Abstract

The umuDC genes are part of the Escherichia coli SOS response, and their expression is induced as a consequence of DNA damage. After induction, they help to promote cell survival via two temporally separate pathways. First, UmuD and UmuC together participate in a cell cycle checkpoint control; second, UmuD′2C enables translesion DNA replication over any remaining unrepaired or irreparable lesions in the DNA. Furthermore, elevated expression of the umuDC gene products leads to a cold-sensitive growth phenotype that correlates with a rapid inhibition of DNA synthesis. Here, using two mutant umuC alleles, one that encodes a UmuC derivative that lacks a detectable DNA polymerase activity (umuC104; D101N) and another that encodes a derivative that is unable to confer cold sensitivity but is proficient for SOS mutagenesis (umuC125; A39V), we show that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity can be genetically separated from the role of UmuD′2C in SOS mutagenesis. Our genetic and biochemical characterizations of UmuC derivatives bearing nested deletions of C-terminal sequences indicate that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is not due solely to the single-stranded DNA binding activity of UmuC. Taken together, our analyses suggest that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is conferred by an activity of the UmuD2C complex and not by the separate actions of the UmuD and UmuC proteins. Finally, we present evidence for structural differences between UmuD and UmuD′ in solution, consistent with the notion that these differences are important for the temporal regulation of the two separate physiological roles of the umuDC gene products.

In the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, DNA damage induces the SOS regulon (10). This regulon consists of approximately 30 unlinked genes (6, 10, 15) whose expression is coordinately regulated by the LexA repressor protein (21, 22). The primary role of these ∼30 gene products is to help E. coli to repair DNA damage efficiently (10, 47, 51). Consequently, many of these LexA-regulated genes encode proteins that function to repair DNA lesions in an accurate manner (10). However, in the event that a DNA lesion in E. coli cannot be repaired accurately, an error-prone repair pathway exists. This pathway, termed translesion DNA synthesis (TLS), is the mechanistic basis of SOS mutagenesis (41, 51). TLS in E. coli depends on the products of the recA and umuDC genes (10, 49). The umuDC genes encode a DNA polymerase, DNA Pol V, able to replicate over abasic sites (33, 44), thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimers, and pyrimidine-pyrimidone [6-4] photoproducts (43). The recA gene encodes RecA protein, the major bacterial DNA recombinase (17). RecA protein not only plays a direct role in TLS but also acts as the inducer of the SOS response (21). Homologs of both UmuC (9, 11–13, 18, 46, 50) and RecA (17, 35, 45) have been identified in all three kingdoms of life.

In response to DNA damage, the RecA protein binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), forming a nucleoprotein filament (17). This filament is central to at least four roles of the RecA protein within the cell. First, it acts as the cell's internal sensor of DNA damage by acting as a coprotease to facilitate the autodigestion of LexA repressor (21). This autodigestion inactivates the transcriptional repressor activity of LexA, thus leading to induction of the SOS regulon (20). Second, this nucleoprotein filament acts in homologous recombination, a major accurate DNA repair pathway (17). Third, RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments facilitate the autodigestion of UmuD in a manner similar to that of LexA (2, 36). This autodigestion serves to remove the N-terminal 24 residues of UmuD to yield UmuD′, thereby activating it for its role in TLS (27). Finally, these RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments serve a direct role in umuDC-dependent TLS (4, 27, 42).

In response to DNA damage, the umuDC gene products act in two temporally separate pathways to promote cell survival. First, uncleaved UmuD, together with UmuC, acts as part of a cell cycle checkpoint control that serves to regulate DNA synthesis in response to DNA damage, thereby allowing additional time for accurate repair processes such as nucleotide excision repair to repair lesion prior to attempts to replicate the damaged DNA (29). Second, UmuD′, together with UmuC, functions as a DNA polymerase to facilitate replication over any remaining unrepaired or irreparable lesions (33, 44). Thus, RecA-ssDNA-facilitated autodigestion of UmuD to yield UmuD′ appears to serve as the molecular switch that regulates these two roles of the umuDC gene products, thereby ensuring their proper temporal ordering (27, 29, 40).

In addition to their roles in cell survival following DNA damage, the umuDC gene products confer a cold-sensitive growth phenotype when overexpressed (24). This cold sensitivity correlates with a rapid inhibition of DNA synthesis, without a detectable effect on protein synthesis (24, 26). We have previously characterized this cold sensitivity associated with overproduction of the umuDC operon (30). These studies indicated that uncleaved UmuD, together with UmuC, conferred a more severe cold sensitivity than did UmuD′ together with UmuC. However, we nonetheless observed a significant degree of cold sensitivity when UmuD′ was overproduced together with UmuC.

To establish whether or not umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is attributable to the roles of the umuDC gene products in the checkpoint control, or whether it is due in part to functions of the umuDC gene products necessary for both the checkpoint control and TLS, we have further characterized the genetic and biochemical requirements of the umuDC gene products necessary for their ability to confer the cold sensitivity. In this study, we used derivatives of the moderate to low-copy-number plasmid pSC101 that expressed various umuDC gene products from the native umuDC promoter. However, their expression was not efficiently repressed by LexA repressor because they contain a base substitution mutation in their operator site that results in reduced affinity for the LexA protein (37). Using these plasmids, we found that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity does not require those elements of UmuD′ or UmuC function that are specifically required for TLS but rather appears to be attributable to those elements of umuDC gene product function that are involved in the checkpoint control. We propose a model for how elevated levels of UmuD, but not UmuD′, together with UmuC, might lead to the inhibition of growth at low temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteriological techniques.

The E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani medium (25). When indicated, ampicillin and spectinomycin were added to the growth medium to final concentrations of 150 and 60 μg/ml, respectively. Transformation of E. coli with plasmid DNA was performed by the calcium chloride technique as described elsewhere (25). Plasmid DNAs were purified using a QIA-Spin plasmid preparation kit from Qiagen according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Plasmids pGYDC104 (oc1 [operative constitutive mutation] umuDC104), pGYDC125 (oc1 umuDC125), and pGYDCΔ397–422 (oc1 umuDCΔ397–422) encode umuC derivatives bearing an aspartate-to-asparagine change at position 101 (umuC104 [16]), an alanine-to-valine change at position 39 (umuC125 [23]), and a deletion of residues 397 to 422 (umuCΔ397–422), respectively, and were generated from pGY9739 (oc1 umuD+C+) using a Quickchange kit from Stratagene according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The presence of the correct missense mutation in both pGYDC104 and pGYDC125 was confirmed by automated DNA sequence analysis (data not shown); pGYDCΔ397–422 was confirmed by Western blot analysis using affinity purified anti-UmuC polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or characteristicsd | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| AB1157 | lexA+recA+sulA+umuD+C+ | Laboratory stock |

| KM1190 | AB1157, lexA51(Def) sulA11 | Laboratory stock |

| GW8017 | AB1157, ΔumuDC595::cat | Laboratory stock |

| WBY11 | ΔrecA ΔumuDC595::cat | Z. Livneh (34) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGB2 | Spr, pSC101 derivative | R. Woodgate (3) |

| pGY9739 | pGB2; oc1 umuD+umuC+ in HpaI fragment | S. Sommer and A. Bailone (37) |

| pGY9738 | pGB2; oc1 umuD′ umuC+ in HpaI fragment | S. Sommer and A. Bailone (37) |

| pGYDΔC | pGB2; oc1 umuD+ ΔumuC in HpaI fragment | This work |

| pGYDC104 | pGB2; oc1 umuD+umuC104a in HpaI fragment | This work |

| pGYDC125 | pGB2; oc1 umuD+umuC125b in HpaI fragment | This work |

| pGYDCΔ397–422 | pGB2; oc1 umuD+umuCΔ397–422 in HpaI fragment | This work |

| pMal-c2 | Apr, pBR322 derivative, allows for overexpression of proteins bearing N-terminal fusion to MBP under Ptac control | New England BioLabs |

| pMAC | pMal-c2; umuC+ | Z. Livneh (34) |

| pMACΔ397–422 | pMal-c2; umuCΔ397–422c | This work |

| pMACΔ278–422 | pMal-c2; umuCΔ278–422c | This work |

| pMACΔ150–422 | pMal-c2; umuCΔ150–422c | This work |

| pMACΔ87–422 | pMal-c2; umuCΔ87–422c | This work |

Contains, in addition to an aspartate 101-to-asparagine change (16), a silent mutation (GCA→GCC) at alanine 103. The latter mutation disrupts a BsmI restriction site and was included to facilitate its identification.

Contains an alanine 39-to-valine change (23).

See Fig. 3A for a schematic representation of functional domains of UmuC.

Sp, spectinomycin; Ap, ampicillin.

FIG. 1.

Steady state levels of various umuDC gene products expressed from the indicated plasmid contained in the lexA+ ΔumuDC E. coli strain GW8017. Cells equivalent to 0.1 OD595 units for each strain were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 15% gels, transferred to PVDF membranes, and processed as Western blots with either affinity-purified polyclonal anti-UmuC or affinity-purified polyclonal anti-UmuD/D′ antibodies prior to chemiluminescence detection as described elsewhere (28). The anti-UmuC antibody preparation used here detected UmuCΔ397–422 nearly as well as it did the full-length UmuC protein (Fig. 3B). Lanes: 1 and 2, no UmuDC; 3, UmuD+ and UmuC+; 4, UmuD′ and UmuC+; 5, UmuD+ and UmuC125; 6, UmuD+ and UmuC104; 7, UmuD+ only; 8, UmuD+ and UmuCΔ397–422.

pGYDΔC, a derivative of pGY9739, was constructed by MluI restriction followed by end filling of the 3′ overhangs using the Klenow fragment of DNA Pol I and all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) prior to religation of the blunt-ended DNA. pGY9739 contains a single MluI restriction site within the umuC gene. After end filling and ligation of the blunt-ended DNA with T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs), a frameshift mutation was introduced after the coding sequence for residue 9, resulting in an opal stop codon (TGA) at the position that would otherwise code for residue 16. Plasmid DNA isolated from transformants was screened for resistance to MluI digestion, and the ΔumuC genotype was confirmed by Western blot analysis using affinity-purified polyclonal anti-UmuC antibodies (Fig. 1).

Construction and purification of MBP-UmuC derivatives.

The UmuC derivatives shown in Fig. 3A bearing nested deletions of C-terminal UmuC sequences were generated from pMAC by digestion with BamHI, XmnI, HindIII, or SalI, or combinations of these enzymes, followed by ligation of the DNA with or without prior treatment with all four dNTPs (Pharmacia) and the Klenow fragment of DNA Pol I (New England BioLabs) as described below. pMAC is a pMal-c2 (New England BioLabs) derivative that expresses maltose binding protein (MBP) fused to the N terminus of UmuC (34) and contains two sites for each of the restriction enzymes listed above; one is within the umuC coding sequence, and the other is within the pMal-c2 multiple cloning site located immediately downstream of the cloned umuC gene. pMACΔ397–422 lacks residues 397 to 422 of UmuC and was generated by BamHI digestion of pMAC prior to treatment with T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs). pMACΔ278–422 (lacking residues 278 to 422) and pMACΔ87–422 (lacking residues 87 to 422) were generated by digestion with XmnI and BamHI or SalI and HindIII, respectively, followed by treatment with all four dNTPs and the Klenow fragment of DNA Pol I prior to ligation with T4 DNA ligase. pMACΔ150–422 (lacking residues 150 to 422) was generated by digestion with HindIII prior to treatment with T4 DNA ligase. pMACΔ150–422 contains the small HindIII DNA fragment corresponding to the C-terminal portion of the umuC gene in the reverse orientation. Amino acids introduced onto each of the UmuC derivatives prior to the stop codon by the above treatments are indicated by one-letter code in Fig. 3A.

FIG. 3.

UmuD and UmuD′ both interact with the C terminus of UmuC. (A) Primary structures of the UmuC derivatives containing nested deletions of C-terminal sequences, shown relative to the proposed domain structure of the full-length UmuC. Proposed domains of UmuC are adapted from references 11 and 13 and are based on sequence similarity of UmuC to other members of the UmuC-DinB-Rad30-Rev1 superfamily. Amino acids introduced onto each of the UmuC derivatives prior to their stop codons as a result of their construction are indicated by one-letter code. (B) The ability of each UmuC derivative to interact with 32P-labeled UmuD or UmuD′, measured using a membrane-based assay described previously (40). Two membranes were processed as Western blots with either polyclonal anti-MBP (α-MBP) or affinity-purified polyclonal anti-UmuC (α-UmuC) antibody prior to chemiluminescence detection as described elsewhere (28, 40). The majority of the epitopes recognized by the anti-UmuC antibody preparation used here were located within the C-terminal 145 amino acid residues. The remaining two membranes were probed with either 32P-labeled UmuD or 32P-labeled UmuD′ as described previously (40). (C) Quantitation of the amount of UmuD (black bars) and UmuD′ (gray bars) retained by each UmuC derivative in panel B, performed as described in Materials and Methods and expressed as a percentage of that observed for the full-length MBP-UmuC, which was set at 100%.

Full-length MBP-UmuC and its derivatives were overexpressed using E. coli WBY11 as described previously (34) and then purified by affinity chromatography on amylose affinity resin (New England BioLabs) as recommended by the manufacturer. MBP was purified from pMAL-c2 in a similar manner. All protein preparations were >90% pure (data not shown).

Interactions of MBP-UmuC derivatives with UmuD and UmuD′ in vitro.

One hundred picomoles of each MBP-UmuC derivative in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)–75 mM sodium chloride–1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) was applied to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore) in quadruplicate, using a Dot Blot manifold (Bio-Rad) as described elsewhere (40). The membrane was then washed in the above buffer containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20, followed by blocking for 2 h in the same buffer containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin. Two of the four membranes were then processed as Western blots using either polyclonal antibodies specific to MBP (New England BioLabs) or affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies specific to UmuC. The remaining two membranes were probed with purified 32P-labeled UmuD or UmuD′ for 60 min at room temperature with gentle rocking as described elsewhere (40). Membranes were then washed three times for 5 min each in the same buffer prior to being dried and exposed to film as described previously (40). After autoradiography, the membranes were cut, using the autoradiogram as a guide, and the amount of radioactivity in each piece was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy.

DNA gel mobility shift.

Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 200 ng of double-stranded or 100 ng of single-stranded M13mp18 viral DNA (New England BioLabs), as indicated, together with the indicated levels of MBP, MBP-UmuC, or the MBP-UmuC derivatives, in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.8)–10 mM MgSO4–1 mM DTT–5% glycerol were assembled on ice. The mixtures were then incubated at room temperature for 20 min prior to electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose gels run in 0.5× TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) buffer (1). After electrophoresis, gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under illumination by UV light.

In vitro solution cross-linking of purified UmuD and UmuD′.

For formaldehyde cross-linking, 5 μmol of UmuD or UmuD′, purified as described elsewhere (19), was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)–100 mM potassium glutamate–10 mM magnesium acetate–1 mM DTT. Formaldehyde (Mallinckrodt) was then added to 1% (final concentration), and incubation at room temperature was continued for an additional 30 min, at which time the reaction was quenched by addition of 4× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 8% SDS, 0.4% bromophenyl blue, 40% glycerol) containing 5% mercaptoethanol. For glutaraldehyde cross-linking, 5 μmol of highly purified UmuD or UmuD′ was incubated at 4°C for 30 min in 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0)–75 mM sodium chloride–1 mM DTT. Glutaraldehyde (Polysciences, Inc.) was then added to 0.05% (final concentration), and incubation was continued at 4°C for an additional 15 min, at which time reactions were quenched by addition of 5 μl 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8). UmuD and UmuD′ cross-linking efficiency was monitored by Western blotting using affinity-purified polyclonal anti-UmuD/D′ antibodies and chemiluminescence detection, as described elsewhere (28, 40).

RESULTS

umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity requires an activity of uncleaved UmuD together with UmuC.

Our previous analyses of umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity concentrated primarily on the reduced capacity of an E. coli lexA(Def) strain carrying a pBR322 derivative containing the umuDC operon to grow at lower temperatures (24, 30). Although these analyses indicated that uncleaved UmuD together with UmuC conferred a greater degree of cold sensitivity than did UmuD′ together with UmuC, overexpression of umuD′C nonetheless conferred a significant cold sensitivity (30). It was therefore not possible to distinguish whether the cold sensitivity was due to function(s) of uncleaved UmuD/UmuC involved in the checkpoint control (29) or to functions of the umuDC gene products required for both the checkpoint control and TLS. To address this issue, we investigated the ability of significantly lower level of expression of umuDC and umuD′C from the low-copy-number pSC101 derivative pGB2 to confer the cold-sensitive growth phenotype, using the previously described quantitative plating assay (26, 30). Furthermore, to allow us to analyze the abilities of umuDC and umuD′C to confer cold sensitivity in the absence of induction of other SOS-regulated gene products, we have made use of a umuDC promoter that contains a single base pair change resulting in an operator constitutive mutation (oc1) which eliminates much of the repression normally conferred by binding of the LexA repressor (37). pGY9739 expresses the umuDC gene products regardless of the lexA genotype by virtue of the oc1 mutation. while pGY9738 expresses the umuD′C gene products by virtue of the same oc1 mutation.

With these conditions, modest overexpression of uncleaved UmuD together with UmuC did confer cold sensitivity for growth upon a lexA+ strain, consistent with our earlier observations (24, 30). As before (24), this cold sensitivity required both UmuC and UmuD since a plasmid expressing only UmuD did not confer the cold sensitivity (Table 2). In contrast, modest overexpression of umuD′ together with umuC in a lexA+ E. coli strain did not confer a cold-sensitive growth phenotype (Table 2). As a control to confirm that cold sensitivity was due to the elevated levels of UmuD and UmuC and not some other aspect of the plasmid expressing the Umu proteins, we measured the plating efficiencies for the pGB2 parental plasmid. As expected, pGB2 did not confer cold sensitivity to a lexA+ strain, indicating that the cold sensitivity for growth conferred by pGY9739 (oc1 umuDC) was in fact due to the elevated levels of UmuD and UmuC.

TABLE 2.

| Plasmid | umuD and umuC allelesb | Plating efficiency (30°C/42°C)c

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| AB1157 (lexA+) | KM1190 [lexA51(Def)] | ||

| pGB2 | None | 1.08 | 1.13 |

| pGY9739 | oc1 umuD+umuC+ | 4.5 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−3 |

| pGY9738 | oc1 umuD′ umuC+ | 0.94 | 1.00 |

| pGYDΔC | oc1 umuD+ ΔumuC | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| pGYDC104 | oc1 umuD+umuC104 | 2.3 × 10−3 | 2.5 × 10−3 |

| pGYDC125 | oc1 umuD+umuC125 | 0.84 | 0.53 |

| pGYDCΔ397–422 | oc1 umuD+umuCΔ397–422 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

Similar results were observed for an E. coli strain bearing a lexA(Def) allele; modest overexpression of UmuD together with UmuC conferred a cold-sensitive growth phenotype, while overexpression of UmuD alone or together with UmuC did not (Table 2). It has been previously established that pGY9738 expresses approximately twice as much UmuD in a lexA(Def) strain as in a strain bearing an active LexA repressor (37). The similar plating efficiencies of derivatives of the lexA+ and the lexA(Def) strains carrying pGY9739 (oc1 umuDC) and pGY9738 (oc1 umuD′C) indicate that this twofold increase in the UmuD concentration (and presumably the UmuC concentration as well) did not significantly affect the extent of the cold sensitivity. This observation confirms our earlier finding that the umuDC genes were the only SOS-regulated genes whose elevated expression was necessary to confer cold sensitivity for growth (30).

To rule out the possibility that the observed differences between umuDC and umuD′C in the ability to confer cold sensitivity were due simply to differences in the relative abundance of their gene products, we determined their steady-state levels by immunoblotting of whole-cell lysates using affinity-purified antibodies specific to UmuD and UmuC. As shown in Fig. 1, UmuD and UmuC expressed from the oc1 promoter were slightly less abundant than were UmuD′ and UmuC. These findings are consistent with reports by Frank et al. that in vivo, UmuD and UmuC are degraded by the Lon protease while UmuD′ is not, and hence UmuD and UmuC are less abundant in vivo than are UmuD′ and UmuC (7). Furthermore, the steady-state level of UmuD expressed from the oc1 umuDΔC allele was also somewhat lower than the level observed from the oc1 umuD+C+ allele. Thus, some specific feature of the UmuD2C complex must be important for cold sensitivity.

umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity and umuDC-dependent translesion DNA synthesis are genetically separable by mutant umuC alleles.

Previous analyses of umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity indicated that cleavage of UmuD was not necessary for cold sensitivity, consistent with our finding that UmuD together with UmuC conferred a greater degree of cold sensitivity than did UmuD′ together with UmuC (30). Since UmuD′ activates UmuC as a lesion bypass DNA polymerase but UmuD does not (33), these findings, taken together, suggested that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity involves a noncatalytic activity of UmuC. We were interested in establishing whether or not the DNA polymerase activity of UmuC was required for umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity.

The umuC104 allele was identified as a mutation that conferred a nonmutable phenotype upon E. coli (38), and it was later shown that the UmuD′2C104 complex is inactive as a DNA polymerase (33, 44). The umuC125 allele is largely proficient for SOS mutagenesis but sensitizes E. coli to killing by UV light (23). Interestingly, it was also found to be less efficient at conferring umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity than was the wild-type umuC allele, although a lexA(Def) strain bearing umuDC125 on a pBR322 derivative did not grow well in liquid culture at 30°C (23). Therefore, we constructed derivatives of the oc1 umuDC plasmid described above containing the umuC104 and umuC125 alleles so that we could directly compare their phenotypes with respect to SOS mutagenesis and umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity. We did not introduce these umuC mutations into the oc1 umuD′C-expressing plasmid, as it did not confer a cold-sensitive growth phenotype.

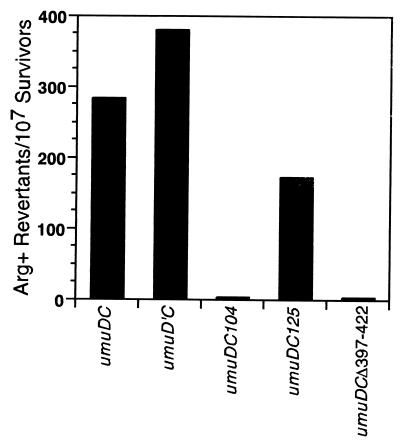

Consistent with earlier reports (23, 38), the strain carrying umuDC104 was inactive for SOS mutagenesis while that carrying the umuDC125 derivative was ∼60% as proficient as the strain carrying the wild-type operon when the various umuDC operons were expressed from the oc1 promoter in a ΔumuDC strain and mutagenesis activity was measured using the argE3(Oc)→Arg+ reversion assay (Fig. 2). However, in contrast to their effects on SOS mutagenesis, umuDC104 was as proficient at conferring cold sensitivity as was the wild-type operon, while umuDC125 was unable to confer any cold sensitivity under these new conditions, regardless of the lexA genotype (Table 2). To confirm that these results were not due to instability of the UmuC125 mutant protein, we measured the steady-state levels of the umuDC104 and umuDC125 gene products by Western blot analysis as described above (Fig. 1). The steady-state level of the UmuC104 mutant protein was similar to that of wild-type UmuC grown under identical conditions, while the level of the UmuC125 mutant protein was only slightly reduced. The level of UmuD in each case was similar to that observed for the wild-type control. Thus, taken together, these results are consistent with our earlier observation that noncleavable mutants of UmuD are proficient for conferring cold sensitivity (30) and indicate that UmuDC-dependent cold sensitivity can be genetically separated from the ability of the UmuD′2C complex to function as a DNA polymerase. The phenotypes of the umuDCΔ397–422 gene products are discussed below.

FIG. 2.

Effects of plasmids carrying various wild-type or mutant umuDC or umuD′C operons on UV (20 J/m2)-induced reversion of argE3(Oc)→Arg+ in ΔumuDC E. coli strain GW8017, measured as described elsewhere (48).

The C terminus of UmuC is required for its interaction with UmuD and UmuD′ but not for the ss-DNA binding activity of UmuC.

Recent biochemical studies have shown that UmuD′ and UmuC form a UmuD′2C complex that functions as a DNA polymerase in TLS (44, 52). We were curious about whether the umuDC gene products conferred cold sensitivity through separate actions of UmuD and UmuC or whether the umuDC gene products conferred cold sensitivity through an activity of the UmuD2C complex. There has been at least one unpublished account of a direct physical interaction between UmuD and UmuC, referred to by Woodgate et al. (52). Although Jonczyk and Nowicka did not detect an interaction between UmuD and UmuC in vivo using the yeast two-hybrid system, they did detect an interaction between UmuD′ and UmuC (14). Furthermore, they reported that small deletions of either N- or C-terminal sequences of UmuC destroyed its ability to interact with UmuD′ as measured with the yeast two-hybrid system (14).

We reasoned that both UmuD and UmuD′ would likely require common elements of UmuC for their interactions. Therefore, we generated a series of nested C-terminal deletions of UmuC. We chose to generate C-terminal deletions because comparison of UmuC to other members of the UmuC-DinB-Rad30-Rev1 superfamily indicated that the C-terminal portion of UmuC was poorly conserved, suggesting that it was not required for the catalytic DNA polymerase activity (11, 13) (Fig. 3A). By contrast, the N-terminal half of UmuC is highly conserved among members of the UmuC-DinB-Rad30-Rev1 superfamily (11, 13) (Fig. 3A). For these deletions, we used an MBP-UmuC fusion, a soluble and active form of the UmuC protein containing an N-terminal fusion to the malE gene product of E. coli (34). The primary structures of the various C-terminal deletions of MBP-UmuC are shown in Fig. 3A.

First, we tested these UmuC derivatives for the ability to interact with UmuD and UmuD′ in vitro, using a modified version of a membrane-based interaction assay involving the use of radiolabeled derivatives of UmuD and UmuD′ that has proven effective for characterizing protein-protein interactions in the past (40). Briefly, we applied similar molar amounts of each MBP-UmuC derivative, including MBP as a negative control, to a PVDF membrane under native conditions and then probed the membrane with radiolabeled UmuD or UmuD′. Although this assay does not allow a quantitative measure of binding constants and therefore significantly underestimates binding differences, it is an effective method for comparing relative binding affinities. As shown in Fig. 3, both UmuD and UmuD′ interact essentially similarly with UmuC in vitro. However, UmuD′ did not interact well with the MBP-UmuC deletion lacking the C-terminal 26 residues of UmuC protein (MBP–UmuCΔ397–422), and interacted even less well with UmuC derivatives containing larger C-terminal truncations (Fig. 3B and C). Similar results were observed for UmuD, consistent with our hypothesis that UmuD and UmuD′ might make similar contacts with UmuC. Furthermore, our finding that UmuD and UmuD′ retained limited abilities to interact with all four derivatives of MBP-UmuC is consistent with the finding by Jonczyk and Nowicka (14) that N-terminal sequences of UmuC may also important for its interaction with UmuD′.

To rule out the possibility that the MBP-UmuC C-terminal deletions interacted poorly with UmuD and UmuD′ because they did not have a native form, despite being expressed and purified in a soluble form, we wished to establish that they did in fact retain some known biochemical property, consistent with the notion that they were properly folded. Biochemical characterization of the UmuD′2C complex has indicated that it can bind to ssDNA but not double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (1). This DNA binding activity is presumably attributable to UmuC, as neither UmuD nor UmuD′ binds DNA (8). Therefore, we measured the abilities of the various MBP-UmuC derivatives to bind to ssDNA. Consistent with earlier reports (1), MBP-UmuC bound to ssDNA in an apparently cooperative fashion in vitro (Fig. 4A) but did not bind to dsDNA in vitro in a DNA mobility shift assay (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, deletion of the C-terminal 26 residues of UmuC had only a small effect on its ability to bind ssDNA (Fig. 4C and D), despite inactivating its role in SOS mutagenesis (Fig. 2), indicating that its inability to interact with UmuD and UmuD′ was due to the loss of essential sequences and not to an overall effect on the structure of the truncated protein. Consistent with this interpretation, even deletion of the C-terminal 145 residues of UmuC did not completely eliminate the ability of this derivative to bind ssDNA (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that deletion of the C-terminal 26 residues of UmuC specifically affects its ability to interact with both UmuD and UmuD′, suggesting a mechanism for its inactivity in SOS mutagenesis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 4.

DNA binding activities of various MBP-UmuC derivatives bearing nested deletions of C-terminal UmuC sequences. The ability of wild-type MBP-UmuC to bind ssDNA (A) or dsDNA (B) was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The following amounts of MBP-UmuC were added to each reaction: lanes 1 and 7, 0 pmol; lane 2, 0.5 pmol; lanes 3 and 8, 1 pmol; lanes 4 and 9, 3 pmol; lanes 5 and 10, 6 pmol; and lanes 6 and 11, 12 pmol. The positions of unbound (or free) DNA (F) and protein-DNA complexes (C) are indicated. I, II, and III represent forms I (supercoiled), II (knicked), and III (linear), respectively, of dsDNA. (C) The ability of the indicated UmuC derivatives to bind ssDNA was measured as described for panel A. Wild-type UmuC was assayed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 pmol, and UmuC derivatives bearing C-terminal deletions were assayed at 3, 6, 12, and 24 pmol. Lane 1 corresponds to the 0-pmol MBP-UmuC control. (D) Quantitation of the results shown in panel C, using the Molecular Analyst software package (Bio-Rad). Symbols: ■, MBP-UmuC; ●, MBP–UmuCΔ397–422; ▴, MBP–UmuCΔ278–422; ⧫, MBP–UmuCΔ150–422; □, MBP–UmuCΔ87–422.

The UmuD2C complex is required for umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity.

Given our finding that UmuCΔ397–422 was deficient for interaction with UmuD (and with UmuD′) but retained an ability to interact with ssDNA, we were interested in determining whether this mutant allele was competent for SOS mutagenesis and for conferring cold sensitivity for growth. Therefore, we constructed a derivative of the oc1 umuDC plasmid that contained the umuCΔ397–422 allele and tested its ability to confer cold sensitivity. Our finding that the oc1 umuDCΔ397–422 construct was unable to confer the cold-sensitive growth phenotype, regardless of the lexA genotype (Table 2), is consistent with the notion that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is due to an activity of the UmuD2C complex and not to the separate actions of UmuD and UmuC. At the very least, it would appear that the ssDNA binding activity of UmuC is in itself insufficient, together with UmuD, to confer cold sensitivity. Our finding that the steady-state levels of UmuD2CΔ397–422 were similar to those observed for wild-type UmuD2C (Fig. 1) rules out the possibility that UmuD2CΔ397–422 was unable to confer cold sensitivity and was inactive for SOS mutagenesis because it was present at insufficient levels. Finally, that umuDCΔ397–422 was inactive for SOS mutagenesis (Fig. 2), taken together with the our findings that the C-terminal 26 residues of UmuC are required for its interaction with both UmuD and UmuD′, suggests that interaction of the umuD and umuC gene products is a common activity required for both cold sensitivity and TLS.

Structural differences between UmuD and UmuD′ consistent with their different physiological roles.

Since the only difference between UmuD and UmuD′ at the primary structural level is the presence or absence of the N-terminal 24 residues, it is likely that the structures of the UmuD2 homodimer and the UmuD′2 homodimer will be found to be similar to each other. However, it is clear that they must differ from each other in some significant way in order for UmuD and UmuD′ to act in such diverse fashions. Although the three-dimensional structure of the UmuD′2 homodimer is known, both in a crystal (31) and in solution (5; A. E. Ferentz, G. C. Walker, and G. Wagner, unpublished data), that of the UmuD2 homodimer is not. These analyses have indicated that the UmuD monomer consists of a C-terminal globular domain with an extended N-terminal arm (comprising residues 25 to 39) that is mobile in solution (5, 31). In the UmuD′ crystal, two dimerization interfaces were observed (31). One is known to be the dimerization interface for the UmuD′2 homodimer in solution (5). It has been suggested that the other interface may be important for the formation of UmuD′ filaments and that these filaments may be important for SOS mutagenesis (32). However, these UmuD′ filaments were not observed in the solution structure of the UmuD′2 homodimer that was recently solved by nuclear magnetic reconance spectroscopy (5; Ferentz et al., unpublished).

Regardless of whether or not UmuD′2 homodimers interact to form some type of physiologically relevant multimeric species, treatment of purified UmuD′ protein in vitro with glutaraldehyde leads to the fixation of UmuD′ multimers. However, it is important to stress that fixation of UmuD or UmuD′ as multimers with cross-linking agents does not necessarily mean that they form filaments. By contrast, only barely detectable levels of similar multimers were observed following glutaraldehyde treatment of purified UmuD protein in vitro (32) (Fig. 5). However, treatment of purified UmuD or UmuD′ with formaldehyde in vitro leads to the fixation of multimers of both UmuD and UmuD′ (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the apparent sizes of these multimeric species are consistent with them corresponding to dimers, trimers, and tetramers of UmuD2 or UmuD′2 homodimers. It has been demonstrated that the N-terminal arms of UmuD′ (residues 25 to 39), which are mobile in solution (5), are required for its fixation as multimers with glutaraldehyde (32). We suspect that the structures of the N-terminal arms of UmuD (residues 1 to 39) are likewise responsible for its inability to be fixed as multimers with glutaraldehyde and may in fact be important for its fixation as multimers with formaldehyde.

FIG. 5.

Both UmuD and UmuD′ can be trapped as multimers in vitro. Treatment of purified UmuD (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or UmuD′ (lanes 2, 4, and 6) with formaldehyde (Form) or glutaraldehyde (Glut) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of free UmuD and UmuD′, UmuD2 and UmuD′2 homodimers, and UmuD and UmuD′ multimers are indicated. Positions of molecular weight markers (GIBCO-BRL) are indicated at the right.

DISCUSSION

umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is due to an activity of UmuD2C and is independent of the DNA polymerase activity of UmuC protein.

The results presented above indicate that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is not due to an oversupply of the DNA polymerase activity of the UmuC protein but rather is due entirely to an activity of uncleaved UmuD acting together with UmuC. This conclusion is based on our findings that (i) modest overexpression of UmuD together with UmuC leads to a cold sensitivity for growth, while modest overexpression of UmuD′ together with UmuC under the identical conditions does not, and (ii) the umuC104 allele, which encodes an aspartate-to-asparagine change at position 101 that inactivates the catalytic DNA polymerase activity, was proficient for conferring cold sensitivity but deficient for SOS mutagenesis, while the umuC125 allele, which encodes an alanine-to-valine change at position 39, was deficient for conferring cold sensitivity but proficient for SOS mutagenesis. Finally, our findings that a UmuC derivative lacking its C-terminal 26 residues was unable to interact with both UmuD and UmuD′, and was similarly unable to confer cold sensitivity when overexpressed together with UmuD, suggests that cold sensitivity involves an activity of the UmuD2C complex and is not due to the separate actions of the UmuD and UmuC proteins.

Recently we have described a role for uncleaved UmuD together with UmuC in a DNA damage cell cycle checkpoint control (26, 29, 40). Our analyses of this role of the umuDC gene products suggested that UmuD and UmuC act to regulate DNA replication in response to DNA damage, thereby allowing additional time for accurate DNA repair pathways, such as nucleotide excision repair, to repair the damaged DNA (29). Such a mechanism would enhance cell survival following DNA damage by helping to prevent more serious types of DNA damage from occurring by the cell's attempts to replicate its damaged DNA. This ability of UmuD and UmuC to regulate DNA replication correlates with our previous finding that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity correlates with a rapid inhibition of DNA synthesis at the nonpermissive temperature (24, 26). These findings, taken together with the fact that UmuC125 is less efficient at conferring cold sensitivity (reference 23 and this report) and appears to be unable to regulate DNA replication in response to DNA damage (29), suggest that umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is a manifestation of the DNA damage checkpoint activity of UmuD and UmuC. The results described in this report indicating that modest overexpression of UmuDC, but not UmuD′C, confers a cold sensitivity for growth and that the DNA polymerase activity of UmuC is not required for this UmuDC-dependent cold sensitivity lead us to conclude that the cold sensitivity results from the inappropriately high expression of the UmuD- and UmuC-dependent regulation of the cell cycle that normally occurs in response to DNA damage.

We have previously suggested that an interaction between UmuD and the β processivity subunit of DNA polymerase III is important for the DNA damage checkpoint role of UmuD2C (29, 40, 41). Given these very strong similarities between the UmuD2C-dependent checkpoint control and UmuD2C-dependent cold sensitivity, we now suggest that the UmuD-β interaction is also important for cold sensitivity (Fig. 6). It is worthwhile emphasizing that although UmuD interacts with β more strongly than does UmuD′, UmuD′ is nonetheless able to interact physically with β in vitro (40). Consequently, we suggest that the ability of the comparably higher levels of UmuD′ together with UmuC expressed from a pBR322 derivative in a lexA(Def) strain to confer cold sensitivity (30) is similarly due to an ability of higher levels of UmuD′ to mimic the cell cycle checkpoint activity of UmuD that presumably involves, at least in part, a direct interaction with β. This interaction of UmuD2C, or comparatively higher levels of UmuD′2C, with β may lead to either the titration and/or sequestration of β away from the replication fork, or formation of a multiprotein complex that perturbs the polymerase activity of Pol III, resulting in the inhibition of DNA synthesis that we have observed (24, 26). Alternatively, or in addition, interactions between the α (catalytic) subunit of DNA Pol III and the UmuD or UmuD′ proteins might constitute a portion of the cold sensitivity (Fig. 6). However, given that (i) overexpression of α does not affect the extent of cold sensitivity conferred by elevated levels of the umuDC gene products (39) and (ii) UmuD′ interacts more strongly with α than does UmuD in vitro (40), we think it is unlikely that this interaction is a significant component of the UmuD2C-dependent cold sensitivity described in this report. Finally, it is important to stress that it is still unclear whether or not β plays a role in TLS in the living cell (41); although one group has reported an absolute requirement of the β clamp and clamp loader complex of Pol III for UmuD′2C-dependent TLS in vitro (44), a second group, using a slightly different in vitro system, did not find a β requirement (33). Thus, our model (Fig. 6) is intended to describe only the putative role of β in the umuDC-dependent DNA damage checkpoint control. Experiments to test the validity of this model are under way.

FIG. 6.

Model of a possible mechanism for umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity (see text for details). The two physiologically relevant roles of the umuDC gene products (DNA damage checkpoint control and translesion DNA synthesis) are indicated by the shaded boxes. “More UmuD2C” and “More UmuD′2C” denote increases in gene dosage by virtue of their presence on either a moderate- to low-copy-number pSC101 derivative, or a higher-copy-number pBR322 derivative, as indicated.

The C-terminal 26 residues of UmuC are important for the interaction of UmuC with UmuD and UmuD′.

Our finding that UmuD interacts with UmuC through its C terminus contrasts with the findings of Jonczyk and Nowicka, who failed to detect an interaction between UmuD and UmuC with the yeast two-hybrid system (14). We suggest that their inability to observe an interaction between UmuD and UmuC may have been due to constraints imposed by fusion of the Umu proteins to the trans-acting tags. Consistent with this possibility, Jonczyk and Nowicka observed an interaction between UmuD′ and UmuC only if UmuC was expressed as a fusion to the DNA binding domain of GAL4 and not if it was fused to the trans-activation domain of GAL4 (14).

Furthermore, our observation that MBP–UmuCΔ397–422 was deficient for interaction with both UmuD and UmuD′ is consistent with those of Jonczyk and Nowicka, who reported that small deletions of either N- or C-terminal sequences of UmuC essentially eliminated its ability to interact with UmuD′ as measured with the yeast two-hybrid system (14). We have thus extended their findings by demonstrating a deficiency for the MBP–UmuCΔ397–422 protein to interact with both UmuD and UmuD′ in vitro.

Both UmuD and UmuD′ can form multimers in vitro.

Given the striking differences between the roles of the umuDC gene products in the DNA damage checkpoint control and in TLS, and the fact that cleavage of UmuD to yield UmuD′ appears to serve a critical role in insuring the proper temporal ordering of these two pathways (27, 29, 40), it seems likely that differences in the structures of UmuD and UmuD′ must be crucial for determining which biological role the umuDC gene products will play. Our finding that both UmuD and UmuD′ can form multimers in vitro, and that fixation of these UmuD and UmuD′ multimers is cross-linker specific, indicates that the structures of the respective multimers differ, consistent with the suggestion that UmuD and UmuD′ serve to differentially manage the activity of UmuC (40).

Since UmuD and UmuD′ differ only with respect to the presence or absence of the N-terminal 24 residues, it seems likely that their different behaviors with respect to their abilities to be cross-linked as multimers by glutaraldehyde likely relate to the different structures of their N-terminal arms. Viewed in this way, these results suggest that structural differences between the N-terminal arms of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 are crucial for regulating protein-protein interactions involving UmuD and UmuD′ and other proteins required for the checkpoint control and TLS, respectively. We have previously proposed that cleavage of UmuD to yield UmuD′ serves to free up the N-terminal arms of UmuD′2 such that they can interact with another protein or proteins important for SOS mutagenesis in a manner that was not possible for them when they were part of UmuD2 (28). We are currently investigating the intriguing possibility that the structures of the N-terminal arms in UmuD2 are important for interactions involving β and/or other proteins necessary for the checkpoint control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Suzanne Sommer and Adriana Bailone for plasmids pGY9738 and pGY9739, Roger Woodgate for plasmid pGB2, Zvi Livneh for plasmid pMAC and E. coli WBY11, and the members of our lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA21615 to G.C.W. from the National Cancer Institute. M.D.S. was supported by a fellowship (5 F32 CA79161-02) from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruck I, Woodgate R, McEntee K, Goodman M F. Purification of a soluble UmuD′C complex from Escherichia coli. Cooperative binding of UmuD′C to single-stranded DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10767–10774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burckhardt S E, Woodgate R, Scheuermann R H, Echols H. UmuD mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: overproduction, purification, and cleavage by RecA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1811–1815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churchward G, Belin D, Nagamine Y. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene. 1984;31:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutreix M, Moreau P L, Bailone A, Galibert F, Battista J R, Walker G C, Devoret R. New recA mutations that dissociate the various RecA protein activities in Escherichia coli provide evidence for an additional role for RecA protein in UV mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2415–2423. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2415-2423.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferentz A E, Opperman T, Walker G C, Wagner G. Dimerization of the UmuD′ protein in solution and its implications for regulation of SOS mutagenesis. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:979–983. doi: 10.1038/nsb1297-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez de Henestrosa A R, Ogi T, Aoyagi S, Chafin D, Hayes J J, Ohmori H, Woodgate R. Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1560–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank E G, Ennis D G, Gonzalez M, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Regulation of SOS mutagenesis by proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10291–10296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank E G, Hauser J, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Targeting of the UmuD, UmuD′, and MucA′ mutagenesis proteins to DNA by RecA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8169–8173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedberg E C, Gerlach V L. Novel DNA polymerases offer clues to the molecular basis of mutagenesis. Cell. 1999;98:413–416. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81970-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlach V L, Aravind L, Gotway G, Schultz R A, Koonin E V, Friedberg E C. Human and mouse homologs of Escherichia coli DinB (DNA polymerase IV), members of the UmuC/DinB superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11922–11927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson R E, Prakash S, Prakash L. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Poleta. Science. 1999;283:1001–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson R E, Washington M T, Prakash S, Prakash L. Bridging the gap: a family of novel DNA polymerases that replicate faulty DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12224–12226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonczyk P, Nowicka A. Specific in vivo protein-protein interactions between Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2580–2586. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2580-2585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenyon C J, Walker G C. DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch W H, Ennis D G, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Escherichia coli umuDC mutants: DNA sequence alterations and UmuD cleavage. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:443–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00265442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalczykowski S C, Dixon D A, Eggleston A K, Lauder S D, Rehrauer W M. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:401–465. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.401-465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulaeva O I, Koonin E V, McDonald J P, Randall S K, Rabinovich N, Connaughton J F, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Identification of a DinB/UmuC homolog in the archeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Mutat Res. 1996;357:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M H, Ohta T, Walker G C. A monocysteine approach for probing the structure and interactions of the UmuD protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4825–4837. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4825-4837.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little J W. LexA cleavage and other self-processing reactions. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4943–4950. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.4943-4950.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little J W, Mount D W. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell. 1982;29:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little J W, Mount D W, Yanisch-Perron C R. Purified lexA protein is a repressor of the recA and lexA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4199–4203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsh L, Nohmi T, Hinton S, Walker G C. New mutations in cloned Escherichia coli umuDC genes: novel phenotypes of strains carrying a umuC125 plasmid. Mutat Res. 1991;250:183–197. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90175-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh L, Walker G C. Cold sensitivity induced by overproduction of UmuDC in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:155–161. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.155-161.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murli S, Opperman T, Smith B T, Walker G C. A role for the umuDC gene products of Escherichia coli in increasing resistance to DNA damage in stationary phase by inhibiting the transition to exponential growth. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1127–1135. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1127-1135.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nohmi T, Battista J R, Dodson L A, Walker G C. RecA-mediated cleavage activates UmuD for mutagenesis: mechanistic relationship between transcriptional derepression and posttranslational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1816–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohta T, Sutton M D, Guzzo A, Cole S, Ferentz A E, Walker G C. Mutations affecting the ability of the Escherichia coli UmuD′ protein to participate in SOS mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:177–185. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.177-185.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opperman T, Murli S, Smith B T, Walker G C. A model for a umuDC-dependent prokaryotic DNA damage checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9218–9223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opperman T, Murli S, Walker G C. The genetic requirements for UmuDC-mediated cold sensitivity are distinct from those for SOS mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4400–4411. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4400-4411.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peat T S, Frank E G, McDonald J P, Levine A S, Woodgate R, Hendrickson W A. Structure of the UmuD′ protein and its regulation in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1996;380:727–730. doi: 10.1038/380727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peat T S, Frank E G, McDonald J P, Levine A S, Woodgate R, Hendrickson W A. The UmuD′ protein filament and its potential role in damage induced mutagenesis. Structure. 1996;4:1401–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuven N B, Arad G, Maor-Shoshani A, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB and is specialized for translesion replication. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31763–31766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuven N B, Tomer G, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis proteins UmuD′ and UmuC prevent lethal frameshifts while increasing base substitution mutations. Mol Cell. 1998;2:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seitz E M, Brockman J P, Sandler S J, Clark A J, Kowalczykowski S C. RadA protein is an archaeal RecA protein homolog that catalyzes DNA strand exchange. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1248–1253. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinagawa H, Iwasaki H, Kato T, Nakata A. RecA protein-dependent cleavage of UmuD protein and SOS mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1806–1810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommer S, Knezevic J, Bailone A, Devoret R. Induction of only one SOS operon, umuDC, is required for SOS mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:137–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00281612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinborn G. Uvm mutants of Escherichia coli K12 deficient in UV mutagenesis. I. Isolation of uvm mutants and their phenotypical characterization in DNA repair and mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;165:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00270380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton M D, Murli S, Opperman T, Klein C, Walker G C. umuDC-dnaQ interaction and its implications for cell cycle regulation and SOS mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1085–1089. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.1085-1089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton M D, Opperman T, Walker G C. The Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins UmuD and UmuD′ interact physically with the replicative DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12373–12378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutton M D, Smith B T, Godoy V G, Walker G C. The SOS response: recent insights into umuDC-dependent DNA damage tolerance. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:479–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweasy J B, Witkin E M, Sinha N, Roegner-Maniscalco V. RecA protein of Escherichia coli has a third essential role in SOS mutator activity. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3030–3036. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3030-3036.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang M, Pham P, Shen X, Taylor J-S, O'Donnell M, Woodgate M, Goodman M F. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerase IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature. 2000;404:1014–1018. doi: 10.1038/35010020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang M, Shen X, Frank E G, O'Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman M F. UmuD′(2)C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vispe S, Defais M. Mammalian Rad51 protein: a RecA homologue with pleiotropic functions. Biochimie. 1997;79:587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)82007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner J, Gruz P, Kim S R, Yamada M, Matsui K, Fuchs R P, Nohmi T. The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Mol Cell. 1999;4:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker G C. Inducible DNA repair systems. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:425–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker G C. Plasmid (pKM101)-mediated enhancement of repair and mutagenesis: dependence on chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;152:93–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00264945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witkin E M. Ultraviolet mutagenesis and inducible DNA repair in Escherichia coli. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:869–907. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.869-907.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodgate R. A plethora of lesion-replicating DNA polymerases. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2191–2195. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodgate R, Levine A S. Damage inducible mutagenesis: recent insights into the activities of the Umu family of mutagenesis proteins. Cancer Surv. 1996;28:117–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. UmuC mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: purification and interaction with UmuD and UmuD′. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]