Abstract

Previously, we screened the symbiotic gene region of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum chromosome for new NifA-dependent genes by competitive DNA-RNA hybridization (A. Nienaber, A. Huber, M. Göttfert, H. Hennecke, and H. M. Fischer, J. Bacteriol. 182:1472–1480, 2000). Here we report more details on one of the genes identified, a hemN-like gene (now called hemN1) whose product exhibits significant similarity to oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenases involved in heme biosynthesis in facultatively anaerobic bacteria. In the course of these studies, we discovered that B. japonicum possesses a second hemN-like gene (hemN2), which was then cloned by using hemN1 as a probe. The hemN2 gene maps outside of the symbiotic gene region; it is located 1.5 kb upstream of nirK, the gene for a Cu-containing nitrite reductase. The two deduced HemN proteins are similar in size (445 and 450 amino acids for HemN1 and HemN2, respectively) and share 53% identical (68% similar) amino acids. Expression of both hemN genes was monitored with the help of chromosomally integrated translational lacZ fusions. No significant expression of either gene was detected in aerobically grown cells, whereas both genes were strongly induced (≥20-fold) under microaerobic or anaerobic conditions. Induction was in both cases dependent on the transcriptional activator protein FixK2. In addition, maximal anaerobic hemN1 expression was partially dependent on NifA, which explains why this gene had been identified by the competitive DNA-RNA hybridization approach. Strains were constructed carrying null mutations either in individual hemN genes or simultaneously in both genes. All mutants showed normal growth in rich medium under aerobic conditions. Unlike the hemN1 mutant, strains lacking a functional hemN2 gene were unable to grow anaerobically under nitrate-respiring conditions and largely failed to fix nitrogen in symbiosis with the soybean host plant. Moreover, these mutants lacked several c-type cytochromes which are normally detectable by heme staining of proteins from anaerobically grown wild-type cells. Taken together, our results revealed that B. japonicum hemN2, but not hemN1, encodes a protein that is functional under the conditions tested, and this conclusion was further corroborated by the successful complementation of a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium hemF hemN mutant with hemN2 only.

Heme compounds represent a ubiquitous, iron-containing subclass of biological tetrapyrroles. In association with specific apoproteins, they serve a wide range of important functions including electron transport (e.g., cytochromes), binding and transport of O2 (e.g., hemoglobin), and oxidative catalysis (e.g., peroxidases). The universal tetrapyrrole precursor δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is synthesized by either one or the other of two distinct pathways (for reviews, see references 9 and 41). Plants, algae, archaea, and most eubacteria (including enteric bacteria) use the so-called glutamate (C5) pathway, which includes reduction of tRNA-bound glutamyl by glutamyl-tRNA reductase. Nonplant eukaryotes and members of the α subgroup of proteobacteria (including the rhizobia) synthesize ALA via condensation of glycine and succinyl coenzyme A (CoA) by ALA synthase (Shemin pathway). Subsequently, ALA is converted to protoheme in seven successive enzymatic reactions which are identical in both classes of organisms. Depending on the cellular oxygen conditions, the fifth reaction of this sequence, namely, the oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX, is catalyzed by different enzymes in facultatively aerobic bacteria. Under aerobic conditions, the oxidation is performed by coproporphyrinogen III oxidase (e.g., the product of the Escherichia coli hemF gene), which uses molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor. In the absence of oxygen, the reaction is catalyzed by the structurally unrelated coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenase, whose activity requires NADP+, ATP, Mg2+, and l-methionine. Corresponding genes (commonly named hemN) have been cloned from a number of bacteria such as E. coli (70), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (73), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (63), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (18), and Ralstonia eutropha (46).

Bacterial heme synthesis is subject to multiple controls by the availability of oxygen, iron, and/or heme. Regulation in response to cellular oxygen conditions was observed predominantly at two steps, namely, ALA synthesis and oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III. Regardless of the pathway used for ALA synthesis, expression of the respective genes was elevated in various bacterial species when they were grown under low-oxygen conditions (20, 40, 56). Similarly, expression of the hemN genes from E. coli, R. eutropha, and P. aeruginosa is increased under anaerobic conditions, which is understandable in the light of the oxygen-independent reaction catalyzed by the HemN protein (46, 63, 70).

In our laboratories, we are studying the gram-negative soil bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum, which can exist as a free-living organism or as a nitrogen-fixing root nodule symbiont of its soybean host plant. The switch between the different lifestyles requires a high degree of physiological flexibility. For example, B. japonicum induces the synthesis of a cbb3-type, high-affinity terminal oxidase (FixNOQP) during the infection process in order to cope with the microaerobic conditions prevailing in the infected host plant tissue (for a review, see reference 36). Coordinated expression of symbiotic genes is brought about by the concerted action of two largely independent regulatory cascades which both respond to cellular oxygen conditions (8, 52; for reviews, see references 22 and 23). In the FixLJ-FixK2 cascade, the low-oxygen signal is detected and transduced by the FixLJ two-component regulatory system, whereas NifA fulfills the same function in the RegSR-NifA cascade. The signal for the superimposed RegSR two-component regulatory system is not known at present. Transcriptional activation of target genes by NifA involves a specialized RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing the alternative ς factor RpoN (ς54 or ςN), which enables recognition of −24/−12-type promoters (for a review, see reference 21).

In a recent study, Nienaber and coworkers used a DNA-RNA hybridization approach for a global survey of the regulatory function of NifA with regard to the so-called symbiotic gene region of the B. japonicum chromosome (53). This DNA region of about 400 kb comprises a large number of genes concerned with nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation (45). Using this strategy, we have identified several new NifA-regulated genes, including nrgA and nrgBC, whose functions are unknown, and, interestingly, a hemN-like gene. Thus it appeared that regulation of symbiotic genes and a key heme biosynthetic gene was linked in B. japonicum via NifA, which would make perfect sense in view of the de novo synthesis of heme proteins during the transition from the free-living to the symbiotic state. However, we present evidence here that the previously identified hemN gene (hemN1) is not functional under the conditions tested and that its regulation also involves the FixLJ-FixK2 cascade in addition to NifA. Moreover, we report on the identification and characterization of a second hemN gene (hemN2) which is essential for anaerobic heme biosynthesis in B. japonicum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Bethesda Research Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md. |

| S17-1 | Smr SprhsdR (RP4-2 kan::Tn7 tet::Mu, integrated in the chromosome) | 67 |

| 294 cys::Tn5 | Kmrcys::Tn5 | 30 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium TE3006 | Kmr TcrhemN704::Mud-J(b) hemF707::Tn10d-Tet | 72 |

| B. japonicum | ||

| 110spc4 | Spr wild type | 62 |

| A9 | Spr KmrnifA::aphII | 24 |

| 9043 | Spr SmrfixK2::Ω | 52 |

| 8244 | Spr Kmr SmrhemN1::Tn5 | This work |

| GRN307 | Spr SmrhemN2::Ω | This work |

| 8275 | Spr TcrhemN2::pSUP202pol4 | This work |

| 8275-44 | Spr Kmr Smr TcrhemN1::Tn5 hemN2::pSUP202pol4 | This work |

| 8246a | Spr TcrhemN1′-′lacZ chromosomally integrated | This work |

| 8281a | Spr TcrhemN2′-′lacZ chromosomally integrated | This work |

| 8294-1 | Spr Smr Tcr GRN307 with chromosomally integrated pRJ8294 | This work |

| 8295-4 | Spr Smr Tcr GRN307 with chromosomally integrated pRJ8295 | This work |

| 8296 | Spr Smr Tcr GRN307 with chromosomally integrated pRJ8296 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Apr cloning vector | 54 |

| pUCBM21 | Apr cloning vector | Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany |

| pSUP202 | Apr Cmr Tcr; oriT from RP4 | 67 |

| pSUP202pol4 | Tcr (pSUP202) part of polylinker from pBluescript II KS(+) between EcoRI and PstI | 25 |

| pSUP202pol6K | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) KpnI linker inserted into SmaI site | 75 |

| pBSL86 | Apr Kmr | 1 |

| pHP45::Ω | Apr Smr Spr | 61 |

| pNM482 | Apr (pUC8) ′lacZ | 49 |

| pSUP480 | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) ′lacZ | H. M. Fischer, unpublished data |

| pRJ8224 | Apr (pUC18) B. japonicum hemN1 on an 8.1-kb EcoRI fragment | This work |

| pRJ8239 | Apr (pNM482) hemN1′-′lacZ | This work |

| pRJ8241 | Apr Kmr (pUC18) B. japonicum hemN1::Tn5 on a 13.9-kb EcoRI fragment | This work |

| pRJ8244 | Apr Tcr (pSUP202); same insert as pRJ8241 | This work |

| pRJ8246 | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) hemN1′-′lacZ on a 9.2-kb EcoRI-StuI fragment from pRJ8239 | This work |

| pRJ8262 | Apr (pUC18) B. japonicum hemN1 on a 1.45-kb BglII fragment from pRJ8224; hemN1 in the same orientation as lacZα on pUC18 | This work |

| pRJ8267 | Apr (pUC18) B. japonicum hemN2 on a 3.2-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment | This work |

| pRJ8275 | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) 446-bp hemN2-internal SacI-SalI fragment | This work |

| pRJ8276 | Apr (pUCBM21) B. japonicum hemN2 on a 1.87-kb NsiI-EcoRI fragment; hemN2 in the same orientation as lacZα on pUCBM21 | |

| pRJ8294 | Tcr (pSUP202pol6K) 2.27-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment with PhemN2::hemN1 | This work |

| pRJ8295 | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) 1.97-kb XbaI-EcoRI fragment with PhemN1::hemN2 | This work |

| pRJ8296 | Tcr (pSUP202pol4) 2.05-kb SmaI fragment with PhemN2::hemN2 | This work |

The hemN1′-′lacZ and hemN2′-′lacZ fusions were also integrated into the chromosome of B. japonicum 9043, and the former fusion was also integrated into the chromosome of B. japonicum A9. The resulting strains were given the same numbers preceded by ′K2′ (9043 derivatives) and ′A′ (A9 derivatives); see Table 2.

Media and growth conditions.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (48) was used for growth of E. coli. For growth of serovar Typhimurium TE3006 cells, LB medium supplemented with 20 μg of hemin/ml was used. Where appropriate, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter): ampicillin, 200 (50 for serovar Typhimurium); kanamycin, 30 (10 for serovar Typhimurium); tetracycline, 10. Peptone-salts-yeast extract (PSY) medium (62) supplemented with 0.1% l-arabinose was used for routine aerobic and microaerobic cultures of B. japonicum, while yeast extract-mannitol (YEM) medium supplemented with 10 mM KNO3 (19) was used for anaerobic B. japonicum cultures. Where appropriate, 15 μg of hemin/ml and 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 80 (to prevent hemin precipitation) were added to anaerobic cultures of B. japonicum cells. Microaerobic cultures (10-ml volumes) were kept under a gas mixture consisting of 0.5% O2 and 99.5% N2 in rubber-stoppered serum bottles (volume, 500 ml), and the gas phase was periodically replaced (approximately every 12 h) by flushing the bottles with the same gas mixture. Anaerobic cultures were kept under nitrogen in serum bottles. Cells used for heme protein analysis were grown aerobically in YEM medium lacking KNO3 and anaerobically in KNO3-supplemented YEM medium. Concentrations of antibiotics for use in B. japonicum cultures were as follows (in micrograms per milliliter): spectinomycin, 100; kanamycin, 100; streptomycin, 50; tetracycline, 50 (solid media) or 25 (liquid media).

Routine DNA work and sequence analysis.

Recombinant DNA work and Southern blotting were performed according to standard protocols (64). Probes for Southern blot hybridizations were generated by PCR and labeled with digoxigenin (DIG). Single- or double-stranded plasmid DNA was cycle-sequenced by the chain termination method of Sanger et al. (65) with DNA sequencers (models 373A and 377; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). For computer-assisted analyses of DNA and protein sequences, we used the software package (version 10.0) of the Genetics Computer Group of the University of Wisconsin (UWGCG) (Madison, Wis.). Homology searches were performed by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information's BLAST network server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Cloning of two B. japonicum hemN genes.

The hemN1 gene was identified previously and cloned on an 8.1-kb EcoRI fragment in plasmid pRJ8224 (Fig. 1A) (53). A hemN1-specific DIG-labeled probe (1.11 kb) was generated by PCR with the following hemN1-internal primers: hemN2, 5′-A234TCCCGTGTCGCTATACATC-3′ (forward primer; 20 nucleotides [nt]), and hemN3, 5′-C1343CTCTTCAATGTCCACTATCCC-3′ (reverse primer; 22 nt) (numbering refers to the hemN1 sequence deposited in GenBank). A partial B. japonicum genomic plasmid library was then hybridized with this probe under low-stringency conditions (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 58°C). A strongly hybridizing clone was found to contain a 3.2-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment present in plasmid pRJ8267 and shown by sequence analysis to comprise a second hemN-like gene (Fig. 1B).

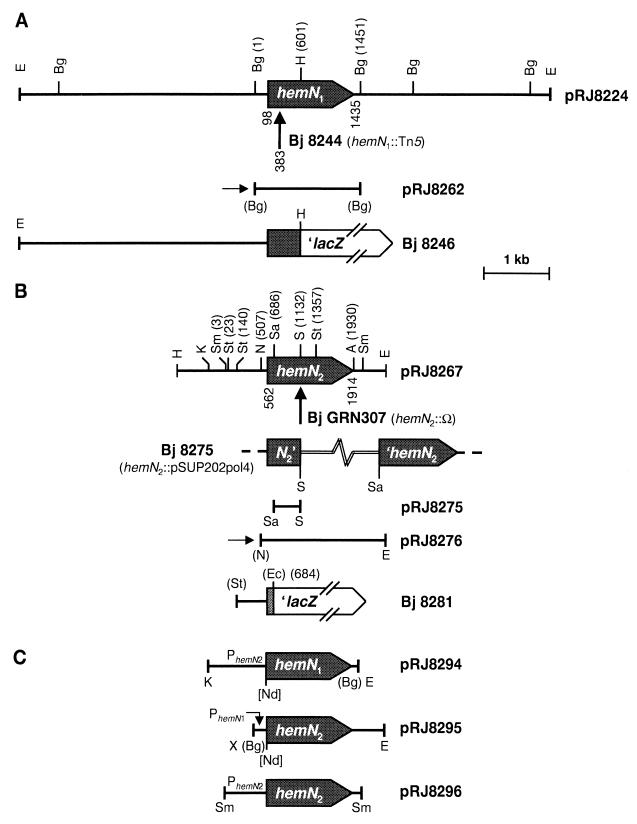

FIG. 1.

Physical maps of the B. japonicum (Bj) hemN1 (A) and hemN2 (B) regions and plasmids used for complementation experiments with B. japonicum GRN307 (C). Shown are the inserts of relevant plasmids, which are specified by their designations on the right. Vertical arrows mark the location of Tn5 in the hemN1 mutant 8244 and of the Ω cassette in the hemN2 mutant GRN307. The genetic structure of mutant 8275 is depicted in panel B, with the hemN2-disrupting vector pSUP202pol4 symbolized by a double line (not drawn to scale). Horizontal arrows indicate the orientation of the lac promoter present on the vector of the corresponding plasmids. The bottom parts of panels A and B show the structures of the chromosomally inserted lacZ fusions present in strains 8246 and 8281, respectively. Panel C shows the inserts of plasmids pRJ8294 and pRJ8295, which carry transcriptional fusions between the hemN2 promoter region (PhemN2) and hemN1 and between the hemN1 promoter region (PhemN1) and hemN2, respectively. Also shown is the insert of the control plasmid pRJ8296. Positions of start and stop codons of the hemN genes, of the Tn5 insertion in strain 8244, and of restriction sites are indicated. A, AscI; Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; Ec, Ecl136II; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; N, NsiI; Nd, NdeI; S, SalI; Sa, SacI; Sm, SmaI; St, StuI. Restriction sites in parentheses were lost during cloning procedures, and NdeI sites in brackets were introduced by PCR amplification with mutagenic primers (see Materials and Methods). Position numbers refer to the hemN1 and hemN2 sequences deposited in GenBank.

Transcript analysis.

Transcripts of both hemN genes were analyzed by primer extension experiments according to previously described protocols (5, 53). Oligonucleotide hemN1 (28 nt; 5′-C135GAGCGTCGCAATACTTGTTCAGGAGAG-3′) was used as a primer for detection of hemN1 transcripts, and oligonucleotides 8267-3 (28 nt; 5′-C582ACTGCGAGATCAGCTCTCATATCTTAC-3′) and 8267-4 (23 nt; 5′-A621TAGCTCGTGTAGCGAGGCAGTC-3′) were used for hemN2 transcripts. RNA was isolated as described previously (5) from B. japonicum strains 110spc4 (wild type), A9 (nifA), and 9043 (fixK2) grown aerobically, microaerobically, or anaerobically (where applicable).

Construction of hemN mutants.

B. japonicum hemN1 mutant strain 8244 originated from a random Tn5 mutagenesis performed with pRJ8224 in E. coli cys::Tn5. The mutated EcoRI fragment containing Tn5 at nucleotide position 383 (corresponding to codon 96 of hemN1) was subcloned into vector pSUP202 and used for marker exchange mutagenesis in B. japonicum as described previously (33, 34). The hemN2 mutant GRN307 was constructed by insertion of a 2-kb SalI fragment from pHP45::Ω (Smr Spr) into the hemN2-internal SalI site at position 1132 via marker exchange mutagenesis. In mutant 8275, the hemN2 gene was disrupted by cointegration of plasmid pRJ8275 containing a 447-bp hemN2-internal SacI-SalI fragment. The hemN1 hemN2 double mutant 8275-44 was obtained by applying the same mutagenesis procedure used for construction of strain 8275 to the hemN1 mutant 8244. The correct genomic structure of all mutant strains was confirmed by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs.

Construction of chromosomally integrated hemN′-′lacZ fusions.

For construction of the hemN1′-′lacZ fusion, a 4.25-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pRJ8224 was subcloned into pNM482, resulting in a fusion of lacZ to the 149th codon of hemN1. This fusion was subcloned as a 9.2-kb EcoRI-StuI fragment into pSUP202pol4 and integrated into the B. japonicum chromosome by conjugation and homologous recombination (Tcr selection), resulting in strain 8246 (Fig. 1A). Similarly, a 545-bp StuI-Ecl136II fragment was cloned into SmaI-digested pSUP480 for construction of a hemN2′-′lacZ fusion, which was chromosomally integrated via conjugation and homologous recombination, yielding strain 8281 (Fig. 1B). Both hemN fusions were also integrated into the fixK2 mutant 9043. Furthermore, the hemN1 fusion was introduced into the nifA mutant A9.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity assays were performed as described previously (25).

Plant infection test.

The symbiotic phenotype of hemN mutants was determined in soybean plant infection tests as described elsewhere (31, 33).

Cell fractionation, protein gel electrophoresis, and heme staining.

Cells of B. japonicum grown aerobically in YEM medium (500 ml) were harvested by centrifugation (8,000 × g for 10 min), washed twice with YEM, and finally resuspended in 10 ml of the same medium. After resuspension, 5 ml of the cell suspension was recentrifuged, and the pellet was stored at −20°C until use. The remaining 5 ml of cell suspension was inoculated into YEM medium (1 liter) supplemented with 10 mM KNO3 and was incubated anaerobically at 28°C for 72 h. Aerobically and anaerobically cultured cells were washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 0.9% NaCl and then resuspended in 3 ml of the same buffer containing 1 mM 4-amidinophenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 20 μg of DNase I/ml, and 20 μg of RNase A/ml. Cells were disrupted by three passages through an ice-cold French pressure cell (SLM-Aminco) at a pressure of about 120 MPa. The cell extract was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells, and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 140,000 × g for 2 h. The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of the same buffer and centrifuged at 140,000 × g for 2 h. The final pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of loading buffer (124 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 20% glycerol, and 4.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and electrophoresed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel at 4°C. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter and stained for heme-dependent peroxidase activity by chemiluminescence as described previously (71). The protein concentration was estimated by using the Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

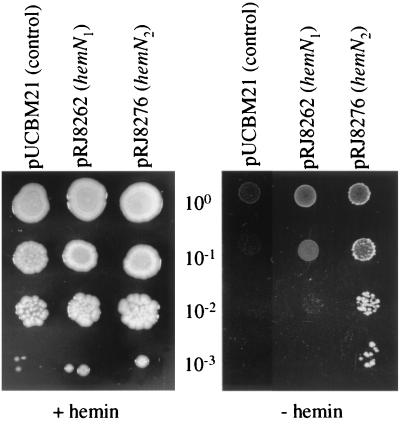

Complementation tests with Salmonella serovar Typhimurium TE3006 and B. japonicum GRN307.

Plasmids pRJ8262 and pRJ8276 (Fig. 1) carrying transcriptional fusions of the vector-borne lac promoter to hemN1 and hemN2, respectively, were used for heterologous complementation tests with the serovar Typhimurium hemN hemF mutant TE3006. They were constructed by cloning a 1.45-kb BglII fragment (hemN1) and a 1.87-kb NsiI-EcoRI fragment (hemN2) into BamHI-digested pUC18 (pRJ8262) and PstI-EcoRI-digested pUCBM21 (pRJ8276), respectively. Plasmids pRJ8262 and pRJ8276 and the control vector pUCBM21 were transformed into serovar Typhimurium TE3006. Growth of the resulting strains was tested on solid LB medium plus 0.2% glucose with (control) or without 20 μg of hemin/ml under aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

For homologous complementation experiments, plasmids pRJ8294, pRJ8295, and pRJ8296 were constructed and integrated into the chromosome of B. japonicum GRN307. Plasmids pRJ8294 and pRJ8295, respectively, contain transcriptional fusions between the promoter region of hemN2 and the hemN1 coding region, and vice versa (Fig. 1C). PCR mutagenesis with the universal M13 forward primer and the mutagenic reverse primer 8262-1 (25 nt; 5′-A107CGTCTGCATATGCTAACTTTCTCA-3′; NdeI site underlined) was used to introduce an NdeI site at the start codon of hemN1. Similarly, an NdeI site was introduced by PCR at the start codon of hemN2 using the M13 forward primer and oligonucleotide 8267-5 (34 nt; 5′-G578CGAGATCAGCTCTCATATGTTACCCATTCGTAA-3′). The hemN hybrid genes were generated by making use of the newly introduced NdeI sites, and they were cloned as a 2.27-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment into pSUP202pol6K (PhemN2::hemN1; pRJ8294) and as a 1.97-kb XbaI-EcoRI fragment into pSUP202pol4 (PhemN1::hemN2; pRJ8295), respectively. The resulting plasmids were transferred by conjugation into B. japonicum GRN307 and chromosomally integrated at the hemN2 locus by homologous recombination. For control purposes, plasmid pRJ8296, which contains a 2.05-kb SmaI fragment comprising the hemN2 gene with its own promoter region, was also integrated into the same background. The correct genomic structure of all strains was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of the B. japonicum hemN1 and hemN2 genes have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF276709 and AJ002517, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification and sequence analysis of two B. japonicum hemN genes.

The B. japonicum hemN1 gene was identified on an 8.1-kb EcoRI fragment (Fig. 1A) of cosmid 14 in the course of screening the symbiotic genome region for segments that are transcribed in a NifA-dependent manner (53). DNA sequence analysis of the hybridizing region on this EcoRI fragment, which was cloned in plasmid pRJ8224 (Fig. 1A), revealed the presence of an open reading frame (hemN1) whose predicted protein product showed significant similarity to anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenases from different bacteria (see below and Discussion). When a PCR-generated, hemN1-internal DNA fragment was used to probe Southern blots of restricted B. japonicum genomic DNA under low-stringency conditions, the observed hybridization signals suggested the presence of a second hemN-like gene (data not shown). Based on this observation, we cloned a 3,163-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment (insert of plasmid pRJ8267) whose sequence analysis eventually confirmed the presence of the presumed second hemN gene, which we named hemN2 (Fig. 1B).

The B. japonicum hemN1 (1,338 bp) and hemN2 (1,353 bp) genes specify predicted proteins of 445 and 450 amino acids with calculated molecular weights of 49,008 and 49,327, respectively. The hemN1 gene starts with a putative T98TG codon, whereas hemN2 begins with an A562TG codon. Potential ribosome binding sites (66) are present upstream of both reading frames.

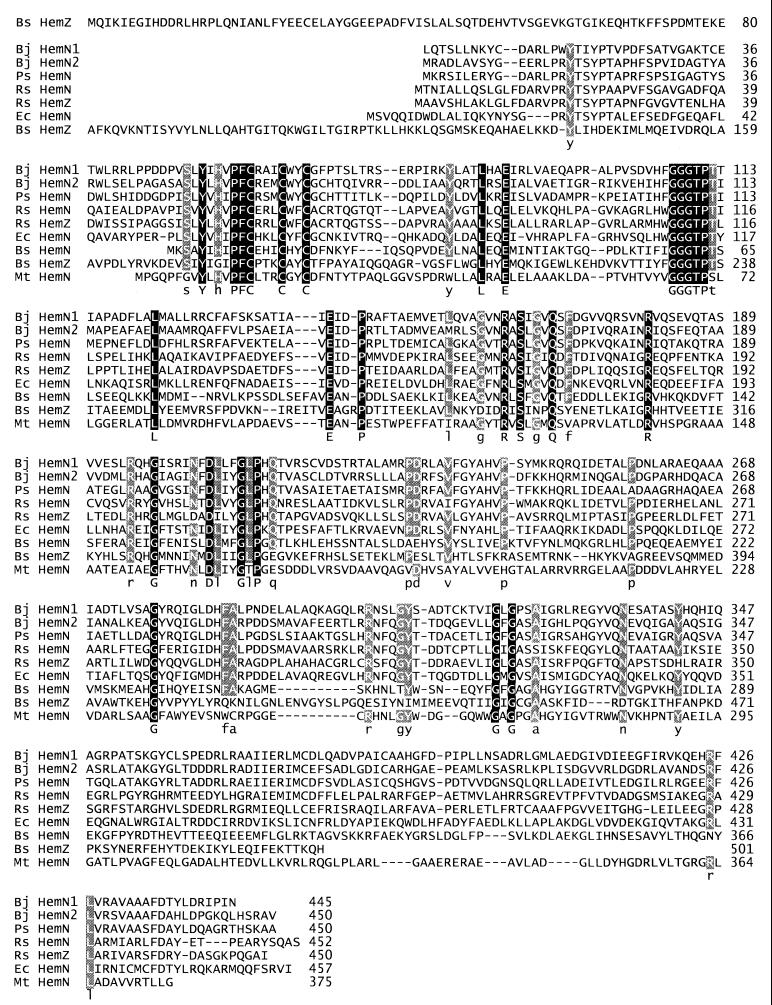

The two predicted B. japonicum HemN proteins share 53% identical (68% similar) amino acids. Interestingly, the individual HemN1 and HemN2 proteins of B. japonicum are more closely related to the HemN protein of Pseudomonas sp. strain G-179 (54 and 58% identical amino acids, respectively) (11) than to each other. In fact, Bedzyk et al. (11) suggested that this particular Pseudomonas strain is more likely a Rhizobium species on the basis of 16S rRNA analyses. The HemN and HemZ proteins of R. sphaeroides, the HemN protein of E. coli, the HemN and HemZ proteins of Bacillus subtilis, and the HemN protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are 38, 38, 36, 28, 26, and 27% identical to B. japonicum HemN1 and 41, 42, 38, 25, 22, and 28% identical to B. japonicum HemN2, respectively (see also Discussion and Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the B. japonicum (Bj) HemN proteins with HemN-like proteins of Pseudomonas sp. strain G-179 (Ps) (accession number AAC79446) (11), R. sphaeroides (Rs) (HemN accession number, P95651; HemZ accession number, P51008) (18, 74), E. coli (Ec) (P32131) (70), B. subtilis (Bs) (HemN accession number, P54304; HemZ) (38, 39), and M. tuberculosis (Mt) (P71756) (17). Residues conserved in all nine proteins are highlighted on a solid background and represented by uppercase letters in the consensus line; residues conserved in at least seven proteins are highlighted on a shaded background and represented by lowercase letters in the consensus line.

Transcript analyses of hemN1 and hemN2.

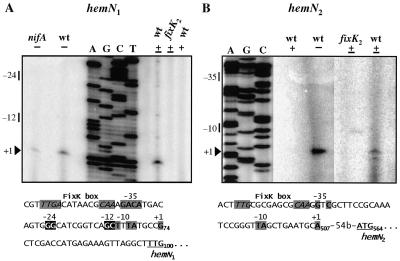

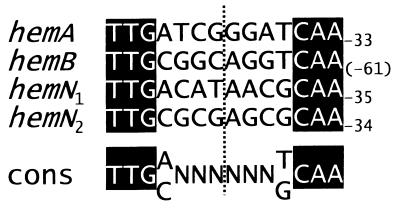

Primer extension experiments were performed to analyze hemN transcripts in cells of B. japonicum wild-type, fixK2 mutant, and nifA mutant strains grown under different conditions (Fig. 2). No transcript was detected from either hemN gene when RNA from aerobically grown cells was used. By contrast, reverse transcription with RNA isolated from microaerobically or anaerobically grown cells revealed hemN1- and hemN2-specific transcripts starting at G74 and A507, respectively, 23 and 54 nt upstream of the respective translational start codons. The synthesis of both hemN transcripts was dependent on the FixK2 activator protein, as deduced from their absence in fixK2 mutant cells. In line with this finding, potential FixK boxes (22) are located around positions −41.5 (hemN1; T26TGN7CAA) and −40.5 bp (hemN2; T460TGN8CAA) upstream of the respective transcription start sites (see also Discussion). The putative −35 and −10 regions associated with both hemN genes exhibited only limited similarity with the consensus sequence defined for B. japonicum housekeeping promoters (10). Because our previous competitive DNA-RNA hybridization studies suggested that hemN1 is under the control of NifA (53), we extended the hemN1 transcript analysis to anaerobically grown nifA mutant cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, the hemN1 transcript was present but less abundant in the nifA mutant than in the wild type. Moreover, a potential −24/−12-type promoter was found upstream of the hemN1 transcriptional start site (G53GCAN7GCT; the most invariant nucleotides at positions −24 and −12 are underlined); this promoter, in concert with RNA polymerase containing ς54, may direct NifA-dependent hemN1 transcription.

FIG. 2.

Mapping of the transcription start sites of B. japonicum hemN1 (A) and hemN2 (B) by primer extension. Total RNA was isolated from aerobically (+), microaerobically (±), or anaerobically (−) grown cells of wild-type (wt) B. japonicum or mutant strain A9 (nifA) or 9043 (fixK2) and was used for primer extension experiments with the hemN1-specific primer hemN1 (A) and the hemN2-specific primer 8267-4 (B). The sequence ladders shown were generated with pRJ8262 (A) and pRJ8267 (B) DNAs and the same primers which were used for the respective transcript mapping. Note that panel B is a composite of relevant lanes of a single gel and that the “T” lane is missing in the sequence ladder. The dominant transcription start sites are marked by “+1” and solid arrowheads. The relevant nucleotide sequences of the hemN1 and hemN2 promoter regions are shown at the bottoms of panels A and B, respectively. Elements of putative −35/−10- and −24/−12-type promoters are shaded and highlighted on a solid background, respectively. Conserved nucleotides of presumptive FixK boxes (5′-TTGATN4ATCAA-3′) (22) are italicized and shaded. The transcription start site is indicated by “+1,” and the start codon of each hemN gene is underlined. The numbering of nucleotide positions refers to that given in Fig. 1 and in the sequences deposited in GenBank.

Analysis of hemN1 and hemN2 expression with lacZ fusions.

To quantify hemN expression, translational lacZ fusions to both genes were constructed as described in Materials and Methods and integrated into the chromosome of wild-type B. japonicum. The same fusions were also integrated into the chromosomes of suitable regulatory mutants in order to confirm the results of the transcript studies, which suggested a dependence of both hemN genes on FixK2 and, in addition, a dependence of hemN1 on NifA. The resulting strains were cultivated under aerobic, microaerobic, and, where applicable, anaerobic conditions, and hemN expression was monitored by assaying β-galactosidase activity (Table 2). None of the hemN genes was significantly expressed in aerobically grown cells, but expression of both genes was strongly induced (≥20-fold) under reduced oxygen conditions. Microaerobic induction of both hemN genes was strictly dependent on FixK2. Furthermore, it appeared as if the postulated −24/−12-type promoter indeed contributed to hemN1 expression under anaerobic conditions, as inferred from the reduced hemN1 expression in the nifA mutant background. Since fixK2 mutants do not grow anaerobically with nitrate (52), it was not possible to directly assess the likely function of FixK2 in anaerobic hemN expression.

TABLE 2.

Aerobic, microaerobic, and anaerobic expression of a hemN1′-′lacZ and a hemN2′-′lacZ fusion chromosomally integrated into different B. japonicum strains

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase

activity (Miller units)a under the indicated

growth conditionb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Microaerobic | Anaerobicc | ||

| 8246 | hemN1′-′lacZ | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 11.1 ± 1.8 | 46.8 ± 5.1 |

| K28246 | hemN1′-′lacZ fixK2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | NA |

| A8246 | hemN1′-′lacZ nifA | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 24.8 ± 3.8 |

| 8281 | hemN2′-′lacZ | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 57.4 ± 7.5 | ND |

| K28281 | hemN2′-′lacZ fixK2 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.3 | NA |

Values are means ± standard errors for three (aerobic) or at least four (microaerobic, anaerobic) cultures which were assayed in duplicate.

Aerobic and microaerobic (0.5% O2, 99.5% N2) cultures were grown in PSY medium containing spectinomycin (100 μg/ml) and 0.1% l-arabinose for 2 to 3 days. Anaerobic cultures were grown for 5 days in YEM medium supplemented with 10 mM KNO3.

NA, not applicable; ND, not done.

Characterization of hemN mutants.

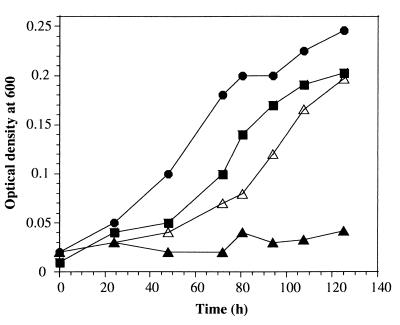

The physiological importance of the B. japonicum hemN genes was studied by phenotypic analysis of suitable hemN mutant strains. First, we tested growth of the mutant strains under different oxygen conditions. None of the mutants differed from the wild type with regard to aerobic and microaerobic (0.5% O2) growth (data not shown). By contrast, the hemN2 mutant strain 8275 was unable to grow under anaerobic conditions with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor whereas growth of the hemN1 mutant 8244 under these conditions was comparable to that of the wild type (Fig. 3). Anaerobic growth of the hemN2 mutant was largely restored when the medium was supplemented with 15 μg of hemin per ml. Thus, an intact hemN2 gene is essential for anaerobic growth, and its function cannot be replaced by the other hemN homolog, hemN1.

FIG. 3.

Anaerobic growth of wild-type B. japonicum (solid circles) and hemN mutant strains 8244 (hemN1 mutant) (solid squares) and 8275 (hemN2 mutant) (triangles). Washed cells were inoculated into YEM medium plus 10 mM KNO3 lacking (solid symbols) or containing (open triangles) 15 μg of hemin/ml, and growth of the cells under anaerobic conditions was measured by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm.

Next, the symbiotic properties of the hemN mutants were determined in a soybean plant infection test (Table 3). The hemN1 mutant 8244 showed a wild-type phenotype with regard to the number, size, morphology, and acetylene reduction activity of the root nodules. By contrast, mutants 8275 (hemN2) and 8275-44 (hemN1 hemN2) elicited smaller nodules with a residual fixation activity of only 5% relative to that of the wild type. Moreover, the interior color of these nodules was pale pink to white, indicating strongly diminished levels of leghemoglobin. This result showed that hemN2, but not hemN1, is required for a fully effective symbiosis.

TABLE 3.

Symbiotic properties of B. japonicum hemN mutants

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Characteristics (mean ±

SE)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of nodules | Dry wt/nodule (mg) | Fix activity (% of wild type) | ||

| 110spc4 | Wild type | 19 ± 6 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 100 ± 8 |

| 8244 | hemN1 | 15 ± 2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 87 ± 22 |

| 8275 | hemN2 | 20 ± 7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 1.7 |

| 8275-44 | hemN1hemN2 | 22 ± 4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 1.4 |

For at least six individual plants. Fixation (Fix) activity was measured as the amount of C2H2 reduced per minute per gram (dry weight) of nodule.

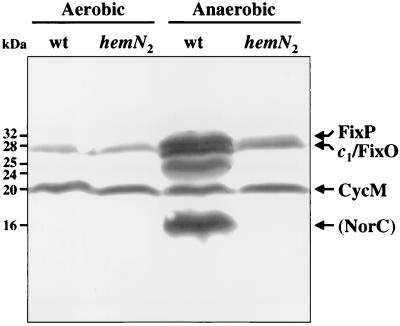

Analysis of heme proteins.

Membrane protein fractions from wild-type 110spc4 and mutant GRN307 cells were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained for covalently bound heme proteins. In the membrane fraction from aerobically grown cells, two stained bands with Mrs of 28,000 and 20,000 were detected (Fig. 4, left two lanes). These two proteins have been identified previously as the membrane-bound c-type cytochromes c1 (Mr, 28,000) and CycM (Mr, 20,000) (12, 68). After incubation of the cells under anaerobic conditions with nitrate, the membrane fraction from wild-type cells showed, in addition to cytochrome c1 and CycM, at least four c-type cytochromes with Mrs of 32,000, 25,000, 24,000, and 16,000 (Fig. 4, second lane from the right). As described by Preisig and coworkers (58), there is even a fifth protein with an Mr of 28,000 comigrating with cytochrome c1. The induced proteins with Mrs of 32,000 and 28,000 detected in anaerobic cultures of wild-type cells have been identified previously as the B. japonicum FixP and FixO proteins, respectively, of the cbb3-type, high-affinity cytochrome oxidase encoded by the fixNOQP operon (58, 60). Similarly, previous N-terminal amino acid sequencing of the 16-kDa protein identified this protein as a nitric oxide reductase homolog (NorC; R. Zufferey, unpublished data). The identities of the 24- and 25-kDa proteins are not known. In contrast to the membrane fraction from anaerobic cultures of the wild type, that of mutant strain GRN307 contained only two major c-type cytochromes, the 28-kDa cytochrome c1 and the 20-kDa CycM protein (Fig. 4, rightmost lane), which were also present in aerobically grown cells. Occasionally, trace amounts of the 32-kDa FixP protein were also detected in the mutant membranes. Similar results were obtained with the hemN2 mutant 8275, whereas the hemN1 mutant 8244 showed the same pattern of heme-stained proteins as the wild type (data not shown). Taken together, it is evident that synthesis of anaerobically inducible c-type cytochromes is severely impaired in the hemN2 mutants (see also Discussion).

FIG. 4.

Heme-stained proteins in membrane fractions prepared from cells of B. japonicum strains 110spc4 (wt) and GRN307 (hemN2) grown aerobically in YEM medium or anaerobically in YEM medium supplemented with 10 mM KNO3. Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and stained for covalently bound heme proteins. Each lane contains about 25 μg of membrane proteins. Heme-stained c-type cytochromes identified previously (58) are specified at the right margin. The 16-kDa protein was identified as a NorC homolog (nitric oxide reductase) by N-terminal sequencing of the protein (R. Zufferey, unpublished data). The identities of unmarked bands are not known. Apparent molecular masses of the proteins are shown at the left margin.

Complementation of hemN mutants.

The phenotypic analysis of the hemN mutants suggested that hemN1 does not functionally compensate for a missing hemN2 gene. We were interested in verifying this by complementation tests. When plasmids pRJ8262 and pRJ8276 (Fig. 1) were used to complement the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium hemF hemN double mutant TE3006, functional complementation for growth on heme-deficient medium was observed only with the hemN2 plasmid pRJ8276, not with the hemN1 plasmid pRJ8262 (Fig. 5). For complementation experiments in the homologous B. japonicum background, plasmids pRJ8294, pRJ8295, and pRJ8296 (Fig. 1C) (see Materials and Methods for detailed descriptions of these plasmids) were integrated into the chromosome of the hemN2 mutant GRN307, and the resulting strains were tested for the ability to grow anaerobically in YEM medium with nitrate. B. japonicum strain 8294-1, which contains the transcriptional PhemN2::hemN1 fusion, was unable to grow under these conditions, indicating that hemN1 could not substitute for hemN2 even when it was transcribed from the hemN2 promoter (data not shown). By contrast, strain 8295-4, harboring the PhemN1::hemN2 fusion, grew as well as the control strain 8296 (hemN2 with its own promoter), thus demonstrating that hemN1 promoter activity is not limiting in this test. Taken together, the complementation results strongly support the notion that the product of hemN1 is not a functional substitute for the HemN2 protein.

FIG. 5.

Complementation of the heme auxotrophic mutant Salmonella serovar Typhimurium TE3006 (hemF hemN). The TE3006 derivatives harboring either pUCBM21 (vector control), pRJ8262 (B. japonicum hemN1), or pRJ8276 (hemN2) were grown overnight in liquid LB medium containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and hemin (20 μg/ml) at 30°C. After washing and adjustment to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8, 1-μl volumes of the suspensions and serial dilutions thereof (indicated between the panels) were spotted onto LB agar plates containing ampicillin, glucose (0.2% [wt/vol]), and either 20 μg of hemin/ml (left panel) or 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (right panel). After incubation of the plates at 30°C for 40 h, the plates were photographed. Note that comparable background growth was observed on hemin-free medium with TE3006 harboring pUCBM21 or pRJ8262.

DISCUSSION

Starting out from a competitive DNA-RNA hybridization approach to identify NifA-dependent genes in the symbiotic gene region, we have identified two distinct hemN genes in B. japonicum. Unexpectedly, expression of hemN1 was only partially dependent on NifA but predominantly dependent on FixK2, which is also the mediator of microaerobic induction of hemN2. Thus, the subtractive hybridization method which initially led to the discovery of hemN1 (53) is apparently sensitive enough to detect genes whose expression varies only by a factor of 2. Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine the contribution of FixK2-dependent hemN1 expression under anaerobic conditions due to the inability of fixK2 mutants to grow under these conditions. The seemingly absent hemN1 expression under microaerobic conditions in the fixK2 mutant strain K28246 can be explained by the impaired activity of the oxygen-sensitive NifA protein under these conditions (26). Moreover, NifA-mediated activation of the hemN1 promoter is probably weak because of the absence of a consensus NifA binding site (TGTN10ACA) (13). The core elements of the promoters directing NifA- and FixK2-dependent transcription of hemN1 seem to overlap, as indicated by the comparable lengths of the primer extension products detected in the wild-type, fixK2 mutant, and nifA mutant strains. This situation is reminiscent of the B. japonicum fixR-nifA operon, which is also preceded by two overlapping promoters that are recognized by distinct RNA polymerase holoenzymes (6, 7). Obviously, the complex transcriptional organization of hemN1 would require further analysis of the proposed promoters. However, in the absence of any functional evidence for HemN1, such studies are of little significance; hence, they were not performed.

FixK2-dependent, microaerobic induction of both hemN genes is in line with the presence of putative FixK boxes (TTGN7CAA; TTGN8CAA) (Fig. 6) 41.5 and 40.5 bp upstream of the transcriptional start of hemN1 and hemN2, respectively. Not surprisingly, the associated promoter regions are only poorly conserved, as is the case in numerous other FixK2-dependent genes and operons, such as fixNOQP (52, 57) and fixGHIS (59), and also in many Fnr-activated promoters (32). In agreement with our findings with the B. japonicum hemN genes, induction of hemN-like genes under low-oxygen conditions has been reported for E. coli (70), R. eutropha (46), and B. subtilis (39), but detailed information about the regulatory mechanism is available only for P. aeruginosa (63). In this organism, anaerobic induction of hemN expression is dependent on the dual action of two Fnr-like redox response regulators, Anr and Dnr, and an Anr box centered around position −41.5 upstream of the hemN transcriptional start site. Unlike the B. japonicum hemN genes, hemN of P. aeruginosa is also expressed under aerobic conditions, and Anr (but not Dnr) is required for this type of control.

FIG. 6.

FixK boxes associated with B. japonicum heme biosynthetic genes which are subject to oxygen control. A deduced consensus sequence (cons) is given at the bottom of the figure. The vertical dotted line marks a dyad symmetry axis with respect to the most conserved nucleotides, indicated by white letters on a solid background. Numbers refer to the distance of the marked nucleotide from the transcription start site, except in the case of hemB, where the distance relative to the translation start site is indicated because the hemB transcription start site is not known (14). The function of the FixK box of hemA has been substantiated by deletion analysis (56).

With the newly identified hemN genes, a total of four different heme biosynthesis genes are now known in B. japonicum. The three previously characterized genes include hemA (encoding ALA synthase [47]), hemB (encoding aminolevulinic acid dehydratase [14]), and hemH (encoding ferrochelatase [29]). While the hemH gene appears not to be regulated, expression of hemA and hemB is under dual control by the cellular oxygen and iron conditions (15, 16, 55, 56). Microaerobic induction of both hemA and hemB was shown to require fixJ. It is very likely that this type of control is mediated via the subordinate fixK2 gene, because both genes are preceded by a well-conserved FixK box as in the case of the two hemN genes (Fig. 6) (see reference 52). By contrast, iron control involves two different regulatory proteins, namely fur for hemA and irr for hemB (35). Whether the hemN genes of B. japonicum are subject to iron control is not presently known, but results of similar studies in E. coli suggest that iron may indeed affect heme biosynthesis at the level of hemN expression (70).

The B. japonicum hemN genes were functionally characterized by mutation and complementation experiments with a heme-auxotrophic Salmonella serovar Typhimurium hemF hemN double mutant. Both sets of experiments clearly indicated that under the conditions tested only HemN2 is functional and that it is required for anaerobic growth and efficient symbiotic nitrogen fixation but not for aerobic or microaerobic growth. Hence, it is likely that the “coproporphyrinogenase” activity measured in extracts of anaerobically grown B. japonicum cells by Keithly and Nadler (43) originated from hemN2 expression. Hemin supplementation restored anaerobic growth of the hemN2 mutant, indicating that heme is taken up by the cells and plays an essential role under these conditions.

Evidence for two genes specifying (putative) oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenases was reported previously for other bacteria such as R. sphaeroides (HemF and HemZ) (18, 74), Helicobacter pylori (69), Synechocystis sp. strain PC6803 (42) (accession numbers BAA18218 and BAA17272), and B. subtilis (HemN and HemZ) (37, 39). The existence of a second hemN gene (hemZ) was also predicted in P. aeruginosa, but the corresponding gene has not yet been identified (63). In B. subtilis, both proteins were shown to be functional by complementation of the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium hemF hemN double mutant. Moreover, the presence of a third anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenase in this species was postulated because a hemN hemZ double mutant showed a wild-type phenotype (39).

Heme biosynthesis in B. japonicum is particularly crucial during free-living, microaerobic growth and in symbiosis when the specialized respiratory chain comprising the FixNOQP oxidase is synthesized to support microaerobic respiration (3, 4; for a recent review, see reference 36). We showed that the c-type cytochromes FixO and FixP, whose synthesis is induced under low-oxygen conditions, are missing in membranes from anaerobically incubated mutant strains lacking a functional hemN2 gene. In addition, a heme-stainable band of approximately 16 kDa, which is very prominent in anaerobic wild-type membranes, is also absent in the hemN2 mutant. Somewhat unexpectedly, cytochromes c1 and CycM were still detectable in the mutant membranes. These proteins, however, are synthesized under aerobic conditions also, and thus, they possibly persisted in the cells after the shift to anaerobiosis. Thus, the lack of a functional coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenase is manifested only at the level of proteins synthesized de novo under anaerobic conditions. Nitrogen fixation activity was not completely abolished in hemN2 mutants. It is unlikely that the mutant bacteroids were supplemented with heme by the soybean host plant, because a B. japonicum hemB mutant, which is blocked at the second step in heme biosynthesis, could not be rescued by the plant (14). Thus, small amounts of heme may be synthesized in the hemN2 mutant bacteroids, possibly due to residual activity of the (yet unidentified) aerobic coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, which may be partially functional even at the low-oxygen conditions in nodules. The observation that hemN2 mutants grew normally under microaerobic conditions (0.5% oxygen) provides further support for this hypothesis.

Amino acid sequence comparison of different HemN proteins cannot provide a clear clue as to the basis of the likely nonfunctionality of HemN1 (Fig. 7). The characteristic glycine-rich H(F/W)GGGTPT112 motif (numbers in italics refer to B. japonicum HemN1 and HemN2) is perfectly conserved in both B. japonicum proteins. The distal cysteine of the H53XPFCX3CX2CXC motif, which is characteristic for anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenases (74), is replaced by a phenylalanine in HemN1. However, the same exchange is also observed in other HemN-like proteins, e.g., those of B. subtilis (HemN and HemZ) (37, 39), M. tuberculosis (17), and Haemophilus influenzae (28). Similarly, F and Q of the LXRNFQGY309 motif, which is conserved in the C-terminal portion of HemN proteins from gram-negative bacteria, are replaced by S306 and L307 in HemN1, but HemN proteins from gram-positive organisms also deviate from the consensus sequence at these positions.

In conclusion, one is left with the question of the role of the seemingly nonfunctional (but expressed) hemN1 gene in B. japonicum. It appears unlikely that hemN1 becomes functional under conditions which were not tested in this study. A hypothetical role of HemN1 under aerobic conditions as proposed for HemN of P. aeruginosa (63) can be excluded because the hemN1 gene was not expressed in B. japonicum under these conditions. After all, families of homologous genes (paralogs) are not uncommon in B. japonicum, as documented by two rpoN genes (44), three rpoH genes (50, 51), two fixK genes (2, 52), and five groESL operons (25, 27). However, unlike the newly identified hemN genes, individual members of the previously characterized B. japonicum gene families were shown to be at least partially functional.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Franziska Biellmann, Astrid Chanfon, Roger Frei, and Bruno Mancosu for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research and by grant PB97-1216 from Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior e Investigación Científica.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexeyev M F. Three kanamycin resistance gene cassettes with different polylinkers. BioTechniques. 1995;18:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthamatten D, Scherb B, Hennecke H. Characterization of a fixLJ-regulated Bradyrhizobium japonicum gene sharing similarity with the Escherichia coli fnr and Rhizobium meliloti fixKgenes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2111–2120. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2111-2120.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleby C A. Electron transport systems of Rhizobium japonicum. I. Haemoprotein P-450, other co-reactive pigments, cytochromes and oxidases in bacteroids from N2-fixing root nodules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;172:71–87. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(69)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avissar Y J, Nadler K D. Stimulation of tetrapyrrole formation in Rhizobium japonicumby restricted aeration. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:782–789. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.3.782-789.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babst M, Hennecke H, Fischer H M. Two different mechanisms are involved in the heat shock regulation of chaperonin gene expression in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:827–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.438968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrios H, Fischer H M, Hennecke H, Morett E. Overlapping promoters for two different RNA polymerase holoenzymes control Bradyrhizobium japonicum nifAexpression. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1760–1765. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1760-1765.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrios H, Grande R, Olvera L, Morett E. In vivo genomic footprinting analysis reveals that the complex Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixRnifApromoter region is differently occupied by two distinct RNA polymerase holoenzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1014–1019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer E, Kaspar T, Fischer H M, Hennecke H. Expression of the fixR-nifA operon in Bradyrhizobium japonicumdepends on a new response regulator, RegR. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3853–3863. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3853-3863.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beale S I. Biosynthesis of hemes. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck C, Marty R, Kläusli S, Hennecke H, Göttfert M. Dissection of the transcription machinery for housekeeping genes of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:364–369. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.364-369.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedzyk L, Wang T, Ye R W. The periplasmic nitrate reductase in Pseudomonassp. strain G-179 catalyzes the first step of denitrification. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2802–2806. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2802-2806.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bott M, Ritz D, Hennecke H. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum cycM gene encodes a membrane-anchored homolog of mitochondrial cytochrome c. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6766–6772. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6766-6772.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buck M, Miller S, Drummond M, Dixon R. Upstream activator sequences are present in the promoters of nitrogen fixation genes. Nature. 1986;320:374–378. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan S, O'Brian M R. Bradyrhizobium japonicumδ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase is essential for symbiosis with soybean and contains a novel metal-binding domain. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7222–7227. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7222-7227.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan S, O'Brian M R. Transcriptional regulation of δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase synthesis by oxygen in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and evidence for developmental control of the hemBgene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3706–3710. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3706-3710.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan S, Titus D E, O'Brian M R. Metals control activity and expression of the heme biosynthesis enzyme δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5516–5520. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5516-5520.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosisfrom the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coomber S A, Jones R M, Jordan P M, Hunter C N. A putative anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III oxidase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. I. Molecular cloning, transposon mutagenesis and sequence analysis of the gene. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3159–3169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel R M, Appleby C A. Anaerobic-nitrate, symbiotic and aerobic growth of Rhizobium japonicum: effects on cytochrome P450, other haemoproteins, nitrate and nitrite reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;275:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darie S, Gunsalus R P. Effect of heme and oxygen availability on hemA gene expression in Escherichia coli: role of the fnr, arcA, and himAgene products. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5270–5276. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5270-5276.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive Nifl-Nifa complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in γ-Proteobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer H M. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:352–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer H M. Environmental regulation of rhizobial symbiotic nitrogen fixation genes. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer H M, Alvarez-Morales A, Hennecke H. The pleiotropic nature of symbiotic regulatory mutants: Bradyrhizobium japonicum nifA gene is involved in control of nifgene expression and formation of determinate symbiosis. EMBO J. 1986;5:1165–1173. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer H M, Babst M, Kaspar T, Acuña G, Arigoni F, Hennecke H. One member of a groESL-like chaperonin multigene family in Bradyrhizobium japonicumis co-regulated with symbiotic nitrogen fixation genes. EMBO J. 1993;12:2901–2912. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer H M, Hennecke H. Direct response of Bradyrhizobium japonicum nifA-mediated nifgene regulation to cellular oxygen status. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;209:621–626. doi: 10.1007/BF00331174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer H M, Schneider K, Babst M, Hennecke H. GroEL chaperonins are required for the formation of a functional nitrogenase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Arch Microbiol. 1999;171:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzaeRd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frustaci J M, O'Brian M R. Characterization of a Bradyrhizobium japonicum ferrochelatase mutant and isolation of the hemHgene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4223–4229. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4223-4229.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuhrmann M, Hennecke H. Coding properties of cloned nitrogenase structural genes from Rhizobium japonicum. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;187:419–425. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Göttfert M, Hitz S, Hennecke H. Identification of nodS and nodU, two inducible genes inserted between the Bradyrhizobium japonicum nodYABC and nodIJgenes. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1990;3:308–316. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-3-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guest J R, Green J, Irvine A S, Spiro S. The FNR modulon and FNR-regulated gene expression. In: Lin E C C, Lynch A S, editors. Regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1996. pp. 317–342. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hahn M, Hennecke H. Localized mutagenesis in Rhizobium japonicum. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;193:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hahn M, Meyer L, Studer D, Regensburger B, Hennecke H. Insertion and deletion mutations within the nif region of Rhizobium japonicum. Plant Mol Biol. 1984;3:159–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00016063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamza I, Qi Z, King N D, O'Brian M R. Fur-independent regulation of iron metabolism by Irr in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Microbiology. 2000;146:669–676. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-3-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennecke H. Rhizobial respiration to support symbiotic nitrogen fixation. In: Elmerich C, Kondorosi A, Newton W E, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation for the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hippler B, Homuth G, Hoffmann T, Hungerer C, Schumann W, Jahn D. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis hemN. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7181–7185. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7181-7185.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homuth G, Heinemann M, Zuber U, Schumann W. The genes lepA and hemN form a bicistronic operon in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1996;142:1641–1649. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homuth G, Rompf A, Schumann W, Jahn D. Transcriptional control of Bacillus subtilis hemN and hemZ. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5922–5929. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5922-5929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hungerer C, Troup B, Römling U, Jahn D. Regulation of the hemA gene during δ-aminolevulinic acid formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1435–1443. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1435-1443.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan P M. Highlights in haem biosynthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:902–911. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(94)90273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystissp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keithly J H, Nadler K D. Protoporphyrin formation in Rhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:838–845. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.838-845.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kullik I, Fritsche S, Knobel H, Sanjuan J, Hennecke H, Fischer H M. Bradyrhizobium japonicum has two differentially regulated, functional homologs of the ς54 gene (rpoN) J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1125–1138. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1125-1138.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kündig C, Hennecke H, Göttfert M. Correlated physical and genetic map of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum110 genome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:613–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.613-622.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lieb C, Siddiqui R A, Hippler B, Jahn D, Friedrich B. The Alcaligenes eutrophus hemNgene, encoding the oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, is required for heme biosynthesis during anaerobic growth. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:52–60. doi: 10.1007/s002030050540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClung C R, Somerville J E, Guerinot M L, Chelm B K. Structure of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum gene hemAencoding 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase. Gene. 1987;54:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minton N P. Improved plasmid vectors for the isolation of translational lacgene fusions. Gene. 1984;31:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narberhaus F, Krummenacher P, Fischer H-M, Hennecke H. Three disparately regulated genes for ς32-like transcription factors in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:93–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3141685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narberhaus F, Weiglhofer W, Fischer H M, Hennecke H. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum rpoH1 gene encoding a ς32-like protein is part of a unique heat shock gene cluster together with groESL1and three small heat shock genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5337–5346. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5337-5346.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nellen-Anthamatten D, Rossi P, Preisig O, Kullik I, Babst M, Fischer H M, Hennecke H. Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixK2, a crucial distributor in the FixLJ-dependent regulatory cascade for control of genes inducible by low oxygen levels. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5251–5255. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5251-5255.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nienaber A, Huber A, Göttfert M, Hennecke H, Fischer H M. Three new NifA-regulated genes in the Bradyrhizobium japonicumsymbiotic gene region discovered by competitive DNA-RNA hybridization. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1472–1480. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1472-1480.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Page K M, Connolly E L, Guerinot M L. Effect of iron availability on expression of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum hemAgene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1535–1538. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.5.1535-1538.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Page K M, Guerinot M L. Oxygen control of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum hemAgene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3979–3984. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3979-3984.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Preisig O. Genetische und biochemische Charakterisierung der für die Bakteroidrespiration essentiellen Häm-Kupfer-Oxidase (cbb3-Typ) von Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Ph.D. thesis. Zürich, Switzerland: Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Preisig O, Anthamatten D, Hennecke H. Genes for a microaerobically induced oxidase complex in Bradyrhizobium japonicumare essential for a nitrogen-fixing endosymbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3309–3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Hennecke H. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:297–305. doi: 10.1007/s002030050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby C A, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1532–1538. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitroinsertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Regensburger B, Hennecke H. RNA polymerase from Rhizobium japonicum. Arch Microbiol. 1983;135:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00408017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rompf A, Hungerer C, Hoffmann T, Lindenmeyer M, Römling U, Gross U, Doss M O, Arai H, Igarashi Y, Jahn D. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemNby the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:985–997. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli16S ribosomal RNA: complementary to nonsense triplets and ribosome-binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. Vector plasmids for in vivo and in vitro manipulation of Gram-negative bacteria. In: Pühler A, editor. Molecular genetics of the bacteria-plant interaction. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1983. pp. 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thöny-Meyer L, Stax D, Hennecke H. An unusual gene cluster for the cytochrome bc1 complex in Bradyrhizobium japonicumand its requirement for effective root nodule symbiosis. Cell. 1989;57:683–697. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzgerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Troup B, Hungerer C, Jahn D. Cloning and characterization of the Escherichia coli hemNgene encoding the oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3326–3331. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3326-3331.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vargas C, McEwan A G, Downie J A. Detection of c-type cytochromes using enhanced chemiluminescence. Anal Biochem. 1993;209:323–326. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu K, Delling J, Elliot T. The genes required for heme synthesis in Salmonella typhimuriuminclude those encoding alternative functions for aerobic and anaerobic coproporphyrinogen oxidation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3953–3963. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3953-3963.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu K, Elliott T. Cloning, DNA sequence, and complementation analysis of the Salmonella typhimurium hemNgene encoding a putative oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3196–3203. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3196-3203.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeilstra-Ryalls J H, Kaplan S. Aerobic and anaerobic regulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: the role of the fnrLgene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6422–6431. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6422-6431.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zufferey R, Preisig O, Hennecke H, Thöny-Meyer L. Assembly and function of the cytochrome cbb3 oxidase subunits in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9114–9119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.9114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]