Abstract

The enhancer binding protein NIFA and the sensor protein NIFL from Azotobacter vinelandii comprise an atypical two-component regulatory system in which signal transduction occurs via complex formation between the two proteins rather than by the phosphotransfer mechanism, which is characteristic of orthodox systems. The inhibitory activity of NIFL towards NIFA is stimulated by ADP binding to the C-terminal domain of NIFL, which bears significant homology to the histidine protein kinase transmitter domains. Adenosine nucleotides, particularly MgADP, also stimulate complex formation between NIFL and NIFA in vitro, allowing isolation of the complex by cochromatography. Using limited proteolysis of the purified proteins, we show here that changes in protease sensitivity of the Q linker regions of both NIFA and NIFL occurred when the complex was formed in the presence of MgADP. The N-terminal domain of NIFA adjacent to the Q linker was also protected by NIFL. Experiments with truncated versions of NIFA demonstrate that the central domain of NIFA is sufficient to cause protection of the Q linker of NIFL, although in this case, stable protein complexes are not detectable by cochromatography.

In the free-living diazotrophs Klebsiella pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii, activation of expression of genes involved in nitrogen fixation by the enhancer binding protein NIFA is controlled by the sensor protein NIFL in response to changes in levels of oxygen and fixed nitrogen in vivo. The NIFA protein activates transcription at the ςN-dependent promoters for nitrogen fixation (nif) genes, in combination with ςN-RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Transcriptional activation by NIFA is repressed by NIFL in response to increases in levels of fixed nitrogen and extracellular oxygen (reviewed in reference 5). The NIFL proteins from both A. vinelandii and K. pneumoniae have been shown to contain flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as the prosthetic group (14, 20). For A. vinelandii NIFL, we have shown that the oxidized form of the protein inhibits NIFA activity, but when the flavin moiety is reduced, NIFA activity is unaffected (14). In addition to its ability to act as a redox sensor, NIFL is also responsive to adenosine nucleotides in vitro, the inhibitory activity of the protein being stimulated by the presence of ADP (8). The NIFL protein is comprised of two domains tethered by a Q linker (4, 6,7). Q linkers are short (20 to 30 residues), hydrophilic sequences rich in Gln, Glu, Pro, Arg, and Ser, which serve to tether independently folding domains of some regulatory proteins (24). The N-terminal domain contains the flavin binding site and shows some homology to other oxygen- and redox-sensing proteins (4). The C-terminal domain of A. vinelandii NIFL shows significant homology to the histidine protein kinase transmitter domains, including the conserved histidine residue (4). We have shown previously that this domain binds nucleotides, particularly ADP (22). However, phosphotransfer between NIFL and NIFA has never been demonstrated (2, 15, 21), and signal transduction is now known to occur via complex formation between the two proteins. Previous experiments with cell extracts from K. pneumoniae showed that both proteins could be immunoprecipitated by antisera to either NIFA or NIFL, implying the formation of a complex (13). This is consistent with the requirement for a stoichiometric concentration of each protein for effective inhibition of NIFA activity in vivo (10–12) and in vitro (2). Recently we have demonstrated the existence of a complex between A. vinelandii NIFL and NIFA in vitro by cochromatography in the presence of adenosine nucleotides (17). Using truncated fragments and isolated domains of NIFL and NIFA, we showed that the N-terminal domain of NIFA and the C-terminal domain of NIFL are involved in the ADP-dependent stimulation of NIFL-NIFA complex formation. We have now employed protease footprinting experiments to identify amino acid sequences involved in the interactions occurring between NIFA and NIFL during complex formation in the presence of adenosine nucleotides. We show here that changes in the protease sensitivity of the Q linker regions of both proteins occur in the NIFL-NIFA complex. Using isolated domains of NIFA, we provide evidence that the central domain of NIFA is sufficient to protect the trypsin sites in the NIFL Q linker and that the changes in trypsin sensitivity in the N-terminal and Q linker regions of NIFA apparently correlate with the ability of the protein to form a stable complex with NIFL as detected by cochromatography.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein purification.

The native forms of NIFL and NIFA were purified as described previously (2). The C-terminal hexahistidine-tagged forms of NIFL and truncated NIFA derivatives were purified by nickel affinity chromatography on Hi-Trap chelating columns (Pharmacia) as recommended by the manufacturer. For the native and histidine-tagged NIFA proteins, 50 mM potassium thiocyanate was routinely added to the chromatography buffers to inhibit precipitation.

Limited proteolysis.

Limited proteolysis was carried out in a mixture containing 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8), 100 mM potassium acetate, 8 mM magnesium acetate, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. Incubations were performed at 20°C in the presence or absence of 1 mM nucleotide. For the full-length proteins, the C-terminally tagged form of NIFL and nontagged NIFA were used. Truncated versions of NIFA were histidine tagged at the C terminus. NIFL and NIFA, individually or mixed together in a final volume of 100 μl, were preincubated with or without nucleotide for 5 min before initiation of digestion. Protease/protein weight ratios of 1:100, 1:20, and 1:5 were used for trypsin, chymotrypsin, and V8 protease, respectively. Twenty-five-microliter samples were removed at the time intervals indicated in the figure legends to tubes containing 12.5 μl of gel loading buffer (6% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 30% glycerol, 0.0003% bromophenol blue, 0.18 M Tris-chloride, 15% β-mercaptoethanol). Trypsin-chymotrypsin inhibitor from soybean was added in a ratio of 1:2 by weight, and the samples were heated to 100°C for 4 min before electrophoretic separation. For V8 protease, 0.5 mM 3,4-di-isocoumarin was used instead to inhibit proteolysis. Electrophoresis on 12.5, 14, or 15% polyacrylamide–SDS gels was carried out with either a Tris-glycine running buffer or a Tris-tricine buffer system to resolve low-molecular-weight peptides.

N-terminal amino acid sequencing.

Proteolytic digestion products were electrophoresed as described above and electroblotted onto Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). The membranes were briefly stained with 0.1% Coomassie brilliant blue R250 in 1% acetic acid and 50% methanol and destained in 50% methanol. Stained bands were excised from the dried membrane and subjected to Edman degradation analysis.

Western blotting.

Peptides were electroblotted as described above, and cross-reacting bands were detected with either polyclonal antisera to NIFL or monoclonal antisera to the six-His tag (Qiagen). Bands were visualized by using either the ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) system (Amersham) for chemiluminescent detection or 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) liquid substrate (Sigma) for visual staining.

NIFL-NIFA complex formation assay.

NIFL-NIFA complex formation assays were carried out exactly as described previously (17). Reactions were carried out in Tris-acetate buffer containing 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.9), 100 mM potassium acetate, and 8 mM magnesium acetate. NIFA and NIFL and their truncated derivatives were used at concentrations between 2 and 8 μM, as stated in the figure legends. Nucleotides were used at 1 mM unless stated otherwise. Reaction mixtures (final volume, 230 μl) were preincubated for 5 min at 30°C and then loaded onto a 1-ml Hi Trap chelating column (Pharmacia) that had been charged with NiCl2 and equilibrated in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.9), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 5% glycerol. Where nucleotides were present in the reaction mixtures, they were added at the same concentrations to the chromatography buffers to prevent disssociation of NIFL-NIFA complexes. Non-binding protein was washed from the column with the equilibration buffer, and bound material was then eluted with equilibration buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. Aliquots of the fractions were either mixed directly with SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer or pooled and concentrated before electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was carried out with 10% polyacrylamide–SDS gels unless stated otherwise in the text.

RESULTS

Limited trypsin digestion of NIFA, NIFL, and the NIFL-NIFA complex.

Purified NIFA and NIFL proteins were subjected to limited trypsin digestion, either individually or mixed together in the presence and absence of 1 mM MgADP. Peptides from the digested proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by N-terminal sequence analysis. Western blotting was also used to identify changes in the pattern of NIFL peptides obtained in the presence of NIFA (see Materials and Methods). Digestion of the NIFA protein alone was rapid in the absence of nucleotide, giving rise to a distinct band (A4 in Fig. 1), which migrated at approximately 40 kDa, and minor bands at 35 and 20 kDa (A5 and A6 in Fig. 1). In the presence of 1 mM MgADP, the rate of digestion was slowed, and the 35-kDa fragment, A5, was stabilized without the appearance of the band A6 at 20 kDa. N-terminal sequencing revealed that all three fragments arose from a cleavage at Arg-202 in the Q linker region of NIFA between the N-terminal and central domains. The domain structure of full-length NIFA and the schematic diagram of the tryptic digestion products are shown in Fig. 1B. The Q linker region is not well defined in Azotobacter vinelandii NIFA, but based on homology to the Q linker in Klebsiella pneumoniae NIFA (24) and the protease cleavage sites described in this work, we have assigned amino acid residues 189 to 205 to include this region. From the apparent molecular masses, the tryptic fragments obtained were assigned as the central and DNA binding domain, A4; the central domain alone, A5; and a central domain subfragment, A6 (Fig. 1B). Thus, MgADP binding to the NIFA central domain resulted in conformational changes which protected it from further proteolysis. N-terminal sequencing of some of the higher-molecular-mass fragments that were detected in the presence of MgADP revealed cleavages at Arg-8, Arg-70, and Arg-165 (A1 to -3, respectively, in Fig. 1B). These probably only represent a proportion of the cleavages which occur in the N-terminal domain, which is apparently very protease sensitive and is rapidly degraded by a series of cleavages at trypsin sites throughout the domain. The C-terminal DNA binding domain was also not observed as a discrete cleavage product. A pattern of trypsin digestion of NIFA similar to that obtained with 1 mM MgADP was observed with 1 mM MgATPγS, while only a slight protection of the 35-kDa band was obtained with higher concentrations (5 mM) of MgGTPγS (data not shown). Concentrations of 1 mM MgGDP, MgCTP, MgUTP, and MgAMP produced a pattern of trypsin digestion indistinguishable from that obtained in the absence of nucleotide (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A) Limited trypsin proteolysis of NIFA in the presence and absence of 1 mM MgADP. NIFA (final concentration, 3.75 μM) was incubated with trypsin (weight ratio, 1:100) for the times indicated, and reactions were analyzed with 15% polyacrylamide–SDS gels. (B) Schematic map of peptides generated by limited trypsin proteolysis of NIFA in the presence and absence of MgADP. Open rectangles represent the N-terminal domain of NIFA, where the full-length domain contains amino acid residues 1 to 190. Grey rectangles represent the central domain of NIFA, where the full-length domain contains amino acid residues 206 to 457. Black rectangles represent the C-terminal DNA binding domain containing amino acid residues 474 to 512. Thin black lines indicate the linker regions. The trypsin cleavage sites, which are shown beside each peptide, were determined by N-terminal sequence analysis, as described in Materials and Methods. Other structural features shown include the proposed Q linker between the N-terminal and central domains of NIFA (amino acid residues 189 to 205) and the proposed nucleotide binding site (amino acid residues 233 to 255).

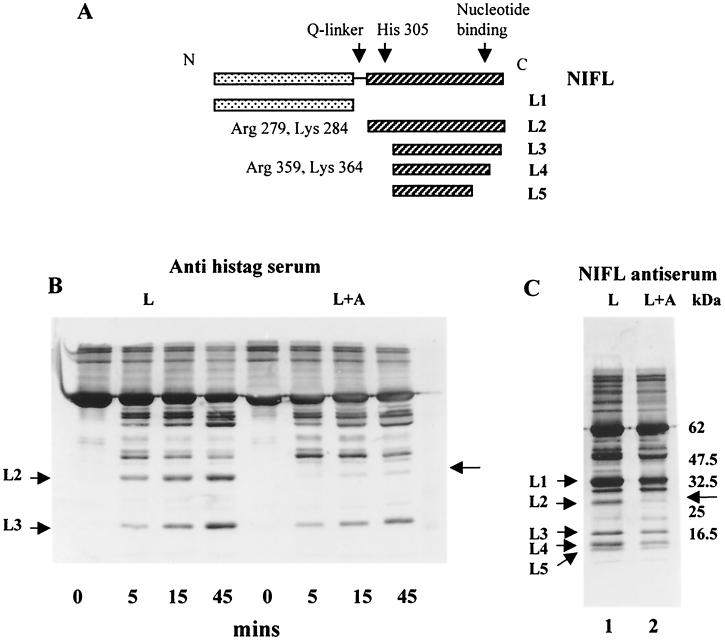

We have shown previously that adenosine nucleotide binding to NIFL induces conformational changes in the C-terminal domain of the protein (22). The patterns of trypsin digestion products obtained with NIFL in the presence of MgADP are summarized in Fig. 2A. In the absence of nucleotide, the NIFL N-terminal domain, band L1 in Fig. 2A, was stable in response to limited trypsin digestion, while the C-terminal domain was rapidly degraded. The presence of MgADP protected the C-terminal domain with the appearance of a 27-kDa peptide arising from cleavages at Arg-279 and Lys-284 in the Q linker (L2 in Fig. 2A). Lower-molecular-mass C-terminal peptides arising from cleavages at Arg-359 and Lys-364 were also protected by MgADP, migrating at 18, 15, and 14 kDa, respectively. (Fig. 2A, L3 to -5) (22). Bands corresponding to L1 to -5 were also detected on Western blots with anti-NIFL serum, as depicted in Fig. 2C.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of NIFA. Incubation mixtures containing 1 mM MgADP and NIFA or NIFL individually or mixed together to form a complex (final concentration, 1 μM) were digested with trypsin as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Schematic map of peptides generated by limited trypsin proteolysis of NIFL in the presence and absence of MgADP. Dotted rectangles represent the N-terminal domain of NIFL containing amino acid residues 1 to 274. The striped rectangles represent the C-terminal domain of NIFL, where the full-length domain contains amino acid residues 300 to 519. The thin black line represents the proposed Q linker between the N- and C-terminal domains of NIFL (amino acid residues 275 to 299). The proposed nucleotide binding sites (amino acid residues 445 to 456 and 478 to 482) are marked with an arrow. The trypsin cleavage sites, which are shown beside each peptide, were determined by N-terminal sequence analysis as described in Materials and Methods. (B). Western blot analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides detected with antiserum to the six-His tag (Anti histag). Twenty-five-microliter samples were removed at the times indicated, and the peptides were separated on 12.5% polyacrylamide–SDS gels. Western blotting was carried out as described in Materials and Methods with BCIP/NBT liquid substrate to detect the cross-reacting bands. (C) Western blot analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides detected with antiserum to NIFL. Samples were digested for 60 min and then processed as described for panel A. Lane 1, NIFL alone; lane 2, NIFL plus NIFA. The unlabeled arrows in panels B and C denote the positions of NIFL peptides not generated in the presence of NIFA. Bands labeled L1 to -5 are NIFL tryptic peptides as defined for panel A.

Additional changes in the pattern of tryptic peptides were observed when NIFA and NIFL were mixed together to form a complex in the presence of 1 mM MgADP. Equimolar amounts of C-terminally tagged NIFL and nontagged NIFA were used in the incubations as described in Materials and Methods. We have shown previously that the NIFL-NIFA complex can be isolated under these conditions by cochromatography assays (17). Figure 2B and C show Western blots of NIFL tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of NIFA detected with either antiserum to NIFL or antiserum to the six-His tag. The kinetics of partial trypsin digestion are shown in Fig. 2B, where the resulting peptides were detected with antiserum to the histidine tag. One major change in the pattern of NIFL tryptic peptides was observed in the presence of NIFA. The band corresponding to the NIFL peptide L2 did not appear when the NIFL-NIFA complex was formed, indicating that the Arg-279 and Lys-284 cleavages in the NIFL Q linker had been protected from trypsin cleavage (Fig. 2B). A similar result was obtained when antiserum to the whole NIFL protein was used to detect NIFL peptides (Fig. 2C). No other NIFL cleavage products appeared to be reproducibly altered by the presence of NIFA. Western blotting with Tricine gels to detect possible changes in lower-molecular-mass fragments did not reveal any further changes in NIFL peptides in the presence of NIFA (data not shown).

For NIFA, Western blotting with NIFA antiserum could not be used to detect tryptic peptides, because the antiserum was found to recognize only epitopes present at the C-terminal region of the protein, which was immediately cleaved on trypsin digestion. N-terminal sequence analysis of the NIFA fragments obtained after relatively long digestion times was essential to identify any potential changes in the pattern of NIFA tryptic peptides generated in the presence of NIFL. Figure 3B shows a Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peptides generated by trypsin digestion of NIFL and NIFA individually and of the proteins mixed together to form a complex in the presence of 1 mM MgADP. In the absence of NIFL, digestion of NIFA produced the 40- and 35-kDa fragments A4 and -5, respectively, described in the legend to Fig. 1, as a consequence of cleavage at Arg-202 in the Q linker region (Fig. 3B, lane2). In the presence of NIFL, a new, larger 45-kDa NIFA peptide, A7, was stabilized, arising from a cleavage at Arg-122 in the NIFA N-terminal domain. (Fig. 3B, lane 3). The NIFA peptide A4 was apparently not detectable in the presence of NIFL, because no sequence corresponding to this peptide was obtained from N-terminal sequencing of the 45-kDa band. From the apparent molecular mass, A7 consists of the last 80 amino acids of the N-terminal domain and the central domain of NIFA (Fig. 3E). Thus, both the Q linker region of NIFA and the trypsin sites in the adjacent N-terminal region were protected by NIFL. The change in NIFL identified on Western blots in Fig. 2 could also be seen on SDS-polyacrylamide gels with the absence of the NIFL peptide L2 clearly observable in the presence of NIFA (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 1 and 3). In control experiments with the NTRC protein instead of NIFA, there was no protection of the trypsin sites in the NIFL Q linker in the presence of NTRC and MgADP (data not shown). The NTRC Q linker, which is normally cleaved by trypsin at Arg-129 (9), was also not protected by NIFL (data not shown). Thus, the changes in trypsin sensitivity in the Q linker regions of both NIFL and NIFA are specific to the NIFL-NIFA complex.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of NIFL and NIFA tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of nucleotides. Incubations were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and the reactions were analyzed on 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. Peptides were generated by digestion with trypsin (weight ratio, 1:100) for 45 min at 20°C. (A) No nucleotide. (B) MgADP (1 mM). (C) MgATPγS (1 mM). (D) MgGTPγS. (E) Schematic representation of the NIFA peptide A7 protected in the presence of NIFL. Bands labeled A4 to -6 and L1 and -2 are shown in Fig. 1B and 2A, respectively. In each case, lane 1 is NIFL, lane 2 is NIFA, and lane 3 is NIFL plus NIFA.

Effect of ATPγS and GTPγS on limited proteolysis of the NIFL-NIFA complex.

We have shown previously that NIFL-NIFA complex formation was also observed with MgATPγS and MgGTPγS, the nonhydrolyzable analogues of ATP and GTP. However, MgATPγS was not as effective as MgADP at low concentrations, and with MgGTPγS, only low levels of complexes were detected (17). Limited trypsin digestion of NIFL and NIFA individually with 1 mM MgATPγS produced a pattern of peptides similar to that obtained with MgADP, except that the NIFL C-terminal peptide L2 was not observed under these conditions, as shown previously (22) (Fig. 3C, lane 1). The presence of NIFL caused protection of the same 45-kDa NIFA peptide, A7, as was observed with MgADP (Fig. 3C, lane 3). The rate of cleavage of the NIFL protein at the Q linker to give the NIFL N-terminal peptide L1 was also reduced in the presence of NIFA, and the full-length protein was protected (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 1 and 3). The affinity of MgGTPγS for NIFL and NIFA was apparently too weak for any protection from proteolysis to be detected, because the pattern of trypsin digestion obtained with 1 mM MgGTPγS was similar to that obtained in the absence of any nucleotide (compare Fig. 3A and D).

Limited proteolysis using chymotrypsin and V8 protease.

Chymotrypsin and V8 protease were employed to try to identify other potential changes in the pattern of peptides generated in the NIFL-NIFA complex compared to the patterns of the proteins alone. Figure 4A shows the pattern of proteolysis with chymotrypsin in the presence of 1 mM MgADP. The pattern of chymotrypsin digestion of NIFA was similar to that obtained with trypsin. A central domain fragment, which arose from a cleavage at Tyr-205 in the Q linker, was observed in the presence of MgADP (Fig. 4A and B, band A8). In the presence of NIFL, a larger NIFA peptide was generated, which arose from a cleavage at Tyr-126 in the N-terminal domain and was analogous to the 45-kDa fragment produced under the same conditions by trypsin (Fig. 4A and B, band A9). For NIFL, the major chymotryptic products in the presence of MgADP were two C-terminal domain peptides from cleavages at Phe-218 and Phe-252 (Fig. 4A and B, bands L6 and -7) and a 27-kDa amino-terminal peptide with the same N-terminal sequence as the full-length protein (Fig. 4A and B, L8). None of the NIFL peptides was altered by the presence of NIFA, either when visualized on stained gels (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 1 and 3) or by Western blotting with NIFL antiserum (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE of NIFL and NIFA peptides generated by digestion with chymotrypsin or V8 protease in the presence of 1 mM MgADP. (A) Digestion with chymotrypsin (weight ratio, 1:20) was for 45 min at 20°C. (B) Schematic representation of NIFL and NIFA chymotryptic peptides L6 to -8 and A8 and -9. (C) Digestion with V8 protease (weight ratio, 1:5) was for 60 min at 20°C. The bands labeled ● derive from V8 protease peptides. (D) Schematic representation of NIFA V8 peptides A10 and -11. Protein domains are represented as described for Fig. 1B and 2A. In panels A and C, lane 1 is NIFL, lane 2 is NIFA, and lane 3 is NIFL plus NIFA.

NIFA digestion by V8 protease in the presence of MgADP gave rise to two major digestion products (Fig. 4C, lane 2, bands A10 and -11): a 55-kDa peptide, A11, with an N-terminal sequence identical to that of the full-length protein; and a 35-kDa fragment, A10, arising from a cleavage in the Q linker at Glu-200. From the apparent molecular masses, these corresponded to the amino terminus plus the central domain and the NIFA central domain alone (Fig. 4D). In the presence of NIFL, the Q linker in NIFA was again protected from cleavage, resulting in accumulation of NIFA peptide A11, while the NIFA central domain peptide A10 was not observed (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 1 and 3). NIFL remained quite resistant to V8 protease digestion under the conditions of the assay, and no changes in NIFL peptides in the presence of NIFA were observed by Western blotting with NIFL antiserum.

The central domain of NIFA, NIFA(191–457), is sufficient to protect NIFL from trypsin cleavage in the Q linker.

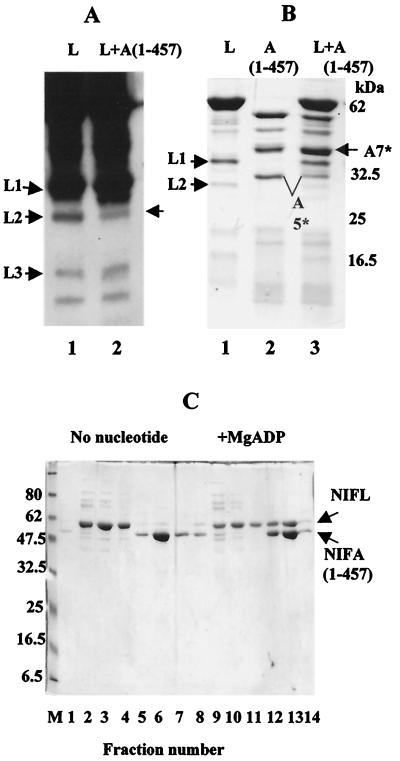

Previous experiments with a truncated form of NIFA lacking the N-terminal domain, NIFA(191–522), showed that this protein was unable to form a complex with full-length NIFL detectable by cochromatography (17). However, transcriptional activation by this truncated form of NIFA is inhibited by high concentrations of NIFL in the presence of ADP in vitro, implying that an interaction between the two proteins must still occur under these conditions (A. Sobczyk and R. Dixon, unpublished observations). We examined the ability of NIFA(191–522) and the isolated central domain of NIFA, NIFA(191–457), to protect the trypsin sites in the NIFL Q linker in the presence of MgADP. In the presence of both truncated NIFA proteins, protection of the trypsin cleavage sites Arg-279 and Lys-284 in NIFL could be observed in Western blotting experiments (Fig. 5A and B) and on Coomassie-stained SDS gels (Fig. 5C) (data not shown). NIFA(191–522) appeared to have a somewhat higher affinity for NIFL than did NIFA(191–457) and caused complete protection of the trypsin sites at the same protein concentration as the full-length protein (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 2 and 3). In the presence of NIFA(191–457), a low level of NIFL peptide L2 was still observed (Fig. 5B, lane 2). An apparent enhancement of the C-terminal NIFL peptide L3 was also observed in the presence of NIFA(191–457), although this was not detected on the Coomassie-stained gel. Full-length NIFL did not protect the trypsin cleavage site in the NIFA Q linker region present in both the truncated NIFA proteins, since the same NIFA central domain peptide, A5*, derived from cleavage at Arg-202, was observed in the presence and absence of NIFL with both NIFA proteins (Fig. 5C) (data not shown). Thus, the N-terminally deleted forms of NIFA are able to interact with NIFL and protect the NIFL Q linker from trypsin cleavage, even though such complexes are not sufficiently stable to allow detection by cochromatography.

FIG. 5.

Ability of amino-terminally truncated versions of NIFA to protect the Q linker of NIFL from trypsin cleavage. (A) Western blot analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of NIFA(191–522). Incubations were carried out as described for Fig. 2 with 1 mM MgADP. Proteins were present at a final concentration of 1 μM, and digestion was for 60 min at 20°C. Western blots were probed with antiserum to NIFL and detected with the ECL system. Lane 1, NIFL; lane 2, NIFL plus NIFA; lane 3, NIFL plus NIFA(191–522). The band labeled with a dot is due to a cross-reacting signal in the NIFA(191–522) preparation that is recognized by the NIFL antiserum. (B) Western blot analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of NIFA(191–457). Incubations and Western blotting were carried out as for panel A. Lane 1, NIFL; lane 2, NIFL plus NIFA(191–457). (C) SDS-PAGE of tryptic peptides generated by digestion of NIFL and NIFA(191–457). Incubation conditions were as for panel A. Samples were analyzed on 12.5% polyacrylaminde gels. Lane 1, NIFL; lane 2, NIFA(191–457); lane 3, NIFL plus NIFA(191–457). In each case, the unlabeled arrows denote the positions of NIFL peptides not generated in the presence of NIFA. NIFL tryptic peptides labeled L1 to -3 are shown in Fig. 2A. The NIFA tryptic peptide labeled A5* is analogous to peptide A5 shown in Fig.1, except that the C terminus has a six-His tag.

Role of the amino-terminal domain of NIFA in the formation of stable complexes with NIFL detectable by cochromatography.

The formation of NIFL-NIFA complexes sufficiently stable to be detected by cochromatography may depend on contacts or conformational changes in the N-terminal and Q linker regions of NIFA in addition to the interaction of the central domain of NIFA with NIFL described above. We investigated the ability of various N-terminal fragments of NIFA to form a complex with NIFL detectable by cochromatography as well as the ability of NIFL to protect the Q linker and adjacent N-terminal region of the NIFA fragments from trypsin digestion. The isolated N-terminal domain of NIFA alone, NIFA(1–203), or a longer fragment consisting of the N-terminal region, Q linker, and first 70 amino acids of the central domain, NIFA(1–275), did not form a complex with NIFL and was not protected by NIFL from trypsin cleavage. Neither did they protect the trypsin sites in the NIFL linker region (data not shown). However, a C-terminally deleted version of NIFA, NIFA(1–457), with its DNA binding domain deleted, but with an intact central domain, was competent to form a stable complex with NIFL in the presence of MgADP (Fig. 6C). However, with equimolar concentrations of the proteins, less NIFA(1–457) was bound to NIFL than was obtained with wild type NIFA, indicating a reduced affinity of NIFA(1–457) for NIFL (data not shown). NIFA(1–457) also protected the trypsin sites in the NIFL linker (Fig. 6A). In addition, NIFL protected the Q linker and the adjacent N-terminal region of this form of NIFA from trypsin cleavage (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 6.

Ability of NIFA(1–457) to interact with NIFL. (A) Western blot analysis of NIFL tryptic peptides generated in the presence and absence of NIFA(1–457). Incubations were carried out as described for Fig. 2 with 1 mM MgADP. Proteins were present at a final concentration of 1 μM, and digestion was for 60 min at 20°C. Western blots were probed with antiserum to NIFL and detected with the ECL system. Lane 1, NIFL; lane 2, NIFL plus NIFA(1–457). The unlabeled arrow denotes the peptide in NIFL not generated in the presence of NIFA. (B) SDS-PAGE of tryptic peptides generated by NIFL and NIFA(1–457). Incubations were carried out as described for panel A, except that digestion was for 30 min at 20°C. Samples were analyzed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (12.5% acrylamide). Lane 1, NIFL; lane 2, NIFA(1–457); lane 3, NIFL plus NIFA(1–457). NIFL tryptic peptides L1 to -3 are shown in Fig. 2A. NIFA peptides A5* and A7* are analogous to peptides A5 and A7, except they contain a six-His tag at the C terminus. (C) Complex formation between NIFL and NIFA(1–457). Complexes were formed and chromatographed as described previously (16). The nontagged form of NIFL (2.3 μM) was used with C-terminally tagged NIFA(1–457) (2.7 μM). MgADP was used at 1 mM. Electrophoresis was carried out on SDS-polyacylamide gels (12.5% polyacylamide). Lanes 2 to 4 and 9 to 11, wash fractions; lanes 5 to 7 and 12 to 14, fractions containing bound protein which eluted with 0.5 M imidazole.

DISCUSSION

The A. vinelandii NIFA and NIFL proteins have Q linker regions that are protease sensitive and nucleotide binding domains that are protected from protease digestion by the presence of adenosine nucleotides. Presumably nucleotide binding induces conformational changes in the respective domains, which result in the protease cleavage sites being less exposed to solvent. Both MgATPγS and MgADP protect the central domain of NIFA from protease digestion, as we have observed previously for the NTRC protein, a homologous ςN-dependent activator (9). However, the NIFA N-terminal domain is very trypsin sensitive compared to that of NTRC and may therefore be a more loosely folded domain. Under conditions in which NIFL and NIFA have been shown to form a complex in the presence of MgADP, the trypsin sensitivity of both Q linker regions changes. In addition, the N-terminal region of NIFA immediately adjacent to the Q linker is also protected by NIFL. The regions protected from trypsin digestion in the NIFL-NIFA complex are summarized in Fig. 7A.

FIG. 7.

(A) Summary of regions protected from trypsin digestion in the NIFL-NIFA complex formed in the presence of MgADP. The hatched areas signify protection from protease treatment. (B) Model of the interaction of NIFL with NIFA in the presence of MgADP.

The changes in trypsin sensitivity may be due to the linker regions undergoing a conformational change in response to protein contacts elsewhere in the proteins or may be due to direct protein-protein contacts involving these surfaces of NIFL and NIFA. Q linker regions have been identified at the boundaries of distinct structural domains in a number of bacterial signal transduction proteins (24). Whether the linker regions themselves have an active role in signal transduction or merely act as a tether between interacting domains of the proteins remains to be determined. In K. pneumoniae, extension of the NIFA Q linker region by four and eight amino acids did not affect the transcriptional activity of the protein in vivo, but regulation by NIFL was not tested (24). Linker regions in other multidomain response regulator proteins have been identified as having a potential role in signal transduction from one domain to another. Changes in protease sensitivity of the linker region of the response regulator OmpR have recently been reported in response to both phosphorylation of the N-terminal domain and DNA binding by the C-terminal domain (1).

The region of NIFL protected by NIFA appears to be localized to sites close to the NIFL Q linker. The chymotrypsin sites located at Phe-252 and Phe-218, 27 and 61 amino acids, respectively, upstream of the trypsin sites in the linker, appear unaffected by the presence of NIFA, as do the trypsin sites at Arg-359 and Lys-364, 80 amino acids downstream of the linker sites. In A. vinelandii NIFL, the histidine at position 305 is analogous to the highly conserved histidine residue, which is autophosphorylated in bona fide members of the family of histidine protein kinase (19). Although the NIFL-NIFA pair are not typical members of the two-component signal transduction protein family, the location of the conserved histidine residue near the Q linker suggests that this region may be a candidate for interaction with NIFA, since in orthodox systems, the modified histidine is likely to approach the receiver domain of the response regulator to effect phosphotransfer (18). However, mutations in His-305 in A. vinelandii NIFL resulted in proteins that were still able to inhibit NIFA activity in vivo, implying that this residue is not itself crucial for NIFL function, including interaction with NIFA (23). The region surrounding His-305 contains a number of residues conserved in the known NIFL proteins, and it is possible that this region of NIFL may have evolved the function of interaction with the activator. Using cochromatography assays in vitro, we showed previously that a C-terminal subdomain of A. vinelandii NIFL, NIFL(360–519), was unable to bind to NIFA in the presence of MgADP, but that a longer derivative, NIFL(147–519), which included the linker and surrounding region, was competent to bind NIFA (17). Recently an interaction between the C-terminal domain of A. vinelandii NIFL containing sequences from Glu-257 to the end of the protein and the central domain of NIFA has been demonstrated in vivo by using the yeast two-hybrid system (16). Taken together, these results indicate that the site of NIFA interaction is likely to be located between amino acids 260 and 360 in A. vinelandii NIFL. Experiments with a subdomain of NIFL incorporating this region, NIFL(256–356), were unable to demonstrate any interaction with NIFA (T. Money and S. Austin, unpublished observations). However, this is not unexpected, because NIFL-NIFA complexes are only observed in our assays in the presence of nucleotide binding, and this NIFL fragment lacks the nucleotide binding sites.

Evidence to date suggests that NIFL contacts the central domain of NIFA. The central domains of both A. vinelandii and K. pneumoniae NIFA activate transcription in vitro, and this activity is inhibited by NIFL, indicating that an interaction is taking place (3; J. Barrett and R. Dixon, unpublished observations). As described above, the interaction demonstrated in vivo with the yeast two-hybrid system was obtained with the central domain of NIFA alone (16). We show here that the isolated central domain of NIFA is competent to protect the Q linker of NIFL from trypsin digestion, indicating that NIFL contacts this domain of NIFA. There are no indications at present as to where the contact site(s) on the central domain might be located. The NIFA construct that contained the N-terminal domain and 70 amino acids of the central domain was unable to interact with NIFL, as determined by both trypsin protection and cochromatography assays, implying that the presence of this region is not sufficient to allow contact with NIFL.

The N-terminal domain of NIFA is required for a stable complex, detectable by cochromatography, to be formed with NIFL, and the changes in trypsin sensitivity of the NIFA Q linker and adjacent N-terminal domain appear to correlate with the ability of NIFA to form a stable complex with NIFL. The NIFA N-terminal domain is also required for NIFL to inhibit the ATPase activity of NIFA, indicating that this domain has a key regulatory role in controlling the catalytic domain of the protein (A. Sobczyk and R. Dixon, unpublished data). A model for the interaction of NIFA with NIFL incorporating these observations is presented in Fig. 7B. In this model, MgADP binding to the C-terminal domain of NIFL results in a conformational change in this domain and/or linker of NIFL, allowing it to interact with the central domain of NIFA, thereby inhibiting transcriptional activation. This contact results in the protection of the trypsin sites in the NIFL Q linker and is independent of the other domains of NIFA. When the NIFA N-terminal domain is present, further contacts or conformational changes can occur in the NIFA Q linker and adjacent amino terminus, giving rise to altered protease sensitivity. These appear to be dependent on the central domain contact with NIFL and may be responsible for the inhibition of NIFA ATPase activity, possibly by blocking the nucleotide binding site in the central domain. The affinity of the proteins in this complex is strong enough for it to be detected by cochromatography. In the absence of the N-terminal domain of NIFA, the central domain contact with NIFL can still be made and transcription is inhibited. However, without the extra contacts or conformational changes via the NIFA N-terminal and Q linker regions, the affinity of the complex is not strong enough to be detected by cochromatography.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to Mike Naldrett for N-terminal sequence analysis of the protease cleavage products. We also thank Gary Sawers and Mike Merrick for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames S K, Frankema N, Kenney L J. C-terminal DNA binding stimulates N-terminal phosphorylation of the outer membrane protein regulator OmpR from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11792–11797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin S, Buck M, Cannon W, Eydmann T, Dixon R. Purification and in vitro activities of the native nitrogen fixation control proteins NIFA and NIFL. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3460–3465. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3460-3465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger D K, Naberhaus F, Kustu S. The isolated catalytic domain of NifA, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein, activates transcription in vitro: activation is inhibited by NifL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:103–107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco G, Drummond M, Woodley P, Kennedy C. Sequence and molecular analysis of the nifL gene of Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:869–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive NIFL-NIFA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in gamma-proteobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond H M, Contreras A, Mitchenall L A. The function of isolated domains and chimaeric proteins constructed from the transcriptional activators NifA and NtrC of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:29–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond M H, Wootton J C. Sequence of nifL from Klebsiella pneumoniae: mode of action and relationship to two families of regulatory proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eydmann T, Söderbäck E, Jones T, Hill S, Austin S, Dixon R. Transcriptional activation of the nitrogenase promoter in vitro: adenosine nucleotides are required for inhibition of NIFA activity by NIFL. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1186–1195. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1186-1195.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farez-Vidal E M, Wilson T J, Davidson B E, Howlett G J, Austin S, Dixon R A. Effector-induced self-association and conformational changes in the enhancer-binding protein NTRC. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:779–788. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Govantes F, Andujar E, Santero E. Mechanism of translational coupling in the nifLA operon of Klebsiella pneumoniae. EMBO J. 1998;17:2368–2377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govantes F, Molina-López J A, Santero E. Mechanism of coordinated synthesis of the antagonistic regulatory proteins NifL and NifA of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6817–6823. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6817-6823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govantes F, Santero E. Transcription termination within the regulatory nifLA operon of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:447–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson N, Austin S A, Dixon R A. Role of metal ions in negative regulation of nitrogen fixation by the nifL gene product from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;216:484–491. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill S, Austin S, Eydmann T, Jones T, Dixon R. Azotobacter vinelandii NIFL is a flavoprotein that modulates transcriptional activation of nitrogen-fixation genes via a redox-sensitive switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2143–2148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H S, Berger D K, Kustu S. Activity of purified NIFA, a transcriptional activator of nitrogen fixation genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei S, Pulakat L, Gavini N. Genetic analysis of nif regulatory genes by utilizing the yeast two-hybrid system detected formation of a NifL-NifA complex that is implicated in regulated expression of nif genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6535–6539. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6535-6539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Money T, Jones T, Dixon R, Austin S. Isolation and properties of the complex between the enhancer binding protein NIFA and the sensor NIFL. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4461–4468. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4461-4468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park H, Saha S K, Inouye M. Two-domain reconstitution of a functional protein histidine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6728–6732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacterial signalling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz R A. NifL of Klebsiella pneumoniae carries an N-terminally bound FAD cofactor, which is not directly required for the inhibitory function of NifL. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz R A, He L, Kustu S. Iron is required to relieve inhibitory effects of NifL on transcriptional activation by NifA in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4679–4687. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4679-4687.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soderback E, Reyes-Ramirez F, Eydmann T, Austin S, Hill S, Dixon R. The redox and fixed nitrogen-responsive regulatory protein NIFL from Azotobacter vinelandii comprises discrete flavin and nucleotide-binding domains. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:179–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodley P, Drummond M. Redundancy of the conserved His residue in Azotobacter vinelandii NifL, a histidine autokinase homologue which regulates transcription of nitrogen fixation genes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wootton J C, Drummond M. The Q linker: a class of interdomain sequences found in bacterial multidomain regulatory proteins. Protein Eng. 1989;2:535–543. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.7.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]