Abstract

Summary

Vertebral fracture (VF) is a strong predictor of subsequent fracture. In this study of older women, VF, identified by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) vertebral fracture assessment (VFA), were associated with an increased risk of incident fractures and had a substantial impact on fracture probability, supporting the utility of VFA in clinical practice.

Purpose

Clinical and occult VF can be identified using VFA with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The aim of this study was to investigate to what extent VFA-identified VF improve fracture risk prediction, independently of bone mineral density (BMD) and clinical risk factors used in FRAX.

Methods

A total of 2852 women, 75–80 years old, from the prospective population-based study SUPERB cohort, were included in this study. At baseline, BMD was measured by DXA, VF diagnosed by VFA, and questionnaires used to collect data on risk factors for fractures. Incident fractures were captured by X-ray records or by diagnosis codes. An extension of Poisson regression was used to estimate the association between VFA-identified VF and the risk of fracture and the 5- and 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) was calculated from the hazard functions for fracture and death.

Results

During a median follow-up of 5.15 years (IQR 4.3–5.9 years), the number of women who died or suffered a MOF, clinical VF, or hip fracture was 229, 422, 160, and 124, respectively. A VFA-identified VF was associated with an increased risk of incident MOF (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.46–2.18), clinical VF (HR = 2.88; 95% [CI] 2.11–3.93), and hip fracture (HR = 1.67; 95% [CI] 1.15–2.42), adjusted for age, height, and weight. For women at age 75 years, a VFA-identified VF was associated with 1.2–1.4-fold greater 10-year MOF probability compared with not taking VFA into account, depending on BMD.

Conclusion

Identifying an occult VF using VFA has a substantial impact on fracture probability, indicating that VFA is an efficient method to improve fracture prediction in older women.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00198-022-06387-x.

Keywords: Clinical risk factors and bone mineral density, Fracture risk, Older women, Vertebral fracture, Vertebral fracture assessment

Introduction

It is well established that a previous fracture increases the risk of a subsequent fracture in men and women [1]. A patient with a previous fracture should, therefore, be evaluated for the risk for subsequent fractures, and if appropriate, treatment with osteoporosis medication should be initiated, according to applicable osteoporosis evaluation and treatment guidelines [2–6]. A prior vertebral fracture (VF) is a particularly strong risk indicator and the risk is nearly doubled for subsequent nonvertebral fracture and quadrupled for a new VF [7]. It is challenging to diagnose VF when only a quarter of women with VF are symptomatic [8, 9]. All VF are important to identify as the associations with subsequent VF and non-vertebral fractures do not differ between symptomatic (clinical and morphometric) and asymptomatic (morphometric) VF, and the risk increases with the number of prior VF [7]. Also, mild VF constitute a risk factor for future VF, although moderate or severe VF are an even stronger risk factor for subsequent VF and for non-vertebral fractures [10].

Vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) is used to detect VF from lateral spine imaging by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [11, 12]. During the past 20 years, the method has been well established and validated, and is recommended as a routine screening tool in clinical practice [5, 13–16]. The examination is performed in conjunction with bone mineral density (BMD) measurement and the radiation dose is only a small fraction of the dose generated by conventional spine radiography. It has been shown that VFA-identified VF predict future fractures independent of age, weight, and BMD, in elderly women [17–19]. By using VFA, more individuals with asymptomatic VF can be identified, and with a prevalent VF included in the fracture risk assessment, more high-risk individuals will be identified for fracture preventive interventions, such as anti-osteoporosis medication [20, 21].

During the first decade of the 2000s, several fracture risk assessment tools have been developed, of which FRAX® (the fracture risk assessment tool) is the most used worldwide [22, 23]. FRAX provides an estimate of 10-year fracture probability for hip or major osteoporotic fracture (MOF; hip, clinical spine, proximal humerus, or distal forearm), based on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and clinical risk factors, such as prior fragility fracture, parental hip fracture, smoking, systemic glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, other causes of secondary osteoporosis, and excess alcohol intake, with or without BMD. Incorporating BMD into the fracture probability calculation increases the model’s predictive ability [24]. FRAX has been validated in 11 independent cohorts, and is available in 77 countries [25] corresponding to more than 80% of the world population [23, 24]. Previous fractures at different skeletal sites have different importance for subsequent fractures. VF (moderate and severe) are much stronger predictors compared to, for example, distal forearm fractures with recent data suggesting that adjustments for fracture site could be accommodated within fracture risk algorithms [26–28].

VFA is established as a reliable means of identifying VF, and the potential use of this technique as a routine part of DXA assessment, to provide adjunctive risk information, independent of BMD and clinical risk factors, has been studied [18, 19]. The aim of the present study was to determine to which extent VFA-identified VF, in addition to BMD and clinical risk factors used in FRAX, affect fracture probabilities in a large cohort of older Swedish women.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Between March 2013 and May 2016, 3028 women, age 75–80 years, were recruited from the Gothenburg area in Sweden, via the Swedish population register, to a population-based study, the Sahlgrenska University hospital Prospective Evaluation of Risk of Bone fractures (SUPERB). Women were excluded if non-ambulant, unable to understand Swedish, or unable to have a hip BMD measurement. The inclusion process has been described previously [29]. Information about lifestyle factors influencing the risk of osteoporosis and fractures, medical history and medication, and prior fracture were collected through a standardized self-reported questionnaire [30]. Standardized equipment was used for height and weight measures, and the mean values from two measurements were used in the analyses. At baseline, the 10-year probabilities for MOF and hip fracture were assessed with and without BMD, but without VFA results, using the Swedish FRAX model. The participants underwent DXA including VFA. Of 3028 women, 90 (3%) women’s VFA could not be analyzed due to poor image quality and 15 (0.5%) women were not able to undergo a lateral spine scan. No vertebrae had the appearance of primary malignancy or metastasis. Of the 2923 women with assessable VFA, 70 women did not provide answers to all the questions about clinical risk factors included in FRAX and were therefore excluded from the analyses. One subject did not receive a serial number when codes of diagnosis were retrieved from the National Board of Health and Welfare and was therefore excluded. The 71 women who were excluded were shorter (p = 0.03), had a more frequent history of previous falls (p = 0.01), and were more likely to smoke (p = 0.02) and drink alcohol (p < 0.01), than women who answered all the questions about clinical risk factors (Supplemental Table 1). A regional register was used to collect data on mortality. All examinations took place at the Osteoporosis Clinic, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden. The ethical review board at the University of Gothenburg approved the study and all the study participants provided written informed consent.

DXA

DXA was used for measurement of BMD (g/cm2) at the femoral neck (FN) (Discovery A S/N 86,491; Hologic, Waltham, MA, USA). Vertebrae which were fractured and/or contained osteosynthesis materials in the LS (L1 to L4) were excluded. The coefficient of variation (CV) for BMD FN was 1.3%.

VFA

At baseline, with the patient in the supine position, DXA lateral spine imaging was performed, and prevalent VF were identified using the software program Physician’s Viewer (Hologic). The procedure of VFA has been previously described [19]. Briefly, six markers were manually placed on each vertebra T4 to L4 [31]. By using the height measurements from point placements and the Genant semiquantitative method (GSQ), the VF were classified as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), or severe (grade 3), corresponding to height reduction of 20–25%, > 25–40%, and > 40%, respectively [32]. Other morphologic deformities of the vertebral bodies, which had to be differentiated from VF, were short vertebral height, Schmorl’s nodes, Scheuermann’s disease, degenerative remodeling, scoliosis, and Cupid’s bow deformities [33]. To assess the vertebrae and to detect scoliosis, also, the whole body and the lumbar anteroposterior spine images were used. Both assessors were blinded with regard to incident fracture status at the time of VFA analysis. Reproducibility was tested on VFA from 50 women (T4 to L4). The intraobserver agreements were 98.9% and 97.8%, and kappa scores were 0.85 and 0.67, respectively, for the two examiners. The interobserver agreement was 98.6% and kappa score 0.77. When separating grade 1 VF from grade 2 to 3 VF, the interobserver agreement and kappa score for grade 1 was 99.1% and 0.66, respectively, and for grade 2–3 99.4% and 0.84 [19].

In order to examine if the combined number and severity of VFA-identified VF were associated with fracture risk, the Spinal Deformity Index (SDI) was calculated [34, 35]. SDI is a validated method for assessing subsequent vertebral fracture risk. SDI is the sum of the vertebral fracture grades from T4 to L4. Thus, an individual without a VF has SDI = 0, and an individual with one grade 1 VF and two grade 2 VF has SDI = 5 (1 + 2 + 2). In order to achieve more comparable number of women in subgroups with increasing SDI, the women were divided into those having SDI = 0 (n = 2163), SDI = 1 (n = 228), SDI = 2 (n = 213), SDI = 3 (n = 112), SDI = 4–6 (n = 103), and SDI = > 7 (n = 33). The highest recorded SDI was 20.

Incident fracture assessment

In this study, VFA was only performed at baseline. Incident fractures were identified in two ways. During the first period, from baseline to 24th of May 2018, the incident fractures were X-ray-verified using regional registers [19]. Data on incident fractures were also collected through the National Patient Register (NPR) at the National Board of Health and Welfare. From this register, incident fractures were collected from baseline to the 31th of December 2019 using International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes [36]. Regarding incident clinical VF, 20 women with VF were identified through the NPR (from baseline until 31st of Dec 2019) and 145 women with VF were X-ray-verified (from baseline to 24th of May 2018), of which 5 VF also were registered in the NPR. X-ray images of incident clinical VF were compared with baseline VFA images and only new or worsened VF during follow-up were considered incident. The incident clinical VF were considered clinical since they were identified by spine imaging (using X-ray, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic and/or lumbar spine) ordered on the suspicion of a VF. Only 15 incident clinical VF were identified solely by using ICD-10 codes from the NPR. Normally, only symptomatic clinical VF are diagnosed in contrast to asymptomatic VF [9].

Statistical analyses

Independent samples t test was used for analyzing difference in means of continuous variables at baseline between women without VF and women with any VF, and ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test were used between women without VF and women with grade 1 VF, grade 2 VF, or grade 3 VF. Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables at baseline were analyzed by χ2 test. Statistical significance was defined by a p value < 0.05. The association between VFA and the risk of fracture was examined using an extension of the Poisson regression model in the whole cohort [37, 38]. The observation period of each participant was divided in intervals of 1 month. The first endpoint per person was counted for each relevant outcome. Adjustments for confounders were performed in three steps with increasing numbers of covariates included, to establish associations independent of clinical risk factors and BMD. Model 1 was adjusted for age, height, and weight, whereas model 2 was also adjusted for clinical risk factors used in FRAX including self-reported previous fracture (after the age of 50 years, fractures of the skull, and face excluded), family history of hip fracture, current smoking, oral glucocorticoid use (daily treatment with at least 5 mg prednisolone or equivalent for 3 months or more ever during lifetime), rheumatoid arthritis, excessive alcohol intake (21 or more units per week), and secondary osteoporosis (diabetes mellitus (type 1 and 2), menopause before 45 years of age, inflammatory bowel disease and chronic liver disease), but without FN BMD. In model 3, also, FN BMD was included. The hazard function for MOF and death was calculated using the extension of the Poisson regression model mentioned above. For fracture, the variables in the hazard function were current time since baseline, current age, BMI, previous fracture, family history of hip fracture, smoking, corticosteroids, rheumatoid arthritis, alcohol use, secondary osteoporosis, and BMD. One additional model was constructed using the variables mentioned above and adding VFA. For death, the variables in the hazard function were current time since baseline, current age, BMI, current smoking, per oral corticosteroid use, and BMD, the same variables used in the FRAX model. Also, here, one additional model was constructed adding VFA. From the hazard functions for fracture and death, the 5- and 10-year probability of MOF was calculated [22, 39]. Follow-up was approximately 5 years for the SUPERB cohort, so when calculating 10-year probability, the hazard functions were extrapolated in time. It is important to note that the probability models used were based on purpose-built models similar, but not identical, to FRAX. The 10-year probabilities of MOF for women 75 and 80 years old, with previous fracture, were calculated, setting BMI to 26 kg/m2, but no other clinical risk factors, according to femoral neck BMD T-score, with VFA-identified VF and without considering VFA in the analyses. Incidence per 1000 person-years was calculated as number of events divided by total follow-up time (until fracture, death, or censoring) per 1000 years. For any VFA-identified VF, grade 2 VF, grade 3 VF, one VF, two VF, and three or more VF, post hoc statistical power analyses were performed, demonstrating > 80% power (with an alpha of 0.05) for incident MOF and clinical VF. For incident hip fracture, the post hoc power was > 80% for grade 3 VF and two VF but inferior for any, grade 2 VF, one VF, and three or more VF (78%, 7%, 35%, 40%, respectively). The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics Version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Characteristics

In total, 2852 women were included in the analysis, of which 2163 (76%) did not have any VFA-identified VF. Of the 689 remaining women (24%), 260 (9%) had a sole grade 1 VF, 216 (8%) had a grade 2 VF (with or without grade 1 VF), and 213 (7%) had a grade 3 VF (with or without grade 1 or grade 2 VF). A total of 481 women (17%) had one VF, 141 (5%) had two VF, and 67 (2%) had three or more VF. Out of 1805 women who did not report a prior (any) fracture 359 (20%) had a VFA-identified VF. Out of 125 women that reported a prior VF, 33 (26.4%) did not have any VFA-identified VF. Baseline characteristics of women without VF and any VF, and VF according to severity and number are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Women with VF had lower FN, were older, and shorter than women without VF. Women with VF had higher FRAX 10-year probability, more frequently prior fracture, osteoporosis and heart failure, and more were using osteoporosis medication and glucocorticoids, than women without VF.

Table 1.

Characteristics of older women without VFA-diagnosed VF and with any VF

|

No VF n = 2163 |

Any VF n = 689 |

p valuea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.7 ± 1.6 | 78.0 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 162.2 ± 5.9 | 161.3 ± 5.8 | < 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.5 ± 11.9 | 68.7 ± 12.1 | 0.650 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 4.3 | 26.4 ± 4.3 | 0.059 |

| Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Femoral neck BMD (T-score) | − 1.57 ± 0.90 | − 1.83 ± 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| FRAX hip fracture without BMD (%) | 17.7 ± 12.2 | 19.4 ± 12.6 | 0.003 |

| FRAX MOF with BMD (%) | 22.0 ± 11.3 | 26.1 ± 12.8 | < 0.001 |

| FRAX hip fracture with BMD (%) | 10.3 ± 10.5 | 13.2 ± 12.5 | < 0.001 |

| Fall within the last year, % (n) | 28.9 (626) | 29.9 (206) | 0.630 |

| Self-reported prior fracture, % (n)c | 33.1 (717) | 47.9 (330) | < 0.001 |

| Family history of hip fracture, % (n) | 17.2 (373) | 18.9 (130) | 0.330 |

| Current smoking, % (n) | 5.0 (109) | 5.1 (35) | 0.966 |

| Excessive alcohol consumption, % (n)d | 0.5 (10) | 0.6 (4) | 0.754j |

| Secondary osteoporosis, % (n)e | 22.7 (492) | 19.9 (137) | 0.126 |

| Medications | |||

| Glucocorticoid use, % (n)f | 3.0 (64) | 4.8 (33) | 0.021 |

| Osteoporosis medication, % (n)g | 8.2 (178) | 18.0 (124) | < 0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis, % (n) | 3.7 (79) | 4.2 (29) | 0.505 |

| Hyperthyroidism, % (n) | 5.1 (110) | 4.7 (32) | 0.645 |

| Osteoporosis, % (n)h | 16.5 (356) | 32.4 (223) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 52.3 (1131) | 51.8 (357) | 0.828 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 6.4 (139) | 7.8 (54) | 0.199 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 4.4 (95) | 5.7 (39) | 0.171 |

| Angina, % (n) | 5.0 (107) | 6.4 (44) | 0.144 |

| Heart failure, % (n) | 7.7 (166) | 10.4 (72) | 0.022 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 9.6 (207) | 10.2 (70) | 0.649 |

| Chronic bronchitis, asthma, emphysema, % (n) | 9.2 (200) | 11.0 (76) | 0.168 |

| Cancer, % (n) | 20.2 (437) | 20.9 (144) | 0.693 |

| Glaucoma, % (n) | 8.6 (187) | 6.8 (47) | 0.129 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentage and number for categorical variables

Significance was defined by a p-value < 0.05 and significant values are presented in bold

VFA vertebral fracture assessment, VF vertebral fracture, BMD bone mineral density

aIndependent samples t test for continuous variables

bCategorical variables χ2 test

cAfter 50 years of age, fractures of the skull and face are excluded

d21 or more units per week

eDiabetes (type 1 and type 2), menopause before 45 years of age, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease

fDaily oral treatment with at least 5 mg for 3 months or more ever during lifetime

gCurrent treatment with bisphosphonates, teriparatide, or denosumab

hSelf-reported

i666

jFisher’s exact test. FRAX-scores were calculated without information from VFA

Table 2.

Characteristics of older women with VF according to severity and number

|

No VF n = 2163 |

Grade 1 VF n = 260 |

Grade 2 VF n = 216 |

Grade 3 VF n = 213 |

p- valuea,b |

1 VF n = 481 |

2 VF n = 141 |

≥ 3 VF n = 67 |

p-valuea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.7 ± 1.6 | 78.0 ± 1.5§ | 78.0 ± 1.6 | 78.1 ± 1.6# | < 0.01 | 78.0 ± 1.6† | 78.0 ± 1.5 | 78.2 ± 1.7 | < 0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 162.2 ± 5.9 | 161.9 ± 5.6 | 161.8 ± 5.8 | 159.9 ± 6.0# Ω€ | < 0.01 | 161.6 ± 5.8 | 161.2 ± 5.6 | 159.2 ± 6.3∑ β | < 0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.5 ± 11.9 | 69.3 ± 11.4 | 69.4 ± 12.4 | 67.4 ± 12.6 | 0.28 | 68.8 ± 11.6 | 70.7 ± 12.7 | 64.3 ± 13.4∑ β µ | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 4.3 | 26.4 ± 4.0 | 26.5 ± 4.5 | 26.3 ± 4.5 | 0.29 | 26.3 ± 4.2 | 27.2 ± 4.4£ | 25.2 ± 4.6 β | 0.01 |

| Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.65 ± 0.10§ | 0.64 ± 0.09¤ | 0.62 ± 0.11# Ω | < 0.01 | 0.64 ± 0.09† | 0.64 ± 0.09£ | 0.60 ± 0.12∑ β µ | < 0.01 |

| Femoral neck BMD (T-score) | − 1.57 ± 0.90 | − 1.73 ± 0.81§ | − 1.83 ± 0.73¤ | − 1.95 ± 0.89# Ω | < 0.01 | − 1.79 ± 0.79† | − 1.80 ± 0.79£ | − 2.19 ± 0.97∑ β µ | < 0.01 |

| FRAX MOF without BMD (%) | 30.3 ± 11.9 | 30.9 ± 10.8 | 32.2 ± 12.0 | 35.9 ± 13.6# Ω€ | < 0.01 | 32.1 ± 11.9† | 33.3 ± 12.1£ | 37.4 ± 14.0∑ β | < 0.01 |

| FRAX hip fracture without BMD (%) | 17.7 ± 12.2 | 17.7 ± 10.5 | 18.9 ± 12.3 | 21.9 ± 14.9# Ω | < 0.01 | 18.7 ± 12.1 | 19.5 ± 12.5 | 23.5 ± 16.0∑ β | < 0.01 |

| FRAX MOF with BMD (%) | 22.0 ± 11.3 | 23.9 ± 11.4§ | 25.2 ± 11.5¤ | 29.6 ± 14.8# Ω€ | < 0.01 | 25.1 ± 12.4† | 26.4 ± 11.9£ | 32.3 ± 15.5∑ β µ | < 0.01 |

| FRAX hip fracture with BMD (%) | 10.3 ± 10.5 | 11.4 ± 10.8 | 12.4 ± 11.1¤ | 16.1 ± 11.1# Ω€ | < 0.01 | 12.4 ± 12.0† | 13.1 ± 11.8£ | 18.8 ± 16.3∑ β µ | < 0.01 |

| Fall within the last year, % (n) | 28.9 (626) | 25.0 (65) | 27.8 (60) | 38.0 (81) | 0.02 | 26.6 (128) | 39.0 (55) | 34.3 (23) | 0.03 |

| Self-reported prior fracture, % (n)c | 33.1 (717) | 38.1 (99) | 45.8 (99) | 62.0 (132) | < 0.01 | 44.1 (212) | 53.2 (75) | 64.2 (43) | < 0.01 |

| Family history of hip fracture, % (n) | 17.2 (373) | 17.7 (46) | 18.5 (40) | 20.7 (44) | 0.64 | 18.3 (88) | 21.3 (30) | 17.9 (12) | 0.65 |

| Current smoking, % (n) | 5.0 (109) | 3.1 (8) | 5.6 (12) | 7.0 (15) | 0.26 | 4.0 (19) | 5.0 (7) | 13.4 (9) | 0.01 |

| Excessive alcohol consumption, % (n)d | 0.5 (10) | 0.8 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.9 (2) | 0.33 k | 0.6 (3) | 0.7 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.69 k |

| Secondary osteoporosis, % (n)e | 22.7 (492) | 24.2 (63) | 16.2 (35) | 18.3 (39) | 0.06 | 18.9 (91) | 21.3 (30) | 23.9 (16) | 0.31 |

| Medications | |||||||||

| Glucocorticoid use, % (n)f | 3.0 (64) | 3.1 (8) | 4.2 (9) | 7.5 (16) | 0.01 | 3.7 (18) | 6.4 (9) | 9.0 (6) | 0.01 k |

| Osteoporosis medication, % (n)g | 8.2 (178) | 10.4 (27) | 13.4 (29) | 31.9 (68) | < 0.01 | 14.8 (71) | 21.3 (30) | 34.3 (23) | < 0.01 |

| Medical history | |||||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis, % (n) | 3.7 (79) | 4.6 (12) | 2.8 (6) | 5.2 (11) | 0.51 | 4.4 (21) | 2.8 (4) | 6.0 (4) | 0.62 |

| Hyperthyroidism, % (n) | 5.1 (110) | 4.6 (12) | 4.6 (10) | 4.7 (10) | 0.98 | 4.8 (23) | 3.5 (5) | 6.0 (4) | 0.84 |

| Osteoporosis, % (n)h | 16.5 (356) | 24.2 (63) | 27.3 (59) | 47.4 (101) | < 0.01 | 27.2 (131) | 38.3 (54) | 56.7 (38) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 52.3 (1131) | 51.2 (133) | 53.2 (115) | 51.2 (109) | 0.96 | 51.8 (249) | 51.1 (72) | 53.7 (36) | 0.98 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 6.4 (139) | 8.5 (22) | 4.6 (10) | 10.3 (22) | 0.06 | 7.3 (35) | 6.4 (9) | 14.9 (10) | 0.05 |

| Myocardial infarction, % (n) | 4.4 (95) | 4.2 (11) | 5.1 (11) | 8.0 (17) | 0.12 | 4.8 (23) | 7.1 (10) | 9.0 (6) | 0.17 |

| Angina, % (n) | 5.0 (107) | 4.6 (12) | 7.9 (17) | 7.0 (15) | 0.18 | 5.8 (28) | 7.1 (10) | 9.0 (6) | 0.33 |

| Heart failure, % (n) | 7.7 (166) | 9.2 (24) | 10.2 (22) | 12.2 (26) | 0.09 | 8.3 (40) | 17.0 (24) | 11.9 (8) | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 9.6 (207) | 11.9 (31) | 6.9 (15) | 11.3 (24) | 0.26 | 9.1 (44) | 10.6 (15) | 16.4 (11) | 0.28 |

|

Chronic bronchitis, asthma, emphysema, % (n) |

9.2 (200) | 10.0 (26) | 11.6 (25) | 11.7 (25) | 0.49 | 10.6 (51) | 11.3 (16) | 13.4 (9) | 0.48 |

| Cancer, % (n) | 20.2 (437) | 22.3 (58) | 20.8 (45) | 19.2 (41) | 0.84 | 21.8 (105) | 17.0 (24) | 22.4 (15) | 0.61 |

| Glaucoma, % (n) | 8.6 (187) | 7.7 (20) | 7.9 (17) | 4.7 (10) | 0.24 | 7.1 (34) | 6.4 (9) | 6.0 (4) | 0.49 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentage and number for categorical variables

Significance was defined by a p-value < 0.05 and significant values are presented in bold

VFA vertebral fracture assessment, VF vertebral fracture, BMD bone mineral density

§Grade 1 VF vs. no VF

¤Grade 2 VF vs. no VF

#Grade 3 VF vs. no VF

ΩGrade 3 VF vs. grade 1 VF

€Grade 3 VF vs. grade 2 VF

†One VF vs. no VF

£Two VF vs. no VF

∞Two VF vs. one VF

∑Three or more VF vs. no VF

βThree or more VF vs. one VF

µThree or more VF vs. two VF

aContinuous variables one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test

bCategorical variables χ2 test

cAfter 50 years of age, fractures of the skull and face are excluded

d21 or more units per week

eDiabetes (type 1 and type 2), menopause before 45 years of age, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease

fDaily oral treatment with at least 5 mg for 3 months or more ever during lifetime

gCurrent treatment with bisphosphonates, teriparatide, or denosumab

hSelf-reported

i192

j46

kFisher’s exact test. FRAX-scores were calculated without information from VFA

VF and associations with incident fracture

Associations between VF and three different categories of first incident fracture, MOF, clinical VF, and hip fracture, are presented in Table 3. During a median follow-up time of 5.15 years (IQR 4.3–5.9 years), 229 women died, and 422 women sustained a MOF. Of those with an incident MOF, 160 women sustained a clinical VF, and 124 women a hip fracture. Extension of the Poisson regression model, adjusted for age, height, and weight revealed that having a VFA-identified VF (any) was associated with increased risk of sustaining an incident MOF (HR 1.78 [95% CI 1.46–2.18]), a clinical VF (HR 2.88 [95% CI 2.11–3.93]), and a hip fracture (HR 1.67 [95% CI 1.15–2.42]). These associations were independent of prevalent self-reported fracture and other clinical risk factors included in FRAX and FN BMD, with the exception of hip fracture (Table 3). There was no interaction between VFA-identified VF and prevalent self-reported fracture regarding MOF (adjusted for age, height, weight, clinical risk factors, and FN BMD) (p = 0.81). In a subgroup analysis, where the cohort was divided into those with or without self-reported fracture, VFA-identified VF predicted MOF independent of clinical risk factors and FN BMD similarly in both groups (HR 1.52 [95% CI 1.15–2.00], and HR 1.53 [95% CI 1.14–2.07], respectively).

Table 3.

Associations between VF identified using VFA and fracture risk in older women

|

No VF n = 2163 |

Any VF n = 689 |

Grade 1 VF n = 260 |

Grade 2 VF n = 216 |

Grade 3 VF n = 213 |

1 VF n = 481 |

2 VF n = 141 |

≥ 3 VF n = 67 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOF | ||||||||

| No. (%) | 273 (12.6) | 149 (21.6) | 47 (18.1) | 44 (20.4) | 58 (27.2) | 97 (20.2) | 33 (23.4) | 19 (28.4) |

| Rate per 1000 person-years | 26.7 | 48.1 | 38.9 | 44.7 | 63.7 | 44.3 | 51.7 | 69.2 |

| Time at risk, median (Q3-Q1), years | 4.80 (1.83) | 4.92 (1.79) | 5.10 (1.53) | 4.90 (1.97) | 4.78 (1.89) | 4.93 (1.83) | 4.82 (1.70) | 4.83 (2.42) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Adjusted for age, height, weight | 1 (Reference) | 1.78 (1.46–2.18) | 1.44 (1.05–1.96) | 1.65 (1.20–2.66) | 2.38 (1.79–3.17) | 1.65 (1.31–2.08) | 1.91 (1.33–2.74) | 2.58 (1.62–4.12) |

| + clinical risk factors | 1 (Reference) | 1.65 (1.34–2.02) | 1.40 (1.03–1.91) | 1.54 (1.12–2.13) | 2.03 (1.51–2.73) | 1.56 (1.23–1.97) | 1.75 (1.21–2.52) | 2.09 (1.30–3.37) |

| + FN BMD | 1 (Reference) | 1.52 (1.24–1.87) | 1.33 (0.97–1.81) | 1.41 (1.02–1.94) | 1.82 (1.35–2.44) | 1.46 (1.16–1.85) | 1.58 (1.10–2.28) | 1.79 (1.11–2.90) |

| VF (clinical) | ||||||||

| No. (%) | 83 (3.8) | 77 (11.2) | 18 (6.9) | 25 (11.6) | 34 (16.0) | 47 (9.8) | 14 (9.9) | 16 (23.9) |

| Rate per 1000 person-years | 7.8 | 23.4 | 14.0 | 24.0 | 35.1 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 56.8 |

| Time at risk, median (Q3-Q1), years | 4.96 (1.71) | 5.13 (1.61) | 5.18 (1.22) | 5.15 (1.67) | 4.94 (1.82) | 5.15 (1.59) | 5.14 (1.56) | 4.92 (1.99) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Adjusted for age, height, weight | 1 (Reference) | 2.88 (2.11–3.93) | 1.74 (1.05–2.90) | 2.92 (1.86–4.56) | 4.15 (2.77–6.22) | 2.51 (1.76–3.60) | 2.42 (1.37–4.26) | 6.70 (3.89–11.53) |

| + clinical risk factors | 1 (Reference) | 2.75 (2.01–3.77) | 1.72 (1.03–2.86) | 2.90 (1.84–4.56) | 3.89 (2.55–5.93) | 2.47 (1.72–3.55) | 2.32 (1.30–4.13) | 6.35 (3.60–11.21) |

| + FN BMD | 1 (Reference) | 2.61 (1.90–3.58) | 1.65 (0.99–2.75) | 2.71 (1.72–4.26) | 3.64 (2.38–5.56) | 2.36 (1.64–3.39) | 2.19 (1.23–3.90) | 5.79 (3.26–10.28) |

| Hip | ||||||||

| No. (%) | 81 (3.7) | 43 (6.2) | 12 (4.6) | 9 (4.2) | 22 (10.3) | 25 (5.2) | 13 (9.2) | 5 (7.5) |

| Rate per 1000 person-years | 7.5 | 12.5 | 9.1 | 8.2 | 21.4 | 10.4 | 18.6 | 15.3 |

| Time at risk, median (Q3-Q1), years | 4.99 (1.69) | 5.19 (1.38) | 5.25 (1.17) | 5.27 (1.39) | 5.05 (1.62) | 5.21 (1.36) | 5.14 (1.45) | 5.16 (1.67) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Adjusted for age, height, weight | 1 (Reference) | 1.67 (1.15–2.42) | 1.18 (0.64–2.16) | 1.07 (0.54–2.13) | 3.08 (1.91–4.98) | 1.37 (0.87–2.15) | 2.58 (1.43–4.65) | 2.09 (0.84–5.19) |

| + clinical risk factors | 1 (Reference) | 1.53 (1.05–2.22) | 1.16 (0.63–2.14) | 1.03 (0.51–2.05) | 2.58 (1.57–4.22) | 1.31 (0.83–2.06) | 2.41 (1.33–4.37) | 1.64 (0.65–4.12) |

| + FN BMD | 1 (Reference) | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 1.07 (0.58–1.97) | 0.90 (0.45–1.80) | 2.12 (1.29–3.48) | 1.19 (0.76–1.87) | 2.08 (1.15–3.77) | 1.24 (0.49–3.16) |

| Death | ||||||||

| No. (%) | 165 (7.6) | 64 (9.3) | 22 (8.5) | 13 (6.0) | 29 (13.6) | 40 (8.3) | 13 (9.2) | 11 (16.4) |

| Rate per 1000 person-years | 15.1 | 18.1 | 16.4 | 11.6 | 27.1 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 33.1 |

| Time at risk, median (Q3-Q1), years | 5.10 (1.66) | 5.24 (1.29) | 5.26 (1.10) | 5.32 (1.29) | 5.17 (1.52) | 5.26 (1.26) | 5.18 (1.26) | 5.18 (1.36) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Adjusted for age, height, weight | 1 (Reference) | 1.15 (0.86–1.53) | 1.06 (0.68–1.65) | 0.72 (0.41–1.27) | 1.72 (1.15–2.56) | 1.02 (0.72–1.45) | 1.16 (0.66–2.04) | 2.01 (1.09–3.72) |

| + clinical risk factors | 1 (Reference) | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) | 1.10 (0.70–1.71) | 0.77 (0.43–1.35) | 1.88 (1.25–2.84) | 1.09 (0.77–1.55) | 1.27 (0.72–2.24) | 2.09 (1.11–3.91) |

| + FN BMD | 1 (Reference) | 1.16 (0.86–1.55) | 1.07 (0.68–1.67) | 0.73 (0.41–1.28) | 1.78 (1.18–2.70) | 1.05 (0.74–1.49) | 1.21 (0.69–2.15) | 1.91 (1.02–3.60) |

Associations were examined using an extension of the Poisson regression model. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. Model 1: adjusted for age, height and weight. Model 2: adjusted for age, height, weight, and the clinical risk factors used in FRAX (self-reported previous fracture, family history of hip fracture, current smoking, oral glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, excessive alcohol intake, secondary osteoporosis) except FN BMD. Model 3: adjusted for the same as model 2 with the addition of FN BMD

VF vertebral fracture, VFA vertebral fracture assessment, FN femoral neck, BMD bone mineral density, MOF major osteoporotic fracture, Q quartile

VF was divided into severity (grade 1 VF, grade 2 VF, or grade 3 VF) and having a grade 3 VF was associated with more than doubled risk of MOF (HR 2.38 [95% CI 1.79–3.17]), tripled risk of hip fracture (HR 3.08 [95% CI 1.91–4.98]), and quadrupled risk of clinical VF (4.15 [95% CI 2.77–6.22]). Associations between any VFA-identified VF and VFA-identified VF according to severity and number, with incident MOF and clinical VF, remained after adjustments for clinical risk factors and FN BMD, except for grade 1 VF. Having any VFA-identified VF, grade 3 VF, or three or more VF was associated with hip fracture independent of clinical risk factors, and for grade 3 VF and 2 VF also independent of FN BMD (Table 3). Having a grade 1 VF was associated with 44% increased risk of MOF (HR 1.44 [95% CI 1.05–1.96]), and 74% increased risk of clinical VF (HR 1.74 [95% CI 1.04–2.89]), independent of clinical risk factors but not of FN BMD. Grade 1 VF was not significantly associated with hip fracture.

Using SDI = 0 as a reference, all remaining SDI groups had significantly higher risk of incident MOF and clinical VF independently of clinical risk factors and FN BMD, with the exception for SDI = 2 for MOF, and HR increased according to grade of SDI. Having an SDI = > 7 was associated with 6 times increased risk of clinical incident VF (5.99 [2.75–12.57]) (Supplemental Tables 2).

The impact of VFA-identified VF on fracture probabilities

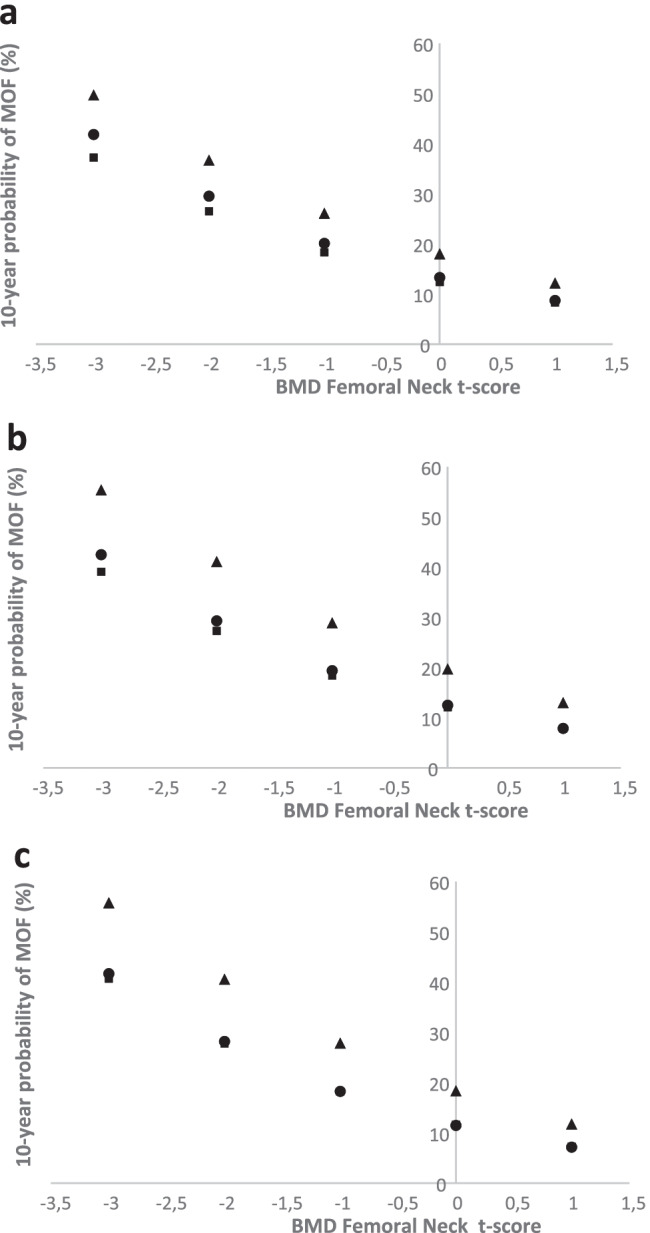

The follow-up time was extrapolated up to 10 years to allow for calculations of 10-year fracture probabilities. For a 75-year-old woman with a previous fracture but no other clinical risk factors, a BMD T-score − 2, a VFA-identified VF (any) increased the 10-year probability for MOF from 29.5 (without considering VFA) to 36.7% (having a VFA-identified VF (any)) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Ten-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) in a 75-year-old woman with a self-reported fracture, according to T-score of femoral neck BMD and VFA-identified VF. The closed circle denotes probabilities calculated without information from the VFA, the triangle represents the probability with a VFA-identified VF, and the closed square represents the probability without any VFA-identified VF. Probabilities are shown for any VFA-identified VF (a), grade 3 VFA-identified VF (b), and three or more VFA-identified VF (c). BMI is set to 26 kg/m2, previous fracture to yes, but all other clinical risk factors set to no

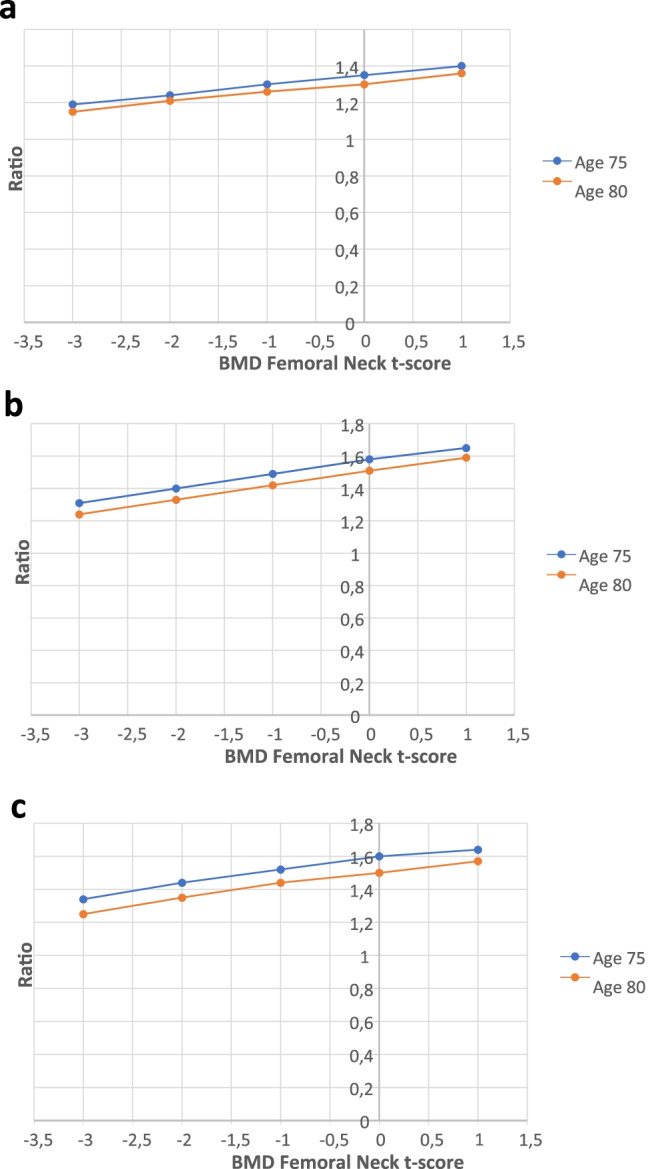

The ratios between the calculated 10-year probability for MOF with VFA-identified any VF, and without considering VFA for women 75 and 80 years old, with previous fracture, BMI of 26 kg/m2, but no other clinical risk factors, according to femoral neck BMD T-score are presented in Fig. 2a. The figure shows that a 75-year-old woman has a 1.24-fold increased 10-year probability of MOF than a woman with the same risk factors but without considering VFA. The relative importance of having VFA-identified VF on fracture probability was slightly greater at higher BMD values in both 75 and 80-year-old women (due to higher risk of death at lower BMD levels) (Fig. 2a), but the impact on absolute probability was small at higher BMD levels (Fig. 1a). For grade 1 VF, a similar pattern was seen, i.e., the relative importance of having a VF vs. not having one was greater with higher BMD, but the absolute risk differences were quite small at higher BMD-values (Supplemental Tables 4a–b).

Fig. 2.

The ratio between the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) with VFA-identified any VF (a), grade 3 VF (b), three or more VF (c), and without considering VFA results, shown for women 75 and 80 years old with self-reported fracture, according to femoral neck BMD T-score. BMI is set to 26 kg/m2, previous fracture to yes, but all other clinical risk factors set to no

The 5-year probabilities of MOF for women 75 and 80 years old, with previous fracture, BMI of 26 kg/m2, but no other clinical risk factors, with BMD T-score − 2, increased from 17.2 to 22.0% and 20.3 to 25.2%, respectively, when VFA-identified VF (any) was taken into account. The 5-year probabilities and ratios, according to age and BMD T-score, are presented in the Supplemental Tables 3a–b.

The impact of severity and number of VFA-identified VF on fracture probabilities

Similar analyses, as for any VF, were performed also for grade 3 VF and three or more VF, separately. For women 75 years old, with a BMD T-score − 2, a VFA-identified grade 3 VF or three or more VF increased the 10-year probability of MOF, from 29.3 to 41.1% and 28.2 to 40.6%, respectively (Fig. 1b, c).

The ratios between the calculated 10-year probabilities with VFA-identified grade 3 VF, and without considering VFA, show that a 75-year-old woman, with previous fracture but no other clinical risk factors, BMI of 26 kg/m2, and with BMD T-score − 2, has a 1.40-fold increased 10-year probability of MOF compared with a woman with the same risk factors but without considering VFA. For VFA-identified three or more VF, the 10-year probability of MOF is increased by 44% (a factor of 1.44), when taking into consideration the identified VF compared to no consideration to VFA (Fig. 2b, c).

Discussion

In this study of older Swedish women, VF identified using VFA by DXA was associated with an increased incidence of MOF and clinical VF, independently of FN BMD and clinical risk factors, including self-reported prior fracture, in FRAX. Fracture risk increased with severity and number of VF. Having a VF (independently of severity) increased the 10-year probability of MOF substantially, indicating that VFA-identified VF should be taken into account when assessing the fracture risk in older women.

In Sweden, new clinical recommendations from the National Board of Health and Welfare, covering target levels of evaluation and treatment of diseases of the musculoskeletal system, were published in 2021 [40]. In these new recommendations, the target level for the proportion of VFA’s in conjunction with central DXA was set to 100%. However, due to an insufficient number of DXA devices in Sweden (66 devices in a population of 10.5 million), implementing VFA as a routine measurement could be challenging [41].

The hypothesis of the present study was to examine if incorporating VFA with other clinical risk factors into a fracture risk calculation would enhance the fracture risk assessment and have a major impact on fracture probabilities. In this study, the FRAX tool was chosen since it is currently the best validated and used fracture risk assessment algorithm worldwide [22]. FRAX is currently incorporated in 80 guidelines globally [42]. One important difference to other fracture risk tools, such as the Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator [43] and Qfracture [44], is that FRAX (using a Poisson regression) takes into account the probability of death [22, 27]. In FRAX, some of the clinical risk factors for hip fracture and MOF are also risk factors for death, increasing age, low BMI, low BMD, smoking, and oral glucocorticoid use, and are therefore entered in the death hazard function [45, 46]. Hazard functions for fracture and death are then computed for four models (10-year probability of hip or MOF with or without BMD) and significant interactions for each risk factor, determined from meta-analyses, are entered in the models. Being aware that the FRAX algorithm takes the competing risk of death into the calculation of fracture probability is especially important when studying fracture risk in populations with advanced age, such as the presently investigated SUPERB cohort.

However, there are some limitations with the FRAX tool. The algorithm does not take into account the dose and duration effect of smoking, alcohol, and glucocorticoid exposure, or if there are more than one prior fracture at any site present, and history of falls is not included as a risk factor for fracture. Since 2008, post-FRAX modifications have been presented to address some of these limitations [23, 47–50]. For example, the recency and site of a prior fracture have been shown to affect subsequent fracture risk [51], leading to the development of age- and sex-specific adjustment ratios that can be applied if the past fracture occurred within the previous 2 years [28]. Likewise, the probability ratios (ratio of probability calculated for an individual with VFA-identified VF and probability calculated without using VFA results) derived in the present study suggest a substantial impact on 10-year fracture probabilities. It is important to emphasize that VFA-identified VF contributes to the fracture probability independently of self-reported fracture, demonstrating the importance of prevalent fracture type on future risk. Interestingly, this relationship was BMD-dependent, with greater absolute fracture probability differences seen between women with and without a VF, in the lower than in the higher BMD ranges. However, the relative risk difference increased with BMD, indicating that identified VF contributes considerably to fracture probabilities across the BMD spectrum. The results of the present study are consistent with the results presented by Schousboe et al. [18], although the latter study used calculated FRAX scores based on the Canadian FRAX model, rather than incorporating the FRAX risk variables in Poisson similar but not equal to the FRAX-model. Thus, future similar studies analyzing the effect of incorporating VFA results in the FRAX are required, and if the results are consistent, it is possible that VFA-identified VF could be used to adjust FRAX, using either a post-FRAX modification algorithm, such as for glucocorticoid treatment or TBS, or be incorporated in the FRAX tool [47, 50]. In the meantime, it could be argued that prevalent fracture should be inputted in the current FRAX model, when a VFA detected VF is identified, given the similar hazard ratios for self-reported and VFA-identified VF for MOF [1].

To identify a VF (symptomatic or asymptomatic), preferably by VFA, is of great clinical importance as it might change that person’s risk of fracture from “high risk” to “very high risk” [52]. Individuals at high risk for fracture are usually recommended treatment with an antiresorptive drug (e.g., bisphosphonates, denosumab) while individuals at very high risk for fracture benefit from an anabolic treatment (e.g., teriparatide, romosozumab) followed by an antiresorptive drug (sequential treatment) [4, 52], a treatment regimen that reduces fractures more efficiently than a bisphosphonate alone [53, 54]. Recently, several publications have approached the categorization of fracture risk into low, high, or very high based on the 10-year probability of MOF from FRAX (clinical risk factors with or without BMD), and age-dependent intervention FRAX thresholds [5, 55]. Our study demonstrates that a VFA-identified VF substantially uplifts the MOF probability, beyond that captured by a previous fracture at any site, with greater impact seen with VF severity and number, for example, having three or more VF, increased the 10-year probability of MOF from 28.2 to 40.6% in a 75-year-old woman with BMD t-score − 2 SD. This additional knowledge from VFA would impact treatment decisions and consideration of sequential treatment as the first line option.

It has previously been demonstrated that VF according to number and severity [56], and regardless if VF are symptomatic or asymptomatic [57], are associated with increased mortality. In this study, women with at least one grade 3 VFA-identified VF or ≥ 3 VFA-identified VF had an increased risk of death independently of clinical risk factors and BMD (Table 3), consistent with previous reports.

There are some strengths of the present study. It is a large population-based prospective study and incident fractures were identified with high accuracy through X-ray verification and ICD-10 codes from the NPR. This is the first study investigating the impact of VFA-identified VF on fracture probability tested within the FRAX framework, including FRAX clinical risk factors and BMD. The meticulous evaluation of VF and differential diagnosis and exclusion of other vertebral deformities constitutes a strength of this study and most likely contributes to the associations seen between grade 1 VF and incident fractures. As a result, the prevalence of mild VF was lower than expected and similar to the prevalence of moderate and/or severe VF in this study, which is in contrast to previous studies, reporting a higher prevalence of mild than moderate or severe VF [58, 59]. However, similar studies as well as meta-analyses will be needed to investigate if VFA-identified VF in future FRAX-models could provide additional value. A limitation is that only ambulatory, Swedish, older women, 75 to 80 years old, were included, implying that the results cannot be generalized to women residing in nursing homes, to those with other origin, or to women of other ages. One of the limitations of this study is that only those with clinical VF were included in MOF outcome. The number of incident clinical VF identified via the NPR (ICD 10-codes) was fewer than X-ray-identified clinical VF (from baseline until 24th of May 2018), indicating that the number of clinical VF identified via the NPR between 24th of May 2018 and 31st of Dec 2019 was underestimated. Overall, it is a fair assumption that the impact of VFA-identified VF in predicting future clinical VF (and MOF) would be even stronger if also asymptomatic VF had been captured. It has been reported that a recent prior MOF is associated with an even higher subsequent risk of MOF compared to an older one [51]. Thus, a recent VFA-identified VF would have a larger impact on fracture risk than an old one, but information regarding recency was not available here. In the clinical setting, recency of a prevalent VF is often known, and if considered, the fracture risk assessment could be further improved [28]. An additional limitation is that data on incident bone-specific treatment during the follow-up were not available. Furthermore, 71 women were not included because of missing information about all clinical risk factors in FRAX. Compared to the 2852 women included in the analyses, they were shorter, had more previous falls, and smoked and used alcohol more frequently, which might imply risk of bias; however, the number of individuals was limited, and we believe that the exclusion of these women did not have a substantial impact on the results of this study. Lastly, the power for detecting significant associations between grade 1 VF, grade 2 VF, one VF, three or more VF, and incident hip fracture was inferior compared to the power for the other fracture groups.

In conclusion, VFA-identified VF in older women were associated with incident MOF and clinical VF, independently of self-reported fracture and other clinical risk factors included in FRAX and FN BMD. By adding VFA-identified VF in models including FRAX clinical risk factors and BMD, the 10-year probability of MOF increased substantially, indicating that VFA by DXA should be used in the clinical practice to improve fracture prediction in older women.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) and Sahlgrenska University Hospital (ALF/LUA).

Declarations

Ethics approval

All subjects signed an informed consent prior to participation. The study has been approved by the regional Ethics Review Board in Gothenburg.

Conflicts of interest

M. Lorentzon has received lecture fees from Amgen, Astellas, Lilly, Meda, Renapharma, UCB Pharma, and consulting fees from Amgen, Radius Health, UCB Pharma, Renapharma, and Consilient Health. N. Harvey has received consultancy, lecture fees, and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, MSD, Eli Lilly, Servier, Shire, UCB, Kyowa Kirin, Consilient Healthcare, Radius Health, and Internis Pharma. E. McCloskey has received research funding, consultancy, lecture fees, and/or honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Consilient Healthcare, Fresenius Kabi, GSK, Hologic, Internis, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Synexus, UCB, Unilever, and Warner Chilcott. All other authors state that they have no conflicts of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P, Eisman J, et al. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontalis A, Kenanidis E, Kotronias RA, Papachristou A, Anagnostis P, Potoupnis M, Tsiridis E. Current and emerging osteoporosis pharmacotherapy for women: state of the art therapies for preventing bone loss. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:1123–1134. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1594772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorentzon M. Treating osteoporosis to prevent fractures: current concepts and future developments. J Intern Med. 2019;285:381–394. doi: 10.1111/joim.12873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for C, Economic Aspects of O, the Committees of Scientific A, National Societies of the International Osteoporosis F European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:3–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, National Osteoporosis F. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–739. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnell O, Oden A, Caulin F, Kanis JA. Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s001980170131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink HA, Milavetz DL, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Genant HK, Black DM, Ensrud KE, Fracture Intervention Trial Research G What proportion of incident radiographic vertebral deformities is clinically diagnosed and vice versa? J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1216–1222. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA. Mild morphometric vertebral fractures predict vertebral fractures but not non-vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genant HK, Li J, Wu CY, Shepherd JA. Vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: a new method for clinical assessment. J Clin Densitom. 2000;3:281–290. doi: 10.1385/JCD:3:3:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rea JA, Li J, Blake GM, Steiger P, Genant HK, Fogelman I. Visual assessment of vertebral deformity by X-ray absorptiometry: a highly predictive method to exclude vertebral deformity. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:660–668. doi: 10.1007/s001980070063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schousboe JT, Vokes T, Broy SB, Ferrar L, McKiernan F, Roux C, Binkley N. Vertebral fracture assessment: the 2007 ISCD official positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:92–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Lee YK, Oh SH, Ahn J, Lee YE, Pyo JH, Choi YY, Kim D, Bae SC, Sung YK, Kim DY. A systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) in postmenopausal women and elderly men. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1691–1699. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3436-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Mao Y, Nieves JW. Identification of prevalent vertebral fractures using Vertebral Fracture Assessment (VFA) in asymptomatic postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone. 2020;136:115358. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Compston J, Cooper A, Cooper C, Gittoes N, Gregson C, Harvey N, Hope S, et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:43. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCloskey EV, Vasireddy S, Threlkeld J, Eastaugh J, Parry A, Bonnet N, Beneton M, Kanis JA, Charlesworth D. Vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) with a densitometer predicts future fractures in elderly women unselected for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1561–1568. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schousboe JT, Lix LM, Morin SN, Derkatch S, Bryanton M, Alhrbi M, Leslie WD. Prevalent vertebral fracture on bone density lateral spine (VFA) images in routine clinical practice predict incident fractures. Bone. 2019;121:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson L, Sundh D, Magnusson P, Rukmangatharajan K, Mellstrom D, Nilsson AG, Lorentzon M. Grade 1 vertebral fractures identified by densitometric lateral spine imaging predict incident major osteoporotic fracture independently of clinical risk factors and bone mineral density in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35:1942–1951. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schousboe JT, Lix LM, Morin SN, Derkatch S, Bryanton M, Alhrbi M, Leslie WD. Vertebral fracture assessment increases use of pharmacologic therapy for fracture prevention in clinical practice. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:2205–2212. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leslie WD, Lix LM, Binkley N. Targeted vertebral fracture assessment for optimizing fracture prevention in Canada. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15:65. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00735-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Johansson H, Liu E, Vandenput L, Lorentzon M, Leslie WD, McCloskey EV. A decade of FRAX: how has it changed the management of osteoporosis? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01432-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, Burckhardt P, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/

- 26.Middleton RG, Shabani F, Uzoigwe CE, Shoaib A, Moqsith M, Venkatesan M. FRAX and the assessment of the risk of developing a fragility fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1313–1320. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B10.28889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cozadd AJ, Schroder LK, Switzer JA. Fracture risk assessment: an update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Harvey NC, Gudnason V, Sigurdsson G, Siggeirsdottir K, Lorentzon M, Liu E, Vandenput L, McCloskey EV. Adjusting conventional FRAX estimates of fracture probability according to the recency of sentinel fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31:1817–1828. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorentzon M, Nilsson AG, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Mellstrom D, Sundh D. Extensive undertreatment of osteoporosis in older Swedish women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:1297–1305. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-04872-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundh D, Mellstrom D, Nilsson M, Karlsson M, Ohlsson C, Lorentzon M. Increased cortical porosity in older men with fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1692–1700. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blake GM, Rea JA, Fogelman I. Vertebral morphometry studies using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Semin Nucl Med. 1997;27:276–290. doi: 10.1016/S0001-2998(97)80029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffith JF. Identifying osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5:592–602. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crans GG, Genant HK, Krege JH. Prognostic utility of a semiquantitative spinal deformity index. Bone. 2005;37:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerkeni S, Kolta S, Fechtenbaum J, Roux C. Spinal deformity index (SDI) is a good predictor of incident vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1547–1552. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller ML, Wang MC. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding of cervical spine fractures: implications for research using administrative databases. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2008;52:101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breslow NE, Day NE (1987) Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II--The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ 1–406. [PubMed]

- 38.Albertsson-Wikland K, Martensson A, Savendahl L, Niklasson A, Bang P, Dahlgren J, Gustafsson J, Kristrom B, Norgren S, Pehrsson NG, Oden A. Mortality is not increased in recombinant human growth hormone-treated patients when adjusting for birth characteristics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2149–2159. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Ogelsby AK. International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1237–1244. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Socialstyrelsen (2021) Nationella riktlinjer Målnivåer – vård vid rörelseorganens sjukdomar Målnivåer för indikatorer.

- 41.kunskapsstyrning Nsf, sjukvård H-o, samverkan Sri (2021) Konsekvensbeskrivning för personcentrerat och sammanhållet vårdförlopp Osteoporos - sekundärprevention efter fraktur.

- 42.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Cooper C, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Advisory Board of the National Osteoporosis Guideline G A systematic review of intervention thresholds based on FRAX: a report prepared for the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group and the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Arch Osteoporos. 2016;11:25. doi: 10.1007/s11657-016-0278-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1431–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Derivation and validation of updated QFracture algorithm to predict risk of osteoporotic fracture in primary care in the United Kingdom: prospective open cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e3427. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki T, Yoshida H. Low bone mineral density at femoral neck is a predictor of increased mortality in elderly Japanese women. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0970-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson H, Oden A, Kanis J, McCloskey E, Lorentzon M, Ljunggren O, Karlsson MK, Orwoll E, Tivesten A, Ohlsson C, Mellstrom D. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased mortality in elderly men: MrOS Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1411–1418. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV. Guidance for the adjustment of FRAX according to the dose of glucocorticoids. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:809–816. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCloskey EV, Oden A, Harvey NC, Leslie WD, Hans D, Johansson H, Kanis JA. Adjusting fracture probability by trabecular bone score. Calcif Tissue Int. 2015;96:500–509. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-9980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pothuaud L, Barthe N, Krieg MA, Mehsen N, Carceller P, Hans D. Evaluation of the potential use of trabecular bone score to complement bone mineral density in the diagnosis of osteoporosis: a preliminary spine BMD-matched, case-control study. J Clin Densitom. 2009;12:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCloskey EV, Oden A, Harvey NC, Leslie WD, Hans D, Johansson H, Barkmann R, et al. A meta-analysis of trabecular bone score in fracture risk prediction and its relationship to FRAX. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:940–948. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johansson H, Siggeirsdottir K, Harvey NC, Oden A, Gudnason V, McCloskey E, Sigurdsson G, Kanis JA. Imminent risk of fracture after fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:775–780. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, Bruyere O, Veronese N, Lorentzon M, Cooper C, et al. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05176-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, Karaplis AC, Lorentzon M, Thomas T, Maddox J, Fan M, Meisner PD, Grauer A. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1417–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kendler DL, Marin F, Zerbini CAF, Russo LA, Greenspan SL, Zikan V, Bagur A, et al. Effects of teriparatide and risedronate on new fractures in post-menopausal women with severe osteoporosis (VERO): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:230–240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Harvey NC, Lorentzon M, Liu E, Vandenput L, McCloskey EV. An assessment of intervention thresholds for very high fracture risk applied to the NOGG guidelines: a report for the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) Osteoporos Int. 2021;32:1951–1960. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-05942-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1215–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.11.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen ND, Jones G, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Asymptomatic vertebral deformity as a major risk factor for subsequent fractures and mortality: a long-term prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1349–1355. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delmas PD, Genant HK, Crans GG, Stock JL, Wong M, Siris E, Adachi JD. Severity of prevalent vertebral fractures and the risk of subsequent vertebral and nonvertebral fractures: results from the MORE trial. Bone. 2003;33:522–532. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Domiciano DS, Figueiredo CP, Lopes JB, Kuroishi ME, Takayama L, Caparbo VF, Fuller P, Menezes PF, Scazufca M, Bonfa E, Pereira RM. Vertebral fracture assessment by dual X-ray absorptiometry: a valid tool to detect vertebral fractures in community-dwelling older adults in a population-based survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:809–815. doi: 10.1002/acr.21905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.