Abstract

This is a unique case report of a 67-year-old female diagnosed with multiple myeloma and extensive use of intravenous bisphosphonate whose clinical and radiographic presentation of an oral lesion made it challenging to confirm its definitive diagnosis. This patient was referred to the dental service for a suspected medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clinically, the lesion was located underneath a fixed partial denture in the left posterior mandible. There was a purulent swelling on the lingual side of the fixed partial denture, and a hyperplastic exophytic lesion on the buccal side of the bridge. Panoramic radiograph showed a well circumscribed radiolucent lesion in the left mandible. A biopsy of the gingival lesion on the buccal aspect was inconclusive. As the positron emission tomography scan showed lytic lesions, oral manifestation of multiple myeloma could not be ruled out. A computed tomography guided biopsy of the left mandible showed plasma cell neoplasm in the histological analysis. Upon confirmed diagnosis, the patient was treated with 20Gy to the left mandible and subsequent debridement of the loose necrotic bone. Following treatment, this gingival lesion resolved completely, and the tumor has remained stable till date.

Keywords: Bisphosphonate, medication related osteonecrosis of jaw, multiple myeloma, oral lesion, osteonecrosis

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a common hematological malignancy characterized by a proliferation of atypical plasma cells in the bone marrow.1 Currently, there is no cure. Treatment approaches are directed to relieve pain and to slow the progression of the disease, including treatments such as stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy, and the implementation of novel agents such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, and bortezomib.2 In MM, the bones can be involved relatively early, resulting in skeletal-related events (SRE) such as spinal cord compression and pathologic bone fractures. In these cases, the incorporation of bisphosphonates has demonstrated favorable outcomes. Zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce SRE with possible anti-tumor effect, improving the overall survival rate of patients with MM.3 Oral manifestations associated with multiple myeloma (OM) are rare and often signifies a poor prognosis as it is typically indicative of a widespread disease.4,5 The incidence of radiographic OM in the mandible has been reported as 5.18%.6 Once OM is diagnosed, palliative treatment with localized radiation therapy, systemic chemotherapy, or a combination of these can significantly improve and maintain patient’s quality of life. We describe a case of atypical OM with clinical and radiographic presentation closely resembling medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) which made it challenging to confirm its definitive diagnosis. MRONJ is a well-known complication in patients with current or history of antiresorptive or antiangiogenic medication, commonly presenting as exposed bone or bone that can be probed in the maxillofacial region through an intraoral or extraoral fistula that has persisted for more than 8 weeks, and without any history of radiation therapy to the jaws or obvious sign of jaw metastasis.7 Upon confirmed diagnosis, it was managed well with conservative treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old Caucasian woman with history of ISS stage III free lambda light chain MM was referred to the dental service by her medical oncologist on February 2018. The patient reported with a chief complaint of gingival lesion and associated mild discomfort in the left posterior mandible in the past one week. Her current diagnosis was significant for MM in remission for which she underwent autologous stem cell transplant in 2013. She was also administered 28 dosages of zoledronic acid between 2013 and 2016.

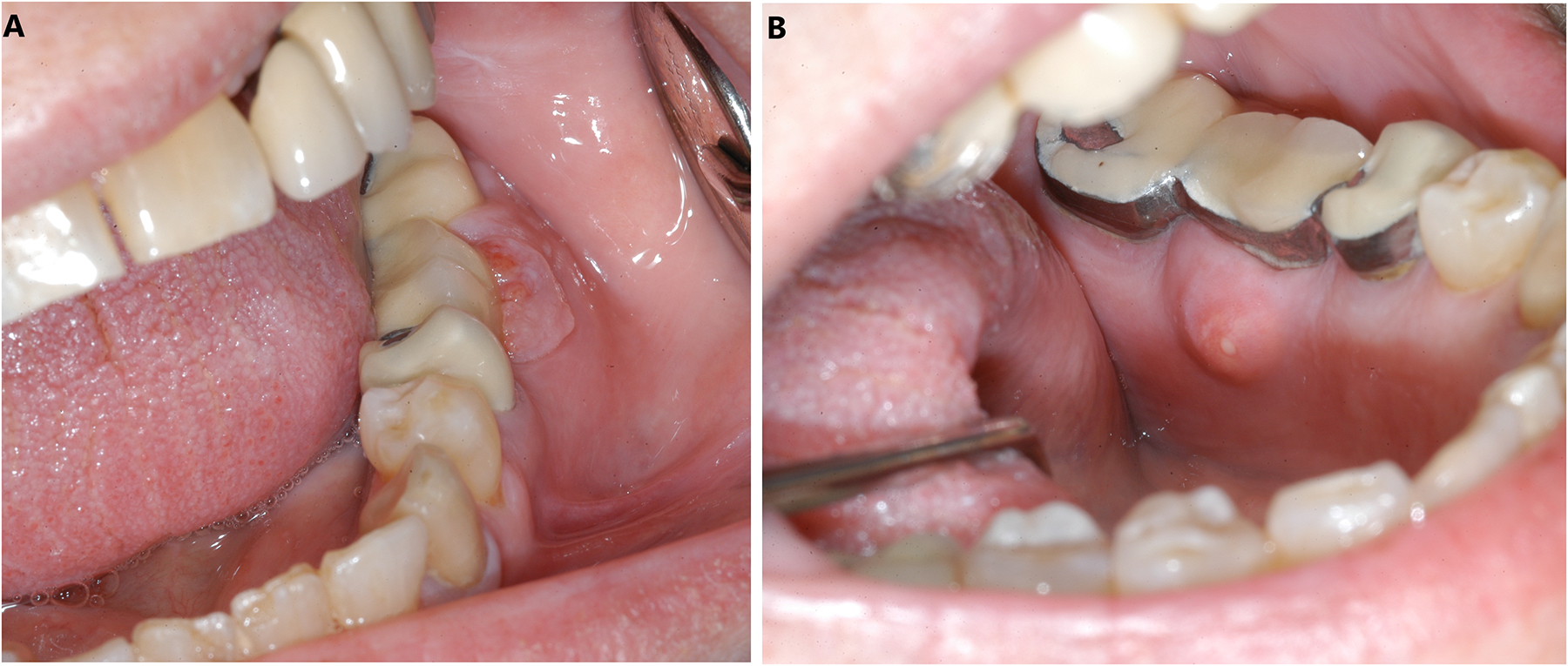

Extra-oral examination was within normal limits. Intra-oral examination revealed a gingival lesion buccal and lingual to her fixed partial denture in the left posterior mandibular region. The overlying mucosa on the buccal aspect of the fixed partial denture appeared hyperplastic and exophytic while the lesion on the lingual aspect exhibited a smooth surface purulent swelling (Figure 1). The patient exhibited good oral hygiene with stable dentition. A periapical radiograph of the region showed a well-defined radiolucent lesion between the roots of mandibular left second molar and first premolar (teeth #37 and #35, respectively). Panoramic radiographic revealed a non-corticated, well-circumscribed radiolucent lesion in the left posterior mandible underneath the pontic of the left first molar in the mandible (tooth #36) (Figure 2A). There was no evidence of active dental infection. Due to the patient’s history of bisphosphonate treatment, MRONJ was considered as one of the differential diagnosis. However, due to the clinical appearance of the exophytic lesion involving the buccal gingiva that was deemed atypical for MRONJ, a soft-tissue biopsy was performed. Histological analysis showed granulation tissue, squamous mucosa with epithelial hyperplasia, and polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells, small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils.

Figure 1:

(A) Buccal view of the fixed partial denture showing hyperplastic and exophytic lesion (B) Lingual view showing purulent swelling in the left mandibular posterior region.

Figure 2:

Panoramic radiographic (A) Shows a unilocular radiolucent in the left posterior mandible at the patient’s initial visit. (B) Shows evidence of bony healing in the left posterior mandibular area following radiation therapy. (C) Shows well circumscribed multinodular radiolucency involving the left mandibular posterior region on follow up after 14 months.

Diagnostic imaging with positron emission tomography- computed tomography (PET-CT) scan revealed a hypermetabolic lytic lesion of the left mandible, possibly suggestive of MRONJ. However, myelomatous lytic lesions were also observed on the axial and appendicular skeleton. Therefore, differential diagnosis of OM could not be ruled out. Further investigation with a CT-guided biopsy of the mandible was performed which revealed plasma cell neoplasm (Figure 3). Upon confirmed diagnosis, the patient underwent 10 sessions of 200 centi-gray of radiation therapy to the left mandible (Figure. 4). She reported improved levels of comfort in the area immediately following radiation therapy. A follow-up PET- CT scan after 6 months showed decreased activity of the lesion on the left mandible with increased erosion of the lingual and buccal cortices. A post radiation panoramic radiograph revealed evidence of bony healing in the left mandible (Figure 2B).

Figure 3:

Histopathological examination from CT-guided needle biopsy of the left posterior mandible shows cortical bone and fibrous tissue. Focally, there is an atypical infiltrate positive for CD-138, B-cell maturation antigen and lambda light chain.

Figure 4:

A CT slide illustrating the radiation treatment plan and dose distribution in the area of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Seven months following radiation therapy, an area of exposed mobile bone was noted on the buccal aspect of the pontic tooth #36. The patient remained free of oral symptoms. The gingiva surrounding the exposed bone appeared healthy with no erythema, edema, or purulence (Figure 5A, 5B). To facilitate the removal of the exposed bone, pontic #36 was sectioned and detached from abutments (Figure 5C). The bony sequestrum measuring 1.5cm by 1cm was gently removed with a pickup instrument (Figure 5D). A 14-month follow up shows a well keratinized pink gingiva over the residual ridge between teeth #37 and #35 and complete soft tissue closure (Figure 6) while a panoramic radiograph reveals well circumscribed multinodular radiolucency involving the left mandibular posterior region (Figure 2C).

Figures 5:

(A) Buccal view of left mandibular posterior region (B) Lingual view of gingiva seven months following radiation therapy (C) Prominently exposed bone after the removal of pontic in the mandibular left posterior region (D) Bony spicule measuring 1.5 × 1.0 cm was removed using pick-up instrument.

Figure 6:

Complete gingival healing of the exposed bony site 14 months following sequestrectomy.

DISCUSSION

Distinguishing between OM and MRONJ is a clinical challenge due to their variable and similar clinical and radiographic features. MRONJ, previously known as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ), was first recognized as a pathological entity in 2003 by Marx.8 Later, other classes of medications besides bisphosphonates namely denosumab, bevacizumab, and sunitinib were also found to be associated with the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Radiographic presentation of MRONJ is often correlated with advanced stage of the disease entity. Case reports have described osseous sclerosis of varying degrees as a main radiographic feature of MRONJ.9 MRONJ was once described as “bisphosphonate associated osteopetrosis” to highlight the sclerotic changes.10 A CT scan offers advantage over panoramic radiographs in detecting radiographic changes in MRONJ and presents as cortical perforation, periosteal reaction, and/or bone deposition.11 Management strategies in patients with MRONJ remain controversial. Minimizing risk for MRONJ with thorough dental evaluation prior to starting of anti-resorptive medication remains a key.12 Once MRONJ has been diagnosed, different therapeutic strategies targeted to control superinfection include antimicrobial rinses such as chlorhexidine gluconate and/or antibiotic therapy.13 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the utilization of pentoxifylline and tocopherol may be effective by increasing vascularity to the area of bone necrosis.14 Conservative surgery such as sequestrectomy and/or superficial debridement of sequestrum, and surgical resection of necrotic area can also be performed depending on MRONJ stage.7,15 Additional existing treatment modalities with inconsistent results include the utilization of low-level laser therapy, hyperbaric oxygen.16,17

Radiographic and clinical features of OM are non-distinct and variable, making early diagnosis a challenge. Radiographic features of OM can be solitary or multiple, have diffuse or well circumscribed borders, and can have sclerotic, osteolytic, osteoporotic, or mixed radiolucency appearance, with or without cortical destruction.18 If the maxillary sinus is involved, it may present with mucoperiosteal thickening.19 Radiographic features of OM has further been reported to be compounded by the effect of anti-resorptive therapy. One study reported that bisphosphonate can decrease the presence of solitary osteolytic lesions and increase lamina dura abnormalities.18 Clinical features of OM have also been documented to be difficult to discern. OM has been reported as extraoral swelling5, non-healing extraction socket20, cortical expansion19, exophytic gingival mass21, paresthesia22 and/or fistula through which bone can be probed.22 Unlike MRONJ, OM does not require exposed bone for diagnosis.5

When there is high suspicion for OM, histological analysis from gingival and/or bony biopsy is warranted. Clinicians however must weigh the benefits of the biopsy with the risk for development of MRONJ. Currently, there is no guideline to differentiate between MRONJ from MO. Although there are a fair number of case reports which describes MRONJ in MM patients treated with bisphosphonate23, a limited number of case reports illustrate the challenge in characterizing the clinical and radiographic findings of patients who may have MRONJ, MO, or a combination of two disease entities. The patients in these case reports were on zoledronic acid and the true diagnosis was confirmed with hard or soft tissue biopsy.22 In the present case report, the presence of an exophytic and hyperplastic gingival lesion was atypical and unusual for an MRONJ lesion. A collaboration between the medical and dental oncologists as well as clinical judgment were crucial in the decision to proceed with biopsy to confirm the diagnosis for metastatic disease. Timely diagnosis and subsequent local radiation therapy resulted in resolution of the patient’s symptoms and local control of the metastatic site.

CONCLUSION

Differentiating OM from MRONJ is challenging because of the similarity in their clinical and radiographical presentation. The healthcare provider must be aware of MRONJ as a condition that can potentially obscure oral metastasis and vice versa. Early diagnosis is crucial to facilitate early intervention and alleviate the patients’ symptoms and achieve local control. A tissue biopsy should be considered when OM is suspected. Oral health care professionals are placed in a strategic position in patient care for early diagnosis of such oral manifestation associated with multiple myeloma.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12): e538–e548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Röllig C, Knop S, Bornhäuser M. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2197–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang X, Yan X, Li Y. A meta-analysis of the antitumor effect and safety of bisphosphonates in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):6743–6754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Moura LB, Gabrielli MF, Gabrielli MA, Filho VA. Pathologic Mandibular Fracture as First Sign of multiple myeloma. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(2): e138–e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Junquera S, Álvarez-Yagüe E, Junquera L, Ugalde R, Rúa L. Multiple myeloma and chemical maxillary osteonecrosis. Can both occur simultaneously? [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 18]. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019; S2468–7855(19)30288–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lambertenghi-Deliliers G, Bruno E, Cortelezzi A, Fumagalli L, Morosini A. Incidence of jaw lesions in 193 patients with multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65(5):533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update [published correction appears in J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015 Jul;73(7):1440] [published correction appears in J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015 Sep;73(9):1879]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(10):1938–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1115–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Phal PM, Myall RW, Assael LA, Weissman JL. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(6):1139–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(11):1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guo Y, Wang D, Wang Y, Peng X, Guo C. Imaging features of medicine-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: comparison between panoramic radiography and computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2): e69–e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Owosho AA, Liang STY, Sax AZ, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An update on the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center experience and the role of premedication dental evaluation in prevention. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(5):440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Reduction of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) after implementation of preventive measures in patients with multiple myeloma treated with zoledronic acid. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(1):117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Owosho AA, Estilo CL, Huryn JM, Yom SK. Pentoxifylline and tocopherol in the management of cancer patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: an observational retrospective study of initial case series. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(4):455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stockmann P, Vairaktaris E, Wehrhan F, et al. Osteotomy and primary wound closure in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a prospective clinical study with 12 months follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vescovi P, Meleti M, Merigo E, et al. Case series of 589 tooth extractions in patients under bisphosphonates therapy. Proposal of a clinical protocol supported by Nd:YAG low-level laser therapy. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(4): e680–e685. Published 2013 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Freiberger JJ, Padilla-Burgos R, Chhoeu AH, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment and bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(7):1321–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Faria KM, et al. , Radiographic patterns of multiple myeloma in the jawbones of patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Am Dent Assoc, 2018. 149(5): p. 382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Katkar RA, et al. , Multiple myeloma in bisphosphonate affected jaws-a diagnostic challenge: Case Report. Quintessence International, 2014. 45(7): p. 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Palakshappa SG, et al. , Multiple myeloma presenting as an unhealed extraction socket: Report of a case with brief review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol, 2018. 22(2): p. 284.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shah A, Ali A, Latoo S, Ahmad I. Multiple myeloma presenting as Gingival mass. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;9(2):209–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tsunematsu K, Kanno T, Sekine J. A case of recurrent multiple myeloma showing clinical features similar to medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and Pathology. 2016;28(5): 434–437. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Infante Cossío P, Cabezas Macián A, Pérez Ceballos JL, Palomino Nicas J, Gutiérrez Pérez JL. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(1): E52–E57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]