Abstract

Introduction:

Patients affected by spina bifida (SB) can present varying degrees of paralysis, limited mobility, impaired sensation, orthopedic problems and bowel, bladder, and renal impairments. Skin wounds are reported as one of the primary diagnosis associated with hospitalizations in SB affected patients. In young patients, pressure injuries can occur more frequently at the lower limb. A multidisciplinary approach and a proper surgical technique are mandatory to obtain favorable long-term outcomes, in terms of adequate coverage and risk of recurrence.

Case Presentation:

A Caucasian male 21-year-old wheelchair-bound patient with history of SB was admitted to our department with stage four pressure injury on the medial aspect of knee joint and osteomyelitis. After antibiotic therapy wound preparation and debridement, we covered the pressure sore with a pedicled fasciocutaneous flap harvested from the medial compartment of the thigh. In the distal part, we splitted the fascia from the flap and used it to reconstruct the exposed knee joint. We did not report any complications and no recurrence was observed at 1-year follow-up examination.

Conclusion:

In this reported case, the multidisciplinary approach and the surgical technique allowed us to cover the soft-tissue defect around knee joint, reducing morbidity, surgical time, and cost with good long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Spina bifida, pressure injuries, fasciocutaneous flap

Learning Point of the Article:

Surgical treatment of pressure ulcers in spina bifida.

Introduction

The term spina bifida (SB) is generally used to describe dysraphic lesions which are determined by the embryological failure of fusion of one or more vertebral arches [1]. In Italy, the National Registry reports an overall rate of 4–6 cases per 10,000 newborns. One thousand five hundred infants with SB are recorded yearly in the United States [2]. with a reported overall rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000: 4.7 cases in children from Hispanic mothers, 3.2 from non-Hispanic white mothers, and 2.6 from non-Hispanic black mothers [3].

SB is a common disability in children and adolescents and it’s characterized by different clinical pictures depending on the associated neuroectoderm involvement defects.

Patients affected by SB can have different degrees of limitations due to motor impairments and sensory disorders: they can present musculoskeletal disorders (scoliosis, congenital hip dysplasia, and clubfeet), gastrointestinal, urological, and nephrological diseases [4, 5].

In this article, we present a case of stage four left knee pressure injury in a 21-year-old male patient affected by SB. Many reconstructive techniques to repair soft-tissue defects of the knee joint are described on the basis of the size, location, and depth. . In this case, we used a random pedicled fascio-cutaneous flap after debridement and negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT).

Case Report

A Caucasian 21-year-old male wheelchair-bound patient with history of SB was admitted to our department for a stage four pressure injury (four 4 cm diameter), on the medial aspect of his left knee. The patient referred evening fever during the previous week. Microbiological samples and skin biopsies of the wound bed were collected. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa was present in all the microbiological cultures.

Laboratory findings at the admission revealed high level C-reactive protein (8,.38 mg/dL).

Our first treatment was debridement and dressing every 2 days. Regarding the dressing, we prescribed an activated charcoal dressing with silver (ACTISORB™ SILVER 220) for two 2 weeks (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Wound after 2 weeks of hospitalization

Piperacillin-Tazobactam (TAZOCIN®) 4 g/0,.5 g three 3 times/daily was administered on the basis of antibiogram tests, monitoring weekly renal and hepatic functions.

Knee osteomyelitis was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

NPWT was applied for 15 days (ActiV.A.C®. Therapy Unit-K.C.I.Medical s.r.l.) using Polyhexamethylene polyhexamethylene Biguanide biguanide foam at –80 mmHg intermittent flow (three changes per week).

Improvement of clinical signs of inflammation (Fig. 2) and significant decrease of C-reactive protein (2,.63 mg/dL) was observed after 2 weeks of treatment.

Figure 2.

Wound after 15 days of NPWT.

Afterwards, we used a random pedicled fascio-cutaneous flap to cover the wound defect (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Pre-operative planning.

Under general anesthesia, the patient in lateral decubitus positioned, we debrided the ulcer by using methylene blue with the aim to remove all the potentially contaminated tissue (Fig. 4), obtaining a healthy vascularized tissue. The knee joint capsule was interrupted with a partial exposition of the joint (Fig. 5). A pedicled fascio-cutaneous flap (size: 24 cm ×X 9 cm) harvested from the medial aspect of the omolateral thigh (Fig. 6) was advanced to cover the ulcer. The distal part of the fascia was detached from the flap and sutured to the capsule to cover the knee joint (Fig. 7). The flap was sutured in a layered fashion, without tension, using absorbable stitches and surgical skin staples (Fig. 8). A closed suction drain was placed.

Figure 4.

Radical debridement of the ulcer was performed using methylene blue staining.

Figure 5.

Wound bed after debridement.

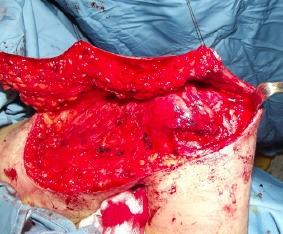

Figure 6.

Flap elevation

Figure 7.

Coverage of the knee joint with a fascial flap.

Figure 8.

Flap at the end of the surgical procedure

Despite the big amount of serous fluid collected in the drain in the first 10 days after surgery, we did n’t not report seromas or other complications.

The patient was discharged 2 weeks after the operation (Fig. 9). No recurrence was observed after 1 year (Fig. 10).

Figure 9.

The patient 1 month after surgery.

Figure 10.

One year follow-up.

Surgical time was 60 minutes. Length of hospitalization was 45 days.

Discussion

It’s not surprising that patient’s clinical condition and the reduced mobility may predispose to pressure injuries. In patients affected by SB, skin lesions are the most frequent reasons for hospital admission [6]. Under 10-year-old children often present pressure ulcers of the lower limb; posterior pelvis is the area most commonly involved in older patients [5]. Pressure injuries occur in the case of prolonged pressure over soft tissue and the damage can be the trigger of infections and sepsis.

Surgical care of patients with pressure sores are is of paramount importance and must start before entering the operating room. Successful pressure injury coverage is multifactorial and a multidisciplinary approach may significantly improve healing and shorten the length of hospitalization [7]. Before surgery infection, investigation and control is are mandatory [8, 9]. In our hospital, we manage complex infected wounds with the collaboration of our colleagues of the department of infectious and tropical diseases.

In pressure sores, topical treatment may require advanced wound dressing. Patients with Stages 3 and 4 pressure ulcers often require negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) surgical debridement, skin-grafting, and/or flap reconstruction. In this clinical case, we firstly removed the necrotic tissues and used an advanced dressing (ACTISORB™ SILVER 220) that consists of activated carbon impregnated with metallic silver every two 2 days. Afterward, we applied NPWT with PHMB-gauze (ActiV.A.C®. Therapy Unit-K.C.I.Medical s.r.l.) with the aim to reduce exudates and bacteria load [10]. Moreover on the basis of our clinical experience, the gauze allows to fill all the undermined areas of the wounds and seems to produce a more pliable scar tissue [11, 12].

In the literature, many surgical strategies have been described for pressure ulcer coverage: Primary closure [8], skin grafts [8], tissue expansion [13], pedicled [8], free flap [14], and more recently perforator based flap [15, 16]. Considering the high risk of recurrence, a proper technique selection is mandatory.

Pedicled myocutaneous flap have has been considered one of the best surgical choices since their historical description for reconstruction of deep pressure ulcers [17]. It would have been a good choice in this case, but we preferred to preserve the muscular function to avoid reducing patient’s mobility even further. Moreover, in the reconstructive ladder, we consider safer to have a second surgical strategy in case of sore recurrence. In selected patients, free tissue transfer can be considered a valid surgical approach and since the 1970s up to now, some authors have reported successful outcomes by using innervated microsurgical flaps [8, 14]. However, it is a difficult and less frequently used reconstructive strategy. In recent years, some surgeons have described the use of propeller flaps [15] accordingly to the need for adequate bulk, vascularization, and sensory recovery with as less morbidity as possible. On the basis of literature data, no significant differences have been noticed comparing the above mentioned techniques in the treatment of pressure ulcers in terms of outcomes [16, 18].

Keeping in mind all these considerations, we opted for a random pedicled fasciocutaneous flap, harvested from the medial side of the left thigh. The big size of the flap allowed us to cover the ulcer with minimal tension. The fascia, splitted from the flap, allowed us to cover the knee-joint and recreate anatomical layers.

Regarding surgical time, we can assume that more complex and long-lasting procedures could be performed only in selected patients and in case of recurrences.

Conclusion

In this reported case, a multidisciplinary approach and the chosen surgical technique allowed us to cover soft-tissues defect around the knee joint, reducing morbidity, surgical time, and cost with good long-term outcome.

Clinical Message.

Skin wounds are one of the main reasons of hospitalization in patients with history of SBSpina Bifida. The more frequently involved areas of pressure sores in patients affected by SBSpina Bifida are the foot, the lower limb, and posterior pelvis. Choose the best surgical option that guarantees a good ulcer coverage with as less morbidity as possible. During decision making, keep in mind surgical times, costs, and risk of recurrence.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Mccomb JG. A practical clinical classification of spinal neural tube defects. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015;31:1641–57. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin M, Besser LM, Siffel C, Kucik JE, Shaw GM, Lu C, et al. Prevalence of Spina Bifida among children and adolescents in 10 regions in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:274–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulet SL, Yang Q, Mai C, Kirby RS, Collins JS, Robbins JM, et al. Trends in the postfortification prevalence of spina bifida and anencephaly in the United States. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:527–32. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawin KJ, Liu T, Ward E, Thibadeau J, Schechter MS, Soe MM, et al. The national spina bifida patient registry:Profile of a large cohort of participants from the first 10 clinics. J Pediatr. 2015;166:444–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim S, Ward E, Dicianno BE, Clayton GH, Sawin KJ, Beierwaltes P, et al. Factors associated with pressure ulcers in individuals with spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dicianno BE, Wilson R. Hospitalizations of adults with spina bifida and congenital spinal cord anomalies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:529–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson C, Choudry M, White C, Mecci M, Siddiqui H. Multi-disciplinary management of complex pressure sore reconstruction:5-year review of experience in a spinal injuries centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:169–74. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer J, Phillips LG. MOC-PSSM CME article:Pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000294671.05159.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medical Advisory Secretariat. Management of chronic pressure ulcers:An evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2009;9:1–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraccalvieri M, Pristerà G, Zingarelli E, Ruka E, Bruschi S. Treatment of chronic heel osteomyelitis in vasculopathic patients. Can the combined use of Integra ®, skin graft and negative pressure wound therapy be considered a valid therapeutic approach after partial tangential calcanectomy? Int Wound J. 2012;9:214–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraccalvieri M, Scalise A, Ruka E, Zingarelli EM, Renato C, Antonino S, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy using gauze and foam:Histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrasonography morphological analysis of granulation and scar tissues second phase of a clinical study. Eur J Plast Surg. 2014;37:411–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraccalvieri M, Zingarelli E, Ruka E, Antoniotti U, Coda R, Sarno A, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy using gauze and foam:Histological, immunohistochemical and ultrasonography morphological analysis of the granulation tissue and scar tissue. Preliminary report of a clinical study. Int Wound J. 2011;8:355–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neves RI, Kahler SH, Banducci DR, Manders EK. Tissue expansion of sensate skin for pressure sores. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29:433–7. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel RK, Terzis JK, Cunningham DM. Sensory skin flaps for coverage of pressure sores in paraplegic patients. A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:317–28. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santanelli Di Pompeo F, Longo B, Pagnoni M, Laporta R. Sensate anterolateral thigh perforator flap for ischiatic sores reconstruction in meningomyelocele patients. Microsurgery. 2015;35:279–83. doi: 10.1002/micr.22330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sameem M, Au M, Wood T, Farrokhyar F, Mahoney J. A systematic review of complication and recurrence rates of musculocutaneous, fasciocutaneous, and perforator-based flaps for treatment of pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:67–77. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b19f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ger R, Levine SA. The management of decubitus ulcers by muscle transposition. An 8-year review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:419–28. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo PJ, Chew KY, Kuo YR, Lin PY. Comparison of outcomes of pressure sore reconstructions among perforator flaps, perforator-based rotation fasciocutaneous flaps, and musculocutaneous flaps. Microsurgery. 2014;34:547–53. doi: 10.1002/micr.22257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]