Abstract

RNase E, the principal RNase capable of initiating mRNA decay, preferentially attacks 5′-monophosphorylated over 5′-triphosphorylated substrates. Site-specific cleavage in vitro of the rpsT mRNA by RNase H directed by chimeric 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides was employed to create truncated RNAs which are identical to authentic degradative intermediates. The rates of cleavage of two such intermediates by RNase E in the RNA degradosome are significantly faster (2.5- to 8-fold) than that of intact RNA. This verifies the preference of RNase E for degradative intermediates and can explain the frequent “all-or-none” behavior of mRNAs during the decay process.

It is widely believed that the most common pathway of mRNA decay in Escherichia coli is initiated by endonucleolytic cleavage, usually catalyzed by RNase E, but occasionally by other enzymes (1, 5, 19–21). In addition, mRNA decay often appears to proceed in a net 5′ to 3′ direction (2, 8, 21). Experiments with RNA 1 in vivo and more recently with the rpsT mRNA in vitro have shown that monophosphorylated (p) RNAs are more susceptible to RNase E-mediated decay than primary transcripts which are 5′-triphosphorylated (ppp) (13, 16). These findings have been extended to other RNAs, including derivatives of RNA 1 (10), and to another RNase, CafA-RNase G, a homolog of RNase E (22). These results imply that following an initial endonucleolytic cleavage, a truncated mRNA fragment becomes a significantly better substrate for all successive endonucleolytic cleavages catalyzed by RNase E or by CafA-RNase G. This would explain the frequently observed “all-or-none” pattern of mRNA decay (5, 19, 20). Nonetheless, there are no data which prove that the 3′-product of an initial RNase E cleavage on a known substrate is, in fact, more susceptible to a second endonucleolytic cleavage. To address this point and to extend the generality of the initial observations made on full-length RNA substrates, we have created truncated p-rpsT mRNAs and have examined their susceptibility to RNase E cleavage. Our findings show that 5′-end recognition of p-RNA substrates can account for 5′→3′ vectorial decay of mRNA substrates (8, 21) and can explain why degradative intermediates rarely accumulate.

Truncated substrates created by oligonucleotide-directed RNase H cleavage.

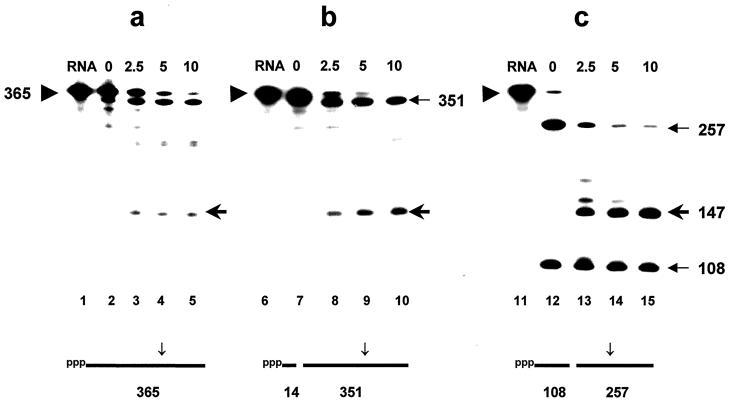

We previously cleaved the rpsTl365 RNA at various points with RNase H directed by selected oligonucleotides to show that RNase E cleavage at the major site (residues 300 to 301) is independent of sequences or secondary structures in the 5′ third of the substrate (17). However, the observed sites of RNase H cleavage and thus the new 5′-p termini were heterogeneous and nonphysiological. In order to create truncated RNAs which more accurately mimic the products of authentic RNase E cleavages in the 5′ third of the rpsT mRNA (14), we designed mixed DNA–2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides (11) to direct specific cleavage at four known sites. Oligonucleotide 1 (to direct cleavage 5′ to residue 99 in rpsT/365 RNA) is 5′-CAAUTCAAAGGGGAA and oligonucleotide 4 (to direct cleavage 3′ to residue 191) is 5′-GCTTACGAGCCUU (see reference 11 for the rational behind the design). Boldface residues are deoxyribonucleotides, whereas underlined residues are 2′-O-methyl ribonucleotides. Chimeric oligonucleotides (∼6 pmol) were mixed with 1 pmol of the synthetic rpsT transcript, rpsT/365 (identical to t87D in reference 17), prepared by “runoff” transcription in the presence of [α32P]CTP (6, 17), in 10 μl of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8)–5 mM MgCl2–100 mM NH4Cl–60 mM KCl–0.1 mM dithiothreitol–5% glycerol (17). RNA-DNA hybrids were formed by heating for 2 min at 90°C and 10 min at 37°C, followed by chilling on ice. RNase H (Amersham-Pharmacia; 2 U) was added, and digestion was performed in a final volume of 20 μl of assay buffer for 90 min at 37°C. The digested RNA was cooled to 30°C, and a zero time sample was removed prior to further digestion (see below). We found that RNase H cleavage directed by such chimeric oligonucleotides was much less efficient than with the corresponding all DNA oligonucleotide. It was necessary to anneal the oligonucleotide to the target RNA at much higher temperatures and to continue the digestion with RNase H for longer periods and at higher temperatures than in our previous experiments (17, 18). Despite considerable effort, two of the chimeric oligonucleotides promoted too limited cleavage (<50%) of the target RNA to be useful (data not shown). Only chimeric oligonucleotides 1 and 4 (see above) yielded informative data, and only oligonucleotide 1 directed full digestion of its target RNA (Fig. 1). Examination of lanes 6 and 7 in Fig. 1b (RNase H cleavage at residues 98 and 99 with oligonucleotide 1) shows that about half of the substrate was cleaved by RNase H (see above). In contrast, lanes 11 and 12 in Fig. 1c (RNase H cleavage with oligonucleotide 4 at residues 190 and 191) show that the rpsT/365 substrate was cleaved nearly to completion. Primer extension experiments (not shown) confirmed that both cleavages by RNase H occurred at the intended site, ± one residue.

FIG. 1.

Time course of digestion of monophosphorylated fragments of rpsT RNA by degradosomes. The ppp-rpsT/365 RNA substrate, internally labeled with [α-32P]CTP, was digested first by RNase H in presence of excess chimeric 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide. The structure of the cleaved products is shown diagrammatically below each panel. Subsequently, the unfractionated products were incubated with purified degradosomes, and samples were removed at the times (in minutes) shown above each lane (see the text). Digestion products were separated by electrophoresis under denaturing conditions and visualized by phosphorimaging. Panels: a, no oligonucleotide; b, oligonucleotide 1; c, oligonucleotide 4. The triangle to the left of each panel points to the untreated rpsT/365 RNA substrate; the 5′ and 3′ products of the initial RNase H digestion and the 147-residue RNase E cleavage product are denoted by arrows in the right margins.

The balance of the RNase H-digested rpsTl365 RNA was supplemented with degradosomes (ca. 4 to 10 μg/ml) to a final volume of 20 μl. Degradosomes were prepared (3, 4) from strain CF881 lacking RNase I. RNase E assays were subsequently performed at 30°C as described earlier (14, 17) but with 50 nM RNA substrate (4). Samples were denatured and separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea. Products were visualized and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.). The amount of substrate remaining at each time point in a digestion was determined and plotted so that the initial rate of the first cleavage of a substrate (i.e., the disappearance of full-length substrate) could be calculated. Figure 1a shows a typical time course of digestion of the native ppp-rpsT/365 RNA substrate, showing the disappearance of full-length substrate (triangle in the left margin) and the appearance of the 147-residue 3′ product (arrow in the right margin). The “precleaved” RNAs prepared above were assayed for their susceptibility to RNase E in parallel (Fig. 1 b and c). Using the 351-nucleotide (nt) substrate with a new 5′-p terminus at residue 99 (directed by oligonucleotide 1), the average rate of cleavage by RNase E in several experiments was 2.5-fold faster than the rate of cleavage of the control substrate (Fig. 1a and b). Likewise, in Fig. 1c, the rate of cleavage of the 257-nt substrate RNA with a new 5′-p terminus at residue 191 (directed by oligonucleotide 4) was eightfold faster. These rates are minimal estimates for several reasons. First, in the case of oligonucleotide 1, the initial 365-nt full-length rpsT RNA is cleaved only partially and is incompletely resolved from the 351-nt product of the first digestion. Second, the presence of excess oligonucleotide from the initial RNase H cleavage can inhibit RNase E activity (data not shown). Third, the concentrations of substrates in these assays was 3- to 10-fold higher than that used previously (16). Reducing the initial concentration of RNA to 20 nM enhanced the differential increase in the initial rate of cleavage of p-rpsTl365 RNA by up to fivefold (data not shown).

Complementary data were obtained by measuring the rate of accumulation of the 147-nt RNase E product. Prior cleavage of the rpsT RNA with oligonucleotide 4 and RNase H (Fig. 1c) accelerated the subsequent rate of formation of the 147-nt product almost 20-fold relative to that observed in Fig. 1a. It is interesting to note that the 108-nt fragment, the 5′ product of RNase H cleavage, extending from residue 83 (pppG) to residue 190, in Fig. 1c is almost completely stable during the digestion, although it contains potential RNase E cleavage sites (14). This fragment evidently competes poorly for the available RNase E activity. We were unable to extend this observation to the substrate in Fig. 1b since its 5′ product of RNase H cleavage is only ∼14 residues and would have run off the gel. Previously, we assayed substrates which had been cleaved by RNase H, and all-DNA oligonucleotides annealed to single-stranded regions of the rpsT RNA with relatively crude sources of RNase E activity. We found that the 5′ products of RNase H cleavage were also resistant to digestion by RNase E, whereas the rate of cleavage of the 3′ product was accelerated fourfold relative to the full-length (ppp) substrate (17), which is consistent with the present data.

End dependence of RNase E.

Data obtained from investigations of the decay of ColE1-encoded RNA 1 in vivo and the cleavage of rpsT and 9S RNAs in vitro have suggested that once a primary transcript is converted to a p-form by RNase E, it becomes a significantly better substrate for subsequent cleavages (13, 16). Directed RNase H cleavage has permitted us to create RNA substrates which accurately mimic degradative intermediates cut once at a known RNase E cleavage site. In both cases tested, the “precleaved” p-rpsT mRNAs subsequently underwent rapid, preferential cleavage(s) without altering the final product. These data would explain why endonucleolytic cleavage intermediates of most mRNAs are normally ephemeral.

A number of stable RNAs, most notably 5S rRNA and 16S rRNA require RNase E for their maturation and are 5′-monophosphorylated (7, 12). How do they resist further cleavage? Two factors likely contribute. First, secondary and tertiary structures compact these RNAs and occlude potential cleavage sites (15). Second, the binding of ribosomal proteins likely stabilizes secondary and tertiary structures and screens any potentially susceptible internal cleavage sites. In this regard, the binding of the FinO protein to FinP RNA greatly reduces its susceptibility to RNase E (9).

Mechanism of 5′-end recognition.

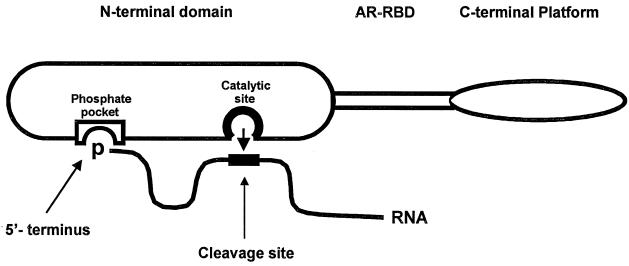

Our data, and those obtained independently with much simpler substrates, clearly show that RNase E (and its homolog, CafA-RNase G) can distinguish between ppp and p termini and that in RNase E, this property resides in its N-terminal “catalytic domain” (10, 22). These data suggest that the Rne protein and its homologs may contain a phosphate-binding pocket which interacts with the 5′ terminus of a substrate, while a second region in the N-terminal domain forms the catalytic site which interacts with a more distant part of the RNA substrate. This is shown schematically in Fig. 2. The putative phosphate-binding pocket would discriminate between p and ppp termini, presumably on the basis of size and net charge. In a more elaborate model, the phosphate-binding pocket and the active site would function alternatively (7). Genetic, biochemical, and structural approaches should elucidate the nature of the putative phosphate-binding pocket and distinguish between these and other models.

FIG. 2.

Simple model for recognition of p-RNAs by RNase E. The three domains of RNase E include the N terminus with catalytic activity, the central arginine-rich RNA binding domain (ARRBD), and the C-terminal “platform” with interaction sites for RhlB, enolase and polynucleotide phosphorylase (not shown) (23). For simplicity, RNase E is drawn as a monomer, but its quaternary structure is unknown. The RNA substrate is shown by a solid line thickened at a potential RNase E cleavage site. RNA sequences between the 5′ end and the site of cleavage are presumed to loop away from the surface of the enzyme. The nucleophilic attack on the phosphodiester bond is shown by the short arrow. The putative phosphate-binding pocket and the active site for catalysis are presumed to be separate sites within the N-terminal domain of the enzyme (see the text).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by grant MT-5396 from the former Medical Research Council of Canada and its successor, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. NSERC grant OGP 0185681 provided partial salary support for C.S.

We also thank other members of the laboratory for their comments, A. Grant Mauk for help in printing the figures, and P. P. Dennis for his constructive criticism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alifano P, Bruni C B, Carlomagno M S. Control of mRNA processing and decay in prokaryotes. Genetica. 1994;94:157–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01443430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apirion D. Degradation of RNA in Escherichia coli: a hypothesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1973;122:313–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00269431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpousis A J, Van Houwe G, Ehretsmann C, Krisch H M. Copurification of E. coli RNase E and PNPase: evidence for a specific association between two enzymes important in RNA processing and degradation. Cell. 1994;76:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coburn G A, Mackie G A. Reconstitution of the degradation of the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20 with purified enzymes. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:1061–1074. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coburn G A, Mackie G A. Degradation of mRNA in Escherichia coli: an old problem with some new twists. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1999;62:55–108. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cormack R S, Mackie G A. Structural requirements for the processing of Escherichia coli 5S ribosomal RNA by RNase E in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:1078–1090. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90316-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghora B K, Apirion D. Structural analysis and in vitro processing to p5 rRNA of a 9S RNA molecule isolated from an rne mutant of E. coli. Cell. 1978;15:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodridge A F, Steege D A. Roles of polyadenylation and nucleolytic cleavage in the filamentous phage mRNA processing and decay pathways in Escherichia coli. RNA. 1999;5:972–985. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerome L J, van Biesen T, Frost L S. Degradation of FinP antisense RNA from F-like plasmids: the RNA-binding protein, FinO, protects FinP from ribonuclease E. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1457–1473. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Diwa A, Belasco J G. Regions of RNase E important for 5′-end dependent RNA cleavage and autoregulated synthesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2468–2475. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2468-2475.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapham J, Yu Y T, Shu M D, Steitz J A, Crothers D M. The position of site-directed cleavage of RNA using RNase H and 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides is dependent on the enzyme source. RNA. 1997;3:950–951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Pandit S, Deutscher M P. RNase G (CafA protein) and RNase E are both required for the 5′ maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1999;18:2878–2885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin-Chao S, Cohen S N. The rate of processing and degradation of antisense RNA1 regulates the replication of ColE1-type plasmids in vivo. Cell. 1991;65:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90018-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackie G A. Specific endonucleolytic cleavage of the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20 of Escherichia coli requires the product of the ams gene in vivo and in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2488–2497. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2488-2497.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackie G A. Secondary structure of the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1054–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie G A. Ribonuclease E is a 5′-end-dependent endonuclease. Nature. 1998;395:720–723. doi: 10.1038/27246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackie G A, Genereaux J L. The role of RNA structure in determining RNase E-dependent cleavage sites in the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20 in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:998–1012. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackie G A, Genereaux J L, Masterman S K. Modulation of the activity of RNase E in vitro by RNA sequence ad secondary structures 5′ to cleavage sites. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melefors Ö, Lundberg U, von Gabain A. RNA processing and degradation by RNase K and RNase E. In: Belasco J G, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nierlich D P, Murakawa G J. The decay of bacterial messenger RNA. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1996;52:153–216. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60967-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steege D A. Emerging features of mRNA decay in bacteria. RNA. 2000;6:1079–1090. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tock M R, Walsh A P, Carroll G, McDowall K J. The CafA protein required for the 5′-maturation of 16S rRNA is a 5′-end-dependent ribonuclease that has context-dependent broad sequence specificity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8726–8732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanzo N F, Li Y S, Py B, Blum E, Higgins C F, Reynal L C, Krisch H M, Carpousis A J. Ribonuclease E organizes the protein interactions in the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2770–2781. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]