Abstract

A selection strategy has been developed to identify amino acid residues involved in subunit interactions that coordinate the two half-reactions catalyzed by glutamine amidotransferases. The protein structures known for this class of enzymes have revealed that ammonia is shuttled over long distances and that each amidotransferase evolved different molecular tunnels for this purpose. The heterodimeric Escherichia coli imidazole glycerol phosphate (IGP) synthase was probed to assess if residues in the substrate amination subunit (HisF) are critical for the glutaminase activity in the HisH subunit. The activity of the HisH subunit is dependent upon binding of the nucleotide substrate at the HisF active site. This regulatory function has been exploited as a biochemical selection of mutant HisF subunits that retain full activity with ammonia as a substrate but, when constituted as a holoenzyme with wild-type HisH, impair the glutamine-dependent activity of IGP synthase. The steady-state kinetic constants for these IGP synthases with HisF alleles showed three distinct effects depending upon the site of mutation. For example, mutation of the R5 residue has similar effects on the glutamine-dependent amidotransfer reaction; however, kcat/Km for the glutaminase half-reaction was increased 10-fold over that for the wild-type enzyme with nucleotide substrate. This site appears essential for coupling of the glutamine hydrolysis and ammonia transfer steps and is the first example of a site remote to the catalytic triad that modulates the process. The results are discussed in the context of recent X-ray crystal structures of glutamine amidotransferases that relate the glutamine binding and acceptor binding sites.

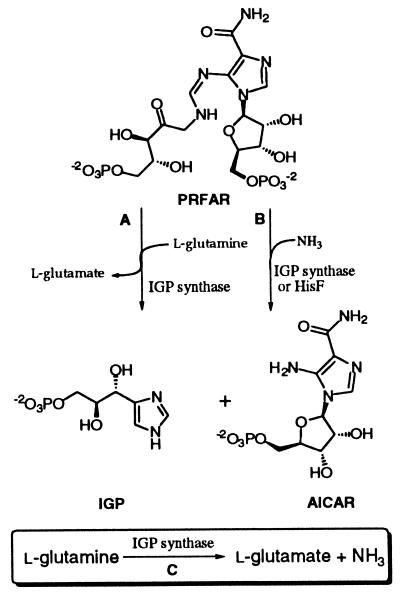

Glutamine amidotransferases (GATs) are responsible for the introduction of nitrogen onto a diverse array of substrates and play a central role in normal nitrogen metabolism (32). Imidazole glycerol phosphate (IGP) synthase is a GAT that plays an essential role in histidine biosynthesis. This enzyme catalyzes a sequence of reactions that forms the imidazole ring of histidine from glutamine and the substrate N1-[(5′-phospho-ribulosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribo-nucleotide (PRFAR) (Fig. 1, reaction A) (11). The global structure of IGP synthase is an example of the general theme for GATs that consist of two functional domains: the glutamine binding domain that hydrolyzes the amide bond of glutamine (Fig. 1, reaction C) and an acceptor domain that aminates the acceptor substrate (33). For the bacterial IGP synthase, these domains are found on distinct subunits where the HisH subunit binds glutamine and the HisF subunit aminates the acceptor substrate to form the imidazole ring. The domains can also lie within a single polypeptide, as is the case for IGP synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (6, 14). Like many other amidotransferases, IGP synthase or HisF alone can catalyze the complete amination reaction using ammonium salts (Fig. 1, reaction B). However, the physiological nitrogen source is glutamine and requires an association with HisH to form the active holoenzyme (11).

FIG. 1.

The reactions catalyzed by IGP synthase and HisF. Reaction A is the glutamine-dependent IGP synthase reaction, reaction B is the amino-dependent IGP synthase, and reaction C is the glutaminase reaction.

GATs are grouped into two families based upon amino acid sequence alignments of the glutamine binding domains. IGP synthase is an example of a “Triad” GAT, with a strictly conserved catalytic triad of cysteine, histidine, and glutamate residues in the HisH subunit (33). “Ntn” GATs, represented by phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) amidotransferase, share a catalytic cysteine at the N terminus. The differences in the catalytic machinery for amide bond cleavage are demonstrated in the three-dimensional structures determined for members from each family (28–30).

A fundamental question that remains unanswered is how the structures of the amidotransferases ensure coupling of the two reactions and allow efficient transfer of ammonia from the glutaminase site to the acceptor site. For GATs like IGP synthase, a basal, unregulated glutaminase activity that hydrolyzes glutamine to glutamate can be detected (Fig. 1, reaction C), but the catalytic efficiency for this glutaminase is highly reduced relative to the amidotransferase activity. In the absence of the acceptor substrate, the glutaminase turnover can be stimulated by compounds that bind in the acceptor site (11, 20, 22, 34). The acceptor substrate initiates the amidotransferase activity that relies on both an increased affinity for glutamine and an obligatory 1:1 stoichiometry between glutamine hydrolysis and substrate amination (2, 11). Thus, the different conformational states that define whether an enzyme behaves as a glutaminase or a GAT appear to be dictated by domain interactions that occur once the substrate or an analog is bound to the enzyme active site (31, 33). The emerging structural information regarding this class of enzymes highlights the challenges of unraveling a molecular mechanism that accounts for these profound functional properties (12, 23).

Our previous study of Escherichia coli IGP synthase showed that association of the acceptor and glutamine binding domains is essential for glutaminase activity (11). The HisH subunit alone exhibits no glutaminase activity and is dependent upon HisF for its stability in solution. To understand the role of the acceptor domain in glutamine utilization by IGP synthase and related GATs, we have performed random mutagenesis of the HisF (synthase) subunit. By use of a genetic selection method based upon the known biochemical properties of IGP synthase, mutants deficient in glutamine utilization as a nitrogen source without affecting the glutamine binding subunit have been identified for the first time. IGP synthase is an attractive target for these studies because separate genes, permitting localization of the mutant phenotypes to the HisF subunit, encode the functional domains. Secondly, HisF catalyzes no other partial or side reactions and simplifies the interpretation of the results from a mutant screen. Finally, the subunits of the enzyme can be readily associated for in vitro biochemical analyses. The kinetic analyses of selected mutants have enabled an exploration of how such mutations may result in a glutamine-deficient phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Ampicillin, acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide (APAD) for glutaminase assays, and streptomycin sulfate were from Sigma. Deoxynucleotide triphosphates and glutamate dehydrogenase were from Boehringer Mannheim. l-Glutamine was from Aldrich. Bacto Agar, Bacto Tryptone, and yeast extract were from Difco. Radioisotopes were from Amersham. N-Succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio) propionate (SPDP) for protein cross-linking studies was from Pierce. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was from Gold Biotechnology. Restriction endonucleases, DNA modifying enzymes, and buffers were from New England Biolabs, Promega, and U.S. Biochemical Corporation. DEAE Sepharose FF and Sephacryl S-100 were from Pharmacia. Sequenase and the Sequenase version 2.0 sequencing kits were from U.S. Biochemical Corporation. AmpliTaq was from Perkin-Elmer Cetus. pBluescript SK was from Stratagene.

General methods for DNA manipulations.

DNA fragments amplified by PCR were routinely purified by Wizard PCR Preps (Promega) and plasmid Wizard Miniprep (Promega). DNA fragment isolations were achieved after separation by agarose gel electrophoresis using Tris acetate buffer, visualization using ethidium bromide staining with long-wavelength illumination, and recovery using the Gene Clean Kit from Bio 101. Oligonucleotides were synthesized at the Laboratory for Macromolecular Structure (Purdue University) and purified by urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) before use (1). Automated DNA sequence analysis was performed on a Pharmacia ALF Express at the Purdue DNA Sequencing Facility. Amino acid sequence alignments were performed using the default parameters of the CLUSTAL W, MSASHADE, and FASTA programs provided by the Biology Workbench web site of the University of Illinois National Center for Supercomputing Applications.

Strains and media.

The E. coli strains used during the course of this work are listed in Table 1. For recombinant DNA steps, DH5α was commonly used for transformation and amplification of plasmids after the appropriate antibiotic selection. Typically, 3-ml overnight cultures were used for rapid plasmid preparations to identify candidate recombinant plasmids by restriction mapping and DNA sequence analysis. Minimal and Luria-Bertani (LB) media were prepared as previously described (27), with agar added for solid media to a final concentration of 1.5% (wt/vol). The ammonium concentration in minimal medium is approximately 18 mM, as is the chloride salt concentration. Ammonium-enriched medium had the same components as minimal medium, except the nitrogen source was 50 mM ammonium sulfate (100 mM ammonium ion). Glutamine-enriched medium had the same composition as minimal medium, except that l-glutamine was provided as the sole nitrogen source at a final concentration of 5 mM. Liquid media were prepared in the same manner without the addition of agar. All solid and liquid media contained ampicillin for selection at a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 relA1 thi-1 | E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University) | |

| FB1 | Δ(hisGDCBHAFIE)750 gnd rhaA | C. Bruni (University of Naples) | 4 |

| FB182 | hisF892 | C. Bruni (University of Naples) | 4 |

| FB182 recA− | hisF892 recA1 | V. J. Davisson (Purdue University) | |

| UTH1767 | hisH1767 malA1 (λr) xyl-5 rpsL145 λ− F− | E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University) | 9 |

Construction of phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI).

The plasmid construct phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) was prepared for the coexpression of the hisH and hisF genes under regulation of a common tac promoter. Expression vectors for both hisH (phisH-tac) and hisF (phisF-tac) were previously constructed in the parent vector pJF119EH (11), a multicopy tac expression vector derived from the commercial vector pKK223-3 (7). The BamHI site immediately downstream of hisF in plasmid phisF-tac was eliminated by digestion with BamHI, treatment with Klenow to remove the four base overhangs, and religation to create phisF-tac (ΔBamHI). A three-part ligation of DNA fragments was used to construct phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI). The vector fragment was derived from BamHI- and HindIII-digested phisH-tac; the second DNA fragment encoding hisF was isolated as an NdeI-HindIII fragment from phisF-tac (ΔBamHI). A double-stranded, phosphorylated linker with BamHI and NdeI overhangs was prepared from oligonucleotides 9F and 10F (Table 2) to recreate the native 15-bp upstream region of E. coli hisF with a single base change as the final component. DNA sequencing analysis of the insert DNA showed that only one copy of the linker had been incorporated. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE analysis of extracts from IPTG-induced E. coli FB1 cells and IGP synthase activity assays of cell extracts demonstrated the overproduction of HisH and HisF at approximately equivalent levels.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| M13-20 | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | Sense primer for hisF PCR |

| 819B | CGTACCCGGGTTAACATATCCTGATCTCCA | Antisense primer for hisF PCR |

| 820B | AGGAATTCATATGCTGGCAAAACGCATAAT | Sense primer for hisF PCR |

| 58C | AACCGCCTGTTTCAGGGGA | Sense primer for hisF mutagenesis |

| 9F | GATCCGAAGGAGGCCATCA | hisF 5′ untranslated region (sense strand) |

| 10F | TATGATGGCCTCCTTCG | hisF 5′ untranslated region (antisense strand) |

| 909F | TGATCCAAGCTTGCATGCC | Antisense primer for hisF mutagenesis |

| 365I | GATCGCTTTGGCGTGCAG(C.G.T)C(C.G)ATTGTGGTC | Sense primer for C124A,-S,-P mutagenesis |

| 366I | CACGCCAAAGCGATCGGC | Antisense hisF primer |

| 1505I | GATCGCTTTGGCGTG(A.G)(A.C.T)TTGTATTGTGGTC | Sense primer for Q123A,-D,-I,-N,-T,-V mutagenesis |

| 97-31 | GCTGACGCCCTGGTG | Sense primer for E46A mutagenesis |

| 97-32 | CACCAGGGCGTCAGC | Antisense primer for E46A mutagenesis |

| 97-45 | AGGAATTCATATGCTGGCAAAAGCGAT | Sense primer for R5A mutagenesis |

All oligonucleotides are written in 5′ to 3′ orientation. Sites of mutation are underlined where appropriate. Positions of degeneracy are enclosed in parentheses.

Mutagenic PCR of the hisF gene.

Conditions for error-prone PCR were those described by Leung et al. (17), except that 1× PCR buffer consisted of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM KCl. Plasmid phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) was linearized by digestion with EcoRI and served as template in the PCR. The sense primer 58C annealed to bases 378 to 396 of the hisH gene, and the antisense primer 909F annealed to the multicloning site downstream of hisF. Four independent PCRs were performed with each nucleotide serving as the limiting base. Conditions for the mutagenic amplification were found to occur best when the first cycle was performed manually. The reactions were incubated at 100°C for 4 min and 37°C for 1 min prior to the addition of 5 U of AmpliTaq and 100 μl of light mineral oil, followed by synthesis at 68°C for 4 min. The remaining 24 cycles were performed on an MJ Research thermocycler using 94°C for 2 min, 37°C for 1 min, and 70°C for 4 min and a final extension step at 70°C for 10 min.

Cloning and phenotypic selection of hisF mutants.

The 1.08-kb PCR product consisted of the last 213 bp of hisH, followed by the 15-bp region upstream and the 780-bp hisF gene. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the amplified DNA containing the intergenic region and hisF was digested with HindIII and BamHI and was purified. The native hisF gene was removed from phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) by HindIII-BamHI digestion, and the large vector fragment was isolated following alkaline phosphatase treatment. Mutagenized hisF fragments were ligated with the recovered vector fragment. Control ligations revealed that background colonies resulting from uncut or self-ligated phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) never represented more than 5% of the total number of colonies.

The initial transformants were selected by ampicillin resistance (75 μg ml−1) and were pooled in 2 ml of LB medium. Purified plasmid DNA was used to transform E. coli FB182 recA mutant cells, and the colonies grown on LB master plates were replica plated onto minimal medium to select against nonmutagenized transformants. This step was necessary because preliminary growth studies indicated that cells growing on ammonium medium took 3 days to form colonies. Without this step, it was possible that petri dishes would have been overgrown by wild-type colonies. The colonies unable to grow overnight on minimal media were potential mutants of interest; the corresponding colonies on the master plates were patched onto minimal, ammonium, glutamine, and LB plates. Colonies that did not grow on glutamine were rescued by growth on ammonium-enriched media as a sole nitrogen source.

Site-directed mutagenesis of hisF E46A.

Mutation of glutamate 46 to alanine was performed by two rounds of PCR (15). In the first round, the hisF coding region in pKS-hisF (11) was amplified as two fragments, each containing the mutation; primers M13-20 and 97-32 were used to amplify the 5′ end. Primers 97–31 and 819B were used to amplify the 3′ region. One microliter of each gel-purified reaction and 50 pmol of primers M13-20 and 819B were used in a second PCR to reassemble the intact gene. The final PCR product was purified and cloned into pBluescript SK as an EcoRI and XmaI fragment. E46A mutants were selected and analyzed by DNA sequencing of the entire hisF coding region. The E46A hisF allele was released from pBluescript SK at the EcoRI and XmaI sites and was cloned into the tac expression vector pJF119EH.

Q123A and C124A.

These mutations were generated in two rounds of PCR as described above for the E46A mutant. Primers 820B and 366I were used to amplify the 5′ portion of hisF. In two separate reactions, degenerate primers 365I and 1505I were paired with primer 819B in order to amplify the 3′ portion of the gene and introduce mutations at C124 and Q123, respectively. The reaction products from amplification of the 5′ and 3′ regions were combined in a second round of PCR to assemble the intact hisF gene. PCR products were cloned as above, and derivatives containing Q123A or C124A were selected by DNA sequencing of the entire hisF coding regions.

R5A.

Since the arginine at position 5 is located near the 5′ end of the hisF gene, only one PCR was needed to prepare this mutant. PCR conditions were maintained as described above, using primers 97–45 and 819B. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI-XmaI and was ligated with pBluescript for DNA sequence analysis.

Overexpression and purification of hisF alleles.

In order to express mutant hisF genes independent of hisH, the mutant hisF alleles were isolated from the phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) as NdeI-HindIII fragments. The 5.3-kb vector fragment from phisF-tac was isolated after sequential HindIII digestion and limited NdeI digestion, since a second site exists in this vector. The mutant hisF alleles were ligated with the recovered vector fragment, and the recombinants were screened by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis.

Induction of gene expression from tac promoter expression vectors in E. coli FB1 was performed as described previously (11). All hisF alleles were overexpressed to the same extent as wild-type protein and displayed molecular masses similar to that of the wild-type protein, as shown by visualization of Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE. The purifications of mutant HisF enzymes were accomplished by the same protocol used for the wild-type protein. Enzyme assays to monitor the HisF purifications used the consumption of PRFAR and ammonium chloride as substrates (11). The mutant proteins displayed properties identical with those of wild-type HisF during all steps of the purification and were recovered in an ∼50% yield with >95% purity, as judged by SDS-PAGE. To prepare IGP synthase, HisH and HisF mutants were mixed at a 1.5:1 molar ratio and incubated on ice for 30 min before gel filtration chromatography using Sephacryl S-100 as previously described (11). In all cases for mutant HisF, this step confirmed the formation of the holoenzyme.

Liquid growth studies of alanine mutants.

FB182 recA mutant cells were transformed with phisHF-tac (ΔBamHI) derivatives carrying the hisF allele of interest. Overnight cultures grown in LB medium were pelleted and washed once with minimal medium before final resuspension in 1 ml of minimal medium. One-percent inocula were introduced into 25 ml minimal, ammonium, or glutamine media and were incubated at 37°C. Optical densities at 550 nm of these cultures were monitored over 4 days, and the doubling times were calculated from the period of exponential growth using log plots of optical density as a function of time.

Enzyme assay for PRFAR turnover.

Enzyme assays for monitoring the consumption of PRFAR using glutamine or ammonium chloride are briefly described and were based on a previous protocol (11). In this assay, a decrease in absorbance at 300 nm was used to follow the transformation of PRFAR to IGP and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl 5′-monophosphate (AICAR) (Fig. 1) that is catalyzed by IGP synthase (or HisF) in the presence of glutamine (or ammonia) at pH 8.0. The substrate PRFAR was generated in situ from N1-[(5′-phosphoribosyl)formimino]-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (5′-ProFAR) during a preincubation period with the HisA enzyme. Assays with ammonium chloride (40 to 400 mM) contained 20 nM IGP synthase mutant and 100 μM PRFAR; the increasing amount of chloride ion in this concentration range did not adversely effect enzyme activity. For determination of the IGP synthase kinetic constants, PRFAR concentrations were varied between 5 and 100 μM and ammonium chloride was held constant at 400 mM. The glutamine-dependent assay for most of the mutant enzymes was modified to account for the slower turnover rates by using 4.4 μM enzyme and up to 100 mM glutamine with PRFAR at 100 μM. Mutant R5H(HisF) IGP synthase was assayed using 2 μM enzyme and a glutamine concentration range of 0.5 to 5 mM. At high glutamine concentrations (100 mM), significant amounts of contaminating ammonium were detected in the assay, even after repeated recrystallization of glutamine. Control assays designed to measure this ammonium-dependent background rate were initiated with a concentration of mutant HisF equimolar to that of the corresponding IGP synthase derivative. Under these conditions, any consumption of PRFAR was attributed to ammonium-based catalysis by HisF and not to glutamine-based turnover by the IGP synthase derivative. All data were collected continuously for the first 2 min on a Varian Cary 3 spectrophotometer with temperature regulation at 30°C. The kinetic constants for the IGP synthase activities (Km and Vmax) were estimated from direct nonlinear fits to the equation v = Vmax[S]/(Km + [S]) using Kalidegraph (Synergy Software) or the Enzyme Kinetics program (Trinity Software).

Glutaminase assays.

Enzyme and substrate concentrations in the glutaminase assays for IGP synthases assembled using HisF mutants had to be modified from the conditions used to measure the wild-type activity (11). For the mutant enzymes, the following conditions were used: in a 1-ml volume were combined 4.4 μM IGP synthase derivative, 5 to 100 mM glutamine, and 2 mM 5′-ProFAR (when appropriate) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 30°C. Further alterations to the assay were required for IGP synthase made from the R5H subunit. In the presence of glutamine alone, 3.4 μM enzyme was used and the assay was performed as described above. In the presence of 2 mM 5′-ProFAR, 0.2 μM enzyme was used in a total reaction volume of 0.5 ml and the glutamine concentration range was 1 to 10 mM. The effect of PRFAR upon glutaminase activity of the R5H mutant was also assessed. In this case, 100 μM PRFAR was included as effector, and 0.1 μM enzyme was used to initiate the assay in a 0.5-ml volume with 1 to 10 mM glutamine.

Two-hundred-microliter aliquots were collected at 30, 60, 120, and 180 min for glutamate quantitation (20). When glutaminase assays were performed with the R5H mutant and effector molecules, 50-μl samples were collected at 6-min intervals over 40 min (with 5′-ProFAR) or at 3-min intervals over 20 min (with PRFAR). From these data, a rate was estimated using a standard curve generated daily and corrected by the appropriate dilution factor. Steady-state kinetic constants were estimated using fits to the nonlinear forms of the Michaelis-Menten equation as described for the IGP synthase activity.

Estimate of subunit dissociation.

Subunit titrations to determine stoichiometry of the enzyme complex were previously described (11). In those experiments, a constant amount of HisF (1.2 μM) or HisH (0.35 μM) was titrated with increasing amounts of the other subunit. After incubation on ice for 30 min, aliquots were taken for the enzyme assay. Formation of the holo-IGP synthase resulting from titration with the added subunit was assumed to be reflected by an increase in specific activity. These data were used to estimate an upper limit for a dissociation constant in the IGP synthase complex from values at a 1:1 subunit molar ratio. In the case of the HisF titration with HisH, the specific activity was ∼90% of the maximum and Kd, 0.013 μM, was calculated as follows: [(free HisF)(free HisH)]/(HisHF complex) = [1.2 μM − (0.90)(1.2 μM)]2/(0.90)(1.2 μM). When HisH was titrated by HisF, 82% of the maximal specific activity was observed and Kd was 0.014 μM. Alternatively, the data for the HisF titration with HisH was fitted to the quadratic equation using Graphfit 2.0 with robust statistical weighting to arrive at a Kd of 0.019 ± 0.009 μM.

RESULTS

Rationale.

The HisH glutamine binding domain of IGP synthase does not exhibit glutaminase activity in the absence of the HisF subunit. The requirement for association with the acceptor domain in order to hydrolyze glutamine has been termed conditional glutaminase activity (25). In spite of its lack of catalytic activity, the HisH can bind and be covalently modified by glutamine affinity analogs, albeit at highly reduced rates when compared to the holoenzyme IGP synthase (S. V. Chittur, T. J. Klem, C. M. Shafer, and V. J. Davisson, submitted for publication). Two scenarios can be envisaged to explain the conditional glutaminase activity of the HisH subunit. The first involves a direct role for HisF in providing the catalytic residues necessary for glutaminase specificity and/or turnover. Alternatively, nucleotide binding to HisF may induce a global conformational change in HisH that properly orients the catalytic residues for glutaminase activity. Any scenario would involve some regulatory feature for HisF in HisH function. An experimental approach was pursued to test if specific HisF residues are required for glutamine hydrolysis and/or ammonia transfer in IGP synthase.

Mutant screen.

A biochemical screen was designed to isolate hisF mutants that retain their functional capacity to catalyze the ammonia-dependent synthase reaction but render IGP synthase incompetent for the amidotransfer reaction with glutamine. The initial assumption was that the hisH mutant E. coli would not grow on a defined medium containing glutamine as a sole nitrogen source (26). Point mutations in hisF that impair IGP synthase glutamine-dependent amidotransferase were also not expected to confer growth on media containing glutamine. However, studies of the biochemical properties of the HisF protein indicated that under artificially high ammonia concentrations, IGP production is possible, offering a unique selection strategy for catalytic function in vivo by growing cells on ammonium-enriched minimal medium (Fig. 1, reaction B).

Bacterial growth studies with hisH and hisF mutant strains confirmed these assumptions. E. coli strain FB182 (hisF mutant) was unable to grow on minimal media regardless of the nitrogen source. The possibility that a “leaky” hisF mutation could be complemented by overproduction of HisH was eliminated, since this strain did not grow when transformed with phisH-tac. E. coli strain UTH1767 (hisH mutant) was able only to form small colonies on ammonium-enriched medium, consistent with the 1,000-fold-greater Km that HisF and IGP synthase display for ammonium as a substrate than for glutamine (11). When UTH1767 (hisH mutant) was transformed with phisF-tac, the strain grew on minimal medium and exhibited enhanced growth (larger colonies) on ammonium-enriched medium. These observations were consistent with histidine biosynthesis as the limiting factor in cell growth that could be alleviated by overproducing HisF with ammonium as the sole nitrogen source. The recombinant system was designed to provide an equimolar amount of both HisH and HisF in vivo since both are required for glutamine-dependent histidine biosynthesis. Isolation of the desired mutants was predicated upon the ability to introduce a heterogeneous population of hisF genes into E. coli FB182 (hisF mutant) and select for transformants that could grow on ammonium-enriched medium but not on glutamine medium.

Random mutagenesis.

In the case of IGP synthase, the heterodimeric nature of the enzyme made it possible to mutagenize the acceptor subunit without affecting the glutamine binding subunit. To date, the residues identified as required for glutamine utilization in related amidotransferases have all been found on the glutamine binding subunit (10, 18). Therefore, it was desirable to only mutagenize hisF and eliminate the possibility of isolating glutamine-deficient hisH mutants.

Random PCR mutagenesis (17) was chosen for these experiments because it was expedient and promised some degree of mutational diversity throughout the length of the hisF gene. The expected frequency of mutation using the PCR protocol is 2% at reduced dATP and magnesium chloride concentrations (7, 17). Five independent PCRs were screened from an average library of 6,000 transformants per experiment. In total, 14 colonies exhibited the desired phenotype of poor or no growth on glutamine and minimal media but were rescued on ammonium-enriched medium. Plasmid DNA was isolated from these 14 independent clones, and the hisF genes were sequenced (Table 3). These data indicate that despite the choice of limiting nucleotide and buffer composition, transition mutations were favored as predicted from previous investigation (3).

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide and amino acid changes of the hisF mutants isolated via random PCR mutagenesis and genetic selection

| Limiting nucleotide | Mutation | Nucleotide change |

|---|---|---|

| dATP | E46G | A→G |

| dATP | E46K | G→A |

| dATP | E46G, I7V | A→G (E46G) |

| A→G (I7V) | ||

| dATP | C124R | T→C |

| dATP | C124R, M179I | T→C (C124R) |

| G→C (M179I) | ||

| dATP | Q123R, I75V | A→G (Q123R) |

| A→G (I75V) | ||

| dCTP | C124R | T→C |

| dCTP | C124R | T→C |

| dCTP | C124Y, I100V | G→A (C124Y) |

| A→G (I100V) | ||

| dCTP | P203L, G208D | C→T (P203L) |

| G→A (G280D) | ||

| dGTP | R5H | G→A |

| dGTP | G20S | G→A |

| dGTP | G81S | G→A |

| dTTP | Q123R | A→G |

The consistent isolation of mutations at E46, Q123, and C124 (10 out of the 14) suggested that these residues play roles in the glutamine-dependent reaction. The same mutations were isolated from libraries derived in different PCR products. Secondary mutations were considered to be phenotypically benign and random by-products of the PCR since they were never independently isolated. Single mutants at R5, G20, and G81 and one double mutant, P203/G208, were also isolated. All of these sites reside in highly conserved regions of the HisF protein. The phenotype initially observed on solid media was confirmed by growth in liquid media, except for the two glycine mutants which were unable to grow in ammonium-enriched liquid medium. On the basis of the glutamine-deficient phenotype on both solid and liquid media, and the fact that the mutations all lie in highly conserved regions, E46G, Q123R, C124R, and R5H single mutants were selected for more detailed biochemical and kinetic analyses.

IGP synthase formation using hisF alleles.

One explanation for the glutamine-deficient phenotype would be that the mutations in HisF prevent association with HisH and minimize formation of the holoenzyme. Similar mutants have been isolated from the heterodimeric GAT aminodeoxychorismate synthase (24). Mutation of the pabB acceptor domain gene led to the isolation of point mutants that could aminate chorismate from ammonium but were unable to associate with the glutamine binding domain. Several lines of evidence are not consistent with this explanation for the HisF mutants. The estimated Kd for subunit association based upon our previous characterization of native IGP synthase is ≤10−8 M, indicative of a highly associated complex (11). Each of the purified alleles formed IGP synthase under the same gel filtration conditions used to assemble the native enzyme (11). In addition, the holoenzymes with mutant HisF alleles were observed by protein cross-linking studies with HisH (data not shown) under the same conditions used for the wild-type enzyme (11). The isolated subunits have been previously shown to denature within 24 h at ambient temperature, while the holoenzyme retains full activity. Therefore, the stability of the complexes formed with HisH also established the absence of any global structural effects from HisF point mutations that would minimize the subunit associations in IGP synthase.

Steady-state kinetic analyses.

The isolated IGP synthase bearing the HisF mutant subunits showed minimal alterations in their catalytic properties with respect to the nucleotide substrate PRFAR or ammonium chloride. In Table 4 are the apparent steady-state kinetic constants for PRFAR and ammonium chloride, which show that Km and kcat values are similar to those for native IGP synthase. The isolation of mutant holoenzymes that retain IGP synthase activity validates the phenotypic screen.

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters for mutant HisF alleles of E. coli IGP synthasesc

| HisF subunit | Km, PRFAR (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | Km, NH4+ (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | Km, Gln (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km(M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild typea | 28.1 ± 3.0 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 3.0 × 105 | 17.0 ± 1.3b | 8.8 ± 0.3b | 518b | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 3.7 × 104 |

| Q123R | 17.5 ± 3.2 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 3.0 × 105 | 13.4 ± 3.1 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 425 | ND | ND | ND |

| C124R | 21.8 ± 4.0 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 2.4 × 105 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 581 | ND | ND | ND |

| E46G | 12.5 ± 3.0 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.0 × 105 | 11.2 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 392 | 14.5 ± 1.0 | 0.19 ± 0.008 | 13 |

| R5H | 42.6 ± 5.1 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 × 105 | 14.3 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 399 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 0.13 ± 0.1 | 24 |

These kinetic parameters for wild-type IGP synthase were taken from reference 11. ND indicates that the activity was below the detection limit of this assay.

These concentrations are corrected for the concentration of dissolved ammonia at pH 8.0.

For the first three columns of values, PRFAR was the varied substrate and the concentration of NH4Cl was constant at 400 mM. For the second three columns, NH4Cl was the varied substrate and the concentration of PRFAR was constant at 100 μM. For the third three columns, Gln was the varied substrate and the concentration of PRFAR was constant at 100 μM.

Glutamine-dependent assays with IGP synthases assembled from the mutant HisF subunits were conducted to define the biochemical basis for the observed in vivo phenotype. Despite the lack of glutamine-dependent functional properties in vivo, the enzymes assembled from the E46G and R5H subunits retained a limited ability to turn over PRFAR with glutamine as the nitrogen donor (Table 4). Steady-state kinetic analyses of the reactions revealed that both kcat and Km were severely impaired, with the net results showing a 2,800-fold reduction in the kcat/Km ratio for glutamine. In contrast, IGP synthases formed with Q123R or C124R had no measurable activity with glutamine in vitro, even with excessive concentrations of protein or amino acid. Based on background rates in the absence of enzyme, these mutant forms have kcat values that are >106 times slower than the native enzyme.

Glutaminase activity.

The HisF point mutations affecting glutamine utilization by IGP synthase could be reflected in the glutamine amide hydrolysis reaction or in the subunit interactions required for transfer of the ammonia equivalent. Since these mutations are not expected to impact the catalytic triad for hydrolysis in HisH (11, 29, 32), the mutant enzymes were classified by their glutaminase properties. A glutaminase with reduced catalytic efficiency would implicate a defect in the active site beyond the catalytic triad residues. Mutant IGP synthases that displayed glutaminase properties similar to those of the wild type would implicate an alteration of the functional residues required for complete amide transfer beyond the hydrolytic step. Mechanistic indicators for glutaminase regulation are the enhanced kinetic properties when the substrate analog 5′-ProFAR binds the HisF subunit (11). Using these criteria for comparison, IGP synthases with the HisF mutant subunits were classified into three distinct subclasses.

The steady-state kinetic constants for the glutaminase activity of each mutant IGP synthase are shown in Table 5. IGP synthase holoenzymes formed from the neighboring Q123R and C124R alleles showed a large reduction in glutaminase activity, although they were clearly above background levels and showed saturation kinetics. The effects on the kcat/Km ratio were reflected in both parameters, and no stimulation was observed with 5′-ProFAR. Therefore, the essential regulatory features on HisF that modulate the rate of HisH glutamine hydrolysis through nucleotide binding were absent in these mutant enzymes.

TABLE 5.

Glutaminase activity of native and mutant IGP synthase holoenzymesc

| HisF subunit | Km, Gln (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | Fold stimulation (kcat/Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild typea | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 0.07 | 14 | |

| Wild type (+5′-ProFAR) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 | 910 | 65 |

| Q123R | 10.0 ± 2.7 | 0.001 | 0.10 | |

| Q123R (+5′-ProFAR) | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.17 | None |

| C124R | 30 ± 7.4 | 0.0008 | 0.03 | |

| C124R (+5′-ProFAR) | 32 ± 16 | 0.0008 | 0.03 | None |

| E46G | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 0.003 | 0.3 | |

| E46G (+5′-ProFAR) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.071 | 52 | 173 |

| R5H | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 0.01 | 3.8 | |

| R5H (+5′-ProFAR) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 11.6 | 4,461 | 1,170 |

| R5H (+PRFAR)b | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 17.0 | 9,800 | 2,580 |

Kinetic parameters for wild-type IGP synthase were taken from reference 11.

These values are not corrected for the percentage of amidotransferase activity, which is ≈20%.

IGP synthase enzymes consisted of HisH and wild-type or mutant HisF alleles, as described in Materials and Methods.

Both the R5H and E46G mutants were expected to exhibit glutaminase activity because they could support the complete ammonia transfer reaction with glutamine as the nitrogen source. The results with E46G(HisF) IGP synthase showed a reduced glutaminase that could be stimulated 170-fold in the presence of 5′-ProFAR, but the turnover for this enzyme was still 30-fold less than that for the wild-type IGP synthase.

The most striking results were the glutaminase properties displayed by R5H(HisF) IGP synthase. The kinetic parameters for basal glutaminase activity were similar to those for the wild-type enzyme. However, in the presence of 5′-ProFAR, the kcat/Km value was fivefold greater than the corresponding value for the wild-type enzyme. The glutaminase turnover in the presence of the nucleotide substrate PRFAR was also elevated to a level comparable to kcat for the wild-type amidotransferase. This characteristic contrasts with the dramatic reduction in the amidotransferase activity observed for this R5H mutant enzyme (Table 4). These kinetic data establish that the glutaminase function is uncoupled from the amidotransferase. The glutaminase stimulation by PRFAR on this enzyme is primarily on kcat, and the nitrogen transfer has been disrupted by this single mutation. Thus, R5H(HisF) IGP synthase represents a unique GAT mutant in which the normal mechanistic controls relating 1:1 stoichiometry between glutamine hydrolysis and amidotransfer have been bypassed.

Essential character of conserved regions.

Alanine derivatives for each of the four HisF mutants were constructed to qualitatively evaluate the importance of the conserved amino acids and to provide controls for the mutations isolated in the random mutagenesis protocol. Alanine replacements were employed to assess if the chemical characteristics for the side chains provided an essential function for glutamine dependence in IGP synthase.

The growth characteristics for the R5A, E46A, Q123A, and C124A HisF derivatives were determined in minimal, ammonium-enriched, or glutamine-enriched liquid media (data not shown) using the same expression constructs in a hisF mutant E. coli strain. After a lag period, the C124A mutant grew equally well on all three types of media with doubling times (1.5 h) comparable to those for the strain transformed with the wild-type hisF expression construct. In contrast, the Q123A mutant grew at different rates on these media with glutamine being the slowest and intermediate on the ammonia-enriched media. The ability of these transformed cells to grow on all media eliminates Q123 or C124 as candidates for essential roles in the ammonia transfer process.

The R5A and E46A HisF substitutions had profound effects upon the growth characteristics in all three media. Neither of these transformed strains grew in the glutamine medium, but their rescue occurred by slow growth in ammonium-enriched medium. Even under ammonium-enriched conditions, the stationary culture densities were only 50% of the transformed strain containing the wild-type hisF expression vector. These results are also consistent with the kinetic characteristics of the glutamine turnover displayed by the E46G and R5H mutants isolated by random mutagenesis (Tables 4 and 5). In total, the HisF E46 and R5 residues are candidates for essential roles in the ammonium transfer process catalyzed by IGP synthase.

DISCUSSION

The object of this research was to develop an approach for identifying residues in the acceptor domain of E. coli IGP synthase that are involved in the glutamine-dependent conversion of PRFAR to IGP. The impetus for this work was provided by biochemical and structural evidence implicating roles for GAT acceptor domains during the modulation of the ammonia transfer (19, 25, 29, 31, 33). Our initial characterization of IGP synthase established that the HisH glutamine binding subunit is devoid of glutaminase activity in the absence of the HisF acceptor subunit (11). The glutaminase property of IGP synthase is similar to many other GATs because the binding of a substrate analog or product at the synthase active site stimulates it. In the case of IGP synthase, this property implicates a role for the HisF subunit in modulating the glutamine site on HisH.

Concurrent with our studies, the three-dimensional crystal structures of the triad GATs, 5′-guanosine monophosphate (GMP) synthetase, carbamoyl phosphate (CP) synthetase, and anthranilate synthase were reported (12, 29, 30). These structures have several remarkable features, including a similar topology for the glutamine binding domains and their catalytic sites. Two acceptor domains have structural relationships with other metabolic enzymes, while the third has a unique fold. These modular features of triad GATs are consistent with an evolutionary process where the glutamine and acceptor domains have distinct origins. As a consequence, it is expected that communication between the modular domains will have been specifically optimized for efficient ammonia transfer by each GAT.

Other key features of the GAT structures are the architectures employed to facilitate passage of ammonia between the active sites. In CP synthetase, an elaborate channel is proposed to guide ammonia transfer between active sites of the two domains (23, 30). Another channel has been proposed for ammonia transfer in an active conformation of the Ntn GAT PRPP amidotransferase that contains substrate analogs of glutamine and PRPP (13). An allosteric loop in PRPP amidotransferase closes over the separated active sites, minimizing the solvent exposure and creating a conduit for ammonia transfer (5). In the TrpE subunit of anthranilate synthase, a substrate-dependent conformational change is postulated to also trigger the formation of a channel between active sites (12).

Our results support the essential role for specific residues on the HisF (or acceptor domain) of IGP synthase in both the modulation of the glutaminase and in the ammonium transfer steps. The mutant selection strategy used in this study offers a complementary approach that will play a role in identifying some molecular details of the ammonia transfer process. In this case, low levels of glutamine-dependent IGP synthase activity were found to not sustain the level of histidine biosynthesis required for growth. Random mutations in the IGP synthase HisF subunit were selected by the loss of glutamine-dependent turnover while maintaining their catalytic integrity for nucleotide turnover with ammonia. As shown in the present study, the inability to support growth in vivo is a consequence of a 3,000-fold reduction of the kcat/Km ratio for glutamine as compared to that for wild-type IGP synthase. The PCR mutagenic protocol yields mostly transition events, and too few colonies were screened in this study to be considered exhaustive; however, the selection of glutamine-deficient mutants proved to be stringent.

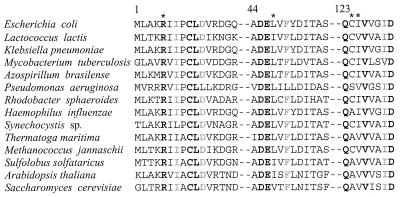

The most profound discovery from this selection strategy is the class of mutations defined by substitutions at the completely conserved R5 (Fig. 2). This arginine is a candidate for an essential residue in the ammonia transfer step. The two half-reactions (glutaminase and ammonia-dependent synthase) are not dependent upon R5 even though the overall glutamine-dependent amidotransferase activity is clearly influenced by mutations at this position. Most surprising is the high degree of glutaminase efficiency displayed by this mutant. The efficient coupling that produces transfer of the ammonia equivalent between the glutamine and synthase active sites is nearly abolished by the substitution at position 5. The relative kcat/Km values indicate a 100:1 stoichiometry for glutamine hydrolysis to IGP synthesis. A mutant in a GAT acceptor domain that uncouples the half-reactions and maintains catalytic efficiency has not been previously identified in any protein. However, an engineered mutant in the CP synthase glutaminase subunit was designed as a block of the ammonia channel and shows an uncoupling of the ammonia transfer reaction (10). If the structural paradigm of a channel for ammonia transfer is common to all the GATs, the functional mutations represented by the HisF R5H are likely to be more general than the exception.

FIG. 2.

Primary amino acid sequence alignments of selected regions of representative HisF sequences. The residues in bold are completely conserved, and those marked with ∗ are sites of mutations that were selected in the glutamine-dependent screen.

Glutamate 46 is conserved in all known HisF sequences (Fig. 2), and three amino acid substitutions of this residue resulted in the same glutamine-deficient phenotype. The current data implicate E46 in a role that directly impacts the catalytic turnover of the glutamine hydrolysis reaction. However, the effect of nucleotide binding on the glutaminase is preserved. Since the catalytic triad of HisH is present in IGP synthase, a role for HisF E46 could be in the specific binding of the substrate glutamine. Other indirect evidence for HisF contributions to substrate specificity relates to the reduction of Km for glutamine (11) and to the increased specificity for glutamine affinity analogs imparted by the binding of the substrate PRFAR (Chittur et al., submitted). Mutants in other GAT acceptor domains that impact only glutamine utilization in a similar manner have not been previously identified. In CP synthetase, an E841K mutant on the acceptor subunit prevented glutamine utilization, but it also could not catalyze ammonia-dependent CP synthesis and the structural evidence does not support a direct role of this residue in glutamine turnover (18, 30).

The recent X-ray crystal structure of the HisF subunit from Thermatoga maritima became available during the final review of this paper (16). This protein is a member of the alpha/beta barrel folding motif, and the E46 and R5 residues are located on one face of the barrel with their side chains oriented toward the center of the protein. These E46 and R5 residues are within 3 Å of each other and likely form an ionic bridge. Even more intriguing, they are farther than 10 Å from the nucleotide substrate-binding site. The functional differences imparted by the specific mutations at each position highlight the challenge of understanding their involvement in the ammonia transfer step. The mutations presented here will serve to guide future work on the details of the role of these residues in the ammonia transfer process.

The mutations isolated with the highest frequency were in the sequential codons for Q123 and C124. The high degree of HisF amino acid sequence conservation in the region containing Q123 and C124 (Fig. 2) implicates a functional role. The bulky arginine side chain substitution at these positions shows identical impacts on glutmaine-dependent catalytic activities. However, the alanine mutations at these positions show that they are nonessential to the glutamine-dependent IGP synthase activity. These residues are located on the surface of the alpha/beta barrel in close proximity to the R5 and E46 residues with the side chains oriented toward the solvent (16). The arrangement of the amino acids further supports the hypothesis that this face of the HisF protein is critical to HisH glutaminase function and the ammonia transfer process. Unfortunately, the current structural data do not include the HisH domain, and further biochemical work will be required to ascertain the exact role of these residues.

The results observed from our mutational studies are consistent with the hypothesis that residues from both subunits (or domains) in GATs must coordinate the glutamine hydrolysis and ammonia transfer processes. It is logical that these events are temporally controlled so that when the acceptor site is occupied with an activated substrate, the enzyme specificity is enhanced (21). The modular evolutionary process proposed for the triad GATs assumes distinct origins for the glutamine and acceptor domains (33); consequently, the molecular details for the ammonia transfer event are likely different for every GAT. A comparison of these distinctions will most likely prove useful for establishing the key structure-function and mechanistic details not available from a single amidotransferase structure. The mutant selection employed in this work can operationally be extended to other GATs for identification of residues involved in glutamine utilization, and characterization of the partial catalytic activities will complement X-ray crystallography studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by a grant from the NIH RO1 GM45756 to V.J.D.

We recognize the helpful discussions with John Burgner, Howard Zalkin, and Janet Smith.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehlein S K, Richards N G, Walworth E S, Schuster S M. Arginine 30 and asparagine 74 have functional roles in the glutamine dependent activities of Escherichia coli asparagine synthetase B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26789–26795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldwell R C, Joyce G. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlomagno M S, Chiarotti L, Alfano P, Nappo A G, Bruni C B. Structure and function of the Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli K12 histidine operons. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:585–606. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Burgner J W, Krahn J M, Smith J L, Zalkin H. Tryptophan fluorescence monitors multiple conformational changes required for glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase interdomain signaling and catalysis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11659–11669. doi: 10.1021/bi991060o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chittur S V, Chen Y, Davisson V J. Expression and purification of imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;18:366–377. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckert K A, Kunke T A. High fidelity DNA synthesis by the Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3739–3744. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blöcker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrick-Silversmith L, Hartman P E. Histidine-requiring mutants of Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1970;66:231–244. doi: 10.1093/genetics/66.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Raushel F M. An engineered blockage within the ammonia tunnel of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase prevents the use of glutamine as a substrate but not ammonia. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3240–3247. doi: 10.1021/bi9926173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klem T J, Davisson V J. Imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase: the glutamine amidotransferase in histidine biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5177–5186. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knochel T, Ivens A, Hester G, Gonzalez A, Bauerle R, Wilmanns M, Kirschner K, Jansonius J. The crystal structure of anthranilate synthase from Sulfolobus solfataricus: functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9479–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krahn J M, Kim J-H, Burns M R, Parry R J, Zalkin H, Smith J L. Coupled formation of an amidotransferase interdomain ammonia channel and phosphoribosyl active site. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11061–11068. doi: 10.1021/bi9714114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuenzler M, Balmelli T, Egli C M, Paravicini G, Braus G H. Cloning, primary structure, and regulation of the HIS7 gene encoding a bifunctional glutamine amidotransferase:cyclase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5548–5558. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5548-5558.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landt O, Grunet H-P, Hahn U. A general method for the rapid site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1990;96:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90351-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang D A, Thoma R, Henn-Sax M, Sterner R, Wilmanns M. Structural evidence for evolution of the beta/alpha-barrel scaffold by gene duplication and fusion. Science. 2000;289:1546–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung D W, Chen E, Goeddell D V. A method for random mutagenesis of a defined DNA segment using a modified polymerase chain reaction. Technique. 1989;1:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lusty C J, Liao M. Substitution of Glu841 by lysine in the carbamate domain of carbamyl phosphate synthetase alters the catalytic properties of the glutaminase subunit. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1278–1284. doi: 10.1021/bi00056a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meister A. Mechanism and regulation of the glutamine-dependent carbamyl phosphate synthetase of Escherichia coli. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1989;62:315–374. doi: 10.1002/9780470123089.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messenger L J, Zalkin H. Glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase from Escherichia coli: purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3382–3392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles B W, Raushel F M. Synchronization of the three reaction centers with carbamoyl phosphate synthetase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5051–5056. doi: 10.1021/bi992772h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel N, Moyed H S, Kane J F. Properties of xanthosine 5′-monophosphate-amidotransferase from Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;178:652–661. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raushel F M, Thoden J B, Holden H M. The amidotransferase family of enzymes: molecular machines for the production and delivery of ammonia. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7891–7899. doi: 10.1021/bi990871p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rayl E A, Green J M, Nichols B P. Aminodeoxychorismate synthase: analysis of pabB mutations affecting catalysis and subunit association. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1295:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roux B, Walsh C T. p-Aminobenzoate synthesis in Escherichia coli: kinetic and mechanistic characterization of the amidotransferase PabA. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6904–6910. doi: 10.1021/bi00145a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubino S D, Nyunoya H, Lusty C J. In vivo synthesis of carbamyl phosphate from NH3 by the large subunit of Escherichia coli carbamyl phosphate synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4382–4386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith J L, Zaluzec E J, Wery J-P, Niu L, Switzer R L, Zalkin H, Satow Y. Structure of the allosteric regulatory enzyme of purine biosynthesis. Science. 1994;264:1427–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.8197456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tesmer J J G, Klem T J, Deras M L, Davisson V J, Smith J L. The crystal structure of GMP synthetase: a paradigm for two enzyme families and a novel catalytic triad. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:74–86. doi: 10.1038/nsb0196-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoden J B, Holden H M, Wesenberg G, Raushel F M, Rayment I. Structure of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: a journey of 96 Å from substrate to product. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6305–6316. doi: 10.1021/bi970503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thoden J B, Wesenberg G, Raushel F M, Holden H M. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: closure of the B-domain as a result of nucleotide binding. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2347–2357. doi: 10.1021/bi982517h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zalkin H. The amidotransferases. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1993;66:203–309. doi: 10.1002/9780470123126.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zalkin H, Smith J L. Enzymes utilizing glutamine as an amide donor. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1998;72:87–144. doi: 10.1002/9780470123188.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zalkin H, Truitt C D. Characterization of the glutamine site of Escherichia coli guanosine 5′-monophosphate synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5431–5436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]