Abstract

Purpose:

This study investigated conflict between sexual orientation and racial/ethnic identities as a mechanism linking minority stress to HIV-related outcomes among men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women and gender nonbinary (TGN) people of color (POC).

Methods:

We tested longitudinal mediation models with sexual orientation microaggressions, internalized heterosexism (IH), and sexual orientation concealment at Time 1, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and number of condomless anal sex (CAS) partners at Time 3, mediated by identity conflict at Time 2. Participants were 337 MSM and TGN POC. Data were collected in Chicago, Illinois, from September 2018 to February 2021.

Results:

Indirect associations of IH and sexual orientation concealment, respectively, at Time 1 with CAS partners at Time 3 through identity conflict at Time 2 were significant. Mediation models with sexual orientation microaggressions as the predictor and PrEP use as the outcome were not significant.

Conclusion:

Minority stress may contribute to identity conflict and increase CAS by isolating MSM and TGN POC from sexual and gender minority communities, thus restricting access to safer sex resources, and by increasing psychological distress and decreasing self-care (e.g., condom use).

Keywords: HIV, intersectionality, minority stress, people of color, sexual and gender minorities

Introduction

Sexual and gender minority people assigned male at birth (SGM-AMAB; i.e., cisgender men who have sex with men [MSM], transgender women and gender nonbinary [TGN] people AMABa) are overrepresented among new HIV infections.1,2 Within this group, alarming racial disparities persist: in 2018, Black and Latinx MSM accounted for 37% and 21%, respectively, of new HIV diagnoses among MSM.1 Among transgender women, 62% of Black/African American and 35% of Hispanic/Latina transgender women had HIV, compared to 17% of White transgender women.2

Although new HIV diagnoses declined by 15% among White MSM between 2014 and 2018, diagnoses among racial/ethnic minority MSM remained stable or increased,1 an indication that these communities are not benefitting from current HIV prevention efforts in the same way as White MSM. Black MSM were found to be half as likely as White MSM to have used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP; a daily oral medication to prevent HIV) in the last year, despite being equally as willing to take PrEP.3 Black and Latinx MSM and transgender women also have higher rates of PrEP discontinuation compared to their White counterparts.4 An understanding of the factors influencing PrEP uptake and condomless sex among MSM and TGN people of color (POC) is critical to reduce health disparities.

A growing body of research suggests that minority stress, the unique stress encountered by groups with marginalized social statuses,5 is related to poorer HIV outcomes. This includes experiences of heterosexism, frequently manifesting as microaggressions, or daily environmental, behavioral, and verbal occurrences that convey negative messages to marginalized individuals.6 Minority stress also includes internalized heterosexism (IH; internalization of negative views of oneself as a product of living within a heterosexist society) and concealment of sexual orientation.5

Discrimination and IH have been negatively associated with progression along the PrEP continuum,7 and sexual orientation concealment has been associated with lower PrEP use.8 MSM and TGN people with higher IH and sexual orientation concealment may be more isolated from SGM communities, restricting access to safer sex resources.9 In addition, minority stress has been associated with psychological distress, which may lead to less self-care (e.g., PrEP and/or condom use).9

Discrimination has also been associated with frequency of condomless sex and sex with an HIV+ or unknown status partner among MSM.10,11 Longitudinal studies have found that higher IH was associated with more condomless anal sex (CAS) partners12,13; however, a meta-analysis of IH and CAS among MSM found only a small effect.14 Although race/ethnicity was not a moderator in these studies, the strength of this association may vary across racial/ethnic groups. Previous studies have shown that MSM of color report higher levels of heterosexist discrimination than White MSM,15 and these minority stressors have been more strongly associated with CAS among MSM of color than among White MSM.15,16 MSM and TGN POC may experience heterosexism both outside of and within their racial/ethnic communities, which may explain higher sexual orientation concealment.17,18

For POC, one's racial/ethnic community represents a crucial source of support, particularly to buffer against experiences of racism.19 Experiencing heterosexism, particularly from within one's own racial/ethnic community, may lead to conflicts in allegiances, defined as anxiety stemming from a desire for racial/ethnic and sexual minority identities to remain separate.20 Identity conflict among SGM POC has been associated with experiences of heterosexist discrimination, IH, depression, and anxiety.21–23

However, no study has investigated identity conflict as a mediator of associations of minority stress and HIV outcomes. Conflict between one's racial/ethnic and sexual minority identities could act as a mechanism whereby stigma has detrimental impacts on PrEP and condom use by further isolating MSM and TGN POC from SGM communities, where there is a concentration of HIV prevention services, and by diminishing self-care due to higher distress.

Understanding identity conflict, a unique form of stigma based on simultaneously possessing multiple and interlocking marginalized identities, as a potential risk factor for HIV among MSM and TGN POC can inform culturally tailored HIV risk reduction interventions.

This study investigated identity conflict as a mechanism linking minority stress to HIV-related outcomes. We hypothesized that experiencing greater minority stress would be associated with more identity conflict 6 months later, which would in turn be associated with more adverse HIV-related outcomes 1 year later. These hypotheses were tested using longitudinal mediation of minority stress (i.e., sexual orientation microaggressions, IH, and sexual orientation concealment) at Time 1, and HIV-related outcomes (i.e., current PrEP use and number of CAS partners) at Time 3, by identity conflict at Time 2, among MSM and TGN POC.

Methods

Data were collected as a part of RADAR, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of HIV and substance use among young SGM-AMAB individuals in the Chicago, Illinois, area (current N = 1160). Eligibility criteria at original cohort enrollment were: 16–29 years old, AMAB, English-speaking, and had sex with a man in the past year or identified with an SGM label. Participants were included in the analytic sample if their race/ethnicity was anything other than Non-Hispanic White and completed the Conflict in Allegiances scale. Previous publications provide detailed information about study recruitment.24,25 In brief, participants were recruited in several ways: in-person and online recruitment; participants from previous cohort studies were enrolled; and serious partners and peers of enrolled participants were invited.

Data were collected every 6 months, and this study used data from three assessments: Time 1 (September 2018 to November 2019), Time 2 (June 2019 to March 2020), and Time 3 (August 2019 to February 2021). Informed consent was obtained from all participants with a waiver of parental permission for participants younger than 18 years and all study procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics

Participants completed measures of age, race/ethnicity (first asked to report if they are Hispanic/Latinx and then asked their race with response options: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, or Other), sexual orientation (response options: gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, unsure/questioning, straight/heterosexual, pansexual, asexual, and not listed), and gender identity (response options: male, female, transgender, gender nonconforming, gender queer, nonbinary, and not listed).

Sexual orientation microaggressions

We administered 9 items from the 19-item Sexual Orientation Microaggressions Inventory to assess more covert or subtle acts of aggression toward sexual minority individuals.26 Participants are instructed to report how often in the past 6 months they have had each experience (e.g., “You heard someone say ‘that's so gay’ in a negative way”). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (about every day). Items are averaged into a single score, with higher scores indicating a greater frequency of sexual orientation microaggressions (α = 0.90).

Internalized heterosexism

We assessed IH using 8 items from a 22-item adapted and validated scale.27 Participants used a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) to rate their agreement with each statement (e.g., “Sometimes I think that if I were straight, I would probably be happier”). Items are averaged into a single score, with a higher score indicating a higher level of IH (α = 0.88).

Sexual orientation concealment

We measured sexual orientation concealment using a single item: “How out are you to the people around you?” Participants responded on a scale of 0 (not out to anyone) to 3 (out to everyone). Scores were reverse coded to range from less concealment to more concealment.

Identity conflict

Conflict between one's racial/ethnic identity and sexual orientation identity was measured using the 6-item Conflicts in Allegiances Scale.23 Participants were asked how much they agreed with each statement (e.g., “I have not yet found a way to integrate being [sexual orientation] with being a member of my cultural group”) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants' self-reported sexual orientation was piped in to each item. Items are averaged into a single score, with high scores indicating greater identity conflict (α = 0.74).

HIV-related outcomes

Participants were asked if they are currently using PrEP. Response options were “no” (0) and “yes” (1). The number of CAS partners in the last 6 months was measured using the HIV Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP).28 For this study, we winsorized the number of CAS partners at three standard deviations from the mean to prevent outliers and unrealistic values (range: 0–7).

Statistical analyses

Structural equation modeling in MPlus was used to model direct and indirect effects of minority stress variables on HIV-related outcomes through identity conflict. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to address missingness. For the PrEP use outcome, participants were excluded from analyses if they were HIV positive at any of the included time points (excluded N = 73 and analytic N = 264; 0.5% missingness across the dataset for primary predictors and outcome). For number of CAS partners, participants were excluded if they reported zero sexual partners at Time 3 (excluded N = 64 and analytic N = 273; 0.3% missingness across the dataset for primary predictors and outcome).

We used a bootstrap approach to calculate estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effect of minority stress on HIV-related outcomes through identity conflict.29 Separate models were run for each minority stress variable and each outcome. For the binary outcome of PrEP use, a logistical link function was used, whereas for the number of CAS partners, a count outcome, our models incorporated a negative binomial distribution. All models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. The model for CAS partners also controlled for HIV status. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the CAS partners outcome to see if results changed when current PrEP use among participants who were not living with HIV and undetectable viral load among participants living with HIV were controlled for at Time 3.

Results

Participants were 337 MSM and TGN POC. Sample characteristics are described in Table 1. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are shown in Table 2. IH was positively correlated with sexual orientation concealment, sexual orientation microaggressions, identity conflict, and PrEP use. Sexual orientation concealment was positively correlated with identity conflict. Identity conflict was positively correlated with microaggressions and number of CAS partners.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Mean ± SD or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 24.31 (3.04) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 134 (39.8) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 157 (46.6) |

| Multiracial | 29 (8.6) |

| Other | 17 (5.0) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 245 (72.7) |

| Bisexual | 54 (16.0) |

| Queer | 25 (7.4) |

| Other | 13 (3.9) |

| Gender identity | |

| Cisgender | 314 (93.2) |

| Transgender/gender nonbinary | 23 (6.8) |

| PrEP use | 51 (19.3)a |

Out of 264 HIV− participants. Total sample size N = 337.

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations of Predictor, Mediator, and Outcome Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalized heterosexism (Time 1) | — | |||||

| 2. SO concealment (Time 1) | 0.29*** | — | ||||

| 3. SO microaggressions (Time 1) | 0.25*** | 0.10 | — | |||

| 4. Identity conflict (Time 2) | 0.29*** | 0.21*** | 0.14* | — | ||

| 5. PrEP use (Time 3) | 0.14* | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | — | |

| 6. CAS partners (Time 3) | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.13* | 0.23** | — |

| Mean ± SD | ||||||

| Full sample | 1.47 (0.60) | 0.50 (0.75) | 1.71 (0.74) | 2.94 (1.20) | 0.25 (0.44) | 1.25 (1.07) |

| Black/African American | 1.46 (0.63) | 0.48 (0.73) | 1.81 (0.76) | 3.02 (1.06) | 0.22 (0.41) | 1.02 (1.05) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1.41 (0.53) | 0.46 (0.73) | 1.61 (0.69) | 2.76 (1.30) | 0.24 (0.43) | 1.41 (1.09) |

| Multiracial | 1.72 (0.72) | 0.69 (0.85) | 1.92 (0.87) | 3.06 (0.92) | 0.41 (0.50) | 1.46 (1.02) |

| Other | 1.71 (0.61) | 0.71 (0.85) | 1.62 (0.75) | 3.75 (1.35) | 0.31 (0.48) | 1.23 (0.83) |

| Possible range | 1–4 | 0–3 | 1–5 | 1–7 | 0–1 | 0–7 |

Point-biserial correlations reported for PrEP use; Pearson correlations reported for all other variables. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

CAS, condomless anal sex; SO, sexual orientation.

PrEP use

Results for path analyses are presented in Table 3. There was a significant association between IH at Time 1 and identity conflict at Time 2. Participants who reported more IH experienced more identity conflict at the 6-month follow-up. The associations between identity conflict at Time 2 and PrEP use at Time 3 and between IH at Time 1 and PrEP Use at Time 3 were not significant. We did not find a significant indirect effect from IH to PrEP use through identity conflict.

Table 3.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Minority Stress Variables on HIV-Related Outcomes Through Identity Conflict

| Identity conflict (Time 2) |

PrEP use (Time 3) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | 95% CI |

β (SE) | p | 95% CI |

|||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Internalized heterosexism (Time 1) | 0.64 (0.14) | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.14 (0.31) | 0.638 | −0.36 | 0.62 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) | — | — | — | — | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.472 | −0.14 | 0.33 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Internalized heterosexism through identity conflict | — | — | — | — | 0.07 (0.10) | 0.499 | −0.08 | 0.24 |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation concealment (Time 1) | 0.40 (0.09) | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.56 | −0.08 (0.27) | 0.766 | −0.7 | 0.24 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) | — | — | — | — | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.302 | −0.08 | 0.34 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation concealment through identity conflict | — | — | — | — | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.321 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation microaggressions (Time 1) | 0.25 (0.12) | 0.035 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.09 (0.22) | 0.689 | −0.28 | 0.43 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) | — | — | — | — | 0.12 (0.14) | 0.392 | −0.13 | 0.33 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation microaggressions through identity conflict | — | — | — | — | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.457 | −0.02 | 0.11 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) | CAS partners (Time 3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects |

|

|

||||||

| Internalized heterosexism (Time 1) |

0.57 (0.13) |

<0.001 |

0.35 |

0.77 |

−0.03 (0.09) |

0.745 |

−0.18 |

0.11 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.11 (0.05) |

0.018 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Internalized heterosexism through identity conflict |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.06 (0.03) |

0.045 |

0.02 |

0.12 |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation concealment (Time 1) |

0.33 (0.09) |

<0.001 |

0.18 |

0.47 |

−0.05 (0.07) |

0.431 |

−0.14 |

0.06 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.11 (0.04) |

0.008 |

0.03 |

0.19 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation concealment through identity conflict |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.04 (0.02) |

0.025 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation microaggressions (Time 1) |

0.17 (0.10) |

0.091 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

−0.03 (0.06) |

0.618 |

−0.14 |

0.06 |

| Identity conflict (Time 2) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.11 (0.04) |

0.014 |

0.04 |

0.18 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||

| Sexual orientation microaggressions through identity conflict | — | — | — | — | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.164 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

All analyses controlled for age, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender identity.

CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Concealment at Time 1 was significantly associated with identity conflict at Time 2. Participants who engaged in more concealment reported more identity conflict at the 6-month follow-up. There were no significant associations between identity conflict at Time 2 and PrEP use at Time 3 or concealment at Time 1 and PrEP use at Time 3. The indirect effect was not significant.

Microaggressions at Time 1 were significantly associated with identity conflict at Time 2. Participants who experienced more microaggressions also reported experiencing more identity conflict at the 6-month follow-up. Microaggressions were not significantly associated with PrEP use and there was no significant indirect effect from microaggressions to PrEP use through identity conflict.

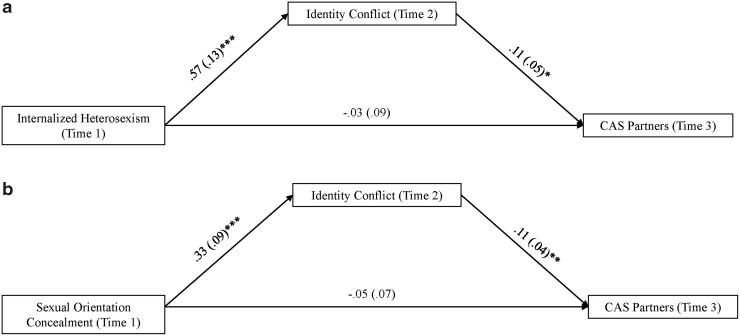

CAS partners

Path models for number of CAS partners are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. The association between identity conflict at Time 2 and number of CAS partners at Time 3 was significant. Participants who experienced more identity conflict reported more CAS partners 6 months later. The direct association between IH at Time 1 and CAS partners at Time 3 was not significant. However, the indirect association of IH at Time 1 on CAS partners at Time 3 through identity conflict at Time 2 was significant. The indirect effect suggests that participants who experienced more IH had more identity conflict 6 months later, which was associated with more CAS partners 1 year later.

FIG. 1.

(a) The model above displays the results of the mediation analysis. Indirect: internalized heterosexism on CAS partners (through identity conflict): β = 0.06, SE = 0.03, p = 0.045, 95% CI = 0.02–0.12. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (b) The model above displays the results of the mediation analysis. Indirect: Sexual orientation concealment on CAS partners (through identity conflict): β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.025, 95% CI = 0.02–0.07. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. CAS, condomless anal sex; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

The association between sexual orientation concealment at Time 1 and identity conflict at Time 2 was significant, such that participants who were less out experienced more identity conflict 6 months later. The direct association between concealment at Time 1 and CAS partners at Time 3 was not significant. The indirect association between concealment at Time 1 and CAS partners at Time 3 mediated by identity conflict at Time 2 was significant. Participants who had higher concealment reported more identity conflict 6 months later, which was associated with more CAS partners 1 year later.

Microaggressions at Time 1 were not significantly associated with identity conflict at Time 2 or number of CAS partners at Time 3. The indirect effect from Time 1 microaggressions to Time 3 CAS partners through Time 2 identity conflict was not significant.

We ran sensitivity analyses controlling for current PrEP use and undetectable viral load in analyses with CAS partners as the outcome. We found no change in results, except for the indirect effect of IH on number of CAS partners through identity conflict (β = 0.07, SE = 0.04, p = 0.055, 95% CI = 0.03–0.15), which became nonsignificant. This change is likely due to a decrease in power (analyses excluded 62 participants who did not have viral load data at Time 3). Although we were underpowered to conduct analyses separately for cisgender men and gender minority groups, we ran post hoc sensitivity analyses, excluding gender minority participants, and found the same pattern of results (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between identity conflict and HIV-related outcomes among MSM and TGN POC. We did not find significant direct associations between minority stressors at Time 1 and HIV-related outcomes at Time 3. Previous research has identified direct associations of minority stressors with condom10–13 and PrEP use,7 although some have found evidence for a small effect size.14 However, many of these previous studies were cross-sectional, while this analysis utilized longitudinal data with a 12-month interval. The association between minority stressors and HIV-related outcomes may attenuate over time. The lack of associations with PrEP use may also have been due to the low rate of PrEP use in our sample (19.3% of HIV-participants), consistent with research showing significant racial/ethnic disparities in PrEP use.30

We found partial support for our mediation hypothesis. IH and sexual orientation concealment were indirectly associated with the number of CAS partners through identity conflict; however, these predictors were not indirectly associated with PrEP use, and no significant indirect effect was found for microaggressions and HIV-related outcomes through identity conflict. Of note, these associations represented proximal stressors, in contrast to the nonsignificant associations for distal stressors. This is consistent with minority stress theory, which dictates that proximal stressors are most detrimental.5 Previous research has shown that IH and sexual identity concealment were positively associated with identity conflict.22,23 However, this is the first study to provide evidence of identity conflict as a mechanism, whereby minority stress processes are indirectly associated with more CAS partners.

IH and sexual orientation concealment may contribute to identity conflict and increase CAS in a few ways. First, condom use may be impacted by diminished access to partners and an amplified sense of isolation from SGM communities, driven by identity conflict. Individuals who experience diminished access to partners may have lower self-efficacy for condom negotiation or be influenced to have condomless sex when sexual partners are perceived to be scarce. For example, loneliness has been identified as a factor in MSM motivation to have CAS31 and has been associated with CAS among rural MSM.32

Second, individuals who conceal their sexual orientation and experience identity conflict may not access targeted sexual health resources. For example, there are documented differences in clinician-patient communication when an individual does not disclose SGM identity such that individuals who do not disclose often do not receive appropriately targeted messaging.33 Third, self-efficacy in condom negotiation may be impacted by diminished self-care as a consequence of distress caused by identity conflict.

Indeed, IH has been linked to CAS through condom negotiation self-efficacy in previous research34; however, this study did not include measures of intersectional stigma. These findings provide a foundation for further examination of these potential pathways.

Limitations

Results of this study should be considered with some limitations. First, the sample was drawn exclusively from the Chicago area, limiting generalization to other contexts (e.g., less urban areas, areas with fewer SGM resources). Second, we were unable to consider stigma based on race/ethnicity, gender identity, or intersectional discrimination unique to SGM POC (e.g., related to simultaneously possessing racial/ethnic, sexual, and gender minority identities). Future studies should examine these forms of stigma in relation to identity conflict, CAS, and PrEP outcomes. Third, due to the small number of gender minority participants, we were underpowered to conduct separate structural equation models looking only at these participants. Future research is needed to fully capture the stigma experiences of gender minority POC.

Fourth, the sample size and the 12-month interval between time points may have impacted detection of effects that may attenuate over time. Future studies should consider assessing these relationships with briefer intervals. Fifth, we were unable to test cross-lagged mediation models because we did not have measures for every variable at every time point, which reduces our capacity to make inferences about causal relationships. Finally, the findings regarding PrEP may be impacted by the small sample size of PrEP users as well as measurement of PrEP outcomes. Future studies may examine different PrEP outcomes across the continuum (e.g., awareness, intention, adherence, or discontinuation) or other factors that may be salient in this population (e.g., socioeconomic status, insurance status).

Conclusion

This study is among the first to establish a relationship between identity conflict and CAS among MSM and TGN POC. More must be done to address the needs of MSM and TGN POC, who are substantially overrepresented among new HIV infections.1,2 Our findings underline the need for the consideration of unique factors, including identity conflict, in the development of HIV prevention interventions among SGM POC.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

E.L.S.: conceptualization (lead); writing—original draft (equal); and writing—review and editing (equal). G.S.: formal analysis (lead) and writing—original draft (equal). C.D.X.H.: conceptualization (supporting); writing—original draft (equal) and writing—review and editing (equal). M.E.N.: methodology (equal); investigation (equal); and writing—review and editing (equal). B.M.: methodology (equal); investigation (equal); and writing—review and editing (equal).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036939).

Supplementary Material

Throughout the article, the term MSM and TGN will be used when referring to populations that include MSM and transgender women and nonbinary people AMAB. When referring to populations or samples from previous studies that include only cisgender MSM, the term MSM will be used.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2018 (Updated). 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf Accessed September 15, 2021.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among transgender women—National HIV behavioral surveillance, 7 U.S. cities, 2019–2020. 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-special-report-number-27.pdf Accessed October 1, 2021.

- 3. Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, et al. : Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morgan E, Ryan DT, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: High rate of discontinuation may diminish PrEP coverage among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3645–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. : Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol 2007;62:271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meanley S, Chandler C, Jaiswal J, et al. : Are sexual minority stressors associated with young men who have sex with men's (YMSM) level of engagement in PrEP? Behav Med 2021;43:225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moskowitz DA, Moran KO, Matson M, et al. : The PrEP cascade in a national cohort of adolescent men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021;86:536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williamson IR: Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Educ Res 2000;15:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rogers AH, Jardin C, Mayorga NA, et al. : The relationship of discrimination related to sexual orientation and HIV-relevant risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. Psychiatry Res 2018;267:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Hess KL, et al. : Association between enacted stigma and HIV-related risk behavior among MSM, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 2011. AIDS Behav 2017;21:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ: Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychol 2008;27:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Garofalo R, Mustanski B: Examining the conditions under which internalized homophobia is associated with substance use and condomless sex in young MSM: The moderating role of impulsivity. Ann Behav Med 2017;51:567–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: Moderators of the relationship between internalized homophobia and risky sexual behavior in men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav 2011;40:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE, Golub SA, Parsons JT: Race-based differentials in the impact of mental health and stigma on HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. Health Psychol 2015;34:847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jeffries WL, Marks G, Lauby J, et al. : Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1442–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennamer JD, Honnold J, Bradford J, Hendricks M: Differences in disclosure of sexuality among African American and White gay/bisexual men: Implications for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Educ Prev 2000;12:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gattamorta K, Quidley-Rodriguez N: Coming out experiences of Hispanic sexual minority young adults in South Florida. J Homosex 2018;65:741–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bowleg L, Burkholder G, Teti M, Craig ML: The complexities of outness: Psychosocial predictors of coming out to others among Black lesbian and bisexual women. J LGBT Health Res 2008;4:153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morales ES: Ethnic minority families and minority gays and lesbians. Marriage Fam Rev 1989;14:217–239. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santos CE, VanDaalen RA: The associations of sexual and ethnic–racial identity commitment, conflicts in allegiances, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual racial and ethnic minority adults. J Couns Psychol 2016;63:668–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sarno EL, Swann G, Newcomb ME, Whitton S: Intersectional minority stress and identity conflict among sexual and gender minority people of color assigned female at birth. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2021;27:408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sarno EL, Mohr JJ, Jackson SD, Fassinger RE: When identities collide: Conflicts in allegiances among LGB people of color. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2015;21:550–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Hayford C, et al. : Geographic and individual associations with PrEP stigma: Results from the RADAR cohort of diverse young men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3044–3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swann G, Newcomb ME, Crosby S, et al. : Historical and developmental changes in condom use among young men who have sex with men using a multiple-cohort, accelerated longitudinal design. Arch Sex Behav 2019;48:1099–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Swann G, Minshew R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: Validation of the sexual orientation microaggression inventory in two diverse samples of LGBTQ youth. Arch Sex Behav 2016;45:1289–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, et al. : Internalized homophobia and perceived stigma: A validation study of stigma measures in a sample of young men who have sex with men. Sex Res Social Policy 2017;14:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swann G, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: Validation of the HIV Risk Assessment of Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP): Comparison to a 2-month prospective diary study. Arch Sex Behav 2018;47:121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, Russell DW: Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kanny D, Jeffries WLT, Chapin-Bardales J, et al. : Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men—23 urban areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:801–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bauermeister JA, Carballo-Diéguez A, Ventuneac A, Dolezal C: Assessing motivations to engage in intentional condomless anal intercourse in HIV risk contexts (“bareback sex”) among men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev 2009;21:156–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hubach RD, Dodge B, Li MJ, et al. : Loneliness, HIV-related stigma, and condom use among a predominantly rural sample of HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS Educ Prev 2015;27:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ: The same but different: Clinician–patient communication with gay and lesbian patients. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ross MW, Rosser BS, Neumaier ER, Team PC: The relationship of internalized homonegativity to unsafe sexual behavior in HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev 2008;20:547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.