Abstract

Background

Clinical risk factors in neonatal cardiac surgery do not fully capture discrepancies in outcomes. Targeted metabolomic analysis of plasma from neonates undergoing heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass was performed to determine associations with clinical outcomes.

Methods and Result

Samples and clinical variables from 149 neonates enrolled in the Corticosteroid Therapy in Neonates Undergoing Cardiopulmonary Bypass trial with surgical treatment for congenital heart disease between 2012 and 2016 were included. Blood samples were collected before skin incision, immediately after cardiopulmonary bypass, and 12 hours after surgery. Outcomes include composite morbidity/mortality (death, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, cardiac arrest, acute kidney injury, and/or hepatic injury) and a cardiac composite (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, cardiac arrest, or increase in lactate level), hepatic injury, and acute kidney injury. Targeted metabolite levels were determined by high‐resolution tandem liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Principal component and regression analyses were used to assess associations between metabolic profiles and outcomes, with 2 models created: a base clinical model and a base model+metabolites. Of the 193 metabolites examined, 40 were detected and quantified. The first principal component, principal component 1, was composed mostly of preoperative metabolites and was significantly associated with the composite morbidity/mortality, cardiac composite, and hepatic injury outcomes. In regression models, individual metabolites also improved model performance for the composite morbidity/mortality, cardiac composite, and hepatic injury outcomes. Significant disease pathways included myocardial injury (false discovery rate, 0.00091) and heart failure (false discovery rate, 0.041).

Conclusions

In neonatal cardiac surgery, perioperative metabolites were associated with postoperative outcomes and improved clinical model outcome associations. Preoperative metabolite levels alone may improve risk models and provide a basis for optimizing perioperative care.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, cardiac surgical procedures, cardiopulmonary bypass, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, heart defects, congenital, infant, newborn, risk factors

Subject Categories: Metabolism, Cardiovascular Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- FDR

false discovery rate; HPLC, high performance liquid chromotography; KEGG, Kyoto Encyopledia of Genes and Genomics

- PC

principal component

- PGE

prostaglandin E‐1

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

This study expands on perioperative metabolic changes, with a specific focus on neonates undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. This cohort is larger than prior studies, is multicenter, and has a larger panel of metabolites that are included in the analysis.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

A panel of metabolites that were primarily preoperative values was associated with postoperative outcomes, including death, renal and hepatic dysfunction, and cardiac arrest, which suggests that preoperative management could be more important than exposure to cardiopulmonary bypass.

Despite significant improvement in morbidity and mortality over the past 30 years, congenital heart surgery remains high risk. Neonates are among the most vulnerable of these patients, comprising mortality rates of 10%, compared with 3.0% and 1.7% in infants and adults, respectively. 1 , 2 Major and overall complication rates in neonates undergoing congenital heart surgery are high, at 19% and 67%, respectively, 3 leaving room for optimization of care. Current risk models incorporate clinical factors that are associated with increased morbidity and mortality, such as age, weight, preoperative status, including hospitalization before surgery, comorbidities, and surgical complexity. Perhaps the most widely recognized model, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery category, combines age, surgical complexity, and preoperative length of stay to model mortality risk of surgery. 4 However clinical factors are static and mostly not modifiable and therefore not useful for operational improvements in care.

Metabolomics is a dynamic measure of the physiological state that can be leveraged in pediatric cardiology. Because metabolites are the result of the complex interplay between the genetic substrate and environmental influences, a patient's metabolic profile offers insight on the phenotype of the patient in the moment of sampling. Metabolic profiling has shown superior risk prediction for death or hospitalization in adult patients with heart failure compared with current standards, such as brain natriuretic peptide. 5 Published data are less prevalent in the pediatric population, although studies have examined metabolomic fingerprinting in children undergoing cardiac surgery, with associations to outcome measures, such as mortality and intensive care unit length of stay. 6 , 7

The physiological disruptions experienced in neonates undergoing congenital heart surgery are why metabolomics could be enlightening for this vulnerable population. Disruptive factors include smaller body size, cyanosis, nutrition challenges, high likelihood of prostaglandin exposure preoperatively, and use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Although integral to cardiac surgery and thus life saving, CPB contributes to physiological derangements through exposure to nonphysiological pump circuit surfaces, organ ischemia/reperfusion, cooling, and rewarming. 8 , 9 The aims of this study are to: (1) describe perioperative changes in metabolic profiles in neonates requiring CPB, (2) associate metabolites with outcomes, and (3) identify potential metabolic pathways involved.

METHODS

Study Population

This study is a secondary analysis of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–funded, Corticosteroid Therapy in Neonates Undergoing Cardiopulmonary Bypass trial, a randomized controlled trial of intraoperative methylprednisolone or placebo (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01579513). Participants were enrolled between 2012 and 2016 from 2 enrolling sites. The trial primary end point was the incidence of a clinically derived composite morbidity‐mortality outcome with additional secondary end points. The trial design and clinical outcomes have been previously reported. 10 , 11 Data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Inclusion criteria for the parent study consisted of infants aged <1 month undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. Exclusion criteria included prematurity, defined as <37 weeks postgestational age at the time of surgery, steroids within the 2 days before surgery, suspected infection, hypersensitivity that would be a contraindication to methylprednisolone, or use of mechanical circulatory support or active resuscitation at the time of proposed randomization. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the participating centers, and written informed consent was obtained from a parent/guardian before randomization. This secondary study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

The parent study used a composite morbidity‐mortality outcome, which has been previously validated in neonates undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. 12 The composite outcome was met if any of the following occurred after surgery but before hospital discharge: death, cardiac arrest, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal injury (defined as creatinine >2 times normal), hepatic injury (defined as aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase >2 times normal >36 hours postoperatively), or increasing lactate level (defined as >5 mmol/L). To focus on a more cardiac functional measure, we developed a cardiac composite outcome that only included death, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, cardiac arrest, and increasing lactate level. Hepatic injury, using the same definition as in the composite outcome, and acute kidney injury (AKI), using the AKI Network's criteria, were further assessed individually from the composite morbidity/mortality outcome. 13 AKI was defined using the AKI Network's criteria for acute kidney injury as an increase in serum creatinine above the preoperative level by an absolute value of >0.3 mg/dL, a ≥50% increase, or urine output of <0.5 mL/kg per hour over a 6‐hour period. 14

Metabolite Identification and Quantification

Blood samples were collected from neonates at 3 time points: (1) before skin incision and steroid randomization, (2) immediately after CPB, and (3) 12 hours postoperatively. Samples were held on ice until the plasma was isolated, aliquoted, and then stored at −80 °C until assayed for metabolite concentrations using a targeted panel of 193 metabolites representing >366 metabolic pathways (Molecular Determinants Core at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, St. Petersburg, FL). The full assay list is in Table S1.

Samples were initially filtered, with extraction blanks (water) versus extraction reference (human plasma) included on the filtration plate. Filtration was accomplished using Supelco 96‐Well Protein Precipitation Filter Plate (Sigma Aldrich 55263‐U) paired with PlatePrep 96‐well Vacuum Manifold (Sigma Aldrich 57192‐U).

Samples were then delivered to the mass spectrometry ionization source by high‐pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), using a Shimadzu HPLC, a SIL‐30ACMP 6‐MTP autosampler, and Nexera LC‐30AD HPLC pumps. Targeted mass spectrometry assays used a Shimadzu 8060 triple‐quadrupole instrument equipped with an electrospray ionization source used in both positive and negative modes.

Spectral Peak Data Processing

After review and verification of the accuracy of peak integrations, measured areas for each compound were normalized for within‐batch drift by fitting a weighted scatterplot smoothing function generated from pooled quality control samples run between every 10th analytical sample. 15 , 16 Drift correction was performed using the R LOESS statistical package. To account for variation in extraction efficiency, samples were scaled using the response of a suite of isotopically labeled internal standards spiked into each sample at the beginning of the extraction procedure. Variations in overall instrument sensitivity between analytical batches were corrected by transforming raw data so that the mean within‐batch areas for each compound were equivalent.

Statistical Analysis

Metabolomic data were corrected for sample osmolarity and then normalized, with the rare missing value replaced by half the minimum detectable level. No additional preprocessing of metabolomic data was performed. Using paired t‐test analysis, metabolite concentrations at each time point were compared using a false discovery rate of 5% (Benjamini‐Hochberg correction), which also established the P‐value cutoff for significance. Metabolites that had significant differential expression between various time points were further divided into subcolumns based on increase or decrease in levels.

Additional features for association analysis were generated from metabolite concentrations, which included ratios between time points 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 2 and 3, along with a cumulative value of all 3 time points. With the number of patients, metabolites measured at each time point, and the additional features derived between time points, this was a complex data set. Principal component (PC) analysis was performed to determine association between metabolites, generated features, and outcomes. PC analysis permitted simplification of the data set by reducing the dimensionality (ie, summarizing) the variations in the data points into smaller segments, which are the PCs. 17 To investigate the contribution of the different PCs to the various clinical outcomes, we used logistic regression models for binary outcomes.

To develop the base clinical model, clinical factors with known associations with surgical outcomes were evaluated for inclusion. Preliminary factors group assignment, steroid administration, cardiopulmonary bypass duration, and similar surgical factors ultimately included surgical center, preoperative prostaglandin E‐1 (PGE) exposure, Society of Thoracic Surgeons category, preoperative lactate level, and gestational age at birth. PGE was included as a clinical variable because of the extensive hormonal, 18 renal, 19 hematologic, 20 and other systemic effects of PGE, 21 in addition to the associated high‐risk physiologies that require PGE infusions for ductal patency. The following performance metrics were determined for the base clinical model (including only adjustment factors): Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for binary and continuous outcomes and Wald X2 and c‐statistic for continuous outcomes. A second model was then created, by taking the base model followed by stepwise selection of the first 6 PC loads (based on examination of the scree plot), with P≤0.05 to include and P>0.05 to discard. Performance metrics were repeated for this second model (base model+PCs).

A final, third, model was created to determine associations between individual metabolites (or features derived from them) and outcomes. A multistep approach for model building was used, starting with narrowing the list of potential associated features for each outcome. Features with a P<0.10 (indicating a potential association between the outcome and the features) were identified for each outcome, followed by a bootstrap resampling approach (500 samples, including between 20% and 80% of the total observations) to identify features with high reliability. Features with scores >50% were considered highly reliable. For the next step, we selected features with reliability scores >30%. Thereafter, the final regression models were built using backward elimination (P<0.05 to remain) and included the clinical adjustment variables, the first 6 PC loads, and all metabolites or features thereof that met the above‐mentioned reliability criteria. In some cases where 2 highly correlated features were both candidates for inclusion in the multivariable model, an intermediate step was added to compare the model with either feature, and the feature resulting in the best model fit (based on a lower model AIC) was selected.

Metabolite Enrichment Disease and Pathway‐Associated Analysis

Final metabolites from the models or their features that improved an outcome were then evaluated using Metaboanalyst 5.0 for disease and metabolic pathways. 22 Findings were then compared for relevance to the outcome assessed and prior studies linking to diseases or pathways.

RESULTS

Subject Demographics

Samples from a total of 154 participants were available; of those, 5 subjects were excluded because of a missing sample for at least 1 of the time points. The final cohort included 149 patients who had metabolomic data available at all 3 time points. Demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The cohort consisted of 89 male patients (60%), and patients fit into following diagnostic categories: 27 (18%) biventricular physiology and arch hypoplasia, 37 (25%) transposition of the great arteries, 40 (27%) biventricular physiology not previously listed, and 45 (30%) with single‐ventricle physiology. Most (79%) remained on PGE before surgery, and 87% had PGE exposure at some point before surgery. This is expected as most congenital heart disease that requires surgery in the neonatal period has a ductal‐dependent physiology. Median age at surgery was 7 days (interquartile range, 5–10 days). A total of 55 patients (37%) experienced the composite morbidity/mortality trial outcome, 34 (23%) experienced the cardiac composite, 66 (44%) experienced AKI, 29 (19%) experienced elevated lactate level, and 38 (26%) experienced hepatic injury.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics and Clinical Status

| Patient characteristics | Values, mean±SD or N (%) | Patient characteristics (cont.) | Values, mean±SD or N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N) | 149 | Surgical outcomes | |

| Site 2 (vs site 1) | 38 (26) | Low cardiac output syndrome | 69 (46) |

| Methylprednisolone arm | 71 (48) | Mechanical cardiac support | 3 (2) |

| Increase inotropic support by 100% | 50 (34) | ||

| Characteristics/clinical history | New inotropic agents | 40 (27) | |

| Age, d | 8.7±5.3 | Highest IS at 36 h | 17.1±4.7 |

| Gestational age at birth, wk | 38.9±1.2 | Highest VIS at 36 h | 19.2±6.9 |

| Sex (male) | 89 (60) | Highest lactate level at 36 h (mmol/L) | 4.0±2.4 |

| Diagnosis | Ventilation time, d | 7.7±15.1 | |

| Biventricular with arch hypoplasia | 27 (18) | ICU length of stay, d | 17.0±20.6 |

| TGA | 37 (25) | Hospital length of stay, d | 30.4±39.1 |

| All other biventricular disorders | 40 (27) | ||

| SV | 45 (30) | Mortality/morbidity composite outcomes | 55 (37) |

| Death | 7 (5) | ||

| Preoperative status | Cardiac arrest | 9 (6) | |

| Intubation before surgery | 36 (24) | ECMO | 7 (5) |

| PGE within 24 h of surgery | 117 (79) | Renal | 6 (4) |

| PGE ever before surgery | 130 (87) | Hepatic | 38 (26) |

| MOD ever before surgery | 11 (7) | Lactate level | 28 (19) |

| Highest creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8±0.5 | Cardiac composite outcome | 34 (23) |

| Highest lactate level (mmol/L) | 3.5±2.7 | AKI | 66 (44) |

| Lactate level on day of surgery (mmol) | 1.1±0.43 | ||

| Corrective procedure | 90 (60) | ||

| STAT category | |||

| 1–3 | 32 (21) | ||

| 4 | 77 (52) | ||

| 5 | 40 (27) | ||

| CPB time, min | 74.8±42.5 | ||

| DHCA, min | 9.9±65.1 |

AKI indicates acute kidney injury; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IS, inotropic score; MOD, multiorgan dysfunction; PGE, prostaglandin E‐1; STAT, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; SV, single ventricle; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; and VIS, vasopressor/inotropic score.

Differential Expression of Metabolites at Time Points

Of the 193 metabolites examined, 40 were detected and quantifiable in all 149 participants. The other 153 metabolites were not consistently identified or quantified. Results from paired t‐test analysis comparing metabolite concentrations at various time points are shown in Table 2. A total of 34 metabolites changed significantly between all measured time points. The general pattern was either an immediate postoperative decrease or increase, with a trend back toward the preoperative baseline. There were many exceptions to this pattern, including methyladenosine, which showed a delayed increase at the 12‐hour post‐op; leucine and nicotinamide, which had the inverse finding of a delayed decrease at the 12‐hour post‐op time point; arginine, isoleucine, methionine, methionine sulfoxide, ornithine, serine, and glycocholic acid, all of which continued to decrease at the time points measured; and paraxanthine, indoxyl sulfate, and hippuric acid, which increased across all time points.

Table 2.

Metabolites With Statistically Significant Differences Between Different Time Points

| Preoperative vs T2 | T2 vs T3 | Preoperative vs T3 |

|---|---|---|

| Arginine* | Arginine* | Arginine* |

| Aspartic acid* | Isoleucine* | Asparagine |

| Carnitine* | Leucine* | Aspartic acid* |

| Creatinine* | Methionine* | Carnitine* |

| Glutamine* | Methionine sulfoxide* | Creatinine |

| Glutamic acid* | Nicotinamide* | Glutamine* |

| Histidine* | Ornithine* | Glutamic acid* |

| 4‐Hydroxyproline* | Proline* | Histidine* |

| Isoleucine* | Gluconic acid* | 4‐Hydroxyproline* |

| Lysine* | Galactitol* | Isoleucine* |

| Methionine* | 4‐Pyridoxic acid* | Leucine* |

| Methionine sulfoxide* | Glycocholic acid* | Lysine* |

| Ornithine* | Sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphochocholine* | Methionine* |

| Phenylalanine* | 1‐Methyladenosine† | Methionine sulfoxide* |

| Proline* | N‐acetylserine† | Nicotinamide* |

| Serine* | Histidine† | Ornithine* |

| Tryptophan* | Homoserine† | Phenylalanine* |

| Homoserine* | Carnitine† | Proline* |

| 5‐Oxoproline* | Creatinine† | Serine* |

| 3‐Methoxytyrosine* | Asparagine† | Tryptophan* |

| N‐acetylserine* | 5‐Oxoproline* | |

| Glycocholic acid* | 3‐Methoxytyrosine* | |

| Gluconic acid† | Glycocholic acid* | |

| N‐acetyltryptophan† | Gluconic acid† | |

| Paraxanthine† | Paraxanthine† | |

| Galactitol† | Galactitol† | |

| Indoxyl sulfate† | 1‐Methyladenosine† | |

| Sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine† | Indoxyl sulfate† | |

| Hippuric acid† | Sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine† | |

| Hippuric acid† | ||

| N‐acetylserine† |

For metabolites with statistically significant differences, the fold change cutoff was 0.5/2.0 (P‐value cutoff, 0.0125). * indicates significant decrease; †, significant increase. T2 indicates immediate postoperative; and T3, 12 hours postoperative.

Association of Metabolites to Clinical Outcomes

The first 6 components of the PC analysis performed on metabolites and features individually had loads >3% and together explained 51% of the cumulative variance in metabolic compounds (detailed features of PCs in Table S2). In univariate analysis (Table 3), PC1 alone was significantly associated with the composite morbidity/mortality, cardiac composite, and hepatic injury outcomes. PC1 and PC3 were associated with acute kidney injury, and PC1 and PC6 were associated with increasing lactate level. Of the PC loads, PC1 was of special interest as 14 of the 20 metabolites within this group were preoperative (Table S2).

Table 3.

Association of PCs With Clinical Outcomes With Univariate Analysis

| Outcome | PC* | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite: mortality/morbidity | PC1 | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Composite: cardiac† | PC1 | 1.14 (1.05–1.25) | 0.003 |

| Hepatic | PC1 | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | <0.001 |

| Lactate level | PC1 | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | 0.01 |

| PC6 | 1.25 (1.01–1.54) | 0.04 | |

| AKI | PC1 | 1.06 (1.01–1.13) | 0.03 |

| PC3 | 1.09 (1.01–1.16) | 0.02 |

AKI indicates acute kidney injury; OR, odds ratio; and PC, principal component.

Significant PC.

Only includes death, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, cardiac arrest, and lactate level outcomes.

A base clinical model (adjusted for enrolling site, PGE use, Society of Thoracic Surgeons category, presurgery lactate level, and gestational age at birth) was significantly associated with composite morbidity/mortality, cardiac composite, and hepatic injury outcomes, but not AKI (Table 4). Of note, an additional analysis including steroid versus placebo administration was also run, without changes in results, so this factor was not included in further analysis. To determine if metabolite levels could improve the base clinical model performance, the 6 top PCs were incorporated into a regression analysis with the base clinical model (base model+metabolite PCs) and compared with the base clinical model using AIC, Wald X2, and c‐statistic as performance metrics (Table 4 and Table S3). For comparison, a lower AIC and higher c‐statistic indicate improved model fit. Both the base clinical model and the base model+metabolite PCs were significant in their associations to the outcomes. However, the second model had improved model fit, as indicated in the difference in AIC and c‐statistic. The addition of PC1 significantly improved the clinical model performance for the composite morbidity/mortality outcome, composite cardiac outcome, and hepatic injury (PC1 and PC3 for acute kidney injury and PC1 and PC6 for lactate level).

Table 4.

Model Comparison of Associations Between PC Loads and Binary Outcomes With Multivariate Regression Analysis

| Outcome | Base model* | Base model+PC | Base model+individual metabolites† | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | Wald χ2 | P value | C‐statistic | AIC | Wald χ2 | P value | C‐statistic | Significant PC | AIC | Wald χ2 | P value | C‐statistic | Significant PC | |

| Composite: mortality/morbidity | 158.3 | 33.5 | <0.001 | 0.828 | 137.3 | 38.2 | <0.001 | 0.879 | PC1 | 90.0 | 27.6 | 0.006 | 0.967 | None |

| Composite: cardiac‡ | 140.2 | 24.7 | <0.001 | 0.805 | 129.2 | 29.0 | <0.001 | 0.850 | PC1 | 113.0 | 30.4 | <0.001 | 0.905 | None |

| Hepatic | 150.0 | 23.1 | <0.001 | 0.788 | 121.7 | 32.5 | <0.001 | 0.884 | PC1 | 99.5 | 32.1 | <0.001 | 0.936 | None |

| Lactate level | 123.8 | 32.2 | <0.001 | 0.817 | 116.6 | 27.3 | <0.001 | 0.845 | PC1 | 93.5 | 27.1 | 0.001 | 0.930 | None |

| AKI | 210.9 | 5.3 | 0.38 | 0.607 | 204.6 | 13.6 | 0.06 | 0.672 | PC1, PC3 | 182.0 | 29.6 | 0.003 | 0.811 | PC6 |

AIC indicates Akaike Information Criterion; AKI, acute kidney injury; and PC, principal component.

Adjusted for site, preoperative prostaglandin E‐1, Society of Thoracic Surgeons category, preoperative lactate value, and gestational age at birth.

Individual metabolites, as listed in Table S4.

Only includes death, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, cardiac arrest, and lactate level outcomes.

Association of Individual Metabolites With Outcomes

Given the significance of the association between clinical outcomes and metabolite PC loads, and improvement in base model+metabolite PCs compared with the clinical base model alone, we further investigated the association between individual metabolites (or features derived from them) and outcomes. As shown in Table 5, individual metabolites and features were significantly associated with outcomes. Individual performance metrics for the base model+individual metabolites are detailed in Table S4. Significant individual metabolites improved (lower AIC and higher c‐statistic) the clinical model for the composite morbidity/mortality outcome, composite cardiac outcome, hepatic injury, and lactate level outcomes (Table 4). Association of individual metabolites with outcomes was not improved by including PC loads in the model for the composite morbidity/mortality outcome, composite cardiac outcome, hepatic injury, and lactate level outcomes.

Table 5.

Significant Individual Metabolites or Metabolite Features Associated With an Outcome

| Composite: morbidity/mortality | Composite: cardiac | Composite: hepatic | Composite: lactate level | AKI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

t1 Ornithine t1 Phenylalanine t1 Methionine t3 Cystine t3 4‐Hydroxyproline t3 3‐Methoxytyrosine r21 Homoserine |

Cum proline t3 proline t3 leucine |

t1 Carnitine t1 Aspartic acid t3 Tyrosine |

t1 Methionine r31 Galactitol t3 Proline t3 Leucine |

t1 Ornithine t1 Isoleucine t1 Aspartic acid t3 Alanine t3 Glutamic acid t3 4‐Hydroxyproline t3 Serine |

AKI indicates acute kidney injury; Cum, cumulative concentration from all time points; r21, ratio between time points 1 and 2; r31, ratio between time points 1 and 3; t1, time point 1 (preop); t2, time point 2 (immediate post‐op); t3, time point 3 (12 hours post‐op).

Metabolite Enrichment Pathway and Disease‐Associated Analysis

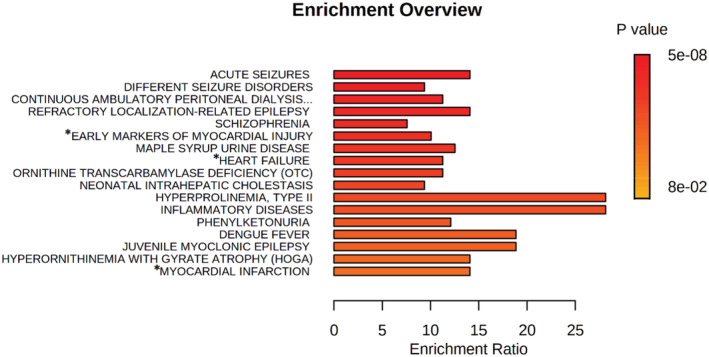

For the individual metabolites or features associated with clinical outcomes, we explored the metabolic pathways (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, (KEGG)) associated and if disease associated. Significant false discovery rate (FDR; <0.05) KEGG pathways represented included aminoacyl‐tRNA biosynthesis, arginine biosynthesis, and metabolism of multiple amino acids. Using metabolite enrichment disease pathway analysis (Figure and Table 6), individual metabolites were significantly (FDR, <0.05) associated with disease pathways, including seizures (FDR, 2.67×10−6), early markers of myocardial injury (FDR, 0.00091), and heart failure (FDR, 0.041).

Figure . Metabolite enrichment disease pathway analysis.

Metabolite enrichment disease pathway analysis using individual metabolites that improved on the base model (listed in S4). Disease associations with metabolites are in the figure listed above. Asterisks (*) indicate attention to cardiac diseases that are of special interest to this patient population.

Table 6.

Metabolite Disease Enrichment Analysis

| Metabolite set enrichment analysis | Total | Hits | Raw P value | FDR | Perioperative metabolites associated with disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute seizures | 14 | 7 | 9.78E‐09 | 2.67E‐06 | L‐alanine, L‐methionine, L‐leucine, L‐isoleucine, L‐phenylalanine, L‐histidine, L‐tryptophan |

| Different seizure disorders | 24 | 8 | 2.83E‐08 | 3.87E‐06 | L‐alanine, L‐histidine, L‐isoleucine, L‐leucine, L‐methionine, L‐phenylalanine, L‐threonine, L‐tryptophan, L‐tyrosine |

| Refractory localization‐related epilepsy | 10 | 5 | 2.26E‐06 | 0.000154 | L‐lysine, L‐leucine, L‐isoleucine, L‐phenylalanine, L‐tyrosine |

| Early markers of myocardial injury | 14 | 5 | 1.69E‐05 | 0.00091 | L‐alanine, L‐isoleucine, L‐leucine, L‐proline, L‐serine |

| Heart failure | 10 | 3 | 0.00212 | 0.0414 | L‐isoleucine, L‐leucine, L‐tyrosine |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.104 | L‐phenylalanine, L‐tyrosine |

FDR indicates false discovery rate.

DISCUSSION

Early identification of patients at risk for postoperative morbidity could improve outcomes. Clinical models alone using known, or suspected, risk factors, such as age, known comorbidities, weight, and complexity of surgery, have offered some insight into mortality risk, but may have no applicability to subtler organ‐specific injury. The findings of this study show a significant association with metabolites and multiple clinical outcomes, and metabolite data improved on a clinical‐only risk model. This study also suggests that metabolites may provide an actionable target to improve outcomes following congenital cardiac surgery. Prior studies comparing perioperative shifts in metabolic profiles and the relationship to postoperative outcomes have suggested the utility of incorporating metabolites into outcome prediction and/or risk stratification. 6 , 7 These pediatric studies have been limited by small patient cohort sizes from single centers and a broad age range. Our work expands on these studies using a multicenter and larger cohort, with a specific focus on neonates requiring cardiac surgery with CPB. This study also benefits from an expanded targeted assay panel of 193 metabolites. These measures allowed us to explore the potential metabolic pathways more specific to neonatal cardiac surgery and recovery.

In regard to the significant perioperative metabolite changes identified, these mostly represented aminoacyl‐tRNA biosynthesis, arginine biosynthesis, and metabolism of multiple amino acids pathways. Enrichment analysis revealed that many of the individual metabolites were previously identified in studies of cardiac dysfunction and seizures, reflecting both cardiac dysfunction 23 , 24 , 25 and neurologic injury, 26 which are common postoperative morbidities. Although seizures were not recorded in the primary trial, we have shown previously that the brain injury biomarker GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) was increased postoperatively in this cohort and was associated with a worse Bayley Scale of Infant Development III score at 12 months of age, 27 providing evidence of at least postoperative subclinical brain injury in this cohort and consistent with findings of seizure‐associated metabolites. Three (L‐isoleucine, L‐leucine, and L‐tyrosine) of the 8 amino acids associated with seizures were also associated with acute myocardial injury and heart failure, which could reflect a more global injury phenotype as opposed to specific organ injury.

Previously, dysregulation of glutathione and amino acid synthesis pathways was identified after congenital heart surgery and was confirmed in this study. 6 , 7 Shifts in glutathione metabolism are relevant to our study because glutathione has a role in antioxidant defense, nutrient metabolism, and regulation of protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. 28 We found this compelling as neonates typically have limited glycogen and fat energy stores; therefore, they are more reliant on glucose‐derived energy. Feeding preoperatively is typically restricted in neonates with congenital heart disease, with dependence on intravenous nutrition in the form of dextrose‐containing fluids. Because of these feeding patterns, we postulate that our patients are at risk of even more poorly developed energy stores, which could explain glutathione dysregulation.

For most outcomes measured, high PC1 was universally associated with poor outcomes. Analyzing the individual components of this PC, we were surprised to find many of the metabolites were preoperative values, with the remaining components being cumulative values. This suggests that these patients were at risk because of their preoperative physiological state, and not because of surgical factors (CPB duration, circulatory arrest, and cross‐clamp time). In the initial conceptualization of this study, we had hypothesized that the changes from surgery and CPB would be the most influential on patient outcomes. The recurring importance of PC1 strongly suggests that the patient's preoperative physiological state could be most important modification for improving morbidity and mortality. 23 , 24 , 25 , 29 , 30 As in the study by Davidson et al, 6 essential amino acids (leucine, methionine, and phenylalanine) were found to be associated with worse outcomes, in addition to conditionally essential (cystine and proline). The continued relevance of amino acids between our study and prior work supports the role that nutritional status plays in improving outcomes.

Despite increased cohort size compared with prior works, this study remains limited by a relatively small cohort produced from only 2 participating sites. Statistical analysis relied heavily on PC analysis, which allowed for interpretation of complex data in this relatively small cohort. A more straightforward approach using regression analysis for each metabolite against each outcome would likely have missed significant findings because of the smaller sample size. The drawback is that a general metabolic profile can be associated with an outcome (a PC), without individual metabolites being as clearly linked.

Other limitations include the primary trial enrolling criteria, and exclusion of younger neonates (aged <37 weeks) or older infants/children, which also left us unable to determine whether metabolite changes differ between these patient populations. These results may not be necessarily generalizable to nonneonates. Last, we used a targeted metabolomic analysis, which lacked a full range of metabolites, such as membrane and vasoactive lipids, which could potentially be informative.

The association between metabolites and outcomes in neonatal cardiac surgery that we have demonstrated herein suggests an additional tool beyond clinical data to help identify patients at risk for poor outcomes. What we found most promising was the association between preoperative metabolic profiles and outcomes of interest, suggesting improvement in outcomes begins preoperatively. Further research would include validation studies, and metabolomics in expanded age groups, in addition to targeted analysis of identified pathways. The proposed mechanism of preoperative nutritional status and effect on operational outcomes would bear further investigation also.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by The Children's Heart Foundation (Dr Everett).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S4

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.024996

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hasegawa T, Masuda M, Okumura M, Arai H, Kobayashi J, Saiki Y, Tanemoto K, Nishida H, Motomura N. Trends and outcomes in neonatal cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease in Japan from 1996 to 2010. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51:301–307. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacobs JP, O'Brien SM, Pasquali SK, Gaynor JW, Mayer JE Jr, Karamlou T, Welke KF, Filardo G, Han JM, Kim S, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database mortality risk model: part 2‐clinical application. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1063–1068; discussion 1068–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costello JM, Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, He X, Hill KD, Cooper DS, Backer CL, Jacobs ML. Gestational age at birth and outcomes after neonatal cardiac surgery: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Circulation. 2014;129:2511–2517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jacobs ML, O'Brien SM, Jacobs JP, Mavroudis C, Lacour‐Gayet F, Pasquali SK, Welke K, Pizarro C, Tsai F, Clarke DR. An empirically based tool for analyzing morbidity associated with operations for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1046–1057.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang CH, Cheng ML, Liu MH. Amino acid‐based metabolic panel provides robust prognostic value additive to B‐natriuretic peptide and traditional risk factors in heart failure. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:3784589. doi: 10.1155/2018/3784589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davidson JA, Pfeifer Z, Frank B, Tong S, Urban TT, Wischmeyer PA, Mourani P, Landeck B, Christians U, Klawitter J. Metabolomic fingerprinting of infants undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass: changes in metabolic pathways and association with mortality and cardiac intensive care unit length of stay. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010711. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Correia GDS, Ng KW, Wijeyesekera A, Gala‐Peralta S, Williams R, MacCarthy‐Morrogh S, Jiménez B, Inwald D, Macrae D, Frost G, et al. Metabolic profiling of children undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1467–1476. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ashraf S, Bhattacharya K, Tian Y, Watterson K. Cytokine and S100B levels in paediatric patients undergoing corrective cardiac surgery with or without total circulatory arrest. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16:32–37. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(99)00136-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alcaraz AJ, Manzano L, Sancho L, Vigil MD, Esquivel F, Maroto E, Reyes E, Alvarez‐Monet M. Different proinflammatory cytokine serum pattern in neonate patients undergoing open heart surgery. Relevance of IL‐8. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:238–245. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4081-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graham EM, Martin RH, Buckley JR, Zyblewski SC, Kavarana MN, Bradley SM, Alsoufi B, Mahle WT, Hassid M, Atz AM. Corticosteroid therapy in neonates undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:659–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zyblewski SC, Martin RH, Shipes VB, Hamlin‐Smith K, Atz AM, Bradley SM, Kavarana MN, Mahle WT, Everett AD, Graham EM. Intraoperative methylprednisolone and neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113:2079–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butts RJ, Scheurer MA, Zyblewski SC, Wahlquist AE, Nietert PJ, Bradley SM, Atz AM, Graham EM. A composite outcome for neonatal cardiac surgery research. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butts RJ, Scheurer MA, Atz AM, Zyblewski SC, Hulsey TC, Bradley SM, Graham EM. Comparison of maximum vasoactive inotropic score and low cardiac output syndrome as markers of early postoperative outcomes after neonatal cardiac surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:633–638. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0193-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A; Acute Kidney Injury Network . Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Livera AM, Sysi‐Aho M, Jacob L, Gagnon‐Bartsch JA, Castillo S, Simpson JA, Speed TP. Statistical methods for handling unwanted variation in metabolomics data. Anal Chem. 2015;87:3606–3615. doi: 10.1021/ac502439y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunn WB, Wilson ID, Nicholls AW, Broadhurst D. The importance of experimental design and QC samples in large‐scale and MS‐driven untargeted metabolomic studies of humans. Bioanalysis. 2012;4:2249–2264. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ringnér M. What is principal component analysis? Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:303–304. doi: 10.1038/nbt0308-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nio‐Kobayashi J, Kudo M, Sakuragi N, Iwanaga T, Duncan WC. Loss of luteotropic prostaglandin E plays an important role in the regulation of luteolysis in women. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23:271–281. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gax011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antonucci R, Cuzzolin L, Arceri A, Fanos V. Urinary prostaglandin E2 in the newborn and infant. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;84:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlagenhauf A, Haidl H, Leschnik B, Leis HJ, Heinemann A, Muntean W. Prostaglandin E2 levels and platelet function are different in cord blood compared to adults. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:97–106. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newman WP, Brodows RG. Metabolic effects of prostaglandin E2 infusion in man: possible adrenergic mediation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:496–501. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-3-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pang Z, Chong J, Li S, Xia J. MetaboAnalystR 3.0: toward an optimized workflow for global metabolomics. Metabolites. 2020;10:186. doi: 10.3390/metabo10050186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nørrelund H, Wiggers H, Halbirk M, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Bøtker HE, Schmitz O, Jørgensen JOL, Christiansen JS, Møller N. Abnormalities of whole body protein turnover, muscle metabolism and levels of metabolic hormones in patients with chronic heart failure. J Intern Med. 2006;260:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira A, Bettencourt P, Pestana M, Correia F, Serrão P, Martins L, Cerqueira‐Gomes M, Soares‐Da‐Silva P. Heart failure, aging, and renal synthesis of dopamine. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:502–509. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.26834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewis GD, Wei R, Liu E, Yang E, Shi X, Martinovic M, Farrell L, Asnani A, Cyrille M, Ramanathan A, et al. Metabolite profiling of blood from individuals undergoing planned myocardial infarction reveals early markers of myocardial injury. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3503–3512. doi: 10.1172/JCI35111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Everett AD, Buckley JP, Ellis G, Yang J, Graham D, Griffiths M, Bembea M, Graham EM. Association of neurodevelopmental outcomes with environmental exposure to cyclohexanone during neonatal congenital cardiac operations: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e204070. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Graham EM, Martin RH, Atz AM, Hamlin‐Smith K, Kavarana MN, Bradley SM, Alsoufi B, Mahle WT, Everett AD. Association of intraoperative circulating‐brain injury biomarker and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 1 year among neonates who have undergone cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:1996–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu GY, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J Nutr. 2004;134:489–492. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Du X, You H, Li Y, Wang Y, Hui P, Qiao B, Lu J, Zhang W, Zhou S, Zheng Y, et al. Relationships between circulating branched chain amino acid concentrations and risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with STEMI treated with PCI. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15809. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34245-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ronca F, Raggi A. Structure‐function relationships in mammalian histidine‐proline‐rich glycoprotein. Biochimie. 2015;118:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S4