Abstract

A brainstem syndrome is recognizable in patients presenting with a combination of visual disturbances, incoordination, gait problems, speech and swallowing difficulties, and new-onset sleep symptomatology. Brainstem disorders of subacute onset (onset and progression with accumulation of disabling deficits in 6–12 weeks) are generally of autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, or infiltrative neoplastic cause. An autoimmune or infectious brainstem disorder may be referred to as brainstem encephalitis or rhombencephalitis. We describe a patient with paraneoplastic autoimmune rhombencephalitis, in whom diagnostic clues included the following: diverse visual and sleep symptoms, trismus, and choking in the history; see-saw nystagmus, opsoclonus, dysarthria, jaw dystonia, and episodic laryngospasm on examination; subtle but longitudinal and nonenhancing T2 MRI abnormalities in the brainstem and upper cervical cord; and oligoclonal bands in the CSF. His movement disorder–specific neural IgG profile revealed ANNA-2 (anti-Ri) and KLHL-11-IgG. Both are biomarkers of paraneoplastic brainstem encephalitis. KLCHL-11-IgG has been reported to accompany germ cell tumors, which was found in a solitary metastasis to the left inguinal lymph node in our patient, along with an atrophic left testis. Multidisciplinary treatment (autoimmune neurology, sleep medicine, ophthalmology, and physiatry) led to significant clinical improvements. This case provides a framework for the evaluation of patients with subacute-onset brainstem syndromes and the investigation and management of those with paraneoplastic and other autoimmune diseases.

Section 1

A 43-year-old man, with previous left testicular torsion, presented with 2 weeks of imbalance, gait incoordination, double and blurred vision, vertigo, and right lower extremity weakness. He denied confusion, disorientation, or associated memory issues. Observed eye movement abnormalities and ataxia on initial evaluation, and elevated white cell count and protein in the CSF, led to a Miller Fisher syndrome diagnosis. He was treated with IVIg, accompanied by improvement in vertigo. Eight weeks later, diplopia and oscillopsia occurred, and he had jaw opening difficulties and clenching episodes (trismus) and hypersialorrhea. He required pureed diet and subsequently gastrostomy tube for nutrition. He developed severe daytime hypersomnolence and sleep-related complex motor behaviors, with violent, thrashing limb movements and screaming and shouting vocalizations. He was briefly hospitalized after a possible isolated seizure, though never confirmed (EEG did not reveal epileptiform discharges). Sixteen weeks into his illness, he developed choking episodes, nocturnal stridor, and hypoxia. He was hospitalized again. He developed acute respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation.

On examination, he had horizontal plane ophthalmoplegia (not overcome with vestibular ocular reflex), esotropia, jerk see-saw vertical nystagmus (Video 1), and superimposed opsoclonic bursts (Video 2). He experienced mixed flaccid hyperkinetic dysarthria and jaw-closing dystonia (Video 2). He experienced oral phase and pharyngeal dysphagia. He was wheelchair bound, only taking steps with a walker and maximum assistance. He had moderate upper extremity dysmetria (minimal in the lower extremities) and normal limb tone and strength. Jaw jerk and deep tendon reflexes were brisk, and sensory examination was normal. Hoffman and Babinski signs were negative. A left inguinal mass was detected. Episodic shortness of breath accompanied by cyanosis (laryngospasm) was noted. Tracheostomy placement precluded polysomnographic studies.

Jerk see-saw nystagmus, observed when the patient was in ICU early on in his illness. Cyclically, and with a jerky appearance, 1 eye rises and intorts, as the other falls and extorts, followed by reversal of the same movements.Download Supplementary Video 1 (4.4MB, mov) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200950_Video_1

Three sequential video segments demonstrating bursts of opsoclonus, dysarthria, and jaw-closing dystonia and trismus.Download Supplementary Video 2 (7.8MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200950_Video_2

Questions for Considerations:

What is the significance of symptom onset and progression?

Where do the symptoms and signs localize to?

What is the differential diagnosis?

What tests would you perform?

Section 2

The onset and progression leading to significant disability within 6–12 weeks is consistent with a subacute disorder.1 The age at onset and progression rate is atypical for hereditary disease and degenerative CNS diseases (except for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, where ataxia could be prominent and progress rapidly).

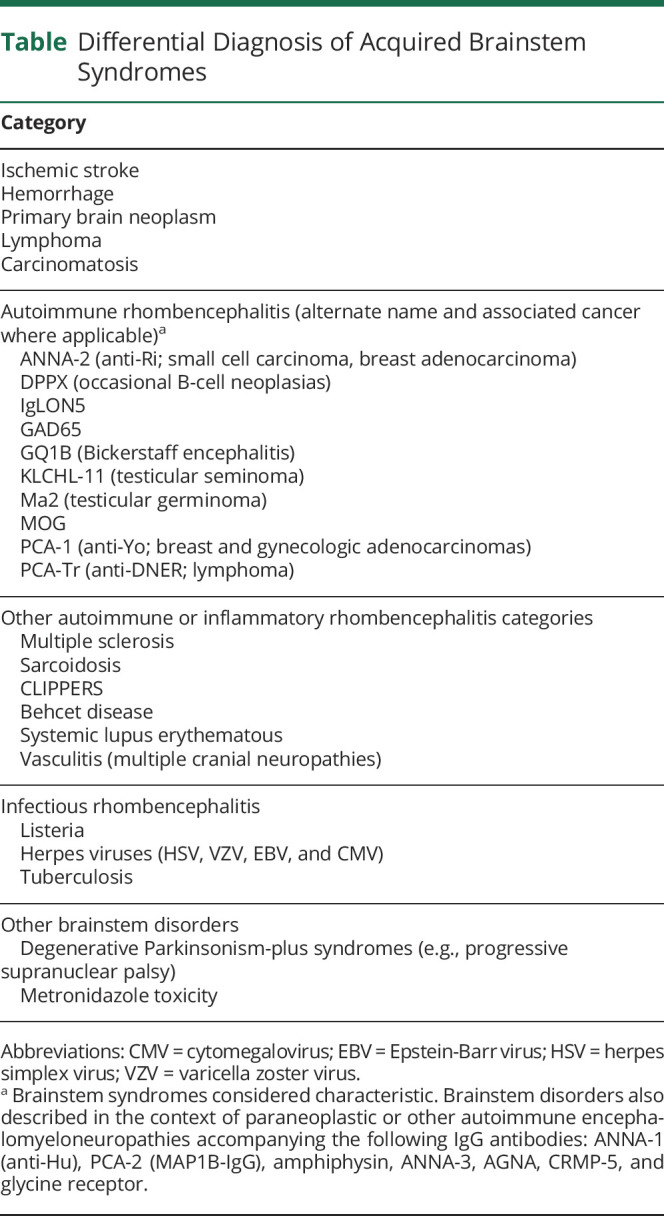

While the gait and balance difficulties and extremity weakness do not localize well, the bilateral horizontal gaze palsies with opsoclonus, jerk see-saw nystagmus, laryngospasm, jaw dystonia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and probable REM sleep behavior disorder assist in brainstem syndromic localization. Jerk see-saw nystagmus localizes to either medulla or mesodiencephalon, whereas pendular see-saw nystagmus localizes to the brainstem-mesodiencephalic junction.2 A possible seizure suggested CNS multifocality, although this event could have represented hyperekplexia or generalized dystonic posturing with brainstem localization. While subacute peripheral nervous system disorders such as myasthenia gravis, Lambert-Eaton syndrome, and Miller Fisher syndrome were considered, they were excluded because of the presence of CNS signs and absence of fatigable weakness and autonomic and neuropathic signs. A brainstem disorder was the appropriate localizing syndrome. Differential diagnostic considerations for subacute onset brainstem disorders include toxic, infectious, neoplastic, inflammatory, and autoimmune causes (Table). Opsoclonus (with or without myoclonus) is rarely encountered beyond immune-mediated etiologies.3

Table.

Differential Diagnosis of Acquired Brainstem Syndromes

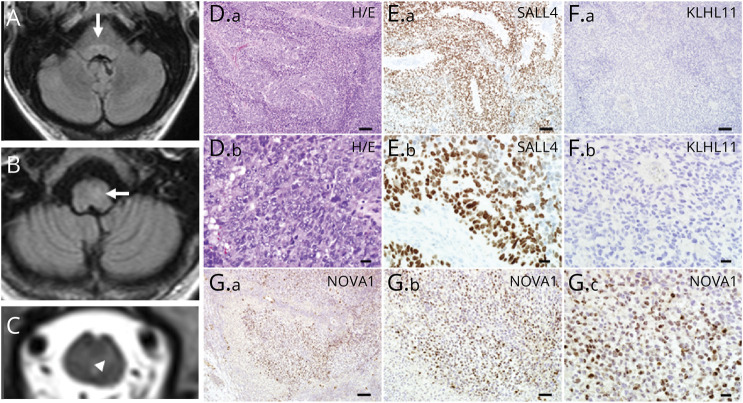

A comprehensive evaluation including blood tests, MRI imaging, CSF analysis, and EEG was undertaken. General tests (complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, fasting glucose, C-reactive protein, liver function tests, urinalysis, and chest x-ray) showed normal results. Second-line blood tests also showed normal results (vitamin B12, methylmalonic acid, folate, antinuclear antibody with connective tissue disease cascade, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis panel, and celiac disease serology). Discreet, longitudinally extensive T2 hyperintensities in the pontine and medullary tegmentum, extending into the cervical cord (Figure, A–C), without mass effect, without enhancement has been reported in paraneoplastic disorders.3 Typical features of demyelinating disease and CLIPPERs (pontine perivascular enhancement) were absent.4 CSF studies revealed 37 white blood cells/μL (normal, <5/μL, 92%), lymphocyte-predominant, protein of 59 (normal, ≤35 mg/dL), normal glucose, normal IgG index and synthesis rate, and 4 CSF-exclusive oligoclonal bands (normal, <2). An elevated white cell count could also be encountered in infectious meningoencephalitis, but CSF-exclusive oligoclonal bands (or elevated CSF kappa free light chains) are indicative of CNS inflammation.5 In addition, gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic cultures, and cytology showed negative results. CSF tests for herpes viruses, Lyme disease, and listeria also showed negative results. EEG exhibited diffuse, generalized, nonspecific slowing. Left groin ultrasound revealed atrophic testis and enlarged lymph node. CT of the whole body did not reveal malignancy.

Figure. Radiologic and Tumor Histopathologic Findings.

MRI brain (T2 FLAIR) and cervical cord (T2) reveal T2 hyperintensity in pontine (A) and medullary tegmentum (B), arrows, which extended to the upper cervical cord (C). (D.a) The left inguinal lymph node biopsy from the 43-year-old man with testicular mass shows metastatic neoplastic components (hematoxylin and eosin stain). The tumor cells present variable morphologies. Most of the tumor cells show a large nucleus with prominent nucleoli (D.b, enlarged view of D.a). (E.a) Immunohistochemistry shows marked SALL4 immunoreactivity in the tumor cells, which is consistent with germ cell tumor (enlarged view in E.b). (F.a) The tumor cells show no KLHL11 immunoreactivity (enlarged view in F.b). (G.a) Tumor cells demonstrate marked NOVA1 immunoreactivities in the nuclei (enlarged views in G.b and G.c). Scale bars: 100 µm (D.a, E.a, F.a, G.a), 50 µm (G.b), and 20 µm (D.b, E.b, F.b, G.c).

Questions for Considerations:

What additional testing would you obtain to determine the diagnosis?

Section 3

The subacute onset, syndromic features, and inflammatory CSF made the term rhombencephalitis appropriate. The presence of opsoclonus, the groin mass, the tractopathy MRI findings, and CSF-exclusive oligoclonal bands made an autoimmune paraneoplastic cause most likely. A profile of neural antibodies pertinent to paraneoplastic and other autoimmune movement disorders was requested in serum (Table), revealing antineuronal nuclear antibody type-2 (ANNA-2, or anti-Ri) and kelch-like protein 11 (KLCHL11)-IgG. An excisional biopsy of the left inguinal lymph node revealed neoplastic components (Figure, D–G). Marked SALL4 reactivity was observed by immunohistochemistry, consistent with germ cell tumor. Marked NOVA1 (Ri, but not KLCHL-11) immunoreactivity was noted in the nuclei. PET-CT showed no evidence of retroperitoneal involvement. The patient underwent orchiectomy of the left testis (without additional chemotherapy). Pathology revealed a fibrotic testis surrounded by atrophic and sclerotic seminiferous tubules, without malignancy. Serial follow-up body imaging by FDG PET-CT over 1 year (and planned for 2 more) did not reveal cancer recurrence. Immune treatment (IV methylprednisolone 1 g weekly for 12 weeks and cyclophosphamide 1 g/m2 monthly for 6 months) was followed by near resolution of nystagmus and opsoclonus. Mobility gradually improved to the patient walking with a gait belt after 6 months of follow-up, with further rehabilitation planned. The esotropia was treated with a 25-prism diopter (base out) Fresnel prism, but the patient continued to experience significant horizontal gaze palsies. Jaw dystonia improved only marginally with a combination of botulinum toxin therapy, clonazepam, and tizanidine, and ongoing gastrostomy feeding support was required. The patient received noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with bilevel positive airway pressure for sleep-disordered breathing. The patient's probable REM sleep behavior disorder improved with nighttime clonazepam, and daytime sleepiness improved with methylphenidate.

Discussion

Paraneoplastic rhombencephalitis should be considered in patients with subacute onset of gait, coordination, visual, speech, and swallowing difficulties.1 Broadly, brainstem encephalitis may be ataxia-predominant (with accompanying vertigo and other visual symptoms) or may mimic atypical neurodegenerative parkinsonism with prominence of supranuclear gaze palsy, postural instability, and falls. Although infectious causes (such as listeriosis), neoplasia, and other inflammatory disorders (such as sarcoidosis) can present subacutely, brain imaging would generally demonstrate mass effect, basilar leptomeningeal or parenchymal enhancement. Other major categories can largely be excluded by their onset, hyperacute (stroke or hemorrhage) or insidious (such as primary brain tumor or progressive supranuclear palsy).

In addition to subacute onset and progression, clues to autoimmunity include opsoclonus (jaw-closing dystonia and laryngospasm, reported with ANNA-2, IgLON5, and KLCHL-11 antibodies).6-8 A locked jaw is also sometimes encountered in progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (usually glycine receptor antibody–positive).9 Sleep disorders and episodic laryngospasm are common in brainstem encephalitis and should be sought out and treated. Incipient symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing may be a harbinger of nocturnal respiratory arrest, particularly in Ma2 and IgLON5 autoimmunity.10,11 Early hearing loss is encountered in 40% of KLCHL-11 patients.8 Ataxia, vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus are more common with KLHL11 encephalitis than with Ma2 encephalitis. DPPX encephalitis may present with diarrhea and weight loss.12 Type 1 diabetes or thyroid disease and stiff-person phenomena may preexist or coexist in GAD65 autoimmunity.13 Some patients with paraneoplastic neurologic disorders may experience multifocal presentations, and different phenotypes can be encountered with most autoantibodies (such as IgLON5 autoimmunity, which may present with chorea, ataxia, or parkinsonian brainstem syndrome).7

A neural IgG profile assists in not only confirming an autoimmune diagnosis but also predicting cancer type in patients with a paraneoplastic cause. Typical accompaniments for ANNA-2 are breast adenocarcinoma or lung small cell carcinoma and for KLCHL-11, seminoma (testicular or extratesticular) and germ cell testicular neoplasms (as in our patient). KLHL-11 is less abundant than Ri protein, perhaps explaining the lack of tumor staining. Although the autoantibody diagnosis was made in serum, neurologic phenotype-specific autoantibody evaluations in both serum and CSF are generally recommended.1 The patient was at risk for testicular neoplasia, given the atrophic testis.14

Neural IgG profiles also inform treatment decisions and prognosis derived from previous clinical experience. For instance, DPPX-IgG potentially has pathogenic effects on binding to the extracellular domain of DPPX potassium channel subunit.15 Improvements in neurologic symptoms may occur on receiving antibody-depleting plasma exchange and rituximab.1 On the contrary, KLCHL-11 and Ri proteins are nuclear proteins and not accessible to the effects of IgGs. Rather, these IgGs seem to be biomarkers of CD8+ cytotoxic T cell-mediated pathophysiology and may be more amenable to cancer treatment and T-cell suppression with chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and cyclophosphamide.1,6,8

In summary, subacute onset of eye movement abnormalities and postural instability should prompt consideration of brainstem encephalitis, particularly when accompanied by one or more of dysarthria, dysphagia, sleep disorders, trismus, and laryngospasm. Neural antibody testing profiles can assist in autoimmune neurologic and cancer diagnosis.

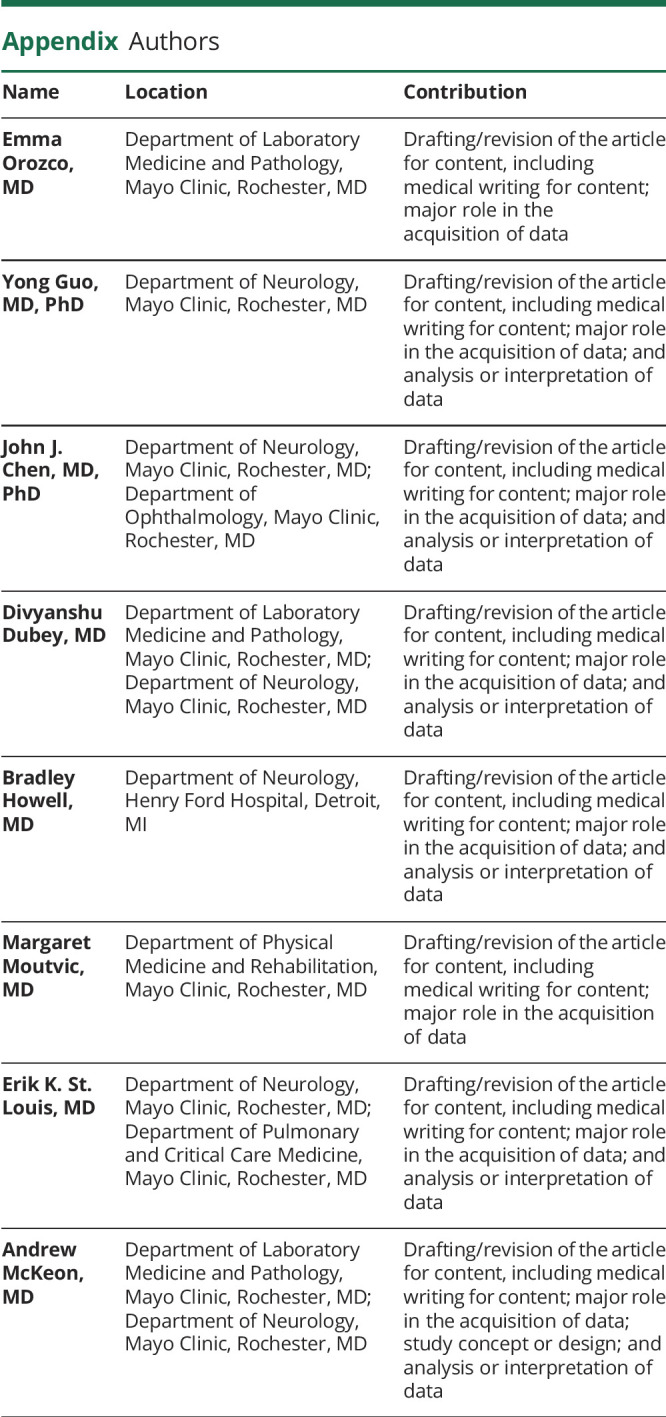

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This study was funded by NIH grants NS126227 and NS120901.

Disclosure

D. Dubey and A. McKeon have a patent pending for KLCHL-11-IgG. The other authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Honorat JA, McKeon A. Autoimmune movement disorders: a clinical and laboratory approach. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(1):4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazis PW, Masdeu J, Biller J. Ocular motor system. In: Brazis PW, Masdeu J, Biller J, editors. Localization in Clinical Neurology, 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001:242-243. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sotoudeh H, Razaei A, Saadatpour Z, et al. Brainstem encephalitis. The role of imaging in diagnosis. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50(6):946-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobin WO, Guo Y, Krecke KN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). Brain. 2017;140(9):2415-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saadeh RS, Bryant SC, McKeon A, et al. CSF kappa free light chains: cutoff validation for diagnosing multiple sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(4):738-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittock SJ, Parisi JE, McKeon A, et al. Paraneoplastic jaw dystonia and laryngospasm with antineuronal nuclear autoantibody type 2 (anti-Ri). Arch Neurol. 2010;67(9):1109-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honorat JA, Komorowski L, Josephs KA, et al. IgLON5 antibody: neurological accompaniments and outcomes in 20 patients. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(5):e385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey D, Wilson MR, Clarkson B, et al. Expanded clinical phenotype, oncological associations, and immunopathologic insights of paraneoplastic kelch-like protein-11 encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(11):1420-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvajal-Gonzalez A, Leite MI, Waters P, et al. Glycine receptor antibodies in PERM and related syndromes: characteristics, clinical features and outcomes. Brain. 2014;137(pt 8):2178-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabater L, Gaig C, Gelpi E, et al. A novel non-rapid-eye movement and rapid-eye-movement parasomnia with sleep breathing disorder associated with antibodies to IgLON5: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and post-mortem study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):575-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams C, McKeon A, Silber MH, Kumar R. Narcolepsy, REM sleep behavior disorder, and supranuclear gaze palsy associated with Ma1 and Ma2 antibodies and tonsillar carcinoma. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(4):521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boronat A, Gelfand JM, Gresa-Arribas N, et al. Encephalitis and antibodies to dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein-6, a subunit of Kv4.2 potassium channels. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(1):120-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pittock SJ, Yoshikawa H, Ahlskog JE, et al. Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoimmunity with brainstem, extrapyramidal, and spinal cord dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1207-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balzer BL, Ulbright TM. Spontaneous regression of testicular germ cell tumors: an analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(7):858-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piepgras J, Holtje M, Michel K, et al. Anti-DPPX encephalitis: pathogenic effects of antibodies on gut and brain neurons. Neurology. 2015;85(10):890-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Jerk see-saw nystagmus, observed when the patient was in ICU early on in his illness. Cyclically, and with a jerky appearance, 1 eye rises and intorts, as the other falls and extorts, followed by reversal of the same movements.Download Supplementary Video 1 (4.4MB, mov) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200950_Video_1

Three sequential video segments demonstrating bursts of opsoclonus, dysarthria, and jaw-closing dystonia and trismus.Download Supplementary Video 2 (7.8MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200950_Video_2