Abstract

The synergistic interaction between advanced biotechnology and nanotechnology has allowed the development of innovative nanomaterials. Those nanomaterials can conveniently act as supports for enzymes to be employed as nanobiocatalysts and nanosensing constructs. These systems generate a great capacity to improve the biocatalytic potential of enzymes by improving their stability, efficiency, and product yield, as well as facilitating their purification and reuse for various bioprocessing operating cycles. The different specific physicochemical characteristics and the supramolecular nature of the nanocarriers obtained from different economical and abundant sources have allowed the continuous development of functional nanostructures for different industries such as food and agriculture. The remarkable biotechnological potential of nanobiocatalysts and nanosensors has generated applied research and use in different areas such as biofuels, medical diagnosis, medical therapies, environmental bioremediation, and the food industry. The objective of this work is to present the different manufacturing strategies of nanomaterials with various advantages in biocatalysis and nanosensing of various compounds in the industry, providing great benefits to society and the environment.

1. Introduction

Environmental pollution has reached a tipping point in our biosphere, jumping from stage 2 to stage 3 of the Anthropocene epoch, where human activities have been predicted to affect the structure and functioning of the Earth System.1 The major concerns are carbon dioxide emissions, greenhouse gas emissions, and water pollution, which are usually concentrated in urban areas as a centralized source of these contaminants. In contrast, soil and water from rural areas are mainly contaminated by chemical agricultural products. In addition, resource exploitation is responsible for burst environmental crises (e.g., hydrocarbon spills, mineral extraction, and waste management in different contexts and some remote locations). As a recent example, the long-term studies in air pollution comparing several cities reflect hot spots of air pollution.2 A similar study on water pollution and its correlation to high-density populations was performed.3 In the case of soil and water pollution from rural areas, the contaminants are different and mostly related to pesticides and animal waste. As a consequence of high pollution, nonaccessible regions for humans have been polluted. The Arctic waters have reached alarming levels of contamination, and the Arctic Basin Ecosystem rivers have heavy metals, radionuclides, and oil hydrocarbons.4 Such studies give an overview of the pollution and sources, some of them directly identified with complex infrastructure and highly trained personnel. However, it evident that information availability can catalyze awareness and action. The information on pollution can be available in a practical manner through novel sensing technology. The development of sensors, biosensors, and nanosensors is a research field that has bloomed with the availability of micro and nanofabrication technologies. In addition, nanobiocatalysis has the potential to be applied for the degradation of complex pollutants with great advantages, such as specificity, efficiency, durability, applicability, and performance among others.

The present work discusses the recent advances in the applied research of new nanomaterials developed for nanobiocatalysis and nanosensing in the areas of food, environment, biomedicine, and biofuels, to improve the current biotechnological processes and provide economic and environmental benefits.

2. Nanomaterial Constructs for Nanobiocatalysis and Nanosensing

Nanotechnology has offered great opportunities for the biotechnological development of science and industry, achieving potential applications in areas such as medicine, environmental remediation, energy, aeronautics, space exploration, and electronics, among others.5 During the development of nanotechnology, synergistic effects have resulted from innovative interactions between different technologies; nanobiocatalysis and nanosensing are two typical examples.6 In this manner, nanomaterials—defined as materials with at least one dimension in the size range of 1 to 100 nm—have played a fundamental role in the development and progress of biocatalysis and sensing. According to the dimensionality, nanomaterials are classified into 0-D, 1-D, and 2-D nanostructures depending on the number of dimensions outside the nanoscale range.7 Interestingly, a wide diversity of nanomaterials can be derived since nanostructures can be composed of multiple functional materials such as carbon, metals, metal oxides, semiconductors, and polymers, among others.8

2.1. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Among the great diversity of nanostructured materials, carbon-based nanomaterials have been widely studied due to their exceptional and unique electrochemical properties and their availability to form 0-D, 1-D, 2-D, and 3-D nanostructures.8 For instance, carbon nanomaterials can be found as 0-D fullerenes and carbon dots,9 1-D carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers,10 2-D graphene,11 and 3-D graphite nanostructures.8 Carbon-based nanomaterials—as well as other nanomaterials—can be prepared through different synthesis methods, all of them belonging to the “top-down” or “bottom-up” approach, which are two opposite ways to approach the nanoscale. The “top-down” consists of reducing the size of bulk materials using physical or chemical forces such as occurs during pyrolysis, electrochemical synthesis, chemical oxidation, and arc discharge.12 Size transformation of bulk materials into nanostructures is typically straightforward; however, the synthesis of nanomaterials with precise control of size and shape through these techniques remains a challenge.13 On the other hand, the “bottom-up” approach refers to constructive techniques that involve the assembling of molecules or atoms to form larger nanostructures.13 In comparison to “top-down”, this approach generates less/no waste materials, and the particle size of nanomaterials can be better controlled.14 Hydrothermal, microwave-assisted, coprecipitation, and sol–gel methods are common examples of this approach. For many researchers, carbon nanomaterials have been the preferred selection for sensing applications due to their charge transfer properties, large surface area, and easy surface functionalization.15

Among the vast array of carbon-based nanomaterials, carbon dots (CDs) are an ideal choice due to their fascinating properties such as fluorescence, biocompatibility, easy surface modification, and enzyme-mimicking capacities, among others.16,17 Since their discovery in 2004,18 studies regarding the understanding of CDs’ properties and their multiple applications have shown an increasing trend. CDs consist of a carbon spherical shaped nanoparticle smaller than 10 nm with a carbon core—either amorphous, crystalline, or a mix of both—and a surface typically rich in functional groups.16 In the literature can be found successful examples of the employment of CDs in many areas including biomedicine, energy storage, and environmental remediation;19−21 however, they have demonstrated outstanding performances in nanosensing, an application that has been widely explored in recent times. CDs-based sensors have achieved a selective and sensitive detection of different molecules and pollutants including pharmaceutical compounds,19 amino acids,22 organic pollutants,23 and heavy metals,24 among others.

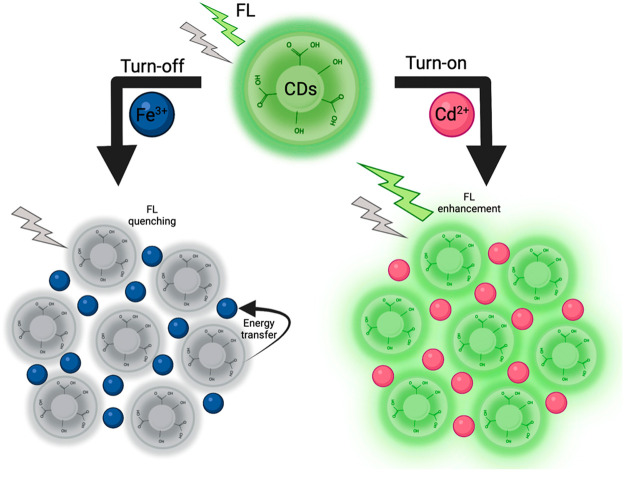

CDs’ fluorescence properties are the main relevance for nanosensing applications since visible effects on their fluorescence are expected to be observed when being exposed to targets. In this manner, the presence of a specific molecule/pollutant leads to changes in the fluorescence intensity, either enhancement (turn-on) or quenching (turn-off) (Figure 1). Moreover, the enhancement of CDs’ fluorescence properties and thus their performance as nanosensors has been recently explored by researchers using different strategies including surface passivation and element doping. As a representative example, CDs with a particle size in the range of 1–5 nm were prepared from Mangifera indica leaves through an eco-friendly method by Singh et al.25 Their CDs showed excellent fluorescent properties and an excellent sensitivity to detect Fe2+ ions (detection limit of 0.62 ppm) based on photoluminescence quenching. In addition, CDs showed good performance on real samples and great stability over a long period.25

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of fluorescence response for the detection of metal ions. Abbreviations: CDs (carbon dots), FL (fluorescence). Reprinted from ref (24). Copyright 2021 Elsevier B.V. License Number: 5356730106426.

Moreover, the enhancement of CDs’ fluorescence properties and thus their performance as nanosensors has been recently explored by researchers using different strategies including element doping and surface passivation. The doping strategy consists of the addition of metallic elements or heteroatoms on the CDs to improve their properties and performance by the modifications in their electronic structure. Nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and boron are frequently used to prepare doped-CDs as metal ion nanosensors.26 Similarly, surface passivation processes can be added during the synthesis of CDs to improve their photoluminescence properties; this improvement is mainly associated with surface energy traps that become emissive. Passivation processes are commonly performed using polymers or organic molecules, in which polyethylene glycol (PEG) stands out due to its wide application for the passivation of CDs.26

Other carbon-based nanomaterials have been used for the same purpose, including carbon nanotubes,26,27 carbon nanospheres,28 graphitic carbon nitride,29 and graphene;30 those nanosensor constructs have been successfully applied to detect phenolic compounds, ethanol gas, endocrine-disrupting compounds, pharmaceutical compounds, and metal ions. Overall, carbon-based nanomaterials have shown great potential as nanosensors to detect a wide diversity of molecules, expanding their application in environmental monitoring, food security, and medical diagnosis.10,15,16,24

Recently, carbon-based nanomaterials have also been used as supports to immobilize enzymes to produce nanobiocatalysts. This has led to great advancements in nanobiocatalysis, because of the synergistic interaction between biotechnology and nanotechnology. Many nanomaterials have been used as support matrices for the immobilization of enzymes. For instance, multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are considered excellent solid supports for the immobilization of enzymes due to their exceptional structural properties, in addition to their biocompatibility and mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties.31,32 The advantages of using carbon nanotubes (CNTs) as a support for enzymes have been reported by different research groups. An example is a study performed by Zhang and Cai,33 who evaluated the immobilization of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for the degradation of phenol in wastewater. They compared the performance of the free HRP enzyme to HRP immobilized on carbon nanotubes functionalized with magnetic Fe3O4. Interestingly, optimal results were obtained with the immobilized enzyme; its catalytic activity was more stable within an ample range of pH values, temperature, and time. In addition, a reasonably good recycling capacity was observed (65% of the activity after six cycles) with an easy recovery/separation through the use of an external magnet.33

Similarly, other enzymes have been immobilized on CNTs or CNTs-based composites. For example, laccase from Trametes hirsute was immobilized on MWCNTs combined with polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) for the efficient degradation of carbamazepine and diclofenac. The results demonstrated a significant improvement in the thermal stability and the operation by the immobilization of the enzyme on the carbon support; the immobilized enzyme presented a remarkable enzyme activity of 4.47 U/cm2 and a removal efficiency of 95% within 4 h of reaction (for diclofenac).34 CNTs have been used as excellent supports for a diverse variety of enzymes for different purposes including environmental remediation, water purification, energy production, biosensing, and the food industry.35,36 Like CNTs, graphene and its derivatives have been also widely employed as supports for enzymes to construct efficient nanobiocatalysts.37,38 In general, the potential of carbon-based nanomaterials for nanobiocatalysis is based on their advantages as an excellent support material for enzyme immobilization such as chemical/thermal stability, high affinity to enzymes, reusability, insolubility during the reactions, regeneration, and biocompatibility.31 Thus, carbon-based nanobiocatalysts would eventually enable more practical applications of enzymes in the food industry, bioremediation, fuel production, and medicine.

2.2. Hybrid Nanostructures

Nanostructures have been proved to have great potential in several applications in therapeutics, bioremediation, biosensing, diagnostic, quantification, and others. Hybrid nanostructures emerge as an effective platform for drug delivery, imaging agent, therapeutic, and medical biology applications. A hybrid nanostructure composed of lipid-nanoparticle complexes shows the inherited unique properties of both the inorganic nanoparticles and the lipid assemblies. The nanoparticles within the lipid assemblies largely dictate the attributes and functionalities of the hybrid complexes and are classified as such: liposomes with surface-bound nanoparticles, liposomes with bilayer embedded nanoparticles, liposomes with core-encapsulated nanoparticles, lipid assemblies with hydrophobic core-encapsulated nanoparticles, and lipid bilayer-coated nanoparticles. Those configurations allow encapsulating agents like enzymes, proteins, fluorescently labeled molecules, and others in a complex structure.39,40

Meanwhile, manganese ferrite nanoparticles (MFNs), which can work as a Fenton catalyst, anchored to mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MFMSNs), can be loaded with the photosensitizer molecules like chlorin e6 (Ce6). MFNs have been exploited as an efficient catalyst for the decomposition of H2O241 and the production of O2 to relieve cancer hypoxia. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) can be functionalized with saline agents and exhibit great biocompatibility and high loading capacity due to their unique features such as tunable pore size, and they show excellent stability and biocompatibility and easy surface functionalization.42,43 Other hybrid nanostructures are DNA–nanoparticle conjugates, that can integrate different types of DNA molecules and inorganic nanoparticles. This configuration provides unique properties of DNA such as addressability and recognition, which at the same time allow it to exploit the properties of the inorganic core.44 Structures like nanoflare sensors exhibit negligible cytotoxicity, high stability, specificity, and good cellular uptake due to structural composition.45 These structures are usually synthesized by the direct replacement method and the functional group grafting and subsequent conjugation method. The first method is applicable for NPs with weakly surface-bound ligands, allowing DNA to directly replace the original ligand via dative bonds. The second method is suitable for NPs covered by strong-bound surfactants, such as poly vinylpyrrolidone, trioctylphosphine oxide, and oleic acid, because they lack functional groups for conjugation or the surface-bound groups cannot be easily displaced by direct replacement or noncovalent attachments approaches.46,47

2.3. Enzyme Immobilization on Nanomaterials

Enzymes are natural biocatalysts that accelerate the rate of chemical reactions and contribute to a great variety of functions like photosynthesis and water splitting. These biocatalysts help a chemical reaction take place efficiently and rapidly, without being permanently modified or altering the chemical equilibrium between products and reactants.48 Thus, natural enzymes have expanded their applications to the industry, being used in bioenergy; bioremediation; chemical transformation processes; and the production of fuel, pharmaceuticals, and food.49 Frequently, those industrial applications depend on the ability of enzymes to maintain their structural stability during the reactions, which is a major challenge hindering their potential in the industry. A suitable approach to overcome this challenge involves the immobilization of enzymes on solid supports. In comparison to bulk materials, the use of nanomaterials as supports to immobilize enzymes presents multiple advantages including ease of surface functionalization and larger surface area, which leads to higher enzyme loading and increased exposure of the biocatalyst.50

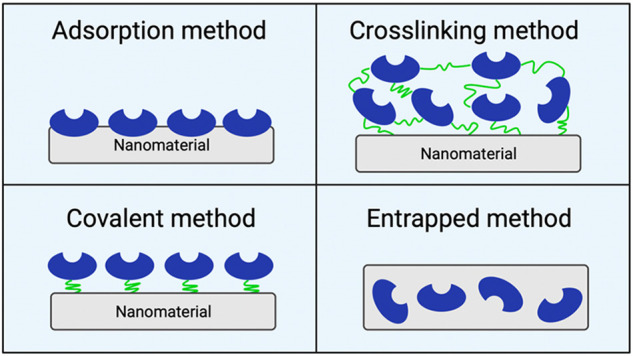

Immobilized methods are mainly relevant for nanobiocatalysts since they affect the performance of enzymes; typically, immobilized methods are classified as adsorption, cross-linking, covalent, and entrapped methods (Figure 2).33 The adsorption method consists of taking advantage of the adsorption force (charge or physical adsorption) of the nanomaterial used as the support. Despite being a simple and direct immobilization methodology, unstable adsorptions usually occur that make it difficult to retain enzymes on the support, which enables enzyme leaching.33,49 The covalent method refers to the covalent conjugation between the free enzyme and the active group of the support material; a long-lasting attachment is achieved, but the enzyme structure could be further altered, directly affecting enzyme activity.32,33 In contrast, the cross-linking method reduces the restriction of enzyme conformational space since immobilization is achieved by using a cross-linking agent that connects the support material with the free enzyme.33 Finally, the entrapped method consists of the formation of the support material in the presence of the free enzyme, encapsulating the enzyme. Negligible structural changes of the enzyme and minimal loss of enzyme and support material can occur during this method, representing significant advantages over other immobilization methods. In addition, good operational stability is typically achieved; however, enzyme leaching can occur if the support material breaks down.51

Figure 2.

Immobilization methods employed for the development of nanobiocatalyts. Created with BioRender.com and extracted under premium membership.

3. Applications in Nanobiocatalysis

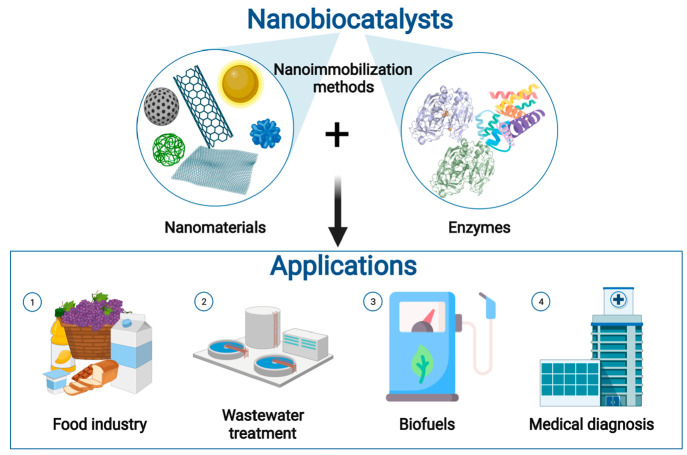

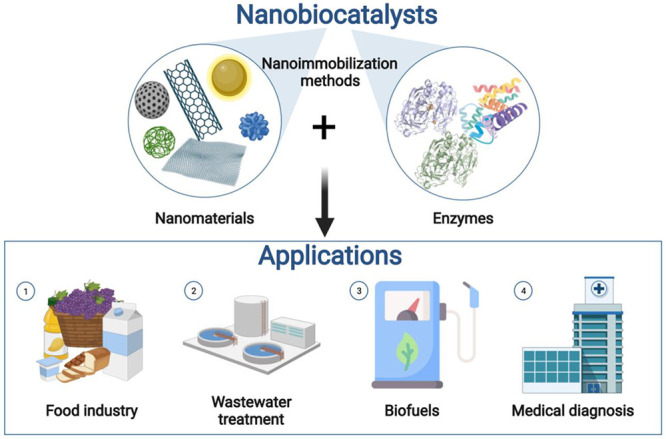

Nanobiocatalysis has emerged as a synergistic interaction of nanotechnology and biotechnology. The different approaches to achieving effective immobilization of natural enzymes onto nanostructures have led to nanobiocatalysts with great potential in the food industry, wastewater treatment, biofuel production, and medical diagnosis, among others (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Components of nanobiocatalysts and their main applications: (1) food sector related applications, (2) wastewater treatment plants for decontamination and degradation of pollutants, (3) energy sector related applications, and (4) biomedical applications. Created with BioRender.com and extracted under premium membership.

3.1. Food Industry

Enzymes are biocatalysts that play a very important role in the food industry for the research and development of food products. Enzymes are organic molecules that are considered “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) that are applied on a large scale as ingredients or auxiliary agents in the processing of many foods.52 Biocatalyzed processes by enzymes are preferred to chemicals, since they have advantages derived from their biological nature, process safety, high yield rates, and low environmental impact.53 The market value of food enzymes is estimated to exceed 3.6 billion US dollars by 2024, which justifies efforts in researching processes for obtaining, purifying, and stabilizing enzymes, which are the main concerns of industrial applications.54 For an enzyme-mediated biotechnological process to be viable, it requires that these enzymes present high activity; high conversion rates; and stability at different temperatures, additives, and pH values. Recent advances in nanotechnology have made enzyme-mediated processes more profitable by providing stability, purification, and reuse facilities. In addition to the improvements in product performance, there have been cost reductions due to reuse and process improvements through nanosystems’ immobilization because it inexpensive, highly available, and nontoxic.55

Nanomaterials can load more enzymes due to the higher surface area/volume ratio, and nanobiocatalysts can be developed by nanoimmobilization methods tailored for each nanomaterial and biocatalyst.56 Fish oil hydrolysis to produce omega-3 fatty acids is one of the applications in the food industry that has been extensively studied with lipases immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles. These nanobiocatalysts have shown a higher selectivity for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and a similar degree of selectivity for eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) when compared with the free enzyme. An efficiency of up to 95% of biocatalysis was optimized for a nanobiocatalyst obtained by covalent bonding and revealed excellent operational stability, and up to 20 reuse cycles could be achieved with only a loss of 50% of the biocatalytic potential; in addition, it presented a better thermochemical stability.54,57 Another study for the hydrolysis of fish oil immobilized lipases from Thermomyces lanuginosus for the preparation of robust nanobiocatalysts using a carbon nanotube carrier. The authors demonstrated that higher enzyme loading, up to 6 mg enzyme per g of support, up to 1.6-fold higher DHA enrichment, with 80% operational stability after 6 reuses, was achieved.57

Amylases are hydrolytic enzymes that convert starch into different products such as reduced sugars, dextrins, and syrups, representing a wide variety of applications as biocatalysts in food, paper, textile, and detergent industries. Due to its multiple industrial applications, the need to immobilize amylases was also generated to improve their stability and reuse. Amylase immobilization with halloysite nanotubes followed by functionalization with 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane resulted in improved enzyme stability and slightly increased enzyme activity when compared with free enzyme.58 Defaei et al.59 immobilized α-amylase on magnetic nanoparticles coated with silica and functionalized with naringin through ionic interactions. The authors reported biocatalytic improvements of the enzyme and excellent operational stability after more than 10 cycles of reuse. Moreover, in comparison to the free enzyme, the immobilized enzyme presented an improvement in storage stability of 60%.

For the production of high-maltose syrups, a recent study reported the immobilization of α-amylase on graphene and magnetite nanoparticles through covalent bonds, which resulted in a nanobiacatalyst with a high enzyme load, 77.58 μg of amylase per 1 μg of support, a 20% increase in alkaline tolerance and reusability up to 11 cycles.59 Many magnetic nanobiocatalytic systems with enzymes such as pectinases, hemicellulases, and cellulases are widely used in the food industry for the clarification of fruit juices.60 Glutaraldehyde-activated magnetite magnetic biocatalysts using pectinases and cellulases were used to clarify grape juice, showing higher activity, thermal stability, and higher reusability, up to 8 cycles.60,61

3.2. Environmental Remediation

The different strategies of nanobiocatalysts have great potential for the development and production of high-quality advanced nanomaterials. The increasing release of polluting agents to the environment due to anthropogenic activities such as mining, electroplating, and other industrial activities, has led to the search for alternative new technologies for the management and treatment of these residues.31 Nanobiocatalysis offers the biological capacity of an enzyme to remove specific pollutants in combination with a nanomaterial that synergistically integrates advanced biotechnology and nanotechnology to provide unique electronic, optical, magnetic, and external stimulate responsive properties that, during the treatment of organic contaminants, dyes, and others complex pollutants, had improved the capabilities showed by different enzymes when are proved by themselves compared with when are fixed over a nanocarrier.60,62 Immobilization of enzymes during biocatalysis avoids some typical barriers for the industrial application of enzymes at large-scale processes, since it allows the reusability and improves the stability of the enzymes during and after their use.63

On the other hand, the increase of new emerging contaminants in wastewater is a major concern due to their potential effect on human health and the current challenges for their removal. Nanostructured materials provide advanced technologies to remove different water pollutants to improve the potentialities of the enzymes. An increase in the contact area is caused by the nanosize and shape, which reduces mass transfer limitation and increases the stabilization and reusability of the enzyme. In this manner, the operational cost decreases while novel nanocatalysts are created without compromising enzyme functionality for remediation.64 The development and application of metallic, carbon-based and derivates, polymer-based, silica-based, and magnetic nanostructured materials used as a host matrix for the immobilization of enzymes on nanobiocatalytic processes for wastewater remediation has been reported to increase the removal efficiencies of dyes, phenols, pesticides, and other aromatic compounds.31,65

Different research has been focused on the development of nanosupport materials that allows immobilization of enzymes without compromising the enzyme activity and the degradation potential while improving enzyme recovery and decreasing fixation cost.66 Laccase immobilization for wastewater treatment has been one of the most studied nanobiocatalysts, showing great potential to remove multiple pollutants such as phenols, dyes, pharmaceuticals, and other aromatic compounds (Table 1).66−80 Nevertheless, in recent years, other enzymes such as glucose oxidase, horseradish peroxidase, and phenolic oxidase have gained interest. During their application, green nanomaterials have been used as supports for the oxidation of phenols and decolorization of dyes.72−74

Table 1. Description of the Most Used Nanobiocatalysts for the Removal of Pollutants in Wastewater.

| enzyme | nanomaterial | immobilization strategy | application | improvement due immobilization | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| laccase | fumed silica | sorption assisted | oxidation of phenolic compounds | increase of enzymatic activity up to 1.64-fold free enzyme | (66) |

| laccase | fumed silica | sorption assisted | elimination of: | higher activity retention over a wide pH range compared with free enzyme | (67) |

| hydroquinone | |||||

| bisphenol A | |||||

| diclofenac | |||||

| gemfibrozil | |||||

| benzophenone-2 | |||||

| benzophenone-4 | |||||

| laccase | zeolitic imidazole framework-8 | covalently | acid blue 92:AB92 degradation | dye removal up to 90% | (68) |

| laccase | graphene oxide-zeolite nanocomposite | covalently | direct red 23 degradation | reusability over five cycles, high storage stability, and thermal stability | (69) |

| laccase | micronanobubbles (MNB) | NSa | degradation of: | degradation 2.3–6.2 higher than only enzyme | (70) |

| bisphenol A | |||||

| bisphenol B | |||||

| bisphenol C | |||||

| mixture of BPA, BPB, BPC | |||||

| laccase | Cu2O nanowire-mesocrystal | covalently | degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol | enzyme activity 10-fold higher than free enzyme | (71) |

| glucose oxidase | Fe2O3 yolk–shell | covalently | decolorization of dyes’ degradation of biophenol A | 32-fold higher stability than the free enzyme | (72) |

| horseradish peroxidase | |||||

| laccase | |||||

| peroxidases | magnetic-core | sorption assisted | phenol removal | enzymes retained 50% of their initial activity after 6 uses | (73) |

| polyphenol oxidase | |||||

| horseradish peroxidase | GO_Fe3O4/Au@CA | sorption assisted | 4-chlorophenols | removal of 98% 4-CP and retention of 95% of the initial activity after three cycles | (74) |

| lignin peroxidase | carbon nanotubes | sorption assisted | decolorization of dyes | increase of 18- and 27-fold of activity compared to the free enzyme | (75) |

| oxidase | Nafion/oil/Pt-nanoparticles | NS | oxidation of glucose, choline, lactate, and sucrose | oxidation rate enhancement by a factor of 10–30 | (76) |

| cyanate hydratase | magnetic-multiwall carbon nanotubes | covalently | treatment of waters with cyanate, chromium, iron, lead, and copper | long-term storage stability | (77) |

| catalase | magnetic-multiwall carbon nanotubes | physical adsorption | treatment of wastewater | improvement of enzyme activity and stability | (78) |

| lipase | ionic liquids-modified carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles | covalently | industrial wastewater treatment | specific activity 1.43 higher than free enzyme | (79) |

| lipase | copper ferrite nanoparticles | covalently | industrial wastewater | high storage and temperature stability; reusability up to 80% after 10 cycles | (80) |

NS = not specified.

3.3. Biofuel Production

Environmental applications of nanobiocatalysis include the removal of organic compounds and dyes during wastewater treatments and soil remediation processes, as well as the improvement of biofuels’ production. Anaerobic digestion and fermentation are the most common processes used for obtaining biofuels and value-added products from biomass. Nevertheless, process efficiencies are mainly controlled by the biomass characterization than environmental and operational conditions, which can result in an inefficient production of the molecules of interest.63 Nanobiocatalysis applied on solid wastes is focused on the degradation of the complex cell wall of different residues, facilitating the extraction of bioactive substances from natural sources. The use of enzymes such as cellulases, hemicellulases, and pectinases has been evaluated for their ability to hydrolyze biomass for biofuels’ production.81 Nanobiocataysis for biofuel production can be described in two main applications: (i) the production of biofuel by enzymatic technologies, which consume less energy and is more environmentally friendly than conventional alkaline catalyzed methods; and (ii) the hydrolysis of cellulose to generate sugars for bioethanol production by fermentation process.60

Immobilization of lipases by the covalent method using different nanomaterials as a host matrix is one of the most reported nanobiocatalyst used for biodiesel production.82 Zulfiqar et al.83 obtained biodiesel that meets the physicochemical characteristics of international standards for biofuels, by the transesterification of Jatropha curcas seed oil using novel nanobiocatalyst lipase-PDA-TiO2, reaching an optimum biodiesel yield of 92%.83 Nanobiocatalysis using immobilized lipase for biodiesel production compared with the application of free lipase demonstrates multiple benefits, such as the increase of the enzyme activity up to 190%, high tolerance to methanol, storage stability, reuse for 10 cycles maintaining up to 84% of its initial activity, and a biodiesel yield of 88% compared with 69% obtained with a free enzyme.84 Another application of lipases as a nanocatalyst is the improvement of biofuels’ production from microalgae, where biodiesel production has reached a biodiesel conversion of 71%, showing a reusability of five cycles and maintaining up to 59% of the catalytic activity.85

Enzyme-based biofuel cells are a technology with attractive attributes for energy conversion, which include renewable catalysts, fuel flexibility, and operation at room temperature. Unfortunately, their limitations remain and include short lifetimes, low power densities, and inefficient fuels’ oxidations.86 Nanostructure biocatalysts have emerged as an alternative to improve the power density of enzyme-based biofuel cells allowing the immobilization of enzymes in a large surface area using various nanostructures including mesoporous media, nanoparticles, nanofibers, and nanocomposites that lead to high concentration loads of enzymes. Is important to consider that both, enzyme stabilization and activation, together with high enzyme loadings in various nanostructures, will significantly improve enzyme-based biofuel cells, due to the apparent enzyme activity improvement by the relieved mass transfer limitations of substrates in nanostructures compared with macro-scale matrices for conventional enzyme immobilization.86,87

The use of nanoparticles has been growing as an enzyme host, an achievement of 6.4 or 10 wt % has been reported thanks to the large surface area per unit mass of nanoparticles. On the other hand, some reports revealed that the mobility associated with the particle size and fluid viscosity could affect the intrinsic activity of the enzymes attached to the particles. Also, it is important to consider that the nanoparticles are frequently in dispersion in the reaction solution, which represents a challenge for recovery and reuse. Nonetheless, the use of magnetic nanoparticles could be a solution to this problem, making easier the recovery using a magnetic field. This approach can increase the stability since the immobilization shows a lower activity.86

Mesoporous materials have been popularized for many applications thanks to controlled porosity and high surface areas. Hosting enzymes for immobilization is one of the widely studied applications for these materials.88 One of the novelties of mesoporous media is their capability to suffer several modifications such as the enlargement of the pore size. It is important to notice that the stability of immobilized enzymes is dependent on factors like pore size and charge interaction. Some authors have reported that the pore size in the material should be similar to or larger than the enzyme size to achieve a successful enzyme immobilization; this also provides better stability on the immobilized enzymes; meanwhile, the charge has a key role in the enzyme stability in mesoporous materials. In this manner, mesoporous materials with the same charge of enzymes, might repel themselves and provide instability in the enzyme immobilization.86,87

The use of nanofibers or nanotubes has been shown to overcome the problems observed in nanoparticles by their dispersions in buffer solution and difficult recovery, and electrospin technologies have proven to be an easier method for nanofibers’ preparations allowing us to use of a wide range of materials that keep the advantages of nanoparticle materials, providing a large surface area to attach enzymes. The use of electrospin technologies allows control of the size, composition, and arrays; because of the structure of nanoparticle materials, their separations can be conducted by highly porous substrates relieving the mass-transfer limitation.86,89−91

3.4. Medical Diagnosis

A constant evaluation of biomarkers is key to surveilling human health and for the diagnosis of several diseases, including cancer. Currently, there is a myriad of detection techniques that require a long preparation time or are susceptible to interference by molecules mixed within samples. Multiple methodologies based on nanotechnology have been developed to increase the resolution of detection without compromising specificity and to minimize costs and time consumption. For example, a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based sensor for inorganic phosphate in urine samples has been developed with a limit of detection (LOD) of 3.8 μmol/L for procedures of 10 samples that lasts 10 min.92 Here, the phosphate in a sample interacts with molecules of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) that are attached to Au nanoparticles (AuNP) and competes with terbium-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid complex ([Tb-EDTA]-1), a luminescent probe. This competition provokes a change in fluorescence intensity that is proportional to the phosphate concentration. Similarly, fluorescence quenching has been used for glutathione sensing based on nanostructures of gold coupled with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and coated with graphene oxide and folic acid. The glutathione, an antioxidant molecule strongly related to several types of cancer, competes with the BSA which leads to the photobleaching of the nanostructure.93

Similarly, functionalized nanostructures have been coupled with enzymes like horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to sense iodide levels in biological fluids;94 with glucose oxidase (GOx) to detect HIV DNA biomarkers95 and colorimetric determination of glucose levels;96 with cholesterol oxidase (ChOx) for cholesterol concentration analysis;97 or with alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for ATP determination.98 Notably, there is a sensor for glucose that utilizes the catalytic energy derived from a combination of HRP and GOx as biofuel.99 Although the enzymatic activity determines its implementation, the stability of nanostructures of polystyrene,95 gold,94,96 graphene,99 or manganese oxide97 allows a reduction in sample manipulation, improves the reaction velocity, and promotes repeatability and reusability. Intrinsic properties of nanostructures have also been used for detection. Principally, optical properties, like those presented for quantum dots100 or CsPbX3 nanocrystals,101 were used to detect pH levels in mitochondria and reactive oxygen species, respectively. Coupling nanostructures with immunology have increased sensing capacity too. Nanosensors based on nanorods of zinc oxide (ZnO) functionalized with monoclonal antibodies for endocrine disruptors with femtomolar sensitivity36 or antibodies attached to magnetic AuNP for detection of hepatotoxins.102

4. Applications in Nanosensing

Nanosensing platforms have been recently able to detect concentrations of chemical species and pollutants or even monitor physical parameters like temperature. In this manner, they can be employed in diverse areas such as to ensure food and water quality and for health purposes.

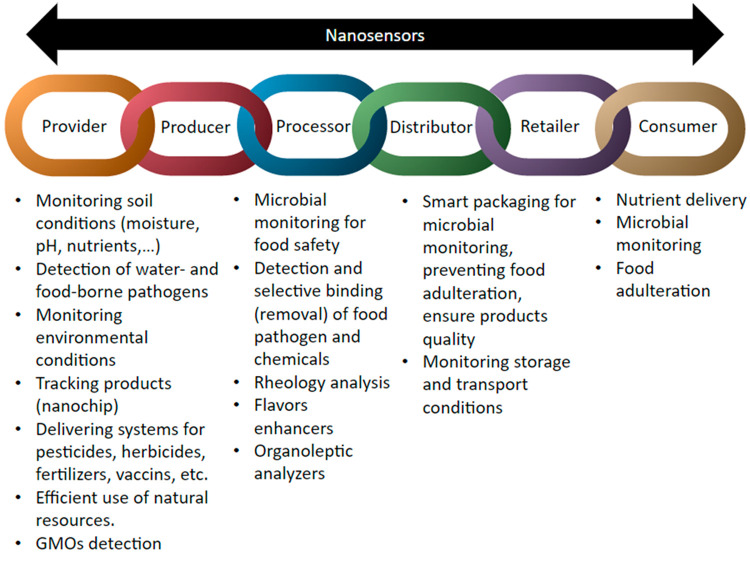

4.1. Food Industry

The increasing demand and the diversification of the global food industry require technological development to ensure food quality, safety, and traceability. There is a major shift toward the use of nanosensing in the food industry due to its advantages over other sensing technologies, including high sensitivity, specificity, reliability, and high-throughput analysis.103 Nanosensors have been implemented across each step of the food supply chain (Figure 4). The extended use of sensors involving nanotechnology in agroindustry, food processing, distribution chain, and even at the consumer level has aimed to enhance food sustainability.

Figure 4.

Application of nanosensors throughout the food supply chain.

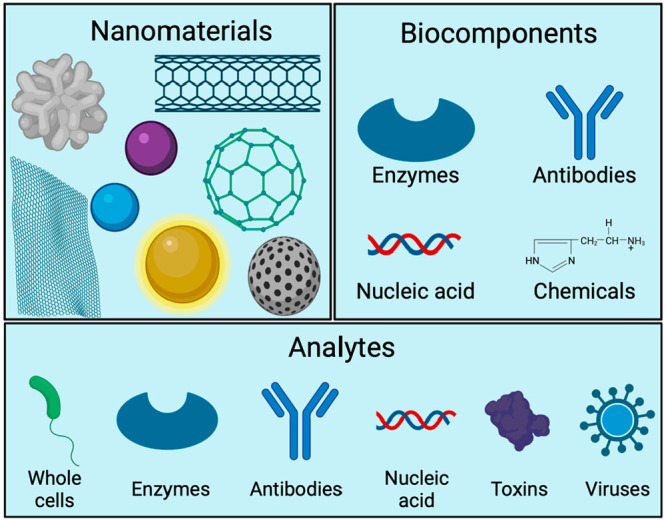

Microbial detection, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, is crucial to control water- and food-borne pathogen outbreaks and ensure food security. Nanosensors are used in food microbiology to detect pathogens in food material, processing plants, final products, and across the distribution chain.104 Pathogens can be detected through the presence of whole cells, nucleic acids, proteins, and metabolites (e.g., toxins, urea, glucose). Nanotubes, nanowires, nanoparticles, nanosheets, and porous nanostructures have been designed as nanostructured transducers for monitoring pathogens in food (Figure 5).105 Such nanostructures are coupled to antibodies, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and nucleic acids to selectively bind with targets. These nanosensors have been developed to improve detection limits,106−108 allow simultaneous detection of pathogens,109 differentiate Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria,105 and detect multidrug resistant strains.110 Recently, nanosensors have been applied in packaging material to respond to environmental conditions during storage and transport to monitor food degradation due to temperature, pH, and moisture changes. Nanosensors are also used to monitor the growth of pathogens, mycotoxins, and some chemicals such as antibiotics that can act as preservatives or antimicrobials to ensure food quality and safety (Table 2).106

Figure 5.

Common types of nanomaterials, biocomponents, and analytes in nanosensing. Created with BioRender.com and extracted under premium membership.

Table 2. Examples of Nanostructured-Based Sensors for Detection of Food Contaminants.

| type of food contaminants | materials | detection techniques | applications | detection limit | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogens | |||||

| Salmonella typhimurium | Fe-MOF/PtNPs | microfluidic immunosensor | food sample | 93 cfu/mL | (111) |

| Escherichia coli | MIL-53(Fe)/PEDOT | electrochemical | water | 4 cfu/mL | (112) |

| Ab/Cu3(BTC)2-PANI/ITO | electrochemical | water | 2 cfu/mL | (113) | |

| Cu-MOF NP | colorimetric | milk | 2 cfu/mL | (114) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2D MOF | electrochemical | - | 6 cfu/mL | (115) |

| NH2-MIL-53(Fe) | photoluminescence | cream pastry | 85 cfu/mL | (116) | |

| Mycotoxins | |||||

| 3-nitropropionic acid | [Zn2(tcpbp)(4,40 -bipy)2] | fluorescence | sugar cane | 1.0 μM | (117) |

| Eu-MOF (1) | r fluorescence | moldy sugar cane | 12.6 μM | (118) | |

| aflatoxin B1 | UiO-66-NH2 | fluorescence | corn, rice and milk | 0.35 ng/mL | (119) |

| Zr-LMOF/MF | fluorescence | water | 1.6 mg/L | (120) | |

| patulin | MIP/Au@Cu-MOF/N-GQDs/GCE | electrochemical | fruit juices | 0.0007 ng/mL | (121) |

| Antibiotics | |||||

| tetracycline | Eu-MOF (1) | fluorescence | water | 3 nM | (122) |

| Eu-MOF | fluorescence | milk and beef | 22 and 21 μM | (123) | |

| cephalexin | gCDc/AuNCs @ ZIF-8 | r fluorescence | milk | 0.04 ng/mL | (124) |

| metronidazole | MIL-53(Fe)@MIP | fluorescence | milk | 53.4 nM | (125) |

| chloramphenicol | MIP/Zr-LMOF | fluorescence | milk and honey | 0.11 and 0.13 μg/L | (126) |

| nitrofurans | Eu-MOFs | fluorescence | food | 1.08 μM | (127) |

| {[Cd3(TDCPB)·2DMAc]·DMAc·4H2O}n | fluorescence | milk | 105 μM | (128) | |

4.2. Environmental Remediation

Another potential application of nanosensing has focused on the development of sensors for environmental applications. Some of the advantages of these sensors are a decrease in fabrication cost, improved sensitivity and detection potential, and selectivity. The use of some high-cost materials during the construction of sensors is usually required and their substitution represents a great challenge. Nanosensors have successfully been fabricated, and their comparison with conventional sensors showed that no significant difference has been found between the detection of some contaminants when nanosensors are used, in terms of concentration sensitivity and detection capacity.129 Environmental applications of nanosensing are directed to the detection of different contaminants. Ethanol detection by a chemical sensor fabricated by employing CeO2 nanoparticles, showed high sensitivity and detection even at low concentrations.130 Furthermore, nanosensors can take advantage of nanobiocatalysis for the detection of a broad range of analytes improving the selectivity for the detection of some specific contaminants.131 In this sense, Patel et al.,70 developed a nanosensor based on the nanobiocatalyst prepared using yolk–shell particle-based laccase that showed an improvement in the selectivity of 2,6-dimethoxyphenol.72

Globally, agriculture is one of the primary industries and its development involves a high-water demand and discharges of pesticides, fertilizers, and other pollutants. Nanobiosensors can be applied to monitor parameters like temperature, humidity, and other soil components in order to reduce the usage of water and chemicals at specific times and locations.132 The development of nanobiosensors for the detection of organic pollutants and their application in agriculture includes the detection of acetamiprid, dinosulfon, phenols, and organophosphate pesticides, reaching high accuracies and sensibility.107,133−136 Lipid membrane nanosensors have provided a tool for the detection of insecticides, pesticides, hydrazines, toxins, and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, among other contaminants; they have been implemented in real samples and even at a pilot scale, showing excellent results. This new generation of biosensing has the potential for developing site-specific responses that ensure environmental protection.137

4.3. Medical Diagnosis

Nanomaterials have emerged recently as multifunctional blocks for the development of next generation sensing technologies for a wide range of industrial sectors, including the medical field. Emerging nanoparticles-based sensors include electrochemical, electrochemiluminescent, colorimetric, fluorescent, chemiluminescent, surface plasmon resonance sensors, quartz crystal microbalance, surface-enhanced Raman scattering, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and metal-oxide gas, among other sensors. Most of these nanosensing technologies are based on nanoparticle detection.138 Nanosensors are designed to detect target analytes and measure them through spectral, optical, chemical, electrical, electrochemical, magnetic, or mechanical signals.139

Traditional diagnostic methods, including chemical markers and imaging methods, have been in constant development to increase the real-time measurements, lower the costs and time-consumption, and provide early-stage and disease prognosis as gold-standard tests.140 Including a conversion between diagnostic and nanomaterials can improve the precision, treatment outcomes, early-stage disease detection, a personalized patient treatment plan, low concentration of metabolites, identification of biomarkers, sensitivity, and so on. Also, these detection markers have been identified in different types of human samples, such as liquid biopsies taken from blood, urine, sweat, saliva, and breath, where the aim is to determine an accurate diagnosis in a noninvasive type of sample.139

5. Conclusions, Current Challenges, and Recommendations

Recent developments in nanobiocatalysis and nanosensing have shown great potential in the food industry, medical diagnosis, and environmental remediation. In this Review, we summarized and discussed the employment of novel nanomaterials for the quantification of a range of substances on different media. Overall, they have demonstrated high effectiveness and specificity. On the other hand, a vast diversity of nanostructures has been applied as a support material for enzymes to form efficient nanobiocatalysts. In this regard, we have discussed the most recent advancements in nanobiocatalysis. Finally, current challenges regarding specificity, stability, and toxicity concerns for nanomaterials’ leaching are presented. Thus, further research efforts should be directed to address such inconveniences. Despite the great benefits of nanosensors in the food industry, potential toxicity and environmental effects are raising concerns. Therefore, studies must be standardized to determine the effect of nanoparticles on humans and the environment.103 Selectivity, specificity, linearity of the response, reproducibility of signal response, quick response time, stability, and operating life are key requirements to successfully develop biosensors.103

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) and Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico under Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI) program awarded to Rafael Gomes Araújo (CVU: 714118), Manuel Martínez Ruiz (CVU: 418151), Juan Eduardo Sosa Hernández (CVU: 375202), Roberto Parra Saldívar (CVU: 35753), and Hafiz M.N. Iqbal (CVU: 735340).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CDs

carbon dots

- MWCNTs

multiwalled carbon nanotubes

- SWCNTs

single-walled carbon nanotubes

- CNTs

carbon nanotubes

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- MFNs

mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- MFMSNs

manganese ferrite nanoparticles

- GRAS

generally recognized as safe

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- LOD

limit of detection

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- AuNP

Au nanoparticles

- Tb-EDTA]-1

terbium-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid complex

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- GOx

glucose oxidase

- ChOx

cholesterol oxidase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ZnO

zinc oxide

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Grainger A. The prospect of global environmental relativities after an Anthropocene tipping point. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 79, 36–49. 10.1016/j.forpol.2017.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L.; Gong P. Urban and air pollution: a multi-city study of long-term effects of urban landscape patterns on air quality trends. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18618. 10.1038/s41598-020-74524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Duan X.; Stewart B.; You B.; Jiang X. Spatial correlations between urbanization and river water pollution in the heavily polluted area of Taihu Lake Basin, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 735–752. 10.1007/s11442-013-1041-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varotsos C.; Krapivin V. Pollution of Arctic waters has reached a critical point: An innovative approach to this problem. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 343. 10.1007/s11270-018-4004-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad I. A comparative study of research and development related to nanotechnology in Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101888. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Grate J.; Wang P. Nanobiocatalysis and its potential applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (11), 639–646. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhoum A.; García-Betancourt M.; Jeevanandam J.; Hussien E.; Mekkawy S.; Mostafa M.; Omran M.; Abdalla M.; Bechelany M. Review on Natural, Incidental, Bioinspired, and Engineered Nanomaterials: History, Definitions, Classifications, Synthesis, Properties, Market, Toxicities, Risks, and Regulations. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12 (2), 177. 10.3390/nano12020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuantranont A.Nanomaterials for Sensing Applications: Introduction and Perspective. In Applications of Nanomaterials in Sensors and Diagnostics; Tuantranont A., Ed.; Springer Series on Chemical Sensors and Biosensors, Vol 14; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Chen P.; Deng J.; Chen Y.; Liu H. Carbon-dot hydrogels as superior carbonaceous adsorbents for removing perfluorooctane sulfonate from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435 (Part 2), 135021. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Wu S.; Wang J.; Yu A.; Wei G. Carbon nanofiber-based functional nanomaterials for sensor applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9 (7), 1045. 10.3390/nano9071045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner E.; Hirsch T. Recent developments in carbon-based two-dimensional materials: synthesis and modification aspects for electrochemical sensors. Microchim. Acta 2014, 187, 441. 10.1007/s00604-020-04415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I.; Arora R.; Dhiman H.; Pahwa R. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Turkish J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 15 (2), 219–230. 10.4274/tjps.63497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid N.; Khan A.; Shujait S.; Chaudhary K.; Ikram M.; Imran M.; Haider J.; Khan M.; Khan Q.; Maqbool M. Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 300, 102597. 10.1016/j.cis.2021.102597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Zarate D.; Garcia-Meca C.; Pinilla-Cienfuegos E.; Ayucar J. A.; Griol A.; Bellieres L.; Hontanon E.; Kruis F. E.; Marti J. Green and sustainable manufacture of ultrapure engineered nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2020, 10 (3), 466. 10.3390/nano10030466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barros A.; Braunger M.; de Oliveira R.; Ferreira M.. Functionalized Advanced Carbon-Based Nanomaterials for Sensing. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences; Elsevier, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Cantu D.; González-González R. B.; Melchor-Martínez E. M.; Martínez S. A. H.; Araújo R. G.; Parra-Arroyo L.; Sosa-Hernández J. E.; Parra-Saldívar R.; Iqbal H. M. N. Enzyme-mimicking capacities of carbon-dots nanozymes: Properties, catalytic mechanism, and applications – A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 676–687. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Yi G.; Li P.; Zhang X.; Fan H.; Zhang Y.; Wang X.; Zhang C. A minireview on doped carbon dots for photocatalytic and electrocatalytic applications. Nanoscale 2020, 12 (26), 13899–13906. 10.1039/D0NR03163A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.; Ray R.; Gu Y.; Ploehn H. J.; Gearheart L.; Raker K.; Scrivens W. A. Electrophoretic analysis and purification of fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (40), 12736–12737. 10.1021/ja040082h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-González R. B.; Sharma A.; Parra-Saldívar R.; Ramirez-Mendoza R. A.; Bilal M.; Iqbal H. M. N. Decontamination of emerging pharmaceutical pollutants using carbon-dots as robust materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423 (Part B), 127145. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A M M.; Hasan M. A.; Reza A.; Islam M. M.; Susan M. A. B. H. Carbon dots as nano-modules for energy conversion and storage. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102732. 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talib A. B.; Mohammed M. H. Preparation, characterization and preliminary cytotoxic evaluation of 6-mercaptopurine-coated biotinylated carbon dots nanoparticles as a drug delivery system. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z.; Zeng Q.; Deng Q.; Yao W.; Deng H.; Lin X.; Chen W. Citric acid-derived carbon dots as excellent cysteine oxidase mimics for cysteine sensing. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2022, 359, 131563. 10.1016/j.snb.2022.131563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogireddy N.K.R.; Cruz Silva R.; Valenzuela M. A.; Agarwal V. 4-nitrophenol optical sensing with N doped oxidized carbon dots. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 386, 121643. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenice Gonzalez-Gonzalez R.; Parra-Saldivar R.; Ramirez-Mendoza R. A.; Iqbal H. M.N. Carbon dots as a new fluorescent nanomaterial with switchable sensing potential and its sustainable deployment for metal sensing applications. Mater. Lett. 2022, 309, 131372. 10.1016/j.matlet.2021.131372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J.; Kaur S.; Lee J.; Mehta A.; Kumar S.; Kim K. H.; Basu S.; Rawat M. Highly fluorescent carbon dots derived from Mangifera indica leaves for selective detection of metal ions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137604. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-González R. B.; Morales-Murillo M. B.; Martínez-Prado M. A.; Melchor-Martínez E. M.; Ahmed I.; Bilal M.; Parra-Saldívar R.; Iqbal H. M. N. Carbon dots-based nanomaterials for fluorescent sensing of toxic elements in environmental samples: Strategies for enhanced performance. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134515. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein H. T.; Kareem M. H.; Abdul Hussein A. M. Synthesis and characterization of carbon nanotube doped with zinc oxide nanoparticles CNTs-ZnO/PS as ethanol gas sensor. Optik 2021, 248, 168107. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.168107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X.; Wang M.; Tang Y. Green synthesis of fluorescent carbon nanospheres from chrysanthemum as a multifunctional sensor for permanganate, Hg(II), and captopril. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 271, 120886. 10.1016/j.saa.2022.120886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswaran M.; Tsai P. C.; Wu M. T.; Ponnusamy V. K. Novel nano-engineered environmental sensor based on polymelamine/graphitic-carbon nitride nanohybrid material for sensitive and simultaneous monitoring of toxic heavy metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126267. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhu Y.; Wang C.; He M.; Lin Q. Selective detection of water pollutants using a differential aptamer-based graphene biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 59–67. 10.1016/j.bios.2018.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal M.; Ashraf S. S.; Ferreira L. F. R.; Cui J.; Lou W. Y.; Franco M.; Iqbal H. M. N. Nanostructured materials as a host matrix to develop robust peroxidases-based nanobiocatalytic systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1906–1923. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W.; Ji P. Enzymes immobilized on carbon nanotubes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29 (6), 889–895. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Cai X. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on Fe3O4/nanotubes composites for Biocatalysis-degradation of phenol. Compos. Interfaces 2019, 26 (5), 379–396. 10.1080/09276440.2018.1504265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masjoudi M.; Golgoli M.; Ghobadi Nejad Z.; Sadeghzadeh S.; Borghei S. M. Pharmaceuticals removal by immobilized laccase on polyvinylidene fluoride nanocomposite with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128043. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari A.; Rajeev R.; Benny L.; Sudhakar Y. N.; Varghese A.; Hegde G. Recent advances in carbon nanotubes-based biocatalysts and their applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 297, 102542. 10.1016/j.cis.2021.102542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. S.; Chauhan K.; Kennedy J. F. Fructose production from inulin using fungal inulinase immobilized on 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 41–52. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharati Vineh M.; Saboury A. A.; Poostchi A. A.; Rashidi A. M.; Parivar K. Stability and activity improvement of horseradish peroxidase by covalent immobilization on functionalized reduced graphene oxide and biodegradation of high phenol concentration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1314–1322. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q.; Huang J.; Ding Y.; Tang H. Catalytic oxidation of phenol and 2,4-dichlorophenol by using horseradish peroxidase immobilized on graphene oxide/Fe3O4. Molecules. 2016, 21 (8), 1044. 10.3390/molecules21081044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Bose A.; Bothun G. D. Controlled release from bilayer-decorated magnetoliposomes via electromagnetic heating. ACS Nano 2010, 4 (6), 3215–3221. 10.1021/nn100274v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas K. M.; Shon Y. S. Hybrid lipid–nanoparticle complexes for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2019, 7 (5), 695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Cho H. R.; Jeon H.; Kim D.; Song C.; Lee N.; Choi S. H.; Hyeon T. Continuous O2-evolving MnFe2O4 nanoparticle-anchored mesoporous silica nanoparticles for efficient photodynamic therapy in hypoxic cancer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (32), 10992–10995. 10.1021/jacs.7b05559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn D.; Ashley C. E.; Xue M. I. N.; Carnes E. C.; Zink J. I.; Brinker C. J. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle nanocarriers: biofunctionality and biocompatibility. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (3), 792–801. 10.1021/ar3000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Wang X.; Li P. Z.; Nguyen K. T.; Wang X. J.; Luo Z.; Zhang H.; Tan N. S.; Zhao Y. Biocompatible, uniform, and redispersible mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer-targeted drug delivery in vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24 (17), 2450–2461. 10.1002/adfm.201302988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F.; Gang O.. DNA Functionalization of Nanoparticles. In 3D DNA Nanostructure; Ke Y., Wang P., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, 2017; pp 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer-Jungemann A.; Harimech P. K.; Brown T.; Kanaras A. G. Gold nanoparticles and fluorescently-labelled DNA as a platform for biological sensing. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9503–9510. 10.1039/c3nr03707j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvana M.; Dharuman V. Tethering of spherical DOTAP liposome gold nanoparticles on cysteamine monolayer for sensitive label free electrochemical detection of DNA and transfection. Analyst 2014, 139 (10), 2467–2475. 10.1039/C4AN00017J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Ang C. Y.; Li M.; Tan S. Y.; Qu Q.; Luo Z.; Zhao Y. Polymer-coated hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles for triple-responsive drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7 (32), 18179–18187. 10.1021/acsami.5b05893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G. M.; Hausman R. E.; Hausman R. E.. The cell: a molecular approach; ASM Press: Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Rostro-Alanis M.; Mancera-Andrade E. I.; Patino M. B. G.; Arrieta-Baez D.; Cardenas B.; Martinez-Chapa S. O.; Saldivar R. P. Nanobiocatalysis: Nanostructured materials–a minireview. Biocatalysis 2016, 2, 1–24. 10.1515/boca-2016-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis I. V.; Vorhaben T.; Tsoufis T.; Rudolf P.; Bornscheuer U. T.; Gournis D.; Stamatis H. Development of effective nanobiocatalytic systems through the immobilization of hydrolases on functionalized carbon-based nanomaterials. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 115, 164–171. 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imam H. T.; Marr P. C.; Marr A. C. Enzyme entrapment, biocatalyst immobilization without covalent attachment. Green Chemi. 2021, 23 (14), 4980–5005. 10.1039/D1GC01852C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porta R.; Pandey A.; Rosell C. M. Enzymes as additives or processing aids in food biotechnology. Enzyme Res. 2010, 2010, 436859. 10.4061/2010/436859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveendran S.; Parameswaran B.; Ummalyma S. B.; Abraham A.; Mathew A. K.; Madhavan A.; Rebello S.; Pandey A. Applications of microbial enzymes in food industry. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56 (1), 16–30. 10.17113/ftb.56.01.18.5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M. L.; Rao N. M.; Tsuzuki T.; Barrow C. J.; Puri M. Suitability of recombinant lipase immobilised on functionalised magnetic nanoparticles for fish oil hydrolysis. Catalysts 2019, 9 (5), 420. 10.3390/catal9050420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shemsi A. M.; Khanday F. A.; Qurashi A.; Khalil A.; Guerriero G.; Siddiqui K. S. Site-directed chemically-modified magnetic enzymes: fabrication, improvements, biotechnological applications and future prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37 (3), 357–381. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M. L.; Abraham R. E.; Puri M.. Nanobiocatalyst designing strategies and their applications in food industry. In Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals; Singh S. P., Pandey A., Singhania R. R., Larroche C., Li Z., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; pp 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Matuoog N.; Li K.; Yan Y. Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles and its application in the hydrolysis of fish oil. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42 (5), e12549. 10.1111/jfbc.12549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey G.; Munguambe D. M.; Tharmavaram M.; Rawtani D.; Agrawal Y. K. Halloysite nanotubes-An efficient ‘nano-support’ for the immobilization of α-amylase. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 136, 184–191. 10.1016/j.clay.2016.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Defaei M.; Taheri-Kafrani A.; Miroliaei M.; Yaghmaei P. Improvement of stability and reusability of α-amylase immobilized on naringin functionalized magnetic nanoparticles: A robust nanobiocatalyst. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 354–360. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshmy R.; Philip E.; Sirohi R.; Tarafdar A.; Arun K.B.; Madhavan A.; Binod P.; Kumar Awasthi M.; Varjani S.; Szakacs G.; Sindhu R. Nanobiocatalysts: advancements and applications in enzyme technology. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125491. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Magro L.; Silveira V. C.C.; de Menezes E. W.; Benvenutti E. V.; Nicolodi S.; Hertz P. F.; Klein M. P.; Rodrigues R. C. Magnetic biocatalysts of pectinase and cellulase: synthesis and characterization of two preparations for application in grape juice clarification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 35–45. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson M.; Zhang H.; Jin B. Nanobiocatalyst advancements and bioprocessing applications. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2015, 12 (102), 20140891. 10.1098/rsif.2014.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Chauhan N. S. Nano-biocatalysts: potential biotechnological applications. Indian J. Microbiol. 2021, 61, 441–448. 10.1007/s12088-021-00975-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shola O. K.; Lau S. Y.; Danquah M.; Chiong T.; Takeo M. Advances in graphene oxide based nanobiocatalytic technology for wastewater treatment. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100647. 10.1016/j.enmm.2022.100647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginet N.; Pardoux R.; Adryanczyk G.; Garcia D.; Brutesco C.; Pignol D. Single-step production of a recyclable nanobiocatalyst for organophosphate pesticides biodegradation using functionalized bacterial magnetosomes. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (6), e21442. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommes G.; Gasser C. A.; Howald C. B.; Goers R.; Schlosser D.; Shahgaldian P.; Corvini P. F. Production of a robust nanobiocatalyst for municipal wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 115, 8–15. 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammann E. M.; Gasser C. A.; Hommes G.; Corvini P. F. Immobilization of defined laccase combinations for enhanced oxidation of phenolic contaminants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1397–1406. 10.1007/s00253-013-5055-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Abdi J. Metal-organic framework as a platform of the enzyme to prepare novel environmentally friendly nanobiocatalyst for degrading pollutant in water. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 80, 606–613. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.08.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Saffar-Dastgerdi M. H. Clean Laccase immobilized nanobiocatalysts (graphene oxide-zeolite nanocomposites): From production to detailed biocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2020, 268, 118443. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Tan L.; Hagedoorn P. L.; Wang R.; Wen L.; Wu S.; Tan X.; Xu H.; Zhou X. Micro-Nano Bubbles Assisted Laccase for Biocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenols. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 48, 102880. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Ma P.; He Y.; Zhang Y.; Luo Y.; Zhang C.; Fan H. Enzyme-Nanowire Mesocrystal Hybrid Materials with an Extremely High Biocatalytic Activity. Nano Lett. 2018, 18 (9), 5919–5926. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S. K.; Anwar M. Z.; Kumar A.; Otari S. V.; Pagolu R. T.; Kim S. Y.; Kim I. W.; Lee J. K. Fe2O3 yolk-shell particle-based laccase biosensor for efficient detection of 2, 6-dimethoxyphenol. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 132, 1–8. 10.1016/j.bej.2017.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marjani A.; Zare M. H.; Sadeghi M. H.; Shirazian S.; Ghadiri M. Synthesis of alginate-coated magnetic nanocatalyst containing high-performance integrated enzyme for phenol removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9 (1), 104884. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarno M.; Iuliano M. New nano-biocatalyst for 4-chlorophenols removal from wastewater. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 20 (Part 1), 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira S. F.; da Luz J. M. R.; Kasuya M. C. M.; Ladeira L. O.; Correa Junior A. Enzymatic Extract Containing Lignin Peroxidase Immobilized on Carbon Nanotubes: Potential Biocatalyst in Dye Decolourization. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2018, 25 (4), 651–659. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Chen L.; Ding Z.; Wang D.; Xie H.; Ni W.; Ye W.; Zhang X.; Jiang L.; Feng X. Enhancement of Interfacial Catalysis in a Triphase Reactor Using Oxygen Nanocarriers. Nano Research 2021, 14 (1), 172–176. 10.1007/s12274-020-3062-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan B.; Pillai S.; Permaul K.; Singh S. Simultaneous Removal of Heavy Metals and Cyanate in a Wastewater Sample Using Immobilized Cyanate Hydratase on Magnetic-Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2019, 363, 73–80. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee-Pour H. A.; Nejadhosseinian M.; Firouzi M.; Masoum S. Catalase Immobilization onto Magnetic Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Optimization of Crucial Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology. New J. Chem. 2019, 43 (2), 593–600. 10.1039/C8NJ03517B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suo H.; Xu L.; Xue Y.; Qiu X.; Huang H.; Hu Y. Ionic Liquids-Modified Cellulose Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Enzyme Immobilization: Improvement of Catalytic Performance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 115914. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otari S. v.; Patel S. K. S.; Kim S. Y.; Haw J. R.; Kalia V. C.; Kim I. W.; Lee J. K. Copper Ferrite Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Immobilization of Enzyme. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2019, 59 (1), 105–108. 10.1007/s12088-018-0768-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Morya V.; Datta B.. Application of nanobiocatalysts on food waste. In Enzymes in Food Biotechnology; Kuddus M., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez S. A.; Melchor-Martínez E. M.; Hernández J. A.; Parra-Saldívar R.; Iqbal H. M. Magnetic nanomaterials assisted nanobiocatalysis systems and their applications in biofuels production. Fuel 2022, 312, 122927. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar A.; Mumtaz M. W.; Mukhtar H.; Najeeb J.; Irfan A.; Akram S.; Touqeer T.; Nabi G. Lipase-PDA-TiO2 NPs: An emphatic nano-biocatalyst for optimized biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas oil. Renew. Energy. 2021, 169, 1026–1037. 10.1016/j.renene.2020.12.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L.; Jiao X.; Hu H.; Shen X.; Zhao J.; Feng Y.; Li C.; Du Y.; Cui J.; Jia S. Activated magnetic lipase-inorganic hybrid nanoflowers: A highly active and recyclable nanobiocatalyst for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 825–832. 10.1016/j.renene.2021.02.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nematian T.; Shakeri A.; Salehi Z.; Saboury A. A. Lipase immobilized on functionalized superparamagnetic few-layer graphene oxide as an efficient nanobiocatalyst for biodiesel production from Chlorella vulgaris bio-oil. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 57. 10.1186/s13068-020-01688-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Jia H.; Wang P. Challenges in biocatalysis for enzyme-based biofuel cells. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006, 24 (3), 296–308. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Grate J. W.; Wang P. Nanobiocatalysis and its potential applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (11), 639–646. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann A.Polymer films with embedded metal nanoparticles; Springer Science & Business Media, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jia H.; Zhu G.; Wang P. Catalytic behaviors of enzymes attached to nanoparticles: the effect of particle mobility. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 84 (4), 406–414. 10.1002/bit.10781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyal A.; Loos K.; Noto M.; Chang S. W.; Spagnoli C.; Shafi K. V.; Ulman A.; Cowman M.; Gross R. A. Activity of Candida rugosa lipase immobilized on γ-Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (7), 1684–1685. 10.1021/ja021223n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Xia Y. Electrospinning of nanofibers: reinventing the wheel?. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16 (14), 1151–1170. 10.1002/adma.200400719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fadhel A. A.; Johnson M.; Trieu K.; Koculi E.; Campiglia A. D. Selective nano-sensing approach for the determination of inorganic phosphate in human urine samples. Talanta 2017, 164, 209–215. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong X. Y.; Quesada-González D.; Manickam S.; New S. Y.; Muthoosamy K.; Merkoçi A. Integrating gold nanoclusters, folic acid and reduced graphene oxide for nanosensing of glutathione based on “turn-off” fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2375. 10.1038/s41598-021-81677-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xianyu Y.; Lin Y.; Chen Q.; Belessiotis-Richards A.; Stevens M. M.; Thomas M. R. Iodide-Mediated Rapid and Sensitive Surface Etching of Gold Nanostars for Biosensing. Angew. Chem. 2021, 60 (18), 9891–9896. 10.1002/anie.202017317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y.; Zhou C.; Wang C.; Cai H.; Yin C.; Yang Q.; Xiao D. Ultrasensitive visual detection of HIV DNA biomarkers via a multi-amplification nanoplatform. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23949. 10.1038/srep23949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiri M. M.; Mulder D. W.; Vorster B. C. Plasmonic detection of glucose in serum based on biocatalytic shape-altering of gold nanostars. Biosensors. 2019, 9 (3), 83. 10.3390/bios9030083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D.; Li C.; Zi Y.; Jiang D.; Qu F.; Zhao X. E. MOF@ MnO2 nanocomposites prepared using in situ method and recyclable cholesterol oxidase–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers for cholesterol determination. Nanotechnology 2021, 32 (31), 315502. 10.1088/1361-6528/abf692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Xianyu Y.; Wu J.; Dong M.; Zheng W.; Sun J.; Jiang X. Double-enzymes-mediated bioluminescent sensor for quantitative and ultrasensitive point-of-care testing. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (10), 5422–5427. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chansaenpak K.; Kamkaew A.; Lisnund S.; Prachai P.; Ratwirunkit P.; Jingpho T.; Blay V.; Pinyou P. Development of a sensitive self-powered glucose biosensor based on an enzymatic biofuel cell. Biosensors. 2021, 11 (1), 16. 10.3390/bios11010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll C.; Roldan M.; Contreras-Montoya R.; Diaz-Mochon J. J.; Martin M.; Ruedas-Rama M. J.; Orte A. Mitochondrial pH Nanosensors for Metabolic Profiling of Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (10), 3731. 10.3390/ijms21103731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Zeng Y.; Qu X.; Jalalah M.; Alsareii S. A.; Li C.; Harraz F. A.; Li G. Biocatalytic CsPbX3 Perovskite Nanocrystals: A Self-Reporting Nanoprobe for Metabolism Analysis. Small 2021, 17 (46), 2103255. 10.1002/smll.202103255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanain W. A.; Izake E. L.; Schmidt M. S.; Ayoko G. A. Gold nanomaterials for the selective capturing and SERS diagnosis of toxins in aqueous and biological fluids. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 664–672. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H.; Sayyar Z.; Anarjan N.; Berenjian A.. Nano-Sensors in food nanobiotechnology. In Nanobiotechnology in food: concepts, applications and perspectives; Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H., Sayyar Z., Anarjan N., Berenjian A., Eds; Springer: Cham, 2019; pp 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pathakoti K.; Manubolu M.; Hwang H. M. Nanostructures: Current uses and future applications in food science. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25 (2), 245–253. 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reta N.; Saint C. P.; Michelmore A.; Prieto-Simon B.; Voelcker N. H. Nanostructured electrochemical biosensors for label-free detection of water-and food-borne pathogens. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (7), 6055–6072. 10.1021/acsami.7b13943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C. A.; Nascimento J. M.; Oliveira I. S.; de Oliveira C. V.; de Melo C. P.; Franco O. L.; Oliveira M. D. Nanostructured sensor based on carbon nanotubes and clavanin A for bacterial detection. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2015, 135, 833–839. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Deng W.; Cheng C.; Tan Y.; Xie Q.; Yao S. Fluorescent immunoassay for the detection of pathogenic bacteria at the single-cell level using carbon dots-encapsulated breakable organosilica nanocapsule as labels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (4), 3441–3448. 10.1021/acsami.7b18714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reta N.; Michelmore A.; Saint C. P.; Prieto-Simon B.; Voelcker N. H. Label-free bacterial toxin detection in water supplies using porous silicon nanochannel sensors. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (6), 1515–1523. 10.1021/acssensors.8b01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner M. B.; Goldsmith B. R.; McMillon R.; Dailey J.; Pillai S.; Singh S. R.; Johnson A. C. A carbon nanotube immunosensor for Salmonella. AIP Adv. 2011, 1 (4), 042127. 10.1063/1.3658573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. N.; Ryu J. S.; Shin C.; Chung H. J. A Carbon-Dot-Based Fluorescent Nanosensor for Simple Visualization of Bacterial Nucleic Acids. Macromol. Biosci. 2017, 17 (9), 1700086. 10.1002/mabi.201700086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R.; Xue L.; Cai G.; Qi W.; Liu Y.; Lin J. Fe-MIL-88NH2Metal-Organic Framework Nanocubes Decorated with Pt Nanoparticles for the Detection of Salmonella. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2021, 4 (5), 5115–5122. 10.1021/acsanm.1c00574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]