Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this project was to identify additional facets of diabetes distress (DD) in Veterans that may be present due to the Veteran’s military-related experience.

Methods:

The study team completed cognitive interviews with Veterans with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to examine how they answered the Diabetes Distress Scale, (DD Scale) a tool that assesses DD. The DD Scale was used due to its strong associations with self-management challenges, physician-related distress, and clinical outcomes.

Results:

Veterans (n = 15) were 73% male, mean age of 61 (SD 8.6), 53% Black, 53% with glycosylated hemoglobin level < 9%, and 67% with prescribed insulin. The DD Scale is readily understood by Veterans, and interpreted. Thematic analysis indicated additional domains affecting DD and T2DM self-management included: access to care, comorbidities, disruptions in routine, fluctuations in emotions and behaviors, interactions with providers, lifelong nature of diabetes, mental health concerns, military as culture, personal characteristics, physical limitations, physical pain, sources of information and support, spirituality, and stigma.

Conclusions:

This study describes how a Veteran’s military experience may contribute to DD in the context of T2DM self-management. Findings indicate clinicians and researchers should account for additional domains when developing self-management interventions and discussing self-management behaviors with individuals with T2DM.

Keywords: Qualitative Research; Diabetes, Type 2; Psychological Distress; Self-Management; Veterans; Cognitive intervie

The self-management burden associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) may negatively impact psychosocial health. Diabetes distress (DD) encompasses the cognitive, physical, and affective experience of living with T2DM, and may present when individuals are overwhelmed by self-care challenges and recognize that T2DM is progressive and uncurable despite adherence to medical reccomendations.1–4 Diabetes distress is associated with T2DM complications, increased stress, poor diet and exercise, and inadequate support environments.1,5–9 High to moderate levels of DD can result in poorer glucose regulation,4 higher glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C),10 lower medication adherence,11 and poorer quality of life.12

Military-related life experiences may impact the Veteran’s self-identity and interactions with other Veterans, civilians, and the healthcare system.13–15 Therefore, Veterans have a unique set of life experiences that may influence their perception of T2DM and engagement in T2DM self-management.16–20 In order to personalize diabetes care to reduce DD, and enhance the effectiveness of this care, ensuring that existing approaches to DD measurement capture Veteran experience is needed. Due to their military experience and training, the etiology of DD may present differently in Veterans than in non-Veterans; therefore, an understanding of how Veterans’ experience DD is critical to developing tailored interventions to improve their engagement in T2DM self-management and their health outcomes.

To our awareness, minimal in-depth qualitative research exists on how Veterans’ experience and describe DD, as measured by the DD Scale, in the context of living with T2DM. The purpose of this project was to address this gap by identifying additional facets of diabetes distress (DD) in Veterans that may be present due to the Veteran’s military-related experience. The aims for this project were to (1) examine the DD Scale’s applicability to Veterans, and (2) obtain insight into domains relevant to understanding DD in Veterans with T2DM.

Methods

The study team completed two rounds of cognitive interviews21,22 via telephone with Veterans. All activities were approved by the local Institutional Review Board (Protocol #002284), Veteran responses were recorded in REDCap, and all files were saved in a secure, firewalled database. The study team discussed and evaluated interview techniques and data collection after round one, and made changes to interview delivery for round two. The Diabetes Distress Scale was used due to its strong associations with self-management challenges, physician-related distress, and clinical outcomes.3,23

Research Design

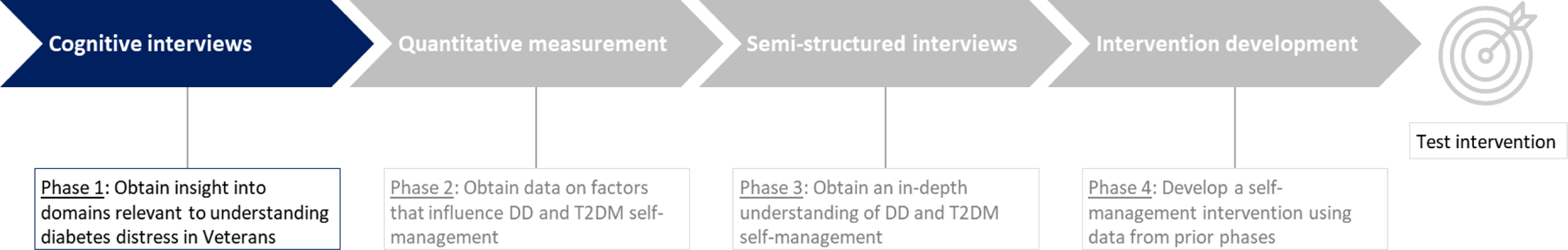

Applied qualitative methods, such as cognitive interviewing, can produce actionable data that can add value to a study by enhancing and increasing the relevance of the knowledge generated.24–27 Cognitive interviews help to assess and improve measurement tools as well as enhance understanding of the phenomenon being studied.22,28 During a cognitive interview, after individuals are read each survey question, these individuals are probed regarding what they believe the question is asking, and invited to describe information used to formulate a response.29 Specific types of probes include concurrent (e.g., assessing real-time thoughts) and retrospective (e.g., assessing thoughts after completion) to clarify responses and obtain further detail. The resulting interview data can indicate the comprehension, retrieval process, judgments, and breadth of information underlying their responses to pre-specified categories.22,28,29 Cognitive interview data can inform (1) refinement of a phenomenon under study, (2) quantitative and qualitative measurement of a phenomenon, (3) selection of appropriate data collection tools, and (4) development of an appropriate research approach and strategy. Additionally, cognitive interviews can help elicit related domains to the phenomenon under study. In the context of a research program examining DD in Veterans with T2DM (Figure 1), obtaining Veterans’ perceptions is essential to verify what constitutes DD in this population, identify barriers to addressing DD, and create potential solutions to DD.

Figure 1.

Phases in a research project to develop a self-management intervention to improve a Veteran’s engagement in and adherence to diabetes self-management.

Sample & Sampling Plan

Veterans with T2DM who received care at a medical center affiliated with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the southeastern United States were invited to complete cognitive interviews. Inclusion criteria included (1) diagnosis of T2DM, (2) documentation of A1C within past 180 days, (3) ability to speak English, and (4) ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included (1) recent diagnosis of T2DM (within the past 60 days), (2) hospitalization within the past 30 days (e.g., mental illness) or 60 days (e.g., myocardial infarction, surgery) that could influence the Veteran’s T2DM regimen, (3) current active chemotherapy or radiation treatment, and (4) cognition issues that could influence ability to provide consent. The study team used a simple sampling plan30 to identify eligible Veterans using the VHA’s electronic health record (EHR). Research staff invited the first 15 eligible Veterans to complete interviews, all of whom agreed to be interviewed. Recruitment of Veterans ceased after analysis of round 2 data as the study team determined that they had achieved information power31 on DD.

Data Collection & Measures

Demographic and Clinical Data

A research assistant used the EHR to obtain each participant’s most recent A1C, age, weight, relevant comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, depression, hyperlipidemia, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety), T2DM medications (e.g., insulin, non-insulin injectable, oral), cardiovascular (e.g., hypertension and/or hyperlipidemia) medications, and confirmation of a VHA visit within the past year. Additional data on demographics (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender identity, income, insurance status, highest level of education completed, marital status, employment), quality of health, impact of Covid-19, alcohol intake, smoking status, and health care obtained outside the VHA were obtained through Veteran self-report.

Diabetes Distress Scale

Diabetes distress is commonly assessed via the Diabetes Distress Scale (DD Scale) in four domains (i.e., regimen, emotional, interpersonal, health care provider).3 The DD Scale measures an individual’s perception of the resources available (or not available) over the past month for self-management.2,5 The DD Scale consists of 17 items that assess DD in four sub-scales (i.e., emotional, regimen, health care provider, interpersonal).3,32 Responses are scored on a 6-point Likert scale from not a problem to a very serious problem.3,32 The DD Scale has proven to be reliable and valid in assessing DD in diverse populations, the factor structure is stable across sites and populations, the measure is parsimonious, and items are clear and readable.1,5,11,12,33 During development, the DD Scale was developed in four samples of adults with diabetes, including samples obtained at two military-affiliated health care clinics.32 Items are not arranged by sub-scale, and responses are reported as a total score as well as by sub-scale.3,32 Means are calculated for the total score and each subscale and are interpreted as: < 2.0 (little or no distress), 2.0–2.9 (moderate distress), ≥ 3.0 (high distress).3,32

Cognitive Interview Questions and Probes

Prior to the start of the interview, a qualitative analyst (a study staff member with expertise in qualitative techniques) read instructions for the DD Scale and administered the scale as published.3,32 Audio files, responses, and interview notes were saved in a secured database behind the firewall. The qualitative analyst began the cognitive interview following each Veteran’s completion of the DD Scale. The analyst could refer to the participant’s responses on the DD Scale during the interview; however, Veterans were not provided with a paper/electronic copy of the DD Scale for reference during the interview. Interview questions (Table 1) referenced the Veteran’s comprehension, understanding, judgment, and retrieval of information related to the concept of DD and the overall administration of the DD Scale. Interviews lasted between 60–75 minutes and were recorded but not transcribed. The qualitative analyst took detailed notes during each interview.

Table 1.

Interview questions and verbal probes.

|

Interview Questions For the survey measure as a whole: 1. Tell me whether you think your experience caring for your diabetes is represented in this survey. (Comprehension) • What were your overall impressions of these questions? 2. Are all aspects of living with diabetes represented in these questions? (Retrieval) • Probe: What, if any, questions are missing? 3. Is there anything about being a Veteran, or having the military experience you do, that affected your answers to these questions? (Judgment) 4. Were there any words or phrases that caused a reaction? (Reaction) For each item: 1. In your own words, what is this question asking? (Comprehension) 2. How did you come up with your answer? (Retrieval) 3. Was this question easy to answer? Hard to answer? (Judgment) 4. Were there any words or phrases that caused a reaction? (Reaction) Closing question: Is there anything else you would like to say about how this survey captured living with diabetes that we did not get a chance to discuss? |

|

Verbal Probes For the survey measure as a whole: • Were there any specific types of experiences that came to mind when we asked these questions? • What do you mean by that? • What was your experience in answering these questions? For each survey item: • How does this question represent your experience of caring for your diabetes? • Was there a particular experience or experiences that you reflected upon while answering the question? • What do you think was meant by this question? • I noticed you chose [RESPONSE CATEGORY]. Tell me a bit about that. ○ What would have made it [LOWER ADJACENT CATEGORY]? ○ Or [HIGHER ADJACENT CATEGORY]? • How sure are you of your answer? • How difficult or easy was it for you come up with an answer? |

Analytic Strategy

A coding team of three authors (AAL, AS, HAK) used thematic analysis34 and the matrix method35 to code and analyze interview response data. After completing each round of interviews, all notes taken during each Veteran’s interview were entered into Microsoft Excel to facilitate analysis by overall measure and item. Two authors (AAL, AS) independently read all entries and wrote summaries for the overall measure, each item, and final considerations. Each summary included five parts: (1) comprehension (interpretation of what the question was asking), (2) retrieval (what information should be provided in response), (3) judgment (ease or difficulty in responding to the question), (4) reaction (emotional reactions experienced while responding to the question), and (5) domains elicited (domains Veterans brought up while discussing the DD Scale in full and by item). The two authors discussed summaries with the third member of the coding team (HK), reconciled differences, and reviewed the Veteran’s demographic data and numerical responses to the DD Scale. Following the analysis of data collected during Round 2, the team created a comprehensive summary for the DD Scale and each item using the summaries from rounds one and two. The coding team used this comprehensive summary to identify similarities and differences across responses. To ensure reliability and validity, the coding team independently created summaries, discussed themes, and shared findings with the larger research team.

Results

Veteran participant (n = 15) characteristics were: 73% male, a mean age of 60.9 (SD 8.6), 53% Black, 53% with A1C < 9%, and 66% with prescribed insulin (Table 2). Veterans had an overall DD Scale score of 2.5 (SD 0.9), indicating moderate distress. When analyzing by subscale, responses indicated high distress for emotional burden (3.0, SD 1.2), moderate distress for regimen (2.6, SD 0.8) and health care provider (2.0, SD 1.5), and little to no distress for interpersonal (1.9, SD 0.9). One Veteran completed the DD Scale and self-report measures but did not complete a cognitive interview. Research staff considered the Veteran lost to follow-up after three attempts to reschedule the Veteran with no response.

Table 2.

Demographic data on respondents.

| Total (n=15) | Round 1 (n=7) | Round 2 (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 61 (8.6) | 62 (4.7) | 60 (11.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 11 (73.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Female | 4 (26.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 15 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 8 (100%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Black | 8 (53.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| White | 6 (40.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Mixed Race | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 7 (46.7%) | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Not Married | 8 (53.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Highschool graduate/GED | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Some college | 9 (60.0%) | 5 (71.4%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| College grad or higher | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (25.5%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Employed | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| Not employed | 10 (66.7%) | 7 (87.5%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Insulin | 10 (66.7%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Non-insulin | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| Less than $30,000 | 9 (60.0%) | 5 (71.4%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| $30,000 to $59,999 | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| More than $60,000 | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Self-rated quality of health, n (%) | |||

| Fair, poor | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Good, very good, excellent | 11 (73.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Impact of coronavirus on answers, n (%) | |||

| Moderate or greater extent | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| None to small extent | 10 (66.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 15 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 8 (100%) |

| High cholesterol | 15 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 8 (100%) |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Depression | 6 (40.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Anxiety | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin, n (%) | |||

| < 9% | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (71.4%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| ≥ 9% | 7 (46.7%) | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Frequency of alcohol intake, n (%) | |||

| 4 or more times per week | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| 2–3 times per week | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| 2–4 times per month | 3 (20.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Monthly or less | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Never | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Visit to a non-VHA health care provider in past year, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| No | 10 (66.7%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Non-VHA insurance or program that helps pay for your prescription medications, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| No | 12 (80.0%) | 6 (85.7%) | 6 (75.0%) |

Note: VHA, Veterans Health Affairs

Conduct of Cognitive Interviews

The team reviewed the participants’ gender, education level, and self-identified race and ethnicity characteristics at the conclusion of the first round of interviews to assess the diversity and representativeness of responses from Veterans and their experiences with DD and the DD Scale. No changes were made to the sampling procedures for Round 2. The qualitative analyst indicated that Veterans struggled to remember the “within the last month” prompt while answering the DD Scale and discussing the DD Scale in the cognitive interview. The coding team decided that the qualitative analyst should provide additional reminders about this prompt during Round 2 interviews. Following the completion of Round 2 interviews, the qualitative analyst reported that providing the additional “within the last month” prompt throughout the interview had helped Veterans respond to the DD Scale and discuss DD Scale items. No additional changes were made to the items in the DD Scale or cognitive interview questions for the second round. Overall, the cognitive interviews were found to be feasible and acceptable both from the viewpoint of the Veteran participants and the qualitative analyst.

Diabetes Distress Scale

Veterans stated that the DD Scale addressed topics important to living with T2DM and DD. Veterans indicated that their T2DM self-management is always present, affects all aspects of life, and requires significant emotional and physical energy. The findings below and in Table 3 describe responses for comprehension, retrieval, judgment, and reaction.

Table 3.

Domains elicited during cognitive interviews and modifications made to subsequent project phases.

| Domain | Definition | Modification | Rationale for Modification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 2 (Quantitative measures) | Phase 3 (Qualitative measures) | |||

| Access to care | Ability to get health care and/or supplies for T2DM self-management, perceived quality of providers, and care coordination. | — | Added probe to interview guide | In-depth responses can inform subsequent study |

| Comorbidities | Management of T2DM with other chronic illnesses, and side-effects of T2DM and other medications | — | Added probe to interview guide | Understanding of comorbidities and medications on T2DM self-management |

| Disruptions in routine | Changes in lifestyle that impact T2DM self-management (e.g., death of a family member, caregiver responsibilities) | — | — | Addressed by proposed measures and interview questions |

| Fluctuations in emotion and behaviors | Changes in emotion, behavior, and motivation after life and health events | — | Added probe to interview guide | In-depth responses can describe fluctuations and self-management |

| Interactions with providers | Interactions and communication with one’s providers | — | — | Addressed by proposed measures and interview questions |

| Lifelong nature of diabetes | Diabetes as a life-long disease | — | Added probe to interview guide | In-depth responses will describe longitudinal experience living with T2DM |

| Mental health concerns | Mental health (e.g., depression) or memory challenges and T2DM self-management | — | Added question to interview guide | In-depth responses can inform subsequent study |

| Military as culture | Military participation and involvement on actions and beliefs | Added questions on military experience | Added question to interview guide | In-depth responses will describe military experience on T2DM self-management |

| Personal characteristics | Statements of personal responsibility or discipline for T2DM self-management | — | — | Addressed by proposed measures and interview questions |

| Physical limitations | Physical effects of T2DM and limitations to physical health | — | Added probe to interview guide | In-depth responses can inform on physical limitations in T2DM self-management |

| Physical pain | Physical pain and engagement in T2DM self-management behaviors and activities | Added measure to examine pain interference | Added probe to interview guide | Data will describe impact of physical pain on T2DM self-management |

| Sources of information and support | Sources of information and support for T2DM self-management | — | — | Addressed by proposed measures and interview questions |

| Spirituality | Statements of faith and religion in relation to T2DM self-management | — | — | Unprompted responses in qualitative interviews can inform subsequent study |

| Stigma | Feelings of shame and feeling different because of T2DM diagnosis and living with T2DM | Added measure to examine stigma | Added question to interview guide | Data will describe impact of stigma on T2DM self-management |

Note: T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; —, no modification made.

Comprehension

Veterans indicated that the DD Scale items were clear, precise, and adequately captured their emotions and experiences of living with T2DM and DD. Veterans interpreted the overall measure and each item, and they understood the content discussed in each item, as the measure developers intended. Variation in responses occurred for two items: “Not feeling confident in my day-to-day ability to manage diabetes” and “Feeling that I will end up with serious long-term complications, no matter what I do.” For the former, some Veterans described their ability to complete their T2DM self-management routine but did not describe their self-confidence in completing the routine. For the latter, some Veterans described challenges in discussing the relationship between present and future actions as well as the effect of these actions on their experience of living with T2DM.

Retrieval

Veterans easily and readily described and recalled relevant information about T2DM self- management and distress for each item. Variation in responses occurred for three items: “Feeling that my doctor doesn’t take my concerns seriously enough,” “Feeling that my doctor doesn’t give me clear enough directions on how to manage my diabetes,” and “Feeling that I don’t have a doctor who I can see regularly enough about my diabetes.” Variability occurred when some Veterans had not had visits within the past month and wait times for health care appointments were of varying lengths. Of note, in response to the item “Not feeling confident in my day-to-day ability to manage diabetes,” one respondent described that memory challenges affected their ability to engage in T2DM self-management.

Judgment

Although the majority of Veterans stated that responding to the overall measure and each item was easy rather than challenging, we noted challenges with three items. The question, “Feeling that my doctor doesn’t take my concerns seriously enough” was challenging for some Veterans because they had to think about the past month only rather than visits across the course of their experience of living with T2DM. In response to “Feeling that I will end up with serious long-term complications no matter what I do,” a few Veterans found it challenging to discuss their current thinking about T2DM and self-management in terms of potential future activities. In response to “Feeling that I am not sticking closely enough to a good meal plan,” one respondent indicated that conceptualizing the past month was difficult due to memory challenges.

Reaction

Veterans willingly discussed DD and their experience of living with T2DM and reported no extreme negative emotional or physical reactions while completing the DD Scale. All Veterans were aware that T2DM could have serious long-term effects. One Veteran commented that the question, “Feeling that I am often failing with my diabetes routine” elicited feelings of personal guilt. Another Veteran described feeling “gloomy” after responding to “Feeling that I will end up with serious long-term complications, no matter what I do.”

Domain Elicitation

Veterans indicated that the DD Scale adequately captured the impact of interactions with providers and sources of information and support. Veterans described their interactions with and directions received from providers regarding T2DM management. Veterans expressed that friends or family with T2DM offered support and understanding differently than those who did not have T2DM. Some Veterans noted that family members acknowledged the challenges related to self-management and living with T2DM.

When asked what aspects of DD the scale did not address, Veterans either stated verbatim what domains were missing or domains were inferred and interpreted during analysis by the research team. Thematic analysis indicated the following additional domains important to addressing DD: access to care, comorbidities, disruptions in routine, fluctuations in emotions and behaviors, lifelong nature of diabetes, mental health concerns, military as culture, physical pain, personal characteristics, physical limitations, spirituality, and stigma. Veterans explained that distress was influenced by factors such as limitations placed on provider visits by the health care system, difficulty obtaining appointments or necessary equipment for T2DM self-management, and variability in provider quality. Several Veterans described an increase in distress due to side effects of T2DM medications or the challenge of managing T2DM and other chronic illnesses simultaneously.

Many Veterans expressed frustration that “within the last month” was a short time frame to be referenced for a lifelong disease such as T2DM, noting that responses might vary according to whether they were having a “good” or “bad” day, and that behavior “within the last month” might not be representative of their overall behavior. A few Veterans described how physical pain and the physical effects of living with T2DM affected their self-management behavior and adherence with provider recommendations for their daily activities. Several Veterans also expressed that spirituality played an important role in their T2DM self-management and lightened the mental burden of living with T2DM.

Veterans described how emotions and feelings changed after health events (i.e., high blood glucose value, higher than expected A1C value), life events (i.e., amputation, death of spouse/caregiver), and over time (i.e., days, weeks, months). Several Veterans explained that mental health concerns such as PTSD, depression, and memory loss affected their self-management behaviors and experiences of DD. Some Veterans expressed that their military experience (e.g., serving in a unit, interactions with superiors) and feelings of personal responsibility (e.g., personal choices, discipline) had an impact on how they approached living with and managing T2DM. Additionally, some Veterans described instances in which they had been treated differently by friends and family due to having T2DM.

Value-added application of cognitive interview findings

Following the conclusion of analysis, the research team reviewed whether the demographic questions, quantitative measures, and qualitative semi-structured interview questions proposed for in Phases 2 and 3 (Figure 1) of the subsequent study addressed domains identified in the cognitive interviews (Table 3). The research team completed two steps: (1) identification of gaps in which domains elicited in the cognitive interviews were not addressed or not adequately addressed; and (2) conversations on how to address domains with additional quantitative measures or qualitative interview questions. After discussion, the research team achieved consensus on the addition of (1) new quantitative measures to address stigma with the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illnesses36 and physical pain using the PROMIS Pain Interference Scale37; (2) demographic questions about military experience (e.g., “When did you serve on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces?”, “How many years were you active in the military?”; (3) two qualitative interview questions to address stigma (e.g., “How does this term [stigma] describe your experience having diabetes?”) and military experience (e.g., “Is there anything about being a Veteran that influences how you take care of your diabetes?”; and (4) qualitative interview probes (e.g., “How do you overcome these barriers [related to pain]? What strategies do you use?”) to obtain information on physical pain, personal characteristics, mental health concerns, access to care, and fluctuations in emotions and behaviors. Due to concern for increased respondent burden, the research team decided against adding quantitative measures or qualitative interview questions to address spirituality.

Discussion

Diabetes distress impedes Veterans’ ability and motivation to engage in T2DM self-management behaviors; however, its impact may vary because DD is subjective and person-specific. This study’s findings affirm that DD is a salient concept for Veterans who have diabetes, as shown by how readily they engaged in the interviews, understood the interview prompts, and suggested additional domains relevant to DD and T2DM self-management. Interventions to decrease DD must be developed with an understanding of how Veterans’ experience DD in the context of T2DM self-management. To address this need for information, the research team conducted cognitive interviews to identify how Veterans with T2DM describe DD and provide responses to a commonly used DD measure, the DD Scale, and to elicit salient domains related to DD. In doing so, the research team clarified the concept of DD in Veterans with T2DM and identified how Veterans comprehend and judge the DD Scale. Overall, these data enhanced the ability to examine DD using quantitative measures and qualitative interviews in subsequent phases of this study.

Veterans found it feasible and acceptable to complete cognitive interviews via the telephone. In a process review during the first and second round of cognitive interviews, the coding team identified that Veterans experienced challenges remembering the “within the last 30 days” prompt; to address this challenge, the qualitative analyst provided additional reminders about the prompt throughout the interview. Importantly, while Veterans questioned the repetitiveness, they did not express discomfort or annoyance at being asked the same questions for each of the 17 items in the DD Scale and willingly answered each of the interview questions with minimal prompting by the interviewer. Overall, the research team’s experience supports the use of telephone-administered cognitive interviews as an appropriate measurement tool to refine understanding of DD and identify how veterans respond to the DD Scale.

Living with T2DM and engaging in T2DM self-management behaviors can be overwhelming and distressing for Veterans.16,17 Veterans reported that thinking about T2DM; self-managing T2DM (including incorporating related behaviors into daily activities), and managing DD after specific events involved time and energy. Similar to a previous study17, this study’s findings indicate that military experience influences Veterans’ perspectives on T2DM self-management, engagement with others (e.g., family, friends, health care providers), and participation in recommended T2DM self-management behaviors. Prior qualitative research indicates that individuals with DD report diabetes-related physical burden as well as health care system and comorbid conditions distress.38 Similarly, Veterans in this study described challenges to accessing appointments with providers and obtaining supplies necessary to self-manage.

Diabetes distress levels correlate with self-management behaviors such as monitoring diet, engaging with providers, and monitoring blood glucose.4,33,38–40 Veterans in this study described feeling distress with respect to provider-recommended blood glucose monitoring frequency, availability of T2DM supplies to comply with monitoring recommendations, and their actual blood glucose monitoring frequency were disconnected. Veterans expressed that their DD vacillated in response to life events, self-described “good” or “bad” days, or health-related challenges. For instance, one Veteran thought the DD Scale items were hard to answer and that they could have picked different answers for some items; another described that the Covid-19 pandemic made answering provider related-questions challenging due to the difficulty of obtaining health care appointments.

Studies benefit from using applied and actionable qualitative data to influence data collection, measurement, and intervention development.24–27 The purpose of these cognitive interviews was to ensure adequate coverage in quantitative measures and qualitative interview questions of domains and causes associated with DD in Veterans with T2DM. The findings suggest that additional domains and event-based sampling not assessed in the DD Scale are salient to understanding DD among veterans. Overall, the findings and methods may be beneficial for understanding disease-specific distress in populations that may experience T2DM and DD differently.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the interview sample was primarily composed of male Veterans from the same geographic region who received care within one VA facility. Second, the research team completed cognitive interviews during a pandemic which may have impacted Veterans experiences of DD. Future research using cognitive interviewing techniques to examine DD should be completed with additional samples such as women, transgender, and/or younger Veterans, at other health care institutions, and other geographic locations at longitudinal time points. Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths. First, the research team identified additional key domains of DD relevant to Veterans with T2DM. Second, the research team used an existing, validated measure to quantitatively assess diabetes distress and established DD domains to elicit perceptions of DD in Veterans and guide questioning in the cognitive interview.

Conclusion

Diabetes distress is a negative subjective experience that affects all aspects of living with T2DM. Cognitive interviews revealed important domains contributing to DD in Veterans that may impact how they engage in, and adhere to, self-management behaviors. With this study, the research team built upon the established literature in DD and used the DD Scale to expand understanding of DD. These cognitive interview data confirmed the usability of the DD Scale to of DD in Veterans with T2DM, and identified new areas that should be explored when DD is examined in Veterans.

Implications

Individuals with T2DM may find the continuous nature of self-management to be burdensome and stressful. Clinicians and diabetes educations should be aware of the many domains of DD and assess DD and each clinical visit. The data from this research study indicate that clinicians, diabetes educators, and researchers should account for Veteran-specific perspectives when developing and implementing self-management interventions with Veterans. The findings indicate that a Veteran’s military experience may impact the Veteran’s engagement in T2DM and suggest that studies in Veterans may benefit from using assessment tools validated in the Veteran population. Specific to researchers, this study demonstrate how cognitive interviewing can elicit actionable data to inform future quantitative and qualitative data collection in a multi-phased research study.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Donnalee Frega, PhD for editorial assistance.

Funding:

The research reported in this publication was supported by Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation grant #CIN 13–410 and VA HSR&D grants #18–234 (to AAL) and #08–027 (to HBB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the position or policy of Duke University, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:

Dr. Bosworth reports receiving research funds from Sanofi, Otsuka, Johnson and Johnson, Improved Patient Outcomes, Novo Nordisk, PhRMA Foundation as well as consulting funds from Sanofi, Otsuka, Abbott, and Novartis. Dr. Lewinski reports receiving funds from PhRMA Foundation and Otsuka. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Trial registration: NCT04587336

References

- 1.Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care 2013;36(9):2551–2558. 10.2337/dc12-2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aikens JE, Zivin K, Trivedi R, Piette JD. Diabetes self-management support using mHealth and enhanced informal caregiving. J Diabetes Complications 2014;28(2):171–176. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky WH, Mullan J. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful?: establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care 2012;35(2):259–264. 10.2337/dc11-1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adriaanse MC, Pouwer F, Dekker JM, et al. Diabetes-related symptom distress in association with glucose metabolism and comorbidity: the Hoorn Study. Diabetes Care 2008;31(12):2268–2270. 10.2337/dc08-1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baek RN, Tanenbaum ML, Gonzalez JS. Diabetes burden and diabetes distress: the buffering effect of social support. Ann Behav Med 2014;48(2):145–155. 10.1007/s12160-013-9585-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carolan M, Holman J, Ferrari M. Experiences of diabetes self‐management: A focus group study among australians with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs 2015;24(7–8):1011–1023. 10.1111/jocn.12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Glasgow RE, Arean P, Hessler D. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabet Med 2009;26(6):622–627. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02730.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faber-Wildeboer AT, van Os-Medendorp H, Kooy A, Sol BGM. Prevalence and risk factors of depression and diabetes-related emotional distress in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Educ Pract 2013;3(6):61–69. 10.5430/jnep.v3n6p61 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipscombe C, Smith KJ, Gariepy G, Schmitz N. Gender differences in the association between lifestyle behaviors and diabetes distress in a community sample of adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes 2016;8(2):269–278. 10.1111/1753-0407.12298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry E, Lockhart S, Davies M, Lindsay JR, Dempster M. Diabetes distress: understanding the hidden struggles of living with diabetes & exploring intervention strategies. Postgrad Med J 2015;91(1075):278–283. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-133017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew B-H, Vos RC, Pouwer F, Rutten GEHM. The associations between diabetes distress and self-efficacy, medication adherence, self-care activities and disease control depend on the way diabetes distress is measured: Comparing the DDS-17, DDS-2 and the PAID-5. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;142:74–84. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carper MM, Traeger L, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, Psaros C, Safren SA. The differential associations of depression and diabetes distress with quality of life domains in type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med 2014;37(3):501–510. 10.1007/s10865-013-9505-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams RE, Urosevich TG, Hoffman SN, et al. Social and Psychological Risk and Protective Factors for Veteran Well-Being: The Role of Veteran Identity and Its Implications for Intervention. Mil Behav Health 2019;7(3):304–314. 10.1080/21635781.2019.1580642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harada ND, Damron-Rodriguez J, Villa VM, et al. Veteran identity and race/ethnicity: influences on VA outpatient care utilization. Med Care 2002;40(1 Suppl):I117–128. 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthias MS, Kukla M, McGuire AB, Damush TM, Gill N, Bair MJ. Facilitators and Barriers to Participation in a Peer Support Intervention for Veterans With Chronic Pain. Clin J Pain 2016;32(6):534–540. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiNardo MM, Phares AD, Jones HE, et al. Veterans’ Experiences With Diabetes: A Qualitative Analysis. Diabetes Educ 2020;46(6):607–616. 10.1177/0145721720965498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siple J, Harris EA, Morey JM, Skaperdas E, Weinberg KL, Tuepker A. Experiences of Veterans With Diabetes From Shared Medical Appointments. Fed Pract 2015;32(5):40–45. 10.1097/nna.0000000000000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez L, Leutwyler H, Cataldo J, Kanaya A, Swislocki A, Chesla C. The Lived Experience of Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes-Related Distress. J Gerontol Nurs 2020;46(3):37–44. 10.3928/00989134-20200129-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez L, Leutwyler H, Cataldo J, Kanaya A, Swislocki A, Chesla C. Symptom Experience of Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetes-Related Distress. Nurs Res 2019;68(5):374–382. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;153(8):507–515. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. SAGE Publications; 2005. 10.4135/9781412983655 [DOI]

- 22.Willis GB, Artino AR Jr.,What Do Our Respondents Think We’re Asking? Using Cognitive Interviewing to Improve Medical Education Surveys. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5(3):353–356. 10.4300/jgme-d-13-00154.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitt A, Reimer A, Kulzer B, Haak T, Ehrmann D, Hermanns N. How to assess diabetes distress: comparison of the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID) and the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS). Diabet Med 2016;33(6):835–843. 10.1111/dme.12887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eakin JM, Gladstone B. “Value-adding” Analysis: Doing More With Qualitative Data. Int J Qual Methods 2020;19. 10.1177/1609406920949333 [DOI]

- 25.Lewinski AA, Crowley MJ, Miller C, et al. Applied Rapid Qualitative Analysis to Develop a Contextually Appropriate Intervention and Increase the Likelihood of Uptake. Med Care 2021;59. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.King HA, Doernberg SB, Miller J, et al. Patients’ Experiences with Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-Negative Bacterial Bloodstream Infections: A Qualitative Descriptive Study and Concept Elicitation Phase to Inform Measurement of Patient-Reported Quality of Life. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.King HA, Shepherd-Banigan M, Chapman JG, Bruening R, Decosimo KP, Van Houtven CH. Use of motivational techniques to enhance unpaid caregiver engagement in a tailored skills training intervention. Aging Ment Health 2020:1–8. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1855103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo A, et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res Nurs Health 2007;30(2):224–234. 10.1002/nur.20195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drennan J Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs 2003;42(1):57–63. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KM. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The qualitative report 2007;12(2):281–316. 10.46743/2160-3715/2007.1638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual Health Res 2016;26(13):1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care 2005;28(3):626–631. 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dennick K, Sturt J, Hessler D, et al. High rates of elevated diabetes distress in research populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Diab Nurs 2015;12(3):93–107. 10.1080/20573316.2016.1202497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guest GS, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications; 2018. 10.4135/9781483384436 [DOI]

- 35.Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res 2002;12(6):855–866. 10.1177/104973230201200611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molina Y, Choi SW, Cella D, Rao D. The stigma scale for chronic illnesses 8-item version (SSCI-8): development, validation and use across neurological conditions. Int J Behav Med 2013;20(3):450–460. 10.1007/s12529-012-9243-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen CX, Kroenke K, Stump TE, et al. Estimating minimally important differences for the PROMIS pain interference scales: results from 3 randomized clinical trials. Pain 2018;159(4):775–782. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanenbaum ML, Kane NS, Kenowitz J, Gonzalez JS. Diabetes distress from the patient’s perspective: Qualitative themes and treatment regimen differences among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30(6):1060–1068. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrin NE, Davies MJ, Robertson N, Snoek FJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of diabetes-specific emotional distress in people with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2017. 10.1111/dme.13448 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sturt J, Dennick K, Hessler D, Hunter BM, Oliver J, Fisher L. Effective interventions for reducing diabetes distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Diab Nurs 2015;12(2):40–55. 10.1179/2057332415Y.0000000004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]