Abstract

Olea europaea L. Cv. Arbequina (OEA) (Oleaceae) is an olive variety species that has received little attention. Besides our previous work for the chemical profiling of OEA leaves using LC–HRESIMS, an additional 23 compounds are identified. An excision wound model is used to measure wound healing action. Wounds are provided with OEA (2% w/v) or MEBO® cream (marketed treatment). The wound closure rate related to vehicle-treated wounds is significantly increased by OEA. Comparing to vehicle wound tissues, significant levels of TGF-β in OEA and MEBO® (p < 0.05) are displayed by gene expression patterns, with the most significant levels in OEA-treated wounds. Proinflammatory TNF-α and IL-1β levels are substantially reduced in OEA-treated wounds. The capability of several lignan-related compounds to interact with MMP-1 is revealed by extensive in silico investigation of the major OEA compounds (i.e., inverse docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and ΔG calculation), and their role in the wound-healing process is also characterized. The potential of OEA as a potent MMP-1 inhibitor is shown in subsequent in vitro testing (IC50 = 88.0 ± 0.1 nM). In conclusion, OEA is introduced as an interesting therapeutic candidate that can effectively manage wound healing because of its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Olea, olive, LC–HRESIMS, wound, TNF-α, TGF-β, MMP-1, virtual docking

1. Introduction

Worldwide, wounds pose serious health risks, placing significant financial, commercial, and communal stress on healthcare organizations, caregivers, patients, and families [1,2]. Wounds are reported as natural, thermal, chemical traumas, or abuses that destroy skin integrity [3]. A complex interaction of various cell types is an essential response to tissue damage. The initial constriction of blood vessels and aggregation of platelet are meant to break off bleeding. An inflow of inflammatory cells, beginning with neutrophils, follows, which discharges several mediators, including cytokines, to develop angiogenesis, thrombosis, and re-epithelialization. Additionally, the fibroblasts deposit extracellular factors and act as scaffolds [4]. The inflammatory stage is marked by hemostasis, chemotaxis, as well as enhanced vascular permeation, which diminishes further destruction, excludes cellular debris, heals the wound, and encourages cellular migration. The inflammatory stage usually lasts several days [5]. Granulation tissue development, re-epithelialization, and neovascularization define the proliferative phase. This period might persist for several weeks. As the wound grows, it gains maximal strength throughout the maturation and remodeling period [6]. One of the key objectives of the wound healing process is the regeneration of new connective tissue [7]. These restoration events occur by accumulating several collagen-dependent and noncollagenous-dependent molecules to supplement the healing process of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is significant for providing the cellular microenvironment necessary for morphogenesis and growth.

Proteinases known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) contribute to ECM breakdown [7,8,9]. MMP activities are perfectly adjusted by controlling homeostatic environments at different stages including transcriptional level, precursor zymogen induction, ECM interplay, and suppression by internal inhibitors [9,10,11]. Disorders such as arthritis, tumor, atherosclerosis, nephritis, fibrosis, aneurysms, and tissue lesions can take place owing to a loss of regulatory activity [12]. Several studies have reported that MMPs are over-expressed in wounds (e.g., MMP-1–3) [13]. Consequently, inhibition of the catalytic activity of these hydrolytic enzymes was associated with a better and faster wound-healing process (i.e., better collagen maturation and crosslinking) [14].

The benefit of medicinal plants in curing wounds at different stages is widespread in almost all conventional medical systems worldwide. Significant potential for enhancing and improving the quality of wound healing has been shown in several herbal-based remedies [15,16], based on Curcuma longa (L.) [17], Centella asiatica [18], Sphagneticola trilobata [19], Aloe barbadensis [20], Azadirachta indica [21], and Chamomilla recutita [22]. The use of Theacea plant bioactive components for wound healing is patented [23]. Additionally, another reported patented is new herbal components for treating wounds, which consisted of Curcuma longa, Hamil tonia suaveolens, Glycyrrhiza glabara, Tipha angustifolia, Azadirachta indica, and Sesamum indicum (Til) oil [24]. Moreover, herbal-based pharmaceutical remedies are used, such as moist exposed burn ointment (MEBO®), which is composed of several amino acids and other plant-based constituents [25].

Since antiquity, OEA has been grown primarily for oil production in Mediterranean lands. Recently, the positive effects of biophenols (e.g., verbascoside, oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and luteolin-7-O-β-glucopyranoside) isolated from olive for human benefits (e.g., antihypertensive [26], cholesterol-lowering [27], cardioprotective [28], anti-inflammatory, and as co-adjuvant for obesity [29]) have been carefully established [30].

Olea europaea L. Cv. Arbequina, a cultivar of olives, is an olive variety species that has received little attention. Arbequina has lately become one of the world’s most important olive cultivars, owing partly to extensive cultivation and “super-high-density” plantations [31]. Arbequina trees can fit a variety of climatic and soil conditions. Nonetheless, it flourishes in long, hot, and dry summers and grows best in alkaline soils. Nonetheless, it is frost-resistant and pest-resistant [32]. Almost 78 percent of olive oil is grown on Arbequina rootstock [33]. As a result, Arbequina olives have one of the highest oil contents and are largely utilized in the production of olive oil [34]. Publicly, Olea europaea oil and polyphenol contents are fully documented to reduce oxidative stress, stimulate wound healing, and minimize inflammation [35,36,37,38,39,40]. However, the oil and polyphenol contents are generally affected by climatic conditions during ripening and the degree of maturation, especially the Arbequina types [41,42].

In an attempt to compare the cultivar olive with the wild types in the content and activities concerning this field, our previous work estimated the potential of OEA leaves (cultivated in Egypt) as an internal wound healer against gastric ulcers in a rat model compared to wild O. europaea [43]. The results showed that the crude extract of the OEA cultivar was richer with polyphenolic content using LC–HRESIMS. The ulcer index of the rat model was significantly decreased, and the mucosa from the lesions was protected [43].

To complement the previous work, we targeted the wound healing ability of OEA as an external wound healer by applying an excisional wound model. We focused on essential wound healing targets, encompassing transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) as well as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Illustrating the mode of action of OEA using several in vitro and in silico assays. Additionally, we assessed the possible inhibitory effect of OEA on one of the key players in wound healing (i.e., MMP-1), as proposed by the in silico investigation. Figure 1 depicts the framework of the present investigation.

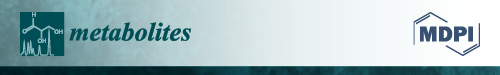

Figure 1.

The general summary of the present research is as follows: Olea europaea leaves were extracted, chemical profiling was carried out, and finally the leaves were assessed for their potential wound healing activity by evaluating their antioxidant activity and ability to inhibit MMP1, upregulate TGF-β relative gene expression, and downregulate the relative gene expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-β1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

In April 2020, OEA leaves were harvested from Basita Farms in Aljouf, Saudi Arabia. Dr. Hamdan Ogreef (Camel and Range Research Center in Sakaka, Saudi, Arabia) graciously identified it. A voucher specimen (2020-BuPD 75) was kept at Beni-Suef University’s Pharmacognosy Department; Faculty-of-Pharmacy.

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

All reagents and compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated (Germany, Biosystems SA Costa Brava 30, Barcelona, Spain).

2.3. Plant Material Extraction

Two kilograms of OEA leaves were collected, meticulously cleaned, and air-dried for 10 days in the shade. The leaves were ground with an OC-60B/60B herb grinding mill (60–120 mesh, Henan, China—Mainland). The powdered leaves were soaked in a huge, closed glass jar for intensive extraction with 70% EtOH (15 L X3) and concentrated under reduced pressure at 45 °C. Following these steps, 80 grams of dried residue was obtained. It was saved at 4 °C for further phytochemical and biological screenings [44,45].

2.4. Metabolomic Analysis

According to our previously reported protocol [44], LC-HRMS-assisted metabolomic analysis of OEA was carried out. The detailed method is described in the supplementary file.

2.5. In Vivo Wound Healing Activity

2.5.1. Animal Treatment

Eighteen wholesome adult male New Zealand Dutch breed albino rabbits participated in this investigation (2.1–2.7 kg). Polypropylene cages were used for animal housing. The normal pellet feed and unlimited water were freely available during the experiment. The seven days leading up to the experiment were spent acclimating the animals to the lab environment. Animals were introduced to a home with adequate ventilation under conditions of 25 ± 2 °C and relative moisture of 44–55% with 12 h cycles of dark/light.

2.5.2. Samples Preparation for the Bioassay

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of OEA extract in healing wounds, excisional wound models were applied [42]. The extract was made for the wound models by dissolving OEA dry extract in carboxymethylcellulose (2 g of dried extract in 100 mL of 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose) and kept at 4 °C in the dark. Each test extract was applied topically to the wound site as soon as it was prepared [43].

2.5.3. Model for Circular Excision Wounds

Excisional wounds were induced in rabbits [46,47]. In summary, 0.01 mL Ketalar® (Ketalar, Sankyo Lifetech Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to anesthetize the animals. The back hairs of the rabbits were carefully shaved. The circular incision of each animal was made with a 6-mm biopsy punch by only excising the skin on the dorsal interscapular area. A sterile cotton swab soaked in 0.9% saline was used to clean the wounds. The induced wounds were left undressed throughout the whole duration of the study.

18 rabbits were divided to 3 groups. Each group comprised 6 rabbits. Group 1 (control rabbit): ulcers treated with vehicle only twice daily; Group 2: ulcers treated topically with OEA 2% w/v extract twice a day for 14 days until the wounds were completely cured; and Group 3: ulcers were topically treated with MEBO® (Julphar Gulf Pharmaceutical Industries, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates) (a comparable market product) twice daily for 14 days until the wounds were mostly cured.

2.5.4. Collection of Tissue Samples

On days seven and fourteen, full-thickness skin biopsies of complete ulcers from each rabbit were taken under anesthesia. Tissue samples were sectioned into three halves. Most of the dissected wound tissue was utilized for gene expression research. For histological investigation, the remainder was kept in formalin [43].

2.5.5. Percentage Wound Closure Rate

A camera (Fuji, S20 Pro, Sendai, Japan) was used to monitor the development of the wound region every three days until it healed fully. Using Image J 1.49 v software from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, the wound area was assessed, and the wound closure rate was reported as a percentage change in the original wound area using the following formula:

n: days numbers.

Additionally, a wound aspect ratio was established to explain observed variations in the shape and angular direction of wound contraction between groups. Using Image J, the length to width ratio was calculated from measurements of the wound’s length (measured from head to tail) and width.

2.5.6. Histological Study

Dorsal skin samples from all wounds were taken and fixed in buffered formalin before being treated with a graded series of alcohol and xylene and subsequently immersed in paraffin blocks. Tissue slices were cut at a thickness of 4 µm and discolored with hematoxylin/eosin dye. The Leica Application Suite (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany, a light microscope) was applied to evaluate and photograph the mounted slides [47].

2.5.7. Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA Extraction

In 0.5 mL TRIzol reagent (RNA Isolation Reagent, Invitrogen—ThermoFisher Products & Kits, Amresco, LLC-Solon, Waltham, MA, USA), 50 mg of dorsal skin tissue was homogenized using an ultrasonic homogenizer (Sonics-Vibracell, Sonics and Materials Inc., Newtown, Fairfield County, CT, USA). According to the guidelines of the producer, total RNA was extracted from dorsal skin tissues, and the concentration of RNA yield and purity were calculated [48].

Real-Time qRT–PCR

cDNA synthesis with a constant RNA concentration across all samples, the RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit was used as directed by the manufacturer (#K1632, Thermo Scientific Fermentas, St. Leon-Ro, Germany). SYBER Green (Thermo Scientific Fermentas St. Leon-Ro, Germany-Maxima SYBER Green qPCR Master Mix (2X)) was employed in real-time PCR using single-stranded cDNAs. A StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to perform qRT–PCR. The set of primers used for real-time PCR is mentioned in Table 1 qRT–PCR was performed using 0.02 g RNA per reaction and 10 Pmol of particular primers for thirty cycles of 95 °C for ten seconds and 60 °C for one minute. After normalization to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a housekeeping gene, gene expression levels were obtained. To assess the relative quantities of RNA, the comparative Ct approach was utilized. Formula 2 (−ΔΔCt) was used to determine the relative expression [12].

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Name of Gene | Accession Number | Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | NC_013670.1 | forward | 5′-AGCTTCTCCAGAGCCACAAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CCTGACTACCCTCACGCACC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | NC_013676.1 | forward | 5′-GTCAAGGCTGAGAACGGGAA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ACAAGAGAGTTGGCTGGGTG-3′ | ||

| TGF-β | NC_013672.1 | forward | 5′-GACTGTGCGTTTTGGGTTCC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CCTGGGCTCCTCCTAGAGTT-3′ | ||

| TNF-α | NC_013680.1 | forward | 5′-GAGAACCCCACG GCTAGATG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTCTCCAACTGGAAGACGCC-3′ | ||

| MMP-1 | forward | 5′-TTTCCCCCTGGCGCCGGCGTT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CTCGTGCGCTGCCACCAGG-3′ |

2.6. Molecular Modeling

2.6.1. Prediction of the Molecular Targets of the Dereplicated Metabolites of OEA

By carrying out docking against all protein structures saved in the PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/) (accessed on 1 March 2022), several suggested targets for the OEA-isolated molecules were putatively determined. In this analysis, small overlapping grids are adaptively built to constrain the searching space on protein surfaces, allowing them to run many accurate dockings runs in a shorter time [49]. The information was compiled as a ranking of binding affinity scores. We utilized a binding affinity score threshold of 7 kcal/mol to recognize the ideal receptors for each OEA-isolated molecule.

2.6.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation and estimate of binding free energy were carried out as previously mentioned using Desmon software [50]. The complete technique is included in the supplemental file.

2.7. In Vitro MMP-1 Activity Assay

OEA was tested for its inhibitory activity against MMP-1. The enzyme inhibition assay was conducted in accordance with the company instructions (Abcam, Waltham, MA USA, Cat. No: ab118973).

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (n = 6). Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons was applied after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Calculations involving statistics were performed using Graph Pad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA, United States). The outcomes were deemed significant when the p value was less than 0.05 [12].

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Dereplication of OEA Leaves Extract

According to our previous study, OEA crude extract dereplicated 18 metabolites using LC–HRESIMS, which identified as 3-hydroxy-12-oleanen-28-oic acid; 2,3-dihydroxy-13(18)-oleanen-28-oic acid; oleuropein; 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethanol; oliverixanthone; cleroindicin F; oleuropein 3″-Me ether; oleoside; 11-octadecen-9-ynoic acid; 3-hydroxy-12-ursen-28-oic acid, 3-ketone; 8-epimer, (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethyl) ester; chebulic acid 4,5-didehydro(E-), tri-Et ester; verbascoside; luteolin; olenoside A; olivine; olivacene; and oleacein [43].

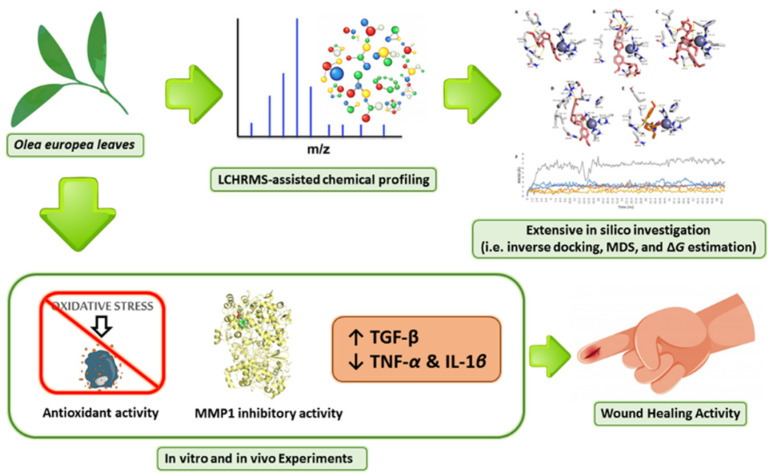

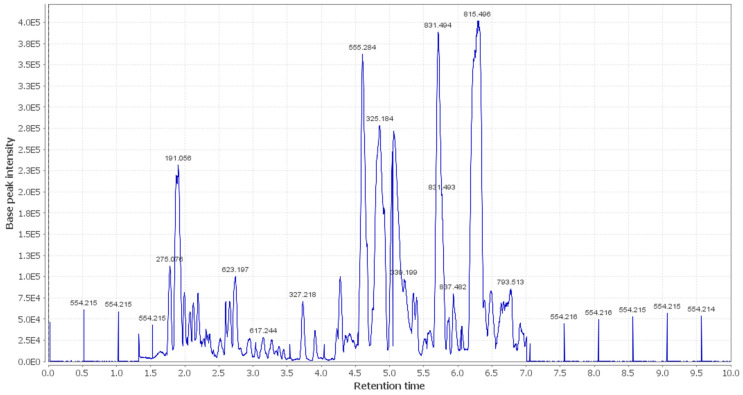

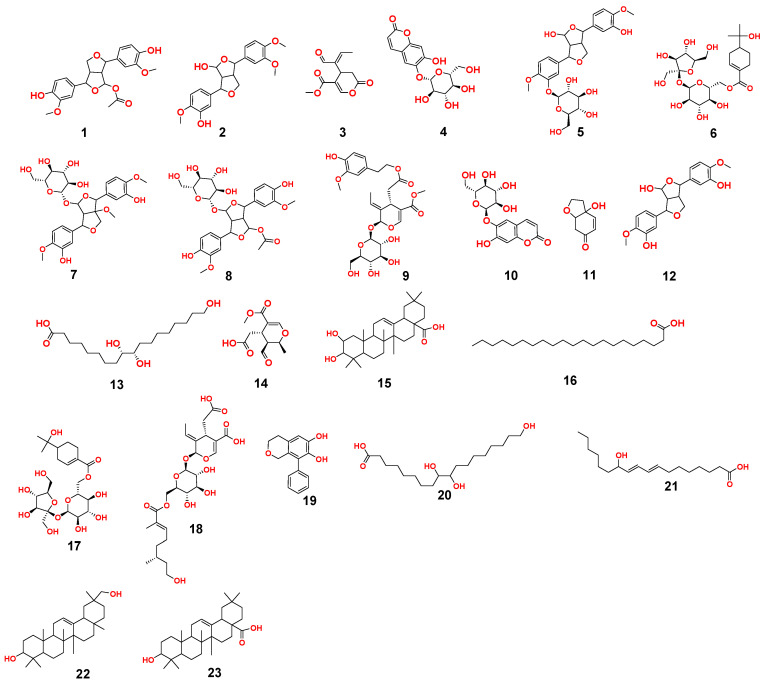

In the present study, additional hits were introduced (Table 2, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). The m/z 375.1444 and 389.1600. Mass ion peaks corresponded to the proposed molecular formulas C20H22O7 and C21H24O7 [M + H]+, which fit tertahydrofurofuran lignan 7,9′:7′,9-diepoxy-8,8′-lignan-3,3′,4,4′,8-pentol;3,3′-di-Me ether 1, 7,9′:7′,9-diepoxy-8,8′-lignan-3,3′,4,4′,8-pentol; 3,3′,4′-tri-Me ether 2, which was formerly extracted from OEA [35,36,37].

Table 2.

Dereplicated metabolites from LC-HRESIMS analysis of OEA leaves crude extract.

| Metabolite No. | Source | MF | RT (min) | m/z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OEA | C20H22O7 | 2.01432 | 375.1444 |

| 2 | OEA | C21H24O7 | 2.01740 | 389.1600 |

| 3 | OEA | C11H12O5 | 2.20205 | 223.06055 |

| 4 | OEA | C15H16O9 | 2.37151 | 341.08660 |

| 5 | OEA | C26H32O12 | 2.40519 | 537.1972 |

| 6 | OEA | C22H36O13 | 2.49208 | 509.22142 |

| 7 | OEA | C27H34O13 | 2.53020 | 567.2078 |

| 8 | OEA | C28H34O13 | 2.75095 | 579.20783 |

| 9 | OEA | C26H34O13 | 3.02300 | 555.2078 |

| 10 | OEA | C22H24O8 | 3.23649 | 417.15389 |

| 11 | OEA | C8H10O3 | 3.78010 | 155.0708 |

| 12 | OEA | C15H16O9 | 3.78010 | 341.0873 |

| 13 | OEA | C18H36O5 | 4.09611 | 331.24803 |

| 14 | OEA | C11H14O6 | 4.18760 | 243.0869 |

| 15 | OEA | C30H48O4 | 5.96396 | 473.36213 |

| 16 | OEA | C21H42O2 | 6.01750 | 327.3263 |

| 17 | OEA | C22H36O13 | 9.11727 | 509.2235 |

| 18 | OEA | C26H38O13 | 10.5214 | 557.2229 |

| 19 | OEA | C15H15O3 | 12.8056 | 243.1013 |

| 20 | OEA | C18H35O5 | 14.6147 | 331.2490 |

| 21 | OEA | C18H32O3 | 21.7898 | 295.2280 |

| 22 | OEA | C30H50O2 | 29.2663 | 443.3880 |

| 23 | OEA | C30H49O3 | 30.5872 | 457.3682 |

Figure 2.

LC-HRESIMS chromatogram of the dereplicated metabolites of OEA (positive mode).

Figure 3.

LC-HRESIMS chromatogram of the dereplicated metabolites of OEA (negative mode).

Figure 4.

Dereplicated metabolites from LC-HRESIMS analysis of OEA (1–23).

The m/z 223.06055 [M − H]+ and 341.08660 [M + H]+ molecular ion mass peaks, respectively, were characterized for the predicted molecular formulas C11H12O5 and C15H16O9, and indicated S-(E)-elenolide 3 and benzopyrene, 6,7-dihydroxy-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one;6-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 4, respectively, which were formerly separated from OEA [35,38,39]. The ion mass peaks 537.1972, 509.22142 m/z, [M + H]+ for C26H32O12, C22H36O13 predicted molecular formulas, indicated the tertahydrofurofuran lignan nucleus of 7,9′:7′,9-diepoxy-8,8′-lignan-3,3′,4,4′,8-pentol, 3,3′-Di-Me ether,4-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 5, which was divided from OEA [39], and 6-O-oleuropeoyl-sucrose 6, which was divided from OEA [51]. Two ion peaks, with m/z 567.2078 and 579.20783 [M + H]+, predicted for molecular formulas C27H34O13 and C28H34O13 were dereplicated as 7,9′:7′,9-diepoxy-8,8′-lignan-3,3′,4,4′,5,8-hexol, 3,3′,5-tri-Me ether,8-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 7, and 3,3′,4,4′,8-pentahydroxy-7,9′:7′,9-diepoxylignan,3,3′-di-Me ether, 8-Ac,4-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 8, respectively, which were separated previously from OEA [37]. The mass ion peak at m/z 541.1921 reflected the predicted molecular formula C25H32O13 and indicated secoiridoid oleuropein 9, which was divided from OEA [52]. Additionally, m/z 417.15389 and 155.0708, corresponding to the suggested formulas C22H24O8, C8H10O3 [M + H]+, which fit tertahydrofurofuran lignan 3,3′,4,4′,8-pentahydroxy-7,9′:7′,9-diepoxylignan; 3,3′-Di-Me ether,8-Ac 10, which was already divided from OEA [35,36,37], and megaritolactones, halleridone 11, which was also isolated from OEA [38,39].

Additionally, the m/z 341.0873, 331.24803, 243.0869, and 473.36213 analogous to the proposed molecular formulas C15H16O9 [M + H]+, C18H36O5 [M − H]+, C11H14O6 [M + H]+, and C30H48O4 [M + H]+ fit benzopyrene, fatty acid, triterpene compounds 6,7-dihydroxy-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one;6-O-β-d-glucopyranoside 12, which was isolated from OEA [35], 9,10,18-trihydroxyoctadecanoic acid 13, elenaic acid 14, which were isolated from OEA [53,54,55,56,57], and 2,3-dihydroxy-13(18)-oleanen-28-oic acid 15, respectively, which were previously isolated from OEA [58]. The m/z 277.2167 suggested the molecular formula C18H30O2 [M-H]+, fit fatty acids 11-octadecen-9-ynoic acid 16, formally isolated from OEA [56,57]. The ion mass peaks at m/z 509.22142, 557.2229 [M − H]+, for C22H36O13, C26H38O13 indicated 6-O-oleuropeoyl-sucrose 17, oleoside; 6′-O-(8-hydroxy-2,6-dimethyl-2E-octenoyl) 18, which was isolated from OEA [51]. Moreover, m/z 243.1013, 331.2490, 295.2280, 443.3880, and 457.3682 [M + H]+, [M − H]+, for the predicted molecular formulas C15H15O3, C18H35O5, C18H32O3, C30H50O2, and C30H49O3 indicated benzopyran, fatty acid, and triterpenes, 3,4-dihydro-1-phenyl-1H-2-benzopyran-6,7-diol 19, 9,10,18-trihydroxyoctadecanoic acid 20, 12-hydroxy-8,10-octadecadienoic acid 21, 12-oleanene-3,16-diol or 12-oleanene-3,28-diol or 13 (18)-oleanene-3,16-diol or 12-ursene-3,16-diol or 12-oleanene-3,28-diol 22, and oleanolic acid 23, respectively, were previously isolated from OEA [58].

3.2. Wound Healing

3.2.1. Wound Closure Rate

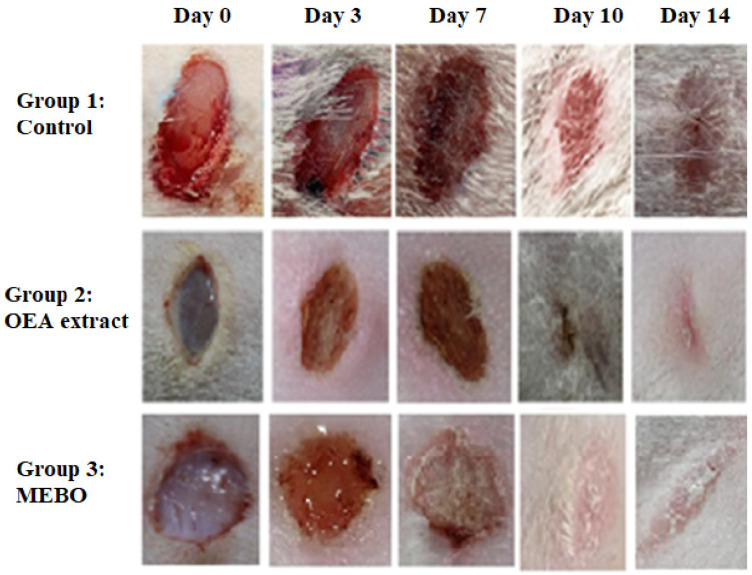

In the in vivo model, the rate of wound closure was improved in all studied groups in a time-dependent manner. On the third post-injury day, the rate of wound closure was approximately 10% in all groups, with the control group having the lowest and the treated group having the highest. There was no significant variation among groups (p < 0.05). On 7th and 10th post-excision days, the rates of wound closure in the OEA-treated group were 32% and 81%, respectively, which seemed to be statistically greater (p < 0.05) than those in the control group. The OEA group had faster wound closure than the MEBO®-treated group on the seventh and tenth days postinjury. On the fourteenth post-excision day, the rabbits treated with OEA were completely recovered from their wounds, and the wound contraction reached 100% in the OEA group (Figure 5 and Figure 6A,B).

Figure 5.

Wound closure rates were calculated using Image J software at various points (0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days) after injury in each of the three groups (n = 6).

Figure 6.

(A) Percentages of wound closure in all groups of the study (n = 6) with time after injury (0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days). A two-way ANOVA test was performed to evaluate whether there was a significant difference between the groups. The data is presented as the mean ± SD. * p < 0.05 compared to the untreated group on the same day, and # p < 0.05 compared to the MEBO® group on the same day. (B) To clarify observed differences in the shape and direction of wound contraction between groups, the wound aspect ratio was calculated (length: width).

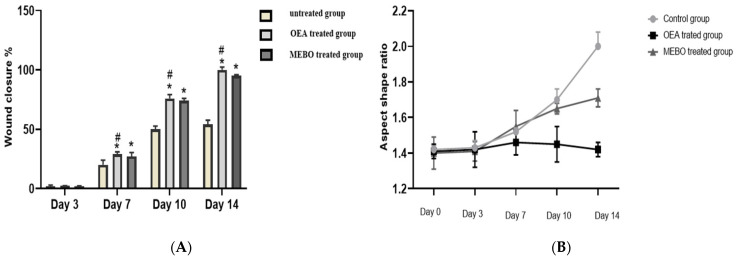

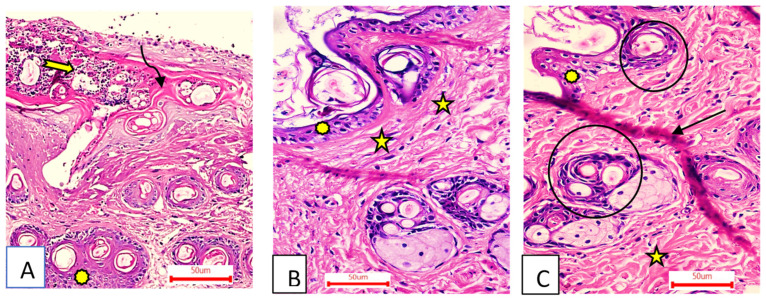

3.2.2. Histopathological Study

Seven Days Post-Treatment

Group I (control group).

The ordinary edge of the injury had a natural epidermis, normal hair follicles, well-formed collagen bundle dermis, and healthy sebaceous glands. Alternatively, the injury was packed with blood clots, inflammatory cellular infiltration, extravasated RBCs, and sloughed granulation material, with collagen tissues compactly organized in a strange pattern. The striated muscle appeared to have necrotic myo-fibers in the deepest area. (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

A sample of the wounded skin of individuals from each treatment group seven days after incision; Group I (A) showing the typical wound margin with the normal epidermis (asterisk). The wound was clogged with blood clots and granulation tissue (curved arrow). Group II (B) blood clot seen above the incision visible (curved arrow). Compactly arranged dermal collagen fibers are seen (aster). Group III (C) scar tissue (curved arrow) blocked the incision, and collagen fibers (stars) resembled the neighboring normal dermis with inflammatory cellular activity, particularly macrophages (black arrows). (H & E stain ×200).

Group II (OEA-treated).

The blood clot seen above the incision remained visible, with inadequate reepithelization, and the granulation tissue filling the defect from below was mostly cellular. In comparison to other treated groups, the heavy collagen was combined with fibers that were compactly formed in an irregular manner, leading to apparent scarring (Figure 7B).

Group III (MEBO®-treated).

Epidermal cells can be seen spreading around the edges of the incision. The re-epithelization was lacking, though. Approximately mirroring the nearby normal dermis, collagen fibers and inflammatory cells infiltration were seen populating the damage with space between them. The reticular dermis had a large number of active extended spindle-shaped fibroblasts, basophilic cytoplasm, and open-face oval nuclei. (Figure 7C).

Fourteen Days after Treatment

Group I (control group).

The wound area was larger and heavily covered in granulation tissue, which was made up of several connective tissue layers in an acidophilic matrix and covered a significant amount of inflammatory cellular infiltration. The dermis has substantial neovascularization and was made of thin, disordered collagen (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Group I (A) had a wide wound area (curved arrow), heavy inflammatory cellular infiltration in an acidophilic matrix (tailed arrow), and normal skin (asterisk). Group II (B) had an epidermis formed of 1–3 rows of epithelial cells (asterisk) and collagen fibers compactly arranged with prominent fibroblasts (stars). Group III (C) had typical epithelium, thin scar tissue extending into the dermis (black arrow), and reticular dermis with coarse, wavy collagen bundles arranged in different directions (star). Newly formed hair follicles (circles) (H&E stain ×200).

Group II (OEA-treated).

The wound had become plugged by scar tissue that had shrunk. In the epidermis, only one to three rows of epithelial cells have recovered. The granulation tissue from below was primarily cellular and fibroblast packed. Collagen fibers were disorganized–dense and compactly oriented in the reticular layer (Figure 8B).

Group III (MEBO®-treated).

The ordinary squamous keratinized epithelium was present in the skin tissue. The dermis was covered in thin scar tissue. There were numerous hair follicles, a dermal matrix with blood capillaries, and no inflammatory cellular infiltration. The collagen bundles of the papillary dermis were depicted as thin interweaving bundles, while the reticular dermis evolved into rough, wavy bundles that were established in diverse routes (Figure 8C).

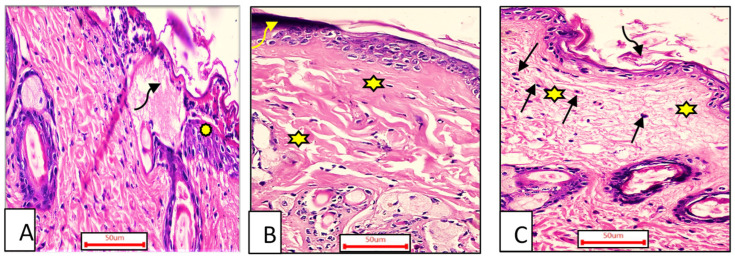

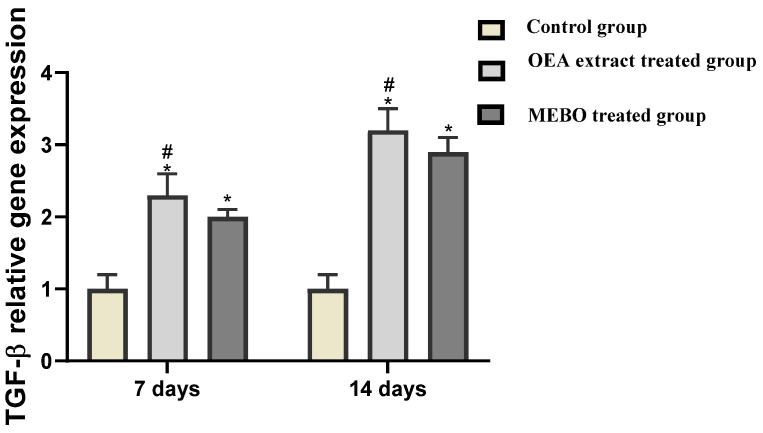

3.2.3. Effect of OEA Treatment on Relative Gene Expression of TGF-β in Excisional Wounds

The relative expression expression of TGF-β in skin tissues was significantly statistically higher in OEA-treated injuries on the seventh and fourteenth days than in individuals from the control group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, OEA-treated wounds had considerable development in the expression of the marker compared to MEBO®-treated wounds (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Gene expression in diverse categories of wounded tissues. qRT–PCR was used to examine gene expression in wound tissues. After being adjusted for GAPDH, the results displayed as fold change relative to the control group. The bars represent the mean ± SD. To determine whether there was a substantial difference between studied groups, a two-way ANOVA was performed, with * p < 0.05 comparing to the control group on a particular day and # p < 0.05 comparing to the MEBO® group on the same day.

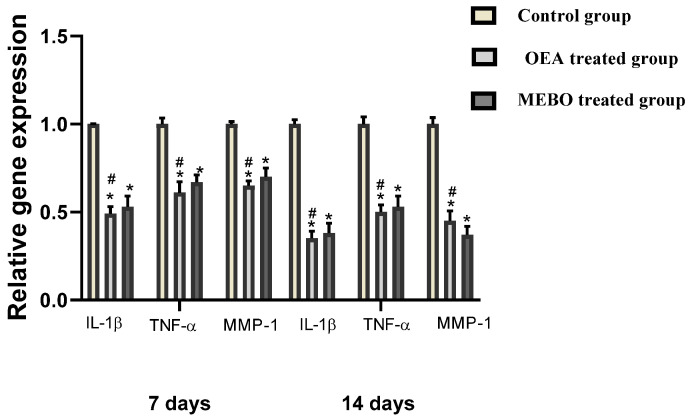

3.2.4. Effect of OEA on IL-1β, TNF-α and MMP-1 Gene Expression in Excisional Injuries

According to the analysis of mRNA levels on the seventh postinjury day, inflammatory mediators (IL-1β and TNF-α) as well as MMP-1 gene expression was dramatically downregulated in injuries treated with OEA or MEBO® comparing to control injuries (Figure 10). Wounds treated with OEA had a much more significant decrease in inflammatory markers (IL-1β and TNF-α) and MMP-1 than MEBO®-treated wounds. Furthermore, compared to control wounds, OEA or MEBO® therapy for fourteen days resulted in significantly lower TNF-α and IL-1β, MMP-1 relative gene expression (p < 0.05). Again, TNF-α, IL-1β, and MMP-1 expression were significantly lower in OEA-treated wounds than in MEBO®-treated wounds.

Figure 10.

Gene expression in wounded rabbit tissues from several groups. qRT–PCR was utilized to assess gene expression in wounded tissues. After normalization to GAPDH, the data represented as fold change relative to the control group. The bars represent the mean ± SD. To determine whether there was a significant variation between studied groups, a one-way ANOVA test was utilized, with * p < 0.05 comparing to the control group on that day and # p < 0.05 comparing to the MEBO® treated group on the same day.

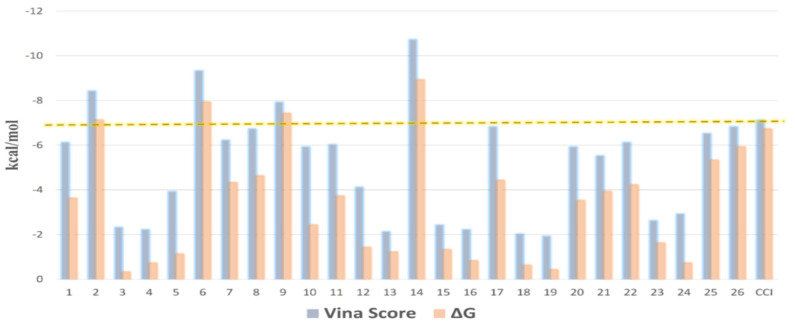

3.3. In Silico Investigation

3.3.1. Predicted Targets for Chemical Compounds in OEA

The inverse docking approach was used to accurately propose the most likely molecular targets of all the annotated compounds in OEA using the idTarget docking platform (http://idtarget.rcas.sinica.edu.tw) (accessed on 1 March 2022).

Divide-and-conquer docking is a unique docking strategy in which small overlapping grids are adaptively generated by idTarget to confine the examination area on the protein surfaces. This procedure allows the execution of many accurate dockings in a brief period of time. The query molecule can be virtually docked to practically all available crystal protein structures in the PDB.

A list of binding affinity scores, ranging from the most negative to the least, was created from the combined results. For each identified molecule in OEA, the best targets were determined using a threshold value of 7 kcal/mol for binding affinity. As an essential protein in the wound healing process, MMP1 was retrieved as a target protein for compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 with binding affinity scores of −9.3, −8.8, −8.1, and −12.7 kcal/mol, respectively. Several earlier studies have demonstrated that the healing of wounds is adversely affected by MMPs. Hence, using MMP inhibitors has been shown to result in outstanding outcomes in wound healing.

All molecules were then re-docked toward the active site of MMP1 using AutoDock Vina. It was also revealed by the Vina docking results that compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 were the structures reaching the highest-ranking scores, with binding affinity scores between −7.9 and −10.3 kcal/mol. After that, the molecular dynamic simulation-derived binding free energies (ΔGs) of all compounds were also calculated to further support the docking results. Once again, compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 were the top-scoring structures, with ΔG values between −7.1 and −8.9 kcal/mol (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Docking scores of compounds 1–26 inside the active site of MMP1 along with their calculated ΔGs. The −7 kcal/mol score was set as a cutoff to select the best hits. CCl = co-crystalized ligand.

3.3.2. Binding Mode Investigation, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and In Vitro Validation

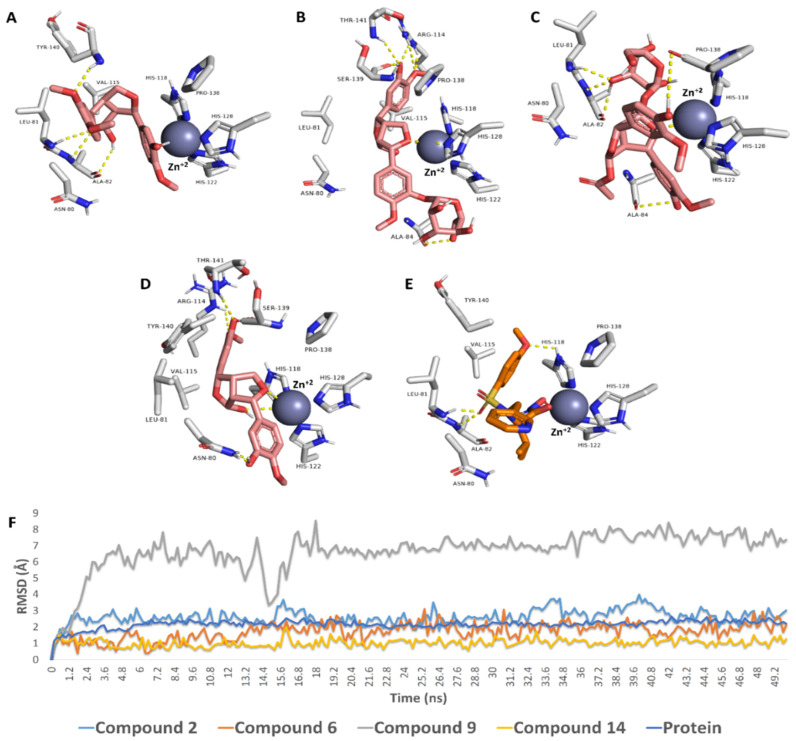

The binding orientations of compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 (common lignans in olive; [37]) inside the binding site of MMP1 were quite similar to that of the co-crystallized ligand [59] (Figure 12). LEU-81, ALA-82, and HIS-118 are critical residues involved in hydrogen bond interactions with the co-crystalized inhibitor (Figure 12A), while VAL-115, HIS-118, and TYR-140 are critical residues implicated in hydrophobic interactions. The binding modes of compounds 2 and 8 were quite similar to that of the co-crystalized ligand, where they were H-bonded to LEU-81 and ALA-82. Moreover, they established additional H-bonds with ALA-84, PRO-138, and TYR-140 (Figure 12A,C). They also established hydrophobic interactions identical to those of the cocrystalized inhibitor. They took a slightly different orientation regarding compounds 5 and 12. Both established a network of strong H-bonds (<2 Å) with ALA-84, ARG-114, PRO-138, SER-139, and THR-141 (Figure 12B,D). They established several hydrophobic interactions similar to those of the cocrystalized inhibitor. Additionally, they interacted with both PRO-138 and VAL-115.

Figure 12.

Binding poses of compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 within the potential active site of MMP1 (A–E) and that of the cocrystalized inhibitor I. The RMSDs of compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 within the potential active site of MMP1 over 50 ns of MDS (F).

We exposed the selected docked compounds to 50 ns molecular dynamic simulations (MDS) to validate these binding poses. Compounds 2, 5, and 12 achieved stable binding throughout the course of MDS with low deviations from their original pose (average RMSD ranged from 1 Å for compound 12 to 3 Å for compound 2). On the other hand, compound 8 was far less stable during MDS, where it was highly fluctuating inside the binding pocket of MMP1, particularly at the beginning of the simulation until 19.2 ns, and its overall RMSD was relatively high (~6 Å).

As a validation step of the previous in silico and modeling outcomes, OEA was tested in vitro against MMP-1. The results showed that the OEA crude extract had MMP-1 inhibitory activity with IC50 = 88 ± 0.1 µM. This potent activity could be attributed to compounds 2, 5, 8, and 12 being significant components in OEA (peak area > 10,000).

4. Discussion

Arbequina is an olive variety that has picked up insufficient attention. Reflecting the results from the present study and the literature, different phytochemical compounds were identified from the OEA crude leaf extract, consisting of lignans, secoiridoid, triterpenes, fatty acids, megaritolactones, benzopyrene, flavonoids, and phenyl ethanoids [43]. The identified phytochemical compounds showed significant differences compared with 32 cultivars (Bouteillan, Fecciaro, Frantoio selection, Manzanilla, Nocellara del belice, Picudo de Labata, I-79, Pendolino, O. europaea subsp. Cuspidata, isolate Yunnan, Ascolana tenera, Zhonglan, Koroneiki, Arbequina, Huaou 5, Nikitskii I, Picholine, Chemlal de Kabylie, Hojiblanca, Manzanilla sevillana, Canino, Cipressino, Rosciola, Nevadillo fino, Castellana, Neral, Olivon de Roda, Largueta, Manzanilla Greece, Blanqueta, Benizar, Morcona, and Gentile di chieti, which are mainly collected from France, Italy, China, Spain, Greece, Azerbaijan, and Algeria), especially in the lignans and secoiridoid content, which are predominant in OEA crude extract [60]. The major class of phenolics (i.e., flavonoids, iridoids, triterpenes, and fatty acids) displayed the same profiles as those reported in the literature. However, the phenolic profiles of olive leaves previously detected in several common cultivars were marginally distinct from those found in this work [61].

Wound healing is a network-dynamic procedure of bringing back tissue construction in damaged tissues close to its probable ordinary state [62]. This requires three phases: (1) an inflammatory stage that involves a section of proinflammatory mediators and suppression of the immune system, (2) a proliferative stage in which fibroblast proliferation, collagen aggregation, and new blood vessel formation occurs, and (3) a remodeling stage that involves wounded tissue regeneration and reconstruction [63,64]. For efficient treatment, remedies that hasten wound healing with potential involvement in all process phases, fewer side effects, and limited cost are needed.

In this work, a significant contraction in the wounded area of excision wounds of experimental animals was revealed compared to the control wounds in topical OEA treatment. These observations are due to the accelerated wound contraction rate in OEA-treated animals. To speed up and encourage wound closure, wound contraction is the centripetal movement of the wound’s margins [65,66,67]. Wound contraction therefore indicates re-epithelialization, keratinocyte differentiation, granulation, fibroblast proliferation, and proliferation [67]. The obtained results agree with other works [68,69,70,71].

Complex interactions between cells and numerous growth factors are required during wound healing processes [72]. Throughout the phases of wound healing, TGF-β has an extremely urgent role in the inflammation and hemostasis stage. Inflammatory cells like neutrophils and macrophages are attracted to and stimulated by TGF-β. At the same time, multiple cellular activities, such as angiogenesis, re-epithelialization, granulation tissue growth, and ECM deposition, are orchestrated by it during the proliferative phase [72]. Fibroblasts are encouraged to multiply and diversify into myofibroblasts that participate in the remodeling stage of wound contraction [73]. Pastar et al. and Haroon et al. argued that chronic wounds usually exhibit diminished TGF-β1 signaling [74,75]. Feinberg et al. clarified that TGF-β1 attenuates the expression of collagenases, weakening collagen and ECM [76]. These notes are consistent with our observations, which concluded that enhanced TGF-β1 expression following OEA topical application hastens wound healing, as noticed by the gene expression and the accelerated wound healing in this study (Figure 9).

Proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α are only important during the initial response of skin wound healing in the inflammatory phase. Adequate TNF-α and IL-1β expression is required for neutrophil recruitment and the cleanup of the wound area to get rid of bacteria and other contaminants. Additionally, these inflammatory mediators are considered potent MMP inducer in fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. The damaged ECM is degraded and eliminated by MMP to facilitate wound repair [77]. Nevertheless, prolonged inflammation stage results in a deformative healing process, as proteinases and cytokines damage the tissue, resulting in the progress of chronic wounds. TNF-α is a crucial proinflammatory cytokines secreted by macrophages, which, along with IL-1β, hinders collagen production and fibroblast proliferation [78]. TNF-α activates NF-κB, which in round activates a multitude of proinflammatory cytokines encompassing proteases, such as MMP and TNF-α itself, to give rise to free soluble TNF-α. As a result, these inflammatory cytokine effects are potentiated [79]. Thus, suppressing TNF-α and IL-1β by OEA could suppress prolonged inflammation and avoid defective wound healing (Figure 10). These investigations made us assume that OEA quickens and improves the curing process.

Conversely, area, collagen disruption, and hence ECM destruction could be stimulated by reactive oxygen species at high levels in the wounded area. Events like angiogenesis and re-epithelization, which are crucial for wound healing, are reduced when the ECM is damaged [80,81]. Furthermore, inflammation can be induced by elevated ROS, increasing proinflammatory cytokines, and as result lengthening inflammation [82]. Due to its SOD activity and H2O2 scavenging activity, OEA may have antioxidant properties. This was confirmed by in vitro antioxidant studies, potentially eliminating ROS, and enhancing wound-healing properties. The phenolic contents of OEA are responsible for these antioxidant actions [43].

Additionally, persistent inflammation results in wound healing failure, and wounds typically start a pathological state that requires more aggressive treatments. The capability of an agent to deal with the inflammatory wound process will either improve or quicken the healing process [83]. As opposed to that, MMPs have been proven to have a crucial impact in wound healing, and their inhibition has been associated with significant positive outcomes. The ability of some lignan-related compounds (2, 5, 8, and 12) to interact with MMP-1 was revealed by an in silico investigation of the OEA primary metabolites. As a validation step, OEA was tested in vitro against MMP-1. The results showed that the OEA crude extract had MMP-1 inhibitory activity with IC50 = 88 ± 0.1.

5. Conclusions

As presented here, the Arbequine olive leaves extracts, have a different phytochemical composition. Through an increased rate of wound closure, enhancement of TGF-1, and suppression of inflammatory markers (TNF- and IL-1), this extract demonstrated outstanding wound healing activity. The ability of some lignan-related molecules (2, 5, 8, and 12) to interact with MMP-1 was suggested by a series of virtual screening and physics-based experiments, which were conducted to explore the binding modes of molecules within the potential active site of each molecular target. This study reflected the potential of Arbequina cultivars as a source of polyphenolic wound healers, like wild cultivars.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R25), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This publication was supported by the AlMaarefa University researchers supporting program (grant number: MA-006), AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/metabo12090791/s1, Supplementary file. References [84,85,86,87] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.-W., A.H.E., T.S.A., A.M.S., M.E.-S., S.S. and U.R.A.; Methodology, M.M.G., A.H.E., S.A.M., D.H.A.-B., E.A.S. and M.A.; Data analysis, M.M.A.-S., E.M.M., A.H.E., S.H., E.A.S. and A.K.E.-D.; Investigation, M.M.A.-S., M.M.G., D.H.A.-B., M.A.E., E.A.S. and E.M.O.; Project administration, M.M.A.-S. and U.R.A.; Writing—original draft, M.E.-S., A.H.E., S.A.M., D.H.A.-B., M.M.G. and M.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.H.E., M.M.A.-S., E.M.M., S.H., A.K.E.-D., E.A.S. and E.M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to Ethics Committee, Faculty of Pharmacy, Deraya University, which signed this study, indicating that animals should not compete during any stage of investigation, and they should be cared for in conformity with the Catalog for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (ethical approval number: 8/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in article and supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the interpretation was set up without any commercial or economic relationships that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R25), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benbow M. Using Debrisoft [R] for wound debridement: Maureen Benbow briefly considers different methods of wound debridement and focuses on the advantages associated with a novel, alternative method of debridement. J. Commun. Nurs. 2011;25:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benbow M. Wound care: Ensuring a holistic and collaborative assessment. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2011;16((Suppl. 9)):S6–S16. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.Sup9.S6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boakye Y.D., Agyare C., Ayande G.P., Titiloye N., Asiamah E.A., Danquah K.O. Assessment of wound-healing properties of medicinal plants: The case of Phyllanthus muellerianus. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:945. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace H.A., Basehore B.M., Zito P.M. Wound Healing Phases. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coger V., Million N., Rehbock C., Sures B., Nachev M., Barcikowski S., Wistuba N., Strauß S., Vogt P.M. Tissue concentrations of zinc, iron, copper, and magnesium during the phases of full thickness wound healing in a rodent model. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019;191:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1600-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowden L., Byrne H., Maini P., Moulton D. A morphoelastic model for dermal wound closure. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2016;15:663–681. doi: 10.1007/s10237-015-0716-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y., Harvey B.P., Hong F., Ruzek M., Wang J., Murphy E.R., Kaymakcalan Z. Adalimumab induces a wound healing profile in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa by regulating macrophage differentiation and matrix metalloproteinase expression. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021;141:2730–2740.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkedal-Hansen H.W.G.I., Moore W.G.I., Bodden M.K., Windsor L.J., Birkedal-Hansen B., DeCarlo A., Engler J.A. Matrix metalloproteinases: A review. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sternlicht M.D., Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;17:463. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagase H., Woessner J.F. Matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Warhi T., Zahran E.M., Selim S., Al-Sanea M.M., Ghoneim M.M., Maher S.A., Mostafa Y.A., Alsenani F., Elrehany M.A., Almuhayawi M.S., et al. Antioxidant and Wound Healing Potential of Vitis vinifera Seeds Supported by Phytochemical Characterization and Docking Studies. Antioxidants. 2022;11:881. doi: 10.3390/antiox11050881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsenani F., Ashour A.M., Alzubaidi M.A., Azmy A.F., Hetta M.H., Abu-Baih D.H., Elrehany M.A., Zayed A., Sayed A.M., Abdelmohsen U.R., et al. Wound Healing Metabolites from Peters’ Elephant-Nose Fish Oil: An In Vivo Investigation Supported by In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:605. doi: 10.3390/md19110605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Çakan D., Uşaklıoğlu S. The effect of locally administered phenytoin on wound healing in an experimental nasal septal perforation animal model. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2022;279:3511–3517. doi: 10.1007/s00405-022-07276-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H.-E., Kim J.-Y., Jeong S.-W., Nah S.-Y. Effect of gintonin on matrix metalloproteinase-9 concentration in tears during corneal wound healing in rabbits. Acta Vet. Hung. 2021;68:364–369. doi: 10.1556/004.2020.00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budovsky A., Yarmolinsky L., Ben-Shabat S. Effect of medicinal plants on wound healing. Wound Repair Regener. 2015;23:171–183. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maver T., Maver U., Stana Kleinschek K., Smrke D.M., Kreft S. A review of herbal medicines in wound healing. Int. J. Derm. 2015;54:740–751. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopinath D., Ahmed M.R., Gomathi K., Chitra K., Sehgal P., Jayakumar R. Dermal wound healing processes with curcumin incorporated collagen films. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1911–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babu M.K., Vamsikrishan B., Murthy T. Formulation & Evaluation of Centella asiatica extract impregnated Collagen Dermal Scaffolds for Wound healing. Int. J. Pharmtech. Res. 2011;3:1382–1391. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachin J., Neetesh J., Tiwari A., Balekar N., Jain D. Simple evaluation of wound healing activity of polyherbal formulation of roots of Ageratum conyzoides Linn. Asian J. Res. Chem. 2009;2:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oryan A., Naeini A.T., Nikahval B., Gorjia E. Effect of aqueous extract of Aloe vera on experimental cutaneous wound healing in rat. Vet. Arh. 2010;80:509–522. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandran V., Amritha T., Sujatha R., Pandimadevi M. Collagen-Azadirachta indica (Neem) Leaves Extract Hybrid Film as a Novel Wound Dressing: In vitro Studies. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2015;32:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motealleh B., Zahedi P., Rezaeian I., Moghimi M., Abdolghaffari A.H., Zarandi M.A. Morphology, drug release, antibacterial, cell proliferation, and histology studies of chamomile-loaded wound dressing mats based on electrospun nanofibrous poly (ɛ-caprolactone)/polystyrene blends. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B. 2014;102:977–987. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma A., Khanna S., Kaur G., Singh I. Medicinal plants, and their components for wound healing applications. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021;7:53. doi: 10.1186/s43094-021-00202-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patankar S.B. Herbal Composition for the Treatment of Wound Healing, a Regenerative Medicine. 8,709,509. U.S. Patent. 2014 April 29;

- 25.Jewo P.I., Fadeyibi I.O., Babalola O.S., Saalu L.C., Benebo A.S., Izegbu M.C., Ashiru O.A. A comparative study of the wound healing properties of moist exposed burn ointment (MEBO) and silver sulphadiazine. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters. 2009;22:79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Susalit E., Agus N., Effendi I., Tjandrawinata R.R., Nofiarny D., Perrinjaquet-Moccetti T., Verbruggen M. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: Comparison with Captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jemai H., El Feki A., Sayadi S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein from olive leaves in alloxan-diabetic rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:8798–8804. doi: 10.1021/jf901280r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L., Geng C., Jiang L., Gong D., Liu D., Yoshimura H., Zhong L. The anti-atherosclerotic effect of olive leaf extract is related to suppressed inflammatory response in rabbits with experimental atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008;47:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s00394-008-0717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santiago-Mora R., Casado-Díaz A., De Castro M., Quesada-Gómez J. Oleuropein enhances osteoblastogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis: The effect on differentiation in stem cells derived from bone marrow. Osteoporos. Int. 2011;22:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuck K.L., Hayball P.J. Major phenolic compounds in olive oil: Metabolism and health effects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002;13:636–644. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(02)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vossen P.M. Organic Olive Production Manual. UCANR Publications; Davis, CA, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockwood R. Olives: Crop Production Science in Horticulture 18. Exp. Agric. 2009;45:513. doi: 10.1017/S0014479709990342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturzenberger N., Flynn D., Clow E. Super-High-Density Olive Production in California. UC Davis Olive Center; Davis, CA, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kailis S., Harris D.J. Producing Table Olives. Landlinks Press; Melbourne, Australia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukesi M., Iweriebor B.C., Obi L.C., Nwodo U.U., Moyo S.R., Okoh A.I. The activity of commercial antimicrobials, and essential oils and ethanolic extracts of Olea europaea on Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2019;19:34. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukamoto H., Hisada S., Nishibe S. Lignans from bark of the Olea plants. I. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1984;32:2730–2735. doi: 10.1248/cpb.32.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen R.W., Mier W., Giacosa A., Hull W.E., Spiegelhalder B., Bartsch H. Identification of lignans as major components in the phenolic fraction of olive oil. Clin. Chem. 2000;46:976–988. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/46.7.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mousouri E., Melliou E., Magiatis P. Isolation of megaritolactones and other bioactive metabolites from ‘megaritiki’table olives and debittering water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:660–667. doi: 10.1021/jf404685h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigakou A., Diamantakos P., Melliou E., Magiatis P. S-(E)-Elenolide: A new constituent of extra virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019;99:5319–5326. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melguizo-Rodríguez L., de Luna-Bertos E., Ramos-Torrecillas J., Illescas-Montesa R., Costela-Ruiz V.J., García-Martínez O. Potential Effects of Phenolic Compounds That Can Be Found in Olive Oil on Wound Healing. Foods. 2021;10:1642. doi: 10.3390/foods10071642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romero M.P., Tovar M.J., Girona J., Motilva M.J. Changes in the HPLC phenolic profile of virgin olive oil from young trees (Olea europaea L. Cv. Arbequina) grown under different deficit irrigation strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:5349–5354. doi: 10.1021/jf020357h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandhu S.K., Kumar S., Raut J., Singh M., Kaur S., Sharma G., Roldan T.L., Trehan S., Holloway J., Wahler G. Systematic Development and Characterization of Novel, High Drug-Loaded, Photostable, Curcumin Solid Lipid Nanoparticle Hydrogel for Wound Healing. Antioxidants. 2021;10:725. doi: 10.3390/antiox10050725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musa A., Shady N.H., Ahmed S.R., Alnusaire T.S., Sayed A.M., Alowaiesh B.F., Sabouni I., Al-Sanea M.M., Mostafa E.M., Youssif K.A., et al. Antiulcer potential of Olea europea l. Cv. arbequina leaf extract supported by metabolic profiling and molecular docking. Antioxidants. 2021;10:644. doi: 10.3390/antiox10050644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elmaidomy A.H., Alhadrami H.A., Amin E., Aly H.F., Othman A.M., Rateb M.E., Hetta M.H., Abdelmohsen U.R., Hassan H.M. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of terpene-and polyphenol-rich Premna odorata leaves on alcohol-inflamed female wistar albino rat liver. Molecules. 2020;25:3116. doi: 10.3390/molecules25143116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elmaidomy A.H., Mohammed R., Owis A.I., Hetta M.H., AboulMagd A.M., Siddique A.B., Abdelmohsen U.R., Rateb M.E., El Sayed K.A., Hassan H.M. Triple-negative breast cancer suppressive activities, antioxidants and pharmacophore model of new acylated rhamnopyranoses from Premna odorata. RSC Adv. 2020;10:10584–10598. doi: 10.1039/D0RA01697G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari K.S., Shivakrishna P., Ganduri V.R. Wound healing Activities of the bioactive compounds from Micrococcus sp. OUS9 isolated from marine water. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020;27:2398–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elmaidomy A.H., Abdelmohsen U.R., Alsenani F., Aly H.F., Shams S.G.E., Younis E.A., Ahmed K.A., Sayed A.M., Owis A.I., Afifi N., et al. The anti-Alzheimer potential of Tamarindus indica: An in vivo investigation supported by in vitro and in silico approaches. RSC Adv. 2022;12:11769–11785. doi: 10.1039/D2RA01340A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Abdel-Rahman I.M., Mustafa M., Mohamed S.A., Yahia R., Abdel-Aziz M., Abuo-Rahma G.E.-D.A., Hayallah A.M. Novel Mannich bases of ciprofloxacin with improved physicochemical properties, antibacterial, anticancer activities and caspase-3 mediated apoptosis. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;107:104629. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J.-C., Chu P.-Y., Chen C.-M., Lin J.-H. idTarget: A web server for identifying protein targets of small chemical molecules with robust scoring functions and a divide-and-conquer docking approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W393–W399. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sayed A.M., Alhadrami H.A., El-Hawary S.S., Mohammed R., Hassan H.M., Rateb M.E., Abdelmohsen U.R., Bakeer W. Discovery of two brominated oxindole alkaloids as Staphylococcal DNA gyrase and pyruvate kinase inhibitors via inverse virtual screening. Microorganisms. 2020;8:293. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8020293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bendini A., Cerretani L., Carrasco-Pancorbo A., Gómez-Caravaca A.M., Segura-Carretero A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A., Lercker G. Phenolic molecules in virgin olive oils: A survey of their sensory properties, health effects, antioxidant activity and analytical methods. Overv. Last Decade Alessandra. Mol. 2007;12:1679–1719. doi: 10.3390/12081679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edgecombe S.C., Stretch G.L., Hayball P.J. Oleuropein, an antioxidant polyphenol from olive oil, is poorly absorbed from isolated perfused rat intestine. J. Nutr. 2000;130:2996–3002. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damak N., Allouche N., Hamdi B., Litaudon M., Damak M. New secoiridoid from olive mill wastewater. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012;26:125–131. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.535147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dini I., Graziani G., Fedele F.L., Sicari A., Vinale F., Castaldo L., Ritieni A. Effects of Trichoderma biostimulation on the phenolic profile of extra-virgin olive oil and olive oil by-products. Antioxidants. 2020;9:284. doi: 10.3390/antiox9040284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai F., Liu Y., Hettiarachichi D.S., Wang F., Li J., Sunderland B., Li D. Ximenynic acid regulation of n-3 PUFA content in liver and brain. Lifestyle Genom. 2020;13:64–73. doi: 10.1159/000502773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jimenez-Lopez C., Carpena M., Lourenço-Lopes C., Gallardo-Gomez M., Lorenzo J.M., Barba F.J., Prieto M.A., Simal-Gandara J. Bioactive compounds and quality of extra virgin olive oil. Foods. 2020;9:1014. doi: 10.3390/foods9081014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olmo-García L., Kessler N., Neuweger H., Wendt K., Olmo-Peinado J.M., Fernández-Gutiérrez A., Baessmann C., Carrasco-Pancorbo A. Unravelling the distribution of secondary metabolites in Olea europaea L.: Exhaustive characterization of eight olive-tree derived matrices by complementary platforms (LC-ESI/APCI-MS and GC-APCI-MS) Molecules. 2018;23:2419. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L., Wesemann S., Krenn L., Ladurner A., Heiss E.H., Dirsch V.M., Atanasov A.G. Erythrodiol, an olive oil constituent, increases the half-life of ABCA1 and enhances cholesterol efflux from THP-1-derived macrophages. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:375. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moy F.J., Chanda P.K., Chen J.M., Cosmi S., Edris W., Skotnicki J.S., Wilhelm J., Powers R. NMR solution structure of the catalytic fragment of human fibroblast collagenase complexed with a sulfonamide derivative of a hydroxamic acid compound. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7085–7096. doi: 10.1021/bi982576v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang C., Xin X., Zhang J., Zhu S., Niu E., Zhou Z., Liu D. Comparative evaluation of the phytochemical profiles and antioxidant potentials of olive leaves from 32 cultivars grown in China. Molecules. 2022;27:1292. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oliveira A.L., Gondim S., Gómez-García R., Ribeiro T., Pintado M. Olive leaf phenolic extract from two Portuguese cultivars–bioactivities for potential food and cosmetic application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:106175. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diegelmann R.F., Evans M.C. Wound healing: An overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front. Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landén N.X., Li D., Ståhle M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:3861–3885. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krzyszczyk P., Schloss R., Palmer A., Berthiaume F. The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:419. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pachuau L. Recent developments in novel drug delivery systems for wound healing. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1895–1909. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suguna L., Singh S., Sivakumar P., Sampath P., Chandrakasan G. Influence of Terminalia chebula on dermal wound healing in rats. Phytother. Res. 2002;16:227–231. doi: 10.1002/ptr.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang T., Yin L., Yang J., Shan G. Emodin, an anthraquinone derivative from Rheum officinale Baill, enhances cutaneous wound healing in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;567:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koca U., Süntar I., Akkol E.K., Yılmazer D., Alper M. Wound repair potential of Olea europaea L. leaf extracts revealed by in vivo experimental models and comparative evaluation of the extracts’ antioxidant activity. J. Med. Food. 2011;14:140–146. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erdogan I., Bayraktar O., Uslu M.E., Tuncel Ö. Wound healing effects of various fractions of olive leaf extract (OLE) on mouse fibroblasts. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018;23:14217. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elnahas R.A., Elwakil B.H., Elshewemi S.S., Olama Z.A. Egyptian Olea europaea leaves bioactive extract: Antibacterial and wound healing activity in normal and diabetic rats. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2021;11:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verdú-Soriano J., de Cristino-Espinar M., Luna-Morales S., Dios-Guerra C., Caballero-Villarraso J., Moreno-Moreno P., Casado-Díaz A., Berenguer Pérez M., Guler-Caamaño I., Laosa-Zafra O., et al. Superiority of a Novel Multifunctional Amorphous Hydrogel Containing Olea europaea Leaf Extract (EHO-85) for the Treatment of Skin Ulcers: A Randomized, Active-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:1260. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wankell M., Munz B., Hübner G., Hans W., Wolf E., Goppelt A., Werner S. Impaired wound healing in transgenic mice overexpressing the activin antagonist follistatin in the epidermis. EMBO J. 2001;20:5361–5372. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beer H.-D., Gassmann M.G., Munz B., Steiling H., Engelhardt F., Bleuel K., Werner S. Expression and function of keratinocyte growth factor and activin in skin morphogenesis and cutaneous wound repair. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2000;5:34–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pastar I., Stojadinovic O., Yin N.C., Ramirez H., Nusbaum A.G., Sawaya A., Patel S.B., Khalid L., Isseroff R.R., Tomic-Canic M. Epithelialization in wound healing: A comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care. 2014;3:445–464. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haroon Z.A., Amin K., Saito W., Wilson W., Greenberg C.S., Dewhirst M.W. SU5416 delays wound healing through inhibition of TGF-β activation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002;1:121–126. doi: 10.4161/cbt.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feinberg R.A., Kim I.S., Hokama L., De Ruyter K., Keen C. Operational determinants of caller satisfaction in the call center. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000;11 doi: 10.1108/09564230010323633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schultz G.S., Ladwig G., Wysocki A. Extracellular matrix: Review of its roles in acute and chronic wounds. World-Wide Wounds. 2005;2005:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sasaki M., Kashima M., Ito T., Watanabe A., Izumiyama N., Sano M., Kagaya M., Shioya T., Miura M. Differential regulation of metalloproteinase production, proliferation and chemotaxis of human lung fibroblasts by PDGF, interleukin-1β and TNF-α. Mediat. Inflamm. 2000;9:155–160. doi: 10.1080/09629350020002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sano C., Shimizu T., Tomioka H. Effects of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor on the tumor necrosis factor-alpha production and NF-κB activation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Cytokine. 2003;21:38–42. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4666(02)00485-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Siwik D.A., Pagano P.J., Colucci W.S. Oxidative stress regulates collagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase activity in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C53–C60. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang F., Cui J., Liu X., Lv B., Liu X., Xie Z., Yu B. Roles of microRNA-34a targeting SIRT1 in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2015;6:195. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh K., Agrawal N.K., Gupta S.K., Sinha P., Singh K. Increased expression of TLR9 associated with pro-inflammatory S100A8 and IL-8 in diabetic wounds could lead to unresolved inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases with impaired wound healing. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2016;30:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Houghton P., Hylands P., Mensah A., Hensel A., Deters A. In vitro tests and ethnopharmacological investigations: Wound healing as an example. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chow E., Rendleman C.A., Bowers K.J., Dror R.O., Hughes D.H., Gullingsrud J., Shaw D.E. Desmond Performance on a Cluster of Multicore Processors. D. E. Shaw Research; New York, NY, USA: 2008. DE Shaw Research Technical Report DESRES/TR--2008-01. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R.D., Kalé L., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ngo S.T., Tam N.M., Pham M.Q., Nguyen T.H. Benchmark of popular free energy approaches revealing the inhibitors binding to SARS-CoV-2 mpro. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:2302–2312. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in article and supplementary material.