Background

Although vaccines have markedly improved the health of the pediatric population,1 primary care clinicians now encounter many families who refuse or delay vaccines or request alternative schedules.2,3,4 Vaccine refusal has contributed to recent outbreaks of measles5,6 and low rates of influenza vaccination,7,8 and threatens gains made over the past decades.9,10

Vaccine refusal or delay can result from a spectrum of parental and patient beliefs and perceptions widely referred to as “vaccine hesitancy,”2,11 which the World Health Organization now labels one of the top ten health threats.12 Some parents have concerns and questions about vaccines but still choose to have their children vaccinated. Others have more serious concerns and delay vaccines or request alternative schedules.2 Still others refuse vaccines. Better understanding of vaccine hesitancy and its relation to receipt of vaccinations could help shape interventions.13,14

Experts have defined vaccine hesitancy using somewhat varied constructs.2 Some definitions of hesitancy have focused on negative consumer beliefs about the effectiveness, safety, and necessity of a vaccine.15,16 A World Health Organization committee defined vaccine hesitancy as a behavior that is influenced by vaccine confidence, complacency about the need for a vaccine, and convenience (which includes access factors or practical barriers).2,17,18 Others do not feel that convenience should be part of the construct of hesitancy. While some experts view hesitancy as a continuum of beliefs and attitudes that influence but do not perfectly correlate with acceptance, refusal or delay of vaccines,19–21 others use vaccination behaviors themselves to define or confirm vaccine hesitancy.15,22 A recent review proposes that hesitancy is a motivation, influenced by risk appraisal plus vaccine confidence, all of which lead to vaccine acceptance, refusal, or delay.13 For the current study, we define vaccine hesitancy as a motivation affected by perceptions, but distinct from practical barriers to receipt of vaccines; both hesitancy and practical barriers can influence vaccine receipt, refusal or delay.

Vaccine hesitancy and practical barriers are highly relevant to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. While many clinicians encounter parents who refuse or delay the HPV vaccine,14 the degree to which vaccine hesitancy and practical barriers are related to suboptimal HPV vaccine coverage rates is unknown on a national level. In 2018, only 54% of US girls and 49% of US boys 13–17 years of age had completed the HPV vaccine series23 and, while coverage rates have risen gradually,24 they still lag far below national goals.25 The 2013 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) asked parents whose adolescents did not receive the HPV vaccine the reason for not being vaccinated. Common reasons included: the vaccine was not recommended by providers, concerns about vaccine safety, perception that the vaccine is not needed at a certain age or should be delayed, and lack of knowledge.26 Similar findings were noted in subsequent NIS-Teen surveys.27 However, these surveys did not measure the prevalence of HPV vaccine hesitancy as many hesitant parents may still accept the vaccine (and therefore were not asked the NIS-Teen hesitancy questions). A 2014 online survey about HPV vaccination noted an association between strong provider recommendation and HPV vaccine acceptance,28 but did not describe the prevalence of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Studies in Canada29 and the United Kingdom30 have documented high rates of HPV vaccine hesitancy at national levels, but current national data about vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. is lacking.

The objectives of this study were to assess, among parents of adolescents 11–17 years of age across the US: (1) the prevalence of HPV vaccine hesitancy; (2) types of concerns about the HPV vaccine; (3) the relationship between sociodemographic factors and HPV vaccine hesitancy; (4) practical barriers to receipt of HPV vaccine; and (5) the degree to which HPV vaccine hesitancy and practical barriers are associated with parent-reported receipt of HPV vaccine or refusal of the vaccine. To address these objectives, we performed an online survey of a nationally representative sample of parents of adolescents 11–17 years of age.

Methods

General Methods

In April 2019, we surveyed families with adolescents 11 to 17 years of age, using an online panel of families, to obtain information about HPV vaccine hesitancy, barriers to HPV vaccination, and parent-reported receipt of HPV vaccine or refusal of the vaccine.

Survey Panel

Study procedures and methods were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

We used the Ipsos panel as the sampling frame (https://www.ipsos.com/en-au/ipsosonline-access-panels). This panel of 55,000 individuals (Knowledge Panel®) is constructed from a random sampling of addresses to create an Internet-based survey panel representative of the non-institutionalized US population. Ipsos utilizes address-based sampling methods via the US Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File. This strategy results in higher coverage than randomdigit dialing methods and is thought to better reflect US households, many of which have only cellular phones and not landlines. Ipsos recruits panel participants via a series of mailings, telephone calls, and a designated website. Ipsos also uses a patented method to weight the sample based upon geodemographic benchmarks from the US Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS). These include: gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, census region, household income, home ownership, and geographic region. Household members are enumerated; this allowed us to identify families with adolescents 11–17 years of age. Panelists are offered a small incentive to participate in surveys (e.g., sweepstakes, small cash rewards). Multiple recent studies31–35 have utilized the KnowledgePanel.®

Selection of Sample

Inclusion criteria from the Ipsos panel were: (1) parent, guardian or foster parent of an adolescent age 11 – 17 years, (2) living with the adolescent, and (3) able to complete the online survey in English or Spanish. Questions focused on one adolescent randomly selected per family. Eligible families received an email and a link to the survey; up to two email reminders were sent to non-responders. An initial sample was selected to reach a desired sample size of n=2,000 survey completions. This sample size provides a margin of error for estimated rates of ± 2.2 percentage points, conservatively assuming a population rate of 50% and a 95% confidence level.

Questionnaire Development

The survey included questions to assess hesitancy for HPV vaccine, practical barriers to the receipt of HPV vaccine, parent-reported receipt of HPV vaccine, and sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents and families. Ipsos translated the survey into Spanish. Ipsos pretested all questions on 32 randomly selected individuals for content and ease of completion.

HPV Vaccine Hesitancy-

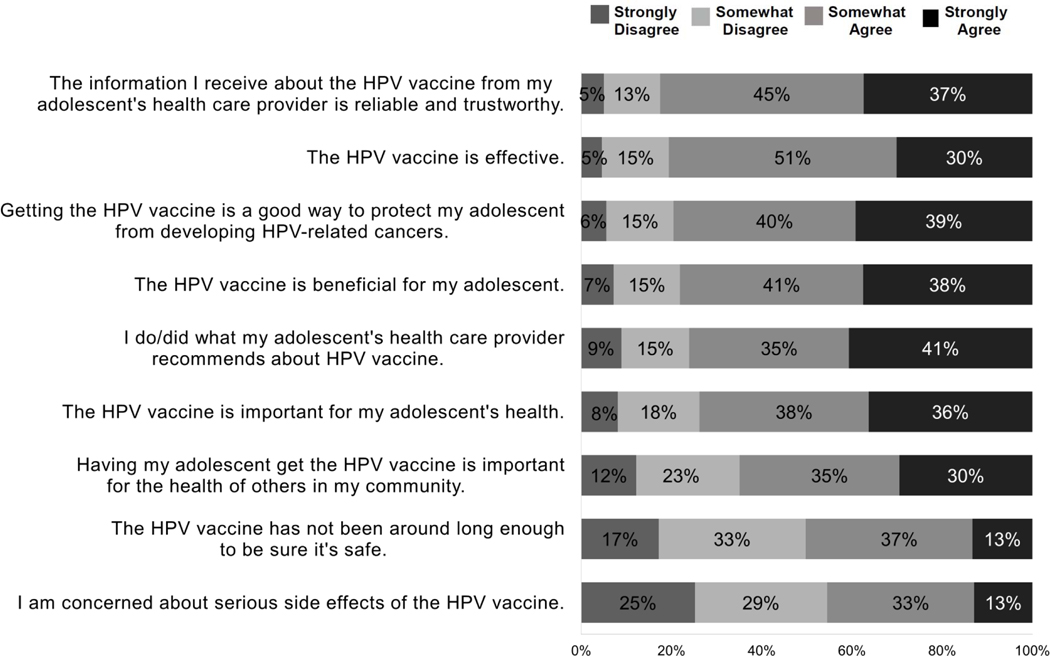

We adapted the 9-item Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) to assess HPV vaccine hesitancy. The VHS was originally developed in 2015 by the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on immunizations17 to evaluate childhood vaccine hesitancy.36 It was based upon global data on vaccine hesitancy and a literature review of survey tools. It incorporated components of a survey tool originally used among higher-income US populations.15 The VHS does not include questions on practical barriers to childhood vaccination but instead focuses upon beliefs and perceptions. The VHS originally had multiple sections, but was psychometrically validated with 10 items using Likert scales and a revised version included the domains of vaccine confidence and risks of the vaccine.37 Notably, the revised VHS did not include specific questions about perceived risks of vaccine-preventable diseases; however several VHS questions about the importance of the vaccines require the responder to incorporate some aspects of disease risk appraisal (see Figure 1; e.g., “Getting the HPV vaccine is a good way to protect my adolescent from developing HPV-related cancers”).

Figure 1:

Parental perceptions about HPV vaccination: Items from the 9–item modified VHS scale adapted for HPV vaccine

Modified VHS surveys have been used to evaluate HPV vaccine hesitancy in Canada29 and the United Kingdom,30 and a Spanish-translated VHS survey has been used to assess levels of childhood vaccine hesitancy in Guatemala.38 The VHS has been closely correlated with other scales of HPV vaccine decisions including the Vaccine Conspiracy Belief Scale (VCBS) and the HPV Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (HABS).37,39

We used 9 of the 10 items (Figure 1) in the VHS because prior work found one item to be redundant37,39 and we felt this item (“All childhood vaccines offered by the government program in my community are beneficial”) was not transferrable to the U.S. We used a 4-point, rather than the original 5-point Likert (no neutral responses) because of evidence that omitting the neutral option decreases the potential for socially desirable responding40 but scored the survey (see Definition of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy below) in a manner comparable to prior published papers using the VHS.

Barriers to HPV Vaccination:

We adopted questions from other sources26,41,42 and created six questions about practical barriers to HPV vaccination. These included questions about lack of convenience of getting the HPV vaccine, the adolescent’s provider not recommending HPV vaccine, difficulty paying for the vaccine, not having a place to get the vaccine, not having a regular source of care, and lack of HPV vaccine availability at the provider’s office.

Demographics and Patient Characteristics (Table 1):

Table 1:

Demographics of respondents (n=2,020 parents responding about their adolescent)

| Percent | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Adolescents | |

| Age | |

| 11–12 years | 21.3% |

| 13–14 years | 26.2 % |

| 15–17 years | 52.6% |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Female | 49.2% |

| Male | 51.8% |

|

| |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | 57.1% |

| Black non-Hispanic | 10.8% |

| Hispanic | 23.1% |

| Other, multi-racial, non-Hispanic | 9.1% |

|

| |

| Adolescent Overall Health | |

| Excellent | 46.6% |

| Very good | 37.6% |

| Good | 13.5% |

| Fair | 2.0% |

| Poor | 0.4% |

|

| |

| Parent/Guardian/Foster Parent | |

|

| |

| Respondent Education | |

| High school or less | 35.2% |

| Some college | 27.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 37.5% |

|

| |

| Household Income | |

| <Federal Poverty Level (FPL) | 12.3% |

| 100–400% of FPL | 47.6% |

| >400% of FPL | 40.1% |

|

| |

| Country Region | |

| Northeast | 16.4% |

| Midwest | 21.2% |

| South | 36.5% |

| West | 25.9% |

|

| |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area Status | |

| Non-metro | 12.9% |

| Metro | 87.1% |

Ipsos has data on standard demographic characteristics of all respondents and their family members including characteristics of adolescents (overall health, age, race/ethnicity) and their families (respondent education, household income, region, and Metropolitan Statistical Area or MSA status).

Receipt of HPV Vaccines:

We asked whether the adolescent had received any HPV vaccinations, had completed the HPV vaccine series, and whether parents had ever refused an HPV vaccine because of concerns about the vaccine. These questions were modified from questions used to validate the original VHS.36

Statistical Analysis

Dependent and Independent Measures:

Dependent measures included: (a) scores on the VHS to define hesitancy, (b) responses to questions on practical barriers to HPV vaccination, (c) parent-reported receipt of HPV vaccine by the index adolescent, and (d) response to the question about whether parents had ever refused an HPV vaccine if offered. For all dependent measures, the independent measures included adolescent and family demographic characteristics. Additionally, in predicting receipt of HPV vaccines and whether concerns about HPV vaccines ever kept the adolescent from receiving the vaccine, the independent measures also included scores on the questions derived from the VHS as well as those about practical barriers.

Definition of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy:

We estimated HPV vaccine hesitancy from the VHS-derived questions as follows: First, we reverse-coded negatively worded items. Then, since we had used a 4-point Likert scale (without a neutral response), we mapped responses for each item on a 5-point scale (strongly agree = 1, agree = 2, disagree = 4, strongly disagree = 5), such that higher values always indicated greater hesitancy. We scored responses in this manner in order to be able to map our results to previous literature using a 5-point response scale.29,30,37,38 We then calculated the average score over the 9 items that were included in our HPV-adapted VHS instrument. We defined “HPV vaccine hesitancy” as a VHS score >3. Since there is no gold-standard definition of vaccine hesitancy and prior studies using the VHS have tended not to categorize or define “hesitancy”, we decided on a cut-off of 3 because it is the midpoint of the VHS. This aligns with the 50% cut-off on another scale, Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines survey (PAC-V), widely used to assess childhood vaccine hesitancy.15,43,44 Parents who scored higher than the cut-off had responses to the VHS items that, on average, indicated concerns about the vaccine, so we labelled them as “HPV vaccine hesitant.”

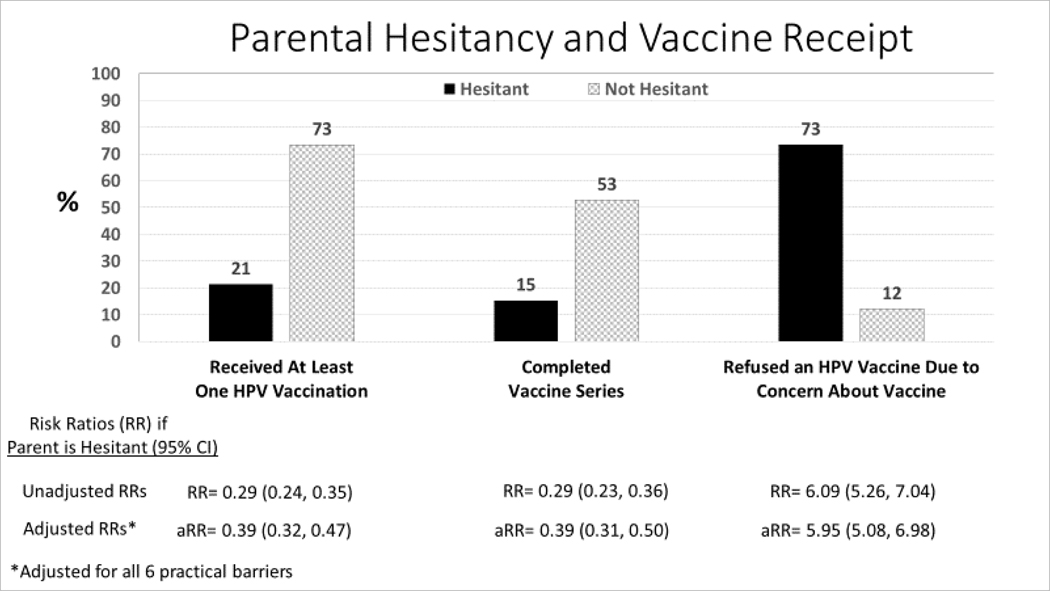

Hesitancy and Vaccine Refusal (Figure 2):

Figure 2:

Association between parental hesitancy about HPV vaccine and receipt of HPV vaccines or refusal of an HPV vaccine (unadjusted analysis).

We compared subjects with hesitant versus non-hesitant scores with respect to refusal of HPV vaccine due to concerns about the vaccine, and we estimated unadjusted risk ratios for hesitant versus non-hesitant parents. We then conducted multivariable log-binomial regression models with the dependent variable being HPV vaccination hesitancy (modified VHS score>3). We selected independent variables based on the prior literature and potential sociodemographic factors that we believed a priori to potentially be related to HPV vaccine hesitancy. This included adolescent factors (general health, age, and gender) and family factors (number of children in the household, and the respondent’s education, race/ethnicity, marital status, household income, region of residence, and MSA status).

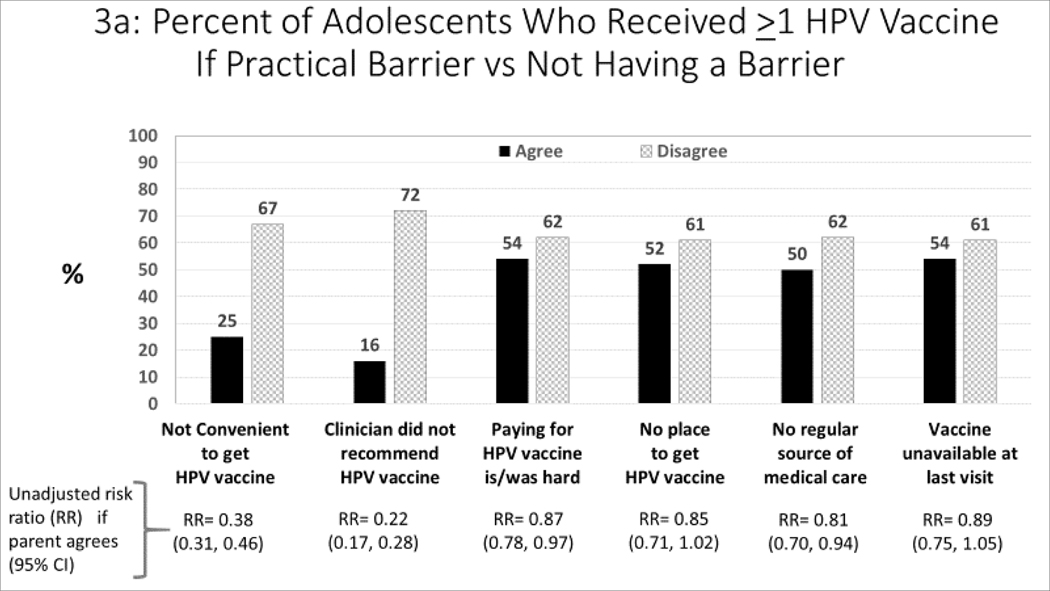

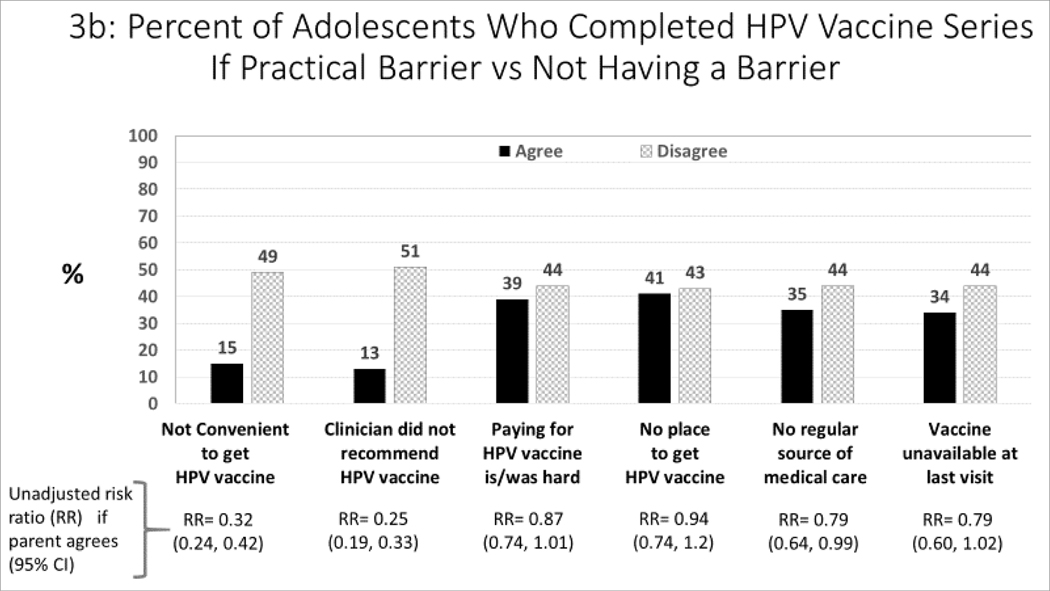

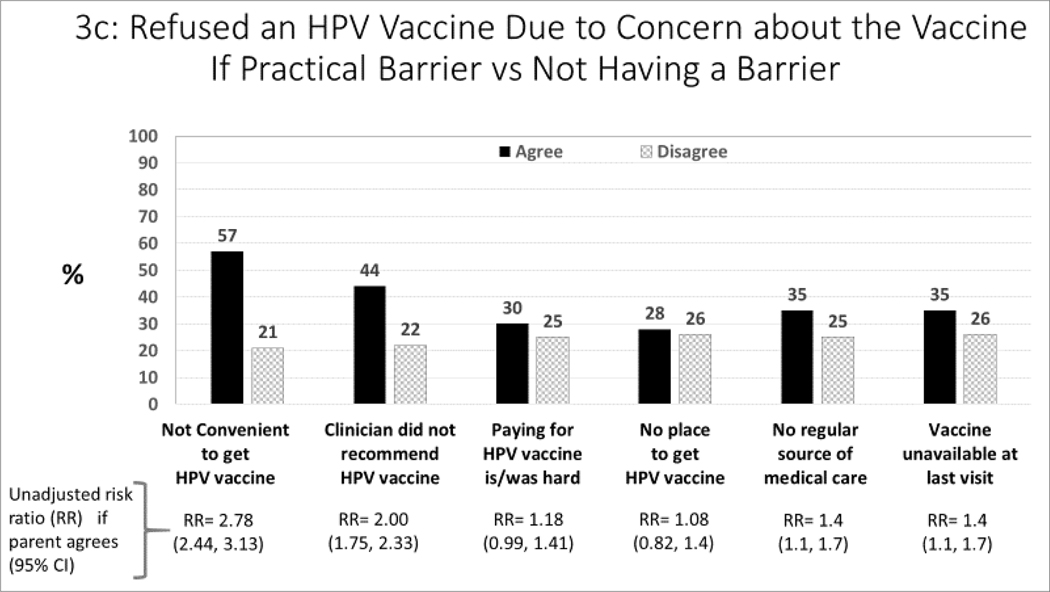

Practical Barriers and Receipt of HPV Vaccinations (Figure 3a–c):

Figure 3:

Association between barriers to HPV vaccination, and parent-report about receipt of HPV vaccines (unadjusted analysis)

For each barrier, we compared subjects who agreed versus disagreed with each barrier statement with respect to parent-report about both receipt of >1 HPV vaccine (Figure 3a) and HPV vaccine series completion (Figure 3b). We also compared each barrier statement with respect to parentalreport about refusal of HPV vaccine (if offered) due to concerns about the vaccine. We estimated unadjusted risk ratios with and without each barrier.

Barriers, Hesitancy, and Receipt of HPV Vaccinations (Table 3):

Table 3:

Practical barriers to receiving the HPV vaccine, and their relationship to HPV vaccine hesitancy (n=2020)

| Practical Barriers to HPV Vaccination | Percent Who Are Hesitant About HPV Vaccine (RR, 95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| It was/would be convenient to get the HPV vaccine for my adolescent. | ||

| • Disagree (i.e., a barrier) | 16% | 61% |

| • Agree | 84% | 16% |

| RR= 3.70 (3.23, 4.35) | ||

|

| ||

| My adolescent’s provider recommended that my adolescent get the HPV vaccine. | ||

| • Disagree (i.e., a barrier) | 21% | 50% |

| • Agree | 79% | 16% |

| RR=3.13 (2.63, 3.57) | ||

|

| ||

| Paying for the HPV vaccine was/would be hard for me. | ||

| • Agree (i.e., a barrier) | 18% | 31% |

| • Disagree | 82% | 22% |

| RR=1.44 (1.21, 1.72) | ||

|

| ||

| I did not/would not have a way to get to a place where my adolescent could get the HPV vaccine. | ||

| • Agree (i.e., a barrier) | 7% | 26% |

| • Disagree | 93% | 23% |

| RR=1.15 (0.86, 1.54) | ||

|

| ||

| I do not have a regular source of medical care for my adolescent. | ||

| • Agree (i.e., a barrier) | 11% | 30% |

| • Disagree | 89% | 23% |

| RR=1.30 (1.04, 1.63) | ||

|

| ||

| My adolescent’s provider did not have the vaccine available during their most recent visit. | ||

| • Agree (i.e., a barrier) | 6% | 27% |

| • Disagree | 94% | 23% |

| RR=1.18 (0.88, 1.59) | ||

Unadjusted risk ratios for association with HPV vaccine hesitancy, among parents who agree with the statement about a barrier to receiving HPV vaccine.

We calculated the relationship between practical barriers with respect to parent-report about receipt of HPV vaccine and HPV vaccine hesitancy to assess the degree of overlap. Finally, we estimated, using unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios, the association between barriers, hesitancy and receipt of HPV vaccinations or refusal of HPV vaccines.

All analyses employed sampling weights provided by Ipsos, and were performed using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Altogether 4,185 online surveys were sent, 2,177 were completed (52%), and 2,020 respondents (93% of completed surveys) qualified; 157 respondents did not live with the adolescent. Adolescents were distributed relatively evenly by age group and gender (Table 1); 11% were black and 23% Hispanic, and parents of 84% regarded their overall health as excellent or very good. Parents were distributed widely across educational and income levels and geographic regions.

Hesitancy for HPV Vaccine (from the VHS)

Of the 2,020 respondents, 23.4% had a VHS score >3, signifying HPV vaccine hesitancy according to our definition. Overall, for the 9-item scale the median score was 2.2 and the mean score was 2.3. Among all respondents, 41.0% had a mean score less than 2, 35.6% had a mean score between 2 and 3, and 23.4% had a mean score of more than 3 indicating hesitancy for HPV vaccine.

Beliefs and Perceptions Contributing to HPV Vaccine Hesitancy (from the VHS) (Figure 1)

Combining responses of ‘somewhat agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, 46% of parents agreed they were concerned about serious side effects of the HPV vaccine and 50% agreed that the vaccine has not been around long enough to be sure it is safe. At the same time, 22% disagreed that the vaccine was beneficial to their adolescent, 21% disagreed that the vaccine was a good way to protect against HPV-related cancers, and 20% disagreed that the HPV vaccine was effective. Finally, 24% disagreed that they followed their adolescents’ physician’s recommendations regarding HPV vaccine and 18% disagreed that the information about HPV vaccine from their adolescent’s healthcare provider was trustworthy.

Among hesitant patients (VHS score >3), hesitancy was most consistently expressed for concern about the importance of the vaccine for the child’s health (90% somewhat or strongly disagreed) or the health of the community (93%), and concern about the benefits for their adolescent (85%).

Demographic Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Hesitancy (Table 2, Unadjusted Analysis)

Table 2:

Factors associated with HPV vaccine hesitancy-- Score >3 on VHS (n=2020)

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted RR* (95% CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents | ||||

| Age (Ref = 15 – 17 years) | ||||

| 11 – 12 years | 0.86 (0.69, 1.07) | 0.179 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) | 0.145 |

| 13 – 14 years | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) | 0.188 | 1.10 (0.92, 1.31) | 0.308 |

| Gender (Ref = Male) | ||||

| Female | 1.00 (0.85, 1.17) | 0.958 | 1.03 (0.88, 1.20) | 0.735 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref = White non-Hispanic) | ||||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 0.90 (0.70, 1.17) | 0.431 | 0.82 (0.63, 1.07) | 0.144 |

| Hispanic | 0.75 (0.61, 0.92) | 0.006 | 0.67 (0.53, 0.84) | <0.001 |

| Other, Multi-racial, Non-Hispanic | 0.53 (0.36, 0.77) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.40, 0.85) | 0.005 |

| Adolescent Overall Health (Ref = Excellent) | ||||

| Very Good | 1.05 (0.88, 1.25) | 0.615 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21) | 0.836 |

| Good | 1.18 (0.94, 1.49) | 0.155 | 1.14 (0.90, 1.43) | 0.277 |

| Fair | 1.05 (0.59, 1.87) | 0.860 | 1.12 (0.63, 1.98) | 0.701 |

| Poor | 1.31 (0.44, 3.90) | 0.627 | 1.50 (0.50, 4.52) | 0.469 |

|

| ||||

| Parent/Guardian/Foster Parent | ||||

| Respondent Education (Ref = ≤ High School) | ||||

| Some College | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) | 0.763 | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 0.890 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.82 (0.68, 0.99) | 0.037 | 0.97 (0.77, 1.22) | 0.820 |

| Household Income (Ref = <FPL) | ||||

| 100–400% of FPL | 1.08 (0.85, 1.36) | 0.547 | 1.01 (0.79, 1.30) | 0.935 |

| >400% of FPL | 0.71 (0.55, 0.92) | 0.010 | 0.65 (0.48, 0.88) | 0.005 |

| Country Region (Ref = Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | 1.14 (0.88, 1.47) | 0.321 | 1.01 (0.78, 1.31) | 0.916 |

| South | 1.15 (0.91, 1.45) | 0.252 | 1.11 (0.88, 1.41) | 0.387 |

| West | 0.86 (0.66, 1.12) | 0.266 | 0.87 (0.67, 1.14) | 0.328 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area (Ref = Non-Metro) | ||||

| Metro | 0.76 (0.62, 0.94) | 0.011 | 0.90 (0.73, 1.11) | 0.327 |

Adjusted for all the other variables in the table

Abbreviations: Ref = reference group, FPL = Federal Poverty Level

On unadjusted analysis, Hispanic ethnicity (and multi-racial background), Bachelor’s degree or higher education, income >400% of federal poverty level (FPL), and residence in a metropolitan area were each associated with lower likelihood of vaccine hesitancy. On adjusted analysis, Hispanic ethnicity, other, multi-racial, non-Hispanic background, and income >400% of FPL were independently associated with lower likelihood of hesitancy.

Receipt of HPV Vaccine

Among 11–17 year olds, 61% of adolescents (62% of girls, 59% of boys) had received ≥1 HPV vaccine, and 43% (45% of girls, 42% of boys) had completed the HPV vaccine series. Among 13–17 year olds, 63% had received ≥1 HPV vaccine, and 47% had completed the series.

HPV Vaccine Hesitancy (from the VHS) and Vaccine Receipt or Refusal (Figure 2, Unadjusted Analysis)

Among HPV vaccine hesitant parents, 21% of adolescents received ≥1 HPV vaccine, 15% completed the series, and 73% had refused an HPV vaccine because of their concerns about the vaccine. Adolescents of hesitant parents were far less likely than those of non-hesitant parents to have received ≥1 HPV vaccine (unadjusted RR=0.29, 95% CI 0.24, 0.35) or to have completed their vaccine series (unadjusted RR=0.29, 95% CI 0.23, 0.36). Hesitant parents were far more likely to have refused an HPV vaccine because of their concern about the vaccine (unadjusted RR=6.09, 95% CI 5.26, 7.04).

Barriers to HPV Vaccination (Table 3 and Figures 3a–c, Unadjusted Analysis)

More than three-quarters of parents stated that receiving the vaccine was convenient and that their pediatrician had recommended the HPV vaccine. Although 18% of parents reported that vaccine costs were or would be a concern, only a small percent reported other practical barriers (e.g., no source of vaccination or medical care, or unavailability of the HPV vaccine at the adolescent’s last visit). Table 3 also demonstrates the degree of overlap between barriers and HPV vaccine hesitancy. Parents whose adolescent provider recommended the vaccine were far less likely to be hesitant; however, those for whom vaccination was inconvenient, had financial concerns, or did not have a regular source of care were more likely to also report being hesitant about HPV vaccine.

Figures 3a–c show the relationship between barriers and the three measures of HPV vaccination -- receipt of ≥1 vaccination, series completion, and refusal of HPV vaccine due to concern about the vaccine. The major barriers to both receipt of ≥1 vaccination (Figure 3a) and series completion (Figure 3b) were: not convenient to get the vaccine and the adolescent’s clinician didn’t recommend the vaccine. The major barriers related to refusal of HPV vaccine (Figure 3c) were: not being convenient, clinician did not recommend the vaccine, no regular source of medical care, and vaccine not being available at the last visit.

Contribution of Practical Barriers to Vaccine Receipt (Table 4, Adjusting for HPV Vaccine Hesitancy)

Table 4:

Added contribution of barriers after adjusting for HPV vaccine hesitancy (n=2020)

| Practical Barriers | Received ≥1 HPV Vaccine (aRR, 95% CI) | Completed HPV Vaccine Series (aRR, 95% CI) | Refused HPV Vaccine Because of Concerns About the Vaccine (aRR, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was/would be convenient to get the HPV vaccine for my adolescent [Disagree]. | 0.58 (0.48, 0.71) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.64) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.28) |

| My adolescent’s provider recommended that my adolescent get the HPV vaccine [Disagree]. | 0.29 (0.23, 0.37) | 0.33 (0.25, 0.43) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) |

| Paying for the HPV vaccine was/would be hard for me. [Agree] | 0.91 (0.83, 1.00) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.05) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.03) |

| I did not/would not have a way to get to a place where my adolescent could get the HPV vaccine [Agree]. | 0.89 (0.75, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.78, 1.21) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.06) |

| I do not have a regular source of medical care for my adolescent [Agree]. | 0.83 (0.73, 0.95) | 0.81 (0.66, 0.98) | 1.00 (0.87, 1.15) |

| My adolescent’s provider did not have the vaccine available during their most recent visit [Agree]. | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.56, 0.94) | 1.12 (0.96, 1.30) |

aRRs adjusted for only HPV vaccine hesitancy

As Table 4 shows, while many practical barriers were independently associated with receipt of ≥1 vaccination or series completion, only one barrier (not being convenient to get a vaccine) was slightly associated with HPV vaccine refusal (aRR=1.16). Thus, barriers appear to be inversely related to vaccine receipt, but not to vaccine refusal, which appears to be driven largely by hesitancy.

HPV Vaccine Hesitancy and Vaccine Receipt or Refusal (Figure 2, Adjusted Analysis)

Figure 2 also depicts the association between parental hesitancy with receipt or refusal of HPV vaccine, after adjusting for barriers. As seen by comparing the unadjusted risk ratios (RRs) with the adjusted risk ratios, adjustment for all 6 practical barriers did not substantively affect the RRs for any measure, suggesting that vaccine hesitancy, independent of practical barriers, was associated with not having initiated or completed HPV vaccinations with refusal of HPV vaccine when offered. Thus, parental hesitancy, and not practical barriers, were the primary driver of vaccine refusal.

Discussion

This study found that 23% of US parents of adolescents 11–17 years of age are hesitant about the HPV vaccine. To our knowledge, our study is unique in directly measuring parental hesitancy for HPV vaccine. Other national studies have assessed specific reasons for not receiving HPV vaccine26,27 but some hesitant parents still accept HPV vaccine; thus, our study adds to the literature by describing the population of HPV vaccine-hesitant parents. Our findings from questions derived from the VHS closely mirror those in Canada.29 Many US parents do not believe the HPV vaccine is beneficial for their adolescent, protects against HPV-related cancers, or is effective. Many are concerned about HPV vaccine safety and about the novelty of the vaccine, and a high proportion of parents expressed that they did not trust the information about HPV vaccine that they received from their adolescent’s healthcare provider. Notably, HPV vaccine hesitancy is strongly related to adolescents not having received the vaccine and to parental report that they refused the vaccine specifically because of their concerns about HPV vaccine. Hesitancy is quite prevalent in this national sample of parents and appears to have a stronger influence on receipt of vaccine or refusal of a vaccine than do practical barriers.

Our findings of 23% HPV vaccine hesitancy are strikingly similar to the 26% vaccine hesitancy for influenza vaccination noted in a separate national survey using a national online panel, but much higher than the 6% vaccine hesitancy noted for routine childhood vaccines.45 That study used essentially the same methods including a slightly modified VHS scale to assess influenza and childhood vaccine hesitancy. Thus, it is now clear that parental hesitancy for HPV vaccine and influenza vaccine are about four-fold higher than is parental hesitancy for childhood vaccines. Interestingly, the types of concerns (vaccine safety and effectiveness) were similar in our study to concerns about influenza (or childhood) vaccines. We believe the findings from these two studies together highlight the urgent need to develop, implement, and scale up widely effective strategies to address vaccine hesitancy for these two vaccines (HPV and influenza).

Practical Barriers to HPV Vaccination:

A minority of parents also expressed practical barriers to HPV vaccination, including potential financial costs for vaccination, and lack of a regular source of medical care for their adolescent. These barriers were inversely related to HPV vaccination but not related, in general, to vaccine refusal. Clearly, efforts to overcome these access barriers are important. For example, healthcare providers should consider discussing with parents any concerns about financial barriers to vaccination. Despite the Vaccines for Children Program and high rates of commercial insurance coverage of vaccines, financial barriers for parents often include copays for visits as well as uncompensated time off from work.46 Similarly, despite recently having recorded the highest rate of insurance coverage for children ever in the US due to the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansions,47 insurance coverage has declined in the past 2 years48 and more parents might be facing financial barriers to vaccination. Similarly, it is highly concerning that more than 10% of parents indicated they do not have a regular source of medical care for their adolescent and many indicated they do not have a location for HPV vaccination. Efforts to expand access to care for adolescent vaccinations, including strategies within health systems and school-based vaccination49 may be needed to truly eliminate practical barriers to HPV vaccination. Importantly however, the finding that adjustment for practical barriers did not substantively change the association between hesitancy and HPV vaccine receipt suggests that hesitancy is a far greater challenge in HPV vaccination than are practical barriers.

Healthcare Provider Communication:

The CDC and other vaccine experts have been emphasizing the importance of a strong and effective provider recommendation for HPV vaccine, and the critical role that providers play in parents’ decision to accept or refuse the vaccine.14,24 In this study, only 79% of parents indicated that their adolescent’s primary care provider had “recommended the HPV vaccine.” Parental recall of a strong provider recommendation might be subject to recall bias, i.e., hesitant parents might be more likely to state their provider did not recommend the vaccine. Unfortunately, there is no easy method (and no studies to our knowledge) to relate parental recollection of provider communication about HPV vaccine with observations of provider communication about HPV vaccination. Also, it is possible that providers know from prior experience or parental communication that parents are hesitant and thus may not give a strong recommendation at the office visit. Nevertheless, our finding of a strong association between the provider having recommended the vaccine and receipt of HPV vaccinations supports prior studies14,50 of the critical role of the healthcare provider in HPV vaccination.

We were also surprised to find that more than 20% of parents expressed that they did not trust their pediatric provider’s information when it came to HPV vaccination. Healthcare providers need to be able to address these specific parental concerns about the HPV vaccine. Experts have begun studying strategies to better communicate with parents and adolescents about HPV vaccination, with some promising results.14,51–54 However, much more needs to be done to develop and implement scalable methods that are feasible within relatively limited office visit times, for clinicians and practices to optimally help parents in their decisions about HPV vaccination.

Addressing Both Hesitancy and Barriers:

In our study, vaccine hesitancy plus practical barriers did not appear to totally account for non-vaccination. For example, among the 38% of adolescents whose parents were not hesitant and had no practical barriers, only 74% of them had received >1 HPV vaccine and only 66% of them had completed their vaccine series. Further, one-fifth of hesitant parents reported that their adolescent still received ≥1 HPV vaccination. Together, these findings support efforts by researchers, public health leaders, and professional organizations to develop and implement both effective provider communication strategies and strategies beyond communication in a comprehensive effort to optimize HPV vaccination delivery. For example, several studies of practice quality improvement, and trials of provider prompts have noted improvement in HPV vaccinations.55–58

Sociodemographic Factors and HPV Vaccine Hesitancy:

In our study and other studies, sociodemographic factors were related to vaccine hesitancy. While findings from the 2010 US NIS-Teen Survey suggested that white parents and those with higher income and education were more likely to delay or refuse an HPV vaccine than other families,41 our study found that -- adjusting for other demographic characteristics -- being Hispanic and having family income >400% FPL were related to less hesitancy but no other factors were related to hesitancy. Having less hesitancy may be one reason why HPV vaccination rates among Hispanic adolescents is higher than among white adolescents.23,59 Anecdotal experience by some clinicians suggests higher HPV vaccine hesitancy among more educated parents; this was also noted by a recent study from France.60 We suspect that within local areas, different sociodemographic factors might be related to hesitancy than in our national sample of parents, and this might be related to sources of information about vaccines and even social norms.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first US survey to estimate HPV vaccine hesitancy in a nationally representative sample of parents while differentiating hesitancy from practical barriers to HPV vaccination. We used a slightly modified version of the VHS, and this instrument has previously been adapted from childhood vaccine hesitancy to assess HPV vaccine hesitancy.

Our study has limitations. First, survey data have inherent potential weaknesses, including response bias and reporting bias based on social desirability. Second, there is no “gold standard” scoring of the VHS from the literature, so we used a cut-off for HPV vaccine hesitancy (above half the scale) similar to what had been done for the PACV scale that assesses vaccine hesitancy among parents of young children.15 However, others could use different cut-offs. Third, the VHS may not be the optimal instrument to estimate HPV vaccine hesitancy. For example, it does not delve deeply into perceptions of the risk of HPV disease, although several of the questions imply the need for respondents to balance benefit from vaccination versus risks of not vaccinating. Clearly, more work is needed to reach consensus about the best way to measure HPV vaccine hesitancy and psychological domains and topics that drive hesitancy. Fourth, we relied on parental reports of receipt of HPV vaccines. Since this was a national online survey, we could not verify vaccine receipt. However, the parent-reported vaccination coverage in this study closely resembled national rates from the 2018 NIS-Teen23 and studies have found parent report to be a fairly accurate measure of HPV vaccine receipt.61,62 Finally, while we did not find an association between hesitancy and region of the country or metropolitan/non-metropolitan area, the sampling frame did not permit us to assess hesitancy specifically among rural parents. Efforts to address hesitancy and parental concerns need to occur in all regions.

Conclusions

About 23% of parents across the US are hesitant about the HPV vaccine, and parental vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with adolescents not receiving HPV vaccination. Concerns about vaccine safety, vaccine side effects, inadequate vaccine effectiveness, and lack of concern about HPV-related cancers were all common among parents, as was mistrust of physician information about HPV vaccine. Clinicians can use these findings to identify and address concerns among hesitant parents. Although practical barriers (mainly financial considerations and lack of access to care) were far less important than was parental vaccine hesitancy, health system and public health leaders might consider strategies to address these practical barriers, such as vaccinating during sick/chronic visits to reduce the need for additional visits for subsequent vaccinations, or alternative sites for vaccinations. These findings strongly support local, state, and national efforts to enhance confidence in HPV vaccination, to inform and educate our patients’ parents and the public, and to develop and disseminate strategies for addressing parental concerns about HPV vaccine.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA187707. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CRediT author statement:

Dr. Peter Szilagyi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization. Dr. Allison Kempe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing.Christina Albertin, Dennis Gurfinkel, Alison Saville, Rebecca Valderrama, Abigail Breck, Gregory Zimet, Cynthia Rand, and Sharon Humiston: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. Sitaram Vangala, Laura Helmkemp, and Dr. John Rice: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing.

All authors attest they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Declaration of interests:

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ten great public health achievements--United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards KM, Hackell JM, Committee On Infectious Diseases TCOP, Ambulatory M. Countering Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Kennedy A, et al. Physician response to parental requests to spread out the recommended vaccine schedule. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):666–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, et al. Measles outbreak--California, December 2014-February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(6):153–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald R, Ruppert PS, Souto M, et al. Notes from the field: Measles outbreaks from imported cases in Orthodox Jewish communities - New York and New Jersey, 2018–2019. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2019;19(7):2131–2133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson RM, St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJ. Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(11):1562–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST, Lindley MC, et al. Survey of Adult Influenza Vaccination Practices and Perspectives Among US Primary Care Providers (2016–2017 Influenza Season). J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2167–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, et al. Advancing Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Delivery: 12 Priority Research Gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S14–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf [accessed September 24, 2019].

- 11.Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1599–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedrich MJ. WHO’s Top Health Threats for 2019. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Narrative Review of Studies on How Providers’ Vaccine Communication Affects Attitudes and Uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S23–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, et al. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6598–6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrix KS, Sturm LA, Zimet GD, Meslin EM. Ethics and Childhood Vaccination Policy in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization, Vaccines and Biologicals. SAGE working group dealing with vaccine hesitancy (March 2012 to November 2014). Available at: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/sage_wg_vaccine_hesitancy_apr12/en/. Accessed December 31, 2019.

- 18.MacDonald NE, Hesitancy SWGoV. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, et al. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126 Suppl 2:135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilkey MB, McRee AL, Brewer NT. Forgone vaccination during childhood and adolescence: findings of a statewide survey of parents. Prev Med. 2013;56(3–4):202–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have received no vaccines: who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gust DA, Darling N, Kennedy A, Schwartz B. Parents with doubts about vaccines: which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):718–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markowitz LE, Gee J, Chesson H, Stokley S. Ten Years of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S3–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US DoHaHS. Healthy People 2020. 2012; http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=23.

- 26.Hirth JM, Fuchs EL, Chang M, Fernandez ME, Berenson AB. Variations in reason for intention not to vaccinate across time, region, and by race/ethnicity, NIS-Teen (2008–2016). Vaccine. 2019;37(4):595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono M, Daley EM. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: What Are the Reasons for Nonvaccination Among U.S. Adolescents? J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Amsel R, et al. Using an integrated conceptual framework to investigate parents’ HPV vaccine decision for their daughters and sons. Prev Med. 2018;116:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luyten J, Bruyneel L, van Hoek AJ. Assessing vaccine hesitancy in the UK population using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Vaccine. 2019;37(18):2494–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samsky MD, Lin L, Greene SJ, et al. Patient Perceptions and Familiarity With Medical Therapy for Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenborn NL, Crossnohere NL, Bridges JFP, Pollack CE, Pilla SJ, Boyd CM. Patient Perceptions of Diabetes Guideline Frameworks for Individualizing Glycemic Targets. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoenborn NL, Crossnohere NL, Janssen EM, et al. Examining Generalizability of Older Adults’ Preferences for Discussing Cessation of Screening Colonoscopies in Older Adults with Low Health Literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2512–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez Lynch H, Joffe S, Thirumurthy H, Xie D, Largent EA. Association Between Financial Incentives and Participant Deception About Study Eligibility. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishida JH, Wong PO, Cohen BE, Vali M, Steigerwald S, Keyhani S. Substitution of marijuana for opioids in a national survey of US adults. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4165–4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, et al. The vaccine hesitancy scale: Psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domek GJ, O’Leary ST, Bull S, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: Field testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy survey tool in Guatemala. Vaccine. 2018;36(35):5273–5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro GK, Holding A, Perez S, Amsel R, Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chyung SY, Roberts K, Swanson I, Hankinson A. Evidence-based survey design: The use of a midpoint on the Likert scale. Performance Improvement. 2017. Nov;56(10):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorell C, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. Delay and refusal of human papillomavirus vaccine for girls, national immunization survey-teen, 2010. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(3):261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, et al. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents: the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(4):419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1065–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kempe A SA, Albertin C. et al. , Parental Hesitancy About Routine Childhood and Influenza Vaccinations: A National Survey. Pediatrics. June 2020, e20193852 (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: a survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ugwi P, Lyu W, Wehby GL. The Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on Children’s Health Coverage. Med Care. 2019;57(2):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). MACStats. https://www.macpac.gov/macstats/. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- 49.Kempe A, Allison MA, Daley MF. Can School-Located Vaccination Have a Major Impact on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates in the United States? Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S101–S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokley S, Szilagyi PG. Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the United States: Executive Summary. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S1–S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dempsey AF, Pyrzanowski J, Campagna EJ, Lockhart S, O’Leary ST. Parent report of provider HPV vaccine communication strategies used during a randomized, controlled trial of a provider communication intervention. Vaccine. 2019;37(10):1307–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements Versus Conversations to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilkey MB, Parks MJ, Margolis MA, McRee AL, Terk JV. Implementing Evidence-Based Strategies to Improve HPV Vaccine Delivery. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dixon BE, Zimet GD, Xiao S, et al. An Educational Intervention to Improve HPV Vaccination: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Dhepyasuwan N, et al. Provider Communication, Prompts, and Feedback to Improve HPV Vaccination Rates in Resident Clinics. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niccolai LM, Hansen CE. Practice- and Community-Based Interventions to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Coverage: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Mayne S, et al. Effectiveness of decision support for families, clinicians, or both on HPV vaccine receipt. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1114–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimet G, Dixon BE, Xiao S, et al. Simple and Elaborated Clinician Reminder Prompts for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S66–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spencer JC, Calo WA, Brewer NT. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019;123:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rey D, Fressard L, Cortaredona S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy in the French population in 2016, and its association with vaccine uptake and perceived vaccine risk-benefit balance. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2018;23(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Attanasio L, McAlpine D. Accuracy of parental reports of children’s HPV vaccine status: implications for estimates of disparities, 2009–2010. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(3):237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ojha RP, Tota JE, Offutt-Powell TN, Klosky JL, Ashokkumar R, Gurney JG. The accuracy of human papillomavirus vaccination status based on adult proxy recall or household immunization records for adolescent females in the United States: results from the National Immunization Survey-Teen. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(5):281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]