Abstract

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli has a propensity to build biofilms to resist host defense and antimicrobials. Recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by multidrug-resistant, biofilm-forming E. coli is a significant public health problem. Consequently, searching for alternative medications has become essential. This study was undertaken to investigate the antibacterial, synergistic, and antibiofilm activities of catechin isolated from Canarium patentinervium Miq. against three E. coli ATCC reference strains (ATCC 25922, ATCC 8739, and ATCC 43895) and fifteen clinical isolates collected from UTI patients in Baghdad, Iraq. In addition, the expression of the biofilm-related gene, acrA, was evaluated with and without catechin treatment. Molecular docking was performed to evaluate the binding mode between catechin and the target protein using Autodock Vina 1.2.0 software. Catechin demonstrated significant bactericidal activity with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) range of 1–2 mg/mL and a minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) range of 2–4 mg/mL and strong synergy when combined with tetracycline at the MBC value. In addition, catechin substantially reduced E. coli biofilm by downregulating the acrA gene with a reduction percent ≥ 60%. In silico analysis revealed that catechin bound with high affinity (∆G = −8.2 kcal/mol) to AcrB protein (PDB-ID: 5ENT), one of the key AcrAB-TolC efflux pump proteins suggesting that catechin might inhibit the acrA gene indirectly by docking at the active site of AcrB protein.

Keywords: Canarium patentinervium Miq., multidrug resistance, antibiofilm activity, AcrAB-TolC efflux pump, molecular docking, Autodock Vina

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative multifaceted bacterium that comprises commensal E. coli, which normally colonizes in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals a few hours after birth [1], and pathogenic E. coli, which is the most common cause of gastrointestinal infections such as diarrheal disease caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and extraintestinal infections such as urinary tract infections (UTI) caused by uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) [2]. Some E. coli clones became pathogenic when they gain a number of specialized virulence factors, such as different adhesins, toxins, siderophores, and iron acquisition systems that interfere with the way the host cell works [3].

UTIs are commonly classified as community-acquired or healthcare-associated UTIs, and as complicated or uncomplicated UTIs, depending on the severity of the infection [4]. UTI is one of the most common bacterial infections worldwide, with an estimated 150 million UTI cases occurring each year [5]. Due to the anatomy of the female urinary tract, it is estimated that 50–60% of women will develop an UTI at some point in their lives [6]. UTIs are treatable in most cases. However, the progression of multidrug-resistant strains results in recurrent infections, treatment failure, and complications associated with increased rates of mortality and morbidity [7].

E. coli resists antibiotics through several mechanisms, such as production of enzymes called “beta-lactamases”, which is a group of more than 2800 compounds derived from environmental sources, including extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), AmpC beta-lactamase that acquires resistance to penicillin and cephalosporins, New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, and Carbapenem hydrolyzing oxacillinase-48 [8]. Furthermore, efflux pump activity such as the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) tripartite efflux pump, AcrAB-TolC, represents the major contributor to intrinsic multidrug resistance in E. coli [9]. In addition, E. coli possesses several virulence factors to ensure survival, such as hemolysis and biofilm formation [10].

Biofilm formation enables E. coli colonies to evade the immune system and antibiotics, making it difficult to eradicate and resulting in multiple antibiotic resistance [11]. Increased drug resistance and the emergence of bacterial infections with no treatment options yet available make research into new antimicrobial agents urgent. On the other hand, medicinal plants provide a promising source for drug discovery. Since ancient times, Indigenous peoples have utilized medicinal plants to treat various conditions [12]. Today, people continue to depend on herbal therapy, particularly in developing nations where 80% of the population uses traditional medicine to treat a variety of illnesses [13].

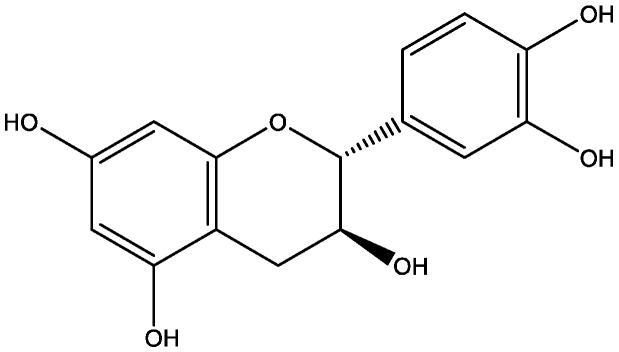

Canarium patentinervium Miq. is a rare tropical plant belonging to the family Burseraceae, genus Canarium L., native to Asiatic–Pacific region, Malaysia, and Brunei [14]. It has been used for wound healing by Indigenous peoples of Malaysia [14]. Our team previously reported the antibacterial activity of the crude extracts, fractions, and isolated compounds from the leaves and bark of this plant [15,16]. The current study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the antibacterial activity of catechin (Figure 1), one of the active compounds isolated previously from the leaves of Canarium patentinervium Miq., against biofilm-forming, uropathogenic E. coli isolates from UTI urine samples collected in Baghdad, Iraq during the period November–December 2021. Molecular docking was carried out to achieve a deep insight into the molecular mechanism and to analyze the binding mode between catechin and the target protein proposed in the study.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of catechin.

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity

The study investigated the antibacterial activity of catechin isolated from the leaves of Canarium patentinervium Miq. against three E. coli ATCC strains (E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 8739, and E. coli 43895) and 15 multidrug-resistant E. coli clinical isolates. The results are displayed in Table 1. Among the tested antibiotics, tetracycline, erythromycin, clindamycin, and vancomycin showed insignificant inhibition zones in all E. coli ATCC strains. E. coli ATCC 8739 had intermediate sensitivity to rifampin (17.24 mm) and gentamicin (13.14 mm). In addition, gentamicin displayed moderate inhibition against E. coli ATCC 43895 (13.6 mm), although it showed a significant zone of inhibition against E. coli ATCC 25922 (31.32 mm). Nevertheless, E. coli clinical isolates displayed insignificant inhibition zones for most of the tested antibiotics. In regard to catechin, E. coli ATCC 8739 was resistant (9 mm), although catechin displayed remarkable inhibition against the remaining E. coli strains ATCC 25922 (10.47 mm), E. coli ATCC 43895 (11.8 mm) and most of the clinical isolates (zone of inhibition ranges from 9.93 mm to 13.92 mm). The synergistic effect of catechin in combination with the tested antibiotics was evaluated in this study. Results are displayed in Table 1. The strongest synergistic effect was observed between catechin and tetracycline, through which all the isolates (n = 15) showed synergism with no antagonism reported. In addition, combinations between catechin with azithromycin, gentamicin, erythromycin, and clindamycin displayed a high percentage of synergism with additive effects reported in three isolates, while the combination of catechin with rifampin had the lowest synergy with high antagonism reported.

Table 1.

Zone of inhibition (mm) for the antimicrobial agents and catechin alone and in combination against E. coli isolates.

| Bacteria | Antimicrobials | Zone of Inhibition (ZI) (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZI of Antimicrobials | ZI Breakpoints According to CLSI * | ZI of Catechin | ZI of Catechin in Combination with Antimicrobials | Outcome | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 # | Rifampin | 7.42 ± 0.0 | R | 10.47 ± 0.0 | 16 ± 0.0 | Antagonism |

| Tetracycline | - | R | 10.4 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 10.0 ± 0.0 | Antagonism | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 10.45 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Azithromycin | 10.95 ± 0.0 | R | 22.5 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 10.4 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 31.32 ± 0.0 | S | 35 ± 0.0 | Antagonism | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 # | Rifampin | 17.24 ± 0.0 | I | 9 ± 0.0 | 26 ± 0.0 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | - | R | 9.1 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 8.8 ± 0.0 | Antagonism | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 9.0 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Azithromycin | 15.15 ± 0.0 | S | 25 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 9.5 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 13.14 ± 0.0 | I | 22 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 43895 # | Rifampin | - | R | 11.8 ± 0.0 | 11.5 ± 0.0 | Antagonism |

| Tetracycline | - | R | 12.0 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 11.5 ± 0.0 | Antagonism | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 11.45 ± 0.0 | Antagonism | ||

| Azithromycin | 6.03 ± 0.0 | R | 17 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 11.8 ± 0.0 | Additive | ||

| Gentamycin | 13.6 ± 0.0 | I | 22 | Antagonism | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 1) |

Rifampin | 2.45 ± 4.2 | R | 12.27 ± 1.3 | 13.89 ± 3.6 | Antagonism |

| Tetracycline | 13.85 ± 2.5 | I | 28.58 ± 1.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 11.97 ± 7.9 | I | 25.04 ± 0.6 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 7.71 ± 8.7 | R | 22.19 ± 1.3 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 11.58 ± 3.2 | R | 24.8 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 13.72 ± 7.2 | I | 26.43 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 10.42 ± 5.6 | R | 23.58 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 2) |

Rifampin | - | R | 13.92 ± 3.6 | 14.0 ± 0.0 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 16.83 ± 1.0 | S | 31.5 ± 10.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 18.97 ± 3.5 | I | 33.1 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 17.75 ± 0.4 | I | 31.5 ± 4.5 | Additive | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.60 ± 2.84 | I | 27.2 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 17.87 ± 2.2 | S | 31.6 ± 0.9 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 16.95 ± 0.3 | S | 30.7 ± 0.8 | Additive | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 3) |

Rifampin | - | R | 12.9 ± 2.4 | 9.0 ± 5.2 | Antagonism |

| Tetracycline | 12.35 ± 0.4 | I | 26.12 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 16.19 ± 1.0 | I | 31.5 ± 2.1 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 15.37 ± 3.8 | I | 28.2 ± 3.1 | Additive | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.43 ± 2.2 | I | 26.3 ± 0.3 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 18.87 ± 0.0 | S | 32.0 ± 0.7 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 16.24 ± 1.3 | S | 29.0 ± 0.1 | Additive | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 4) |

Rifampin | 10.87 ± 0.0 | R | 13.09 ± 0.0 | 20.21 ± 1.6 | Antagonism |

| Tetracycline | 15.26 ± 0.5 | S | 30.0 ± 1.6 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 20.61 ± 4.0 | I | 34.0 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 16.42 ± 1.1 | I | 29.5 ± 1.2 | Additive | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.42 ± 0.7 | I | 26.1 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 20.03 ± 5.2 | S | 25.5 ± 0.1 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | - | R | 13.1 ± 2.4 | Additive | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 5) |

Rifampin | - | R | 10.68 ± 5.6 | 10.71 ± 1.1 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 16.82 ± 2.3 | S | 30.23 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 16.5 ± 0.0 | I | 28.0 ± 4.4 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 12.1 ± 3.3 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.12 ± 1.5 | I | 24.0 ± 0.8 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 17.71 ± 3.4 | S | 29.0 ± 0.3 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | - | R | 11.0 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 6) |

Rifampin | - | R | 9.93 ± 3.6 | 9.0 ± 4.5 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 12.26 ± 1.0 | I | 25.0 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 14.1 ± 0.6 | I | 25.0 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 10.5 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.31 ± 2.6 | I | 23.2 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 16.82 ± 0.5 | I | 27.0 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 11.45 ± 0.0 | R | 21.8 ± 0.3 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 7) |

Rifampin | - | R | 12.75 ± 5.6 | 14.74 ± 8.3 | Synergy |

| Tetracycline | 12.93 ± 0.2 | I | 27.3 ± 0.9 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 14.59 ± 1.4 | I | 28.1 ± 3.4 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 13.22 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.94 ± 0.6 | I | 26.6 ± 0.9 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 18.21 ± 1.5 | S | 30.89 ± 0.6 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 11.81 ± 0.0 | R | 25.6 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 8) |

Rifampin | - | R | 10.08 ± 4.3 | 14.69 ± 0.8 | Synergy |

| Tetracycline | 12.12 ± 11.0 | I | 24.6 ± 5.3 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 17.73 ± 8.76 | I | 28.4 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 11.54 ± 1.3 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.04 ± 5.6 | I | 23.1 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 10.0 ± 3.4 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 11.02 ± 7.0 | R | 22.0 ± 1.1 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 9) |

Rifampin | 9.46 ± 1.1 | R | 13.58 ± 2.3 | 23.1 ± 2.5 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 13.46 ± 2.3 | I | 27.89 ± 6.8 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 19.09 ± 0.6 | I | 33.1 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 14.0 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.82 ± 0.0 | I | 27.0 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 13.5 ± 0.6 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 11.1 ± 0.0 | R | 26.4 ± 0.8 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 10) |

Rifampin | - | R | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 12.6 ± 1.3 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 13.4 ± 0.5 | I | 27.0 ± 1.1 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 14.34 ± 4.1 | I | 28.5 ± 8.85 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 15.38 ± 3.2 | I | 30.0 ± 5.5 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.55 ± 8.5 | I | 26.4 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | - | R | 12.82 ± 0.9 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 13.52 ± 6.1 | I | 27.2 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 11) |

Rifampin | - | R | 10.38 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.5 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 12.28 ± 0.0 | I | 24.5 ± 0.7 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 10.5 ± 1.4 | Additive | ||

| Clindamycin | 16.69 ± 1.1 | I | 28.1 ± 1.1 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.21 ± 0.9 | I | 22.5 ± 0.5 | Additive | ||

| Vancomycin | 16.59 ± 3.1 | I | 29.0 ± 0.7 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 13.76 ± 2.5 | I | 25.4 ± 1.1 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 12) |

Rifampin | 8.76 ± 5.3 | R | 13.17 ± 1.5 | 22.5 ± 6.4 | Synergy |

| Tetracycline | 18.34 ± 7.1 | I | 31.9 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 13.4 ± 11.0 | Additive | ||

| Clindamycin | 15.71 ± 2.6 | I | 30.5 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.77 ± 1.5 | I | 26.4 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 15.24 ± 1.1 | I | 28.5 ± 0.4 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 13.73 ± 0.6 | I | 27.5 ± 0.9 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 13) |

Rifampin | - | R | 13.18 ± 8.7 | 13.0 ± 0.0 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 9.82 ± 4.3 | R | 25.4 ± 1.4 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 14.21 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | 18.27 ± 5.2 | I | 32.0 ± 0.5 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 12.67 ± 9.7 | I | 27.1 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Vancomycin | 16.37 ± 10.0 | I | 29.45 ± 0.5 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | 13.14 ± 8.7 | I | 27.2 ± 0.3 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 14) |

Rifampin | 7.67 ± 2.6 | R | 12.4 ± 1.3 | 20.0 ± 3.8 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 10.22 ± 11.0 | R | 23.4 ± 1.5 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | - | R | 12.42 ± 0.5 | Additive | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 13.1 ± 0.6 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | 11.28 ± 5.4 | I | 23.5 ± 2.7 | Additive | ||

| Vancomycin | 16.24 ± 8.6 | I | 29.0 ± 0.4 | Synergy | ||

| Gentamicin | 11.81 ± 5.9 | I | 25.1 ± 0.2 | Synergy | ||

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 15) |

Rifampin | - | R | 12.62 ± 6.6 | 12.5 ± 7.8 | Additive |

| Tetracycline | 15.89 ± 7.4 | S | 29.1 ± 0.0 | Synergy | ||

| Erythromycin | 9.42 ± 11.0 | R | 24.01 ± 11.6 | Synergy | ||

| Clindamycin | - | R | 14.0 ± 4.3 | Synergy | ||

| Azithromycin | - | R | 12.5 ± 0.9 | Additive | ||

| Vancomycin | 15.37 ± 8.3 | I | 28.0 ± 0.9 | Additive | ||

| Gentamicin | - | R | 13.2 ± 0.6 | Synergy | ||

“#” means statistical data are unavailable, “-” means no activity, and “*” indicates that the results are categorized according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines into R resistant; I intermediately resistant; and S sensitive. All the data were obtained from three independent experiments and is expressed as mean ± SD.

The minimum inhibitory concentration is the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibits the visible growth of a bacterium following overnight incubation [17]. Azithromycin showed potent antibacterial activity with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.5 mg/mL against E. coli ATCC 8739 and 0.5–1 mg/mL against E. coli clinical isolates (Table 2). The MICs for the rest of the antibiotics ranged from 2 to 32 mg/mL, and they were only moderately effective against all of the strains tested. Catechin exhibited moderate activity (MIC = 1 mg/mL) against E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 43895, and E. coli clinical isolates, weak activity against E. coli ATCC 8739 (MIC = 2 mg/mL), and potent activity against two clinical isolates (isolate numbers 9 and 10) with a MIC of 0.5 mg/mL. According to the literature, strong antibacterial activity is considered with MIC values ranging from 0.05–0.5 mg/mL, moderate activity with MIC values ranging from 0.6–1.5 mg/mL, and weak antibacterial activity when the MIC values exceed 1.5 mg/mL [18].

Table 2.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) (mg/mL), minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (mg/mL), and MBC/MIC ratio for the antimicrobial agents and catechin against E. coli isolates.

| Bacteria | Effect | Rifampin | Tetracycline | Erythromycin | Clindamycin | Azithromycin | Vancomycin | Gentamycin | Catechin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 # | MBC | 8 | 32 | 32 | 8 | 8 | 64 | 4 | 2 |

| MIC | 4 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 # | MBC | 4 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 1 | 32 | 4 | 4 |

| MIC | 2 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 2 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 43895 # | MBC | 8 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 |

| MIC | 4 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 1) |

MBC | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 2) |

MBC | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 3) |

MBC | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 4) |

MBC | 32 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 16 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 16(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 5) |

MBC | 16 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 16(−) | 4(+) | 16(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 6) |

MBC | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 64 | 4 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 7) |

MBC | 32 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 2 | 64 | 16 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 4(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 16(−) | 2(+) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 8) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 32 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 8(−) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 9) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 4 | 2 |

| MIC | 16 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| MBC/MIC | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(−) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 10) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 64 | 4 | 2 |

| MIC | 32 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 11) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 32 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 12) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 32 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 4(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 13) |

MBC | 64 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 32 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 4(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 14) |

MBC | 16 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 8 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 2(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 4(+) | |

|

Escherichia coli

(isolate 15) |

MBC | 32 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MIC | 16 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 16 | 4 | 1 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2(+) | 2(+) | 8(−) | 8(−) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 4(+) |

“#” means statistical data are unavailable. All the data were obtained from three independent experiments. For the MBC/MIC ratio, (+) bactericidal; (−) bacteriostatic.

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) is the lowest antimicrobial concentration that will stop an organism from growing after being subcultured on an antibiotic-free medium [17]. According to the ratio of MBC/MIC, the antibacterial effect is considered bactericidal if the MBC/MIC ≤ 4, and the effect is considered bacteriostatic if the MBC/MIC > 4 [19]. The MBC, MIC, and MBC/MIC ratio for the tested antibiotics and catechin are displayed in Table 2. All the tested antibiotics showed bactericidal activity against the tested strains except for tetracycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin, which showed bacteriostatic activity against some of the clinical isolates. Catechin exhibited bactericidal action against all the tested E. coli strains. Azithromycin was the most active antibiotic and E. coli ATCC 8739 was the most susceptible strain (MIC = 0.5 mg/mL, MBC = 1 mg/mL, MBC/MIC = 2). It is noteworthy that E. coli ATCC 8739 was resistant to catechin and all antibiotics except azithromycin. Interestingly, E. coli ATCC 43895 was the most sensitive strain to catechin (MIC = 1 mg/mL, MBC = 2 mg/ mL, MBC/MIC = 2), although it was resistant to all the tested antibiotics. Both catechin and azithromycin had significant antibacterial activity against E. coli clinical isolates with bactericidal effects, while the remaining antibiotics were inactive against the tested strains (MIC ranges of 2–32 mg/mL, MBC ranges of 4–64 mg/mL).

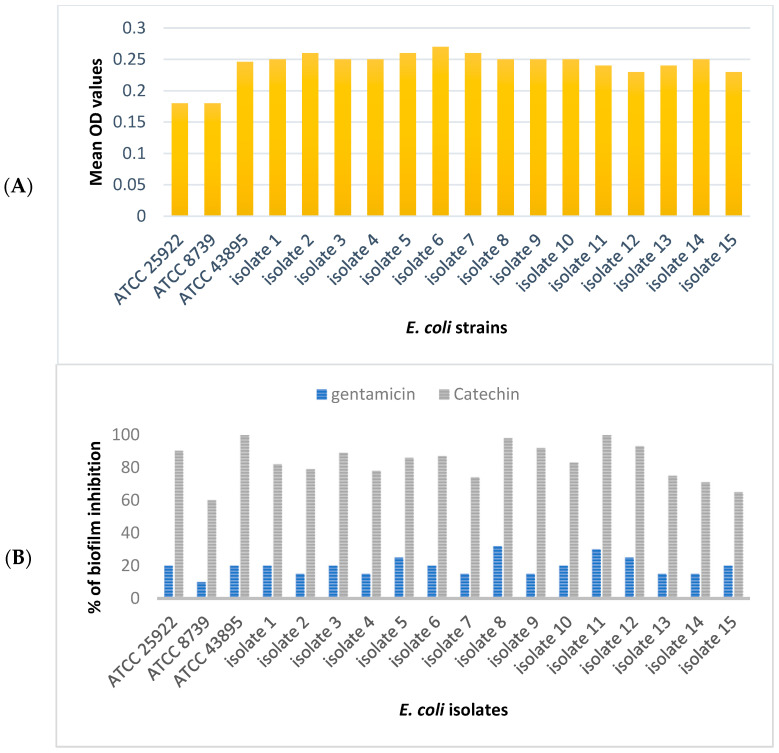

2.2. Biofilm Inhibition

The results for the biofilm inhibition assay of this study are shown in Figure 2. All the tested E. coli strains were biofilm producers. E. coli ATCC 43894 and the clinical isolates were strong biofilm formers (mean OD = 0.25), while E. coli ATCC 8739 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were moderate biofilm formers (mean OD = 0.18). According to the literature, mean OD values > 0.24 indicate that the tested bacterium can form strong biofilm, mean OD values 0.12–0.24 indicate that the test bacterium has moderate biofilm-forming ability, and mean OD values < 0.12 indicate weak or no biofilm formation [20]. Catechin at the MIC level distorted the biofilm formation of all the tested E. coli. The results indicated that catechin inhibited E. coli adhesion at a percentage of inhibition equal to 90.3% for E. coli ATCC 25922, 60% for E. coli ATCC 8739, 100% for E. coli ATCC 43895, and an average of 82% biofilm inhibition for E. coli clinical isolates. Inhibition of biofilm formation by gentamicin was modest against all of the examined E. coli strains.

Figure 2.

Biofilm formation ability of E. coli ATCC and clinical isolates (A), and biofilm inhibition effect of catechin (B). Gentamicin is the positive control. All the data were obtained from three independent experiments, and the mean values were presented.

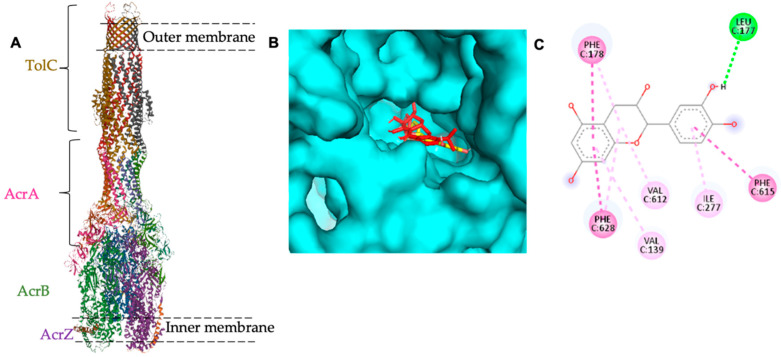

2.3. In Silico Study

In a previous study, the relationship of the acrA gene with the biofilm formation ability of E. coli was established [11]. Thus, a molecular docking study was carried out to check catechin binding affinity to this protein. The AcrA protein is one of the AcrAB-TolC multidrug-resistant efflux pump proteins (Figure 3). AcrAB-TolC is a member of the resistance nodulation division family (RND) that is present in Gram-negative bacteria and has a crucial role in the E. coli resistance mechanism to broad spectrum antibiotics [21]. The pump consists of three major proteins; an outer membrane channel called TolC acts as an exit pathway of substrates; periplasmic protein AcrA is responsible for the stability of the connection between AcrB and TolC; and an inner membrane protein called AcrB, which is the target site for substrate binding [22,23,24,25]. In addition to the small residue that was identified recently, AcrZ affects substrate preference of AcrB [26].

Figure 3.

(A) Cryo-EM asymmetric structure of AcrBZ-Tolc pump of E. coli at 6.50 Å resolution (PDB-ID: 5NG5). (B) Binding affinity of catechin to AcrB protein of E. coli (docked catechin in yellow whereas docked minocycline is in red color). (C) the amino acids involved in the binding site of catechin to AcrB protein.

It is noteworthy that the AcrA protein has no substrate binding site and AcrB is the substrate binding site in several antimicrobial agents such as Puromycin (PDB-ID: 5NC5), Erythromycin (PDB-ID: 3AOC), Rifampicin (PDB-ID: 3AOD), Levofloxacin (PDB-ID: 7B8T), Doxycycline (PDB-ID: 7B8R), Linezolid (PDB-ID: 4K7Q), Fusidic acid (PDB-ID: 6Q4P), and Minocycline (PDB-ID: 5ENT). In this regard, catechin binding affinity to AcrB was tested and the result was presented in Figure 2. Catechin showed high binding affinity to AcrB (PDB-ID: 5ENT) with ∆G = −8.2 Kcal/mol compared to the control ligand (minocycline) with ∆G = −8.8 Kcal/mol (Table 3). Nevertheless, further in vitro tests on the catechin effect on the AcrAB-TolC are required to confirm efflux pump inhibition of catechin.

Table 3.

Binding affinity of catechin to AcrB protein of E. coli.

| Compound | Molecular Docking Binding Affinity ΔG (Kcal/mol) | Residue Involved in the Binding Site | Bonds Involved in the Binding Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minocycline (control) | −8.8 | PHE-178 (chain C), ASN-274 (chain C) | Hydrogen bond |

| VAL-612 (chain C), ALA-279 (chain C) | Pi-Pi stacked | ||

| ILE-277 (chain C), PHE-615 (chain C) | Pi-Sigma | ||

| Catechin | −8.2 | GLY-179 (chain C) | Hydrogen bond |

| LEU-177 (chain C) | Carbon Hydrogen bond | ||

| PHE-178 (chain C), VAL-612 (chain C), ILE-277 (chain C) | Pi-Pi stacked |

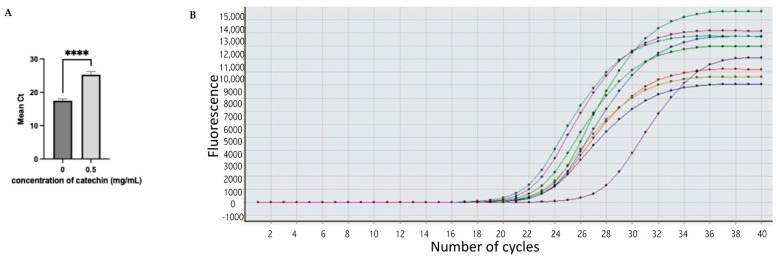

2.4. Gene Expression

In the current study, fifteen clinical E. coli isolates were tested for the expression of the biofilm related gene, acrA, using the SYBR green assay for real-time PCR [27]. The results are summarized in Figure 4 and Table 4. A housekeeping gene, 16S rRNA, was used, which is commonly used in PCR analysis of bacteria [28]. The acrA gene was expressed in nine E. coli isolates (60% target gene expression). However, the expression was depressed in E. coli isolates treated with catechin at sub-MIC (0.5 mg/mL).

Figure 4.

Expression of acrA gene in E. coli clinical isolates. (A) The level of expression without catechin treatment and with catechin treatment at concentration = 0.5 mg/mL. (B) The level of acrA expression in nine isolates represented in colored lines after catechin treatment. Data were expressed as mean ± SD with significant level **** p < 0.001.

Table 4.

The expression level of the 16S rRNA and acrA genes in E. coli clinical isolates.

| Isolate Number | Mean of Ct of 16S rRNA (Untreated) | Mean of Ct of 16S rRNA (Treated) | Mean of Ct of acrA Gene (Untreated) | Mean of Ct of acrA Gene (Catechin Treated) | ΔCt for acrA Gene | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | 19.34 | 17.8 | 24.8 | 7 | Down |

| 2 | 16.9 | 18.45 | 17.2 | 24.7 | 7.5 | Down |

| 3 | 17.2 | 19.5 | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 17.2 | 18.45 | - | - | - | |

| 5 | 17.3 | 21.5 | 16.8 | 24.7 | 7.9 | Down |

| 6 | 17.6 | 19.34 | 18.3 | 25 | 6.9 | Down |

| 7 | 18.2 | 19 | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | 17.7 | 21 | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | 18 | 20.41 | 17.8 | 24.8 | 7 | Down |

| 10 | 18.1 | 19.45 | 16.6 | 26.7 | 10.1 | Down |

| 11 | 17.6 | 18 | - | - | - | |

| 12 | 17.7 | 18.2 | 18 | 27.2 | 9.2 | Down |

| 13 | 16.9 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 24.8 | 7.1 | Down |

| 14 | 16.7 | 17.9 | 16.9 | 24.7 | 7.8 | Down |

| 15 | 17.3 | 19.3 | - | - | - | - |

Ct, thermal cycle; -, acrA gene is not detected. ∆Ct = CtacrA (treated with catechin) − CtacrA (untreated).

Ct (thermal cycle) is the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal to cross the thresholds and it is inversely proportional to the amount of the target gene (i.e., lower Ct indicates greater amount of target gene) [29]. Cts values of 29 indicate an abundance of target genes and strong positive reactions, according to the literature. Cts values ranging from 30–37 indicate a moderate number of target genes. Cts values of 38–40 are considered weak reactions with a small number of target genes [30,31]. In this study, acrA expression occurred in Ct < 29, reflecting a positive reaction. Moreover E. coli isolates that were treated with catechin showed a significant reduction in the target gene (acrA). By combining the results of the in silico and the in vitro studies, we suggested that catechin antibacterial action against multidrug-resistant uropathogenic E. coli is due to biofilm inhibition and efflux pump mechanism. According to the in silico result, catechin binds the substrate recognition site in the AcrAB-TolC of E. coli, which might indirectly affect the AcrA protein. Further in vitro tests on the catechin activity on the E. coli efflux pump system are warranted.

3. Discussion

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most prevalent infectious diseases with a high recurrence rate worldwide [32]. Among several pathogens that cause UTIs, E. coli is considered as the major causative pathogen, accounting for 90% of community-acquired infections and 50% of nosocomial infections [33]. Recurrent UTIs with multidrug-resistant E.coli impose both an economic and health burden [34]. It has been reported that 78% of recurrent urinary tract infections are caused by multidrug-resistant, biofilm-forming E. coli [33]. Biofilm formation by many pathogens is considered as one of the indirect strategies for multidrug resistance [35]. Bacteria producing biofilm are difficult to eradicate and are able to transfer their resistance genes within their biofilm community, causing recurrent infections [36]. Many species have the ability to form biofilms, such as Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Bacillus, etc. [37].

A biofilm is a complex matrix composed of polysaccharides, nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, water, various ions, and other organic components in which cells bind together to survive harsh conditions such as host defense and accumulation of various noxious substances and antimicrobial agents [38]. According to the recent assessment by the National Institute of Health (NIH), more than 60% of in vivo infections are due to biofilm-forming microorganisms [39]. Currently, biofilm-producing bacteria have been designated as a major concern because of chronic infections [40]. It has been proven that biofilm formation makes bacteria 10–1000 times more antibiotic resistant. Several pathogens such as Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp. that are known as “ESKAPE” infections are distinguished by their strong biofilm formation [38]. Thus, the search for new antimicrobials with biofilm inhibition properties is urgently needed.

Plant secondary metabolites have acquired extra attention in the area of drug development as they are safe, derived from natural sources, and have high bioavailability [41]. Many of them have been proven to have antibiofilm activity [42]. Canarium patentinervium Miq. is a rare plant from the Burseraceae family, genus Canarium L., found in Asia [43]. Our team previously documented several medicinal activities of this plant, such as antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticholinesterase, and antitumor [16,44,45]. In this study, the antibacterial activity of catechin isolated from the ethanolic extract of the leaves of Canarium patentinervium Miq. was assessed against reference and multidrug-resistant uropathogenic E. coli. Based on the findings, catechin had significant antibacterial activity (MIC ranges of 1–2 mg/mL, MBC/MIC ≤ 4) against all the tested strains. In addition, catechin showed high synergism with the tetracycline combination. Catechin’s antibacterial effect against E. coli has been reported in several studies [46,47,48]. It was shown that catechin inhibited E. coli growth in a dose-dependent manner [48,49].

In this study, the biofilm formation ability of E. coli strains was assessed quantitatively, and the result indicated that all the tested E. coli strains formed biofilm and were multidrug resistant. Catechin inhibited E. coli biofilm significantly, with a percent inhibition range of 60–100%. The antibiofilm activity of catechin has been reported in several studies [50,51]. Catechin at a concentration of 0.026 g/L showed significant biofilm inhibition in MRSA strains through downregulation of fnbA and icaBC genes in MRSA [50]. Similarly, green tea epigallocatechin gallate EGCG at sub-inhibitory concentration remarkably reduced the adhesion of MRSA by interfering with bacterial glucosyltransferase involved in biofilm formation [52]. In E. coli, EGCG showed antibiofilm activity by attenuating the expression or activity of several virulence factors such as Shiga toxin [53].

In the current study, catechin attenuated the expression of the acrA gene related to E. coli biofilm formation and multidrug resistance. In a previous study, the expression of acrA was significantly reduced in multidrug-resistant E. coli strains under the pressure of four aminoglycosides (streptomycin, gentamicin, amikacin, and apramycin) at sub-inhibitory concentration [11]. Molecular docking was performed to achieve a better understanding of catechin action on E. coli biofilm-related genes. Based on the result, catechin exhibited high binding affinity to the AcrB protein, which is one of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump proteins that are responsible for E. coli multidrug resistance [21]. The AcrAB-TolC efflux pump is an RND-type tripartite efflux pump that is a major contributor to multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. It has three major proteins, one of which is the AcrB protein, which represents the ligand interaction site. Upon ligand binding to AcrB, quaternary structural changes occurred in AcrB that communicated with AcrA to trigger structural changes leading to the opening of the TolC channel from the sealing resting state [54]. Although the AcrA protein lacks a substrate binding site, it serves as a link between AcrB and TolC and plays an important role in the stability of the AcrAB-TolC pump [54]. Based on the in silico result, we suggested that catechin isolated from Canarium patentinervium Miq. might indirectly reduce the expression of the biofilm related acrA gene by binding to the AcrB domain of the E. coli AcrAB-TolC efflux pump. Further in vitro tests to confirm the efflux pump inhibition effect of catechin are required.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

The leaves and bark of Canarium patentinervium Miq. were previously collected from one individual tree in Bukit Putih, Selangor, Malaysia (3°5′24″ N 101°46′0″ E). The plant was collected with the approval and assistance of the local Indigenous people. The plant was identified by Mr. Kamaruddin (Forest Research Institute of Malaysia). A herbarium sample (PID 251210-12) has been deposited at the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia. The leaves and bark were air dried and ground into small particles using an industrial grinder. Our team previously isolated catechin from the ethanolic extracts of the leaves through bioassay-guided fractionation using Sephadex LH-20 (30 cm × 60 cm) and Silica gel (4 cm × 90 cm) [55].

4.2. Chemicals

The following chemicals were purchased from different manufacturers: MacConkey agar and Mannitol salt agar (Himedia, Thane, India), Nutrient agar, EMB agar medium, Mueller–Hinton agar medium and Mueller–Hinton broth medium (Oxoid, Hampshire, England), Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth and CCA medium (Condalab, Madrid, Spain), Gram stain solutions (Fluka, Buch, Switzerland), Glycerol (B.D.H, London, UK), Normal saline (Mediplast, Dubai, United Arab Emirates), Absolute ethanol 99% (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), DMSO ≥ 99% (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), EasyScript ®First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Transgen, Beijing, China), Real mod TM green (Takara, Maebashi, Japan), Quick-RNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (Zymo, CA, USA).

4.3. Bacterial Strains

The clinical isolates of E. coli were obtained from the Bacteriology Unit, Department of Clinical Laboratory in the Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq. Samples were collected from UTI patients during the period from November 2021 to December 2021. E. coli ATCC reference bacteria (ATCC 25922, ATCC 8739, and ATCC 43895) were obtained from the Central Health Lab, Baghdad, Iraq. For all experiments except for the gene expression, three E. coli (ATCC reference) cultures and 15 clinical isolates were used.

Bacteria were cultured in a Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (Incubator IN55 Plus, Memmert GmBH, Schwabach, Germany) to promote bacterial growth. To identify E. coli, bacteria were streaked in general nutrient agar and differential culture media such as Chromogenic Coliforms Agar (CCA) medium and Eosin Methylene Blue agar (EMB). Antibiotic susceptibility (Table 5) was performed in VITEK®2 system (bioMérieux, Craponne, France) according to manufacturing company, E. coli was inoculated on MacConkey agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Table 5.

Bacterial source and antibiotic resistance profile.

| Bacteria | Source | Resistance Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | Central Health Lab/Iraq | (R) TET, ERY, VAN, RIF, AZM, PIP (S) GEN, MIN, MEM |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 | Central Health Lab/Iraq | (R) TET, ERY, CLI, VAN (S) GEN, AZM, RIF |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 43895 | Central Health Lab/Iraq | (R) RIF, TET, ERY, AZM, PIP, TIC, TOB (S) CFM, FEP, MIN |

| Escherichia coli | Urine from UTI samples | (R) TIC, PIP, GEN, TOB, CIP, SXT (S) TIM, TZP, CAZ, FEP, ATM, IPM, MEM, AMK, MIN |

(R) resistant, (S) sensitive, TET tetracycline, ERY erythromycin, VAN vancomycin, RIF rifampin, AZM azithromycin, PIP piperacillin, GEN gentamycin, MIN minocycline, MEM meropenem, CLI clindamycin, TIC ticarcillin, TOB tobramycin, CFM cefixime, FEP cefepime, CIP ciprofloxacin, SXT trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, TIM ticarcillin- Clavulanic acid, TZP piperacillin-tazobactam, CAZ ceftazidime, ATM aztreonam, IPM imipenem, AMK amikacin.

4.4. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity

4.4.1. Disc Diffusion Assay

This test was performed using the Kirby–Bauer technique for disc diffusion following the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards methods (NCCLS) [56]. Seven antimicrobial discs have been used (azithromycin 15 µg, vancomycin 30 µg, clindamycin 2 µg, erythromycin 10 µg, gentamicin 10 µg, rifampin 5 µg, and tetracycline 10 µg) (Bioanalyse, Ankara, Turkey) based on recommendations given by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI,2020) [57]. The inoculum was prepared by transferring at least 3–5 isolated colonies that were grown previously in CCA agar to a bijou bottle containing 3 mL of normal saline and incubated at 35 °C for 2 h to achieve the turbidity of growth equal to the normal turbidity standard of 0.5 McFarland/625 nm (inoculation of 1 × 108 CFU/mL).

The bacterial broth was used 15 min after the inoculum turbidity was adjusted. Then the inoculum was streaked into a petri dish with Mueller–Hinton agar medium with a thickness of 4 mm. The plate was dried at room temperature, then the antibiotic discs were added and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h. Catechin was used at a concentration of 100 mg/mL dissolved in DMSO ≥ 99%. The agar well diffusion method was performed for catechin based on the CLSI recommendation. A well with a diameter of 6 mm was punched aseptically into the petri dish with a sterile cork borer, and 20 µL of catechin solution was transferred into the well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h [58]. Positive and negative controls were used, where the negative control included the solvent (DMSO ≥ 99%), and the positive control represented the antibiotic discs. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured using a digital vernier caliper to determine the microbial growth. The experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean values were presented.

4.4.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The broth microdilution method was performed based on the guidelines given by CLSI as described by Eloff [59]. A stock solution of catechin dissolved in DMSO ≥ 99% was prepared in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorff) to a final concentration of 64 mg/mL and filtered with a 0.22 Millipore filter. Likewise, each individual antibiotic powder (Panpharma S.A., Luitré, France) was dissolved in a suitable solvent, DMSO ≥ 99% for (azithromycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and rifampin) and distilled water for (gentamicin, vancomycin, and clindamycin) with an initial concentration of 64 mg/mL for all antibiotics. Two-fold serial dilutions were made from the stock solution to obtain a concentration range from 32 mg/mL to 0.125 mg/mL using Mueller–Hinton broth in 96-well plates.

A standardized bacterial suspension (100 μL) at a concentration of 1 × 106 CFU/mL was added to each well containing the previously prepared 100 μL of diluted antimicrobial agents, resulting in a final volume of 200 μL in each well and final antibiotic concentrations ranging from 16 mg/mL to 0.125 mg/mL for a recommended final bacterial cell count of about 5 × 105 CFU/mL. To find out how sensitive the bacteria being tested were, a positive control was made up of broth, the antimicrobial agent’s solvent (either distilled water or DMSO), and the bacteria. On the other hand, a broth without inoculum and an antimicrobial agent solvent served as the negative control. Then the microtiter plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After that, the MIC value was determined visually by recording the lowest concentration with no visible growth (the first clear well). MIC values were determined in triplicate and repeated to confirm activity.

4.4.3. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was recorded as the lowest concentration that resulted in 99.9% killing of bacteria growth [60]. The MBC assay was performed using Ozturk and Ercisli method [61] by which only the susceptible bacteria from the MIC assay were considered. Ten microliters were taken from the well obtained from the MIC experiment (MIC value) and two wells above the MIC value well and spread on MHA plates. The number of colonies was counted after 18–24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The concentration of a sample that produces < 10 colonies is considered as MBC value. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the MBC/MIC ratio was determined. If the ratio MBC/MIC ≤ 4, the effect is considered bactericidal, but if the ratio MBC/MIC > 4, the effect is defined as bacteriostatic [19,62].

4.4.4. Synergistic Assay

In the presence of different antimicrobial agents (gentamicin, clindamycin, vancomycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, azithromycin, and Rifampin), the antimicrobial activity of catechin was tested. The bacterial strain was spread with a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates. For the assessments of the synergistic effects, selected antibiotic discs were discretely impregnated with 5 μL of catechin (at the MBC value) and employed on the inoculated agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The zones of inhibition produced by catechin in combination with standard antibiotics after overnight incubation were estimated. If zones of combination treatment > ‘more than’ (zone of catechin + zone of the corresponding antibiotic), it was interpreted as synergism; if zone of combination treatment = (zone of catechin + zone of correspondence antibiotic), it was interpreted as additive; if zone of combination treatment < ‘less than’ (zone of catechin + zone of the corresponding antibiotic), it was interpreted as antagonism [63,64].

4.5. Evaluation of Antibiofilm Activity

4.5.1. Biofilm Formation by E. coli

Microtiter plate assay or tissue culture plate (TCP) was used for quantitative determination of E. coli biofilm formation in accordance with O’Toole with some modification [65]. In brief, a sterile polystyrene tissue culture plate (composed of 96 flat bottom wells) was filled with 200 μL of the diluted prepared bacterial suspension and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, the content of each well was gently removed by tapping the plates, and the wells were washed twice with 200 μL phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) to remove free-floating ‘planktonic’ bacteria. Biofilms formed by adherent ‘sessile’ bacteria on plate were fixed by placing them in the incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, the wells were stained with 200 μL of 1% crystal violet solution for 45 min. After that, the microtiter plates were rinsed three times with sterile distilled water to remove excess dye and left to dry for 45 min at room temperature, then de-stained by adding 200 µL ethanol. A sterile bacterial broth was used as a negative control to identify non-specific binding. A micro-ELISA reader (at 570/655 nm wavelength) was used to measure the optical densities (OD) of stained bacterial biofilms. The experiment was conducted in triplicate and the average OD values were considered. The results were graded into strong, moderate, and non or weak biofilm.

4.5.2. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

Catechin at MIC value was added to each well of a 96-well microplate except for the positive control well, which contained gentamicin and the negative control well, which contained bacterial broth only [66,67]. Bacterial culture (1 × 108 CFU/mL) in an amount of 100 µL was pipetted into each well and the well was then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. After that, the content of each well was removed, and the wells were rinsed three times with distilled water and allow to dry at 60 °C for 45 min. Then the wells were stained with 200 µL of 1% crystal violet and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the plates were rinsed with distilled water, de-stained with ethanol, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. A microplate ELISA reader (model 680, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 570/655 nm was used to measure the optical densities. The experiment was conducted in triplicate and the mean absorbance was considered. The percentage of biofilm inhibition was then compared with the positive control and calculated according to the following formula:

| (1) |

4.6. In Silico Study

Molecular Docking

A docking study was conducted to predict the target protein for catechin antibiofilm action. In a previous study, the acrA gene that is related to antibiotic resistance of E. coli biofilm was identified [11]. The crystal structure of the target protein was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank database (https://www.rcsb.org/, accessed on 25 April 2022). AcrA protein (PDB-ID: 5NG5) is a component of the E. coli AcrAB-TolC efflux pump and consists of an AcrA subunit with six chains and 373 sequence length, an AcrB subunit with three chains and 1049 sequence length, an AcrZ subunit with three chains and 55 sequence length, and a TolC protein with three chains and 493 sequence length. The target protein was prepared for docking by removing water, adding hydrogens and kollman charges and saved as pdb format using Autodock tools 1.5.1 [68]. Then the natural ligand was extracted from the protein using Discovery Studio Visualizer software (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download, accessed on 25 April 2022). The ligand and the protein were edited in Autodock tools 1.5.1. The grid box was centered on the ligand and control docking was run using Autodock Vina 1.1.2 software [69]. The same protocol was repeated with catechin as the ligand and the 3D structure of catechin (ID: 9064) was obtained from the PubChem data base (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 26 April 2022). The docking simulation was repeated three times, and the average binding affinity was considered. Several parameters were evaluated, such as the binding affinity of catechin toward the target protein, the ligand interaction site, the amino acids involved in the binding pocket, and the bonds formed at the interaction site. Results were analyzed using PyMOL [70] and visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer (Dassault Systèmes, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.7. Gene Expression Using Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

To evaluate the effect of catechin on biofilm-related gene expression, quantitative real-time PCR (Mx3000P qPCR System, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) was performed on E. coli clinical isolates with and without catechin (at the sub-inhibitory concentration = 0.5 mg/mL) [71]. E. coli clinical isolates (2 × 105 CFU) were inoculated in 250 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB) [50]. Quick-RNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit was used to isolate the total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo, USA). The RNA was treated with DNase/RNase-Free water to remove genomic DNA. The concentration and optical absorbance of each extracted RNA were confirmed with Nanodrop (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) at 260 nm/280 nm and samples were kept at −80 °C to elicit DNA contamination from total isolated RNA. EasyScript® First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit was used to synthesize the cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Transgen/China). The cDNA reaction components including Random Primer (N9) in a volume of 1 µL, 2×ES Reaction Mix (10 µL), EasvScript®RT/RI Enzyme Mix (1 µL), RNase-free Water (Up to 20 µL), Eluted RNA (5 µL). qRT-PCR was performed by the SYBR Green gene expression assay [27]. In each sterile PCR tube, sample components of Real MODTM Green W2 2x qPCRmix in a volume of 10 µL, Forward Primer (10 µM) in a volume of 2.0 µL, Reverse Primer (10 µM) in a volume of 2.0 µL, Template DNA (4 µL), and DNase/RNase free water (up to 20 µL) were added. The thermal program was performed as follows: initial activation step, which was optimized at 95 °C for 10 min, 1 cycle; denaturation step, which was optimized at 95 °C, for 30 s; annealing was optimized at 60 °C, for 30 s; extension was optimized at 72 °C for 30 s. Denaturation, annealing, and extension steps were performed over 40 cycles. Then there was the final extension, which was optimized at 72 °C, for 5 min, 1 cycle. The 16S rRNA gene was used as a housekeeping gene, while the acrA gene was used as a target gene for E. coli. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

The primer sequences for the real time qPCR analysis.

| Genes | Type | Sequences (5′–3′) | Temperature (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 sRNA (reference gene) | Forward Reverse |

AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG CTGCTGCSYCCCGTAG |

50 52 |

| acrA gene (target gene) | Forward Reverse |

TTGAAATTCAGGAT CTTAGCCCTAACAGGATGTG |

53 57.2 |

4.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation using GraphPad Prism 9 software for Mac, www.graphpad.com (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test. For the gene expression, unpaired T-test was performed. A significant difference was considered at the level of p < 0.01. Data for the percentage of biofilm inhibiting activity of catechin were presented using Microsoft Excel.

5. Conclusions

Biofilm-forming E. coli places a significant burden on the health of the population. With a high rate of recurrence, E. coli becomes increasingly resistant to antimicrobial treatments and more difficult to eradicate. Catechin isolated from Canarium patentinervium Miq. exhibited strong biofilm inhibiting activity by reducing the expression of the biofilm-related acrA gene. This study highlights how important natural products are for treating infectious diseases that are resistant to the currently available antimicrobials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.; methodology, N.J. and Y.K.M.; software, A.F and N.J.; validation, M.R. and N.H.A.; formal analysis, A.F. and N.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Braz V.S., Melchior K., Moreira C.G. Escherichia coli as a Multifaceted Pathogenic and Versatile Bacterium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:548492. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.548492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desvaux M., Dalmasso G., Beyrouthy R., Barnich N., Delmas J., Bonnet R. Pathogenicity Factors of Genomic Islands in Intestinal and Extraintestinal Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:2065. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaper J.B., Nataro J.P., Mobley H.L.T. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Öztürk R., Murt A. Epidemiology of urological infections: A global burden. World J. Urol. 2020;38:2669–2679. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-03071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamm W.E., Norrby S.R. Urinary Tract Infections: Disease Panorama and Challenges. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183:S1–S4. doi: 10.1086/318850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina M., Castillo-Pino E. An introduction to the epidemiology and burden of urinary tract infections. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2019;11:1756287219832172. doi: 10.1177/1756287219832172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramírez-Castillo F.Y., Moreno-Flores A.C., Avelar-González F.J., Márquez-Díaz F., Harel J., Guerrero-Barrera A.L. An evaluation of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates in urinary tract infections from Aguascalientes, Mexico: Cross-sectional study. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2018;17:34. doi: 10.1186/s12941-018-0286-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galindo-Méndez M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018;6:6–14. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.93115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnert J.A., Karamian B., Nikaido H. Optimized Nile Red efflux assay of AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux system shows competition between substrates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3770–3775. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00620-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majumder S., Jung D., Ronholm J., George S. Prevalence and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from mastitic dairy cattle in Canada. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:222. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C., Liao X., Jiang H., Zhu H., Yue L., Li S., Fang B., Liu Y. Characteristics of Escherichia coli biofilm production, genetic typing, drug resistance pattern and gene expression under aminoglycoside pressures. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;30:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aziz M.A., Khan A.H., Adnan M., Ullah H. Traditional uses of medicinal plants used by Indigenous communities for veterinary practices at Bajaur Agency, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad Khan M.S., Ahmad I. Chapter 1—Herbal Medicine: Current Trends and Future Prospects. In: Ahmad Khan M.S., Ahmad I., Chattopadhyay D., editors. New Look to Phytomedicine. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2019. [(accessed on 13 March 2022)]. pp. 3–13. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012814619400001X. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leenhouts P.W., Kalkman C., Lam H.J. Burseraceae. Flora Malesiana—Series 1. Spermatophyta. 1955;5:209–296. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mogana R., Teng-Jin K., Wiart C. In Vitro Antimicrobial, Antioxidant Activities and Phytochemical Analysis of Canarium patentinervium Miq. from Malaysia. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011;2011:768673. doi: 10.4061/2011/768673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogana R., Adhikari A., Tzar M.N., Ramliza R., Wiart C. Antibacterial activities of the extracts, fractions and isolated compounds from Canarium patentinervium Miq. against bacterial clinical isolates. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020;20:55. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-2837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews J.M. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48:5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sartoratto A., Machado A.L.M., Delarmelina C., Figueira G.M., Duarte M.C.T., Rehder V.L.G. Composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from aromatic plants used in Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2004;35:275–280. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822004000300001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas B.T., Adeleke A.J., Raheem-Ademola R.R., Kolawole R., Musa O.S. Efficiency of some disinfectants on bacterial wound pathogens. Life Sci. J. 2012;9:752–755. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathur T., Singhal S., Khan S., Upadhyay D.J., Fatma T., Rattan A. Detection of biofilm formation among the clinical isolates of Staphylococci: An evaluation of three different screening methods. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;24:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02466-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajapaksha P., Ojo I., Yang L., Pandeya A., Abeywansha T., Wei Y. Insight into the AcrAB-TolC Complex Assembly Process Learned from Competition Studies. Antibiotics. 2021;10:830. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10070830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eicher T., Seeger M.A., Anselmi C., Zhou W., Brandstätter L., Verrey F., Diederichs K., Faraldo-Gómez J.D., Pos K.M. Coupling of remote alternating-access transport mechanisms for protons and substrates in the multidrug efflux pump AcrB. eLife. 2014;3:e03145. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daury L., Orange F., Taveau J.-C., Verchère A., Monlezun L., Gounou C., Marreddy R., Picard M., Broutin I., Pos K.M., et al. Tripartite assembly of RND multidrug efflux pumps. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobylka J., Kuth M.S., Müller R.T., Geertsma E.R., Pos K.M. AcrB: A mean, keen, drug efflux machine. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020;1459:38–68. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zgurskaya H.I., Nikaido H. AcrA is a highly asymmetric protein capable of spanning the periplasm. [(accessed on 10 December 2021)];J. Mol. Biol. 1999 285:409–420. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2313. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022283698923130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobbs E.C., Yin X., Paul B.J., Astarita J.L., Storz G. Conserved small protein associates with the multidrug efflux pump AcrB and differentially affects antibiotic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16696–16701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponchel F., Toomes C., Bransfield K., Leong F.T., Douglas S.H., Field S.L., Bell S.M., Combaret V., Puisieux A., Mighell A.J., et al. Real-time PCR based on SYBR-Green I fluorescence: An alternative to the TaqMan assay for a relative quantification of gene rearrangements, gene amplifications and micro gene deletions. BMC Biotechnol. 2003;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woese C.R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim Y.H., Yang I., Bae Y.-S., Park S.-R. Performance evaluation of thermal cyclers for PCR in a rapid cycling condition. BioTechniques. 2008;44:495–505. doi: 10.2144/000112705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Oliveira H.C., Pinto Garcia Junior A.A., Gromboni J.G.G., Farias Filho R.V., do Nascimento C.S., Arias Wenceslau A. Influence of heat stress, sex and genetic groups on reference genes stability in muscle tissue of chicken. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0176402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldeisen J.R., Wang T., Mitra D., Lee L.P. A Real-Time PCR Antibiogram for Drug-Resistant Sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray B.O., Flores C., Williams C., Flusberg D.A., Marr E.E., Kwiatkowska K.M., Charest J.L., Isenberg B.C., Rohn J.L. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: A Mystery in Search of Better Model Systems. [(accessed on 2 January 2022)];Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021 11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.691210. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcimb.2021.691210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittal S., Sharma M., Chaudhary U. Biofilm and multidrug resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2015;109:26–29. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010;7:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de la Fuente-Núñez C., Korolik V., Bains M., Nguyen U., Breidenstein E.B.M., Horsman S., Lewenza S., Burrows L., Hancock R.E.W. Inhibition of bacterial biofilm formation and swarming motility by a small synthetic cationic peptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2696–2704. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00064-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Famuyide I.M., Aro A.O., Fasina F.O., Eloff J.N., McGaw L.J. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of acetone leaf extracts of nine under-investigated south African Eugenia and Syzygium (Myrtaceae) species and their selectivity indices. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019;19:141. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2547-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Fuente-Núñez C., Cardoso M.H., de Souza Cândido E., Franco O.L., Hancock R.E.W. Synthetic antibiofilm peptides. [(accessed on 13 December 2021)];Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2016 1858:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.12.015. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005273615004137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gajdács M., Kárpáti K., Nagy Á.L., Gugolya M., Stájer A., Burián K. Association between biofilm-production and antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolates: A laboratory-based case study and a literature review. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2021;68:217–226. doi: 10.1556/030.2021.01487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryers J.D. Medical biofilm. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;100:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma D., Misba L., Khan A.U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019;8:76. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atanasov A.G., Zotchev S.B., Dirsch V.M., Supuran C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021;20:200–216. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adnan M., Patel M., Deshpande S., Alreshidi M., Siddiqui A.J., Reddy M.N., Emira N., De Feo V. Effect of Adiantum philippense Extract on Biofilm Formation, Adhesion with Its Antibacterial Activities Against Foodborne Pathogens, and Characterization of Bioactive Metabolites: An in vitro-in silico Approach. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:823. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burseraceae P.W., Leyden H.J.L. Leenhouts Dioecious, Rarely Monoecious Trees the Outer Side by Distinct, Closed Twigs, Petioles with Those in Twigs Mostly Amphivasal Mainly Sclerenchymatic XYLEM, Those in the Petioles and Petiolules Collateral and Consisting of Abundant Imparipinnat. [(accessed on 10 May 2022)]. Available online: https://repository.naturalis.nl/pub/532548.

- 44.Mogana R., Bradshaw T.D., Jin K.T., Wiart C. In Vitro antitumor Potential of Canarium patentinervium Miq. Acad J. Cancer Res. 2011;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mogana R., Teng-Jin K., Wiart C. Anti-Inflammatory, Anticholinesterase, and Antioxidant Potential of Scopoletin Isolated from Canarium patentinervium Miq. (Burseraceae Kunth) Evid.-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2013;2013:734824. doi: 10.1155/2013/734824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma Y., Ding S., Fei Y., Liu G., Jang H., Fang J. Antimicrobial activity of anthocyanins and catechins against foodborne pathogens Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Food Control. 2019;106:106712. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeon J., Kim J.H., Lee C.K., Oh C.H., Song H.J. The Antimicrobial Activity of (−)-Epigallocatehin-3-Gallate and Green Tea Extracts against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Isolated from Skin Wounds. [(accessed on 26 September 2014)];Ann. Dermatol. 2014 26:564–569. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.5.564. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25324647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chunmei D., Jiabo W., Weijun K., Cheng P., Xiaohe X. Investigation of anti-microbial activity of catechin on Escherichia coli growth by microcalorimetry. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;30:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Díaz-Gómez R., Toledo-Araya H., López-Solís R., Obreque-Slier E. Combined effect of gallic acid and catechin against Escherichia coli. LWT. 2014;59:896–900. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.06.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Y., Qu Y., Tang J., Chen J., Liu J. Tea Catechin Inhibits Biofilm Formation of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus. J. Food Qual. 2021;2021:8873091. doi: 10.1155/2021/8873091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hengge R. Targeting Bacterial Biofilms by the Green Tea Polyphenol EGCG. Molecules. 2019;24:2403. doi: 10.3390/molecules24132403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamilton-Miller J.T. Anti-cariogenic properties of tea (Camellia sinensis) J. Med. Microbiol. 2001;50:299–302. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee K.-M., Kim W.-S., Lim J., Nam S., Youn M., Nam S.-W., Kim Y., Kim S.-H., Park W., Park S. Antipathogenic Properties of Green Tea Polyphenol Epigallocatechin Gallate at Concentrations below the MIC against Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Food Prot. 2009;72:325–331. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-72.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z., Fan G., Hryc C.F., Blaza J.N., Serysheva I.I., Schmid M.F., Chiu W., Luisi B.F., Du D. An allosteric transport mechanism for the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump. eLife. 2017;6:e24905. doi: 10.7554/elife.24905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mogana R., Adhikari A., Debnath S., Hazra S., Hazra B., Teng-Jin K., Wiart C. The Antiacetylcholinesterase and Antileishmanial Activities of Canarium patentinervium Miq. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014:903529. doi: 10.1155/2014/903529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiehlbauch J.A., Hannett G.E., Salfinger M., Archinal W., Monserrat C., Carlyn C. Use of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards Guidelines for Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing in New York State Laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000;38:3341–3348. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.9.3341-3348.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.CLSI . 2021 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed. Volume 40. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2020. pp. 50–51. CLSI M100-ED29. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balouiri M., Sadiki M., Ibnsouda S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2015;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eloff J.N. A Sensitive and Quick Microplate Method to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Plant Extracts for Bacteria. Planta Med. 1998;64:711–713. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parvekar P., Palaskar J., Metgud S., Maria R., Dutta S. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of silver nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2020;7:105–109. doi: 10.1080/26415275.2020.1796674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozturk S., Ercisli S. Chemical composition and in vitro antibacterial activity of Seseli libanotis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;22:261–265. doi: 10.1007/s11274-005-9029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levison M.E. Pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial drugs. [(accessed on 15 May 2022)];Infect. Dis. Clin. 2004 18:451–465. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2004.04.012. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0891552004000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cantore P.L., Iacobellis N.S., De Marco A., Capasso F., Senatore F. Antibacterial Activity of Coriandrum sativum L. and Foeniculum vulgare Miller Var. vulgare (Miller) Essential Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:7862–7866. doi: 10.1021/jf0493122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saquib S.A., AlQahtani N.A., Ahmad I., Kader M.A., Al Shahrani S.S., Asiri E.A. Evaluation and Comparison of Antibacterial Efficacy of Herbal Extracts in Combination with Antibiotics on Periodontal pathobionts: An in vitro Microbiological Study. Antibiotics. 2019;8:89. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Toole G.A. Microtiter Dish Biofilm Formation Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2011;47:e2437. doi: 10.3791/2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sandasi M., Leonard C., Viljoen A. The effect of five common essential oil components on Listeria monocytogenes biofilms. Food Control. 2008;19:1070–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Djordjevic D., Wiedmann M., McLandsborough L.A. Microtiter Plate Assay for Assessment of Listeria monocytogenes Biofilm Formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:2950–2958. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2950-2958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Danish S., Shakil S., Haneef D. A simple click by click protocol to perform docking: AutoDock 4.2 made easy for non-bioinformaticians. EXCLI J. 2013;12:831–857. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yuan S., Chan H.S., Hu Z. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017;7:e1298. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kosari F., Taheri M., Moradi A., Alni R.H., Alikhani M.Y. Evaluation of cinnamon extract effects on clbB gene expression and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli strains isolated from colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:267. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06736-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.