Abstract

The genetic characterization of a 5.5-kb chromosomal region of Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 that contains lpsB, a gene required for the normal development of symbiosis with Medicago spp., is presented. The nucleotide sequence of this DNA fragment revealed the presence of six genes: greA and lpsB, transcribed in the forward direction; and lpsE, lpsD, lpsC, and lrp, transcribed in the reverse direction. Except for lpsB, none of the lps genes were relevant for nodulation and nitrogen fixation. Analysis of the transcriptional organization of lpsB showed that greA and lpsB are part of separate transcriptional units, which is in agreement with the finding of a DNA stretch homologous to a “nonnitrogen” promoter consensus sequence between greA and lpsB. The opposite orientation of lpsB with respect to its first downstream coding sequence, lpsE, indicated that the altered LPS and the defective symbiosis of lpsB mutants are both consequences of a primary nonpolar defect in a single gene. Global sequence comparisons revealed that the greA-lpsB and lrp genes of S. meliloti have a genetic organization similar to that of their homologous loci in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. In particular, high sequence similarity was found between the translation product of lpsB and a core-related biosynthetic mannosyltransferase of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae encoded by the lpcC gene. The functional relationship between these two genes was demonstrated in genetic complementation experiments in which the S. meliloti lpsB gene restored the wild-type LPS phenotype when introduced into lpcC mutants of R. leguminosarum. These results support the view that S. meliloti lpsB also encodes a mannosyltransferase that participates in the biosynthesis of the LPS core. Evidence is provided for the presence of other lpsB-homologous sequences in several members of the family Rhizobiaceae.

The infection of legume roots by soil bacteria of the genera Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, and Sinorhizobium results in the development of specialized root organs, the nitrogen-fixing nodules (53). The establishment of functional root nodules is the result of a complex process that involves an active signal exchange between the host roots and the infecting rhizobia (7). One of the earliest events in the symbiotic dialog involves the secretion of flavonoid compounds by the host plant and the subsequent production of nodulation (Nod) factors by the rhizobia (38). Although the Nod factors are the best-characterized signal molecules of rhizobia, independent evidence supports the view that some of the bacterial surface polysaccharides are also active in signaling the plant (2, 16, 19, 22, 39, 40, 57, 60). It has thus been shown that the pretreatment of alfalfa roots with specific fractions of Sinorhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharides (EPS) conferred on symbiosis-deficient EPS mutants the ability to develop nitrogen-fixing nodules at a significant rate (2, 22, 57, 60). This and similar results for other plant-rhizobium associations (19) indicate that the EPSs induce durable changes in the plant root that are essential for symbiosis. That the active S. meliloti EPS can be partially replaced by certain molecular forms of a capsular polysaccharide (KPS) suggested that these two S. meliloti polysaccharides have similar modes of action in symbiosis (45, 50). It was recently reported, however, that there are differences in the efficiencies of nodule invasion mediated by the succinoglycan (EPSI), the galactoglucan (EPSII), and the KPS (43). Interestingly, KPS has genetic loci in common with the biosynthetic pathway of another surface polysaccharide, the outer membrane lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (11, 31). Nevertheless, no symbiotic relationships between the S. meliloti KPS or EPS and the LPS have been demonstrated. It is well known that in those S. meliloti strains with no symbiotically active KPS, the remaining unaltered LPS does not support wild-type nodulation in EPS mutants (30, 40). Further analysis will thus be required to elucidate the ultimate genetic and functional relationships among the bacterial surface polysaccharides involved in symbiosis.

The genetics and biochemistry of S. meliloti LPS have been little investigated (15) in comparison with the LPS of other rhizobia (42, 44, 55, 59), possibly in part because several S. meliloti LPS mutants were reported to have normal symbiosis with the host plant alfalfa (15). lpsB mutants, however, were found to be compromised in their competitiveness for nodulation in alfalfa (34) and displayed a Fix− phenotype in Medicago truncatula (41). At the moment, there is no simple model to explain the role of the S. meliloti LPS in symbiosis. The most passive role would be that of a surface molecule merely masking the presentation of naturally hidden bacterial structures that disturb plant penetration (i.e., preserving the bacterial surface charge or hydrophobicity [18]); a more active role for LPS in signaling the plant has yet to be considered (16). At this point, none of these possibilities can be excluded.

The altered symbiotic phenotype of S. meliloti lpsB mutants with respect to Medicago spp. implicates lpsB as an informative locus for investigating the genetics and biochemistry of the LPS structures that are required for supporting wild-type symbiosis. We present here the genetic analysis of a 5.5-kb chromosomal DNA fragment from S. meliloti that contains the lpsB gene. Based on sequence data and results from genetic complementation experiments, a putative function is proposed for the lpsB gene product. In addition, two new genes, lpsE and lpsD, that map immediately downstream from lpsB and participate in LPS biosynthesis have been identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains used and constructed for this work

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterim tumefaciens C58 | Wild type | A. G. Matthysse |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | Wild type, symbiont of Glycine max | P. van Berkum |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | recA1, ΔlacU169 80dlacZΔM15; host strain used in cloning experiments | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | Host strain of the nested-deletion clones generated by exonuclease III for DNA sequencing | Bullock et al. (10) |

| E. coli S17-1 | MM294, RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 chromosomally integrated | Simon et al. (54) |

| Mesorhizobium ciceri USDA 3383 | Wild type, symbiont of Cicer arietinum L. | P. van Berkum |

| M. tianshanense USDA 3592 | Wild type, symbiont of Glycirrhiza pallidiflora | P. van Berkum |

| Rhizobium etli CFN42, USDA 9032 | Wild type, symbiont of Phaseolus vulgaris | E. Martínez |

| R. galegae USDA 4128 | Wild type, symbiont of Galega orientalis | P. van Berkum |

| R. hainanensis USDA 3588 | Wild type, symbiont of Desmodium sinuatum | P. van Berkum |

| R. huatlense USDA 4900 | Wild type, symbiont of Sesbania herbaceae | P. van Berkum |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae VF39 | Wild type, symbiont of Pisum sativum | U. Priefer |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3855 | Wild type, symbiont of P. sativum, Smr derivative of wild-type strain 128C53 | C. Ronson (28) |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae RSKnH | R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3855 lpcC::nptII | C. Ronson (28) |

| R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii ANU843 | Wild type, symbiont of Trifolium spp. | P. van Berkum |

| R. mongolense USDA 1844 | Wild type, symbiont of Medicago ruthenica | P. van Berkum |

| Rhizobium sp. strain GRH2 | Wild type, isolated from Acacia cyanophylla, nodulates herbaceous legumes such as Phaseolus and Trifolium spp. | N. Toro |

| Rhizobium sp. strain LPU83 | Wild type, nodulates M. sativa, P. vulgaris, and Leucaena leucocephala, closely related to Rhizobium sp. strain Or191 | Del Papa et al. (17) |

| Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 | Wild type, isolated from root nodules of Lablab purpureus, nodulates several legumes | W. J. Broughton |

| Rhizobium sp. strain Or191 | Wild type, nodulates M. sativa, P. vulgaris, and L. leucocephala | P. van Berkum |

| R. tropici CIAT 299 (type 2A) | Wild type, symbiont of P. vulgaris | M. Aguilar |

| R. tropici CIAT 899 (type 2B), USDA 9030 | Wild type, symbiont of P. vulgaris | P. van Berkum |

| Sinorhizobium sp. strain BR816 | Wild type, symbiont of P. vulgaris | M. Aguilar |

| Sinorhizobium fredii HH103 | Wild type, symbiont of G. max | M. Megias |

| S. fredii USDA 191 | Wild type, symbiont of G. max | S. Pueppke |

| S. fredii USDA 257 | Wild type, symbiont of G. max | S. Pueppke |

| S. medicae USDA 1037 | Wild type, symbiont of M. sativa | P. van Berkum |

| S. meliloti 2011 | Symbiont of M. sativa, Smr derivative of strain SU-47 | Casse et al. (12) |

| S. meliloti 6963 | S. meliloti 2011 lpsB::Tn5-6963 Nmr Smr | Lagares et al. (34) |

| S. meliloti 7555 | S. meliloti SU47 lpsC::Tn5 Nmr Smr | Clover et al. (15) |

| S. meliloti 20-B+ | S. meliloti 2011 lpsB::lacZ-Gm (sense lacZ fusion at KpnI site in lpsB) Smr Gmr | This work |

| S. meliloti 20-B | S. meliloti 2011 lpsB::lacZ-Gm (antisense lacZ fusion at KpnI site in lpsB Smr Gmr | This work |

| S. meliloti 20-C | S. meliloti 2011 lpsC::pK18mob, lacZ promoter of vector reads downstream of interrupted coding sequence, Smr Nmr | This work |

| S. meliloti 20-D | S. meliloti 2011 lpsD::pK18mob, lacZ promoter of vector reads downstream of interrupted coding sequence, Smr Nmr | This work |

| S. meliloti 20-E | S. meliloti 2011 lpsE::pK18mob, lacZ promoter of vector reads downstream of interrupted coding sequence, Smr Nmr | This work |

| S. saheli USDA 4893 | Wild type, symbiont of Sesbania cannabina | P. van Berkum |

| S. teranga USDA 4894 | Wild type, symbiont of Sesbania laeta | P. van Berkum |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used and constructed for this work

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pA1 | pK18mob carrying an SsII-KpnI insert containing the complete greA gene and the 5′ end of the lpsB gene of S. meliloti 2011; coding sequences of the insert in sense orientation relative to the plac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pA2 | pK19mob carrying the same insert as in pA1; coding sequences of the insert in antisense orientation relative to plac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pAB2001 | Plasmid containing a promoterless lacZ-aacC1 cassette conferring Gmr | Becker et al. (5) |

| pAL100 | pACYC184-Gm-mob carrying in DraI a 5.5-kb SstI DNA fragment from S. meliloti 2011 that complements the LPS mutations in S. meliloti 6963 (blunt-end cloned as Ecl136II), Gmr | Niechaus et al. (41) |

| pAL101 | pSVB30/ΔB-H carrying in SstI the 5.5-kb SstI fragment from S. meliloti 2011 that complements S. meliloti 6963 | This work |

| pAL103A | pSVB30 carrying in SalI (Klenow) the 5.5-kb SstI fragment from pAL101 blunt-end cloned as Ecl136II; insert orientation with its HindIII site close to the lac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pAL103B | pSVB30 carrying in the SalI restriction site (Klenow) the 5.5-kb SstI fragment from pAL101 blunt-end cloned as Ecl136II; insert orientation opposite that in pAL103A | This work |

| pB1 | pK18mob carrying a BamHI-KpnI insert that contains the 3′ end of the greA gene and the 5′ portion of the lpsB gene of S. meliloti 2011; coding sequences of the insert in sense orientation relative to the lac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pB2 | pK19mob carrying the same insert as in pB1; coding sequences of the insert in antisense orientation relative to the lac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pC1 | pK18mob carrying an internal fragment of the lpsB gene that extends from a few codons downstream of the putative GTG start codon to the central KpnI site; coding sequences of the insert in sense orientation relative to the lac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pC2 | pK19mob carrying the same insert as in pC1; coding sequences of the insert in antisense orientation relative to the lac promoter from the vector | This work |

| pJB3Tc19 | Derivative of the minimal replicon of plasmid RK2, Apr Tcr | Blatny et al. (8) |

| pJBIpsSme | pJB3Tc19 carrying a 4.9-kb SstI-HindIII fragment containing the greA-lpsD region from S. meliloti 2011 cloned in the polylinker of the vector as EcoRI-HindIII, Kmr | This work |

| pJL200 | pSVB30 carrying in SstI an 11-kb SstI Tn5-containing fragment from S. meliloti 6963; insert homologous to that of pAL101 but carrying the Tn5 within lpsB | Niehaus et al. (41) |

| pJL200/ΔB-H | pSVB30/ΔB-H carrying in SstI the 11-kb SstI Tn5-containing fragment from S. meliloti 6963 | This work |

| pJL201 | pACYC184-Gm-mob carrying in DraI an 11-kb SstI Tn5-containing fragment from pJL200 blunt-end cloned as Ecl136II, Nmr Gmr; insert homologous to that of pAL100 but carrying the Tn5 within lpsB | Niehaus et al. (41) |

| pK18mob | pK18 derivative, mob, Kmr | Schäfer et al. (52) |

| pK19mob | pK19 derivative, mob, Kmr | Schäfer et al. (52) |

| pPN120 | pLAFR1 with a 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment containing greA, lpcC, dctA, and the 5′ region of dctB from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, Tcr | C. Ronson (28) |

| pSVB30 | pUC8 derivative, Apr | Arnold and Pühler (1) |

| pSVB30/ΔB-H | pSVB30 with a deletion in the BamHI-HindIII region of the polylinker | This work |

Culture media and bacterial growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (35) at 37°C. S. meliloti strains were grown in TY (6) or LB medium at 28°C. Antibiotics were added as required at the following concentrations (micrograms per milliliter): streptomycin (400) gentamicin (50) and neomycin (120) for S. meliloti; ampicillin (200), gentamicin (10), and kanamycin (50) for E. coli.

LPS preparations and SDS-PAGE.

LPS samples for electrophoretic analysis were purified by affinity chromatography as indicated by Valverde et al. (58), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described elsewhere (34), using a Mini-Protean II 2-D cell (Bio-Rad). Gels were fixed and silver stained as described by Reuhs et al. (47).

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA preparation, restriction enzyme analysis, cloning procedures, and E. coli transformation were performed according to established techniques (35). Southern hybridizations were carried out using DNA probes labeled with digoxigenin. The probes were synthesized by PCR using digoxigenin-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim) and appropriate primers to amplify the region of interest. For hybridizations, DNA extracted from bacteria was digested and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond N; Amersham) as described by Chomczynski (14). The digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes were hybridized to the membranes at 65°C overnight after the blocking of nonspecific binding sites 1 h at 68°C, using the solutions and experimental conditions specified by Boehringer Mannheim (catalog no. 1093 657). For the visualization of positive bands, the membranes were incubated with an antibody against the digoxigenin ligand and washed, and a final color reaction was initiated at alkaline pH by the addition of X-phosphate plus nitroblue tetrazolium chloride as specified by the manufacturer.

DNA sequencing.

The wild-type DNA fragment complementing S. meliloti 6963 was cloned into a modified pSVB30 vector in order to perform nested exonuclease III deletions as follows. First, plasmid pJL200/ΔB-H was generated by transferring the 11-kb SstI DNA fragment of S. meliloti 6963 from pJL200 to the SstI site of pSVB30/ΔB-H and then replaced the BamHI-HindIII portion containing the Tn5 insertion from this plasmid with the homologous wild-type BamHI-HindIII segment (devoid of the transposon) from pAL100 to produce plasmid pAL101 (Table 2). Finally, we generated plasmids pAL103A and pAL103B by removing the SstI insert from pAL101 with Ecl136II (isoschizomer of SstI producing blunt ends) and cloning the fragment into the filled-in SalI site of pSVB30 in forward and reverse orientations, respectively. Using these plasmids, appropriate subclones for sequencing were constructed by creating a set of overlapping nested deletions by the method of Henikoff (24). Sequencing reactions were carried out using universal and reverse primers and an Auto Read Sequencing kit (Pharmacia-LKB) according to a protocol devised by Zimmermann et al. (62). Sequence data were obtained for both DNA strands using an A.L.F. DNA sequencer (Pharmacia-LKB). Short gaps in the nucleotide sequence were resolved either by sequencing from the upstream region by means of specific primers or by reading from the pSVB30 vector toward different subcloned restriction fragments by means of standard M13 primers (Pharmacia). Sequence analysis and the determination of coding probabilities were done with programs from the Staden software package (56).

Vector-mediated chromosome walking.

An StuI-EcoRI restriction fragment containing the start codon and the upstream portion of lrp was obtained for DNA sequencing as described by Hozbor et al. (26). After excision of an internal region of the lrp from pAL101 with StuI-SacI, this segment was cloned into the suicide vector pK18mob (52) and then promoted the integration of this construction into the chromosome of S. meliloti 2011 by homologous recombination. After self-ligation of the EcoRI-digested total DNA from the resulting recombinant strain (neomycin and streptomycin resistant [Nmr Smr]), the reaction mixture containing the desired circularized fragment was transformed into E. coli DH5α. The sequence of the 5′ end of lrp was obtained by reading from the vector through the StuI site up to the first in-frame start codon (ATG).

Oligonucleotide primers and PCR hybridization conditions.

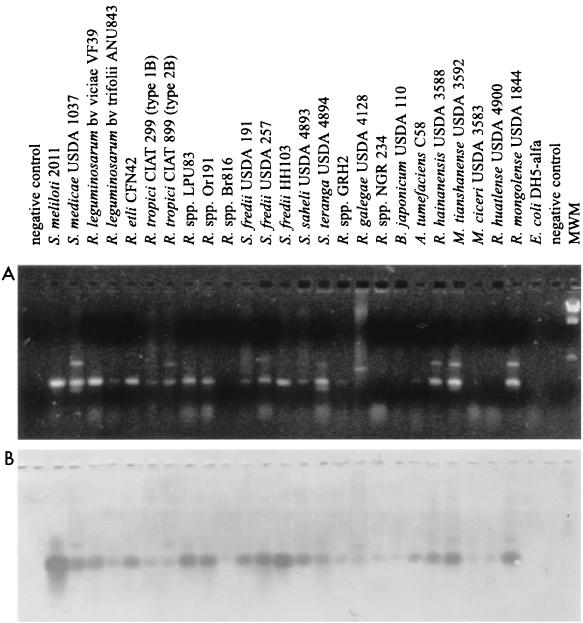

We designed deoxyoligonucleotide primers in order to amplify a 267-bp fragment of the S. meliloti lpsB and the Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae lpcC based on the sequence conservation of both genes (GenBank accession no. AAF06008 and AAC05215, respectively). These primers, synthesized by DNAgency (Malvern, Pa), had the sequences 5′-GTICGCCATCAGAAAGG-3′ (LPSB2F) and 5′-GAGCGGCGTCAGGCCGAAGC-3′ (LPSB2R). The PCRs were performed as described by Del Papa et al. (17). Stated in brief, PCR mixtures of 25 μl contained 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 500 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 U of Taq polymerase, each primer at 0.5 μM, and 5 to 10 μl of template DNA, obtained previously by heating a freshly isolated bacterial colony at 100°C for 15 min in 50 μl of distilled water. In some instances, appropriate dilutions of total DNA prepared from the bacteria by classical phenol-Tris extraction were used as the template. The amplification reactions were run in capillary tubes in an Idaho 1605 Air Thermo Cycler (ATC; Idaho Technology) under the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 1 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 15 s, 53°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s; and a final holding step at 72°C for 15 s. After the reaction, 10-μl volumes of the PCR products were separated on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels containing 0.5 to 1.0 μg of ethidium bromide per ml, and the resulting banding pattern was photographed using a Kodak model DC120 digital camera under UV illumination. Southern blot hybridization of the PCR products from Fig. 5B were carried out at 65°C, using a 532-bp digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe corresponding to an internal portion of lpsB whose total sequence included that of the PCR-amplified region.

FIG. 5.

PCR-hybridization analysis of lpsB-homologous sequences in various bacteria. (A) A PCR assay was carried out with primers LPSB2F and LPSB2R, designed according to the sequence conservation between S. meliloti lpsB and the homologous lpcC of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. PCR products were separated on 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels containing 0.5 to 1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and photographed with a Kodak DC120 digital camera under UV illumination. Strains are indicated above the lanes. MWM, molecular weight marker (lambda phage DNA digested with HindIII). (B) The PCR products from panel A were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization using a 532-bp digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe which is internal to lpsB and contains the amplified region.

Chromosomal single-copy lacZ transcriptional fusions and allelic exchange at the lps locus.

Single-copy chromosomal transcriptional fusions between a promotorless lacZ-accC1 cassette (5) and lpsB were effected through the homologous recombination in vivo of the insert from either pHL-B1 (sense fusion) or pHL-B2 (antisense fusion). All plasmids for the site-specific gene replacement were constructed using pK18mob as a suicide vector (52). Plasmids were transferred from E. coli S17-1 to S. meliloti 2011 by conjugation. S. meliloti clones that had presumably undergone the marker exchange were identified as the result of a double-crossover event by their expected gentamicin-resistant (Gmr; cassette accC1 gene), Smr (marker of the recipient bacteria), and Nms (after plasmid segregation) phenotype. Genomic structures of site-specific gene replacements were confirmed by Southern transfer analysis.

Analysis of lpsB transcriptional organization.

Different fragments of the greA-lpsB region were subcloned into the mobilizable suicide vectors pK18mob and pK19mob, and the hybrid plasmids were transferred to strain S. meliloti 20-B+ (Table 1). Integration of the hybrid plasmids into the genome of the S. meliloti by a single crossover was inferred on the basis of an acquisition of the vector-encoded antibiotic resistance. Transconjugants carrying different deletions upstream from the lpsB-lacZ transcriptional fusion were assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

Assay for β-galactosidase.

β-Galactosidase activity was measured by the o-nitrophenyl-d-galactopyranoside method as described by Miller (36) except that the cells were grown on TY medium and permeabilized with 50 μl of chloroform. Bacterial cultures in log phase of growth were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in culture medium, and the concentration of bacteria was adjusted depending on the enzyme activity for each strain. All values were expressed as averages of at least three independent determinations.

Nodulation tests.

Surface-sterilized seeds were germinated on water-agar (1.5%, wt/vol). Two-day-old seedlings were transferred to gamma-irradiated sterilized plastic growth pouches (Mega Minneapolis International, Minneapolis, Minn.) containing 10 ml of nitrogen-free Jensen mineral solution, pH 6.7 (27). Three days later, primary roots were inoculated with 106 rhizobia by dripping 100 μl of a bacterial suspension onto the root from the tip toward the base. The plants were cultured in a growth chamber at 22°C and a 16-h photoperiod. Four weeks after inoculation, the dry weight of the aereal part of plants inoculated with LPS mutants was compared with that of controls inoculated with the parental strain. The number of nodules per individual plant was examined before harvest.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data reported have been deposited in GenBank and assigned accession no. AF193023.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of the 5.5-kb DNA fragment that complemented lpsB mutations.

We have previously shown that the lpsB mutant S. meliloti 6963 carries a Tn5 insertion within the lpsB region (41) according to the complementation groups previously established by Clover et al. (15). A 5.5-kb SstI restriction fragment recovered from the wild-type strain 2011 of S. meliloti and delivered via the plasmid pAL100 (Table 2) was able to complement the mutation in S. meliloti 6963 that affected both its LPS structure and symbiotic capacity (34, 41). To elucidate the genetic structure of the lpsB complementation group (15), the 5.5-kb SstI DNA fragment that complements the mutant S. meliloti 6963 was sequenced. A computer-assisted analysis of codon usage resulted in the open reading frame (ORF) structures presented in Fig. 1B. We assigned lpsB to an ORF of 1,056 bp by sequencing the DNA region flanking the Tn5 insertion site within S. meliloti 6963. We inferred a putative GTG start codon for lpsB on the basis of a likely ribosome-binding site located 8 bp upstream from that triplet. The deduced gene product for LpsB corresponds to a polypeptide of 351 amino acids with a molecular mass of 38.6 kDa. We detected no hydrophobic segments that could form transmembrane helices within the protein. The complete predicted sequence for LpsB showed strong homology to the lpcC-encoded mannosyltransferase required for LPS core biosynthesis in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (accession no. AAC05215; BLAST identities = 195/348, 56%; positives = 240/348, 69%) (28). We also found moderate homology of the central region of lpsB (amino acid sequence identity of between 24 and 33%) to many glycosyltransferases related to the biosynthesis of LPSs and of other surface polysaccharides (i.e., the RfbU-related protein from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum [AAB84956], EpsG from Streptococcus thermophilus [U40830], the RfbU protein homolog from Methanococcus jannaschii [F64500], the RfaK α-1,2-N-acetylglucosamine transferase from Neisseria meningitidis [AAC44648], and the IcsA LPS glycosyltransferase from N. meningitidis [AAC45156]).

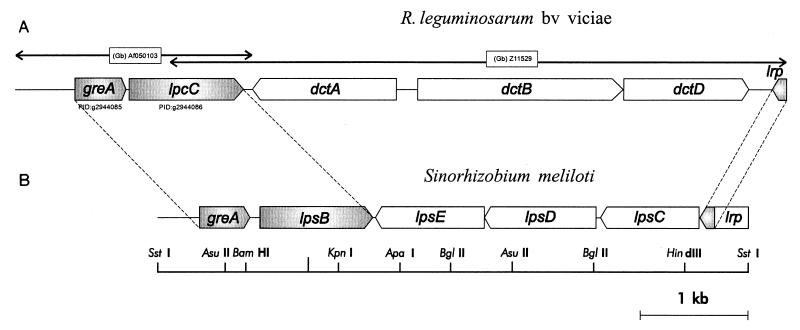

FIG. 1.

Genomic arrangement of greA, lpsB, and lrp in S. meliloti compared to the arrangement of homologous genes in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. (A) Gene arrangement in the vicinity of the lpcC gene in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (GenBank accession no. AF050103 and Z11529). (B) Gene arrangement within the 5.5-kb SstI fragment that contains the lpsB gene in S. meliloti 2011 (GenBank accession no. AF193023 [this work]). Shaded regions correspond to homologous coding sequences in both rhizobia.

A second putative ORF, of 477 bp and with high coding probability, was located 82 bp upstream from lpsB. Within the first 21 bp, this ORF contains two potential in-frame ATG start codons; between them, also in-frame, is a GTG codon. The two ATG are preceded by highly likely ribosome-binding sites. The first of these codons would give rise to a deduced amino acid sequence corresponding to a polypeptide of 158 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 17.5 kDa. We provisionally designated this ORF greA because the predicted translation product showed high homology to the GreA transcriptional factors from several organisms, including R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (AAC05214; here at 77% identity). A global sequence comparison among known GreA proteins indicated the presence of two consensus prokaryotic transcription elongation factor signatures, Prosite PS00829 and PS00830. Both of these sequence motifs are present in all GreA proteins, including the gene product from S. meliloti.

Downstream from lpsB and transcribed in the opposite direction, three complete ORFs were identified: lpsE (1,023 bp), lpsD (1,032 bp) (this work), and the previously defined lpsC (918 bp) (15) (Fig. 1A). Restriction enzyme analysis of a DNA fragment that complemented lpsB and lpsC mutants had previously shown that these two genes mapped 2 to 3 kb apart (15). Analysis of the DNA region flanking the Tn5 insertion in mutant S. meliloti 7555 (Table 1) allowed us to assign lpsC to the rightmost of the three sequential ORFs. The predicted translation product of the 918-bp lpsC (305 amino acids, 34.4 kDa) displays significant homology to the β-1, 4-glycosyltransferases from N. meningitidis (AAC44647; 25% sequence identity over 259 amino acids) and Aquifex aeolicus (AAC07593; 23% sequence identity over 254 amino acids). Mutations in this gene have been previously reported to lead to changes in LPS structure (15). The predicted translation products of lpsE (340 amino acids, 37.1 kDa) and lpsD (343 amino acids, 38.7 kDa) exhibit striking sequence resemblance to one another (53%). The 2-bp overlapping sequence (TG) between the ATG start codon of lpsE and the TGA termination codon of lpsD suggests the presence of a possible translational coupling between the two putative genes. Sequence comparison of the translation products of lpsE and lpsD against the nonredundant protein database from GenBank revealed several partial homologies to proteins involved in the biosynthesis of different bacterial polysaccharides. The higher scores corresponded to a capsular biosynthesis-related protein from A. aeolicus (AAC07522; 25% identity over 192 amino acids), to the CAPM protein from Rickettsia prowazekii (CAA14871) and to RfbU-related LPS biosynthetic enzymes from M. jannaschii (F64500) and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (AAB84679) (sequence identities of 21 and 33% over 143 and 293 amino acids, respectively).

Finally, upstream from lpsC and in the same coding direction, a truncated ORF homologous to the transcription factor gene lrp from several organisms was identified. The missing 5′ region of this lrp-like gene was obtained by cloning a portion of DNA lying upstream from the 5′ SstI site and extending to the next chromosomal EcoRI site by means of a vector-mediated chromosome-walking strategy (Materials and Methods). Partial sequencing of the recovered fragment showed that 18 bp separated the SstI site from a putative ATG start codon. Sequence analysis reveals the presence of a prokaryotic signature consensus characteristic of the transcription-regulatory proteins of the asnC subfamily (Prosite PS00519). Other lrp gene homologs that have been cloned in members of the family Rhizobiaceae, include those from Bradyrhizobium japonicum (AAB49303) (32), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (AAC43979) (13), and a more distant putative transcription factor from Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (P55658). Through sequence comparison we also found the 3′ end of an lrp gene homolog from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, located immediately downstream from the reported dctD gene (GenBank accession no. Z11529) (Fig. 1) (see below). The 44 amino acids of the C-terminal region of the Lrp protein corresponding to this identified DNA stretch exhibit a 75% sequence identity with the homologous product of S. meliloti 2011.

Results from our laboratory have shown that the 5.5-kb SstI fragment presented in Fig. 1 has a striking size conservation in all S. meliloti strains from different geographic origins thus far tested (not shown).

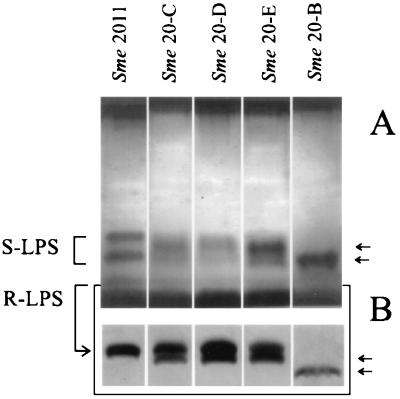

Construction and characterization of lpsD and lpsE mutants.

S. meliloti strains 20-C, 20-D, and 20-E, carrying nonpolar disruptions within lpsC, lpsD, and lpsE, respectively, were constructed by chromosome integration of the suicide plasmid pK18mob within their respective coding sequences. To avoid polar effects of the mutations, the lacZ promoter of the integrated vector pK18mob read downstream of the interrupted coding sequences (it is well known that the lacZ promoter is functional in S. meliloti [3, 4] [see Fig. 4]). All constructed mutants showed similar LPS phenotypes with a clear shift in their smooth LPS (S-LPS) component (Fig. 2A). In addition, a new rough LPS (R-LPS) component with high SDS-PAGE mobility was observed in the lpsC, lpsD, and lpsE mutants (Fig. 2B). The observed changes in the R-LPS patterns were all intermediate between the wild type and the lpsB mutant previously reported (Fig. 2B). The results indicate that the three genes are involved in LPS biosynthesis. Plant inoculation assays using M. sativa and M. truncatula showed that strains 20-C, 20-D, and 20-E have symbiotic phenotypes similar to that of the wild-type strain 2011, as evaluated through the number of root nodules and the plant dry weight 4 weeks postinoculation (not shown). Results presented here and previously (34, 41) implicate lpsB as the only S. meliloti LPS mutant affected in symbiosis.

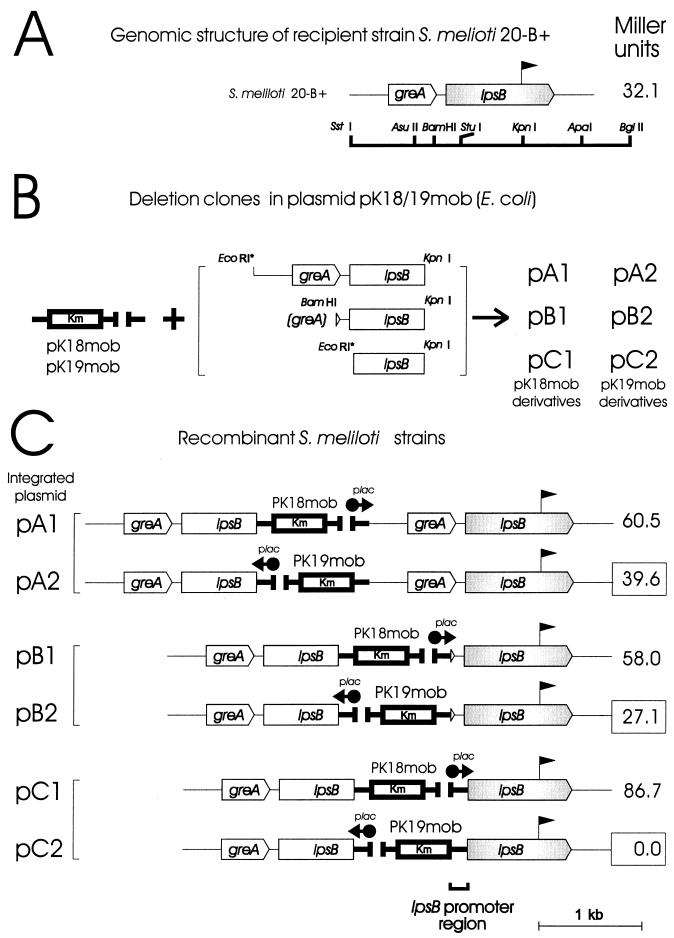

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of constructs used for transcriptional analysis of lpsB. (A) The promoterless lacZ-accC1 cassette (pennant symbol) was inserted in sense orientation in the KpnI site of the lpsB gene of S. meliloti 2011 to form S. meliloti 20-B+ (Table 1). The restriction map of lpsB and the flanking regions is shown below. (B) The three greA-lpsB deletion clones indicated on the right were subcloned between either the EcoRI (subclones A and C) or the BamHI (subclone B) site and the KpnI site within the polylinkers of the suicide plasmids pK18mob and pK19mob, shown on the left. Recombinant plasmids carrying the lacZ promoter in sense and antisense orientations relative to the inserts greA-lpsB were designated pA1-pB1-pC1 and pA2-pB2-pC2, respectively. (C) The plasmid constructs were integrated into the genome of S. meliloti 20-B+ via a single cross-over as described in Materials and Methods to produce the corresponding derivative strains indicated. The β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units) measured in each recombinant is shown to the right. The series 2 strains, having the lac promoter (plac) oriented in the reverse direction, are the experimentally informative ones in that the associated enzymatic activity reflects the functioning of any S. meliloti endogenous promoters upstream from the cassette. By contrast, those in series 1 constitute positive controls since significant β-galactosidase production would be expected under the direction of the lac promoter. Control strain S. meliloti 20-B, having the cassette in the reverse (antisense) direction, exhibited only negligible β-galactosidase activity (not shown).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of affinity-purified LPS extracted from S. meliloti 2011 and from mutant strains. Each well contained the total LPS extracted from about 10 mg (wet weight) of cells of the indicated bacterial strain, using EDTA and polymyxin B as described in Materials and Methods. (A) SDS-PAGE (18% polyacrylamide); (B) R-LPS components from a gel where increased resolution was achieved by extending the running time. The positions of LPS components that are present only in the mutants are indicated to the left. Genotypes of S. meliloti (Sme) strains 20-B, 20-E, 20-D, and 20-C are described in Table 1; Sme 2011 corresponds to the parental wild-type strain.

Similarities between the gene arrangement of greA-lpsB and lrp in S. meliloti and their homologous loci in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae.

Comparison of the nucleotide sequence corresponding to the 5.5-kb region presented in this work against the GenBank database revealed that three genes homologous to S. meliloti lpsB, greA, and lrp are present in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (GenBank accession no. AF050103 and Z11529). These genes are close to each other in both S. meliloti and R. leguminosarum (Fig. 1). The genes greA-lpsB are contiguous and transcribed in the same direction in S. meliloti, as is also the case with the homologous genes greA-lpcC in R. leguminosarum. Moreover, both species of rhizobia have the transcription factor gene lrp located comparably in orientation and distance with respect to greA within the bacterial chromosome. In S. meliloti, lrp maps 3 kb downstream from lpsB, on the opposite DNA strand. Likewise, in R. leguminosarum, lrp maps 5 kb downstream from lpcC, the lpsB homolog. Different genes, however, separate lpsB from lrp in S. meliloti and lpcC from lrp in R. leguminosarum. Whereas in S. meliloti there are three genes homologous to glycosyltransferase genes (see above) downstream from lpsB, in R. leguminosarum the dctA-dctBD cluster (dct, dicarboxylic acid transport) lies downstream from lpcC. By contrast, the homologous dct cluster in S. meliloti has been previously mapped outside the bacterial chromosome within the second symbiotic megaplasmid (61).

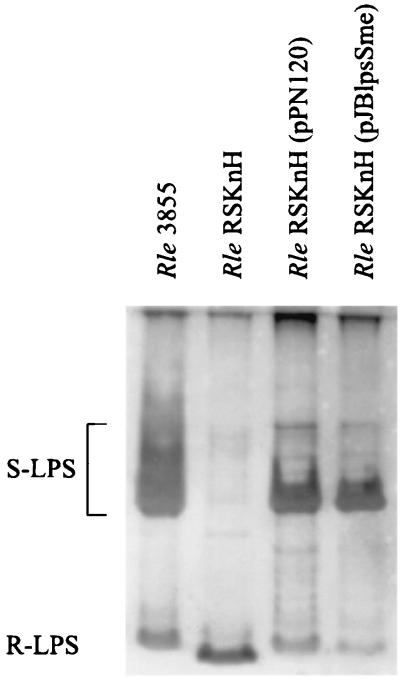

Genetic complementation of lpcC mutants by S. meliloti lpsB.

The striking nucleotide sequence similarity between lpsB and lpcC suggested that these genes could also have comparable sugar transferase activities. To evaluate this possibility, we carried out genetic complementation experiments in which the wild-type lpsB and lpcC genes were introduced into R. leguminosarum lpcC and S. meliloti lpsB mutants. Plasmids were introduced into the rhizobial strains by conjugation. Result presented in Fig. 3 show that when the plasmid-borne S. meliloti lpsB gene is introduced into the lpcC mutant of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strain RSKnH, the ability to synthesize complete LPS molecules is restored, resulting in an LPS pattern indistinguishable from that of the wild-type strain 3855 (positive complementation). In a reverse experiment, however, introduction of the R. leguminosarum lpcC gene into the S. meliloti lpsB mutant via the shuttle vector pPN120 did not restore the wild-type S. meliloti LPS (not shown). The presence of pPN120 and plasmid pJBlpsSme in the R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti transconjugants was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE (18% polyacrylamide) analysis showing the genetic complementation of an lpcC mutant of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (Rle) by the lpsB gene of S. meliloti. Lanes: Rle 3855, wild-type strain; Rle RSKnH, lpcC mutant; Rle RSKnH (pPN120), lpcC mutant carrying a plasmid copy of the wild-type lpcC gene; Rle RSKnH (pJBlpsSme), lpcC mutant carrying a plasmid copy of the wild-type lpsB gene of S. meliloti (Table 1). Each well contained the total LPS extracted from about 10 mg (wet weight) of cells of the indicated bacterial strain, using EDTA and polymyxin B as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of LPS components in the gel are indicated to the left.

Transcriptional organization of lpsB.

To investigate the transcriptional organization of lpsB, we integrated nonreplicative plasmids containing progressively 5′-deleted fragments from the greA-lpsB region into the genome of S. meliloti 20-B+ that carried a lpsB::lacZ transcriptional fusion (Fig. 4A and B). β-Galactosidase activities resulting from the lacZ transcriptional fusions occurring downstream from the integrated vector were analyzed (Fig. 4C). When the integrated plasmid contained at the 5′ end the 939 bp lying upstream from the putative lpsB start codon (plasmid pA2), the β-galactosidase activity of the resulting bacterial derivatives (39.6 Miller units) was similar to that exhibited by the recipient strain S. meliloti 20-B+ (32.1 Miller units). With the deleted fragments retaining at the 5′ end the 122 bp upstream from the start codon (plasmid pB2), a similar pattern of enzyme activity was observed (Fig. 4C). Higher activities were obtained with the recombinants carrying integrated plasmids having the lac promoter in sense orientation with respect to the lacZ cassette (plasmids pA1 and pB1). By contrast, the integration of plasmid pC2, carrying a deletion that included up to a small 5′ portion of the lpsB coding region, abolished the linked transcription of lpsB-lacZ. Nevertheless, plasmid pC1, containing the vector in the opposite orientation (the positive control), showed the high level of β-galactosidase expression expected for transcription initiated from the vector's upstream lac promoter. We thus conclude that a span of 122 bp upstream from the lpsB start codon is sufficient to direct transcription of the gene and very likely contains the lpsB promoter. Consistent with this possibility is the occurrence of a “nonnitrogen” promoter consensus sequence [TTPuANN 16–17 bases PuA(Pu)4 3–5 bases CA] (51) between greA and lpsB immediately upstream from the putative GTG start codon. The location of this consensus sequence gave us a preliminary indication that greA and lpsB might not be part of the same transcriptional unit. That there is moreover extremely low transcriptional activity of lpsB as a result of readthrough from the greA promoter is indicated by the small decrement in activity in the recombinant strain carrying plasmid pB2 compared to the control strain S. meliloti 20-B+. The use of S. meliloti 20-B+ to analyze the expression of lpsB in symbiosis showed that the gene is expressed at the root hair curling site, within the infection thread, and within the nodules in the central nitrogen-fixing tissue (not shown).

Presence of DNA sequences homologous to lpsB in several bacterial species of the family Rhizobiaceae.

We have previously suggested that alterations in LPS arising from lpsB mutations are likely to be associated with changes in the core region of the molecule (34). Core sugars and their linkages are frequently conserved among related bacteria, in contrast to the highly variable sugar structure of the O antigen. Having established that lpcC and lpsB are both core-related biosynthetic genes, we used a PCR-hybridization assay to test for the presence of similar sequences in several bacterial species of the family Rhizobiaceae (Fig. 5). The PCR primers were designed based on the sequence conservation between lpcC and lpsB (Materials and Methods). Positive amplification-hybridization corresponding to a PCR product of ca. 267 bp in length was obtained for Mezorhizobrum ciceri USDA 3383, Rhizobium etli CE3, R. galegae USDA 4128, R. hainensis USDA 3588, R. huatlense USDA 4900, R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii ANU843, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae VF39, Rhizobium sp. strains GRH2 (Acacia), LPU83, Or191, and NGR 234, R. mongolense USDA 1844, R. tianshanense USDA 3592, R. tropici CIAT 299, R. tropici CIAT 899, S. fredii 191, S. fredii 257, S. fredii HH103, S. medicae USDA 1037, S. meliloti 2011, S. saheli USDA 4893, S. teranga USDA 4894, A. tumefaciens C58, and B. japonicum USDA 110. The results suggest that lpsB-homologous genetic loci are most likely present in several species in the family Rhizobiaceae.

DISCUSSION

Previous results from our laboratories showed that lpsB mutants of S. meliloti 2011 exhibited an altered symbiotic capability when inoculated into different species of Medicago (34, 41). In this work we have characterized a 5.5-kb SstI DNA fragment which contains the S. meliloti lpsB chromosomal gene (15, 23, 33). In addition to lpsB, five other ORFs were identified, including one corresponding to the previously reported lpsC gene (15) and two others with sequence similarities to the regions coding for the transcription factors GreA and Lrp, respectively, found in several other gram-negative bacteria (9, 37). Immediately downstream of lpsB we have identified two new genes involved in LPS biosynthesis, lpsE and lpsD; these genes showed partial sequence similarities to bacterial sugar transferase genes, and their nonpolar interruption resulted in LPS modifications as visualized by SDS-PAGE. A previous report by Clover et al. (15) had shown that a Tn5 lpsC mutant was not altered in its symbiosis with alfalfa. We showed here that the disruption of neither lpsD nor lpsE affected symbiosis with M. sativa or M. truncatula. Current evidence indicates that lpsB is the only LPS-associated mutation leading to changes in symbiosis (34, 41). In addition, results presented in this work show that the transcription of lpsB appears to be under its own promoter, with little readthrough from the greA gene, and that the altered LPS and the defective symbiosis of lpsB mutants are both consequences of a primary nonpolar defect in a single gene.

A global sequence comparison of the 5.5-kb DNA region with the GenBank database revealed remarkable similarities between the gene arrangements of greA, lpsB, and lrp in S. meliloti and their homologous loci in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (chromosomal synteny). However, whereas in R. leguminosarum the dctA and dctBD genes were downstream from lrp, the unrelated genes lpsC, lpsD, and lpsE were found in S. meliloti. In the latter rhizobium, the dctA and dctBD genes had been previously mapped on the second symbiotic megaplasmid (61). Sequence analysis also showed that the predicted protein LpsB has a strong homology to the R. leguminosarum lpcC-encoded mannosyltransferase required for the LPS core biosynthesis (28, 29). That the two proteins exhibit striking amino acid sequence similarity suggested that they could also have comparable sugar transferase activities. Kadrmas et al. (28) previously reported, however, that membranes from S. meliloti when tested in glycosyltransferase assays in vitro possessed very little mannose transfer activity from the donor GDP-mannose to the acceptor Kdo2-lipid IVA (28). It is likely that the experimental conditions required to detect the core-associated mannosyltransferase activity in cell extracts of S. meliloti may not coincide with the optima established for R. leguminosarum. In fact, the genetic complementation experiment presented in this work revealed that S. meliloti lpsB restored the biosynthesis of complete LPS molecules when introduced into an (otherwise rough) lpcC mutant of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. This result strongly supports that the lpsB gene product is a core biosynthetic mannosyltransferase. It is worth noting that in a reverse-complementation experiment, the R. leguminosarum lpcC gene did not restore a wild-type LPS when introduced into an lpsB mutant of S. meliloti. One possible explanation for this observation is that lpcC is not properly expressed in the genetic background of S. meliloti. Alternatively, LpcC may have a stricter substrate specificity than LpsB. To gain further insight into this question, the enzyme activities of LpcC and LpsB should be analyzed in vitro as previously described (28), using homologous and heterologous core biosynthetic substrates.

Unfortunately, only one LPS structure has been elucidated in rhizobia (20, 21), and little information is available on conserved core sugars and their linkages among different Rhizobium species. The striking conservation of lpsB in all S. meliloti strains that we have tested suggests that mannose could be a ubiquitous component of the LPS core of these rhizobia. In addition, the detection of lpsB-related sequences in several members of the family Rhizobiaceae gives rise to the possibility that such sequences could also code for lpsB- or lpcC-related mannosyltransferases.

With respect to the lpsB mutants, there is the possibility that other surface polysaccharides could be affected. Other authors have shown that LPS and KPS have some biosynthetic reactions in common (11, 31). Nevertheless, several observations make it unlikely that KPS is affected in lpsB mutants. First, mannose is not present in the KPSs of the S. meliloti strains thus far analyzed (48) (the same is true for the EPSs [25, 46]). Second, results from our laboratory showed that lpsB mutants derived from S. meliloti 41 are sensitive to the KPS-dependent phage φ16-3. Both observations indicate that lpsB mutants have wild-type versions of this polysaccharide.

The principal questions remaining concern the mechanisms underlying the inability of the core-affected S. meliloti lpsB mutants to establish fully compatible associations with Medicago hosts. In most species of rhizobia, changes in symbiosis associated with LPS alterations occur after the loss or modification of the O antigen (18, 42, 44), topologically the outermost region of the molecule. However, this seems not to be the case for S. meliloti lpsB mutants that, being affected in symbiosis, still retain an O antigen linked to the altered core polysaccharide. Previous evidence has also shown that the LPS of S. meliloti has several unusual characteristics compared with LPSs from other bacteria. It has been observed, for example, that the R-LPS of S. meliloti is the major molecular form of the LPS (48). In addition, a strong immunodominance was associated with the R-LPS components (34, 49), a characteristic that in most other bacteria is associated with the O antigen. It is worth noting that lpsB mutants have lost most of the R-LPS immunoreactivity (34) that is present in the parental strain. However, no relationships have been established between specific epitopes and symbiosis. Studies in this direction are expected to be facilitated by the use of currently available anti-S. meliloti LPS core monoclonal antibodies (49).

Current data taken together implicate lpsB as the key locus for investigating the participation of S. meliloti LPS in symbioses with Medicago spp. Further experiments should be aimed at investigating whether the impaired symbiosis of lpsB mutants results from the loss of specific chemical groups that have to be sensed by the plant, or whether the plant phenotype is the consequence of secondary, as yet unidentified bacterial modifications that disturb plant penetration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants SECYT-PICT97 01-00032-00627 to A.L. and IFS-C/2672-1 to D.F.H. and partially by CICBA and CONICET (Argentina). We are greatly indebted to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Germany).

A.L. and D.F.H. are members of the Research Career of CONICET and CICBA (Argentina), respectively. A.J.L.P.O. was supported by CONICET.

We are grateful to Clive Ronson and Russell W. Carlson for providing rhizobial mutants and plasmids and to Donald F. Haggerty for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold W, Pühler A. A family of high-copy number plasmid vectors with single end-label sites for rapid nucleotide sequencing. Gene. 1988;70:171–179. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battisti L, Lara J C, Leigh J A. Specific oligosaccharide form of the Rhizobium melilotiexopolysaccharide promotes nodule invasion in alfalfa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5625–5629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker A, Kleickmann A, Arnold W, Keller M, Pühler A. Identification and analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti exoAMONP genes involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and mapping of promoters located on the exoHKLAMONPfragment. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:367–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00284690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker A, Kleickmann A, Küster H, Keller M, Arnold W, Pühler A. Analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti genes exoU, exoV, exoW, exoT, and exoI involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and nodule invasion: exoU and exoWprobably encode glucosyltransferases. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:735–744. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker A, Schmidt M, Jager W, Pühler A. New gentamicin-resistance and lacZpromoter-probe cassettes suitable for insertion mutagenesis and generation of transcriptional fusions. Gene. 1995;162:37–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00313-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beringer J E. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;84:188–198. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bladergroen M R, Spaink H P. Genes and signal molecules involved in the rhizobia-leguminoseae symbiosis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:353–359. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blatny J M, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen H C, Haugan K, Valla S. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:370–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.370-379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borukhov S, Polyakov A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. GreA protein: a transcription elongation factor from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8899–8902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullock W C, Fernandez J M, Short J M. XL1-Blue: a high efficient plasmid transforming recA Escherichia colistrain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell G R O, Reuhs B L, Walker G C. Different phenotypic classes of Sinorhizobium melilotimutants defective in synthesis of K antigen. J Bacteriol. 1999;180:5432–5436. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5432-5436.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casse F, Boucher C, Julliot J S, Michell M, Dénarié J. Identification and characterization of large plasmids in Rhizobium melilotiusing agarose gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1979;113:229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho K, Fuqua C, Martin B S, Winans S C. Identification of Agrobacterium tumefaciensgenes that direct the complete catabolism of octopine. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1872–1880. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1872-1880.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chomczynski P. One-hour downward alkaline capillary transfer for blotting of DNA and RNA. Anal Biochem. 1992;201:134–139. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90185-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clover R H, Kieber J, Signer E R. Lipopolysaccharide mutants of Rhizobium melilotiare not defective in symbiosis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3961–3967. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3961-3967.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dazzo F B, Truchet G L, Hollingsworth R I, Hrabak E M, Pankratz E M, Philip-Hollingsworth S, Salzwedel J L, Chapman K, Appenzeller L, Squartini A, Gerhold D, Orgambide G. Rhizobiumlipopolysaccharide modulates infection development in white clover root hairs. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5371–5384. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5371-5384.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Papa M F, Balagué L J, Castro Sowinski S, Wegener C, Segundo E, Martinez Abarca F, Toro N, Niehaus K, Pühler A, Aguilar O M, Martinez-Drets G, Lagares A. Isolation and characterization of alfalfa-nodulating rhizobia present in acidic soils of central Argentina and Uruguay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1420–1427. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1420-1427.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Maagd R A, Rao A S, Mulders I H M, Roo L G, van Loosdrecht M C M, Wijffelman C A, Lugtemberg B J J. Isolation and characterization of Rhizobium leguminosarumbv. viciae 248 with altered lipopolysaccharides: possible role of surface charge or hydrophobicity in bacterial release from the infection thread. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1143–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.1143-1150.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djordjevic S P, Chen H, Batley M, Redmond J W, Rolfe B G. Nitrogen fixation ability of exopolysaccharide synthesis mutants of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and Rhizobium trifoliiis restored by the addition of homologous exopolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:53–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.53-60.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsberg L S, Bhat U R, Carlson R W. Structural characterization of the O-antigenic polysaccharide of the lipopolysaccharide from Rhizobium etli strain CE3. A unique O-acetylated glycan of discrete size, containing 3-O-methyl-6-deoxy-l-talose and 2, 3, 4-tri-O-methyl-l-fucose. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18851–18863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forsberg L S, Carlson R W. The structures of the lipopolysaccharides from Rhizobium etlistrains CE358 and CE359. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2747–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez J E, Reuhs B L, Walker G C. Low molecular weight EPS II of Rhizobium meliloti allows nodule invasion in Medicago sativa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8636–8641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glazebrook J, Meiri G, Walker G C. Genetic mapping of symbiotic loci on the Rhizobium melilotichromosome. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1992;5:223–227. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-5-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III creates targeted breakpoints for DNA sequencing. Gene. 1984;28:351–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Her G-R, Glazebrook J, Walker G C, Reinhold V N. Structural studies of a novel exopolysaccharide produced by a mutant of Rhizobium melilotiRm1021. Carbohydr Res. 1990;198:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84300-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hozbor D, Pich Otero A J L, Wynne M E, Petruccelli S, Lagares A. Recovery of Tn5-flanking bacterial DNA by vector-mediated walking from the transposon to the host genome. Anal Biochem. 1998;259:286–288. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen H L. Nitrogen fixation in leguminous plants. I. General characters of root nodule bacteria isolated from species of Medicago and Trifoliumin Australia. Proc Linn Soc N S W. 1942;66:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadrmas J L, Allaway D, Studholme R E, Sullivan J T, Ronson C W, Poole P S, Raetz C R. Cloning and overexpression of glycosyltransferases that generate the lipopolysaccharide core of Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26432–26440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadrmas J L, Brozek K A, Raetz C R H. Lipopolysaccharide core glycosylation in Rhizobium leguminosarum. An unusual mannosyl transferase resembling the heptosyl transferase I of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32119–32125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kannenberg E L, Reuhs B L, Forsberg L S, Carlson R W. Lipopolysaccharides and K-antigens: their structures, biosynthesis, and functions. In: Spaink H P, Kondorosi A, Hooykas P J J, editors. The Rhizobiaceae, molecular biology of model plant-associated bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kereszt A, Kiss E, Reuhs B L, Carlson R W, Kondorosi A, Putnoky P. Novel rkp gene clusters of Sinorhizobium meliloti involved in capsular polysaccharide production and invasion of the symbiotic nodule: the rkpKgene encodes a UDP-glucose dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5426–5431. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5426-5431.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King N D, O'Brian M R. Identification of the lrp gene in Bradyrhizobium japonicumand its role in regulation of δ-aminolevulinic acid uptake J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:1828–1831. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1828-1831.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein S, Lohman K, Clover R, Walker G C, Signer E R. A directional, high-frequency chromosomal mobilization system for genetic mapping of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:324–326. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.324-326.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagares A, Caetano-Anollés G, Niehaus K, Lorenzen J, Ljunggren H D, Puhler A, Favelukes G. A Rhizobium melilotilipopolysaccharide mutant altered in competitiveness for nodulation of alfalfa. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5941–5952. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5941-5952.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman E B, Lin R. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein: a global regulator of gene expression in E. coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:747–775. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niebel A, Gressent F, Bono J J, Ranjeva R, Cullimore J. Recent advances in the study of Nod factor perception and signal transduction. Biochimie. 1999;81:669–674. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niehaus K, Albus U, Baier R, Schiene K, Schröder S, Pühler A. Symbiotic suppression of the Medicago sativa plant defense system by Rhizobium meliloti oligosaccharides. In: Elmerich C, Kondorosi A, Newton W E, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation for the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 225–226. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niehaus K, Becker A. The role of microbial surface polysaccharides in the Rhizobium-legume interaction. Subcell Biochem. 1998;29:73–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1707-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niehaus K, Lagares A, Pühler A. A Sinorhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharide mutant induces effective nodules on the host plant Medicago sativa (alfalfa) but fails to establish a symbiosis with Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:906–914. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noel K D, Vandenbosh K A, Kulpaca B. Mutations in Rhizobium phaseolithat lead to arrested development of infection threads. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1392–1401. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1392-1401.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pellock B J, Cheng H P, Walker G. Alfalfa root nodule invasion efficiency is dependent on Sinorhizobium melilotipolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4310-4318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Priefer U B. Genes involved in lipopolysaccharide production and symbiosis are clustered on the chromosome of Rhizobium leguminosarumbiovar viciae VF39. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6161–6168. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6161-6168.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Putnoki P, Petrovics G, Kereszt A, Gresskopf E, Ha D T C, Banfalvi Z, Kondorosi A. Rhizobium melilotilipopolysaccharide and exopolysaccharide can have the same function in the plant-bacterium interaction. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5450–5458. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5450-5458.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reinhold B B, Chan S Y, Reuber T L, Marra A, Walker G C, Reinhold V N. Detailed structural characterization of succinoglycan, the major exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium melilotiRm1021. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1997–2002. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1997-2002.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reuhs B L, Carlson R W, Kim J. Rhizobium fredii and Rhizobium meliloti produce 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid-containing polysaccharides that are structurally analogous to group II K antigens (capsular polysaccharides) found in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3570–3580. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3570-3580.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuhs B L, Geller D P, Kim J S, Fox J E, Kumar Kolli V S, Pueppke S G. Sinorhizobium fredii and Sinorhizobium melilotiproduce structurally conserved lipopolysaccharides and strain specific K antigens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4930–4938. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4930-4938.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reuhs B L, Stephens S B, Geller D P, Kim J S, Glenn J, Przytycki J, Oljanen-Reuhs T. Epitope identification for a panel of anti-Sinorhizobium melilotimonoclonal antibodies and application to the analysis of K antigens and lipopolysaccharides from bacteroids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5186–5191. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5186-5191.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reuhs B L, Williams M N, Kim J S, Carlson R W, Cote F. Suppression of the Fix-phenotype of Rhizobium meliloti exoB mutants by lpsZis correlated to a modified expression of the K polysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4289–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4289-4296.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronson C W, Astwood P M. Genes involved in the carbon metabolism of bacteriods. In: Evans H J, Bottomley P J, Newton W E, editors. Nitrogen fixation research progress. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1985. pp. 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene. 1994;145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultze M, Kondorosi A. Regulation of symbiotic root nodule development. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivogenetic engeneering:transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stacey G, So J-S, Roth L E, Lakshumi S K, Carlson R W. A lipopolysaccharide mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicumthat uncouples plant from bacterial differentiation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:332–340. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-4-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staden R. The current status and portability of our sequence handling software. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:217–231. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urzainqui A, Walker G C. Exogenous suppression of the symbiotic deficiencies of Rhizobium meliloti exomutants. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3403–3406. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3403-3406.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valverde C, Hozbor D F, Lagares A. Rapid preparation of affinity-purified lipopolysaccharide samples for electrophoretic analysis. BioTechniques. 1997;22:230–236. doi: 10.2144/97222bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinuesa P, Reuhs B L, Breton C, Werner D. Identification of a plasmid-borne locus in Rhizobium etli KIM5s involved in lipopolysaccharide O-chain biosynthesis and nodulation of Phaseolus vulgaris. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5606–5614. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5606-5614.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L-X, Wang Y, Pellock B J, Walker G C. Structural characterization of the symbiotically important low-molecular-weight succinoglycan of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6788–6796. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6788-6796.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watson R J, Chan Y K, Wheatcroft R, Yang A F, Han S H. Rhizobium meliloti genes required for C4-dicarboxylate transport and symbiotic nitrogen fixation are located on a megaplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:927–934. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.927-934.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zimmermann J, Voss H, Schwager C, Stegemann J, Erfle H, Stucky K, Kristensen T, Ansoege W. A simplified method protocol for fast plasmid DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]