Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the role of the oomycete Phytophthora × cambivora in the decline affecting European beech (Fagus sylvatica) in the Nebrodi Regional Park (Sicily, southern Italy). In a survey of a beech forest stand in the heart of the park, Phytophthora × cambivora was the sole Phytophthora species recovered from the rhizosphere soil and fine roots of trees. Both A1 and A2 mating type isolates were found. Direct isolation from the stem bark of trees showing severe decline symptoms and bleeding stem cankers yielded exclusively P. gonapodyides, usually considered as an opportunistic pathogen. The mean inoculum density of P. × cambivora in the rhizosphere soil, as determined using the soil dilution plating method and expressed in terms of colony forming units (cfus) per gm of soil, the isolation frequency using leaf baiting, and the percentage of infected fibrous roots from 20 randomly selected beech trees with severe decline symptoms (50 to 100 foliage transparency classes) were 31.7 cfus, 80%, and 48.6%, respectively. These were significantly higher than the corresponding mean values of 20 asymptomatic or slightly declining trees, suggesting P. × cambivora is a major factor responsible for the decline in the surveyed stand.

Keywords: Fagus sylvatica, Phytophthora gonapodyides, root rot, bleeding cankers, nature reserve, leaf-baiting, mating type, ITS, Cox I, phylogenetic analysis

1. Introduction

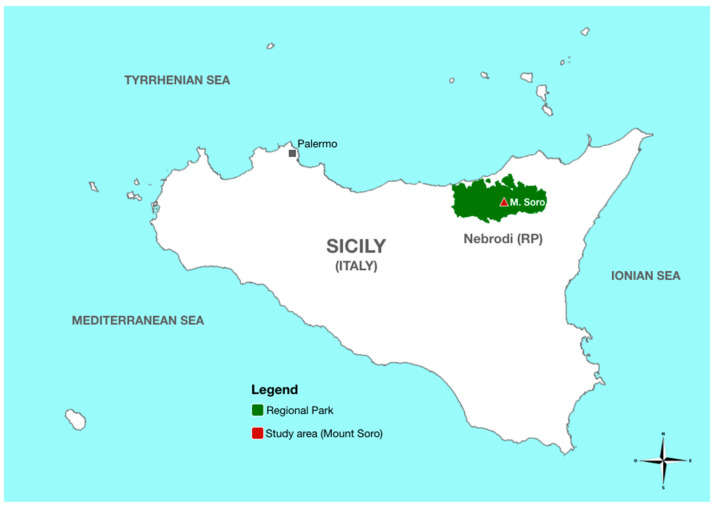

The Nebrodi Regional Park (RP), spanning nearly 86,000 ha, is the largest protected natural area (PNA) in Sicily (southern Italy) (Figure 1). According to the classification proposed by IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland), this park is included in the management category IV, encompassing PNAs aimed at protecting particular species or habitats [1]. The Nebrodi RP comprises diverse altitudinal zones ranging from coastal areas of the Tyrrhenian Sea, a few meters above sea level (a.s.l.), to Mount Soro (1847 m a.s.l.), which is the highest peak of the Nebrodi mountain range. At over 1200 m a.s.l., the vegetation of the Nebrodi RP is of the supra-Mediterranean type and includes forest stands dominated by European beech (Fagus sylvatica, family Fagaceae) (Figure 2), which are considered the southernmost limit of the natural distribution range of beech in Europe [2]. During the last decades beech stands in the Nebrodi RP are experiencing a severe decline and dieback of uncertain etiology. A similar decline of European beech in central Europe was imputed to the combined effect of climatic extremes and infections by Phytophthora species [3]. The hybrid species Phytophthora × cambivora (formerly P. cambivora) and other soil-borne Phytophthora species were reported to be associated with decline and bleeding stem cankers of European beech in Europe and the USA [4,5,6,7,8,9]. A recent study provided circumstantial evidence the infections by Phytophthora species are a major factor inciting the decline of European beech stands in Austria [10]. Phytophthora × cambivora was the prevalent Phytophthora species recovered from both bark cankers and rhizosphere soil of declining beech trees in this country. Moreover, it was found that the geological substrate influenced the distribution of this pathogen, which was exclusively found on geological substrates forming acidic soils with high contents of clay and sand, with a tendency for temporary waterlogging [10]. In a previous survey of PNAs in Sicily, P. × cambivora was found to be widespread in beech and oak stands of the Nebrodi RP and was the Phytophthora species recovered most frequently from the rhizosphere soil of declining beech and oak trees [11]. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the interaction between root infections by this Phytophthora species and climate change is the main factor responsible for the decline of European beech in the Nebrodi RP [12]. In Italy, and more generally in central and southeastern Europe, P. × cambivora is also the prevalent Phytophthora species responsible for ink disease of chestnut (Castanea sativa), a species of the same family as beech. In recent surveys, it was recovered, although occasionally, from the soil of declining forests of cork oak (Quercus suber) in Sardinia and from the rhizosphere soil of diverse species of oak and holly (Ilex aquifolium) in the Madonie RP, in Sicily [11,13,14,15,16]. Despite several lines of circumstantial evidence suggesting a major role of P. × cambivora as a stressor inciting the decline of beech stands of the Nebrodi RP, no conclusive evidence of this has been provided. The objective of this study was to verify the hypothesis that infections by P. × cambivora are responsible for the decline of beech trees in the Nebrodi RP. To this aim, the relationship between the severity of decline, the presence of P. × cambivora in the soil, the incidence of fine root infections, and the quantity of inoculum of this oomycete in the rhizosphere soil of beech trees in a representative beech stand in the heart of the RP was investigated.

Figure 1.

Geophysical map of Sicily with detail of the study area.

Figure 2.

A group of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) trees with severe symptoms of decline on the shore of a seasonal water basin in the Nebrodi Regional Park (Sicily, southern Italy).

2. Materials and Methods

Sampling activities were carried out from the last week of May to the first week of June 2020 in an almost pure, mature (>60 years old) beech forest stand of Nebrodi RP. A circular area (about 28 km2), with a diameter of around 6 km, was ideally delimited around Mount Soro (37°55′53′′ N, 14°41′39′′ E), in the municipality of Cesarò, province of Messina (ME), Sicily, southern Italy. It also encompassed the high altitude Biviere Lake (37°57′11′′ N, 14°42′52′′ E), in the same municipality, and the high altitude Maulazzo Lake (37°56′31′′ N, 14°40′18′′ E), in the municipality of Alcara li Fusi (ME). The geological nature of the soil was marly claystone. Individual scattered trees or groups of trees showed severe decline symptoms. Overall, samples were taken from 40 beech trees of the same age and size (around 60–70 years old and 20–25 m in height, respectively): 20 trees were apparently healthy or with mild symptoms of canopy thinning, while 20 showed severe symptoms of decline, including canopy thinning, twig and branch dieback, leaf yellowing, extensive dieback of the whole crown, and, in a few cases (five trees), bleeding stem cankers (Figure 3). The trees were separated into two groups based on the severity of decline symptoms, which was rated visually according to the classification of the crown condition (defoliation and foliage transparency) by Schomacher et al. and Eichhorn et al. [17,18]. Trees within the 0 to 25 foliage transparency classes were considered healthy, while trees within the 50 to 100 foliage transparency classes were included in the group of declining trees. The 40 trees were randomly selected across the study area. However, all the 40 selected trees were at least 150 m apart from each other to exclude the clustering of data and the small-scale effect of the sampling site. Sampled trees were georeferenced using a portable GPS tracker (GPS AT-17; Autoseeker Electronics Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China), to avoid sampling bias and sampling overlapping.

Figure 3.

Severely declining trees of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) on the shore of Maulazzo Lake in the Nebrodi Regional Park (Sicily, southern Italy).

2.1. Sampling, Isolation, and Quantitative Determination of Phytophthora

Rhizosphere soil samples, including fine roots, were collected under the canopy of the 40 selected beech trees after the removal of the upper organic soil layer (ca. 5–10 cm). Soil sampling and isolation were performed according to [11,19,20]: four soil cores were collected from each tree, 50–150 cm away from the stem base, and were bulked together (about 2 L). Two subsamples of about 500 mL were used for baiting tests that were performed in a walk-in growth chamber with 12 h natural day light at 20 °C. Each soil sample was placed in a plastic container and flooded with distilled water. Young leaves of carob-tree (Ceratonia siliqua) and oak (Quercus spp.) floated over flooded soil were used as baits. Organic debris floating on the water surface was removed prior to placing the bait leaflets. After 24–48 h incubation, leaves developing necrotic areas were checked under the light microscope at ×80 magnification for Phytophthora sporangia, and then leaf pieces (size 2 mm) from necrotic lesions were plated in Petri dishes onto selective PARPNH agar medium, which consisted of 100 mL V8 juice (Campbell Grocery Products Ltd., Ashford, UK), 15 g agar, 3 g CaCO3, 200 mg ampicillin, 10 mg rifampicin, 25 mg pentachloronitrobenzene (PCNB), 50 mg nystatin, 50 mg hymexazol, and 1 L of deionized water. Petri dishes were incubated at 20 °C in the dark. Outgrowing Phytophthora hyphae were transferred onto V8 juice agar (V8A) under the stereomicroscope.

For direct isolation of Phytophthora from roots, a soil subsample of about 1 L was sieved to separate fine roots. Roots were randomly selected, washed with tap water, rinsed with distilled water, blotted dry, and cut into small segments (5–6 mm). Root segments were plated in Petri dishes onto selective PARPNH agar medium (8 segments per Petri dish and 10 Petri dishes with each soil sample). Petri dishes were incubated at 20 °C in the dark. Phytophthora colonies were subcultured on V8 juice agar (V8A).

A dilution-plate technique was used for the quantitative determination of Phytophthora inoculum in the soil. An aliquot of 100 mg from each original soil sample was suspended in 1 L of sterile distilled water (s.d.w.). The suspension was mixed on a stirrer, and, while it was still stirring, it was pipetted into empty Petri dishes (1 mL per Petri dish and 10 dishes for each sample). Selective PARPNH agar medium was poured into the dishes at super fusion temperature (around 43 °C). The dishes were gently rotated to mix the soil suspension uniformly with the selective agar medium, and, after solidification of the medium, they were incubated at 20 °C in the dark. Colonies of Phytophthora were counted after three and six days of incubation. Randomly selected colonies were subcultured on PARPNH agar medium and subsequently on V8A for identification. Results were expressed in terms of colony forming units (cfu) g-1 of soil and were corrected by calculating the oven-dry weight of two subsamples (20 mg each) for each original soil sample analyzed.

For direct isolation from bleeding stem cankers, bark pieces (around 10–15 cm in length), including phloem and cambium, were excised from active advancing front of cankers, wrapped tightly with wetted paper, placed in a plastic bag, and taken to the laboratory. Before isolation, they were rinsed with tap water and blotted dry with sterile filter paper. Small bark pieces (2 mm) were picked up with a sterile scalpel and plated in Petri dishes onto selective PARPNH agar medium. Petri dishes were incubated at 20 °C in the dark. Outgrowing Phytophthora hyphae were subcultured on V8A.

All the Phytophthora isolates obtained from baiting or direct isolation from soil, roots, and stem bark were maintained on V8A in the dark at a temperature of 6 °C.

2.2. Morphological Identification of Isolates

Morphological features and colony morphology of isolates were determined on colonies grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) and V8A at 24–26 °C in the dark, according to standard procedures as described by Riolo et al. [19]. Cardinal temperatures for radial growth were determined by growing the isolates on PDA in Petri dishes (9 cm diam.) and incubating the dishes at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 °C (all ± 0.5 °C), in the dark, with four replicates per each isolate and temperature value. Sporangia production was stimulated with the method described by Santilli et al. [21]. Fragments of 2 mm were cut from the growing edge of 7-day-old cultures grown in Petri dishes (15 mm diam.) on V8A at 27 °C in the dark, and they were placed in a 5 cm diameter Petri dish and flooded with non-sterile soil extract water (200 g soil suspended in 1 L of deionized water for 24 h at room temperature and then filtered). After incubation, at 27 °C in the dark for 24–48 h, dimensions and morphological features of 50 mature sporangia of each isolate were determined at ×400 magnification.

2.3. Molecular Identification of Isolates

The DNA of the pure cultures of isolates obtained from soil, roots, and bark was extracted by using PowerPlant Pro DNA isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA), in accordance with the protocol of the manufacturer. The DNA was preserved at −20 °C. The molecular identification of Phytophthora species was performed by the analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and the mitochondrially encoded cytochrome oxidase subunit I (Cox I) regions. DNA for ITS sequencing was amplified using forward primer ITS6 and reverse primer ITS4 [22,23]. The PCR amplification mix and thermocycler conditions were in accordance with Cooke et al. [22]. All PCRs were carried out in a 25 µL reaction mix containing PCR buffer (1×), dNTP mix (0.2 mM), MgCl2 (1.5 mM), forward and reverse primers (0.5 mM each), Taq DNA Polymerase (1 U), and 100 ng of DNA. The thermocycler conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and then 72 °C for 10 min. Cox I was amplified for sequencing using the primers COXF4N and COXR4N [24]. Amplification reactions were conducted in final concentrations of genomic DNA at 1 to 3 ng µL−1, 200 μM dNTP (2.0 mM), 0.4 μM ITS6 Phy-8b and Phy-10b primers, 2% glycerol, 3 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer, and AmpliTaq polymerase (Applied Biosystems) at 0.05 units of µL−1. PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 1 min at 95 °C, 1 min of annealing at 65.5 °C, and 1 min of extension at 72 °C; followed by 1 extension cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were detected in 1% agarose gel and sequenced in both directions by an external service (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Derived sequences were analyzed using FinchTV v.1.4.0 (Geospiza Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) [25]. For species identification, blast searches [26] in the Phytophthora Database [27], GenBank [28], and in a local database containing sequences of ex-type or key isolates from published studies were performed. Isolates were assigned to a species, when their sequences were 99–100% identical to a reference isolate.

2.4. Mating Type of Isolates

The mating type of P. × cambivora isolates was determined in dual cultures with A1 and A2 tester strains. The test was performed in Petri dishes (diameter 90 mm) on V8A. The dishes were incubated at 25 °C in the dark and, after 15 d of incubation, were examined under the microscope for the formation of gametangia. Preliminary, 20 randomly selected P. × cambivora isolates obtained from baits were paired, in all possible combinations, with four tester strains of P. nicotianae from the collection of the Molecular Plant Pathology laboratory (University of Catania), C301 (A2 type), Pandorea 2c (A2 type), Ferrara R11 (A1 type), and Serravalle 1 (A1 type), as characterized in previous studies [29,30]. Two P. × cambivora isolates of A1 mating type and two of A2 mating type were randomly selected among the 10 isolates tested preliminarily and were used as tester strains in subsequent tests to determine the mating type of randomly selected P. × cambivora isolates recovered from leaf baits, roots, and soil. Indirect tests for sexual compatibility type were carried out using 0.2 μm polycarbonate membrane, as described by Ko (1978) [31]. Isolates were grown on 15 mL HSA (amended with 30 mg β-sitosterol L−1) in 9 cm diameter plastic Petri dishes for 3 days at 20 °C in the dark. All isolates were paired with themselves in all possible combinations and with A1 (Correa8) and A2 (STA24) mating types of P. nicotianae [30].

2.5. Statistical Analysis of Results

Data from individual scattered trees or groups of trees were analyzed using RStudio v.1.2.5. To perform correlation analysis, which measures a linear dependence between two variables, Pearson correlation test was performed. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level. Log and angular transformations were applied to the values of ID and percentage of infected fine roots, respectively, to obtain a normal distribution. Analysis of variance revealed no significant differences in inoculum density and infected roots among all trees analyzed (p value > 0.01), except between inoculum density and infected roots of trees with mild symptoms (p = 0.001027). K-means cluster analysis was performed on standardized values of the three variables (proportion of infected fibrous roots, foliage transparency, and inoculum density), using the packages cluster of RStudio v.1.2.5 [32].

3. Results

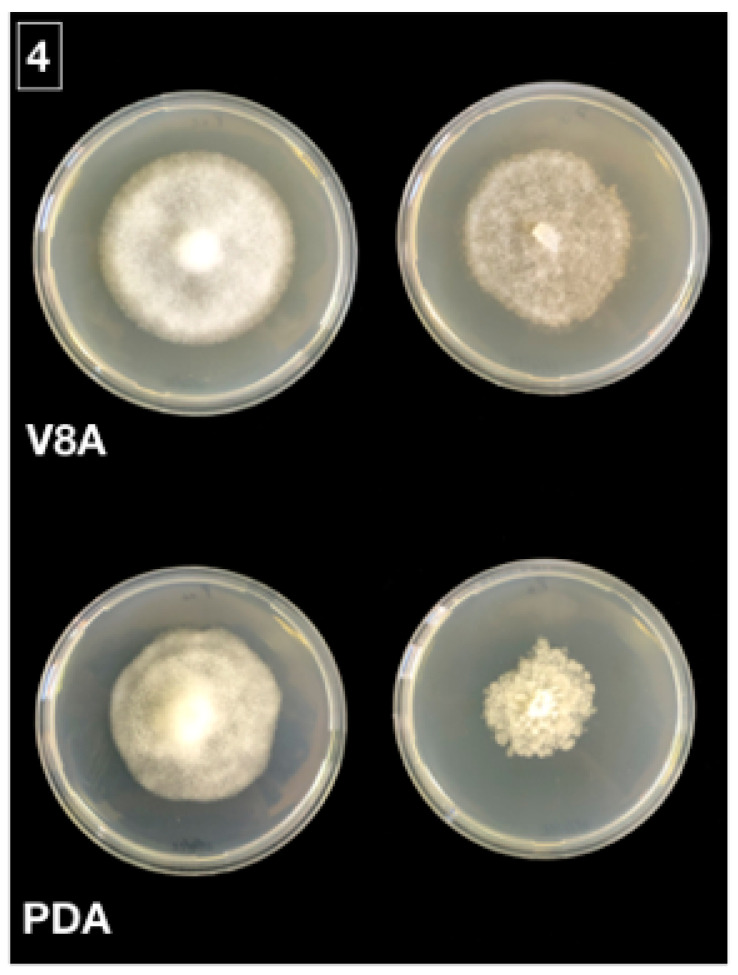

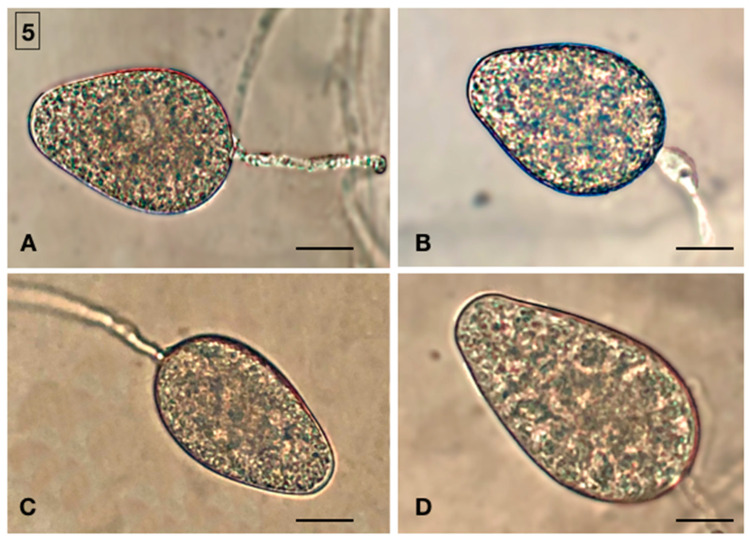

Isolations from leaf baits, roots, and rhizosphere soil of symptomatic and asymptomatic beech trees sampled in the forest stand of Mount Soro in the Nebrodi RP yielded Phytophthora isolates all with the same colony morphology. In total, 30 (10 from leaf baits, 10 from fine roots and 10 from soil) randomly selected, single-hypha tip isolates were characterized. The isolates formed uniform, woolly colonies with a coralloid mycelium on both V8 agar (V8A) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Figure 4). Minimum and maximum temperature were below 5 °C and above 35 °C, respectively, with an optimum at 25 °C. Plugs from cultures grown on V8A flooded with non-sterile soil extract produced ovoid, elongated, less frequently ellipsoid, obpyriform, or limoniform, non papillate to semipapillate, persistent, and internally proliferating sporangia (Figure 5). Sporangium dimensions averaged 65 ± 11 × 40 ± 6 μm. Chlamydospores were absent. All isolates were heterothallic and formed antheridia, oogonia, and oospores only, when paired with reference P. nicotianae isolates of the A1 and A2 mating types. In paired cultures, antheridia were amphyginous, elongated, and very frequently bicellular. Oogonia showed a tapering base, and their outer wall was ornamented (bullate or verrucose), which is a distinctive character of very few Phytophthora species, including P. × cambivora. Oospores were globose, thick-walled, and plerotic, with a large central ooplast and an average diameter of 35 ± 4 µm. The proportion of A1 and A2 mating types was quite balanced among isolates from leaf baits (4 and 6 isolates out of 10, respectively) and soil (5 and 5 isolates out of 10, respectively), while the A2 type largely prevailed over the A1 type among isolates from roots (8 out of 10 isolates).

Figure 4.

Colony morphologies of Phytophthora × cambivora (upper row and bottom row to the left; isolate MSK1A) and P. gonapodyides (upper row and bottom row to the right; isolate MSC1A) after 4 days growth at 20 °C in the dark on V8A and PDA.

Figure 5.

Sporangia of Phytophthora × cambivora and P. gonapodyides. (A,B) Non-papillate, persistent, and ovoid sporangia of P. × cambivora (C,D). Non-papillate, persistent, and ellipsoid sporangia of P. gonapodyides. Scale bar: 25 μm.

Direct isolations from the bark of bleeding cankers yielded a Phytophthora species morphologically different from that recovered from the soil and roots. Beech trees with symptoms of bleeding stem cankers, five in all, were always near the shore of lakes or ponds and showed a high incidence of root rot. Cankers were on the main stem at the height of 60–120 cm from the soil, and bark pieces excised from the margin of active cankers were used for isolations. Eight randomly selected, single-hypha tip isolates obtained from these trees were characterized. Isolates of this Phytophthora species formed colonies with a rosette growth pattern on both V8A and PDA. They grew at 5 and 30 °C but did not grow at 35 °C. Optimum temperature for growth was at 25 °C. Chlamydospores were absent. Plugs from cultures grown on V8A flooded with non-sterile soil extract produced mycelium with globose hyphal swellings and non-papillate, obpyriform, internally and externally proliferating, and persistent sporangia. Sporangium dimensions averaged 50 ± 11 × 30 ± 5 μm. Isolates were self-sterile and did not form sexual structures when paired with tester strains of either the A1 or A2 P. nicotianae mating types.

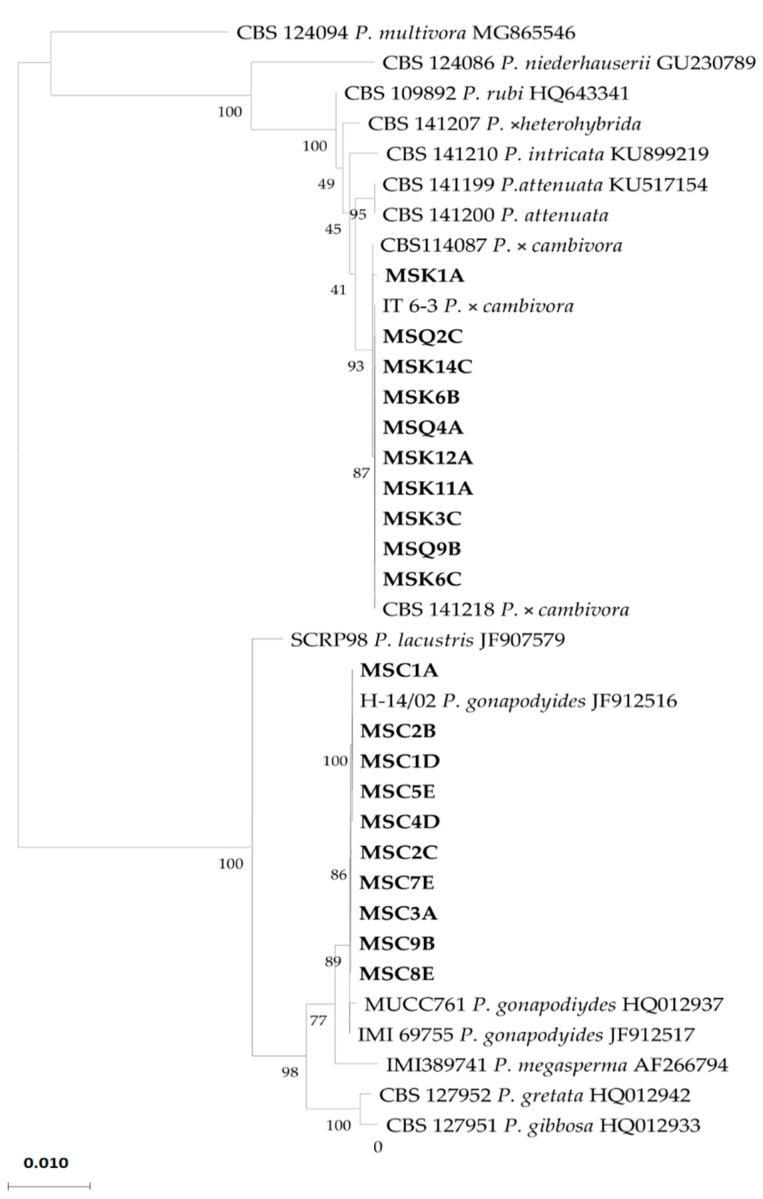

Amplification and sequencing of the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) regions of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of the isolates of the first species recovered from the beech trees revealed 99%100% identity with the sequence of the ex-neotype isolate of P. × cambivora (CBS141218), while isolates of the second species showed 100% identity with a reference isolate (IMI 69755) of P. gonapodyides [9]. In the tree obtained by the phylogenetic analysis of the combined data set of sequences from ITS and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (Cox I) regions of isolates recovered from beech and sequences of Phytophthora species used as references, all isolates from the roots and soil clustered (bootstrap values of 1000 replicate) with the reference isolates of P. × cambivora, while isolates from the stem bark clustered with the reference isolates of P. gonapodyides (Figure 6). The accession numbers of the ITS and Cox I sequences of the isolates of P. × cambivora and P. gonapodyides sourced from the bark, roots, and rhizosphere soil of the beech trees in the Mount Soro forest stand deposited in GenBank are listed in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and Cox I multilocus phylogenetic tree developed using the maximum likelihood method, based on the Tamura–Nei model. The tree with the greatest log likelihood (-5740.14) is shown. Relationships between the isolates from Fagus sylvatica sourced in southern Italy (in bold) and the CBS/IMI reference isolates of Phytophthora gonapodyides, P. × cambivora, and other Phytophthora spp. are shown.

Table 1.

Isolates of Phytophthora sourced from rhizosphere soil and different tissues (fine roots and stem bark) of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) trees in the Nebrodi Regional Park of Sicily, Italy, as characterized in this study.

| Isolate | Phytophthora Species | Source | Accession Numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | Cox I | |||

| MSK1A | Phytophthora × cambivora | Soil and roots a | ON186623 | ON227269 |

| MSK6C | P.× cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186624 | ON227270 |

| MSQ9B | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186625 | ON227271 |

| MSK3C | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186626 | ON227272 |

| MSK11A | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186627 | ON227273 |

| MSK12A | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186628 | ON227274 |

| MSQ4A | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186629 | ON227275 |

| MSK6B | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186630 | ON227276 |

| MSK14C | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186631 | ON227277 |

| MSQ2C | P. × cambivora | Soil and roots | ON186632 | ON227278 |

| MSC1A | P gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186633 | ON227279 |

| MSC2B | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186634 | ON227280 |

| MSC1D | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186635 | ON227281 |

| MSC5E | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186636 | ON227282 |

| MSC4D | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186637 | ON227283 |

| MSC2C | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186638 | ON227284 |

| MSC7E | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186639 | ON227285 |

| MSC3A | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186640 | ON227286 |

| MSC9B | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186641 | ON227287 |

| MSC8E | P. gonapodyides | Stem bark | ON186642 | ON227288 |

a Rhizosphere soil and fine roots.

There was a significant positive correlation (p ˂ 0.01) between the severity of beech tree decline and both the inoculum density of P. × cambivora in rhizosphere soil and the proportion of fine roots infected by this pathogen (Table 2). In general, P. × cambivora was recovered in 30 trees out of a total of 40 trees sampled, while P. gonapodyides was isolated in only 5 trees out of the total trees that were analyzed. Accordingly, when the 40 sampled beech trees were separated into two groups, i.e., severely declining trees and trees with mild symptoms of decline, the mean inoculum density and the proportion of infected fibrous roots were significantly higher in the former group. Mean values of inoculum density in the two groups of trees were 31.7 (range from 0 to 103) and 3.1 (range from 0 to 12) cfu/g of dry soil, respectively, while the mean proportions of infected fibrous roots were 48.6 (range from 2.5 to 88.75) and 16.1 (range from 0% to 66.5%), respectively. Moreover, the proportion of soil samples that were positive for P. × cambivora to the leaf-baiting test was significantly higher in severely declining trees than in healthy trees, 80% and 45%, respectively. Overall, in three soil samples, the presence of P. × cambivora was detected only with the leaf baiting, while in six samples, it was detected only with the dilution-plating assay. Eight samples, three from healthy trees and five from declining trees, resulted negative for Phytophthora with both assay methods. Not surprisingly, the mean proportion of fine roots infected by P. × cambivora in these eight samples was very low (6.25 ± 1.71%), even lower than the overall mean proportion of infected fine roots detected in healthy trees. The difference was significant according to the Student’s t-test at p < 0.01. Phytophthora × cambivora was always isolated from the fine roots and rhizosphere soil of the five trees showing stem bleeding cankers, from which P. gonapodyides was consistently recovered. The inoculum density of P. × cambivora in the rhizosphere soil of these five trees ranged from 45 to 84 cfus, while the proportion of fine roots infected by this pathogen ranged from 63% to 89%.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between foliage transparency, as determined according to the classification of Schomacher et al. [17] and Eichhorn et al. [18], and inoculum density of Phytophthora × cambivora, in terms of cfu/g of soil and proportion (%) of fine roots infected by P. × cambivora, in 40 randomly selected beech trees.

| Foliage Transparency |

Inoculum Density (cfu/g of Soil) | Proportion of Infected Fibrous Roots (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of infected fibrous roots (%) | 0.466 ** | 0.508 ** | 1 |

| Foliage transparency | 1 | 0.548 ** | 0.466 ** |

| Inoculum density (cfu/g of soil) |

0.548 ** | 1 | 0.508 ** |

** Significant for p ˂ 0.01.

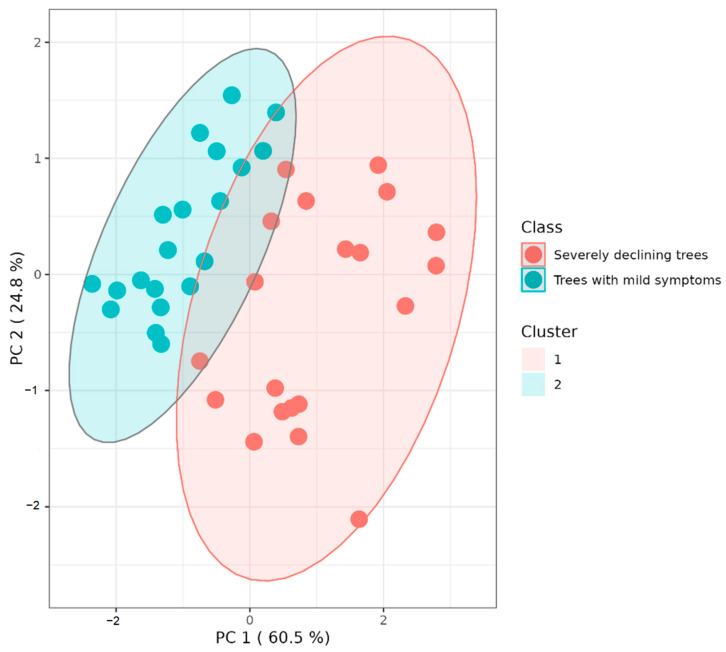

K-means cluster analysis of standardized values of the three examined variables (proportion of beech roots infected by P. × cambivora, foliage transparency of beech trees, and inoculum density of P. × cambivora in rhizosphere soil of beech trees) grouped the samples into two clusters: trees with mild symptoms and severely declining trees. The sum of the principal component (PC) reached 85.3% of the total variance, of which PC1 (proportion of infected fibrous roots) represented 60.5% and PC2 (inoculum density) represented 24.8% of the total variances. In the area comprised within the two clusters, samples with symptoms intermediate to the two classes examined were aggregated (Figure 7), indicating that foliage transparency is a discriminant between the two classes.

Figure 7.

K-means cluster analysis of standardized values of three variables (proportion of beech roots infected by Phytophtora × cambivora, foliage transparency of beech trees, and inoculum density of P. × cambivora in rhizosphere soil of beech trees) grouping the samples into two clusters: trees with mild symptoms (blue dots) and severely declining trees (red dots).

4. Discussion

The present study, complementing a previous large-scale survey of PNAs in Sicily [11] and focusing on a single large beech stand on the slopes of Mount Soro, provided evidence that the oomycete P. × cambivora, in ITS Phtytophthora clade 7 [33], was widespread throughout the intensively surveyed stand, which confirms that this invasive oomycete has become established in the area of the Nebrodi RP. Moreover, the balanced presence of both mating types in the beech stand of Mount Soro is circumstantial evidence that P. × cambivora is reproducing sexually. Quite interestingly, a significant correlation came out between the health status of beech trees, as determined by visual inspection of the canopy, and both the amount of P. × cambivora inoculum in the rhizosphere soil of the beech trees and the percentage of the fine roots infected by this pathogen. K-means cluster analysis of the standardized values of the proportion of the beech roots infected by Phytophthora x cambivora, foliage transparency of the trees, and inoculum density of P. × cambivora in the rhizosphere soil, clearly discriminated beech trees with mild symptoms from severely declining trees. This strongly supports the hypothesis of a major role of P. × cambivora in the decline of beech stands in the Nebrodi RP [12]. More generally, it confirms that the destruction of the root system is a major driving factor of beech decline in sites where aggressive species of Phytophthora are present, provided that the environmental conditions are favorable to infections by these pathogens [10,34].

Numerous studies highlighted the association between the presence of soil-borne Phytophthora species and the decline of beech forests in Europe and the USA [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,35,36,37,38]. So far, 16 Phytophthora species, in addition to P. × cambivora, were recovered from beech forests across Europe. Most of them, including P. × cambivora, are considered pathogens of exotic origin, probably introduced because of human activities, while only a few species, such as P. pseudosyringae, P. tyrrhenica, and P. vulcanica, are supposed to be native to Europe [9,10,39,40,41]. Not all Phytophthora species recovered from beech stands in Europe are aggressive pathogens, and some species were found only sporadically [9,10]. Phytophthora × cambivora was the species most frequently associated with beech forest decline in Europe, which is amongst the most aggressive ones [10]; it has an almost worldwide distribution, is polyphagous, and can adapt to different environmental conditions. Moreover, Jung et al. [9] confirm the aggressiveness of Phytophthora × cambivora in pathogenicity tests on Fagus sylvatica seedlings, using P. x cambivora as a positive control. However, in a recent study aimed at investigating the association between the Phytophthora species and beech decline in Austria, P. × cambivora was exclusively recovered from geological substrates forming acidic soils rich in clay and sand [10], which is the same type of soil as that of the Mount Soro site. In beech stands in Austria and Bavaria (southern Germany), the altitudinal limits of P. × cambivora were 637 and 750 m a.s.l., respectively [10], while, at the Mount Soro site, this species was found up to an altitude of around 1800 m a.s.l., which is not surprising as the Nebrodi RP is located at the southernmost latitude of the geographical range of beech stands in Europe. In a previous survey of PNAs in Sicily, P. × cambivora was recovered from beech and oak stands at an altitude ranging from 660 to 1783 m a.s.l. [11]. Previous studies investigating the root status of declining trees in beech stands infested by Phytophthora species revealed a significant correlation between crown transparency and root health [10,42]. However, none of the previous studies related the amount of inoculum of P. × cambivora in the rhizosphere soil with both the severity of decline and root rot in mature beech trees. The present study is the first attempt to determine these relationships, with the aim of providing better insights into the role of P. × cambivora as the causative agent of beech decline in the Nebrodi RP.

The relationship between the level of Phytophthora population in the soil and Phytophthora root rot was thoroughly investigated in horticultural crops and ornamentals [43,44]. In a few cases, soil sampling protocols and threshold inoculum levels were defined, in order to forecast the risk of disease in relation to the susceptibility of the host-plant, to, thus, decide the interventions to prevent the disease or evaluate the effectiveness of disease management strategies [45,46]. The relative simplicity of agricultural systems facilitated the study of soil Phytophthora populations. These systems shared some fundamental characteristics, including the uniformity of the genotype and age of the plants, a low Phytophthora evenness, with the presence of a single or few species, and the virtual absence of perennial weeds. The presence of perennial weeds may interfere with the isolation, as some of them are potential hosts of other Phytophthora species or alternative hosts of the Phytophthora species associated preferentially with the tree crop. In this respect, the surveyed beech stand of Mount Soro could be compared with an agricultural system, as it was an almost pure beech stand, the beech trees were all of the same age, P. × cambivora was the sole or at least the largely prevalent Phytophthora species recovered from the soil, and the understory was almost absent due to the shadowing effect of trees in a very dense forest.

Quantitative studies of soil populations of Phytophthora were also performed in forest ecosystems to investigate the putative role of these oomycetes as a major contributing factor of the diebacks of white oak (Quercus alba) in the USA [47,48,49]. However, the results were, at least in part, contradictory. Declining white oak at sites infested by P. cinnamomi had significantly lower amounts of fine roots than white oak trees from noninfected sites, indicating a significant relationship between the presence of P. cinnamomi and white oak decline, while other Phytophthora species, including P. × cambivora, were recovered only occasionally [48]. When an intensive soil sampling was carried out, the ID of P. cinnamomi in the soil samples collected from declining white oak trees was significantly greater than the ID in soil samples from asymptomatic trees, so the authors hypothesized that this was the cause of the reduced number of fine roots observed in the declining trees [47,48]. However, when the sampling was scaled up and included a greater variety of sites within a wider geographical and climatic range, no constant association was found between the health status of tree crown, the presence of P. cinnamomi or other Phytophthora species, and their inoculum level in the soil, suggesting infections by Phytophthora species are not the only factor involved in the decline of white oak forests. Conversely, the health status of fine roots was related to the presence of P. cinnamomi, although only in sites located in hardiness zones five and six, as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture, suggesting climate plays a key role in the interaction between this oomycete and white oak trees [49]. Overall, from these results, the conclusion can be drawn that the decline of oak stands may be regarded as a complex disease sensu [50]. Several authors stressed the role of both local conditions and global warming in the triggering of beech and oak declines caused by Phytophthora species in Europe and the USA [3,4,10,12,42,51,52,53]. Others, while not excluding the role of environmental factors, assumed the mere presence in soil of invasive Phytophthora species, such as P. cinnamomi, P. × cambivora, P. plurivora, or P. quercina, is per se a potential health risk for oaks and beeches, due to their extreme susceptibility to Phytophthora root rot [10,54,55,56,57]. It is noteworthy that beech trees are less drought-tolerant than oaks and, consequently, are more vulnerable to the root damage caused by infections of the Phytophthora species [10].

Phytophthora × cambivora is the most common causal agent of bleeding stem cankers on beech trees in Europe. However, this symptom, associated sporadically with the decline of beech trees, may also be incited by other species of Phytophthora [10,36,37,58]. In the present study, only P. gonapodyides, in ITS Phytophthora clade 6, was recovered from the bark of bleeding stem cankers. This species is globally widespread and is mostly associated with aquatic or semi-aquatic habitats [59]. As a matter of fact, in Sicily, it occurs frequently in water courses and riparian vegetation [9,19]. Although it was reported as causal agent of bleeding stem cankers of beech in Sweden [60], it is generally regarded as an opportunistic pathogen. Consistently, in the present study, this Phytophthora species was isolated from the severely declining trees with a high percentage of their fine roots infected by the more aggressive P. × cambivora, on the banks of lakes or ponds subjected to temporarily flooding or prolonged soil waterlogging. A recent study aimed at evaluating the impact of infections by P. cinnamomi on the rhizosphere microbiome of avocado (Persea americana) showed Phytophthora root rot modifies the composition of the root-associated microbial community, favoring opportunistic fungal pathogens [61]. Extending the concept to beech decline, it may be inferred that root infections by P. × cambivora may predispose the beech trees to the infections of opportunistic pathogens, such as P. gonapodyides, or secondary invaders, which exacerbate the severity of decline but are not the primary pathogens. Therefore, in some cases the role of these fungi in the beech decline could be overestimated. By contrast, the role of Phytophthora species in complex diseases in general tends to be underestimated, as the isolation of these oomycetes on culture media commonly used for fungi is challenging, due to the poor competitive saprophytic ability of these pathogens.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that in a large beech stand in the Nebrodi RP, in Sicily, Italy, the severity of decline of trees, as determined by a visual inspection of the canopy, was related to the health status of the root system and the quantity of inoculum of P. × cambivora in the rhizosphere soil of trees, suggesting this oomycete has a primary role in determining the decline. This does not exclude other factors playing a significant role in the interaction between the host plant and the pathogen. The effect of global warming in triggering or favoring the beech decline across Europe has been hypothesized. However, the role of climate as the driving factor of the decline of beech trees in this area at the extreme southern edge of the geographical range of beech forests in Europe was out of the scope of this study. More research is needed to investigate the association between the site conditions and the incidence and severity of decline.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Luca Ferlito, former Special Commissioner of the Nebrodi Regional Park, for their helpful collaboration during the survey, and Ann Davis for revising the English text.

Author Contributions

M.R., F.A. and S.O.C. conceived the study; F.A., M.R. and S.C.T. carried out the survey and in field sampling; M.R., F.A. and S.C.T. performed the experiments in the laboratory; A.P. and S.O.C. supervised the experiments in the laboratory; M.R., A.P., F.A., M.F. and S.O.C. elaborated the data; A.P. and S.O.C. provided the funds; M.R. and S.O.C. wrote the first draft of the text; all the authors contributed to review, editing, and commenting on the final version of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the University of Catania, Italy, “Investigation of phytopathological problems of the main Sicilian productive contexts and eco-sustainable defense strategies (MEDIT-ECO)”- PiaCeRi-PIAno di inCEntivi per la Ricerca di Ateneo 2020-22 linea 2” “5A722192155”; F.A. has been granted a fellowship by the “PON “RICERCA E INNOVAZIONE” 2014–2020, Azione II—Obiettivo Specifico 1b—Progetto “Miglioramento delle produzioni agroalimentari mediterranee in condizioni di carenza di risorse idriche—WATER4AGRIFOOD”, cod. CUP: B64I20000160005.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dudley N., Shadie P., Stolton S. Guidelines for Applying Protected Areas Management Categories Including Iucn Wcpa Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Type. IUCN; Gland, Switzerland: 2013. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolte A., Czajkowshi T., Kompa T. The north-eastern distribution range of European beech—A review. Forestry. 2007;80:413–429. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpm028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung T. Beech decline in Central Europe driven by the interaction between Phytophthora infections and climatic extremes. For. Pathol. 2009;39:73–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung T., Hudler G.W., Griffiths H.M., Fleischmann F., Oßwald W. Involvement of Phytophthora spp. in the decline of European beech in Europe and the USA. Mycologist. 2005;19:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson A.H., Weiland J.E., Hudler G.W. Prevalence, distribution and identification of Phytophthora species from bleeding canker on European beech. J. Environ. Hort. 2010;28:150–158. doi: 10.24266/0738-2898-28.3.150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepniewska H., Dłuszyňski J. Incidence of Phytophthora cambivora in bleeding lesions on beech stems in selected forest stands in south-eastern Poland. Phytopathologia. 2010;56:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milenković I., Keca N., Karadžić D., Nowakowska J.A., Borys M., Sikora K., Oszako T. Incidence of Phytophthora species in beech stands in Serbia. Folia For. Pol. 2012;54:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telfer K.H., Brurberg M.B., Herrero M.L., Stensvand A., Talgø V. Phytophthora cambivora found on beech in Norway. For. Pathol. 2015;45:415–425. doi: 10.1111/efp.12215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung T., Jung M.H., Cacciola S.O., Cech T., Bakonyi J., Seress D., Mosca S., Schena L., Seddaiu S., Pane A., et al. Multiple new cryptic pathogenic Phytophthora species from Fagaceae forests in Austria, Italy and Portugal. IMA Fungus. 2017;8:219–244. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2017.08.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corcobado T., Cech T.L., Brandstetter M., Daxer A., Hüttler C., Kudláček T., Jung M.H., Jung T. Decline of European Beech in Austria: Involvement of Phytophthora spp. and contributing biotic and abiotic factors. Forests. 2020;11:895. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung T., La Spada F., Pane A., Aloi F., Evoli M., Horta Jung M., Scanu B., Faedda R., Rizza C., Puglisi I., et al. Diversity and distribution of Phytophthora species in protected natural areas in Sicily. Forests. 2019;10:259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacciola S.O., Gullino M.L. Emerging and re-emerging fungus and oomycete soil-borne plant diseases in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2019;58:451–472. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vettraino A.M., Morel O., Perlerou C., Robin C., Diamandis S., Vannini A. Occurrence and distribution of Phytophthora species associated with ink disease of chestnut in Europe. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2005;111:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s10658-004-1882-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vettraino A.M., Natili G., Anselmi N., Vannini A. Recovery and pathogenicity of Phytophthora species associated with a resurgence of ink disease in Castanea sativa in Italy. Plant Path. 2001;50:90–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2001.00528.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung T., Pérez-Sierra A., Durán A., Horta Jung M., Balci Y., Scanu B. Canker and decline diseases caused by soil- and airborne Phytophthora species in forests and woodlands. Persoonia. 2018;40:182–220. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2018.40.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seddaiu S., Brandano A., Ruiu P.A., Sechi C., Scanu B. An overview of Phytophthora species inhabiting declining Quercus suber stands in Sardinia (Italy) Forests. 2020;11:971. doi: 10.3390/f11090971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schomacher M.E., Zarnoch S.J., Bechtold W.A., Latelle D.J., Burkman W.G., Cox S.M. Crown-Condition Classification: A Guide to Data Collection and Analysis. United States Department of Agriculture—Forest Service, Southern Research Station; Asheville, NC, USA: 2007. p. 78. General Technical Report SRS 102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichhorn J., Roskams P., Potočić N., Timmermann V., Ferretti M., Mues V., Szepesi A., Durrant D., Seletković I., Schröck H.-W., et al. Part IV: Visual assessment of crown condition and damaging agents. In: UNECE ICP Forests Programme Co-ordinating Centre, editor. Manual on Methods and Criteria for Harmonized Sampling, Assessment, Monitoring and Analysis of the Effects of Air Pollution on Forests. Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems; Eberswalde, Germany: 2016. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]. p. 50. + Annex. Available online: http://www.icp-forests.org/manual.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riolo M., Aloi F., La Spada F., Sciandrello S., Moricca S., Santilli E., Pane A., Cacciola S.O. Diversity of Phytophthora communities across different types of Mediterranean vegetation in a nature reserve area. Forests. 2020;11:853. doi: 10.3390/f11080853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung T., Horta Jung M., Scanu B., Seress D., Kovács D.M., Maia C., Pérez-Sierra A., Chang T.T., Chandelier A., Heungens A., et al. Six new Phytophthora species from ITS Clade 7a including two sexually functional heterothallic hybrid species detected in natural ecosystems in Taiwan. Persoonia. 2017;38:100–135. doi: 10.3767/003158517X693615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santilli E., Riolo M., La Spada F., Pane A., Cacciola S.O. First report of root rot caused by Phytophthora bilorbang on Olea europaea in Italy. Plants. 2020;9:826. doi: 10.3390/plants9070826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke D.E., Drenth A., Duncan J.M., Wagels G., Brasier C.M. A molecular phylogeny of Phytophthora and related oomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000;30:17–32. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Volume 18. Academic Press Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroon L.P.N.M., Bakker F.T., van den Bosch G.B.M., Bonants P.J.M., Flier W.G. Phylogenetic analysis of Phytophthora species based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2004;41:766–782. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FinchTV v.1.4.0. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]. Available online: https://digitalworldbiology.com/FinchTV.

- 26.BLAST Searches. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]; Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

- 27.Phytophthora Database. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]. Available online: http://www.phytophthoradb.org/

- 28.GenBank. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/

- 29.Mammella M.A., Cacciola S.O., Martin F., Schena L. Genetic characterization of Phytophthora nicotianae by the analysis of polymorphic regions of the mitochondrial DNA. Fungal Biol. 2011;115:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mammella M.A., Martin F.N., Cacciola S.O., Coffey M.D., Faedda R., Schena L. Analyses of the population structure in a global collection of Phytophthora nicotianae isolates inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Phytopathology. 2013;103:610–622. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-12-0263-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko W.H., Chang H.S., Su H.J. Isolates of Phytophthora cinnamomi from Taiwan as evidence for an Asian origin of the species. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1978;71:3. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(78)80080-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maechler M., Rousseeuw P., Struyf A., Hubert M., Hornik K. Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions, R Package Version 20.6. [(accessed on 20 May 2021)]. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster.

- 33.Grünwald N.J., Martin F.N., Larsen M.M., Sullivan C.M., Press C.M., Coffey M.D., Hansen E.M., Parke J.L. Phytophthora-ID.org: A sequence-based Phytophthora identification tool. Plant Dis. 2011;95:337–342. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-10-0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corcobado T., Vivas M., Moreno G., Solla A. Ectomycorrhizal symbiosis in declining and non-declining Quercus ilex trees infected with or free of Phytophthora cinnamomi. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014;324:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.03.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Day W.R. Root-rot of sweet chestnut and beech caused by species of Phytophthora. I. Cause and symptoms of disease: Its relation to soil conditions. Forestry. 1938;12:101–116. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.forestry.a062747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cacciola S.O., Motta E., Raudino F., Chimento A., Pane A., Magnano di San Lio G. Phytophthora pseudosyringae the causal agent of bleeding cankers of beech in central Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2005;87:289. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motta E., Annesi T., Pane A., Cooke D.E.L., Cacciola S.O. A new Phytophthora sp. causing a basal canker on beech in Italy. Plant Dis. 2003;87:1005. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.8.1005A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diana G., Pane A., Raudino F., Cooke D.E.L., Cacciola S.O., Magnano di San Lio G. 2006:A decline of beech trees caused by Phytophthora pseudosyringae in central Italy. In: Brasier C., Jung T., Osswald W., editors. Progress in Research on Phytophthora Diseases of Forest Trees, Proceedings of the 3rd International IUFRO Working Party 7.02.09 Meeting, Freising, Germany, 11–17 September 2004. Forest Research; Farnham, UK: 2006. pp. 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung T., Nechwatal J., Cooke D.E.L., Hartmann G., Blaschke M., Oßwald W.F., Duncan J.M., Delatour C. Phytophthora pseudosyringae sp. nov., a new species causing root and collar rot of deciduous tree species in Europe. Mycol. Res. 2003;107:772–789. doi: 10.1017/S0953756203008074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linzer R.E., Rizzo D.M., Cacciola S.O., Garbelotto M. AFLPs detect low genetic diversity for Phytophthora nemorosa and P. pseudosyringae in the US and Europe. Mycol. Res. 2009;113:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung T., Orlikowski L., Henricot B., Abad-Campos P., Aday A.G., Aguín Casal O., Bakonyi J., Cacciola S.O., Cech T., Chavarriaga D., et al. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. For. Pathol. 2016;46:134–163. doi: 10.1111/efp.12239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung T., Blaschke H., Osswald W. Involvement of Phytophthora species in Central European oak decline and the effect of site factors on the disease. Plant Pathol. 2000;49:706–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2000.00521.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson D.M. Residual activity of metalaxyl and population dynamic of Phytophthora cinnamomi in landscape beds of azalea. Plant Dis. 1987;71:886–891. doi: 10.1094/PD-71-0886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandler H.A., Timmer L.W., Graham J.H., Zitko S.E. Effect of fungicide applications on populations of Phytophthora parasitica and on feeder root densities and fruit yields of citrus trees. Plant Dis. 1989;73:902–906. doi: 10.1094/PD-73-0902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timmer L.W., Sandler H.A., Graham J.H., Zitko S.E. Sampling citrus orchards in Florida to estimate populations of Phytophthora parasitica. Phytopathol. 1988;78:940–944. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-78-940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cacciola S.O., Magnano di San Lio G. Management of citrus diseases caused by Phytophthora spp. In: Ciancio A., Mukerji K.G., editors. Integrated Management of Diseases Caused by Fungi, Phytoplasma and Bacteria. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagle A.M., Long R.P., Madden L.V., Bonello P. Association of Phytophthora cinnamomi with white oak decline in Southern Ohio. Plant Dis. 2010;94:1026–1034. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-8-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balci Y., Long R.P., Mansfield M., Balser D., MacDonald W.L. Involvement of Phytophthora species in white oak (Quercus alba) decline in southern Ohio. For. Pathol. 2010;40:430–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2009.00617.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McConnel M.E., Balci Y. Phytophthora cinnamomi as a contributor to white oak decline in mid-atlantic United States forests. Plant Dis. 2014;98:319–327. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-13-0649-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riolo M., La Spada F., Aloi F., Giusso del Galdo G., Santilli E., Pane A., Cacciola S.O. Phytophthora Diversity in a sentinel arboretum and in a nature reserve area. Biol. Life Sci. Forum. 2021;4:51. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brasier C.M. Phytophthora cinnamomi and oak decline in southern Europe Environmental constraints including climate change. Ann. Sci. For. 1996;53:347–358. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreira A.C., Martins J.M.S. Influence of site factors on the impact of Phytophthora cinnamomi in cork oak stands in Portugal. Forest Pathol. 2005;35:145–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sturrock R.N., Frankel S.J., Brown A.V., Hennon P.E., Kliejunas J.T., Lewis K.J., Worrall J.J., Woods A.J. Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:133–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02406.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung T., Cooke D.E.L., Blaschke H., Duncan J.M., Oßwald W. Phytophthora quercina sp. nov., causing root rot of European oaks. Mycol. Res. 1999;103:785–798. doi: 10.1017/S0953756298007734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunstan W.A., Rudman T., Shearer B.L., Moore N.A., Paap T., Calver M.C., Dell B., Hardy G.E.S.J. Containment and spot eradication of a highly destructive, invasive plant pathogen (Phytophthora cinnamomi) in natural ecosystems. Biol. Invasions. 2010;12:913–925. doi: 10.1007/s10530-009-9512-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serrano M.S., Rios P., Gonzales M., Sanchez M.E. Experimental minimum threshold for Phytophthora cinnamomi root disease expression on Quercus suber. Phytopath. Medit. 2015;54:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frisullo S., Lima G., Magnano di San Lio G., Camele I., Melissano L., Puglisi I., Pane A., Agosteo G.E., Prudente L., Cacciola S.O. Phytophthora cinnamomi involved in the decline of holm oak (Quercus ilex) stands in southern Italy. For. Sci. 2018;64:290–298. doi: 10.1093/forsci/fxx010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brasier C.M., Beales P.A., Denman S., Rose J. Phytophthora kernoviae sp. nov., an invasive pathogen causing bleeding stem lesions on forest trees and foliar necrosis of ornamentals in the UK. Mycol. Res. 2005;109:853–859. doi: 10.1017/S0953756205003357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erwin D.C., Ribeiro O.K. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide. APS Press—The American Phytopathological Society; St. Paul, MN, USA: 1996. pp. 258–261; 334–335. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cleary M., Blomquist M., Ghasemkhani M., Witzell J. First report of Phytophthora gonapodyides causing stem canker on European beech (Fagus sylvatica) in southern Sweden. Plant Dis. 2016;100:2174. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-16-0468-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solís-García I.A., Ceballos-Luna O., Cortazar-Murillo E.M., Desgarennes D., Garay-Serrano E., Patiño-Conde V., Guevara-Avendaño E., Méndez-Bravo A., Reverchon F. Phytophthora root rot modifies the composition of the avocado rhizosphere microbiome and increases the abundance of opportunistic fungal pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11:574110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.574110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.