Highlights

-

•

State and federal policy may help expand access to MOUD in residential treatment.

-

•

One-third of states have regulations for MOUD availability in residential treatment.

-

•

Most states with Medicaid SUD waivers have requirements for MOUD in residential settings.

Keywords: Residential substance use treatment, Medication for opioid use disorder, Medicaid 1115(a) waiver, Opioid use disorder, Buprenorphine

Abstract

Background

Mortality due to opioid use continues to increase; effective strategies to improve access to treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) are needed. While OUD medications exist, they are used infrequently and often not available in residential addiction treatment settings. CMS provides expanded opportunities for Medicaid reimbursement of treatment in residential facilities and requires states that request Medicaid SUD Waivers to provide a full continuum of care including medication treatment. The objective of this study was to assess how states facilitate access to OUD medications in residential settings and whether Medicaid requirements play a role.

Methods

Using a legal mapping framework, across the 50 states and DC, we abstracted data from state regulations in 2019 - 2020 and Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstration applications. We examined the temporal relationship between state regulations regarding medication-assisted treatment for OUD in residential settings and Section 1115(a) demonstrations.

Results

We identified variation in regulations regarding medication treatment for OUD in residential settings and possible spillover effects of the CMS requirements for Medicaid SUD Waivers. In 18 states with relevant regulations, regulatory approaches include identifying opioid medication treatment as a right, requiring access to OUD medication treatment, and establishing other requirements. 25 of 30 states with approved Section 1115(a) demonstrations included explicit requirements for OUD medication treatment access. Four states updated OUD medication treatment regulations for residential treatment settings within a year of applying for a Section 1115(a) demonstration.

Conclusions

State regulations and Medicaid program requirements are policy levers to facilitate OUD medication treatment access.

1. Introduction

The effects of the opioid crisis have grown steadily throughout the United States, with opioid-related overdoses and overdose deaths increasing since the early 2000s (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2018). In 2019, approximately 1.3 million Americans aged 12 years or older (0.6 percent) had an opioid use disorder (OUD) in the past year and an estimated 20.4 million (7.4 percent) had any type of substance use disorder (SUD) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020). Concerns about opioid use and other substances are growing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Between June 2019 and May 2020, the United States saw the highest rate of SUD-related overdose deaths ever recorded for a 12-month period, with overdose deaths associated with synthetic opioids increasing by 38.4 percent, compared to the same period between 2018 and 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Approximate costs associated with nonmedical opioid use in the United States from 2015 through 2018 were $631 billion or more, (Society of Actuaries, 2019) and the impact of OUD extends beyond the affected individual as indicated, for example, by the prevalence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (Pryor et al., 2017).

Effective treatments for OUD exist. Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) have been shown to increase retention in treatment; improve functioning; and decrease drug use, infectious disease transmission, criminal activities, and risk of overdose and death (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). One meta-analysis of thirty studies found that, compared with those receiving MOUD, untreated patients had elevated risk of all-cause mortality and overdose, and, after discharge, patients had greater risk of all-cause and overdose death (Ma et al., 2019). The medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of OUD include buprenorphine, buprenorphine-naloxone (collectively, buprenorphine), methadone, and naltrexone (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). All the approved medications for OUD are associated with improved outcomes (Timko et al., 2016).

Despite its efficacy, MOUD is underutilized (Jones et al., 2015; Jones & McCance-Katz, 2019). There is resistance to MOUD for both logistical and philosophical reasons (Stewart et al., 2021; Wakeman & Rich, 2018). Leadership from organizations that do not offer MOUD cite ideological opposition to medication and financial and staffing barriers as reasons MOUD is not offered (Stewart et. al., 2021). Many Residential SUD treatment settings do not provide MOUD (Huhn et al., 2020). The most recent National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) data indicate that, in 2019, only 2.2 percent of residential substance use treatment facilities were federally certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs) able to administer methadone and only 30.5 percent of residential treatment facilities prescribed buprenorphine (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Further, only 56.8 percent allowed entry to residents receiving OUD medications from another source, and nearly 15 percent explicitly did not accept any residents receiving MOUD (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

A lack of availability of MOUD in residential facilities increases risk of overdose because of reduced tolerance of opioids (Joudrey et al., 2019). A 2019 study found that one in ten drug overdose deaths involved an individual with past-month institutional release (O'Donnell et al., 2020). Institutional releases may include settings such as residential treatment facilities, as well as hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, long-term care facilities, and correctional institutions.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) provides guidelines for placement, continued stay, transfer, or discharge of patients along a continuum of care to effectively provide the appropriate level of SUD treatment when it is needed by the individual. This continuum includes, along with other settings and practices, residential substance use treatment and use of MOUD (Mee-Lee, 2013). Concerted efforts are underway to expand access to the full SUD treatment continuum and to move medication treatment into all parts of the continuum of care to better address the opioid crisis in the United States.

One such effort involves the use by states of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved Section 1115(a) demonstrations that permit the reimbursement of Medicaid services for residents of certain residential facilities, waiving under specified circumstances the long-standing rules that generally prohibit such reimbursement for those receiving services in so-called Institutions for Mental Disease (IMDs). Referred to as the “IMD exclusion,” this prohibition was originally intended to continue existing policies that ensured states remained solely responsible for funding inpatient psychiatric services. Potentially of greater consequence to care quality beyond basic access to residential care, to approve Medicaid Section 1115(a) SUD demonstrations, CMS now requires expansion of the state's SUD treatment continuum, inclusion or availability of MOUD in SUD treatment settings, and increased opportunities for Medicaid reimbursement of treatment in residential facilities to which the demonstration applies. The requirements for Section 1115(a) SUD demonstrations regarding availability of MOUD in residential SUD treatment facilities may have impacts beyond the populations directly affected by the state Medicaid demonstration. As public reimbursement to residential facilities increases through these Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstrations, state regulations may be implemented to facilitate access to MOUD treatment for other individuals beyond Medicaid beneficiaries in residential treatment.

1.1. Objective

The objective of this study is to examine state regulations for residential SUD treatment, Section 1115(a) demonstration applications, and the temporal relationship between state regulations addressing MOUD treatment in residential settings and Section 1115(a) demonstrations. While some states may update their Medicaid provider requirements for the Section 1115(a) demonstration, other states may create regulations that apply to all SUD residential facilities, for all patients regardless of whether they are Medicaid beneficiaries. Specifically, we hypothesize that the inclusion of requirements related to MOUD in residential treatment as part of a demonstration, even if only directly applicable to certain facilities or populations (i.e., Medicaid enrollees), means that it is more likely that other facilities and individuals in the state will experience spillover in the form of expanded requirements to offer MOUD in residential SUD treatment settings.

2. Methods

This study is part of a larger body of research examining state statutes, regulations, and policies involving oversight of behavioral health residential treatment facilities. The University IRB determined this study did not involve human subjects research. We conducted an environmental scan and interviewed experts in the field regarding state regulations for residential treatment. Based on those findings, we created a template that provided a coding structure for regulation data collected throughout the project. We used a legal mapping framework (Anderson et al., 2013) to define the scope and organize the approach. The legal mapping approach provides structured steps to follow in reviewing and compiling information from legal documents at a given point in time. We reviewed and abstracted data from two sources. First, we examined relevant statutes and regulations governing residential SUD treatment and/or licensing or certification from 51 jurisdictions. We refer to these as “state regulations”; they apply broadly to all facilities and exclude state Medicaid regulations. Secondly, we examined Medicaid requirements related to residential SUD treatment described in Section 1115(a) demonstration applications which apply only to treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Several parameters were placed around the scope of data collection to ensure consistency:

-

•

Residential treatment was defined as clinical treatment services provided in a 24-hour living environment, including withdrawal management treatment.

-

•

Only residential treatment facilities for adults were included.

-

•

We excluded residential facilities that are associated with the criminal justice system or that are treated by the state as inpatient settings.

-

•

We required that the state law or policy relate specifically to use of OUD medications in a residential facility, rather than more generally as part of SUD treatment (i.e., referenced in statute or regulation specific to residential treatment, as opposed to general SUD treatment requirement with no setting identified).

For each state, two coders abstracted information. Templates were compared for consistency among coders and discrepancies were resolved by the first author. We then prepared detailed summaries of (1) state regulations applying to all residential SUD treatment facilities in the state and (2) Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstration requirements for reimbursement for residential SUD treatment facilities, synthesizing the abstracted information. These data were collected and synthesized between May 2019 and May 2020. The state summaries were shared with the individual states for validation and revised as necessary. We then compared the state regulation data with the Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration information, including whether the 1115 demonstration had MOUD requirements for residential settings, as well as the start date of the demonstration to identify changes over time. We examined the timing of demonstration programs and how that related to changes in regulations regarding residential SUD treatment to identify the chronology of changes in each state. We looked at demonstrations in effect as of January 26, 2021.

3. Results

3.1. State regulations related to the use of MOUD in residential SUD treatment

Table 1 identifies the number of states that had licensing or other regulations, excluding Medicaid-specific requirements, regarding MOUD explicitly related to SUD residential treatment as of 2020 (see online Appendix A for additional detail). Most regulations refer to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) which may mean MOUD with concurrent counseling. Although MOUD without counseling is also an effective evidence-based treatment, we use MAT in describing the regulations because it is the term used in most regulations.

Table 1.

Number of States with Regulations Specific to Residential Treatment and MAT, 2020.

| Regulations | Number of States with Requirements for SUD Residential Treatment Facilities a |

|---|---|

| Rights to MAT in residential treatment | 11 |

| Provision of access to MAT | 8 |

| Other requirements for availability of MAT | 12 |

| TOTAL states with any requirement | 18 |

Abbreviation: MAT, medication-assisted treatment; SUD, substance use disorder.

aSome or all types of SUD residential treatment facilities in a given state were subject to these requirements.

Only about a third (18) of the states and the District of Columbia require MAT to be available in some way for SUD residential treatment as part of state regulations. The approaches taken vary by state, with states using one or more approaches to regulating MAT in residential facilities.

At least 11 states either establish an explicit right to receive MAT (Or. Admin. Rules 309-018-0115(1)(i)) or prohibit denial of services to individuals receiving medication treatment for OUD (D.C. Mun. Regs. Tit. 22, § 6300.11, n.d.) for some or all residential SUD treatment facilities. In Utah, for example, all service providers contracting with the Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health and all County Local Authority programs must provide written information to every treatment participant regarding “rights” to MAT (Utah Admin. Code r.523-2-4(1)).

At least eight states have regulations requiring that individuals receiving treatment for OUD either have access to medication in the facility or that outside access be provided (N.H. Admin. Rules He-P 826.16(e)(9)). Of these, at least one state requires, by regulation, that medication be transported by an outpatient facility to a residential facility if that is necessary for continuity of medication treatment. The same state does also expressly permit residential facilities to provide MAT “if the program's license specifically authorizes the services.” (Md. Code Regs. 10.63.03)

In addition to rights-based or access-focused regulations, at least 12 states have other regulatory requirements for the provision of MAT in SUD residential facilities in the state. Should a residential facility provide medication treatment for OUD, some states may impose specific requirements on those residential facilities. One approach is to explicitly allow a residential provider to offer MAT if it is suitably licensed (D.C. Mun. Regs. Tit. 22, § 6331.5, 6332.6, 6333.6). Some states require MAT in residential detoxification or withdrawal management facilities (Mich. Admin. Code r. 325.1387), and some require the provision of medication in such facilities but are not specific about it being medication for the treatment of OUD (e.g., “medication should be available to manage withdrawal/intoxication from all classes of abusable drugs” (25 Tex. Admin. Code § 448.902). Two state regulations provide examples regarding regulatory treatment of specific medications: (1) Alabama calls for availability of buprenorphine in a Level 3.7-D Medically Monitored Residential Detoxification Narcotic Treatment Program and allows for dispensing of methadone if the program is appropriately certified as an opioid treatment program (Ala. Admins Code r. Section 580-9-44-.28(e)); and (2) New York requires all certified SUD programs, including residential programs, to have all doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners waivered to provide buprenorphine (14 CRR-N.Y. 800.4(b)).

3.2. Medicaid Section 1115(a) SUD demonstrations with requirements for MOUD in residential settings

As of January 26, 2021, 30 states had approved Section 1115(a) demonstrations related to Medicaid reimbursement of SUD services in specified types of residential treatment facilities (e.g., short-term residential treatment for adults) (Table 2) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021). As with regulations, most demonstration documents refer to MAT and we, accordingly, use MAT in describing demonstration requirements. Participation requirements for these demonstrations have shifted over time, but at least 25 include a requirement that residential treatment providers eligible for reimbursement under the terms of the state's demonstration offer MAT on-site or facilitate access to MAT off-site. These MAT services must be provided within 12-24 months of SUD program demonstration approval by CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019b).

Table 2.

States with Approved Section 1115(a) Demonstrations Affecting Reimbursement of SUD Services in Residential Treatment Facilities, January 2021.

| State | Demonstration Title | CMS Approval Date Regarding SUD IMDa | Require Provision of MAT in Residential Treatment Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | Alaska Substance Use Disorder and Behavioral Health Program (SUD-BHP) | September 3, 2019 | Yes |

| California | California Medi-Cal 2020 | August 13, 2015 | Not directly |

| Colorado | Expanding the Substance Use Disorder Continuum of Care | November 13, 2020 | Yes |

| Delaware | Delaware Diamond State Health Plan | August 1, 2019 | Yes |

| District of Columbia | D.C. Behavioral Health Transformation | November 6, 2019 | Yes |

| Idaho | Idaho Behavioral Health Transformation | April 17, 2020 | Yes |

| Illinois | Illinois Behavioral Health Transformation | May 7, 2018 | Yes |

| Indiana | Healthy Indiana Plan | February 1, 2018 | Yes |

| Kansas | KanCare | August 7, 2019 | Yes |

| Kentucky | KY HEALTH | October 5, 2018 | Yes |

| Louisiana | Healthy Louisiana OUD/SUD Demonstration | February 1, 2018 | Yes |

| Maine | Maine Substance Use Disorder Care Initiative | December 22, 2020 | Yes |

| Maryland | Maryland Health Choice | December 22, 2016 | Not directly |

| Massachusetts | MassHealth | June 26, 2019 | Not directly |

| Michigan | Michigan 1115 Behavioral Health Demonstration | April 5, 2019 | Yes |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Substance Use Disorder System Reform | June 28, 2019 | Yes |

| Nebraska | Nebraska Substance Use Disorder Section 1115 Demonstration | June 28, 2019 | Yes |

| New Hampshire | New Hampshire SUD Treatment and Recovery Access | August 3, 2018 | Yes |

| New Jersey | New Jersey FamilyCare Comprehensive Demonstration | October 31, 2017 | Yes |

| New Mexico | New Mexico Centennial Care 2.0 1115 Medicaid Demonstration | May 21, 2019 | Yes |

| North Carolina | North Carolina's Medicaid Reform Demonstration | April 25, 2019 | Yes |

| Ohio | Ohio Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver for Substance Use Disorder Treatment | September 24, 2019 | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania Medicaid Coverage Former Foster Care Youth From a Different State & SUD Demonstration | June 28, 2018 | Yes |

| Rhode Island | Rhode Island Comprehensive Demonstration | December 20, 2018 | Yes |

| Utah | Utah Primary Care Network | November 9, 2017 | Yes |

| Vermont | Vermont Global Commitment to Health | June 6, 2018 | Yes |

| Virginia | The Virginia GAP and ARTS Delivery System Transformation | December 15, 2016 | Yes |

| Washington | Washington Medicaid Transformation Project | July 17, 2018 | Yes |

| West Virginia | West Virginia Creating a Continuum of Care for Medicaid Enrollees with Substance Use Disorders | October 6, 2017 | Yes |

| Wisconsin | Wisconsin BadgerCare Reform | October 31, 2018 | Yes |

This date is when CMS approved the Section 1115(a) demonstration involving Medicaid reimbursement of SUD services in residential treatment facilities considered to be Institutions for Mental Disease. The demonstration may have pre-existed that approval and may have been subsequently amended.

To comply with these participation requirements, states may change licensing procedures across all facilities, or may target Medicaid providers directly with new requirements for Medicaid participation. The Kansas demonstration also requires the state to update its licensure requirements to require availability of MAT on-site at residential treatment facilities (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019a). Two others, Virginia (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016) and West Virginia (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2017), expressly include pharmacotherapy for addiction as a covered service in residential treatment. The other three states may address MAT in some capacity but do not do so specifically in regard to residential treatment in the available Section 1115(a) CMS-approved documents.

3.3. The intersection of state regulations and state Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstrations

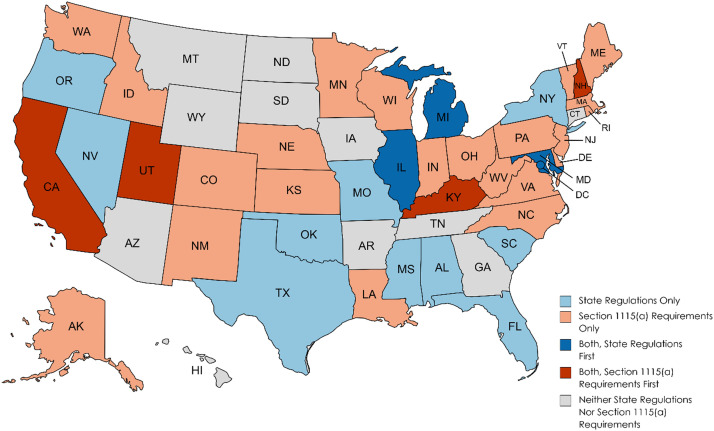

Our examination of state regulations and state Section 1115(a) demonstration applications found 40 states with requirements for MAT in either regulation, Section 1115(a) requirements, or both, as shown in Fig. 1 below. Details are found in Appendix B of the online appendices. Of the 40 states, ten did not have a Section 1115(a) demonstration but did have state regulations related to MAT in residential treatment. Twenty-two states had Section 1115(a) demonstrations with requirements for MAT in residential treatment but no evidence of broader state regulations regarding MAT in residential treatment. However, at least one of these states indicated in its approved implementation plan that licensure regulations would be amended to require that MAT be provided on-site (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019a). A total of eight states had both Medicaid 1115(a) demonstration requirements and state regulations for MAT in residential treatment, with the demonstration approval in place first in four states and the state regulations effective first in four states. In a total of four states, the regulation was effective within a year prior to or following the approval of the Section 1115(a) demonstration.

Fig. 1.

Timing of state regulations and Section 1115(a) requirements for MAT in residential treatment, by state, 2020.

4. Discussion

This study identifies both state regulations and Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstrations as important policy levers to facilitate access to MOUD treatment in residential settings. Understanding the interaction between these different approaches is important.

The common approaches in state regulations, identifying MAT as a right, requiring access to MAT in residential facilities, and establishing specific requirements for residential facilities that offer MAT, reveal that states have no single strategy. Moreover, within those categories of regulatory requirements, even greater differences are evident. Two clear examples include (1) the difference between the explicit establishment of rights to MAT in residential treatment compared to the indirect recognition of that by requiring facilities to provide written information regarding MAT; and (2) the difference between only requiring provision of medications for withdrawal management in residential settings which may not include medications to treat OUD (i.e., buprenorphine), contrasted to requiring all eligible providers to become waivered to provide buprenorphine. State licensing and behavioral health authorities clearly have approached this in different ways, ranging from directive to ambiguous.

Of the three regulatory approaches to MAT in SUD residential treatment, requiring access be provided either on- or off-site, is closest to what most Section 1115 demonstrations require for affected residential treatment facilities. The Section 1115(a) approval for at least one state indicated a requirement to amend its licensing regulations to require access to MAT in residential treatment. This reflects that promoting access to MAT in residential treatment was a key element in the design of the SUD-focused Section 1115 demonstrations.

Our comparison of the states with regulations and Section 1115 demonstrations examined the temporal relationship between the regulations and demonstrations to discern indications that Medicaid demonstrations may have spillover effects on state regulations regarding MAT. Of the 40 states that had either state regulation of MAT specific to residential facilities or the Medicaid demonstration, only 8 had both by the time we examined the requirements in regulations and the demonstrations. Attempting to disentangle cause and effect based on dates of promulgation and approval, respectively, however, is difficult because promulgation of regulations may be a lengthy process and may begin in anticipation of an approved demonstration. As this analysis demonstrates, it is possible to ascertain which became effective first and whether the two occurred in close temporal proximity. Qualitative research could uncover more detailed information about state agency motivation and decision-making processes embedded in these policies.

The 22 states that had Section 1115(a) demonstrations, but no state regulations specific to MAT in residential SUD treatment settings, may have (1) only Medicaid-specific regulations; (2) been in the process of developing state regulations; or (3) not attempted to broaden access beyond the demonstration using regulation. Because at least one of those states is required by the demonstration to amend its licensing regulations to reflect required access to MAT, the state regulations of these 22 states should be re-examined when at least 24 months have passed since demonstration approval. Half of the 22 states received CMS approval related to their Section 1115(a) demonstration less than 24 months before January 2021, when regulations were examined for this study.

The 10 states with regulations in place but no relevant Section 1115 demonstration as of January 2021 do include some states that subsequently approved demonstrations (e.g., Oklahoma (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), Oregon (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021)). Others may have applications underway, and, in some instances, states may have developed regulations in advance of their Section 1115(a) application. As with the 22 demonstration states without regulation of MAT in residential settings, the states without demonstrations in place also warrant future re-assessment, in this instance, to determine if regulations anticipate the state seeking an 1115(a) demonstration for Medicaid reimbursement for SUD treatment in residential settings.

Half of the 8 states with state regulations and a relevant Section 1115 demonstration had regulations in place with an effective date within a year of the demonstration approval, either before or after. Moreover, these regulations pertain, at least in part, to ensuring access to MAT in residential treatment. Given this also is required by the demonstration approval, we conclude that the two events (demonstration approval and regulation promulgation) may be related. Hence, for these states, the demonstration may be influencing the states’ regulatory requirements, effectively broadening the reach of the Medicaid demonstration.

4.1. Limitations

This study has limitations. States may use non-regulatory levers to effect change in the delivery of SUD treatment services, including contracts or policy documents. Thus, there are states where the statewide practice may be to provide MAT in some or all residential facilities without a regulation so requiring. Examples include Vermont, which, according to its approved demonstration documents, offered MAT on-site at all residential programs that are ASAM level 3.3 or higher before they were permitted to bill Medicaid, and California, based upon state staff comments received during validation (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2018). It also is not possible to attribute changes in regulations solely to the approval or pending approval of a Section 1115(a) demonstration because many states responded to the opioid crisis by passing emergency legislation or developing regulations which could include some of the provisions specific to use of MAT in residential treatment. We also do not address state Medicaid regulations that pertain to MAT in residential treatment because our objective was to examine the potential effects of the demonstrations beyond the realm of Medicaid. Finally, we do not address other CMS mechanisms such as State Plan Amendments or non-1115 waivers of the state plan, such as those related to rehabilitative services.

5. Conclusion and Policy Implications

Both to ensure that evidence-based SUD treatment is available in all settings and because there is increased risk of overdose upon departing residential treatment if medication for OUD is not available, all three types of medication for OUD should be accessible in residential settings treating individuals with OUD. Because of regulations governing methadone treatment, in particular, in most instances this would require partnerships between residential facilities and external opioid treatment programs. Partnering with OTPs allows residential treatment programs to facilitate access to methadone treatment and to ensure that individuals who would be engaged in methadone treatment upon discharge are already established on that medication. If care in residential settings is going to expand, we should ensure that appropriate, evidence-based care is offered and risks are minimized, which are considerations that the Section 1115(a) demonstrations attempt to address.

The Medicaid Section 1115(a) demonstrations can be laboratories for innovation that spread best practices to other settings and other states. It appears that the SUD demonstrations are influencing state regulations with broader applicability than the demonstrations themselves in at least four states, such as by requiring access to MAT, as well as other required demonstration components, such as requiring care coordination, appropriate assessment before placement, and treatment for co-occurring mental health conditions. Thus, these demonstrations have implications for the quality of OUD treatment, extending beyond requirements related only to medication treatment of OUD. Because of requirements related to treatment of co-occurring mental health conditions, they also have implications for spillover, because of culture change, into mental health treatment settings where individuals with OUD may receive SUD treatment.

As new Section 1115(a) demonstrations begin that are approved to target treatment of those with serious mental illness (SMI), the spillover effects of demonstrations may further expand. The integration of requirements for co-occurring treatment in SMI-focused demonstrations may have similar spillover effects on mental health regulations and oversight, as well as more broadly incorporating into the fabric of a state's mental health regulations requirements for structured placement assessments and others that we see in the Section 1115(a) SUD demonstrations.

In addition to the possibility of developing regulatory schemes that broaden the applicability of innovations in the field of SUD treatment and, possibly, mental health treatment, consideration needs to be given to the various levers available for enforcement. There typically are sanctions that states may apply for violation of facility licensing regulations or that Medicaid agencies may apply for not satisfying agency requirements. Enforcement relying on those sanctions, however, may be difficult, especially if there is considerable demand for increased SUD treatment and a state's enforcement resources are limited. This adds to a need for a mosaic of levers until MOUD is standard care and part of the cultural/professional expectation. Some of these levers might include increased enforcement by professional licensing boards for individual providers, increased requirements placed on Medicaid managed care entities, or enforcement by CMS on the states of their demonstration requirements.

Contributors

Margaret L. O'Brien: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Analysis, Writing-original draft, Maureen T. Stewart: Conceptualization, Analysis, Writing-original draft, Morgan C. Shields: Data collection, Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Mackenzie White: Data collection, Writing – review and editing, Joel Dubenitz: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Judith Dey: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Norah Mulvaney-Day: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Analysis, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

This project was funded by ASPE Contract HHSP2332016000231 to IBM Watson Health; Maureen Stewart also received funding from NIH NIDA P30DA035772; Morgan Shields also received funding from grants T32AA007567 and T32MH109433.

Declarations of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100087.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Anderson E.D., Tremper C., Thomas S., Wagenaar A.C. Measuring statutory law and regulations for empirical research. Public Health Law Research. 2013:237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020, December 18. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19.https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics . CDC WONDER Online Database. 2018. Multiple cause of death data 1999-2017.https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2016. CMS Approval- VA GAP ARTS SUD Demonstration Amendment (12/15/2016)https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/va/Governors-Access-Plan-GAP/va-gov-access-plan-gap-appvl-amdmnt-12152016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2017. WV Creating a Continuum of Care for Medicaid Enrollees with SUDs STCs.https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/wv/continuum-care/wv-creating-continuum-care-medicaid-enrollees-substance-creating-continuum-sud-stcs-20171010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2018. CMS Approval- Demonstration Amendment June 2018.https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/vt/Global-Commitment-to-Health/vt-global-commitment-to-health-cms-appvl-demo-amend-06062018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2019. CMS Approval- Substance Use Disorder Implementation Plan.https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ks/KanCare/ks-kancare-cms-appvl-sud-implementation-plan-20190807.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2019, July. Delaware Diamond State Health Plan Demonstration Approval.https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/de-dshp-ext-appvl-07312019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Huhn A.S., Hobelmann J.G., Strickland J.C., Oyler G.A., Bergeria C.L., Umbricht A., Dunn K.E. Differences in availability and use of medications for opioid use disorder in residential treatment settings in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.M., Campopiano M., Baldwin G., McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55–e63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.M., McCance-Katz E.F. Characteristics and prescribing practices of clinicians recently waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114(3):471–482. doi: 10.1111/add.14436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joudrey P.J., Khan M.R., Wang E.A., Scheidell J.D., Edelman E.J., McInnes D.K., Fox A.D. A conceptual model for understanding post-release opioid-related overdose risk. Addict. Sci. Clin. Practice. 2019;14(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation . 2021. Medicaid waiver tracker: approved and pending section 1115 waivers by state. KFF.https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/ [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Bao Y.-P., Wang R.-J., Su M.-F., Liu M.-X., Li J.-Q., Degenhardt L., Farrell M., Blow F.C., Ilgen M., Shi J., Lu L. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1868–1883. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee D. 3rd Ed. American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-Occurring Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell J., Gladden R.M., Mattson C.L., Hunter C.T., Davis N.L. Vital Signs: characteristics of drug overdose deaths involving opioids and stimulants — 24 states and the district of Columbia, January–June 2019. Morbid. Mortal. Weekly Report. 2020;69(35):1189–1197. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor J.R., Maalouf F.I., Krans E.E., Schumacher R.E., Cooper W.O., Patrick S.W. The opioid epidemic and neonatal abstinence syndrome in the USA: A review of the continuum of care. Arch. Disease Childhood - Fetal Neonatal Edition. 2017;102(2):F183–F187. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society of Actuaries . 2019. Economic Impact of Non-Medical Opioid Use in the United States.https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/research-report/2019/econ-impact-non-medical-opioid-use.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R.E., Wolk C.B., Neimark G., Vyas R., Young J., Tjoa C., Kampman K., Jones D.T., Mandell D.S. It's not just the money: The role of treatment ideology in publicly funded substance use disorder treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2018. Medicaid Coverage of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders and of Medication for the Reversal of Opioid Overdose (HHS Publication No. SMA-18-5093)https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/medicaidfinancingmatreport_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2019. Table 4.11.b. Provision of MAT for opioid use disorder, by type of care: Column percent, 2019.https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-survey-substance-abuse-treatment-services-n-ssats-2019-data-substance-abuse [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . 2020. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55)https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR090120.htm [Google Scholar]

- Timko C., Schultz N.R., Cucciare M.A., Vittorio L., Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. J. Addict. Dis. 2016;35(1):22–35. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2020, December. Oklahoma Waiver Approval Letter.https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/ok-imd-waiver-smi-sud-ca.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2021. Oregon Waiver Approval Letter.https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/or-health-plan-sud-demo-ca.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman S.E., Rich J.D. Barriers to Medications for Addiction Treatment: How Stigma Kills. Subst. Use Misuse. 2018;53(2):330–333. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1363238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.