Abstract

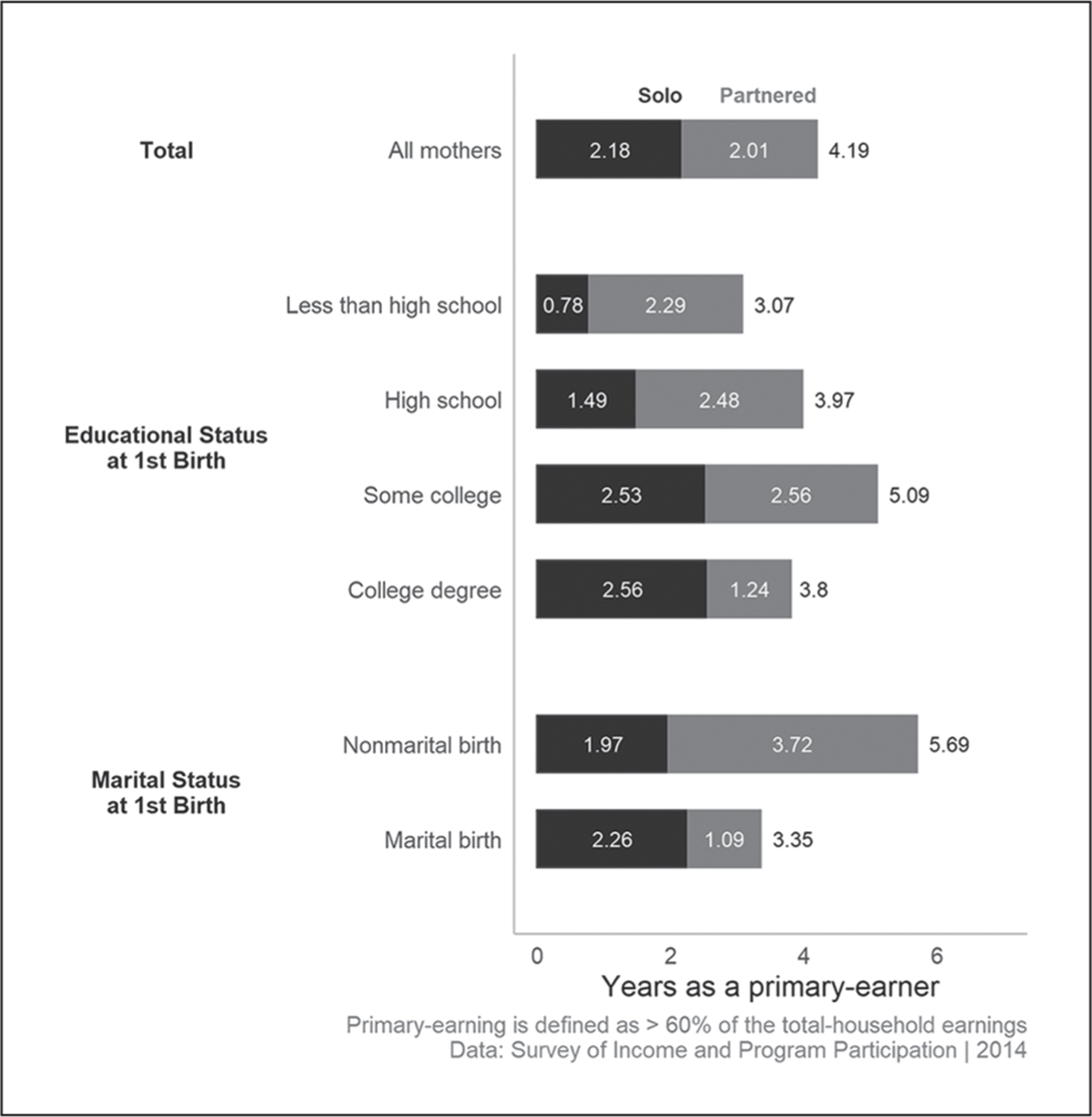

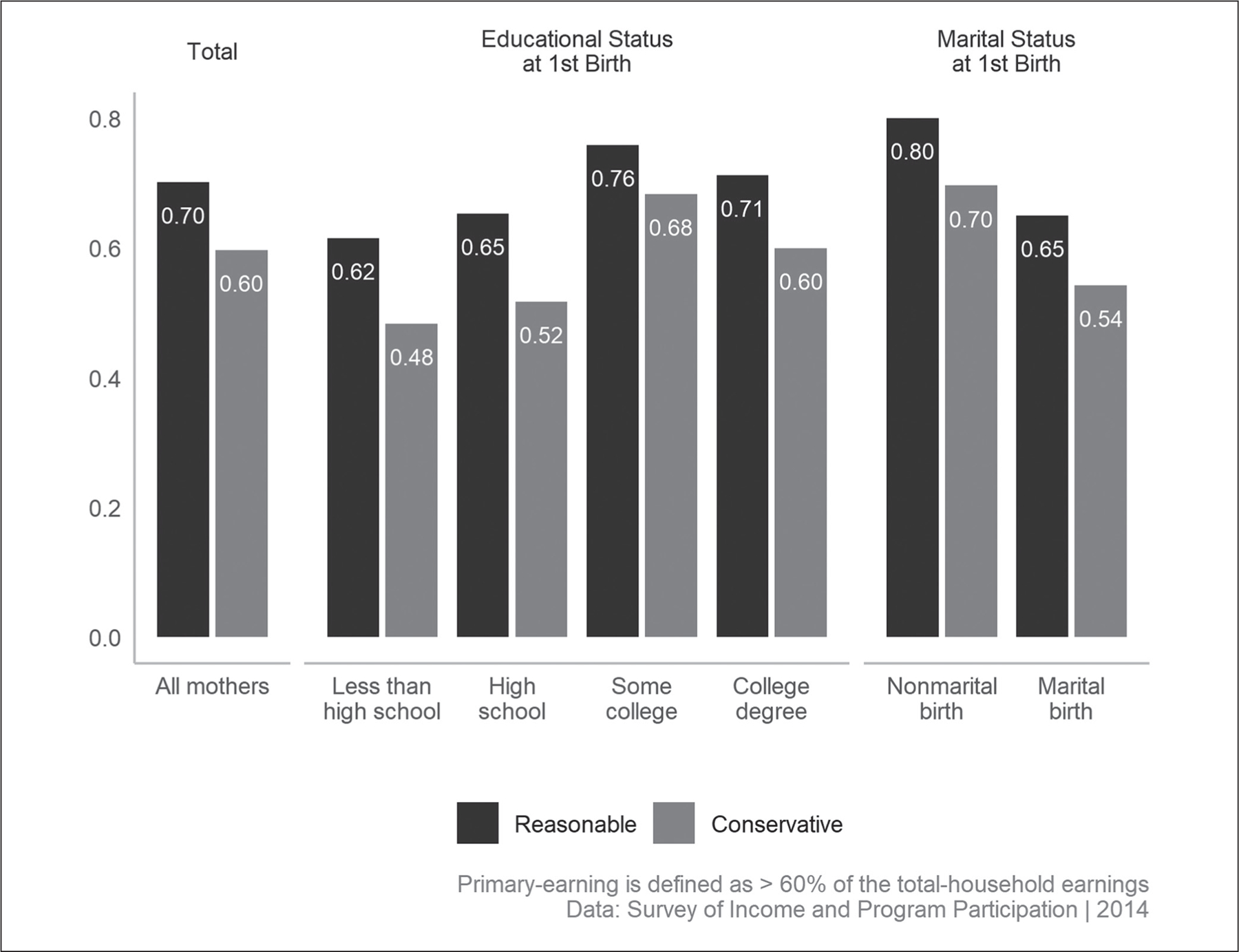

Over 40 percent of American children rely primarily on their mothers’ earnings for financial support in cross-sectional surveys. Yet these data understate mothers’ role as their family’s primary earner. Using longitudinal Survey of Income and Program Participation panels beginning in 2014, we create multistate life table estimates of mothers’ duration as primary earner as well as single-decrement life table estimates of their chance of ever being the primary earner over the first 18 years of motherhood. Using a threshold of 60 percent of household earnings to determine primary earning status, mothers average 4.19 years as their families’ primary earner in the 18 years following first birth. Mothers with some college but no degree spent the most years as primary earners, about 5.09 years on average, as did mothers with nonmarital first births, about 5.69 years. Around 70 percent of American mothers can reasonably expect to be their household’s primary earner at some point during their first 18 years of motherhood.

Keywords: employed mothers, breadwinning, earnings, welfare reform

Mothers’ earnings have been supplementing fathers’ stagnating wages since the 1970s; now, in a substantial number of families, mothers are the primary earners in households with minor children. U.S. Census figures reveal that more than 40 percent of American children are solely or primarily supported by their mothers’ earnings in any given year (Wang, Parker, and Taylor 2013; Women’s Bureau 2016). Around 25 percent of these children live with a single mother, whereas the remaining 15 percent reside in a two-parent household in which their mother earns the majority of the household income. Moreover, growth in mothers’ financial provision since early 2000s has been concentrated among partnered, not single, mothers. Only 15 percent of primary-earning women in 2000 were married, jumping to 38 percent by 2017.1 Although still relatively unusual, the proportion of married mothers who outearned their husbands increased from 4 percent in 1960 to 15 percent by 2011 (Wang et al. 2013). This increase in dependency on mothers’ earnings has occurred in every demographic group, including highly educated married couples, though the probability of mothers being the primary earner in the family diminishes with increases in household income quintile (Glynn 2016).

These figures, however high they may appear in absolute terms, understate mothers’ lifetime experience of being the primary economic support for their children, representing at best a static cross-section of mothers’ and children’s situation in any one year. Observed over time, the cumulative number of years mothers primarily rely on their own earnings to support their children provides a more holistic picture of the degree to which children truly depend on their mothers’ earnings. Point-in-time estimates fail to adequately capture mothers who experience long spells in which their families depend on their earnings. Data from the late 1990s showed that when wives’ earnings surpassed their husbands, the arrangement persisted over the three-year study period in 60 percent of couples and was transitory for the remaining 40 percent (Winkler, McBride, and Andrews 2005). Given the growth in the proportion and change in composition of children who reside with primary-earning mothers (more partnered but fewer married mothers), the average duration of reliance on mothers’ earnings may have lengthened since then. We use recent data to determine the average number of years that American mothers spend as primary earners for their families irrespective of marital status, combining spells as a partnered and single parent among those who change their status over time.

Mothers’ lifetime chance of ever being a primary earner is also assuredly higher than the currently available cross-sectional estimates. Rising economic precarity among wage-earning male partners means a sizable number of families are likely to rely on mothers’ earnings at some time, even if they do not consistently rely on her earnings after the first child is born. Disruptions to family life stemming from the retreat of fathers who reliably pay for their children mean an increasing number of mothers find themselves providing for their children on their own at some point in time. Although cross-sectional analyses provide important insight into the prevalence of mothers who are primary earners at a particular moment, determining the proportion of mothers who ever experience primary earning may better reflect how common the role of financial provider has become in mothers’ lives.

Some conditions pull mothers into primary-earning status, such as high earning potential, while other situations push mothers into primary earning, such as relationship dissolution and partner difficulties in maintaining employment (which often co-occur). The less desirable pushes into financial provision tend to be concentrated among mothers with less education usually partnered to fathers with less education (Gonalons-Pons and Schwartz 2017). The social consequences of mothers’ position as the primary earner for their children are highly intertwined with their ability to take on those economic responsibilities—for those with high earning potential, reliance on mothers’ earnings may not disadvantage children. But those mothers with lower levels of human capital pushed into primary earning may find it especially challenging to support their children in the types of jobs available to them, resulting in their children’s cumulative disadvantage. We document differences in mothers’ duration of primary earning and propensity to become primary earners by their educational attainment. We isolate differences by mothers’ educational attainment to directly assess the risk that mothers with low levels of occupational preparation will nevertheless need to support their children financially. This allows us to assess whether the mothers most likely to be primary earners are also those most likely to be able to financially provide for their children if called upon to do so.

Lack of awareness of children’s dependence on mothers’ financial contributions may lead families to underestimate the financial strain they may face if mothers curtail their labor force participation to accommodate childbearing and child care. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, early reports show devastating job losses and voluntary departures from the labor force among women with minor children (Catalyst 2020; Collins et al. 2020; Thomas et al. 2020). Numerous writers have worried that the economic shutdown and closure of child care and schools will have a lasting impact on mothers’ labor force participation and earnings (Dickson 2020; Grose 2020; Risman 2020). If more families rely on mothers’ earnings than cross-sectional estimates suggest, these predictions may be understating the eventual losses for children and families more broadly.

In this paper, we provide a more complete picture of the magnitude of mothers’ financial responsibility for their children. Using the 2014–17 panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), we calculate estimates of the average duration American mothers spend as primary earner following the birth of their first child using multistate life tables, subdivided into durations as a single parent and partnered parent, respectively. We also calculate mothers’ cumulative probability of ever holding primary-earner status for at least one full year from the time their first child is born until the child is 18 years old using single-decrement life tables. We supplement this with separate estimates of the cumulative probability of ever holding primary-earner status for those with marital versus nonmarital first births, recognizing that nonmarital first births have a higher likelihood of resulting in single motherhood and children’s financial dependency on their mother’s earnings.

Our analyses estimate the distribution of mothers’ primary-earning responsibilities in total and across levels of mothers’ educational attainment, to provide insight into the question of whether primary earning is most common among mothers with higher levels of human capital. The next section of the paper provides a brief synopsis of the mechanisms that have led to growth in the proportion of primary-earning mothers. We then discuss the empirical challenges in estimating primary earner status and present our findings.

Background

Mechanisms of Change

In both public policy and personal decision-making, the hiring and pay penalties experienced by mothers (Budig and England 2001; Correll, Benard, and Paik 2007) are viewed as a less urgent problem because most mothers and their children receive their primary financial support from fathers and/or government. Yet, to a large extent, this is no longer true. Evidence suggests that fathers, employers, and government are all retreating from paying the escalating fiscal costs of raising children to productive adulthood.

Fathers are less reliable financial providers for two interrelated reasons: family disruption and rising economic precarity among young men. The growth of nonmarital childbearing and short-term cohabitation have made fathers’ household absence a normative experience for many American children (Livingston 2018). Men are far less likely to spend a significant proportion of their adult life living with dependent children now than in the past (Eggebeen 2002; King 1999).

But the problem extends beyond fathers to their employers. Even when fathers do reside with their children, many are subject to low wages, uncertain hours, and job insecurity, especially those without advanced education and training (Kalleberg 2018). The post–World War II compact between labor and management that produced a “family wage” for adult married men has eroded, as global economic competition increased (Lin and Neely 2020). Just-in-time scheduling practices made finding and keeping full-time hours more of a challenge than in the past, while mergers and acquisitions resulted in less job security even for those in white-collar occupations (Kalleberg 2018; Lambert, Henly, and Kim 2019). These circumstances create unexpected shorter-term instances in which families are reliant on mothers’ earnings (Winkler et al. 2005).

Finally, government policy has clearly intervened on the side of mothers’ financial responsibility for children, by incentivizing paid work for low-income mothers through the earned-income tax credit and the gutting of cash benefits to poor single mothers. The Personal Responsibility and Welfare Reform Act of 1996 signaled an ideological shift in policy away from the idea that a mother’s right to government support comes from her work caring for her children to the idea that a mother’s right to support comes from her efforts to support her children financially through employment. As a result, many more mothers of young children are employed, and cash payments to mothers (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) have fallen to their lowest levels since 1996 (Hahn et al. 2017).

All these concurrent changes have meant that many more mothers now assume primary financial responsibility for their children while still providing most of their custodial care. In many ways, the failure of the United States to develop a strong social safety net for families has left mothers as the de facto shock absorbers of a postindustrial occupational structure that produces growing instability in parents’ employment and relationships.

Conceptual and Methodological Challenges

The predominant methodological question to be addressed is how to define primary-earning status. For unpartnered women, this is fairly straightforward, although many unpartnered mothers in the data we use obtain substantial financial assistance from other co-resident family members (Cohn and Passel 2018). Estimating the proportion of dual-earner households with a primary-earning mother, however, is highly sensitive to the earnings threshold chosen (Raley, Mattingly, and Bianchi 2006; Winkler et al. 2005). Theoretically, primary-earning status is layered with gendered interpretations, and many see women’s financial contributions to the total family income as supplemental to men’s earnings, even when their contributions are objectively substantial (Reid 2018).2 Arguably, families are “dependent” on mothers’ earnings at relatively low thresholds, such as contributing 40 percent of families total earnings. Empirically, most studies evaluate primary-earner status at 51 percent of the total household income, a more moderate measure of dependency (Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan 2015; Manchester, Leslie, and Dahm 2019; Wang et al. 2013). Yet when wives are primary earners, they often earn a lower proportion of the family’s income than when fathers are primary earners, using this definition. Primary-earning wives account for 69 percent of couples’ earnings on average, while primary-earning husbands account for 82 percent, given the larger share of full-time homemakers in that group (Cohen 2013, 2016). This suggests a higher threshold for financial dependency on mothers’ earnings.

Ultimately, we chose to err on the conservative side, setting a threshold of 60 percent of total family earnings across an entire year for a mother to be considered the primary earner in her family and comparing mother’s earnings to all other sources of earnings in the family, including live-in romantic partners and other family members.

Method

Data

We used data from the 2014 panel of the SIPP, a longitudinal probability household survey data set collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. We chose the 2014 SIPP because it was the most recent panel available and had detailed household roster and income data from all sources. Producing estimates of transitions into and out of primary-earning status requires at least two or more waves of data, and completed waves of the 2018 SIPP panel have not yet been released. The first wave of the 2014 SIPP panel collected data on household characteristics in 2013. Data were collected on individuals living in sampled households and anyone living with these individuals every year through 2016. Our sample includes women whose oldest child was under 18 at the time of the first SIPP interview or who became mothers over the duration of the panel. We lose very few cases to missing responses to individual questions because the Census allocates data where it is missing, but the SIPP does have substantial sample attrition. Of the 9,126 mothers in the data, only 65 percent are observed for at least two consecutive years and thus included in our analysis (n = 5,961).

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics of the full sample of mothers and our analytical sample, respectively. About two-thirds of the analytical sample are married, about 11 percent of mothers reside with a partner, and the remaining 23 percent of mothers do not live with a partner. The differences between our analytic sample and the full sample are slight, but generally the analytical sample is more advantaged than the full sample. The analytical sample has a slightly higher percentage of married mothers, a slightly lower percentage of mothers who are primary earners, and their household earnings are higher. Again, these differences are likely to make our estimates of mothers’ primary earning more conservative, as married mothers are less likely to be primary earners.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Full Sample of Mothers and Analytical Sample, 2014 SIPP.

| All Mothers |

Analytical Sample |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % | M | % | M |

| Primary earner (60% threshold) | 26.9 | 26.1 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 9.9 | 9.5 | ||

| High school diploma/GED | 22.7 | 21.6 | ||

| Some college | 29.7 | 29.2 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 26.9 | 26.1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Spouse | 64.4 | 66.4 | ||

| Partner | 11.4 | 10.9 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 56.1 | 56.3 | ||

| Black | 13.7 | 13.2 | ||

| Hispanic | 7.1 | 7.6 | ||

| Asian | 2.4 | 2.2 | ||

| Multiracial | 20.7 | 20.6 | ||

| Age | 26.3 | 26.5 | ||

| Years since first birth | 9.7 | 9.6 | ||

| Personal earnings | 29,127.0 | 30,095.1 | ||

| Household earnings | 85,366.6 | 88,371.2 | ||

| Personal-to-household-earnings ratio | 0.475 | 0.502 | ||

| Unweighted N (individuals) | 9,126 | 5,961 | ||

Note: SIPP = Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Measures

The SIPP contains information on income from every household member in each month of each year. We construct annual estimates of dependency by summing mothers’ earnings in each month of the previous year and dividing by the total earnings of all household members in each month of the previous year. We create a dichotomous indicator of primary-earning status for every mother in every year available, indicating whether mothers’ earnings exceeded 60 percent of the total household earnings for that year. The resulting pool of primary-earning mothers contributed an average of 90 percent of total family earnings across all primary earning years, ensuring that we were indeed capturing true family dependency on mothers’ earnings.

Our key stratifying variables are mothers’ marital status at the time of the birth and mothers’ educational attainment at the time of the initial survey. We identify marital births as those occurring to mothers who had their first birth in the same year or after the year of their first marriage. The SIPP does not have month of first marriage/birth, so we cannot make a clean determination of marital status at the time of the birth. Births that occur in the year of marriage may be premaritally conceived but result in rapid transition to marriage so are coded as marital births. To do otherwise noticeably reduces the gap in primary earning between marital and nonmarital births, suggesting that those who marry quickly following a premarital conception are more gender traditional on average. We classified mother’s educational attainment into four categories: less than a high school degree, a high school degree, some college, and bachelor’s degree receipt or higher. In the analytic sample, about 22 percent of mothers had only a high school diploma, whereas 26 percent of mothers had obtained a college degree by the time of the initial survey. The modal category was some college.

Analytic Strategy

To calculate mothers’ average number of years spent as primary earners, we conduct a period multistate life table analysis using the LXPCT_2 Stata module (Weden 2005) with estimates of mothers’ transitions into (and out of) primary-earner status by duration since the birth of their first child as inputs. The origin state for all women is nonmother, the year prior to her first giving birth. In the year mothers first give birth, women transition into one of four states: (1) not living with biological children, (2) non-primary-earning mother co-residing with children, (3) primary-earning mother living with children and living with other adults, or (4) primary earning mother living with no other adults at least some of the year. These transition rates are available in Appendix Table A1. This table shows that 15.4 percent of mothers transition into motherhood as a primary earner (from status 1 = not living with biological children to state 3 = primary-earning mother). Most (72.0 percent) mothers transition into motherhood without being primary earners. Another 12.6 percent of mothers are not living with their first-born infant. The Census Bureau estimates that only 6.4 percent of all infants live apart from their mothers (U.S. Census Bureau 2019). It is probable that the proportion is higher for first-born children who have younger-than-average mothers, but it is also likely that the SIPP household roster misses some infants (America Counts Staff 2019). Thus, we probably overestimate to a small degree the proportion of mothers living apart from children. All in all, the most common status for mothers is living with children in a household in which they are not a primary earner. Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of mothers transition into primary-earner status (see transition rates presented in Appendix Table A1) at every duration since the year of their first birth. Note that these are period estimates, similar to total fertility rates. They are calculated based on rates experienced at a specific historical period, in this case, 2013 to 2016. They do not reflect the actual experience of any cohort of mothers but are synthetic descriptions based on the experiences of mothers at any duration of motherhood, from just transitioning in to their 18th year between 2013 and 2016. Yet to the extent that historical change is gradual, they are not far off the experiences of real cohorts.

To calculate the proportion of mothers that ever experience primary-earner status, we use a standard single-decrement period life table approach (Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001). A single-decrement approach is appropriate because we are counting transitions into primary earning for any reason. Women start the life table never having been a primary-earning mother, and we estimate the cumulative probability of “surviving” (i.e., not transitioning into primary-earner status) over the first 17 years of motherhood based on the following formula:

Ideally, our estimate would be based on a set of motherhood-duration-specific probabilities of transitioning into primary-earner status for the first time. Because the SIPP panel lasts only four years, we are not following actual cohorts of mothers over time and are unable to calculate the probability of transitioning into primary-earning status for the first time ever. Instead, we can calculate only the probability of transitioning since first observation. Thus, in our analysis, PEd is the sum of FPEd (first-time primary-earning mothers) and PPEd (primary-earning mothers who had been primary earners prior to the first observation), and Md is the number of mothers who have never been a primary earner plus the number of mothers who have previously but were not currently primary earners since 2013. If the risk of becoming a primary earner were the same for mothers who had never previously been a primary earner as for mothers who had experience as a primary earner prior to 2013, then we could ignore the distinction. An analysis of the SIPP data showed that being the primary earner in 2013 predicted a return to that status in 2015 among those who stopped primary earning in 2014. Consequently, this approach likely overestimates the probability of primary-earner status because it cannot account for mothers who were primary earners prior to our first observation.

To determine how much of an overestimate unobserved repeat spells as a primary earner might be, we turned to the National Longitudinal Surveys 1997 (NLSY) sample, which contains a complete earnings history through the duration of the first years of motherhood for a nationally representative sample of women who were 12 to 16 years old in 1996 and ages 31 to 35 at last observation in 2015. While challenging to separate age at motherhood from period effects using the NLSY cohort data, the data do provide some information about the scale of overestimation in the SIPP. Because of the age of the NLSY respondents, we were able to calculate transitions into primary earning from the year they first became mothers until their first child turned eight years old.

A comparison of the NLSY-based annual transition rates and the SIPP-based annual transition rates showed remarkably similar estimates until duration 5 (see Appendix Table A2). The average ratio of the NLSY-based transition rate to SIPP-based transition rate for durations 5 through 7 was .62, consistent with our suspicion that the SIPP produces overestimates by including some mothers who had previously been primary earners. Therefore, to adjust our SIPP-based estimates for the unobserved repeat breadwinning possibility in the SIPP, we multiplied our transition rate for durations 5 through 17 by .62.

An alternative but more conservative approach would be to assume that the bias in the SIPP estimate of the probability of a mother transitioning into primary-earner status for the first time monotonically increases as her period at risk lengthens (her firstborn child gets older) and women who have never previously been a primary earner become increasingly “select” such that the gap between FPEd and PPEd grows. If so, the sensible approach would be to use the available data points of the NLSY97/SIPP ratios for durations 5 through 7 to forecast the growth in the bias in the SIPP estimate of first entrances into primary-earner status through duration 17. Appendix Table A2 provides those data points, which yield a 15 percent decline in the ratio of the NLSY to the SIPP at each subsequent duration. Maintaining that proportionate decline through duration 17 yields significantly lower estimates of primary earning than the averaging method using the same data points for durations 5 through 7. For this reason, we report both results, using the conservative model as a lower-bound estimate.

However, there are substantial reasons to believe that these lower-bound estimates are too conservative. First, these estimates predict extremely low increases in first-time entrances into primary earning for mothers of teens ages 13 to 18 (cumulatively around 2 percent). Yet the divorce rate among mothers of teens is assuredly higher (around 11 percent of married mothers in recent research), and other partnered mothers will increase their hours and earnings as their children become more independent and higher education expenses loom larger in their future (Fox et al. 2013; Waite and Lillard 1991). These facts suggest that the rate of first-time entrances into primary earning may flatten among mothers of teens rather than continue to decelerate at every duration of motherhood. Second, our estimates already truncate the duration of motherhood at 18 years even though many women remain mothers of dependent children well beyond that point. Finally, our results likely suffer from conservative bias in the reporting of self and partner earnings (Murray-Close and Heggeness 2018) and in the proportion of marital births represented, again lowering the cumulative risk estimate of becoming a primary earner.

In our single-decrement life table, mothers can transition into primary earning only when living with minor children, but we keep mothers in our analytic sample throughout their first 18 years of motherhood to estimate average duration as primary earner—even when they do not live with children. If we were to censor observations of mothers no longer living with children, our estimates of duration would be higher. Replication code for data access and paper analyses are available at https://github.com/jrpepin/Breadwinner/releases/tag/socius.

Results

Figure 1 presents the results from our multistate life table analysis. It shows that, in the 18 years following their first birth, American mothers average 4.19 years as primary earners, divided into 2.18 years on average as a single earner and 2.01 years in a multiearner household (usually but not always including a partner). Mothers who do not have a high school diploma spent the least amount of time as primary earners, about 3.07 years on average. Compared with other mothers, mothers with some college education but no diploma (our modal category) spent the most years as primary earners, about 5.09 years on average. Divided into years as a solo earner and years sharing financial provision with other co-resident adults (mostly but not exclusively romantic partners), we find that educational attainment consistently increases years spent provisioning as a single earner from 0.78 years for those with no high school degree to 2.56 years for those with a college degree or more. However, years spent as a primary earner with other adult earners in the household show an inverted U shape, with years increasing as educational attainment moves from no degree to some college, then dropping among college graduates who are presumably most likely to partner with high-earning men.

Figure 1.

Estimated years spent as a primary earner during the first 18 years of motherhood.

Perhaps not surprisingly, those mothers having a marital first birth experience both fewer total years as primary earner for their family and more of those years as a single parent (2.26 out of 3.35 years on average as primary earner), illustrating a pattern of secondary-earner status among college-educated moms in partnered households until divorce or separation propels them into sole earning. Mothers having a nonmarital first birth, by contrast, average 5.69 years as primary earners, with only 1.97 of those years as a single parent and the rest sharing earning with other family members, illustrating a pattern of low partner earnings and household extension following relationship dissolution.

The results in Figure 1 indicate that the average mother experiences many years as a primary earner across differences by education and marital status. Expressed as a proportion of all years living with their first child, mothers with some college spend a third of those years on average as primary earners, as do mothers with nonmarital first births.3 Yet the average may be the result of a small proportion of women experiencing most of their years as primary earners, offset by a large proportion who never provide most of the financial support to their family. How typical is the experience of being a primary-earning mother over the life course, and what is the average duration among those who ever transition into becoming the primary earner? These numbers add meaningful dimension to our understanding how many American mothers are likely to experience primary-earner status before their firstborn reaches adulthood and how long they will likely stay in that status. Using a constant discount rate over durations 5 to 17 to correct for spells of repeat breadwinning, our single-decrement life table findings show that 70 percent of mothers can expect to be primary earners (defined as mothers’ share of total household earnings exceeding 60 percent over a given year) at some point within the first 18 years of motherhood. Using the more conservative “proportionately increasing” discount rate over durations 5 to 17, our estimate drops to 60 percent of all mothers eventually becoming primary earners before their first child turns 18, still substantially higher than the cross-sectional data indicating 42 percent of mothers are primary earners at any given point in time (Glynn 2016).

Figure 2 presents estimates of the proportion of mothers who will ever be primary earners during their first 18 years of motherhood, disaggregated by mothers’ education and marital status at birth. Using a constant discount for estimation, 62 percent of mothers who do not have a high school diploma will support their households at some time during the first 18 years of motherhood. The proportions among mothers with greater educational attainment are substantially higher. About 71 percent of mothers with college degrees will at some point bring in more than 60 percent of household earnings during their first 18 years of motherhood, and a whopping 76 percent of mothers who attend college but do not obtain a degree will at some point hold the primary financial responsibility for their household. This group of mothers also averaged the most years as a primary earner (see Figure 1). Results again indicate an inverse U-shaped relationship between mothers’ levels of human capital and their financial responsibility for their households. Using the more conservative, proportionately increasing discount rate yields lower estimates of primary earning but still shows substantial majorities of mothers in all educational groups (except those without high school degrees) will eventually be primary earners.

Figure 2.

Proportion of mothers who become primary earners during the first 18 years of motherhood.

Results broken down by marital status at first birth show a consistent pattern, as well. Mothers with marital first births face a 65 percent probability of ever becoming the primary earner for their family while rising to 80 percent for those mothers with nonmarital first births, with conservative lower-bound estimates of 54 percent and 70 percent, respectively.

By combining our estimates of duration (Figure 1) with our estimates of the proportion ever primary earning (Figure 2), we find that the 70 percent of mothers who ever transition into breadwinning spend almost 6.2 years on average as the primary earner. Broken down by level of educational attainment, among mothers who have ever been a primary earner, mothers with less than a high school education average 4.95 years in that status, moving to 6.10 years for those mothers with a high school degree and 6.7 years for mothers with some college, then dropping to 5.35 years for mothers with a college degree or higher.

Discussion

Despite the persistence of conventional gender norms around male breadwinning, families are increasingly dependent on mothers’ economic resources (Glynn 2016). Our estimates show the duration American mothers spend as primary earners, defined as exceeding 60 percent of the total family earnings, averages about 4.19 years in the 18 years following the birth of their first child. American mothers’ cumulative probability of ever holding primary-earner status for at least one year was 70 percent using synthetic cohort estimates, with a conservative lower bound of 60 percent. Mothers who had some college experience but no college degree had the longest duration of primary-earning status (5.09 years) and were more likely than other mothers to ever be primary earners (76 percent). Yet, even among women without a high school degree, the group with the least experience as primary earners and least well situated to provide for their families, over 60 percent are likely to spend at least a year earning the majority of their household’s resources.

We think that it is interesting and remarkable that half of mothers have been primary earners for their households by the time their first child is age 8 in the most stringent specification. Whether an additional 10 to 20 or even 30 percent of the mothers become primary earners by the time that first child is 18, we cannot be completely certain with the synthetic cohort data available. But the number is certainly large enough even in the most conservative calculations to suggest that maternal financial provisioning for their children is becoming a ubiquitous experience for large swaths of American families.

These findings demonstrate that mothers’ “breadwinning” is a broad phenomenon worthy of further attention. U.S. mothers are far more likely to be a primary earner at some point in their first 18 years of motherhood than to never find themselves in this status. Although the data reveal important differences among mothers by education and marital status in the length of these primary-earning spells, the results suggest that all kinds of mothers spend a nontrivial amount of time as their family’s primary earner. These numbers, moreover, represent truncated estimates given that (a) many children continue to live at home after age 18 and (b) a substantial number of mothers have more than one child and are therefore at risk for longer than the first 18 years of motherhood. Overall, the final tallies indicate many more mothers, for longer durations, are primary family earners than is recognized by employer practices and government policies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted children’s continued dependency on their mothers as primary caregivers, and partly because of their role as primary caregivers, mothers have experienced the greatest job loss in the current crisis (Barroso and Kochhar 2020; Petts, Carlson, and Pepin 2020). Reports of rampant downsizing of mothers’ paid work hours and earnings combine (a) the involuntary unemployment of some who will return as soon as possible to full-time employment and (b) the voluntary career stops of mostly highly educated, married mothers whose children can survive without their full-time earnings while they provide schooling and full-time care at home (Grose 2020). Both groups may in fact suffer losses in long-term earnings growth because of the pandemic, and time will tell how permanent these losses are and for whom. Given that our findings show how common children’s reliance on their mothers’ earnings has become across all levels of maternal human capital, for many families, the long-term economic consequences of their COVID-19 related employment interruptions may be severe.

Mothers’ growing role as their family’s provider is the result of long-term societal trends that are unlikely to quickly reverse. Nonetheless, current labor policies continue to focus on male employment and earnings, such as those that promote and fund vocational training for young men or aim to support blue-collar industrial employment (Sutton, Bosky, and Muller 2016). Rhetoric during the pandemic has reinforced this preoccupation with men’s employment, with former President Trump assuring voters, “I’m also getting your husbands—they want to get back to work, right? . . . We’re getting your husbands back to work, and everybody wants it” (Bump 2020). Such a focus will inadequately serve mothers likely to become the primary or sole earner for their families. The gender wage gap and the “motherhood penalty” in hiring and promoting women become more immediate and pressing problems given their broad impact on the economic security of those American children increasingly dependent on their mothers’ earnings. If the pandemic seriously erodes the capacity of American mothers to support their children through paid employment, and fathers, employers, and government do not change their current patterns of support, then American children will pay the price of mothers’ reduced economic circumstances (Schneider, Hastings, and LaBriola 2018).

Differences in mothers’ personal circumstances (e.g., age at first birth, marital status, education, occupation, and work history) may further explain for whom this transfer of the financing of American childhood has been most acute. Short-term losses among mothers in employment and earnings brought about by the pandemic may not offset the long-term growth in family dependency on mothers’ earnings, especially as the proportion of children in married-couple households continues to fall (Livingston 2018). Future work should unpack in greater detail the avenues into primary-earning status, focusing on the range of circumstances that push and pull U.S. mothers into primary-earning status. Knowing the precipitating factors and groups with highest propensity to become principal economic providers for their children will help scholars and policy makers decipher the implications of mothers’ new economic responsibilities and develop employment policies accordingly.

Funding

This research was supported by grants P2CHD042849 and T32HD007081 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grant P30AG066614 from the National Institute on Aging to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Author Biographies

Jennifer L. Glass is the Centennial Commission Professor of Liberal Arts in the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Her published research focuses on work and family issues, gender stratification in the labor force, mother’s employment and mental health, and religious conservatism and women’s economic attainment. Her most recent projects explore whether governmental work–family policies improve parents’ and children’s health and well-being, whether women’s jobs really have better work–family amenities than men’s, why women’s retention in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics occupations remains so abysmally low, and how the economic costs of motherhood have changed over time, all in part to understand the roots of women’s disadvantage in the labor market.

R. Kelly Raley is a professor of sociology and a faculty research associate at the Population Research Center and holds the Christine and Stanley E. Adams Jr. Centennial Professorship in Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research investigates family trends and the changing social determinants of family formation. As part of her broad agenda examining the economic and other social-structural contributors to marriage disparities in the United States, she investigates the influence of occupational characteristics and other forms of inequality on the transition into marriage in early adulthood. Much of her work in this area has addressed racial and ethnic differences in marriage and cohabitation, and her current line of inquiry adds a focus on educational variation.

Joanna R. Pepin is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the University at Buffalo (SUNY). She studies inequality related to family composition and couples’ divisions of paid work, housework, and carework.

Appendix

Table A1.

Estimates of Maternal Primary-Earning Transition Rates by Duration since First Birth.

| Age | p11 | p12 | p13 | p14 | p21 | p22 | p23 | p24 | p31 | p32 | p33 | p34 | p41 | p42 | p43 | p44 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| 2 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| 3 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.62 |

| 4 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| 5 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.47 |

| 6 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.86 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.50 |

| 7 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.58 |

| 8 | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.55 |

| 9 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.68 |

| 10 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.60 |

| 11 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.52 |

| 12 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.53 |

| 13 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.67 |

| 14 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.64 |

| 15 | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.57 |

| 16 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| 17 | 0.83 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| 18 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.61 |

Note: Primary earning defined at the 60 percent threshold. Column headings “pxy” refer to the transition rate from status x at the previous duration to status y at this duration (1 = not living with children; 2 = living with children, not primary earner; 3 = primary earning mother and living with other adults; 4 = primary earning mother living with no other adults at least some of the year).

Table A2.

Estimates of Transition into Primary Earning for the First Time, NLSY97 and SIPP.

| Unadjusted SIPP |

Adjusted SIPP |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Motherhood | NLSY97 | Yearly Probability of Transitioning to Primary Earning | Survival | Cumulative Survival | Yearly Probability of Transitioning to Primary Earning | Survival | Cumulative Survival |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| 2 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.70 |

| 3 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.63 |

| 4 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.59 |

| 5 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.55 |

| 6 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.52 |

| 7 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.49 |

| 8 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.47 | |

| 9 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.45 | |

| 10 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.42 | |

| 11 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.40 | |

| 12 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.38 | |

| 13 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.36 | |

| 14 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.35 | |

| 15 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.33 | |

| 16 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.31 | |

| 17 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.30 | |

Note: NLSY97 = National Longitudinal Surveys 1997; SIPP = Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Footnotes

Author calculations based on the 1990–2000 Decennial Census and 2010–2017 American Community Surveys.

For this reason, we avoid the use of the term breadwinner, as that is an ideological construction associated with masculine role performance that mothers may or may not identify with, even as they provide the bulk of family income for years on end.

Strong racial/ethnic differences in educational attainment and family formation behaviors result in large ethnic differences in the duration of time mothers spend as primary earners as well, with African American mothers averaging almost seven years as primary earners before their firstborn turns 18, while Hispanic and white mothers average 3.88 and 4.06 years, respectively (results not shown but available from authors).

References

- America Counts Staff. 2019. Big Push to Count Every Newborn and Young Child in 2020 Census Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso Amanda, and Kochhar Rakesh. 2020. “In the Pandemic, the Share of Unpartnered Moms at Work Fell More Sharply Than among Other Parents” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/24/in-the-pandemic-the-share-of-unpartnered-moms-at-work-fell-more-sharply-than-among-other-parents. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand Marianne, Kamenica Emir, and Pan Jessica. 2015. “Gender Identity and Relative Income within Households.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(2):571–614. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjv001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budig Michelle J., and England Paula. 2001. “The Wage Penalty for Motherhood.” American Sociological Review 66(2):204–25. doi: 10.2307/2657415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bump Philip. 2020. “With a Week Left, Trump Modifies His Pitch to Suburban Women: He’ll Get Their Husbands Back to Work.” Washington Post, October 27. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/10/27/with-week-left-trump-modifies-his-pitch-suburban-women-hell-get-their-husbands-back-work/.

- Catalyst. 2020. “The Impact of Covid-19 on Working Parents” https://www.catalyst.org/research/impact-covid-working-parents.

- Cohen Philip. 2013. “For Married Mothers, Breadsharing Is Much More Common Than Breadwinning.” Family Inequality https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/bread-sharer-breadwinner.

- Cohen Philip. 2016. “Why Male and Female ‘Breadwinners’ Aren’t Equivalent (in One Chart).” Family Inequality http://www.familyinequality.wordpress.com/2016/05/31/why-male-and-female-breadwinners-arent-equivalent-in-one-chart.

- Cohn D Vera, and Passel Jeffrey S. 2018. “Record 64 Million Americans Live in Multigenerational Households” Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 25, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational-households/.

- Collins Caitlyn, Liana Christin Landivar Leah Ruppanner, and Scarborough William J. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours.” Gender, Work & Organization doi: 10.1111/gwao.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Correll Shelley J., Benard Stephen, and Paik In. 2007. “Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty?” American Journal of Sociology 112(5):1297–1339. doi: 10.1086/509519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson EJ 2020. “Coronavirus Is Killing the Working Mother.” Rolling Stone https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/working-motherhood-covid-19-corona-virus-1023609.

- Eggebeen David J. 2002. “The Changing Course of Fatherhood: Men’s Experiences with Children in Demographic Perspective.” Journal of Family Issues 23(4):486–506. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02023004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Liana, Han Wen-Jui, Ruhm Christopher, and Waldfogel Jane. 2013. “Time for Children: Trends in the Employment Patterns of Parents, 1967–2009.” Demography 50(1):25–49. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn Sarah Jane. 2016. Breadwinning Mothers Are Increasingly the U.S. Norm Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Gonalons-Pons Pilar, and Schwartz Christine R. 2017. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography 54(3):985–1005. doi: 10.1007/s13524-017-0576-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose Jessica. 2020. “Mothers Are the ‘Shock Absorbers’ of Our Society” New York Times, October 14. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/14/parenting/working-moms-job-loss-coronavirus.html. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn Heather, Okoli Adaeze, Aron Laudan, Lou Cary, and Pratt Eleanor. 2017. Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live? How and Why State TANF Programs Vary Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. 2018. Precarious Lives: Job Insecurity and Well-Being in Rich Democracies Cambridge, UK: Polity. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Rosalind Berkowitz. 1999. “Time Spent in Parenthood Status among Adults in the United States.” Demography 36(3):377–85. doi: 10.2307/2648060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert Susan J., Henly Julia R., and Kim Jaeseung. 2019. “Precarious Work Schedules as a Source of Economic Insecurity and Institutional Distrust.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5(4):218–57. doi: 10.7758/RSF.2019.5.4.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Ken Hou, and Tobias Neely Megan. 2020. Divested: Inequality in the Age of Finance New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston Gretchen. 2018. The Changing Profile of Unmarried Parents Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester Colleen Flaherty, Leslie Lisa M., and Dahm Patricia C. 2019. “Bringing Home the Bacon: The Relationships among Breadwinner Role, Performance, and Pay.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 58(1):46–85. doi: 10.1111/irel.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close Marta, and Heggeness Misty L. 2018. How Husbands and Wives Report Their Earnings When She Earns More. SESHD Working Paper No. 2018–20 Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Petts Richard J., Carlson Daniel L., and Pepin Joanna R. 2020. “A Gendered Pandemic: Childcare, Homeschooling, and Parents’ Employment during COVID-19.” Gender, Work & Organization doi: 10.1111/gwao.12614. [DOI]

- Preston Samuel, Heuveline Patrick, and Guillot Michel. 2001. “The Life Table and Single Decrement Processes.” Pp. 38–70 in Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Raley Sara B., Mattingly Marybeth J., and Bianchi Suzanne M. 2006. “How Dual Are Dual-Income Couples? Documenting Change From 1970 to 2001.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68(1):11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00230.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid Erin M. 2018. “Straying from Breadwinning: Status and Money in Men’s Interpretations of Their Wives’ Work Arrangements.” Gender, Work & Organization 25(6):718–33. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risman Barbara J. 2020. “Will COVID-19 Push Women Out of the Labor Force?” Psychology Today https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/gender-questions/202007/will-covid-19-push-women-out-the-labor-force.

- Schneider Daniel, Hastings Orestes P., and LaBriola Joe. 2018. “Income Inequality and Class Divides in Parental Investments.” American Sociological Review 83(3):475–507. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton April, Bosky Amanda, and Muller Chandra. 2016. “Manufacturing Gender Inequality in the New Economy: High School Training for Work in Blue-Collar Communities.” American Sociological Review 81(4):720–48. doi: 10.1177/0003122416648189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Rachel, Cooper Marianne, Cardazone Gina, Urban Kate, Bohrer Ali, Long Madison, Yee Lareina, Krivkovich Alexis, Huang Jess, Prince Sara, Kumar Ankur, and Coury Sarah. 2020. Women in the Workplace: 2020 New York: McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2019. Social and Economic Supplement

- Waite Linda J., and Lillard Lee A. 1991. “Children and Marital Disruption.” American Journal of Sociology 96(4):930–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Wendy, Parker Kim, and Taylor Paul. 2013. Breadwinner Moms: Mothers Are the Sole or Primary Provider in Four-in-Ten Households with Children. Social & Demographic Trends Project Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Weden Margaret. 2005. LXPCT_2: Stata Module to Calculate Multistate Life Expectancies

- Winkler Anne E., McBride Timothy D., and Andrews Courtney. 2005. “Wives Who Outearn Their Husbands: A Transitory or Persistent Phenomenon for Couples?” Demography 42(3):523–35. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women’s Bureau. 2016. Working Mothers Issue Brief Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]