-emergencies—lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neurochir 2020;162:1795–801. 10.1007/s00701-020-04437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace AN, Asif KS, Sahlein DH, et al. Patient characteristics and outcomes associated with decline in stroke volumes during the early COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2021;30:105569. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bamias G, Lagou S, Gizis M, et al. The Greek response to COVID-19: a true success story from an IBD perspective. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020;26:1144–8. 10.1093/ibd/izaa143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben Abdallah I. Early experience in Paris with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2020;72:373. 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonnet G, Panagides V, Becker M, et al. St-Segment elevation myocardial infarction: management and association with prognosis during the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2021;114:340–51. 10.1016/j.acvd.2021.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061025supp001.pdf (173.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-061025supp002.pdf (151.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-061025supp003.pdf (198.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-061025supp004.pdf (272.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified participant data will be available upon reasonable request. Proposals may be submitted to the corresponding author. Data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.