Abstract

Background & Aims

We investigate interrelationships between gut microbes, metabolites, and cytokines that characterize COVID-19 and its complications, and we validate the results with follow-up, the Japanese 4D (Disease, Drug, Diet, Daily Life) microbiome cohort, and non-Japanese data sets.

Methods

We performed shotgun metagenomic sequencing and metabolomics on stools and cytokine measurements on plasma from 112 hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and 112 non–COVID-19 control individuals matched by important confounders.

Results

Multiple correlations were found between COVID-19–related microbes (eg, oral microbes and short-chain fatty acid producers) and gut metabolites (eg, branched-chain and aromatic amino acids, short-chain fatty acids, carbohydrates, neurotransmitters, and vitamin B6). Both were also linked to inflammatory cytokine dynamics (eg, interferon γ, interferon λ3, interleukin 6, CXCL-9, and CXCL-10). Such interrelationships were detected highly in severe disease and pneumonia; moderately in the high D-dimer level, kidney dysfunction, and liver dysfunction groups; but rarely in the diarrhea group. We confirmed concordances of altered metabolites (eg, branched-chain amino acids, spermidine, putrescine, and vitamin B6) in COVID-19 with their corresponding microbial functional genes. Results in microbial and metabolomic alterations with severe disease from the cross-sectional data set were partly concordant with those from the follow-up data set. Microbial signatures for COVID-19 were distinct from diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and proton-pump inhibitors but overlapping for rheumatoid arthritis. Random forest classifier models using microbiomes can highly predict COVID-19 and severe disease. The microbial signatures for COVID-19 showed moderate concordance between Hong Kong and Japan.

Conclusions

Multiomics analysis revealed multiple gut microbe-metabolite-cytokine interrelationships in COVID-19 and COVID-19related complications but few in gastrointestinal complications, suggesting microbiota-mediated immune responses distinct between the organ sites. Our results underscore the existence of a gut-lung axis in COVID-19.

Keywords: Gut Microbiome, Fecal Metabolome, Cytokine Storm, Gut-Lung Axis

Abbreviations used in this paper: 4D, Disease, Drug, Diet, Daily Life; AUC, area under the curve; BCAA, branched chain amino acid; BMI, body mass index; bp, base pairs; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; FDR, false discovery rate; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL, interleukin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; KO, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes orthology; NCGM, National Center for Global Health and Medicine; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; Spo2, saturation of peripheral oxygen; WBC, white blood cell

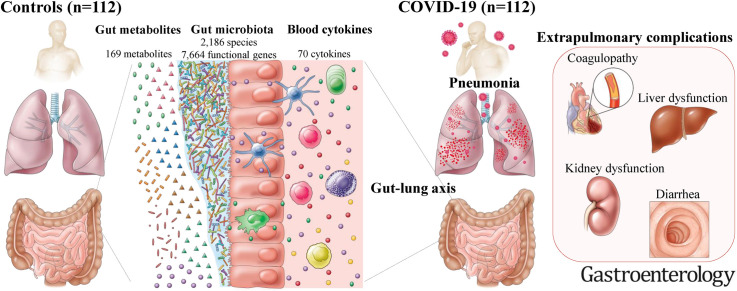

Graphical abstract

What You Need to Know.

Background and Context

Limited evidence exists linking specific gut microbiota–mediated host inflammatory responses to COVID-19 pathophysiology. Validation of microbial signatures with other disease cohorts and geographically distinct cohorts has not been performed.

New Findings

Gut microbiota-mediated amino acids, sugar metabolites, and neurotransmitters are involved in multiple cytokine dynamics in COVID-19. COVID-19–related microbes overlap with rheumatoid arthritis and are robust independent of geography.

Limitations

No animal experimental models were used to validate the detailed functions of the altered gut microbiota relating to COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Impact

The substantial number of participants and microbes, metabolites, and cytokines investigated here reveal a gut-lung axis in COVID-19. Numerous distinct microbe-metabolite-cytokine interrelationships in COVID-19 and its complications are identified.

The cytokine storm, an excessive inflammatory response initiated when SARS-CoV-2 enters alveolar epithelial cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors, is a major driver of COVID-19 pathogenesis.1 , 2 Gut microbiota involved in the development and functioning of the innate and adaptive immune systems3 potentially play a significant role in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Previous studies have suggested that short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)–producing microbiota are depleted in COVID-19 or severe disease4, 5, 6, 7 and are also linked to cytokine alterations.6, 7, 8 However, in part because of the small number of previously evaluated cytokines (≤7),6, 7, 8 our understanding of the microbe-host immune response landscape is still limited. Moreover, fecal metabolites provide a functional readout of microbial activity,9 , 10 and a few studies have shown some metabolites to be altered in COVID-19.6, 7, 8 Thus, comprehensive investigation of the interrelationships of gut microbes, metabolites, and cytokines, as they impact COVID-19, should expand our knowledge of disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, the host immune response and excessive inflammation may be implicated in coagulopathy, kidney dysfunction, liver dysfunction, and diarrhea, given the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in these tissues.2 However, microbiome-metabolome-cytokine relationships in such extrapulmonary complications remain uninvestigated. Identification of these interrelationships in COVID-19 and its complications can provide novel biomarkers and microbiome- or cytokine-based therapeutic targets for COVID-19.

Several issues for prior microbiome studies in COVID-194, 5, 6, 7, 8 remain to be overcome.11 First, patients’ backgrounds are confounders, affecting both microbiota and COVID-19 disease12 , 13; COVID-19 and control groups with balanced backgrounds are needed to identify the true associations between COVID-19 and the microbiome.14 Second, these backgrounds may influence microbiome-mediated host responses; thus, an examination of the interaction effects of backgrounds on COVID-19–related microbes is needed. Third, COVID-19–related microbes, including SCFA producers and oral microbes in the gut,4, 5, 6, 7, 8 are similar to those identified in other diseases and have not yet been validated among diseases. Finally, whether COVID-19–related microbes vary across countries remains unknown. If COVID-19–related microbes discriminate from other diseases and can be shared with other countries, this could be a useful screening tool.

To address these issues, we extensively investigated interrelationships among the gut microbes, metabolites, and cytokines that characterize COVID-19 and its complications, and we further validated the results with follow-up, other disease, and non-Japanese data sets.

Materials and Methods

Participant Recruitment and Sample Collection

The Japanese COVID-19 multiomics project, conducted with a cross-sectional and cohort study design, was constructed and participated in by Tokyo Medical University, the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM), the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), and the Institute of Health Sciences, Ezaki Glico Co, Ltd, whose medical ethics committees approved this project. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. Between March and December 2020, 112 COVID-19 adult (>20 years) patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and were hospitalized in the NCGM hospital were recruited. This is a part of the prospective sample collection conducted in the COVID-19 NCGM project, as previously described.15 All COVID-19 patients were Japanese and had not received a vaccine against COVID-19. Non–COVID-19 adult participants were recruited before the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan as a part of the Japanese 4D (Disease, Drug, Diet, Daily Life) microbiome project, which commenced in January 2015 and is ongoing.16, 17, 18 This project prospectively collected metadata and fecal samples from both healthy and diseased participants. Metadata include anthropometrics, smoking, alcohol, dietary habits, physical activities, diseases, and medications using self-reported questionnaires, face-to-face interviews, and physicians’ electronic medical records. Of these, we selected control individuals by matching (1:1 case/control ratio) for possible confounders for COVID-19 severity and gut microbiota,12 , 13 such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), alcohol, smoking, comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, etc), and drugs (antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors [PPIs], aspirin, etc). A total of 112 COVID-19 patients and 112 non–COVID-19 control individuals matched by baseline factors were included for analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

The clinical outcome of interest was COVID-19 severity. Severity was categorized into mild, moderate, severe, and critical as previously reported.15 Briefly, mild was defined as lack of respiratory symptoms, no pulmonary radiologic manifestations, and oxygen saturation (Spo 2) levels of ≥96%. Moderate was defined as mild respiratory symptoms, radiologic evidence of pneumonia, and 93% < Spo 2 < 96%. Severe disease were defined as Spo 2 of ≤93% and requiring oxygen support. Critical was defined as requiring heart-lung machine or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Other COVID-19–related extrapulmonary complications2 were also evaluated, such as high D-dimer levels (>1.0 mg/mL), kidney dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), liver dysfunction (all of the following are met: glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase of >38 U/L, glutamic pyruvic transaminase of >44 U/L, γ-glutamyl trans peptidase (GTP) of >80 U/L in men and γ-GTP of >30 U/L in women, and alkaline phosphatase of >113 U/L), and diarrhea defined as loose stools (Bristol scale of 6 or 7) or more than 3 loose or soft stools per day since onset.

The association between COVID-19 and its complications and gut microbiota, metabolites, and cytokines was analyzed in a cross-sectional data set (N = 224) in which information gathered up to the date of fecal collection was evaluated. The mean times to fecal and plasma collection after admission were 2.4 and 3.2 days, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). We also examined clinical outcomes after fecal collection using the COVID-19 follow-up data set (N = 112) to test whether patients with altered abundances in gut microbes and metabolites at baseline were at risk for developing disease status, such as pulmonary complications (any of the following are met: worsening Spo 2 of ≤93%, newly required oxygen support, or pneumonia development on imaging tests), cardiovascular/thrombotic events, and worsening laboratory data of white blood cell (WBC) count and D-dimer (defined by the difference between before and after fecal collection).

Because bowel-cleansing agents for colonoscopy and samples left over 24 hours can have profound effects on the gut microbiome and metabolome,19 , 20 feces were collected before bowel preparation for colonoscopy and were stored in the hospital at –80°C within 24 hours of defecation. We used feces without preservative media for metagenomic and metabolomic analysis because the media potentially affect metabolomic alterations.

Preparation of Fecal Samples and Fecal DNA Extraction

Aliquots (200 mg) of feces were mixed with 1200 μL methanol and filtered. The filtrate was centrifuged, and the supernatant (methanol extract) was used for metabolomics analysis. Fecal DNA was extracted from the pellet as previously described10 with slight modifications. The pellet of feces was subjected to cell lysis with lysozyme (Wako, 10 mg per sample), achromopeptidase (Wako, 1333 units per sample), sodium dodecyl sulfate (1%), and proteinase K (Merck, 0.67 mg per sample). DNA was collected using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and 2-propanol (Wako).

Fecal Metagenomic Analysis

After purification, DNA was prepared as a metagenomic shotgun library (insert size: 350 base pairs by using the ThruPLEX DNA-Seq kit (Takara). After quantifying the prepared DNA library by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, the DNA library was sequenced by using a NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system (150–base pair paired-end mode) (Illumina). We excluded 19 metagenomic samples because of a shortage of sequence of <10 million reads (n = 12) or library preparation failure (n = 7). In total, 273 metagenome samples were included in the analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Quality control of the metagenomic data was performed. Taxonomic profiles of the metagenomic samples were obtained with mOTUs2 version 2.6.1.21 MEGAHIT22 was used to assemble the quality-controlled reads, and Prodigal23 and CD-HIT24 were used to construct nonredundant gene sets. Functional profiles for the genes were performed using DIAMOND.25

Fecal Metabolomic Analysis

We followed the hydrophilic and SCFA metabolite extraction and measurement methods as previously described10 , 26 with minor modifications. The fecal hydrophilic metabolites were measured using both gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry platforms (Shimadzu). SCFAs were measured using a gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry platform. The spectral data were processed by LabSolutions Insight (Shimadzu). In the following functional analyses, the metabolites detected in more than 10% of participants were used.

Blood Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor Analysis

A total of 70 humoral factors in plasma (Supplementary Table 3) were quantified by the Bio-Plex 3D system (Bio-Rad) and an HISCL-5000 immunoassay analyzer (Sysmex Corp) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.15

Validation Disease Cohorts and a Distinct Geography Cohort

External metagenomic data sets from the Japanese 4D microbiome project16 were used. We created pairs of healthy groups with 7 diseases (rheumatoid arthritis [RA], collagen disease, PPIs, DM, corticosteroids, inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] while matching age, sex, and BMI factors between disease and heathy groups (Supplementary Table 4). We also used Hong Kong and US metagenomic data sets.6 , 27 To ensure similarity to the Japanese cohort, we used initial fecal data in COVID-19 (n = 100) and control participants (n = 78) and excluded patients younger than 15 years (n = 3) or those having fewer than 10 million reads (n = 19). A total of 88 COVID-19 patients and 68 control individuals were analyzed from the Hong Kong data set.6 We also used initial fecal data in mild (n = 5) and severe COVID-19 (n = 23) from the US data set.27

Correlation Analysis Between Multiomics Data and Statistical Analysis

In a cross-sectional study data set (N = 224), significant gut species and microbial functional genes were selected with MaAsLin2, and significant fecal metabolites and plasma cytokines were selected by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. COVID-19–related markers were considered significant if the false discovery rate (FDR) values were below 0.05; otherwise, P values below .05 were considered significant. Pairwise Spearman correlations were calculated with the function corr.test of the R package psych, version 2.1.6 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Heatmaps were drawn using the R package pheatmap, version 1.0.12. The metagenomic operational taxonomic units, fecal metabolites, and plasma cytokines were ordered by the number of significant correlations in the given column or row, and the metabolites were colored according to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Brite categories.

In a prospective cohort study data set (N = 112), we followed up COVID-19 patients from the index date (fecal collection) to the development of pulmonary complications, cardiovascular/thrombotic events, or worsening WBC or D-dimer level, and we censored patients at the time of discharge or death. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of each disease status. The relationship between gut species and metabolites at baseline and the development of disease status were selected with the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards models.

Transcript Profiling

All fecal metagenomic and metabolomic data in the COVID-19 patients and control individuals were deposited and are available in the DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL (accession number: DRA013706) and RIKEN Drop Met (accession number: DM0042), respectively.

Additional detailed methods are provided in the online Supplementary Methods.

Results

Distinct Gut Microbial Variations in COVID-19 and Background Factors

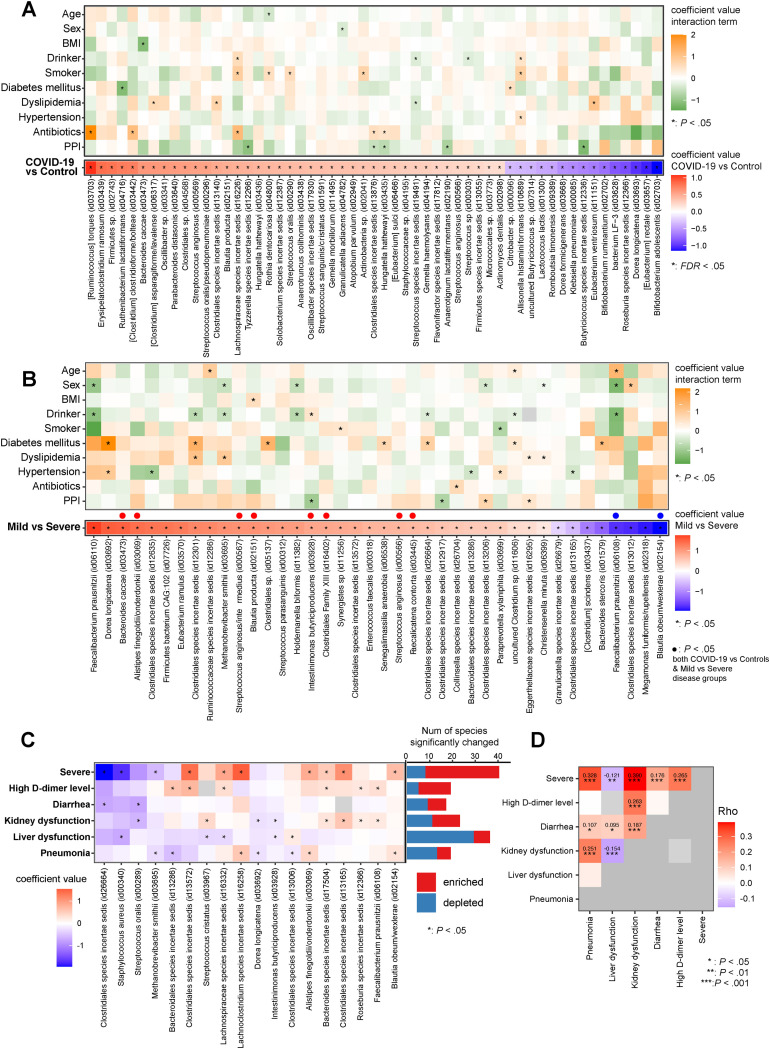

Baseline characteristics of anthropometrics, alcohol, smoking, comorbidities (eg, DM and dyslipidemia), and medication (eg, antibiotics and PPIs) were well balanced between the 112 COVID-19 patients and 112 control individuals (Supplementary Table 1). Between COVID-19 and control participants, Shannon diversity showed no significant differences, whereas Bray-Curtis dissimilarity displayed significant differences (Supplementary Figure 1 A and B). Although various metadata, such as smoking, sex, hypertension, age, BMI, and PPIs were significantly associated with microbial variations, COVID-19 had the largest explanatory power at the genus and species levels (Supplementary Figure 1 C). Between COVID-19 and control individuals, 156 species were significantly changed (P < .05, FDR < 0.16) (Supplementary Table 5), including marked enrichment of Ruminococcus torques and depletion of SCFA producers,28 including Bifidobacterium, Dorea, Roseburia, and Butyricicoccus species (FDR < 0.05) (Figure 1 A). Next, we sought to identify the effects of patient backgrounds on COVID-19–related microbes. Interaction term analyses revealed that only up to 9.1% (5 species) of 55 COVID-19–related microbes were interacted by background factors (Figure 1 A and Supplementary Table 6). Of these, smoking, antibiotics, and dyslipidemia significantly increase the abundances of some of the COVID-19–related microbes compared to those without them (Figure 1 A, orange), whereas PPI relative to non-PPI use significantly decreased the abundance of COVID-19–related microbes (Figure 1 A, green).

Figure 1.

Distinct gut microbial variations in COVID-19 and background factors. (A) Metagenomic data were obtained from COVID-19 patients (n = 103) and control individuals (n = 105). Red and blue in the lower heatmap represent species enriched and depleted between COVID-19 and control individuals (FDR < 0.05, MaAsLin2), respectively. The upper heatmap displays comparative analysis for COVID-19–related microbes between patients’ background factors, and an asterisk indicates microbes significantly interacting in the presence or absence of the factors (P < .05, MaAsLin2 interaction model). If the coefficient in the interaction term is greater than 0 (orange), the microbe’s abundance increases in the presence of the factor. A value less than 0 (green) means the microbe’s abundance decreases in the presence of the factor. (B) The lower heatmap shows the gut species significantly altered between mild and severe COVID-19 patients. Red and blue in the lower heatmap represent species enriched and depleted in the severe COVID-19 group (P < .05, MaAsLin2), respectively. The upper heatmap displays comparative analysis for severe-disease–related microbes between ‘background factors, and an asterisk indicates microbes significantly interacting in the presence or absence of the factors (P < .05, MaAsLin2 interaction model). (C) Association between gut microbiota and COVID-19 complications. We first identified gut microbes that significantly varied with each complication (P < .05, MaAsLin2) (Supplementary Table 7) and then created a heatmap of the microbes that overlap between 2 or more complications. Red and blue in the heatmap represent species enriched and depleted in each complication, respectively. Bar plots attached to the right side of the heatmap represent the number of gut species that were significantly enriched (red)/depleted (blue) between COVID-19 patients who had complications and those who did not. (D) Spearman rho values estimated by correlation analysis for coefficient values for gut species between 2 complications, shown as a heatmap. Red and purple indicate positive and negative correlations between complications, respectively.

Distinct Microbial Variations for COVID-19 Complications

Between mild and severe COVID-19 groups, we observed no significant differences in α-diversity but significant differences in β-diversity (Supplementary Figure 2 A and B), with 40 species significantly altered (Figure 1 B and Supplementary Table 7). Interaction term analyses indicate that drinking, diabetes, and sex affect severe-disease–related microbes to some extent, but antibiotics and PPI use have little impact (Figure 1 B and Supplementary Table 8). Between COVID-19 complications, we found differences of α- and β-diversity and microbial alterations (Supplementary Figure 2 A and B and Supplementary Table 7). The number and types of gut microbes significantly associated with each complication varied, with the highest number for severe disease and the lowest for the diarrhea group (Figure 1 C, bar plot). Between complications, overlapping microbes were limited, but some were detected (Figure 1 C), such as Methanobrevibacter smithii depleted in the severe disease and pneumonia groups. Distinct concordances of microbial signatures were observed between complications (Figure 1 D).

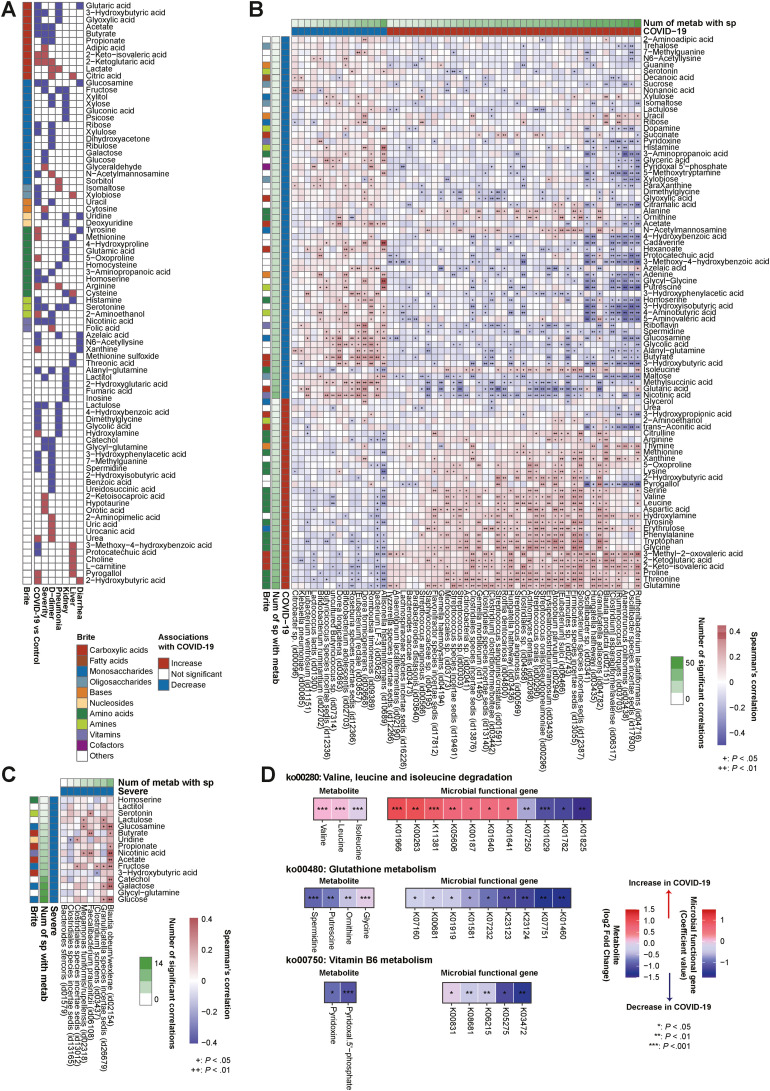

Relationships Between Gut Microbes, Microbial Functional Genes, and Metabolites in COVID-19 and Its Complications

A combination of target gas and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry techniques identified 169 fecal metabolites, of which 87 metabolites were significantly altered between COVID-19 and control individuals (FDR < 0.05) (Figure 2 A and B and Supplementary Table 9). Notably, of COVID-19–related enriched metabolites, 53% (16/30) were amino acids. Of these, glutamine, threonine, proline, glycine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, tyrosine, aspartic acid, leucine, and valine showed high numbers of significant correlations with gut microbes in this order (Figure 2 B). Importantly, amino acids were significantly associated positively with COVID-19–enriched microbes, primarily oral commensals29 such as Streptococcus, Rothia, and Actinomyces species, and negatively with COVID-19–depleted microbes, mainly SCFA producers28 (Figure 2 B). In contrast, COVID-19–related depleted metabolites included maltose, isomaltose, sucrose, glyoxylic acid, xylobiose, N-acetylmannosamine, glutaric acid, and SCFAs (acetate and butyrate), which are related to carbohydrate metabolism (Figure 2 A and B). Importantly, these carbohydrates were significantly associated positively with COVID-19–depleted microbes, mainly SCFA producers,28 and negatively with COVID-19–enriched microbes (Figure 2 B). Of note, neurotransmitters (eg, γ-aminobutyric acid, dopamine, and serotonin)30 and cofactors necessary for neurotransmitter synthesis (eg, pyridoxine and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate [vitamin B6]) were also significantly depleted in COVID-19 (Figure 2 A and B), all of which were associated positively with COVID-19–depleted microbes and negatively with COVID-19–enriched microbes (Figure 2 B). Collectively, microbiome and metabolome shifts were apparent between COVID-19 and control individuals, specifically distinct microbial patterns connected to specific metabolites such as amino acids, carbohydrates, and neurotransmitters.

Figure 2.

Gut microbe and metabolite relationships in COVID-19 and severe disease. (A) Fecal metabolomic data were obtained from COVID-19 patients (n = 112) and control individuals (n = 112). The heatmap shows the fecal metabolites significantly altered between COVID-19 patients and control individuals, patients with mild and severe COVID-19 (n = 112), high– and low–D-dimer groups (n = 94), pneumonia and nonpneumonia groups (n = 112), kidney dysfunction and non–kidney dysfunction groups (n = 111), liver dysfunction and non–liver dysfunction groups (n = 112), and diarrhea and nondiarrhea groups (n = 112). Associations found significant by Wilcoxon rank sum test (FDR < 0.05 in COVID-19 cases and P < .05 in other complications) are colored in red (increased in median) or blue (decreased in median). Fecal metabolites are colored according to KEGG Brite categories. (B) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between species-level microbiota relative abundance and fecal metabolite concentrations associated with COVID-19 patients and control individuals. Species (n = 208 cases) and fecal metabolites (n = 224 cases) for this analysis were selected through the MaAsLin2 model and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of green shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to gut metabolites, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of green shows the number of gut metabolites with significant correlations to gut species. The gut species and metabolites are ordered by their numbers of significant correlations. (C) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between the species-level microbiota relative abundance and fecal metabolite concentrations altered between patients with mild and severe COVID-19. Species (n = 103 cases) and fecal metabolites (n = 112 cases) for this analysis were selected through MaAsLin2 analysis (P < .05) and Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < .05), respectively. Overall correlations are displayed in Supplementary Figure 4A. Of these, we selected and showed correlations between depleted species and depleted fecal metabolites in severe COVID-19 cases. The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of green shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to gut metabolites, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of green shows the number of gut metabolites with significant correlations to gut species. Species and metabolites are ordered by their numbers of significant correlations. (D) The heatmap shows significantly altered gut metabolites and their corresponding KOs in representative KEGG pathways. We selected KEGG pathways belonging to the metabolites and KOs that were significantly associated with COVID-19. Among selected pathways, those with consistent signatures in KO genes and metabolites are shown in this heatmap. Num, number; sp, species.

Between COVID-19 complications, we found concordances and differences in metabolomic variations (Figure 2 A and Supplementary Figure 3). Importantly, SCFAs including acetate, butyrate, and propionate were significantly depleted in both severe and high–D-dimer groups as well as COVID-19. We confirmed that SCFAs were positively correlated with SCFA-producing bacteria28 such as Blautia species, Dorea species, Eubacterium species, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (Figure 2 B and C). Moreover, serotonin, nicotinic acid, 3-hydroxybutyric acid, lactulose, homoserine, and glucosamine were significantly reduced in both severe disease and COVID-19 (Figure 2 A and B). We found certain microbes significantly correlated with specific metabolites that differed according to organ disorder (Supplementary Material and Supplementary Figure 4).

Next, we examined whether altered gut metabolites translated into differences at functional levels, such as KEGG orthologies (KOs) and their corresponding pathways, by comprehensively profiling the functional capacity of the gut microbiome. Of 7664 KOs we profiled, 2248 KOs were significantly (P < .05) altered between COVID-19 and control individuals (Supplementary Table 10). In a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) degradation pathway, we found that BCAAs in the gut and their corresponding KOs were positively associated with COVID-19 (Figure 2 D). In the glutathione metabolism pathway, concordance of depleted spermidine, putrescine, ornithine, and glycine and their corresponding KOs in COVID-19 were observed. In vitamin B6 metabolism, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and pyridoxine in the gut and their corresponding KOs were commonly depleted in COVID-19. This result indicates that some gut metabolite variations detected in COVID-19 result from altered microbiome metabolism.

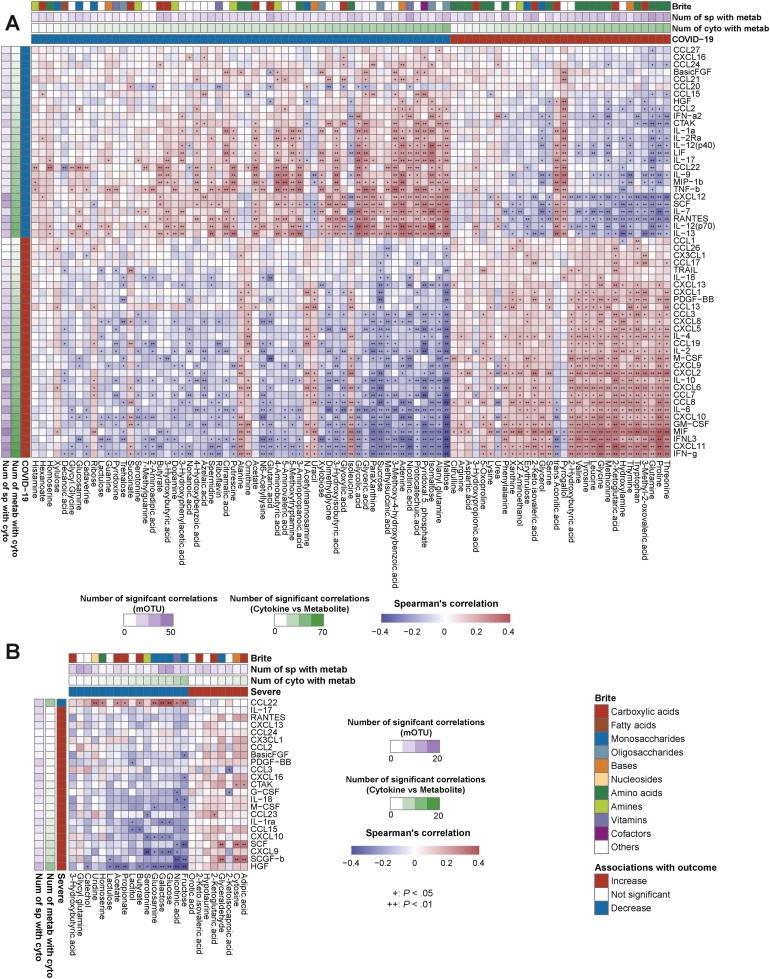

Interrelationships Between Microbiota, Metabolites, and Cytokines Are Associated With COVID-19 and Its Complications

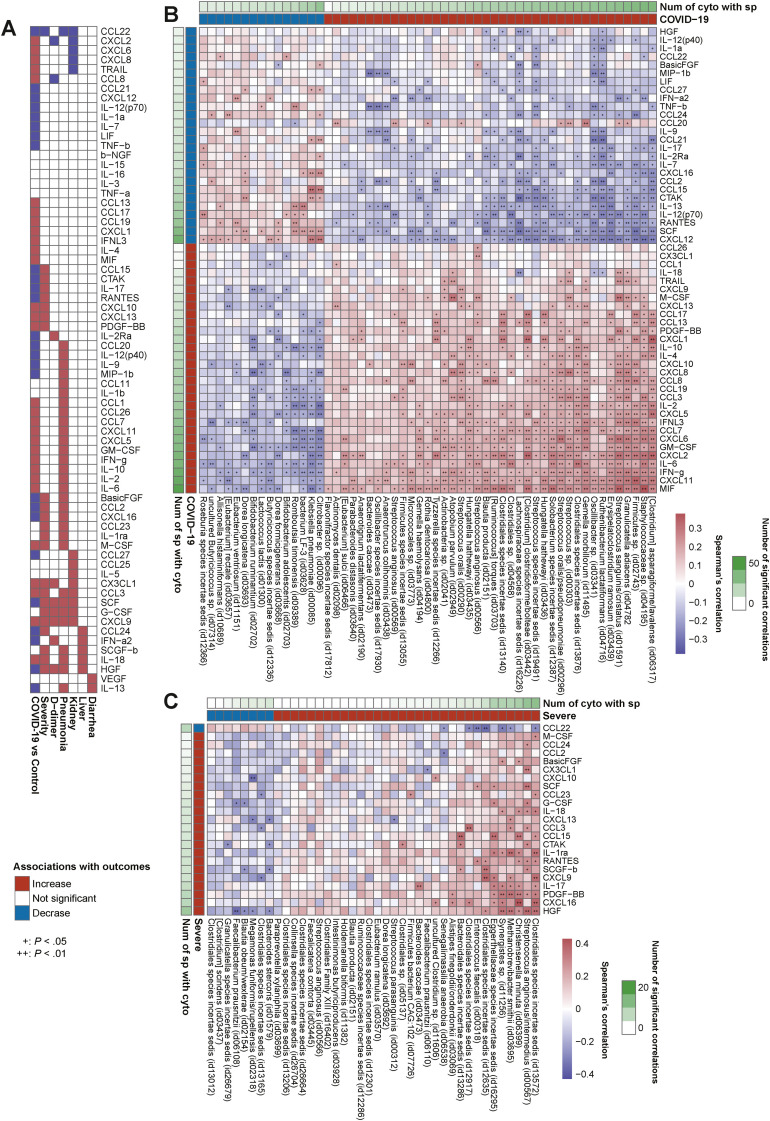

We investigated 70 blood cytokine/chemokine/growth factors (Supplementary Table 3) and found that COVID-19 presented significant elevation in 30 cytokines and depletion in 26 compared to controls (FDR < 0.05) (Figure 3 A and Supplementary Figure 5). Of note, interleukin (IL) 6, IL18, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL-13, CCL3, and GM-CSF, which are implicated in the cytokine storm,1 were elevated in COVID-19 and also significantly elevated in the severe group (Figure 3 A), whereas CCL22, involved in T-regulatory cell migration,31 decreased along with disease progression from control individuals to patients with mild and severe disease.

Figure 3.

Gut microbiota and blood cytokine relationships in COVID-19 and severe disease. (A) Plasma cytokine analysis was performed in COVID-19 patients (n = 70) and control individuals (n = 109). The heatmap shows the cytokines that were significantly altered between COVID-19 and control individuals, patients with mild and severe COVID-19 (n = 70), high– and low–D-dimer level groups (n = 60), pneumonia and nonpneumonia groups (n = 70), kidney dysfunction and non–kidney dysfunction groups (n = 69), liver dysfunction and non–liver dysfunction groups (n = 70), and diarrhea and nondiarrhea groups (n = 70). Associations found significant by Wilcoxon rank sum test (FDR < 0.05 in COVID-19 cases and P < .05 in other complications) are colored in red (increased in median) or blue (decreased in median). (B) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between the species-level microbiota relative abundance and plasma cytokine concentrations associated with COVID-19 patients and control individuals. Species (n = 208 cases) and cytokines (n = 179 cases) for this analysis were selected through the MaAsLin2 model and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively, with multiple testing corrections (FDR < 0.05). The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of green shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to cytokines, and the vertical heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of green shows the number of cytokines with significant correlations to gut species. Species and cytokines are ordered by their numbers of significant correlations. (C) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between the species-level microbiota relative abundance and plasma cytokine concentrations altered between mild and severe COVID-19 cases. Species (n = 103 cases) and cytokines (n = 70 cases) for this analysis were selected through the MaAsLin2 model (P < .05) and Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < .05), respectively. Species and cytokines are ordered by their numbers of significant correlations.

First, we sought to determine whether observed COVID-19–related microbes (40 enriched and 15 depleted [Figure 1 A]) were linked to the cytokine dynamics of the disease. Strikingly, of the enriched microbes, all (40/40) were significantly correlated positively with all of the cytokines significantly elevated in COVID-19 (Figure 3 B). In contrast, of the depleted microbes, 93.3% (14/15) were significantly correlated positively with all of the cytokines decreased in COVID-19 (Figure 3 B). These data strongly indicate that multiple unidirectional signatures of cytokines corresponding to gut microbial alterations can clearly discern COVID-19 vs controls.

Next, we sought to identify whether the gut microbiota-metabolite relationships were also linked to cytokine dynamics of COVID-19. We have shown that fecal amino acids elevated in COVID-19 were positively associated with COVID-19–enriched oral commensals (Figure 2 B). Importantly, both the oral commensals and amino acids also showed significant positive correlations with inflammatory cytokines elevated in COVID-19 (eg, interferon γ, IL6, CXCL9, and CXCL10), and negative correlations with cytokines decreased in COVID-19 (Figures 3 B and 4 A). Intriguingly, BCAAs, threonine, proline, and glutamine were all associated with the same gut microbial signatures (concordance rate > 72.7%) (Figure 2 B) and also exhibited the same inflammatory cytokine variation patterns (concordance rate > 80%) (Figure 4 A), implying the presence of specific metabolites involved with the same microbes and altering the same inflammatory response. These findings suggest that microbe-mediated amino acids may serve as drivers of inflammatory response in COVID-19 (Supplementary Material).

Figure 4.

Gut metabolite and blood cytokine relationships in COVID-19 and severe disease. (A) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between the plasma cytokine and fecal metabolite concentrations associated with COVID-19 patients and control individuals. Cytokines (n = 179 cases) and fecal metabolites (n = 224 cases) for this analysis were selected through Wilcoxon rank sum test with multiple testing corrections (FDR < 0.05). The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of green shows the number of gut metabolites with significant correlations to cytokines, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of green shows the number of cytokines with significant correlations to gut metabolites. The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of purple shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to cytokines, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of purple shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to gut metabolites. The cytokines and metabolites are ordered by their numbers of significant correlations in the given column or row, and metabolites are colored according to KEGG Brite categories. (B) The heatmap shows Spearman correlations between the plasma cytokine and fecal metabolite concentrations altered between mild and severe cases. Cytokines (n = 70 cases) and fecal metabolites (n = 112 cases) for this analysis were selected through Wilcoxon rank sum test (P < .05). The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of green shows the number of gut metabolites with significant correlations to cytokines, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of green shows the number of cytokines with significant correlations to gut metabolites. The vertical heatmap on the left displaying shades of purple shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to cytokines, and the horizontal heatmap at the top of the figure displaying shades of purple shows the number of gut species with significant correlations to gut metabolites. Metab, metabolites; cyto, cytokines.

In contrast, we have shown that fecal carbohydrate metabolites (eg, maltose, sucrose, and SCFAs) and neurotransmitters (eg, vitamin B6, γ-aminobutyric acid, dopamine, and serotonin),30 both of which were reduced in COVID-19, were positively associated with COVID-19–depleted SCFA-producing bacteria (Figure 2 B). Importantly, both microbes and metabolites also showed negative correlation with inflammatory cytokines elevated in COVID-19 and positive correlations with cytokines decreased in COVID-19 (eg, IL12, IL13, and CCL22) (Figures 3 B and 4A). Prior evidence and our results suggest that microbiota-mediated carbohydrates or neurotransmitters are potential regulators of COVID-19 (Supplementary Material). In addition, microbiota-metabolite-cytokine interrelationships were found in COVID-19 complications. Reflecting the cytokine alterations in each complication (Figure 3 A), the number of microbe- and metabolite-cytokine correlations were markedly high for the severe and pneumonia groups, moderate for the high–D-dimer, kidney dysfunction, and liver dysfunction groups, and extremely low in the diarrhea group (Figures 3 C and 4B; and Supplementary Figures 4, 6, 7; and Supplementary Material). Overall, these data suggest that microbiota-metabolite-cytokine interrelationships are involved in COVID-19 and its complications, particularly in the lungs, but not the gastrointestinal tract.

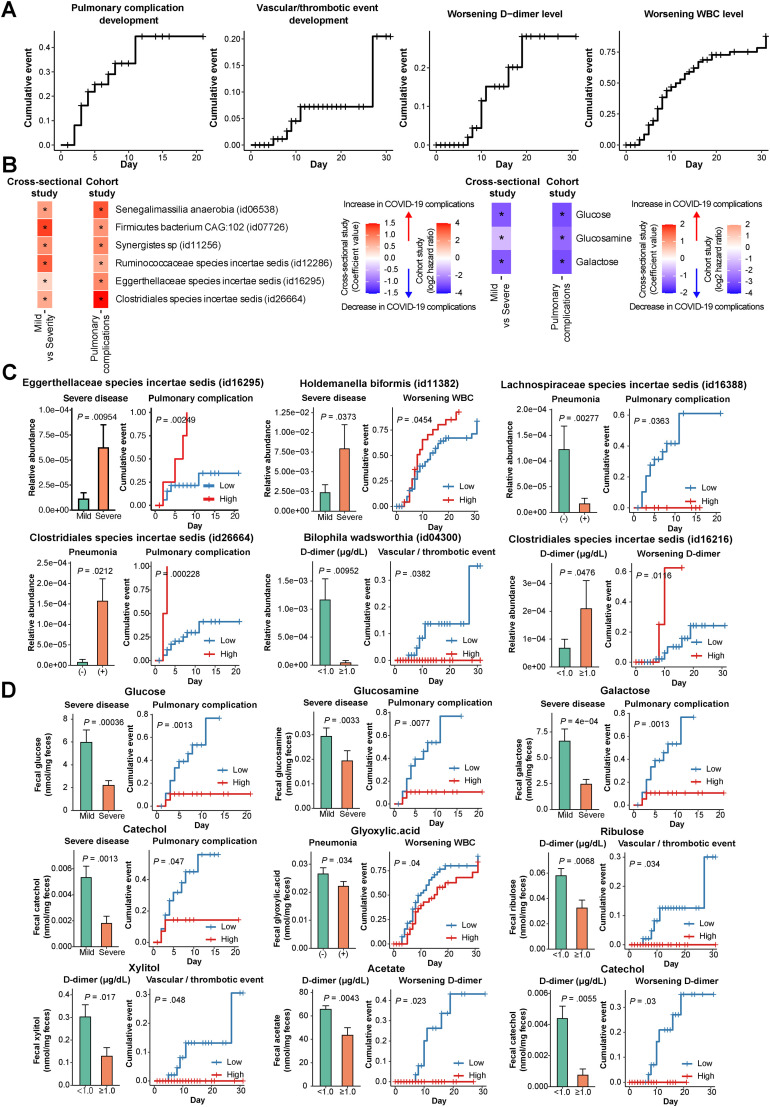

Follow-Up Data Analysis and Validation of Cross-Sectional Analysis in COVID-19

Follow-up (cohort study design) data could help differentiate whether COVID-19–altered gut microbiota and metabolites are secondary to outcomes or contribute to the development of the outcomes. Thus, we sought to examine whether patients with altered gut microbes and metabolites at baseline were at risk to develop disease status or worsened conditions after fecal collection and to confirm consistency with the association results from the cross-sectional data set up to the date of fecal collection. Kaplan-Meier curves showed the cumulative incidence of pulmonary complications, cardiovascular/thrombotic events, and worsening D-dimer and WBC levels (Figure 5 A). We confirmed the concordance of some gut microbial signatures between severe disease in the cross-sectional study (Figure 1 B) and pulmonary complication development or worsening WBC level in the cohort study (Figure 5 B and C). For example, the log-rank test revealed that Eggerthellaceae species (identification: 16295) showed higher abundance in severe disease compared to mild, whereas those with high abundance of the microbe at baseline were at significantly higher risk of subsequent pulmonary complication development (Figure 5 C). Similarly, microbial signatures in pneumonia and D-dimer levels in the cross-sectional study (Supplementary Table 7) were in agreement with the results from the cohort study, showing that patients with the same microbes were at risk of subsequent development of pulmonary complications, vascular/thrombotic events, and worsening D-dimer (Figure 5 C).

Figure 5.

Survival analysis and its concordance with cross-sectional analysis in patients with COVID-19. (A) The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of pulmonary complications (n = 41), cardiovascular/thrombotic events (n = 111), worsening D-dimer level (n = 91), and worsening WBC level (n = 112). Definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and follow-up of each cohort are described in the Supplementary Methods, Methods, and Supplementary Table 1. (B) The heatmaps show the concordance of gut microbial signatures between the cross-sectional study (red) and the cohort study (green). The left heatmap depicts 7 microbes enriched in severe COVID-19 in the cross-sectional study (red, MaAslin2, Figure 1B). In the cohort study, patients with high abundances of 6 microbes (id06538, id07726, id11256, id12286, id16295, and id26664) showed higher hazard ratios (HRs) for pulmonary complication development than those with low abundances (orange). Patients with high abundances of a microbe (id11382) showed higher HRs for worsening WBC level (green) in the cohort study. The right heatmap displays 3 metabolites (glucose, glucosamine, and galactose) depleted in severe COVID-19 in the cross-sectional study (purple, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Figure 2A). In the cohort study, patients with low abundances of the metabolites showed higher HRs for pulmonary complication development than those with low abundances (green). (C) The concordance of gut microbial signatures between the cross-sectional study (left bar) and the cohort study (right bar). The left bar represents the differences in abundances of gut microbes between COVID-19–related complications such as mild vs severe disease, pneumonia on computed tomography (CT) negative vs positive, and D-dimer level < 1.0 (μg/mL) vs ≥ 1.0. Comparison analysis was selected through MaAlsin2 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 7). Kaplan-Meier curves (right) show that patients with high or low abundances of the microbes were at higher risk of development of pulmonary complications, cardiovascular/thrombotic events, worsening D-dimer level, and worsening WBC level. Comparison analysis was selected through log-rank tests. (D) The concordance of gut metabolite alterations between the cross-sectional study (left bar) and the cohort study (right bar). The left bar chart represents the differences in abundances of gut metabolites between COVID-19–related complications such as mild vs severe disease, pneumonia on CT negative vs positive, and D-dimer level < 1.0 (μg/mL) vs ≥ 1.0. Comparison analysis was selected through the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Figure 2A). Kaplan-Meier curves (right) show that patients with high or low abundances of the metabolites were at higher risk of development of pulmonary complication, cardiovascular/thrombotic events, and worsening D-dimer level. Comparison analysis was selected through log-rank tests.

Altered gut metabolites (eg, glucose, glucosamine, galactose, and catechol) in severe disease from the cross-sectional study (Figure 2 A) were in concordance with the cohort study, revealing that patients with the same metabolites were at higher risk of pulmonary complication development (Figure 5 B and D). Similarly, cross-sectional study findings indicating that gut metabolites were altered in pneumonia and D-dimer level (Figure 2 A) were in concordance with those from the cohort study showing that patients with altered metabolite abundances were at risk of subsequent development of pulmonary complications, vascular/thrombotic events, and worsening D-dimer level (Figure 5 D). Collectively, some of the findings regarding microbial and metabolomic alterations associated with disease status seen in the cross-sectional study suggest that the altered microbes and metabolites may have contributed to the development of disease.

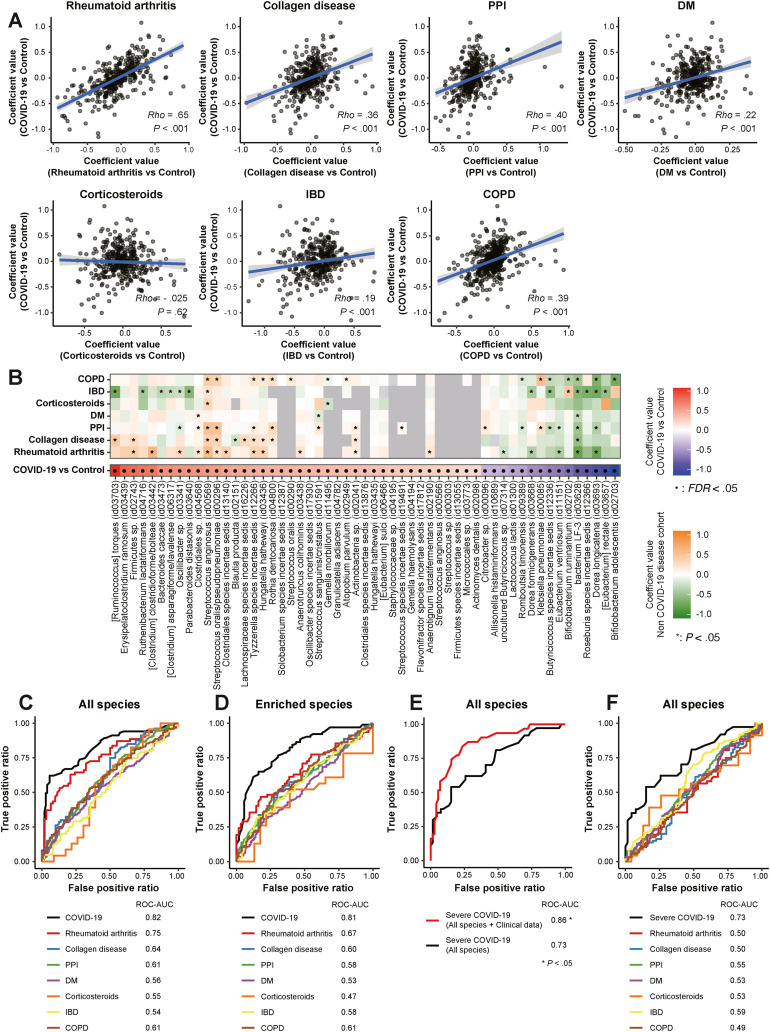

Microbial Signatures in Metagenomics Predicting COVID-19 and Their Specificity

Next, we sought to examine whether fecal microbiomes can serve as biomarkers to stratify patients at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19. Microbes associated with COVID-19 may be partially overlapping among different diseases and medications, such as depleted SCFA producers with immune diseases (eg, RA and IBD)1 , 32 and enriched oral microbes with PPIs.16 Thus, we developed machine-learning–based prediction models for COVID-19 and severe disease and examined whether the models can discriminate COVID-19 from other diseases using external Japanese 4D microbiome disease data sets (Supplementary Table 4).

Strengths of correlations (Spearman rho) in microbial signatures between COVID-19 and other diseases were low to moderate (Figure 6 A) for COVID-19 and collagen disease, PPIs, DM, corticosteroids, IBD, and COPD, but a high correlation existed with RA. RA had the most microbes shared with COVID-19, with 12 elevated and 5 decreased (Figure 6 B). Moreover, microbes that increased in both diseases were positively correlated with cytokines, which are all involved in RA disease activity and disease course, potentially inducing an inflammatory response (Supplementary Figure 8) (eg, CXCL8-11 and IL6),32 whereas those that decreased in both diseases were negatively correlated. Epidemiologic data indicate that RA was associated with a high risk of developing COVID-19 and severe disease.33 These parallels suggest that further studies may be warranted to determine whether RA and COVID-19 have similar pathogenesis through gut microbiota.

Figure 6.

Microbial signatures predicting COVID-19 and their specificity. (A) Concordance values for gut species between COVID-19 and 6 other disease data sets were calculated by Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Non–COVID-19 conditions included (1) patients with RA (n = 62) and healthy individuals (n = 62), (2) patients with collagen disease (n = 80) and healthy individuals (n = 80), (3) patients using PPIs (n = 387) and healthy individuals (n = 387), (4) patients with DM (n = 200) and healthy individuals (n = 200), (5) patients using corticosteroids (n = 23) and healthy individuals (n = 23), (6) patients with IBD (n = 124) and healthy individuals (n = 124), and (7) patients with COPD (n = 124) and healthy individuals (n = 124). The percentage of those aged ≥65 years, male, and with a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2 were equal between the 7 disease and healthy group pairs (Supplementary Table 4). Coefficient values for each microbial signature between COVID-19 and control individuals (MaAsLin2, x-axis) and between each disease and healthy control individuals (MaAsLin2, y-axis) are represented in a scatter. (B) Characteristics of gut microbial signatures for COVID-19 and several diseases. The left heatmap depicts 30 enriched species (red) and 25 depleted ones (blue) significantly altered between COVID-19 and control individuals (FDR < 0.05) (Figure 1A). The right heatmap shows species significantly (P < .05, MaAsLin2) enriched (orange) and depleted (green) between 7 disease patients and healthy control individuals . (C) Random forest classifiers constructing microbial models trained using all species (501 species) predicting COVID-19 and their application to non–COVID-19 diseases. The COVID-19 predictive model was compared to models predicting 7 diseases that were applied using the same microbes identified in the COVID-19 model, respectively. The AUC was estimated by random forest classifier. (D) Random forest classifiers constructing microbial models trained on species significantly enriched (101 species, P < .05, MaAsLin2) predicting COVID-19 and their application to non–COVID-19 diseases. (E) Random forest classifiers construct microbial models predicting severe COVID-19. The AUC was estimated by random forest classifier. The prediction models were trained using all species (488 species) in mild vs severe COVID-19 (P < .05, MaAsLin2). The basic severe COVID-19 predictive microbial model was compared to the model using microbiomes and known clinical risk factors for severe disease, such as age >65 years, sex, BMI of >25 kg/m2, the number of comorbidities, and the number of drugs taken, as well as the laboratory data of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (U/L) and WBC/mm3 at admission. (F) The basic severe COVID-19 predictive model compared to models predicting 7 diseases applied using the same microbes identified in the severe COVID-19 model. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Next, we built random forest classifier–based COVID-19 prediction models and determined the possibility of misclassifying COVID-19 by applying COVID-19 models to 7 disease data sets. The classifiers reached high values of area under the curve (AUC) for the prediction of COVID-19 (Figure 6 C). AUC in COVID-19 showed higher values than for other diseases but not different for RA, suggesting that RA can be misclassified as COVID-19. To improve the specificity, we next focused only on species enriched in COVID-19. The AUC in COVID-19 was lower in RA and other diseases (Figure 6 D). The AUC in severe COVID-19 was relatively high and significantly increased when adding known clinical risk factors (Figure 6 E). Moreover, the AUC in severe COVID-19 was higher than for the other 7 diseases (Figure 6 F). These data indicate that our microbial models can serve as diagnostic tools for predicting COVID-19 and severe disease and can also discriminate COVID-19 from other diseases.

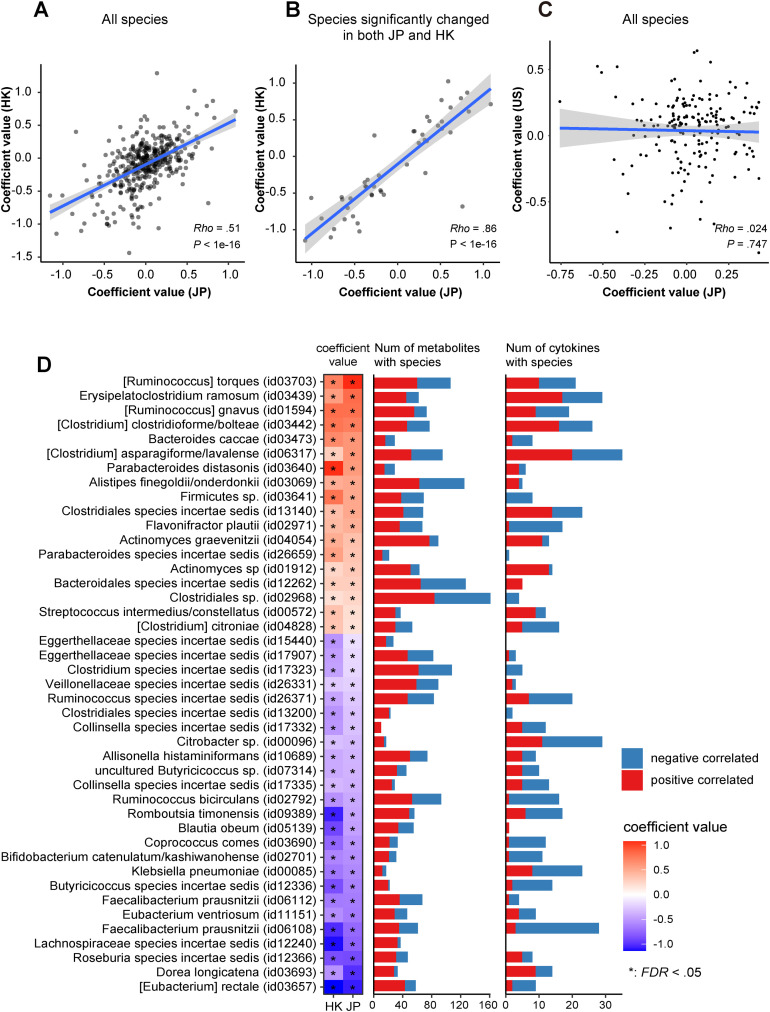

Validation of Japanese Results With Hong Kong and US Data

To confirm the validity of the microbial alterations identified in this study (Japanese cohort), we employed external metagenomic data sets from a Hong Kong cohort (N = 88)6 and a US cohort (N = 28)27 analyzed with the same pipeline used for the Japanese cohort. Strength of correlation in microbial signatures for COVID-19 between the Japanese and Hong Kong cohorts was moderate (ρ = 0.51) (Figure 7 A). Of the microbes significantly changed between COVID-19 and control individuals, the severe group also showed 10 microbial alterations (8 enriched and 2 depleted) (Figure 1 B). Between COVID-19 and control individuals, 164 microbes changed significantly (Supplementary Table 11). When focusing on the 47 COVID-19–related species (P < .05) identified in both the Japanese and Hong Kong cohorts, strength of correlation was higher (ρ = 0.86) (Figure 7 B). Of these, 43 species (18 enriched and 25 depleted) had the same directional signature between the countries and also had high numbers of correlations with gut metabolites and cytokines (Figure 7 D). We hypothesized that the concordance of gut microbial signatures for COVID-19 is due to the similarity of gut commensals between individuals from the Japanese and Hong Kong cohorts. However, significant differences in the gut microbiomes of healthy participants were observed between the countries (Supplementary Figure 9). However, severe-COVID-19–related microbial signatures between the Japanese and US cohorts were extremely poor in agreement (Figure 7 C and Supplementary Figure 10). Collectively, our data highlighted that overlapping microbial signatures for COVID-19 exist between the Asian countries, independent of geographic microbial differences.

Figure 7.

Validation of microbial signatures for COVID-19 in Japan with Hong Kong and the United States. (A) A scatterplot showing coefficient values for gut microbial signatures for COVID-19 identified in Japan (JP) (x-axis) and Hong Kong (HK) (y-axis), respectively. Coefficient values of 501 gut microbial alterations were estimated from MaAsLin2 between COVID-19 and control individuals. Concordance values for gut species for COVID-19 between Japan and Hong Kong were calculated by Spearman rank correlation coefficient. (B) A scatterplot depicting 47 species significantly (P < .05) altered in COVID-19 in both the and Hong Kong cohorts. (C) A scatterplot showing coefficient values for gut microbial signatures for severe COVID-19 identified in Japan (x-axis) and the United States (y-axis), respectively. (D) The left heatmap depicts 43 microbes, 18 enriched (red) and 25 depleted (blue), in COVID-19 that overlapped between Japan and Hong Kong among the 156 species characterized in COVID-19 in the Japanese cohort (P < .05, FDR < 0.16, MaAsLin2). The bar plot represents the number of cytokines and metabolites in the Japanese cohort that were significantly (P < .05, Spearman) correlated with the 43 species. The number of positive and negative correlations is represented in red and blue, respectively.

Discussion

In our study, the numbers of participants (N = 224) and phenotype markers (2186 species, 7664 KO genes, 169 gut metabolites, and 70 blood cytokines) analyzed were substantially larger than those of previous studies.4, 5, 6, 7 Owing to this, we identified multiple correlations between COVID-19–related gut microbes (eg, oral microbes, SCFA producers, and Bifidobacterium and Oscillibacter species) and gut metabolites (eg, branched-chain and aromatic amino acids, carbohydrates, neurotransmitters, and vitamin B6) (Figure 1, Figure 2). Importantly, both were linked to marked dynamics of inflammatory cytokines, demonstrating an intimate triangular relationship existing in COVID-19 (Figure 3, Figure 4). Such relationships were highly visible in severe disease and pneumonia; partly detected in groups with high D-dimer levels, kidney dysfunction, and liver dysfunction; but little present in the diarrhea group. Furthermore, observed associations of microbes and metabolites with severe disease in the cross-sectional data were in concordance with follow-up data showing that altered microbial and metabolomic abundances at baseline indicated risk of pulmonary complications (Figure 5). Overall, these data highlighted the existence of a gut-lung axis in COVID-19 and distinct microbiota-mediated immune responses between the organ sites.

Clinically, fecal microbiomes could serve as noninvasive biomarkers to stratify patients at high risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19. Making use of 3 validation scenarios, to our knowledge, we are the first to develop machine-learning–based prediction models for COVID-19 using microbiomes. First, random forest classifiers revealed that gut microbiomes can predict COVID-19 and severe COVID-19 with relatively high accuracy (Figure 6). Moreover, the addition of known clinical risk factors to the model for severe COVID-19 further increases its accuracy (Figure 6 E). SARS-CoV-2 infection risk is thought to be determined by individual behavioral factors. The use of microbiome models for COVID-19 may be a useful tool to assess susceptibility to the infection. Second, the models can clearly distinguish COVID-19 or severe COVID-19 from other diseases, suggesting that the models are specific to COVID-19. This microbiome approach to determine disease specificity, incorporating a variety of diseases, has been used in the prediction of cancer17 , 34 but not for COVID-19. Third, we propose geographic applicability of this model. Moderate concordance of the COVID-19–related microbial signatures between the Hong Kong and Japanese cohorts suggests that this model could be used in Asia; however, poor concordance of severe-COVID-19–related microbial signatures between the Japanese and US cohorts was observed (Figure 7). Epidemiologic data indicate significant differences in COVID-19–related deaths between Japan and the United States (Supplementary Figure 10), and microbial differences might be among the reasons for this.

Because COVID-19 is characterized by hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, which is closely associated with poor prognosis,1 , 35 a comprehensive understanding of cytokine dynamics and its link to the gut microbiome in COVID-19 can help us develop better strategies to effectively control immunopathology in infectious and inflammatory diseases.35 Therapies inhibiting cytokines have been used in clinical practice, but an approach that controls biomarkers upstream in cytokine alterations has not been developed. Our analyses revealed specific gut microbiota that were apparently linked to cytokine dynamics (Figures 3 and 4), suggesting that therapies that inhibit or enhance certain microbiota, such as probiotics, prebiotics, and bacteriophages,17 , 18 can play adjunctive roles in the treatment of COVID-19 through inflammatory cytokine inhibition. Our study provided detailed fundamental data for future research in immunomodulator therapy for COVID-19.

This study has some limitations. First, we could not identify causal relationships between COVID-19 pathogenesis and gut markers using functional or mechanistic data. Second, to control for all the confounders of severe illness, a non–COVID-19 control group, such as hospitalized patients with severe pneumonia, is needed, but we could not include one.

In summary, gut microbiota-mediated metabolites, specifically amino acids, sugar metabolites, and neurotransmitters, were associated with immune response to COVID-19. Their identification can provide new insights into pathogenesis along the gut-lung axis and extrapulmonary complications. Our deep analyses have unveiled extensive microbe-metabolite-cytokine relationships that could serve as a catalog for understanding the pathogenesis of COVID-19 as well as other immune-related or infectious disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suguru Nishijima for support and advice on analyzing the fecal metagenomic data profile in the Japanese 4D microbiome cohort; Gen Kaneko and Thane Doss for editing the manuscript; Maki Nagashima, Masami Kurokawa, and Ataru Moriya for supporting sample collection; Y. Sakurai and I. Hojo for DNA extraction from fecal samples; and A. Ito for metabolome analysis. The supercomputing resource was provided by the Human Genome Center (University of Tokyo).

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Naoyoshi Nagata, PhD, MD (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Validation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead); Tadashi Takeuchi, MD, PhD (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Lead; Writing – original draft: Equal); Hiroaki Masuoka, PhD (Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Software: Lead; Writing – original draft: Equal); Ryo Aoki, MS (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Software: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal); Masahiro Ishikane, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Noriko Iwamoto, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Masaya Sugiyama, PhD (Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Wataru Suda, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Yumiko Nakanishi, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Junko Terada-Hirashima, MD, MPH (Data curation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Moto Kimura, PhD (Funding acquisition: Lead; Supervision: Equal; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Tomohiko Nishijima, PhD (Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Hiroshi Inooka, PhD (Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Tohru Miyoshi-Akiyama, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Yasushi Kojima, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Chikako Shimokawa, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting); Hajime Hisaeda, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting); Fen Zhang, PhD (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Yun Kit Yeoh, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Naomi Uemura, MD, PhD (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Takao Itoi, MD, PhD (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Masashi Mizokami, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Takashi Kawai, MD, PhD (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Haruhito Sugiyama, MD, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Norio Ohmagari, MD, MSc, PhD (Data curation: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting); Hiroshi Ohno, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Supervision: Equal; Writing – original draft: Supporting).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Naoyoshi Nagata, Wataru Suda, Moto Kimura, and Hiroshi Ohno received a grant from Ezaki Glico Co, Ltd. Ryo Aoki, Tomohiko Nishijima, and Hiroshi Inooka are employees of Ezaki Glico Co, Ltd. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was partially supported by grants from Ezaki Glico Co, Ltd; Grants-in-Aid for Research from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (28-2401); a JSPS KAKENHI grant (JP17K09365 and 20K08366); the Takeda Science Foundation; COCKPIT funding; the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP20fk0108416); The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (22HB1003); the RIKEN President’s Discretionary Funds; and the RIKENIMS Center Director’s Discretionary Budget, Japan. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.024.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wang J., Jiang M., Chen X., et al. Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of 3939 COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;108:17–41. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng D., Liwinski T., Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020;30:492–506. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuo T., Zhang F., Lui G.C.Y., et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:944–955. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu S., Chen Y., Wu Z., et al. Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 or H1N1 influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2669–2678. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeoh Y.K., Zuo T., Lui G.C.-Y., et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021;70:698–706. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang F., Wan Y., Zuo T., et al. Prolonged impairment of short-chain fatty acid and L-isoleucine biosynthesis in gut microbiome in patients with COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:548–561. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lv L., Jiang H., Chen Y., et al. The faecal metabolome in COVID-19 patients is altered and associated with clinical features and gut microbes. Anal Chim Acta. 2021;1152 doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zierer J., Jackson M.A., Kastenmüller G., et al. The fecal metabolome as a functional readout of the gut microbiome. Nat Genet. 2018;50:790–795. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi T., Miyauchi E., Kanaya T., et al. Acetate differentially regulates IgA reactivity to commensal bacteria. Nature. 2021;595(7868):560–564. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P., Roper J. Gut microbiome composition is associated with COVID-19 disease severity. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:722–724. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee A., Pasea L., Harris S., et al. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1715–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt T.S.B., Raes J., Bork P. The human gut microbiome: from association to modulation. Cell. 2018;172:1198–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vujkovic-Cvijin I., Sklar J., Jiang L., et al. Host variables confound gut microbiota studies of human disease. Nature. 2020;587:448–454. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2881-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama M., Kinoshita N., Ide S., et al. Serum CCL17 level becomes a predictive marker to distinguish between mild/moderate and severe/critical disease in patients with COVID-19. Gene. 2021;766 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata N., Nishijima S., Miyoshi-Akiyama T., et al. Population-level metagenomics uncovers distinct effects of multiple medications on the human gut microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1038–1052. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata N., Nishijima S., Kojima Y., et al. Metagenomic identification of microbial signatures predicting pancreatic cancer from a multinational study. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:222–238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishijima S., Nagata N., Kiguchi Y., et al. Extensive gut virome variation and its associations with host and environmental factors in a population-level cohort. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5252. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32832-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata N., Tohya M., Fukuda S., et al. Effects of bowel preparation on the human gut microbiome and metabolome. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagata N., Tohya M., Takeuchi F., et al. Effects of storage temperature, storage time, and Cary-Blair transport medium on the stability of the gut microbiota. Drug Discov Ther. 2019;13:256–260. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2019.01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milanese A., Mende D.R., Paoli L., et al. Microbial abundance, activity and population genomic profiling with mOTUs2. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1014. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08844-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li D., Liu C.-M., Luo R., et al. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1674–1676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyatt D., Chen G.-L., LoCascio P.F., et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu L., Niu B., Zhu Z., et al. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchfink B., Xie C., Huson D.H., et al. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato K., Yamazaki K., Kato T., et al. Obesity-related gut microbiota aggravates alveolar bone destruction in experimental periodontitis through elevation of uric acid. MBio. 2021;12(3) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00771-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Britton G.J., Chen-Liaw A., Cossarini F., et al. Limited intestinal inflammation despite diarrhea, fecal viral RNA and SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA in patients with acute COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92740-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghimire S., Roy C., Wongkuna S., et al. Identification of Clostridioides difficile-inhibiting gut commensals using culturomics, phenotyping, and combinatorial community assembly. mSystems. 2020;5(1) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00620-19. e00620-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X., Tong X., Zhu J., et al. Metagenome-genome-wide association studies reveal human genetic impact on the oral microbiome. Cell Discov. 2021;7(1):117. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00356-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fung T.C., Olson C.A., Hsiao E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:145–155. doi: 10.1038/nn.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapp M., Wintergerst M.W.M., Kunz W.G., et al. CCL22 controls immunity by promoting regulatory T cell communication with dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1170–1181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elemam N.M., Hannawi S., Maghazachi A.A. Role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunotargets Ther. 2020;9:43–56. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S243636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.England B.R., Roul P., Yang Y., et al. Risk of COVID-19 in rheumatoid arthritis: a national Veterans Affairs matched cohort study in at-risk individuals. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:2179–2188. doi: 10.1002/art.41800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeller G., Tap J., Voigt A.Y., et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10(11):766. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang L., Xie X., Tu Z., et al. The signal pathways and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):255. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.