June 6, 2022

Background

In 2018, the National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM’s) Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic was established to catalyze public, private, and nonprofit stakeholders to develop, curate, and implement multi-sector solutions designed to reduce opioid misuse and improve outcomes for individuals, families, and communities affected by the opioid crisis (NAM, n.d.). The Action Collaborative’s diverse members work together to advance initiatives organized into the following priority areas, which are also the focus of its work groups: health professional education and training; pain management guidelines and evidence standards; prevention, treatment, and recovery services; and research, data, and metrics needs.

Specifically, the Health Professional Education and Training Work Group authored a Special Publication in 2021 titled Educating Together, Improving Together: Harmonizing Interprofessional Approaches to Address the Opioid Epidemic (Chappell et al., 2021). This Special Publication analyzed professional practice gaps (PPGs) across five professions and the current requirements landscape pertaining to pain management and substance use disorder (SUD) care. The results of the analysis elucidated highly variable education needs and requirements and an underlying urgency for harmonization across the broader health system. To address unwarranted variation and accelerate action around shared goals, the Special Publication highlights five priorities for health education and training stakeholders to catalyze substantive and lasting change in the opioid crisis response. The first of these five priorities is to establish minimum core competencies in pain management and SUD for all health professionals and support evaluation and tracking of health professionals’ competence. Minimum core competencies aim to set a standard for the minimum level of competence expected from all health care professionals and should help systemize tracking and evaluation of appropriate competence in pain management and SUD care.

To advance this priority, the Education and Training Work Group developed a core competency framework for pain management and unhealthy substance use care, including SUD care. The core competency framework describes the knowledge, skills, attitudes, qualifications, and behaviors that are needed to address PPGs across pain management and unhealthy substance use care and can strengthen the delivery of coordinated, high-quality, and person-centered care. Additionally, the framework acknowledges commonalities shared between pain and SUD while recognizing both as separate and multifaceted conditions with potential intersections. Given that affected individuals often have complex health and social needs, the competency framework is designed to help health care professionals and the broader health system understand the interrelation and aspects of both conditions independently, collectively, and contextually (Gatchel et al., 2014; Saitz et al., 2008).

The core competency framework aims to improve pain and unhealthy substance use care by building upon previous frameworks, emphasizing interprofessional team-based care, and supporting the advancement of innovations across the health professions. For the purpose of this work, the framework’s reliance on context is adapted from the Interprofessional Consensus Summit’s work on advancing pain curricula, specifically the need to reduce emphasis on learners acquiring factual knowledge and increase emphasis on learners’ “capacity to act effectively in complex, diverse, and variable situations” (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016).

Framework Scope and Overview

The core competency framework is comprehensive and interprofessional in its construction and aims to inform a standard that can be adapted to different professions, settings, and contexts. The content of the framework includes distinct foundational concepts that apply to pain, unhealthy substance use, relevant mental health conditions, and any potential intersections. To address PPGs and ensure health care professionals demonstrate competence in these domains, concepts included in the framework should be incorporated into education, training, and evaluation across the continuum of a health professional’s career. While the implementation of the competency framework will help to close PPGs, it may also serve as a foundation for health care professional practice and lead to improved patient- and family-centered care and community partnerships, strengthened interprofessional coordination and collaboration, and enhanced readiness and responsiveness of the health care system (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011). Notably, the framework outlines domains, general competencies, and supporting sub-competencies, not specific or prescriptive competencies. This is intentional, as the framework should serve as a tool for strengthening existing competencies or developing new competencies as needed and can guide updates to current requirements and standards.

The framework incorporates key components of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to define qualifications and behaviors that will better prepare all health professionals across the continuum to address pain and unhealthy substance use (Baker et al., 2003; Salas and Cannon-Bowers, 1997; Cannon-Bowers et al., 1995; AHRQ, n.d.). These baseline components are summarized into a core list of three broad, interprofessional performance domains, with general competencies and sub-competencies under each that can be used to support or develop profession- or specialty-specific competencies as needed. In addition to seeking to address PPGs and improve quality care, the domains and competencies also serve as a bridge for disciplines that lack sub-specialization in pain management, such as dentistry and orofacial pain, or disciplines with emerging specialties, such as pain psychology. The framework is designed to be simple, practical, and widely applicable across health professions and the continuum of education and training.

Development Process

Developing the core competency framework was an iterative process that started with a broad environmental scan of existing competency frameworks and curricula on pain- and SUD-related topics. Action Collaborative members and their respective networks provided a diverse sample of 25 curricular formats (guidelines, standards, recommendations, educational blueprints, and systemic reviews) intended for a range of professions and disciplines across the pre-licensure and post-licensure education and training levels. These disciplines included allopathic, osteopathic, dental, pharmacy, nursing, social work, psychology, psychiatry, and physical therapy. The main focus areas of the existing curricular formats included acute and chronic pain management, SUD treatment, opioid prescribing, mental/behavioral health, prevention, and a range of other topics that were profession- or specialty-specific or interdisciplinary topics within the realm of pain and SUD care.

Core content, domain categories, and structural organization from the sample frameworks were summarized into a table (see Appendix A) and further analyzed for overlapping themes, gaps, and key takeaways (see Appendix B). The content of the frameworks was then mapped to the PPG findings from the Special Publication to identify cross-cutting themes. Members of the Education and Training Work Group developed an initial list of domain areas that were then expanded, using the results from the environmental scan and the subsequent thematic analysis. The resulting content was organized into domains, general competencies, and sub-competencies. The domains and general competencies were largely chosen based on their relevance to and inclusion in existing frameworks (AHRQ, 2019; Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016). Sub-competencies were developed to address educational needs across pain management and unhealthy substance use care. The development of the domains, general competencies, and sub-competencies was an iterative process, as over 10 drafts were reviewed by members of the Education and Training Work Group and further refined and reorganized based on their input. Once the content of the general competencies and sub-competencies was determined, the domains were further refined into interprofessional performance domains. The general competencies were then mapped to the domains, which collectively indicate competence. These components, along with foundational concepts of partnership, learning, collaboration, and continuous improvement were assembled to create a framework.

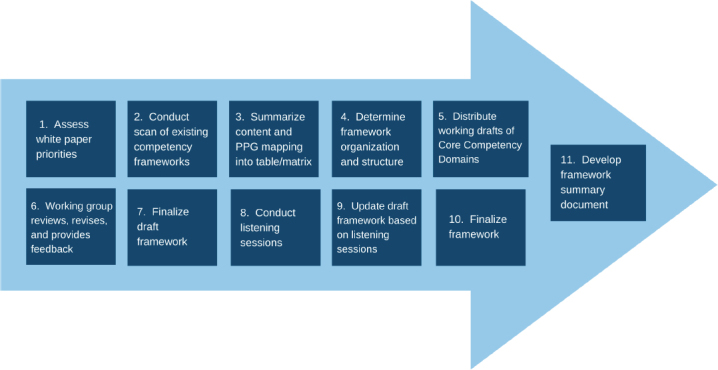

FIGURE 1. Summary of the Development Process.

SOURCE: Holmboe, E., S. Singer, K. Chappell, K. Assadi, A. Salman, and the Education and Training Working Group of the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. 2022. The 3Cs Framework for Pain and Unhealthy Substance Use: Minimum Core Competencies for Interprofessional Education and Practice. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202206a.

NOTE: Figure 1 summarizes each major step in the development process for the Core Competency Domains Framework.

The draft core competency framework was then presented and discussed during a series of closed listening sessions hosted by the Action Collaborative. The purpose of the listening sessions was to gather feedback from a range of end-users and health care stakeholders on the clarity, content, and usability of the framework. Each listening session included a broad and diverse set of practicing health care professionals and health system stakeholders involved in developing, implementing, and measuring clinical competencies, as well as clinicians currently in training and individuals with pain and SUD lived experience. Feedback from the listening sessions was summarized and used to further refine the framework. The updated framework was again presented to members of the Education and Training Work Group, who helped further refine and finalize the sub-competencies and core elements of the framework.

Framework Structure and Content

The resulting framework is centered on partnering with patients, families, and communities, which includes but is not limited to engaging in shared decision making, learning with and from patients and families, and including lived experience perspectives in education and continuous improvement (Dokken et al., 2021; SAMHSA, 2021; Dardess et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2003). A key aspect of partnership in pain and unhealthy substance use care requires clinicians to recognize their patients’ unique circumstances and foster solidarity in overcoming challenges to “meet patients where they are” (Fishman et al., 2013; Sartorius, 2002; Cannon-Bowers et al., 1995). An inclusive definition of “family” is central to ensuring functional and fruitful partnerships and should be based on patients’ preferred definition of family. This concept of partnership is built on the importance of patient and family involvement in ensuring and maintaining safety and high-quality care, as well as improving health outcomes (Dokken et al., 2021; Dardess et al., 2018). Similarly, in this context, community engagement embraces an expansive definition of community. Community should include feelings of association due to shared attitudes, interests, goals, or geographical space, which can create or facilitate systems of support for information or resource exchange (Simona Kwon et al., 2017). Recognition of patients and families as part of broader communities is critical to effective engagement and partnership.

In addition to partnership, the framework incorporates two important facilitating factors that are needed to translate the identified domains and competencies to achieve expected outcomes. One of these facilitating factors is continuous learning and improvement, and the other is interprofessional collaboration and learning (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016; AHRQ, 2015).

Continuous learning and improvement are connected concepts that should be embedded across the continuum of education and are relevant to systems, individuals, and their interactions. This mutual responsibility at the macrosystem and microsystem levels is built on the principles of learning and coproduction (Elwyn et al., 2020). Learning health systems recognize individuals, teams, and systems as having distinct yet interdependent roles, and places value on working together across levels to transform health care delivery (IOM, 2011). At the macro level, systems must ensure that health care professionals receive effective, timely continuing education that is sensitive to setting and patient population needs. Individual health care professionals should be oriented toward lifelong learning and continuous improvement in clinical practice (IOM, 2010). At the micro level, health care professionals are responsible for translating scientific knowledge, best practices, and policy applications into health care delivery while engaging in co-learning and co-production with patients. It is critical for health care professionals to engage in continuous learning and improvement practices to stay informed and learn the skills needed to ensure safe, effective, person-centered, and equitable care delivery across diverse settings (IOM, 2010).

Continuous learning and improvement require individuals and systems to work synergistically to improve performance and patient outcomes (Wilcock et al., 2009). One of the foundational components of this process is assessment and evaluation. Assessment and evaluation provide the infrastructure to reinforce and strengthen continuous improvement in practice. Performance-based assessments, specifically, emphasize optimizing learning, prioritizing feedback and formative processes, and evaluating what a learner does in practice (Moore et al., 2009). In this process, both the individual and the system learn from each other to uphold the principles of continuous learning and improvement.

Interprofessional collaboration and learning rely on foundational respect, which includes equal recognition of all members of the care team and an understanding of environmental context. When thinking of the care team, it is important to note that individual patients, family members, and their communities serve as key team members. Fostering trust and using codesign principles is essential to collaborating with patients (Boyd et al., 2012; Bechtel and Ness, 2010). For successful collaboration to occur within and across all professions in the care delivery process, stakeholders must strengthen coalitions throughout the health care system (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016; AHRQ, 2015; AHRQ, n.d.). Learning through collaboration enhances care delivery to better meet the complex, individual needs of patients and families (IOM, 2003). By understanding how the care team collectively and individually functions within the health care system, interprofessional collaboration can improve access to comprehensive, coordinated, and high-quality care, whether through hands-on care or referrals.

Of note, these facilitating factors apply to clinical and non-clinical stakeholders. In addition to patients, their families and communities, clinicians, and health systems, groups such as payers, licensees, regulators, and educators are a critical part of the broader health care ecosystem and play a fundamental role in the framework’s implementation and long-term sustainability.

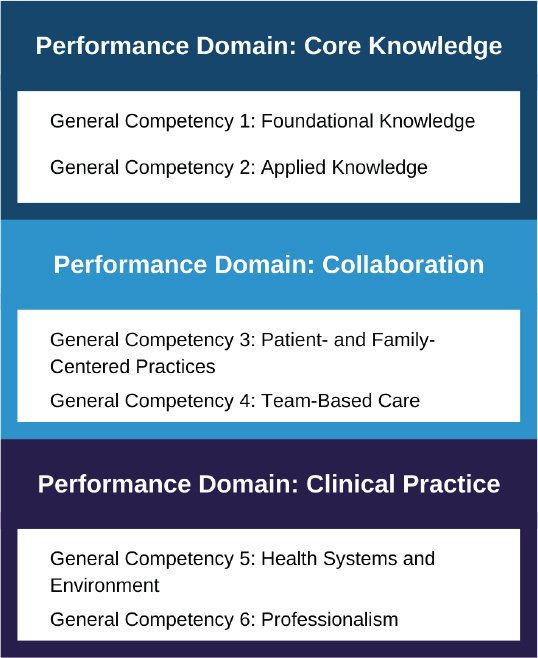

Building on the central components described above, the framework is further organized into three broad domains of performance that encompass needed knowledge, skills, and attitudes and reflect competence for all health professionals: Core Knowledge, Collaboration, and Clinical Practice (Dokken et al., 2021; Dardess et al., 2018). These three overarching performance domains map to six general competency areas (and their associated sub-competencies) describing core competency and termed the “3Cs Core Competency Framework for Pain Management and Unhealthy Substance Use Care” (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Core Domains and Competencies.

SOURCE: Holmboe, E., S. Singer, K. Chappell, K. Assadi, A. Salman, and the Education and Training Working Group of the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. 2022. The 3Cs Framework for Pain and Unhealthy Substance Use: Minimum Core Competencies for Interprofessional Education and Practice. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202206a.

Each of the general competencies contains several sub-competencies. The sub-competencies are interconnected both within and across all domains of the framework. For example, stigma is particularly salient for those who experience pain or unhealthy substance use. Concepts related to stigma are represented in several sub-competencies and integrated across all domains. The learning concepts reflected in the sub-competencies and general competencies are interdependent and serve to reinforce each other to provide safe, effective, patient- and family-centered, equitable, timely, and efficient care. To comprehensively achieve the desired education outcomes for health professionals, the minimum core competencies, or abilities, should reflect competence across all aspects of the framework.

Performance Domain: Core Knowledge

The core knowledge domain describes the foundational concepts of pain and unhealthy substance use and the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors needed to effectively apply this knowledge. General competencies and sub-competencies focus on foundational clinical knowledge of pain and SUD; relevant aspects of mental health and related intersections; clinical guidelines and treatment options; baseline skills for recognizing and assessing signs of pain, SUD, risky substance use; and ability to translate evidence and data into practice. Competencies and associated sub-competencies include the following:

General Competency 1: Foundational Knowledge

Sub-competencies:

Acquire knowledge of pain, unhealthy substance use, including SUD, their intersections, discrete concepts, and comorbidities (common comorbidities could include but are not limited to depression, anxiety, PTSD, and insomnia).

Acquire knowledge of emotional, mental, and behavioral health and their intersections with pain and unhealthy substance use.

Recognize the range of and differences among conditions relating to SUD and pain.

Acquire knowledge of stigma, mistrust, and fear related to pain and unhealthy substance use (refers to stigma experienced by patients and understanding the role of self-stigma, societal stigma, and clinician stigma).

Acquire knowledge of clinical practice guidelines, evidence-based resources, expert guidance, and understand the difference in evidence between these resources.

Acquire knowledge of treatment options for pain and prevention of SUD.

Acquire knowledge of treatment options for SUD.

General Competency 2: Applied Knowledge

Sub-competencies:

Develop and apply baseline skills for recognizing and assessing signs of pain, risky substance use, and SUD.

Develop and apply baseline skills for determining risks associated with mismanaged or undermanaged pain and SUD.

Develop the ability to translate evidence, expert recommendations, and data into practice.

Develop and apply baseline skills to develop realistic individualized treatment goals.

Develop and apply baseline skills to monitor patients for benefits (e.g., function, quality of life) and harms (e.g., adverse effects, substance misuse).

Develop and apply baseline skills to effectively counsel patients toward more healthy behaviors.

Develop and apply baseline skills to modify treatment based on clinical outcomes.

Understand the relationship between stigma and biases, as they pertain to disparities and inequities in pain and unhealthy substance use care (disparities refer to treatment, prevention, and recovery outcomes; inequities refer to care access and delivery).

Performance Domain: Collaboration

The collaboration domain describes the core principles of patient- and family-centered practices and team-based care. The competency domains and sub-domains focus on knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors needed to successfully collaborate with patients, families, and interprofessional teams, including respect and appreciation for individual- and family-level needs and autonomy; knowledge of individual roles and responsibilities within care teams; and ability to provide appropriate referrals for pain and SUD. Competencies and associated sub-competencies include the following:

General Competency 3: Patient- and Family-Centered Practices

Sub-competencies:

Respect and appreciate individual- and family-level needs and autonomy.

Recognize and eliminate stigma experienced by patients and families (refers to stigma experienced by patients and understanding the role of self-stigma, societal stigma, and clinician stigma).

Encourage patient and family discussions and expectations for functional care goals.

Demonstrate attitudes and behaviors reflecting cultural competency and centering on health equity.

Practice effective and evidence-based communication strategies with patients and families, including the use of non-biased, nonjudgmental, non-stigmatizing, nondiscriminatory language without use of microaggressions.

Use person-centered, collaborative approaches and decision making, using techniques such as motivational interviewing, conflict resolution, and redirection to address anchoring (refers to anchoring on initial information, which may prevent receptivity of subsequent information) (Riva et al., 2011; Searight, 2009).

Develop awareness of trauma-informed care practices and implementation skills for these practices when needed (refers to a care approach that acknowledges the patient’s past and present life situation and the widespread impact of trauma; recognizes signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff; and understands the diverse pathways to recovery) (Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center, 2021; SAMHSA, 2014).

Select and prepare individuals with lived experience to share their experiences and perspectives in educational sessions for clinicians, staff, students, trainees, and faculty.

General Competency 4: Team-Based Care

Sub-competencies:

Acquire knowledge of individual roles and responsibilities within the care team.

Develop the ability to work effectively and collaborate within and across different professions and settings.

Recognize and eliminate stigma against care teams.

Practice effective and evidence-based communication strategies with team members.

Recognize patients, families, caregivers, and communities as members of the interdisciplinary team.

Provide appropriate referral and follow-up for pain and SUD.

Performance Domain: Clinical Practice

The clinical practice domain describes the baseline awareness needed to understand health systems, health environments, and professionalism. The competency domains and sub-domains focus on the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors that facilitate successful integration with practice, such as the ability to recognize social determinants of health and political determinants of health, awareness of current regulations and policies and their relationship to practice, and commitment to lifelong learning and professional development in pain and SUD care. Competencies and sub-competencies include the following:

General Competency 5: Health Systems and Environment

Sub-competencies:

Recognize the social determinants of health, high-risk populations, and structural barriers that may be affecting pain and SUD care.

Acquire knowledge about clinician-level stigma and impact (refers to stigma experienced by practicing and emerging health professionals in pain/addiction care and underserved areas, and understanding the role of self-stigma, societal stigma, and provider stigma) (HHS, 2019; Scutti, 2019; Blevins et al., 2018; Ostrow et al., 2014).

Recognize and appreciate the role of health care professionals and the responsibility of providing complex care.

Understand health systems and strategies for navigating practice setting challenges by learning from colleagues.

Develop awareness and appropriate use of current data, evidence, guidelines, tools, and resources.

Develop awareness of current regulations and policies (at local, state, and federal levels) and their relationship to practice.

Develop an understanding of harm reduction and prevention strategies at individual and population levels (refers to a strategy or behavior that helps reduce harm or risk from substance use or undermanaged/mismanaged pain. For the purpose of this work, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (n.d.) definition of harm reduction is adapted to pain as well as substance use).

General Competency 6: Professionalism

Sub-competencies:

Acquire knowledge and use of ethical practices and mediation strategies.

Exercise self-care skills.

Engage in interprofessional continuing education that supports lifelong learning and professional development related to pain and unhealthy substance use care and addresses attitudes and behaviors related to treatment.

Continually assess and address one’s own implicit attitudes and biases (AHRQ, 2015; Sartorius, 2002).

Exercise resourcefulness and adaptability across practice settings.

Demonstrate compassion, empathy, and support throughout all stages of care (including treatment and recovery), and exercise the ability to “meet patients where they are.”

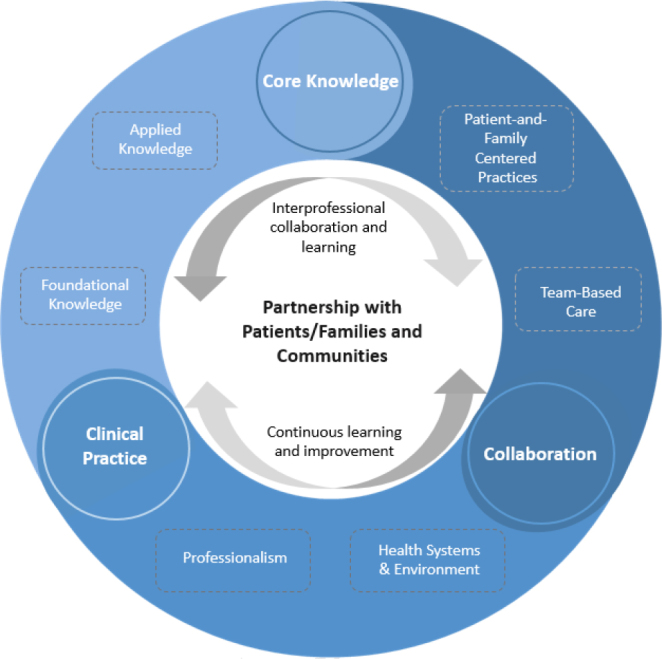

A complete visual of the core competency framework (see Figure 2) follows.

FIGURE 2. The 3Cs Framework.

SOURCE: Holmboe, E., S. Singer, K. Chappell, K. Assadi, A. Salman, and the Education and Training Working Group of the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. 2022. The 3Cs Framework for Pain and Unhealthy Substance Use: Minimum Core Competencies for Interprofessional Education and Practice. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202206a.

NOTE: Figure 1 summarizes each major step in the development process for the Core Competency Domains Framework.

Figure 2 displays a snapshot of how the framework’s three broad performance domains (the “Cs”) relate to the six competency domains and how all of the domains are interrelated and connect to one another. Figure 2 also demonstrates how the framework integrates the two facilitating factors (interprofessional collaboration and learning; and continuous learning and improvement) and is collectively centered around a focus on partnering with patients, families, and communities.

Conclusion

The 3Cs Framework was created to address PPGs across pain and SUD, catalyze system-level change in the health care environment, and improve health outcomes at the individual and population levels. Although various accredited educational institutions, committees, and task forces have developed their own comprehensive frameworks with similar objectives, the existing curricula are either limited in scope (only focusing on pain or SUD care) or limited in applicability and audience (only intended for specific health fields or specialties or education or training level). Using a public health lens, this framework builds from previous works and integrates core concepts relevant to learners and educators of all health professional backgrounds and education and training levels. The competency domains and sub-domains describe a minimum level of ability and are intentionally broad and comprehensive in scope to enable a wide range of applicability and use.

The 3Cs Framework is intended to inform minimum core competencies and describe baseline knowledge, skills, behaviors, performance, and attitudinal expectations across health professions. The framework would benefit from broad dissemination to education systems and stakeholders to facilitate far-reaching and collaborative implementation. This framework is not intended to detract from existing or emerging evidence-based, interprofessional competencies for pain management and SUDs but rather to ensure flexibility (Fishman et al., 2013).

The framework’s usability and impact rely on support from stakeholders representing clinical, educational, regulatory, and financial systems across health care. A coordinated effort is needed across health professions to incorporate the 3Cs Framework into existing curricula. This should be supported by effective teaching and learning approaches and assessed by accreditation and licensing bodies. Specialty societies, associations, and other accredited continuing education providers can develop training content to address the needs of certain professions and special populations. In addition, competencies developed from the framework will need to be reinforced through accreditation assessments. Certifying and licensing examination criteria across states should reflect concepts included in the framework. Quality metrics can be updated and mapped to support implementation of the framework. Additionally, health systems and reimbursement structures should incentivize clinical practices that build on the core principles ingrained in the framework, particularly interprofessional collaboration and patient- and family-centered approaches to care.

To support uptake, the framework should be accompanied by a suite of implementation tools, including implementation science principles, implementation guidance for different stakeholder groups, and clinical resources mapped to the framework’s sub-competencies. While these resources may not be exhaustive, they may help accelerate the framework and the development of additional tools, resources, and educational materials needed to facilitate implementation of core competencies across professions, settings, and contexts. Tracking and evaluation will be critical to assess implementation efforts. Specifically, continuing education accreditors, regulators, and educational leaders across the health care continuum should collaborate to enable national tracking of core competencies for pain management and unhealthy substance use care. Tracking continuing education activities that are designed to address specific competencies paired with evaluation of learning outcomes will help education providers and health professionals to collaborate around targeting setting- and patient population-specific PPGs and underlying educational needs. This tracking should be supported by evaluation frameworks, which will further center accountability for adaptive interprofessional continuing education and care delivery across the health care professional workforce (Chappell et al., 2021).

The 3Cs framework can help shape a health care environment that values an improved state of care for pain and unhealthy substance use by fostering interprofessional coordination and collaboration and supporting continuous improvement and learning, across prevention and care. Health care processes focused on partnership and co-production are integral to sustain effective and comprehensive patient-centered care. In addition to transforming structures and processes, successful implementation of the 3Cs Framework will catalyze adaptive, interprofessional practice that will better prepare health care professionals with the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to proactively address the complex needs of patients and families with pain and unhealthy substance use and close persistent PPGs.

APPENDIX A

Summary Matrix of Environmental Scan Results

| Source | Overview and Objectives | Core Competencies | Overlapping Themes and Key Takeaways | Professional Practice Gaps Mapping Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) - Standards of Care for Addiction Specialists (2014) https://www.asam.org/docs/defaultsource/practice-support/quality-improvement/asam-standards-of-care.pdf?sfvrsn=10 |

Intended for any physician/practitioner assuming the responsibility for caring for addiction and related disorders. Standards aim to “raise the bar” of expectations and account-abilities by describing what is expected of physicians during different points in the addiction care process. |

Standards:

|

Overlapping Themes: diagnostic criteria, medical interventions, biopsychosocial interventions, treatment alternatives and advantages/disadvantages, physical exam, patient history, coordinating team-based care, specialist referrals, safety and risk evaluations, patient-involved clinical decision making Key Takeaways: collecting medical/social history/family history, sharing information and protecting privacy, documentation |

|

| ASAM - Competencies of Addiction Medicine Recognition Program (2015) https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/education-docs/asam-fundamentals-recognition-program-learning-objectives-and-competencies-final-10-1-15.pdf?sfvrsn=2 |

Intended for health care professionals treating addiction and SUD. ASAM Fundamentals Curriculum Planning Committee identified nine competencies in addiction medicine for the purpose of continuing education. Learners are expected to display professionalism in all activities and interactions with patients and professional colleagues, demonstrate commitment to the health/well-being of individuals and society through ethical practice, profession-led regulation, and high personal standards of behavior. |

Nine core competencies and fundamentals:

|

Overlapping Themes: core medical knowledge on substances, SUD, and commonly associated medical/mental disorders, screening, interviewing, biopsychosocial approach, respectful/nonjudgmental/non-stigmatizing communication with patients, recognize SUD as chronic medical illness, ability to access resources, team-based care, referral to specialty care and formal/informal treatment programs, MI skills, medication-assisted treatment (MAT), community support Key Takeaways: establishing healthy personal boundaries with patients/families, gender/cultural awareness, patient confidentiality, nondiscriminatory communication, recognizing health literacy, barriers to access and factors impacting therapeutic responses |

|

| American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM) - Core Competencies for Addiction Medicine (2012) https://acaam.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/Core-Competencies-for-Addiction-Medicine.pdf |

Intended for medical residents and fellows specializing in addiction medicine. Competency goals are focused on prevention and treatment of addiction and substance-related health conditions for a diverse spectrum of drugs. |

Core competencies:

|

Overlapping Themes: recognizing common issues and medical conditions related to SUD, psych/social/functional indicators of subclinical addiction disorders, interpreting lab findings/diagnostic tests, physical exams, nonjudgmental communication, use of standardized screening instruments, MI strategies, diagnostic tests, specialist referrals Key Takeaways: medical emergencies, psychiatric emergencies, special contexts, continuous improvement, and professional development |

|

| Dental Education Core Competencies - Massachusetts Dental Schools (2016) https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/08/31/governors-dental-education-working-group-on-prescription-drug-misuse-core-competencies.pdf |

Intended for Massachusetts (MA) dental students (cross-institutional). Working group acknowledges the need to integrate behavioral health in dentistry and the dental field lacks a specialty for orofacial pain. Core curriculum aims to provide dental students with a foundation in prevention, management, and identification of SUD and familiarity with chronic pain. Competencies focus on reducing opioid prescribing, counseling, appropriate referral, and interprofessional collaboration. |

Core competencies are organized into three domains based on prevention level (non-exclusive). Domains (by prevention level):

|

Overlapping Themes: diagnosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options for pain and SUD, risks and benefits, proper use of available screening instruments and protocols, screening/evaluation, communication with patient/family, provide referrals to addiction specialists and treatment programs, engage in interprofessional care teams Key Takeaways: evidence-based foundational skills in patient-centered counseling and behavior changes in context of patient encounter |

|

| Medical Education Core Competencies - Massachusetts Medical Schools (2015) https://www.mass.gov/doc/medical-education-core-competencies-for-the-prevention-and-management-of-prescription-drug-1/download |

Intended for MA medical students (cross-institutional). Competencies set clear baseline standards for prevention skills and knowledge in the areas of screening, evaluation, treatment planning, and supportive recovery. Implementation aims to support future physicians over the course of medical education w/skills and foundational knowledge in the prevention of prescription drug misuse. |

Domains (by prevention level):

|

Overlapping Themes: diagnostic criteria for pain and SUD, recognize risk factors of SUD and overdose, awareness of social determinants, treatment options, risks and benefits, incorporate relevant data into treatment planning, MI Key Takeaways: apply chronic disease model, recognizing own/societal stigmatization and bias affecting SUD and treatment outcomes |

|

| Core Competencies for Pain Management and SUD - University of California Medical Schools (2020) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8921611/ |

Intended for California (CA) medical students (cross-institutional). Working group (six CA med schools) includes diverse specialty and disciplinary representation for subjects related to pain and SUD. Competencies are included in the UC Clinical Performance Examination (CPX) administered to 4th-year medical students. Competencies aim to educate CA medical students on safe and effective pain management, safe opioid prescribing, and identification and treatment of SUD. |

Competencies are organized into three sections: two sections (pain and SUD) have four domains, one section (public health) has one domain. Pain and SUD domains:

Public health:

|

Overlapping Themes: biological/social/environmental influences on pain and SUD, diagnostic differentials, harm reduction, secondary prevention, recognizing the role of societal biases/stigma in pain and SUD outcomes, appropriate referrals, use of assessment tools, communication skills, integrated/multidisciplinary care Key Takeaways: ability to differentiate substance use terminology, ability to recognize patient preferences |

|

| Statewide Curriculum for Pain and Addiction - Arizona Health Professional Programs (2018) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7649998/ |

Intended for students of all health professional programs. Working group comprised representatives from all 18 medical, osteopathic, physician assistant (PA), nurse practitioner (NP), dental, podiatry, and naturopathic programs in Arizona (AZ). Proficiency level is assessed by a rubric. Curriculum aims to redefine pain and addiction as multidimensional public health issue; competencies were designed to be relevant to all provider types. |

Competencies are structured around 10 core components, each supported by evidence-based objectives. Core components:

|

Overlapping Themes: current approaches, biological/social/environmental factors contributing to pain/addiction, treatment plans and prevention strategies, model destigmatizing language, ability to utilize a patient-centered, team-based care approach Key Takeaways: acknowledge industry influence on opioid use disorder (OUD)/pain care |

|

| Interprofessional Consensus: Pain Management Core Competencies for Pre-licensure Clinical Education (2012) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3752937/ |

Intended for all health professionals undergoing pre-licensure education programs in pain management. Core competencies and supporting values were developed by an interprofessional expert group; contributing members represented medicine, dentistry, nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy, psychology, social work, acupuncture, and veterinary medicine. Domains align with outline categories of International Association for the Study of Pain curricula. Core competencies in pain management were developed as a basis for delivering comprehensive and high-quality pain care. |

Core competencies for pain management categorized within four domains:

Core values integral and embedded within all domains and competencies: Advocacy Collaboration Communication Compassion Comprehensive care Cultural inclusiveness Empathy Ethical treatment Evidence-based practice Health disparities reduction Interprofessional teamwork Patient-centered care |

Overlapping Themes: recognizes pain as complex/multidimensional, present pain theories, terminology for pain and associated conditions, proper use of screening/assessment tools, factors impacting assessment/treatment, effective communication, patient education, evidence-based treatment options, benefits/risks of available options, special populations, patient-centered care plan Key Takeaways: social/environmental impact on pain management, impact of pain on society, shared decision making, differentiate substance use and pain terminology, self-management strategies, assessment/management across settings, interprofessional contributions |

|

| Statewide Medical School Curriculum – Pennsylvania Physician General Task Force (2017) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28339890/ |

Intended for all Pennsylvania (PA) medical students (cross-institutional). Task force conducted a literature review and survey of graduating medical students to then develop, review, and approve core competencies for education on opioids and addiction. Competencies aim to improve student knowledge and attitudes in these subject areas to thus improve patient outcomes. PA legislation passed in 2016 requires state boards for health professions create safe opioid prescribing curriculum. |

Core competencies (nine domains):

|

Overlapping Themes: diagnostic criteria and differentials, SUD treatment and interfering factors, common co-occurring medical conditions/health issues with pain/SUD, conducting patient-focused history, physical exams, screening, specialist referrals, nonjudgmental communication Key Takeaways: describing the importance of pain assessment and referral process with patient, “warm handoff” referral process, patient education |

|

| American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) - Strategies for Opioid Prescribing (2018) https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article-abstract/76/3/187/5301698#no-access-message |

Intended for pharmacists in hospitals, health systems, and ambulatory care clinics. Commission members were selected from pharmacy, medicine, nursing, public health, health care associations, regulatory agencies, and academia. Strategies aim to optimize prescribing and monitoring of opioids while minimizing the risks of addiction and preventable harm associated with over-utilization of opioids. |

Five domains:

|

Overlapping Themes: knowledge of evidence-based, non-opioid and non-pharmacologic therapies, identifying and adopting available tools and resources for pain management, coordinating multidisciplinary care, community engagement, treating special populations, minimizing risks, proper use of data and technology (EHR and telehealth) Key Takeaways: community engagement, treating special populations |

|

| American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) - Pharmacy Education on SUD (2020) https://www.ajpe.org/content/ajpe/84/11/8421.full.pdf |

Intended for pharmacy students; applies to practicing pharmacists and pharmacy techs. Guidelines comprise six educational outcomes (competencies) mapped into four content groups (domains); each domain focuses on a core topic on substance use pharmacy education. Competencies aim to endorse continuing professional development for currently practicing pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to manage SUD. |

Four content areas/domains:

Six educational outcomes/competencies:

|

Overlapping Themes: interdisciplinary evidence-based practice, specialist referrals, interprofessional collaboration, identify individuals at-risk for SUD, patient education, use of non-stigmatizing language and communication, community engagement, ongoing professional development Key Takeaways: policies and regulations related to treatment access, harm reduction approach, patient-centered goals, environmental influences, payment models, roles and responsibilities of different government agencies/organizations |

|

| American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) - Recommendations for Chronic Pain Management in Adult Cancer Survivors (2016) https://asco-pubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206 |

Intended for all health care practitioners providing care to cancer survivors. Target population: any adult diagnosed with cancer and experiencing pain lasting over three months, irrespective of cause. Prevalence—40% of cancer survivors report chronic pain. Competencies aim to provide evidence-based guidance on the optimum management of chronic pain in adult cancer survivors. |

Key Recommendations:

Guidelines advise clinicians to consider prescribing a trial of opioids in carefully selected cancer survivors with chronic pain who do not respond to more conservative management. |

Overlapping Themes: patient screening, conducting a comprehensive and multidimensional pain assessment, physical exam, knowledge of multi-modal care plans, non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic (opioid/non-opioid) treatment options, diagnostic testing, individual risk factors, ability to engage patient/family throughout pain assessment and management, educate patients and families on benefits/risks of treatment, proper tapering and discontinuation of opioids, specialist referral Key Takeaways: past pain treatments, roles and responsibilities within care team, address myths/misconceptions about medication use, ability to recognize patient’s literacy level and determine need for interpreters, laws/regulations for prescribing controlled substances, culturally-aware communication |

|

| American Psychological Association (APA) - Core Competencies for Emerging Specialty of Pain Psychology (2018) https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-37353-001 |

Intended for practicing and emerging pain psychologists. Competencies were developed based on interdisciplinary foundational principals published by Fishman et al. Competencies were created to address the gap in psychology and pain care and establish a curriculum for the emerging specialty of pain psychology. Competencies define what is expected of a practicing pain psychologist; learners are expected to have at least foundational competencies in identified domain rather than expertise. |

Domains:

|

Overlapping Themes: recognizing pain as complex and multidimensional, knowledge of substance abuse, biopsychosocial model, individual/systemic factors affecting pain, social determinants of health, common medical/mental health issues associated with pain, ability to educate and communicate patient/family, evidence-based pain and risk assessments, MI skills, proper use of screening tools/resources, patient-centered approach, interprofessional care approach, pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatments and risks/benefits, recognition of stereotyping/bias affecting care, technology-based interventions (telehealth) Key Takeaways: relevant and evolving pain theories, pain paradigms, behavioral health intersections with pain, mindfulness/coping skills training, pre/post-surgical evaluations, patient expectations and goals |

|

| University of California (UC) Davis Primary Care Pain Management Fellowship Program (2017) https://journals.lww.com/academic-medicine/Full-text/2021/02000/UC_Davis_Train_the_Trainer_Pri-mary_Care_Pain.41.aspx |

Intended for primary care fellows (licensed physicians, pharmacists, NPs, PAs). Curriculum incorporates competency and hybrid-based educational models of in-person/distance-based learning and direct faculty-fellow mentoring to train PCPs in pain care and prepare them to train others. Multidisciplinary mentoring team comprises health professionals from a variety of specialties to reflect the biopsychosocial nature of pain and management and need for interdisciplinary and interprofessional care. Competencies aim to directly address the education gap among post-licensure providers and provide high-quality training to manage pain and SUDs. |

Four domains:

Competencies in each domain emphasizes:

|

Overlapping Themes: knowledge of biopsychosocial approach, recognizes pain as complex and multidimensional, individual factors impacting pain assessment and management, unique needs for special populations, current pain theories, opioid risk assessment, interprofessional care, diagnostic criteria for pain disorders and SUD, factors interfering with pain assessment/management, terminology for pain/SUD and commonly associated conditions, benefits and risks of treatment options, ability to provide patient-centered care Key Takeaways: differentiation between different types of pain, teach-back method, ability to adjust plan of care as needed, roles and responsibilities within care team |

|

| U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Opioid Analgesic Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) - Education Blueprint for Health Care Professionals (HCPs) (2018) https://www.fda.gov/media/99496/download |

Intended for prescribers, pharmacists, and nurses but relevant for all HCPs who participate in the treatment and monitoring of pain. FDA released updated REMS on opioid prescribing to include all opioid analgesics (immediaterelease, extended-release, longacting) in the outpatient setting. REMS on opioid prescribing focuses on acute and chronic pain management; blueprint was created to provide HCPs with a contextual framework for safe and effective opioid prescribing. FDA posted education blueprint for continuing education (CE) providers to use as they develop CE materials and activities. |

Section 1: Basics of pain management I. The need for comprehensive pain education II. Definitions and mechanisms of pain III. Assessing patients in pain Section 2: Creating the pain treatment plan I. Components of an effective treatment plan II. General principals of non-pharmacologic approaches III. General principals of pharmacologic analgesic therapy a. Non-opioid medications b. Opioid analgesics IV. Managing patients on opioid analgesics a. Initiating treatment with opioids—acute pain b. Initiating treatment with opioids—chronic pain c. Ongoing management of patients on opioid analgesics d. Long-term management e. How to recognize/intervene upon suspicion/identification of OUD f. When to consult with a pain specialist g. Medically directed opioid tapering h. Importance of patient education V. Addition medicine primer |

Overlapping Themes: fundamental concepts of pain and addiction, identify risk factors for OUD, identify/manage patients with OUD, pain assessments, physical exam, pharmacologic (opioid/non-opioid) and non-pharmacologic treatment options, patient-centered approach, counseling patients/families on safe opioid use, specialist referrals, evidence-based tools and scales (prescription drug monitoring program [PDMP]), psych/social evaluation, diagnostic studies, interprofessional care, roles and responsibilities within care team, special populations, destigmatizing language Key Takeaways: initiating/titrating/discontinuing opioids, counseling patients/families harm reduction and safety strategies, state/federal regulations, medical specialty guidelines on pain/opioid prescribing, proper documentation, family planning (initial assessment), discussing patient goals and expectations |

|

| Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) - Guidelines for Teaching Proper Prescribing of Controlled Prescription Drugs (CPD) (2020) https://medsites.vumc.org/cph/home |

Intended for clinical teachers of VUMC; specifically instructors for student prescribers (physicians, dentists, advanced NP, PA). Authors acknowledge misprescribing is the leading cause of CPD abuse and produces a range of serious consequences for patients, prescribers, and the community. Many physicians are unaware of prescribing guidelines and how their prescribing impacts the CPD epidemic. 40% receive training on prescription drug abuse/addiction, 55% routinely recommend appropriate treatment for patients who abuse prescription drugs. Guidelines were created to address the gap in pre-licensing education and safe prescribing practices, to educate physicians on prescribing guidelines and how misprescribing impacts the CPD epidemic, to prepare physicians to identify and manage drug-seeking patients, and to reduce the consequences of misprescribing. |

Core teaching tips and objectives:

|

Overlapping Themes: screening for substance misuse/abuse, MI skills, identify SUD, CPD misuse, knowledge and proper use of available clinical tools/resources, PDMP, assessment, treatment options for pain, interprofessional care, counseling patients on SUD, SUD resources for patients, risk factors for SUD and overdose, follow new state prescribing laws, effective communication Key Takeaways: consequences of misprescribing, informed consent, special populations, conflict management |

|

| Tennessee (TN) Department of Health - Guidelines for Chronic Pain (2019) https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/healthprofboards/painmanagement-clinic/ChronicPainGuidelines.pdf |

Intended for clinicians and health professionals treating outpatient chronic pain. TN Governor’s Commission on Pain and Addiction Medicine education comprises representatives from TN’s medical educational institutions. Guidelines aim to help providers reduce problems associated with prescription opioids while maintaining access to compassionate care and appropriate medications for chronic pain patients. Competencies set the minimum expectations for educating and training health professionals on pain management, SUD, and opioid prescribing. Long-term goals of appropriate pain management are to improve symptoms, functionality, and overall quality of life while minimizing adverse effects, addiction, overdose deaths, and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). |

Guidelines helped develop the 12 core competencies for current and future curricula and are organized into three sections: I. Prior to initiating opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain II. Initiating opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain III. Ongoing opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain 12 core competencies:

|

Overlapping Themes: core knowledge of pain, screening/assessment/evaluation of pain, recognizing signs of SUD, communication strategies Key Takeaways: conflict resolution, patient expectations and goals, how do opioids/benzodiazepines work, patient education, informed consent |

|

| Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA) - Prevention Core Competencies https://pttcnetwork.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/PEP20-03-08-001.pdf |

Intended for current and rising professionals in mental health and substance use disorder prevention fields. Competencies aim to provide professional direction in the preventative field and offer guidance for training programs and service delivery qualification. To accept new professional standards as an integral part of job descriptions, staff qualifications, and development of transferable skills. KSAs (knowledge, skills, and abilities) are separated into two categories: Technical and Behavioral. Technical KSA measures acquired knowledge and “hard” technical skills and enables the evaluation of these elements. Behavioral KSA measures “soft” skills and includes the attitudes and approaches applicants take into work. Factors are more related to human characteristics and skills, such as attitude, work approach, and collaborative abilities. |

Three-phase work plan:

Cross-cutting competencies:

Interdisciplinary foundations:

Prevention interventions for SUD/MEB:

|

Overlapping Themes: core knowledge of SUD, communication strategies, navigating health care systems, intersections with mental/behavioral health, family-centered care, eliminating stigma Key Takeaways: ethical practices, professional responsibilities and development, understanding the impact of SUD on individuals, interpersonal relationships, and communities |

|

| SAMHSA - Addiction Counseling Competencies in Professional Practice (2005) https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma12-4171.pdf |

Intended for all practitioners dealing with SUD and emphasized for professional substance abuse treatment counselors. Competencies (updated from 2000) have been applied to curriculum/course evaluation and design for higher education, designing professional development and continued education programs, certification standards/exams across the United States and internationally. Updated with feedback-based improvements of 2000 revised version and adds relevant literature published literature, several practice dimensions (particularly those addressing clinical evaluation and treatment planning) were rewritten to reflect current best practices. KSAs define the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for competency. |

Section 1. Transdisciplinary foundations (KSAs needed by all disciplines) categorized by four discrete building blocks:

Section 2. Professional practice dimensions (KSAs needed for addiction counselors) categorized by eight competencies

|

Overlapping Themes: core knowledge of addiction, treatment options for addiction, recognizing contextual variables, symptoms of SUD and common co-occurring medical and mental health conditions, openness to information that may differ from personal views/attitudes Key Takeaways: basic concepts of social, political, economic, and cultural systems and their impact, appreciating differences between and within cultures, willingness to work with people who display and/or have mental health conditions |

|

| Association for Multidisciplinary Education and Research in Substance Use and Addiction (AMERSA) - Specific Disciplines Addressing Substance Use (2018) https://amersa.org/wp-content/uploads/AMERSA-Competencies-Final-31119.pdf |

Intended for physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and physician assistants working in SUD treatment and prevention programs; applicable to most educational/professional levels. Revision to 2002 strategic plan for interdisciplinary faculty development, provides updated evidence-based guidance to support health professionals in effectively assessing/treatment patients using alcohol and other drugs. Provides HCPs with an overview of scientific literature, review of discipline-specific perspectives on SUD training, and summary of core KSAs needed in all health professional disciplines to effectively identify, intervene with, and refer patients with SUD. Competencies aim to provide a practical interprofessional guide for HCPs working with diverse populations across health care settings (community health centers [CHCs], federally qualified health centers [FQHCs], primary care practitioner [PCP] offices) with a focus on prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery supports for persons affected by substance use. Competencies aim to help HCPs engage and patients in change-oriented, bi-directional conversation, help patients understand risks associated with using alcohol and drugs, provide evidence-based treatment, and encourage patients to accept referral to holistic, coordinated care for their substance use, mental health, and/or medical problems. |

SUD core competencies (shared by two or more disciplines):

Comprehensive list of SUD core competencies per discipline appear at the conclusion of each discipline-specific chapter. Four essential elements for care team:

|

Overlapping Themes: screening tools, risk assessment, MI skills, specialist referral, evidence-based pharmacological treatment options, specialist referral, recognize/reduce stigma associated with SUD, community support, recognizing SUD as a chronic medical disease, commonly associated medical/mental health issues, special populations, barriers to treatment, team-based care Key Takeaways: behavioral interventions, patient confidentiality and rights, special populations, legal/ethical issues impacting care, strategies to address/prevent own negative biases |

|

| National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare (NCSACW) - Technical Assistance (TA) Tool/Guide for Professionals Referring to SUD Treatment (2018) https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/files/understandingtreatment-508.pdf |

Intended for professionals referring patients to SUD treatment. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) found that caseworkers, courts, and other providers misunderstand how SUD treatment works and lacks guidelines on how to incorporate service into child welfare practices. Tool includes a list of questions child welfare/court staff can ask treatment providers to ensure that effective linkages are made. TA tool was designed to provide professionals who refer parents to SUD treatment with fundamental understanding of SUD and treatment, so professionals can make informed referral decisions for services that meet the parent and family’s needs. The ultimate goal of SUD treatment is recovery. SAMHSA created working definition of recovery that incorporates four major principals: health, home, purpose, and community. |

The treatment process:

Comprehensive assessment dimensions (to assess appropriate level of care):

|

Overlapping Themes: evidence-based treatments and screening tools, identifying potential misuse/SUD, past/current treatment history, medical history, “whole-patient/patient-centered” approach, knowledge of stigma around MAT, barriers to recovery, community support, interprofessional collaboration, and culturally appropriate services Key Takeaways: MAT, family-centered care, conflict resolution with families, gender-appropriate services |

|

| International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) - Pain Curriculum for Social Workers (2018) https://www.iasp-pain.org/education/curricula/iasp-curriculum-outline-for-pain-in-social-work/ |

Intended for social workers (entry-level, pre-licensure). Fundamental concepts focus on complexity of pain, how pain is observed and assessed, collaborative approaches to treatment options, and applying competencies across the lifespan in the context of various settings, populations, and care-team models. Curriculum aims to help social workers develop pain-specific knowledge to better assess and advocate for appropriate care, employ evidence-informed interventions that contribute to the team management of pain and related suffering, and to identify the need for referrals from pain specialists. |

Curriculum:

|

Overlapping Themes: core knowledge of pain, screening and assessment, treatment options, team-based care, high-risk populations, the role of stigma and eliminating stigma, specialist referrals Key Takeaways: pain management in the context of social work, ethically challenging situations, barriers to accessing treatment, special populations |

|

| Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS) - Content Outline for Board Certified Psychiatric Pharmacist (BCPP) Credential (2017) https://www.bpsweb.org/wp-content/uploads/PSYContentOutline2017.pdf |

Intended for students specializing in psychiatric pharmacy (pre-certification). Certification exam is organized by domain/sub-domain (major responsibility or duty), task (activity that elaborates on domain/sub-domain), and knowledge statement (essential to competent task performance). Knowledge statements clarify the expectations for newly certified pharmacists and providing comprehensive medication management (CMM) to persons with psychiatric and related disorders. |

Domains:

|

Overlapping Themes: MI skills/principals, social/cultural factors affecting outcomes, therapeutic alliance, proper use of screening and scaling tools/resources, physical exam, individualized treatment and monitoring, shared decision making, pharmacologic/non-pharmacologic therapies, special populations, transitioning care Key Takeaways: managing conflict, cost-effectiveness of treatments (pharmacoeconomic studies), models of care (mobile, telehealth, peer support), patient education, health literacy, regulatory and ethical issues related to researching patients, applying and generalizing research findings |

|

| American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) - Patient Care Process for Delivering Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM) (2018) https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/CMM_Care_Process.pdf |

Intended for patients, clinical pharmacists, primary and health care providers, payers, students, and educators. Research-based framework was developed to address the misuse, underuse, and overuse of medications as an opportunity to meet cost/quality benchmarks and improve patient care. Authors used common language so patients, clinicians, payers, students, and educators could utilize this resource. Key strategies for CMM aim to optimize medication use in patient-centered, team-based care settings (outpatient and ambulatory care) for patients with multiple chronic conditions. |

Essential functions:

|

Overlapping Themes: patient-centered care, comprehensive review of patient history, social history, concurrent substance use, team-based care, factors influencing treatment access and medication adherence, proper use of data and technological tools/resources, discuss patient treatment goals, physical exam, identify monitoring parameters, understanding scope and responsibilities of care team members, interprofessional communication. Key Takeaways: translating evidence into practice |

|

APPENDIX B

Summary Matrix of Environmental Scan Results

| Summary: Key Themes Included across Curriculum and Framework Examples |

|---|

|

| Summary: Common Gaps across Existing Framework Examples |

|

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: Eric Holmboe discloses receiving royalties for a textbook from Elsevier Publishing.

Contributor Information

Eric Holmboe, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Steve Singer, Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.

Kathy Chappell, American Nurses Credentialing Center.

Kimia Assadi, Naional Academy of Medicine.

Aisha Salman, National Academy of Medicine and the Health Professional Education and Training Working Group of the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) TeamSTEPPS 2.0. [March 11, 2022]. n.d. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/instructor/fundamentals/module1/m1evidence-base.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.AHRQ. AHRQ’s Core Competencies. 2019. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.ahrq.gov/cpi/corecompetencies/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 3.AHRQ. TeamSTEPPS®: Research/Evidence Base. 2015. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/evidence-base/inter-pro-education.html . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker DP, Gustafson S, Beaubien JM, Salas E, Barach P. Medical Teamwork and Patient Safety: The Evidence-Based Relation. 2003. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233969549_Medical_Teamwork_and_Patient_Safety_The_Evidence-Based_Relation . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechtel C, Ness DL. If You Build It, Will They Come? Designing Truly Patient-Centered Health Care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):914–920. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blevins CE, Rawat N, Stein M. Gaps in the Substance Use Disorder Treatment Referral Process: Provider Perceptions. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12(4):273–277. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd H, McKernon S, Mullin B, Old A. Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2012;125(1357):76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon-Bowers JA, Tannenbaum SI, Salas E, Volpe CE. Team effectiveness and decision making in organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995. Defining team competencies and establishing team training requirements. edited by R. Guzzo, E. Salas, and Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) What is Harm Reduction? n.d.. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/effective-interventions/treat/steps-to-care/my-stc/cdc-hiv-stc-what-is-harm-reduction.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chappell K, Holmboe E, Poulin L, Singer S, Finkelman E, Salman A. Educating Together, Improving Together: Harmonizing Interprofessional Approaches to Address the Opioid Epidemic. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2021. NAM Special Publication. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dardess P, Dokken DL, Abraham MR, Johnson BH, Hoy L, Hoy S. Partnering with Patients and Families to Strengthen Approaches to the Opioid Epidemic. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. 2018. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/opioid-epidemic/IPFCC_Opioid_White_Paper.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dokken DL, Johnson BH, Markwell HJ. Family Presence During a Pandemic: Guidance for Decision-Making. 2021. [March 11, 2022]. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Available at: https://ipfcc.org/bestpractices/covid-19/IPFCC_Family_Presence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwyn G, Nelson E, Hager A, Price A. Coproduction: when users define quality. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2020;29(9):711–716. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishman SM, Young HM, Arwood EL, Chou R, Herr K, Murinson BB, Watt-Watson J, Carr DB, Gordon DB, Stevens BJ, Bakerjian D, Ballantyne JC, Courtenay M, Djukic M, Koebner IJ, Mongoven JM, Paice JA, Prasad R, Singh N, Sluka KA, St. Marie B, SA Strassels. Core competencies for pain management: results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Medicine. 2013;14(7):971–981. doi: 10.1111/pme.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. American Psychologist. 2014;69(2):119–130. doi: 10.1037/a0035514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Pain Management Best Practices. 2019. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pain-mgmt-best-practices-draft-final-report-05062019.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IOM. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IOM. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. 2016. [March 11, 2022]. https://hsc.unm.edu/ipe/resources/ipec-2016-core-competencies.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. 2011. [April 21, 2022]. https://www.aacom.org/docs/defaultsource/insideome/ccrpt05-10-11.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon SC, Tandon SD, Islam N, Riley L, Trinh-Shevrin C. Applying a community-based participatory research framework to patient and family engagement in the development of patient-centered outcomes research and practice. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2018;8(5):683–691. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore DE. Jr., JS Green, HA Gallis. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2009;29(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/chp.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. n.d.. [March 12, 2022]. https://nam.edu/programs/action-collaborative-on-countering-the-u-s-opioid-epidemic/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrow L, Manderscheid R, Mojtabai R. Stigma and Difficulty Accessing Medical Care in a Sample of Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Under-served. 2014;25(4):1956–1965. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riva P, Rusconi P, Montali L, Cherubini P. The Influence of Anchoring on Pain Judgement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42(4):265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.10.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitz R, Larson MJ, Labelle C, Richardson J, Samet JH. The case for chronic disease management for addiction. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2008;2(2):55–65. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318166af74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA. M. A. Quiñones and A. Ehrenstein. American Psychological Association. Training for a rapidly changing workplace: Applications of psychological research. 1997. Methods, tools, and strategies for team training. In. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sartorius N. Iatrogenic stigma of mental illness begins with behaviour and attitudes of medical professionals, especially psychiatrists. BMJ. 2002;324:1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7352.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scutti S. 21 million Americans suffer from addiction. Just 3,000 physicians are specially trained to treat them. 2019. [March 11, 2022]. Association of American Medical Colleges, December 18. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/21-million-americans-suffer-addiction-just-3000-physicians-are-specially-trained-treat-them. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Searight R. American Family Physician. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. 2009;79(4):277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Prevention Core Competencies. 2021. [March 11, 2022]. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Prevention-Core-Competencies/PEP20-03-08-001 . [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAMHSA. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [March 11, 2022]. https://cantasd.acf.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/SAMHSAConceptofTrauma.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. What is Trauma-Informed Care? 2021. [March 11, 2022]. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcock PM, Janes G, Chambers A. Health care improvement and continuing interprofessional education: continuing interprofessional development to improve patient outcomes. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2009;29(2):84–90. doi: 10.1002/chp.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]