Abstract

The family IV cellulose-binding domain of Clostridium thermocellum CelK (CBDCelK) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified. It binds to acid-swollen cellulose (ASC) and bacterial microcrystalline cellulose (BMCC) with capacities of 16.03 and 3.95 μmol/g of cellulose and relative affinities (Kr) of 2.33 and 9.87 liters/g, respectively. The CBDCelK is the first representative of family IV CBDs to exhibit an affinity for BMCC. The CBDCelK also binds to the soluble polysaccharides lichenin, glucomannan, and barley β-glucan, which are substrates for CelK. It does not bind to xylan, galactomannan, and carboxymethyl cellulose. The CBDCelK contains 1 mol of calcium per mol. The CBDCelK has three thiol groups and one disulfide, reduction of which results in total loss of cellulose-binding ability. To reveal amino acid residues important for biological function of the domain and to investigate the role of calcium in the CBDCelK four highly conserved aromatic residues (Trp56, Trp94, Tyr111, and Tyr136) and Asp192 were mutated into alanines, giving the mutants W56A, W94A, Y111A, Y136A, and D192A. In addition 14 N-terminal amino acids were deleted, giving the CBD-NCelK. The CBD-NCelK and D192A retained binding parameters close to that of the intact CBDCelK, W56A and W94A totally lost the ability to bind to cellulose, Y136A bound to both ASC and BMCC but with significantly reduced binding capacity and Kr and Y111A bound weakly to ASC and did not bind to BMCC. Mutations of the aromatic residues in the CBDCelK led to structural changes revealed by studying solubility, circular-dichroism spectra, dimer formation, and aggregation. Calcium content was drastically decreased in D192A. The results suggest that Asp192 is in the calcium-binding site of the CBDCelK and that calcium does not affect binding to cellulose. The 14 amino acids from the N terminus of the CBDCelK are not important for binding. Tyr136, corresponding to Cellulomonas fimi CenC CBDN1 Y85, located near the binding cleft, might be involved in the formation of the binding surface, while Y111, W56A, and W94A are essential for the binding process by keeping the CBDCelK correctly folded.

The cellulosome from the anaerobic thermophilic bacterium Clostridium thermocellum is a multiprotein complex capable of efficient hydrolysis of plant wall material (3–6, 12). It contains more than 26 polypeptides, the majority of which are enzymes with endo- and exoglucanase, mannanase, lichenase, xylanase, feruloyl esterase, and acetyl xylan esterase activities (4, 7, 27, 35). Catalytic components of the cellulosome are composed of at least a catalytic domain and a dockerin domain (5). The enzymes are organized into a complex by their attachment to nonhydrolytic cellulosome-integrating protein CipA, consisting of nine highly homologous cohesive domains (14) specifically binding to the dockerin domains of catalytic subunits (38, 46), a family III cellulose-binding domain (CBDCipA) (36, 42), and a special dockerin domain interacting with cell wall proteins (30). Several cellulosomal enzymes have their own CBDs belonging to different families with different expected binding properties. Among the 18 cellulosomal catalytic components whose amino acid sequences have been analyzed, eight contain CBDs (4). Thus, CbhA contains an N-terminal family IV CBD and an internal family III CBD (CBDCbhA) (52); CelK, which is highly homologous to CbhA, contains an N-terminal family IV CBD (CBDCelK) (24, 25); CelH has an internal family XI CBD (52), CelF has an internal family IIIc CBD (38); and XynZ, XynA, and XynB have internal family VI CBDs (17, 19). Representatives of family III CBDs bind to amorphous and crystalline cellulose, and some of them also bind chitin (36, 47). Family IV CBDs are known to specifically bind to soluble polysaccharides and ASC but not to crystalline cellulose (10, 18, 20, 48). Family VI CBDs found in xylanases bind to xylan and/or to amorphous cellulose (13, 45, 47). Family XI is a new family with only four representatives whose binding specificity is unknown (49). The cellulosome binds to cellulose by means of the CBDCipA (36, 42). The role of the CBDs found in some catalytic cellulosome components is not clear. These individual CBDs might be involved in tighter association between catalytic domains and cellulose-hemicellulose surfaces and/or in binding to specific parts of polysaccharides favorable for attack by a particular enzyme. However, the properties of CBDs within the catalytic subunits of the C. thermocellum cellulosome have not been studied. Only the CBDCelK has been shown to bind cellulose (24). In the present paper, we report on the properties and deletion and mutation analysis of the CBDCelK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and plasmids.

C. thermocellum JW20 was used as a source of genomic DNA. The bacterium was grown anaerobically under a nitrogen atmosphere at 60°C in prereduced medium with 1% (wt/vol) cellobiose as described earlier (25). Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3)pLys (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) was used as the cloning host for T7 RNA polymerase expression vector pET-21b(+) (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) and grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Isolation of genomic DNA from C. thermocellum.

C. thermocellum genomic DNA was isolated by the method of Marmur (32) with the modifications reported earlier (25).

Primer design, PCR, and cloning.

Flanking primers containing restriction sites were designed according to the DNA sequence of celK (25) (Table 1) and synthesized with an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer. DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using the primers in combination and purified genomic DNA as the template. PCRs were done on a 480 Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). The reactions were carried out with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The annealing temperature was 54°C, and the extension time was 2 min. PCR products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and extracted from the gel using the Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.). The extracted DNA fragments were digested with restriction enzymes and ligated to the pET-21b(+) vector linearized with the same enzymes. The ligation products were used to transform BL21(DE3)pLys competent cells. Each construct was verified by both restriction analysis and DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for cloning and site-directed mutagenesisa

| Primer | Codon change | Sequence | Restriction site | Location | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flanking | |||||

| CBDF | 5′-CTAGCTAGCTTGGAAGACAAGTCTTCAAAG-3′ | NheI | 1224–1244 | Forward | |

| CBDF1 | 5′-CTAGCTAGCGACCTTTTGTATGAAAGAACA-3′ | NheI | 1263–1283 | Forward | |

| CBDR | 5′-TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCTTACTAGAGAGATACATCATCAAG-3′ | NotI | 1712–1733 | Reverse | |

| Mutagenesis | |||||

| W56F | TGG→GCT | 5′-GGTCTTTGCTTTCCGGCTCATACTTGCGAAGACAGTGG-3′ | 1293–1330 | Forward | |

| W56R | 5′-CCACTGTCTTCGCAAGTATCAGCCGGAAAGCAAAGACC-3′ | 1293–1330 | Reverse | ||

| W94F | TGG→GCT | 5′-GACAAAGGACAAAACAAGGCTAGTGTCCAGATG-3′ | 1404–1436 | Forward | |

| W94R | 5′-CATCTGGACACTAGCCTTGTTTTGTCCTTTGTC-3′ | 1404–1436 | Reverse | ||

| Y111F | TAC→GCT | 5′-CTCGAGCAAGGACATACAGCTACGGTAAGGTTTAC-3′ | 1455–1489 | Forward | |

| Y111R | 5′-GTAAACCTTACCGTAGCTGTATGTCCTTGCTCGAG-3′ | 1455–1489 | Reverse | ||

| Y136F | TAT→GCT | 5′-GGTCAGATGGGTGAACCCGCTACTGAATATTGG-3′ | 1530–1562 | Forward | |

| Y136R | 5′-CCAATATTCAGTAGCGGGTTCACCCATCTGACC-3′ | 1530–1562 | Reverse | ||

| D192F | GAT→GCT | 5′-CCTTACTATGTTTACCTTGCTGATGTATCTCTCTACGAT-3′ | 1699–1736 | Forward | |

| D192R | 5′-ATCGTAGAGAGATACATCAGCAAGGTAAACATAGTAAGG-3′ | 1699–1736 | Reverse |

Restriction sites are underlined. Bold letters indicate stop codons. Mutations are in bold underlined letters.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Plasmid pET-21b(+) containing the DNA fragment encoding the CBDCelK served as the template for all PCRs. Amino acid residues of interest were individually changed to alanine using the oligonucleotide primers listed in Table 1. PCRs with mutagenesis primers were done using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). PCR products were used to transform BL21(DE3)pLys competent cells. Plasmid DNA in each case was isolated and sequenced. Mutants possessing the correct nucleotide changes were used for further study.

Protein purification.

The CelK proteins composed of the CBDCelK and the catalytic domain with a molecular mass of 94 kDa (CelK94) and the catalytic domain alone with a molecular mass of 74 kDa (CelK74) were purified as described earlier (24). All other proteins were purified from E. coli BL21(DE3)pLys cultures (2 liters) harboring pET-21b(+) with the DNA fragment of interest and harvested 5 h after induction with 2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. All steps were done at 4°C, except fast protein liquid column chromatography, which was run at room temperature. The cells were collected, washed with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), and disintegrated with a French press. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Ammonium sulfate was added to the clear supernatant to 40% saturation. After 2 h of stirring on ice, precipitated protein was collected by centrifugation, dissolved in a minimal volume of buffer, and dialyzed overnight. The dialyzed sample was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Cotati, Calif.) column and eluted with a gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl. Fractions containing CBDs were combined, concentrated by ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialyzed, applied to a TSK3000 SW stainless steel column (TosoHaas, Montgomeryville, Pa.), and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.1 M NaCl.

SH group estimation.

Free SH groups were identified using 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in native and denaturing buffers (1). Sodium phosphate (0.1 M; pH 8.0) was used as the native buffer. Denaturing buffer contained 6 M guanidine chloride. A412 was recorded periodically at room temperature, and the number of SH groups that reacted was determined by using a molar absorbance coefficient for nitrothiophenylate of 14,150 cm−1 M−1. In the case of denaturing buffer, an E412 of 13,700 cm−1 M−1 was used. When the absorbance reached a maximum, titration was regarded as complete.

Disulfide thiols were determined by the following procedure (2). Free SH groups in the protein were carboxymethylated by using freshly crystallized iodoacetic acid (Sigma). The reaction was done in 0.6 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.6) containing 6 M guanidine chloride at 37°C for 30 min. After extensive dialysis against 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), freshly prepared dithiothreitol was added to a final concentration of 50 mM. The sample was incubated at room temperature in a nitrogen atmosphere for 2 h. The excess dithiothreitol was eliminated by extensive dialysis against 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 6 M guanidine chloride. Reduced thiol groups were determined with DTNB as described above.

Metal content.

The metal content of proteins was determined by plasma emission spectrophotometry (Jarrell-Ash 965 ICP). Each datum point was a mean of three replicates.

Analytical gel exclusion chromatography.

The chromatographic behavior of CBDs was studied by using Superose 12 HR10/30 and Superose 6 HR10/30 columns (Pharmacia) at flow rates of 0.5 and 0.2 ml/min, respectively. The buffer used was 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 M NaCl and 0.05% NaN3. The sample volume was 100 μl. The standard proteins aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), bovine serum albumin (68 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), and cytochrome c (12.5 kDa) (Combithek; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) were used for column calibration.

Protein determination.

During purification protein was determined with Coomassie Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). In other experiments, protein concentrations were determined on the basis of A280 values. Each sample was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 60 min and then extensively dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer. The absorbance was read against dialysis buffer (used as a blank). Molar absorption coefficients (calculated from aromatic amino acid [tryptophan and tyrosine] content) were 43,400 cm−1 M−1 for the CBDCelK and D192A, cm−1 M−1 40,600 for the CBD-NCelK, 37,800 cm−1 M−1 for W56A and W94A, and 42,000 cm−1 M−1 for Y111A and Y136A. The molecular masses of the polypeptides were calculated from their deduced amino acid sequences.

Cellulose-binding assay.

Adsorption assays were done at a room temperature in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. Proteins were mixed with cellulose (1 g/liter) in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a final volume of 0.5 ml. Tube contents were continually mixed by rotation. After equilibrium for 2 h, cellulose and bound protein were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Centrifugation was repeated twice to ensure the removal of all of the cellulose. The concentration of unbound protein was then determined. The concentration of bound protein was calculated from the difference between the initial protein concentration and unbound protein. Each datum point was the mean of five replicates. Adsorption to cellulose was analyzed with the computer program GraphPad Prism using the one-side binding hyperbola equation describing the binding of a ligand to a receptor that follows the law of mass action. The fit converged for all sets of data. The algorithm minimized the sum of the squares of the actual distances of the points from the curve. To determine the relative equilibrium association constant Kr, which can be used to compare the affinities of various related ligands for a given preparation of cellulose, we used the method of Gilkes et al. (15).

Celluloses used.

Acid-swollen cellulose (ASC) was prepared by treatment of Avicel PH-101 (Fluka Chemical Group, St. Louis, Mo.) with phosphoric acid (26). Bacterial microcrystalline cellulose (BMCC) from Acetobacter xylinum was a gift from Naoki Nishimura, the general manager of the Bio-Polymer Research Co.

Affinity electrophoresis.

Affinity electrophoresis using polyacrylamide gels with polysaccharide ligands was performed as described by Tomme et al. (48), with some simplification. We used the Laemmli system for electrophoresis (29), excluding sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) from all solutions. The separating gel contained 10% acrylamide. The polysaccharides were incorporated into the gel at a concentration of 0.1% prior to polymerization. A control gel without glycan was prepared and run simultaneously. Protein samples were loaded onto gels in a standard loading buffer without SDS. Electrophoresis was run at 4°C and 100 V for 2.5 h. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

Sedimentation equilibrium centrifugation.

Sedimentation equilibrium centrifugation was performed using an XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) operated at 18,000 rpm and 20°C. After 24 h of centrifugation, the A280 was scanned in three cells. A default partial specific volume of 0.79 cm3/g and a density of 1.00 g/cm3 were used. The solvent was 0.02 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.1 M NaCl. The data were analyzed using the software supplied with the centrifuge.

CD spectra.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were carried out at 25°C on a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter with a quartz cell with a 1.0-mm path length. The cell temperature was controlled to within ±0.1°C by circulating water via a Neslab R-111 water bath through a cell jacket. The results were expressed as mean residue ellipticity (MRE), which is defined as MRE = 100MREobs/lc, where MREobs is the observed MRE in degrees, c is the residue concentration (moles per liter), and l is the light path length in centimeters. The spectra obtained were averages of five scans. The spectra were smoothed via an internal algorithm in the Jasco software package, J-700 for Windows. Secondary structure was estimated by utilizing the MRE value at 222 nm. Taking peptide length into account, %Helix = 100[MRE]/39,500(1 − 2.57/n), where n is the number of residues. All protein samples were in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) at a concentration of 10 μM.

RESULTS

Protein purification.

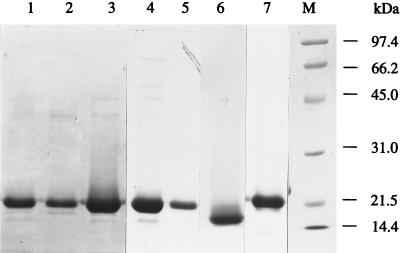

The CBDCelK, D192A, W94A, and Y136A were expressed as soluble polypeptides, while W56A and Y111A were distributed between cytosolic and inclusion body fractions. All proteins were purified from the soluble fractions close to homogeneity as revealed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of the purified CBDCelK and its deletion and mutation variants overexpressed in E. coli. Lanes: 1, CBDCelK; 2, W56A; 3, W94A; 4, Y111A; 5, Y136A; 6, CBD-NCelK; 7, D192A; M, low-range protein standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.), including phosphorylase b (97.4 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66.2 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (31 kDa), and trypsin inhibitor (21.5 kDa).

Metal content.

One mole of the CBDCelK contained 1 mol of Ca and very small amounts of Cu and Zn (Table 2). The CBDCelK tightly binds calcium. Thus, incubation of the CBDCelK with 5 mM CaCl2 or 10 mM EDTA in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) overnight at 4°C, followed by intensive dialysis against the same buffer without CaCl2 or EDTA, did not significantly affect the calcium content. Dialysis buffer was used in all cases as a blank. The calcium content of Y111A, Y136A, W56A, and W94A was similar to that of the CBDCelK. D192A contained only a trace amount of calcium (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Metals present in the recombinant CBDCelK and its mutated variants

| Variant | Amt of metal/mole of proteina

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Cu | Zn | |

| CBDCelKb | 1.03 | 0.101 | 0.095 |

| CBDCelK (CaCl2)c | 1.11 | 0.091 | 0.083 |

| CBDCelK (EDTA)d | 0.83 | 0.065 | 0.073 |

| CBDCelK (urea-EDTA)e | 0.64 | 0.072 | 0.042 |

| W56Ab | 0.87 | 0.051 | 0.063 |

| W94Ab | 1.02 | 0.087 | 0.056 |

| Y111Ab | 0.91 | 0.066 | 0.087 |

| Y136Ab | 1.11 | 0.076 | 0.088 |

| D192Ab | 0.07 | NDf | ND |

| D192A (CaCl2)c | 0.07 | ND | ND |

Metal content was determined by plasma emission spectroscopy. The results shown are averages of three determinations. In all variants, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) was used. After incubation of proteins with CaCl2 or EDTA at 4°C overnight, they were extensively dialyzed against Tris buffer without additives.

Protein was dialyzed three times against 1 liter of Tris buffer.

Protein was incubated with 5 mM CaCl2 and then dialyzed.

Protein was incubated with 5 mM EDTA and then dialyzed.

Protein was incubated with 5 mM EDTA in buffer containing 8 M urea and then dialyzed.

ND, not detected.

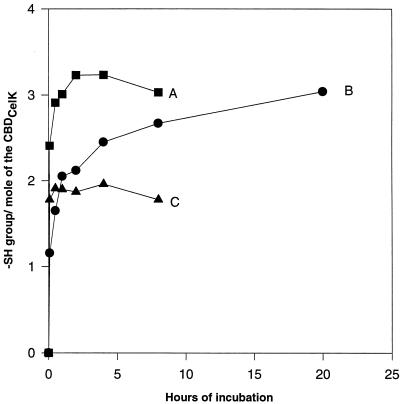

Status of thiols in the CBDCelK.

The kinetic profiles of the reaction of CBDCelK thiol groups with DTNB are given in Fig. 2. Under denaturing conditions, three SH groups were available for rapid DTNB titration. (Fig. 2A). In native buffer, one SH group reacted with DTNB within a few minutes while the second and third SH groups were more resistant and needed approximately 2 and 20 h, respectively, for a complete reaction (Fig. 2B). After carboxymethylation of the free thiols, followed by the reduction of disulfide thiols, DTNB titration revealed two additional SH groups (Fig. 2C). The results show that of the five cysteine residues of the CBDCelK, three are present as free SH groups and two form one disulfide.

FIG. 2.

DTNB titration of thiol groups in the CBDCelK. A, denaturing buffer; B, native buffer; C, DTNB titration of thiol groups in denaturing buffer after carboxymethylation of free SH groups, followed by disulfide bridge reduction (see Materials and Methods for details).

Molecular masses of CBDCelK, the CBD-NCelK and mutant CBDs.

The molecular mass of the CBDCelK calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence (amino acid residues 28 to 197) is 19,640 Da. The freshly purified CBDCelK was a monomer with a molecular mass of 21 kDa as determined by gel filtration. Chromatography of the same preparation after storage at 4°C for 3 weeks revealed a mixture with a second peak of 43 kDa corresponding to a dimer form of the CBDCelK. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis of this preparation also revealed two fractions with molecular masses of 18.9 and 39 kDa. Treatment with β-mercaptoethanol resulted in conversion of the dimer into a monomer, indicating intermolecular disulfide formation. SDS-PAGE of the dimer in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol showed a polypeptide with a molecular mass of approximately 19 kDa, and SDS-PAGE in the absence of β-mercaptoethanol showed a polypeptide of 45 kDa (data not shown). The freshly purified CBD-NCelK, D192A, Y111A, and Y136A were monomers. W56A and W94A appeared as high-molecular-mass aggregates eluting from the Superose 6 column as an irregular, broad peak between blue dextran (2,000 kDa) and ferredoxin (480 kDa). Incubation with β-mercaptoethanol resulted in partial conversion of these aggregates into monomers, suggesting that intermolecular disulfide bonds were not totally responsible for aggregate formation.

Binding to cellulose.

The fresh monomeric CBDCelK bound to both ASC and BMCC (Table 3). It bound to ASC with a capacity of 16 μmol/g of cellulose and a Kr of 2.3 liters/g. Its BMCC-binding capacity was 3.95 μmol/g of cellulose, and its Kr was 9.9 liters/g (Table 3). The dimer did not bind to cellulose (data not shown). The CBD-NCelK and D192A bound ASC and BMCC with parameters similar to those of the CBDCelK. The binding capacities and Krs of Y136A and Y111A were significantly lower. Thus, Y136A bound to ASC and BMCC with capacities of only 3.46 and 0.944 μmol/g of cellulose and Krs of 0.375 and 1.06 liters/g, respectively. Y111A bound to ASC with a capacity of 1.39 μmol/g of cellulose and an undetectable Kr and did not bind to BMCC. W56A and W94A had no ability to bind to ASC and BMCC (Table 3)

TABLE 3.

Parameters for binding of the CBDCelK and its deletion and mutation variants to ASC and BMCC calculated from adsorption data

| Protein | Capacitya (μmoles/g of cellulose); Krb (liters/g)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ASC | BMCC | |

| CBDCelK | 17.1; 2.33 | 3.95; 9.87 |

| CBD-NCelK | 16.2; 2.67 | 3.86; 11.00 |

| D192A | 15.7; 1.84 | 3.68; 6.88 |

| Y136A | 3.46; 0.38 | 0.94; 1.06 |

| Y111A | 1.39; ND | |

Maximum amount of protein bound to 1 g of cellulose.

Relative equilibrium association constant (15).

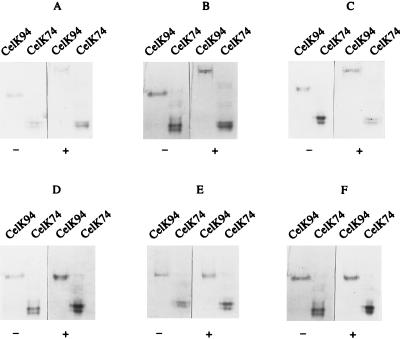

Binding to soluble polysaccharides.

Previously, we reported on the substrate specificity of CelK, which was found to hydrolyze such soluble substrates as lichenin, glucomannan, and barley β-glucan but not galactomannan and xylan. Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was hydrolyzed at a low rate (24). CBDCelK binding to polysaccharides was investigated by native PAGE with and without polysaccharides using CelK94 (with the CBDCelK) and CelK74 (composed of a single catalytic domain without the CBDCelK) (24) (Fig. 3). Comparison of the electrophoretic behaviors of proteins revealed that CelK74 mobility was not affected by the presence of any ligand. In contrast, the mobility of CelK94 in the presence of barley β-glucan, lichenin, and glucomannan was decreased in comparison with that of samples run in the presence of xylan, galactomannan, or CMC or without ligands. These results indicate that CelK74 did not bind to any of the ligands tested, whereas CelK94 bound to those ligands which were substrates for the catalytic domain, and that this binding was mediated by the CBDCelK.

FIG. 3.

Affinity electrophoresis of CelK containing a CBD (CelK94) and without a CBD (CelK74) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of barley β-glucan (0.1%, wt/vol) (A), glucomannan (0.1%, wt/vol) (B), lichenin (0.1%, wt/vol) (C), galactomannan (0.1%, wt/vol) (D), CMC (0.1%, wt/vol) (E), and birch wood xylan (0.1%, wt/vol) (F).

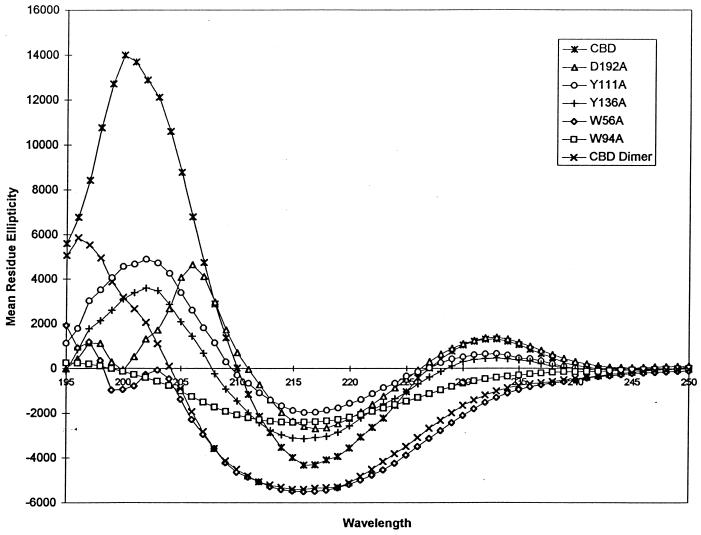

CD spectra.

The far-UV CD spectrum of the monomeric CBDCelK contained a single strong negative band with a maximum at approximately 217 nm, suggesting the presence of almost exclusively β-sheets in the secondary structure of the domain characteristic of all known CBDs. The CD spectra of the dimer and all variants, even those of the CBD-NCelK (not shown) and D192A, with properties similar to those of the wild-type CBDCelK, differed from the spectrum of the CBDCelK (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

CD spectra of the wild-type CBDCelK and mutant CBDs. The proteins were in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) at a concentration of 10 μM. Measurements were performed with a J710 spectrometer (Jasco).

DISCUSSION

To date, almost 200 CBDs have been classified, on the basis of amino acid similarities, into 13 different families. These domains vary in size, occur in different positions within the polypeptides, tend to be associated with particular families of catalytic domains, and have different binding properties (47). Analyses of three-dimensional structures revealed the folding characteristic these domains have in common. However, it has been noted that the binding surfaces vary depending on the binding specificity of the CBDs. A comparison of the crystal structure of a family III CBDCipA which binds to both amorphous and crystalline celluloses (50) with the solution structures of the family IV Cellulomonas fimi CBDN1 and CBDN2, which have specificity only to amorphous cellulose (8, 20), revealed that the cellulose-binding surfaces of these domains are different. In all cases, the binding surfaces were formed by residues typically involved in protein-carbohydrate interactions which rely on hydrophobic van der Waals forces, usually involving aromatic residues, and on hydrogen bonding networks by polar side chains. However, the binding surface of the CBDCipA was characterized by a linear and strikingly planar array of polar and aromatic residues which can be aligned with the glucose moieties of cellulose (3, 50). The family II C. fimi CBDCex (51) and the family I T. reesei CBDCBHI (28), which also bind crystalline cellulose, have similar flat binding surfaces. In contrast, the CBDN1 and the CBDN2 have binding clefts with a strip of hydrophobic amino acid residues running along the middle of the clefts (8, 20). Based on the differences between the binding surfaces of the CBDCipA and the CBDN1, an explanation of the binding specificity of the latter domain has been suggested. The hydrophobic residues that mediate binding are located within the cleft and, as a result, are unable to interact with the flat surface presented by crystalline cellulose. However, single strands of soluble polysaccharides and amorphous cellulose are able to lie within this groove (20).

In addition to the CBDN1 and the CBDN2, two other representatives of family IV, CBDs from Rhodothermus marinus Xyn1 (CBDXyn1-1 and CBDXyn1-2) do not bind to crystalline cellulose (18). It has been postulated that family IV includes CBDs with a binding cleft and the ability to bind to amorphous but not to crystalline cellulose. The family IV CBDCelK reported here is the only representative of the family with an affinity for crystalline cellulose. Correspondingly, the binding surface of the CBDCelK might be different from the binding clefts of the CBDN1 and the CBDN2, resembling the flat surface of CBDs binding to crystalline celluloses.

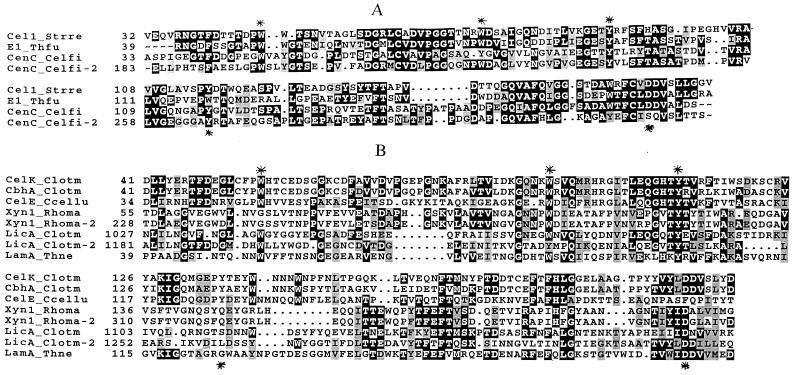

The cysteine content of the representatives of CBD family IV, except the CBDCelK and the CBDCbhA, varies from two to zero (Fig. 5A and B). The CBDN1, the CBDN2, the Streptomyces reticuli CBDCel1, and the Thermomonospora fusca CBDE1 all have two highly conserved cysteine residues (Fig. 5A). Probably all four CBDs have an internal disulfide affecting their correct folding. The CBDCelK and the CBDCbhA have five cysteine residues, none of which is aligned with the cysteine residues of the other family members (Fig. 5B). In the CBDCelK, two of the cysteine residues form an internal disulfide bond that is important for biological function of the domain. One SH group in the CBDCelK is probably on the surface of the protein, as it is immediately available for DTNB titration under native conditions. This SH group is the most likely candidate for the formation of the inactive dimer.

FIG. 5.

Alignment of family IV CBDs. A and B, subgroups IVa and IVb, respectively. Abbreviations: Cel1_Strre, Streptomyces reticuli Cel1 (accession no. X65616); E1_Thfu, Thermomonospora fusca E1 (accession no. L20094); CenC_Celfi, Cellulomonas fimi CenC (accession no. X57858); CelK_Clotm, Clostridium thermocellum CelK (accession no. AF039030); CbhA_Clotm, C. thermocellum CbhA (accession no. X80993); CelE_Ccellu, C. cellulolyticum CelE (accession no. PC1140); Xyn1_Rhoma, Rhodothermomonas marinus Xyn1 (accession no. Y11564); LicA_Clotm, C. thermocellum LicA (accession no. X89732); LamA_Thne, Thermotoga neapolitana LamA (accession no. Z47974). Conserved amino acid residues mutated in the CBDCelK are marked with asterisks.

The CBDCelK contains 1 mol of calcium per molecule. It has been indicated that calcium of CBDs may not be involved in binding to cellulose. Thus, calcium-binding sites in the CBDCipA and the CBDN1 are located apart from the cellulose-binding surfaces (20, 49). Residues ligating calcium are not conserved in many cases (21, 47, 50). Replacement of one of the calcium-ligating residues in the CBDSbpA from mesophilic C. cellulovorans did not change its binding properties (16). Elimination of a single calcium from the CBDN1 did not affect binding to cellulose (16, 20, 21). The CBDCex and the CBDN2 do not contain calcium but bind to cellulose (8, 21, 51). In contrast to the CBDN1, the CBDCelK tightly binds calcium which is similar in this regard to the CBDCipA calcium, which is bound in a cavity and is not accessible to the solvent (50). We could not obtain the apo-CBDCelK, even after treatment with EDTA under denaturing conditions. However, the calcium-free CBDCelK was obtained after mutation of Asp192 into alanine. This D192A mutant had binding parameters very close to those of the CBDCelK, thus demonstrating that calcium does not affect cellulose binding. Data on the stabilizing effect of calcium are contradictory, and the exact role of this element in CBDs is still not clear. Elimination of calcium from the CBDN1 resulted in decreased thermodynamic stability (20, 21). The postulated calcium-binding site in the CBDN1 was adjacent to the disulfide bond critical for the integrity of the native CBDN1. There is probably a combination effect of metal binding and cysteine oxidation on CBDN1 stability (11, 21). In contrast, a comparison of the highly similar CBDN1 and CBDN2 revealed that the CBDN2 is significantly more stable even though it does not bind calcium (8).

We previously showed the amino acid alignment of nine members of CBD family IV (Fig. 6 of reference 25). The alignment revealed four aromatic and one aspartic amino acid residues that are highly conserved. In the CBDCelK, these residues correspond to Trp56, Trp94, Tyr111, Tyr136, and Asp192. The mutation of the highly conserved aromatic residues in the CBDCelK resulted in significant changes in several properties of the mutant forms. W56A and W94A totally lost cellulose-binding ability. Y111 bound ASC very weakly. Y136A bound both ASC and BMCC but with significantly decreased efficiency in comparison to the CBDCelK. Expression of the CBDCelK and Y136A in E. coli yielded soluble monomeric polypeptides. W94A appeared as soluble but high-molecular-mass aggregates. W56A and Y111A were distributed between cytosolic and inclusion body fractions. Purified from the cytosolic fraction, Y111A was a monomer while W56A formed aggregates. The CD spectra of the mutant forms differed from the CD spectrum of the CBDCelK. All of these observations demonstrated structural changes in all of the mutated CBDs. We suggest that Trp56, Trp94, and Tyr111 might promote cellulose binding by keeping the domain correctly folded. Tyr136 corresponds to Tyr85 in the CBDN1, which is located in a groove near the binding cleft and was suggested to participate in the binding mechanism (20). In the CBDCelK, Tyr136 might have a surface location and be directly involved in binding to cellulose.

Based on the sequence similarities, properties, and structural data of the CBDN1 and the CBDN2, we suggest that family IV should be divided into two subfamilies, IVa and IVb (Fig. 5). Subfamily IVa includes the CBDN1, the CBDN2, the CBDE1, and the CBDCel1 (Fig. 5A). Subfamily IVb incorporates the remainder of family IV: the CBDCelK, the CBDCbhA, the two CBDs of C. thermocellum LicA (the CBDLicA-1 and the CBDLicA-2), the C. cellulolyticum CelE CBD (the CBDCeIE), the Thermotoga neapolitana LamA CBD (the CBDLamA), and the two CBDs from R. marinus (the CBDXyn1-1 and the CBDXyn1-2) (Fig. 5B). The reasons for such a classification are as follows. Subfamily IVa CBDs are over 39% homologous. They contain two highly conserved cysteine residues. Residues corresponding to those forming the binding surface in the CBDN1 are much more conserved in subgroup IVa than in IVb. The CBDN1 and the CBDN2 bind soluble polysaccharides and amorphous but not crystalline cellulose and are very similar in the topology of their binding clefts. Subfamily IVb is more heterogeneous (Fig. 5B). Sequence homology, except between the CBDCelK and the CBDCbhA, which are highly homologous (24, 25), is about 30% or less; no cysteine residues are conserved, and the number of cysteines varies. This subgroup also differs from subfamily IVa in binding specificity. Thus, the CBDXyn1-1 and the CBDXyn1-2 bind to insoluble xylan in addition to soluble polysaccharides and amorphous cellulose; the CBDCelK is remarkable for its affinity for crystalline cellulose. Determination of the three-dimensional structure of the CBDCelK, clarifying the role of its high cysteine content and the topology of its binding surface, is in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. M. Brewer for performing the sedimentation equilibrium analysis and L. S. Dure for interpretation of CD spectra. We are grateful to T. E. Davies for critical notes and suggestions.

Support by grant DE=FG02-93ER20127 from the Department of Energy is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitken A, Learmonth M. Carboxymethylation of cysteine using iodoacetamide/iodoacetic acid. In: Walker J M, editor. The protein protocols handbook. Totowa, N.J: Human Press Inc.; 1996. pp. 339–340. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitken A, Learmonth M. Estimation of disulfide bonds using Ellman's reagent. 1996. pp. 487–488. . 1996. In J. M. Walker (ed.), The protein protocols handbook. Human Press Inc., Totowa, N.J. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer E A, Morag E, Shoham Y, Tormo J, Lamed R. The cellulosome: a cell surface organelle for the adhesion to and degradation of cellulose. In: Fletcher M, editor. Bacterial adhesion: molecular and ecological diversity. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss Inc.; 1996. pp. 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer E A, Shimon L J, Shoham Y, Lamed R. Cellulosomes—structure and ultrastructure. J Struct Biol. 1998;124:221–234. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Béguin P, Lemaire M. The cellulosome: an exocellular, multiprotein complex specialized in cellulose degradation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;31:201–236. doi: 10.3109/10409239609106584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Béguin P, Alzari P M. The cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:178–185. doi: 10.1042/bst0260178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum D L, Kataeva I A, Li X-L, Ljungdahl L G. Feruloyl esterase activity of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome can be attributed to previously unknown domains of XynY and XynZ. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1346–1351. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.5.1346-1351.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brun E, Johnson P E, Creagh A L, Tomme P, Webster P, Haynes C A, McIntosh L P. Structure and binding specificity of the second N-terminal cellulose-binding domain from Cellulomonas fimi endoglucanase C. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2445–2450. doi: 10.1021/bi992079u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauvaux S, Souchon H, Alzari P M, Chariot P, Béguin P. Structural and functional analysis of the metal-binding sites of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9757–9762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coutinho J B, Gilkes N R, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G, Miller R C., Jr The binding of Cellulomonas fimi endoglucanase C (CenC) to cellulose and Sephadex is mediated by the N-terminal repeats. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1243–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creagh A L, Koska J, Johnson P E, Tomme P, Joshi M D, McIntosh L P, Kilburn D G, Haynes C A. Stability and oligosaccharide binding of the N1 cellulose-binding domain of Cellulomonas fimi endoglucanase CenC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3529–3537. doi: 10.1021/bi971983o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felix C, Ljungdahl L G. The cellulosome: the exocellular organelle of Clostridium thermocellum. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:791–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandes A C, Fontes C M G A, Gilbert H J, Hazlewood G P, Fernandes T H, Ferreira L M A. Homologous xylanases from Clostridium thermocellum: evidence for bi-functional activity between xylanase catalytic modules and the presence of xylan-binding domains in enzyme complexes. Biochem J. 1999;342:105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerngross U T, Romaniec M P M, Kobayashi T, Huskisson N S, Demain A L. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal S1-protein reveals of unusual degree of internal homology. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilkes N R, Jervis E, Henrissat B, Tekant B, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G. The adsorption of a bacterial cellulase and its two isolated domains to crystalline cellulose. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6743–6749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Mutation analysis of the cellulose-binding domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7328–7334. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7328-7334.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grépinet O, Chebrou M-C, Béguin P. Nucleotide sequence and deletion analysis of the xylanase gene (xynZ) of Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4582–4588. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4582-4588.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hachem M A, Karlsson E N, Bartonek-Roha E, Raghothama S, Simpson P J, Gilbert H J, Williamson M P, Holst O. Carbohydrate-binding modules from a thermostable Rhodothermus marinus xylanase: cloning, expression and binding studies. Biochem J. 2000;345:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi H, Takehara M, Hattori T, Kimura T, Karita S, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Nucleotide sequences of two contiguous and highly homologous xylanase genes xynA and xynB and characterization of XynA from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:348–357. doi: 10.1007/s002530051401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson P E, Joshi M D, Tomme P, Kilburn D G, McIntosh L P. Structure of the N-terminal cellulose-binding domain of Cellulomonas fimi CenC determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14381–14394. doi: 10.1021/bi961612s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson P E, Creagh A L, Brun E, Joe K, Tomme P, Haynes C A, McIntosh L P. Calcium binding by the N-terminal cellulose-binding domain from Cellulomonas fimi β-1,4-glucanase CenC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12772–12781. doi: 10.1021/bi980978x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson N E, Bartonek-Roxa E, Holst O. Cloning and sequence of a thermostable multidomain xylanase from the bacterium Rhodothermus marinus. Biochim Biohpys Acta. 1997;1353:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson N E, Bartonek-Roxa E, Holst O. Evidence for substrate binding of a recombinant thermostable xylanase originating from Rhodothermus marinus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;168:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kataeva I A, Li X-L, Chen H, Ljungdahl L G. CelK—a new cellobiohydrolase from Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome: role of N-terminal cellulose-binding domain. In: Ohmiya K, Sakka K, Karita S, Hayashi K, Kobayashi Y, Kimura T, editors. Genetics, biochemistry and ecology of cellulose degradation. Tokyo, Japan: UniPublishers Co.; 1998. pp. 454–460. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kataeva I, Li X-L, Chen H, Choi S-K, Ljungdahl L G. Cloning and sequence analysis of a new cellulase gene encoding CelK, a major cellulosome component of Clostridium thermocellum: evidence for gene duplication and recombination. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5288–5295. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5288-5295.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klyosov A A, Sinitsyn A P. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose. IV. Effect of major physico-chemical and structural features of the substrate. Bioorg Chem. 1981;7:1801–1812. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohring S, Wiegel J, Mayer F. Subunit composition and glycosidic activities of the cellulase complex from Clostridium thermocellum JW20. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3798–3804. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3798-3804.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraulis J, Clore G M, Nilges M, Jones T A, Pettersson G, Knowles J, Gronenborn A M. Determination of the three-dimensional solution structure of the C-terminal domain of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. A study using nuclear magnetic resonance and hybrid distance geometry-dynamical simulated annealing. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7241–7257. doi: 10.1021/bi00444a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leibovitz E, Béguin P. A new type of cohesin domain that specifically binds the dockerin domain of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3077–3084. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3077-3084.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lytle B, Wu J H D. Involvement of both dockerin subdomains in assembly of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6581–6585. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6581-6585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of the deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattinen M-L, Linder M, Teleman A, Annila A. Interaction between cellohexaose and cellulose binding domains from Trichoderma reesei cellulases. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattinen M-L, Linder M, Drakenberg T, Annila A. Solution structure of the cellulose-binding domain of endoglucanase I from Trichoderma reesei and its interaction with cello-oligosaccharides. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256:279–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2560279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morag E, Bayer E, Lamed R. Relationship of cellulosomal and noncellulosomal xylanases of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose-degrading enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6098–6105. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6098-6105.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morag E, Lapidot A, Govorko D, Lamed R, Wilchek M, Bayer E A, Shoham Y. Expression, purification, and characterization of the cellulose-binding domain of the scaffoldin subunit from the cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1980–1986. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1980-1986.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagy T, Simpson P, Williamson M P, Hazlewood G P, Gilbert H J, Orosz L. All three surface tryptophans in type IIa cellulose binding domains play a pivotal role in binding both soluble and insoluble ligands. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:312–316. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00625-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarro A, Chebrou M-C, Béguin P, Aubert J-P. Nucleotide sequence of the cellulase gene celF of Clostridium thermocellum. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90002-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ong E, Gilkes N R, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A, Kilburn D G. The cellulose-binding domain (CBDCex) of an exoglucanase from Cellulomonas fimi: production in Escherichia coli and characterization of the polypeptide. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;42:401–409. doi: 10.1002/bit.260420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pagès S, Bélaich A, Morag E, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Bayer E. Species-specificity of the cohesin-dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Proteins. 1997;29:517–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ponyi T, Szabo L, Nagy T, Orosz L, Simpson P J, Williamson M P, Gilbert H J. Trp22, Trp24, and Tyr8 play a pivotal role in the binding of the family 10 cellulose-binding module from Pseudomonas xylanase A to soluble ligands. Biochemistry. 2000;39:985–991. doi: 10.1021/bi9921642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poole D M, Morag E, Lamed R, Bayer E A, Hazlewood G P, Gilbert H J. Identification of the cellulose-binding domain of the cellulosome subunit S1 from Clostridium thermocellum YS. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;99:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90022-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakon J, Irwin D, Wilson D B, Karplus P A. Structure and mechanism of endo/exocellulase E4 from Thermomonospora fusca. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:810–818. doi: 10.1038/nsb1097-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson P J, Bolam D N, Cooper A, Ciruela A, Hazlewood G P, Gilbert H J, Williamson M P. A family IIb xylan-binding domain has a similar secondary structure to a homologous family IIa cellulose-binding domain but different ligand specificity. Struct Fold Des. 1999;7:853–864. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takada G, Karita S, Takeuchi A, Ahsan M M, Kimura T, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Specific adsorption of Clostridium stercorarium xylanase to amorphous cellulose and its desorption by cellobiose. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1996;60:1183–1185. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tokatlidis K, Dhurjati P, Béguin P. Properties conferred on Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelC by grafting the duplicated segment of endoglucanase CelD. Protein Eng. 1993;6:947–952. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomme P, Warren R A J, Miller R C, Jr, Kilburn D G, Gilkes N R. Cellulose-binding domains: classification and properties. In: Saddler J N, Penner M H, editors. Enzymatic degradation of insoluble carbohydrates. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1995. pp. 142–163. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomme P, Creagh A L, Kilburn D G, Haynes C A. Interaction of polysaccharides with the N-terminal cellulose-binding domain of Cellulomonas fimi CenC. 1. Binding specificity and calorimetric analysis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13885–13894. doi: 10.1021/bi961185i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomme P, Boraston A, McLean B, Kormos J, Creagh A L, Sturch K, Gilkes N R, Haynes C A, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G. Characterization and affinity applications of cellulose-binding domains. J Chromatogr. 1998;715:283–296. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tormo J, Lamed R, Chirino A J, Morag E, Bayer E A, Shoham Y, Steitz T A. Crystal structure of a bacterial family-III cellulose-binding domain: a general mechanism for attachment to cellulose. EMBO J. 1996;15:5739–5751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu G-Y, Ong E, Gilkes N R, Kilburn D G, Muhandiram D R, Harris-Brandts M, Carver J P, Kay L E, Harvey T S. Solution structure of a cellulose-binding domain from Cellulomonas fimi by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6993–7009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yagüe E, Béguin P, Aubert J-P. Nucleotide sequence and deletion analysis of the cellulase-encoding gene celH of Clostridium thermocellum. Gene. 1990;89:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zverlov V V, Velikodvorskaya G V, Schwarz W H, Bronnenmeier K, Kellermann J, Staudenbauer W L. Multidomain structure and cellulosomal localization of the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiohydrolase CbhA. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3091–3099. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3091-3099.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]