Abstract

Objective:

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, a type of immune effector therapy for cancer, has demonstrated encouraging results in clinical trials for the treatment of patients with refractory hematological malignancies. Nevertheless, there are toxicities specific to these treatments that, if not recognized and treated appropriately, can lead to multi-organ failure and death. This article is a comprehensive review of the available literature and provides, from a critical care perspective, recommendations by experienced intensivists in the care of critically ill adult CAR-T cell patients.

Data Sources:

Pubmed and Medline search of articles published from 2006 to date.

Study selection:

Clinical studies, reviews or guidelines were selected and reviewed by the authors.

Data extraction:

N/A.

Data synthesis:

N/A.

Conclusions:

Until modifications in CAR-T cell therapy decrease their toxicities, the intensivist will play a leading role in the management of critically ill CAR-T cell patients. As this novel immunotherapeutic approach becomes widely available, all critical care clinicians need to be familiar with the recognition and management of complications associated with this treatment.

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cell therapy, cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, cerebral edema, seizures, status epilepticus, intensive care unit

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, a type of Immune effector cell therapy, has demonstrated promising results in clinical trials of select hematological malignancies1–4. In refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia(ALL) and large B-cell lymphomas(LBCL), complete remission rates as high as 50–90% are reported4–8. As a consequence of these impressive responses, the number of CAR-T clinical trials has increased dramatically in the past 5 years and was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration(FDA) for the treatment of pediatric ALL and adult LBCL9–12.

CAR-T cells are autologous or allogeneic T-cells modified to express a single chain antibody that recognizes a specific tumor antigen9,10. Once the cells are ready, the patient receives fludarabine and/or cyclophosphamide, followed by CAR-T infusion. The most investigated cells are CD19-CARs, which recognize the CD19 antigen expressed in B-cell related hematological malignancies. New cell constructs and protocols are being created to target different malignancies, as well as to reduce treatment related toxicities10.

Although the results of clinical trials have been promising, CAR-T cell therapies have specific toxicities that if not recognized and treated, can lead to multi-organ failure and death. Understanding the spectrum and presentation of these toxicities can help clinicians recognize them and initiate timely and appropriate treatment. The purpose of this review article is to highlight, from a critical care perspective, the two most common toxicities associated with CAR-T cell therapy: cytokine release syndrome(CRS) and neurotoxicity. This review is based on a systematic search of currently available literature, and reflects the expert opinion of members of the Oncological Critical Care Research Network with extensive experience in the care of critically ill adult CAR-T cell patients. As CAR-T cell treatment becomes widely available, it will be of utmost importance for all intensivists, to be familiar with the recognition and management of complications associated to this treatment.

Clinical Presentation

Cytokine Release Syndrome

The prevalence of CRS varies depending on the malignancy and CAR T cell construct. Recent data suggest that CRS occurs in 60–93% of patients, with 13–14% exhibiting ≥Grade34,6–8. CRS occurs when antigen recognition by CAR-T cells leads to activation, proliferation, and cytokine release that further activates T-cells, B-cells, natural-killers and macrophages13. This exaggerated inflammatory response can be severe and cause multiple organ failure. Patients with CRS have elevated plasma levels of C-reactive protein(CRP), ferritin, interferon-gamma(IFN-γ), interleukin(IL)-6, IL-10, IL-2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha(TNF-α)3,13–16. Higher CRP and pro-inflammatory cytokines correlate with increased severity of CRS15,17,18. Among patients post-CD19 CAR treatment, elevated IFN-γ and TNF-α levels were associated with higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment(SOFA) scores3. IFN-γ, monocyte chemotactic protein-1(MCP-1) and soluble glycoprotein 130(sgp130), a mediator for IL-6 signaling, may predict severity of CRS prior to symptom onset6,15. CRP has been recommended as a marker for CRS diagnosis since it is widely available16,19. However, elevation of CRP levels is non-specific and its predictive value prior to symptom onset remains unclear.

CRS symptoms usually appear within 5–7 days of CAR-T cell infusion and as late as 10–14 days depending upon the CAR-T construct6–8. The most common symptoms are tachycardia, fever, hypotension and hypoxemia4,16,20. Mild CRS manifests with tachycardia, fever, chills, myalgia and headache3,7,16,21,22. As the syndrome evolves, different organ systems are affected and can progress to multi-organ failure. Cardiovascular toxicity in CRS can present as tachycardia, arrhythmias, heart blocks, or hypertension which devolves to hypotension and vasodilatory and/or cardiogenic shock3,21,23. A cardiomyopathy with decreased ejection fraction can also be present16,21,23. Pulmonary capillary leak syndrome and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema can lead to respiratory insufficiency and progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome(ARDS)8,16,21. Acute kidney injury, hepatic failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy(DIC) may also occur6,8,22. Skin lesions, while rare, can be found8. Table. 1 summarizes the presentation and grading of CRS.

Table 1.

Cytokine Release Syndrome Grading and Treatment.*

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fever, malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia | Fever, malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia | Fever, malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia | Fever, malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia |

| Respiratory | Hypoxemia requiring <40% FiO2 to maintain O2 saturation >92% | Hypoxemia requiring >40% FiO2 (high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive ventilation) to maintain O2 saturation >92% | Hypoxemia requiring mechanical ventilation | |

| Cardiac | Tachycardia | • Stable dysrhythmias • Hypotension/shock: responsive to fluid resuscitation or requiring low dose vasopressors for <24 hours • Cardiomyopathy: EF>40% or 10% drop in EF from baseline |

• Unstable dysrhythmias • Shock: requiring high dose vasopressors or multiple vasopressors, low dose vasopressors for >24 hours or showing signs of hypoperfusion independent of dose. • Cardiomyopathy: EF20–39% or >10% drop in EF from baseline |

• Life threatening dysrhythmias • Shock: refractory requiring multiple vasopressors • Cardiomyopathy: EF<20% |

| Gastrointestinal ° | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Hepatic | AST/ALT<3normal limits (nl), T Bili <1.5 normal limits (nl) | AST/ALT 3–5 nl, T Bili 1.5–3 nl | AST/ALT 5–20 nl, T Bili 3–10 nl | AST/ALT >20 nl, T Bili >10 nl |

| Renal | Creatinine <2 x baseline with normal urine output |

Creatinine 2–3 x baseline with normal urine output | Creatinine >3 x baseline with oliguria | Anuria and indications for dialysis |

| Hematologic | Coagulopathy without bleeding | Coagulopathy with bleeding | Coagulopathy with life-threatening bleeding | |

| Electrolytes | Low PO4, Mg, Na, K | Low PO4, Mg, Na, K | Low PO4, Mg, Na, K | Low PO4, Mg, Na, K |

| Treatment | Monitoring and supportive care ** | Tocilizumab or consider Siltuximab Ɨ |

Tocilizumab or Siltuximab if not dosed yet.

Corticosteroids: dexamethasone10 mg IV q 6hr or equivalent dosing # |

Tocilizumab or Siltuximab if not dosed yet.

Corticosteroids equivalent to pulse dosing (Methylprednisolone1 gm/day) # |

Based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) guidelines and experience at our institutions.

Severity as per CTCAE grading

Tocilizumab dose is 8 mg/kg dosed every 6 hours until symptoms resolve, maximum of 3 doses. If no response after 2–3 doses, consider refractory to tocilizumab. Siltuximab dose is 11mg/kg, single dose.

Supportive care: Treatment with anti-pyretic, hydration, microbiologic cultures and imaging to rule out infectious cause of fevers, empiric antibiotics, monitor for any arrhythmias, replacement of electrolytes and continuous monitoring.

Neurotoxicity

CAR-T neurotoxicity presents in 40–64% of patients and 28% of these cases can be ≥Grade34,7,24. The presentation is biphasic, with the first phase occurring within 7 days of infusion, and the second 10 days after or once CRS symptoms have resolved. Mild neurotoxicity presents with confusion, lack of attention, “distant” gaze, lip-smacking, tremors, mild aphasia and dysgraphia4,5,24. As the symptoms progress, aphasia becomes global, patients are agitated or obtunded, seizures and motor deficits can develop5,7,24. Patients who develop convulsive and non-convulsive seizures can progress to status epilepticus. Irreversible cerebral edema, while not common, has been described24–26. Neelapu et al. created an evaluation tool specific for CAR-T patients to recognize early signs of neurotoxicity5. Patients can have rapid progression and deterioration despite treatment, therefore close monitoring and early involvement of the critical care team is necessary. The clinical presentation and grading of neurotoxicity are described in Table. 2.

Table 2.

Neurotoxicity Grading and Treatment*.

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorientation° | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Severe |

| Dysgraphia° | Present | Present | limited assessment | limited assessment |

| Aphasia° | Word finding difficulty | Moderate aphasia | Severe global aphasia | Severe global aphasia |

| Dyskinesia | Mild tremor | Intermittent facial twitching, tremors or myoclonus | Continuous facial twitching and myoclonus | Continuous facial twitching and myoclonus requiring airway protection. |

| Attention and consciousness° | Inattentive or mild delirium | Lethargic or moderate delirium | Obtundation/stupor or severe delirium | Coma or severe delirium requiring airway protection. |

| Seizure | _______ | _______ | Partial seizures, non-convulsive or convulsive seizures | Convulsive or non-convulsive status epilepticus. |

| Cerebral Edema | _______ | _______ | Grade 1–2 papilledema and associated headache, nausea and vomiting | Grade 3–5 cerebral edema, or clinical signs of herniation such as Cushing’s triad, posturing, cranial nerve VI palsy and diabetes insipidus. |

| Motor strength | 5/5 | 5/5 | 3–4/5 | 0–2/5 |

| Supportive care | • Imaging (CT or MRI brain) and EEG • Frequent neurologic exam • Consider seizure prophylaxis • Consider and treat other causes of encephalopathy as needed • Lumbar puncture if no contraindication |

• Imaging (CT brain or MRI) and EEG • Frequent neurologic exam • Consider seizure prophylaxis • Consider and treat other causes of encephalopathy as needed • Lumbar puncture if no contraindication |

• Imaging (CT or MRI brain) and EEG • Frequent neurologic exam • Treatment of seizures including benzodiazepines, levetiracetam or other anti-epileptic drugs • Consider and treat other causes of encephalopathy as needed • Lumbar puncture if no contraindication |

• Imaging (CT or MRI brain) and continuous EEG • Frequent neurologic exam • Management of status epilepticus as per institutional guidelines • Consider and treat other causes of encephalopathy as needed |

| Treatment | • Supportive care and close monitoring for progression • Consider Tocilizumab if associated to CRS symptoms |

• Supportive care and close monitoring for progression • Consider Tocilizumab if associated to CRS symptoms |

• Corticosteroids: Dexamethasone 10 mg IV q 6hr or equivalent to methylprednisolone** • Consider Tocilizumab if associated to CRS symptoms |

• Corticosteroids: Methylprednisolone IV 1gm/day** • Consider Tocilizumab if associated to CRS symptoms |

Based on Common Terminology criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) guidelines and experience at our institutions.

Consider diagnostic tools to grade severity such as those recommended by Neelapu et. al5

There is no consensus on the underlying pathophysiology that causes this neurotoxicity. Data suggest symptoms result from cytokine mediated central nervous system(CNS) injury as elevated IL-6, IFN-γ and TNF-α levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid(CSF) are associated to worse symptoms21,24,27,28. Another hypothesis is trafficking of CARs into the brain due to increased blood brain barrier permeability; CARs have been found in the CSF of patients with neurotoxicity, and data suggest an association between CAR expansion and neurotoxicity4,7,18,19,24,27.

Differential Diagnoses

Given the broad range of conditions that can present in a similar fashion to CRS and neurotoxicity in this population, the intensivist must concurrently treat and rule out alternative diagnoses common in the oncological patient. Given that sepsis is a common cause of shock and respiratory failure in this population, it is prudent that the intensivist treat as such until an infectious etiology is ruled out. Table. 3 summarizes the differential diagnoses to be considered29–33. However, it is important not to delay treatment of CRS and neurotoxicity when considering and treating other potential diagnoses.

Table 3.

Differential Diagnoses of CAR-T Related Toxicities.

| Clinical Presentation | Diagnoses | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure29,30,31 | • Pneumonia • Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage • Cardiogenic pulmonary edema • “On-target, off-tumor” toxicity |

• Empiric antimicrobial treatment and supportive care. • “On-target, off-tumor” has been described in CARs. Normal tissues express the tumor antigen that CARs are designed to recognize, causing direct tissue injury. Reports include gastrointestinal tract, liver, lung and cardiac toxicity.44 |

| Shock29,32 | • Neutropenic sepsis and septic shock • Cardiogenic shock (acute coronary syndrome, cardiac tamponade, “on-target, off-tumor”) • Hemorrhagic shock |

• Empiric antibiotic treatment and supportive care of the neutropenic septic patient is recommended • Evaluate cardiac function and for signs of overt bleeding |

| Encephalopathy32 | • Intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic stroke • Medication induced (eg: opiates,antibiotics, anxiolytics, anti-psychotics) • Septic encephalopathy • Multi-organ failure • Meningitis |

• Neurotoxicity associated with CAR has specific symptoms such as dysgraphia, inattentiveness, aphasia and lip smacking. Therefore neurological assessment should always include these specific signs for CAR-T toxicity |

| Liver failure5 | • Medication induced • Hypoperfusion • Infectious hepatitis • Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis • “On-target off tumor” toxicity • Portal vein thrombosis or veno-occlusive disease |

• Diagnosis of HLH should require referral or consultation with a specialist as diagnosis can be challenging and the experience in this patient population is limited. |

| Acute renal failure32,33 | • Medication induced • Tumor Lysis syndrome • Obstructive uropathy |

• Monitoring and management of tumor lysis syndrome should not differ from any other oncological patient |

Both neurotoxicity and CRS have a broad clinical presentation and defining specific criterion to diagnose them can be challenging. In the future, a combination of clinical presentation and serum cytokine levels will play a role in diagnosis and prevention. Recent data suggest fever≥38.9°C and elevated serum MCP-1 are highly sensitive and specific for predicting CRS≥46. Similarly, fever≥38.9C, elevated serum IL-6 and MCP-1 are highly sensitive and specific in predicting Grade≥4 neurotoxicity24. Further studies are required to assess the applicability of this criteria prospectively, in different malignancies and CAR-T cell products. At our institutions, we collect daily serum cytokines from these patients; however the costs and slow turnaround of these results have been a constraining factor in their day-to-day applicability.

Treatment of Critically Ill Adult CAR-T Cell Patients

Early involvement of the intensivist in the care of CAR-T patients is of extreme importance as deterioration of these patients is rapid and severe. Rapid Response or Critical Care outreach teams can be useful to assist with monitoring, stabilization and rapid ICU admission. While the care of these patients is multidisciplinary, close attention and support of hemodynamic, respiratory, and multi-organ failure, is steered by the intensivist. Risk factors for early decompensation or severity of toxicity should be discussed between the oncologist and intensivist to assist triage and management(Table. 4).

Table 4.

Risk factors for severity of Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurotoxicity.

| Risk Factor | Comments |

|---|---|

| Tumor Burden | Higher activation and proliferation of CAR-T cells is observed with high tumor burden leading to an exaggerated inflammatory response and higher toxicity4,5,9,13,16. |

| Cell dosing | A higher dose of cells can lead to increased cytokine release, and therefore greater toxicities once these cells are activated18,24. |

| Comorbidities | Higher number of comorbidities has been associated with increased risk and severity of CRS17. |

| Age | Although there are no definitive studies, older patients may have a lower tolerance to CRS and neurotoxicity4,17. |

| Chemotherapy regimen | The chemotherapy regimen prior to cell infusion is important to ensure replication and survival of CAR T cells. A regimen that leads to severe immunosuppression and therefore an exaggerated proliferation of CAR T cells can result in increased toxicity 9,18,24,. |

| Timing of onset of symptoms | Early onset of symptoms is associated with worse toxicity and should lead to more aggressive monitoring and treatment5,24. |

| Cell product | Variabilities of the cell construct between protocols can potentially have an effect on cell proliferation and activity. Some factors include the costimulatory domain used, vector utilized, time in culture and type of culture9. |

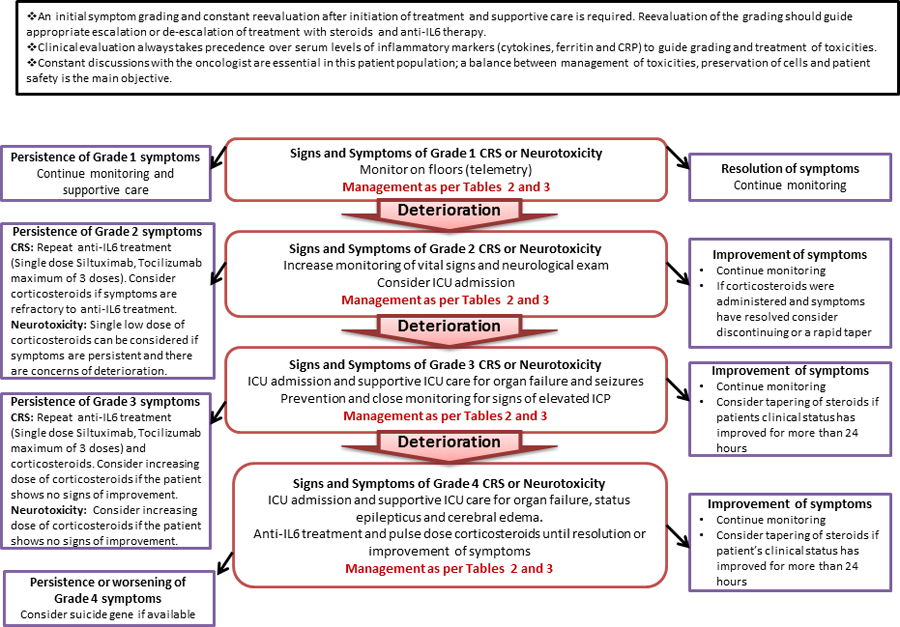

The two mainstays of treatment of CAR-T patients are: 1)anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibodies; 2)corticosteroids. Without initiation of these therapies, supportive ICU care will be insufficient. Tables 1 and 2 describe the indications and dosage of these treatments according to the grade of CRS and neurotoxicity based on published literature and experience at our institutions4,5,16,22. A challenge in managing critically ill CAR-T patients originates from lack of data coming from randomized studies determining the choice, dose, length of corticosteroids, and the role of multiple doses of tocilizumab in severe toxicities. The approach at our institutions includes a careful and close evaluation of the patient’s clinical response to treatment to guide further interventions. Our algorithm(Figure. 1), which is based on our experience and available literature, is a guide for the assessment, monitoring, triaging and treatment of patients with CAR-T cell related toxicities.

Figure 1.

Assessment, Monitoring and Management of CRS and Neurotoxicity

Tocilizumab:

Tocilizumab binds to soluble and membrane bound IL-6 receptors, resolving mild CRS symptoms without affecting the replication of CARs22. Tocilizumab should be used in patients with grade ≥2CRS4,5,16. In patients with neurotoxicity alone, its effectiveness is questionable and we do not recommend its use on neurotoxicity unless it’s associated to CRS16,24. Toxicities include soft tissue infections, abnormal liver function tests and hypercholesterolemia34.

Siltuximab

Siltuximab, another monoclonal antibody, binds to circulating IL-6. While there are no data to support the use of siltuximab in patients with toxicities post-CAR-T cells, we consider its use in patients with refractory CRS. The rationale for siltuximab is based on the following observations:1)patients can be refractory to tocilizumab after multiple doses, suggesting that despite blockade of IL-6 receptors there is a persistent inflammatory response; 2)data suggest that after administration of tocilizumab, IL-6 levels in serum can either increase or stay the same35,36. Although we feel there is biochemical rationale for siltuximab, data supporting its efficacy are lacking. Toxicities reported with siltuximab include rash, hyperuricemia and increased liver function tests37.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids play a role in the treatment of grade≥3 CRS, grade 2 CRS refractory to anti-IL-6 treatment and neurotoxicity. In addition to blunting the inflammatory cascade, corticosteroids suppress the replication of CAR-T cells13,22. In severe cases(Grade3–4) corticosteroids should be used immediately4–6,16,24. It is important that the initiation, dose and duration of therapy be reevaluated depending on the patients’ response to treatment as there is no standardized protocol for their use. While corticosteroids are reserved for more severe presentations of CRS, we have anecdotally observed that patients with neurotoxicity respond better to corticosteroids, even single doses, than tocilizumab alone. Despite initial concerns of corticosteroids suppressing CAR-T cell replication, short courses do not appear to affect tumor response rates or long term clinical remission5,7,28. Regardless, corticosteroid use should be discussed carefully with the oncologist.

Specific ICU Considerations

Cardiovascular toxicity in CRS

CRS with vasodilatory shock is a common reason for ICU admission of CAR-T patients. While guidelines describe a dose of vasopressor agents to determine grading, clinical judgement plays an important role in treatment decisions in conjunction with vasopressor dosing5,16. Signs of end-organ hypo-perfusion, increasing lactate, poor lactate clearance, or rapid increase in vasopressor requirement, should lead to consideration of early use of corticosteroids. While shock usually responds to tocilizumab and corticosteroids, some patients develop refractory shock38.

Early recognition and adequate management of patients with CRS related cardiomyopathy is important given the high associated mortality rate3,21. Electrocardiographic changes and elevation of cardiac troponins should be monitored as they suggest higher severity of CRS and not necessarily an acute coronary syndrome3,4,21. The most common arrhythmias associated with CRS are sinus tachycardia and atrial fibrillation8,16,21. QTc prolongation and fatal arrhythmias have been described17,18.

Ruling out infectious causes of fever and following guidelines for septic shock is recommended39,40. Diligent physical examination, obtaining blood, sputum and urine cultures, and commencing empiric broad spectrum antibiotics should be initiated in these patients even if CRS is suspected. An immediate echocardiogram to assess ejection fraction and rule out other causes of shock is of extreme importance. Interventions to assess and optimize fluid status and cardiac output should be considered.

Neurotoxicity with seizures and status epilepticus

Non-convulsive seizures are associated with CAR-related neurotoxicity and can progress to non-convulsive status epilepticus(NCSE) in up to 10% of treated patients5. Early recognition and treatment of seizures and NCSE is essential, therefore an EEG should be performed in all patients with signs of neurotoxicity. While preference of antiepileptic drug(AED) varies, it is imperative to have clear institutional guidelines for management of these patients. Due to the high prevalence of seizures, two of our institutions have initiated seizure prophylaxis with levetiracetam in all patients being treated with CAR-T cells. The use of levetiracetam is preferred due to its favorable drug-drug interaction and low toxicity5. In our experience, patients with partial seizures usually respond to benzodiazepines, a second line AED and corticosteroids. A quick steroid taper can be considered if the seizures are easily controlled and mental status improves. However, in patients who develop NCSE or are not improving after an initial trial of corticosteroids, higher doses should be initiated(Table. 2). All patients with seizures post CAR-T treatment should be admitted to the ICU as these patients have the potential to deteriorate rapidly and progress to status epilepticus, and in some rare cases cerebral edema23,25,26. Continuous video EEG is recommended to help in the management of patients with NCSE. Burst suppression with midazolam, propofol or phenobarbital might be necessary and the choice requires consideration of hemodynamics and concomitant organ failure.

Neurotoxicity with cerebral edema

Five cases of cerebral edema were first documented in ALL patients treated with CD19-CARs25. Their presentation was acute, with fulminant cerebral edema within 24 hours which was attributed to the fludarabine used for conditioning13,14. However, two other patients treated without fludarabine and a patient with refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, treated with a different CAR-T construct, also developed cerebral edema24,25. While no other cases are reported since, it is important for the intensivist to consider this fatal complication. The pathophysiology of the cerebral edema is still unclear, but with our current knowledge of toxicities related to CARs, it would be difficult to ignore the possibility of an uncontrolled inflammatory response in the brain and breakdown of the blood brain barrier24.

Monitoring for signs of elevated intracranial pressure should be performed on patients with Grade≥2 encephalopathy. Non-invasive methods such as fundoscopy, transcranial Doppler and ocular ultrasound to measure optic nerve sheath diameter can be considered. If there is evidence of significant neurotoxicity associated with elevated ICP, corticosteroids should be initiated; if the patient does not improve or deteriorates, a pulse dose should be considered(Table. 2)5. The role of brain imaging with CT scan is limited as parenchymal changes were only evident after clinical signs of herniation and brain death presented. However, CT scan is still recommended to rule out other neurological emergencies such as an ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage. Specific flair changes in brain MRI have been observed in neurotoxicity, and these findings may be useful in the future to monitor and guide treatment, however data is still scarce5,24. If patients need to be intubated for airway protection, it is important to avoid induction agents that can cause hypotension or elevated ICP. Other basic considerations include head elevation, aggressive treatment of fevers and seizures, and avoiding aggressive stimulation. Blood pressure management to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure and treatment with hypertonic saline, especially in patients with hyponatremia, should be a priority. Due to the prevalence of coagulopathy and severe thrombocytopenia in these patients, our experience with invasive ICP monitoring is limited. However, if a patient is a candidate for an external ventricular device, it can be considered. Tapping of Ommaya reservoirs could be used for reading of intracranial pressure, however underestimation of ICP can occur due to the technique used for their access.

Additional Toxicities

Respiratory insufficiency due to non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema in these patients is acute, presenting in a majority after fluid resuscitation and progressing rapidly to ARDS and respiratory failure41. We recommend that any patient with rapid progression of FiO2 requirements or pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray, those requiring FiO2>40% (via high flow nasal cannula) or those on bilevel positive airway pressure be admitted to the ICU for careful monitoring. Early antibiotics, intubation, mechanical ventilation, and bronchoalveolar lavage to evaluate for infection or alveolar hemorrhage should be considered. Lung-protective ventilator strategies with low tidal volume ventilation should be used42.

Electrolyte disturbances such as hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia and hypomagnesemia are present in patients post CARs and should be treated aggressively in the setting of neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity3,8,18,23. Renal failure usually occurs in the presence of multi-organ failure and not as a symptom of CRS alone. Diffuse cutaneous manifestations such as macules and papules may occur and are reversed quickly with corticosteroids8. If the presentation is extreme, patients may be managed in line with burn care protocols.

Coagulopathy, independent of liver dysfunction, may be present and has been associated with bleeding, therefore careful monitoring of fibrinogen and coagulation profile should be performed6,43. Recent data suggest that severe neurotoxicity is associated with DIC24.

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), was described in one patient treated with CD19 CARs28. The exaggerated immune response is similar in both CRS and HLH, making an already challenging diagnosis, to be more so in patients who have underlying CRS. HLH, regardless of concomitant CRS, portends a poor prognosis and expert consultation is suggested. HLH in CAR-T patients can be considered in patients with CRS>Grade3 with liver, renal and pulmonary toxicity, ferritin levels>10.000ng/ml and hemophagocytosis on organ biopsy 5.

B-cell aplasia is usually a delayed complication post CAR-T therapy and has been described from 10 weeks to 3 years post-infusion9. This complication can be monitored with immunoglobulin-G levels and managed with monthly immunoglobulin infusions to decrease risk of opportunistic infections.

Future Research

Areas of future research should include: 1)use of serum cytokines and other inflammatory markers as tools to assist with diagnosis, treatment or recognize high risk patients; 2)further understanding of the pathophysiology of neurotoxicity to optimize management of this toxicity and understand how CSF studies and imaging could be used for its identification; 3)use of other strategies to suppress CARs in the setting of severe toxicities such as suicide genes that trigger CAR-T cell apoptosis and resolve the immune mediated toxicity9,15,41,44,45. This important safety switch is in the early stages of clinical trials and their efficacy is still being investigated41,45.

Conclusions

CAR-T cell therapy is a promising treatment for an increasing number of refractory malignancies1–4,7,8,14,19,43. However, the morbidity associated with this novel therapy is significant, with many patients requiring ICU admission. Early recognition, grading and treatment is the cornerstone of management of CRS and neurotoxicity. Until modifications in CAR-T cell therapy can decrease these toxicities, the intensivist will play a leading role in the management and support of CAR-T cell patients. As with many of the oncological patients, frequent communication between the ICU team, oncologists and other consultants is essential to providing high quality care to this complex population. All institutions participating in CAR-T cell therapy should be familiar with their complications, have protocols in place and a streamlined process of ICU admission for patients who are deteriorating. Our practice recommendations should serve as a tool for all clinicians caring for a critically ill adult CAR-T patient.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no financial conflict of interest.

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Gutierrez, McEvoy, Mead, Stephens, and Pastores disclosed off-label product use of siltuximab for use in cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity related to chimeric antigen receptor T cells. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood 2011;118(18):4817–4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2011;365(8):725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 2012;119(12):2709–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JH, Riviere I, Gonen M, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of CD19 CAR Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378(5):449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay KA, Hanafi LA, Li D, et al. Kinetics and Biomarkers of Severe Cytokine Release Syndrome after CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor-modified T Cell Therapy. Blood 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377(26):2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2017;377(26):2545–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrigan-Curay J, Kiem HP, Baltimore D, et al. T-cell immunotherapy: looking forward. Mol Ther 2014;22(9):1564–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson HJ, Rafiq S, Brentjens RJ. Driving CAR T-cells forward. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13(6):370–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lulla P, Ramos CA. Expanding Accessibility to CD19-CAR T Cells: Commercializing a “Boutique” Therapy. Mol Ther 2017;25(1):8–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maus MV, Nikiforow S. The Why, what, and How of the New FACT standards for immune effector cells. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu XJ, Tang YM. Cytokine release syndrome in cancer immunotherapy with chimeric antigen receptor engineered T cells. Cancer Lett 2014;343(2):172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2013;5(177):177ra138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teachey DT, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, et al. Identification of Predictive Biomarkers for Cytokine Release Syndrome after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016;6(6):664–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 2014;124(2):188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(6):540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015;385(9967):517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19–28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(224):224ra225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. A Phase 2 Multicenter Trial of KTE-C19 (anti-CD19 CAR T Cells) in Patients With Chemorefractory Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma (PMBCL) and Transformed Follicular Lymphoma (TFL): Interim Results From ZUMA-1. Blood 2016;128(22). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 2016;127(26):3321–3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maude SL, Barrett D, Teachey DT, Grupp SA. Managing cytokine release syndrome associated with novel T cell-engaging therapies. Cancer J 2014;20(2):119–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA-1: A Multicenter Study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T Cell Therapy in Refractory Aggressive Lymphoma. Mol Ther 2017;25(1):285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gust J, Hay KA, Hanafi LA, et al. Endothelial Activation and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Neurotoxicity after Adoptive Immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T Cells. Cancer Discov 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbasi J Amid FDA Approval Filings, Another CAR-T Therapy Patient Death. JAMA 2017;317(22):2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkes N Trial of novel leukaemia drug is stopped for second time after two more deaths. BMJ 2016;355:i6376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y, Sun J, Wu Z, et al. Predominant cerebral cytokine release syndrome in CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2016;9(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Kte-C19 (anti-CD19 CAR T Cells) Induces Complete Remissions in Patients with Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): Results from the Pivotal Phase 2 Zuma-1. Blood 2016;128(22):LBA-6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thirumala R, Ramaswamy M, Chawla S. Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Complications in Critically Ill Patients with Cancer. In: Critical Care Clinics. Intensive Care of the Cancer Patient Vol 26.2010:59–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares M, Depuydt PO, Salluh JIF. Mechanical ventilation in Cancer Patients: Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. In: Critical Care Clinics. Intensive Care of the Cancer Patient Vol 26.2010:41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pastores SM, Voigt LP. Acute Respiratory Failure in the Patient with Cancer: Diagnostic and Management Strategies. In: Critical Care Clinics. Intensive Care of the Cancer Patient Vol 26.2010:21–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutierrez C, Pastores SM. Oncologic Emergencies. In: Hall BJSG, ed. Hall, Schmidt and Wood’s Principles of Critical Care 4th ed. Burlington, NC: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015:872–880. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benoit DD, Hoste EA. Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients with Cancer. In: Critical Care Clinics. Intensive Care of the Cancer Patient Vol 26.2010:151–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones G, Ding C. Tocilizumab: a review of its safety and efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2010;3:81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen F, Teachey DT, Pequignot E, et al. Measuring IL-6 and sIL-6R in serum from patients treated with tocilizumab and/or siltuximab following CAR T cell therapy. J Immunol Methods 2016;434:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, Nakahara H, Takagi N, Kakehi T. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood 2008;112(10):3959–3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurzrock R, Voorhees PM, Casper C, et al. A phase I, open-label study of siltuximab, an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody, in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or Castleman disease. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(13):3659–3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neelapu SS. An interim analysis of the ZUMA-1 study of KTE-C19 in refractory, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2017;15(2):117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(4):e56–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43(3):304–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris J FDA Puts Clinical Holds on “Off-the-shelf” CAR-T trials http://www.onclive.com/web-exclusives/fda-puts-clinical-holds-on-offtheshelf-cart-trials. 2017.

- 42.Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195(9):1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371(16):1507–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonifant CL, Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ, Curran KJ. Toxicity and management in CAR T-cell therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2016;3:16011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu E, Tong Y, Dotti G, et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]