Abstract

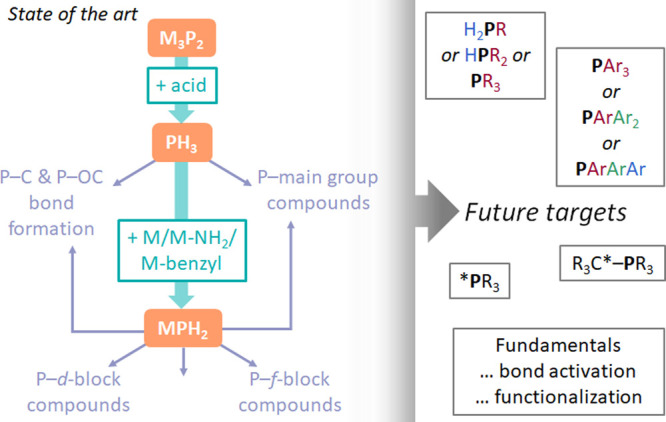

Appetite for reactions involving PH3 has grown in the past few years. This in part is due to the ability to generate PH3 cleanly and safely via digestion of cheap metal phosphides with acids, thus avoiding pressurized cylinders and specialized equipment. In this perspective we highlight current trends in forming new P–C/P–OC bonds with PH3 and discuss the challenges involved with selectivity and product separation encumbering these reactions. We highlight the reactivity of PH3 with main group reagents, building on the early pioneering work with transition metal complexes and PH3. Additionally, we highlight the recent renewal of interest in alkali metal sources of H2P– which are proving to be useful synthons for chemistry across the periodic table. Such MPH2 sources are being used to generate the desired products in a more controlled fashion and are allowing access to unexplored phosphorus-containing species.

1. Introduction

There is an acute need to undertake drastic changes in the way we consume the Earth’s vital and finite resources, with much of this linked to changes needed to policies and practices of governments.1,2 However, this should also bring into strong focus our need to undertake sustainable synthesis.3,4 With this comes the need to develop new methods with which to undertake novel bond transformations; use reagents that avoid the generation of exogenous waste which requires protracted purification procedures; move away from harmful solvents; use feedstocks that are less activated (or come directly from the source, e.g., in the Earth’s crust); and use metals that are abundant (e.g., rock-forming metals) both in heterogeneous/homogeneous catalysis and in devices/materials.5

Rather than providing prescriptive coverage of all reports on transformations involving PH3, including the pioneering research into stoichiometric reactions with PH3,6 this perspective serves to highlight trends in the applications of PH3, the “routine” P–C bond forming reactions that are base-mediated (i.e., reductive coupling) or involve the hydrofunctionalization of unsaturated bonds. This perspective will also cover more unusual transformations that form P–C bonds via other means, along with modern main group bond transformations and reactions with metals (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. An Overview of the Key Discussion Points Presented in This Perspective.

The latter portion of this perspective goes beyond PH3 and showcases the chemistry of the H2P– anion. Recently, the use of alkali metal phosphides as a source of H2P– has been receiving renewed interest. We will highlight some of the remarkable implementations of such salts, both in organic transformations and as promising reagents in the preparation of notable main group, transition metal, and f-block metal species.

We would be remiss not to briefly mention the numerous reports, during a prolific period of PH3 research that took place between the late 1960s through to the early 1990s, on the reaction between PH3 and transition metal (TM) complexes.7−15 Formation of TM complexes bearing the [TM]–PH3 motif as well as formal oxidative addition/hydride abstraction to form [TM]–PH2 and [TM]–(μ-PH2) motifs have been identified, with analysis ranging from multinuclear NMR and IR data only, through to those also reporting single crystal X-ray diffraction data. For example, Jones and co-workers reported the formation and isolation of a remarkably air-stable trans-[RuCl2(PH3)4] complex.16 However, further study into reactivity with these complexes has rarely been explored17 and will therefore not be the focus of this perspective. However, this highlights the many seemingly simple areas of PH3 research that are yet to be fully investigated.

2. An Important Note on Safety

It would be irresponsible not to emphasize the dangers associated with handling PH3. PH3 is a highly toxic gas that is spontaneously flammable in air. The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) places a time-weighted average limit on exposure at 0.05 ppm (which is the concentration of a substance to which most workers can be exposed without adverse effects), with a short-term exposure limit of 0.15 ppm (which means a 15 min time-weighted average exposure should not be exceeded at any time during an 8 h workday).18 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) list 0.3 ppm as the time-weighted average limit and 1 ppm as the short-term exposure limit (10 h, 15 min respectively). The US Environmental Protection Agency lists that the 4 h LC50 for PH3 in rats is 11 ppm.19 To put these numbers into context, the NIOSH time-weighted average limit for CO is 35 ppm and the NIOSH short-term exposure limit for HCN is 4.7 ppm,20 while the 1 h LC50 for HCN in rats is 139–144 ppm.21,22 In short, handling of pressurized cylinders of PH3 requires a robust risk assessment/COSHH assessment and rigorous safety protocols, not least a PH3 monitor to ensure the safety of not only the chemist handling the substance but also other researchers in the lab. The fume hood setup must include NaOCl scrubbers or a PH3 burner/H2O spray to quench unreacted PH3. Akin to our responsibility to study and develop more sustainable approaches to synthesis, safe use and quenching of this toxic gas, avoiding exposure of researchers and the environment to this species, is paramount.

3. Reacting PH3 To Form P–C/P–OC Bonds

PH3 is the next downstream output from elemental phosphorus, which comes directly from industrial large-scale processing of phosphate rock.23 Numerous reviews on functionalization of P4 exist, but the tetra-nuclear nature of this feedstock means that controlled, direct, or catalytic functionalization of P4 into, for example, 4PR3 is not well-documented.24,25 Instead, conversion of P4 into PH3 or PCl3 and onward reaction to form organophosphines is the more traditional pathway. Onward reactions of PCl3 with organic substrates to prepare P–C(sp3) bonds are well documented, but wasteful in terms of atom economy.

P–C bond forming reactions with PH3 range from stoichiometric-in-base-mediated reactions with alkyl halides through to hydrophosphination in the presence of a metal catalyst, radical initiator, or a base. In many cases we invariably access products of the form PR3, although there are examples where HPR2 and H2PR are produced (vide infra). Even the hydrophosphination literature has limitations: work on catalytic hydrophosphination has routinely reported on the formation of the tertiary phosphine product as the major species, and only limited progress in diversifying the structure of the products, or the reaction selectivity, has been made. The reason that PR3 is formed preferentially can be linked to the enhanced reactivity of the product compared to the starting materials, i.e. PH3 < H2PR < HPR2, and accessing H2PR or HPR2 tends to be achieved by limiting substrate stoichiometry rather than any greater form of reaction control. Stoichiometric-in-base transformations are simple to undertake and are well documented, but it could be argued that they serve to demonstrate the limitations in the organic transformations undertaken using PH3: the reaction of RCl + base + PH3 is simply the inverse of the classical method of using RH + base (or RCl + 2base) + PCl3.

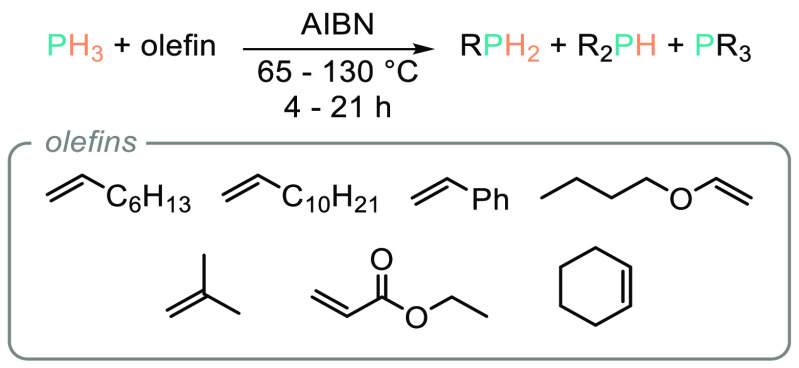

PH3 is a reactive substrate, and the early work on the formation of phosphonium salts from PH3 and formaldehyde dates back to at least 1888,26 with applications from this seminal study still very relevant today.27 Building upon work from Stiles et al. using photochemical initiation,28 an early report on catalytic functionalization of PH3 came from Rauhut and co-workers29 where they disclosed the hydrophosphination of acrylonitrile using PH3 and aqueous KOH at room temperature. The reaction is mild, but is somewhat lacking in control, producing mixtures of primary, secondary, and tertiary cyanoethyl phosphines. Excess acrylonitrile allowed the formation of the tris-substituted product in 80% yield, and the secondary product could be formed in 58–63% when an excess of PH3 is employed, while the primary cyanoethyl species is formed in 52% yield, but an autoclave operating at high pressure of PH3 is needed (28–32 atm). The mono- and bis-substituted products were further employed in radical-mediated hydrophosphination reactions.30 Rauhut and co-workers also employed azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN) as a radical initiator to hydrophosphinate with a range of alkenes in the presence of PH3.30 Interestingly, although the ratio of primary/secondary/tertiary organophosphine product is often in the region of 1:1:1, reactions with unactivated systems such as 1-octene, 1-dodecene, cyclohexene, isobutylene, and butyl vinyl ether are reported (Scheme 2). In fact, 1-octene (1 mol), PH3 (0.33 mol), and AIBN (5 mol %) is an exothermic reaction that generated a reaction temperature of 80–100 °C and produced 83% tris(octyl)phosphine cleanly after 6 h; this reaction is furthermore impressive as transformation of unactivated reagents has largely eluded modern hydrophosphination catalysis.31

Scheme 2. Rauhut and Co-workers’ Early Study into Radical Mediated Hydrophosphination of Activated and Unactivated Alkenes.

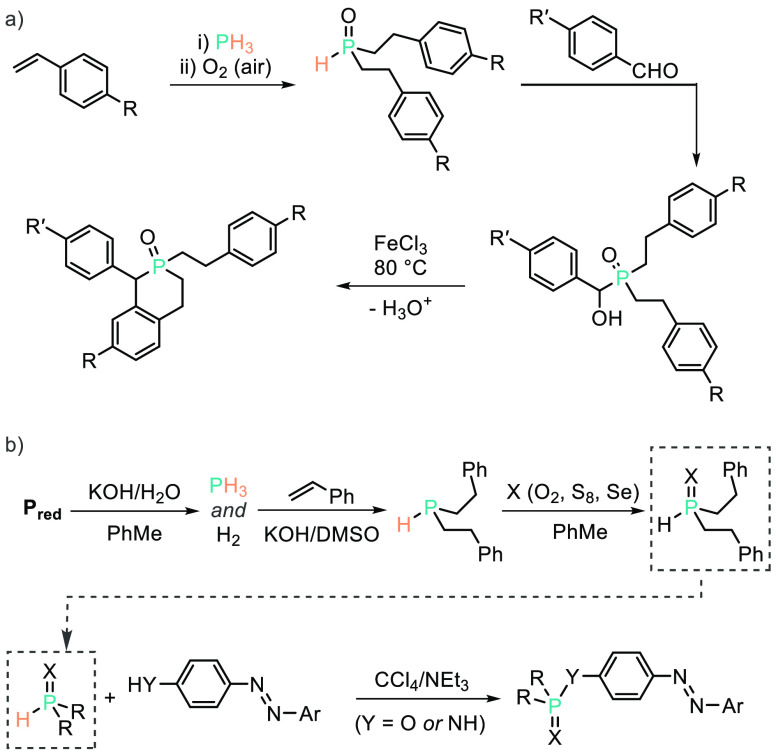

Similar to the earlier work of Rauhut and co-workers, Trofimov and co-workers have recently reported base-mediated hydrophosphination of 2 equiv. of styrene (or 4-tBu-styrene) with PH3. The authors have published two possible onward transformations. The first is oxidation, to generate the anti-Markovnikov secondary phosphine oxide product, which is then used as a nucleophile to react with an aldehyde and finally, in the presence of FeCl3, hydroxide abstraction to generate a carbocation in an SN1-type process. This then allows cyclization to form a phosphinoline oxide product (Scheme 3a).32 The second possible onward transformation is P–O or P–N bond formation at the para-position of azobenzenes, using a simple base to carry out the coupling reaction (Scheme 3b).33 The UV/vis-mediated isomerization of the azo functionality was then investigated. Ragogna employed AIBN to prepare tertiary fluorinated alkyl phosphines which can then be transformed into phosphonium salts to attenuate the properties of UV-curable resins.34 Ragogna has also employed the early methods to prepare phosphinated lignin, which is effective as a metal scavenger.35

Scheme 3. Trofimov Has Employed Methods Similar to Those of Rauhut and Co-workers, But Has Extended This To Prepare (a) Phosphacycles and (b) Functionalized Diazo Compounds.

A hydrophosphination that, unsurprisingly, does not need any activating agents or a catalyst is the reaction of PH3 with the highly activated imine 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-imine, generating 4.75 g (96% yield) of the geminal substituted NH2,PH2 product from a large-scale synthesis.36

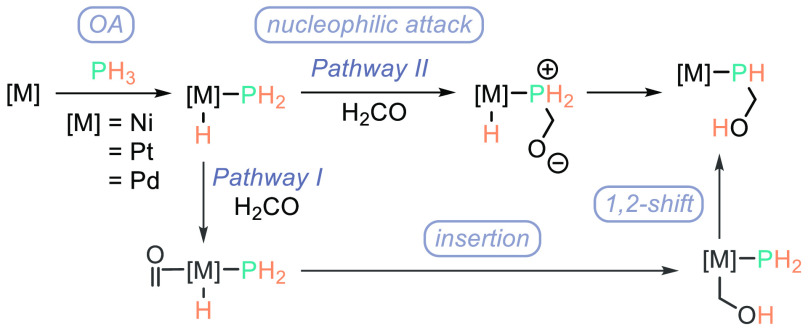

In contrast, many hydrophosphination reactions involving PH3 have employed transition metal catalysts; Pringle undertook the seminal work in this field and used platinum chloride salts, as well as tetrakis(phosphino) Pt, Pd, and Ni complexes for the reaction of formaldehyde with PH3.37−39 Pringle also reported the use of [Pt(norbornene)3] as an effective precatalyst for the reaction of PH3 with ethyl acrylate.40 Finally, a series of tris(phosphino) Ni, Pd, Pt catalysts as well as tris(phosphino) iridium chloride complexes were reported as competent catalysts for the hydrophosphination of acrylonitrile.41,42 For all three unsaturated substrates the tertiary PR3 product is formed as the sole product, although a mixture of products is often observed in situ due to the stepwise nature of the reactions. A generic catalytic cycle involves coordination of PH3 with the unsaturated M(0) center, oxidative addition (OA) to generate a mixed metal(II) hydrido phosphide species, and then insertion of the unsaturated bond into the M–H bond followed by a reductive 1,2-shift step to generate the M–PR3 product. An alternative pathway for formaldehyde involves a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl moiety by M–PH2 forming a zwitterion, and then hydride transfer generates the M–PR3 product (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Pringle’s Postulated Mechanism for the Hydrophosphination of Formaldehyde.

More recently Trifonov reported the use of 1,3-diisopropylimidazol-2-ylidene and 1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene as well as their complexes [(Me3Si)2N]2M(NHC)2] (M = Ca, Yb, Sm) as precatalysts for hydrophosphination with PH3. Remarkably, they report the generation of primary phosphines based on the feedstock stoichiometry.43 A particularly intriguing reaction from this publication is the formation of tri(Z-styryl)phosphane; the acidic nature of both the phenylacetylene and PH3 along with the selectivity for the kinetic all-Z product is remarkable. Transformations of this type warrant further investigation in terms of substrate scope (and with this E/Z selectivity) and onward functionalization with an eye toward applications.

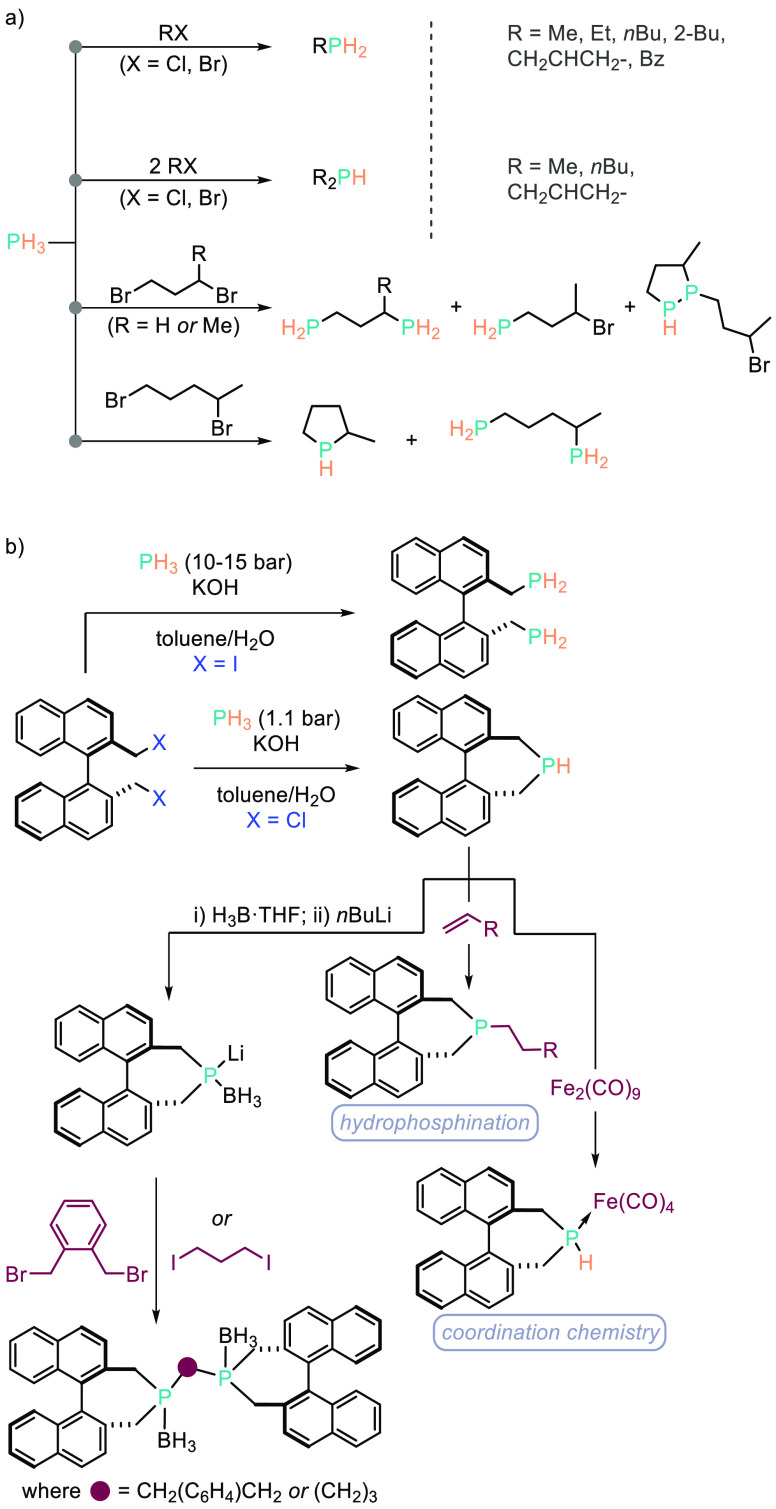

Stoichiometric transformations are prevalent in the literature and follow similar trends in terms of the products formed and the makeup of the transformation. For example, Stelzer and Sheldrick report a KOtBu route to prepare water-soluble phosphindoles/phosphindole oxides from PH3.44 Stelzer has also reported on exploiting the inherent equilibrium between PH3 + OH– ⇌ H2P– + H2O when aqueous DMSO/KOH solution (or with the inclusion of phase transfer catalysts such as (nBu)4NCl) is used, thus allowing generation of low concentrations of the highly nucleophilic H2P– ion for the selective reaction with organohalides forming (stoichiometry-driven) primary or secondary alkyl phosphines, bis(alkyl)phosphines, and cyclic phosphines (Scheme 5a).45 Stelzer and co-workers have also employed iodine to prepare structurally exciting PH2–BINAP (1,1′-binaphthyl) and PH–BINAP systems (Scheme 5b).46

Scheme 5. Stelzer and Co-workers Have Prepared a Wealth of Different Phosphorus Compounds (a) Using a Base and/or Phase-Transfer Conditions and (b) Employing These Methods To Prepare 1,1′-BINAP-Derivatives from PH3.

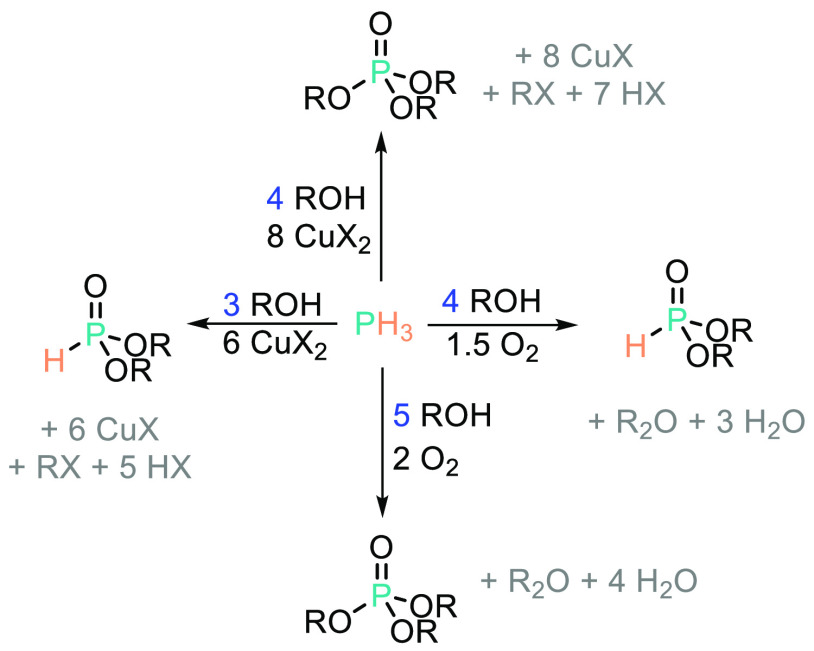

Borangazieva and co-workers have reported an I2/pyridine system for the formation of trialkyl phosphates from PH3 and methanol/ethanol/butanol/amyl alcohol/octanol.47 This methodology was further extended to the preparation of primary aminoalkyl phosphines.48 A change to stoichiometric CuCl2 in CCl4 gives selective formation of the dialkyl phosphite (HP(O)(OiPr)2) when isopropanol is employed (Scheme 6).49 Further study into the reaction, and inclusion of quinone as a reductant, has also been reported.50

Scheme 6. Borangazieva and Co-workers Have Showed That Reagent Stoichiometry Can Be Used to Influence the Product Distribution When Preparing P–OR Bonds.

However, in general, secondary and primary species are observed as side products in many reactions. Given the challenges associated with purification of reactive phosphines, particularly those that are the product of hydrophosphination reactions (where the product is invariably an alkyl phosphine and thus more prone to oxidation), selective synthesis of a primary or secondary or tertiary phosphine is desirable. Moreover, when we look at commercial organophosphines, very few tertiary monophosphines are symmetrically substituted; there are key organophosphines such as PPh3, PCy3, and PtBu3, but organophosphines routinely used in, for example, cross-coupling reactions include SPhos (2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl) and XPhos (2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,4′,6′-triisopropylbiphenyl), and bis(phosphines) such as dppf (1,1′-ferrocenediyl-bis(diphenylphosphine), XantPhos (4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-9,9-dimethylxanthene), and dppe (1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane) to name but a few. Here we raise another issue of a pure atom-economy-driven approach to PH3 functionalization: that being that the preparation of P–Ar bonds is limited to work from Dorfman and Levina, and more recently Wolf (vide infra).

4. PH3 Reacting with Compounds of the p-block

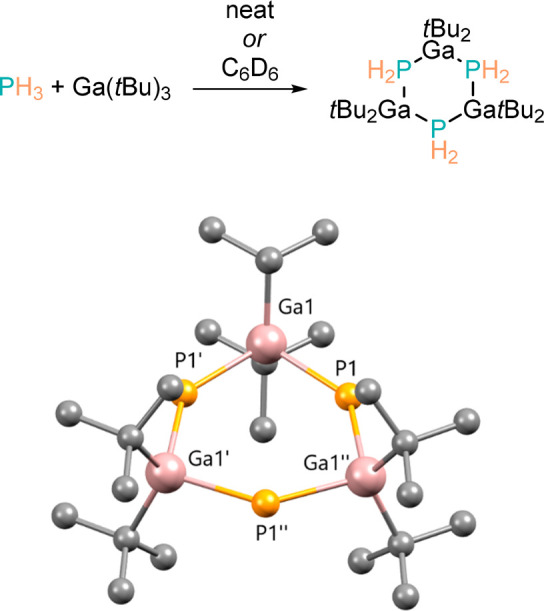

In the 1990s, Cowley and Jones undertook investigations into the reactivity of PH3 with an alkyl gallium compound with a view to preparing precursors for OMCVD processes (organometallic chemical vapor deposition). The authors present a highly sensitive μ-PH2 cluster which undergoes slow decomposition at 200 °C (Scheme 7).51

Scheme 7. Ga(tBu)3 Reacts with PH3 To Form Gallium Phosphide Ring Structures.

The POV-Ray image of the single crystal X-ray structure (CCDC 1197532) shows a distorted 6-membered ring, but this is completely planar with no puckering. All H atoms removed for clarity.

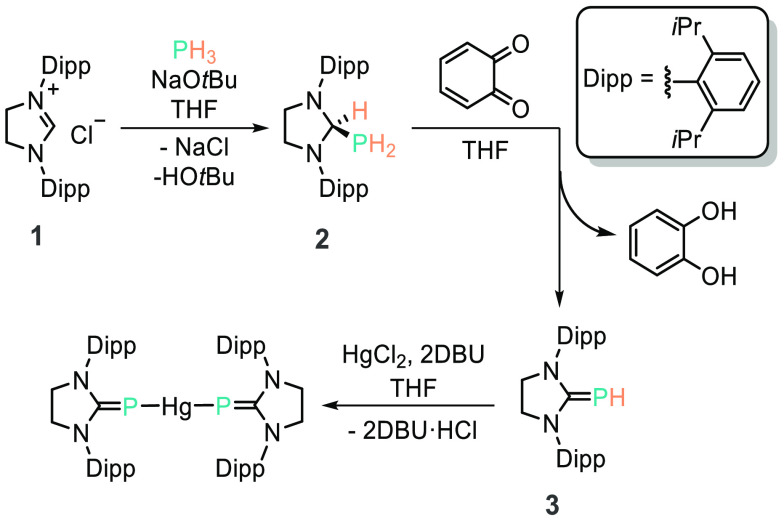

Further reports on reactions of PH3, which we may consider being in the realm of main group bond transformations, are those involving NHCs and their heavier group 14 congeners. Grützmacher and Pringle reported the in situ generation of the SIPr (1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazolidine-2-ylidene) NHC (1, Scheme 8) from the chloride salt, which forms the PH2-imidazolidine product (2) from reaction with PH3 and base (or the tert-butoxide adduct of NaPH2). This product can then undergo hydrogen abstraction, driven by the aromatization of ortho-quinone, which allows the formation of the formal phosphinidine-carbene adduct (3).52 This latter species was shown to undergo complexation with HgCl2.

Scheme 8. Grützmacher’s Reported Oxidative Addition of PH3 by an NHC Which Can Then Form the Phosphinidene, 3, Driven by the Aromatization of 1,2-Benzoquinone.

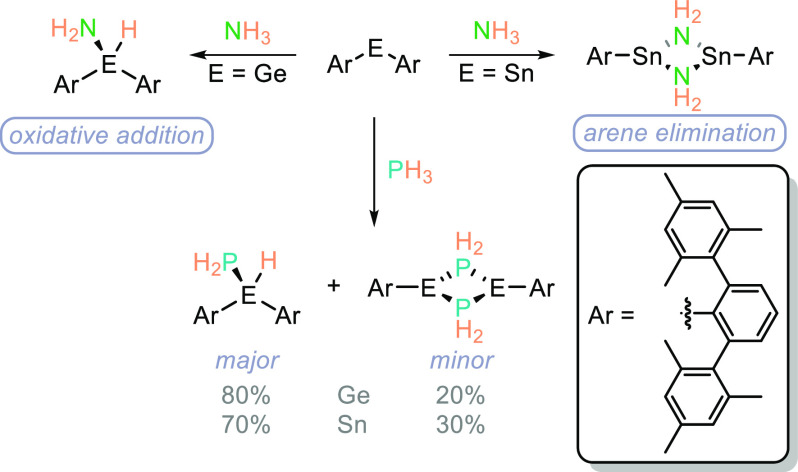

Ragogna and Power have shown that PH3 can oxidatively add to tetrylenes. The authors note a divergence in reactivity when comparing the chemistry of NH353−56 and PH3; the former gives the OA product with Ge and the arene elimination dimeric product with the Sn congener (Scheme 9). However, when PH3 is employed a mixture of the OA and arene elimination dimer is formed with both Ge and Sn (the OA product is the major species in both cases).57 Similar to the work of Ragogna and Power, where there is a discrepancy between the reactivity of the lighter and heavier pnictogens, Driess has demonstrated a difference in reactivity of PH3 compared to AsH3 when undertaking OA to silylene compounds.58 PH3 generates the OA product, whereas with AsH3, although OA takes place, there is an equilibrium between the arsenide product and the isomerized arsinidine species, making use of the ligand system to invoke this process.

Scheme 9. Ragogna and Power Have Demonstrated the Divergent Reactivity of NH3 and PH3 That Is Observed in the Presence of Group 14 Tetrylenes.

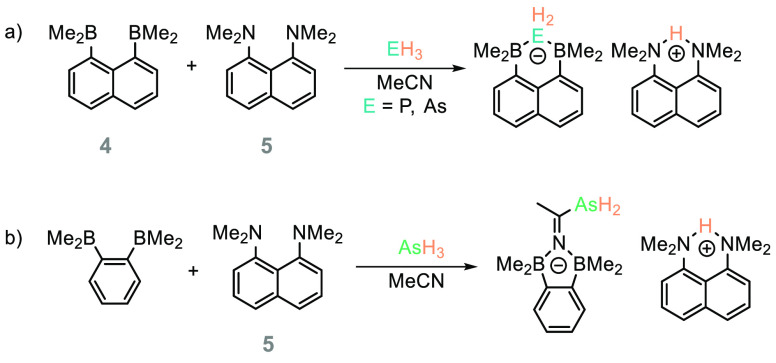

Mitzel has employed both hydride sponge (4) and proton sponge (5, Scheme 10) as a frustrated Lewis pair (FLP) system to activate a range of small molecules, including PH3.595 undertakes proton abstraction while 4 forms the phosphide adduct, and the authors note that QTAIM (quantum theory of atoms in molecules) analysis indicated that the B–P bond interaction is the most covalent B–E bond interaction when compared to the N, As, O, S, and Se analogues in the study. Interestingly, when the hydride sponge is modified, although PH3 undergoes the same activation event, AsH3 undergoes a further transformation with the MeCN solvent. If we consider the wealth of transformations that can be undertaken both stoichiometrically and catalytically using FLPs,60−63 in particular reactions that use H2 that has been activated,64,65 this hints that this could be a rich vein of research. Indeed, modification of the FLP structure could enable enantioselective transfer of the H2P– and H+ fragments to an organic substrate.

Scheme 10. (a) Proton and Hydride Sponge Have Been Used To Activate PH3 and AsH3; (b) with 1,2-Bis(dimethylboranyl)benzene, the Reactivity of PH3 Is Unchanged (Not Shown), but AsH3 Reacts with Concomitant MeCN Functionalization.

5. Future Targets

At this stage it is useful to consider several aspects as we look toward future synthetic development targets with PH3 or MPH2. In an atom-economic, chemoselective manner, with wide-ranging functional group tolerance, key targets should include the following:

-

1.

Controlled synthesis of primary or secondary or tertiary organophosphines. Reactions need to avoid the formation of mixtures that require complicated cleanup procedures or additional reduction steps to access the P(III) species from the P(V) phosphine oxide;

-

2.

The synthesis of unsymmetrically substituted phosphines from PH3 or MPH2 and ultimately C- or P-stereogenic phosphines;

-

3.

The preparation of P–Ar phosphines from PH3 or MPH2, e.g. PAr3 through to P*Ar1Ar2Ar3 selectively;

-

4.

Unique methods not only to activate PH3 but also undertake onward functionalization, e.g. chemistry beyond hydrofunctionalization.

However, to make such advances PH3 and MPH2 needs to become more accessible to a wider range of researchers. Indeed, we envisage that many advances will be possible simply through PH3 (or analogues of PH3) being used more widely in research.

6. Alternative Sources of PH3

The industrial standard for the production of PH3 is the base-mediated disproportionation of white phosphorus, in the so-called Hoesch process.66 P4 is treated with sodium or potassium hydroxide at slightly elevated temperatures (50 °C). With very careful conditions the gas can be collected in ∼95% purity, though this procedure is not particularly practical for a research laboratory. The lab-scale synthesis of PH3 has been achieved in a number of ways: by the treatment of PCl3 with Na metal (followed by hydrolysis),67 the high-temperature treatment of black phosphorus in liquid hydrogen,68 and the pyrolysis of either hypophosphorous acid, phosphorous acid, or a salt of one of these acids.69 In 1967, the pyrolysis of phosphorous acid was described as the “most convenient” method for the generation of PH3;69 however, in a modern research laboratory the idea of isolating PH3 as a liquid by consecutive condensation and distillation is perhaps a barrier to implementation for many researchers. Additionally, Trofimov reported the generation of PH3 from red phosphorus by treatment with aqueous KOH at 65–75 °C; however, this reaction is concomitant with the generation of dihydrogen and as such is limited to reactants that are inert toward dihydrogen and moisture.70,71

6.1. Metal Phosphides for PH3 Release

Handling pressurized gases, irrespective of toxicity, requires a level of rigor that is not necessarily required when handling solids. Recent reports on the use of metal phosphides, e.g. Zn3P2, AlP, and Mg3P2, for the in situ release of PH3 by digestion using an acid, e.g. HCl, provide a route to PH3 research that was previously inaccessible to many. However, PH3 is still released from the metal phosphide; indeed these phosphides are routinely used as pesticides because of their ability to release PH3 on ingestion, which is fatal. Therefore, although easy to obtain, inexpensive (approximately $74 per kg72), and easy to handle, the same level of care and safety assessment should be taken when handling these simple salts as handling PH3 gas cylinders.

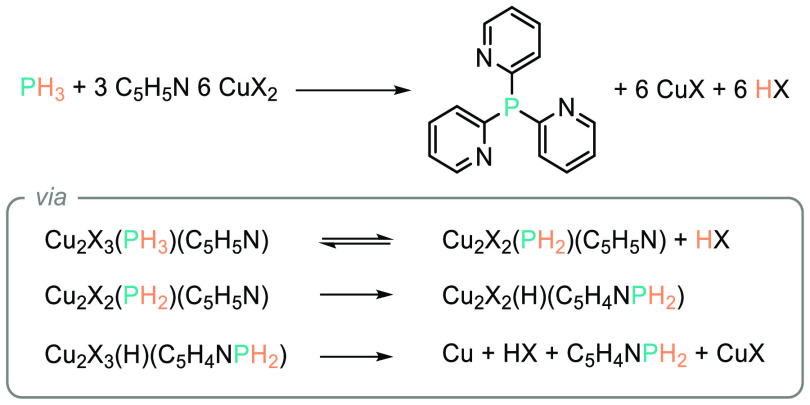

One of the earliest reports on the in situ generation of PH3 from a metal phosphide (Zn3P2) for the preparation of high-value P–C bonds was reported by Dorfman and Levina in 1992.73 The authors employ stoichiometric CuCl2 or Cu(OAc)2, which, in the presence of pyridine in the coordination sphere, is proposed to acidify the P–H bond in PH3, forming a putative Cu-phosphide intermediate along with HCl/HOAc. It is postulated that the resonance structure of pyridine is such that it renders the ortho- and para- positions δ+, and this, coupled with the proximity of the ortho-position to the copper center, renders this position prone to attack by H2P–, generating the tris(pyridin-2-yl)phosphane product selectively (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11. Dorfman Provides a Rare Example of P–Arene Bond Formation Using PH3.

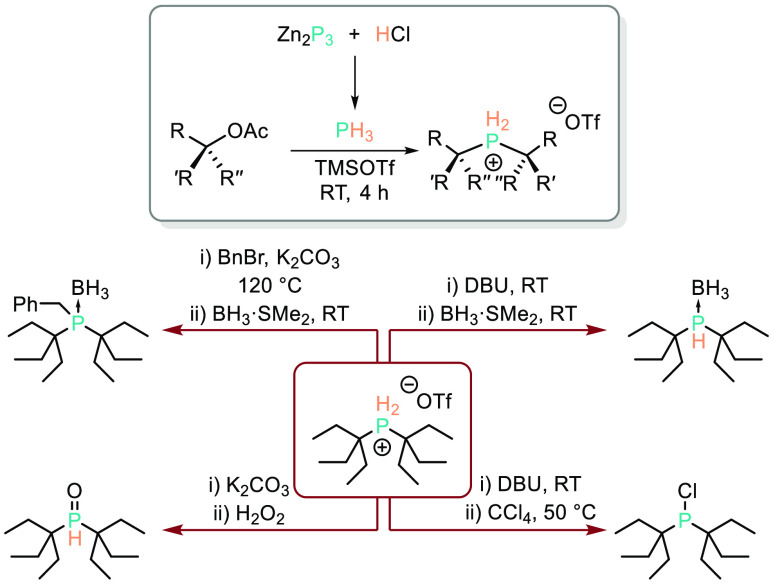

PH3 generated by decomposition of Zn3P2 has been detailed more recently by Ball74 and Wolf.75 Ball has elegantly demonstrated the application of in situ generated PH3 for the synthesis of tert-alkyl phosphonium triflates, where the byproduct of the reaction is TMSOAc. Due to the high levels of substitution these products cannot be formed using a hydrophosphination route, while the conventional route to secondary alkyl phosphines, R2PH, would employ PCl3 and organomagnesium or organolithium reagent, followed by reduction of the remaining P–Cl bond with a hydride reagent. Ball has shown that these phosphonium salts can then be converted into the secondary phosphine chloride on reaction with 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) and CCl4, transformed into their BH3 protected phosphine congener (using DBU/BH3·SMe2), benzylated (BnBr then protected using BH3·SMe2) or oxidized to the phosphine oxide (using K2CO3 then H2O2), Scheme 12.

Scheme 12. Ball Has Demonstrated That in Situ Formation of PH3 from Zn3P2 Can Be Used to Excellent Effect, Furnishing Otherwise Challenging To Access tert-Alkyl Phosphines via the Phosphonium Salt.

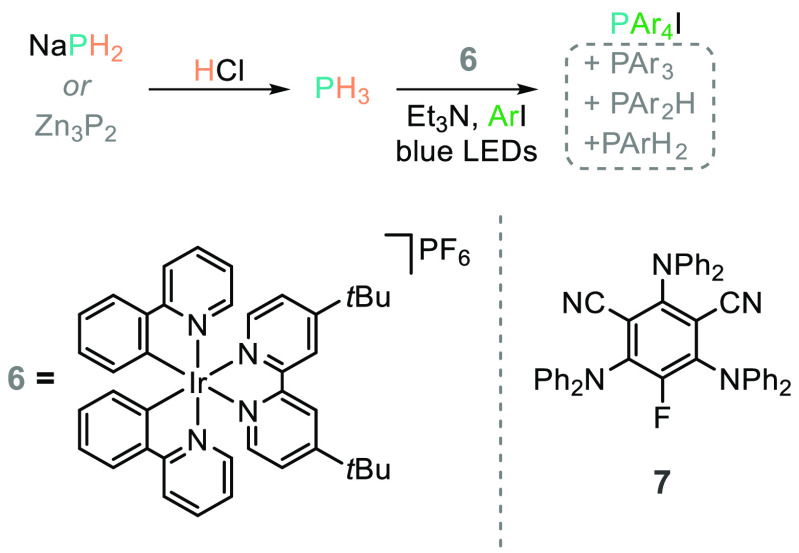

Using a similar reaction setup to Ball, where Zn3P2 is digested using HCl in an H-tube and the in situ generated PH3 can then react with substrate in the second chamber, Wolf employed iridium photocatalyst (6) NEt3, PhI, and blue LEDs to prepare Ph4P+I– in a 35% yield after 48 h (Scheme 13). However, use of NaPH2 as an alternative to PH3 was more successful, generating the product in 77% yield after 24 h. Extending the substrate scope beyond PhI, but continuing to use NaPH2, the authors show selective triarylation using sterically encumbered 2-methyliodobenzene (63% Ar3P with no other arylation products observed) and 2-methoxyiodobenzene (42% Ar4P+ observed only). While 4-methyliodobenzene gives 64% Ar4P+/<5% Ar3P, 3-methyliodobenzene gives 61%/6% as Ar4P+/Ar3P and 3-methoxyiodobenzene gives 53%/<5% as Ar4P+/Ar3P. The remaining ArI substrates give less attractive ratios of Ar4P+/Ar3P and/or conversions below 50%. A change to an organophotocatalyst (7) can lead to modest adjustments in the ratio/conversion to product(s). The reaction mechanism is postulated to proceed via sequential arylation steps, where a photogenerated Ar• reacts with [P]•. Reaction profiling shows a rapid buildup of Ph2PH as a major species, along with PhPH2, which after 5 h are depleted as the onward reaction of these intermediates takes place, with Ar4P+ eventually being the dominant product. The reaction requires 2 mol % 6, 11 equiv of ArI, and 15 equiv of NEt3 (or 10 mol % 7, 13 equiv of ArI, 16 equiv of NEt3); clearly elegant but, excitingly, with room for modification and diversification.

Scheme 13. Photocatalysis Has Been Used by Wolf and Co-workers To Prepare Arylphosphines from PH3.

6.2. In Situ PH3 Generation from P(OR)3

Liptrot and co-workers recently presented a Cu-catalyzed route to generate PH3 in 30 min from P(OPh)3, using HBpin as a reducing agent. PH3 was generated in 89% conversion on a 0.1 mmol scale. The in situ generated PH3 was then directly implemented in the quantitative catalytic hydrophosphination of phenyl isocyanate in a two-pot procedure.76

7. The PH2 Anion

7.1. Reactions of MPH2 with p-Block Compounds

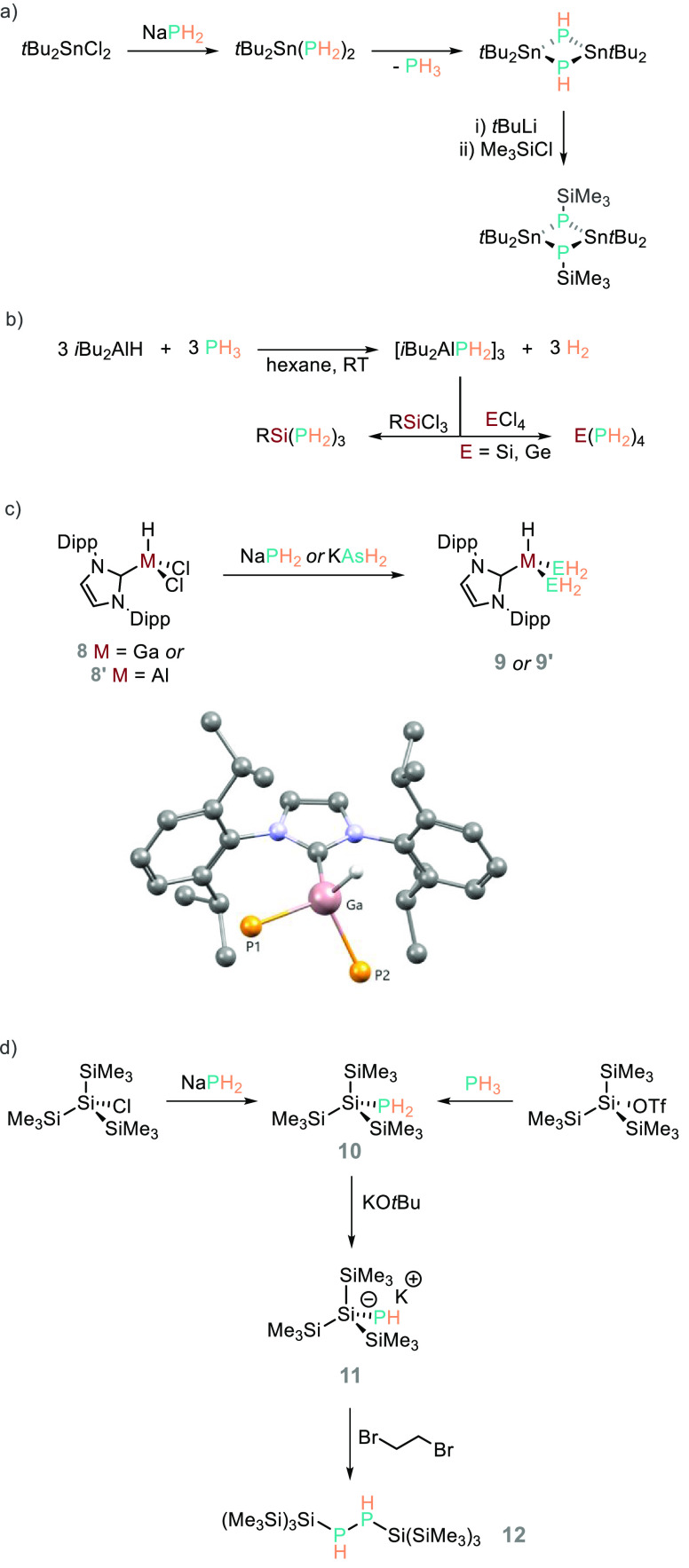

Alkali metal sources of H2P–, e.g. LiPH2, NaPH2, KPH2, have been largely ignored in the literature until very recently, but given that they are prepared from PH3 and clearly have the potential to act as an alternative source of PH3 (c.f., Wolf), they are an intriguing reagent that deserves further investigation. Their limited use until now may be linked to the routes of synthesis and the instability of these MPH2 species. Joannis reported the first synthesis of Na and K dihydrogenphosphide in 1894;77,78 these compounds were further studied alongside the synthesis of LiPH2.79−84 Later still, the rubidium85 and cesium analogues were reported and the series of alkali metal dihydrogenphosphides were further characterized.86 These species were prepared by condensing PH3 in NH3(l) and reacting with the metal or metal amide. Handling the Li and Na adduct is not trivial; LiPH2 decomposes at room temperature while NaPH2 is noted to decompose above 393 K. The KPH2 and RbPH2 species are noted to decompose above 476 K, making them a robust reagent, and it is thus surprising that KPH2 has not been used more widely in the literature. The poor solubility of KPH2 can be improved by the addition of 18-crown-6 (catalytic quantities can be used) and/or the preparation of phthalimide anion adducts.87 It is worth noting that other routes to H2P– anion adducts (e.g., phthalate, alkoxide complexes) are known.88,89 Several rudimentary transformations of MPH2 have been reported, where the products are often species that we could envisage as being useful building blocks ready for further reaction or functionalization. For example, Hänssgen reported the preparation of the planar 4-membered heterocycle [(tBu2SnPH)2] from tBu2SnCl2 and NaPH2 (Scheme 14a).90 Driess has used a dehydrocoupling-type reaction to prepare a dihydrophosphido-aluminium compound [(iBu2AlPH2)3] which also operates as an effective H2P– transfer agent, forming tris(phosphane) or tetrakis(phosphaneyl)silane/germane products from the trichlorosilane or tetrachlorosilane/germane precursor (Scheme 14b).91 Scheer has undertaken salt metathesis reactions of NaPH2 with IPrGaHCl2 (8) and the Al analogue (8′) to generate the corresponding bis(dihydrophosphide) complexes (9/9′, Scheme 14c).92 Hassler undertook a study into hypersilyl substituted phosphanes and, as part of this investigation, employed PH3 or NaPH2 to prepare tris(trimethylsilyl)silyldihydrophosphide (10). This species can undergo deprotonation with KOtBu, forming (Me3Si)3SiPHK (11), which is remarkably stable at room temperature, and can undergo reductive coupling to generate a mixture of the meso- and rac-isomers (12, Scheme 14d). This reductive coupling step involves reaction with tBu2Hg or 1,2-dibromoethane; the latter indicates that the phosphide is not particularly nucleophilic in that a P–C bond is not formed between (Me3Si)3SiPHK and Br2(CH2)2.93 Again, this latter point is intriguing and could be further investigated.

Scheme 14. Various Main Group Bond Transformations Have Been Undertaken Using Metal Dihydrophosphides Including (a) the Formation of Sn–P Bonds; (b) Sn–PH2 and Ge–PH2 Compounds; (c) Al– and Ga–NHC Complexes Functionalized with PH2; (d) the Formation of Hypersilyl Substituted Phosphanes, Which Can Undergo Reductive Coupling, Forming 12.

The Ga complex is depicted as the POV-Ray image (CCDC 2035403), with all H atoms, except the Ga–H fragment, removed for clarity.

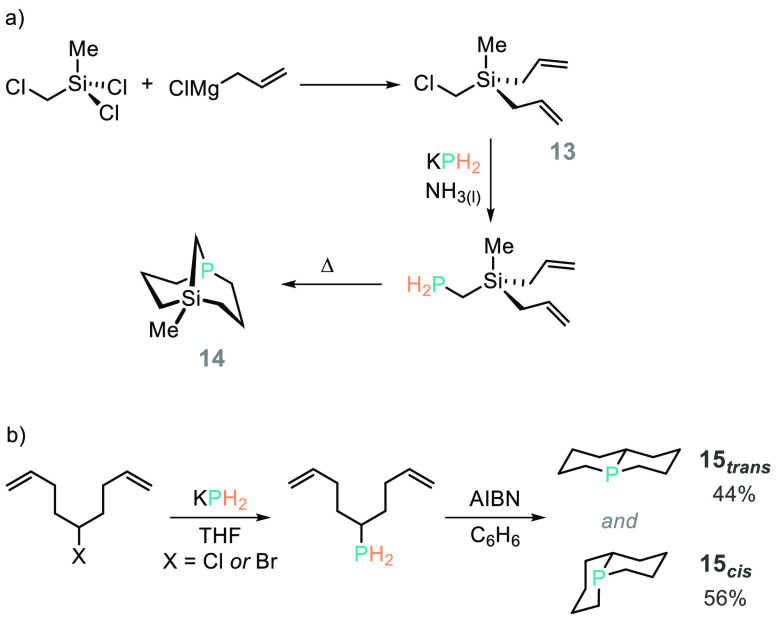

In 1982 Issleib reported on the use of KPH2 to form [3.3.1]-bicycle 14 by reaction with diallyl(chloromethyl)(methyl)silane (13) (Scheme 15a), and this type of protocol has since been used to access other phosphabicycles.94,95 A similar approach was taken to prepare a mixture of the cis- and trans-[4.4.0]-bicycle (15, Scheme 15b). These compounds were also complexed to Ni(CO)4, and the resulting LcisNi(CO)3 and LtransNi(CO)3 have similar Tolman Electronic Parameters (2063 and 2062 cm–1 respectively), which are very close to the σ-donor-only properties of PMe3 (2064 cm–1).96 Both reports indicate that interesting, unique phosphorus architectures can be prepared in a controlled way using PH3 derivatives.

Scheme 15. Issleib Has Used KPH2 To Install C–PH2 Bonds, Which Can Then Undergo Hydrophosphination To Generate Highly Unusual Bicycles.

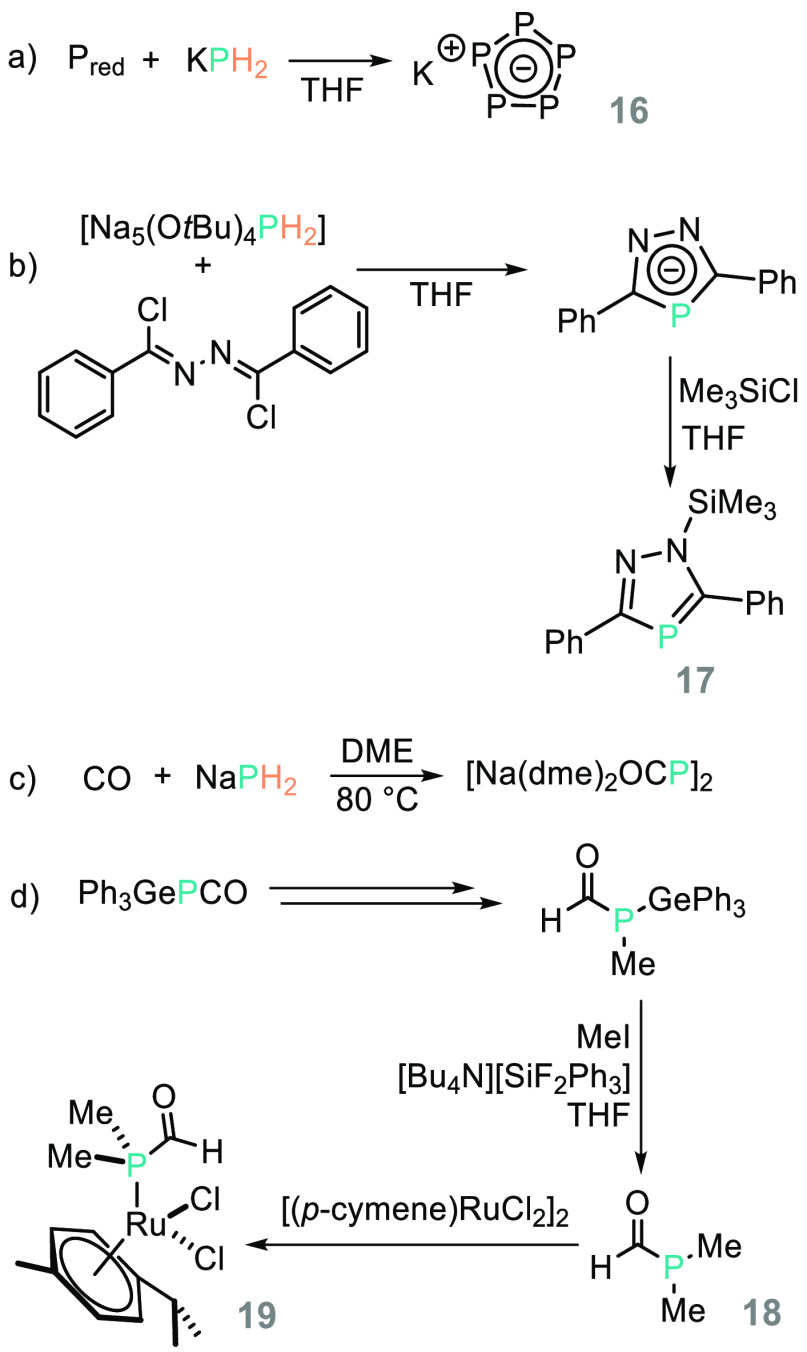

Baulder employed KPH2 in the degradation of red phosphorus to access the P5 anion, pentaphosphacyclopentadienide (the all-P analogue of the cyclopentadienyl anion) (16, Scheme 16a). With purification only requiring filtration and removal of PH3 gas, this offers an attractive alternative to the fractional crystallization previously reported for the synthesis from P4.97 Further to this example, use of NaPH2 (or Lewis base adduct analogues) is mostly limited to main group bond transformations. For example, Grützmacher reacted [Na5(OtBu)4PH2] with 1,2-bis(chloro(phenyl)methylene)hydrazine to prepare a 1,2,4-diazaphospholide (17, Scheme 16b);89 the group also prepared the heavy isocyanate Na(OCP), sodium phosphaethynolate, from reaction of NaPH2 with CO (Scheme 16c).98 The onward reactivity of Na(OCP) (and Lewis base/solvent adducts) has been studied by Grüztmacher in terms of probing nucleophility in the presence of group 14 compounds,99 while Stephan has employed Gütztmacher’s germanium compound, Ph3GePCO, to prepare the phosphorus-containing analogue of N,N-dimethylformamide (18), which can undergo coordination chemistry with ruthenium forming 19 (Scheme 16d).100

Scheme 16. (a) An Improved Synthesis of Pentaphosphacyclopentadienide Was Achieved Using KPH2 in the Presence of Red Phosphorus; (b) Grützmacher and Co-workers Use Na5(OtBu)4PH2 as a H2P– Source to Prepare Elaborate Heterocycles; (c) Grützmacher’s Seminal Report on the Preparation of the Dme Adduct of NaOCP, Which Has Been Used to Great Effect in Main Group Synthesis (vide infra); (d) Stephan and Co-workers Prepare the Heavy Element Analogue of DMF and Demonstrate Elegant Coordination Chemistry of This Species.

7.2. Reactions of MPH2 with Carbonyl-Containing Compounds

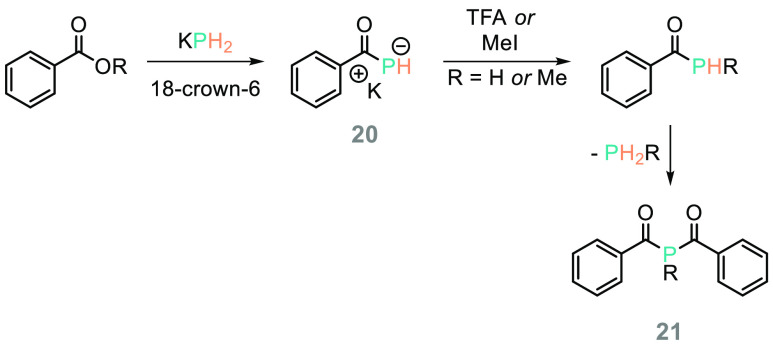

An early report on potential applications in organic synthesis was provided by Liotta.101 Reaction of aryl or alkyl benzoates with KPH2 in the presence of a catalytic amount of 18-crown-6 (10 mol %) generates potassium benzoyl phosphide (20, Scheme 17). This can undergo protonation with acid (trifluoroacetic acid, TFA) or methylation with MeI, but in both cases the products are unstable and decompose to generate dibenzoylphosphines (21). As we might expect, based simply on atomic size, the authors note no partial double character due to P atom lone pair/carbonyl π-orbital overlap (as we normally see with amides); if decomposition pathways can be controlled it may be possible to develop useful chemistry that diverges from that of amides.

Scheme 17. One of the Earliest Examples of Reactions of Carbonyl Compounds with KPH2 Was Presented by Liotta and Co-workers.

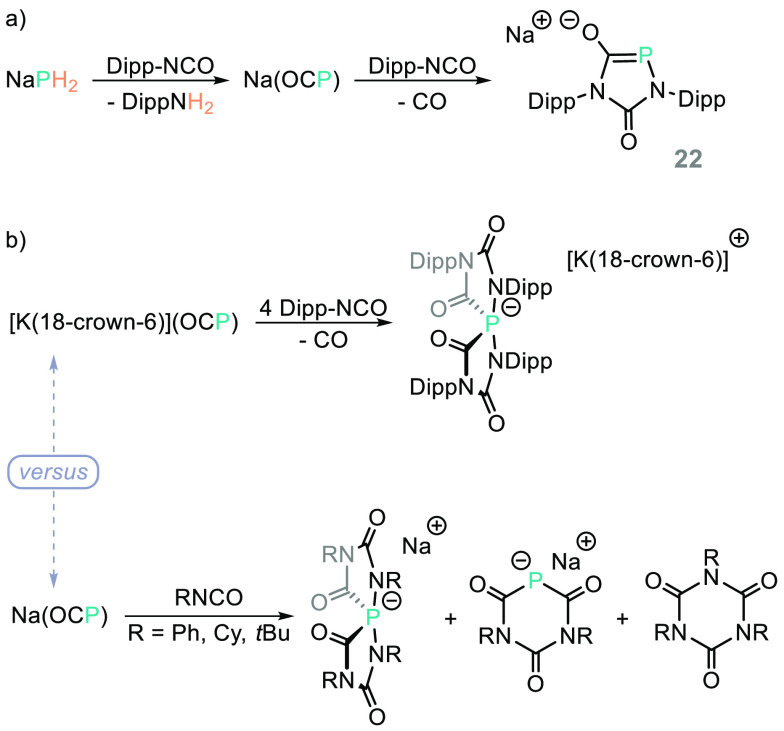

Goicoechea has reported the synthesis of Na(OCP) from the reaction of NaPH2 with isocyanate Dipp-NCO (though notably the syntheses of Na(OCP) have been reported from NaPH2 directly and PH3 as a feedstock).102 Na(OCP) goes on to react with isocyanates, generating structurally interesting main group compounds such as 22 (Scheme 18a).103 Interestingly, use of the potassium analogue, [K(18-crown-6)(OCP)], gives a different product distribution compared to that obtained using Na(OCP) (Scheme 18b), while the products obtained using Na(OCP) vary based on the substituents on the isocyanate (compare Scheme 18a and 18b, bottom),104 hinting at the diversity of synthesis that could be achieved if these reagents were more widely studied.

Scheme 18. Reagent and Substrate-Dependent Activity Is Observed When Reacting Na(OCP) or [K(18-crown-6)](OCP) with Different Isocyanates.

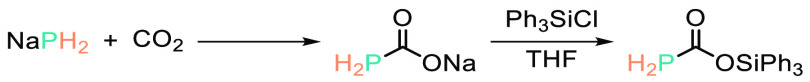

Analogous to the work of Liotta on esters,101 reaction of NaPH2 with CO2 gives a phosphine carboxylate, which can then undergo onward reaction with silyl chlorides to form phosphine carboxylate silylesters (Scheme 19).105 Goicoechea has also shown that NaPH2 can react with dimethyl cyanocarbonimidate in one step to form the heteroallene anion species 23, or in a stepwise fashion via the (carboximidate)phosphide 24 (Scheme 20). 24 can undergo reaction with Ph3GeCl to form a dimeric species product.106

Scheme 19. Goicoechea and Co-workers Prepare Silylesters from NaPH2 and CO.

Scheme 20. Goicoechea and Co-workers Demonstrate a Versatile Range of Main Group Transformations Using NaPH2.

[Na(18-crown-6)]+ omitted for clarity.

Many of the reactions discussed thus far are rooted in fundamental research, and therefore for many of the reactions that could be termed transformations of main group species, it may be difficult to envisage the relevance of these compounds to the organophosphorus, organic chemistry or applied chemistry communities. While these main group compounds are often challenging to prepare and handle, organic transformations of carboxylic acids and allenes are well-known: we have yet to discover if the aforementioned phosphorus-containing species undergo the same transformations, e.g. allenes undergoing a rich array of addition and cyclization reactions.107

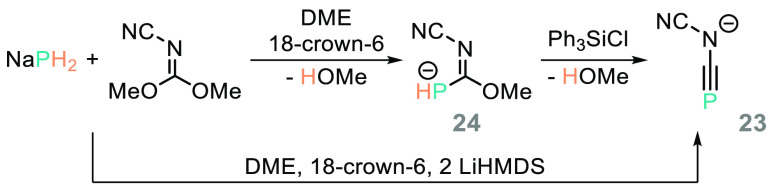

Gudat prepared a series of diazaboroles, including the PH2 species (26) from KPH2 and the bromodiazaborole precursor (25, Scheme 21a). The computational component of this study notes the covalent nature of the P–B σ-bond, along with the potential for these main group compounds to act as P-donor ligands.108 This ligand system has been incorporated into a scandium β-diketiminate complex,109 which can act as a phosphinidene transfer agent (Scheme 21b) similar to those already reported using a bulky 2,4,6-tBu-phenyl phosphinidene Zr110 or Th111 complex, which operate in a stoichiometric fashion (akin to that possible with Tebbe’s reagent112).

Scheme 21. (a) Gudat and Co-workers Prepared and Studied the Electronic Properties of Phosphino-Diazaboroles, While (b) Chen, Maron and Co-workers Employed the System in Coordination Chemistry.

Dibenzo-18-crown-6 abbreviated for clarity (dibenzo-18-c-6). The Sc complex is depicted as the POV-Ray image (CCDC 2048477), with all iso-propyl groups and H atoms removed for clarity.

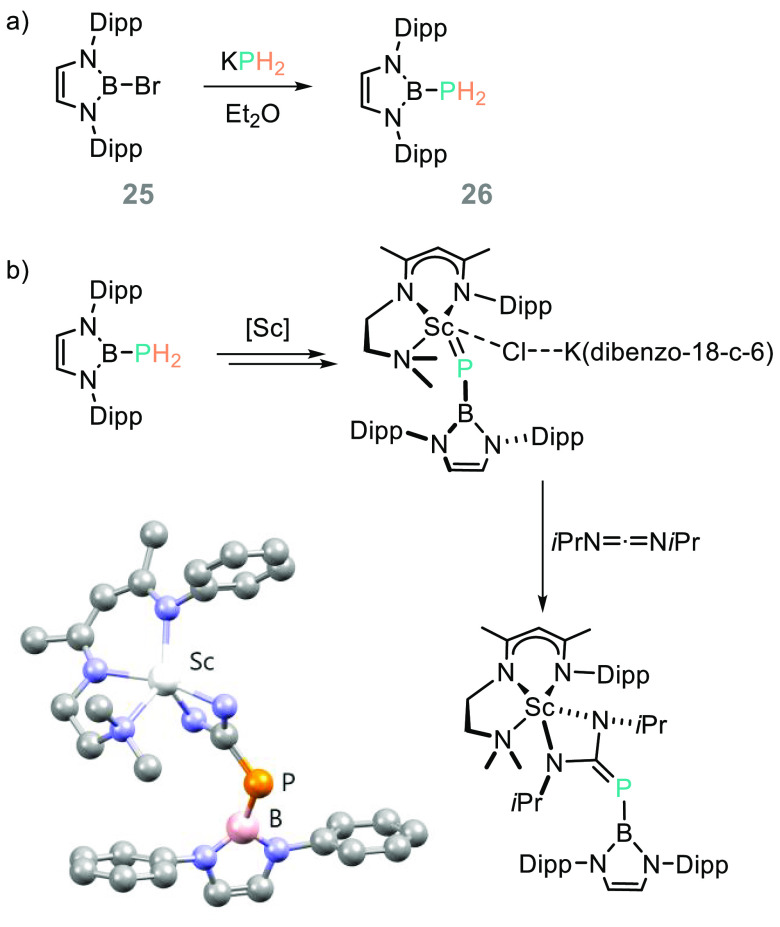

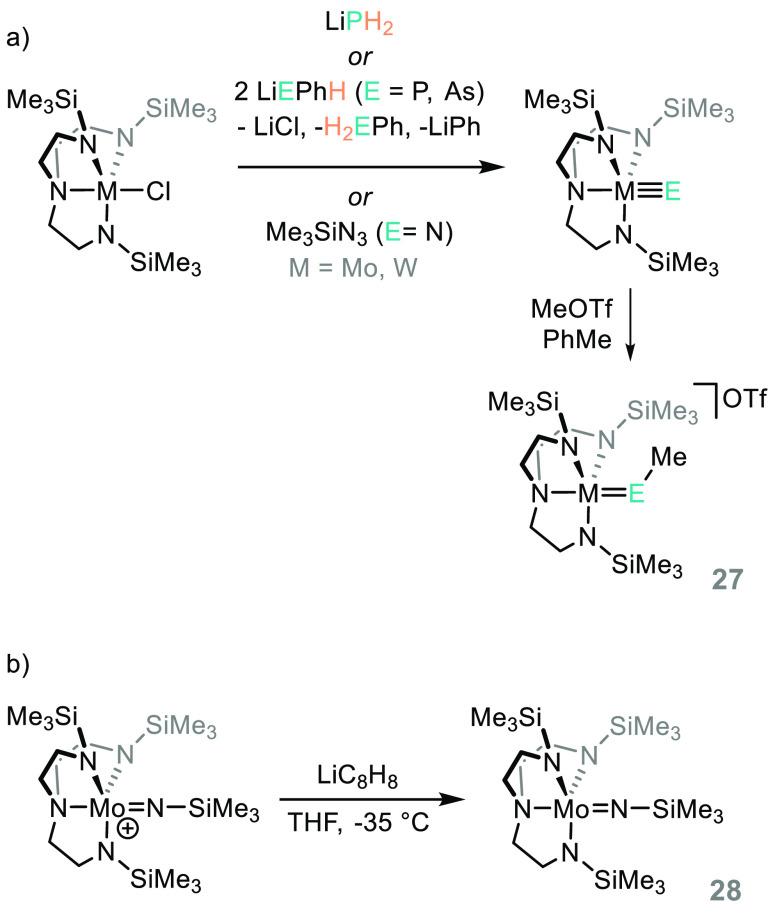

7.3. Reactions of MPH2 with Compounds of the d- and f-Block

Using a triamidoamine ligand, but one that is less bulky than that used to activate N2,113 Schrock was able to demonstrate the reactivity of a homologous series of Mo and W amido, phosphide, and arsenido complexes, employing LiPH2 or LiEPhH (E = P, As) or trimethylsilylazide (TMSN3) to install the M≡E bond (Scheme 22a).114 Their onward reaction with MeOTf to form the imido, phosphinidene, and arsinidene complexes (27) was studied, and the authors note that the Mo-phosphinidine complex decomposes in solution at room temperature whereas the W analogue does not. Similarly, the Mo arsinidine triflate was very unstable and could not undergo elemental analysis. The amido complex undergoes reduction in the presence of LiC8H8 to generate the Mo(V) product (28, Scheme 22b). This chemistry is important, because of not only the analogies we can draw between phosphorus and carbon but also the wealth of chemistry undertaken on the activation and functionalization of metal nitrido complexes, in particular their conversion to amines.115−118

Scheme 22. Schrock and Co-workers Have Undertaken a Systematic Study on the Coordination Chemistry of Molybdenum and Tungsten Amides, Phosphides, and Arsenides.

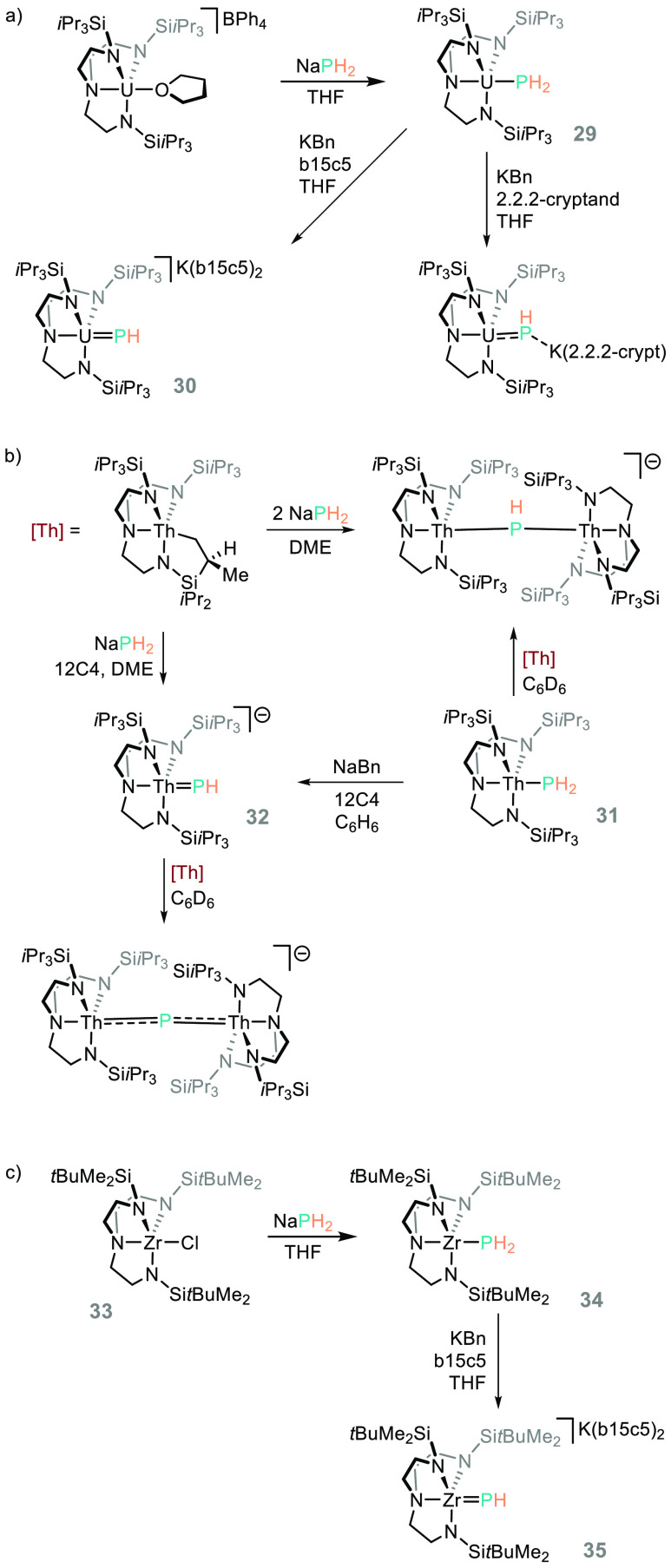

If we consider the importance of metal–carbon double bonds in catalysis, e.g. in catalytic metathesis reactions, and the allegory between P and C, then it is vital that fundamental studies into bonding and reactivity of metal–P multiply bonded species are undertaken. In this regard, NaPH2 has been used by Liddle to generate uranium and thorium phosphanide (29/31) and phosphinidene (30/32) complexes (Scheme 23a and 23b).119,120 Liddle also presented a follow-up paper on the analogous Zr complex (33), which reacts in a similar way to the uranium and thorium analogues (forming the respective phosphanide and phosphinidene compounds, 34 and 35, Scheme 23c).121 We can draw links to possible onward organic transformations by looking at the insertion chemistry reported by Stephan,110 Walter,111 and Walensky, where benzophenone was shown to insert into the Th–P bond of a bulkier mesityl analogue,122 and from the work of Mindiola on Ti-phosphinidene complexes and their hydrophosphination reactivity, although these species do require kinetic stabilization by use of a bulky organophosphine reagent.123

Scheme 23. (a, b) Liddle’s Studies on the Phosphanide and Phosphinidene Chemistry of the Actinides; (c) Studies on the Analogous Zr Complex.

Na(12c4)2 cations omitted for clarity, and 12-crown-4 (12c4) and benzo-15-crown-5 abbreviated for clarity (b15c5).

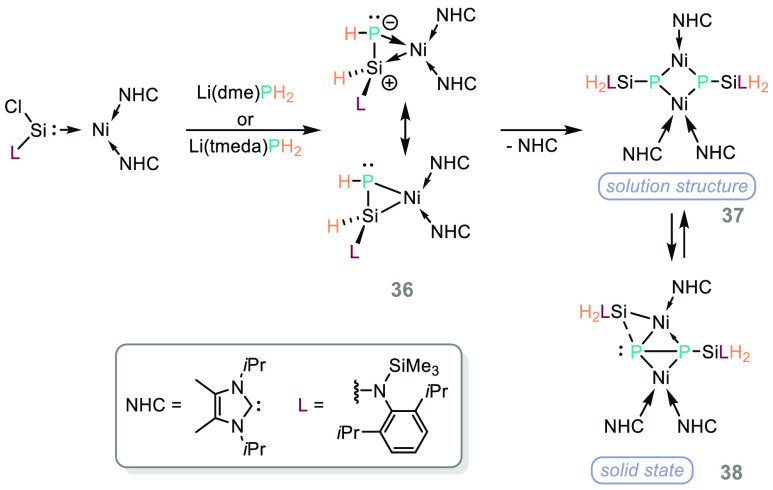

Driess has further elaborated the silylene chemistry of PH358 by taking a nickel-silylene species and demonstrating the coordination chemistry of PH2 (derived from Li(dme)PH2 or Li(tmeda)PH2), generating 36 (Scheme 24) and subsequent isomerization chemistry of the η2-species to generate 37/38.124

Scheme 24. Driess and Co-workers Demonstrate the Versatility of Silylene Chemistry in Concert with Nickel NHCs.

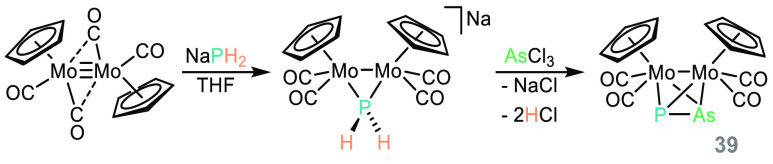

Finally, Scheer has also employed NaPH2 to generate a Mo dimer with a mixed P/As bridge (39, Scheme 25).125 A fundamental study, but one where we can envisage links to higher order main group polymer chains126 with unique properties.

Scheme 25. Scheer and Co-workers Prepare Mixed Group 15 Molybdenum Complexes Using NaPH2 (or LiE(SiMe3)2/KE(SiMe3)2, where E = P, As, Sb, Bi).

8. Conclusions and Outlook

The utilization of PH3 in synthesis is undoubtedly an untapped well, and this is understandable owing to the significant challenges in manipulating pressurized cylinders of such a hazardous gas. However, the recent reports of in situ PH3 generation offer a much safer alternative to its traditional manipulation. These new operationally simple methods have the potential to revolutionize phosphorus research (which is itself prevalent across a wide range of disciplines). More readily accessible PH3 sources will also provide easier access to MPH2 species (where M is an alkali metal), which are already experiencing a renaissance and are proving vital to access novel phosphorus-containing species (vide supra).

Considerable efforts have gone into the functionalization of P4 and PCl3, and adding PH3 to the list of readily accessible phosphorus starting materials will grant access to a rich vein of research. The prospect of catalytically activating PH3 to access useful phosphorus reagents is exciting, and with reports of M=PH and M–PH2 species, this endeavor feels more attainable than ever. The question remains: how to take M=PH, M–PH2 and undertake transformations of these species that go beyond hydrophosphination chemistry reported in the 1980s and 1990s?

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC and the Leverhulme Trust for financial support.

Author Contributions

‡ T.M.H. and S.L. contributed equally.

Funding awarded by the EPSRC (SL, RLW) and The Leverhulme Trust (TMH, RLW).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Hogue C.Governments are slow to put in place the policies we need for adaptation to climate change. In Chem. Eng. News; American Chemical Society: 2020; Vol. 98, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ijjasz-Vasquez E. J.; Saghir J.; Noble I.. State and Trends in Adaptation Report 2021: Africa; Global Center on Adaptation, 2021. https://gca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/GCA_STA_2021_Complete_website.pdf (accessed 2022-08-18).

- Palermo A.Future of the Chemical Sciences. https://www.rsc.org/globalassets/04-campaigning-outreach/campaigning/future-chemical-sciences/future-of-the-chemical-science-report-royal-society-of-chemistry.pdf. (accessed 2022-08-15).

- National Research Council, Beyond the Molecular Frontier: Challenges for Chemistry and Chemical Engineering.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2003; p 238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability Towards a Toxic-Free Environment; European Commission, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/chemicals/2020/10/Strategy.pdf (accessed 2022-08-18).

- Fluck E.; The chemistry of phosphine. In Topics in Current Chemistry: Inorganic Chemistry, 1st ed.; Springer-Verlag Berlin: Heidelberg, 1973; pp 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Klanberg F.; Muetterties E. L. Transition metal π-complexes of phosphine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 3296–3297. 10.1021/ja01014a090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E. O.; Louis E.; Kreiter C. G. cis-Tricarbonyltris(phosphine)chromium(0). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1969, 8, 377–378. 10.1002/anie.196903771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenberger L. J.; Klabunde U.; Schunn R. A. Group VI metal carbonyl phosphine complexes. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange and the crystal structure of cis-tetracarbonyldiphosphinechromium(0). Inorg. Chem. 1973, 12, 1143–1148. 10.1021/ic50123a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schunn R. A. Reaction of phosphine with some transition metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1973, 12, 1573–1579. 10.1021/ic50125a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebsworth E. A. V.; Mayo R. Novel Aspects of the Coordination Chemistry of Phosphane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1985, 24, 68–70. 10.1002/anie.198500681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebsworth E. A. V.; Gould R. O.; Mayo R. A.; Walkinshaw M. Reactions of phosphine, arsine, and stibine with carbonylbis(triethylphosphine)iridium(I) halides. Part 1. Reactions in toluene; X-ray crystal structures of [Ir(CO)ClH(PEt3)2(AsH2)] and [Ir(CO)XH(PEt3)2(μ-ZH2)RuCl2(η6-MeC6H4CHMe2-p)](X = Br, Z = P; X = Cl, Z = As). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1987, 2831–2838. 10.1039/DT9870002831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebsworth E. A. V.; Mayo R. A. Reactions of phosphine, arsine, and stibine with carbonylbis(triethylphosphine)iridium(I) halides. Part 2. Reactions in dichloromethane. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1988, 477–484. 10.1039/dt9880000477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Bohle D.; Clark G. R.; Rickard C. E. F.; Roper W. R.; Taylor M. J. Phosphine (PH3) complexes of ruthenium, osmium and iridium as precursors of terminal phosphido (PH2) complexes and the crystal structure of [Os(μ2-PH2) Cl(CO) (PPh3)2]2 · (C2H2Cl4)4. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988, 348, 385–409. 10.1016/0022-328X(88)80421-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conkie A.; Ebsworth E. A. V.; Mayo R. A.; Moreton S. Reactions of phosphine with carbonylbis(triethylphosphine)-rhodium(I) halides and derivatives. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1992, 2951–2954. 10.1039/dt9920002951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. W.; Yang X.; Jones R. A. Syntheses and structures of the tetra-phosphine complexes trans-MCl2(PH3)4 (M = Ru, Os). Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 6168–6170. 10.1039/c0cc01231a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Marsh S.; Crowte R. J.; Edwards P. G. New zirconium phosphido complexes and their reactions with alkenes. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1992, 699–700. 10.1039/c39920000699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/phosphine.pdf (accessed 2022-08-15).

- https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/registration/fs_PC-066500_01-Dec-99.pdf (accessed 2022-08-15).

- Full data for both ACGIH/NIOSH time-weighted average limit and short-term exposure limit for CO and HCN are not published.

- Ballantyne B. The influence of exposure route and species on the acute lethal toxicity and tissue concentrations of cyanide. Dev. Toxicol. Environ. Sci. 1983, 11, 583–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council Subcommittee on Acute Exposure Guideline, L. In Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals: Vol. 2; National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2002 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.: Washington (DC), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Corbridge D. E. C.Phosphorus An Outline of its Chemistry, Biochemistry and Uses, 5th ed.; Elsevier: The Netherlands, 1995; p 1208. [Google Scholar]

- Yakhvarov D. G.; Gorbachuk E. V.; Sinyashin O. G. Electrode Reactions of Elemental (White) Phosphorus and Phosphane PH3. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 4709–4726. 10.1002/ejic.201300845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. J. Recent Breakthroughs in P4 Chemistry: Towards Practical, Direct Transformations into P1 Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205019 10.1002/anie.202205019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger J.; Engels C. Ueber die Entwicklung von gasförmigem Phosphorwasserstoff und dessen Einwirkung auf Aldehyde und Ketonsäuren. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1888, 21, 326–336. 10.1002/cber.18880210158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseev D. V.; James B. R. Tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)phosphonium salts: Their properties, hazards and toxicities. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2020, 195, 263–279. 10.1080/10426507.2019.1686379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles A. R.; Rust F. F.; Vaughan W. E. The Preparation of Organo-phosphines by the Addition of Phosphine to Unsaturated Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 3282–3284. 10.1021/ja01133a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut M. M.; Hechenbleikner I.; Currier H. A.; Schaefer F. C.; Wystrach V. P. The Cyanoethylation of Phosphine and Phenylphosphine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 1103–1107. 10.1021/ja01514a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut M. M.; Currier H. A.; Semsel A. M.; Wystrach V. P. The Free Radical Addition of Phosphines to Unsaturated Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1961, 26, 5138–5145. 10.1021/jo01070a087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cristina Silva Costa D. Additions to non-activated alkenes: Recent advances. Arabian J. Chem. 2020, 13, 799–834. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malysheva S. F.; Gusarova N. K.; Belogorlova N. A.; Sutyrina A. O.; Albanov A. I.; Sukhov B. G.; Kuimov V. A.; Litvintsev Y. I.; Trofimov B. A. Phosphorus halide free synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisophosphinoline 2-oxides. Mendeleev Commun. 2018, 28, 29–30. 10.1016/j.mencom.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov P. A.; Petrushenko K. B.; Ivanova N. I.; Khrapova K. O.; Larina L. I.; Gusarova N. K.; Trofimov B. A. Oxidative coupling of hydroxy- or aminoazobenzenes with secondary phosphine chalcogenides: Towards new media-responsive molecular switches. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 1992–1995. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.04.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman R.; Berven B. M.; Chris Corkery T.; Nie H.-Y.; Idacavage M.; Gillies E. R.; Ragogna P. J. Fluorinated polymerizable phosphonium salts from PH3: Surface properties of photopolymerized films. J. Polym. Sci., Part A-1: Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 2782–2792. 10.1002/pola.26692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajirahimkhan S.; Chapple D. E.; Gholami G.; Blacquiere J. M.; Xu C.; Ragogna P. J. Lignophines”: lignin-based tertiary phosphines with metal-scavenging ability. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10357–10360. 10.1039/D0CC03636F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kischkel H.; Röschenthaler G.-V. Reaktionen von Phosphanen MenPH3-n (n = 0—3) mit Hexafluorisopropylidenimin/Reactions of the Phosphanes MenPH3-n (n = 0—3) with Hexafluorisopropylidenimine. Z. Naturforsch. B 1984, 39, 356–358. 10.1515/znb-1984-0314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison K. N.; Hoye P. A. T.; Orpen A. G.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B. Water soluble, zero-valent, platinum-, palladium-, and nickel-P(CH2OH)3 complexes:catalysts for the addition of PH3 to CH2O. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989, 1096–1097. 10.1039/C39890001096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. W.; Harrison K. N.; Hoye P. A. T.; Orpen A. G.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B. Water-soluble tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine complexes with nickel, palladium, and platinum. Crystal structure of [Pd{P(CH2OH)3}4]·CH3. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3026–3033. 10.1021/ic00040a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoye P. A. T.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B.; Worboys K. Hydrophosphination of formaldehyde catalysed by tris-(hydroxymethyl)phosphine complexes of platinum, palladium or nickel. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1993, 269–274. 10.1039/dt9930000269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E. G.; Pringle P.; Worboys K. Chemoselective platinum(0)-catalysed hydrophosphination of ethyl acrylate. Chem. Commun. 1998, 49–50. 10.1039/a706718f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B. Platinum(0)-catalysed hydrophosphination of acrylonitrile. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1990, 1701–1702. 10.1039/c39900001701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E. G.; Pringle P. B.; Smith M.; Worboys K. Self-replication of tris(cyanoethyl)phosphine catalysed by platinum group metal complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997, 4277–4282. 10.1039/a704655c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapshin I. V.; Basalov I. V.; Lyssenko K. A.; Cherkasov A. V.; Trifonov A. A. CaII, YbII and SmII Bis(Amido) Complexes Coordinated by NHC Ligands: Efficient Catalysts for Highly Regio- and Chemoselective Consecutive Hydrophosphinations with PH3. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd O.; Hoff D.; Kottsieper K. W.; Liek C.; Wenz K.; Stelzer O.; Sheldrick W. S. Water-Soluble Phosphines. 17.1 Novel Water-Soluble Secondary and Tertiary Phosphines with Disulfonated 1,1‘-Biphenyl Backbones and Dibenzophosphole Moieties. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 5034–5042. 10.1021/ic011239z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhans K. P.; Stelzer O.; Svara J.; Weferling N. Synthese primärer und sekundärer Phosphane durch selektive Alkylierung von PH3 unter Phasentransferbedingungen/Synthesis of Primary and Secondary Phosphines by Selective Alkylation of PH3 under Phase Transfer Conditions. Z. Naturforsch. B 1990, 45, 203–211. 10.1515/znb-1990-0215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterer F.; Herd O.; Kühnel M.; Stelzer O.; Weferling N.; Sheldrick W. S.; Hahn J.; Nagel S.; Rösch N. PH-Functional Phosphines with 1,1‘-Biphenyl-2,2‘-bis(methylene) and 1,1‘-Binaphthyl-2,2‘-bis(methylene) Backbones. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 6408–6417. 10.1021/ic980346z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimbetova G. S.; Borangazieva A. K. Oxidizing Alkoxylation of Phosphine in Alcoholic Solutions of Iodine. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2001, 74, 2079–2082. 10.1023/A:1015555109676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer D. J.; Fischer J.; Kucken S.; Langhans K. P.; Stelzer O.; Weferling N. Wasserlösliche Phosphane, III [1]. Wasserlösliche primäre Phosphane mit Ammoniumgruppierungen NR2R’ in der Seitenkette -donorfunktionalisierte Amphiphile/Water-Soluble Phosphanes, III [1]. Water-Soluble Primary Phosphanes with Ammonium Groups NR2R’ in the Side Chain -Donor-Functionalized Amphiphiles. Z. Naturforsch. B 1994, 49, 1511–1524. 10.1515/znb-1994-1111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polimbetova G. S.; Borangazieva A. K.; Ibraimova Z. U.; Bugubaeva G. O.; Keynbay S. Oxidative alkoxylation of phosphine in alcohol solutions of copper halides. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 90, 1539–1544. 10.1134/S0036024416080227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polimbetova G. S.; Mukhitdinova B. A.; Ergozhin E. E.; Borangazieva A. K.; Khakimbolatova K. K.; Tasmagambet A.; Dauletkulova N. T.; Ibraimova Z. U. Oxidation of phosphine with quinone and quinoid redox polymers in alcohol solutions of copper. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 91, 2344–2349. 10.1134/S0036024417120238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley A. H.; Harris P. R.; Jones R. A.; Nunn C. M. III/V Precursors with phosphorus- or arsenic-hydrogen bonds. A low-temperature route to gallium arsenide and gallium phosphide. Organometallics 1991, 10, 652–656. 10.1021/om00049a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bispinghoff M.; Tondreau A. M.; Grützmacher H.; Faradji C. A.; Pringle P. G. Carbene insertion into a P-H bond: parent phosphinidene-carbene adducts from PH3 and bis(phosphinidene)mercury complexes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 5999–6003. 10.1039/C5DT01741F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.; Ellis B. D.; Wang X.; Power P. P. Diarylstannylene Activation of Hydrogen or Ammonia with Arene Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12268–12269. 10.1021/ja805358u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.; Guo J.-D.; Ellis B. D.; Zhu Z.; Fettinger J. C.; Nagase S.; Power P. P. Reaction of Hydrogen or Ammonia with Unsaturated Germanium or Tin Molecules under Ambient Conditions: Oxidative Addition versus Arene Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16272–16282. 10.1021/ja9068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Interaction of Multiple Bonded and Unsaturated Heavier Main Group Compounds with Hydrogen, Ammonia, Olefins, and Related Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 627–637. 10.1021/ar2000875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Reactions of heavier main-group compounds with hydrogen, ammonia, ethylene and related small molecules. Chem. Rec. 2012, 12, 238–255. 10.1002/tcr.201100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube J. W.; Brown Z. D.; Caputo C. A.; Power P. P.; Ragogna P. J. Activation of gaseous PH3 with low coordinate diaryltetrylene compounds. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1944–1946. 10.1039/C3CC48933G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Präsang C.; Stoelzel M.; Inoue S.; Meltzer A.; Driess M. Metal-Free Activation of EH3 (E = P, As) by an Ylide-like Silylene and Formation of a Donor-Stabilized Arsasilene with a HSi-AsH Subunit. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 10002–10005. 10.1002/anie.201005903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C.; Schwabedissen J.; Neumann B.; Stammler H.-G.; Mitzel N. W. Frustrated Lewis pair chemistry of hydride sponges. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 6547–6564. 10.1039/D2DT00585A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W.; Erker G. Frustrated Lewis Pairs: Metal-free Hydrogen Activation and More. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 46–76. 10.1002/anie.200903708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel P.; Karaghiosoff K.; Manolikakes S. In Frustrated Lewis Pairs II: Expanding the Scope, Erker G., Stephan D. W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Frustrated Lewis Pairs: From Concept to Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 306–316. 10.1021/ar500375j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Catalysis, FLPs, and Beyond. Chem. 2020, 6, 1520–1526. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Klankermayer J. In Frustrated Lewis Pairs II: Expanding the Scope; Erker G., Stephan D. W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W.; Erker G. In Frustrated Lewis Pairs I: Uncovering and Understanding; Erker G., Stephan D. W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Weferling N. Production of Organophosphorus Compounds from Hydrogen Phosphide. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1987, 30, 641–644. 10.1080/03086648708079146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner L.; Beck P.; Hoffmann H. Phosphororganische Verbindungen, XIX. Reduktion von Phosphorverbindungen mit Alkalimetallen. Chem. Ber. 1959, 92, 2088–2094. 10.1002/cber.19590920920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceppatelli M.; Scelta D.; Serrano-Ruiz M.; Dziubek K.; Garbarino G.; Jacobs J.; Mezouar M.; Bini R.; Peruzzini M. High pressure synthesis of phosphine from the elements and the discovery of the missing (PH3)2H2 tile. Nature Commun. 2020, 11, 6125. 10.1038/s41467-020-19745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale S. D.; Jolly W. L.; Thomas S.; Britton D. Phosphine. Inorg. Synth. 1967, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Semenzin D.; Etemad-Moghadam G.; Albouy D.; Koenig M. Alkylation of phosphine PH3 generated from red phosphorus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3297–3300. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)76889-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trofimov B. A.; Brandsma L.; Arbuzova S. N.; Malysheva S. F.; Gusarova N. K. Nucleophilic addition of phosphine to aryl- and hetarylethenes a convenient synthesis of bis(2-arylalkyl)- and bis(2-hetaralkyl)phosphines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 7647–7650. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78365-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price correct as of July 2022.

- Dorfman Y. A.; Levina L. V. New reaction involving oxidative C-phosphorylation of pyridine by phosphine. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1992, 28, 111–112. 10.1007/BF00529495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber T.; Argent S. P.; Ball L. T. Expanding Ligand Space: Preparation, Characterization, and Synthetic Applications of Air-Stable, Odorless Di-tert-alkylphosphine Surrogates. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5454–5461. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfelder R.; Streitferdt V.; Lennert U.; Cammarata J.; Scott D. J.; Zeitler K.; Gschwind R. M.; Wolf R. Photocatalytic Arylation of P4 and PH3: Reaction Development Through Mechanistic Insight. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 24650–24658. 10.1002/anie.202110619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley Downie T. M.; Mahon M. F.; Lowe J. P.; Bailey R. M.; Liptrot D. J. A Copper(I) Platform for One-Pot P-H Bond Formation and Hydrophosphination of Heterocumulenes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 8214–8219. 10.1021/acscatal.2c02199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joannis A. Action du phosphure d’hydrogène sur le potassammonium et le sodammonium. C. R. Acad. Sci. 1894, 119, 558–561. [Google Scholar]

- Joannis A. Action du phosphure d’hydrogène sur le potassammonium. Ann. Chim. Phys. 1906, 7, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Legoux C. Sur un phosphure de lithium. C. R. Acad. Sci. 1938, 207, 634–636. [Google Scholar]

- Legoux C. Sur la décomposition des phosphidures alcalins sous l’action de la chaleur. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1940, 7, 545–549. [Google Scholar]

- Albers H.; Schuler W. Über die Darstellung von Mononatriumphosphid und Mononatriumarsid mit Hilfe alkaliorganischer Verbindungen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1943, 76, 23–26. 10.1002/cber.19430760104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evers E. C.; Street E. H.; Jung S. L. The Alkali Metal Phosphides. II. Certain Chemical Properties of Tetrasodium Diphosphide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 5088–5091. 10.1021/ja01155a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll F.; Bergerhoff G. Kaliumdihydrogenphosphid, Eigenschaften und Reaktions-verhalten gegenüber Sauerstoff und Phosphor. Monatsh. Chem. 1966, 97, 808–819. 10.1007/BF00932752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer H.; Fritz G.; Hölderich W. Das LiPH2 ·1 Monoglym. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1977, 428, 222–224. 10.1002/zaac.19774280127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerhoff G.; Schultze-Rhonhof F. Uber die Kristallstrukturen des Kalium und Rubidiumsphosphids, KPH2 und RbPH2. Acta Crystallogr. 1962, 15, 420–420. 10.1107/S0365110X62000997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H.; Hassiepen K. M. Über die Dihydrogenphosphide der Alkalimetalle, MPH2 mit M ≙ Li, Na, K, Rb und Cs. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1985, 531, 108–118. 10.1002/zaac.19855311216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta C. L.; McLaughlin M. L.; Van Derveer D. G.; O’Brien B. A. The 2-H-isophosphindoline-1,3-dione ion: The phosphorus analogue of the phthalimide anion. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 1665–1668. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81139-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. C.; Johnson J. B.; Congdon D. J.; Nedrelow J. H.; O’Brien B. A. Alkali-Metal Phthaloylphosphides: Easily Prepared Phosphide Reagents for Coordination and Main-Group Chemistry. Organometallics 2001, 20, 1705–1708. 10.1021/om000949u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D.; Ott T.; Grützmacher H. Phosphorus Heterocycles from Sodium Dihydrogen Phosphide: Simple Synthesis and Structure of 3,5-Diphenyl-2,4-diazaphospholide. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 682–686. 10.1002/zaac.200900007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hänssgen D.; Aldenhoven H.; Nieger M. Ein neues PH-funktionelles Diphosphadistannetan: (tBu2SnPH)2. Chem. Ber. 1990, 123, 1837–1839. 10.1002/cber.19901230914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driess M.; Monsé C. Diisobutyl(phosphanyl)alan: ein einfaches PH2-Transferreagens zur Synthese von polyphosphanylierten Verbindungen des Siliciums und Germaniums. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2000, 626, 1091–1094. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhart M. A. K.; Seidl M.; Timoshkin A. Y.; Scheer M. NHC-stabilized Parent Arsanylalanes and -gallanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3806–3811. 10.1002/anie.202013849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappello V.; Baumgartner J.; Dransfeld A.; Hassler K. Monophosphanes and Diphosphanes with the Hypersilyl Substituent. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 2006, 4589–4599. 10.1002/ejic.200600444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne U.; Krech F.; Issleib K. 5-METHYL-1.5-PHOSPHA-SILABICYCLO[3.3.1]NONAN. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1982, 13, 153–156. 10.1080/03086648208081171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss B.; Mügge C.; Zschunke A.; Krech F.; Flock M. 1-Phosphabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2002, 628, 580–588. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krech F.; Issleib K.; Zschunke A.; Meyer H. Cis- und trans-1-Phosphabicyclo[4.4.0]decan. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1987, 553, 136–146. 10.1002/zaac.19875531016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baudler M.; Düster D.; Ouzounis D. Beiträge zur Chemie des Phosphors. 172. Existenz und Charakterisierung des Pentaphosphacyclopentadienid-Anions, P5–, des Tetraphosphacyclopentadienid-Ions, P4CH–, und des Triphosphacyclobutenid-Ions, P3CH2–. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1987, 544, 87–94. 10.1002/zaac.19875440108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puschmann F. F.; Stein D.; Heift D.; Hendriksen C.; Gal Z. A.; Grützmacher H.-F.; Grützmacher H. Phosphination of Carbon Monoxide: A Simple Synthesis of Sodium Phosphaethynolate (NaOCP). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8420–8423. 10.1002/anie.201102930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heift D.; Benkö Z.; Grützmacher H. Is the phosphaethynolate anion, (OCP)-, an ambident nucleophile? A spectroscopic and computational study. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 5920–5928. 10.1039/c3dt53569j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkop K. M.; Jupp A. R.; Stephan D. W. P,P-Dimethylformylphosphine: The Phosphorus Analogue of N,N-Dimethylformamide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12751–12755. 10.1021/jacs.8b09266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta C. L.; McLaughlin M. L.; O’Brien B. A. The synthesis and reactions of potassium benzoylphosphide, benzoylphosphine, and benzoylmethylphosphine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 1249–1252. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80125-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea J. M.; Grützmacher H. The Chemistry of the 2-Phosphaethynolate Anion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16968–16994. 10.1002/anie.201803888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heift D.; Benkö Z.; Grützmacher H.; Jupp A. R.; Goicoechea J. M. Cyclo-oligomerization of isocyanates with Na(PH2) or Na(OCP) as “P–” anion sources. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4017–4024. 10.1039/C5SC00963D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prepared from K3P7, 18-crown-6, CO, and DMF (reflux), as opposed to being derived directly from KPH2.

- Schreiber R. E.; Goicoechea J. M. Phosphine Carboxylate—Probing the Edge of Stability of a Carbon Dioxide Adduct with Dihydrogenphosphide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3759–3767. 10.1002/anie.202013914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergöçmen D.; Goicoechea J. M. Synthesis, Structure and Reactivity of a Cyapho-Cyanamide Salt. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25286–25289. 10.1002/anie.202111619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S. Electrophilic Addition and Cyclization Reactions of Allenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1679–1688. 10.1021/ar900153r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaz M.; Bender J.; Förster D.; Frey W.; Nieger M.; Gudat D. Phosphines with N-heterocyclic boranyl substituents. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 680–689. 10.1039/C3DT52441H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B.; Xiang L.; Carpentier A.; Maron L.; Leng X.; Chen Y. Scandium-Terminal Boronylphosphinidene Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2705–2709. 10.1021/jacs.1c00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen T. L.; Stephan D. W. Phosphinidene Transfer Reactions of the Terminal Phosphinidene Complex Cp2Zr(:PC6H2-2,4,6-t-Bu3)(PMe3). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11914–11921. 10.1021/ja00153a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Hou G.; Zi G.; Ding W.; Walter M. D. A Base-Free Terminal Actinide Phosphinidene Metallocene: Synthesis, Structure, Reactivity, and Computational Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14511–14525. 10.1021/jacs.8b09746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley R. C.; Li J.; Main C. A.; McKiernan G. J. Titanium carbenoid reagents for converting carbonyl groups into alkenes. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 4825–4864. 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yandulov D. V.; Schrock R. R. Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Science 2003, 301, 76–78. 10.1126/science.1085326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mösch-Zanetti N. C.; Schrock R. R.; Davis W. M.; Wanninger K.; Seidel S. W.; O’Donoghue M. B. Triamidoamine Complexes of Molybdenum and Tungsten That Contain Metal-E (E = N, P, and As) Single, Double, or Triple Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11037–11048. 10.1021/ja971727z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazari N. Homogeneous iron complexes for the conversion of dinitrogen into ammonia and hydrazine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4044–4056. 10.1039/b919680n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Loose F.; Chirik P. J. Beyond Ammonia: Nitrogen-Element Bond Forming Reactions with Coordinated Dinitrogen. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 5637–5681. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z.-J.; Wei J.; Zhang W.-X.; Chen P.; Deng D.; Shi Z.-J.; Xi Z. Direct transformation of dinitrogen: synthesis of N-containing organic compounds via N-C bond formation. Nat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1564–1583. 10.1093/nsr/nwaa142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masero F.; Perrin M. A.; Dey S.; Mougel V. Dinitrogen Fixation: Rationalizing Strategies Utilizing Molecular Complexes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3892–3928. 10.1002/chem.202003134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B. M.; Balázs G.; Scheer M.; Tuna F.; McInnes E. J. L.; McMaster J.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Liddle S. T. Triamidoamine-Uranium(IV)-Stabilized Terminal Parent Phosphide and Phosphinidene Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4484–4488. 10.1002/anie.201400798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildman E. P.; Balázs G.; Wooles A. J.; Scheer M.; Liddle S. T. Thorium-phosphorus triamidoamine complexes containing Th-P single- and multiple-bond interactions. Natture Commun. 2016, 7, 12884. 10.1038/ncomms12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford H.; Rookes T. M.; Wildman E. P.; Balázs G.; Wooles A. J.; Scheer M.; Liddle S. T. Terminal Parent Phosphanide and Phosphinidene Complexes of Zirconium(IV). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7669–7673. 10.1002/anie.201703870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova S. P.; Tarlton M. L.; Barnes C. L.; Walensky J. R. Double insertion of benzophenone into thorium-phosphorus bonds. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 857, 159–163. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2017.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basuli F.; Tomaszewski J.; Huffman J. C.; Mindiola D. J. Four-Coordinate Phosphinidene Complexes of Titanium Prepared by α-H-Migration: Phospha-Staudinger and Phosphaalkene-Insertion Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10170–10171. 10.1021/ja036559r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlington T. J.; Szilvási T.; Driess M. Versatile Tautomerization of EH2-Substituted Silylenes (E = N, P, As) in the Coordination Sphere of Nickel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3304–3314. 10.1021/jacs.9b00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dütsch L.; Riesinger C.; Balázs G.; Scheer M. Synthesis of Tetrahedranes Containing the Unique Bridging Hetero-Dipnictogen Ligand EE′ (E ≠ E′ = P, As, Sb, Bi). Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 8804–8810. 10.1002/chem.202100663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dütsch L.; Fleischmann M.; Welsch S.; Balázs G.; Kremer W.; Scheer M. Dicationic E4 Chains (E = P, As, Sb, Bi) Embedded in the Coordination Sphere of Transition Metals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3256–3261. 10.1002/anie.201712884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]