Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that the presence of oxygen is necessary for the production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) by Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. To investigate the mechanism by which oxygen might regulate toxin production, we identified homologs in S. aureus of the Bacillus subtilis resDE genes. The two-component regulatory system encoded by resDE, ResD-ResE, has been implicated in the global regulation of aerobic and anaerobic respiratory metabolism in B. subtilis. We have designated the S. aureus homologs srrAB (staphylococcal respiratory response). The effects of srrAB expression on expression of RNAIII (the effector molecule of the agr locus) and on production of TSST-1 (an exotoxin) and protein A (a surface-associated virulence factor) were investigated. Expression of RNAIII was inversely related to expression of srrAB. Disruption of srrB resulted in increased levels of RNAIII, while expression of srrAB in trans on a multicopy plasmid resulted in repression of RNAIII transcription, particularly in microaerobic conditions. Disruption of srrB resulted in decreased production of TSST-1 under microaerobic conditions and, to a lesser extent, under aerobic conditions as well. Overexpression of srrAB resulted in nearly complete repression of TSST-1 production in both microaerobic and aerobic conditions. Protein A production by the srrB mutant was upregulated in microaerobic conditions and decreased in aerobic conditions. Protein A production was restored to nearly wild-type levels by complementation of srrAB into the null mutant. These results indicate that the putative two-component system encoded by srrAB, SrrA-SrrB, acts in the global regulation of staphylococcal virulence factors, and may repress virulence factors under low-oxygen conditions. Furthermore, srrAB may provide a mechanistic link between respiratory metabolism, environmental signals, and regulation of virulence factors in S. aureus.

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of nosocomial infections worldwide (reviewed in reference 34). It is responsible for several serious diseases, including toxic shock syndrome (TSS), osteomyelitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, and septicemia, which are induced through the elaboration of a wide array of virulence factors. Numerous environmental signals have been demonstrated to act in the regulation of these virulence factors (reviewed in reference 25). Recognition of these signals likely enables S. aureus to sense appropriate host environments for coordinate expression of virulence factors. Several studies have shown that elevated oxygen, carbon dioxide, and protein levels, along with a relatively neutral pH, are required for exotoxin production by S. aureus (18, 28, 30, 39, 40). Todd et al. (35) showed that altering any of these conditions greatly reduced the synthesis of TSS toxin 1 (TSST-1) by S. aureus in vitro, and furthermore, material removed from sequestered focal infections with S. aureus contained similar components. It has also been demonstrated that insertion of a tampon raises vaginal oxygen from nearly anaerobic to aerobic conditions (37). This suggests that the addition of oxygen to the vaginal environment provides a key requirement for exotoxin production by S. aureus and may be one of the reasons for the association of tampon usage with development of TSS.

Two-component regulatory systems, consisting of a membrane sensor (histidine kinase) and a cytoplasmic response regulator, enable bacteria to sense and respond to environmental conditions even when the stimuli do not penetrate the cytoplasm. In response to an appropriate signal, autophosphorylation occurs at a conserved histidine residue in the cytoplasmic domain of the sensor. The phosphate group is then transferred to an aspartate residue on the response regulator, which in turn stimulates or represses target genes at the transcriptional level. The importance of these two-component systems, in both control of metabolism and virulence factor regulation, has been demonstrated in a wide range of bacterial species (reviewed in reference 9). The Salmonella PhoP-PhoQ system, for instance, has been shown to regulate a number of virulence factors, including envelope and outer membrane proteins that enable survival of the organism in macrophages (13). Genes regulated by the PhoP-PhoQ system respond to such signals as acidic pH and carbon, nitrogen, and phosphate starvation.

Two-component systems have also been shown to regulate virulence gene expression in S. aureus. The accessory gene regulator (agr) locus encodes a membrane sensor and response regulator pair (AgrA-AgrC), which responds to extracellular levels of an octapeptide also encoded by the agr locus and secreted by the cell (25). Once a sufficient concentration of octapeptide is present in the growing culture (usually during late exponential growth), signaling by the AgrA-AgrC system significantly upregulates the expression of the agr locus transcript RNAIII, which in turn increases expression of exotoxin genes while repressing production of surface-associated virulence factors. The sae locus is the most recently identified global regulator of virulence factors in S. aureus (12). Disruption of sae resulted in greatly decreased expression of α- and β-hemolysins, as well as coagulase. However, expression of agr was unaffected by the disruption of the sae locus. More recently, it was determined that the sae locus contains a two-component system integral to the activity of sae (11). It is possible that the response regulator of this system (SaeR) binds directly to the promoter regions of virulence factor genes, although this remains to be demonstrated.

Additional regulatory elements with possible roles in oxygen regulation of staphylococcal virulence factors include the staphylococcal accessory regulator (encoded by sarA) and the alternative sigma factor B (ςB). Chan and Foster have described a role for SarA in signal transduction in response to aeration stimuli (5). SarA normally acts to upregulate the transcription of the RNAII and RNAIII transcripts from the agr locus. However, SarA may also regulate staphylococcal virulence factors independently of agr. Deora et al. demonstrated that ςB both bound and stimulated expression of the sar P3 promoter (8). Conversely, Chan et al. showed that SarA can affect the expression of ςB by an as yet undescribed mechanism (6). The ςB homolog in Bacillus subtilis regulates a number of stress proteins in response to specific environmental stimuli, including glucose starvation, oxidative stress, or oxygen limitation (15, 16). Similar roles in environmental stress response have been identified in S. aureus, but a role in pathogenicity has not yet been identified (6).

Thus, while much has been described regarding the effects of environmental conditions on virulence gene expression in S. aureus, the mechanisms by which environmental signals affect the coordinate expression of virulence factors remain poorly understood. In the work presented here, we identify and characterize a novel two-component system in S. aureus with homology to the B. subtilis ResD-ResE system that has been implicated in the global regulation of aerobic and anaerobic respiration (reviewed in reference 23). We demonstrate that the SrrA-SrrB (staphylococcal respiratory response) two-component system regulates the production of both exotoxin and surface-associated virulence factors in response to environmental oxygen levels. The data also indicate that this regulation is mediated in part by the staphylococcal agr system and that SrrA-SrrB may act in anaerobic repression of staphylococcal virulence factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Escherichia coli was propagated on Luria-Bertani medium containing 1.5% agar. For detection of protein A and mRNA, 2 ml of Todd-Hewitt (TH) broth (Difco Laboratories, Sparks, Md.) containing appropriate selective antibiotics was inoculated with S. aureus strains to achieve an initial cell optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 (approximately 3 × 107 CFU/ml) and placed into 60- by 15-mm polystyrene petri dishes (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln, N.J.). For detection of TSST-1 production, 1 ml of TH broth containing appropriate selective antibiotics was inoculated with S. aureus strains to achieve an initial OD600 of 0.1 and placed in a 35- by 12-mm-diameter polystyrene petri dish (NUNC, Roskilde, Denmark). All cultures were then placed into sealed, humidified Plexiglas cell culture chambers (Mishell-Dutton [21]; 20 by 26 by 7.5 cm, internal dimensions), flushed with gas mixtures containing the indicated concentrations of oxygen balanced with nitrogen and 7% carbon dioxide (Praxair, St. Louis, Mo.), and sealed. Chambers were then incubated at 37°C with orbital shaking (∼125 rpm) for indicated times.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac (F′ proAB lacI ZΔM15 Tn10 [Tetr]) | Stratagene |

| S. aureus | ||

| MN8 | tstH | 4 |

| RN4220 | rK− mK+ | 19 |

| MN3050 | RN4220 (pJMY10) | This study |

| MN4000 | RN4220 srrBΩpJMY2 Emr | This study |

| MN4010 | MN4000 (pJMY10) tstH+ | This study |

| MN4011 | MN4000 (pJMY11) tstH+srrAB+ | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFW11 | 2.6 kb, Specr | 26 |

| pE194 | 3.7 kb, Emr | 14 |

| pIJ002 | Cdr Cmr | 17 |

| pJMY1 | pFW11 containing 1,014-bp XhoI-BglII PCR-amplified srrAB fragment, 3.6 kb, Specr | This study |

| pJMY2 | 1,039-bp Emr cassette PCR amplified from pE194 and cloned into KpnI site of pJMY1, 4.6 kb, Emr | This study |

| pCE104 | Shuttle vector containing pE194 and pUC18, 6.8 kb, Emr | 22 |

| pCE107 | pCE104 containing HindIII-SalI MN8 chromosomal fragment, tstH, Emr | Unpublished |

| pJMY10 | 805-bp Cmr cassette PCR amplified from pIJ002 and cloned into PstI and ScaI sites of pCE107, tstH, 5.4 kb, Cmr | This study |

| pJMY11 | 2,712-bp XmaI PCR product containing srrAB operon cloned into XmaI site of pJMY10, tstH srrAB, 8.2 kb, Cmr | This study |

Emr, erythromycin resistant; Specr, spectinomycin resistant; Cdr, cadmium resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

Identification of srrAB.

A search of the S. aureus genome database at the University of Oklahoma using a TBlastN search program (1) revealed the presence of putative homologs to the ResD-ResE two-component regulatory system that has been implicated in global regulation of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in B. subtilis (24, 33). Sequences exhibiting the greatest homology to resDE were cloned and sequenced from S. aureus MN8. Database sequences were used to construct primers for amplification and cloning of the srrAB locus.

Construction of srrB null mutant.

Genomic DNA was extracted from S. aureus MN8 and used as the template to amplify a 1,014-bp fragment containing the last 162 bp of srrA and the first 872 bp of srrB. Primers (5′-CGCCTCGAGCATTATGAATTCTATGGTGAT-3′ and 5′-CGCAGATCTTTGTCCATAATATCATTCGC-3′, Sigma-Genosys, The Woodlands, Tex.) containing the restriction enzyme recognition sequences for XhoI and BglII (underlined in primer references) and Taq polymerase were used for PCR. This fragment was digested with XhoI and BglII and cloned into pFW11. The resultant construct, pJMY1, was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. The erythromycin resistance gene from pE194 was PCR amplified using primers (5′-CGCGGTACCAGATTGTACTGAGAGTGCAC-3′ and 5′-CGCGGTACCTCAGAGCTCGTGCTATAATTA-3′) containing restriction enzyme recognition sequences for KpnI (underlined). This fragment was cloned into the KpnI site contained in the spectinomycin resistance gene of pJMY1. The resultant construct, pJMY2, was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. Construction of pJMY1 and pJMY2 was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis. pJMY2, a suicide vector, was introduced into S. aureus RN4220 via electroporation (29), and a single crossover event was selected for on TH agar plates containing erythromycin. The insertion event was confirmed by Southern blotting as well as by PCR. This single recombination event allowed for the expression of srrA but not srrB.

Construction of tstH and srrAB expression plasmids.

Plasmid pCE107, a shuttle vector containing the gene encoding TSST-1 (tstH) cloned from S. aureus MN8 (J. K. McCormick, T. J. Tripp, A. S. Llera, M. M. Dinges, R. A. Mariuzza, and P. M. Schlievert, unpublished data) was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. The chloramphenicol resistance gene from pC194 was PCR amplified using primers (5′-CGCCTGCAGTATGTTACAGTAATATTGACTTT-3′ and 5′-CGCAGTACTGACATTAGAAAACCGACTGT-3′) containing restriction enzyme recognition sequences for PstI and ScaI (underlined). This fragment was cloned into pCE107 to create pJMY10, which was transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and MN4000 by electroporation. A 2,712-bp fragment containing the entire srrAB operon was PCR amplified from a genomic DNA preparation of S. aureus MN8 using primers (5′-CGCCCCGGGATGTATTTATCACAAAGTTTGA-3′ and 5′-CGCCCCGGGATTTAATAGTTGATATTCGCAA-3′) containing restriction enzyme recognition sequences for XmaI (underlined). This fragment was cloned into the XmaI site of pJMY10 to create pJMY11, which was transformed into S. aureus MN4000 by electroporation.

Sequencing of srrAB.

A primer walking-based approach was used to sequence both strands of the 2,712-bp fragments containing the srrAB operons amplified in two independent PCRs. Sequencing was performed by the Advanced Genetic Analysis Center (University of Minnesota, St. Paul) using an ABI model 377 DNA sequencer.

Quantification of virulence factor expression.

Production of TSST-1 was quantified after ethanol precipitation of culture supernatants, resuspension of the precipitate in water, and removal of cellular debris by centrifugation, by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (10, 40).

Surface expression of protein A was quantified by flow cytometry as previously described (38). Briefly, cells from S. aureus cultures were resuspended in 1 ml of staining solution (5% fetal calf serum, 0.1% human immune serum globulin, and 0.02% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and incubated 1 h at 4°C, after which monoclonal anti-protein A-biotin conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added at a dilution of 1:1,000. After incubation for 30 min at 4°C, cells were washed twice in wash solution (2% fetal calf serum and 0.02% sodium azide in PBS), resuspended in 1 ml of staining solution, and incubated with 10 μl of phycoerythrin-labeled Extravidin (Sigma) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed once in wash solution and then twice in 0.02% sodium azide in PBS. Finally, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS, and fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton Dickinson). The negative control was not incubated with anti-protein A but was otherwise prepared as described above. Data from flow cytometry were analyzed with CellQuest (Becton Dickinson).

Detection of DNA by Southern hybridization.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from S. aureus by using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's directions. DNA was digested, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to a nylon (Nytran) membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) using standard methods (32). The DNA probe was digoxigenin labeled through PCR amplification using a DIG DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim/Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.), and hybridization and detection were performed as described by the manufacturer.

Detection of RNA by Northern hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from S. aureus strains with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's directions. Total RNA was quantified by spectrophotometric analysis (λ = 260 nm), and the same amount of RNA (2.9 μg) from each culture preparation was loaded onto two 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gels. Subsequent electrophoresis, transfer to a nylon (Nytran) membrane (Schleicher & Schuell), and detection by 32P-labeled double-stranded DNA probes were performed as described elsewhere (7). The two membranes were initially probed for the RNAIII and srrB transcripts, stripped as described elsewhere (7), and reprobed for srrA. The DNA probes were prepared by PCR amplification of fragments (300 to 500 bp) within the transcribed region of the respective genes, using the following primers: srrA, 5′-GATAGAATCAGAAGATTACT-3′ and 5′-TAAGACTACTTCTCTTGGT-3′; srrB, 5′-GAATCGCTTGCCATTGTC-3′ and 5′-CATCTATGGAACCACCATG-3′; and RNAIII, 5′-GATGTTGTTTACGATAGCT-3′ and 5′-TTCAATGGCACAAGATATC-3′). Probes were labeled with [32P]dATP (NEN, Boston, Mass) through use of a nick translation system (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) according to the manufacturer's directions. RNAIII transcript levels were quantified by densitometry analysis using NIH Image software, version 1.62 (available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence corresponding to the srrAB locus amplified from S. aureus MN8 was deposited with GenBank under accession no. AF260326.

RESULTS

Identification of srrAB.

The ResD-ResE two-component regulatory system has been implicated in the global regulation of aerobic and anaerobic respiration of B. subtilis (reviewed in reference 23). B. subtilis is not typically pathogenic, and therefore the effects of resDE mutations cannot be described in terms of their effects on virulence. However, a possible link between the S. aureus resDE homologs and virulence factor regulation could be hypothesized. resDE mutants exhibit characteristics of metabolic defects similar to those observed in staphylococcal small-colony variants (SCV), including impaired growth and resistance to aminoglycosides (23, 27). SCVs have demonstrated defects in virulence factor production, producing significantly less catalase, hemolysin, nuclease, and coagulase than wild-type S. aureus (reviewed in reference 27). In addition, it has been postulated that menaquinone is the signal recognized by the ResD-ResE system (23); defects in menaquinone synthesis are one characteristic leading to the development of the SCV phenotype. Therefore, to identify a two-component regulatory system in S. aureus that might be involved in the regulation of virulence factors in response to environmental oxygen concentrations, we conducted a search of the S. aureus 8325-4 genome database at the University of Oklahoma for genes encoding homologs to the B. subtilis ResD and ResE proteins using a TBlastN program (1). The locus predicted to encode proteins with the highest homology to ResD and ResE was selected for sequencing and characterization.

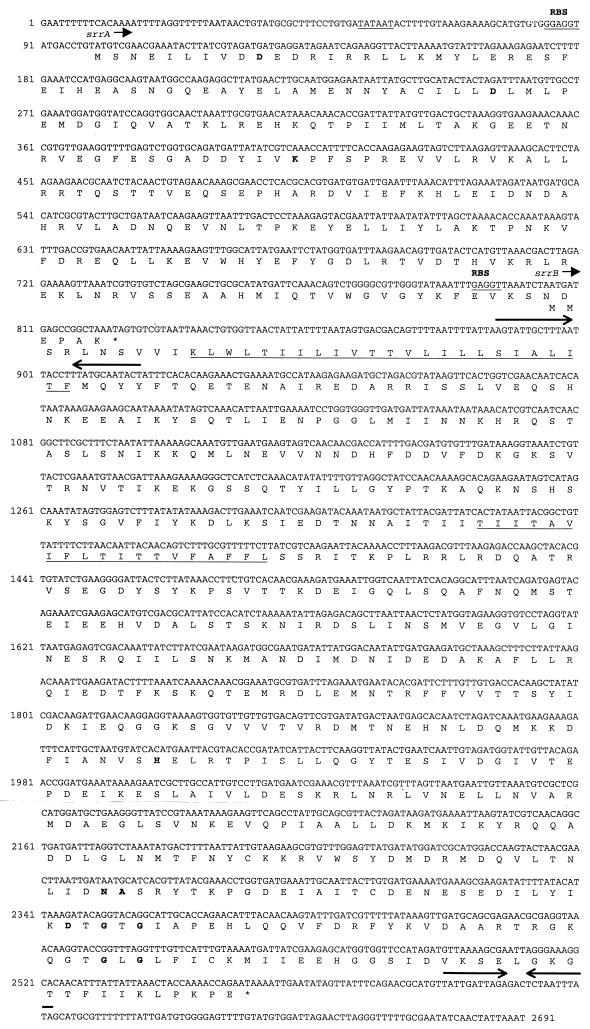

Inspection of the srrAB sequence revealed two open reading frames that overlap by 20 nucleotides, suggesting that srrA and srrB can be cotranscribed (Fig. 1). Like other two-component systems, these genes are likely to be translationally coupled when cotranscribed; the ribosome binding site for srrB lies within the 3′-terminal region of srrA. The srrA gene is 726 bp in length and is predicted to encode a 28-kDa response regulator containing 241 amino acids, while srrB is 1,752 bp in length and is predicted to encode a 66-kDa histidine kinase containing 583 amino acids. The predicted amino acid sequences of the srrAB gene products from MN8 are identical to those predicted from srrAB sequences contained in the Institute for Genomic Research and University of Oklahoma S. aureus genome sequence databases (COL and 8325-4 strains, respectively). The exception is an alanine residue predicted at amino acid position 322 in SrrB by the genome databases instead of the threonine predicted by our sequence (there were 24 nucleotide differences).

FIG. 1.

Coding-strand DNA sequence of the 2.7-kb locus containing the srrAB operon. The putative response regulator (srrA) and histidine kinase (srrB) genes are shown with the translation products given below the nucleotide sequence. The −10 (Pribnow box) consensus sequence of the putative promoter is identified, as are the potential ribosome binding sites (RBSs). Inverted repeats predicted to form stem-loop structures that may function in transcription termination are identified with bolded arrows. Regions predicted to contain transmembrane domains are indicated by underlining of the corresponding amino acids. Boldface indicates highly conserved residues likely to mediate kinase activity and phosphoryl group transfer.

The putative response regulator, SrrA, is 67% identical and 81% similar to ResD, while the S. aureus histidine kinase (SrrB) is 33% identical and 60% similar to ResE. Similar to ResE, two membrane-spanning domains are predicted from the amino acid sequence that likely anchor SrrB in the cell membrane. A hydrophilic region of approximately 160 amino acid residues lies between the membrane-spanning regions and may be exposed to the extracellular environment. Whether this region is necessary for sensing activity by SrrB remains to be determined.

While a potential −10 consensus sequence was identified from the srrAB sequence, we could not identify with any confidence a −35 consensus sequence. This is not unprecedented in S. aureus, as predicted −35 region sequences may vary widely from the commonly accepted consensus sequence of TTGACA. Downstream of srrB is a possible factor-independent transcription terminator containing both an inverted repeat predicted to form a stem-loop structure with a ΔG of −0.3 kcal/mol and a subsequent stretch of A nucleotides (in the template strand). Interestingly, a second inverted repeat motif predicted to form a stem-loop structure with a ΔG of −9.1 kcal/mol was identified downstream of the srrA open reading frame (Fig. 1).

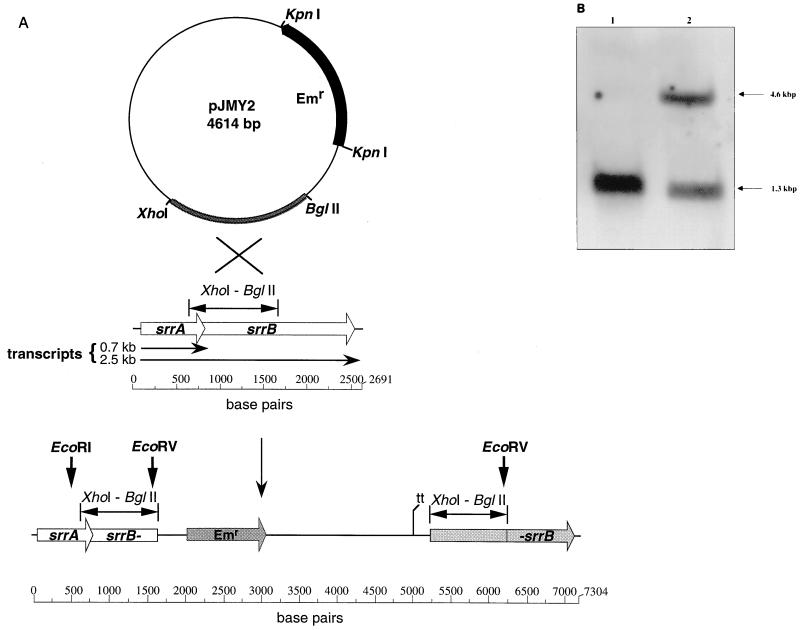

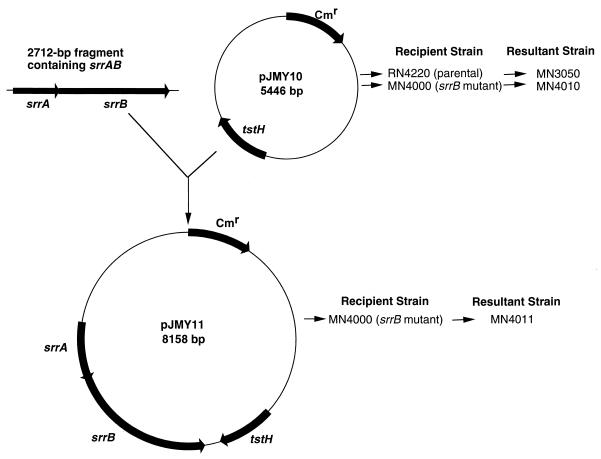

The srrB gene was insertionally inactivated in S. aureus RN4220 through a single-crossover event mediated by pJMY2 containing a 1,014-bp fragment (XhoI-BglII) of srrAB as shown in Fig. 2A. Insertion of pJMY2 was confirmed by Southern hybridization with a probe specific for the XhoI-BglII fragment (Fig. 2B). The tstH gene expressed on a multicopy plasmid (pJMY10) was electroporated into both the RN4220 parental strain and the srrB mutant to create strains MN3050 and MN4010, respectively (Fig. 3). A fragment containing the entire srrAB locus was cloned into pJMY10 to create pJMY11, which was electroporated into the srrB mutant to create MN4011. Growth and virulence factor expression of these three strains (MN3050, MN4010, and MN4011) were then characterized as described below.

FIG. 2.

(A) Disruption of srrAB by a single-crossover event between a fragment (XhoI-BglII) contained in pJMY2 and the corresponding region of srrAB in S. aureus RN4220. Recognition sites for restriction enzymes EcoRI and EcoRV are indicated. Transcripts detected by Northern blotting in the parental strain (MN3050) are indicated. Abbreviations: Emr, erythromycin resistance cassette; tt, transcription terminator. (B) Southern hybridization of chromosomal digests (EcoRI and EcoRV) of the parental strain (lane 1) and srrB mutant (lane 2) with a probe specific to the XhoI-BglII fragment. Band sizes are indicated at the right.

FIG. 3.

Construction of plasmids and strains used in this study for characterization of srrAB. The tstH gene was expressed in both parental and srrB mutant strains via electroporation of pJMY10; the srrAB and tstH genes were expressed in trans in the srrB mutant by electroporation of pJMY11. Abbreviations: Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance cassette.

Growth of S. aureus strains.

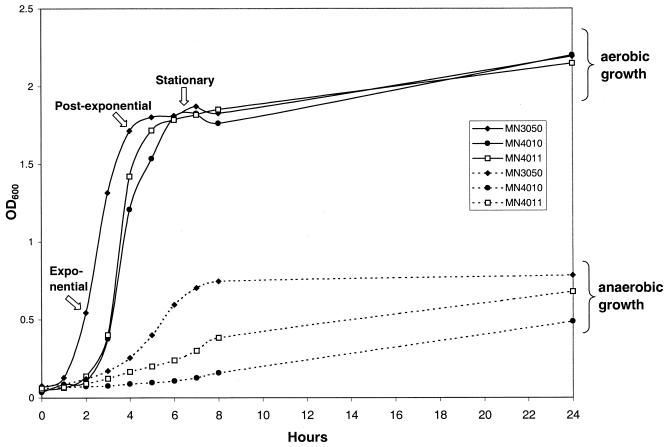

Representative growth curves in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions for the three strains characterized in this study are shown in Fig. 4. All three strains grew similarly in aerobic conditions. Growth of the srrB mutant, however, was significantly slower than that of the parental strain in anaerobic conditions, whereas expression of srrAB in trans resulted in an intermediate growth phenotype. It should be noted that under the microaerobic conditions used in this study (1 to 2% [vol/vol] oxygen) no significant difference in growth between the mutant and parental strains was observed.

FIG. 4.

Growth of S. aureus strains in TH broth incubated with shaking at 37°C in either anaerobic or aerobic conditions. OD600 was used to determine growth of cultures. Stages of growth at which gene expression were assayed are indicated for the parental strain (MN3050).

Gene expression profiles.

RNA was extracted from S. aureus strains at equivalent stages of growth under microaerobic and aerobic conditions and examined for expression of srrA, srrB, and RNAIII (Fig. 5). Growth stages included the exponential, postexponential (the transition from exponential- to stationary-phase growth), and stationary phases of growth. These stages occurred approximately 1, 3, and 5.5 h after entry into the exponential growth phase, respectively, as shown for the parental strain in Fig. 4. Microaerobic conditions were chosen for study of the S. aureus response to oxygen levels, as growth rates and cell densities are much lower in cultures incubated in completely anaerobic conditions. Thus, anaerobic growth complicates interpretation of data, as cultures may not reach cell densities sufficient to activate the agr system and exotoxin gene expression.

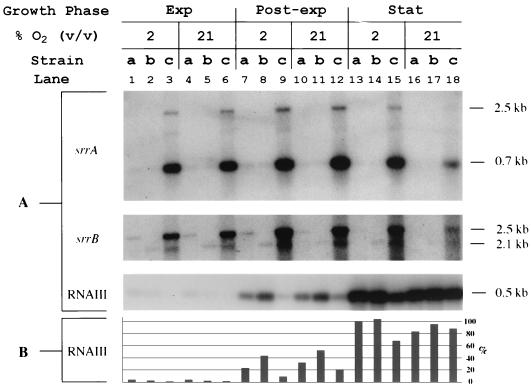

FIG. 5.

Northern hybridization of total RNA extracted from S. aureus strains at equivalent cell densities (as determined by OD600). RNA was harvested from exponential (Exp)-, post exponential (Post-exp)-, and stationary (Stat)-phase cultures incubated in atmospheres containing 2 or 21% (vol/vol) oxygen balanced with nitrogen and 7% carbon dioxide. Equivalent amounts (2.9 μg) of total RNA were loaded onto each lane, processed as described in Materials and Methods, and assayed for expression of srrA, srrB, and RNAIII. Strains: a, MN3050 (parental strain); b, MN4010 (srrB mutant); c, MN4011 (srrB mutant expressing srrAB in trans). (A) Northern hybridizations for srrA, srrB, and RNAIII. Band sizes are indicated at the right. (B) Amount of RNAIII transcript as determined by densitometric analysis. Bars represent percentage of maximum wild-type RNAIII transcript (lane 13) detected.

Both srrA and srrB were expressed by the parental strain (MN3050) at detectable levels during exponential and postexponential phases of growth in both microaerobic and aerobic conditions (Fig. 5, lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10). Expression of srrA and srrB by MN3050, however, was only weakly detectable during the stationary growth phase, particularly in aerobic conditions (Fig. 5, lanes 13 and 16). The srrA gene was expressed on a transcript estimated to be 0.7 kb and, to a much lesser extent, on a 2.5-kb transcript. In contrast, srrB was expressed on the 2.5-kb transcript only. (transcript locations are indicated in Fig. 2A). This suggests that srrA can be transcribed independently of srrB, while srrB cannot be transcribed independently of srrA. A transcript of appropriate size did not appear in those lanes containing RNA from the srrB null mutant (MN4010), indicating disruption of srrB expression. However, at least a portion of srrB appeared to be transcribed as part of the 2.1-kb fragment detected in MN4010. Transcription of this fragment may be driven by a promoter contained within the integrated plasmid, despite the presence of a transcription terminator upstream of srrB in the insertional mutant. The evidence presented in this report, however, suggests that expression of SrrB is indeed disrupted, though likely at the level of translation. In MN4011, srrAB, together with its putative promoter, was expressed in trans in the srrB null mutant on a multicopy plasmid (pJMY11). As expected, srrAB expression in this strain was much greater than in the parental strain (MN3050).

Additional observations can be made from Fig. 5. The increased amounts of the truncated, chromosomal transcript of srrB (2.1-kb band) when srrAB (2.5-kb band) was overexpressed via the multicopy plasmid suggested that the srrAB locus can upregulate its own expression in a positive-feedback type of mechanism (Fig. 5, lanes 9 and 12, srrB). Also, oxygen appeared to affect the concentration of srrAB in MN3050; srrAB was upregulated under microaerobic conditions compared to aerobic conditions in both the postexponential and stationary phases of growth (lanes 7, 10, 13, and 16). The effects of both growth phase and oxygen concentration were greater in MN4011 than in MN3050. The expression of srrAB was greatest during the postexponential phase of growth, particularly under microaerobic conditions (lanes 9 and 12). Also, expression of srrAB during the stationary phase of growth was significantly greater in microaerobic than aerobic conditions (lanes 15 and 18).

An inverse relationship between srrAB expression and the expression of RNAIII, the effector molecule produced by the agr locus, was observed during the postexponential phase of growth. While RNAIII was expressed in the parental strain (Fig. 5, lanes 7 and 10), disruption of srrB resulted in increased expression of RNAIII (lanes 8 and 11). When srrAB was overexpressed, however, RNAIII expression was reduced to levels below that seen in the parental strain, particularly in microaerobic conditions (lanes 9 and 12). RNAIII expression in MN4011 during postexponential-phase growth was greater in aerobic than microaerobic conditions; this appeared to correlate with a decrease in srrAB expression under aerobic conditions rather than a direct effect of increased oxygen concentration (lanes 9 and 12). Much greater expression of RNAIII was detected during the stationary phase of growth, with the only significant repression of RNAIII occurring when srrAB was overexpressed (lane 15). No effect of oxygen on the expression of the RNAIII molecule in the parental strain could be detected in either the postexponential or stationary phase of growth (lanes 7, 10, 13, and 16).

Production of TSST-1.

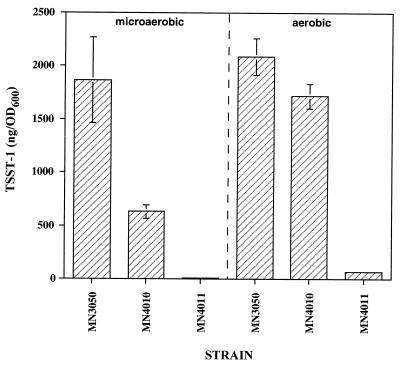

To determine the effect of srrAB expression on production of exotoxin, TSST-1 concentrations were quantified in cultures of S. aureus strains (Fig. 6). Disruption of srrB expression (MN4010) significantly (66%) downregulated production of TSST-1 in microaerobic conditions, even though RNAIII expression was upregulated in these conditions. In aerobic conditions, TSST-1 production by MN4010 was decreased by only 18% compared to the parental strain, MN3050. Interestingly, overexpression of srrAB in strain MN4011 further suppressed TSST-1 production to nearly undetectable levels in both microaerobic and aerobic oxygen conditions (100 and 97% reductions, respectively, compared to the parental strain). This appeared to correlate with the repression of RNAIII expression in MN4011.

FIG. 6.

TSST-1 concentrations in cultures incubated for 24 h in microaerobic (1% [vol/vol] oxygen or aerobic (21% [vol/vol] oxygen) atmospheres balanced with nitrogen and 7% carbon dioxide. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate ELISA readings for each culture. Toxin production was measured in three independent sets of cultures with highly similar results.

Production of protein A.

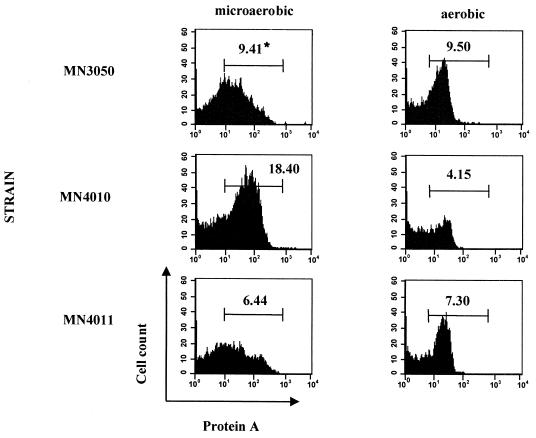

Expression of srrAB also had a demonstrable effect on the expression of the prototypic surface molecule of S. aureus, protein A (Fig. 7). The expression of protein A was downregulated in the srrB null mutant (MN4010) under aerobic conditions, consistent with the upregulation of RNAIII in this strain. Under microaerobic conditions, however, protein A expression was upregulated compared to the parental strain. Expression of srrAB in trans (MN4011) restored protein A production to nearly wild-type levels in both conditions. The effect of srrB disruption or overexpression was discernible only during the postexponential phase of growth; there was no significant difference in protein A expression in the three strains examined in the exponential or stationary phase of growth.

FIG. 7.

Expression of cell surface protein A in various growth stages of cultures incubated in microaerobic (1% [vol/vol] oxygen) or aerobic (21% [vol/vol] oxygen) atmospheres balanced with nitrogen and 7% carbon dioxide. Cells from cultures at equivalent stages of growth were harvested and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Cells exhibiting low forward and side-scatter profiles were gated for analysis to avoid detecting protein A expression on clusters of cells. Protein A production was measured in three independent sets of cultures with highly similar results. ∗, percentage of total events (50,000) detected by the flow cytometer that fall into the range of fluorescence, and thus protein A production, delineated by the marker.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of environmental signals in control of staphylococcal virulence factors (25). Signals including catabolite or osmolyte concentrations, presence of autoinducing peptides, and pH are all capable of regulating production of exotoxins as well as surface proteins. In particular, anaerobic conditions and low carbon dioxide levels repress production of exotoxins by S. aureus clinical isolates (28, 40). It is likely that many environmental effects on virulence factors are mediated by components of the respiratory system, as genetic evidence suggests that mobile genetic elements encoding virulence factor genes (e.g., pathogenicity islands) were imposed upon an existing metabolic system. Indeed, defects in respiratory metabolism, typified by the SCV phenotype, have demonstrable effects on expression of virulence factors (27). However, though much has been described regarding the effects of environmental signals and respiratory defects on staphylococcal virulence, very little is known about the mechanism by which these signals effect their regulation of virulence factors. In the work described here, we identify a novel two-component regulatory system, SrrA-SrrB, which we propose may provide a link between respiratory metabolism, environmental signals, and regulation of virulence factors in S. aureus.

Several observations suggest that the SrrA-SrrB system may function in respiratory metabolism similarly to the ResD-ResE system in B. subtilis. A high degree of homology exists between the predicted amino acid sequences of SrrA-SrrB and ResD-ResE, with the response regulators being 68% identical. Furthermore, open reading frames encoding the membrane sensor and response regulator overlap in both of these systems, suggesting translational coupling of the proteins when the genes are cotranscribed. The two predicted transmembrane regions of SrrB closely align with those predicted in ResE. Finally, the srrB mutant grows much more slowly in anaerobic conditions than does the parental strain; B. subtilis resDE mutants are also defective in anaerobic growth, particularly in nitrate-deficient medium.

Interestingly, analysis of the transcript lengths as determined by Northern analysis of srrAB transcription (Fig. 5) indicated that srrA can be transcribed independently of srrB (0.7-kb transcript), while srrB must be cotranscribed with srrA (2.5-kb transcript). To our knowledge, this is relatively uncommon among two-component regulatory systems. Expression of srrA via the 2.5-kb transcript in the parental strain, MN3050, was detected but was difficult to reproduce in Fig. 5. Instead, srrA mRNA is detectable as a transcript estimated to be 0.7 kb in MN3050, particularly in lanes 4 and 7 of Fig. 5. However, the definite presence of a 2.5-kb band corresponding to srrA in the complemented strain, MN4011, demonstrates that srrA and srrB can indeed be cotranscribed, though as a relatively small portion of total srrA transcript. It is possible that the stem-loop structure predicted to form downstream of srrA (Fig. 1) partially prevents transcription of the full-length transcript. Alternatively, this stem-loop structure may prevent complete 3′-5′ endonuclease digestion of the srrAB transcript, thus leaving higher levels of srrA mRNA than srrAB mRNA in the cell.

The srrAB locus also appeared to be capable of upregulating its own expression (Fig. 5). When srrAB was expressed in trans on a multicopy plasmid (MN4011), levels of the 2.1-kb partial transcript of srrAB expressed from the chromosome were higher than those in the uncomplemented srrB mutant (MN4010). Despite the presence of this 2.1-kb transcript containing at least a portion of srrB in MN4010 (perhaps driven by a promoter contained within the integrated plasmid), the mutation has a clear phenotype that is complementable. This suggests that expression of SrrB is indeed disrupted, although likely at the level of translation.

The data presented here indicate that SrrA-SrrB acts in the global regulation of staphylococcal virulence factors, although this role is partially independent of the primary global regulator, agr. The production of both secreted and cell surface virulence factors was altered by disruption of srrB, while overexpression of the system greatly repressed exotoxin production and restored protein A expression to nearly wild-type levels. Transcription of RNAIII was inversely dependent on expression of srrAB, as upregulation of srrAB expression resulted in decreased expression of RNAIII. While RNAIII levels were upregulated in the srrB mutant, however, production of TSST-1 decreased. On the other hand, when RNAIII levels were repressed through the overexpression of the two-component system, production of TSST-1 was greatly reduced. Furthermore, while significant levels of RNAIII are present in all the cultures at stationary phase, very little toxin was made when srrAB is overexpressed. These observations confirm the hypothesis that factors in addition to RNAIII are required for expression of exotoxin genes (25).

The data further suggest that SrrA-SrrB may normally act during anaerobic conditions to suppress expression of virulence genes. The repression of TSST-1 by overexpression of srrAB was most complete in microaerobic conditions. When expressed in trans, transcription of the system itself was detectably increased in microaerobic conditions. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that SrrA-SrrB and ResD-ResE may have similar functions in S. aureus and B. subtilis, respectively. The expression of both resD and resE is significantly greater in anaerobic than aerobic conditions (41), and the ResD-ResE system activates a number of genes in response to anaerobic conditions (23, 24, 33). It is not entirely clear, however, why the disruption of srrB results in an intermediate phenotype between expression of exotoxin in the parental strain and in the srrAB-overexpressing strain, even though RNAIII levels are increased in the srrB mutant. It is possible that repression of toxin production in the mutant was due to a metabolic defect in the mutant that limited energy gain or amino acid uptake necessary for toxin production in microaerobic conditions, whereas the reduction in TSST-1 production in the strain overexpressing srrAB might have been due, in part, to repression of RNAIII transcription. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the reduction of TSST-1 production by the srrB mutation was much greater in microaerobic than aerobic conditions. In addition, the srrB mutant exhibited significantly slower growth in completely anaerobic conditions, suggesting that this strain has metabolic or respiratory defects that may prevent synthesis of extraneous proteins, such as exotoxins, in microaerobic or anaerobic conditions. However, the possibility that expression of srrAB in trans represses toxin production by a mechanism independent of agr cannot be ruled out.

Several observations suggest similarities between staphylococcal SCVs and resDE and srrB mutants grown anaerobically. Growth of all of these strains was significantly slower than in the parental or wild-type strains. Defects in respiratory metabolism that lead to the SCV phenotype, such as menadione auxotrophy, also result in reduced production of exotoxins, including hemolysin and catalase (27). B. subtilis resDE mutants exhibit a number of metabolic defects as well, including acid accumulation when grown with glucose as a carbon source, lack of aa3 or caa3 terminal oxidase production, and the loss of ability to grow anaerobically on a nitrate-containing medium (33). B. subtilis resDE mutants are resistant to aminoglycosides, as are SCVs, suggesting disrupted transmembrane potentials in both types of mutants. Interestingly, it has been suggested that reduced menaquinone, of which menadione is the precursor molecule, is the signal to which ResD-ResE responds (23). Should this prove to be the case for both ResD-ResE and SrrA-SrrB, it is possible that this system mediates the repression of virulence factors observed in the menadione auxotrophs. Oxygen is directly implicated in this regulatory system, as anaerobic growth of S. aureus partially replicates the SCV phenotype, and SCVs have been observed to use less oxygen during growth (27).

Two-component regulatory systems have recently attracted interest as possible targets for antimicrobial chemotherapy (3). Indeed, compounds that inhibit signal transduction through these systems have been shown to be effective even against multi-drug-resistant pathogens, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (2, 20). The data presented here suggest that manipulation of SrrA-SrrB in S. aureus may suppress production of exotoxins. It has been shown that the presence of glycerol monolaurate can significantly reduce the amount of toxin produced in culture or when applied to tampons while having only weak antimicrobial action (31). A possible mechanism of glycerol monolaurate, which acts at the lipid-water interface, is to interfere with the activity of the membrane-bound sensor proteins. Inhibition of toxin production would reduce systemic disorders in patients while helping to prevent further spread of the organism. Treatment combining drugs that interfere with staphylococcal environmental sensing mechanisms with standard antibiotics may provide an effective two-pronged approach by quickly eliminating toxin production and clearing the organism from the patient.

The results obtained in this study indicate that the oxygen response that our laboratory described in MN8 (40) is not completely replicated in RN4220, a derivative of strain 8325-4. Exotoxin production by RN4220 is not subject to the same level of repression in low-oxygen conditions as observed in the clinical isolate. One possible explanation for this is a lack of the complete ςB factor operon in RN4220 (or 8325-4) (36). The deletion in 8325-4 was predicted to result in a 70-amino-acid truncation of the encoded RsbU protein, which is necessary for stress-induced activation of ςB but not for activation of ςB during the stationary phase of growth. Simple strain variation may also account for the oxygen response described here. Further characterization of SrrA-SrrB by our lab will focus on its role in virulence of clinical isolates, which may be even more significant than suggested by our data. Regardless, our data strongly implicate this two-component system in the regulation of virulence factors in S. aureus, including interaction with the primary global regulator, agr. It is likely that additional studies of this system will yield valuable insights as to how environmental conditions and respiratory defects affect virulence of this organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a research grant from The Procter and Gamble Co. and research grant AI22159 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J.M.Y. was supported by a Howard Hughes Predoctoral Fellowship in the Biological Sciences. We gratefully acknowledge the Staphylococcus aureus Genome Project and B. A. Roe, A. Dorman, F. Z. Najar, S. Clifton and J. Iandolo, with funding from the NIH and the Merck Genome Research Institute.

We thank Jodi Capistrant for technical assistance and Michael Kim for assistance with Northern hybridizations. We are also grateful for methods provided by Malcolm Horsbaugh and Simon Foster as well as assistance from Chris Waters and Marc Jenkins with flow cytometry. We thank Patrick Cleary for provision of plasmid and Tim Leonard for assistance with preparation of figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett J F, Goldschmidt R M, Lawrence L E, Foleno B, Chen R, Demers J P, Johnson S, Kanojia R, Fernandez J, Bernstein J, Licata L, Donetz A, Huang S, Hlasta D J, Macielag M J, Ohemeng K, Frechette R, Frosco M B, Klaubert D H, Whiteley J M, Wang L, Hoch J A. Antibacterial agents that inhibit two-component signal transduction systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5317–5322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett J F, Hoch J A. Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1529–1536. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomster-Hautamaa D A, Schlievert P M. Preparation of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. Methods Enzymol. 1988;165:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)65009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan P F, Foster S J. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6232–6241. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6232-6241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan P F, Foster S J, Ingham E, Clements M O. The Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor ςB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6082–6089. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6082-6089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis L G, Kuehl W M, Battey J F. Basic methods in molecular biology. 2nd ed. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deora R, Tseng T, Misra T K. Alternative transcription factor ςSB of Staphylococcus aureus: characterization and role in transcription of the global regulatory locus sar. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6355–6359. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6355-6359.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziejman M, Mekalanos J J. Two-component signal transduction and its role in expression of bacterial virulence factors. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 305–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed R C, Evenson M L, Reiser R F, Bergdoll M S. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of staphylococcal enterotoxins in foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:1349–1355. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.6.1349-1355.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giraudo A T, Calzolari A, Cataldi A A, Bogni C, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus encodes a two-component regulatory system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giraudo A T, Cheung A L, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus controls exoprotein synthesis at the transcriptional level. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groisman E A, Heffron F. Regulation of Salmonella virulence by two-component regulatory systems. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 319–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gryczan T J, Grandi G, Hahn J, Grandi R, Dubnau D. Conformational alteration of mRNA structure and the posttranscriptional regulation of erythromycin-induced drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:6081–6097. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.24.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecker M, Schumann W, Voelker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecker M, Voelker U. General stress proteins in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;74:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson M P, Iandolo J J. Cloning and expression of the exfoliative toxin B gene from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:574–580. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.574-580.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kass E H, Kendrick M I, Tsai Y C, Parsonnet J. Interaction of magnesium ion, oxygen tension, and temperature in the production of toxic-shock-syndrome toxin-1 by Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:812–815. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreiswirth B N, Lofdahl S, Betley M J, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P M, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macielag M J, Demers J P, Fraga-Spano S A, Hlasta D J, Johnson S G, Kanojia R M, Russell R K, Sui Z, Weidner-Wells M A, Werblood H, Foleno B D, Goldschmidt R M, Loeloff M J, Webb G C, Barrett J F. Substituted salicylanilides as inhibitors of two-component regulatory systems in bacteria. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2939–2945. doi: 10.1021/jm9803572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishell B B, Mishell R I. Primary immunization in suspension cultures. In: Mishell B B, Shiigi S M, editors. Selected methods in cellular immunology. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman & Company; 1980. pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray D L, Earhart C A, Mitchell D T, Ohlendorf D H, Novick R P, Schlievert P M. Localization of biologically important regions on toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Infect Immun. 1996;64:371–374. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.371-374.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano M M, Zuber P. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis) Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano M M, Zuber P, Glaser P, Danchin A, Hulett F M. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3796–3802. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3796-3802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick R P. Pathogenicity factors and their regulation. In: Fischetti V A, Novick R P, Ferretti J J, Portnoy D A, Rood J I, editors. Gram-positive pathogens. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podbielski A, Spellerberg B, Woischnik M, Pohl B, Lutticken R. Novel series of plasmid vectors for gene inactivation and expression analysis in group A streptococci (GAS) Gene. 1996;177:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)84178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proctor R. Respiration and small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. In: Fischetti V A, Novick R P, Ferretti J J, Portnoy D A, Rood J I, editors. Gram-positive pathogens. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross R A, Onderdonk A B. Production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 by Staphylococcus aureus requires both oxygen and carbon dioxide. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5205–5209. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5205-5209.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schenk S, Laddaga R A. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;73:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90596-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlievert P M, Blomster D A. Production of staphylococcal pyrogenic exotoxin type C: influence of physical and chemical factors. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:236–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlievert P M, Deringer J R, Kim M H, Projan S J, Novick R P. Effect of glycerol monolaurate on bacterial growth and toxin production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:626–631. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun G, Sharkova E, Chesnut R, Birkey S, Duggan M F, Sorokin A, Pujic P, Ehrlich S D, Hulett F M. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1374–1385. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1374-1385.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenover F C, Gaynes R P. The epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infections. In: Fischetti V A, Novick R P, Ferretti J J, Portnoy D A, Rood J I, editors. Gram-positive pathogens. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todd J K, Todd B H, Franco-Buff A, Smith C M, Lawellin D W. Influence of focal growth conditions on the pathogenesis of toxic shock syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:673–681. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voelker U, Voelker A, Maul B, Hecker M, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Separate mechanisms activate sigma B of Bacillus subtilis in response to environmental and metabolic stresses. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3771–3780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3771-3780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner G, Bohr L, Wagner P, Petersen L N. Tampon-induced changes in vaginal oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(84)80165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wann E R, Fehringer A P, Ezepchuk Y V, Schlievert P M, Bina P, Reiser R F, Hook M M, Leung D Y. Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with Kawasaki disease express high levels of protein A. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4737–4743. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4737-4743.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong A C, Bergdoll M S. Effect of environmental conditions on production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1026–1029. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1026-1029.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yarwood J M, Schlievert P M. Oxygen and carbon dioxide regulation of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus MN8. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1797–1803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1797-1803.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye R W, Tao W, Bedzyk L, Young T, Chen M, Li L. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4458–4465. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4458-4465.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]