Highlights

-

•

Web-delivered interventions have the potential to help US Hispanic/Latinx smokers quit.

-

•

WebQuit (vs Smokefree) website was more engaging among US Hispanic/Latinx smokers.

-

•

WebQuit (vs Smokefree) website had higher quit rates among US Hispanic/Latinx smokers.

Abbreviations: ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; CI, 95% confidence interval; FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; IRR, Incidence Rate Ratio; LGB, lesbian, gay, or bisexual; OR, odds ratio; PE, point estimate; PPA, point-prevalence abstinence; RCT, randomized clinical trial; US, United States; USCPG, US Clinical Practice Guidelines

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy, Hispanic, Latino(a) or Latinx, Smokefree.gov, Smoking cessation, Web-based interventions, WebQuit.org

Abstract

Hispanic/Latinx adult smokers in the United States (US) face barriers to receiving and utilizing evidenced-based cessation treatments compared with other racial/ethnic groups. The lack of efficacious and accessible smoking cessation treatments for this population further contributes to such smoking disparities. In a secondary analysis, we explored the efficacy of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)-based website (WebQuit.org) versus a US Clinical Practice Guidelines (USCPG)-based website (Smokefree.gov) for smoking cessation in a subset of Hispanic/Latinx adult participants enrolled in the WebQuit trial. Of the 2,637 participants who were randomized in the parent trial, 222 were Hispanic/Latinx (n = 101 in WebQuit, n = 121 in Smokefree). Smoking cessation outcomes were measured at 3, 6, and 12-months. The primary outcome was self-reported complete-case 30-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at 12-months. Treatment engagement and satisfaction, change in acceptance of urges to smoke, and commitment to quitting smoking were compared across conditions. Retention rate was 88% at 12-months. WebQuit participants had higher odds of smoking cessation compared to Smokefree participants at 12-months (40% vs. 25%; OR = 1.93 95% CI: 1.04, 3.59). Findings were similar using multiple imputation. WebQuit participants engaged more with the website than Smokefree participants through multiple indicators of engagement, including spending more time using the website (IRR = 2.32; 95% CI: 1.68, 3.20). Although WebQuit participants engaged more with the website than Smokefree participants, there was no evidence that differences in quit rates were mediated by engagement level. This study provides initial empirical evidence that digital interventions may be efficacious for helping Hispanic/Latinx adults quit smoking.

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking is directly linked to the development of cancer, heart disease, and stroke, which are three of the five leading causes of death among Hispanic/Latinx adults in the United States (US). (Heron, 2018) Every year more than 43,000 Hispanic/Latinx adults are diagnosed with smoking-related cancer, with more than 18,000 dying from a smoking-related cancer. (Henley et al., 2016) Although there has been considerable progress made in reducing cigarette smoking, (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020) disparities in smoking rates and cessation outcomes persist among and within racial/ethnic groups, including Hispanic/Latinx populations. (Kaplan et al., 2021, Kaplan et al., 2014, Merzel et al., 2015, Babb et al., 2020) Relative to other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic/Latinx adults smoke at lower rates (9.8% vs. 13.7% general population) and are more likely to be non-daily smokers. (Creamer et al., 2019, Cornelius et al., 2017, Babb et al., 2017, Klugman et al., 2020, Weinberger et al., 2019) However, substantial disparities exist between the Hispanic/Latinx nationality subgroups living in the US. For example, Puerto Ricans have the second highest rate of cigarette smoking (28.5%) compared to any other racial/ethnic group, followed by their Cuban counterparts (19.8%). (Martell et al., 2016) In addition, Hispanic/Latinx smokers are more likely to make quit attempts but less likely to succeed in quitting than any other racial/ethnic group. (Trinidad et al., 2011) This issue is of public health concern, especially considering that Hispanic/Latinx comprise 19% of the US population. Further, Hispanics/Latinxs are a historically underserved and rapidly growing population that is expected to more than double by 2060. (Hispanic Population to reach 111 Million by 2060, 2018) Therefore, there is a need for efficacious and accessible smoking cessation treatments in this population.

Hispanic/Latinx smokers face major barriers to receiving and utilizing smoking cessation treatments. (Mai and Soulakova, 2018, Li et al., 2021) They are the least likely of any racial/ethnic group to have health insurance coverage for smoking cessation treatments, receive advice to quit, and participate in smoking cessation programs. (Cohen et al., 2021) Therefore, Hispanic/Latinx smokers often attempt to quit on their own without the aid of healthcare providers or medication. (Carter-Pokras et al., 2011) Furthermore, due to highly concentrated targeting of tobacco product placement and advertisement in racial/ethnic minority communities, Hispanic/Latinx neighborhoods have greater access to tobacco products. (Iglesias-Rios and Parascandola, 2013) This disproportionate product placement, in conjunction with a lack of evidenced-based healthcare access, is likely related to less success in quitting among Hispanic/Latinx smokers.

One avenue to better address smoking cessation among Hispanic/Latinx smokers may be to offer freely available smoking cessation services via digital-health technologies for smoking cessation (i.e., websites). Research indicates that about 85% of US Hispanic/Latinx adults use the internet, Pew Research Center (2021) suggesting there is a key opportunity to increase the reach of smoking cessation services via website-delivered interventions. Websites reach 12 million adult smokers who look online for smoking cessation help each year, at a low-cost. (Graham and Amato, 2019) In fact, smoking cessation websites have at least 21 times higher overall national reach as compared to telephone quitline interventions, (Borrelli et al., 2015) as well as 145% lower cost-per-quit than quitlines. (Jamal et al., 2018) Furthermore, websites do not require health insurance to be utilized, which would help circumvent the lack of access to health insurance among the Hispanic/Latinx population. (Mai and Soulakova, 2018, Li et al., 2021, Cohen et al., 2021).

The use of digital interventions with theory-based behavioral approaches may represent a key avenue to improve the odds of quitting among Hispanic/Latinx smokers. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is an emerging therapeutic approach for smoking cessation with the goal of fostering a willingness to tolerate potentially aversive experiences while promoting smoke-free days consistent with desired goals and values. (Hayes et al., 2013, McCallion and Zvolensky, 2015) ACT teaches (1) awareness of uncomfortable urges to smoke; (2) willingness to accept experiences that cue smoking; and (3) enactment of core life values by making decisions aligned with long term goals rather than short-term urges. (Hayes, 2016, Sairanen et al., 2017) These psychological components distinguish ACT from standard behavioral treatments such as US clinical practice guidelines (USCPG)-based smoking cessation programs that focus on avoidance of urges to smoke and motivate users by using expectancies. (Fiore, 2000) The ACT approach has demonstrated initial feasibility for smoking cessation in the general population, (Bricker et al., 2014a, Bricker et al., 2014b, Bricker et al., 2018, Bricker et al., 2020) including among Spanish-speaking smokers in Spain. (Hernandez-Lopez et al., 2009) Further, experiential avoidance, the core psychological mechanism targeted in ACT, has been consistently related to poorer behavioral health among the Latinx/Hispanic population. (Raines et al., 2018, Zvolensky et al., in press, Mayorga et al., in press, Zvolensky et al., 2015) Moreover, sensitivity to, and tolerance of, aversive internal sensations has been linked to higher coping-oriented expectancies for smoking, poorer quit success, and greater perceived barriers for quitting in Hispanic/Latinx smokers. (Zvolensky et al., 2019a, Zvolensky et al., 2019b, Kauffman et al., 2017, Zvolensky et al., 2007).

No studies have examined the efficacy of an ACT web-delivered smoking cessation intervention for Hispanic/Latinx smokers. In a secondary analysis of the WebQuit randomized trial, we explored the efficacy of an ACT-based website (WebQuit.org) against an USCPG-based website (Smokefree.gov) (Bricker et al., 2018) for smoking cessation in Hispanic/Latinx participants. Since our past research has shown that smoking cessation was mediated through level of engagement, (Bricker et al., 2021) we explored the extent to which cessation outcomes were mediated by level of engagement. We hypothesized that compared to participants in the Smokefree arm, participants in the WebQuit arm would have higher rates of smoking cessation, engagement and satisfaction, and greater increases in ACT-based acceptance of urges to smoke and commitment to quitting smoking.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included in this secondary analysis (N = 222) self-identified as a Hispanic or Latinx person, which includes people of any race (8.4% of the total sample). They were a subset of participants enrolled in the WebQuit parent trial (N = 2637) (Bricker et al., 2018) assessing the efficacy of two web-delivered smoking cessation interventions. Eligibility criteria included: 1) 18 years of age; 2) smoke at least 5 cigarettes per day for the last 12-months; 3) motivated to quit in the next 30 days; 4) reside in the US; 5) able to read in English; 6) have Internet and email access; 7) have never used Smokefree.gov; 8) not currently enrolled in any cessation interventions; and 9) not having another household member participating. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all study procedures. The trial was registered on ClincialTrials.gov (NCT01812278).

Compared to all participants in the WebQuit parent trial, (Bricker et al., 2018) Hispanic/Latinx participants were younger (mean (SD) age = 37.5 (11.3) vs. 46.9 (13.2)), more likely to be male (28% vs. 20%), and less likely to be White (48% vs. 79%). Employment status, education, income, and positive screen for depression did not differ between groups. Hispanic/Latinx participants smoked fewer cigarettes per day, were less likely to be long-time smokers, and less likely to be nicotine dependent compared with all participants. Although use of e-cigarettes, past year quit attempts, and confidence in quitting did not differ between groups, Hispanic/Latinx participants were more likely to report heavy drinking (21% vs. 10%).

2.2. Recruitment, and enrollment

Participants were recruited through (1) Google, Craigslist, and Facebook ads; (2) online survey panel; (3) search engine results; (4) family/friend referrals; and (5) traditional media. The recruitment period was from March 2014 through August 2015. Interested individuals completed an online screening survey. Those who screened eligible were sent a link to provide informed consent, complete a baseline survey, and fill out a contact form. Details of the WebQuit trial have been published. (Bricker et al., 2018) Briefly, 2,637 adults were randomized 1:1 to receive a web-delivered program based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., 2013) or on US Clinical Practice Guidelines (USCPG) (Smokefree.gov) (Smokefree.gov., 2020) for 12-months. Follow-up assessments were completed at 3, 6, and 12-months primarily via self-administered online questionnaires. To mimic real-world use, participant access to their assigned website was not withdrawn at study completion. Participants were compensated $25 for completing each survey and received an additional $10 incentive for responding within 24 hours of receiving the emailed survey link.

2.3. Interventions

2.3.1. WebQuit.org

WebQuit covered the six core processes in ACT— Values, Committed Action, Willingness, Being Present, Cognitive Diffusion, and Self-as-Context. The program had four parts. Step 1, Make a Plan, allowed users to develop a personalized quit plan, identify smoking triggers, learn about FDA-approved cessation medications, and upload a photo of their inspiration to quit. Step 2, Be Aware, contained exercises to illustrate the problems with trying to control thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations rather than allowing them to come and go. Step 3, Be Willing, contained exercises to help users practice allowing thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations that trigger smoking. Step 4, Be Inspired, contained exercises to help participants identify deeply held values inspiring them to quit smoking and to exercise self-compassion in response to smoking lapses. The program prompted users to track smoking and the use of cessation medications. WebQuit did not contain content specifically tailored to Hispanic/Latinx adults.

2.3.2. Smokefree.gov

We hosted a secured private version of the Smokefree site. Users were able to navigate through all pages of the website at any time and there were no restrictions on the order in which the content could be viewed. Smokefree had three main sections. The “Quit today” section had seven pages of content that provided tips for the quit day, staying smoke-free, and dealing with tobacco cravings, as well as information on withdrawal, benefits of quitting, and FDA-approved cessation medications. The “Prepare to quit” section had content providing information on reasons to quit, what makes quitting difficult, how to make a quit plan, and using social support during a quit attempt. The “Smoking issues” section provided information on health effects of smoking and quitting, depression, stress, secondhand smoke, and tips for coping with the challenges of quitting smoking. The section also contained quizzes that provided feedback about level of depression, stress, nicotine dependence, nicotine withdrawal, and secondhand smoke.

2.4. Measures

Socio-demographic data included information on geographic location (zip codes), age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, employment status, income, marital status, sexual orientation, and screening results for depression via the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-20; cutoff 16). (Radloff, 1977) Smoking behaviors data collected included nicotine dependence via the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), (Heatherton et al., 1991) number of cigarettes smoked per day, years of smoking, use of e-cigarettes in past month, and friends and family who smoke. Alcohol consumption was assessed via the Quick Drinking Screen. (Roy et al., 2008) Heavy drinking was defined as 4 drinks for women on a drinking day and 5 drinks for men on a drinking day in the past 30 days.

Cessation outcomes were measured at the 3, 6 and 12-month follow-ups. Consistent with the WebQuit parent trial, (Bricker et al., 2018) the primary smoking cessation outcome was self-reported complete-case 30-day point-prevalence abstinence (PPA) at 12-months. Secondary smoking cessation outcomes were: 30-day PPA at the 3 and 6-month follow-ups; 7-day PPA at all follow-ups; and multiple imputation and missing-as-smoking of 30-day PPA at 12-months.

Level of engagement was measured through multiple indicators of intervention engagement, including: 1) number of logins, 2) number of unique days logged into the website, 3) length of website from first to last day of use, 4) minutes spent on the website per session, and 5) total minutes spent on the website. Satisfaction with the assigned website was measured at the 3-month follow-up via an 11-item measure of satisfaction, adapted from previous research. (Bricker et al., 2018).

Acceptance of urges to smoke was measured at baseline and 3-months via a nine-item physical sensations subscale of the validated Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (adapted from Gifford et al.) (Gifford et al., 2004) to assess willingness to experience and not act on urges to smoke. Response choices for each item ranged from “Not at all” (1) to “Very willing” (5). Scores were derived by averaging the items. Commitment to quitting smoking (CQS) was measured at baseline and 3 months via a modified 11-item CQS score (Kahler et al., 2007) to assess participants’ sense of obligation to continue to quit smoking even when facing barriers such as cravings and discomfort.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were summarized overall and by arm. Zip codes were linked to geographic location using the R library ‘zipcode’ to determine urban or rural residence (zipcode, 2012). Adjusted logistic regression models were used to evaluate differences in smoking cessation outcomes between groups. As a sensitivity analysis, multiple imputation was used to estimate missing 30-day PPA at 12-months. Effect sizes and standard errors from ten imputed datasets were pooled using Rubin’s rules (Rubin, 1987) to generate an odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. Outcome models were adjusted for treatment group assignment and baseline factors used in stratified randomization (i.e., education, gender, and smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day). To reduce the potential for confounding, baseline demographic and smoking variables were included in models as covariates if they differed by treatment group and were associated with the outcome (for details refer to table footnotes). Adjusted negative binomial models were used to evaluate differences in website engagement outcomes, which were heavily right-skewed. Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SAS was used to test mediation of the effect of treatment on smoking cessation by level of engagement. (Hayes, 2018) Indirect effects were estimated with 5,000 bootstrapped samples and were considered statistically significant when bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals did not include zero. Statistical tests were 2-sided, with α = 0.05. Regression analyses were completed using R, version 4.0.3, library ‘MASS’ for negative binomial regression, and library ‘mice’ for multiple imputation. (R Core Team, 2020, Venables and Ripley, 2002, mice, 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Enrollment and data retention

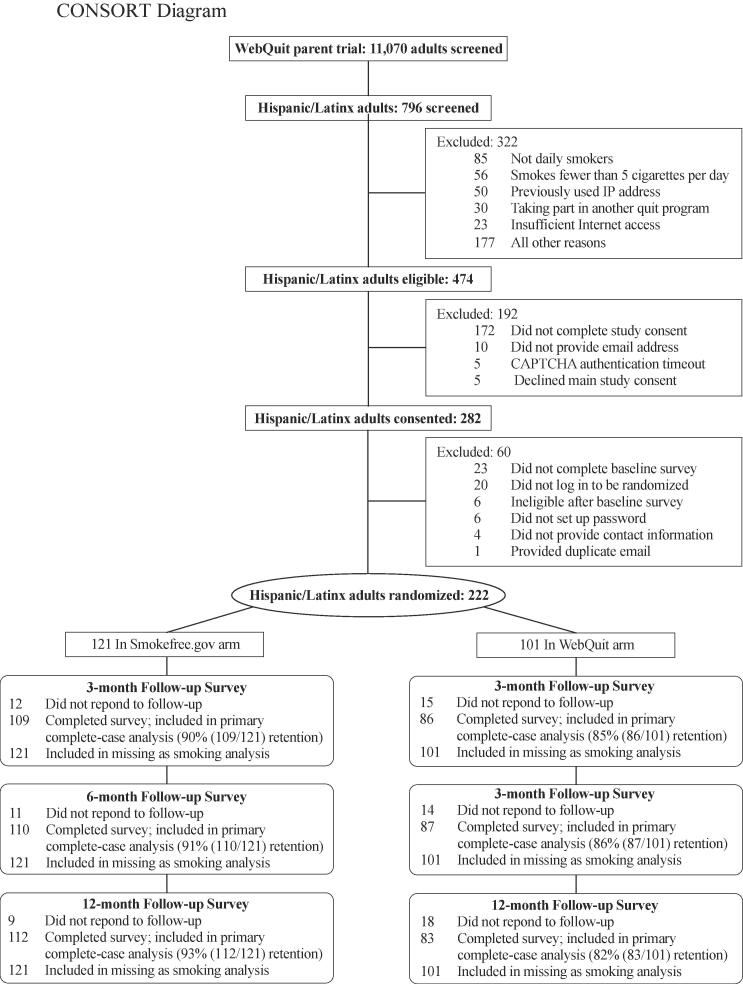

Fig. 1 illustrated the flow of participants through the study, and Supplementary Fig. 1 illustrates the geographical location of trial participants recruited from 38 US states, with 12% residing in rural areas. Study retention, defined as the proportion of study participants who provided cessation outcome data, was 88%, 89%, and 88% at the 3, 6 and 12-month follow-ups, respectively. Retention rates did not differ between arms at the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups (p > 0.05) but did differ at the 12-month follow-up (82% WebQuit vs. 93% Smokefree, p = 0.024).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

On average, Hispanic/Latinx participants were 38 years old and 28% male (Table 1). More than half (55%) were employed, 30% reported high school education or less, and 27% reported annual household incomes of <$20,000. The majority screened positive for depression (60%). Slightly less than half (47%) were highly dependent on nicotine (FTND scores 6) and 65% reported smoking for 10 years. CQS at baseline was high, mean (SD) 4.1 (0.7), within a 1–5 scoring range (5 = extremely committed). Most baseline characteristic and smoking behaviors were equally distributed between treatment arms. The only differences were that Hispanic/Latinx participants in the WebQuit arm were younger (p = 0.038) and less likely to report heavy drinking than those in the Smokefree arm (13% WebQuit vs. 27% Smokefree, p = 0.020).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Hispanic/Latinx trial participants.

| Characteristic | n | No. (%) or Mean (SD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 222) | Smokefree.gov (n = 121) | WebQuit (n = 101) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 222 | 37.5 (11.3) | 38.9 (11.8)* | 35.8 (10.5) |

| Female | 222 | 159 (72%) | 88 (73%) | 71 (70%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 222 | 106 (48%) | 67 (55%) | 39 (39%) |

| Black or African American | 222 | 14 (6%) | 5 (4%) | 9 (9%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 222 | 5 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (4%) |

| Asian | 222 | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 222 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| More than one race | 222 | 21 (9%) | 11 (9%) | 10 (10%) |

| Unknown race | 222 | 74 (33%) | 37 (31%) | 37 (37%) |

| High school or less education | 222 | 67 (30%) | 39 (32%) | 28 (28%) |

| Employed | 222 | 121 (55%) | 63 (52%) | 58 (57%) |

| Low income, <$20,000/year | 222 | 61 (27%) | 37 (31%) | 24 (24%) |

| Married | 222 | 80 (36%) | 40 (33%) | 40 (40%) |

| LGB | 222 | 36 (16%) | 23 (19%) | 13 (13%) |

| Rural residence | 221 | 26 (12%) | 13 (11%) | 13 (13%) |

| Depression positive screening resultsa | 222 | 134 (60%) | 76 (63%) | 58 (57%) |

| Smoking behaviour | ||||

| FTND score, mean (SD) | 222 | 5.3 (2.4) | 5.2 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.4) |

| High nicotine dependence (FTND score ≥ 6) | 222 | 105 (47%) | 54 (45%) | 51 (50%) |

| Time to first cigarette within 5 min of waking | 222 | 91 (41%) | 49 (40%) | 42 (42%) |

| Smokes more than one-half pack/d | 222 | 144 (65%) | 78 (64%) | 66 (65%) |

| Smokes more than 1 pack/d | 222 | 51 (23%) | 31 (26%) | 20 (20%) |

| Smoked for 10 years | 222 | 145 (65%) | 83 (69%) | 62 (61%) |

| Used e-cigarettes at least once in past month | 222 | 66 (30%) | 35 (29%) | 31 (31%) |

| Quit attempts in past 12-months, mean (SD) | 205 | 2.0 (7.9) | 1.4 (3.1) | 2.8 (11.3) |

| Commitment to quit smoking, mean (SD)b | 220 | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.1 (0.7) |

| Friend and partner smoking | ||||

| Close friends who smoke, mean (SD) | 222 | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.7) |

| No. of housemates who smoke, mean (SD) | 222 | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| Living with partner who smokes, n (%) | 222 | 66 (30%) | 30 (25%) | 36 (36%) |

| Heavy drinker, n (%)c | 218 | 45 (21%) | 32 (27%)* | 13 (13%) |

| ACT-based acceptance of urges to smoke, mean (SD) | 220 | 2.9 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) |

Abbreviations: FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; GED, General Education Development; LGB, lesbian, gay, or bisexual.

* Significantly higher, p < 0.05.

Positive screening results for depression via the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-20; cutoff 16).

Commitment to quitting smoking scale (CQSS) scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating higher levels of commitment to quitting smoking.

Heavy drinking was defined as 4 or more drinks for women on a typical drinking day and 5 or more drinks for men on a typical drinking day in the past 30 days.

3.3. Quit rates

Table 2 illustrates that WebQuit participants had 1.93 times higher odds of 12-month abstinence compared to Smokefree participants (40% vs. 25%; OR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.04, 3.59). Findings were similar for the multiple imputation (36% vs. 26%; OR = 1.95 95% CI: 1.08, 3.50), and non-significant for the missing-as-smoking imputation (33% vs. 23%; OR = 1.58 95% CI: 0.87, 2.87). The 30-day PPA at 6-months (26% WebQuit vs. 17% Smokefree) and 3-months (16% WebQuit vs. 16% Smokefree) did not significantly differ between arms. The 7-day PPA was descriptively higher in the WebQuit relative to the Smokefree arm at the 12-month follow-up, but not at 6-month or 3-month follow-ups.

Table 2.

Smoking cessation outcomes by follow-up time point.

| Variable | No. (%) |

OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Hispanic/Latinx participants (N = 222) | Smokefree.gov (n = 121) | WebQuit (n = 101) | |||

| 12-months outcomes | |||||

| 30-d PPA | 61/195 (31%) | 28/112 (25%) | 33/83 (40%) | 1.93 (1.04, 3.59) | 0.037 |

| 30-d PPA, multiple imputation | 717/2220 (32%) | 308/1210 (26%) | 409/1010 (36%) | 1.95 (1.08, 3.50) | 0.027 |

| 30-d PPA, missing-as-smoking | 61/222 (27%) | 28/121 (23%) | 33/101 (33%) | 1.58 (0.87, 2.87) | 0.136 |

| 7-d PPA | 77/195 (39%) | 38/112 (34%) | 39/83 (47%) | 1.68 (0.93, 3.03) | 0.085 |

| 7-d PPA, missing-as-smoking, n (%) | 77/222 (35%) | 38/121 (31%) | 39/101 (39%) | 1.35 (0.77, 2.37) | 0.295 |

| 6-months outcomes | |||||

| 30-d PPA | 42/197 (21%) | 19/110 (17%) | 23/87 (26%) | 1.68 (0.83, 3.40) | 0.150 |

| 7-d PPA | 69/197 (35%) | 35/110 (32%) | 34/87 (39%) | 1.31 (0.72, 2.40) | 0.376 |

| 3-months outcomes | |||||

| 30-d PPA | 31/195 (16%) | 17/109 (16%) | 14/86 (16%) | 1.00 (0.45, 2.22) | 0.997 |

| 7-d PPA | 54/195 (28%) | 31/109 (28%) | 23/86 (27%) | 0.89 (0.47 1.70) | 0.723 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PPA, point prevalence abstinence.

aTwo-sided p values were calculated from regression models adjusted for factors used in stratified randomization: gender, education, and heavy smoking. Results did not differ in unadjusted models.

3.4. Engagement and satisfaction

Participants in the WebQuit arm spent more time using the website overall (29.7 vs. 11.9 min, p < 0.001) and per session than Smokefree participants (6.8 vs. 3.1 min, p < 0.001) (Table 3). WebQuit participants also had a greater mean number of logins (5.6 vs. 4.1, p = 0.074) and unique days of use (4.5 vs. 3.5, p = 0.052) than Smokefree participants, albeit nonsignificant. The length of website usage (first to last day), was similar between arms (52.6 days WebQuit vs. 56.5 days Smokefree, p = 0.713). Analyses did not show evidence that differences in quit rates were mediated by level of engagement.

Table 3.

Treatment engagement and satisfaction of the assigned website.

| Variable | N | Mean (SD) or No. (%) |

Incident Rate Ratio or Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 222) | Smokefree (n = 121) | WebQuit (n = 101) | ||||

| Engagement variable | ||||||

| No. of times logged inb | 222 | 4.8 (7.0)c | 4.1 (4.2)c | 5.6 (9.2)c | Incident Rate Ratio: 1.26 (0.98, 1.62) | 0.074 |

| No. of unique days of usec | 222 | 3.9 (4.9)d | 3.5 (3.4)c | 4.5 (6.2)d | Incident Rate Ratio: 1.26 (1.00, 1.60) | 0.052 |

| Minutes spent on the website per session | 222 | 4.7 (5.2)e | 3.1 (2.5)f | 6.8 (6.1)g | Incident Rate Ratio: 2.18 (1.71, 2.77) | <0.001 |

| Total minutes spent on the websiteb | 222 | 20.0 (29.7)h | 11.9 (16.1)i | 29.7 (38.2)j | Incident Rate Ratio: 2.32 (1.68, 3.20) | <0.001 |

| Length of use of website in days (total) | 222 | 54.7 (84.7)k | 56.5 (87.4)l | 52.6 (81.7)m | Incident Rate Ratio: 0.93 (0.62, 1.38) | 0.713 |

| Satisfaction at 3-months, No. (%) | ||||||

| Satisfied with assigned website | 170 | 137/170 (81%) | 81/99 (82%) | 56/71 (79%) | Odds Ratio: 0.89 (0.41, 1.94) | 0.777 |

| Website was useful for quitting | 175 | 126/175 (72%) | 76/99 (77%) | 50/76 (66%) | Odds Ratio: 0.60 (0.30, 1.17) | 0.131 |

| Would recommend assigned website | 153 | 140/153 (92%) | 79/86 (92%) | 61/67 (91%) | Odds Ratio: 0.97 (0.30, 3.11) | 0.952 |

aTwo-sided p values were calculated from regression models adjusted for factors used in stratified randomization: gender, education, and heavy smoking.

bModel further adjusted for age and heavy drinking.

cModel further adjusted for age.

Median values, c 3; d 2; e 3.3; f 2.2; g 5.5; h 10.4; i 6.3; j 16.3; k 17.5; l 20; m 15.

Rates of overall satisfaction with the assigned websites were similar between arms (79% WebQuit vs. 82% Smokefree, p = 0.777). The proportion of participants who found their assigned website useful for quitting was slightly higher for Smokefree, albeit nonsignificant (66% WebQuit vs. 77% Smokefree, p = 0.131). The proportion of participants who would recommend their assigned website did not differ between arms (91% WebQuit vs. 92% Smokefree, p = 0.131).

3.5. Change in ACT-based acceptance process and commitment to quitting

Change from baseline to 3-months in acceptance of urges to smoke did not differ between arms (point estimate for difference = 0.1 95% CI: (-0.2, 0.3); p = 0.558), or change in CQS (point estimate = 0.1 95% CI: (-0.1, 0.2); p = 0.562). Therefore, no further mediational analyses were conducted.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to show that, among Hispanic/Latinx smokers, an ACT-based website was more efficacious for smoking cessation than the standard of care USCPG-based website. At 12-months, the complete-case 30-day point prevalence abstinence was 40% for WebQuit compared to 25% for Smokefree participants (p = 0.037), which is a clinically significant effect. (West, 2007) Findings were similar and significant for the multiple imputation sensitivity analysis. (van Ginkel et al., 2020) However, effect sizes were reduced and non-significant for the missing-as-smoking imputation (33% WebQuit vs. 23% Smokefree; p = 0.136). Importantly, the missing-as-smoking imputation may be less reliable and subject to bias due to differential attrition rates at 12-months (18% WebQuit vs. 7% Smokefree), favoring the treatment arm with less attrition. Nelson et al., 2009, Hedeker et al., 2007 Nonetheless, quit rates between 33% and 40% for WebQuit participants would have very high public health impact given the potential for the WebQuit web-delivered intervention to reach thousands of Hispanic/Latinx smokers at low cost. These findings are important and novel for two main reasons: 1) results add much-needed empirical evidence to a field that has a dearth of literature on smoking cessation interventions for the historically underserved and rapidly growing Hispanic/Latinx population; and 2) this is the first study, to our knowledge, that explored the efficacy of a digital intervention for smoking cessation among US Hispanics/Latinx smokers in a randomized controlled trial.

The present results are also a major advance over the existing body of literature on digital interventions for smoking cessation among Hispanic/Latinx populations, which has consisted of single-arm feasibility pilot trials. (Cupertino et al., 2019; , Chalela, 2000, Cartujano-Barrera et al., 2020, Cartujano-Barrera et al., 2021) Although there is some limited evidence that in-person or telephone-based based interventions for smoking cessation that have been culturally adapted to Hispanic/Latinx populations are efficacious, (Munoz et al., 1997, Woodruff et al., 2002, Wetter et al., 2007) most of the in-person and telephone-based studies were limited by short follow-up time periods ranging from 3 to 6 months. We are aware of only one randomized controlled trial with long-term follow-up that has demonstrated efficacy among 1417 Hispanics/Latinx adult smokers. That study tested a culturally tailored, Spanish language intervention for smoking cessation of written materials mailed monthly over 18 months compared to a one-time standard of care booklet developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). (Simmons et al., 2021) The 12-month quit rates in the intervention were 21.3% vs 11.1% in the control group, but the results are limited by high rates of missing data (i.e., 26%). By contrast, the current study showed higher 12-month quit rates of 40% in the WebQuit vs 25% in the Smokefree arm in a sample with overall high data retention rate (i.e., 88%). Quit rates were higher at 12-months than at 3- or 6-months. It is possible that an increasing number of quit attempts at each follow-up time point led to success later in time, because it may take many quit attempts to be successful. (Chaiton et al., 2016) Indeed, we found that the mean (SD) number of quit attempts at 3, 6, and 12-months were 8.6 (15.3), 7.9 (19.8), and 13.8 (42.8), respectively. Future studies on the nature of the association between quit attempts and quit success are needed.

WebQuit participants were also significantly more engaged with their assigned website than Smokefree participants. Although the analyses conducted for this study indicated that neither ACT-based acceptance processes nor level of engagement explained the higher quit rate in the WebQuit arm compared to the Smokefree arm, we postulate that the mechanisms behind the differential cessation rates might center on ACT-based processes focusing on values. Hispanic/Latinx cultures have historically been collectivistic with values that focus on familismo, respeto, personalismo, and simpatia. (Zinser et al., 2011) Thus, these groups tend to place a strong emphasis on how they live their lives based on values such as being family-oriented and respect for social relationships. As such, we believe there is congruity between core ACT processes and Hispanic/Latinx cultural principles. Central to ACT-based interventions is helping people identify deeply held values, such as family and spirituality, that can be used to help inspire them to quit smoking. This link between the importance of key cultural values, which may be more salient for Hispanic/Latinx individuals, and an intervention that leverages values to help people quit smoking may be the reason behind the higher quit rate in the WebQuit arm. This could also explain why WebQuit was more efficacious for smoking cessation than Smokefree in this subset of Hispanic/Latinx adults who participated in the WebQuit parent trial, whereas quit rates did not differ in the larger sample of adult smokers enrolled in the parent trial. (Bricker et al., 2018) However, this study did not measure participants’ values or how values played a role in a participant’s smoking cessation. Future studies could help identify and link a participant’s values with smoking cessation outcome.

The current study addresses many of the limitations of the prior research on smoking cessation for Hispanic/Latinx adults. First, the long follow-up period of 12-months could partially account for relapse occurring during the first year of quitting smoking. Second, the trial has an overall high retention rate at the 12-month follow-up of 88%. Third, the geographic diversity of the sample, recruited from 38/50 US states, provides broader generalization of the result. Finally, because US Hispanic/Latinx adults are the least likely of any racial/ethnic group to have insurance coverage, (Cohen et al., 2021) web-delivered interventions may directly combat this barrier.

The present study has some limitations. First, the results are from a secondary analysis, and therefore, the results should be conceptually contextualized as exploratory. Second, the subset of Hispanic/Latinx participants in this study were all English speakers and therefore, the results may not be representative of the full population of Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latinx adult smokers in the US or those who are not daily smokers. Third, the differential attrition rates between arms at 12-months should be noted. However, this limitation is unlikely for several reasons: (1) baseline characteristics were unrelated to retention, (2) participants were blinded to treatment assignments, (3) treatments were matched for intensity and follow-up duration, and (4) there was no differential attrition in the parent trial. (Bricker et al., 2018) Therefore, the differential attrition found in this subsample of Hispanic/Latinx adults may be due to sampling error, and thus, unrelated to design factors. Fourth, study measures have not been specifically validated in this group of Hispanic/Latinx adult smokers and therefore, further validation is warranted. Finally, smoking status was not biochemically verified. The self-reported outcome was prespecified based on methodological problems with remote biochemical verification. (Herbec et al., 2019) And while some previous studies have demonstrated strong agreement between self-reported and biochemically verified smoking status, (Wong et al., 2012) others showed evidence of significant discordance. (Patrick et al., 1994) Therefore, the external validity of the smoking status in this trial is not known.

Overall, the current study is an important, yet initial step in identifying an existing intervention that could be adapted and tested in a future trial to help Hispanic/Latinx smokers quit. Given that more than 43 million people in the US speak Spanish as their first language, Pew Research Center (2021) there is ample room for improvement in a future Spanish-language adaptation of ACT-based digital interventions that could further increase the reach and acceptability of these tools nationwide, including Puerto Rico, and among those who are non-daily or light smokers. Additionally, because of the heterogeneity in smoking rates between Hispanic/Latinx subgroups, also needed is the inclusion of additional variables (i.e., subethnicities/nationality, years in the US, and acculturation) to allow for a deeper exploration of intervention targets. Sociocultural moderators of treatment outcomes (e.g., discrimination, social status) could also be explored.

5. Conclusions

An ACT-based digital intervention for smoking cessation may be more efficacious and engaging among Hispanic/Latinx smokers than the standard of care digital intervention. Further testing of the underlying mechanisms of web-delivered ACT is needed to understand why this intervention may be more efficacious and engaging for helping Hispanic/Latinx adults quit smoking.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jonathan J. Bricker, Diana M. Kwon, and Kristin E. Mull conceptualized the study. Diana M. Kwon and Margarita Santiago-Torres led manuscript writing. Kristin Mull led and conducted data analysis. All authors assisted in manuscript writing and provided critical review. All authors have read and agreed to the published versions of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the NIH (NIH: 5R01CA166646 and 5R01CA192849), awarded to Dr. Bricker, from the National Cancer Institute. We appreciate the tireless contributions of the entire study staff, most notably Eric Meier, Carolyn Ehret, Brianna Sullivan, the design services of Blink UX, and the development services of Moby, Inc. We are very appreciative of the study participants.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101952.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley S.J., Thomas C.C., Sharapova S.R., Momin B., Massetti G.M., Winn D.M., Armour B.S., Richardson L.C. Vital Signs: Disparities in Tobacco-Related Cancer Incidence and Mortality — United States, 2004–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2016;65(44):1212–1218. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.2020.

- Kaplan RC, Baldoni PL, Strizich GM, et al. Current Smoking Raises Risk of Incident Hypertension: Hispanic Community Health Study-Study of Latinos. Am J Hypertens. 2021. 34(2). 190-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaplan R.C., Bangdiwala S.I., Barnhart J.M., Castañeda S.F., Gellman M.D., Lee D.J., Pérez-Stable E.J., Talavera G.A., Youngblood M.E., Giachello A.L. Smoking among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults: the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;46(5):496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C.R., Isasi C.R., Strizich G., Castañeda S.F., Gellman M., Maisonet Giachello A.L., Lee D.J., Penedo F.J., Perreira K.M., Kaplan R.C. Smoking cessation among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults: Findings from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Prev. Med. 2015;81:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S., Malarcher A., Asman K., Johns M., Caraballo R., VanFrank B., Garrett B. Disparities in Cessation Behaviors Between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Adult Cigarette Smokers in the United States, 2000–2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17 doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M.R., Wang T.W., Babb S., Cullen K.A., Day H., Willis G., Jamal A., Neff L. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1013–1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, LJ N. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 201MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1. 2020.

- Babb S., Malarcher A., Schauer G., Asman K., Jamal A. Quitting Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–1464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klugman M., Hosgood H.D., Hua S., Xue X., Vu T.-H., Perreira K.M., Castañeda S.F., Cai J., Pike J.R., Daviglus M., Kaplan R.C., Isasi C.R. A longitudinal analysis of nondaily smokers: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Ann. Epidemiol. 2020;49:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger A.H., Giovenco D.P., Zhu J., Lee J., Kashan R.S., Goodwin R.D. Racial/ethnic differences in daily, nondaily, and menthol cigarette use and smoking quit ratios in the United States: 2002 to 2016. Prev. Med. 2019;125:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell B.N., Garrett B.E., Caraballo R.S. Disparities in Adult Cigarette Smoking – United States, 2002–2005 and 2010–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2016;65(30):753–758. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad D.R., Perez-Stable E.J., White M.M., Emery S.L., Messer K. A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101(4):699–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hispanic Population to reach 111 Million by 2060. Unites States Census Bureau. 2018.

- Mai Y., Soulakova J.N. Retrospective reports of former smokers: Receiving doctor's advice to quit smoking and using behavioral interventions for smoking cessation in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhan S, Hu L, Wilson KM, Mazumdar M, Liu B. Examining the role of healthcare access in racial/ethnic disparities in receipt of provider-patient discussions about smoking: A latent class analysis. Prev Med. 2021. 148. 106584. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cohen R.A., Cha A.E., Terlizzi E.P., Martinez M.E. Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States, 2019. Natl Health Stat Report. 2021;159:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras O.D., Feldman R.H., Kanamori M., Rivera I., Chen L.u., Baezconde-Garbanati L., Nodora J., Noltenius J. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation among Latino adults. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 2011;103(5):423–431. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Rios L., Parascandola M. A historical review of R.J. Reynolds' strategies for marketing tobacco to Hispanics in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(5):e15–e27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Internet & Technology. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. 2021.

- Graham A.L., Amato M.S. Twelve Million Smokers Look Online for Smoking Cessation Help Annually: Health Information National Trends Survey Data, 2005–2017. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019;21(2):249–252. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B., Bartlett Y.K., Tooley E., Armitage C.J., Wearden A. Prevalence and Frequency of mHealth and eHealth Use Among US and UK Smokers and Differences by Motivation to Quit. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(7):e164. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A., Phillips E., Gentzke A.S., Homa D.M., Babb S.D., King B.A., Neff L.J. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53–59. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Levin M.E., Plumb-Vilardaga J., Villatte J.L., Pistorello J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav. Ther. 2013;44(2):180–198. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallion E., Zvolensky M.J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for smoking cessation: A synthesis. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;2:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies – Republished Article. Behav. Ther. 2016;47(6):869–885. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen E., Tolvanen A., Karhunen L., Kolehmainen M., Järvelä-Reijonen E., Lindroos S., Peuhkuri K., Korpela R., Ermes M., Mattila E., Lappalainen R. Psychological flexibility mediates change in intuitive eating regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy interventions. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(9):1681–1691. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M.C. US public health service clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence. Respir Care. 2000;45(10):1200–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J.B., Bush T., Zbikowski S.M., Mercer L.D., Heffner J.L. Randomized trial of telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: a pilot study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16(11):1446–1454. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J.B., Mull K.E., Kientz J.A., Vilardaga R., Mercer L.D., Akioka K.J., Heffner J.L. Randomized, controlled pilot trial of a smartphone app for smoking cessation using acceptance and commitment therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J.B., Mull K.E., McClure J.B., Watson N.L., Heffner J.L. Improving quit rates of web-delivered interventions for smoking cessation: full-scale randomized trial of WebQuit.org versus Smokefree.gov. Addiction. 2018;113(5):914–923. doi: 10.1111/add.14127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J.B., Watson N.L., Mull K.E., Sullivan B.M., Heffner J.L. Efficacy of Smartphone Applications for Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1472–1480. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Lopez M., Luciano M.C., Bricker J.B., Roales-Nieto J.G., Montesinos F. Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: a preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009;23(4):723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines E.M., Rogers A.H., Bakhshaie J., Viana A.G., Lemaire C., Garza M., Mayorga N.A., Ochoa-Perez M., Zvolensky M.J. Mindful attention moderating the effect of experiential avoidance in terms of mental health among Latinos in a federally qualified health center. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:574–580. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Rogers AH, Mayorga NA, et al. Perceived discrimination, experiential avoidance, and mental health among Hispanic adults in primary care. Transcult Psychiatry. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mayorga NA, Manning KF, Garey L, Viana AG, Ditre JW, Zvolensky MJ. The role of experiential avoidance in terms of fatigue and pain during COVID-19 among Latinx adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zvolensky M.J., Bakhshaie J., Garza M., Valdivieso J., Ortiz M., Bogiaizian D., Robles Z., Schmidt N.B., Vujanovic A. The role of anxiety sensitivity in the relation between experiential avoidance and anxious arousal, depressive, and suicidal symptoms among Latinos in primary care. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2015;39(5):688–696. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky M.J., Bakhshaie J., Shepherd J.M., Peraza N., Garey L., Viana A.G., Glover N., Brown J.T., Brown R.A. Anxiety sensitivity and smoking among Spanish-speaking Latinx smokers. Addict. Behav. 2019;90:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky M.J., Bakhshaie J., Shepherd J.M., Garey L., Peraza N., Viana A.G., Brown J.T., Brown R.A. Anxiety sensitivity and smoking outcome expectancies among Spanish-speaking Latinx adult smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019;27(6):569–577. doi: 10.1037/pha0000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman B.Y., Garey L., Bakhshaie J., Rodríguez R., Cárdenas S.J., Coy P.E.C., Zvolensk M.J. Distress tolerance dimensions and smoking behavior among Mexican daily smokers: A preliminary investigation. Addict. Behav. 2017;69:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky M.J., Bernstein A., Cardenas S.J., Colotla V.A., Marshall E.C., Feldner M.T. Anxiety sensitivity and early relapse to smoking: a test among Mexican daily, low-level smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007;9(4):483–491. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J.B., Levin M., Lappalainen R., Mull K., Sullivan B., Santiago-Torres M. Mechanisms of Smartphone Apps for Cigarette Smoking Cessation: Results of a Serial Mediation Model From the iCanQuit Randomized Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2021;9(11):e32847. doi: 10.2196/32847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokefree.gov. National Cancer Institute, https://smokefree.gov. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- Radloff L.S. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T.F., Kozlowski L.T., Frecker R.C., Fagerstrom K.O. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M., Dum M., Sobell L.C., Sobell M.B., Simco E.R., Manor H., Palmerio R. Comparison of the quick drinking screen and the alcohol timeline followback with outpatient alcohol abusers. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43(14):2116–2123. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford E.V., Kohlenberg B.S., Hayes S.C., Antonuccio D.O., Piasecki M.M., Rasmussen-Hall M.L., Palm K.M. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behav. Ther. 2004;35(4):689–705. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Lachance HR, Strong DR, Ramsey SE, Monti PM, Brown RA. The commitment to quitting smoking scale: initial validation in a smoking cessation trial for heavy social drinkers. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2420-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- zipcode: U.S. ZIP Code database for geocoding. R package version 1.0. URL: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=zipcode [computer program]. 2012.

- Rubin D.B. Wiley; New York: 1987. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2018. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. URL: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4th ed. Springer; 2002. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2.

- mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011.

- West R. The clinical significance of “small” effects of smoking cessation treatments. Addiction. 2007;102(4):506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ginkel J.R., Linting M., Rippe R.C.A., van der Voort A. Rebutting Existing Misconceptions About Multiple Imputation as a Method for Handling Missing Data. J. Pers. Assess. 2020;102(3):297–308. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1530680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D.B., Partin M.R., Fu S.S., Joseph A.M., An L.C. Why assigning ongoing tobacco use is not necessarily a conservative approach to handling missing tobacco cessation outcomes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009;11(1):77–83. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D., Mermelstein R.J., Demirtas H. Analysis of binary outcomes with missing data: missing = smoking, last observation carried forward, and a little multiple imputation. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1564–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupertino AP, Cartujano-Barrera F, Ramirez M, et al. A Mobile Smoking Cessation Intervention for Mexico (Vive sin Tabaco... inverted exclamation markDecidete!): Single-Arm Pilot Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7(4):e12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chalela P, McAlister AL, Munoz E, et al. Reaching Latinos Through Social Media and SMS for Smoking Cessation. In: Ramirez AG, Trapido EJ, eds. Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos. Cham (CH)2020:187-196. [PubMed]

- Cartujano-Barrera F., Sanderson Cox L., Arana-Chicas E., et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Culturally- and Linguistically-Adapted Smoking Cessation Text Messaging Intervention for Latino Smokers. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:269. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartujano-Barrera F., Pena-Vargas C.I., Arana-Chicas E., et al. Decidetexto: Feasibility and Acceptability of a Mobile Smoking Cessation Intervention in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(4) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz R.F., Marin B.V., Posner S.F., Perez-Stable E.J. Mood management mail intervention increases abstinence rates for Spanish-speaking Latino smokers. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1997;25(3):325–343. doi: 10.1023/a:1024676626955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff S.I., Talavera G.A., Elder J.P. Evaluation of a culturally appropriate smoking cessation intervention for Latinos. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):361–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter D.W., Mazas C., Daza P., et al. Reaching and treating Spanish-speaking smokers through the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Information Service. A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):406–413. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons V.N., Sutton S.K., Medina-Ramirez P., et al. Self-help smoking cessation intervention for Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinxs in the United States: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1002/cncr.33986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton M., Diemert L., Cohen J.E., et al. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011045. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinser MC, Pampel FC, Flores E. Distinct beliefs, attitudes, and experiences of Latino smokers: relevance for cessation interventions. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25(5 Suppl):eS1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herbec A., Brown J., Shahab L., West R. Lessons learned from unsuccessful use of personal carbon monoxide monitors to remotely assess abstinence in a pragmatic trial of a smartphone stop smoking app – A secondary analysis. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.L., Shields M., Leatherdale S., Malaison E., Hammond D. Assessment of validity of self-reported smoking status. Health Rep. 2012;23(1):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D.L., Cheadle A., Thompson D.C., Diehr P., Koepsell T., Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.