Abstract

Ammonia switch-off is the immediate inactivation of nitrogen fixation that occurs when a superior nitrogen source is encountered. In certain bacteria switch-off occurs by reversible covalent ADP-ribosylation of the dinitrogenase reductase protein, NifH. Ammonia switch-off occurs in diazotrophic species of the methanogenic Archaea as well. We showed previously that in Methanococcus maripaludis switch-off requires at least one of two novel homologues of glnB, a family of genes whose products play a central role in nitrogen sensing and regulation in bacteria. The novel glnB homologues have recently been named nifI1 and nifI2. Here we use in-frame deletions and genetic complementation analysis in M. maripaludis to show that the nifI1 and nifI2 genes are both required for switch-off. We could not detect ADP-ribosylation or any other covalent modification of dinitrogenase reductase during switch-off, suggesting that the mechanism differs from the well-studied bacterial system. Furthermore, switch-off did not affect nif gene transcription, nifH mRNA stability, or NifH protein stability. Nitrogenase activity resumed within a short time after ammonia was removed from a switched-off culture, suggesting that whatever the mechanism, it is reversible. We demonstrate the physiological importance of switch-off by showing that it allows growth to accelerate substantially when a diazotrophic culture is switched to ammonia.

Nitrogen fixation is an energy-intensive process. For every electron that flows to dinitrogen, two ATP molecules are hydrolyzed (9). For this reason, nitrogen fixation is rigorously regulated. Regulation at the transcriptional level is understood in some detail in bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae. In many species, regulation occurs posttranslationally as well. Rapid posttranslational regulation, called ammonia switch-off, presumably saves the cell from the continued energy expenditure that would occur if nitrogenase proteins remained active after a superior nitrogen source such as ammonia is encountered. Switch-off occurs in a variety of diazotrophic bacteria (31) and has also been demonstrated in the methanogenic archaeal species Methanosarcina barkeri (29, 30) and Methanococcus maripaludis (reference 26 and our unpublished results). In many bacteria, such as Rhodospirillum rubrum, switch-off occurs by reversible covalent ADP-ribosylation of the dinitrogenase reductase protein, NifH (31, 36).

The first recognition of nitrogen fixation in methanogenic Archaea was in Methanosarcina barkeri (34) and Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus (6). Since then it has become clear that the basic mechanism of nitrogen fixation is similar to that in Bacteria, because homologues of the genes encoding the main enzymes of nitrogen fixation in Bacteria are present (10, 38, 39). In M. maripaludis, a variety of new genetic tools (e.g., reference 7) allowed for the identification of a complete nif gene cluster, eight genes that belong to a single operon that is required for diazotrophic growth (25; see also Fig. 1). The same arrangement of genes is found, at least in part, in all diazotrophic methanogens characterized (27). These genes include those that encode the dinitrogenase-dinitrogenase reductase complex, nifH, nifD, and nifK, as well as other known structural proteins, i.e., genes nifE and nifN, which are thought to function as a molecular scaffold in the assembly of an essential cofactor of nitrogenase. In addition, the nif gene clusters of diazotrophic methanogens contain two regulatory genes, novel homologues of the glnB family. Formerly named glnBi and glnBii, it has recently been proposed that these genes be renamed nifI1 and nifI2 (1).

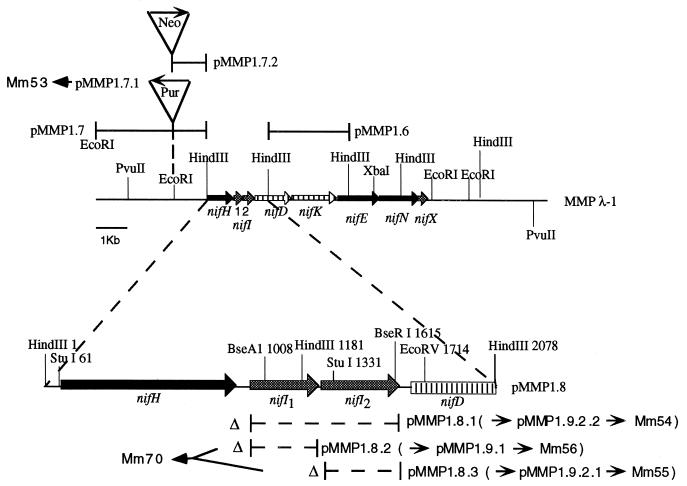

FIG. 1.

Diagram showing the nif gene region of M. maripaludis and the construction of mutations. Map numbers after restriction sites indicate base pairs from the leftmost HindIII site. A “Δ” symbol followed by a dashed segment delineates a deleted region.

The GlnB family of nitrogen sensor-regulator proteins plays a central role in nitrogen-regulatory processes in bacteria (for reviews, see references 33 and 35). GlnB was first characterized in Escherichia coli, where it is known as the PII protein (8). Recent work (19–22, 24) has investigated the function of PII in detail. It now appears that PII mediates the response to at least two effector molecules that reflect the nitrogen state of the cell: glutamine and 2-ketoglutarate. Glutamine levels determine whether PII is modified by uridylylation, while 2-ketoglutarate seems to affect PII activity by direct binding. PII, in turn, affects the mechanisms governing transcriptional regulation in response to nitrogen, as well as posttranslational regulation of glutamine synthetase.

Recently, the known distribution of GlnB family members and the nitrogen-regulatory roles that they play have expanded. In Bacteria, GlnB homologues are known in a variety of Proteobacteria (12, 32, 37) and in cyanobacteria (13). Some bacteria contain two GlnB paralogues, GlnB and GlnK, that have similar yet distinct functions (2–4, 16, 18, 41). Most known bacterial GlnB homologues share conserved domains distributed throughout the protein (26, 33, 35). Among these domains is the T-loop, where the site of uridylylation is situated and where interactions with other proteins are thought to occur (23, 42). GlnB family members are known in certain plants too; these proteins are in the chloroplast and are therefore of likely bacterial origin (17).

Genes encoding GlnB homologues are known in the Archaea as well. These archaeal genes fall into three subfamilies. One subfamily is the “typical” subfamily because it is closely related to the bacterial GlnB homologues (GlnB and GlnK) and contains the same conserved domains, including the T-loop (26). The functions of the typical GlnB homologues in the Archaea have not been studied. The other two subfamilies of GlnB homologues are encoded in the nif gene clusters of diazotrophic methanogens and occur adjacent to one another, between nifH and nifD (10, 25, 39). Formerly named glnBi and glnBii, it has recently been proposed that these genes be renamed nifI1 and nifI2 (1) (see also Fig. 1). Each of these subfamilies is phylogenetically divergent (10) and differs especially in the T-loop (26). The divergent nature of NifI1 and NifI2 compared to the other GlnB family members suggests that their modes of covalent modification, if any, and their interactions with other proteins may be novel.

We have studied the function of nifI1 and nifI2 in M. maripaludis. Previous work (25) suggested that these genes were not involved in the regulation of nif gene expression at the transcriptional level, which occurs by a repression mechanism (11). Subsequently, we (26) demonstrated that one of the nifI genes, or both, was required for ammonia switch-off. Here we show that both nifI genes are required for switch-off. We also find that the mechanism of switch-off differs from the well-characterized covalent modification of nitrogenase reductase that occurs in some bacteria but that the switch-off does occur by a reversible mechanism. We also demonstrate the physiological importance of switch-off during the transition from diazotrophic growth to growth on ammonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of cultures.

M. maripaludis strain LL and its derivatives were grown as described previously (25). Diazotrophic growth and acetylene reduction assays were carried out as described earlier (26). Nitrogen-free medium (7) was modified by the addition of vitamins (5), sodium acetate · 3H2O (1.4 g/liter), and dithiothreitol (3 mM). Puromycin was used at 2.5 μg/ml. Neomycin sulfate was used in liquid medium at 1 mg/ml and in solid medium at 500 μg/ml.

Construction of nifI mutants.

Phage, plasmids, and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. In-frame deletions of nifI1 and nifI2 were created by reverse PCR using pMMP1.8 (26) (Fig. 1) as a template. Primers used for the nifI1 deletion were 5′-GAAGATCTAGATCATGCGGATTATAAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAGATCTTACTGCTCTAATCATTTTC-3′ (reverse). PCR was done with 30 cycles of 93°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The primers introduced BglII sites (underlined) into the PCR product, which was digested with BglII, gel purified, and ligated. The resulting plasmid, pMMP1.8.2 (Fig. 1) encoded the first seven and the last five amino acids of nifI1 with the central 93 amino acids replaced by Arg-Ser. The same strategy was used for the nifI2 deletion, with primers 5′-GAAGATCTGGAGAAGCTGCAATTTAAGC3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAGATCTCTCTTTCATATAATCACC-3′ (reverse). The nifI2 deletion plasmid, pMMP1.8.3 (Fig. 1) encoded the first three and the last five amino acids of nifI2 with the central 113 amino acids replaced by Arg-Ser. Construction of pMMP1.8.1 (Fig. 1), with an in-frame deletion of both nifI1 and nifI2, has been described (26). All deletion constructs were verified by sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Phage, plasmids, and M. maripaludis strains

| Phage, plasmids, and strains | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Phage Mmpλ-1 | M. maripaludis genomic library clone containing the nif operon | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS(+) | KS(+) cloning vector; Amr | Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif. |

| pMBSN | APH3′II Neo resistance gene with mcr promoter and terminator; Amr Neor | 1a |

| pMMP1.6 | 2.9-kb HindIII fragment from Mmpλ-1 in pBluescript KS(+) with 3′ portion of nifD, all of nifK and 5′ portion of nifE; Amr | 25 |

| pMMP1.7 | 3.4-kb region upstream from nifH; Amr | 26 |

| pMMP1.7.1 | Purr cassette in pMMP1.7; Amr Purr | 26 |

| pMMP1.7.2 | Deletion of region upstream of EcoRI site of pMMP1.7 and insertion of Neor cassette; Amr Neor | This study |

| pMMP1.7.2.1 | Insertion of HindIII fragment of pMMP1.8.2 into pMMP1.7.2; ΔnifI1, Amr Neor | This study |

| pMMP1.8 | nifH through the middle of nifD in pBluescript; Amr | 26 |

| pMMP1.8.1 | In-frame deletion of nifI1 and nifI2; Amr | 26 |

| pMMP1.8.2 | In-frame deletion of nifI1; Amr | This study |

| pMMP1.8.3 | In-frame deletion of nifI2; Amr | This study |

| pMMP1.9.1 | Upstream region with Purr cassette through middle of nifD with nifI1 deletion; Amr Purr | This study |

| pMMP1.9.2 | Upstream region with Purr cassette through middle of nifD with nifI2 deletion; Amr Purr | This study |

| pMMP1.9.2.1 | pMMP1.9.2 with additional 3′ flanking DNA from pMMP1.6; Amr Purr | This study |

| M. maripaludis | ||

| LL | Wild type | 25 |

| Mm53 | nifI+ control strain with Purr upstream of nifH; Purr | 26 |

| Mm54 | Deletion of nifI1 and nifI2; Purr | 26 |

| Mm55 | Deletion of nifI2; Purr | This study |

| Mm56 | Deletion of nifI1; Purr | This study |

| Mm61 | Insertion of Neor cassette in nifD; Neor | 26 |

| Mm70 | ΔnifI1, nifI2+/ΔnifI2, nifI1+; Neor Purr | This study |

To prepare for the introduction of the deletion constructs into M. maripaludis, the entire inserts of pMMP1.8.2 and pMMP1.8.3 were recovered by partial or complete HindIII digestion, and each was ligated into the HindIII site of pMMP1.7.1 (26) (Fig. 1), which contains a puromycin resistance marker (Pur) (14) in the region upstream of nifH. The resulting plasmids were pMMP1.9.1 and pMMP1.9.2, respectively. In the case of pMMP1.9.2, additional DNA was added (to facilitate later recombination) to the downstream end by cloning the HindIII fragment of pMMP1.6 (26) into the downstream-most HindIII site to yield pMMP1.9.2.1 (Fig. 1). pMMP1.9.1 and pMMP1.9.2.1 were transformed (40) into M. maripaludis strain Mm61 (26), which contains a neomycin resistance marker in the EcoRV site of nifD in an otherwise wild-type background. Transformants were selected for puromycin resistance and screened for neomycin sensitivity and then screened by Southern analysis to verify the integration of the constructs into the chromosome by double homologous recombination, replacing the wild-type nifI region with the mutations. The nifI1 deletion strain is designated Mm56, and the nifI2 deletion strain is designated Mm55. Strain Mm54, containing a deletion of both nifI genes, has been described, as has Mm53, a control strain containing the puromycin resistance marker in an otherwise wild-type background (26).

For genetic complementation, a strain was constructed that contained wild-type and deletion alleles of both nifI genes. Our strategy was to transform a ΔnifI2, nifI1+ strain with a ΔnifI1, nifI2+ construct. First, the EcoRI fragment of pMMP1.7 (26) was removed, and a neomycin resistance (Neo) EcoRI cassette from pMBSN (1a) introduced in its place, creating pMMP1.7.2 (Fig. 1). The HindIII insert of pMMP1.8.2 was then introduced into the HindIII site of pMMP1.7.2 to yield pMMP1.7.2.1. This plasmid, containing the nifI1 deletion construct marked by neomycin resistance, was transformed into Mm55, which contained the nifI2 deletion construct marked by puromycin resistance. Selection for both drug resistances yielded Mm70. Southern analysis confirmed that a single crossover event had occurred to the left of the two nifI regions and that the strain contained both constructs.

Reversibility of switch-off.

Strains Mm53 and Mm54 were grown on N2 to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) between 0.20 and 0.25. These cultures were diluted 2.3-fold into fresh nitrogen-free medium for continued growth on N2, and 8-fold into nitrogen-free medium containing 10 mM NH4Cl for growth on ammonia. These cultures were allowed to grow to an OD600 between 0.20 and 0.25. Acetylene (0.1%) was then added (time zero), cultures were further incubated, and acetylene reduction assays were conducted for the remainder of the experiment. At 1 h 8 min, 10 mM NH4Cl was added to the cultures growing on N2. At 2 h 16 min, ammonia was removed from all four cultures by centrifuging for 5 min at 3,000 × g, discarding the supernatant, resuspending the pellet in fresh nitrogen-free medium, and repeating the process. The ammonia removal procedure took 39 min, after which time the cultures were further incubated.

Western analysis of NifH protein.

Cultures were grown with N2 or ammonia to an OD660 of approximately 0.2. NH4Cl (10 mM) was added to diazotrophic cultures, and samples (1 ml) were withdrawn at time intervals and extracted by trichloroacetic acid precipitation as described elsewhere (43). The samples were analyzed by low cross-linker sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with 11.5% total acrylamide (30:0.174 acrylamide–N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide) on minigels. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins onto Sequi-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) was done in a Mini Trans-Blot eletrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad) for 30 min at 100 V in a buffer of 25 mM Tris–192 mM glycine (pH 8.3). Western blots were probed with NifH antibody using chemiluminescent detection (Amersham). NifH antibody and R. rubrum extracts were kindly provided by P. Ludden.

Northern analysis of nif mRNA.

Diazotrophic cultures (35 ml) were grown in 180-ml bottles to OD660 of approximately 0.25. Samples (5 ml) were withdrawn anaerobically by syringe immediately before, and at various intervals after, the addition of NH4Cl (1 mM). Samples were injected into stoppered anaerobic tubes, placed on ice, and centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Tubes were unstoppered, supernatant was removed, and the pellet processed with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's directions, except that the cell pellet was resuspended in 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M trisodium citrate). Northern analysis was performed using a probe for nifH as described earlier (25).

RESULTS

Both nifI genes are required for ammonia switch-off.

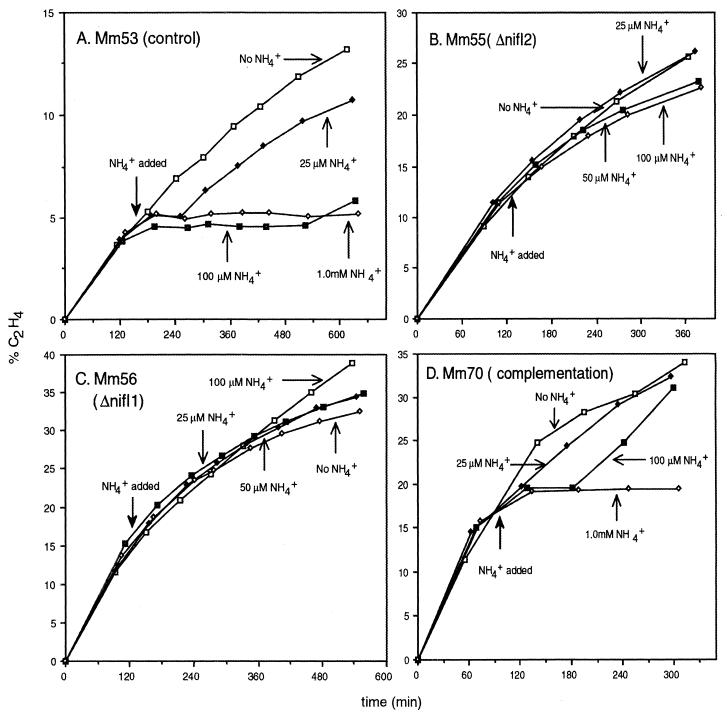

We demonstrated previously that ammonia switch-off occurs in M. maripaludis and that it is eliminated in a mutant that lacks both nifI (nif-cluster glnB) genes (26). Here we extend these observations by testing the role of each nifI gene individually. We constructed four strains of M. maripaludis (Fig. 1). Mm53, the control strain, contained the wild-type nifI region and a puromycin resistance marker that was placed near the nif gene cluster but did not disrupt it. Mm55 was the same except that nifI2 was disrupted by an in-frame deletion mutation. Similarly, in Mm56 nifI1 was disrupted. Finally, Mm70 was a merodiploid that combined both constructs for complementation purposes (see Materials and Methods). We grew cultures on N2 and used the acetylene reduction assay to monitor nitrogenase activity before and after addition of ammonia. Ammonia switch-off occurred in the control strain (Fig. 2A) as demonstrated previously (26). Nitrogenase activity disappeared completely within 30 min of ammonia addition. When low amounts of ammonia were used, nitrogenase activity resumed after a time, presumably when the ammonia became depleted. In contrast, in-frame deletion mutations of either nifI1 or nifI2 completely eliminated ammonia switch-off (Fig. 2B and C), suggesting that a null mutation in either gene was sufficient to destroy the function. To confirm that in each case the phenotype was due to the intended mutation, we constructed Mm70 in which each nifI mutation was complemented. This strain combined the two constructs used to produce the individual mutations, such that ΔnifI1 was complemented by nifI1+ and ΔnifI2 was complemented by nifI2+. Ammonia switch-off was restored (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that the two nifI mutations belonged to different genetic complementation groups. (The apparent reduced sensitivity of Mm70 to ammonia may actually be due to slightly different assay conditions.) These results show that both nifI genes are required for ammonia switch-off.

FIG. 2.

Effect of ammonia addition on nitrogenase activity in M. maripaludis strains. The percent C2H4 refers to the accumulated ethylene as a percentage of total acetylene plus ethylene.

Switch-off does not involve detectable covalent modification of the nitrogenase reductase protein.

The only well-understood mechanism for switch-off occurs in bacteria such as R. rubrum, where covalent ADP-ribosylation of NifH produces a gel mobility shift detectable by Western blotting (e.g., reference 15). In M. maripaludis, we found that the gel mobility of NifH was the same before and after switch-off (Fig. 3). In contrast, we could easily distinguish NifH proteins in extracts of active and switched-off cells of R. rubrum. These results show that in M. maripaludis, switch-off does not involve detectable covalent modification of the dinitrogenase reductase protein. Also notable was the observation that NifH was present for 2 h (Fig. 3) and even up to 6 h (not shown) without any decrease in band intensity. Therefore, switch-off does not involve NifH protein degradation. NifH mobility and band intensity were the same in Mm54 (ΔnifI1-nifI2; data not shown) as Mm53 (nifI+).

FIG. 3.

(Top) Western blot of NifH. C, controls with extract from active (lane 1) and switched-off (lane 2) R. rubrum. One subunit of the homodimer is modified. NH4+, ammonia-grown M. maripaludis (Mm53, nifI+). The remaining lanes show N2-grown M. maripaludis (Mm53, nifI+) immediately before (0 min) and at various intervals after the addition of NH4+ (10 mM). (Bottom) Nitrogenase activity before and after the addition of NH4+ in the same experiment. ♦, Mm53 (nifI+); ▪, Mm54 (ΔnifI1-nifI2).

Switch-off is reversible.

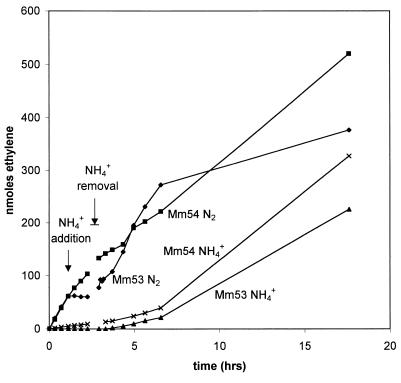

In many bacteria, including R. rubrum, switch-off is reversible, that is, nitrogenase proteins that have been inactivated can be restored to activity. We were interested in determining whether reversibility was the case in M. maripaludis as well. We grew Mm53 (nifI+) on N2 and added ammonia to establish switch-off. We then removed ammonia by centrifugation and resuspension of the cells. High nitrogenase activity was restored within a short time after removal of ammonia (Fig. 4, Mm53 N2). We compared this result to a culture that was treated the same except that it was grown on ammonia for three doublings prior to the removal of ammonia; such a culture should require derepression of nif gene expression and synthesis of new nitrogenase proteins to regain activity. This culture (Mm53 NH4+) had low nitrogenase activity after removal of ammonia and gained high activity only at least 4 h later. As expected, Mm54 (ΔnifI1-nifI2) growing on N2 did not switch off and retained nitrogenase activity throughout the experiment (Mm54 N2). Mm54 grown for three doublings on ammonia (Mm54 NH4+) had low nitrogenase activity from the outset but otherwise behaved like Mm53 NH4+. The low nitrogenase activity in Mm53 NH4+ and Mm54 NH4+ can be attributed to nitrogenase left from the initial N2 stage in each case. These results show that the reversal of switch-off occurs quickly, apparently involving reactivation of existing nitrogenase.

FIG. 4.

Effect of ammonia removal on nitrogenase activity. Mm53 (nifI+) and Mm54 (ΔnifI1-nifI2) were grown and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. At time zero the cultures were growing on N2 (Mm53 N2 and Mm54 N2) or NH4+ (Mm53 NH4+ and Mm54 NH4+). NH4+ was added to nitrogen-fixing cultures and was removed from all cultures at the times indicated.

Switch-off does not affect nif mRNA.

In previous work (25) we determined that the presence or absence of nifH mRNA was not affected by a transposon insertion in nifH that eliminated nifI expression through polarity. Thus, in a mutant that was effectively nifI, mRNA that hybridized to a nifH probe was present in N2-grown cells and absent in ammonia-grown cells, as is the case in the wild-type strain. We extended this observation by monitoring nifH mRNA levels by Northern blot at time intervals after adding ammonia to cultures growing on N2. Combining the data from two experiments (not shown), we were able to estimate an mRNA half-life of between 2 and 3 min in both Mm53 (nifI+) and Mm54 (ΔnifI1-nifI2). These observations indicate that the nifI genes have no marked effect on nif gene transcription or nifH mRNA stability and that switch-off operates entirely at a post-mRNA level.

Physiological role of ammonia switch-off.

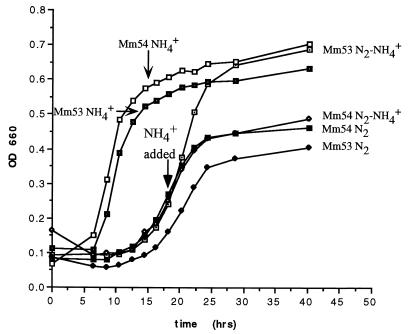

Having mutants that lacked ammonia switch-off enabled us to determine the physiological importance of this regulatory phenomenon. Presumably, a lack of ammonia switch-off would prolong the energy expenditure associated with an active nitrogenase system, resulting in a retardation of growth. We tested this hypothesis by monitoring growth after ammonia addition in cultures capable of ammonia switch-off (Mm53) and incapable of it (Mm54). Figure 5 shows that the two cultures grew at the same rates under constant conditions, relatively fast with ammonia and more slowly with N2. However, the two strains differed in their responses when ammonia was added to cultures growing on N2. In Mm53, growth accelerated rapidly after ammonia addition, becoming parallel to cultures grown with ammonia from the start. In contrast, the growth of Mm54 remained the same as that of cultures continuing to grow on N2. These results show that ammonia switch-off performs an important physiological role for the cell, allowing it to take immediate advantage of ammonia as a superior nitrogen source without being retarded by the continuing ATP drain of active nitrogenase proteins. It is notable that the growth of the mutant after ammonia addition is nearly identical to its continued growth on N2. The mutant is no longer nitrogen limited (nif mRNA disappears [see above]) and is presumably energy limited. This observation seems to reflect an exquisite regulation of nitrogenase activity in the wild-type strain that balances the gain from nitrogen assimilated against the cost in energy expended.

FIG. 5.

Growth of M. maripaludis strains with ammonia (NH4+), dinitrogen (N2), or the addition of ammonia to cultures growing on dinitrogen (N2-NH4+). The values are averages from at least three cultures.

DISCUSSION

Mechanism of switch-off.

In M. maripaludis, we have shown that ammonia switch-off is similar to that in R. rubrum and other bacteria in that it occurs quickly, is quickly reversible, and takes place at a post-mRNA level. However, the mechanism of switch-off appears novel and, unlike the well-understood ADP-ribosylation system, does not involve detectable covalent modification of nitrogenase reductase. The reversibility of the system is consistent with our observations that transcription and mRNA stability are not affected and that the NifH protein is not degraded during switch-off. Reversibility also eliminates the degradation of any other Nif protein as a possible mechanism. The remaining possibilities include the noncovalent association of a nitrogenase protein with another factor, reversible covalent modification of a Nif protein other than NifH, or reversible covalent modification of NifH forming a protein that is indistinguishable from unmodified NifH in our SDS-PAGE gel. These possibilities will be the subjects of future studies. It should be noted that switch-off mechanisms that do not involve detectable covalent modification of nitrogenase reductase have been demonstrated in certain Bacteria as well (e.g., reference 44) and in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri (30), but in no case is the mechanism understood.

Role of the NifI gene products.

Despite our lack of knowledge regarding the immediate mechanism, we have shown here that the nifI genes are involved in ammonia switch-off in M. maripaludis. Thus, the repertoire of various GlnB homologues in nitrogen regulation is expanded further—in addition to regulating the transcription of nitrogen-metabolic genes and glutamine synthetase activity in Proteobacteria, they also regulate ammonia switch-off in M. maripaludis. Recently, a role for GlnB in the regulation of the ADP-ribosylation system of R. rubrum has been reported as well (45).

The finding that both nifI genes are required in the same regulatory pathway is interesting. In Bacteria multiple GlnB homologues exist as well, but their functions either overlap or are completely distinct mechanistically. In E. coli, for example, the function of either GlnB or GlnK in the regulation of glutamine synthetase is partially redundant with the other paralogue, so that the absence of one only partially affects function (3, 4). On the other hand, in K. pneumoniae, the function of GlnK in nif regulation is unique and GlnB has only an indirect function in this pathway (16, 18). The situation in M. maripaludis suggests either that NifI1 and NifI2 are both required for a common step in ammonia switch-off or that each gene is required for a different step that is essential in the same pathway.

The divergent nature of the nifI genes at the amino acid sequence level is notable. Since they differ from typical glnB genes and from each other especially in the T-loop, the proteins that they interact with to regulate ammonia switch-off are likely to be novel. In addition, there is no conserved site of uridylylation in either protein (26), suggesting that if modification of the NifI proteins is part of the nitrogen-sensing and -regulating pathway, the modification mechanism itself is also novel. Alternatively, the NifI proteins may not be modified at all. A modular evolution of the nitrogen-sensing regulatory cascade has been proposed (21, 28), in which the direct sensing of 2-ketoglutarate and/or glutamate by GlnB could have preceded the indirect sensing of glutamine via uridylylation of GlnB. It is possible that the NifI proteins of diazotrophic methanogens reflect such an evolutionary stage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Ludden for the NifH antibody and the R. rubrum extracts.

This work was supported by grant 96-35305-3891 from the National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and by grant GM-55255 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcondeguy, T., R. Jack, and M. Merrick. The PII signal transduction protiens: pivotal players in microbial nitrogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 1a.Argyle J L, Tumbula D L, Leigh J A. Neomycin resistance as a selectable marker in Methanococcus maripaludis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4233–4237. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4233-4237.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsene F, Kaminski P A, Elmerich C. Modulation of NifA activity by PII in Azospirillum brasilense: evidence for a regulatory role of the NifA N-terminal domain. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4830–4838. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4830-4838.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:301–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. Role of the GlnK signal transduction protein in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:431–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch W E, Fox G E, Magrum L J, Woese C R, Wolfe R S. Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:260–296. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.2.260-296.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belay N, Sparling R, Daniels L. Dinitrogen fixation by a thermophilic methanogenic bacterium. Nature. 1984;312:286–288. doi: 10.1038/312286a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blank C E, Kessler P S, Leigh J A. Genetics in methanogens: transposon insertion mutagenesis of a Methanococcus maripaludis nifH gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5773–5777. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5773-5777.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown M S, Segal A, Stadtman E R. Modulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation and deadenylylation is mediated by metabolic transformation of the P II -regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2949–2953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.12.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burris R H, Roberts G P. Biological nitrogen fixation. Annu Rev Nutr. 1993;13:317–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.13.070193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien Y T, Zinder S H. Cloning, functional organization, transcript studies, and phylogenetic analysis of the complete nitrogenase structural genes (nifHDK2) and associated genes in the archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri 227. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:143–148. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.143-148.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Kupiec R, Blank C, Leigh J A. Transcriptional regulation in Archaea: in vivo demonstration of a repressor binding site in a methanogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1316–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Zamaroczy M, Paquelin A, Peltre G, Forchhammer K, Elmerich C. Coexistence of two structurally similar but functionally different PII proteins in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4143–4149. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4143-4149.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N. The PII protein in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 is modified by serine phosphorylation and signals the cellular N-status. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:84–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.84-91.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gernhardt P, Possot O, Foglino M, Sibold L, Klein A. Construction of an integration vector for use in the archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae and expression of a eubacterial resistance gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00261731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunwald S K, Lies D P, Roberts G P, Ludden P W. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum strains overexpressing the regulatory enzymes dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase and dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:628–635. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.628-635.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He L, Soupene E, Ninfa A, Kustu S. Physiological role for the GlnK protein of enteric bacteria: relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6661–6667. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6661-6667.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh M H, Lam H M, van de Loo F J, Coruzzi G. A PII-like protein in Arabidopsis: putative role in nitrogen sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13965–13970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack R, De Zamaroczy M, Merrick M. The signal transduction protein GlnK is required for NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1156–1162. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1156-1162.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang P, Ninfa A J. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1906-1911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12782–12794. doi: 10.1021/bi980667m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. Reconstitution of the signal-transduction bicyclic cascade responsible for the regulation of Ntr gene transcription in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12795–12801. doi: 10.1021/bi9802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang P, Peliska J A, Ninfa A J. The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12802–12810. doi: 10.1021/bi980666u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang P, Zucker P, Atkinson M R, Kamberov E S, Tirasophon W, Chandran P, Schefke B R, Ninfa A J. Structure/function analysis of the PII signal transduction protein of Escherichia coli: genetic separation of interactions with protein receptors. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4342–4353. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4342-4353.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamberov E S, Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17797–17807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler P S, Blank C, Leigh J A. The nif gene operon of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1504–1511. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1504-1511.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler P S, Leigh J A. Genetics of nitrogen regulation in Methanococcus maripaludis. Genetics. 1999;152:1343–1351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leigh J A. Nitrogen fixation in methanogens—the archaeal perspective. In: Triplett E, editor. Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation: a model system for analysis of a biological process. Wymondham, United Kingdom: Horizon Scientific Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Magasanik B. Activation of the dephosphorylation of nitrogen regulator I-phosphate of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:926–931. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.926-931.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobo A L, Zinder S H. Diazotrophy and nitrogenase activity in the archaebacterium Methanosarcina barkeri 227. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1656–1661. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1656-1661.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobo A L, Zinder S H. Nitrogenase in the archaebacterium Methanosarcina barkeri 227. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6789–6796. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6789-6796.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludden P W. Reversible ADP-ribosylation as a mechanism of enzyme regulation in procaryotes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;138:123–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00928453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meletzus D, Rudnick P, Doetsch N, Green A, Kennedy C. Characterization of the glnK-amtB operon of Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3260–3264. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3260-3264.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merrick M J, Edwards R A. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:604–622. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.604-622.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray P A, Zinder S H. Nitrogen fixation by a methanogenic archaebacterium. Nature. 1984;312:284–286. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ninfa A J, Atkinson M R. PII signal transduction proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pope M R, Murrell S A, Ludden P W. Covalent modification of the iron protein of nitrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum by adenosine diphosphoribosylation of a specific arginine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3173–3177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian Y, Tabita F R. Expression of glnB and a glnB-like gene (glnK) in a ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4644–4649. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4644-4649.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve J N, et al. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Souillard N, Sibold L. Primary structure, functional organization and expression of nitrogenase structural genes of the thermophilic archaebacterium Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tumbula D L, Bowen T L, Whitman W B. Transformation of Methanococcus maripaludis and identification of a PstI-like restriction system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:309–314. [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Heeswijk W C, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Stegeman B, Kahn D, Westerhoff H V. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:133–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6281349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, Cheah E, Carr P D, van Heeswijk W C, Westerhoff H V, Vasudevan S G, Ollis D L. GlnK, a PII-homologue: structure reveals ATP binding site and indicates how the T-loops may be involved in molecular recognition. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:149–165. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity by anaerobiosis and ammonium in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6781–6788. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6781-6788.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Burris R H, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Presence of a second mechanism for the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in Azospirillum brasilense in response to ammonium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2948–2953. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2948-2953.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Pohlmann E L, Ludden P W, Roberts G P. Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the glnB, glnA, and nifA genes from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:983–992. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.983-992.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]