Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are pervasive environmental contaminants, and their relative stability and high bioaccumulation potential create a challenging risk assessment problem. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) data, in principle, can be synthesized within a quantitative adverse outcome pathway (qAOP) framework to link molecular activity with individual or population level hazards. However, even as qAOP models are still in their infancy, there is a need to link internal dose and toxicity endpoints in a more rigorous way to further not only qAOP models but adverse outcome pathway frameworks in general. We address this problem by suggesting refinements to the current state of toxicokinetic modeling for the early development zebrafish exposed to PFAS up to 120 h post-fertilization. Our approach describes two key physiological transformation phenomena of the developing zebrafish: dynamic volume of an individual and dynamic hatching of a population. We then explore two different modeling strategies to describe the mass transfer, with one strategy relying on classical kinetic rates and the other incorporating mechanisms of membrane transport and adsorption/binding potential. Moving forward, we discuss the challenges of extending this model in both timeframe and chemical class, in conjunction with providing a conceptual framework for its integration with ongoing qAOP modeling efforts.

Keywords: PFAS, zebrafish embryo, toxicokinetics, diffusion, bioaccumulation, membrane transporters, adsorption, binding

Short abstract

This work proposes mathematical models that add rigor to predicting the accumulation of PFAS within the developing zebrafish, setting a foundation for fish and potentially human health risk assessment.

1. Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have moved beyond the emerging contaminant label and are starting to be noticed outside of the environmental community. The prevalence of PFAS use in various industries and the stability and bioaccumulation of PFAS from both an environmental1,2 and human health standpoint,3−5 including influences on important healthcare outcomes such as vaccine efficacy6,7 and COVID-19 symptom severity,8 creates an immense problem from bioremediation to risk analysis and assessment. On the risk assessment side, given the thousands of compounds that make up the PFAS chemical class,9 there is a data gap in the literature linking internal dose and toxicity endpoints (including mixture toxicity10−12), as pointed out by the recent perspective of Tal and Vogs.13 However, even for the more well-studied PFAS of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), there is still doubt as to the statistical rigor of internal dose and adverse effect relationships in environmentally relevant organisms, such as the toxicological model zebrafish (Danio rerio). Addressing current limitations of zebrafish toxicokinetic models could strengthen the link between the internal dose and toxicity endpoints, as well as provide a means to extrapolate the effects of well-studied chemicals to those of data poor emerging contaminants.

The early development zebrafish is a fundamental component used in the PFAS risk assessment endeavor.14−16 It not only provides a robust animal model to work with in the laboratory, such as its high-throughput compatibility,17 but it also provides a risk assessment model for both the environment (fish in particular) and for potentially humans. In the recent review of Hoffmann et al.18 they conclude that the early development zebrafish has a capacity to identify mammalian prenatal developmental toxicants. Such a conclusion reinforces the promising human risk assessment capability of the zebrafish as the field waits for more human data. In the meantime, new predictive tools and modeling paradigms can be introduced to (1) enhance the fidelity of temporal and spatial distributions of PFAS within the zebrafish using toxicokinetic modeling and (2) predict toxicity endpoints by linking a PFAS distribution with toxicity data through quantitative adverse outcome pathway (qAOP) modeling.

Adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) and AOP networks are gaining popularity and provide a qualitative framework to organize data across vast length scales (from molecules to individuals to populations) and levels of biological organization (from cells to tissues to organs). Specifically, AOPs conceptualize correlated biological key events (KEs) that describe how the activity of a molecular initiating event (MIE) can be associated with an organism level adverse outcome (AO).19−23 As an example that we’re using as a case study, exposure of zebrafish to aqueous PFOA has been linked with iodothyronine deiodinase inhibition, which is the MIE of a thyroid disruptor AOP associated with a reduced young of year survival AO.24 Understanding the toxicokinetics that link exposure with intracellular concentrations could, therefore, inform future new approach methodologies that leverage the chemically agnostic framework of the AOP25 to fill information gaps in the risk assessment of specific chemicals and substances found in the environment.26

In general, toxicokinetic models are important tools for understanding the broad mechanisms of toxicant mass transfer in biological specimens. This mass transfer understanding can, for example, better inform individual or population level predictions of acute or chronic effects. Here, we focus on zebrafish embryos exposed to PFOA and PFOS during early development (0–120 h post-fertilization or hpf) and address some of the limitations of their toxicokinetic models in the literature. A physiologically rigorous toxicokinetic model of zebrafish early development should account for two main phenomena: (1) the dynamic growth of structures associated with embryonic morphogenesis (i.e., surface area and volume) and (2) the asynchronous hatching event and subsequent shedding of the chorion by the zebrafish embryo, resulting in a mixed population of embryos, with and without a chorion over the timescale of about 24 h. Current toxicokinetic models do not adequately account for both phenomena,14,15,27−31 yet they are especially important for modeling organisms in the environment outside of the laboratory setting where physiological manipulation does not take place (e.g., dechorionation). Furthermore, these models, except for Simeon et al.27 rely on classical, mostly first-order kinetic expressions to describe the time evolution of a PFAS concentration, creating a phenomenological modeling framework that is difficult to apply outside of its calibrated window of both time and exposure concentration.

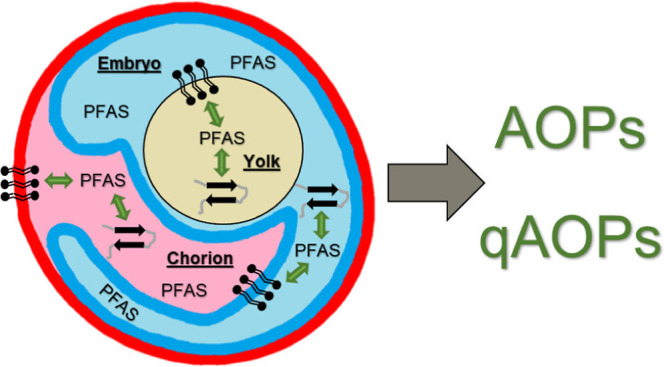

In this work, we propose several toxicokinetic model advancements to predict the PFAS distribution between the chorion and embryo of the early development zebrafish, providing a suitable level of mass balance rigor. In our description of mass transfer within the organism, we alter standard toxicokinetic rate terms to incorporate PFAS specific mechanistic processes, such as classical transporter-mediated membrane transport and PFAS adsorption/binding to account for bioaccumulation. This approach could inform next-generation predictive toxicology and risk assessment frameworks (e.g., qAOP) and improve upon existing methods, such as that presented by Vogs et al.14 which we view as a benchmark for predictive toxicokinetics in the early development zebrafish.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Auxiliary Models (Dynamic Volume, Surface Area, and Hatching)

To establish a dynamic volume model relevant for embryo morphogenesis, we used the average data found in a study by Simeon et al.,27 which describes the volume of both the embryo and yolk with apparent high precision and time resolution across the tested exposure duration. Of note, the degree of exposure-induced malformations, including altered length,32−34 is a function of PFAS concentration, but the literature has not thoroughly explored other important geometrical metrics, such as volume, which may vary as a function of PFAS exposure. To describe the Simeon et al.27 data set, we developed a system of first-order ordinary differential equations to model the time evolution of population-averaged tissue volumes. In essence, these differential equations were derived from a mass balance of the system with several assumptions (see graphical abstract for compartment spatial relationships): (1) there is a constant mass-transfer rate from the yolk to the embryo, (2) any loss in mass of the yolk is directly transferred to the embryo, (3) the yolk is the sole mass source of the embryo as the zebrafish is not fed during 0–120 hpf,35 (4) the chorion has a constant diameter before hatching as supported through image analysis,36−39 and (5) the yolk has a constant density but the embryo does not. Our volume model derivation is given in the Supporting Information.

Although volumetric information is required for a detailed PFAS mass balance, surface areas are required to estimate mass fluxes necessary to estimate tissue-specific accumulation. We developed a surface area model based on the Guo et al.40 data set, which can be found in the Supporting Information.

Moving on from dynamic volume and surface area, we also modeled the dynamic hatching of a population of developing zebrafish. Hatching is an individual transformative process with the kinetic rates underlying the biochemistry having some distribution, which leads to different hatching times across a population, on the order of about a day.32 As such, hatching is not instantaneous, and any population measurement (i.e., one that is a function of the hatched state) made after the first individual has hatched will reflect an average of the mixed state. This is especially important for the toxicokinetics discussed in this work as the presence or absence of the chorion (i.e., the development status of the population) greatly affects the mass transfer. In general, a mixed-state solution to a problem also solves the uniform population problem when it arises (i.e., the fraction of one state is set to zero). For our purposes, whenever the chorion is present (i.e., any natural hatching scenario), we have a mixed population, but for dechorionation, we have a uniform population. To account for hatching, we developed a hatching fraction model based on the Hagenaars et al.32 data set. Unlike our volume model, hatching fraction dependence on the PFAS concentration is recorded, but we did not consider this dependence due to simplicity and limited data. The hatching fraction model can be found in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Toxicokinetic Model Development

We adopted a compartment-based abstraction of the zebrafish embryo, in which PFAS transport across tissue or cell types can be modeled by a set of chemical “reactions” that regulate PFAS accumulation within each compartment. This approach reduces the complexity of molecular transport across different membrane barriers and biological fluids (e.g., blood, interstitial fluid, and cytosol) to a small set of kinetic rate constants. This simplicity comes at the cost of broad reductive assumptions. First, we assume the number of PFAS molecules is large enough that concentration fluctuations can be safely neglected. When tissue concentrations are small enough, this rate equation approach breaks down, and corrections are required.41 Second, we must acknowledge that a rate-limited deterministic chemical kinetics model allows for instantaneous molecular transport between cell and tissue types, which is unrealistic, even in principle. Despite these potential drawbacks, the rate equation approach has been employed before to model zebrafish embryo toxicokinetics. Specifically, we consider the model described by Vogs et al.14 (referred to hereon as the “Vogs model,” including citation) as a benchmark of predictive PFAS toxicokinetics in the early development zebrafish.

We obtained PFOA and PFOS data sets presented in the Vogs model and adopted their well-mixed two-compartment representation of chorion (subscript C) and embryo (subscript E). Here, “chorion” refers to the perivitelline space, and “embryo” refers to a combined compartment of both embryo and yolk tissues. This chorion/embryo system is exposed to a reservoir of constant aqueous PFAS concentration (subscript W). In the following model equations, we also use subscript X which can either be W or C depending on the hatched state.

Our model differs significantly from the Vogs model. First, we adjusted the mass balance of the system, treating the PFAS mass (or number of molecules) as a conserved quantity. This is appropriate as both a changing compartment volume and mass flux across a compartment lead to a change in the compartment concentration. In contrast, the Vogs model treats the PFAS concentration as a conserved quantity. As such, we converted the concentrations reported by the Vogs model back to original mass measurements by using a volume model described in a study by Brox et al.,28 which the Vogs model used for their calculations. Also, considering the bioaccumulation process of some PFAS and the lack of metabolism of PFOA and PFOS,42 we hypothesized that elimination rates are much smaller in value than those of absorption (uptake) and are thus negligible, which is consistent with the rate constants reported by the Vogs model.

One limitation of the Vogs model is that it relies on a different set of parameters for each PFAS exposure concentration. As such, there is no unified description of a physical process responsible for such a concentration dependence, leading to a lack of predictive capability in its present state. We found that saturable kinetics, as modeled with Michaelis–Menten kinetics, can describe this concentration dependence. Finally, we scaled mass fluxes to the growing surface area of the relevant fluid/fluid or tissue/fluid interface. A mass balance for the chorion is then

| 1 |

wherein C is the PFAS concentration (μM), V is the volume (L), A is the surface area (mm2), t is the time (h), k is the maximum kinetic rate constant between two locations (μmol/h/mm2), and K is a concentration for which the flux is half its maximum. As VC is known (governed by our established dynamic volume model), eq 1 is used to numerically solve for CC as a function of time.

Equation 1 describes the time evolution for accumulated PFAS concentrations within the chorion of an unhatched embryo. However, embryos will hatch over some time course as we have discussed with our hatching fraction model in the Auxiliary Models subsection. In the Vogs model, each measurement represents a homogenization of multiple zebrafish, meaning that each zebrafish could theoretically be in a different exposure state depending on when it hatched. We account for a mixed population of hatched and unhatched embryos by modeling the fraction of an embryo population that has hatched at a given time. As a result, the chorion mass contribution for a given measurement is directly modulated by the hatched fraction and can be expressed as

| 2 |

wherein Mmeas refers to the mass measurement (μmol) and h is the fraction of hatched embryos.

For the embryo compartment, this hatching phenomenon needs to be reflected at the mass balance level because it receives two different fluxes: one from the reservoir and another from the chorion. Both fluxes change over time and are dependent upon the hatched state of the population. We address this problem by writing a mass balance for the average change in mass of the embryo compartment

| 3 |

wherein Cavg labels a population-averaged PFAS concentration. Here, we have assumed that individual embryos are independent, identical copies distributed across the hatched or unhatched states, with their volume governed by our established dynamic volume model. The embryo mass contribution to a given measurement can, therefore, be calculated as

| 4 |

once eq 3 is used to numerically solve for CEavg as a function of time. Equations 2 and 4 can then be added together and compared against the Vogs model data for parameter fitting.

2.3. Modeling Membrane Transport and PFAS Adsorption/Binding Processes

Common practice in toxicokinetic modeling is to abstract the toxicant mass-transfer process across biological compartments into that of reaction-limited chemical kinetics. However, this approach neglects the underlying mechanisms (e.g., diffusive flux processes) responsible for the evolution of a compartment’s toxicant concentration. For many substances, this phenomenological-based abstraction is adequate. However, PFAS exhibit complicated molecular conformations (e.g., micelle formation), and because they are amphiphilic, they exhibit unique interactions with biological structures such as lipid membranes and proteins. We hypothesize that these nontrivial interactions require a more mechanistic modeling approach to better capture and understand the toxicant mass transfer. To test this hypothesis, we adjusted the mathematical framework described above by considering PFAS diffusion across the chorion (a membrane) and outer embryo membrane (i.e., abstracting the embryo boundary as a single membrane and the only resistance to mass transfer, such as the apical membrane of an epithelium) as rate-limiting PFAS transport mechanisms, in addition to PFAS adsorption/binding events within each compartment.

We tested a model of simple diffusion across the boundaries of both compartments (i.e., the mass flux across either the chorion or embryo membrane is only governed by a constant permeability and a concentration gradient), which did not fit the data well at any time. At early times, if simple diffusion dominated the physics, we would expect the mass flux to be proportional to the concentration gradient, and the absence of this lends credence to the idea that PFAS molecules may interact with membrane transport proteins that can become saturated. This results in a nonlinear concentration dependence of the mass flux, and we hypothesize that membrane transporters, such as organic anion transporters, interact with and limit PFAS transport across membranes. This idea is justified on the basis that membrane transporters are generally important in pharmacokinetics43−45 and PFAS toxicokinetics.46,47 Perhaps one of the simplest representations of carrier-mediated transport is that of Kolber and LeFevre,48 wherein a solute–carrier complex forms and diffuses across the membrane, and due to the finite number of carriers, the transport flux rises with solute concentration until all carriers are bound.

In the literature, zebrafish-relevant reports span a number of diverse adsorption/binding events, from nanoparticles49,50 to PFAS,51−53 and the data directly support the presence of such events as we observed gross underestimation of system mass at long times for our simple diffusion model. Our consideration of adsorption/binding mechanisms assumes diffusion-limited transport across membranes. In conjunction, we identified the simplest adsorption/binding model consistent with the data (i.e., number of parameters), which led to the use of a linear isotherm to describe the general sum of adsorption (or partitioning) to lipid membrane surfaces and binding to other structures (e.g., proteins) within each compartment. As such, we developed a simplified representation of transporters moving PFAS across the membrane boundary of a compartment followed by the instantaneous adsorption/binding of the PFAS to structures within the compartment, of which the potential adsorption to the membrane does not influence the number of available transporters.

As with our previous model formulation, we estimate the mass contribution of the chorion outside of its mass balance (i.e., h appears in the mass contribution equation rather than the mass balance, see eqs 1 and 2), but we must consider a mass balance for unhatched embryos. We assume that PFAS fluxes across the system membranes are driven by concentration gradients; therefore, fluxes associated with unhatched embryos require an embryo concentration term. Additionally, we describe two PFAS phases for each compartment: the phase in free solution (superscript f) and the phase bound to biological structures (superscript b). The relevant mass balance for the chorion is

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

Here, the subscript un refers to the unhatched embryos, M is the mass, Kads is the parameter associated with adsorption/binding affinity (L), Ksc is the constant of the solute–carrier complex (μM), and k now represents the constant of diffusional transport across the membranes between two locations (μmol × μM/h/mm2). The chorion mass contribution to a given measurement can, therefore, be expressed as:

| 9 |

For the embryo compartment, we again incorporate a two-phase representation of PFAS

| 10 |

| 11 |

The embryo mass contribution to a given measurement is then

| 12 |

2.4. Model Training and Parameter Identification

We employed a curve-fitting methodology to identify model parameters for both model forms considered. Parameter values minimize a modified least squares objective functional developed with data leveraged from those described by the Vogs model. Details of the fitting procedure are provided in the Supporting Information.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Empirical Assessment of Model Performance

Auxiliary models developed to support the toxicokinetic models (i.e., dynamic volume, surface area, and hatching) exhibit good qualitative agreement with data in all cases (R2 > 0.97, see Figure S1). The R2 for all toxicokinetic models (model code found in Supporting Information) using the calibration data is > 0.96, with slightly higher fidelity exhibited by models that incorporate PFAS transporters and adsorption/binding. Other goodness of fit metrics, such as the RMSE, show similar results. Thus, a higher level of mechanistic detail seems to improve the description of PFAS toxicokinetics in conjunction with providing a much deeper mass-transfer understanding, albeit at the cost of two additional parameters. From a solely information metric perspective, the Akaike Information Criterion bias-corrected for small sample sizes (AICc) justifies the two additional parameters for PFOA but not for PFOS, but the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) justifies the two additional parameters for both PFOA and PFOS.54 All model fits are presented in Figure S2 (including all goodness of fit and information metrics), as well as our replication of the Vogs model. Also, the Vogs model equations and parameters (see Table S2) are compiled in the Supporting Information.

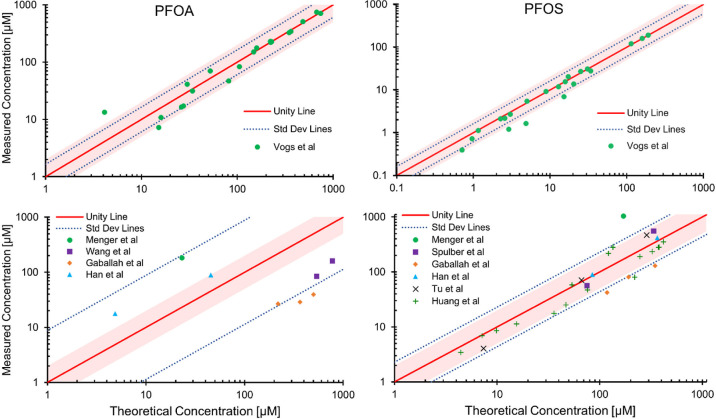

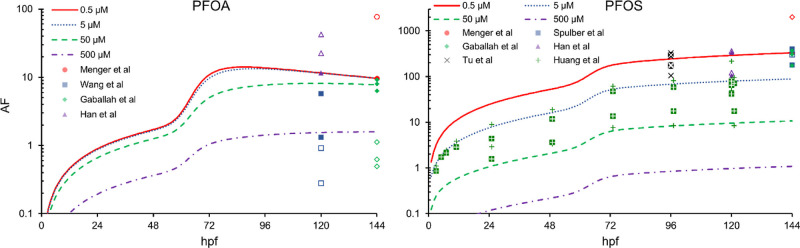

In Figure 1, we present the transporter and adsorption/binding model (referred to hereon as the “transporter model”) fits in a parity plot form for both the Vogs model data and other data found in the literature with no experimental setup restrictions.16,42,55−59 As expected, the Vogs model data, which we used for calibration, cluster around the unity line more so than the other data found in the literature (evaluation data), as can be seen by a difference in the calculated standard deviation of the data about the unity line (i.e., the scaling factor of the data from unity). The area bounded by a factor of 2 from unity is shaded, and ideally, as reported by the International Programme on Chemical Safety,60 toxicokinetic models should generally yield estimates within a factor of 2 of the data if they are to be used in risk assessment. Overall, for the Vogs model data comparison, we see that 90.0% and 85.7% of the data fall within a factor of 2 for PFOA and PFOS, respectively. For the comparison against the broader literature, 12.5% and 71.4% of data fall within a factor of 2 for PFOA and PFOS, respectively. It is not entirely clear why the PFOA data are so variable in comparison to PFOS, but we compare (see Table S3) and comment on some differences between the experimental studies in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Parity plot presentation of the transporter model predictions against that of both the Vogs model data and other data available in the literature16,42,55−59 (incorporating both pre- and post-hatching phases) for the chorion/embryo system in the concentration domain. When necessary, data were converted to a mass/zebrafish basis before being converted to a concentration basis using our proposed volume model. We assumed a wet weight of 500 μg58,59 for the Han et al.42 conversion. The shaded region indicates an area bounded by a factor of 2 from unity, and the standard deviation lines of the data from unity are included.

3.2. Hatching Significantly Affects PFAS Toxicokinetics

The Vogs model suggests that it is important to model the chorion due to its role as a mass-transfer barrier. Although the chorion is, indeed, a physical barrier to PFAS flux into the embryo, it is not clear whether it is also a rate-limiting step for PFAS toxicokinetics or accumulation within embryo tissues. To justify inclusion of the chorion, the Vogs model points to a dynamic, biphasic PFAS uptake pattern, as demonstrated by an increased PFAS accumulation in the period just after hatching, which suggests a net-positive uptake rate for embryos without their chorion. However, our reanalysis of these data does not support a definitive conclusion regarding a biphasic pattern in the data (see Figure S3). In particular, it is difficult to distinguish positive or negative trends from fluctuations in data, which is not unusual given a limited number of data points, especially considering that net uptake is a derived measurement (numerical derivative) from the internal mass measurement. Given limitations in the data, a modeling argument should be made to support claims of biphasic uptake.

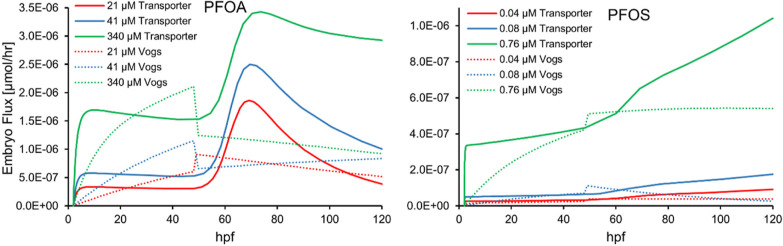

In Figure 2, we show our model results for embryo flux (net uptake) compared to those of the Vogs model. In contrast to our model, wherein we show a distinct increase in PFAS accumulation around the hatching transition for all exposure conditions, the Vogs model does not, instead predicting an abrupt decrease in embryo accumulation once chorions are shed for some conditions. This stark, qualitative difference in predictions can, perhaps, be traced back to how each approach incorporates hatching. Hatching is, approximately, an abrupt physiological change for an individual zebrafish embryo, but the onset of individual hatching can vary over many hours. At the population level, this leads to a situation where some embryos have hatched while others have not, and since PFAS accumulation is measured based on the homogenate of multiple individuals, chorionated individuals will contribute less PFAS accumulation than dechorionated ones. In our transporter model, this imbalance can most readily be seen for PFOA, where a distinct increase in accumulation for the population begins at the onset of hatching and continues as the hatched fraction increases. In contrast, the hatching transition of the Vogs model treats all individuals identically, and a population average therefore adopts the abrupt transitional symmetry of the individual hatching event. Thus, our transporter model predicts a longer timescale to resolve the long-term behavior of the system after hatching. For example, at the end of the hatching period for PFOA, we begin to see a decrease in the embryo flux in contrast with PFOS. This is due to the greater bioaccumulation potential of PFOS (as evident from parameter differences such as the adsorption/binding constant in Table S1), while PFOA begins to approach chemical equilibrium for lower exposure concentrations, as discussed later.

Figure 2.

Transporter model results for embryo PFAS net uptake (flux) compared against that of the Vogs model. Fluxes from the Vogs model were estimated by multiplying their change in the concentration and volume predictions.

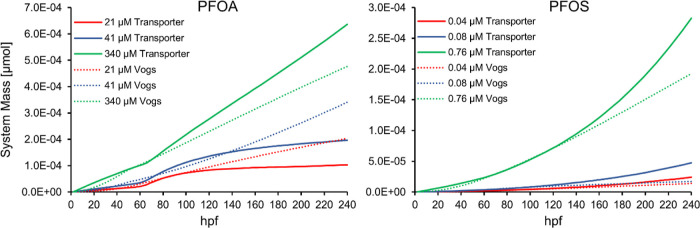

The “Vogs model” is not a single predictive model, but rather a set of models, each with kinetic parameters specific to a tested exposure condition. Unfortunately, this constrains the ability of the Vogs model to interpolate between measured data and to extrapolate beyond fitted conditions of exposure and duration. As shown in Figure 3, we extrapolate model predictions (including volume) past 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) to that of 10 dpf. In the Vogs model, PFOA and PFOS exhibit a roughly constant accumulation beyond the hatching event, where a constant uptake flux dominates over the elimination flux, resulting in a relationship for PFAS mass that is approximately linear in the exposure duration. However, our transporter model predicts that lower concentration exposures of PFOA will approach chemical equilibrium after approximately 5 dpf. This steady state is something that the Vogs model cannot predict with constant PFAS accumulation at a given exposure concentration; thus, its fidelity for extrapolation is greatly reduced. The nonlinear accumulation characteristics predicted by our transporter model begs further investigation of PFAS bioaccumulation as we expect PFAS with higher bioconcentration factor (BCF) values (e.g., PFOS) to rapidly accumulate as fluid phase concentrations increase (as captured in our model) but limited by the number of adsorption/binding sites that emerge as the fish matures. The ability to capture such long-term behavior as chemical equilibrium and potential accelerated accumulation puts our model in the unique position for full life cycle fish studies.

Figure 3.

Transporter model results compared against that of the Vogs model for chorion/embryo system mass after extrapolating all models past 5 dpf to 10 dpf for three different exposure concentrations.

Overall, our hatching representation provides a rigorous way to deal with the shedding of the chorion from a population of fish either in the laboratory or environmental setting. With this basis, we can address any setting where the chorion is or is not present. For instance, as shown in Figure S4, we compare transporter model predictions for the chorion and dechorionated cases. We see that the chorion acts as a barrier to mass transfer (as shown before in our biphasic uptake discussion) since a greater uptake is seen for the dechorionated cases, resulting in greater system mass. Also, these model predictions indicate that these PFAS have a greater affinity for the embryo over the chorion. If these PFAS had a greater affinity for the chorion over the embryo, we would see the chorion curves show a greater mass than those of the dechorionated curves. In conjunction, if the affinity for the chorion was dominant, we would also see a decline in system mass in the Vogs model data set after the hatching event. We do not see this, which is different than the results reported by Brox et al.61 for other compounds outside of PFAS (e.g., clofibric acid and mitribuzin), where greater chorion affinity and a decrease in mass after hatching is observed, which points to the chorion acting as more of a mass sink for these compounds. As such, if the mass-transfer role of the chorion can be characterized, such as with our modeling framework, the need for laboratory dechorionation is eliminated. The internal concentration responsible for a given MIE as a function of the exposure concentration and time can always be deduced, regardless of the presence of the chorion.

In Figure S5, we show a compartment-by-compartment analysis of both PFOA and PFOS mass in each phase represented by our transporter model. Given the bioaccumulative nature of some PFAS, we see how the majority of PFAS mass resides in the embryo bound phase. Such a result aligns with the conclusion that the chorion is more of a mass-transfer barrier rather than sink for the PFAS investigated. Also, for PFOS, we see a greater percentage of system mass reside in the bound embryo phase compared to that of PFOA. This result highlights the BCF difference between the two PFAS as will be discussed later but also speaks to the much greater toxicity of PFOS when considering the same toxic effect,14 perhaps due to a much greater adsorption/binding potential.

Regardless of chorion versus embryo affinity, the chorion acts as a mass-transfer barrier and mass sink, with one phenomenon having the ability to be dominant depending on the chemical of interest. Overall, the parameters of our model (i.e., adsorption/binding constants) can be tuned to account for either barrier or sink dominant situations, allowing our model to be extended beyond PFAS applications. Furthermore, our proposed model provides a more physiologically relevant framework for not only developing zebrafish in the laboratory that could be dechorionated but also fish that hatch naturally in the environment.

3.3. PFAS Bioconcentration in a Population of Growing Embryos

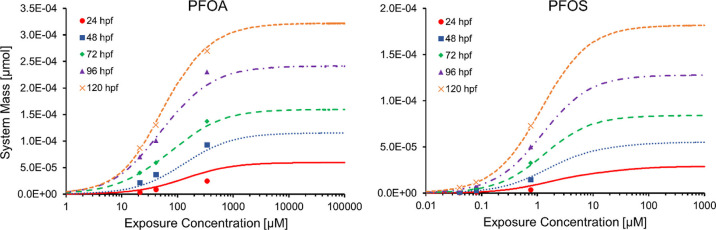

Figure 4 illustrates the exposure concentration–response curves for both PFOA and PFOS, as calculated from our transporter model and compared against exposure data reported by the Vogs model. In the transporter model, sigmoid concentration dependence of the relevant transfer fluxes model a PFAS fluid and bound phase phenomenology that manifests with a concentration–response curve that is insensitive to higher PFAS exposures. Here, a competition between PFAS influx/efflux predicts thresholds of insensitivity on the order of 1000 μM and 100 μM for PFOA and PFOS, respectively. Future experiments can test these predictions, and discrepancies could point to transporter and/or membrane integrity disruption not accounted for in our model, in conjunction with a breakdown of the infinite adsorption/binding site assumption used here. Furthermore, more data could motivate more complicated adsorption/binding kinetic and isotherm models that capture the nuance of long-range electrodynamic interactions between polar PFAS molecules and the tissue environments.

Figure 4.

Chorion/embryo system PFAS mass expressed over a range of exposure concentrations and times predicted using our transporter model (curves). Vogs model data are shown with symbols.

Our model can also be used to investigate both the temporal and concentration dependence of a PFAS accumulation factor (AF). Here, we define the AF to be a time-dependent quantity that is mathematically synonymous with the BCF, but we avoid referring to the AF as the BCF, as the BCF is normally defined around chemical equilibrium (i.e., a time-independent quantity). The AF encodes important information that is relevant for the MIEs of AOPs that begin well before chemical equilibrium is reached, and the literature also provides some single AF (referred in the references as BCF) values for the early development zebrafish not at chemical equilibrium.14,42Figure 5 illustrates that the time evolution of the AF tracks that of system mass (which is requisite considering the definition of the AF), highlighting the need to exercise caution when interpreting BCFs reported in the literature for just a single time point not at chemical equilibrium. Shown here are AF predictions at several different exposure concentrations, contrasted against values reported or derived from the literature.16,42,55−59 As Figure 5 shows, and as Chen et al.62 discussed for long-chain PFAS, BCFs can decrease as the exposure concentration increases, which is consistent with our model that incorporates PFAS adsorption/binding and saturable membrane transport.

Figure 5.

Our transporter model predicts some nonmonotonic AF profiles that evolve over time (curves), illustrated here for several different constant exposure concentrations. Here, we calculate AF as the ratio of the chorion/embryo system concentration to that of the constant exposure concentration. AF data (open symbols) reported or derived from the literature16,42,55−59 are also shown with a similar calculation strategy as with Figure 1. Closed symbols (as depicted in the legend) represent our model predictions for those same data points, whereby giving a sense for the magnitude of the literature exposure concentrations and our model’s fidelity with the literature in the AF domain.

Figure 5 shows that AF predictions for PFOS can be up to about an order of magnitude larger than AF predictions for PFOA, consistent with other studies that present an AF (referred in the references as BCF) at 120 hpf.14,42 As the Vogs model suggests, internal concentrations of several PFAS are a better predictor of AOs than exposure concentrations. With respect to the AOP framework, internal concentrations are relevant at the level of the MIE, which is correlated to an AO via biological KEs. Thus, if two chemicals act through the same AOP, then knowledge of the whole AF profile could improve or refine the fidelity of the toxicity prediction. Even if two chemicals do not act through the same AOP, knowledge of the whole AF profile can still provide some toxicokinetic learnings separate from being used as an input into two different AOPs. As an example, long-time behavior of the PFOA AF is nonmonotonic for lower exposure concentrations, where it decreases from shortly after the hatching event to the end of the exposure experiment. We hypothesize that for smaller exposure concentrations, an increase in volume of the developing zebrafish dominates the PFOA flux into the zebrafish, acting to dilute tissue concentrations and decrease the AF. Since environmental exposures are much lower than that used in most studies, the physiology of the embryo, such as tissue growth, could play a much larger role in the toxicokinetics when compared to the flux of a chemical into the organism.

Overall, our proposed modeling framework provides a solid foundation for the continuing evolution of toxicokinetic modeling of PFAS in zebrafish by addressing the rigor of system volume changes, hatching, and mass transfer. Given the generality of these modeled phenomena, we could potentially apply this model to embryos of other fish species and potentially to a larger number of chemicals or chemical classes given data availability. As AOP development and qAOP modeling become more prevalent, it becomes more of a necessity to capture as much physiological detail and as many specific chemical transport mechanisms and interactions as possible to provide a reasonable internal concentration estimate at the level of the MIE. As such, future toxicokinetics steps would include adding more compartments to the model to allow more MIEs to be addressed that require more spatial resolution, as well as extending the timeline that the model covers, which would need to include new uptake (and perhaps elimination) mechanisms as the physiology progresses.52,63,64 In the literature, it has been shown that separating yolk from embryo greatly increases the accuracy of embryo concentration predictions,65 and such a simple separation can also shed light on AOs that would require enhanced modeling fidelity to distinguish yolk from embryo tissues.66 Ideally, radiolabeling67 and tomography could be used to track the PFAS temporal and spatial distribution across the lifespan of a zebrafish and generate multi-compartment data to support improved model development.

For our future qAOP model, we propose an approach that includes modular “response–response” KE linkages, potentially as described by Foran et al.68 and Song et al.,69 yet also models the mean and variance of a response across a population experiencing a MIE, KE, or AO (in a similar vein to the multistate model of Simeon et al.70). More precisely, we propose that Bayesian networks71 can parameterize statistical distributions that capture relationships between the MIE, KEs, and AO that are conditioned over a wide range of PFOA exposure concentrations. Thus, we anticipate that suitable application of Bayes’ theorem to every linkage of the AOP will produce conditional distributions that are chemically agnostic, making the final model relevant to a wide range of PFAS and other compounds. We believe that the free solution PFOA concentration predicted by our transporter model is an appropriate concentration to use for predicting the activation of the MIE (the qAOP model input) for our AOP case study.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through the Department of Defense (DOD), Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, Applied Research for the Advancement of Science and Technology priorities PE #0602251D8Z, and an appointment to the DOD Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the DOD. ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under DOE contract number DE-SC0014664. Furthermore, Dr. Sweeney is a contractor working with the Air Force Research Laboratory. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official guidance or position of the United States Government, DOD, DOE, the United States Air Force, the US Army Corps of Engineers, ORAU/ORISE, or UES, Inc.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c02942.

Modeling descriptions of the volume, embryo surface area, and hatched fraction models; fitting procedure for the toxicokinetic models; Vogs model equations; experimental differences between the literature studies used for data; parameters used for all models derived in this work, parameters for the Vogs model, and compiled experimental differences of the literature studies used for data; models fits, biphasic uptake discussion, chorion intact versus dechorionated comparison, and compartment-by-compartment mass distribution investigation; and modeling code for both the kinetic and transporter toxicokinetic models (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Post G. B.; Gleason J. A.; Cooper K. R. Key scientific issues in developing drinking water guidelines for perfluoroalkyl acids: contaminants of emerging concern. Plos Biology 2017, 15, e2002855 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves A. K.; Letcher R. J.; Sonne C.; Dietz R.; Born E. W. Tissue-specific concentrations and patterns of perfluoroalkyl carboxylates and sulfonates in east greenland polar bears. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11575–11583. 10.1021/es303400f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian J. M.; Guo Y.; Zeng L. X.; Liang-Ying L. Y.; Lu X. W.; Wang F.; Zeng E. Y. Global distribution of perfluorochemicals (PFCs) in potential human exposure source-a review. Environ. Int. 2017, 108, 51–62. 10.1016/j.envint.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chohan A.; Petaway H.; Rivera-Diaz V.; Day A.; Colaianni O.; Keramati M. Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances scientific literature review: water exposure, impact on human health, and implications for regulatory reform. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 36, 235–259. 10.1515/reveh-2020-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton S. E.; Ducatman A.; Boobis A.; DeWitt J. C.; Lau C.; Ng C.; Smith J. S.; Roberts S. M. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 606–630. 10.1002/etc.4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker C.; Luster M. I.; Calafat A. M.; Johnson V. J.; Burleson G. R.; Burleson F. G.; Fletcher T. Influenza vaccine response in adults exposed to perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctanesulfonate. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 138, 76–88. 10.1093/toxsci/kft269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P.; Heilmann C.; Weihe P.; Nielsen F.; Mogensen U. B.; Timmermann A.; Budtz-Jørgensen E. Estimated exposures to perfluorinated compounds in infancy predict attenuated vaccine antibody concentrations at age 5-years. J. Immunotoxicol. 2017, 14, 188–195. 10.1080/1547691x.2017.1360968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P.; Timmermann C. A. G.; Kruse M.; Nielsen F.; Vinholt P. J.; Boding L.; Heilmann C.; Mølbak K. Severity of COVID-19 at elevated exposure to perfluorinated alkylates. Plos One 2020, 15, e0244815 10.1371/journal.pone.0244815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS Master List of PFAS Substances, 2021, https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical-lists/pfasmaster, (accessed December 8, 2021).

- Hoover G.; Kar S.; Guffey S.; Leszczynski J.; Sepúlveda M. S. In vitro and in silico modeling of perfluoroalkyl substances mixture toxicity in an amphibian fibroblast cell line. Chemosphere 2019, 233, 25–33. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn R. W.; Chislock M. F.; Gannon M. E.; Bauer S. J.; Tornabene B. J.; Hoverman J. T.; Sepúlveda M. S. Acute and chronic effects of perfluoroalkyl substance mixtures on larval American bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana). Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124350. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy C. J.; Roark S. A.; Middleton E. T. Considerations for toxicity experiments and risk assessments with PFAS mixtures. Integr. Environ. Assess. 2021, 17, 697–704. 10.1002/ieam.4415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal T.; Vogs C.. Invited perspective: PFAS bioconcentration and biotransformation in early life stage zebrafish and its implications for human health protection. Environmental Health Perspectives; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, 2021, 129( (7), ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vogs C.; Johanson G.; Näslund M.; Wulff S.; Sjödin M.; Hellstrandh M.; Lindberg J.; Wincent E. Toxicokinetics of perfluorinated alkyl acids influences their toxic potency in the zebrafish embryo (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3898–3907. 10.1021/acs.est.8b07188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaee M.; Ng C. A. Evaluating parameter availability for physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in zebrafish. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 2018, 20, 105–119. 10.1039/c7em00474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. H.; Huang C. J.; Wang L. J.; Ye X. W.; Bai C. L.; Simonich M. T.; Tanguay R. L.; Dong Q. X. Toxicity, uptake kinetics and behavior assessment in zebrafish embryos following exposure to perfluorooctanesulphonicacid (PFOS). Aquat. Toxicol. 2010, 98, 139–147. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. J.; Zhao Y.; Ji Z. X.; Ear J.; Chang C. H.; Zhang H. Y.; Low-Kam C.; Yamada K.; Meng H.; Wang X.; Liu R.; Pokhrel S.; Mädler L.; Damoiseaux R.; Xia T.; Godwin H. A.; Lin S.; Nel A. E. Zebrafish high-throughput screening to study the impact of dissolvable metal oxide nanoparticles on the hatching enzyme, ZHE1. Small 2013, 9, 1776–1785. 10.1002/smll.201202128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S.; Marigliani B.; Akgün-Ölmez S. G.; Ireland D.; Cruz R.; Busquet F.; Flick B.; Lalu M.; Ghandakly E. C.; de Vries R. B. M.; Witters H.; Wright R. A.; Ölmez M.; Willett C.; Hartung T.; Stephens M. L.; Tsaioun K. A systematic review to compare chemical hazard predictions of the zebrafish embryotoxicity test with mammalian prenatal developmental toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2021, 183, 14–35. 10.1093/toxsci/kfab072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley G. T.; Bennett R. S.; Erickson R. J.; Hoff D. J.; Hornung M. W.; Johnson R. D.; Mount D. R.; Nichols J. W.; Russom C. L.; Schmieder P. K.; Serrrano J. A.; Tietge J. E.; Villeneuve D. L. Adverse outcome pathways: a conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 730–741. 10.1002/etc.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve D.; Volz D. C.; Embry M. R.; Ankley G. T.; Belanger S. E.; Léonard M.; Schirmer K.; Tanguay R.; Truong L.; Wehmas L. Investigating alternatives to the fish early-life stage test: a strategy for discovering and annotating adverse outcome pathways for early fish development. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 158–169. 10.1002/etc.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve D. L.; Angrish M. M.; Fortin M. C.; Katsiadaki I.; Leonard M.; Margiotta-Casaluci L.; Munn S.; O’Brien J. M.; Pollesch N. L.; Smith L. C.; Zhang X. W.; Knapen D. Adverse outcome pathway networks II: network analytics. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 1734–1748. 10.1002/etc.4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapen D.; Angrish M. M.; Fortin M. C.; Katsiadaki I.; Leonard M.; Margiotta-Casaluci L.; Munn S.; O’Brien J. M.; Pollesch N.; Smith L. C.; Zhang X. W.; Villeneuve D. L. Adverse outcome pathway networks I: development and applications. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 1723–1733. 10.1002/etc.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapen D.; Stinckens E.; Cavallin J. E.; Ankley G. T.; Holbech H.; Villeneuve D. L.; Vergauwen L. Toward an AOP network-based tiered testing strategy for the assessment of thyroid hormone disruption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8491–8499. 10.1021/acs.est.9b07205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinckens E.; Vergauwen L.; Ankley G. T.; Blust R.; Darras V. M.; Villeneuve D. L.; Witters H.; Volz D. C.; Knapen D. An AOP-based alternative testing strategy to predict the impact of thyroid hormone disruption on swim bladder inflation in zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 200, 1–12. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Price A.; Lein P. J.; Keil K. P.; Sethi S.; Shafer T.; Barenys M.; Fritsche E.; Sachana M.; Meek M. E. B. Developing and applying the adverse outcome pathway concept for understanding and predicting neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2017, 59, 240–255. 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell H. J.; Yager J. W.; Greene T. B.; Gentry P. R. Application of the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) approach to inform mode of action (MOA): a case study with inorganic arsenic. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A 2018, 81, 893–912. 10.1080/15287394.2018.1500326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siméon S.; Brotzmann K.; Fisher C.; Gardner I.; Silvester S.; Maclennan R.; Walker P.; Braunbeck T.; Bois F. Y. Development of a generic zebrafish embryo PBPK model and application to the developmental toxicity assessment of valproic acid analogs. Reprod. Toxicol. 2020, 93, 219–229. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brox S.; Seiwert B.; Küster E.; Reemtsma T. Toxicokinetics of polar chemicals in zebrafish embryo (Danio rerio): influence of physicochemical properties and of biological processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10264–10272. 10.1021/acs.est.6b04325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnert A.; Vogs C.; Altenburger R.; Küster E. The internal concentration of organic substances in fish embryos—a toxicokinetic approach. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 1819–1827. 10.1002/etc.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirla K. T.; Groh K. J.; Steuer A. E.; Poetzsch M.; Banote R. K.; Stadnicka-Michalak J.; Eggen R. I. L.; Schirmer K.; Kraemer T. Zebrafish larvae are insensitive to stimulation by cocaine: importance of exposure route and toxicokinetics. Toxicol. Sci. 2016, 154, 183–193. 10.1093/toxsci/kfw156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massei R.; Vogs C.; Renner P.; Altenburger R.; Scholz S. Differential sensitivity in embryonic stages of the zebrafish (Danio rerio): The role of toxicokinetics for stage-specific susceptibility for azinphos-methyl lethal effects. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 166, 36–41. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars A.; Vergauwen L.; De Coen W.; Knapen D. Structure-activity relationship assessment of four perfluorinated chemicals using a prolonged zebrafish early life stage test. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 764–772. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars A.; Stinckens E.; Vergauwen L.; Bervoets L.; Knapen D. PFOS affects posterior swim bladder chamber inflation and swimming performance of zebrafish larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 157, 225–235. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Du Y.; Lam P. K.; Wu R. S.; Zhou B. Developmental toxicity and alteration of gene expression in zebrafish embryos exposed to PFOS. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 230, 23–32. 10.1016/j.taap.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD Test No . Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2006, 2362013.

- Yang Y.; Tang T. L.; Chen Y. W.; Tang W. H.; Yang F. The role of chorion around embryos in toxic effects of bisphenol AF exposure on embryonic zebrafish (Danio rerio) development. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2020, 233, 106540. 10.1016/j.ecss.2019.106540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C. T.; Patinote A.; Guiguen Y.; Bobe J. foxr1 is a novel maternal-effect gene in fish that is required for early embryonic success. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5534 10.7717/peerj.5534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. H.; Huang K. S.; Liou Y. M. Simultaneous monitoring of oxygen consumption and acidification rates of a single zebrafish embryo during embryonic development within a microfluidic device. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2017, 21, 3. 10.1007/s10404-016-1841-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B.; Ballard W. W.; Kimmel S. R.; Ullmann B.; Schilling T. F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 203, 253–310. 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Veneman W. J.; Spaink H. P.; Verbeek F. J. Three-dimensional reconstruction and measurements of zebrafish larvae from high-throughput axial-view in vivo imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 2611–2634. 10.1364/BOE.8.002611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grima R. An effective rate equation approach to reaction kinetics in small volumes: theory and application to biochemical reactions in nonequilibrium steady-state conditions. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 035101. 10.1063/1.3454685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Gu W.; Barrett H.; Yang D.; Tang S.; Sun J.; Liu J.; Krause H. M.; Houck K. A.; Peng H. A roadmap to the structure-related metabolism pathways of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the early life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 77004. 10.1289/EHP7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen C. D.; Aleksunes L. M. Xenobiotic, bile acid, and cholesterol transporters: function and regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 1–96. 10.1124/pr.109.002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaïr Z. M.; Eloranta J. J.; Stieger B.; Kullak-Ublick G. A. Pharmacogenetics of OATP (SLC21/SLCO), OAT and OCT (SLC22) and PEPT (SLC15) transporters in the intestine, liver and kidney. Pharmacogenomics 2008, 9, 597–624. 10.2217/14622416.9.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S.; Alcorn J. Xenobiotic transporter expression and function in the human mammary gland. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2003, 55, 653–665. 10.1016/s0169-409x(03)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Y. M.; Ehresman D. J.; Butenhoff J. L.; Hagenbuch B. Roles of rat renal organic anion transporters in transporting perfluorinated carboxylates with different chain lengths. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 113, 305–314. 10.1093/toxsci/kfp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Zitzow J. D.; Weaver Y.; Ehresman D. J.; Chang S. C.; Butenhoff J. L.; Hagenbuch B. Organic anion transporting polypeptides contribute to the disposition of perfluoroalkyl acids in humans and rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 84–95. 10.1093/toxsci/kfw236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolber A. R.; LeFevre P. G. Evidence for carrier-mediated transport of monosaccharides in the Ehrlich Ascites tumor cell. J. Gen. Physiol. 1967, 50, 1907–1928. 10.1085/jgp.50.7.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann B. W.; Beijk W. F.; Vlieg R. C.; van Noort S. J. T.; Mejia J.; Colaux J. L.; Lucas S.; Lamers G.; Peijnenburg W.; Vijver M. G. Adsorption of titanium dioxide nanoparticles onto zebrafish eggs affects colonizing microbiota. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 232, 105744. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2021.105744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Y. J.; Su C. C.; Chen C. W.; Dong C. D.; Liu W. S.; Huang C. P. Adsorption characteristics of nano-TiO2 onto zebrafish embryos and its impacts on egg hatching. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 109–117. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droge S. T. J. Membrane-water partition coefficients to aid risk assessment of perfluoroalkyl anions and alkyl sulfates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 760–770. 10.1021/acs.est.8b05052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng C. A.; Hungerbühler K. Bioconcentration of perfluorinated alkyl acids: how important is specific binding?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7214–7223. 10.1021/es400981a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng C. A.; Hungerbühler K. Bioaccumulation of perfluorinated alkyl acids: observations and models. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4637–4648. 10.1021/es404008g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiess A. N.; Neumeyer N. An evaluation of R2 as an inadequate measure for nonlinear models in pharmacological and biochemical research: a monte carlo approach. BMC Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 6. 10.1186/1471-2210-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menger F.; Pohl J.; Ahrens L.; Carlsson G.; Örn S. Behavioural effects and bioconcentration of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125573. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. X.; Shi G. H.; Yao J. Z.; Sheng N.; Cui R. N.; Su Z. B.; Guo Y.; Dai J. Y. Perfluoropolyether carboxylic acids (novel alternatives to PFOA) impair zebrafish posterior swim bladder development via thyroid hormone disruption. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105317. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaballah S.; Swank A.; Sobus J. R.; Howey X. M.; Schmid J.; Catron T.; McCord J.; Hines E.; Strynar M.; Tal T. Evaluation of developmental toxicity, developmental neurotoxicity, and tissue dose in zebrafish exposed to GenX and other PFAS. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 5843. 10.1289/EHP5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spulber S.; Kilian P.; Wan Ibrahim W. N. W.; Onishchenko N.; Ulhaq M.; Norrgren L.; Negri S.; Di Tuccio M.; Ceccatelli S. PFOS induces behavioral alterations, including spontaneous hyperactivity that Is corrected by dexamfetamine in zebrafish larvae. Plos One 2014, 9, e0094227 10.1371/journal.pone.0094227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu W. Q.; Martínez R.; Navarro-Martin L.; Kostyniuk D. J.; Hum C.; Huang J.; Deng M.; Jin Y. X.; Chan H. M.; Mennigen J. A. Bioconcentration and metabolic effects of emerging PFOS alternatives in developing zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13427–13439. 10.1021/acs.est.9b03820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in risk assessment; IPCS Harmonization Project Document No. Vol. 9: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Brox S.; Ritter A. P.; Küster E.; Reemtsma T. Influence of the perivitelline space on the quantification of internal concentrations of chemicals in eggs of zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 157, 134–140. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. F.; Gong Z. Y.; Kelly B. C. Bioavailability and bioconcentration potential of perfluoroalkyl-phosphinic and -phosphonic acids in zebrafish (Danio rerio): comparison to perfluorocarboxylates and perfluorosulfonates. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 33–41. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péry A. R. R.; Devillers J.; Brochot C.; Mombelli E.; Palluel O.; Piccini B.; Brion F.; Beaudouin R. A physiologically based toxicokinetic model for the zebrafish Danio rerio. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 781–790. 10.1021/es404301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W.; Ng C. A. A permeability-limited physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in male rats. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 9930–9939. 10.1021/acs.est.7b02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach K.; Ulrich N.; Goss K. U.; Seiwert B.; Wagner S.; Scholz S.; Luckenbach T.; Bauer C.; Schweiger N.; Reemtsma T. Yolk sac of zebrafish embryos as backpack for chemicals?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10159–10169. 10.1021/acs.est.0c02068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S.; Reddam A.; Liu Z. K.; Liu J. Y.; Volz D. C. High-content screening in zebrafish identifies perfluorooctanesulfonamide as a potent developmental toxicant. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113550. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels J. L.; Fernandez S. R.; Aweda T. A.; Alford A.; Peaslee G. F.; Garbow J. R.; Lapi S. E. Comparative uptake and biological distribution of [18F]-labeled C6 and C8 perfluorinated alkyl substances in pregnant mice via different routes of administration. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 665–671. 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foran C. M.; Rycroft T.; Keisler J.; Perkins E. J.; Linkov I.; Garcia-Reyero N. A modular approach for assembly of quantitative adverse outcome pathways. ALTEX 2019, 36, 353–362. 10.14573/altex.1810181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Xie L.; Lee Y.; Tollefsen K. E. De novo development of a quantitative adverse outcome pathway (qAOP) network for ultraviolet B (UVB) dadiation using targeted laboratory tests and automated data mining. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13147–13156. 10.1021/acs.est.0c03794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siméon S.; Beaudouin R.; Brotzmann K.; Braunbeck T.; Bois F. Y. Multistate models of developmental toxicity: Application to valproic acid-induced malformations in the zebrafish embryo. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 414, 115424. 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinu N.; Cronin M. T. D.; Enoch S. J.; Madden J. C.; Worth A. P. Quantitative adverse outcome pathway (qAOP) models for toxicity prediction. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1497–1510. 10.1007/s00204-020-02774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.