Abstract

The Aspergillus nidulans xlnB gene, which encodes the acidic endo-β-(1,4)-xylanase X24, is expressed when xylose is present as the sole carbon source and repressed in the presence of glucose. That the mutation creAd30 results in considerably elevated levels of xlnB mRNA indicates a role for the wide-domain repressor CreA in the repression of xlnB promoter (xlnBp) activity. Functional analyses of xlnBp::goxC reporter constructs show that none of the four CreA consensus target sites identified in xlnBp are functional in vivo. The CreA repressor is thus likely to exert carbon catabolite repression via an indirect mechanism rather than to influence xlnB expression by acting directly on xlnB.

Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) is a regulatory mechanism that results in the repression of the synthesis of enzymes required for the utilization of certain carbon sources, such as xylan, when preferred carbon sources (e.g., glucose) are available. In the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans, such repression is mediated by the product of the regulatory gene creA, which encodes a wide-domain repressor that has been shown to function by binding to DNA targets conforming to the consensus sequence 5′-SYGGRG-3′ via a pair of zinc fingers of the Cys2His2 type (2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 20). CreA homologues have also been found in other filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma reesei (9, 35). The in vivo function of some CreA target sites has been formally demonstrated in the cases of the A. nidulans alcA, alcR, prnB, prnD, and xlnA genes (5, 18, 20, 26–28) and also in the case of the T. reesei xyn1 gene (24). A class of mutations in the A. nidulans creA gene designated creAd lead to the derepression of various enzymatic activities; one of them, creAd30, is the result of an inversion that truncates the gene (1) and yields a strongly derepressed phenotype. Mutant strains bearing this allele have been widely used to study the role of CreA in CCR.

At present there are only two metabolic systems for which detailed knowledge of the mode of action of CreA has been obtained. The first involves the A. nidulans ethanol utilization pathway. In the presence of glucose, CreA represses transcription of the alcR gene, which encodes the specific transactivator (AlcR) of the genes of the ethanol regulon, by binding to the corresponding CreA target sites located in its promoter (18, 20, 25, 26). In addition, it has been shown that CreA also directly represses the promoters of the structural genes alcA, aldA, alcS, and alcO (17, 20, 25, 28), thus constituting a “double-lock” mechanism of repression of these genes (12). Other genes in the ethanol regulon show different patterns of regulation, and CreA is unlikely to play a direct role in the repression of alcM and alcU. AlcR alone probably controls the expression of these genes, their CreA-mediated CCR being effected simply due to the lack of induction by AlcR as a consequence of repression of alcR by CreA (17). It has also been suggested that CreA acts by two different mechanisms in the alcA and alcR promoters: direct binding to its target sites presumably interfering with the general transcriptional machinery, and competition with AlcR for the same DNA target region where AlcR and CreA binding sites overlap (25, 26).

The second well-studied example of regulation by CreA is that of the A. nidulans proline gene cluster, which comprises the genes encoding enzymes involved in proline utilization. The functionality of CreA target sequences in the prnB-prnD intergenic region has been investigated. The derepressing point mutations (G4→A[G-to-A transitions in the fourth position]) prnd20 and prnd22 define two adjacent, divergent, physiological CreA binding sites necessary for CCR to occur (5, 34). In contrast to alcR, expression of the gene encoding the specific prn transactivator PrnA is not repressed by glucose (4). Thus, CCR of the prn cluster by CreA occurs at only a single level by direct repression of the structural genes (i.e., no double lock).

In order to use xylan as a carbon source, saprophytic microorganisms synthesize endo-β-(1,4)-xylanases (EC 3.2.1.8), which cleave the β-(1,4) glycosidic bond between xylose units in the xylan backbone to produce xylo-oligosaccharides, and β-xylosidases (EC 3.2.1.37), which cleave xylo-oligosaccharides to yield xylose (3). When grown on the latter polysaccharide, A. nidulans synthesizes three endo-β-(1,4)-xylanases, named X22, X24, and X34 (subscripts refer to their molecular masses in kilodaltons) (13–16), and one β-xylosidase (21). The corresponding genes, named xlnA, xlnB, xlnC, and xlnD, respectively, have been cloned and characterized (22, 29, 30). Similarly to the above-mentioned cases of metabolic pathways involved in the utilization of alternative carbon sources, expression of the genes encoding the xylanolytic complex of A. nidulans may be expected to be regulated by both pathway-specific induction and CCR. Indeed, transcription of the xlnA, xlnC, and xlnD genes is under the control of these two regulatory mechanisms: specific induction in the presence of xylan or xylose mediated by the Zn(II)2Cys6 DNA-binding protein product of the xlnR gene (E. Tamayo and M. Orejas, unpublished data) and CCR mediated by CreA (22, 27, 30). Differences in the mode of regulation, particularly regarding CCR in certain culture conditions, have been detected in the case of X24 (31). In addition, the xlnA and xlnB genes are differentially regulated by ambient pH via the wide-domain zinc finger transcription factor PacC (23). In a recent study, we showed that CreA appears to play a dual role repressing xlnA transcription both by direct binding to the consensus site xlnA.C1 (5′-CTGGGG-3′), located 253 bp upstream of the ATG translational initiation codon, and by an as yet uncharacterized indirect mechanism of repression (27). To investigate whether the existence of these two levels of repression by CreA is a common mechanism controlling expression of the genes encoding the xylanolytic complex or whether there are differences in their gene regulation, we have extended these studies to the xlnB gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli DH5α [endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 supE44 recA1 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15)] was used for plasmid propagation and expression of the glutathione S-transferase (GST)::CreA (35–240∗) fusion protein (20). A. nidulans wild-type biA1 was obtained from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT2544) and used as a reference strain. A. nidulans creAd30, biA1 and creAd30 pabaB22 strains were gifts from H. N. Arst, Jr. A. nidulans argB2 metG1 biA1 was used as the recipient for transformations with argB-carrying plasmids. Strains sVAL040, sVAL040-mC1/C2, sVAL040-mC3/C4, sVAL040-mC1/C2/C3/C4 (creA+ argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1, carrying various alleles of the xlnB promoter [xlnBp]::goxC [see below]), AR39 (creAd30 pabaB22 argB2/argB+ xlnBp::goxC), and AR42 (creAd30 argB2/argB+ xlnBmC1/C2/C3/C4::goxC) were constructed during this work. Transformations were carried out as described by Tilburn et al. (36), selecting for arginine prototrophy. Single-copy integrations at the argB locus were established by Southern blotting. Sexual crosses between sVAL040 and the creAd30 pabaB22 strain were performed as detailed by Orejas et al. (27). For transfer experiments, minimal medium (32) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) Casamino Acids and 0.1 or 1% (wt/vol) fructose as the sole carbon source was inoculated with 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 conidiospores/ml and incubated for 17 h at 37°C with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. Mycelia were harvested, washed with sterile growth medium lacking a carbon source, and transferred to inducing (1% [wt/vol] xylose instead of fructose) and inducing/repressing (1% [wt/vol] xylose, 1% [wt/vol] glucose) media, in which they were incubated for a further 1, 2, 4, or 6 h at 37°C. For acid, alkaline, and neutral conditions, the above media were buffered with sodium phosphate as described by Pérez-González et al. (30).

General nucleic acid procedures.

DNA manipulations were carried out using standard methods as described by Sambrook et al. (33). DNA probes were prepared by the random hexanucleotide priming method (11). Isolation of total RNA and Northern analysis were done as described previously (27). Hybridizations were done using a 189-nucleotide xlnB-specific probe generated by PCR and a similarly labeled 830-nucleotide KpnI-NcoI acnA fragment.

For electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), overlapping subfragments of the xlnB upstream region were analyzed. Fragments 1B (−647 to −372; positions are given relative to the ATG codon), 2B (−448 to −340), 3B (−372 to −133), 4B (−174 to +5), 5B and m5B (−633 to −497), and 6B and m6B (−328 to −79) were end labeled by filling the protruding ends using Klenow DNA polymerase in the presence of [α32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). The remaining steps were carried out as detailed by Orejas et al. (27).

gox reporter construction.

Six hundred thirty base pairs of the DNA sequence (xlnBp) immediately upstream of the xlnB translation initiation codon were amplified by PCR using primers XS24 (5′-ATACTCGAGGTACCATAGGATCCAGACATCACACGC-3′) and XN24 (5′-GGAATGCATGTTGCCGG-3′). Both primers were designed to contain regions of complementarity (underlined) to the extremities of the portion of xlnBp chosen for analysis and in addition were extended by sequences encoding restriction enzyme sites to facilitate cloning. In the case of XN24, three bases immediately downstream of the ATG were mutated in order to introduce an NsiI site. The A. niger goxC structural gene was amplified from pIM503 (6) by PCR using the primers GOX1 (5′-CATCATGCATACTCTCC-3′) and GOX2 (5′-CTGCTCGAGTATAACGAACG-3′) (the regions of exact complementarity to the goxC sequence are underlined). The resulting PCR products were individually cloned into pGEM7 using XhoI and NsiI to yield plasmids pEA4 and pVALGOX, respectively. The xlnBp sequence of pEA4 was checked to ensure the absence of PCR-induced mutations. The xlnB and goxC XhoI/NsiI fragments were subsequently cloned into XhoI-cut pGEM7 in a triple-point ligation to generate pVAL036, in which the xlnBp fusion to goxC resides on an XhoI fragment. Sequencing was done to ensure correct in-frame ligation between the promoter and structural gene. Finally, the XhoI fragment from pVAL036 was cloned into BamHI-cut pIJ16 (19) after blunt ending using Klenow enzyme, yielding pVAL040. Deletion constructs of pVAL040 were prepared using an exonuclease III-S1 nested deletion kit (Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids from colonies yielding suitable deletion fragments were subsequently sequenced to establish the precise extent of the deletion. Glucose oxidase (GOX) activity was assayed 6 h after transfer from 0.1% (wt/vol) fructose to 1% (wt/vol) xylose with or without 1% (wt/vol) glucose essentially as described by Orejas et al. (27). Assays were performed at acid pH (pH 5) except in experiments including creAd30 strains, for which neutral conditions (pH 6.5) were used because of the tendency of these strains to overacidify the glucose media. Assays were done in triplicate.

Point mutations within the CreA consensus binding sites.

G4→A mutations of the CreA consensus binding sites (underlined in the sequences below) were introduced by PCR amplification of promoter sequences using oligonucleotides carrying the mutations. The double mutation xlnB.mC3mC4 was generated by amplifying a 129-bp fragment with oligonucleotides XS24 and XLNB122 (5′-GGAGATATCTTCGGCAGAAG-3′) and a 463-bp fragment with oligonucleotides XLNB143 (5′-GGAGATATCTCCATACGTACCGAAGGC) and XLNB545/563 (5′-CGTCCATCATATGATACCTGAGGGTACTGCTGACTGTGAGGAC) from pBA4. The PCR products were digested with BamHI plus EcoRV and with EcoRV plus PstI, and the isolated fragments, 105 and 157 bp, respectively, were ligated to BamHI/PstI-cut pEA4 in a triple-point ligation to obtain pR5. The double mutation xlnB.mC1mC2 was introduced by digesting the 463-bp PCR fragment with PstI and NdeI and ligating the resultant 289-bp fragment to PstI/NdeI-cut PEA4 to obtain pR2. The quadruple mutant xlnB.mC1mC2mC3mC4 was obtained after ligation of the two PCR fragments digested with BamHI plus EcoRV (105 bp) and with EcoRV plus NdeI (446 bp), respectively, to BamHI/NdeI-cut pEA4 in a triple-point ligation to obtain pR4. Plasmids pR2, pR4, and pR5 were subsequently digested with BamHI and NsiI to isolate the 638-bp fragments that were ligated to BamHI/NsiI-cut pVAL040 to yield plasmids pR8, pR9, and pR7, respectively. PCR fragments were sequenced to ensure the absence of additional mutations.

RESULTS

Transcription of xlnB is induced by xylose and repressed by CreA in the presence of glucose.

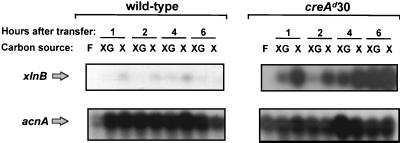

Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1) was used to analyze xlnB gene expression. Mycelia from the A. nidulans creA+ biA1 (wild-type) strain and the glucose-derepressed creAd30 biA1 mutant (1) were transferred in parallel from 1% (wt/vol) fructose medium to 1% (wt/vol) xylose medium containing (inducing/repressing conditions) or lacking (inducing conditions) 1% (wt/vol) glucose. RNAs were isolated from mycelial samples taken 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after transfer. In the wild-type strain, xlnB expression is induced during the first hour after transfer to inducing conditions, though much more weakly than expression of genes encoding other enzymes of the xylanolytic complex (22, 23, 27, 30; our unpublished data). In the presence of glucose, this expression is partially repressed. xlnB transcription in the creAd30 mutant is strongly induced by xylose within 1 h of transfer, and xlnB transcript levels remain considerably higher than those in the wild type for the following 5 h. In the presence of glucose, xlnB transcription in this mutant appears to be progressively derepressed during the 6 h after transfer. These data are consistent with a role for CreA in the glucose repression of xlnB transcription. No induction of xlnB occurs in the absence of xylose. Thus, xylose is required for the induction of xlnB transcription, and the creAd30 mutation does not obviate this requirement.

FIG. 1.

Northern blot analyses. In experiments carried out in parallel, RNA was isolated from A. nidulans wild-type and creAd30 mutant strains after 17 h of growth in 1% (wt/vol) fructose (F) and subsequent transfer to 1% (wt/vol) xylose (X) or 1% (wt/vol) xylose–1% (wt/vol) glucose (XG) for 1, 2, 4, or 6 h. The xlnB blots shown were derived from a single gel blotted to a single membrane which was hybridized with the xlnB-specific probe. The acnA (actin) blots, used as loading controls, were similarly obtained, using the same RNA aliquot for gel loading as that used to obtain the xlnB blot. The Northern gel and blotting analyses were all performed in parallel.

The GST::CreA (35–240∗) fusion protein binds in vitro to xlnBp.

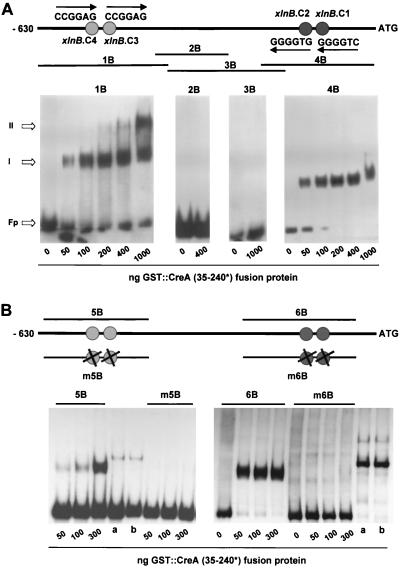

Sequence analysis (23) of the 630 bp upstream of the xlnB translational start site (xlnBp) revealed the presence of four putative CreA binding sites, designated xlnB.C1 (position −89 relative to the ATG codon), xlnB.C2 (position −107), xlnB.C3 (position −515), and xlnB.C4 (position −536). These sites occur as two pairs of direct repeats, one pair on the coding strand and the other on the noncoding strand. Nucleic acid-protein binding assays were performed using different amounts of GST::CreA (35–240∗) fusion protein (20) and four overlapping fragments into which xlnBp was divided (Fig. 2A). Fragments 2B and 3B do not contain any consensus CreA target sites, and as expected, no retardation complexes were detected in the EMSA, even when large amounts of the fusion protein were used. Fragments 1B and 4B each contain two consensus CreA binding sites. Using more than 200 ng of fusion protein, two complexes were formed with 1B; use of less protein yielded only one complex. One retardation complex was obtained with fragment 4B even when a large excess of fusion protein was used. Specific binding to the four consensus targets was confirmed by the reduced affinity of the CreA fusion protein for fragments m5B and m6B, which contain point mutations (G4→A) at the fourth position of each of the core sites, compared to the binding observed for nonmutated fragments 5B and 6B (Fig. 2B). These data are consistent with the possibility that CreA could directly mediate CCR of xlnB transcription by binding to cognate sites in xlnBp.

FIG. 2.

EMSA of xlnB upstream sequences (xlnBp). (A) Four overlapping DNA fragments (1B to 4B) were tested with increasing amounts of the fusion protein. Fp indicates free probe; I and II indicate positions of the retardation complexes. (B) Fragments 5B and 6B, containing the pairs of sites xlnB.C3-xlnB.C4 and xlnB.C1-xlnB.C2, respectively, together with fragments m5B and m6B containing the corresponding point mutations (G4→A) at the fourth position of the hexanucleotide consensus, were tested with 50, 100, and 300 ng of the GST::CreA fusion protein. As an internal control, the same amount of a GST::PacC fusion protein was tested with fragments 5B and 6B (lanes a) and also with fragments m5B and m6B (lanes b). The relative positions and sequences of the four consensus CreA target sites are indicated above the gels and in the text.

Extent of xlnB repression by CreA.

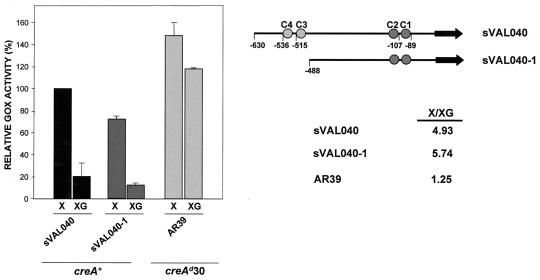

To investigate the role of CreA in the repression of xlnB expression, a reporter plasmid (pVAL040) comprising xlnBp driving the A. niger goxC gene (encoding GOX) and carrying the selectable A. nidulans argB gene was constructed and used to transform an A. nidulans argB2 mutant strain. Arginine prototrophic transformants were obtained, and one (sVAL040) carrying a single copy of pVAL040 at the argB locus was chosen for further study. In agreement with the Northern blot data, GOX activity in sVAL040 was induced in the presence of xylose and partially repressed in the presence of glucose (Fig. 3), indicating that functional elements for xylose induction and glucose repression are present in the 630-bp xlnBp fragment and regulate the GOX reporter at the ectopic argB locus similarly to the xlnB structural gene. Under inducing conditions, the GOX activity of an A. nidulans transformant (sVAL040-1) in which 142 bp of xlnBp sequence distal to goxC was deleted with the consequent removal of the xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4 sites was about 70% of that attained by sVAL040, indicating the possible deletion of a positively acting element. Little difference in the xylose/xylose-glucose GOX activity ratios was observed between strains sVAL040 and sVAL040-1, suggesting that sites xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4 are not important for CreA repression of xlnBp.

FIG. 3.

Effect of the creAd30 background on GOX activity. GOX activities (averages and standard deviations) in sVAL040 (argB2/argB+ metG1, biA1 xlnBp::goxC), sVAL040-1 (argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1 xlnBpΔ1::goxC), and AR39 (creAd30 argB2/argB+ pabaB22 xlnBp::goxC) are shown relative to that of the sVAL040 strain in xylose. Extracts of the indicated strains were obtained 6 h after transfer to inducing (X) and inducing/repressing (XG) conditions.

To investigate the extent to which the glucose repression observed in sVAL040 (creA+ xlnBp::goxC) is in fact mediated by CreA, the GOX activity of the reporter construct was assayed in the creAd30 genetic background (strain AR39 [creAd30 xlnBp::goxC]). Under inducing/repressing conditions, the level of GOX activity attained was approximately 80% of that reached under inducing conditions, suggesting a major role for CreA (Fig. 3). Residual glucose repression of about 20% is evident, which may be explained by different mechanisms.

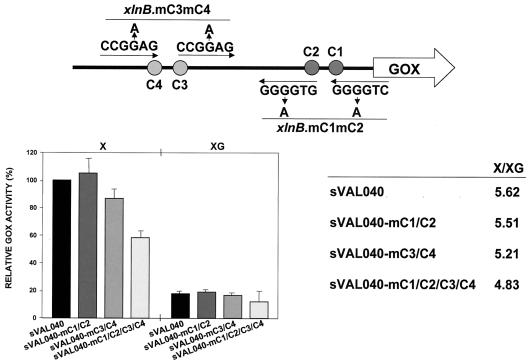

The four putative CreA target sites in xlnBp lack physiological relevance.

To minimize possible collateral effects of the deletion mutation on the induction by xylose (see above), site-destroying (Fig. 2B) point mutations (G4→A) were introduced into pVAL040 by PCR to test the in vivo functionality of the four putative CreA binding sites in xlnBp. Plasmids pR7, mutated in both the xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4 sites, pR8, mutated in both xlnB.C1 and xlnB.C2, and pR9, mutated in all four sites, were generated (see Materials and Methods for details). Sequencing of all PCR products confirmed the absence of unintended PCR-induced mutations. A. nidulans transformant strains sVAL040-mC3/C4 and sVAL040-mC1/C2, containing single copies of plasmids pR7 and pR8 integrated at the argB2 locus, were assayed for GOX activity under inducing and inducing/repressing conditions (Fig. 4). Under inducing conditions, transformant strains sVAL040, sVAL040-mC1/C2, and sVAL040-mC3/C4 produced similar levels of GOX activity, indicating that none of the mutations resulted in large effects on xylose induction. In contrast, reduced levels of GOX activity were observed in the quadruple mutant sVAL040-mC1/mC2/mC3/mC4 (contains plasmid pR9). Under inducing/repressing conditions, the point-mutated strains produced reduced levels of GOX activity similar to the sVAL040 level, indicating an unexpected lack of function in vivo of the four CreA sites in xlnBp. That transformant strain sVAL040-mC1/C2/C3/C4 failed to show derepressed levels of GOX activity under inducing/repressing conditions indicates the absence of synergistic interactions among the four sites. These data are therefore consistent with the existence of a mechanism(s) involved in the CCR of xlnB transcription other than repression exerted by direct CreA binding to its cognate sites in xlnBp.

FIG. 4.

Effect on GOX reporter activity of point mutations in the four CreA consensus target sites (indicated in the schematic). GOX activities (averages and standard deviations) in sVAL040 (argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1 xlnBp::goxC), sVAL040-mC1/C2 (argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1 xlnBmC1/C2::goxC), sVAL040-mC3/C4 (argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1 xlnBmC3/C4::goxC), and sVAL040-mC1/C2/C3/C4 (argB2/argB+ metG1 biA1 xlnBmC1/C2/C3/C4::goxC) are shown relative to that of the sVAL040 strain in xylose. Extracts of the indicated strains were obtained 6 h after transfer to inducing (X) and inducing/repressing (XG) conditions.

DISCUSSION

Northern blot analysis of A. nidulans wild type (creA+) reveals that xlnB expression is induced, albeit weakly, in the presence of xylose and subject to glucose repression (Fig. 1). Thus, xlnB expression is regulated by carbon source similarly to what has been observed for the other genes (xlnA, xlnC, and xlnD) of the A. nidulans xylanolytic complex (22, 27, 30). xlnB transcript levels are considerably higher in the creAd30 mutant than in the wild type under both inducing and inducing/repressing conditions, indicating that the negative effects mediated by this repressor also occur in the presence of xylose, even when glucose is absent. This suggests a role for CreA in xlnB expression which is in apparent contradiction to data previously published by our group (31). However, those studies assayed for the presence of secreted X24 activity in xylan and xylan-glucose media by zymogram analysis after extended times in transfer media, which almost certainly resulted in derepressing conditions due to the consumption of glucose. By contrast, our present work focuses directly on the activity of xlnBp at relatively short times after transfer to inducing and inducing/repressing conditions.

There are at least three ways in which CreA could mediate glucose repression of xlnB expression: (i) by direct repression of xlnBp, (ii) indirectly by repression of the xlnR gene encoding the specific activator, or (iii) by a double-lock mechanism in which CreA represses both xlnB and xlnR independently. That there exist four potential CreA binding sites in xlnBp suggests the possibility of direct xlnB repression by CreA. Results of EMSA using subfragments of xlnBp complexed in vitro with the GST::CreA (35–240∗) fusion protein show that fragment 1B, which contains a pair of identical, directly oriented consensus sites (xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4) separated by 15 bp, forms two retardation complexes of different electrophoretic mobilities (Fig. 2). This may indicate that each site is bound by a different molecule of GST::CreA (complex I) and that when greater amounts of protein are used, both sites can be simultaneously bound by individual molecules of the CreA fusion protein (complex II). However, only one retardation complex was obtained with fragment 5B compared to the two complexes seen with the longer fragment 1B at high fusion protein concentrations. This suggests binding of the fusion protein in vitro to a nonconsensus site downstream of xlnB.C3. A similar situation has been previously reported for the ipnA gene promoter (10), which is not subject to CreA-mediated CCR.

Only one retardation complex of high electrophoretic mobility (position I) is formed with fragments 4B and 6B (Fig. 2) despite the fact that they contain a pair of canonical CreA target sites of the 5′-SYGGGG-3′ subclass separated by 12 bp. The xlnB.C1 target site (5′-CTGGGG-3′) is identical to the A. nidulans functional sites alcA.B2 (28), alcR.C3 (26), prn.3.1 (5), and xlnA.C1 (27) and also the T. reesei functional sites xyn1.2 and xyn1.3 (24). The 5′-GTGGGG-3′ xlnB.C2 site is identical to sites 2 and 4.2 in the prn intergenic region (5), B and C1 in the alcR promoter (20, 26), E in alcA (28), and E1 and E3 in the ipnA promoter (10). Comparisons of the 5′ flanking sequences of these sites suggests that CreA binding is context independent, and hence it may be expected that CreA can efficiently bind xlnB.C1 and xlnB.C2. Although the number of retardation complexes formed with one fragment usually coincides with the actual number of binding sites it contains, the binding to fragments 4B and 6B can be explained if the two sites are bound simultaneously either by a single dimeric molecule (5, 10) of the fusion protein or by two independent molecules. Steric hindrance, such that binding to one site precludes binding to the other, could also explain this result.

The physiological significance of the consensus CreA binding sites in xlnBp was studied using mutational analysis of a xlnBp::goxC reporter construct. Two results indicate that the xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4 in vitro-bound sequences are not functional in CreA-mediated CCR in vivo. The first arose from the study of strain sVAL040-1, in which sites xlnB.C3 and xlnB.C4 are deleted. The relative level of glucose-repressed GOX activity in this strain is similar to that observed in transformant strain sVAL040, in which no mutations are present in the xlnBp::goxC reporter (Fig. 3). Thus, CCR of xlnB is not affected by the loss of these two sites. Corroboration of their lack of function came from the study of strains bearing the G4→A point mutation at each site. The relative levels of GOX activity in strain sVAL040-mC3/mC4 are similar under inducing conditions and inducing/repressing conditions to the levels of GOX activity in sVAL040 (Fig. 4). To study the in vivo role of sites xlnB.C1 and xlnB.C2, G4→A point mutations were also introduced by PCR into these sites. Although the nucleotide sequence of mutant site xlnB.mC1 (5′-CTGaGG-3′) is identical to those of prnd22 and xlnA.mC1, which were used to define the functional sites prn.3.1 and xlnA.C1, respectively (5, 27), the double-mutant strain sVAL040-mC1/C2 showed relative levels of GOX activity under inducing and inducing/repressing conditions similar to those of sVAL040 (Fig. 4). These data in conjunction with the observed lack of derepression in the quadruple mutant (sVAL040-mC1/C2/C3/C4) indicate that all four CreA consensus sites in xlnBp lack physiological relevance in CCR of xlnB. The nonconsensus site detected downstream of xlnB.C3 in fragment 1B upon in vitro binding at high concentrations of GST::CreA also appears to be nonfunctional in vivo. A. nidulans transformants in which the specific xylanase gene transactivator xlnR is expressed from the constitutive gpdA promoter exhibit constitutive levels of xlnB transcript (Tamayo and Orejas, unpublished).

Comparison of the levels of GOX activity in creA+ (sVAL040) and creAd30 (AR39) backgrounds (Fig. 3) indicates the existence of an indirect mechanism of xlnB repression by CreA since mutations in the CreA consensus sites in xlnBp (Fig. 4) have no effect on the CCR of the reporter whereas the creAd30 mutation results in a significant loss of CCR. As expected, no differences in GOX activity were observed between creAd30 strains bearing the wild-type form of xlnBp (AR39) or that in which the promoter carries all four point mutations (data not shown). Whether the remaining glucose repression in the creAd30 strains (also observed in the Northern blots) results from the possibility that creAd30 is not a complete loss-of-function mutation or the influence of a second CreA-independent mechanism is unknown. In this regard, previous work by our group has demonstrated a distinct mode of regulation for the xlnA gene (encodes endoxylanase X22). Mutational analyses identified a single site, xlnA.C1, that is responsible for the direct CreA-mediated repression of xlnA in vivo (27). However, comparison of the levels of expression of reporter constructs in both creA+ and creAd30 backgrounds also indicated the existence of an indirect mechanism of repression by CreA and a possible second CreA-independent mechanism of CCR.

Analyses of xlnBp using the goxC gene as a reporter indicate that functional elements for xlnB induction and glucose repression are located within the 630 bp upstream of the ATG codon (Fig. 3). The deletion of 142 bp (sVAL040-1) results in a promoter which loses about 25% of its activity, suggesting that a positively acting regulatory element could map there. However, a negative effect of adjacent plasmid sequences cannot be ruled out. These data indicate that most of the xylose induction in xlnBp occurs downstream of position −488. van Peij et al. (37) have shown that in A. niger, the target for the specific transactivator XlnR is the sequence 5′-GGCTAAA-3′. While this sequence is absent in the A. nidulans xlnA gene, we have identified a similar sequence, 5′-GGCTATTCAG-3′, present twice in xlnAp and also in other xln promoters (27). Although none of these sequences are present in xlnBp, five similar sequences can be found, all of them downstream of position −488. Experiments are in progress to determine the target of XlnR in the A. nidulans xylanase genes.

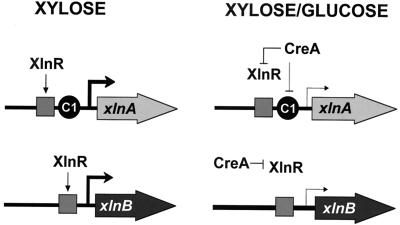

Our current model for the role of CreA in glucose repression of the A. nidulans xlnA and xlnB genes, based on the data presented here and our previous work on xlnA expression (27), is presented in Fig. 5. This model is similar to that of the A. nidulans alc regulon, where certain genes (alcA, aldA, alcS, and alcO) are under a double-lock mechanism of repression by CreA (25), while others (alcM and alcU) are not subject to direct repression (17). In the xylanolytic system, xlnA is subject to both direct and indirect CreA-mediated CCR (27) whereas the CCR exerted by CreA on xlnB is indirect. Experiments are in progress to determine whether CreA mediates CCR of xlnR.

FIG. 5.

A model for the role of CreA in the glucose repression of xlnA and xlnB gene expression. XlnR is the pathway-specific transcriptional activator. C1 represents the previously identified functional site xlnA.C1 that is responsible for direct CreA-mediated repression in vivo. See the text for further explanation. Putative interactions between specific induction by the transcriptional activator XlnR and CCR are presented.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants BIO2-CT93-0174 (BIOTECH, European Commission) to D.R. and BIO99-0844 (Programa Nacional de Biotechnología, CICYT, Spain) to M.O. A.P.M. and S.K. were recipients of an EC fellowship (BIO2-CT94-8136) and a fellowship of the Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia of the Spanish Government, respectively.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague José Antonio Pérez-González, who died on 9 August 1997.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arst H N, Jr, Tollervey D, Kelly J M. An inversion truncating the creA gene of Aspergillus nidulans results in carbon catabolite derepression. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:851–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey C, Arst H N., Jr Carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Eur J Biochem. 1975;51:573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biely P. Microbial xylanolytic systems. Trends Biotechnol. 1985;3:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazelle B, Pokorska A, Hull E, Green P M, Stanway G, Scazzocchio C. Sequence, exon-intron organization, transcription and mutational analysis of prnA, the gene encoding the transcriptional activator of the prn gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:355–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubero B, Scazzocchio C. Two different, adjacent and divergent zinc finger binding sites are necessary for CreA-mediated carbon catabolite repression in the proline gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1994;13:407–415. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Graaff L H, van den Broek H C, van Ooijen A J J, Visser J. Regulation of the xylanase-encoding xlnA gene of Aspergillus tubingensis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowzer C E, Kelly J M. Cloning of the creA gene from Aspergillus nidulans: a gene involved in carbon catabolite repression. Curr Genet. 1989;15:457–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00376804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowzer C E, Kelly J M. Analysis of the creA gene, a regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5701–5709. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drysdale M R, Kolze S E, Kelly J M. The Aspergillus niger carbon catabolite repressor encoding gene creA. Gene. 1993;130:241–245. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espeso E A, Peñalva M A. In vitro binding of the two-zinc finger repressor CreA to several consensus and non-consensus sites at the ipnA upstream region is context dependent. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinberg A P, Volgestein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felenbok B. The ethanol utilization regulon of Aspergillus nidulans: the alcA-alcR system as a tool for the expression of recombinant proteins. J Biotechnol. 1991;17:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(91)90023-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Espinar M T, Ramón D, Piñaga F, Vallés S. Xylanase production by Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;91:91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-Espinar M T, Piñaga F, Sanz P, Ramón D, Vallés S. Purification and characterization of a neutral endoxylanase from Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;113:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Espinar M T, Piñaga F, De Graaff L, Visser J, Ramón D, Vallés S. Purification, characterization and regulation of the synthesis of an Aspergillus nidulans acidic xylanase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;42:555–562. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Espinar M T, Vallés S, Piñaga F, Pérez-González J A, Ramón D. Construction of an Aspergillus nidulans multicopy transformant for the xlnB gene and its use in purifying the minor X24 xylanase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:338–341. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fillinger S, Felenbok B. A newly identified gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans comprises five novel genes localized in the alc region that are controlled both by the specific transactivator AlcR and the general carbon-catabolite repressor CreA. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:475–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5301061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hintz W E, Lagosky P A. A glucose-derepressed promoter for expression of heterologous products in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. BioTechnology. 1993;11:815–818. doi: 10.1038/nbt0793-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnstone I L, Hughes J, Clutterbuck A J. Cloning an Aspergillus nidulans developmental gene by transformation. EMBO J. 1985;4:1307–1311. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulmburg P, Mathieu M, Dowzer C E, Kelly J, Felenbok B. Specific binding sites in the alcR and alcA promoters of the ethanol regulon for the CreA suppressor mediating carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:847–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S, Ramón D. Purification and regulation of the synthesis of a β-xylosidase from Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacCabe A P, Fernández-Espinar M T, De Graaff L H, Visser J, Ramón D. Identification, isolation and sequence of the Aspergillus nidulans xlnC gene encoding the 34-kDa xylanase. Gene. 1996;175:29–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacCabe A P, Orejas M, Pérez-González J A, Ramón D. Opposite patterns of expression of two Aspergillus nidulans xylanase genes with respect to ambient pH. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1331–1333. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1331-1333.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mach R L, Strauss J, Zeilinger S, Schindler M, Kubicek C P. Carbon catabolite repression of xylanase I (xyn1) gene expression in Trichoderma reesei. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1273–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathieu M, Felenbok B. The Aspergillus nidulans CreA protein mediates glucose repression of the ethanol regulon at various levels through competition with the AlcR-specific transactivator. EMBO J. 1994;13:4022–4027. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathieu M, Fillinger S, Felenbok B. In vivo studies of upstream regulatory cis-acting elements of the alcR gene encoding the transactivator of the ethanol regulon in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:123–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orejas M, MacCabe A P, Pérez-González J A, Kumar S, Ramón D. Carbon catabolite repression of the Aspergillus nidulans xlnA gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:177–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panozzo C, Cornillot E, Felenbok B. The CreA repressor is the sole DNA-binding protein responsible for carbon catabolite repression of the alcA gene in Aspergillus nidulans via its binding to a couple of specific sites. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6367–6372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez-González J A, de Graaff L H, Visser J, Ramón D. Molecular cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of two Aspergillus nidulans xylanase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2179–2182. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2179-2182.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez-González J A, van Peij N N M E, MacCabe A P, Ramón D, de Graaff L H. Molecular cloning and transcriptional regulation of the Aspergillus nidulans xlnD gene encoding a β-xylosidase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1412–1419. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1412-1419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piñaga F, Fernández-Espinar M T, Vallés S, Ramón D. Xylanase production in Aspergillus nidulans: Induction and carbon catabolite repression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pontecorvo G, Roper J A, Hemmons L J, MacDonald K D, Bufton A W J. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–238. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fristch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sophianopoulou V, Suárez T, Diallinas G, Scazzocchio C. Operator derepressed mutations in the proline utilization gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:209–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00277114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strauss J, Mach R L, Zeilinger S, Stöffler G, Wolschek M, Hartler G, Kubicek C P. Cre1, the carbon catabolite repressor protein from Trichoderma reesei. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tilburn J, Scazzochio C, Taylor G G, Zabicky-Zissman J H, Lockington R A, Davies R W. Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene. 1983;26:205–211. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Peij N N M E, Visser J, de Graaff L H. Isolation and analysis of xlnR, encoding a transcriptional activator co-ordinating xylanolytic expression in Aspergillus niger. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:131–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]