Abstract

The effect of TraY protein on TraI-catalyzed strand scission at the R1 transfer origin (oriT) in vivo was investigated. As expected, the cleavage reaction was not detected in Escherichia coli cells expressing tral and the integration host factor (IHF) in the absence of other transfer proteins. The TraM dependence of strand scission was found to be inversely correlated with the presence of TraY. Thus, the TraY and TraM proteins could each enhance cleaving activity at oriT in the absence of the other. In contrast, no detectable intracellular cleaving activity was exhibited by TraI in an IHF mutant strain despite the additional presence of both TraM and TraY. An essential role for IHF in this reaction in vivo is, therefore, implied. Mobilization experiments employing recombinant R1 oriT constructions and a heterologous conjugative helper plasmid were used to investigate the independent contributions of TraY and TraM to the R1 relaxosome during bacterial conjugation. In accordance with earlier observations, traY was dispensable for mobilization in the presence of traM, but mobilization did not occur in the absence of both traM and traY. Interestingly, although the cleavage assays demonstrate that TraM and TraY independently promote strand scission in vivo, TraM remained essential for mobilization of the R1 origin even in the presence of TraY. These findings suggest that, whereas TraY and TraM function may overlap to a certain extent in the R1 relaxosome, TraM additionally performs a second function that is essential for successful conjugative transmission of plasmid DNA.

The traM and traY genes of IncF conjugation systems are essential for transfer proficiency (19, 24, 25, 35). Numerous studies have established a role for traM and traY in regulation of transfer gene expression (6, 7, 34, 35, 41). Thus the transfer-deficient phenotype of traY and traM mutant derivatives is certain to reflect disruption of positive gene regulation as a minimum and may further reflect the loss of additional functions.

The TraM and TraY proteins of different IncF plasmids exhibit sequence-specific DNA binding activity at oriT (1, 8, 18, 21, 23, 30, 38, 39), and they have been implicated in the initiation stage of conjugative DNA transfer. During initiation of conjugative plasmid transfer an enzyme known as relaxase cleaves a defined strand of oriT DNA at a specific position (nic) in a transesterification reaction. Cleaving activity at oriT is exhibited as part of a nucleoprotein complex called the relaxosome. This complex includes the relaxase and auxiliary proteins, which can be host or plasmid encoded (12). These accessory factors impart specificity and stability to the complex and enhance the efficiency of the cleavage reaction. In many cases specific interactions between the auxiliary proteins and oriT DNA promote localized melting of the duplex and facilitate access of relaxase to its recognition site (31–33, 37, 40, 42, 46–49).

For the IncF system, extensive biochemical analysis has been dedicated to characterizing the relaxase-catalyzed cleavage reaction of oriT substrates in vitro. These studies have shown that the TraY proteins of IncF plasmids and the Escherichia coli histone-like integration host factor (IHF) promote the association of the TraI relaxase with oriT DNA (16) and enhance the cleaving activity of TraI in vitro (17, 28). An early study by Everett and Willetts using plasmid F additionally demonstrated the involvement of traI and traY in nic cleavage in vivo (10). We have been analyzing the composition and performance of the relaxosome of IncF plasmid R1 in vivo. A study to explore a possible role for oriT DNA binding protein TraM in the R1 relaxosome revealed an unexpected requirement for TraM protein to observe TraI-catalyzed strand scission in IHF-proficient E. coli in the absence of other transfer proteins (20). Thus, the R1 TraY protein was dispensable for cleavage on recombinant oriT substrates in vivo. Also contrary to expectations based on the previous biochemical and genetic analyses, TraY was dispensable for DNA processing occurring on recombinant mobilizable plasmids during bacterial conjugation (20). Notably, mobilization of the R1 oriT did not occur in the absence of both traM and traY.

The present study addresses the contribution of the TraY protein to the activity of the R1 relaxosome in vivo. Additionally, mobilization of R1 oriT by a heterologous transfer system was used to provide evidence for distinct functions for the proteins TraM and TraY during conjugative DNA strand transfer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The E. coli strains used in this study are K-12 derivatives. Cells were grown in 2× tryptone-yeast extract (TY) (26). Antibiotics were used to select for plasmid-carrying strains in the following final concentrations: for R1-16 and pOX38-Km, kanamycin at 40 μg ml−1; for pUC-, pMMB67-, and pMS119-based constructions, dihydroampicillin (epicillin) at 100 μg ml−1; for pBR322 derivatives, tetracycline at 15 μg ml−1; for pGZ119 constructions, chloramphenicol at 10 μg ml−1.

Enzymes and reagents.

Restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. DyNAzyme was obtained from Finnzymes (Espoo, Finland), and radiochemicals were from NEN.

Preparation of a traY expression plasmid for in vivo analyses.

The traY gene (positions 3683 to 3985; numbering according to reference 14) was amplified from E. coli MC1061 (R1-16) by PCR using primers UYE (5′-CCGGAATTCTGTGCAATCATG) and DYB (5′-GGGGATCCTCTGTTTAATATTG). These oligonucleotides contained nonhomologous EcoR1 and BamHI linkers to facilitate ligation of the PCR product to the pBluescript vector (Stratagene). DNA sequence analysis confirmed that the resulting recombinant DNA encoded the wild-type TraY protein. The traY gene fragment was excised using EcoR1 and BamHI and introduced to expression vector pGZ119EH (22) to create pGZYM1.

Preparation of the standard DNA template.

Oligonucleotide 8∗ (5′-AATTGGATGTTAGCCATCTGCCTGAGCT-3′) was complementary to primer 8 (20) and had additionally 4 nucleotides (nt) at the 5′ and 3′ ends compatible with the EcoRI/SacI-digested vector. Annealed oligonucleotides 8∗ and 8 were ligated to linear pBluescript DNA, and transformed XL1 (Stratagene) cells were selected with dihydroampicillin and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). A positive clone, confirmed by DNA sequencing, was purified, linearized, and reisolated for use in the cleavage assay.

Runoff DNA synthesis assay.

E. coli strains harboring plasmids were grown at 37°C to stationary phase and then diluted in fresh medium containing antibiotics and 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) as indicated in the legends to Fig. 1 and 2. Incubation at 37°C was continued with shaking for 2.5 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation after making adjustments for optical density. The medium was thoroughly removed. Cell pellets were kept at 0°C and used immediately. For the reaction mixture, bacteria were resuspended in 25 μl of ice-cold buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) at 25°C, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 100 ng of oligonucleotide, 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 μCi of [α-32P]dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), 1.0 ng of standard DNA template, and 2 U of DyNAzyme. Viable-cell counts were obtained at harvest. Primer 8 was used as described previously (20) except that the in vitro DNA synthesis was stopped by the addition of 8 μl of formamide loading dye. The reaction products were applied immediately to denaturing 7% polyacrylamide (19:1 polyacrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio) Tris-borate-EDTA gels and resolved with oriT- and primer 8-specific polynucleotide size markers as described previously (20). Following electrophoresis radioactive products were visualized by autoradiography.

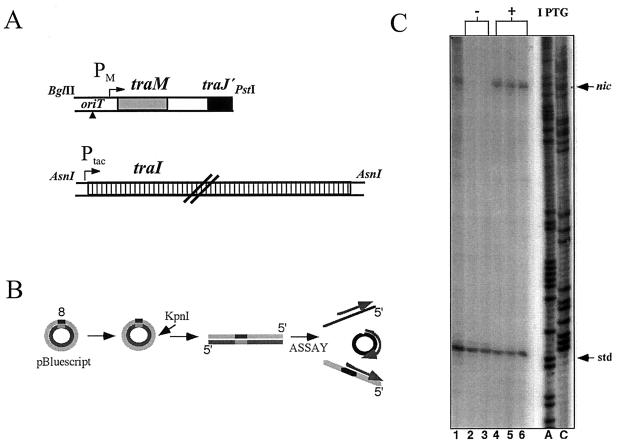

FIG. 1.

Runoff DNA synthesis measures intracellular TraI-catalyzed cleavage activity. (A) The tra genes on plasmids maintained in vivo are illustrated schematically. The 1.2-kb BglII-PstI fragment of R1 oriT-traM DNA contained in pBR322-based substrate plasmid pBR111 is shown (top). In the second plasmid, pHP2, a 6.1-kb AsnI fragment carrying the R1 traI gene is placed under Ptac control in expression vector pGZ119EH (bottom) (B) oriT primer 8 and its complementary sequence were annealed, and a single copy of the hybrid was introduced into an unrelated vector. A KpnI fragment from this clone that contained the primer sequence was isolated and added exogenously to the cells in the cleavage assay. Reaction mixtures thus contained three primed templates for in vitro DNA synthesis: cleaved (top) and uncleaved (middle) oriT plasmid DNA released from bacterial cells and the exogenously added linear template (bottom). (C) E. coli AG1 harboring pBR111 and pHP2 was harvested after overnight culture without IPTG (lane 1) or after subculture in fresh medium without (lanes 2 and 3) or with IPTG (lanes 4 to 6). In the cleavage assay equivalent cell masses (as indicated by optical densities at 600 nm) were present in all reaction mixtures in addition to 1 ng of purified KpnI fragment. Reaction products synthesized on the different templates can be readily distinguished according to size on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (nic and std). Dideoxynucleotide-terminated DNA sequence ladders (ddATP and ddCTP) generated on oriT DNA with primer 8 were used to determine polynucleotide chain length (lanes A and C).

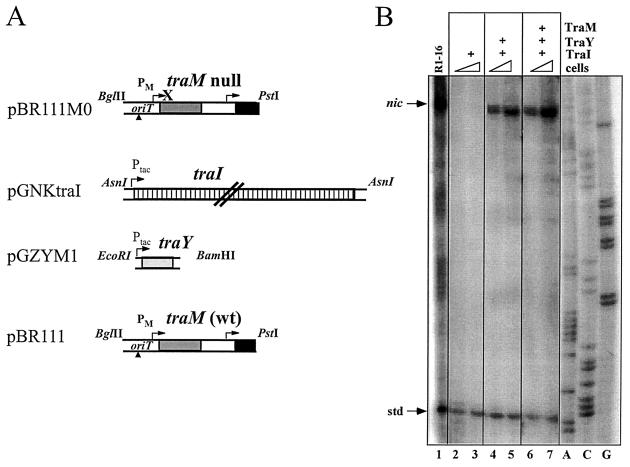

FIG. 2.

TraY stimulates TraI-catalyzed cleavage at oriT in vivo. Overnight cultures of E. coli AG1 strains carrying plasmids R1-16 (lane 1), pBR111M0, pGNKtraI, and pGZ119EH (lanes 2 and 3), pBR111M0, pGNKtraI, and pGZYM1 (lanes 4 and 5), or pBR111, pGNKtraI, and pGZYM1 (lanes 6 and 7) to provide the indicated combinations of proteins were subcultured in fresh medium with antibiotics and IPTG. The numbers of viable cells present in the reaction mixtures resolved in lanes 1 to 7 were 2.0 × 106, 1.4 × 106, 2.8 × 106, 0.34 × 106, 0.7 × 106, 0.8 × 106, and 1.7 × 106 CFU, respectively.

Mobilization assays.

E. coli J5 donor strains carrying a mobilizable test plasmid (20), transfer-proficient pOX38-Km (4), and pGZYM1 to provide R1 traY in trans were cultured overnight in 2× TY medium with antibiotic selection for all plasmids. Conjugation was carried out as described previously (20). Transconjugants carrying the conjugative plasmid were selected on MacConkey agar plates containing 40 μg of kanamycin/ml and 25 μg of streptomycin/ml. Transconjugants harboring the mobilized plasmid were selected using 100 μg of dihydroampicillin/ml and 25 μg of streptomycin/ml. Viable counts for donors were determined with chloramphenicol selection. The conjugation frequency was expressed as the number of Kmr Smr transconjugants per donor cell. The mobilization frequency was expressed as the number of Epr Smr transconjugants per donor cell.

RESULTS

The R1 TraY protein exhibits DNA binding activity.

The unexpected ability of the TraM protein to perform functions anticipated for the TraY protein in the R1 system raised the question of whether the TraY protein from plasmid R1 has DNA binding activity. To clarify this point, the TraY protein of R1 was purified as a fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase (GST) according to the procedure of Nelson and Matson (29). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed with the purified GST-TraY protein and various DNA fragments from the R1 oriT (data not shown). The region between positions 1865 and 2457 of the R1 sequence (14) was amplified by PCR and isolated or cleaved into multiple subfragments with either NdeI or DraI and then isolated for use as DNA ligands. EMSA with combinations of overlapping subfragments demonstrated a specific interaction between the TraY protein and oriT DNA between nt 2100 and 2158, in good agreement with the position of sbyA in the similarly structured oriT regions of F and R100 (18, 30).

Since TraY of R1 exhibited the expected DNA binding activity, we then asked whether TraY affected oriT cleavage activity in vivo. The in vitro procedure used earlier to monitor in vivo-catalyzed cleavage of recombinant R1 oriT plasmids (20) was improved for the present study (Fig. 1). Recombinant oriT plasmid pBR111, which expresses the adjacent traM gene from its own promoters, was maintained in IHF-proficient E. coli AG1 cells. The strain carried a second plasmid, pHP2 (45), which provides the R1 traI gene under Ptac control (Fig. 1A). To improve the level of nic-specific signal in the assay, the intracellular concentration of relaxase was raised by induction prior to cell harvest. Relaxase overexpression improved the efficiency of cleavage detected in vitro (Fig. 1C, nic) but did not alter the dependence of the reaction on auxiliary factors. Despite the higher abundance of relaxase, IHF alone was not sufficient to promote detectable cleavage (data not shown; Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 3). In the absence of TraY, the reaction in vivo required TraM, as previously established for uninduced levels of traI expression (20).

For the present work, quantitative comparison of cleavage activity in vivo was necessary; therefore, an internal standard to control for the DNA polymerase efficiency in vitro was prepared (Fig. 1B). The oligonucleotide primer used in the assay was cloned into an unrelated vector, and this recombinant plasmid was linearized and purified. The presence of a known amount of this DNA fragment, in addition to plasmid-containing bacterial cells, in the reaction mixture enables the yield of nic-specific product to be normalized (45). DNA synthesis on the linearized standard DNA template generated a specific product 72 nt in length (Fig. 1C, std) that is easily distinguishable from the longer 121-nt product synthesized on the R1 oriT plasmids (Fig. 1C, nic).

TraY promotes the cleaving activity of relaxase.

To evaluate the role of TraY in the relaxosome, pGZYM1 was constructed with the R1 traY gene under the control of the Ptac promoter in pGZ119EH (22). pGZYM1 or vector DNA was introduced into E. coli AG1 carrying additionally an oriT-traM cleavage substrate containing wild-type traM (pBR111) or null traM (pBR111M0) and pGNKtraI (20), where relaxase expression is also regulated by Ptac. The various strains, each carrying three plasmids to achieve the desired combination of proteins (Fig. 2), were grown in the presence of IPTG. Cells were harvested at equivalent optical densities, and increasing numbers were assayed. Reaction products terminated at nic were observed from the control AG1 (R1-16), which carries all tra genes (lane 1), and were observed when TraY (lanes 4 and 5) or TraY and TraM (lanes 6 and 7) were present in addition to relaxase but not when relaxase alone was expressed in the IHF proficient wild-type strain (lanes 2 and 3). Conversely, no intracellular cleavage was detected on pBR111 in the presence of relaxase, TraM, and TraY when the appropriate constructions were maintained in IHF-deficient strain K5302 himA ΔSmal::TnKmr (13) (data not shown). These results demonstrate that TraY is a component of the R1 relaxosome and that TraY and TraM can act independently of each other in a manner that is sufficient to stimulate TraI-catalyzed cleaving activity in vivo when E. coli IHF is also present.

Mobilization of R1 oriT DNA requires traM in the presence and absence of traY.

To investigate whether TraM and TraY impart equivalent functions to the relaxosome during conjugative transfer, the contribution of each to mobilization of the R1 oriT was assessed. Taking advantage of the plasmid specificity of TraY and TraM among IncF plasmids (10, 25, 43) we demonstrated earlier that mobilization of the R1 oriT by F-plasmid proteins did not occur in the absence of both TraM and TraY of R1 (20). Very efficient transfer was observed with TraM alone, however. If the essential role of traM during mobilization is solely to facilitate DNA processing at oriT, then the cleavage data imply that TraY should perform that function equally well. To test this, E. coli J5 carrying self-transmissible F derivative pOX38-Km and an R1 oriT test plasmid was transformed with traY expression construction pGZYM1 or a vector. In accordance with previous results (20), when the mobilization substrate carried the 1.2-kb BglII-PstI oriT fragment including the wild-type traM sequence, pMM-Mwt, mobilization of that plasmid occurred as efficiently as self-transfer by pOX38 (Table 1, row 1 [from the top]). When the oriT plasmid carried the traM null allele, pMM-M0, a 1,000-fold diminution in mobilization frequency compared to self-transmission by pOX38-Km was observed (Table 1, row 3). The additional presence of the R1 traY gene in the donor strain did not increase the efficiency of mobilization of the R1 oriT (Table 1, compare rows 3 and 4). Overexpression of traY through incubation of the donor strains in 0.1 mM IPTG for 1 h prior to the initiation of conjugation did not affect the frequency of mobilization (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to the requirements observed for oriT cleavage in vivo, TraM remained essential for mobilization of the R1 oriT even in the presence of TraY.

TABLE 1.

traM is required for mobilization of R1 oriT in the presence and absence of traYd

| Test plasmid | Expression plasmid | Frequency of:

|

Mobilization ratioc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfera | Mobilizationb | |||

| pMM-Mwt | pGZ119EH | 1.0 × 10−3 | 0.5 × 10−3 | 0.5 |

| pMM-Mwt | pGZYM1 | 1.0 × 10−3 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 1.4 |

| pMM-M0 | pGZ119EH | 1.1 × 10−3 | 4.3 × 10−6 | 3.9 × 10−3 |

| pMM-M0 | pGZYM1 | 1.8 × 10−3 | 4.4 × 10−6 | 2.4 × 10−3 |

Number of transconjugants divided by the number of donors.

Number of transconjugants containing the mobilized plasmid divided by the number of donors.

Frequency of mobilization divided by the transfer frequency.

The conjugative plasmid was pOX38-Km. Cotransfer frequencies of nonconjugative test plasmids carrying a wild-type or mutant allele of traMR1 in cis to oriTR1 were measured using an F helper plasmid in the presence or absence of traYR1 in trans. The values presented are the averages of five experiments.

DISCUSSION

The failure of traY to compensate for the absence of traM during transfer suggests two possible explanations. One is that that the requirements for relaxase to efficiently catalyze origin cleaving during bacterial conjugation are different from those in the absence of conjugation (the conditions applied in the cleavage assays shown in Fig. 1 and 2 and in reactions reconstituted in vitro with purified proteins). We find this hypothesis improbable, but formally it cannot be excluded.

A more likely explanation is that the cleaving reaction on the mobilization substrate was actually catalyzed by the complex of TraI, TraY, and IHF but that a successful transfer of this substrate was prevented at a later stage of the process. In that case, the crucial step would require the TraM protein, either as part of the relaxosome or independent of that complex. We attempted to test directly the first part of this hypothesis by assaying for cleavage of the mobilization plasmids catalyzed during conjugation. Cleavage could not be reproducibly observed on either pMM-Mwt or pMM-M0 (data not shown). A number of positive controls indicated that the assay may be impaired by the presence of both the highly homologous F and R1 origin regions in the reaction. Reiterated cycles of DNA synthesis in the cleavage assay result in an enhancement of the nic-specific product when the majority of molecules are cleaved in vivo. When this is not the case, it is expected that nic-specific products generated in early cycles would be lost in subsequent cycles if they annealed to uncleaved molecules of pOX38-Km or a mobilizable plasmid and were elongated beyond nic. The frequency of pOX38-Km transfer is usually reduced at least 10-fold when additional plasmids are carried by the host (Table 1). If a low frequency of intracellular cleavage accompanies the low transfer frequency, then we expect that strand scission at the nic sites of pOX38-Km and the mobilizable plasmids would not be reliably detected with this assay. Resolution of this question, therefore, will require a different approach.

The second aspect of this hypothesis, namely, that TraM additionally contributes an essential function to the transfer process at a step distinct from the initial strand cleavage reaction at oriT, is intriguing. This function for TraM would be required in addition to its essential role in gene regulation (reviewed in reference 44). The nature of this activity for TraM is unknown but may involve an interaction with TraG-like protein TraD (9). Current models propose that TraG-like proteins perform their essential role in conjugation by physically linking the DNA substrate destined for transfer to the transport machinery that delivers the DNA to the recipient cell. The interface between the protein and plasmid is apparently an interaction between TraG and one or more proteins of the relaxosome (2, 3, 5, 15, 27, 36). Specific contacts at this stage are thought to determine how efficiently a relaxosome gains access to the transport complex. The present report demonstrates that recombinant R1 oriT-traM null molecules are not transferred despite the presence of the cognate TraY protein. It is conceivable that these plasmids transfer poorly because TraM is not available to efficiently couple the relaxosome to TraD.

The contribution of TraY to the R1 relaxosome remains poorly defined. Biochemical analysis of the F-plasmid proteins (16, 28) and recent genetic data (11) suggest that one function of TraY is to impart stability to the complex. Further work is necessary for a detailed understanding of the activity and regulation of IncF relaxosomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was carried out in the framework of the MECBAD program and was supported by the Austrian FWF P11844-Med and P13277-GEN.

We thank P. M. Silverman for providing E. coli K5302 and K. Marians, E. Lanka, and A. Reisner for commenting on an early version of the manuscript. The technical assistance of H. Gerhold and H. J. Gruber is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abo T, Inamoto S, Ohtsubo E. Specific DNA binding of the TraM protein to the oriT region of plasmid R100. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6347–6354. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6347-6354.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabezón E, Lanka E, de la Cruz F. Requirements for mobilization of plasmids RSF1010 and ColE1 by the IncW plasmid R388: trwB and RP4 traG are interchangeable. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4455–4458. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4455-4458.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabezón E, Sastre J, de la Cruz F. Genetic evidence of a coupling role for the TraG protein family in bacterial conjugation. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:400–406. doi: 10.1007/s004380050432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler M, Galas D. Cointegrate formation mediated by Tn9. II. Activity of IS1 is modulated by external DNA sequences. J Mol Biol. 1983;170:61–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dash P K, Traxler B A, Panicker M M, Hackney D D, Minkley E G., Jr Biochemical characterization of Escherichia coli DNA helicase I. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1163–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempsey W B. Key regulatory aspects of transfer of F-related plasmids. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dempsey W B. Regulation of R100 conjugation requires traM in cis to traJ. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:987–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Laurenzio L, Frost L S, Paranchych W. The TraM protein of the conjugative plasmid F binds to the origin of transfer of the F and ColE1 plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2951–2959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disqué-Kochem C, Dreiseikelmann B. The cytoplasmic DNA-binding protein TraM binds to the inner membrane protein TraD in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6133–6137. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6133-6137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everett R, Willetts N. Characterisation of an in vivo system for nicking at the origin of conjugal DNA transfer of the sex factor F. J Mol Biol. 1980;136:129–150. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fekete R A, Frost L S. Mobilization of chimeric oriT plasmids by F and R100–1: role of relaxosome formation in defining plasmid specificity. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4022–4027. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.4022-4027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fürste J P, Ziegelin G, Pansegrau W, Lanka E. Conjugative transfer of promiscuous plasmid RP4: plasmid-specified functions essential for formation of relaxosomes. In: Kelly T, McMacken R, editors. Mechanisms of DNA replication and recombination. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1987. pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granston A E, Alessi D M, Eades L J, Friedman D I. A point mutation in the Nul gene of bacteriophage lambda facilitates phage growth in Escherichia coli with himA and gyrB mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:149–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00322458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graus H, Hödl A, Wallner P, Högenauer G. The sequence of the leading region of the resistance plasmid R1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1046. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton C M, Lee H, Li P L, Cook D M, Piper K R, von Bodman S B, Lanka E, Ream W, Farrand S K. TraG from RP4 and TraG and VirD4 from Ti plasmids confer relaxosome specificity to the conjugal transfer system of pTiC58. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1541–1548. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1541-1548.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard M T, Nelson W C, Matson S W. Stepwise assembly of a relaxosome at the F plasmid origin of transfer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28381–28386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inamoto S, Fukuda H, Abo T, Ohtsubo E. Site- and strand-specific nicking at oriT of plasmid R100 in a purified system: enhancement of the nicking activity of TraI (helicase I) with TraY and IHF. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1994;116:838–844. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inamoto S, Ohtsubo E. Specific binding of the TraY protein to oriT and the promoter region for the traY gene of plasmid R100. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6461–6466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kingsman A, Willetts N. The requirements for conjugal DNA synthesis in the donor strain during Flac transfer. J Mol Biol. 1978;122:287–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kupelwieser G, Schwab M, Högenauer G, Koraimann G, Zechner E L. Transfer protein TraM stimulates TraI-catalyzed cleavage of the transfer origin of plasmid R1 in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:81–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahue E E, Matson S W. Purified Escherichia coli F-factor TraY protein binds oriT. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1385–1391. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1385-1391.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lessl M, Balzer D, Lurz R, Waters V L, Guiney D G, Lanka E. Dissection of IncP conjugative plasmid transfer: definition of the transfer region Tra2 by mobilization of the Tra1 region in trans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2493–2500. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2493-2500.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo Y, Gao Q, Deonier R C. Mutational and physical analysis of F plasmid traY protein binding to oriT. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:459–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maneewannakul K, Kathir P, Endley S, Moore D, Manchak J, Frost L, Ippen Ihler K. Construction of derivatives of the F plasmid pOX-tra715: characterization of traY and traD mutants that can be complemented in trans. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntire S, Willetts N. Transfer-deficient cointegrates of Flac and lambda prophage. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;178:165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00267225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncalián G, Cabezón E, Alkorta I, Valle M, Moro F, Valpuesta J M, Goni F M, de la Cruz F. Characterization of ATP and DNA binding activities of TrwB, the coupling protein essential in plasmid R388 conjugation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36117–36124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson W C, Howard M T, Sherman J A, Matson S W. The traY gene product and integration host factor stimulate Escherichia coli DNA helicase I-catalyzed nicking at the F plasmid oriT. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28374–28380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson W C, Matson S W. The F plasmid traY gene product binds DNA as a monomer or a dimer: structural and functional implications. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1179–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson W C, Morton B S, Lahue E E, Matson S W. Characterization of the Escherichia coli F factor traY gene product and its binding sites. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2221–2228. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2221-2228.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pansegrau W, Balzer D, Kruft V, Lurz R, Lanka E. In vitro assembly of relaxosomes at the transfer origin of plasmid RP4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6555–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pansegrau W, Schröder W, Lanka E. Concerted action of three distinct domains in the DNA cleaving-joining reaction catalyzed by relaxase (TraI) of conjugative plasmid RP4. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2782–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pansegrau W, Schröder W, Lanka E. Relaxase (TraI) of IncPα plasmid RP4 catalyzes a site-specific cleaving-joining reaction of single-stranded DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2925–2929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penfold S S, Simon J, Frost L S. Regulation of the expression of the traM gene of the F sex factor of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:549–558. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5361059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pölzleitner E, Zechner E L, Renner W, Fratte R, Jauk B, Högenauer G, Koraimann G. TraM of plasmid R1 controls transfer gene expression as an integrated control element in a complex regulatory network. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:495–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4831853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sastre J I, Cabezón E, de la Cruz F. The carboxyl terminus of protein TraD adds specificity and efficiency to F-plasmid conjugative transfer. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6039–6042. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.6039-6042.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Otto S, Dobrinski B. In vitro cleavage of double- and single-stranded DNA by plasmid RSF1010-encoded mobilization proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:41–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwab M, Gruber H, Högenauer G. The TraM protein of plasmid R1 is a DNA-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwab M, Reisenzein H, Högenauer G. TraM of plasmid R1 regulates its own expression. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:795–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman J A, Matson S W. Escherichia coli DNA helicase I catalyzes a sequence-specific cleavage/ligation reaction at the F plasmid origin of transfer. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26220–26226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman P M, Sholl A. Effect of traY amber mutations on F-plasmid traY promoter activity in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5787–5789. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5787-5789.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waters V L, Hirata K H, Pansegrau W, Lanka E, Guiney D G. Sequence identity in the nick regions of IncP plasmid transfer origins and T-DNA borders of Agrobacterium Ti plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1456–1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willetts N. Sites and systems for conjugal DNA transfer in bacteria. In: Levy S B, Clowes R C, Koenig E L, editors. Molecular biology, pathogenicity, and ecology of bacterial plasmids. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1981. pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zechner E L, de la Cruz F, Eisenbrandt R, Grahn A M, Koraimann G, Lanka E, Muth G, Pansegrau W, Thomas C M, Wilkins B M, Zatyka M. Conjugative-DNA transfer processes. In: Thomas C M, editor. The horizontal gene pool: bacterial plasmids and gene spread. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 87–174. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zechner E L, Prüger H, Grohmann E, Espinosa M, Högenauer G. Specific cleavage of chromosomal and plasmid DNA strands in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria can be detected with nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7435–7440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang S, Meyer R J. Localized denaturation of oriT DNA within relaxosomes of the broad-host-range plasmid R1162. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:727–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17040727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang S, Meyer R J. The relaxosome protein MobC promotes conjugal plasmid mobilization by extending DNA strand separation to the nick site at the origin of transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:509–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4861849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziegelin G, Fürste J P, Lanka E. TraJ protein of plasmid RP4 binds to a 19-base pair invert sequence repetition within the transfer origin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11989–11994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziegelin G, Pansegrau W, Lurz R, Lanka E. TraK protein of conjugative plasmid RP4 forms a specialized nucleoprotein complex with the transfer origin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17279–17286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]