Abstract

Objectives

To provide a comprehensive overview of interventions that support shared decision-making (SDM) for treatment modality decisions in advanced kidney disease (AKD). To provide summarised information on their content, use and reported results. To provide an overview of interventions currently under development or investigation.

Design

The JBI methodology for scoping reviews was followed. This review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Data sources

MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Emcare, PsycINFO, PROSPERO and Academic Search Premier for peer-reviewed literature. Other online databases (eg, clinicaltrials.gov, OpenGrey) for grey literature.

Eligibility for inclusion

Records in English with a study population of patients >18 years of age with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Records had to be on the subject of SDM, or explicitly mention that the intervention reported on could be used to support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently screened and selected records for data extraction. Interventions were categorised as prognostic tools (PTs), educational programmes (EPs), patient decision aids (PtDAs) or multicomponent initiatives (MIs). Interventions were subsequently categorised based on the decisions they were developed to support.

Results

One hundred forty-five interventions were identified in a total of 158 included records: 52 PTs, 51 EPs, 29 PtDAs and 13 MIs. Sixteen (n=16, 11%) were novel interventions currently under investigation. Forty-six (n=46, 35.7%) were reported to have been implemented in clinical practice. Sixty-seven (n=67, 51.9%) were evaluated for their effects on outcomes in the intended users.

Conclusion

There is no conclusive evidence on which intervention is the most efficacious in supporting SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD. There is a lot of variation in selected outcomes, and the body of evidence is largely based on observational research. In addition, the effects of these interventions on SDM are under-reported.

Keywords: nephrology, internal medicine, end stage renal failure

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The search queries for this scoping review were conducted without time period restrictions and generated comprehensive results covering all possible interventions that support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD.

Two reviewers independently used predeveloped charting and data-extraction tables to screen the literature, select records for inclusion and extract the relevant data.

The interventions identified in the included records are presented based on the decisions they were developed to support, after which information is provided on their content, format, evidence and availability.

Included records were not formally assessed for quality; potential risks of bias in the reported outcomes remain undetermined.

Interventions and/or findings from records not written in English, or records inaccessible due to subscription limitations or internet protocol address geo-blocking, are not reported.

Introduction

Over 2 million patients with kidney failure currently rely on kidney replacement therapy (KRT) to stay alive.1 This number has been estimated to double by 2030,2 and many patients with advanced kidney disease (AKD) will have to make treatment modality decisions as their kidneys deteriorate over time.

Guidelines on the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) emphasise the importance of timely kidney failure treatment modality education and decisional support as patients progress to the more advanced stages of kidney disease.3 4 Delays in the decision-making process can result in suboptimal dialysis initiation, which is associated with increased patient morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs.5

Shared decision-making (SDM) has been recognised as the preferred model to help patients with AKD understand their treatment options, and make informed decisions that align with their values and preferences.6 7 SDM requires that patients and clinicians proactively engage in a collaborative decision-making process.8–10 This process should be characterised by deliberation, during which patients become aware of their choice, understand all of their options and get to consider what matters most to them. A three-step framework has been developed to help guide this decision-making process with the following conversational steps in clinical practice: (1) team talk, (2) option talk and (3) decision talk.10 In addition, educational programmes (EPs) and decision support interventions such as patient decision aids (PtDAs) and prognostic tools (PTs) can be used to support deliberation and help patients and clinicians engage in SDM.10 Multiple efforts have been made to foster SDM across the international healthcare community,11 12 but there are still signs that patients experience a low degree of SDM,13 and efforts to incentivise SDM risk being limited to the promotion of PtDAs.14 15 A broader sense of awareness and knowledge of SDM is needed for it to become widely implemented,8 and stakeholders should share their experiences to speed up this process.16

We previously set out to write a scoping review on interventions that can support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD after we showcased a lack of a comprehensive overview of these interventions in the literature.17 We performed an additional preliminary search on the MEDLINE database prior to the conduct of this review and did not identify previous scoping reviews on the topic aligning to the same concept. We did identify a scoping review on the information available for clinicians counselling older patients with kidney failure,18 a systematic review on PtDAs developed to support SDM between dialysis and conservative care management (CCM) pathways,19 a scoping review on predialysis EPs,20 a systematic review on PTs developed to predict kidney failure21 and a Cochrane review on the effects of PtDAs in people facing treatment or screening decisions.22

We conducted this scoping review to provide clinicians, researchers and other stakeholders with one comprehensive, but digestible source of information on interventions that can support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD. An overview of interventions currently under development or investigation is also provided. We hope that this review will facilitate the future implementation of SDM in clinical practice, as well as stimulate development and research on new and effective interventions by exploring and defining knowledge gaps on the subject.

Methods

We followed the JBI methodology for scoping reviews23 and our scoping review protocol17 when we conducted this scoping review. Our objectives, research questions and methods are specified in our protocol (see online supplemental appendix 1). In addition to the protocol, we also used: (1) more detailed inclusion criteria during the screening and inclusion process and (2) the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist24 (see online supplemental appendix 2) when we completed the review. No other changes were made in the methodology described in our protocol.

bmjopen-2021-055248supp001.pdf (158.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055248supp002.pdf (4.8MB, pdf)

Objectives

In brief, our objectives were to provide:

a comprehensive overview of interventions that can support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD;

summarised information on their contents, use and reported results;

an overview of interventions currently under development or investigation.

Inclusion criteria

We searched the peer-reviewed and grey literature for records on interventions that support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD. We considered any intervention in standard care that can support deliberation and/or help patients and clinicians engage in SDM (eg, EPs, PtDAs, PTs) an SDM intervention. No time period restriction was used in an effort to be as comprehensive as possible. Records were eligible for inclusion if they were written in English, and if the study population consisted of patients >18 years of age with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Records had to be on the subject of SDM or explicitly mention that the reported interventions could be used to support SDM for treatment modality decisions in AKD. Records that reported on interventions that could clearly be used to support SDM without explicitly mentioning it were also included.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded records if:

they only reported on interventions for advance care planning;

they only reported on interventions for the withdrawal of treatment.

Search methodology

We performed a three-step search strategy as explained in the JBI methodology for scoping reviews23 and in our review protocol17 (see online supplemental appendix 1). We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Emcare, PsycINFO, PROSPERO and Academic Search Premier for peer-reviewed literature. We searched OpenGrey, researchgate.net, clinicaltrials.gov, europepmc.org, Google Scholar and websites of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Association, the Renal Physicians Association, the American Society of Nephrology, the Canadian Society of Nephrology, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, the European Renal Association—European Dialysis and Transplant Association, the Kidney Health Australia—Caring for Australians with Renal Impairment Association and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute for grey literature.

A research librarian generated the search queries (see online supplemental appendix 3). The results were uploaded in RefWorks V.2.0.

bmjopen-2021-055248supp003.pdf (163.9KB, pdf)

Record selection and data extraction

We used previous publications, the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) minimum standards criteria25 and the Standards for UNiversal reporting of patient Decision Aid evaluation (SUNDAE) checklist26 to design charting and data-extraction tables used for record selection and data extraction. Two reviewers (NE and GNdG) independently performed the process of record selection and data extraction. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with the research team (PvdN, MvdD, WJB, AMS).

We initially screened the titles and abstracts of all identified records after which the charting table was used to register records selected for full-text analysis in Microsoft Excel V.16. We then performed full-text analysis of the selected records during which a final selection was made for data extraction. We also screened the references of this selection for additional records on the subject.

Selected records were categorised based on record type and on their scope and context as mentioned by the authors and developers. We categorised the interventions we identified in these records based on whether these interventions were PTs, EPs or PtDAs. Interventions were categorised as multicomponent initiatives (MIs) when two or more of these interventions were combined to support patients with AKD in treatment modality decisions, or implement SDM in clinical practice. We subsequently categorised the identified interventions based on the decisions they were developed to support.

Extracted data included: primary author, developer, date of publication, country of origin, type of record, study population/target demographic, study aims, study methods, sample size, study arms, intervention, format and context of the intervention, contents of the intervention, patient participation in development, comparator, study outcomes, reports on outcomes of SDM, use of International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM)27 or Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG)28 outcomes, main findings, implemented in clinical practice, recruitment status, date of completion and/or publication.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates a flow chart of the screening and inclusion process. We conducted the final search query in February 2021. We identified 1512 records and included a total of 158 records. Records were excluded because they were on another subject (n=1215, 80.3%), not available (n=127, 8.4%), not in English (n=57, 3.8%), duplicates (n=34, 2.2%), reviews (n=28, 1.9%) on the wrong population (n=27, 1.8%) or protocols for completed studies (n=24, 1.6%).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow chart of screening and inclusion process.

Figure 2 illustrates the included records stratified by type, scope and context. The majority of these records are observational (n=68, 43.0%) and experimental studies (n=39, 24.7%). A smaller proportion are study protocols (n=17, 10.8%), meeting abstracts (n=16, 10.1%), mixed-methods studies (n=12, 7.6%) and websites (n=6, 3.8%). Most records report on EPs (n=62, 39.2%), followed by PTs (n=42, 26.6%), PtDAs (n=37, 23.4%) and MIs (n=17, 10.8%).

Figure 2.

Included records stratified by record type, scope and context.

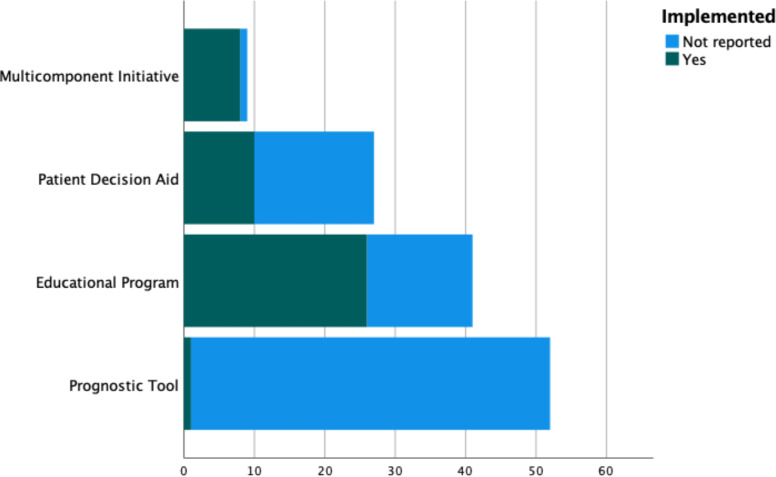

We identified 145 interventions in the included records. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of these interventions. The majority of these records are PTs (n=52, 35.9%) and EPs (n=51, 35.2%), followed by PtDAs (n=29, 20.0%) and MIs (n=13, 8.9%). Some of these interventions were only identified in meeting abstracts (n=14, 9.7%). A minority were novel interventions that we identified in study protocols (n=16, 11.0%). Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the implementation and evaluation rates of the identified interventions. About one-third of the interventions (n=46, 35.7%) were reported to have been implemented in clinical practice. About half of the interventions (n=67, 51.9%) were evaluated for their effects on outcomes in the intended users. PTs were the interventions with the least information on implementation status and were the least evaluated interventions, followed by PtDAs, EPs and MIs. Interventions were generally evaluated on health-related outcomes and on knowledge, decisional quality, communication and patient activation. Patients that were exposed to the interventions generally had better outcomes than patients that were not exposed to the interventions.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the different types of interventions.

Figure 4.

Stacked bar count of the interventions stratified by implementation status. *Interventions currently under investigation (n=16, 11.0%) are not shown here.

Figure 5.

Stacked bar count of the interventions stratified by evaluation status. *Interventions currently under investigation (n=16, 11.0%) are not shown here.

Prognostic tools

We identified 52 PTs. All PTs were identified in peer-reviewed articles.29–59

Table 1 provides an overview of the identified PTs with their characteristics and performance metrics. Table S1 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on the identified PTs (eg, sources for publicly available PTs). Nineteen PTs predict the risk of progression to kidney failure (no. 1–19) and help patients and clinicians decide whether or not patients should start with preparations for kidney failure. One PT also predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease and death (no. 19). Twenty-eight PTs predict the risk of death after starting dialysis (no. 20–47) and help patients and clinicians decide whether or not patients should choose to start dialysis. Two PTs predicts the risk of death after starting CCM (no. 48, 49) and help patients and clinicians decide whether or not patients should choose to start CCM. One PT predicts and compares the risk of death after starting dialysis or transplantation (no. 50) and helps patients and clinicians decide between dialysis and transplantation options. One PT predicts the risk of deceased donor kidney graft failure (no. 51) and helps patients and clinicians decide whether or not patients should accept a deceased donor kidney transplantation offer. One PT predicts the risk of living donor kidney graft failure (no. 52) and helps patients and clinicians decide whether or not patients should accept a living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) offer.

Table 1.

Overview of the identified PTs, their characteristics and performance metrics

| PT | Prediction* | Format | Population† | Validation | Discrimination‡ | Calibration§ | External validation | Implemented | Evaluated |

| Start preparation for kidney failure? | |||||||||

| No. 1: Johnson prognostic score | 5-year risk of kidney failure | Point-based scoring system | Patients with CKD stage 3–4 | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.89 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p>0.99) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 2: 4-variable kidney failure risk equation |

|

|

Patients with CKD stage 3–5 | External sample |

|

Calibration plot and Nam and D’Agostino statistic 3-year risk of kidney failure (32) | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 3: 8-variable kidney failure risk equation |

|

|

|

Calibration plot and Nam and D’Agostino statistic 3-year risk of kidney failure (19) | Yes | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 4: Drawz prognostic model | 1-year risk of kidney failure | Formula | Patients >65 years of age with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|

|

Calibration plot | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 5: Marks prognostic model |

5-year risk of kidney failure | Formula | Patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

External sample | C-statistic=0.94 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic (4.6) | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 6: Norouzi prognostic model |

|

Computer software package | Patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

Comparison of performance in training and testing datasets |

|

|

No | Not reported | No |

| No. 7: Tangri dynamic prognostic model | Time to kidney failure (dynamic) | Formula | Patients with CKD stage 3–5 |

|

C-statistic=0.91 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic (<20) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 8: Schroeder prognostic model | 5-year risk of kidney failure | Formula | Patients with CKD stage 3–4 |

|

C-statistic=0.95 | Calibration plot | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 9: 2-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula | Patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|

|

|

No | Not reported | No |

| No. 10: 3-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 11: 4-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 12: 5-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 13: 6-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 14: 7-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 15: 8-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 16: 9-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 17: 10-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 18: 11-variable CKD-JAC clinical prediction model |

3-year risk of kidney failure | Formula |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 19: CKD-PC risk |

|

|

Patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

External sample | C-statistic 2-year risk of kidney failure=0.81 | Calibration plot 2-year risk of kidney failure | No | Not reported | No |

| Start with dialysis or not? | |||||||||

| No. 20: Foley prognostic score | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients on dialysis | No | No | No | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 21: Barret prognostic score | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients on dialysis (PD/HD) | No | No | No | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 22: Geddes multivariate prognostic model |

|

Formula | Patients on KRT | Split sample |

|

No | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 23: Geddes self-learning rule-based model |

|

Computer software package |

|

No | No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 24: Mauri prognostic model | Death within 1 year of HD initiation | Formula | Patients on HD | Split sample | C-statistic=0.78 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.49) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 25: 6-month REIN score |

Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients >75 years of age on dialysis | Split sample | C-statistic=0.70 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.93) | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 26: 3-month REIN score |

Death within 3 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients >75 years of age on dialysis | Split sample | C-statistic=0.75 | No | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 27: Dusseux prognostic score | Death within 3 years of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | External sample | C-statistic=0.71 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.20) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 28: Weiss prognostic score (age 65–79 years) |

|

Point-based scoring system | Patients >70 years of age on dialysis (PD/HD) | Bootstrapping |

|

|

No | Not reported | No |

| No. 29: Weiss prognostic score (age >80 years) |

|

Point-based scoring system |

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 30: 7-variable Thamer prognostic score |

|

Point-based scoring system | Patients >67 years of age on dialysis | Split sample |

|

No | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 31: 14-variable Thamer prognostic score |

|

Point-based scoring system |

|

|

Yes | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 32: Doi prognostic score |

Death within 1 year of HD initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients on HD | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.83 | Calibration plot | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 33: Wick prognostic score | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients >65 years of age on dialysis (PD/HD) | Cross-validation | C-statistic=0.72 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.20) | Yes | Not reported | No |

| No. 34: Chen prognostic score | Death within 5 years of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients >70 years of age on dialysis (PD/HD) |

|

|

No | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 35: Haapio prognostic model | Death within 1 year of dialysis initiation | Formula | Patients on dialysis (PD/HD) | External sample | C-statistic=0.76 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.041) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 36: Haapio prognostic model | Death within 2 years of dialysis initiation | Formula | C-statistic=0.74 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.015) | No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 37: Schmidt prognostic model | Death within 1 year | Formula | Patients with CKD stage 4–5 | External sample | C-statistic=0.74 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.46) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 38: Dialysis score (for patients with eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

Death within 1 year of dialysis initiation |

|

Patients on dialysis |

|

|

|

No | Not reported | No |

| No. 39: dialysis score (for patients with eGFR >15 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

Death within 1 year of dialysis initiation |

|

|

|

No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 40: Lin random forest cost prediction model |

Medical costs 1 year after dialysis initiation | Computer software package | Patients >65 years of age on dialysis | Comparison of performance in training and testing datasets | Mean absolute error=0.51 | No | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 41: Lin random forest mortality prediction model |

Death within 1 year after dialysis initiation | Computer software package | C-statistic=0.66 | No | No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 42: Lin artificial neural network model for costs |

Medical costs 1 year after dialysis initiation | Computer software package | Mean absolute error=1.85 | No | No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 43: Lin artificial neural network model for mortality |

Death within 1 year after dialysis initiation | Computer software package | C-statistic=0.68 | No | No | Not reported | No | ||

| No. 44: Yoshida clinical nomogram |

|

Nomogram | Patients >80 years of age on dialysis | Bootstrapping |

|

|

No | Not reported | No |

| No. 45: Santos prognostic score | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | Point-based scoring system | Patients >65 years of age on dialysis (PD/HD) | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.79 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.58) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 46: Ramspek basic dialysis prognostic model | Death within 2 years of dialysis initiation | Formula | Patients >70 years of age with CKD stage 4–5 | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.68 | Calibration plot and calibration-in-the-large (32.5% vs 32.6%) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 47: Ramspek extended dialysis prognostic model | Death within 2 years of dialysis initiation | Formula | C-statistic=0.75 | Calibration plot and calibration-in-the-large (32.5% vs 32.6%) | No | Not reported | No | ||

| Start with CCM or not? | |||||||||

| No. 48: Ramspek basic CCM prognostic model | Death within 2 years of conservative care initiation | Formula | Patients >70 years of age with CKD stage 4–5 | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.68 | Calibration plot and calibration-in-the-large (56.3% vs 56.5%) | No | Not reported | No |

| No. 49: Ramspek extended CCM prognostic model | Death within 2 years of conservative care initiation | Formula | C-statistic=0.73 | Calibration plot and calibration-in-the-large (56.3% vs 56.3%) | No | Not reported | No | ||

| Transplantation or dialysis? | |||||||||

| No. 50: iChoose Kidney |

|

|

|

Split sample |

|

|

No | Yes | Yes |

| Accept or decline DDKT offer? | |||||||||

| No. 51: Kidney Donor Risk Index | Risk of deceased donor kidney graft failure |

|

DDKT recipients | Cross-validation | C-statistic=0.62 | No | Yes | Not reported | No |

| Accept or decline LDKT offer? | |||||||||

| No. 52: Living Kidney Donor Risk Index | Risk of living donor kidney graft failure |

|

LDKT recipients | Bootstrapping | C-statistic=0.59 | No | Yes | Not reported | No |

*Prediction formulated as reported in identified records.

†Population formulated as reported in identified records.

‡Discrimination describes how accurately a tool identifies a high probability of events in patients with the outcome of interest and is expressed as a slope or C-statistic. A C-statistic of 0.5 represents no predictive discrimination and a C-statistic of 1 represents perfect predictive discrimination. When the C-statistic is >0.7, a score has acceptable discriminatory power.

§Calibration describes the agreement between the observed and predicted outcomes and is generally expressed with a calibration plot, a calibration slope, as calibration-in-the-large or a goodness-of-fit test. A calibration plot compares the predicted risks with observed risks within subgroups of patients and provides the most information on calibration accuracy.

CCM, conservative care management; CKD, chronic kidney disease; C-statistic, concordance statistic; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD, haemodialysis; JAC, Japan cohort; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LDKT, living donor kidney transplantation; n.a., not applicable; NPV, negative predictive value; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PPV, positive predictive value; PTs, prognostic tools; REIN, Renal Epidemiology and Information Network.

bmjopen-2021-055248supp004.pdf (478.9KB, pdf)

A relatively large proportion (n=19, 36,5%) of the identified PTs were developed to be used in elderly patients with AKD (no. 4, 25, 26, 28–31, 33, 34, 40–49). The remaining PTs can be used in the general population of patients with AKD.

The majority of PTs (n=32, 61.5%) are publicly available as formulas (no. 2–5, 7–19, 22, 24, 35–39, 46–52), eight of which (no. 2, 3, 19, 38, 39, 50–52) can be used on interactive websites. One of these PTs (no. 50) has been designed as a PtDA. Point-based scoring systems (no. 1, 20, 21, 25–34, 45) and nomograms (no. 44) were also used, although less frequently (n=14, 26.9%, n=1, 1.9%). A minority of PTs (n=6, 11.5%) are not publicly available (no. 6, 23, 40–43) and depend on computer software to be used.

Not all PTs were completely validated (assessed for performance) during development. About a quarter (n=11, 21.2%) were not evaluated on calibration outcomes (no. 22, 23, 26, 30, 34, 40–43, 51, 52), and some (n=2, 3.8%) were not validated at all (no. 20, 21). Most of them (n=37, 71,2%) were developed and validated with the same cohort of patients (no. 1, 6, 7, 9–18, 22–26, 28–33, 40–52). A quarter (n=13, 25.0%) were developed and validated with different patient cohorts (no. 2–5, 8, 19, 27, 34–39). The discriminatory power of the PTs was generally acceptable, one-fourth (n=13, 25.0%) had C-statistics below 0.7 on all, or a subset of, predictions (no. 9, 28–30, 34, 39, 41, 43, 46, 48, 50–52). The remaining PTs had better C-statistics.

Table 2 provides an overview of the PTs (no. 2–5, 19, 20, 25, 26, 30, 33, 51, 52) that were externally validated in independent external validation studies.31 32 46 55 60–69 Table S2 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on these external validation studies. One PT (no. 2) was externally validated in six different studies,32 60–63 67 two other PTs (no. 3, 25) were externally validated in three31 62 67 and four different studies,46 55 64 66 respectively. The other nine (no. 4, 5, 19, 20, 26, 30, 33, 51, 52) were externally validated less frequently.

Table 2.

Overview of PTs validated in independent external validation studies

| PT | Source | Population* | Prediction† | Discrimination‡ | Calibration§ |

| Start preparation for kidney failure? | |||||

| No. 2 | Retrospective cohort study60 | African-American patients with an eGFR between 20 and 65 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|

|

No |

| No. 2 | Retrospective cohort study61 | Patients with CKD stage 2–5 | 3-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.91 | Calibration plot |

| No. 2 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study32 | Patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 5-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.95 | Calibration plot |

| No. 2 | Retrospective cohort study62 | Patients with CKD stage 3–5 | 5-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.88 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.05) |

| No. 3 | 5-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.89 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.03) | ||

| No. 2 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study67 | Patients with CKD stage 3–5 |

|

|

|

| No. 3 |

|

|

|

||

| No. 3 | Retrospective cohort study31 | Patients >65 years of age with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1-year risk of kidney failure |

|

No |

| No. 2 | Multicentre prospective cohort study63 | Patients >75 years of age with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|

|

|

| No. 4 | 1-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.66 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.47) | ||

| No. 5 | 5-year risk of kidney failure | C-statistic=0.65 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.72) | ||

| No. 19 |

|

|

|

||

| Start with dialysis or not? | |||||

| No. 25 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study64 | Patients >67 years of age on dialysis | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.63 | No |

| No. 25 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study46 | Patients >67 years of age on dialysis | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation |

|

|

| No. 25 | Retrospective cohort study55 | Patients >65 years of age on dialysis (PD/HD) | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.70 | No |

| No. 26 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study65 | Patients on dialysis |

|

|

No |

| No. 20 | Retrospective cohort study66 | Patients >75 years of age on dialysis | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.67 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.004) |

| No. 25 | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.61 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.45) | ||

| No. 26 | Death within 3 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.62 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.03) | ||

| No. 30 |

|

|

|

||

| No. 33 | Death within 6 months of dialysis initiation | C-statistic=0.57 | Calibration plot and Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.43) | ||

| Accept or decline DDKT offer? | |||||

| No. 51 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study68 | DDKT recipients |

|

|

|

| Accept or decline LDKT offer? | |||||

| No. 52 | Retrospective cohort study69 | LDKT recipients | Risk of living donor kidney graft failure | C-statistic=0.55 | Calibration plot |

*Population formulated as reported in identified records.

†Prediction formulated as reported in identified records.

‡Discrimination describes how accurately a tool identifies a high probability of events in patients with the outcome of interest and is expressed as a slope or C-statistic. A C-statistic of 0.5 represents no predictive discrimination and a C-statistic of 1 represents perfect predictive discrimination. When the C-statistic is >0.7, a score has acceptable discriminatory power.

§Calibration describes the agreement between the observed and predicted outcomes and is generally expressed with a calibration plot, a calibration slope, as calibration-in-the-large or a goodness-of-fit test. A calibration plot compares the predicted risks with observed risks within subgroups of patients and provides the most information on calibration accuracy.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; C-statistic, concordance statistic; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD, haemodialysis; LDKT, living donor kidney transplantation; n.a., not applicable; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTs, prognostic tools.

The majority of the PTs (n=10, 83.3%) were externally validated in different patient populations (no. 2, 3, 4, 5, 19, 20, 25, 26, 30, 33) than the ones they were developed for. Three PTs had poor discriminatory power in these patient populations (no.2, 30, 33), with C-statistics between 0.5 and 0.6.63 66 Performance metrics were generally comparable between developmental and external validation studies when similar patient populations were used (see tables 1 and 2). Only one PT (no. 50) was reported to have been implemented in clinical practice. This PT was designed as a PtDA57 and is in that regard the only PT that has been evaluated for its effects on outcomes in the intended users.70

Educational programmes

We identified 41 EPs (excluding ten currently under investigation). Thirty-five were identified in peer-reviewed articles.71–104 Six were identified in meeting abstracts found in the grey literature.105–110

Table 3 provides an overview of the identified EPs and their characteristics. Table S3 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on the identified EPs (eg, sources for publicly available EPs). One EP was developed to promote peritoneal dialysis (PD) and helps patients choose whether to start with PD or not (no. 1). Eleven EPs help patients choose between dialysis options (no. 2–11), with two promoting a particular treatment modality (no. 5, 11). Ten help patients choose between dialysis and transplantation options (no. 12–21), with two promoting a particular treatment modality (no. 13, 14). Seven EPs were developed to promote LDKT (no. 2–28) and help patients decide whether to pursue LDKT or not. Two EPs help patients choose between dialysis and CCM options (no. 29, 30). Seven help patients choose between transplantation, dialysis and CCM options (no. 31–37), one of which promotes home therapy modalities (no. 37). Four EPs help patients choose between transplantation options (no. 38–41).

Table 3.

Overview of the identified EPs and their characteristics

| EP | Format | Treatment options* | Promotes treatment modality | Coaching | Patient participation in development | Reading level | Implemented | Evaluated |

| Start PD or not? | ||||||||

| No. 1: customised video counselling |

1 video (32 min) | PD | PD | No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| What type of dialysis modality? | ||||||||

| No. 2: Toronto Hospital multidisciplinary predialysis programme |

|

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 3: Karolinska Hospital predialysis patient education |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 4: Birmingham Heartlands Hospital predialysis counselling |

|

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 5: Two-phase educational intervention |

|

|

Self-care dialysis modalities | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 6: dialysis education |

Multiple outpatient consultations with clinicians (n.a.) | Dialysis | No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 7: multimedia interactive patient education |

1 DVD (n.a.) |

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 8: comprehensive PDEP |

Multiple sessions of individual education by nephrologists and experienced nurse (n.a.) |

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 9: physician-led CKD education programme |

1 session of group education (n.a.) | Dialysis | No | No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 10: patient-driven video educational tool |

1 video (50 min) |

|

No | No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 11: King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital PDEP |

Multiple outpatient consultations with clinicians (n.a.) |

|

PD | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| Transplantation or dialysis? | ||||||||

| No. 12: Cliniques Universitaires St. Luc PDEP |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 13: RTN |

|

|

Independent KRT modalities | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 14: In-hospital CKD education programme |

|

|

Home dialysis modalities | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 15: multidisciplinary predialysis education |

|

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 16: Faculty of Medicine Ataturk University PDEP |

|

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 17: Information on Dialysis (INDIAL) |

2 sessions of group education (4 hours total) |

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 18: renal school |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 19: kidney team at home |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 20: Infórmate Acerca de la Donación de Riñón en Vida (Infórmate) |

Website |

|

No | No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 21: Nissan Tamagawa Hospital multidisciplinary care |

4 outpatient consultations with clinicians (n.a.) |

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| Pursue LDKT or not? | ||||||||

| No. 22: home-based educational intervention |

|

LDKT | LDKT | Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 23: promoting live donor kidney transplantation |

|

LDKT | LDKT | Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 24: increasing the pursuit of living kidney donation |

|

|

LDKT | No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 25: Talking about Live Kidney Donation |

|

LDKT | LDKT | Yes | No | Moderate to low health literacy | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 26: Living About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing |

|

LDKT | LDKT | No | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 27: Hispanic Kidney Transplant Programme |

|

|

LDKT | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 28: patient navigator and education programme |

Multiple sessions of individual education with patient navigators (n.a.) |

|

LDKT | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| Dialysis or CCM? | ||||||||

| No. 29: St. Paul’s Hospital multidisciplinary predialysis clinic |

|

|

No | No | n.a. | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 30: Birmingham Heartlands Hospital predialysis education |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| Transplantation, dialysis or CCM? | ||||||||

| No. 31: Acute Start Dialysis Education and Support |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No.32: Treatment Options Programme (TOP) |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No.33: University of Michigan multidisciplinary and peer mentor education |

|

|

n.a. | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | No |

| No. 34: comprehensive predialysis education |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 35: digital modality decision programme |

Interactive website |

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 36: options class |

1 session of individual education with a renal nurse (1–2 hours) |

|

No | No | No | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 37 individual chronic kidney disease education |

1 session of individual education with various experts (n.a.) |

|

Home therapy modalities | No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| What type of transplantation? | ||||||||

| No. 38: communicating about choices in transplantation |

|

|

No | No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 39: explore transplant (ET) |

|

|

No | Yes | Yes | Low health literacy | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 40: ET at home |

|

|

No | Yes | Yes | Low health literacy | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 41: your path to transplant (YPT) |

|

|

No | Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

*Treatment options formulated as reported in the identified records.

APD, ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CCM, conservative care management; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; EPs, educational programmes; HD, haemodialysis; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LDKT, living donor kidney transplantation; n.a., not available; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PDEP, predialysis education programme; RTN, renal triage nurse.

Most EPs were developed for the general population of patients with AKD, however some (n=5, 12.2%) were specifically developed for Hispanic and African-American patients (no. 20, 26–28, 40), and some (n=3, 7.3%) were specifically developed for suboptimal dialysis initiation patients (no. 13, 14, 31).

About one-third of the EPs (n=14, 34.1%) consist of a single medium format (no. 1, 6–11, 17, 20, 21, 28, 35–37). The remaining programmes consist of a combination of different medium formats. About half of the EPs (n=20, 48.8%) use coaches to guide patients through the programme (no. 3, 12–14, 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 30–35, 39–41). A minority (n=7, 17.0%) were developed with the input of patients (no. 1, 10, 20, 26, 38–40) and even less (n=3, 7.3%) describe a reading level (no. 25, 39, 40). Only a few EPs (n=2, 4.9%) are publicly available (no. 20, 32).

More than half of the EPs (n=26, 63.4%) were reported to have been implemented in clinical practice (no. 2–6, 8, 11–19, 21, 26–34, 36). All but one (no. 33) have been evaluated for their effects on outcomes in the intended users.

Table 4 provides an overview of the studies71–86 88–118 that evaluated the identified EPs. Table S4 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on these studies. The majority of these EPs (n=19, 47.5%) were evaluated in experimental studies (no.1, 3, 5, 7, 16, 19, 20, 22–27, 29, 35, 38–41), more than half of which (n=14, 73,7%) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs).71 74 86 88 90–92 101–103 111–113 115 Less (n=16, 40.0%) were evaluated in observational studies (no.2, 4, 6, 11–15, 17, 18, 21, 28, 30–32, 34), a minority of which (n=4, 25.0%) were prospective cohort studies.76 94 95 117 Five (n=5, 12.5%) EPs (no.8–10, 36, 37) were evaluated in studies presented in meeting abstracts.105–107 109 110

Table 4.

Overview of studies evaluating the identified EPs

| EP | Source | Population* | Sample size | Primary outcome(s)† | Secondary outcome(s)† | Main findings‡ |

| Start PD or not? | ||||||

| No. 1 | RCT74 | Patients with CKD stage 5 | Total=120

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: PD acceptance rate, PD catheter insertion on schedule |

|

There were no significant differences in PD acceptance rate, PD catheter insertion on schedule, patient knowledge or confidence in PD between the intervention and control groups |

| What type of dialysis modality? | ||||||

| No. 2 | Retrospective cohort study72 | Predialysis patients | Total=141 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, initiation rates of dialysis access prior to the first dialysis session, rates of inpatient dialysis start | Post-intervention: length of in-hospital stay after dialysis initiation |

|

| No. 3 | Non-randomised controlled study75 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=56

|

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 4 | Prospective cohort study76 | Patients on KRT | Total=33

|

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 5 | RCT71 | Patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=70

|

|

|

|

| RCT111 | Patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=70

|

|

n.a. |

|

|

| No. 6 | Multicentre retrospective cohort study77 | Patients on maintenance dialysis | Total=1504 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, duration and type of nephrological care, number of medical visits in the year before dialysis start, education on dialysis modality options and CKD, time between education, permanent access creation and dialysis start, type of access for dialysis modality | n.a. |

|

| No. 7 | Quasi-experimental study78 | Patients with an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=60

|

|

n.a. | There were significant differences in the improvement of knowledge (p<0.001), uncertainty (p<0.001) and decisional regret (p<0.001) between the intervention and control groups |

| No. 8 | Meeting abstract of retrospective cohort study105 | Patients on KRT | Total=209 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, selection of dialysis modality, parameters of treatment outcome | n.a. |

|

| No. 9 | Meeting abstract of retrospective cohort study106 | Patients on dialysis | Total=1294 | Post-intervention: Patient and clinical characteristics, participation in the educational programme, differences in treatment outcomes based on educational programme attendance | n.a. |

|

| No. 10 | Meeting abstract of qualitative study107 |

|

Total=6 | Patient reported themes of experiences to be included in a video-educational tool, provider feedback on the tool, patient feedback on the tool | n.a. |

|

| No. 11 | Retrospective cohort study73 | Patients on dialysis | Total=213

|

Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, choice of dialysis modality | n.a. |

|

| Transplantation or dialysis? | ||||||

| No. 12 | Retrospective cohort study79 | Patients on KRT | Total=242

|

Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, influence of ESKD aetiology and age on the distribution of KRT modalities, the timing of dialysis initiation, the effects of late referral on the KRT modalities | n.a. |

|

| No. 13 | Retrospective cohort study81 | Suboptimal HD start patients | Total=178

|

180 days post-intervention: the likelihood of patients switching to independent KRT therapy | 180 days post-intervention/control: likelihood of independent KRT therapy after RTN education |

|

| No. 14 | Retrospective cohort study80 | Acute start dialysis patients | Total=228 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, chosen dialysis modality at hospital discharge, comparison of patient characteristics between those choosing in-centre HD and HD home | n.a. |

|

| No. 15 | Retrospective cohort study82 | Patients with an eGFR <40 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=1218

|

Post-intervention: all-cause mortality, progression to ESKD, KRT initiation, cardiovascular outcomes, infectious events, hospitalisation rates | n.a. |

|

| No. 16 | Non-randomised controlled study83 | Kidney transplantation recipients | Total=88

|

Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, pre-emptive LDKT rates | n.a. |

|

| No. 17 | Retrospective cohort study84 | Patients with an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=227

|

Post-intervention: annual PD and HD incidence rates | n.a. | 54,3% of patients that received the intervention started with PD as compared with 28% of patients that did receive the intervention (p<0.001) |

| No. 18 | Retrospective cohort study85 | Patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=234

|

Post-intervention: emergency dialysis rates, acute catheter insertion rates, hospital length of stay, complication rates | n.a. |

|

| No. 19 | RCT86 |

|

Total=409 (163 patients)

|

Pre-intervention and 3 days post-intervention/control: knowledge, risk perception, self-efficacy, attitude towards communication, communication on KRT, willingness to accept a LDKT | Up to 6 months post-intervention/control: amount of living donor inquiries, mount of living donor evaluations, amount of actual LDKTs |

|

| RCT with cross-over113 |

|

Total=390 (80 patients)

|

Pre-intervention, 4 and 8 weeks post-intervention/control: knowledge, frequency of communication on each KRT option in the past 4 weeks, the extent to which the participant indented to communicate about each KRT option with loves ones or the patient |

|

|

|

| No. 20 | Multicentre pre-post study114 | Hispanic kidney transplantation candidates | Total=63 |

|

n.a. |

|

| Multicentre RCT115 |

|

Total=282 (112 patients)

|

|

n.a. |

|

|

| No. 21 | Retrospective cohort study104 | Patients with CKD | Total=112

|

Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, annual decreases in eGFR values, time to dialysis initiation, urgent dialysis initiation rate, PD selection rates and PD retention rates | n.a. |

|

| Pursue LDKT or not? | ||||||

| No. 22 | RCT88 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=132

|

Post-intervention/control: the proportion of patients with living donor inquiries, living donor evaluations and LDKT rates | Pre-intervention/control: LDKT knowledge, willingness and concerns regarding LDKT, the number of educated potential donors |

|

| RCT112 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=132

|

1 year post-intervention/control: the proportion of patients with living donor inquiries, living donor evaluations and LDKT rates in both black and white patients |

|

|

|

| No. 23 | Non-randomised controlled study89 | HD patients eligible for kidney transplantation | Total=214

|

Pre-intervention and 1 week post-intervention/control: readiness to consider LDKT, readiness to talk about LDKT with friend or family, readiness to ask friends and family to donate a kidney | n.a. |

|

| No. 24 | RCT90 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=100

|

3 months post-intervention/control: whether a potential living kidney donor contacted the living donor programme on behalf of a patient |

|

|

| No. 25 | Multicentre RCT91 | Patients with CKD stage 3–5 | Total=130

|

1–3 and 6 months post-intervention/control: self-reported achievement of at least one of the following five steps: discussing LDKT with a family member, discussing LDKT with their physician, initiating the clinical evaluation for LDKT recipients, completing the clinical evaluation for LDKT recipients and identifying a potential live kidney donor |

|

|

| No. 26 | RCT92 | African-American kidney transplant candidates | Total=268

|

Pre-intervention, immediately and 6 months post-intervention/control: knowledge of LDKT, willingness to talk to family members about LDKT, perceived benefits of LDKT | n.a. |

|

| No. 27 | Pre-post study93 |

|

Total=113 |

|

n.a. |

|

| Pre-post study116 |

|

Total=1286

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, waiting lists as a proxy for patient referrals, the ratio of Hispanic to non-Hispanic white LDKTs and DDKTs | n.a. |

|

|

| No. 28 | Prospective cohort study94 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=5571 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, total potential living donors per patient, likelihood of receiving a DDKT or LDKT | n.a. |

|

| Dialysis or CCM? | ||||||

| No. 29 | Non-randomised controlled study72 | Predialysis patients | Total=76

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: number of urgent versus elective dialysis starts, percentage of patients training as outpatients, the number of admissions and hospital days during the first of dialysis | Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: patient and clinical characteristics |

|

| No.30 | Prospective cohort study95 | Patients with an eGFR <25 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=118 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, patient reported factors affecting modality choice, attendance rates at patient education day | n.a. |

|

| Transplantation, dialysis or CCM? | ||||||

| No. 31 | Mixed methods: opinion and retrospective cohort study97 | Acute start dialysis patients | Total=100 | Post-intervention: treatment modality decisions | n.a. | 44 patients decided to pursue a home dialysis modality after the intervention |

| No. 32 | Quality improvement report96 | Patients with CKD stage 3–4 | Total=30 217

|

Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, patient dialysis modality selection, vascular access type, mortality rates in the first 90 days of dialysis | n.a. |

|

| Quality improvement report118 | Patients with CKD stage 3 and 4 | Total=73.500 | Post-intervention: patient dialysis modality selection, vascular access type | n.a. |

|

|

| No. 34 | Retrospective cohort study98 | Patients with CKD stage 4–5 | Total=108 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, patient choice of dialysis modality, potential determinants for the choice of KRT modality | n.a. |

|

| Prospective cohort study117 | Patients with CKD stage 4–5 | Total=177 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, patient choice of dialysis modality, potential determinants for the choice of KRT modality | n.a. |

|

|

| No. 35 | Pre-post study99 | Patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=25 |

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 36 | Meeting abstract of retrospective cohort study109 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=460 | Post-intervention: patient and clinical characteristics, dialysis modality selection after options class, dialysis modality initiation after options class | n.a. |

|

| No. 37 | Meeting abstract of pre-post study110 | Patients with CKD | Total=39

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: self-assessed level of comprehension of KRT modalities | Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: utilisation of written resources provided, an assessment of the factors that influence participants’ selection on their choice of modality |

|

| What type of transplantation? | ||||||

| No. 38 | Non-randomised controlled study100 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=20

|

Pre-intervention, immediately and 1 month post-intervention/control: self-reported discussion of LDKT and/or DDKT |

|

|

| No. 39 | Multicentre RCT101 | Patients on dialysis | Total=253

|

Pre-intervention and 1 month post-intervention/control: patients’ readiness to allow someone to be a living donor, patients’ readiness to get on the DDKT wait list |

|

|

| No. 40 | Multicentre RCT102 | Black and low-income patients on dialysis | Total=561

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: DDKT and LDKT knowledge |

|

|

| No. 41 | RCT103 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=802

|

Pre-intervention, 4 and 8 months post-intervention/control: patients’ readiness to pursue DDKT and LDKT |

|

|

*Population formulated as reported in the identified records.

†Outcomes formulated as reported in the identified records.

‡Main findings formulated as reported in the identified records.

ACTS, living about choices in transplantation and sharing; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CCM, conservative care management; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COACH, communicating about choices in transplantation; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EPs, educational programmes; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HD, Haemodialysis; HKTP, Hispanic kidney transplant programme; KRT, Kidney replacement therapy; LDKT, Living donor kidney transplantation; MDC, multidisciplinary care; n.a., not applicable; PD, Peritoneal dialysis; PDEP, Predialysis education programme; RCT, Randomised controlled trial; SDM, shared decision-making; TALK, talking about live kidney donation; TOP, treatment options programme.

EPs were generally evaluated for their effects on health-related outcomes and on knowledge, communication and patient activation. None of the EPs were evaluated for their effects on SDM. Thirteen (n=13, 31.7%) EPs (no.1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 21, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40, 41) were evaluated in studies published after the standardised outcome sets for CKD, dialysis and transplantation were published by ICHOM and SONG. None of these EPs were evaluated with these outcomes. EPs that promote particular treatment modalities (no.1, 5, 11, 13, 14, 22–28) appear to increase the number of patients planning to start with the promoted modalities (see table 4). Patients exposed to EPs generally had more favourable health-related outcomes than patients that were not exposed to EPs (see table 4). They were also more knowledgeable about their treatment options, better equipped to communicate about their treatment options and more active in choosing and requesting a preferred treatment modality (see table 4).

Patient decision aids

We identified 27 PtDAs (excluding two currently under investigation). Fourteen were identified in peer-reviewed articles.57 119–131 Thirteen were identified in the grey literature,132–141 seven of which in meeting abstracts.132–135

Table 5 provides an overview of the identified PtDAs and their characteristics. Table S5 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on the identified PtDAs (eg, sources for publicly available PtDAs). One PtDA helps patients choose whether or not they should start with dialysis (no. 1) and one helps them decide when to start with dialysis if they decide to do so (no. 2). Nine help patients choose between dialysis options (no. 3–11) and five help them choose between transplantation and dialysis options (no. 12–16). One PtDA helps patients decide whether or not they want to accept an infectious risk donor kidney donation offer (no. 17). Four help patients choose between dialysis and CCM options (no. 18–21). Six help patients choose between transplantation, dialysis and CCM options (no. 22–27).

Table 5.

Overview of the identified PtDAs and their characteristics

| PtDA | Format | Treatment options* | Values-clarification/preference elicitation exercise(s) | Patent participation in development | Reading level | Implemented | Evaluated |

| Start with dialysis or not? | |||||||

| No. 1: Kidney failure - should I start dialysis? |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| When to start dialysis? | |||||||

| No. 2: Kidney failure—when should I start dialysis? |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| What type of dialysis modality? | |||||||

| No. 3: My life, my dialysis choice |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No. 4: Kidney failure— what type of dialysis should I have? |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No. 5: Yorkshire Dialysis Decision Aid (YODDA) - web |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | Yes | Eighth to ninth grade level | Not reported | No |

| No. 6: YODDA - booklet |

PDF document (48 pages) |

|

Yes | Yes | Eighth to ninth grade level | Yes | Yes |

| No. 7: Shared end-stage renal patients decision-making (SHERPA-DM) option grid |

PDF document (1 page) |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 8: SHERPA-DM decision aid |

PDF document (4 pages) |

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 9: Dialysis choice |

|

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 10: The dialysis guide |

Interactive application |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 11: Choosing dialysis —empowering patients on choices for renal replacement therapy (EPOCH-RRT) decision aid |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| Transplantation or dialysis? | |||||||

| No. 12: Kidney transplant P3 (patient provider partnerships) |

Interactive website |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No. 13: iChoose kidney | Interactive website |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 14: My transplant coach |

Interactive website |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 15: To choose the treatment that suits you for kidney disease |

PDF document (16 pages) |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Yes | No |

| No. 16: Option grid: KRT |

PDF document (1 page) |

|

No | Yes | Common European framework of reference level B1 | Yes | Yes |

| Accept or decline IRD kidney offer? | |||||||

| No. 17: Inform me: about increased risk donor kidneys |

Interactive website | DDKT | No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| Dialysis or CCM? | |||||||

| No. 18: OPTIONS tool |

|

|

Yes | No | Eighth grade level | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 19: The conservative kidney management decision aid |

Interactive website |

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No. 20: Yorkshire dialysis and conservative care decision aid |

PDF document (28 pages) |

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No.21: Supportive kidney care video decision aid |

1 video (11.5 min) |

|

No | No | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| Transplantation, dialysis or CCM? | |||||||

| No. 22: The option grid - chronic kidney disease treatment options |

PDF document (1 page) |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 23: Patient decision aid—kidney failure treatment options |

PDF document (28 pages) |

|

Yes | No | n.a. | Not reported | No |

| No.24: Providing resources to enhance African-American patients' readiness to make decisions about kidney disease decision aid |

|

|

Yes | Yes | Fourth to sixth grade level | Not reported | Yes |

| No. 25: My kidneys, my choice |

|

|

Yes | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No. 26: The Dutch kidney guide |

Website |

|

No | Yes | n.a. | Yes | Yes |

| No.27: Option grid: KRT versus CCM | PDF document (1 page) |

|

No | Yes | Common European framework of reference level B1 | Yes | Yes |

*Treatment options formulated as reported in the identified records.

APD, ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal aialysis; CCM, conservative care management; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; HD, Haemodialysis; IRD, increased risk donors; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LDKT, living donor kidney transplantation; n.a., not available; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PtDAs, patient decision aids; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Most PtDAs were developed for the general population of patients with AKD, a minority (n=3, 11.1%) were specifically developed for elderly patients with AKD (no.18, 19, 21).

A large proportion of PtDAs (n=23, 85.2%) consist of a single medium format (no.1–8, 10–17, 19–23, 26, 27). Most of these PtDAs (n=11, 47.8%) are interactive websites (no.1–5, 11–14, 17). The remaining PtDAs consist of a combination of different medium formats. A majority of the PtDAs (n=17, 62.9%) contain values-clarification and preference-elicitation exercises (no.1–6, 8–11, 15, 18–20, 23–25).

Two-thirds of the PtDAs (n=18, 66.6%) were developed with the input of patients (no.3, 5–9, 11–14, 16, 19, 20, 22, 24–27), one of which was largely developed with the input of African-American patients (no.24). A minority (n=6, 22.2%) describe a reading level (no.5, 6, 16, 18, 24, 27). Only a few PtDAs (n=5, 18.5%) are not publicly available (no.7, 8, 18, 21, 24).

Ten PtDAs (n=10, 37.0%) were reported to have been implemented in clinical practice (no.6–9, 13, 15, 16, 25–27). The majority (n=17, 62.9%) have been evaluated for their effects on outcomes in the intended users (no.6–11, 13, 14, 16–18, 21, 22, 24–27).

Table 6 provides an overview of the IPDAS minimum standards component scores for 26 of the identified PtDAs. Table S6 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides these scores in greater detail. One PtDA (no. 21) could not be scored according to these criteria because the accompanying documentation did not provide enough information. Decision support interventions have to meet six qualifying criteria to qualify as PtDAs. Just about half (n=13, 48.1%) met all qualifying criteria (no.1, 4–7, 9, 11, 14, 18–20, 23–25). The sixth qualifying criterium (‘the PtDA describes what it is like to experience the consequences of the options’) was the least met criterium by the other PtDAs.

Table 6.

IPDAS minimum standards component scores of the identified PtDAs

| PtDA | Total score | IPDAS-Q1 | IPDAS-Q2 | IPDAS-Q3 | IPDAS-Q4 | IPDAS-Q5 | IPDAS-Q6 | IPDAS-C1 | IPDAS-C2 | IPDAS-C3 | IPDAS-C4 | IPDAS-C5 | IPDAS-C6 |

| No.1 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No. 2 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No. 3 | 8 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .4 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .5 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .6 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .7 | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| No .8 | 3 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| No .9 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .10 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| No .11 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .12 | 3 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| No .13 | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .14 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| No .15 | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .16 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .17 | 8 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .18 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| No .19 | 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| No .20 | 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| No .21 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| No .22 | 6 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| No .23 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| No .24 | 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| No .25 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| No .26 | 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| No .27 | 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aids Standards; n.a., not available; PtDAs, patient decision aids.

Table 7 provides an overview of the studies70 121–127 129 130 132 135 142–145 that evaluated 17 PtDAs (no.6–11, 13, 14, 16–18, 21, 22, 24–27). Table S7 in online supplemental appendix 4 provides additional details on these studies. Most (n=8, 47.0%) were evaluated in experimental studies (no.6, 11, 13, 17, 18, 21, 24, 25), three-quarter of which (n=6, 75.0%) were RCTs.70 124 126 127 129 145 Five (n=5, 29.4%) PtDAs (no.7, 8, 16, 26, 27) were evaluated in studies presented in meeting abstracts.132 135 The remaining four (n=4, 23,5%) PtDAs (no.9, 10, 14, 22) were evaluated in observational studies142 144 and mixed-methods studies,122 123 125 130 143 two of which included pilot evaluations.122 125

Table 7.

Overview of studies evaluating the identified PtDAs

| PtDA | Source | Population* | Sample size | Primary outcome(s)† | Secondary outcome(s)† | Main findings‡ |

| What type of dialysis modality? | ||||||

| No. 6 | Multicentre non-randomised controlled study121 | Patients with CKD referred for predialysis services | Total=189

|

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 7 | Meeting abstract of pilot study132 |

|

Total=38 (17 patients) |

Post-intervention: outcomes of acceptability, usability and feasibility of integrating the interventions into existing care models | n.a. |

|

| No. 8 | ||||||

| No.9 | Mixed methods: development and pilot study122 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=137

|

Post-intervention: patient-reported SDM, decisional quality, the patient’s choice of dialysis modality, registration of the dialysis mode for patients starting dialysis | n.a. |

|

| Qualitative study: interviews142 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=349

|

Post-intervention: patients’ experiences on the impact of SDM and Dialysis Choice (DC) on their involvement in the decision-making process | n.a. |

|

|

| Mixed methods: questionnaires and interviews143 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=349

|

Post-intervention: patient-reported SDM, decisional quality, results of semi-structured interviews | n.a. |

|

|

| Qualitative study: interviews144 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=349

|

3 months after dialysis initiation: results of semi-structured interviews | n.a. |

|

|

| No. 10 | Mixed methods: development and evaluation123 | Patients with an eGFR between 10 and 20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=22 |

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 11 | RCT124 | Patients with an eGFR <25 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=133

|

|

|

|

| Transplantation or dialysis? | ||||||

| No. 13 | Multicentre RCT70 | Patients with ESKD and on dialysis for <1 year | Total=470

|

Pre-intervention and immediately post-intervention/control: transplant knowledge |

|

|

| No. 14 | Mixed methods: development and pilot study125 | Patients considering renal transplantation | Total=81 |

|

n.a. |

|

| No. 16 | Meeting abstract of prospective cohort study135 |

|

Total=293 (176 patients) | Post-intervention: patient-reported SDM, SDM awareness and use of the Option grid: KRT, the Dutch Kidney Guide and the Option grid: KRT versus CCM by healthcare professionals | n.a. |

|

| Accept or decline IRD kidney offer? | ||||||

| No. 17 | RCT126 | Kidney transplant candidates | Total=288

|

Immediately and at 1 week post-intervention/control: IRD knowledge kidneys, willingness to accept an IRD kidney offer, experiences with Inform Me | Pre-intervention/control: patient characteristics, health literacy, health numeracy |

|

| Dialysis or CCM? | ||||||

| No. 18 | RCT127 | Patients >70 years of age with AKD | Total=41

|

1 month and 3 months post-intervention/control: decisional regret, decisional conflict |

|

|

| No. 21 | Multicentre RCT129 | Patients >65 years of age with an eGFR <25 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=104

|

Pre-intervention and post-intervention/control: supportive kidney care knowledge |

|

|

| Transplantation, dialysis or CCM? | ||||||

| No. 22 | Mixed methods: development and evaluation130 | Patients with an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total=65 | Pre-intervention and 2 months post-intervention: decisional quality | n.a. |

|

| No. 24 | Multicentre RCT145 | Self-reported African-Americans with ESKD <2 years | Total=92

|

1, 3 and 6 months post-intervention/control: discussing LDKT with family members, discussing LDKT with their doctor, initiation of the recipient medical evaluation for LDKT, completion of the recipient evaluation for LDKT, identification of a potential live kidney donor, participants beliefs about kidney transplant and their concerns about LDKT |

|

|

| No. 25 | Multicentre pre-post study178 | Patients referred for ESKD education | Total=97 | Pre-intervention and post-intervention: patient characteristics, knowledge, worries, values and decision-making experience with the decision-aid, experienced education-methods, utilisation level of the decision-aid, whether decision-making involved significant others, ranking of preferred treatment options | n.a. |

|

| No. 26 | Meeting abstract of prospective cohort study135 |

|

Total=293 (176 patients) | Post-intervention: patient-reported shared decision-making, SDM awareness and use of the Option grid: KRT, the Dutch Kidney Guide and the Option grid: KRT versus CCM by healthcare professionals | n.a. |

|

| No. 27 | ||||||

*Population formulated as reported in the identified records.

†Outcomes formulated as reported in the identified records.

‡Main findings formulated as reported in the identified records.

AKD, advanced kidney disease; CCM, conservative care management; CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease; DDKT, deceased donor kidney transplantation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HD, Haemodialysis; IRD, increased risk donors; KRT, Kidney Replacement Therapy; LDKT, Living Donor Kidney Transplantation; n.a., not applicable; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PREPARED, providing resources to enhance African-American patients' readiness to make decisions about kidney disease; PtDAs, patient decision aids; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SDM, shared decision-making; YODDA, Yorkshire dialysis decision aid.

PtDAs were generally evaluated for their effects on health-related outcomes, and on knowledge, decisional quality and patient activation. Only one PtDA (no.7) was evaluated for its effects on SDM.122 143 One meeting abstract presented a study that evaluated whether SDM scores differed among hospitals if PtDAs (no.16, 26, 27) were used or not.135 Ten (n=10, 37.0%) PtDAs (no.9, 10, 11, 13, 16, 18, 21, 24, 26, 27) were evaluated in studies published after the standardised outcome sets for CKD, dialysis and transplantation were published by ICHOM and SONG. None of these PtDAs were evaluated with these outcomes. Patients that used PtDAs were generally more knowledgeable about their treatment options, and had better scores of decisional quality and patient activation than patients that did not use PtDAs (see table 7). The two studies that evaluated the PtDA (no.7) on outcomes of SDM showed that patients experienced the intervention as SDM (see table 7). The meeting abstract that presented a study that evaluated whether SDM scores differed among hospitals if PtDAs were used or not showed that hospitals that used these PtDAs (no.16,26,27) generally had better scores for SDM compared with hospitals that did not use them (see table 7). However, these differences were not significant (see table 7).