Abstract

Bacteria with circular chromosomes have evolved systems that ensure multimeric chromosomes, formed by homologous recombination between sister chromosomes during DNA replication, are resolved to monomers prior to cell division. The chromosome dimer resolution process in Escherichia coli is mediated by two tyrosine family site-specific recombinases, XerC and XerD, and requires septal localization of the division protein FtsK. The Xer recombinases act near the terminus of chromosome replication at a site known as dif (Ecdif). In Bacillus subtilis the RipX and CodV site-specific recombinases have been implicated in an analogous reaction. We present here genetic and biochemical evidence that a 28-bp sequence of DNA (Bsdif), lying 6° counterclockwise from the B. subtilis terminus of replication (172°), is the site at which RipX and CodV catalyze site-specific recombination reactions required for normal chromosome partitioning. Bsdif in vivo recombination did not require the B. subtilis FtsK homologues, SpoIIIE and YtpT. We also show that the presence or absence of the B. subtilis SPβ-bacteriophage, and in particular its yopP gene product, appears to strongly modulate the extent of the partitioning defects seen in codV strains and, to a lesser extent, those seen in ripX and dif strains.

Cells with circular chromosomes and homologous recombination systems must be able to resolve chromosome dimers, or higher-order multimeric forms, that are generated by an odd number of recombination events between sister chromosomes during DNA replication. Failure to resolve chromosome dimers into monomers will prevent the proper partitioning of genomic material to newly forming daughter cells. A model for the coordination of chromosome dimer resolution and cell division has been elaborated in Escherichia coli based on a substantial accumulation of in vivo and in vitro data. In E. coli, two tyrosine family site-specific recombinases, XerC and XerD, act in concert at a site near the terminus of chromosome replication known as dif to resolve chromosome dimers into monomers during the process of cell division (9, 6, 12, 22). Deletion of Ecdif or mutations in xerC or xerD result in the development of a subpopulation of filamentous cells containing abnormally partitioned nucleoids. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the FtsK protein must be located at the constricting septum for the Xer-mediated resolution of chromosomes to occur (26, 37, 39). Similarly, plasmids containing the 28-bp minimal Ecdif site show dependence on FtsK for Xer-mediated inter- and intramolecular site-specific recombination in vivo (33). Dimeric chromosomes are thought to arise primarily as a by-product of homologous recombination events that enable bacteria to re-initiate replication at stalled replication forks. Although sister chromatid exchanges that generate dimers have been estimated to occur in approximately 15% of cells within a growing population, it is currently thought that recombinational DNA repair of stalled replication forks is a major housekeeping event in bacterial cells (38, 15).

A site-specific recombination system involved in chromosome partitioning has recently been described for the gram-positive species Bacillus subtilis (34). The B. subtilis homologues of the Xer proteins, CodV and RipX, share 35 and 44% identity with the E. coli XerC and XerD recombinases, respectively. CodV and RipX both possess the conserved amino acid residues indicative of the tyrosine family site-specific recombinases (16, 28, 34, 36). In vitro, RipX exhibited significant binding and catalytic activity on synthetic substrates containing the E. coli dif site. While CodV binding was significantly lower than that seen for RipX, cooperative interactions between the two recombinases were demonstrated (34).

Mutations in ripX resulted in the development of a subpopulation of cells that were either anucleate or contained aberrant nucleoids. The most likely interpretation of this partitioning defect is that chromosome dimers cannot be resolved in a ripX strain. Probably as secondary consequences of the partitioning failures seen in ripX mutants, cell division, competence, and sporulation deficiencies were also reported (34). The competence and sporulation defects highlight the concept that normal chromosome physiology in B. subtilis is required for successful progress through developmental pathways (20, 21, 31). Strikingly, the ripX phenotypes were not suppressed by the introduction of a recA mutation, in contrast to the case for E. coli xerC recA and dif recA double mutants (9, 34). Rather, ripX recA double mutants appeared to present a unique range of nucleoid phenotypes and a greater sporulation deficiency than that seen in either the ripX or the recA mutant.

In this study we present genetic and biochemical evidence that a Bsdif site is located at approximately 166° on the B. subtilis chromosome, 6° counterclockwise from the B. subtilis terminus of replication (23). Bsdif is utilized by the CodV and RipX recombinases to ensure that normal chromosome partitioning occurs in advance of the completion of cell division. We also show that the SPβ bacteriophage-encoded gene yopP, whose protein product shows limited homology to CodV and RipX, affects the penetration of the resolution-related phenotypes observed in codV, ripX, and dif mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The B. subtilis parental strain used in this study (except where noted) was BR151 (trpC2 lys3 metB10). Strain SL7513 (trpC2 metB10 xin-1 SPβ−), which was used to evaluate prophage contribution to the chromosome partitioning phenotypes, was obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (YB886). See Table 1 for a complete listing of all B. subtilis strains and plasmids used. E. coli strain DH5α [F− endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 λ− recA1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 φ80dlacZΔM15; Bethesda Research Laboratories] was used for cloning recombinant plasmids designed to inactivate B. subtilis genes. E. coli JC8679, a recBC sbcA derivative of AB1157 (42), was used to propagate Bsdif-containing plasmids and control plasmids used in recA integration assays. The E. coli strain used to overexpress the CodV and RipX maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusions was DS9009, a recF xerC::cat xerD::km derivative of AB1157 (34).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or constructiona |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | 1 |

| BR151 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 | Standard lab strain |

| SL992 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 recA4(E4) | BR151 × GSY908 |

| SL7131 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ripX::spc | 33 |

| SL7355 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::neo | 33 |

| SL7360 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 recA::neo | 33 |

| SL7370 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ripX::spc recA::neo | 33 |

| SL7375 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 spoIIIE::spc | 33 |

| SL7376 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ripX::cm | BR151 × pSAS8-20 |

| SL7412 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 spoIIIE::spc recA::neo | 33 |

| SL7450 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::neo::spc | SL7355 × pVK71 |

| SL7513 | trpC2 metB10 xin-1 SPβ− | YB886, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center |

| SL7519 | trpC2 metB10 xin-1 SPβ−ripX::cm | SL7513 × pSAS8-20 |

| SL7752 | trpC2 metB10 xin-1 SPβ−codV::neo | SL7513 × pSAS10-10 |

| SL7764 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::spc yomM::neo | SL7450 × pSAS53 |

| SL7765 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 yomM::neo | BR151 × pSAS53 |

| SL8081 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 yopP::spc | BR151 × pSAS82 |

| SL8101 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::neo yopP::spc | SL7355 × pSAS82 |

| SL8172 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 yopP::spc ripX::cm | SL8081 × pSAS8-20 |

| SL8271 | trpC2 codV::tet | 168 × pGB523 |

| SL8420 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 Δdif::neo | BR151 × pSAS97 |

| SL8449 | trpC2 metB10 xin-1 SPβ− Δdif::neo | SL7513 × pSAS97 |

| SL8526 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::erm | BR151 × pSAS85-8 |

| SL8540 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 yopP::spc Δdif::neo | SL8081 × pSAS97 |

| SL8541 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 codV::erm recA::neo | SL8526 × SL7360 |

| SL8562 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ytpT::spc | BR151 × pSAS118 |

| SL8576 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ytpT::spc recA::neo | SL8562 × SL7360 |

| SL8626 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 spoIIIE::spc ytpT::erm | SL7375 × pSAS120 |

| SL8629 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 spoIIIE::spc ytpT::erm recA::neo | SL8626 × SL7360 |

| SL8630 | trpC2 codV::tet recA::neo | SL8271 × SL7360 |

| SL8633 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ynfE::neo ynfF::spc | SL8638 × pSAS133-8 |

| SL8638 | trpC2 lys-3 metB10 ynfE::neo | BR151 × pSAS132-6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSAS8-20 | cat at the EcoRV site of the ripX ORFb in opposite orientation to ripX | This study |

| pSAS10-10 | neo at the NaeI site of the codV ORF; in the same orientation as codV | This study |

| pSAS53 | neo between BglII sites in yomM; in the same orientation as yomM | This study |

| pSAS82 | spc between the EcoRI sites in yopP; in the same orientation as yopP | This study |

| pSAS85-8 | erm at the NaeI site of codV ORF; in the same orientation as codV | This study |

| pSAS90-4 | Coordinates 1,940,968 to 1,942,254 in pPP390, at the SmaI site | This study |

| pSAS91-2 | 679-bp NdeI deletion of B. subtilis dif DNA in pSAS90-4 | This study |

| pSAS92-2 | 679-bp NdeI fragment containing B. subtilis dif, in pPP390 at SmaI site | This study |

| pSAS97 | Δdif by placement of neo between NdeI sites in pSAS90-4 | This study |

| pSAS101 | spc at the HindIII site of pGB140 | This study |

| pSAS103 | cat at the SphI site of pGB140 | This study |

| pSAS105 | erm at the SmaI site of pGB140 | This study |

| pSAS118 | spc between the SacII and NaeI sites of the ytpT ORF | This study |

| pSAS120 | erm between SacII and NaeI sites in ytpT ORF | This study |

| pSAS132-6 | neo at the PvuII site of the ynfE ORF | This study |

| pSAS133-8 | spc at the HincII site of the ynfF ORF | This study |

| pSAS141 | cat at PvuII site of ynfE ORF (contained in pSAS90-4) | This study |

| pSAS142 | cat at HincII site of ynfF ORF (contained in pSAS90-4) | This study |

| pSAS143 | cat at BamHI site in pSAS90-4 | This study |

| pSAS144 | cat at SmaI site of pGB140 | This study |

| pGB140 | synthetic Bsdif site between SalI and XbaI sites of pUC19 | This study |

| pGB523 | tet at the EcoRV site of the codV ORF | This study |

| pECE85 | Shuttle plasmid with cat marker | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center |

| pPP390 | erm between the EcoRI and SalI sites of pBluescript | This study |

| pVK71 | neo interrupted by spc; used to replace neo resistance with spc resistance | V. Chary |

The first strain listed in the crosses is the recipient strain used in transformations. All plasmid donor DNA was linearized by ScaI digestion prior to use in transformations.

ORF, open reading frame.

Genetic manipulations.

B. subtilis transformations were performed as described previously (44) with selection on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (Difco; 1.5%) containing chloramphenicol at 5 μg ml−1, neomycin at 12 μg ml−1, and spectinomycin at 100 μg ml−1 where appropriate. Erythromycin selection was done on LB agar containing erythromycin and lincomycin at 1 and 25 μg ml−1, respectively. Knockout mutations of ripX, recA, and spoIIIE have been described previously (34). Knockout mutations of codV, yomM, yopP, and ytpT were constructed by ligating antibiotic resistance cassettes within flanking chromosomal DNA. Antibiotic cassettes used in the construction of these knockout strains are oriented so that their transcription is in the same direction as the gene they were placed in. All knockout mutations were confirmed by PCR. Construction and purification of CodV and RipX MBP fusions was as previously described (34). The Bsdif site lies at the coordinates 1,941,798 to 1,941,825 (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList). The 28-bp Bsdif sequence was verified by sequencing reactions on both DNA strands from strains BR151 and 168 (the strain whose genome has been sequenced). The Bsdif site and flanking BR151 DNA totaling 1,286 bp (coordinates 1,940,968 to 1,942,254) was amplified by PCR using the Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into pPP390 at the SmaI site to create pSAS90-4. NdeI digestion of pSAS90-4 removed a 679-bp (coordinates 1,941,270 to 1,941,949) fragment containing the Bsdif site. A neo cassette was ligated to the NdeI ends of pSAS90-4, resulting in pSAS97. pSAS97 was then used to construct a chromosomal deletion of the dif site by transformation.

Growth conditions.

In LB medium, experimental cultures were prepared by growing strains overnight at 37°C in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics at one-half of the concentrations used in agar plates (see above for antibiotic concentrations in agar). Overnight cultures were subsequently diluted 1:20 in fresh, prewarmed medium in the absence of antibiotics. When exponential growth was achieved, cultures were diluted a second time, 1:10, in fresh, prewarmed medium. All analyses were performed after this second dilution. The second (1:10) dilution reliably yielded an exponentially growing culture without a lagphase. Sporulation was induced by growing cells in modified Shaeffer's sporulation medium (MSSM; 16 g of Nutrient Broth [Difco], 2 g of KCl, 0.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1 ml of CaNO3 [1 M], 1 ml of MnCl2 [0.1 M], 1 ml of FeSO4 [0.1 M] per liter). In MSSM, experimental cultures were prepared in the same manner as for LB medium except that antibiotics were used at one-fourth of the concentrations used in agar (see above). All liquid growth was performed in conical flasks at 37°C, with rotary shaking at 150 rpm. Cultures occupied approximately 6 to 9% of the total flask volume.

Gel retardation and in vitro recombination assays.

The methods used were those of Blakely et al. (4, 6). Each reaction contained recombinase at a final concentration of 1 μM with approximately 0.1 pmol of radiolabeled DNA. Binding reactions were performed in 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 100 μg of poly (dI-dC) per ml at 37°C for 10 min before electrophoresis through 6% polyacrlyamide at 4°C. Suicide cleavage reactions used binding buffer as described above but were incubated at 37°C for 1 h before electrophoresis through 6% polyacrylamide containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

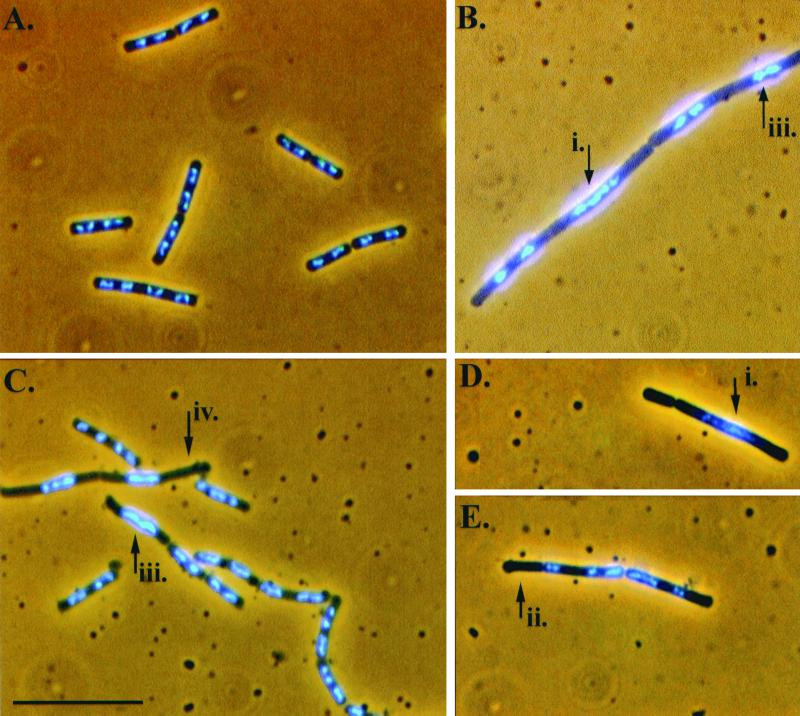

DAPI staining and microscopy.

Nucleoid staining was performed using DAPI (4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Cells were fixed prior to staining in 0.37% formalin. First, 20 μl of fixed cell samples was adsorbed onto 0.1% (wt/vol) poly-l-lysine-treated coverslips for 5 min before placing the coverslips onto 20-μl pools of DAPI at a concentration of 1 μg ml−1 for 30 min. The coverslips were then placed upon a slide containing a single drop of Slow-Fade (Molecular Probes) and sealed. Fluorescent observations were made with a Zeiss Axioskop Fluorescent microscope using standard DAPI filter sets. Images were photographed with a Sony DKC-5000 digital camera and acquired with Adobe Photoshop Software v4.0. Software processing of photographs was restricted to brightness and contrast adjustments only. Four different nucleoid phenotypes were scored as indications of abnormal chromosome partitioning in this study. These four phenotypes are indicated with arrows in Fig. 1 and are briefly described in the accompanying legend.

FIG. 1.

Micrographs of DAPI-stained cells fixed during mid-exponential-phase growth showing the mutant strain nucleoid abnormalities discussed in this study. The parent strain (BR151) (A), dif mutant (B), and codV mutants (C, D, and E) are shown. The numbered arrows point to four different signs of partitioning abnormalities: i, long, continuous nucleoid; ii, anucleate cells; iii, unpartitioned nucleoids occupying the center of a long and otherwise nucleoid-less cell; iv, nucleoids similar to those indicated by arrow iii, except that in these cases the nucleoids occupy a particular side of the cell, while the remaining area of the cell is nucleoid-less, can also be seen. ripX cells have been described previously (34). See Table 3 for a cumulative scoring of these abnormalities. Scale bar, 10 μm.

RESULTS

Cloned and synthetic dif DNA integrates into recA backgrounds at high frequency.

The candidate B. subtilis dif (Bsdif) sequence used in this work was chosen for study based on three criteria: its proximity to the terminus of chromosome replication, its partial sequence identity with the E. coli dif site, and its proximity to a tRNA gene. The significance of the site's proximity to a tRNA gene lies in the observation that several of the bacteriophage that utilize tyrosine site-specific recombination to integrate into host bacterial chromosomes do so near to tRNA genes. It has been speculated that these localities protect the phage from chromosomal deletion events (http://members.home.net/domespo/trhome.html). It should also be noted that the B. subtilis dif site, like E. coli dif, is located intergenically.

Based on the features described above, we used PCR to amplify a 1,286-bp segment of the B. subtilis chromosome that contained the candidate Bsdif site. This fragment was then cloned into an integrative plasmid carrying an erythromycin resistance cassette (erm). This plasmid (pSAS90-4) and several derivatives were analyzed for their ability to integrate into the chromosome of B. subtilis recA strains. Homologous recombination in recA strains of B. subtilis is normally undetectable and, therefore, any erm-resistant colonies resulting from transformations using the various plasmid constructs had presumptively arisen via a site-specific recombination event.

The plasmid containing the full 1,286-bp PCR fragment (pSAS90-4), as well as a 679-bp deletion derivative that retained the candidate Bsdif site (pSAS92-2), integrated into two different recA backgrounds at a high frequency. However, neither the integrative vector by itself (pPP390) nor a derivative with the candidate Bsdif site deleted (pSAS91-2) was able to integrate into the recA strains of B. subtilis (Table 2). Additionally, we tested a plasmid-borne 28-bp synthetic Bsdif for its ability to confer integration proficiency in recA recipient strains of B. subtilis. This 28-bp sequence alone was sufficient to confer integrative capability to the vector in which it was cloned (Table 2). Several other candidate Bsdif sites located near the terminus of replication, and with higher identity to the Ecdif site, failed to confer integrative proficiency to the plasmids that they were cloned into (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Integration efficiency of Bsdif-containing plasmids in recA and other mutant strains

| Strain (relevant genotype) | No. of antibiotic-resistant transformants using the DNA indicateda

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DNA | pPP390 | pSAS91-2 | pSAS90-4 | pSAS92-2 | pSAS103 | pSAS105 | pECE85 | |

| SL992 (recA4) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 200 | 332 | 78 | 105 | 2,873 |

| SL7360 (recA::neo) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 212 | 498 | 32 | 12 | 1,616 |

| SL7370 (ripX::spc recA::neo) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 600 |

| SL8541 (codV::erm recA::neo) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0 | ND | 1,003 |

| SL8630 (codV::tet recA::neo)b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,684 |

| SL8420 (Δdif::neo) | 1 | 0 | ND | 0 | 0 | ND | 1 | 2,164 |

Approximately 8 μg per ml of competent culture was used. A total of 0.3 ml of culture was plated in each case. The pSAS series of plasmids contain various portions of the Bsdif region cloned into plasmids that cannot replicate in B. subtilis. The positive control DNA used was the shuttle plasmid pECE85. ND, not determined.

Nonisogenic strain (strain 168) with parent strain (BR151).

Integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids is dependent on the presence of chromosomal dif, RipX, and CodV.

The ability of the 28-bp sequence to support integration into recA strains of B. subtilis suggested that the mode of entry into the chromosome was mediated by site-specific recombination. Several studies have shown low-frequency integration of plasmids into various chromosomal regions in B. subtilis recA mutants (18, 19, 43). To determine if the RipX and/or CodV recombinases were specifically participating in the catalysis of the integration events at the chromosomal Bsdif site, we evaluated strains that were mutated at the ripX or codV loci or else deleted of chromosomal Bsdif for their ability to support integration into a recA strain. The results showed that in the absence of either RipX, CodV, or the chromosomal Bsdif site, integration of the Bsdif-containing plasmids was abolished (Table 2).

Deletion induced filamentation.

If the Bsdif site discussed above is a unique site where CodV and RipX mediate chromosome dimer resolution, then deletion of the Bsdif site would be expected to result in chromosome partitioning failures and cellular filamentation in a portion of the cell population. To test this experimentally, we constructed a strain in which the Bsdif sequence DNA was replaced with a neomycin resistance cassette (SL8420). The dif-deleted cells were grown in LB medium and fixed during mid-exponential phase. DAPI staining of the fixed cells showed that about 25% of the sampled cell population contained evidence of chromosome partitioning failure (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The appearance and penetration of the dif-deleted phenotype was very similar to that seen in ripX mutants (Table 3) (34). Additionally, as is the case for ripX and codV mutants, cellular growth rates and competence were diminished in the dif deletion mutant (data not shown). The dif deletion strain used in this study also deletes the 3′ portions of the flanking ynfE and ynfF genes. A strain constructed containing mutations in both ynfE and ynfF, but retaining the Bsdif site (SL8633), did not display significant partitioning defects (<1%, data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Nucleoid scoring and sporulation frequency of B. subtilis mutants implicated in chromosome dimer resolution

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Nucleoid scoring

|

Sporulation frequencyb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells with partition defects (%)a | Anucleate (%) | Proportion phase brightc | Relative sporulationd | |

| BR151 (parent) | 0.56 | 0 | 0.77 | 1.0 |

| SL7355 (codV::neo) | 14 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.75 |

| SL7376 (ripX::cat) | 25 | 1.6 | 0.52 | 0.67 |

| SL8420 (Δdif::neo) | 25 | 1.3 | 0.52 | 0.67 |

| SL7513 (ΔSPβ parent) | 0.66 | 0 | 0.62 | 1.0 |

| SL7752 (ΔSPβ codV::neo) | 29 | 9.2 | 0.38 | 0.61 |

| SL7519 (ΔSPβ ripX::cat) | 41 | 11 | 0.38 | 0.61 |

| SL8449 (ΔSPβ Δdif::neo) | 36 | 7.9 | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| SL8081 (yopP::spc) | 1.6 | 0 | 0.68 | 0.88 |

| SL8101 (yopP::spc codV::neo) | 31 | 2.9 | 0.54 | 0.70 |

| SL8172 (yopP::spc ripX::cat) | 41 | 4.7 | 0.51 | 0.66 |

| SL8540 (yopP::spc Δdif::neo) | 40 | 3.3 | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| SL7375 (spoIIIE::spc) | 1.3 | 0.1 | NDe | ND |

| SL8562 (ytpT::spc) | 0.6 | 0.1 | ND | ND |

| SL8626 (spoIIIE::spc ytpT::erm) | 6.2 | 0 | ND | ND |

Percentage shown is the sum of all four abnormal nucleoid phenotypes (includes anucleate cells) shown and described in Fig. 1. At least 600 cells were scored per strain.

Scoring was done at t20 in a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber by phase-contrast microscopy.

Results presented are the average of two independent experiments, > 1,000 phase-bright spores and phase-dark cells were scored per strain. A 95% confidence limit for all proportions was found between (±) 0.02 and 0.03.

Relative sporulation is presented with respect to the appropriate parent strain (i.e., SL7513 for ΔSPβ, BR151 for other strains).

ND, not determined.

Integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids does not require the E. coli FtsK homologues SpoIIIE or YtpT.

In E. coli it has been established that, in addition to the Xer recombinases, at least one other protein, FtsK, is required for resolution of chromosome multimers in vivo (10, 37). B. subtilis SpoIIIE and YtpT are, respectively, 48 and 49% identical to the C terminus of the E. coli FtsK protein. Unlike FtsK, however, SpoIIIE is normally not required during vegetative growth. Instead, SpoIIIE's principal function is during the specialized development of a spore, where it is required for the movement of chromosomal DNA into the small prespore compartment (35, 45). At present we are not aware of any published data on ytpT. Our observations of a ytpT deletion mutant and a spoIIIE mutant did not reveal a substantial nucleoid phenotype. However, inspection of nucleoids in a ytpT spoIIIE double mutant revealed a slight partitioning defect (Table 3). Therefore, it remained possible that YtpT and/or SpoIIIE contributed to the chromosome resolution reactions mediated at Bsdif. However, integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids (pSAS141, −142, −143, and −144) still occurred in the absence of SpoIIIE and/or YtpT (Table 4). These results reinforce the conclusion that SpoIIIE and YtpT are not required in CodV- and RipX-mediated site-specific recombination reactions at Bsdif.

TABLE 4.

Integration efficiency of Bsdif-containing plasmids in various FtsK-like mutant backgrounds

| Strain (relevant genotype) | No. of antibiotic-resistant transformants using the DNA indicateda

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DNA | pSAS141 | pSAS142 | pSAS143 | pSAS144 | pECE85 | |

| SL7360 (recA::neo) | 0 | 551 | 449 | 165 | 107 | 1,532 |

| SL7412 (recA::neo spoIIIE::spc) | 0 | 398 | 247 | 114 | 50 | 1,862 |

| SL8576 (recA::neo ytpT::spc) | 0 | 626 | 522 | 240 | 96 | 2,280 |

| SL8629 (recA::neo spoIIIE::spc ytpT::erm) | 0 | 378 | 291 | 144 | 16 | 1,240 |

Approximately 8 μg per ml of competent culture was used. A total of 0.3 ml of culture was plated in each case. The pSAS series of plasmids contain various portions of the Bsdif region cloned into nonautonomously replicating plasmids. The Positive control DNA used in these experiments was the shuttle plasmid pECE85.

CodV and RipX bind to the B. subtilis dif site.

Our previous in vitro experiments demonstrated that CodV and RipX were capable of binding the E. coli dif site and that they could interact with XerC and XerD despite the great evolutionary divergence of the two organisms from which the proteins were derived. Additional evidence that CodV and RipX are catalytic partners was provided by the efficient resolution of a preformed, artificial Ecdif Holliday junction in vitro. This experiment also clearly indicated that a productive synapse was only formed in the presence of both recombinases (34).

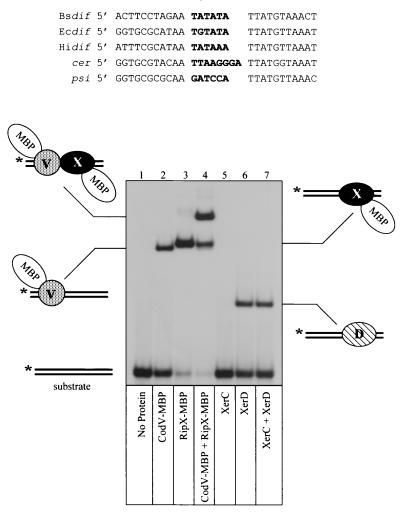

The Bsdif site is defined by two 11-bp half-sites that share partial dyad symmetry separated by a 6-bp central region. An alignment of Bsdif with dif sites from E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae, and two plasmid-borne recombination sites demonstrates that the right half-site sequence is highly conserved (9 of 11 bp matches to Ecdif), while the left half-site is more divergent (5 of 11 bp matches to Ecdif; Fig. 2). The sequence similarity of the right half-site probably explains the observed high affinity binding of RipX to the E. coli dif site (34).

FIG. 2.

Gel retardation analysis of recombinase binding to Bsdif DNA. The aligned recombination site sequences are Bsdif from B. subtilis, Hidif from H. influenzae, Ecdif from E. coli; cer from ColE1; and psi from pSC101. Central region sequences are in boldface type. The bottom panel shows binding of CodV- and RipX-MBP fusions to 32P-radiolabeled (∗) Bsdif substrate. The composition of each retarded complex is indicated adjacent to the autoradiogram. Recombinases present in each reaction are shown below the appropriate lane.

To ascertain if CodV and RipX could bind specifically to the Bsdif site, we used gel retardation analysis of radiolabeled DNA with purified MBP fusions of the recombinases (Fig. 2). Addition of CodV-MBP to Bsdif gave rise to a single protein-DNA complex that migrated with a mobility consistent with a single recombinase monomer binding to the recombination site (Fig. 2, lane 2) (4). Incubation of RipX-MBP with Bsdif also gave rise to a single major complex that was consistent with binding of a single monomer (Fig. 2, lane 3). Note, however, that the RipX complex was more retarded than the CodV complex; Since the two proteins are of similar size, this may indicate that RipX induces a greater degree of DNA bending. There is also some evidence from this gel that RipX can bind to both half-sites, albeit in a noncooperative manner. Similar results have been observed during studies of E. coli XerD binding to Ecdif (8). The addition of both recombinases to Bsdif generated a complex that had a greatly reduced mobility, indicating the binding of both recombinases (Fig. 2, lane 4). Binding of CodV and RipX appears to be cooperative, as indicated by comparing the amount of DNA bound by CodV alone (40%) to the amount bound by both recombinases (80%). Neither protein bound to unrelated DNA (data not shown).

To extend our previous comparison of the B. subtilis and E. coli recombinases, we also used purified wild-type XerC and XerD in our binding studies. Addition of XerC to Bsdif did not produce a detectable complex; however, addition of XerD alone gave rise to a complex consistent with binding of one XerD monomer (Fig. 2, lanes 5 and 6). A mixture of XerC and XerD with Bsdif gave rise to a single complex that represented XerD binding (Fig. 2, lane 7). We have only detected a complex containing both XerC and XerD after long exposures of autoradiograms, which indicates that the cooperative interactions between these recombinases are not sufficiently strong to overcome the low affinity of XerC for the Bsdif site (data not shown). This result also explains the observation that a Bsdif site present in a plasmid does not undergo Xer-mediated site-specific recombination in E. coli (data not shown).

Our previous data that showed RipX binding to the right half-site of Ecdif, along with the high conservation of the right half-sites between Ecdif and Bsdif, suggested that RipX should also bind with high affinity to the right half-site of Bsdif. This speculation was confirmed by gel retardation studies using isolated half-sites of Bsdif (Fig. 3). Reaction of RipX with the right half-site produced a complex consistent with a single monomer binding to the DNA (Fig. 3, lane 6).

FIG. 3.

Gel retardation analysis of CodV-MBP and RipX-MBP binding to half-sites of Bsdif. Each panel shows an autoradiogram of recombinase binding to 32P-labeled (∗) half-sites of Bsdif. The sequence of each half-site is indicated above the appropriate panel, while the composition of each complex is indicated beside the autoradiograms. The recombinase present in each reaction is shown below the appropriate lane.

A reaction containing CodV-MBP with the left half-site gave rise to a single detectable complex (Fig. 3, lane 2); however, addition of RipX to the left half-site also produced a single faint complex (Fig. 3, lane 3). Binding of RipX to both half-sites explains the presence of the faint complex representing two monomers of RipX on the full Bsdif site (Fig. 2, lane 3). Note that the apparent affinities of CodV and RipX for the left and right half-sites, respectively, is lower than that observed for the full site; this may be explained by the absence of the last three bases of the central region which may be required to provide either specific base or phosphate interactions during binding to the full site. In the case of XerC and XerD binding to Ecdif, both base and phosphate interactions within the central region have been detected (7). We could not detect any protein-DNA complexes in reactions containing CodV and the right half-site of Bsdif (Fig. 3, lane 5).

Together these data demonstrate that CodV and RipX bind with high affinity to the 28-bp putative dif site implicated in recA-independent recombination between cloned B. subtilis chromosomal fragments and a site on the chromosome. The data also demonstrate that CodV binds preferentially to the left half-site and RipX binds to the right half-site of Bsdif.

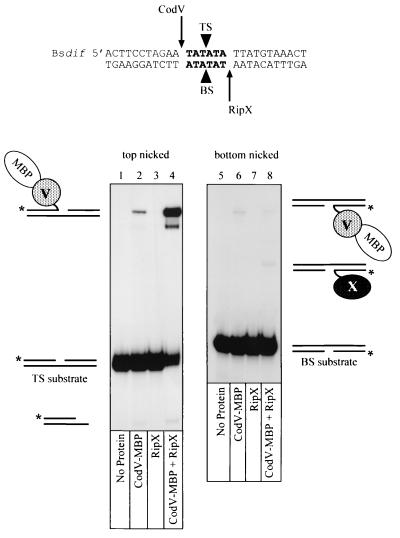

CodV and RipX mediated cleavage of Bsdif DNA in vitro.

The catalytic function of a tyrosine recombinase monomer is the cleavage and subsequent exchange of one DNA strand between two synapsed recombination sites. Strand cleavages can be assayed by trapping recombinase-DNA covalent complexes using linear “suicide” substrates that contain a nick three nucleotides on the 3′ side of the phosphodiester bond that is cleaved by the recombinase. Cleavage of the substrate generates a three-nucleotide fragment that is free to diffuse from the complex, thus preventing religation because the 5′ OH that acts as the nucleophile is no longer present. Based on the sequence similarities between the putative B. subtilis dif site and the sites from E. coli and H. influenzae, we constructed suicide substrates with nicks in the middle of the central region on either the top strand (TS) or the bottom strand (BS; Fig. 4). By convention, the top strand is the first XerC-mediated strand exchange during site-specific recombination at the psi site (13).

FIG. 4.

Recombinase-mediated strand cleavage of Bsdif DNA. 32P-radiolabeled (∗) suicide substrates based on the Bsdif sequence were constructed with a nick (black triangles) either in the top strand (TS) or the bottom strand (BS) of the central region (boldface letters). The proposed positions of strand cleavage for CodV and RipX are indicated at either end of the central region by arrows. The bottom panels show autoradiograms of cleavage reactions analysed by denaturing gel electrophoresis in the presence of 0.1% SDS. The composition of each covalent complex is indicated adjacent to the autoradiogram, while the recombinases present in each reaction are indicated below the appropriate lane.

Covalent complexes generated by reaction of recombinases with radiolabeled suicide substrates were detected by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of SDS. To determine which recombinase was responsible for cleavage of each DNA strand, we incubated mixtures of CodV-MBP and wild-type RipX at protein concentrations that ensured >90% DNA binding (data not shown). The size difference between the recombinases enabled us to detect molecular mass differences during gel electrophoresis. Incubation of CodV-MBP alone with a top-strand nicked substrate (TS) generated a covalent complex that migrated behind the substrate and represented cleavage of approximately 2% of the radiolabeled DNA after 1 h at 37°C (Fig. 4, lane 2). Similar low levels of XerC-mediated top-strand cleavages at Ecdif in the absence of XerD have been reported previously (4). We could not detect any strand cleavages mediated by RipX with this top-strand nicked-substrate (Fig. 4, lane 3).

Incubation of both CodV-MBP and RipX with the TS substrate led to conversion of approximately 70% of the substrate to covalent complex. Note that the mobility of this complex confirms that CodV-MBP is responsible for cleaving the top strand of Bsdif. The band migrating just below the main complex presumably results from proteolytic degradation of CodV-MBP. There is also some evidence that bottom-strand cleavages are occurring at a low level in this reaction, as indicated by the band migrating ahead of the substrate. This product is specifically generated with the BsdifTS substrate and is not produced with the equivalent EcdifTS substrate (34). The difference between the amounts of strand cleavage generated by CodV-MBP in the absence or presence of RipX demonstrates the importance of interactions between the partner recombinases for controlling catalytic activity in a bound complex.

To directly determine which recombinase could cleave the bottom strand of Bsdif, we performed reactions with the bottom-strand nicked-substrate (BS; Fig. 4). Incubation of CodV-MBP alone with the BS substrate generated a covalent complex that represented <0.5% cleavage of the total substrate (Fig. 4, lane 6). Our binding studies with CodV-MBP and un-nicked Bsdif (Fig. 2) had shown that CodV bound the left half-site preferentially; however, binding to the BS substrate indicated that two monomers of CodV-MBP could bind with low affinity (data not shown); we presume that this complex is responsible for the observed cleavage of the bottom strand. Binding and cleavage by two XerC monomers on a bottom-strand-nicked Ecdif substrate has also been observed. It has been proposed that the nick in the DNA provides additional flexibility that facilitates protein-protein interactions that would not normally occur on un-nicked DNA (4). Reaction of RipX with the BS substrate did not produce any detectable covalent complexes (Fig. 4, lane 7); however, incubation of CodV-MBP and RipX with BS gave rise to a complex that migrated in a position consistent with a monomer of RipX covalently linked to the bottom strand of the DNA and corresponded to cleavage of <0.5% of the substrate (Fig. 4, lane 8). Note that a low level of cleavage mediated by CodV-MBP is still evident in this reaction.

We concluded from these results that, during site-specific recombination mediated by the B. subtilis recombinases at the Bsdif site, CodV preferentially cleaves the top strand of linear Bsdif DNA efficiently, while RipX cleaves the bottom strand inefficiently. Cleavage of the scissile phosphate adjacent to the half-site at which each recombinase is bound also indicates that strand cleavages occur in cis. Strand cleavages mediated by XerC and XerD also occur in cis, while cleavage mediated the yeast 2μm recombinase FLP occurs in trans (4, 25).

The SPβ phage gene yopP affects chromosome dimer resolution in vivo.

The SPβ prophage is maintained near the terminus of almost all strains of B. subtilis 168 (24, 47). The presence of two genes in the SPβ prophage whose products show weak similarity to CodV and RipX stimulated our investigation into the possibility that the relative lack of chromosome abnormalities seen in codV mutants was the result of an SPβ prophage recombinase substituting for CodV in recombination reactions. The YomM and YopP proteins coded by the SPβ prophage share, respectively, 19 and 22% identity with the CodV recombinase, and each possesses several highly conserved residues found in the tyrosine family of site-specific recombinases (no Bsdifhomologs were found in the SPβ sequence using computer searches allowing up to 8-bp of mismatch).

To test the idea that the SPβ prophage coded for a recombinase capable of substituting for CodV, we constructed a codV mutant in a strain deleted of the SPβ prophage (46). The SPβ(−) codV mutant was fixed during mid-exponential growth and analyzed for evidence of chromosome partitioning failures by DAPI staining followed by microscopic observation of the nucleoids. Using the scoring system for partitioning failure described earlier, we observed a doubling in the number of cells displaying partitioning defects in the SPβ(−) codV mutants compared to the SPβ(+) codV mutant (Table 3).

To determine if YomM or YopP could be assigned a specific role in the large increase of partitioning phenotypes seen in SPβ(−) codV mutants, we examined yomM codV and yopP codV double mutants in our standard SPβ(+) strain. The extent of chromosome partitioning defects in yomM codV double mutants was no greater than that seen in a codV single mutant in the SPβ(+) strain background (data not shown). However, in yopP codV double mutants we observed a doubling in the number of cells exhibiting partitioning defects compared to that seen in the codV mutant (Table 3). The extent of chromosome partitioning failure seen in the SPβ(+) yopP codV double mutant was nearly the same as that seen in the SPβ(−) codV mutant and suggested that YopP may have some role in the resolution of chromosome dimers in the absence of CodV. Note also that the frequency of anucleate cells in particular is substantially elevated in codV, ripX, and dif strains deleted of the SPβ prophage.

Because the total penetration of chromosome partitioning phenotypes in the SPβ(−) ripX and SPβ(−) dif mutants was also increased above that seen in their SPβ(+) backgrounds (Table 3), we investigated the effect of yopP mutations in ripX and dif mutants in the SPβ(+) strain. Interestingly, the addition of a yopP mutation to ripX and dif mutants in the SPβ(+) background increased the total penetration of chromosome partitioning phenotypes to nearly the same extent as that seen in the SPβ(−) ripX and SPβ(−) dif mutants (Table 3).

Sporulation is diminished in mutants implicated in chromosome dimer resolution.

Successful development of a spore requires that a chromosome be packaged into the small prespore compartment. The small architecture of the prespore compartment results from the construction of a highly asymmetric spore septum early in the developmental process (31). Under normal circumstances mature B. subtilis spores contain a single, completed chromosome (11). The presence of a dimerized chromosome therefore would present a developing spore with a difficult challenge in terms of packaging twice the normal amount of DNA into a spatially confined location. Thus, we have utilized the sporulation program of B. subtilis as a second, indirect measure of partitioning difficulties in the various mutant strains examined previously by nucleoid appearance. Strains were grown in MSSM to promote sporulation, followed by examination using phase-contrast microscopy to determine the efficiency of sporulation. The codV, ripX, and dif mutants exhibited decreased sporulation frequencies relative to their parent strain (Table 3). The decreases in sporulation frequency observed among the various mutants showed some correlation with the increases in abnormal nucleoid phenotype recorded during vegetative growth (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This report illuminates three prominent features of chromosome partitioning in B. subtilis. First, we have identified and characterized a B. subtilis dif site. Second, we show that the B. subtilis FtsK-like homologues SpoIIIE and YtpT are not required for recombination at Bsdif. Third, we have detailed an exacerbation of chromosome partitioning defects associated with the absence of the SPβ phage gene product YopP. The absence of YopP or the SPβ phage had its most severe effect in the codV mutant.

The B. subtilis dif site is located at approximately 166° of the chromosome, at bp 1,941,798 to 1,941,825. Three lines of experimental evidence have been provided to substantiate the authenticity of this site. First, integration of nonautonomously replicating plasmids carrying either cloned Bsdif DNA or a synthesized Bsdif-oligomer occurs at a high frequency in recA backgrounds. The integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids was dependent on the presence of RipX, CodV, and the chromosomal dif site. Second, deletion of the Bsdif site from the chromosome resulted in the development of a subpopulation of cells with aberrantly partitioned nucleoids that closely resembled in appearance and frequency those seen in ripX mutants. Third, the RipX and CodV proteins demonstrated specific binding to, and cleavage of, synthetic Bsdif DNA in vitro.

In E. coli the septal localization of FtsK is required for chromosome dimer resolution and site-specific recombination at other ectopic dif sites, possibly through a role in altering Holliday junction conformation after the first XerC-mediated strand exchange. Inhibition of cell division at a nonpermissive temperature in an ftsZ temperature-sensitive mutant of E. coli leads to a mild segregation defect that has been ascribed to the failure of dimer resolution, presumably as a consequence of FtsK failing to localize (33). Recchia and Sherratt have since proposed that all Eubacteria with circular chromosomes and Xer homologues also have FtsK homologues and suggest that this demonstrates a functional interaction (32).

B. subtilis has two proteins, SpoIIIE and YtpT, that share substantial homology to the E. coli FtsK protein. However, integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids into recA backgrounds persisted in the absence of the SpoIIIE and/or YtpT proteins. In contrast, Xer-mediated plasmid integration at Ecdif is reduced by 100-fold in an ftsK strain of E. coli (33). These observations demonstrate that neither YtpT alone nor YtpT in combination with SpoIIIE has a required FtsK-like function in cell division or chromosome dimer resolution in B. subtilis. Additionally, it has also been previously shown that reducing the levels of FtsZ in outgrowing spores of B. subtilis did not lead to any obvious defects in timing or rate of chromosome segregation (29). Therefore, a possible conclusion from these combined observations is that the control of dimer resolution in B. subtilis is not intimately linked to septation.

Is there an analogue of FtsK that controls dimer resolution and/or links it to division somehow in B. subtilis? One potential candidate protein, PrfA, which has been implicated in homologous recombination (17), has been proposed by Pederson and Setlow (30). Mutations in prfA generate a subpopulation of cells with a chromosome segregation defect that resembles the RipX phenotype, i.e., aberrant nucleoids and anucleate cells. It is not yet clear, however, whether the prfA phenotype is a true partition defect or a consequence of aberrant recombination as seen in some recA strains of B. subtilis (34).

The dif sites from E. coli and H. influenzae have been characterized by the presence of two 11-bp half-sites that contain partial dyad symmetry separated by a 6-bp central region (5′-ATAA N6 TTAT) that delineate the positions of strand cleavage and exchange (4, 27). The right half-site of Bsdif is remarkably conserved compared to the gram-negative bacterial sites (9 of 11 bp match) considering their great evolutionary divergence. Analysis of the XerD crystal structure has suggested six amino acids in a helix-turn-helix motif that make base- and phosphate-specific contacts that define sequence recognition of the Ecdif right half-site (40). Five of these six residues are conserved in RipX.

The left half-site of Bsdif is much more divergent compared to other XerC binding sites. We particularly note the G residue in the dyad symmetry as being unusual; sequence changes at this position are usually indicative of plasmid-borne recombination sites (Fig. 2) (14, 41). The binding site sequence divergence is also reflected by differences between XerC and CodV in the residues implicated in base and phosphate contacts that determine binding specificity.

Phylogenetic analysis of the Xer recombinases suggests that CodV may have arisen from a gene duplication of an ancestral homologue of RipX and CodV, while XerC may have arisen from a duplication event that occurred at an earlier time (see http://members.home.net/domespo/tr/fam-xer.html). The evolutionary maintenance of two Xer recombinases in many different eubacteria suggests that the functional control provided is of great importance to the outcome of the recombination reaction and thus successful chromosome segregation. Having two recombinases provides two potential advantages: (i) correct site alignment is always ensured, thus avoiding a homology “testing” step after the first strand exchange, and (ii) precise control over catalysis, and consequently the order of strand cleavage and exchange, is also ensured. Previous in vitro work has shown that XerC cleaves Ecdif DNA more frequently than XerD, and as a consequence XerC promotes top-strand exchange first to form a Holliday junction that is subsequently resolved by XerD (2, 4, 5). We have shown that CodV cleaves linear Bsdif preferentially, and by inference we suggest that CodV performs the first strand exchange to generate a Holliday junction that is then a substrate for RipX. We also note that the central region sequence of Bsdif is very similar to Ecdif (5 of 6 bp matches) and suggest that maintenance of this sequence is of major functional importance. The ratio of purines to pyrimidines in the central region has been implicated in the folding preference of the Holliday junction formed by the first strand exchange and as such dictates which pair of recombinases will be catalytically active (3, 2). The postulated role for FtsK in E. coli is the alteration of the Ecdif Holliday junction conformation to enable the second strand exchange (33). The similarity between Ecdif and Bsdif central regions suggests that an analogue of FtsK, other than SpoIIIE and/or YtpT, responsible for controlling catalysis of CodV and RipX may exist in B. subtilis. The evolutionary conservation between Bsdif and Ecdif and the presence of Xer recombinases in many organisms led us to search the microbial genome databases for similar sequences in gram-positive bacteria. As an example of the possible conservation of dif sites, we detected a sequence in Staphylococcus aureus with a 27-of-28- bp match to Bsdif (5′ACTTCCTATAA TATATA TTATGTAAACT [http://www.tigr.org]) (Fig. 2). The functional importance of this sequence remains to be tested.

In our previous examinations of ripX and codV mutants we saw little effect of a codV mutation on nucleoid morphology (34). In experiments presented here, where a broader range of partitioning difficulty indicators was assessed, codV mutants revealed a weak partitioning phenotype (Table 3). We speculated, therefore, that B. subtilis might retain a protein that is redundant for CodV's function in chromosome dimer resolution reactions or that RipX itself might be able to perform the resolution reactions without a “XerC-like” partner recombinase. To address the first possibility, we examined two proteins in the SPβ bacteriophage that possess limited homology with the RipX and CodV proteins. YomM and YopP have between 19 to 25% identity with CodV and RipX in pairwise alignments, and each has an R…H-X-X-K…Y motif that can be aligned with the R…H-X-X-R…Y motif found in almost all tyrosine recombinases (16, 28) (note the substitution of the canonical second arginine with a lysine residue in the phage sequence).

An encouraging sign that one or both of these proteins might have a suppressing function in codV mutants came from an initial examination of codV mutants in strains lacking the SPβ phage. These SPβ(−) codV strains displayed a twofold increase in the amount of cells exhibiting aberrant nucleoids over that seen in the SPβ(+) codV cognate strain (Table 3). Moreover, although the yomM codV double mutant did not display an increase in nucleoid phenotype over that seen in the codV single mutant, the yopP codV double mutant did display an increase in the number of cells with aberrant nucleoids over that seen in a codV mutant, again, by about twofold. By themselves, yopP (SL8081) and ΔSPβ (SL7513) had little if any affect on nucleoid phenotype. The similar increases in aberrant nucleoid phenotype observed in the SPβ(−) codV mutant and yopP codV double mutant suggested that the absence of YopP was responsible for most, if not all, of the difference in nucleoid phenotype penetration between SPβ(+) and SPβ(−) codV strains.

However, three lines of evidence argue against YopP being able to partially substitute for CodV in site-specific recombination reactions at Bsdif. First, we have not observed integration of Bsdif-containing plasmids in codV recA mutants. Second, yopP mutations elevate not only the codV nucleoid phenotype but also the ripX and dif phenotypes, albeit to a lesser extent. Third, we have not been able to demonstrate binding of purified YopP to the Bsdif site either alone, or in combination with YomM, CodV, or RipX. The simplest explanation based on our accumulated data is that YopP does not have a role in chromosome dimer resolution per se but rather some facilitative role during chromosome partitioning in general. One possibility, for example, is that YopP acts at a second chromosomal site as a fail-safe mechanism should CodV-RipX activity at Bsdif be impaired in some way. This explanation is consistent with our observation that yopP mutations elevate not only the amount of codV aberrant nucleoid phenotype but also the phenotypes associated with ripX and dif. This explanation is also consistent with the penetration of phenotypes observed in the SPβ(−) background. The primary deficiency that we note in this model is that it leaves unexplained why the codV mutant nucleoid phenotype is substantially less prominent than those seen in ripX and dif strains. It is formally possible that RecA itself (absent in our integration assays to ensure that homologous recombination was eliminated) is able to facilitate some amount of recombination at or near Bsdif in codV strains, but not in ripX and dif strains, thereby reducing to some extent the apparent amount of aberrant nucleoids seen in the codV strains.

Finally, we note that the identification of a B. subtilis dif site has an experimental utility. By employing integrative vectors that contain the Bsdif site, genetic information can be introduced at a relatively high frequency into the chromosomes of recA strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Sherratt for advice and encouragement. We thank Vasant K. Chary for helpful advice.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM43577 (to P.J.P.) and training grant T32 AI07101 (to S.A.S.). G.W.B. was supported by a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellowship (039542/A/98).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciszewska L K, Grainge I, Sherratt D J. Action of site-specific recombinases XerC and XerD on tethered Holliday junctions. EMBO J. 1997;16:3731–3743. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azaro M A, Landy A. The isomeric preference of Holliday junctions influences resolution bias by lambda integrase. EMBO J. 1997;16:744–755. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blakely G W, Davidson A O, Sherratt D J. Binding and cleavage of nicked substrates by site-specific recombinases XerC and XerD. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:30–39. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blakely G W, Davidson A O, Sherratt D J. Sequential strand exchange by XerC and XerD during site-specific recombination at dif. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9930–9936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakely G, May G, McCulloch R, Arcisewska L K, Sherratt D. Two related recombinases are required for site-specific recombination at dif and cer in E. coli K12. Cell. 1993;75:351–361. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80076-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakely G W, Sherratt D J. Interactions of the site-specific recombinases XerC and XerD with the recombination site dif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5613–5620. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakely G, Sherratt D. Determinants of selectivity in Xer site-specific recombination. Genes Dev. 1996;10:762–773. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakely G, Colloms S D, May G, Burke M, Sherratt D J. Escherichia coli XerC recombinase is required for chromosomal segregation at cell division. New Biol. 1991;3:789–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle D S, Grant D, Draper G C, Donachie W D. All major regions of FtsK are required for resolution of chromosome dimers. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4124–4127. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.4124-4127.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callister H, Wake R G. Completed chromosomes in thymine-requiring Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:579–582. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.2.579-582.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clerget M. Site-specific recombination promoted by a short DNA segment of plasmid R1 and by a homologous segment in the terminus region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. New Biol. 1991;3:780–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colloms S D, McCulloch R, Grant K, Neilson L, Sherratt D J. Xer-mediated site-specific recombination in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:1172–1181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornet F, Mortier I, Patte J, Louarn J M. Plasmid pSC101 harbors a recombination site, psi, which is able to resolve plasmid multimers and to substitute for the analogous chromosomal Escherichia coli site dif. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3188–3195. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3188-3195.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox M M, Goodman M F, Kreuzer K N, Sherratt D J, Sandler S J, Marians K J. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature. 2000;404:37–41. doi: 10.1038/35003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esposito D, Scocca J L. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: evolution of a conserved active site domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3605–3614. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandéz S, Sorkin A, Alonso J C. Genetic recombination in Bacillus subtilis 168: effects of recU and recS mutations on DNA repair and homologous recombination. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3405–3409. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3405-3409.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ftouhi N, Guillén N. Genetic analysis of fusion recombinants in Bacillus subtilis: function of the recE gene. Genetics. 1990;126:487–496. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofemeister M, Israeli-Reches M, Dubnau D. Integration of plasmid pE194 at multiple sites on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;189:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ireton K, Grossman A D. Coupling between gene expression and DNA synthesis early during development in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8808–8812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ireton K, Gunther IV N W, Grossman A D. SpoOJ is required for normal chromosome segregation as well as the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5320–5329. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5320-5329.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuempel P L, Henson J M, Dircks L, Tecklenberg M, Lim D F. dif, a recA-independent recombination site in the terminus region of the chromosome of Escherichia coli. New Biol. 1991;3:799–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarevic V, Düsterhöft A, Soldo B, Hilbert, H. H, Mauël C, Karamata D. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis temperate bacteriophage SPβc2. Microbiology. 1999;145:1055–1067. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J, Jayaram M. Mechanism of site-specific recombination. Logic of assembling recombinase catalytic site from fractional active sites. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17564–17570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu G, Draper G C, Donachie W D. FtsK is a bifunctional protein involved in cell division and chromosome localization in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:893–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielson L, Blakely G, Sherratt D J. Site-specific recombination at dif by Haemophilus influenzae XerC. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:915–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunes-Düby S E, Kwon H J, Tirumalai R S, Ellenberger T, Landy A. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:391–406. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partridge S R, Wake R G. FtsZ and nucleoid segregation during outgrowth of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2560–2563. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2560-2563.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen L B, Setlow P. Penicillin-binding protein-related factor A is required for proper chromosome segregation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1650–1658. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1650-1658.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piggot P J, Coote J G. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:908–962. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.908-962.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recchia G D, Sherratt D J. Conservation of xer site-specific recombination genes in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1146–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Recchia G D, Aroyo M, Wolf D, Blakely G, Sherratt D J. FtsK-dependent and -independent pathways of Xer site-specific recombination. EMBO J. 1999;18:5724–5734. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sciochetti S A, Piggot P J, Sherratt D J, Blakely G. The ripX locus of Bacillus subtilis encodes a site-specific recombinase involved in proper chromosome partitioning. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6053–6062. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6053-6062.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharpe M E, Errington J. Postseptational chromosome partitioning in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8630–8634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slack F J, Serror P, Joyce E, Sonenshein A L. A gene required for nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:689–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steiner W W, Liu G, Donachie W D, Kuempel P L. The cytoplasmic domain of the FtsK protein is required for resolution of chromosome dimers. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:579–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner W W, Kuempel P L. Sister chromosome exchange frequencies in Escherichia coli analyzed by recombination at the dif resolvase site. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6269–6275. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6269-6275.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiner W W, Kuempel P L. Cell division is required for the resolution of dimer chromosomes at the dif locus of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:257–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanya H S, Arciszewska L K, Baker R A, Bird L E, Sherratt D J, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of the site-specific recombinase, XerD. EMBO J. 1997;16:5178–5187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Summers D K, Sherratt D J. Multimerization of high copy number plasmids causes instability: ColE1 encodes a determinant essential for plasmid monomerization and stability. Cell. 1984;36:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Summers D K, Sherratt D J. Resolution of ColE1 dimers requires a DNA sequence implicated in the three-dimensional organization of the cer site. EMBO J. 1988;7:851–858. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Temeyer K B, Chapman L F. Intermolecular recE4-independent recombination in Bacillus subtilis: formation of plasmid pKBT1. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:518–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00327206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu J-J, Gaukler-Howard M, Piggot P J. Regulation of transcription of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIA locus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:692–698. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.692-698.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu L J, Errington J. Bacillus subtilis SpoIIIE protein required for DNA segregation during asymmetric cell division. Science. 1994;264:572–575. doi: 10.1126/science.8160014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasbin R E, Fields P I, Andersen B J. Properties of Bacillus subtilis 168 derivatives freed of their natural prophages. Gene. 1980;12:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zahler S A. Temperate bacteriophages. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 831–842. [Google Scholar]