Abstract

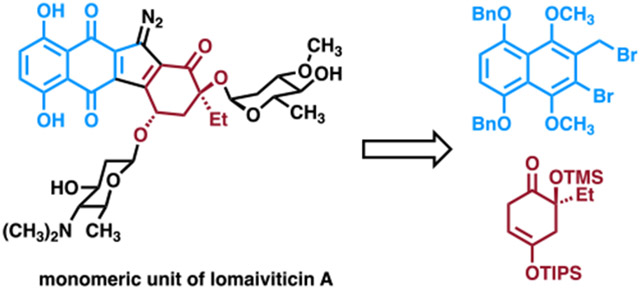

We describe a stereocontrolled synthesis of 3, the fully glycosylated monomeric unit of the dimeric cytotoxic bacterial metabolite (−)-lomaiviticin A (2). A novel strategy involving convergent, site- and stereoselective coupling of the β,γ-unsaturated ketone 6 and the naphthyl bromide 7 (92%, 15:1 diastereomeric ratio (dr)), followed by radical-based annulation and silyl ether cleavage, provided the tetracycle 5 (57% overall), which contains the carbon skeleton of the aglycon of 3. The β-linked 2,4,6-trideoxy-4-aminoglycoside l-pyrrolosamine was installed in 73% yield and with 15:1 β:α selectivity using a modified Koenigs–Knorr glycosylation. The diazo substituent was introduced via direct diazo transfer to an electron-rich benzoindene (4 → 27). The α-linked 2,6-dideoxyglycoside l-oleandrose was introduced by gold-catalyzed activation of an o-alkynyl glycosylbenzoate (75%, >20:1 α:β selectivity). A carefully orchestrated endgame sequence then provided efficient access to 3. Cell viability studies indicated that monomer 3 is not cytotoxic at concentrations up to 1 μM, providing conclusive evidence that the dimeric structure of (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) is required for cytotoxic effects. The preparation of 3 provides a foundation to complete the synthesis of (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) itself.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

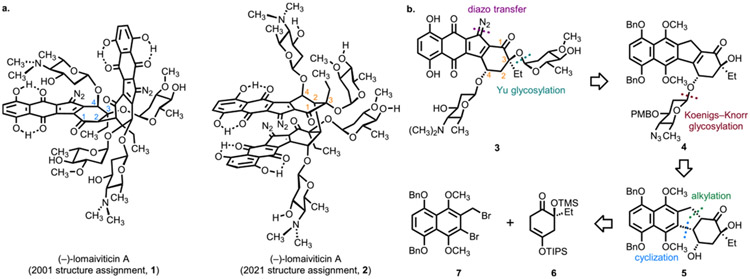

In 2001, researchers at Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and the University of Utah disclosed the isolation of a novel dimeric cytotoxic bacterial metabolite, which they named lomaiviticin A.1 The structure 1 (Figure 1a) was advanced based on high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), NMR (500 MHz 1H and 125 MHz 13C), and IR spectroscopic analysis, as well as comparison to the kinamycins, related monomeric isolates.2 Of note, lomaiviticin A contains two diazotetrahydrobenzo[b]-fluorene (diazofluorene) residues and four deoxyglycosides, two of which are β-linked, and a single carbon─carbon bond linking each half of the molecule. Due to its potent biological activity (low nM half-maximal inhibitory potencies (IC50s) against cultured human cancer cell lines),1 unique mechanism of action (induction of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)),3 and complex structure, the total synthesis of structure 1 was pursued for over 20 years.4 Despite these extensive efforts, there had not been a complete synthetic route to 1 or single-crystal X-ray analysis of any natural isolate, leaving the original assignment untested. In 2021, microED analysis of the related metabolite lomaiviticin C (not shown)5 led to revision of the structure of lomaiviticin A as 2.6,7 These studies were supported by high-field (800 MHz 1H, 200 MHz 13C, cold probe) NMR analysis, which provided insights into the basis of the original misassignment, as well as quantum mechanical NMR calculations, which were consistent with structure 2, but not 1. Structures 1 and 2 differ in the relative orientation of the cyclohexanone and diazofluorene residues and in the orientation of the oxygen substituent bearing the β-N,N-dimethyl-l-pyrrolosamine.

Figure 1.

(a) The structure of (−)-lomaiviticin A was originally assigned as 1 but was later shown to be 2 by microED, NMR, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis. (b) The monomeric diazofluorene 3 was prepared from the synthetic precursors 6 and 7 via the benzoindene intermediate 4.

We initially considered adapting our earlier work, which was directed toward structure 1, to 2.8 However, such a strategy would require introduction of both aminosugar residues to a dimeric diol acceptor, as well as extensive lateral manipulations of the cyclohexanone stereocenters and oxidation states early in the sequence. Indeed, exploratory experiments made it clear to us that our existing route could not provide efficient access to structure 2 or advanced intermediates, necessitating the development of the novel synthetic strategy described here.9

Given the immense synthetic challenges presented by structure 2, we targeted the fully glycosylated monomeric unit 3 for synthesis. This approach was pursued by Nicolaou and co-workers in their synthesis of the monomeric unit corresponding to structure 1.4s We envisioned studies of 3 would allow us to define the key strategies and transformations, such as construction of the carbon skeleton, glycosylation methods, and introduction of the diazo residue, required to ultimately access (−)-lomaiviticin A (2). Additionally, as the correct monomeric unit has never been synthesized and tested for biological activity, this approach would allow the first direct determination of the effect of dimerization on cytotoxicity. Accordingly, we devised the route shown in Figure 1b. The route features a novel fragment coupling10 and radical-based annulation to access the tetracyclic carbon skeleton and installation of the diazo group directly to an electron-rich benzoindene. The stereocontrolled synthesis of 2-deoxyglycosides is challenging.11 We were able to successfully introduce each carbohydrate in the target with high levels of stereocontrol.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

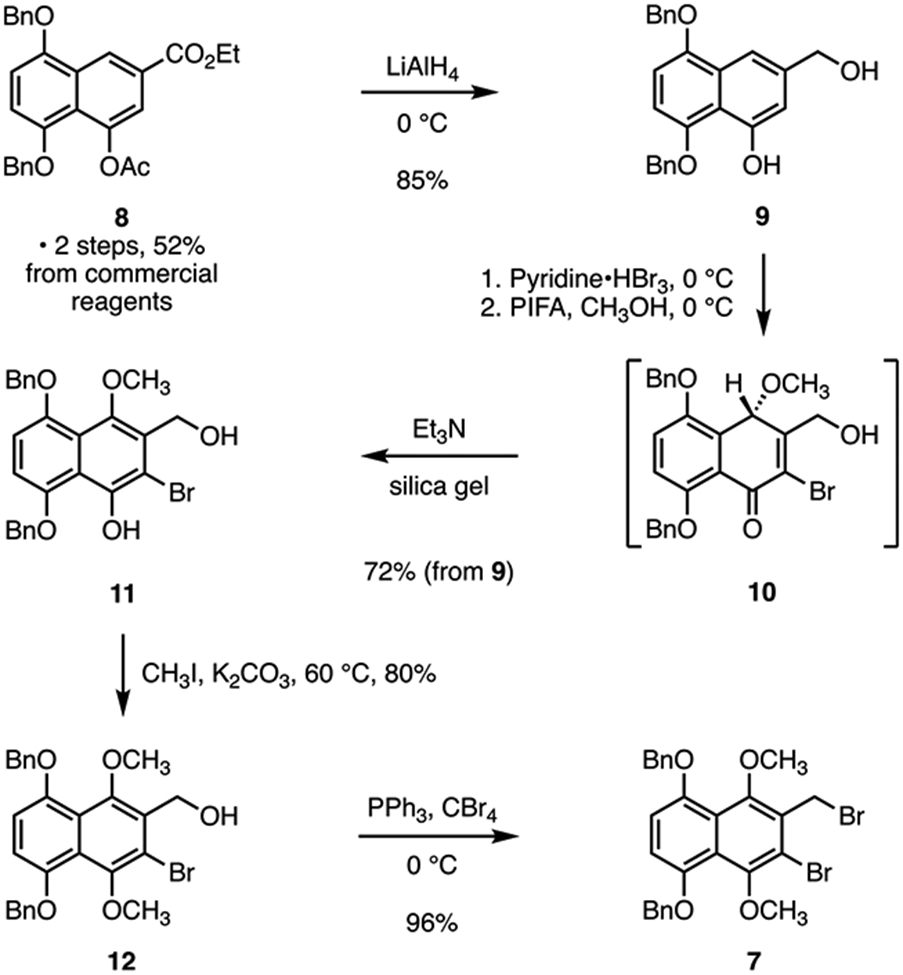

Our synthesis of the hydronaphthoquinone 7 is shown in Scheme 1. Reduction (lithium aluminum hydride) of ethyl 4-acetoxy-5,8-bis(benzyloxy)-2-naphthoate (8, obtained in two steps and 52% yield from commercial reagents)12 provided 5,8-bis(benzyloxy)-3-(hydroxymethyl)naphthalen-1-ol (9, 85%). Site-selective bromination (pyridinium tribromide)13 followed by oxidation (bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodobenzene, PIFA)14 generated the cyclohexanone derivative 10. Purification of 10 on triethylamine-impregnated silica gel promoted enolization to 5,8-bis(benzyloxy)-2-bromo-3-(hydroxymethyl)-4-methoxynaphthalen-1-ol (11; 72% from 9). Selective methylation of the naphthol residue (potassium carbonate, methyl iodide, 80%) followed by deoxybromination of the benzylic alcohol (triphenylphosphine, carbon tetrabromide) yielded the hydronaphthoquinone 7 (96%; 24% overall from commercial reagents). Though we found in exploratory studies that hydronaphthoquinones related to 7 could be prepared by adaptation of our earlier work, the overall yield was low (4%), and the route was not amenable to scale-up (see Figure S2).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the Naphthalene Derivative 7

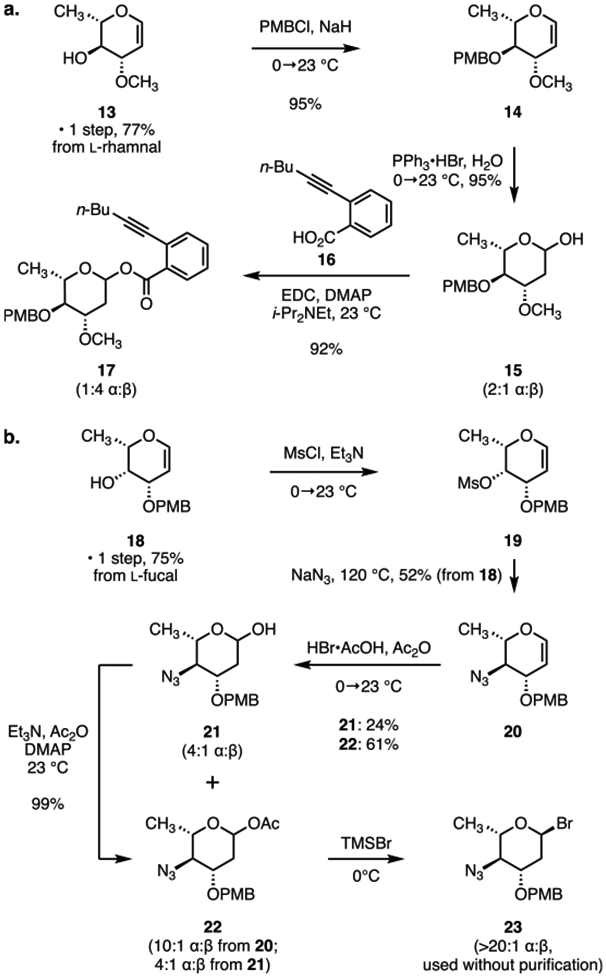

Two short routes to suitably protected forms of the l-oleandrose and N,N-dimethyl-l-pyrrolosamine carbohydrate donors were developed for the synthesis of 3 (Scheme 2). The oleandrose donor 17 was prepared in three steps from the glycal 13 (obtained in one step and 77% yield from l-rhamnal, Scheme 2a).15 The C4 hydroxyl group was protected as the corresponding p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) ether 14 (PMBCl, sodium hydride, 95%). Acid-catalyzed hydration of the glycal (triphenylphosphine─hydrogen bromide complex, aqueous tetrahydrofuran) generated the reducing sugar 15 (95%, 2:1 mixture of α and β anomers). Finally, the reducing sugar was coupled with 2-(hex-1-yn-1-yl)benzoic acid (16) using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) as promoter to afford the donor 17 in 92% yield and as a 1:4 mixture of α and β diastereomers.

Scheme 2.

(a) Synthesis of the Protected l-Oleandrose Derivative 17; (b) Synthesis of the Protected l-Pyrrolosamine Derivative 23

The novel l-pyrrolosamine donor 23 was prepared by modification of a route developed by Shair and co-workers to protected pyrrolosamine derivatives (Scheme 2b).4d Treatment of the glycal 18 (obtained in one step and 75% yield from l-fucal)16 with methanesulfonyl chloride and triethylamine provided the C4-mesylate 19. Displacement of the sulfonate (sodium azide, N,N-dimethylformamide, 120 °C) then generated the azidoglycal 20 (52% from 18). Hydroacetoxylation of the glycal 20 using a mixture of acetic anhydride and hydrogen bromide in acetic acid generated a separable mixture of the reducing sugar 21 (24%, 4:1 mixture of α and β diastereomers) and the acetoxyglycoside 22 (61%, 10:1 mixture of α and β diastereomers). The purified reducing sugar 21 was converted to 22 by treatment with acetic anhydride (99%, 4:1 mixture of α and β diastereomers). Finally, deacetoxybromination of 22 (trimethylsilyl bromide)17 generated the l-pyrrolosamine donor 23 as a single detectable α-anomer (1H NMR analysis, H1: δ 6.06, d, J = 3.5 Hz). The deoxyglycosyl bromide 23 was unstable toward aqueous workup and purification. Accordingly, the product mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the unpurified donor was used immediately in the glycosylation step (see 26 → 4, Scheme 3).

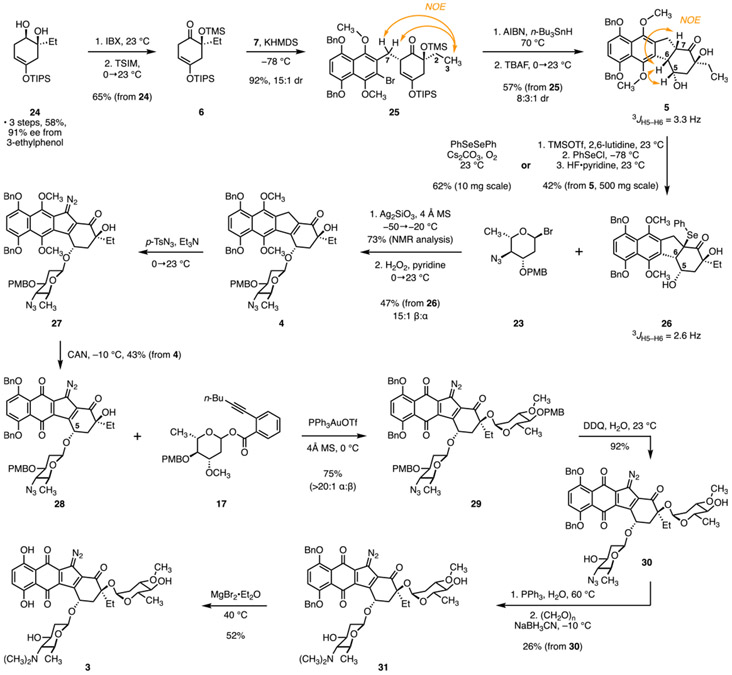

Scheme 3.

Preparation of the Ketone 6, Fragment Assembly, and Completion of the Synthesis of 3

The preparation of the ketone 6 and assembly of the fragments is depicted in Scheme 3. Beginning with the diol 24 (prepared in three steps, 58% yield, and 91% ee from 3-ethylphenol),4j,o oxidation of the secondary hydroxyl group (2-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX)), followed by protection of the tertiary alcohol (trimethylsilylimidazole (TSIM)), generated the ketone 6 (65% from 24). In the key fragment coupling step, the α-alkylation product 25 was formed in 92% yield and as a 15:1 mixture of diastereomers (1H NMR analysis) by addition of potassium hexamethyldisilazide (KHMDS) to a mixture of the bromide 7 and the ketone 6 in tetrahydrofuran at −78 °C. The configuration of the major diastereomer was established by nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) analysis (see orange arrows). Heating of the fragment coupling product 25 in the presence of tri-n-butyltin hydride and 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) at 70 °C then generated the product arising from 5-exo-trig cyclization and reduction of the α-silyloxy radical, as an inseparable mixture of C5 and C6 diastereomers. The temperature of this step was carefully optimized to minimize the elimination of the trimethylsilyloxy substituent. At higher temperatures, this elimination occurred readily from the product, while prolonged heating was required if the reaction was conducted at <70 °C, and elimination of this substituent from the starting material 25 was observed.

Following the removal of the silyl ether protecting groups (tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride, TBAF), the diol 5 was obtained as an 8:3:1 mixture of diastereomers. The mixture of diols could be separated by preparative thin-layered chromatography. NOE analysis of the most abundant product supported the relative configuration shown in structure 5 (see orange arrows for diagnostic NOEs). The relative stereochemistry of the minor diastereomers was not established. On preparative scales, the mixture of diastereomers was advanced without separation.

The α-phenylselenyl ketone 26 was obtained in 62% yield by treatment of the diastereomerically pure diol 5 with diphenyldiselenide and cesium carbonate under an oxygen atmosphere.18 The coupling constants between H5 and H6 were comparable in 26 and the diol 5 (2.6 and 3.3 Hz, respectively), suggesting that the cis ring fusion was maintained. Unfortunately, the yields of this transformation diminished on scale-up. Additionally, the separation of diol 5 from minor diastereomers was not feasible on >50 mg scales. To circumvent these issues, on preparative scales the mixture of 5 and minor diastereomers was exposed to excess trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate and 2,6-lutidine, which effected silylation of the secondary and tertiary hydroxyl groups with concomitant enoxysilane formation. Exposure of the unpurified enoxysilane to phenylselenyl chloride formed an α-(phenylselenyl)ketone (not shown). Removal of the silyl ether protecting groups (hydrogen fluoride─pyridine), followed by purification, then afforded the diol 26, free from minor diastereomers, in 42% yield (from 5).

The β-linked aminosugar was introduced by a modified Koenigs–Knorr glycosylation17 employing the α-bromide 23 as a donor. Thus, the expected β-glycoside was formed in 73% yield and as a 15:1 mixture of β and α diastereomers (1H NMR analysis) by addition of silver silicate to a mixture of 26 and 23 (5 equiv, prepared immediately before use) at −50 °C, followed by gradual warming to −20 °C. This product was unstable toward purification; consequently, the unpurified glycoside was treated directly with aqueous hydrogen peroxide to effect oxidation of the selenium and elimination to the benzoindene derivative 4 (47% from 26). Attempts to form the enone by ketone oxidation, or to introduce the carbohydrate residues to an enone-based acceptor, were unsuccessful (Figure S4). The selenide 26 was superior to a range of other acceptors we examined in this glycosylation step (Table S6).

After some experimentation (see Table S7), we found that a direct diazo transfer to 4 could be achieved by exposure to p-toluenesulfonyl azide and triethylamine in N,N-dimethylformamide. We are aware of only three isolated examples of diazo transfer to an indene,19 and the successful conversion of 4 to 27 suggests this transformation may be more general than appreciated. Because the diazohydronaphthoquinone 27 was unstable toward purification by flash-column chromatography, the unpurified product was oxidized with ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) to afford the diazoquinone 28 admixed with minor amounts of the C5 diastereomer, presumably arising from extended enolization of the cyclohexenone (43% from benzoindene 4). The diazoquinone 28 displayed a strong absorption at 2137 cm−1 in its infrared spectrum and a quaternary carbon at δ 73.5 ppm in its carbon-13 spectrum. These spectral features are diagnostic of the diazofluorene.2f

Extensive experimentation was required to identify conditions to introduce the l-oleandrose residue to 28 in high yield and α-selectivity (Table S8). Ultimately, gold-catalyzed activation of the alkynyl benzoate 17, as originally described by Yu and co-workers20 and used with great success by Nicolaou and co-workers in their studies toward 1,4s emerged as the most efficient approach among a range of donors and activators surveyed. Thus, the bis(glycoside) 29 was formed in 75% yield and with >20:1 α-selectivity by addition of (triphenylphosphine)gold trifluoromethanesulfonate to a mixture of the donor 17 and the acceptor 28 in dichloromethane at 0 °C. Removal of the PMB protecting groups (2,3-dichloro-4,5-dicyanobenzoquinone (DDQ)) generated the diol 30 (92%). Selective reduction of the azide in the presence of the diazofluorene was accomplished by treatment with triphenylphosphine in aqueous tetrahydrofuran. The resulting amine (not shown) was alkylated under reductive conditions (paraformaldehyde, sodium cyanoborohydride) to yield the N,N-dimethylamino-l-pyrrolosamine derivative 31 (26% from 30). Finally, the removal of the benzyl protecting groups (magnesium bromide diethyl etherate complex)21 furnished the target 3 (52%).

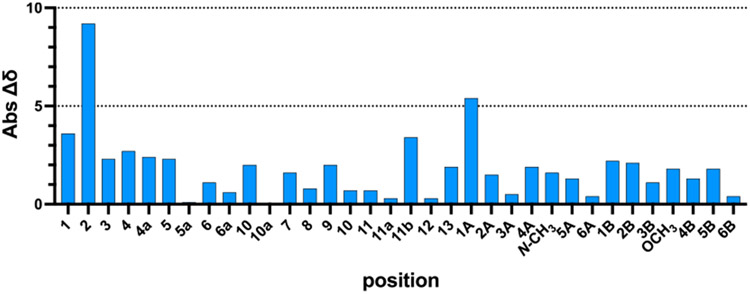

Carbon-13 NMR spectroscopic data for 3 were in agreement with those of (−)-lomaiviticin A (2), save for the C2 position, which differed by 9.2 ppm (Figure 2). This is not unexpected, given that this is the location of the bridging carbon─carbon bond in (−)-lomaiviticin A (2). The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) was 1.80 ppm across all positions (1.68 ppm excluding C2).

Figure 2.

Absolute difference between carbon-13 chemical shifts of the monomer 3 and (−)-lomaiviticin A (2). Spectroscopic data for 3 and 2 were obtained in dichloromethane-d2 and methanol-d4, respectively. Note: The positions 6/11, 6a/10a, 7/10, and 8/9 cannot be differentiated in 2 and 3 owing to the absence of long-range coupling and have been arbitrarily assigned. See Tables S9 and S11 for complete positional assignments.

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of the monomer 3 and (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) against K562 (leukemia), HCT116 (colon), LNCaP (prostate), and HeLa (cervical) cancer cell lines in short-term cell viability assays. (−)-Lomaiviticin A (2) possessed IC50 values in the 0.5–3 nM range against these four cell lines. By comparison, the monomer 3 was not cytotoxic at concentrations <1 μM. Prior studies of semisynthetic (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) established that the cytotoxic effects of the molecule derive from the induction of DSBs in DNA.3 These DSBs form via the sequential generation of reactive sp2 radicals at each diazo carbon.22 The monomer 3 cannot directly generate DNA DSBs, and this may underlie its diminished potency relative to 2. Interestingly, however, the kinamycins display IC50 values in the 70–500 nM range against the same cell lines,5a indicating there are differences between 3 and the kinamycins that further diminish activity.

In summary, we have described the synthesis of the bis(glycosylated) diazofluorene 3, which corresponds to the monomeric unit of (−)-lomaiviticin A (2). The newly devised route to this structure features a novel site- and stereoselective α-alkylation–radical cyclization strategy for construction of the carbon skeleton. Additionally, the route employs a direct diazo transfer to an electron-rich benzoindene, which may provide a general approach to related diazofluorene targets. Finally, we developed methods to introduce each 2-deoxyglycoside with high levels of stereocontrol and delineated a viable endgame strategy. Carbon-13 NMR spectroscopic data for 3 and (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) were found to be in agreement, providing further support for the recent structural revision of the natural isolate. Short-term viability assays reveal that the monomer 3 is nontoxic at concentrations <1 μM, underscoring the remarkable degree to which dimerization amplifies the toxicity of the diazofluorene, most likely by promoting the efficient production of DNA DSBs. The synthetic chemistry developed herein provides the key strategies and bond constructions (save for the bridging carbon─carbon bond) that are needed to prepare (−)-lomaiviticin A (2) by total synthesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS R35-GM131913 and the Chemistry–Biology Interface Training Program T32GM067543 to M.D.) and the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship to J.A.R.) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery for their assistance in running short-term cell viability assays. The Core is supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH P30 CA016359. Equipment and libraries were supported in part by the Program in Innovative Therapeutics for Connecticut’s Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c07631.

Detailed experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds (PDF)

Contributor Information

Zhi Xu, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States.

Mikaela DiBello, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States.

Zechun Wang, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States.

John A. Rose, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States; Present Address: Prelude Therapeutics Inc., Experimental Station E400/3213, 200 Powder Mill Rd, Wilmington, Delaware 19803, United States

Lei Chen, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States.

Xin Li, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States; Present Address: Incyte Research Institute, Incyte Corporation, 1801 Augustine Cut-Off, Wilmington, Delaware 19803, United States..

Seth B. Herzon, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States; Departments of Pharmacology and Therapeutic Radiology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).He H; Ding WD; Bernan VS; Richardson AD; Ireland CM; Greenstein M; Ellestad GA; Carter GT Lomaiviticins A and B, Potent Antitumor Antibiotics from Micromonospora lomaivitiensis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 5362–5363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) For reviews of the kinamycins and lomaiviticins, see: Gould SJ Biosynthesis of the Kinamycins. Chem. Rev 1997, 97, 2499–2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marco-Contelles J; Molina MT Naturally Occurring Diazo Compounds: The Kinamycins. Curr. Org. Chem 2003, 7, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar]; (c) Arya DP Diazo and Diazonium DNA Cleavage Agents: Studies on Model Systems and Natural Product Mechanisms of Action. Top. Heterocycl. Chem 2006, 2, 129–152. [Google Scholar]; (d) Nawrat CC; Moody CJ Natural Products Containing a Diazo Group. Nat. Prod. Rep 2011, 28, 1426–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Herzon SB The Kinamycins. In Total Synthesis of Natural Products. At the Frontiers of Organic Chemistry; Li JJ; Corey EJ, Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp 39–65. [Google Scholar]; (f) Herzon SB; Woo CM The Diazofluorene Antitumor Antibiotics: Structural Elucidation, Biosynthetic, Synthetic, and Chemical Biological Studies. Nat. Prod. Rep 2012, 29, 87–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Colis LC; Woo CM; Hegan DC; Li Z; Glazer PM; Herzon SB The Cytotoxicity of (−)-Lomaiviticin A Arises from Induction of Double-strand Breaks in DNA. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 504–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) For a review, see: Herzon SB The Mechanism of Action of (−)-Lomaiviticin A. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 2577–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) For synthetic studies toward structure 1, see: Freed JD Toward a Synthesis of the Lomaiviticins. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC; Denton RM; Lenzen A; Edmonds DJ; Li A; Milburn RR; Harrison ST Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Model Core Systems of Lomaiviticins A and B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 2076–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Krygowski ES; Murphy-Benenato K; Shair MD Enantioselective Synthesis of the Central Ring System of Lomaiviticin A in the Form of an Unusually Stable Cyclic Hydrate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 1680–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morris WJ; Shair MD Stereoselective Synthesis of 2-Deoxy-β-glycosides Using Anomeric O-Alkylation/Arylation. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang W; Baranczak A; Sulikowski GA Stereocontrolled Assembly of the C3/C3′ Dideoxy Core of Lomaiviticin A/B and Congeners. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 1939–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gholap SL; Woo CM; Ravikumar PC; Herzon SB Synthesis of the Fully Glycosylated Cyclohexenone Core of Lomaiviticin A. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 4322–4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nicolaou KC; Nold AL; Li H Synthesis of the Monomeric Unit of the Lomaiviticin Aglycon. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 5860–5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Lee HG; Ahn JY; Lee AS; Shair MD Enantioselective Synthesis of the Lomaiviticin Aglycon Full Carbon Skeleton Reveals Remarkable Remote Substituent Effects During the Dimerization Event. Chem.—Eur. J 2010, 16, 13058–13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Morris WJ; Shair MD Synthesis of the N-(tert-Butyloxycarbonyl)-O-triisopropylsilyl-D-pyrrolosamine Glycal of Lomaiviticins A and B via Epimerization of L-Threonine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 4310–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Herzon SB; Lu L; Woo CM; Gholap SL 11-Step Enantioselective Synthesis of (−)-Lomaiviticin Aglycon. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7260–7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Scully SS; Porco JA Asymmetric Total Synthesis of the Epoxykinamycin FL-120B′. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 9722–9726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Baranczak A; Sulikowski GA Synthetic Studies Directed toward Dideoxy Lomaiviticinone Lead to Unexpected 1,2-Oxazepine and Isoxazole Formation. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 1027–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Feldman KS; Selfridge BR Enantioselective Synthesis of the ent-Lomaiviticin A Bicyclic Core. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 5484–5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Scully SS; Porco JA Studies Toward the Synthesis of the Epoxykinamycin FL-120B′: Discovery of a Decarbonylative Photocyclization. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 2646–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Woo CM; Gholap SL; Lu L; Kaneko M; Li Z; Ravikumar PC; Herzon SB Development of Enantioselective Synthetic Routes to (−)-Kinamycin F and (−)-Lomaiviticin Aglycon. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 17262–17273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Feldman KS; Selfridge BR Synthesis Studies on the Lomaiviticin A Aglycone Core: Development of a Divergent, Two-directional Strategy. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 4499–5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (q) Lee AS; Shair MD Synthesis of the C4-Epi-Lomaiviticin B Core Reveals Subtle Stereoelectronic Effects. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2390–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Rose JA; Mahapatra S; Li X; Wang C; Chen L; Swick SM; Herzon SB Synthesis of the Bis(cyclohexenone) Core of (−)-Lomaiviticin A. Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 7462–7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (s) Nicolaou KC; Chen Q; Li R; Anami Y; Tsuchikama K Total Synthesis of the Monomeric Unit of Lomaiviticin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 20201–20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (t) Kaneko M; Li Z; Burk M; Colis L; Herzon SB Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of (2S,2′S)-Lomaiviticin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 1126–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Woo CM; Beizer NE; Janso JE; Herzon SB Isolation of Lomaiviticins C─E, Transformation of Lomaiviticin C to Lomaiviticin A, Complete Structure Elucidation of Lomaiviticin A, and Structure–Activity Analyses. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 15285–15288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kersten RD; Lane AL; Nett M; Richter TKS; Duggan BM; Dorrestein PC; Moore BS Bioactivity-Guided Genome Mining Reveals the Lomaiviticin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster in Salinispora tropica. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 955–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kim LJ; Xue M; Li X; Xu Z; Paulson E; Mercado B; Nelson HM; Herzon SB Structure Revision of the Lomaiviticins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 6578–6585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).The structure elucidation of the kinamycins was also challenging. The metabolites were originally advanced as N-cyano carbazoles. See refs 2.

- (8).Figure S1 provides a summary of our prior route to the monomeric structure related to 1.

- (9).Figures S2 and S3 provide a summary of the prior route and its attempted application to 3.

- (10).For a review of fragment couplings by carbon─carbon bond formation, see: Tomanik M; Hsu IT; Herzon SB Fragment Coupling Reactions in Total Synthesis That Form Carbon─Carbon Bonds via Carbanionic or Free Radical Intermediates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 1116–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For a review of 2-deoxyglycoside synthesis, see: Bennett CS; Galan MC Methods for 2-Deoxyglycoside Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 7931–7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Couladouros EA; Strongilos AT Synthesis of Hydroxylated Naphthoquinone Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2002, 3341–3350. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Deville JP; Behar V Tandem Conjugate Cyanide Addition–Dieckmann Condensation in the Synthesis of the ABCD-Ring System of Lactonamycin. Org. Lett 2002, 4, 1403–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sakata J; Ando Y; Ohmori K; Suzuki K Synthetic Study on Naphthospironone A: Construction of Benzobicyclo[3.2.1]octene Skeleton with Oxaspirocycle. Org. Lett 2015, 17, 3746–3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tolman RL; Peterson LH A Convenient, High-yield Synthesis of L-Oleandrose and L-Oleandra. Carbohydr. Res 1989, 189, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Thiem J; Klaffke W Facile Stereospecific Synthesis of Deoxyfucosyl Disaccharide Units of Anthracyclines. J. Org. Chem 1989, 54, 2006–2009. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kaneko M; Herzon SB Scope and Limitations of 2-Deoxy and 2,6-Dideoxyglycosyl Bromides as Donors for the Synthesis of β-2-Deoxy and β-2,6-Dideoxyglycosides. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 2776–2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhu J, Zhang C, Liu L, Xue C, Cai Y, Liu X-Y, Xue F, Qin Y Total Synthesis of Sarpagine Alkaloid (−)-Normacusine B. Org. Lett 2022, 24, 3515–3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Rewicki D; Tuchscherer C 1-Diazoindene and Spiro[indene-1,7′-norcaradiene]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1972, 11, 44–45. [Google Scholar]; (b) Djukic J-P; Michon C, Heiser D; Kyritsakas-Gruber N; de Cian A; Dötz KH; Pfeffer M The Reaction of Diazocyclopentadienyl Compounds with Cyclomanganated Arenes as a Route to Ligand-Appended Cymantrenes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2004, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar]; (c) Green SP; Payne AD; Wheelhouse KM; Hallett JP; Miller PW; Bull JA Diazo-Transfer Reagent 2-Azido-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine Displays Highly Exothermic Decomposition Comparable to Tosyl Azide. J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 5893–5898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Li Y; Yang Y; Yu B An Efficient Glycosylation Protocol with Glycosyl ortho-Alkynylbenzoates as Donors Under the Catalysis of Ph3PAuOTf. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 3604–3608. [Google Scholar]; (b) For a recent review, see: Li Y; Yang X; Liu Y; Zhu C; Yang Y; Yu B Gold(I)-Catalyzed Glycosylation with Glycosyl ortho-Alkynylbenzoates as Donors: General Scope and Application in the Synthesis of a Cyclic Triterpene Saponin. Chem.—Eur. J 2010, 16, 1871–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tanc M; Carta F; Scozzafava A; Supuran CT 6-Substituted 1,2-Benzoxathiine-2,2-dioxides are Isoform-selective Inhibitors of Human Carbonic Anhydrases IX, XII and VA. Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Xue M; Herzon SB Mechanism of Nucleophilic Activation of (−)-Lomaiviticin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15559–15562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.