Abstract

Introduction

The phase 3 fliGHt Trial evaluated the safety and tolerability of once-weekly lonapegsomatropin, a long-acting prodrug, in children with growth hormone deficiency (GHD) who switched from daily somatropin therapy to lonapegsomatropin.

Methods

This multicenter, open-label, 26-week phase 3 trial took place at 28 sites across 4 countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the USA). The trial enrolled 146 children with GHD, 143 of which were previously treated with daily somatropin. All subjects received once-weekly lonapegsomatropin 0.24 mg human growth hormone/kg/week. The primary outcome measure was safety and tolerability of lonapegsomatropin over 26 weeks. Secondary outcome measures assessed annualized height velocity (AHV), height standard deviation score (SDS), and IGF-1 SDS at 26 weeks.

Results

Subjects had a mean prior daily somatropin dose of 0.29 mg/kg/week. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) reported were similar to the published AE profile of daily somatropin therapies. After switching to lonapegsomatropin, the least-squares mean (LSM) AHV was 8.7 cm/year (95% CI: 8.2, 9.2) at Week 26 and LSM height SDS changed from baseline to Week 26 of +0.25 (95% CI: 0.21, 0.29). Among switch subjects, the LSM for average IGF-1 SDS was sustained at Weeks 13 and 26, representing an approximate 0.7 increase from baseline (prior to switching from daily somatropin therapy). Patient-reported outcomes indicated a preference for weekly lonapegsomatropin among both children and their parents.

Conclusions

Lonapegsomatropin treatment outcomes were as expected across a range of ages and treatment experiences. Switching to lonapegsomatropin resulted in a similar AE profile to daily somatropin therapy.

Keywords: Growth hormone, Growth hormone deficiency, Growth hormone replacement therapy, Long-acting growth hormone, Lonapegsomatropin, TransCon human growth hormone

Introduction

Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is characterized by impaired production or secretion of growth hormone (GH) from the anterior pituitary gland. For decades, the standard of care for children with GHD has been daily injections of somatropin (recombinant human GH [hGH]). While replacement therapy should optimally allow children to achieve normal adult height, many children with GHD treated with daily administered somatropin do not achieve their predicted adult height, which is partly due to suboptimal adherence to daily injections [1, 2]. Observational studies also show that patients treated with daily hGH do not reach the height of the general population. Height standard deviation scores (SDSs) in a French registry of 2,165 patients who had long-term treatment with hGH were estimated at −1.6 SDS [3]. Similarly, the KIGS database and the NordiNet IOS database showed near-adult height SDS of −1.4 and −1.0, respectively [4, 5].

Both children and their parents/caregivers find daily injections of somatropin burdensome, which may contribute to poor adherence to a therapy that is typically required for years or even a lifetime [6]. Prevalence estimates of nonadherence vary from 5% to 82%, depending on the methods and definitions used [7, 8, 9, 10]. Specifically, independent unsupervised teenagers report nonadherence rates as high as 66%–77% [11]. Poor adherence to GH therapy has been found to be associated with reduced growth [8, 12]. Consequently, the Growth Hormone Research Society has recognized that by decreasing injection frequency, long-acting GH (LAGH) formulations may improve adherence to potentially optimize clinical efficacy [13].

Lonapegsomatropin (TransCon hGH/SKYTROFA^; Ascendis Pharma A/S) is a once-weekly prodrug in development for children and adults with GHD that consists of somatropin transiently conjugated to an inert carrier via a TransConTM linker. The carrier has a shielding effect that minimizes renal excretion and GH receptor-mediated clearance of lonapegsomatropin. Under physiologic conditions, the linker undergoes autocleavage and releases fully active somatropin in a consistent and predictable manner, supporting weekly dosing. Lonapegsomatropin is designed to release somatropin with the identical 191 amino acid sequence and size (22 kDa) as both endogenous GH and daily somatropin therapy; thus, the released somatropin is expected to maintain the same mode of action, distribution, and intracellular signaling [14]. Lonapegsomatropin was recently approved by the US FDA for the treatment of pediatric GHD in children 1 year and older who weigh 11.5 kg or greater, and have growth failure due to lack of secretion of endogenous GH [15].

In the pivotal phase 3 heiGHt Trial, lonapegsomatropin demonstrated superior annualized height velocity (AHV) and a similar safety profile compared to daily somatropin at equivalent weekly doses in treatment-naïve prepubertal children with GHD [16]. Switching to weekly lonapegsomatropin may be an attractive option for patients currently receiving daily somatropin therapy, given the superior AHV outcomes observed in heiGHt and the potential to alleviate treatment burden associated with daily injections. Thus, the fliGHt Trial was designed to assess the safety and tolerability of weekly lonapegsomatropin in children with GHD who previously received daily somatropin therapy, and in patients of a broader age range and Tanner staging than evaluated in the heiGHt trial.

Materials and Methods

Study Oversight

The fliGHt Trial was a multicenter, phase 3, open-label, single-arm, 26-week trial of weekly lonapegsomatropin in children with GHD (NCT03305016). The protocol was approved by a local institutional review board, independent Ethics Committee, or Human Research Ethics Committee prior to trial initiation, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All parents/legal guardians provided informed consent prior to patient participation in any patient-specific procedures. The trial was conducted at 24 sites in 4 countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the USA) between November 2017 and March 2019.

Study Population

This study was open for enrollment to male and female patients from ages 6 months to 17 years old (Tanner stage <5) who were diagnosed with GHD. Reflecting clinical practice for identifying children with GHD who are appropriate for GH treatment in the regions under study, patients had to have at least 1 of the following prior to initiating daily somatropin therapy: 2 GH stimulation tests with peak GH levels ≤10 ng/mL, impaired height (≤ −2 height SDS and/or ≥1.5 height SDS below midparental height), IGF-1 ≤ −1 SDS, delayed bone age (≥6 months relative to chronologic age), diagnosis of an additional pituitary hormone deficiency, and/or congenital hypopituitarism.

Patients ages 3–17 were previously treated with daily somatropin ≥0.20 mg hGH/kg/week (or at doses that accommodated country-specific dosing requirements) for 13–130 weeks. Patients between 6 months and 3 years old were treated for ≤130 weeks but with no minimum time on treatment, given that patients in this age bracket may have not been previously treated or may have been treated for only a short time. Patients 6 months to 3 years old may also have been treatment-naïve; the treatment-naïve patients enrolled in the study (n = 3) are included only in safety and tolerability analyses in this manuscript. Patients were excluded if they weighed <5.5 or >80 kg, had a history of malignant disease, had any clinically significant abnormality or concomitant medication that may have an effect on growth (hormone replacement for hypopituitarism was allowed), had poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, had known neutralizing antibodies against somatropin, required high-dose inhaled glucocorticoid therapy, had closed epiphyses, had prior exposure to investigational GH or participated in another trial within 30 days.

Treatment

All subjects initiated subcutaneous lonapegsomatropin 0.24 mg hGH/kg/week administered via vial and syringe regardless of previous daily somatropin therapy. The study drug was administered based on the patient's weight measured during Week 1 and could be adjusted based on weight during Week 13. Doses could be adjusted at the discretion of the investigator due to symptoms or laboratory abnormalities. Rotation of injection sites (thigh, abdomen, buttock) was recommended.

Study Objectives and Assessments

The primary objective was to assess the safety and tolerability of weekly lonapegsomatropin in children with GHD. Secondary objectives included assessment of AHV, height SDS, IGF-1 SDS, and treatment preference and satisfaction. Safety endpoints included adverse events (AEs), local tolerability, laboratory parameters, vital signs, and immunogenicity assessments.

Patients attended a screening visit to determine eligibility, obtain informed consent and medical history, perform a physical examination, and draw laboratory tests (including hematology, chemistry, lipids, glycemic control, thyroid function, and morning cortisol). Subjects attended visits during Weeks 1, 13, and 26 for height and weight measurements, laboratory testing, and AE monitoring. Local tolerability assessment was performed by site staff during Week 1 and by the subject/parent via the patient diary at all other time points. Local injection site reactions were reported as AEs if the pain, intensity, or duration impacted a subject's ability to perform daily activities or required medical therapy.

Because IGF-1 levels following lonapegsomatropin administration follow a predictable weekly pharmacokinetic curve, serum IGF-1 was collected on post-dose day 5 (±1), which approximates the weekly “average” IGF-1 level, the level that best aligns with the existing paradigm of IGF-1 levels for daily injections of somatropin [17, 18, 19]. Quantification of serum somatropin was conducted by Celerion (Lincoln, NE, USA) using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Quantification of serum IGF-1 was performed by Laboratorium für Klinische Forschung GmbH, Schwentinental, Germany using a validated commercially available chemiluminescence immunoassay (Immunodiagnostics Systems iSYS, Boldon, UK). IGF-1 SDS was calculated using age- and sex-specific reference intervals [20]. Anti-hGH binding antibodies were detected by a validated assay (BioAgilytix, Durham, NC, USA); antibody-positive samples were assessed for neutralizing activity using a validated cell-based proliferation assay (Eurofins, Abingdon, UK).

Patient-Reported Outcomes

In this trial, treatment preference and treatment burden as reported by the patient (child) and their parent (or caregiver/guardian) were evaluated. For the treatment preference questionnaires, factors that may influence preference were derived from clinical input and published research. Subjects ≥9 years old at the time of enrollment and their parents completed the Preference Questionnaire–Parent and the Preference Questionnaire–Child, respectively, at Weeks 6 and 13.

To assess treatment burden, the Child Sheehan Disability Score (CSDS) was adapted to injectable GH treatment, with permission from the developer. The CSDS for child (CSDS-C) and parent (CSDS-P) are self-rated instruments that assess the impact of treatments on children and their parents across work/school, social, and family life domains [21]. The summary score for each questionnaire is the sum of the scores for each individual question with a possible total of 30 for the CSDS-C and 50 for the CSDS-P, with lower scores indicating less impact of the treatment on daily life. Subjects ≥9 years old at the time of enrollment and all parents completed their corresponding CSDS at Weeks 1 (predose), 6, 13, and 26. Prior to use in the fliGHt Trial, the Preference Questionnaire and CSDS were assessed for understanding among children with GHD and their parents in a cognitive debriefing study.

Statistical Analysis

Safety analyses were based on the full analysis set (146 subjects), which included all subjects who received at least 1 dose of study drug during the trial and who had follow-up data. Efficacy analyses were based on the 143 subjects who were previously treated with daily somatropin. There was no imputation for missing data. Baseline was defined as the most recent available assessment before study drug administration. Overall treatment adherence for each subject was defined as the number of administered to scheduled doses as assessed by drug accountability records and patient diaries.

AHV, change in height SDS from baseline (Δ height SDS), and average IGF-1 SDS were summarized using an analysis of covariance model that included sex as a factor and baseline age, peak stimulated GH levels (log-transformed), height SDS minus average parental height SDS (for AHV and Δ height SDS only), IGF-1 SDS at trial enrollment (for average IGF-1 SDS only), and prior somatropin dose level (log-transformed) and duration (log-transformed) as covariates. Prespecified subgroup analyses of the full analysis set are presented as arithmetic means and standard deviation (SD). Ad hoc analyses for AHV and Δ height SDS were also analyzed by the duration of prior daily somatropin treatment.

Results

Of 162 patients screened, 143 treatment-experienced patients were enrolled into the trial and received at least 1 dose of study drug. All but 2 subjects (98.6%) completed the trial; both patients withdrew consent. Demographic data are described in Table 1. Eleven patients had documented deficiencies of other pituitary axes, including 1 patient who had thyroid, gonadal, and adrenal axes deficiencies, 5 patients with deficiencies of 2 axes other than the GH/IGF-1 axis, and 5 patients with a single additional pituitary deficiency; all pituitary deficiencies were appropriately replaced for at least 13 weeks prior and throughout the trial. The mean (SD) prior daily somatropin treatment duration was 1.1 (0.7) years (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics at trial enrollment

| Variable | Total enrolled (N = 146) | Previously treated (n = 143) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 110 (75.3) | 109 (76.2) |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 10.6 (1.2–17.4) | 10.8 (2.0–17.4) |

| Age category, n (%) | ||

| <3 years | 4 (2.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| ≥3 and <6 years | 20 (13.7) | 20 (14.0) |

| ≥6 to <11 years (girls) or ≥6 to <12 years (boys) | 55 (37.7) | 55 (38.5) |

| ≥11 years (girls) or ≥12 years (boys) | 67 (45.9) | 67 (46.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 124 (84.9) | 121 (84.6) |

| Asian | 6 (4.1) | 6 (4.2) |

| Black or African American | 3 (2.1) | 3 (2.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) |

| Multiple | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 9 (6.2) | 9 (6.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 10 (6.8) | 10 (7.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 124 (84.9) | 121 (84.6) |

| Not reported | 8 (5.5) | 8 (5.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.7) | 4 (2.8) |

| Region of enrollment, n (%) | ||

| North America | 139 (95.2) | 136 (95.1) |

| Oceania | 7 (4.8) | 7 (4.9) |

| Height SDS, mean (SD) | −1.42 (0.84) | −1.40 (0.83) |

| Δ average parental height SDS,*, † mean (SD) | −1.14 (1.02) | −1.11 (1.00) |

| BMI SDS, mean (SD) | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.24 (1.06) |

| Tanner stage, n (%) | ||

| I | 95 (65.1) | 92 (64.3) |

| II | 14 (9.6) | 14 (9.8) |

| III | 30 (20.5) | 30 (21.0) |

| IV | 7 (4.8) | 7 (4.9) |

| Deficiencies of other pituitary axes, n (%) | ||

| Thyroid axis deficiency | 8 (5.5) | 7 (4.9) |

| Gonadal axis deficiency | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Adrenal axis deficiency | 8 (5.5) | 7 (4.9) |

| Antidiuretic hormone insufficiency | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| IGF-1 SDS, mean (SD) | 0.85 (1.29) | 0.91 (1.25) |

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; SDS, standard deviation score.

Δ average parental height SDS is the difference between the patient's height SDS and the average parental height SDS where average parental height SDS = (height SDSmother + height SDSfather)/2.

n = 141.

Table 2.

Daily somatropin treatment history

| Variable | Total (n = 143) |

|---|---|

| Daily somatropin dose at trial enrollment, mg hGH/kg/week | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.29 (0.05) |

| Min, max | 0.13, 0.49 |

| Daily somatropin dose duration since treatment initiation, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.14 (0.73) |

| Min, max | 0.25, 3.97 |

| Daily somatropin product type, n (%) | |

| Pen | 129 (90.2) |

| Reusable with cartridges requiring reconstitution, multi-usea | 27 (18.9) |

| Reusable with liquid-filled cartridges, multi-useb | 23 (16.1) |

| Disposable, requiring reconstitution, multi-usec | 1 (0.7) |

| Disposable, requiring reconstitution, single used | 3 (2.1) |

| Disposable, liquid-filled, multi-usee | 75 (52.4) |

| Vial | 12 (8.4) |

| Other | 2 (1.4) |

hGH, human growth hormone (somatropin); SD, standard deviation.

E.g., HumatroPen, Genotropin Pen, Saizen One Click.

E.g., Omnitrope Pen.

E.g., Genotropin GoQuick.

E.g., Genotropin MiniQuick.

E.g., Norditropin FlexPro, Nutropin AQ Nupin.

When available, disease characteristics at the time of GHD diagnosis were also collected from medical records and are reported here for the 143 switch subjects: the mean (SD) most recent height SDS before diagnosis was −2.1 (0.9) (n = 135), the mean (SD) IGF-1 SDS at diagnosis was −1.27 (0.98) (n = 60), the mean (SD) delay in bone age was 1.2 (1.1) years (n = 120), and the mean (SD) peak stimulated GH concentration was 5.9 (2.6) ng/mL (n = 141). The mean (SD) age at the time of GHD diagnosis was 9.4 (3.4) years.

Safety and Tolerability

Treatment adherence during the trial was high, with a mean (SD) adherence rate of 98.4% (4.0) in the full trial population. Just over half of the subjects (57%) (83/146) experienced at least 1 AE, with only 4% experiencing an AE that was assessed by the investigator as related to study drug (Table 3). Most patients experienced AEs that were mild (45%) or moderate (12%) in severity. The most common AEs were pyrexia (12%), nasopharyngitis (10%), upper respiratory tract infection (10%), headache (8%), and oropharyngeal pain (5%) (Table 3). No patients discontinued study drug due to an AE.

Table 3.

Summary of AEs

| Variable | Total (N = 146), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Any AE* | 83 (56.8) |

| Pyrexia | 17 (11.6) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 14 (9.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 14 (9.6) |

| Headache | 12 (8.2) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 8 (5.5) |

| AE related to study drug | 6 (4.1) |

| AE that led to discontinuation of study drug | 0 |

| SAE | 1 (0.7) |

| SAE related to study drug | 0 |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

Specific AEs listed were reported by >5% of patients.

Two serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in 1 subject, a 13-year-old male with a congenital structural heart abnormality that, despite surgical repair at 1 month of age, resulted in persistent sequelae, including chronic left bundle branch block prior to trial enrollment. On Day 13, the subject experienced an SAE of atrioventricular block for which a pacemaker was placed. Later during the trial, after being hit near the pacemaker site at school, the patient was evaluated in the hospital and a second SAE (chest pain) was reported for this patient. Both events were assessed by the investigator as unrelated to study drug.

Over the course of the trial, weekly injections of lonapegsomatropin were well-tolerated. Based on detailed observations made by study staff during Visit 1, the majority of patients had no redness (96.6%), no bruising (97.9%), no swelling (99.3%), and no pain (99.3%) at 2 h following injection. By 15 min after the injection, most patients (95.1%) reported no pain at the injection site. Over the course of the trial, local tolerability assessments recorded by patients or their parents/caregivers showed no redness, no bruising, no swelling, and no itching; pain scores were ≤4 (on the Wong-Baker FACES^ pain rating scale of 0 [no hurt] to 10 [hurts worst]) in the majority of patients. At the time of injection at Week 1, 85.8% of subjects reported a pain rating of 4 or below, and at 15 min postinjection 98.6% reported 4 or below. The percentage of patients reporting a low pain score increased throughout the trial, with a pain scale rating of 4 or below at injection reported in 89.3% and 97.3% of subjects at Week 13 and 26, respectively.

There were no remarkable changes in laboratory test results, vital sign measures, or fundoscopy findings. Mean levels of hemoglobin A1c (5.2% at baseline, Weeks 13 and 26), morning cortisol (7.42, 8.18, and 7.28 μg/dL at baseline, Weeks 13, and 26, respectively), and free thyroxine (1.21, 1.27, and 1.25 ng/dL at baseline, Week 13, and Week 26, respectively) were stable and within normal range throughout the trial, including those on supplementation treatment. Mean (SD) body mass index SDS remained within the normal range, from −0.25 (1.1) at Week 1 to 0.02 (1.0) and 0.13 (1.0) at Weeks 13 and 26, respectively. Low titer antidrug binding antibodies were detected against hGH in 3% of treated patients. Detected antibodies did not appear to affect safety or efficacy. No neutralizing antibodies were detected and no anti-PEG antibodies were detected throughout the trial.

Growth and Pharmacodynamic Outcomes

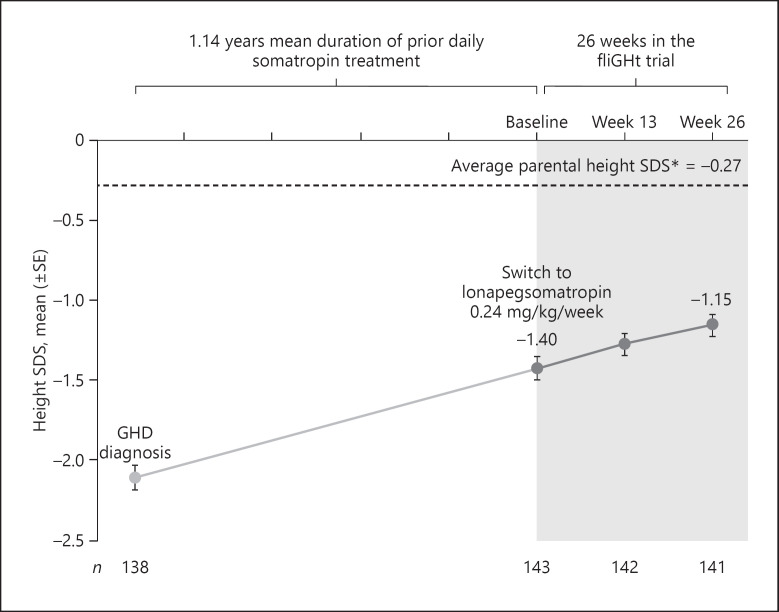

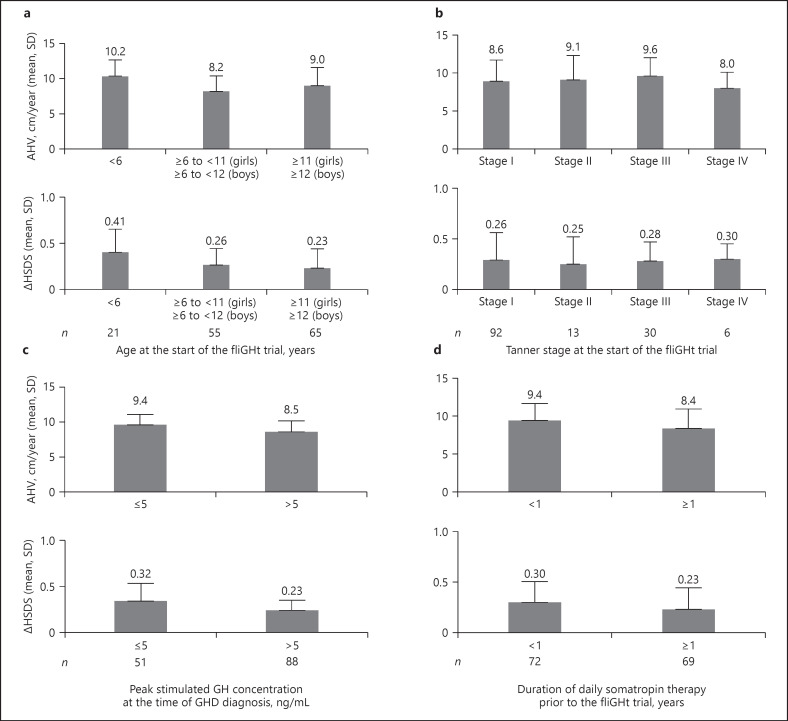

Across the broad range of treatment-experienced patients (n = 141), the LS mean (SE) AHV was 8.72 (0.24) cm/year at Week 26. Patients continued to approach their genetic height potential, with the observed mean (SD) height SDS increasing from −1.40 (0.83) at trial enrollment to −1.15 (0.82) Week 26 (Fig. 1). The LS mean ∆height SDS was +0.25 (0.02) at Week 26. Continued growth was observed across all subgroups; higher growth outcomes were observed among subjects who were younger or of less advanced Tanner Stage, those treated with prior daily somatropin for a shorter duration of time (<1 year), and those with lower baseline peak GH stimulation results (Fig. 2). Similar growth rates were observed between males and females.

Fig. 1.

HSDS from GHD diagnosis to Week 26 of the fliGHt Trial. *Based on N = 143 at fliGHt baseline. Values in graph are observed means.

Fig. 2.

a–d Subgroup analyses of AHV and ∆HSDS by baseline characteristics following 26 weeks of lonapegsomatropin treatment.

At the time of enrollment into this trial (reflective of prior daily somatropin therapy), the mean (SD) IGF-1 SDS was 0.91 (1.25) for switch subjects (n = 143), with 32 subjects (22.4%) having an IGF-1 SDS >2. After switching to lonapegsomatropin, the LS mean (SE) for average IGF-1 SDS was sustained at 1.62 (0.10) and 1.65 (0.11) at Week 13 and Week 26, respectively, representing an approximate 0.7 SDS increase from treated baseline. Out of the 32 subjects who had IGF-1 values >2 SDS at baseline, 30 subjects had available IGF-1 measurement at 26 weeks and 70% of these (21 out of 30) had IGF-1 values >2 SDS. For subjects who had IGF-1 values ≤2 SDS at baseline, a much lower percentage of subjects (31.2%) had IGF-1 values >2 SDS at 26 weeks.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

The majority of children preferred weekly lonapegsomatropin via vial and syringe over their previous daily somatropin, and this preference increased with continued use (74.0% at Week 6 and 83.8% at Week 13); parents also preferred weekly lonapegsomatropin to their prior daily somatropin therapy (87.7% at Week 6 and 90.1% at Week 13) (Table 4). Individual reasons for child or parent preference for lonapegsomatropin or prior daily somatropin are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Treatment preference (PQ-C and PQ-P) at week 13

| Lonapegsomatropin* | Prior daily somatropin | No preference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child (n = 99), n (%) | 83 (83.8) | 9 (9.1) | 7 (7.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Child's reason for preference, % | How often I need to get injections (number of shots a week) | (88.0) | Less injection pain | (100) | − |

| Less annoyed by the injections | (65.1) | Less bruising, redness, and/or swelling | (55.6) | ||

| Less interference with (getting in the way of) my activities | (57.8) | Less burning, stinging, and/or soreness | (55.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Parent (n = 142),n (%) | 128 (90.1) | 7 (4.9) | 7 (4.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| Parent's reason for preference, % | How often my child needs to get injections (number of shots a week) | (95.3) | Easier to give the injection | (85.7) | − |

| Less interference with my child's activities | (68.0) | Easier to prepare the injection | (85.7) | ||

| Less interference with my activities | (53.9) | My child seems less afraid about getting injection | (71.4) | ||

The top 3 most cited reasons (check as many answers as you like) for preference are shown. PQ–C, preference questionnaire − child; PQ–P, preference questionnaire − parent.

Lonapegsomatropin was administered via vial/syringe.

At Week 13, 79% of children indicated that they would prefer to continue taking lonapegsomatropin after the end of the trial and 75% would recommend lonapegsomatropin to a friend who needed medicine to help them grow; responses from parents echoed these views. A control question was included to ensure that children remembered their daily somatropin treatment clearly enough to respond accurately to the preference questions; the majority (>70%) indicated that it was easy or very easy to remember their previous treatment.

Treatment burden was reduced after starting lonapegsomatropin as evidenced by a decrease in the summary score for the CSDS–C from 2.5 at Week 1, reflecting prior daily somatropin therapy, to 1.4 at Week 26 (p = 0.0086), representing an improvement. In tandem, the summary score for the CSDS-P decreased from 5.7 at Week 1 to 1.9 at Week 26 (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In the phase 3 fliGHt Trial, which enrolled treatment-experienced children with GHD, once-weekly lonapegsomatropin was well-tolerated and demonstrated an AE profile consistent with lonapegsomatropin in treatment-naïve patients in the phase 3 heiGHt Trial and the known profile of daily somatropin [16, 22]. Growth outcomes were consistent with clinical expectations for this broad pediatric population with a wide range of demographics and prior GH treatment histories [23]. Patients were able to switch from their previous daily somatropin therapy with no new safety signals and continued to grow well. Notably, once-weekly lonapegsomatropin was preferred by more than 80% of children and their parents over their previous daily somatropin therapy.

The evaluation of lonapegsomatropin in switch patients with a wide range of age and pubertal status was intended to complement the design and data obtained from the heiGHt Trial in treatment-naïve, prepubertal children [16]. To our knowledge, this is the first phase 3 trial among LAGHs in development evaluating safety and efficacy among treatment-experienced children with GHD. AEs were generally mild or moderate, and the types of AEs most commonly reported primarily represented typical ailments in a pediatric population. Glycemic and hormonal parameters were generally stable and remained within the normal range. Lonapegsomatropin was well-tolerated, as following the first injection the majority of patients had no or mild redness, no bruising, no swelling, and/or a pain score of ≤4 (on a scale of 0–10).

Growth outcomes were consistent with clinical expectations, given the wide age range enrolled in this study with differing demographics and disease characteristics [23]. For Δ height SDS, the rate of growth (slope of the lighter gray line in Fig. 1 representing previous daily somatropin treatment) was maintained upon entry into the fliGHt Trial as patients continued to approach their average parental height SDS. Subgroups generally responded as expected based on factors known to predispose to growth and IGF-1 response [24, 25, 26, 27], with younger patients, those with more severe GHD (peak stimulated GH ≤5 ng/mL at the time of GHD diagnosis), and those with shorter prior daily somatropin treatment durations displaying more pronounced rates of growth as measured by AHV and Δ height SDS.

In treatment-experienced patients, average IGF-1 increased by approximately 0.7 SDS upon switching from commercially available daily somatropin products to lonapegsomatropin. This incremental increase in IGF-1 SDS is consistent with the heiGHt Trial, where a difference in average IGF-1 was observed between once-weekly lonapegsomatropin and daily somatropin (mean 0.72 SDS vs. −0.02 SDS at Week 52, respectively) in treatment-naïve prepubertal children with GHD [16]. It is notable that subjects maintained a similar growth trajectory when switching from daily somatropin (mean dose 0.29 mg/kg/week upon entering the trial) to a lower dose of lonapegsomatropin (0.24 mg hGH/kg/week).

Results from the preference questionnaires revealed that the majority of patients and their parents preferred lonapegsomatropin even though patients may have used a pen or other device for their prior daily treatment versus a vial and syringe for once-weekly lonapegsomatropin treatment during this trial. In particular, both parents and children most commonly cited the frequency of injections as the reason for this preference, followed by less annoyance and interference with activities. This supports the relatively high importance of the frequency of treatment in determining treatment preference. Although a small number of patients and parents did prefer their previous daily somatropin, it is important to note that these assessments were based on lonapegsomatropin administered via vial and syringe. Lonapegsomatropin is now approved for use by the FDA in an Auto-Injector with dual-chamber cartridges in the USA, which is also currently being used in the open-label extension enliGHten Trial (NCT03344458) [15].

An observed decrease in CSDS scores from Week 1 suggests that switching from daily somatropin therapy to once-weekly lonapegsomatropin decreased the treatment burden for both children and their parents. Although a relatively low treatment burden with daily somatropin was reported at baseline, this may have reflected a degree of selection bias for the clinical trial, which primarily enrolled a North American, treatment-experienced population that may have become accustomed to daily somatropin administration.

The high treatment burden associated with daily injections of somatropin therapy is supported in the literature [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 28]. A qualitative study conducted in children with GHD and their parents/caregivers found a considerable treatment burden associated with treatment for GHD, identifying domains of physical, emotional well-being, and interference with activities [29]. Notably, the study identified treatment efficacy as a key modifier to alleviate treatment burden. Another study surveying both patients and parents/caregivers found that the refrigeration of somatropin products was considerably burdensome, especially when traveling, and was a major reason for missing a dose [6]. Lonapegsomatropin is stable at room temperature, which may help ease storage concerns.

The decrease in treatment burden and the high adherence to lonapegsomatropin observed in this trial support the notion that a LAGH may improve long-term patient outcomes [13]. Logistical interferences such as travel, school events, and social engagements have been found to negatively impact treatment schedules and thus treatment adherence due to delayed, missed, or forgotten doses [30]. As a once-weekly treatment, lonapegsomatropin could help overcome treatment barriers such as these and may also help improve outcomes in populations known for adherence challenges, especially in teens who are known to have more frequent issues with adherence [11].

This trial had some limitations. The design was single-arm and open-label, with a 26-week duration designed to complement the results of the randomized, controlled, 52-week heiGHt Trial [16]. The authors acknowledge that in the USA, where the majority of the subjects were recruited, there is a continuum of clinical characteristics that define pediatric GHD. Thus, this trial relied on more generalized trial entry criteria in terms of GHD than strict guideline-defined GH stimulation test cutoffs, as the main objective was to evaluate safety as well as efficacy in a broad GHD population. While this trial represented a broad range of demographics and GH treatment histories, real-world studies of longer durations are needed to fully understand the effect of lonapegsomatropin and the TransCon hGH Auto-Injector use on adherence and overall outcomes. Following completion of the fliGHt Trial, all subjects were eligible to continue in the long-term extension enliGHten Trial (NCT03344458); results from the enliGHten trial will provide long-term safety and efficacy outcomes with lonapegsomatropin.

In conclusion, results from this phase 3 fliGHt Trial demonstrated that switching to lonapegsomatropin was well-tolerated and maintained the known safety profile of daily somatropin. Across the heterogenous population enrolled, patients continued to approach their genetic height potential. Once-weekly lonapegsomatropin may represent a patient- and parent-preferred therapeutic option for children with GHD.

Statement of Ethics

The protocol was approved by a local institutional review board, independent Ethics Committee, or Human Research Ethics Committee prior to trial initiation, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was signed on August 29, 2017. All parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to patient participation in any patient-specific procedures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

A.K.M. has received research funding and is an Advisory Board Consultant for Ascendis Pharma, Novo Nordisk, OPKO, and Pfizer and is a speaker for Ascendis Pharma and Novo Nordisk. P.S. has been a speaker for Ascendis Pharma and Novo Nordisk and has received research funding from Ascendis Pharma, OPKO, Novo Nordisk, and Aeterna Zentaris, and is a member of the editorial board of Hormone Research in Paediatrics. K.L.R. has received research funding from Ascendis Pharma, is a speaker for Ascendis, and serves as a board member of The Human Growth Foundation. J.A. has received research funding from Ascendis Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Lumos, Soleno, Rhythm, and Saniona, and has served as a consultant for Consynance Therapeutics and Rhythm. K.A.W. has served as a consultant for Ascendis Pharma. S.J.C. has received research funding from Ascendis Pharma. W.S., M.M., S.D.C., A.S.K., and A.D.S. are employees of Ascendis Pharma, Inc. P.S.T. has received research funding from Ascendis Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and OPKO. U.N., L.D., and L.A.F. have nothing to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was sponsored by Ascendis Pharma Endocrinology Division A/S.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in collection and analysis of data and provided critical review, revisions, and feedback. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission. A.K.M., U.N., P.S., K.L.R., J.A., L.D., L.A.F., K.A.W., S.J.C., and P.S.T. contributed to collecting data and drafting and revising the manuscript. W.S., M.M., S.D.C., A.S.K., and A.D.S. contributed to analyzing data and drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and their families, the fliGHt Trial investigators, and study site staff. We also wish to acknowledge members of the trial's Independent Safety Committee; Andrew Occiano and Cindy Gode for writing assistance.

References

- 1.Guyda HJ. Four decades of growth hormone therapy for short children: what have we achieved? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999 Dec;84((12)):4307–16. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lustig RH. Optimizing growth hormone efficacy: an evidence-based analysis. Horm Res. 2004;62(Suppl 3):93–7. doi: 10.1159/000080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carel JC, Ecosse E, Nicolino M, Tauber M, Leger J, Cabrol S, et al. Adult height after long term treatment with recombinant growth hormone for idiopathic isolated growth hormone deficiency: observational follow up study of the French population based registry. BMJ. 2002 Jul 13;325((7355)):70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darendeliler F, Lindberg A, Wilton P. Response to growth hormone treatment in isolated growth hormone deficiency versus multiple pituitary hormone deficiency. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(Suppl 1):42–6. doi: 10.1159/000329161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polak M, Blair J, Kotnik P, Pournara E, Pedersen BT, Rohrer TR. Early growth hormone treatment start in childhood growth hormone deficiency improves near adult height: analysis from NordiNet^ International Outcome Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Nov;177((5)):421–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremidas D, Wisniewski T, Divino VM, Bala K, Olsen M, Germak J, et al. Administration burden associated with recombinant human growth hormone treatment: perspectives of patients and caregivers. J Pediatr Nurs. 2013 Jan;28((1)):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haverkamp F, Johansson L, Dumas H, Langham S, Tauber M, Veimo D, et al. Observations of nonadherence to recombinant human growth hormone therapy in clinical practice. Clin Ther. 2008 Feb;30((2)):307–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutfield WS, Derraik JG, Gunn AJ, Reid K, Delany T, Robinson E, et al. Non-compliance with growth hormone treatment in children is common and impairs linear growth. PLoS One. 2011 Jan 31;6((1)):e16223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher BG, Acerini CL. Understanding the growth hormone therapy adherence paradigm: a systematic review. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79((4)):189–96. doi: 10.1159/000350251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNamara M, Turner-Bowker DM, Westhead H, Yaworsky A, Palladino A, Gross H, et al. Factors driving patient preferences for growth hormone deficiency (GHD) injection regimen and injection device features: a discrete choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:781–93. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S239196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld RG, Bakker B. Compliance and persistence in pediatric and adult patients receiving growth hormone therapy. Endocr Pract. 2008 Mar;14((2)):143–54. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aydin BK, Aycan Z, Siklar Z, Berberoglu M, Ocal G, Cetinkaya S, et al. Adherence to growth hormone therapy: results of a multicenter study. Endocr Pract. 2014 Jan;20((1)):46–51. doi: 10.4158/EP13194.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen JS, Backeljauw PF, Bidlingmaier M, Biller BM, Boguszewski MC, Casanueva FF, et al. Growth hormone research society perspective on the development of long-acting growth hormone preparations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016 Jun;174((6)):C1–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprogoe K, Mortensen E, Karpf DB, Leff JA. The rationale and design of TransCon growth hormone for the treatment of growth hormone deficiency. Endocr Connect. 2017 Nov;6((8)):R171–81. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SKYTROFA (lonapegsomatropin-tcgd) [package insert] Hellerup, Denmark: Ascendis Pharma Endocrinology Division A/S; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton PS, Maniatis AK, Aghajanova E, Chertok E, Vlachopapadopoulou E, Lin Z, et al. Weekly lonapegsomatropin in treatment-naive children with growth hormone deficiency: the phase 3 heiGHt trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Oct 21;106((11)):3184–95. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatelain P, Malievskiy O, Radziuk K, Senatorova G, Abdou MO, Vlachopapadopoulou E, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of long-acting TransCon GH vs daily GH in childhood GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 May 1;102((5)):1673–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Z, Su Y, Chessler S, Komirenko A, Christoffersen ED, Shu AD. Estimating the weekly average IGF-1 from a single IGF-1 sample in children with growth hormone deficiency (GHD) treated with lonapegsomatropin. Horm Res Paediatr. 2021;94(suppl 2):76. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Z, Shu AD, Bach M, Miller BS, Rogol AD. Average IGF-1 prediction for once-weekly lonapegsomatropin in children with growth hormone deficiency. J Endocr Soc. 2022 Jan 1;6((1)):bvab168. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidlingmaier M, Friedrich N, Emeny RT, Spranger J, Wolthers OD, Roswall J, et al. Reference intervals for insulin-like growth factor-1 (igf-i) from birth to senescence: results from a multicenter study using a new automated chemiluminescence IGF-I immunoassay conforming to recent international recommendations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 May;99((5)):1712–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteside SP. Adapting the Sheehan disability scale to assess child and parent impairment related to childhood anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009 Sep;38((5)):721–30. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimberg A, DiVall SA, Polychronakos C, Allen DB, Cohen LE, Quintos JB, et al. Guidelines for growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I treatment in children and adolescents: growth hormone deficiency, idiopathic short stature, and primary insulin-like growth factor-I deficiency. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;86((6)):361–97. doi: 10.1159/000452150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakker B, Frane J, Anhalt H, Lippe B, Rosenfeld RG. Height velocity targets from the national cooperative growth study for first-year growth hormone responses in short children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Feb;93((2)):352–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranke MB, Lindberg A, Chatelain P, Wilton P, Cutfield W, Albertsson-Wikland K, et al. Derivation and validation of a mathematical model for predicting the response to exogenous recombinant human growth hormone (GH) in prepubertal children with idiopathic GH deficiency. KIGS international board. Kabi Pharmacia International Growth Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999 Apr;84((4)):1174–83. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lofqvist C, Andersson E, Gelander L, Rosberg S, Blum WF, Albertsson Wikland K. Reference values for IGF-I throughout childhood and adolescence: a model that accounts simultaneously for the effect of gender, age, and puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Dec;86((12)):5870–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranke MB, Lindberg A. Observed and predicted growth responses in prepubertal children with growth disorders: guidance of growth hormone treatment by empirical variables. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Mar;95((3)):1229–1237. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straetemans S, De Schepper J, Thomas M, Verlinde F, Rooman R, Bespeed Validation of prediction models for near adult height in children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency treated with growth hormone: a Belgian Registry Study. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;86((3)):161–8. doi: 10.1159/000448553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplowitz P, Manjelievskaia J, Lopez-Gonzalez L, Morrow CD, Pitukcheewanont P, Smith A. Economic burden of growth hormone deficiency in a US pediatric population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021 Aug;27((8)):1118–28. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.21030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brod M, Højbjerre L, Alolga SL, Beck JF, Wilkinson L, Rasmussen MH. Understanding treatment burden for children treated for growth hormone deficiency. Patient. 2017 Oct;10((5)):653–66. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham S, Auyeung V, Weinman J. Exploring potentially modifiable factors that influence treatment non-adherence amongst pediatric growth hormone deficiency: a Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1889–99. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S268972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.