Abstract

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) initiatives promote the responsible use of antimicrobials in healthcare settings as a key measure to curb the global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Defining the core elements of AMS is essential for developing and evaluating comprehensive AMS programmes. This project used co-creation and Delphi consensus procedures to adapt and extend the existing published international AMS checklist. The overall objective was to arrive at a contextualised checklist of core AMS elements and key behaviours for use within healthcare settings in Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as to implement the checklist in health institutions in four African countries. The AMS checklist tool was developed using a modified Delphi approach to achieve local expert consensus on the items to be included on the checklist. Fourteen healthcare/public health professionals from Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, Ghana and the UK were invited to review, score and comment on items from a published global AMS checklist. Following their feedback, 8 items were rephrased, and 25 new items were added to the checklist. The final AMS checklist tool was deployed across 19 healthcare sites and used to assess AMS programmes before and after an AMS intervention in 14 of the 19 sites. The final tool comprised 54 items. Across the 14 sites, the completed checklists consistently showed improvements for all the AMS components following the intervention. The greatest improvements observed were the presence of formal multidisciplinary AMS structures (79%) and the execution of a point-prevalence survey (72%). The elements with the least improvement were access to laboratory/imaging services (7%) and the presence of adequate financial support for AMS (14%). In addition to capturing the quantitative and qualitative changes associated with the AMS intervention, project evaluation suggested that administering the AMS checklist made unique contributions to ongoing AMS activities. Furthermore, 29 additional AMS activities were reported as a direct result of the prompting checklist questions. Contextualised, co-created AMS tools are necessary for managing antimicrobial use across healthcare settings and increasing local AMS ownership and commitment. This study led to the development of a new AMS checklist, which proved successful in capturing AMS improvements in Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Ghana. The tool also made unique contributions to furthering local AMS efforts. This study extends the existing AMS materials for low- and middle-income countries and provides empirical evidence for successful use in practice.

Keywords: AMS checklist, antimicrobial prescribing, CwPAMS, Global-PPS, antimicrobial stewardship

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) has been recommended as a key strategy for optimising the use of antimicrobials and reducing the global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [1]. AMS programmes have evolved in different healthcare settings [2,3,4], but most relevant research has been conducted in high-income countries, whose healthcare systems are supported by a political commitment to AMS and substantial financial investments [4]. Learning from high-income countries needs to be shared and adapted for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The initial successes provide evidence for the effectiveness of shared learning approaches [1,5,6,7,8,9,10]. A key requirement for the success of shared learning appears to be the engagement and empowerment of frontline staff, who need to be equipped with the skills and tools to carry out AMS effectively.

In 2019, Pulcini et al. [11] developed a global checklist of the core elements of hospital AMS programmes. The checklist collates information from published literature, the previously developed core elements of AMS programmes, and their accompanying checklist items. However, the authors themselves identified a number of shortcomings of their tool, for example, stating ‘… most of these checklist items may not currently exist in most hospitals in low-income countries’ and suggesting ‘These seven core elements and their related 29 checklist items could be adapted and adopted locally depending on factors such as clinical setting and resource availability’ [11] p. 23. Subsequent efforts have addressed these suggestions and focused on developing more appropriate materials for the LMIC context [12]. In October 2019, the WHO published a toolkit of essential national core elements for AMS programmes in LMICs. This was supplemented by a 28-item checklist of essential healthcare facility core elements for AMS programmes in LMICs, differentiating between the ‘basic’ and ‘advanced’ elements [12]. The development of materials for LMIC healthcare settings was an initial step toward more contextualised AMS approaches.

This study takes another step toward increasing the suitability and acceptance of standardised AMS tools in LMIC settings in several different ways:

-

(1)

Our focus on Sub-Saharan Africa (specifically Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Ghana) offers a further local adaptation of the materials.

-

(2)

Our unique methodological approach uses elements of co-creation through the strong involvement of local hospital representatives during a Delphi consensus procedure.

-

(3)

We extended the number of checklist items to capture the more nuanced differences in the AMS elements. Additionally, we incorporate open-ended questions within the AMS checklist to allow for more reporting flexibility.

-

(4)

We provide an initial evaluation of the checklist’s effectiveness by using it to measure the outcomes of an AMS intervention programme.

The checklist was developed as part of the ‘Commonwealth Partnerships for Antimicrobial Stewardship’ (CwPAMS) programme, funded by UK aid Fleming Fund and jointly managed through the Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET) and the Commonwealth Pharmacists Association (CPA) [13,14,15,16]. The CwPAMS programme ran from inception in September 2018 until June 2021 and was set up to support 12 health partnerships between teams of volunteers (including pharmacists and specialist nurses) from the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) Trusts and higher education institutes and health workers in four African countries (Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Ghana). The CwPAMS programme provided the perfect setting for developing the AMS checklist because the existing project infrastructure enabled the easy identification of representative healthcare workers to be included in the consensus process. Given CwPAMS’ efforts in running AMS interventions, the project further allowed us to test the success of the newly developed checklist.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Checklist Development

Pulcini et al.’s [11] global AMS checklist served as the baseline document for our project. The WHO’s AMS toolkit for LMICs had not been published at that time. Using Pulcini et al.’s original items as a starting point, we adopted a modified Delphi procedure for achieving a consensus on the items to be included in our contextualised AMS checklist for the Sub-Saharan healthcare context. The consensus procedure involved rating the importance of items as well as making open-ended comments and suggestions. The CwPAMS project structure was used to engage local hospital representatives across four countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

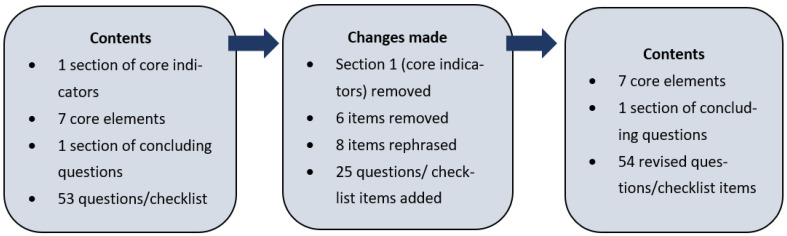

Fourteen healthcare representatives from the CwPAMS partnerships were invited from April 2019 to participate in the consensus process following the project inception training sessions with all the UK and African partnership leads involved in the CwPAMS project. The 14 representatives included eight CwPAMS health partnership leads, including pharmacists, public health specialists, and microbiologists from the UK and the four African countries, four healthcare professionals working in hospitals, national pharmacy and/or public health associations based in Ghana, and two healthcare professionals based in Uganda (working in a regional referral hospital and national research institute). The consensus process is summarised in Figure 1. Further details on the consensus process and the development of the AMS checklist are included in Supplementary Materials S1 to S3.

Figure 1.

Summary of consensus process.

2.2. AMS Checklist Implementation across 19 Hospitals

Following a pilot with two partnership sites, the final AMS checklist was deployed as an online form in April 2019 across 19 sites in Sub-Saharan Africa, which included 14 CwPAMS project sites (6 Ghana, 6 Uganda, 1 Tanzania and 1 Zambia) and 5 regional referral centres in Uganda. Each hospital site provided information on the current state of their AMS activities based on the questions on the checklist. For the CwPAMS sites, the checklist was jointly completed through discussions between the respective UK and African lead partners. To facilitate this, a PDF or spreadsheet version of the checklist was made available. For the additional sites in Uganda, the pharmacists at each institution completed the checklist with support from independent colleagues with AMS expertise to discuss and complete the form with relevant individuals. The lead African and UK partners for each CwPAMS site completed the checklist again to provide updated information on the state of their AMS activities post-CwPAMS intervention. The respondents were also asked to include information on the members of their multidisciplinary AMS teams pre- and post-CwPAMS intervention.

2.3. Demographics of Study Sites

Across the 19 study sites, the hospitals averaged 536 inpatient beds, with the lowest number of hospital beds reported as 100 and the highest as 2000 inpatient beds (both in Ghana). Eight out of nineteen hospitals (42%) were tertiary hospitals, five (26%) were secondary hospitals, and five (26%) were regional referral hospitals. Only one site (5%) was a primary care institution. Twelve out of nineteen sites (63%) were teaching hospitals. The names of all participating hospital sites can be found in Supplementary Material S3.

3. Results

The final AMS checklist contained 54 items across eight main sections (Supplementary Material S2). These included seven sections on the core elements of hospital AMS programmes (senior management and leadership towards AMS; accountability and responsibilities; available expertise on infection management and stewardship; education and practical training; continual monitoring and surveillance; regular reporting and feedback; other actions aiming at responsible antimicrobial use) and the concluding section. It differed from the original checklist by Pulcini et al. [11] in several important ways.

The new items added: 24 new items were added to Pulicini et al.’s [11] original checklist. Most items were added in the sub-sections on accountability and responsibilities, education and practical training, and other actions aiming at responsible antimicrobial use. The added items reflected a stronger focus on the details around the AMS team, a more detailed assessment of induction training for clinical staff, and questions around local prescribing and the Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) protocols. The new items also included different question formats compared to Pulcini et al.’s [11] binary choice questions. The examples were open-ended questions (e.g., ‘Please provide more details about the AMS leader, and how much time is available to dedicate to AMS activities etc.’). Numerical questions (e.g., ‘What was the total number of each clinical staff trained in the last year’) and multiple-choice questions (e.g., ‘How is the training delivered? (Select all that apply)’) were also asked.

The items removed: Eight items were removed from the original checklist. Almost all of these items were part of the section on other actions aiming at responsible antimicrobial use. Item removal was determined by their relevance to Sub-Saharan healthcare settings and the limited availability of resources. An example of a deleted item includes: ‘Does your hospital support the antimicrobial stewardship activities/strategy with adequate information technology services?’

The items rephrased: Eight original checklist items were rephrased to increase understanding and better reflect the local healthcare contexts. For example, the original question ‘Are clinicians, other than those part of the antimicrobial stewardship team (e.g., from the ICU, Internal Medicine and Surgery) involved in the antimicrobial stewardship committee?’ was extended. The new question was phrased: (i.e., ‘Are clinicians, nurses or pharmacists, other than those part of the AMS team …’) to specifically include a focus on nurses and pharmacists.

3.1. Checklist Implementation

Quantitative Improvements Following the AMS Intervention

Table 1 shows a comparison of the core checklist results pre and post the CwPAMS AMS strengthening intervention, delivered through the partnerships. The five additional sites in Uganda (without the CwPAMS project interventions) only completed the checklist once and are therefore excluded from this comparison. Their checklist results can be found in a separate table in Supplementary Material S4.

Table 1.

Comparison of selected AMS checklist results pre- and post-AMS intervention that formed part of the CwPAMS projects. The numbers indicate the total number of sites that agreed with the item in question. Percentages (out of 14 sites) are provided alongside the numbers. The final column shows post-intervention improvement through the percentage increase.

| Pre-AMS Intervention N = 14 |

Post-AMS Intervention N = 14 |

Percentage Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has your hospital management formally identified AMS as a priority objective for the institution and included it in its key performance indicators? | 2 | 14% | 10 | 71% | +57% |

| Is there dedicated, sustainable and sufficient budgeted financial support for AMS activities (e.g., support for salary, training, or IT (information technology) support)? | 1 | 7% | 3 | 21% | +14% |

| Does your hospital have a formal organisational multidisciplinary structure responsible for AMS? | 3 | 21% | 14 | 100% | +79% |

| Does your hospital have a dedicated committee focussed on antimicrobial use? | 2 | 14% | 8 | 57% | +43% |

| Is there a healthcare professional identified as a leader for AMS activities at your hospital and responsible for implementing the programme? | 4 | 29% | 12 | 86% | +57% |

| Is a multidisciplinary AMS team available at your hospital (e.g., greater than one trained staff member supporting clinical decisions to ensure appropriate antimicrobial use) to implement your stewardship strategy? | 1 | 7% | 10 | 71% | +64% |

| Are clinicians, nurses or pharmacists, other than those part of the AMS team (e.g., from the ICU, Internal Medicine and Surgery) involved in the AMS committee? | 1 | 7% | 9 | 64% | +57% |

| Do you have access to laboratory/imaging services to be able to support the diagnosis of the most common infections at your hospital? | 8 | 57% | 9 | 64% | +7% |

| Are the results available in a timely manner to be able to support diagnosis of most common infections? | 3 | 21% | 6 | 43% | +22% |

| In your hospital are there, or do you have access to healthcare professionals in infection management and stewardship willing to constitute an antimicrobial stewardship team? | 9 | 64% | 12 | 86% | +22% |

| Does your hospital offer access to educational resources to support staff training on how to optimise antimicrobial prescribing? | 2 | 14% | 6 | 43% | +29% |

| Does your hospital monitor the quantity of antimicrobials prescribed/dispensed/purchased at the unit and/or hospital wide level? | 5 | 36% | 9 | 64% | +28% |

| Does your stewardship programme monitor compliance with one or more of the specific interventions put in place by the stewardship team (e.g., indication captured in the medical record for all antimicrobial prescriptions, or antibiotic prescribed follows hospital guidelines)? | 1 | 7% | 7 | 50% | +43% |

| Has your hospital conducted a point prevalence survey (PPS) for antimicrobial use in the last year? | 1 | 7% | 11 | 79% | +72% |

| Are hospital-specific reports on the quantity of antimicrobials prescribed/dispensed/purchased shared with/fed back to prescribers? | 3 | 21% | 7 | 50% | +29% |

| Does your stewardship programme share facility-specific reports on antibiotic susceptibility rates with prescribers? | 3 | 21% | 5 | 36% | +15% |

| Are results of audits/reviews of the quality/appropriateness of antimicrobial use communicated directly with prescribers? | 1 | 7% | 7 | 50% | +43% |

| Does your hospital have available and up-to-date recommendations for infection management (diagnosis, prevention and treatment)? | 7 | 50% | 10 | 71% | +21% |

| Do you have any published AMS protocols e.g., restricted antimicrobial list, IV to oral policy (that have been ratified for use within your organisation)? | 0 | 0% | 5 | 36% | +36% |

| Do you have any published Infection Prevention and Control protocols e.g., hand hygiene, WASH (that have been ratified for use in your health institution)? | 7 | 50% | 12 | 86% | +36% |

| Are there regular infection and antimicrobial prescribing focused ward rounds in specific departments in your hospital? | 0 | 0% | 3 | 21% | +21% |

| Does the organisation have local/hospital specific antimicrobial prescribing guidelines? This may be included as part of a wider drug formulary. | 3 | 21% | 7 | 50% | +29% |

Improvements were reported across all core indicators of the AMS checklist. The largest improvements pertained to the core AMS checklist element on the multidisciplinary organisational structures responsible for AMS. Before the AMS intervention, only three healthcare sites reported having such a formal AMS structure. After the intervention, all 14 sites gave positive answers to this question, indicating a 79% increase. Other notable improvements were observed regarding the conduct of point-prevalence surveys for antimicrobial use and the availability of multidisciplinary AMS teams to support the implementation of the AMS strategy.

Smaller improvements were reported for the elements of access to laboratory or imaging services (7%) and the existence of a dedicated, sustainable, and sufficient AMS budget (14%), with the overall number of healthcare sites remaining low, even after the intervention. Lesser improvements were also observed for some items that ranked high prior to the intervention (e.g., the availability of published IPC protocols). This may be explained by a ceiling effect, whereby little further improvement could be obtained on those comparatively well-established items.

Table 2 shows a detailed breakdown of the number of members (by profession) that formed part of the multidisciplinary AMS teams pre- and post-intervention. Apart from one exception (intensive care (ITU) consultants), increases could be observed across all professional categories. The largest increase was reported in the involvement of nurses and pharmacists, with 21 new members of those professions joining the multidisciplinary AMS teams over the course of the intervention.

Table 2.

Number of members by profession of multidisciplinary AMS teams, pre- and post-AMS intervention at CwPAMS project sites.

| AMS Team Members | Pre-AMS Intervention | Post-AMS Intervention | Total Increase Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacists | 3 | 13 | 10 |

| Nurses | 3 | 14 | 11 |

| Clinicians | 3 | 11 | 8 |

| Infectious Disease doctors | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Surgeons | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Clinical microbiologists | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Laboratory microbiologists | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| ITU consultants | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data analysts | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Infection control staff | 2 | 7 | 5 |

3.2. Development and Review of Guidelines/Policies

The checklist also captured the new guideline development that resulted locally as a result of the CwPAMS intervention: Eight projects reported developing new documents (guidelines/policies/posters, etc.) focused on either AMS or antibiotic prescribing as a result of CwPAMS. Four of these projects reported developing two or more new AMS documents. Three projects reported that they had revised or updated documents (guidelines/policies/posters, etc.) focused on either AMS or antibiotic prescribing as a result of CwPAMS. Five projects reported that they had developed new documents (guidelines/policies/posters, etc.) focused on IPC as a result of CwPAMS. Three of these projects developed two or more new IPC documents. Three projects reported that they had revised or updated documents (guidelines/policies/posters, etc.) focused on IPC as a result of CwPAMS.

3.3. Raising Awareness of WHO AWaRe Categories

The AMS checklist reports indicated that 79% (11 out of 14) of the projects had increased awareness of the WHO’s AWaRE antibiotic categories among healthcare staff during the CwPAMS project. The means used to introduce the principles of WHO AWaRe included AMS train-the-trainer workshops; specific hospital meetings on the principles; AMS workshops; and Medicines and Therapeutic Committee (MTC) meetings.

3.4. Other AMS Activities

The respondents were asked to report any other actions related to AMS that were ongoing within their organisation. The following individual responses were received: Accreditation and implementation of the AMS training modules as CPD for healthcare workers; implementation of training, including those developed in the hospital and national training, drug audits and surveillance; implementation of the antibiogram; plans to engage hospital management and carry out the Global Point-Prevalence Survey (GPPS). Furthermore, also included was the formation of the Medicines Therapeutic Committee (MTC); the establishment of a community of practices; plans to resume implementation of the AMS strategy and work plan that has been on hold since the pandemic; and the development of guidelines and the publication of AMS manuscripts.

3.5. Barriers to AMS Implementation

The AMS checklist required the participants to select a maximum of six specified barriers to effective stewardship in their organisation. This also included an option for the participants to specify their own barrier if it was not listed. Table 3 shows the most important barriers selected by the participants. The same top five barriers were identified in both surveys from a list of 18 options. However, there was an increase in the proportion of respondents indicating a ‘lack of funding’ and ‘inadequate use of the microbiology laboratory’ as barriers post-intervention. In contrast, the proportion of respondents indicating ‘insufficient microbiology lab capacity’, ‘lack of motivated or engaged staff’, and ‘insufficient time for qualified personnel to perform stewardship’ as barriers decreased post-intervention. Two sites listed additional barriers that included: hierarchical barriers to pharmacists making interventions and a lack of resources.

Table 3.

Top five barriers to AMS pre- and post-AMS intervention.

| Priority | Top 5 Barriers to AMS Selected by Participants Pre- and Post-CwPAMS Intervention (Pre-AMS Intervention) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of funding |

| 2 | Insufficient microbiology lab capacity |

| 3 | Qualified personnel do not have enough time to perform stewardship |

| 4 | Inadequate use of the microbiology laboratory |

| 5 | Lack of motivated or engaged staff |

3.6. Unique Contribution of Implementing the AMS Checklist

In the post-CwPAMS checklist, 10 sites provided further information in response to the open-ended questions, which indicated that the checklist had prompted them to take additional actions that were not part of the original AMS intervention plan of the CwPAMS project. The participants were invited to report up to five additional activities that they had engaged in based on the checklist. Across all sites, 29 additional AMS activities were listed. The examples included: the development of empirical guidelines; GPPS completion; GPPS training; the establishment of a multidisciplinary AMS team; a collection of baseline data on antimicrobial use; and the conduct of an AWaRe analysis of the antibiotic prescribing patterns at their hospital. The complete list is provided in Box 1.

Box 1. Key interventions taken as a result of completing the pre-CwPAMS checklist (i.e., interventions not initially planned as part of the CwPAMS project).

Cascading training to other health care providers in the hospital.

Institution of a Hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Team.

Development of an adult empiric guideline based on common indications seen at the hospital. Annual guideline review.

Engaging with Community Durbars.

Global Point Prevalence Survey (GPPS).

Antibiotic Guidelines.

Radio Programmes November.

AMS Training Manual.

Surveillance

Auditing.

Dissemination of report.

GPPS Training

made a film focused on IPC and attendant behaviour.

Increase awareness of AMS.

Increase awareness of IPC

It enabled us to set out the goals of our partnership clearly.

To establish a multidisciplinary AMS team

To gather base line data on antimicrobial use

To conduct PPS training and studies

Conduct an AWARe analysis of antibiotic prescribing pattern at the hospital.

Conduct regular AMS training of the staff using the Scottish Triad approach

Establishing the MTC/

Plans to reconstitute alcohol hand rub.

Global Point Prevalence Study

Use of MicroGuide app to promote guidelines

Larger cohort of HPs trained.

Strengthening Hospital AMS Committee. Ensuring clarity on roles and responsibilities of AMS committee members.

Revising AMS committee membership, Developing a clear and timely action plan.

4. Discussion

Contextualised co-created AMS tools are necessary for managing the use of antimicrobials across different healthcare settings. Our work set out to develop and implement a new checklist of core AMS elements with a regional focus on Sub-Saharan Africa.

4.1. Development of the AMS Checklist

A modified Delphi process that included participants involved in partnerships of UK institutions with hospitals in Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Ghana was used to ensure that the final AMS checklist was relevant and understandable for local healthcare staff in Sub-Saharan Africa. The final tool was cognizant of the unique settings in which they operate and the differences in practice from high-income settings. Compared to the original global checklist by Pulcini et al. [11], the AMS checklist developed in this study included a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions that give room for a more comprehensive exploration of AMS activities.

The consensus process targeted the lower resource settings of LMICs in Sub-Saharan Africa by considering context-specific information and the involvement of experts from a broad range of specialities. Our work extends ongoing attempts to develop baseline assessment tools in Africa. This includes a Kenyan study in 2020, investigating the AMS policies and structures in 16 Kenyan hospitals while adapting the UK NICE AMS system to the Kenyan healthcare system [17]. Another study developed a survey questionnaire to investigate existing AMS activities for learners of the Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) [18,19].

By involving local healthcare staff in the development of our checklist, we also fostered a sense of ownership and commitment, thus serving as an example of successful co-creation. Compared to the LMIC AMS checklist contained within the WHO Practical Toolkit for healthcare facilities [12], which comprises 28 elements across six sections, our newly developed checklist contains 54 checklist items across eight main sections. While both checklists cover the more essential core elements for the National Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes, including policy, guidelines and governance, awareness, education and training, IPC and surveillance, our newly developed tool was co-created and tested in the specific healthcare setting of Sub-Saharan Africa, thus increasing its acceptability amongst hospital staff and its level of contextualisation. Acceptability and contextualisation were prioritised to ensure the continued relevance of the tool and, consequently, the sustenance of antimicrobial stewardship activities in the long run. Similar tools are available in high-income countries, including the CDC Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs developed in 2014 and updated in 2019 to reflect the new evidence from the field of antibiotic stewardship and the lessons learned from five years of experience [20]. The core elements in this checklist are similar to the developed checklist, each having sections on leadership, accountability, reporting, expertise, education, monitoring/tracking, and further actions. Additional checklist variations with adaptations to local healthcare settings could be developed following the modified Delphi consensus procedure employed in our study.

4.2. AMS Checklist Implementation

The initial results obtained from the use of our AMS checklist across 19 sites revealed large variations in the AMS’s capacities and local needs regarding support. Several healthcare sites had available expertise on infection management and stewardship, education and practical training, up-to-date recommendations for infection management, national antimicrobial prescribing guidelines, and continual monitoring and surveillance. Comparatively few sites, however, reported the presence of senior management leadership towards AMS, published AMS protocols, accountability structures, regular reporting and feedback, and routine ward rounds focused on infection and antimicrobial prescribing.

The results on the use of the checklist post-CwPAMS programme, including a range of interventions [9,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], indicate that the greatest improvements were observed in the core elements relating to senior AMS leadership, accountability, and responsibility. Smaller improvements were reported with regard to the availability of AMS expertise, education and practical training, monitoring and surveillance, and other AMS actions. The standout items included the availability of formal organisational multidisciplinary structures responsible for AMS and the conduct of point-prevalence surveys (79% and 71% improvements, respectively). At the other end of the spectrum, there were the availability of laboratory and imaging services and the presence of financial support for AMS activities, which only showed 7% and 14% improvements, respectively. The post-intervention checklist also demonstrated a better integration of pharmacists, nurses, and all clinical staff groups in AMS committees across the project sites. Local variations in improvements could be attributed to several factors, including a political and administrative will, workforce capacity and, importantly, funding.

The findings obtained through our contextualised AMS checklist mirror the published AMS reports in LMICs, which highlight the presence of national antimicrobial prescribing guidelines in the countries where the sites are located [21,31,32,33] but identify the challenges in AMR-specific education and training, diagnostic facilities, regulation of safety and efficacy of medications, and shortages of healthcare personnel and expertise [34,35,36,37]. Although these studies highlight the overall gaps in AMS implementation in LMICs, the differences observed across the regions, hospitals, and sites also demonstrate the need for case-by-case evaluations of AMS programmes for the development of appropriate and sustainable solutions. Our study suggests that the newly developed AMS checklist will enhance such evaluations across the wider region of Sub-Saharan Africa.

4.3. Barriers to and Opportunities for AMS Implementation

The initial findings from using the checklist across partnership sites reveal that the barriers that mostly existed pre-intervention were still major issues post-intervention. Some of these barriers (e.g., a lack of funding and insufficient microbiology lab capacity) could require major institutional changes to be overcome. However, other barriers (e.g., inadequate use of the microbiology laboratory and lack of motivated staff) highlight opportunities for further AMS intervention and workforce engagement.

In addition to identifying local AMS capacities and needs, our new checklist was successful in capturing the post-intervention changes in local programmes.

While some of the improvements noted above are the results of a funded AMS intervention that was part of the CwPAMS project, our end-of-project survey noted results that were not attributable to the initial CwPAMS project plans. Indeed, healthcare staff reported that the mere completion of our AMS checklist prompted them to engage in a revision of their AMS activities and led to important changes in their daily practice. Twenty-nine additional AMS activities were listed by the participating healthcare sites as having resulted from completing the checklist. While some of these activities (notably improved recommendations around infection control) may be explained by the global pressures of healthcare-associated infections and, latterly, the COVID-19 pandemic, other activities (e.g., the development of empirical guidelines around antibiotic prescribing) were directly related to AMS. Our results thus suggest that the newly developed contextualised AMS checklist has the potential to make a positive impact on the effectiveness of AMS interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this work was that the study employed a modified Delphi consensus process, which is a standard method of developing checklists or similar tools and has been widely used for designing AMS programmes in hospitals. We engaged local stakeholders, including senior management, frontline healthcare professionals, and public health specialists, in the consensus process, thus increasing elements of co-creation and a subsequent sense of ownership for the materials. This also meant that the checklist modifications were context-specific and relevant to health institutions. The representatives were recruited based on their level of expertise, level of interest, heterogeneity, accessibility, and the intended size of the panel, as recommended by the existing literature [38,39]. Furthermore, our selection strongly considered representativeness as it engaged stakeholders across all partnership sites in all countries.

This study, which commenced prior to the publication of the WHO AMS toolkit for LMICs, provides an additional step toward increasing the suitability and acceptance of standardised AMS tools in LMIC settings in several different ways:

-

(1)

Our narrow focus on Sub-Saharan Africa (specifically Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Ghana) allows for further local adaptation of the materials.

-

(2)

Our unique methodological approach uses elements of co-creation through the strong involvement of local hospital representatives during a Delphi consensus procedure.

-

(3)

We extended the number of checklist items to capture the more nuanced differences in the AMS elements. Additionally, we incorporate open-ended questions within the AMS checklist to allow for more reporting flexibility.

-

(4)

We provide an initial evaluation of the checklist’s effectiveness by using it to measure the outcomes of an AMS intervention programme.

The Delphi process was limited by not having an opportunity for face-to-face discussions about specific items. The small number of study sites could be considered a limitation; however, the similarity of the results across multiple countries suggests the results are transferable and that the approach can be implemented within other countries.

5. Conclusions

Our study has tested a successful methodology for making regional adaptations to global AMS tools and demonstrated the effectiveness of a contextualised AMS checklist in the challenging healthcare setting of Sub-Saharan Africa. This effectiveness was shown to go beyond the mere capture of the AMS changes following an intervention. Indeed, our results suggested that completing the checklist prompted local healthcare providers to review their initiatives and increase their AMS efforts. Our AMS checklist is widely available for use in health partnerships and institutions and extends the existing tools, such as Pulcini et al.’s [11] global AMS checklist and the WHO LMIC toolkit [24].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following lead persons who completed the checklist from the UK partnership team: Louise Ackers, Sam Ghebrehewet, Gillian Taylor, Esther Johnston, Mariyam Mirfenderesky, Yogini Jani, Corina Weir, Niall Anderson, Scott Barrett, James Whitehorn, Jacqueline Sneddon, Fran Garraghan, Anja St. Claire-Jones, Evelyn Brealey, Joseph Brayson, Preet Panesar, Jenny Westad, Clare Chandler, Claire Brandish, Bee Yean Ng, Jasmin Islam. We would also like to thank the lead persons who completed the checklist from the partnership teams at the hospitals in Africa: Dorothy Gashuga, Juliana Ameh, Samuel Odonkor, Jean Young, Daniel Ankrah, Isaac Folitse, Cornelius Dodoo, Freddy Kitutu, Ismail Kizito Musoke, Amos Mutebi, Peter Benedict, Musa Sekikubo, Israel Sefah, Daniel Kwame Afriyie, Sr Josephine Mary Oyella, Zainab Akello, Fred Kitutu, Aubrey Kalungia, Joe Odur, George Amofah, Jean Anne Young, Israel Sefah, Jonathan Jato, William Olu, and Enock Chikatula. We would also like to acknowledge the following people who completed the checklist from the five regional referral hospitals in Uganda: Manzi, Rodney, Tabaruka Tibaruha, Patrick Opio, Amandu Christopher, and Sande Alex. Finally, we acknowledge Nduta Kamere’s administrative support during the manuscript’s submission and revision.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare10091706/s1. Supplementary Material S1: Consensus procedure; Supplementary Material S2: Differences in the AMS Checklist compared to the checklist by Pulcini et al.; Supplementary Material S3: Hospital sites where the research was conducted; Supplementary Material S4: Baseline AMS checklist data from non-CwPAMS sites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.-O.; Methodology, D.A.-O., A.M. (Ayodeji Matuluko), W.N., P.A.B., C.T., E.C. (Esmita Charani), M.L. and A.M. (Augustine Malinga); Data curation and Investigation, D.A.-O., A.M. (Ayodeji Matuluko), W.N., P.A.B., C.T., G.A., D.A., S.B., K.P.B., K.O.B., E.C. (Enock Chikatula), S.G., J.I., Y.H.J., E.J., M.M. and J.S.; Formal analysis, D.A.-O., F.G., O.O., E.M.K. and A.M. (Ayodeji Matuluko); Writing—original draft, D.A.-O., O.O., E.M.K. and A.M. (Ayodeji Matuluko); Writing—review and editing, D.A.-O., F.G., O.O., E.M.K., A.M. (Ayodeji Matuluko), W.N., P.A.B., C.T., G.A., D.A., S.B., P.B., K.P.B., K.O.B., S.C., E.C. (Esmita Charani), E.C. (Enock Chikatula), S.G., Y.H.J., E.J., M.L., A.M. (Augustine Malinga), M.M., V.R., J.S. and R.S.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Formal ethics approval was not required as the project was part of a wider service development project that the CPA was leading for the CwPAMS programme. In addition, there was no direct patient contact, and all data were anonymized. The hospital administration/management board and senior leadership granted the approval for the partnership, memorandum of understanding, and CwPAMS project proposal before the commencement of the projects.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. The participants in the focus group discussions came from diverse backgrounds, and recommendations were created by consensus. They, therefore, may not represent the individual views of all those who participated.

Funding Statement

This project and partnership were part of the Commonwealth Partnerships for Antimicrobial Stewardship (CwPAMS), managed by the Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET) and Commonwealth Pharmacists Association (CPA). CwPAMS is a global health partnership programme funded by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) using UK aid funding, managed by the Fleming Fund. The Fleming Fund is a £265 million UK aid investment to tackle AMR by supporting low- and middle-income countries to generate, use and share data on AMR and is managed by the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Health and Social Care, the UK National Health Service, the Tropical Health and Education Trust, or the Commonwealth Pharmacists Association.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. Available online: http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davey P., A Marwick C., Scott C.L., Charani E., McNeil K., Brown E., Gould I.M., Ramsay C.R., Michie S. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;2017:CD003543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd003543.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charani E., Holmes A.H. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes: The need for wider engagement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013;22:885–887. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charani E., Holmes A. Antibiotic Stewardship—Twenty Years in the Making. Antibiotics. 2019;8:7. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs|Get Smart for Healthcare|CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)];2016 :1–25. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html.

- 6.GOV.UK Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance 2019–2024: The UK’s Five-Year National Action Plan. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)];2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.02.019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-5-year-action-plan-for-antimicrobial-resistance-2019-to-2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goff D.A., Ashiru-Oredope D., Cairns K.A., Eljaaly K., Gauthier T.P., Langford B.J., Mahmoud S.F., Messina A.P., Michael U.C., Saad T., et al. Global contributions of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020;3:1480–1492. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr F., Sefah I., Essah D., Cockburn A., Afriyie D., Mahungu J., Mirfenderesky M., Ankrah D., Aggor A., Barrett S., et al. Practical Pharmacist-Led Interventions to Improve Antimicrobial Stewardship in Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Pharmacy. 2021;9:124. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9030124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandish C., Garraghan F., Ng B., Russell-Hobbs K., Olaoye O., Ashiru-Oredope D. Assessing the Impact of a Global Health Fellowship on Pharmacists’ Leadership Skills and Consideration of Benefits to the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. Healthcare. 2021;9:890. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9070890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kpokiri E.E., Ladva M., Dodoo C.C., Orman E., Aku T.A., Mensah A., Jato J., Mfoafo K.A., Folitse I., Hutton-Nyameaye A., et al. Knowledge awareness and practice with antimicrobial stewardship programmes among healthcare providers in a Ghanaian Tertiary Hospital. Antibiotics. 2021;11:6. doi: 10.1101/2021.11.14.21266285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulcini C., Binda F., Lamkang A.S., Trett A., Charani E., Goff D.A., Harbarth S., Hinrichsen S.L., Levy-Hara G., Mendelson M., et al. Developing core elements and checklist items for global hospital antimicrobial stewardship programmes: A consensus approach. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Health-Care Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A WHO Practical Toolkit. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329404. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Fleming Fund Commonwealth Health Partnerships to Improve Antimicrobial Stewardship Announced! 2019. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. Available online: https://www.flemingfund.org/publications/commonwealth-health-partnerships-to-improve-antimicrobial-stewardship-announced/

- 14.THET Partnerships for Global Health Commonwealth Partnerships for Antimicrobial Stewardship Scheme. 2019. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. Available online: https://www.thet.org/our-work/grants/cwpams/

- 15.Commonwealth Pharmacists Association Commonwealth Partnerships for Antimicrobial Stewardship. 2019. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. Available online: https://commonwealthpharmacy.org/commonwealth-partnerships-for-antimicrobial-stewardship/

- 16.GOV.UK Funding for Commonwealth Partnerships to Improve Antimicrobial Stewardship. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)];2019 Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/funding-for-commonwealth-partnerships-to-improve-antimicrobial-stewardship.

- 17.McKnight J., Maina M., Zosi M., Kimemia G., Onyango T., Schultsz C., English M., Tosas-Auguet O. Evaluating hospital performance in antibiotic stewardship to guide action at national and local levels in a lower-middle income setting. Glob. Health Action. 2019;12:1761657. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1761657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charani E., Castro-Sanchéz E., Bradley S., Nathwani D., Holmes A.H., Davey P. Implementation of antibiotic stewardship in different settings–results of an international survey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019;8:34. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0493-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charani E., Castro-Sánchez E., Sevdalis N., Kyratsis Y., Drumright L., Shah N., Holmes A. Understanding the determinants of antimicrobial prescribing within hospitals: The role of “Prescribing etiquete”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57:188–196. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC . Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA: 2019. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)]. US Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/core-elements/hospital.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olaoye O., Tuck C., Khor W.P., McMenamin R., Hudson L., Northall M., Panford-Quainoo E., Asima D.M., Ashiru-Oredope D. Improving Access to Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines in 4 African Countries: Development and Pilot Implementation of an App and Cross-Sectional Assessment of Attitudes and Behaviour Survey of Healthcare Workers and Patients. Antibiotics. 2020;9:555. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9090555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musoke D., Kitutu F., Mugisha L., Amir S., Brandish C., Ikhile D., Kajumbula H., Kizito I., Lubega G., Niyongabo F., et al. A One Health Approach to Strengthening Antimicrobial Stewardship in Wakiso District, Uganda. Antibiotics. 2020;9:764. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9110764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afriyie D.K., Sefah I.A., Sneddon J., Malcolm W., McKinney R., Cooper L., Kurdi A., Godman B., Seaton R.A. Antimicrobial point prevalence surveys in two Ghanaian hospitals: Opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2020;2:dlaa001. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlaa001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ankrah D., Owusu H., Aggor A., Osei A., Ampomah A., Harrison M., Nelson F., Aboagye G.O., Ekpale P., Laryea J., et al. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Utilization in Ghana’s Premier Hospital: Implications for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1528. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10121528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Arcy N., Ashiru-Oredope D., Olaoye O., Afriyie D., Akello Z., Ankrah D., Asima D.M., Banda D.C., Barrett S., Brandish C., et al. Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania Hospitals: Results from the Global Point Prevalence Survey (G-PPS) on Antimicrobial Use and Stewardship Interventions Implemented. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1122. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10091122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghebrehewet S., Shepherd W., Panford-Quainoo E., Shantikumar S., Decraene V., Rajendran R., Kaushal M., Akuffo A., Ayerh D., Amofah G. Implementation of a Delayed Prescribing Model to Reduce Antibiotic Prescribing for Suspected Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in a Hospital Outpatient Department, Ghana. Antibiotics. 2020;9:773. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9110773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalungia A., Jones A.S.C., Lippett S., May C. UK and Zambian Pharmacists Working Together: Improving Antimicrobial Stewardship and Pharmaceutical Education. International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Congress; Abu Dhabi, UAE: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashiru-Oredope D., Chan A.H.Y., Olaoye O., Rutter V., Babar Z.-U., Anderson C., Anderson R., Halai M., Matuluko A., Nambatya W., et al. Needs assessment and impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy professionals in 31 commonwealth countries. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020;13:72. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubai K.D. Ph.D. Thesis. Makerere University; Kampala, Uganda: 2021. Implementation and Barriers to Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities in Private Hospitals in Kampala, Uganda; A Case of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ackers L., Ackers-Johnson G., Seekles M., Odur J., Opio S. Opportunities and challenges for improving anti-microbial stewardship in low-and middle-income countries; lessons learnt from the maternal sepsis intervention in Western Uganda. Antibiotics. 2020;9:315. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yevutsey S.K., Buabeng K.O., Aikins M., Anto B.P., Biritwum R.B., Frimodt-Møller N., Gyansa-Lutterodt M. Situational analysis of antibiotic use and resistance in Ghana: Policy and regulation. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:896. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haldeman M.S., Kishimbo P., Seddon M., Sangare A., Mwasomola D., Hall J., Shaffer M., Leclair R., Caulder C., Bookstaver P.B., et al. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Utilization and Concordance with National Guidelines at a Tertiary Hospital in the Southern Highlands Zone of Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;102:370–376. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nambasa V., Ndagije H., Serwanga A., Manirakiza L., Atuhaire J., Nakitto D., Kiguba R., Figueras A. Prescription of Levofloxacin and Moxifloxacin in Select Hospitals in Uganda: A Pilot Study to Assess Guideline Concordance. Antibiotics. 2020;9:439. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9080439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thriemer K., Katuala Y., Batoko B., Alworonga J.-P., Devlieger H., Van Geet C., Ngbonda D., Jacobs J. Antibiotic prescribing in DR Congo: A knowledge, attitude and practice survey among medical doctors and students. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quet F., Vlieghe E., Leyer C., Buisson Y., Newton P., Naphayvong P., Keoluangkhot V., Chomarat M., Longuet C., Steenkeste N., et al. Antibiotic prescription behaviours in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: A knowledge, attitude and practice survey. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015;93:219–227. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.142844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tadeg H., Berhane Y. Substandard and counterfeit antimicrobials: Recent trends and implications to key public health interventions in developing countries. East Afr. J. Public Health. 2012;9:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinfu Y., Dal Poz M.R., Mercer H., Evans D.B. The health worker shortage in Africa: Are enough physicians and nurses being trained? Bull. World Health Organ. 2009;87:225–230. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beiderbeck D., Frevel N., von der Gracht H.A., Schmidt S.L., Schweitzer V.M. Preparing, conducting, and analyzing Delphi surveys: Cross-disciplinary practices, new directions, and advancements. MethodsX. 2021;8:101401. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2021.101401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Förster B., von der Gracht H. Assessing Delphi panel composition for strategic foresight—A comparison of panels based on company-internal and external participants. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2013;84:215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2013.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.