Abstract

Background

Anticoagulation-free continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was recommended by the current clinical guideline for patients with increased bleeding risk and contraindications of citrate. Nevertheless, anticoagulation-free CRRT yielded heterogeneous filter lifespan. Furthermore, the specific cutoff values for traditional coagulation parameters to predict sufficient filter lifespan of anticoagulation-free CRRT have not yet been determined. The purpose of our present study was to develop and validate a model for predicting sufficient filter lifespan in anticoagulation-free CRRT patients.

Methods

Patients who underwent anticoagulation-free CRRT in our center between June 2013 and June 2019 were retrospectively included. The primary outcome was sufficient filter lifespan (≥24 h). Thirty-seven predictors were included for modeling based on their clinical significance and previous reports. The final model was developed by using multivariable logistic regression analysis and was validated in a separate external cohort.

Results

The development cohort included 170 patients. Sufficient filter lifespan was observed in 80 patients. Thirteen variables were independent predictors for sufficient filter lifespan by logistic regression: body temperature, mean arterial pressure, activated partial thromboplastin time, direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, blood urea nitrogen, vasopressor use, body mass index, white blood cell, platelet count, D-dimer, uric acid, and pH. The area under the curve (AUC) of the stepwise model and internal validation model was 0.82 (95% confidence interval [CI] [0.76–0.88]) and 0.8 (95% CI [0.74–0.87]), respectively. The positive predictive value and the negative predictive value of the stepwise model were 0.77 and 0.79, respectively. The validation cohort included 44 eligible patients and the AUC of the external validation model was 0.82 (95% CI [0.69–0.96]).

Conclusions

The use of a prediction model instead of an assessment based only on coagulation parameters could facilitate the identification of the patients with filter lifespan of ≥24 h when they accepted anticoagulation-free CRRT.

Keywords: Continuous renal replacement therapy, Anticoagulation, Bleeding, Filter failure, Prediction model

Introduction

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is the most commonly used renal support modality in the critical care setting [1]. Anticoagulation is a key intervention to maintain the patency of the extracorporeal circuit [2]. Unfractionated heparin is the most widely used anticoagulant for CRRT worldwide [3]. However, critically ill patients are commonly complicated with impaired coagulation or increased bleeding risk [4]. A platelet (PLT) count of <50 × 109/L was seen in 12–15% of the critically ill patients and a prolonged global coagulation time (i.e., prothrombin time or activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT]) in 14–28% [5]. The reported bleeding incidence in patients undergoing heparin anticoagulated CRRT ranged from 4 to 25% [6, 7]. Therefore, the increased bleeding risk limits the applicability of heparin [7]. Regional citrate anticoagulation (RCA) is gaining increasing popularity due to its advantage over heparin in terms of prolonged filter lifespan and reduced bleeding risk [8]. The KDIGO guideline recommended RCA as the preferred anticoagulation strategy in patients without citrate contraindications, including severe liver failure and shock with muscle hypoperfusion [4]. The reported incidence of liver dysfunction and shock with hypoperfusion in intensive care unit patients was 2–5% [9, 10] and 40% [11, 12], respectively. Therefore, a significant number of intensive care unit patients had the contraindications of both heparin and citrate. For these patients, CRRT was suggested to proceed without the use of any anticoagulant [4]. In clinical practice, approximately 33–50% patients did not receive any anticoagulants during CRRT [13, 14, 15]. The averaged or median filter lifespan of anticoagulation-free CRRT ranged from 10 to 40 h [16, 17, 18], which were associated with significant heterogeneity. For anticoagulation-free CRRT, 60% of the filters were replaced because of filter failure before the accomplishment of a treatment regimen (commonly 24 h) [19].

Several parameters, including PLT, international normalized ratio (INR), and APTT, were reported to be related to the filter lifespan in anticoagulation-free CRRT patients. However, the specific cutoff points have not been determined for these parameters to indicate the possibility of sufficient filter lifespan for anticoagulation-free CRRT [4]. To the best of our knowledge, there was no effective model to predict sufficient filter lifespan in anticoagulation-free CRRT patients as well [20]. The development of an effective prediction model for sufficient filter lifespan would be helpful for the individual choice of anticoagulation strategy for CRRT patients. Therefore, the aim of our present study is to develop a clinical prediction model to predict sufficient filter lifespan for a treatment regimen (commonly 24 h) in anticoagulation-free CRRT patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Our present study was a retrospective cohort study and was performed in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement [21] and the Declaration of Helsinki. Our present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Development Cohort

Critically ill patients who underwent CRRT between June 2013 and June 2019 in our center (a tertiary teaching hospital with >2,000 CRRT patients per year) were retrospectively screened. The inclusion criteria included (1) adult patients (≥18 years) and (2) received anticoagulation-free CRRT. Patients were excluded if they fulfilled any of the following criteria: (1) received systemic anticoagulation within 24 h prior to or during CRRT for indications other than CRRT; (2) received other extracorporeal therapies (i.e., plasmapheresis, plasma exchange, hemoperfusion, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) during CRRT; (3) switched to systemic heparin or RCA after the start of an anticoagulation-free CRRT regimen; (4) patients underwent CRRT via arteriovenous fistula; (5) patients with missing data of important parameters (i.e., liver function, coagulation parameters, or filter lifespan); (6) the first circuit was replaced within 24 h due to selective reasons (i.e., imaging procedures, transport, low blood pressure, resuscitation discharge, surgery, or death); or (7) the center venous catheter function was insufficient for the targeted blood flow.

Validation Cohort

A separate external validation cohort was retrospectively recruited to assess the generalizability of the prediction model. The patients who underwent CRRT between January 2018 and December 2019 in West China Hospital of Sichuan University were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria employed in the development cohort.

CRRT Protocol in the Development Cohort

Continuous venovenous hemofiltration was the modality routinely adopted during the study period. The machines used for CRRT were the Prismaflex System (Gambro) and DIAPACT (Braun), which were equipped with Multiflow-100 (0.9 m2, AN69 membrane) and AV600 (polysulfone, 1.4 m2; Fresenius) hollow-fiber filters, respectively. The vascular access was built by inserting a 13.5 F double lumen catheter into the femoral vein or jugular vein. Blood flow was maintained at 200 mL/min. Commercially available replacement fluid was infused at a rate of 2 L/h with a ratio of pre to postdilution of 1:1. In cases of large body size (weight >100 kg), the prescribed dose was set at 20–25 mL/kg/h according to the recommendations of the 2012 KDIGO guideline [4]. A bicarbonate buffered fluid was infused prefilter separately at an appropriate rate depending on the acid-base status of the patients. The ultrafiltration rate was adjusted according to the hemodynamic parameters and the goal of treatment.

CRRT Protocol in the Validation Cohort

Continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) was the sole CRRT modality used in the validation cohort. CVVHDF was performed using the Prismaflex System (Gambro) machine equipped with several types of filters, including ST150, M150, and M100. The parameters of CVVHDF were following: blood flow rate 200 mL/min; dialysate flow rate 1 L/h; and replacement fluid flow rate 1 L/h with pre-, post-, or hybrid dilution models.

Definitions

Illness severity was evaluated using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Increased bleeding risk [22] was defined according to the following criteria: (1) coagulopathy (APTT >60 s, INR >2, or PLT count <60 × 109/L); (2) active bleeding; (3) post-surgery within 24 h; or (4) experienced major bleeding within 48 h. Contraindications to citrate included severe liver failure (total bilirubin [Tb] >34.2 μmol/L) [23], shock with muscle hypoperfusion (serum lactate >2 mmol/L) [24], and hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mm Hg).

Outcomes

Sufficient filter lifespan was defined as filter lifespan ≥24 h. Filter lifespan was defined as the time interval (hours) between initiation and cessation of an individual circuit. Filter failure was confirmed by (1) transmembrane pressure >300 mm Hg, (2) visible clots, or (3) inability to operate the blood pump [25, 26].

Factors Included in the Analysis

Thirty-seven factors (online suppl. material 1, online suppl. Table 1; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000519409 for all online suppl. material) were included in the analysis based on their clinical significance and previous reports [27]. Data including demographic characteristics, admission diagnosis, pre-existing disease, illness severity, indications of CRRT, risk of bleeding, contraindications for citrate, laboratory tests, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive agents use, transfusion requirement, and CRRT protocol characteristics were collected from the patient medical records. In order to control confounding bias, only the first circuit in the first session was analyzed for patients who received several sessions of CRRT during 1 admission.

Missing Data

The missing data were addressed by mean imputation using SPSS (IBM Corporation) software version 24.

Statistical Analysis

Normal distribution and non-normal distribution continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range) and compared using Student's t test and the Wilcoxon test, respectively. For categorical variables, data were presented as counts (percentage) and compared using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. The filter survival probability at different time points was graphically analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves with Log-rank test.

All the candidate factors were included in a multivariable logistic regression model with the continuous variables retained on the original scale. The collinearity test was performed at first and variables with variance inflation factor >10 were eliminated. Thereafter, a stepwise approach was employed for the final model selection based upon Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [28]. We also developed a full model and a multivariable fractional polynomial (mfp) model. Nomograms [29] were constructed based on the results of the models. Discrimination and calibration of the models were assessed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and the calibration curve, respectively [30]. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) were calculated at the optimal cutoff values of the models which were identified at the maximum Youden Index. In addition to external validation, the performance of the models was internally validated by using bootstrapping (1,000 times). Statistical differences in the AUCs were compared using the Delong test [31]. A 2-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by using the R software (version 3.4.3).

Results

Model Development

Patients Characteristics

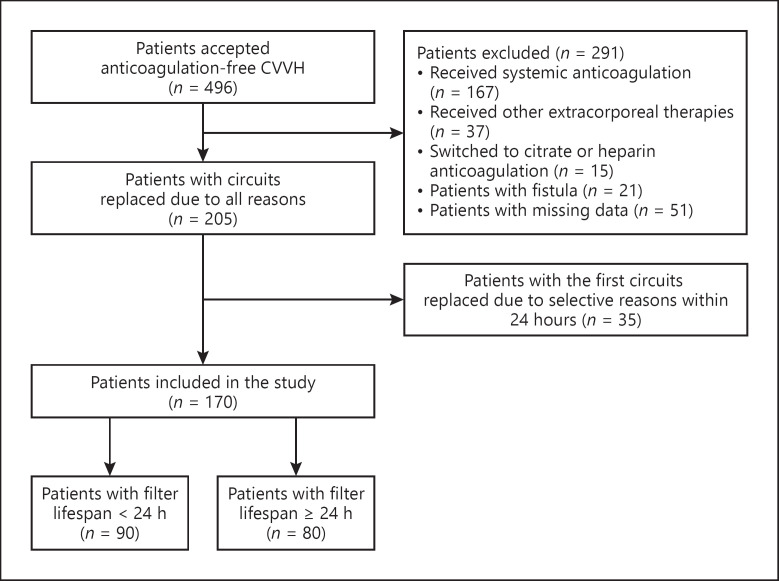

The development cohort included 170 patients and the patients inclusion flowchart is showed in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the development cohort are shown in Table 1. The reasons for increased bleeding risk and contraindications for citrate are detailed in online supplementary material 2, online supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

The participant flow diagram of the development cohort. CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; CVVH, continuous venovenous hemofiltration; RCA, regional citrate anticoagulation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the development and validation cohort at the time of starting CRRT

| Characteristics | Development cohort* (n = 170) | Validation cohort* (n = 44) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 52.7±15.6 | 52.3±17.3 | 0.88 |

| T, °C | 36.8 (36.5–37.4) | 36.7 (36.4–37.4) | 0.26 |

| Male sex | 120 (70.6) | 29 (66) | 0.54 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23±3.75 | 21.8 (20.2–23.8) | 0.06 |

| MAP, mm Hg | 79.6 (70.3–91.4) | 87±13 | 0.01 |

| APACHE II score | 24.5 (18–30) | 25±7.8 | 0.71 |

| SOFA score | 12.7±4.2 | NA | − |

| Mechanical ventilation | 84 (49.4) | 44 (100) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor use | 95 (55.9) | 39 (88.6) | <0.001 |

| Hb, g/L | 95 (80.2–117) | 99.8±34.7 | 0.72 |

| WBC, 109/L | 12.7 (8.8–18.5) | 11.7±7 | 0.03 |

| PLT, 109/L | 59 (29–115) | 146±94 | <0.001 |

| APTT, s | 48.2 (37–63.8) | 35.4 (29.4–47.6) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.55 (1.24–2.03) | 1.37 (1.09–1.74) | 0.02 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 11.7 (3.8–39.2) | 5.29 (1.43–14.1) | <0.001 |

| Tb, µmol/L | 57.6 (23.6–111.3) | 22.7 (10–76) | 0.01 |

| Db, µmol/L | 37.1 (11.2–76.6) | 13 (3.6–62) | 0.02 |

| ALP, IU/L | 84 (55.2–140.2) | 97 (70–131) | 0.18 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 258.5 (180.5–443.5) | 193 (86–343) | <0.001 |

| BUN, µmol/L | 18.6 (11.6–27.1) | 11.45 (6.45–19) | 0.002 |

| UA, µmol/L | 472.8 (354.2–499.2) | 415±243 | 0.09 |

| pH | 7.38 (7.3–7.44) | 7.32±0.1 | 0.03 |

| Serum lactate, µmol/L | 4.1 (2.35–9.6) | 4.4±4.1 | 0.18 |

| Diagnosis before CRRT | |||

| Sepsis | 45 (26.5) | NA | − |

| Post-cardiac surgery | 19 (11) | NA | − |

| Severe pancreatitis | 6 (3.5) | NA | − |

| MODS | 58 (34) | NA | − |

| Liver failure | 48 (28.2) | NA | − |

| Trauma | 9 (5.3) | NA | − |

| Exertional heat stroke | 5 (3) | NA | − |

| Others# | 27 (15.8) | NA | − |

| Indications for CRRT | |||

| AKI | 144 (84.7) | NA | − |

| Fluid overload | 44 (25.8) | NA | − |

| Severe metabolic acidosis | 58 (34) | NA | − |

| Hyperkalemia | 52 (30.5) | NA | − |

| Hyponatremia | 20 (11.7) | NA | − |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 12 (7) | NA | − |

| Hypernatremia | 11 (6.4) | NA | − |

| Hypokalemia | 7 (4) | NA | − |

| Uremia | 6 (3.5) | NA | − |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, median (IQR) or n (%). AKI, acute kidney injury; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; NA, not available; PLT, platelet; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; T, body temperature; UA, uric acid; WBC, white blood cell; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; Tb, total bilirubin; Db, direct bilirubin.

Variables with missing values were analyzed before imputations.

Other diagnoses included acute kidney injury, cancer, hypovolemic shock, electrolyte disturbance, respiratory failure, anemia, uremia, pulmonary infection, coagulopathy, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic kidney diseases, peritoneal cavity infection, and acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

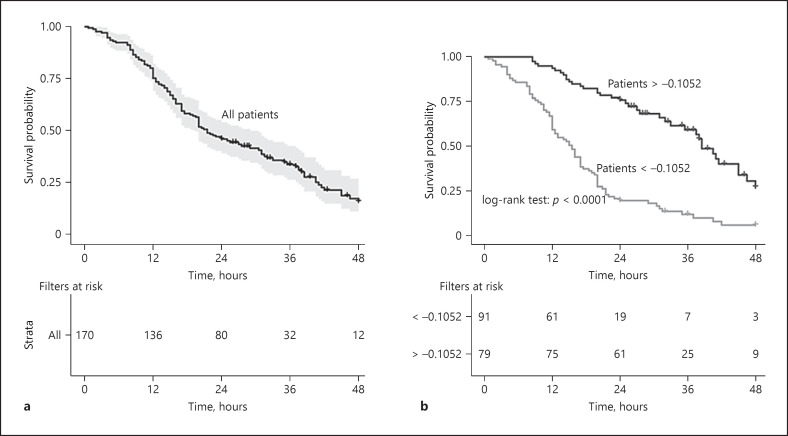

Filter Survival

During CRRT, clotting occurred in 122 (72%) filters. The overall median filter lifespan was 21.5 (12.5–30.1) hours. Sufficient filter lifespan was observed in 80 (47%) of the included circuits. Median filter lifespan of the clotted filters was 16 (10.5–25) h. The accumulated filter survival probabilities at 12-, 24-, and 48-h were 80, 47, and 7%, respectively (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for filter survival in the development cohort illustrating survival rate and numbers of survival filters at 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h. Overall filters (a). Filters stratified by the optimal cutoff value of the stepwise model (b).

Risk Factors for Filter Failure

In the univariate regression analysis, SOFA score, PLT count, hemoglobin, hematocrit (Hct), APTT, Tb, and direct bilirubin (Db) were significantly related to sufficient filter lifespan. In the multivariate analysis, red blood cell, Hct, INR, Tb, and alanine aminotransferase were removed from the model because of collinearity. Finally, the stepwise model demonstrated that temperature, mean arterial pressure (MAP), APTT, Db, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and vasopressor use were positively related to sufficient filter lifespan, and BMI, white blood cell, PLT count, D-dimer, uric acid (UA), and pH were negatively related to sufficient filter lifespan (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors in the univariate and multivariate analysis

| Predictors | Univariate logistic regression |

Multivariate logistic regression (stepwise model) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | p value | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Intercept | 0.49 | |||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 (13.5–36.5)a | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.91 | 0.82–1.01 | 0.10 |

| T, °C (3.5, −40.2) | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.72–1.57 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1.55 | 0.89–2.7 | 0.11 |

| SOFA (3–22) | 0.11 | 1.12 | 1.02–1.22 | 0.01 | ||||

| MAP, mm Hg (39–128) | −0.002 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 1.003–1.06 | 0.03 |

| WBC, ×1012 (1.67–50.2) | −0.03 | 0.96 | 0.93–1.005 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.96 | 0.92–1.01 | 0.15 |

| PLT, ×109 (4–691) | −0.0081 | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0.98–0.99 | 0.001 |

| Hb, g/L (14.6–177) | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.02 | ||||

| Hct (0.075–0.559) | −3.79 | 0.02 | 0.0005–0.94 | 0.04 | ||||

| APTT, s (17.8–180) | 0.02 | 1.02 | 1.009–1.04 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.002 |

| D-dimer, mg/L (0.31–16,000) | 0.000 | 1 | 0.99–1.0001 | 0.97 | −0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.99–1 | 0.01 |

| Tb, µmol/L (2.4–801) | 0.0027 | 1.002 | 1–1.005 | 0.04 | ||||

| Db, µmol/L (1–666) | 0.0032 | 1.003 | 1–1.006 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 1.004 | 0.99–1.008 | 0.10 |

| ALP, IU/L (19–824) | 0.0016 | 1.001 | 0.99–1.004 | 0.21 | 0.0042 | 1.004 | 1.0005–1.007 | 0.02 |

| BUN, µmol/L (3.8–69.9) | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.06 | 0.059 | 1.061 | 1.02–1.1 | 0.001 |

| UA, µmol/L (74–1,691) | −0.0011 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.0004 | 0.15 | −0.002 | 0.99 | 0.99–0.99 | 0.02 |

| pH (6.95–7.61) | −0.65 | 0.51 | 0.03–7.41 | 0.62 | −2.66 | 0.06 | 0.001–2.46 | 0.14 |

| Vasopressor (1) | 0.51 | 1.66 | 0.90–3.07 | 0.10 | 1.51 | 4.55 | 1.7–12.14 | 0.002 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CI, confidence interval; Db, direct bilirubin; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; MAP, mean arterial pressure; OR, odds ratio; PLT, platelet; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; T, temperature; Tb, total bilirubin; UA, uric acid; WBC, white blood cell; Vasopressor (1), use of vasopressor.

The ranges of each continuous predictor were presented in ().

Model Performance

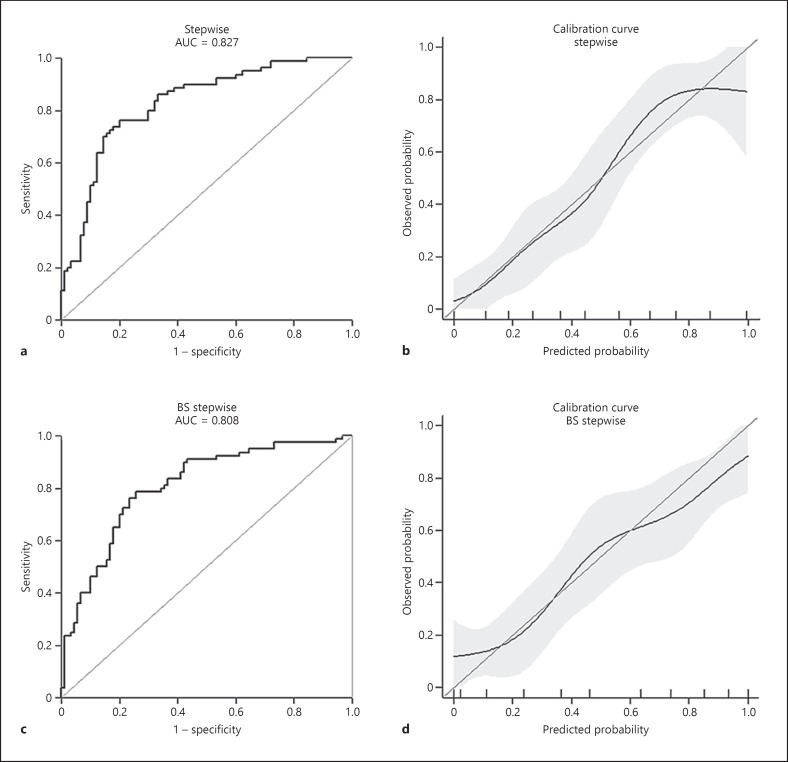

The AUC of the stepwise, mfp, and full model was 0.82 (95% CI [0.76–0.88]), 0.81 (95% CI [0.74–0.87]), and 0.83 (95% CI [0.77–0.89]), respectively. The calibration curves revealed good agreements between the predicted and observed outcomes. The AUC of the BS-stepwise and BS-full model was 0.8 (95% CI [0.74–0.87]) and 0.83 (95% CI [0.77–0.89]), respectively. The discrimination power of the models is demonstrated in Table 3. The ROC curves coupled with calibration curves of the stepwise and BS-stepwise models are illustrated in Figure 3 and those of the mfp, full, and BS-full models in online supplementary material 3, online supplementary Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Discrimination power of the prediction models

| Models | AUC | Low 95% CI | High 95% CI | Optimal cutoff value | Sen | Spe | Acc | PLR | NLR | DOR | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Stepwise | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.88 | −0.1052 | 0.76 | 0.8 | 0.78 | 3.81 | 0.29 | 12.84 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| 2 BS-stepwise | 0.8 | 0.74 | 0.87 | −0.1630 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 3.08 | 0.28 | 10.79 | 0.73 | 0.79 |

| 3 mfp | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.87 | −0.0718 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 3.05 | 0.37 | 8.14 | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| 4 Full | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.0349 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 3.97 | 0.3 | 12.88 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| 5 BS-full | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.89 | −0.7773 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 2.89 | 0.22 | 12.68 | 0.72 | 0.83 |

AUC, area under the curve; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BS, bootstrapping; CI, confidence interval; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; mfp, Multiple Fractional Polynomial; NPV, negative predictive value; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity.

Backward stepwise variables selection based on AIC.

Stepwise model Bs 1,000 times.

Final model was generated based on mfp.

Full model.

Full model Bs 1,000 times

Fig. 3.

The predictive performance of the stepwise model and the internal validation model. ROC curve of the stepwise model (a); calibration curve of the stepwise model (b); ROC curve of the BS-stepwise model (c); calibration curve of the BS-stepwise model (d). AUC, area under the curve; BS, bootstrapping; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The AUC of the stepwise model was significantly increased, compared with routinely tested coagulation parameters including APTT (p < 0.001), INR (p < 0.001), and PLT (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the AUC of the stepwise model was superior to that of the model including all of these 3 parameters as well (0.82 [0.76–0.88] vs. 0.7 [0.62–0.78], p = 0.0016) (online suppl. material 4, online suppl. Fig. 2).

Final Model Selection

The full model and the mfp model did not show better accuracy than the stepwise model. Furthermore, the complicated formula of the mfp model compromised the convenience for application. Therefore, the stepwise model was the most parsimonious model under the premise of guaranteeing discrimination performance and was selected as the final model.

Accordingly, the probability of sufficient filter lifespan could be calculated using the following regression formula: P (%) = exp (Z)/1 + exp (Z), where Z = 0.49896 − (0.08552 × BMI) + (0.44107 × T) + (0.03373 × MAP) − (0.03389 × white blood cell) + (1.51579 × [vasopressor = 1]) − (0.01132 × PLT) + (0.00422 × ALP) − (2.66910 × pH) − (0.00214 × UA) + (0.05992 × BUN) + (0.00400 × Db) − (0.00014 × D-dimer) + (0.02818 × APTT). In order to facilitate the application in clinical practice, we developed a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (online suppl. material 5: the Excel calculator) and a nomogram (online suppl. material 6, online suppl. Fig. 3), based on this formula. An optimal cutoff value of Z was identified as −0.1052. The final model could discriminate 61 out of the 80 patients with sufficient filter lifespan and, the PPV and the NPV were 0.77 and 0.79, respectively. Furthermore, the median filter lifespan was significantly longer in patients with Z > −0.1052 (26 [24–38.25] h vs. 15.5 [9.75–21.5] hours, p < 0.001, Figure 2b).

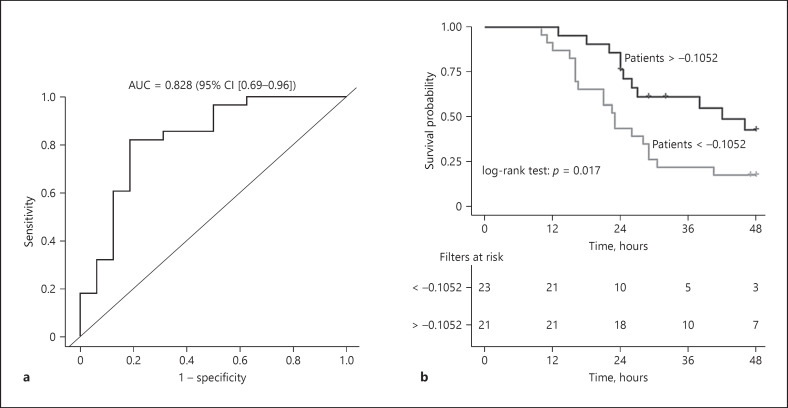

External Validation

After the screening, 44 eligible cases were included in the external validation cohort (online suppl. material 7, online suppl. Fig. 4). The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, body temperature, male proportion, BMI, MAP, and APACHE II score between development cohort and validation cohort. The AUC of the ROC of the external validation model was 0.82 (95% CI [0.69–0.96], Figure 4a). According to the optimal cutoff value of the development model, 18 out of the 28 patients with sufficient filter lifespan were discriminated and the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 0.64, 0.81, 0.85, and 0.56, respectively. The median filter lifespan was significantly longer in patients above the cutoff value (32 [24–51] h vs. 23 [16–29] h, p = 0.03, Figure 4b). The overall median filter lifespan in the validation cohort was 26.5 (21–46.2) h.

Fig. 4.

The ROC curve of the external validation model and Kaplan-Meier curve for filter survival in the validation cohort. ROC curve and AUC of the external validation model (a); Kaplan-Meier curve for filter survival in the external validation cohort (b), which illustrated the filters survival rate and numbers of survival filters at 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h in patients stratified by the optimal cutoff value of the development model. AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

We have developed and externally validated a clinical prediction model that can be used to predict sufficient filter lifespan in patients who underwent anticoagulation-free CRRT. Lower PLT count, UA, and D-dimer as well as higher MAP, APTT, ALP, and BUN, and the use of vasopressor were independently related to longer filter lifespan during anticoagulation-free CRRT. Our prediction model could facilitate the choice of an optimal anticoagulation strategy for an individual patient.

Fealy et al. [26] reported in a randomized controlled trial that longer APTT and decreased PLT count were independently associated with a reduced likelihood of circuit clotting. The similar association of APTT [32] and PLT count [33, 34] with CRRT filter lifespan were reported in observational studies as well. Zhang et al. [35] reported that lower pH was significantly associated with longer filter lifespan in a multivariable Cox regression model. These evidences demonstrated the reliability of the predictors in our present model. However, the mechanism of filter failure is highly sophisticated [36, 37, 38, 39, 40] and could not be solely interpreted or predicted by classical markers of coagulation, including PT, APTT, and PLT count [41]. A recent meta-analysis [27] divided nonanticoagulant determinants of filter lifespan into vascular access factors, circuit factors, and patient factors. Therefore, a clinical prediction model, which was commonly based on more comprehensive indicators, could most likely provide more accurate prediction for filter failure and sufficient lifespan.

To our knowledge, studies developing prediction models for filter lifespan of CRRT are scarce. A prognostic model reported by Fu et al. [20] suggested that insufficient blood flow, without anticoagulation, and values of Hct, lactate, and APTT could be used to predict the likelihood of extracorporeal circuit clotting within 24 h in patients underwent CRRT with all kinds of anticoagulation models. The AUC of this model was 0.79 (95% CI [0.7–0.87]). Despite both of the AUCs of this model and ours were >0.75, a threshold deemed as useful discrimination [30], our model has several advantages. First, we included only CRRT patients without the use of any anticoagulation, which could offer important information for the choice of anticoagulation strategies, mainly use or no use of anticoagulation. The study by Fu et al. [20] included patients with and without anticoagulation in their model. The use of anticoagulation definitely played a major role in the prolonged filter lifespan and the filter lifespan in patients accepted anticoagulation were mainly attributed to the effective anticoagulation, including the anticoagulant types and the sufficient dose of anticoagulant. Therefore, the model by Fu et al. [20] could not offer key clues for the use or no use of anticoagulation for clinicians, especially for patients with relative contraindications to anticoagulation. Second, all the included predictors in our model were readily available prior to CRRT initiation, which could be helpful and useful for clinical decision-making. Third, in addition to the regression formula, the nomogram and Excel calculator could provide more convenient and accurate prediction. At last, our model has been validated in an external validation cohort, which suggested very good reliability.

Several previous studies also suggested the use of coagulation parameters and bleeding markers to determine the use of anticoagulation-free protocol. However, in the study by Morabito. et al. [42], 45% of the patients who initially received anticoagulation-free protocol switched to heparin anticoagulation because the filter lifespan was <24 h. In another study by Morabito. et al. [19], 33 patients switched to RCA-CRRT because of early circuit clotting (<24 h) without anticoagulation, and only 40% of the circuits reached a lifespan of more than 24 h before switch. In our development cohort and validation cohort, 76 and 64% of the patients with sufficient filter lifespan were accurately predicted, respectively. These evidences indicated that the use of a prediction model instead of an assessment based only on coagulation parameters could significantly improve the discrimination ability to identify eligible patients for anticoagulant-free CRRT.

Our model can facilitate the assessment of filter failure risk and the selection of appropriate anticoagulation for CRRT in patients with relative contraindications to anticoagulation. The patient with expected sufficient filter lifespan could initially undergo anticoagulation-free CRRT. For those patients with expected insufficient filter lifespan, a less risky anticoagulation strategy could be considered. Future studies with prospective, randomized, and multicenter design are warranted to validate our findings.

There are some limitations to our present study. First, there were potential confounding factors and biases due to the retrospective nature of our present study. We had strictly predefined the inclusion and exclusion criteria and enrolled consecutive real-life patients over a 6-year period in an effort to reduce the selection bias and confounding factors. Second, the application of the model might be complex as the final model includes 13 variables. However, most of these predictors were clinically relevant and easily available in routine practice. Furthermore, an Excel calculator was generated and would facilitate the clinical application of our model. Third, the definition of “filter failure” did not account for the bubble trap clotting which is independent to membrane clotting but also frequently causes failure [43]. However, most of the included filters were judged as failure by transmembrane pressure >300 mm Hg or visible clots in the other parts of the circuit with less possibility of bubble trap clotting. Fourth, 2 types of filter with different membrane sizes were included in the development cohort, which could partially contribute to the heterogeneity of filter lifespan [44]. The heterogeneity of filter type was caused by the use of different CRRT machines. In order to identify a model for the prediction of filter function in all kinds of filter type, we did not include the filter type and membrane size in the model. Filters with uniform membrane size are warranted in the future studies. Additionally, only Chinese patients were included in both the development and validation cohort. Further adjustment might be necessary when employing our model in other ethnic population.

Conclusions

The use of a prediction model instead of an assessment based only on coagulation parameters could facilitate the identification of the patients with filter lifespan of ≥24 h when they accepted anticoagulation-free CRRT. Our model most likely could facilitate the choice of an optimal anticoagulation strategy for an individual patient.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval and informed consent were waived by the local Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital in view of the retrospective nature of the study. This study was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070699) and Discipline Promotion Project of Xijing Hospital (XJZT18ML16).

Author Contributions

Wei Zhang, Ming Bai, and Ling Zhang contributed equally to this work. Wei Zhang, Ming Bai, and Shiren Sun conceived the study, participated in the design, collected the data, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. Yan Yu, Yangping Li, and Lijuan Zhao collected data of the development cohort and helped to draft the manuscript. Yuan Yue and Yajuan Li helped to collect the data of the development cohort. Ming Bai performed statistical analyses and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Min Zhang collected the data of the external validation cohort. Ling Zhang assisted in interpreting the findings and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. Shiren Sun, Ping Fu, and Xiangmei Chen helped to revise the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at (DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-73156/v1). This work was supported by the Nephrology Department of Xijing Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University, and the Department of Nephrology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Wei Zhang, Ming Bai and Ling Zhang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Aug;41((8)):1411–23. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joannidis M, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Clinical review: patency of the circuit in continuous renal replacement therapy. Crit Care. 2007;11((4)):218. doi: 10.1186/cc5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandenburger T, Dimski T, Slowinski T, Kindgen-Milles D. Renal replacement therapy and anticoagulation. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Sep;31((3)):387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi M, Opal SM. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10((4)):222. doi: 10.1186/cc4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward DM, Mehta RL. Extracorporeal management of acute renal failure patients at high risk of bleeding. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993;41:S237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Wetering J, Westendorp RG, van der Hoeven JG, Stolk B, Feuth JD, Chang PC. Heparin use in continuous renal replacement procedures: the struggle between filter coagulation and patient hemorrhage. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996 Jan;7((1)):145–50. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V71145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai M, Zhou M, He L, Ma F, Li Y, Yu Y, et al. Citrate versus heparin anticoagulation for continuous renal replacement therapy: an updated meta-analysis of RCTs. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Dec;41((12)):2098–110. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuhrmann V, Kneidinger N, Herkner H, Heinz G, Nikfardjam M, Bojic A, et al. Impact of hypoxic hepatitis on mortality in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2011 Aug;37((8)):1302–10. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien AJ, Welch CA, Singer M, Harrison DA. Prevalence and outcome of cirrhosis patients admitted to UK intensive care: a comparison against dialysis-dependent chronic renal failure patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012 Jun;38((6)):991–1000. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosravani H, Shahpori R, Stelfox HT, Kirkpatrick AW, Laupland KB. Occurrence and adverse effect on outcome of hyperlactatemia in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2009;13((3)):R90. doi: 10.1186/cc7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khadzhynov D, Dahlinger A, Schelter C, Peters H, Kindgen-Milles D, Budde K, et al. Hyperlactatemia, lactate kinetics and prediction of citrate accumulation in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy with regional citrate anticoagulation. Crit Care Med. 2017 Sep;45((9)):e941–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy: a worldwide practice survey. The beginning and ending supportive therapy for the kidney (B.E.S.T. kidney) investigators. Intensive Care Med. 2007 Sep;33((9)):1563–70. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palevsky PM, Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, et al. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 3;359((1)):7–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellomo R, Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, et al. Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 22;361((17)):1627–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleger GR, Fässler E. Can circuit lifetime be a quality indicator in continuous renal replacement therapy in the critically ill? Int J Artif Organs. 2010 Mar;33((3)):139–46. doi: 10.1177/039139881003300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chua HR, Baldwin I, Bailey M, Subramaniam A, Bellomo R. Circuit lifespan during continuous renal replacement therapy for combined liver and kidney failure. J Crit Care. 2012 Dec;27((6)):744–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schilder L, Nurmohamed SA, ter Wee PM, Paauw NJ, Girbes AR, Beishuizen A, et al. Coagulation, fibrinolysis and inhibitors in failing filters during continuous venovenous hemofiltration in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: effect of anticoagulation modalities. Blood Purif. 2015;39((4)):297–305. doi: 10.1159/000380904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morabito S, Pistolesi V, Tritapepe L, Zeppilli L, Polistena F, Strampelli E, et al. Regional citrate anticoagulation in cardiac surgery patients at high risk of bleeding: a continuous veno-venous hemofiltration protocol with a low concentration citrate solution. Crit Care. 2012 Jun 27;16((3)):R111. doi: 10.1186/cc11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu X, Liang X, Song L, Huang H, Wang J, Chen Y, et al. Building and validation of a prognostic model for predicting extracorporeal circuit clotting in patients with continuous renal replacement therapy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014 Apr;46((4)):801–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0682-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BJOG. 2015 Jan 7;122:434. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan HK, Baldwin I, Bellomo R. Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration without anticoagulation in high-risk patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000 Nov;26((11)):1652–7. doi: 10.1007/s001340000691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slowinski T, Morgera S, Joannidis M, Henneberg T, Stocker R, Helset E, et al. Safety and efficacy of regional citrate anticoagulation in continuous venovenous hemodialysis in the presence of liver failure: the liver citrate anticoagulation threshold (L-CAT) observational study. Crit Care. 2015 Sep 29;19:349. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315((8)):801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattas DJ, Rajbhandari D, Bradford C, Buhr H, Lo S, Bellomo R. A randomized controlled trial of regional citrate versus regional heparin anticoagulation for continuous renal replacement therapy in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2015 Aug;43((8)):1622–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fealy N, Aitken L, du Toit E, Lo S, Baldwin I. Faster blood flow rate does not improve circuit life in continuous renal replacement therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2017 Oct;45((10)):e1018–25. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brain M, Winson E, Roodenburg O, McNeil J. Non anti-coagulant factors associated with filter life in continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017 Feb 20;18((1)):69. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0445-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vrieze SI. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) Psychol Methods. 2012 Jun;17((2)):228–43. doi: 10.1037/a0027127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Kattan MW. Drawing nomograms with R: applications to categorical outcome and survival data. Ann Transl Med. 2017 May;5((10)):211. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, Hanna S, Iorio A, Devereaux PJ, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2017 Oct 10;318((14)):1377–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988 Sep;44((3)):837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacEwen C, Watkinson P, Winearls C. Circuit life versus bleeding risk: the impact of achieved activated partial thromboplastin time versus achieved filtration fraction. Ther Apher Dial. 2015 Jun;19((3)):259–66. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunn WJ, Sriram S. Filter lifespan in critically ill adults receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: the effect of patient and treatment-related variables. Crit Care Resusc. 2014 Sep;16((3)):225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, Tanaka A, Zhu G, Baldwin I, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R. Patterns and mechanisms of artificial kidney failure during continuous renal replacement therapy. Blood Purif. 2016;41((4)):254–63. doi: 10.1159/000441968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Ni H, Lu B. Variables associated with circuit life span in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy: a prospective observational study. ASAIO J. 2012 Jan;58((1)):46–50. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31823fdf20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davenport A. The coagulation system in the critically ill patient with acute renal failure and the effect of an extracorporeal circuit. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997 Nov;30((5 Suppl 4)):S20–7. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salmon J, Cardigan R, Mackie I, Cohen SL, Machin S, Singer M. Continuous venovenous haemofiltration using polyacrylonitrile filters does not activate contact system and intrinsic coagulation pathways. Intensive Care Med. 1997 Jan;23((1)):38–43. doi: 10.1007/s001340050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardigan R, McGloin H, Mackie I, Machin S, Singer M. Endothelial dysfunction in critically ill patients: the effect of haemofiltration. Intensive Care Med. 1998 Dec;24((12)):1264–71. doi: 10.1007/s001340050760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cardigan RA, McGloin H, Mackie IJ, Machin SJ, Singer M. Activation of the tissue factor pathway occurs during continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Kidney Int. 1999 Apr;55((4)):1568–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouman CS, de Pont AC, Meijers JC, Bakhtiari K, Roem D, Zeerleder S, et al. The effects of continuous venovenous hemofiltration on coagulation activation. Crit Care. 2006;10((5)):R150. doi: 10.1186/cc5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Hemostasis and thrombosis in continuous renal replacement treatment. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015 Feb;41((1)):91–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morabito S, Guzzo I, Solazzo A, Muzi L, Luciani R, Pierucci A. Continuous renal replacement therapies: anticoagulation in the critically ill at high risk of bleeding. J Nephrol. 2003 Jul;16((4)):566–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldwin I, Fealy N, Carty P, Boyle M, Kim I, Bellomo R. Bubble chamber clotting during continuous renal replacement therapy: vertical versus horizontal blood flow entry. Blood Purif. 2012;34((3–4)):213–8. doi: 10.1159/000342596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baldwin I. Factors affecting circuit patency and filter “life”. Contrib Nephrol. 2007;156:178–84. doi: 10.1159/000102081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.