Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting technology has emerged as an ideal approach to address the challenges in regenerative dentistry by fabricating 3D tissue constructs with customized complex architecture. The dilemma with current dental treatments has led to the exploration of this technology in restoring and maintaining the function of teeth. This scoping review aims to explore 3D bioprinting technology together with the type of biomaterials and cells used for dental applications. Based on PRISMA-ScR guidelines, this systematic search was conducted by using the following databases: Ovid, PubMed, EBSCOhost and Web of Science. The inclusion criteria were (i) cell-laden 3D-bioprinted construct; (ii) intervention to regenerate dental tissue using bioink, which incorporates living cells or in combination with biomaterial; and (iii) 3D bioprinting for dental applications. A total of 31 studies were included in this review. The main 3D bioprinting technique was extrusion-based approach. Novel bioinks in use consist of different types of natural and synthetic polymers, decellularized extracellular matrix and spheroids with encapsulated mesenchymal stem cells, and have shown promising results for periodontal ligament, dentin, dental pulp and bone regeneration application. However, 3D bioprinting in dental applications, regrettably, is not yet close to being a clinical reality. Therefore, further research in fabricating ideal bioinks with implantation into larger animal models in the oral environment is very much needed for clinical translation.

Keywords: 3D bioprinting, tissue engineering, cell-laden, bioink, dental tissue regeneration

1. Introduction

Defects in the craniofacial region including the alveolar bone can occur because of periodontitis, motor vehicle accidents, tumor and genetic factors. Periodontitis is the sixth most prevalent disease worldwide and the leading cause of missing teeth, followed by caries and trauma [1,2]. The dilemma of current clinical treatments in treating periodontitis cases is that therapies cannot repair the alveolar bone destruction and restore the functionality of the periodontally involved teeth [3]. In addition, the selection case of the suitable treatment such as guided tissue generation and bone graft strongly depend on the shape and size of the osseous defects. Moreover, rehabilitating the function of the oral cavity by means of dental implant in a severely resorbed alveolar bone may pose a challenge. Several approaches have been utilized for bone regeneration, such as employing the autogenous bone block, allograft and xenograft, however, these conventional treatments come with limitations. The drawbacks of these approaches include (i) donor site morbidity, lack of tissue availability, difficulty to shape and conform to the defect, and graft resorption of the autogenous bone [4,5,6]; and (ii) high rates of infection and increase risk of host immune response caused by allograft and xenograft [7]. These clinical challenges faced by clinicians and surgeons have led to the exploration of new technology in oral tissue engineering to fabricate functional dental tissue constructs, such as periodontal ligament, dentin–pulp complex and alveolar and craniomaxillofacial bone with patient-specific shape and size [8].

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting is an emerging combination technology of 3D printing and tissue engineering [9]. It is an ideal approach to fabricating customized complex 3D tissue constructs with defect-specific architectures through computer-aided design modeling to mimic native tissues [10]. It involves layer-by-layer precise deposition of cell-laden constructs from various biomaterials, cells and bioactive molecules with spatial control of the placement of functional components onto predefined locations (extracellular matrix, cells and pre-organized microvessels) [11,12,13]. The main advantage of 3D bioprinting is its ability to control the delivery of cells and materials in complex fabricated tissue-like structures. Hence, 3D bioprinted structures can provide cell-to-cell growth interconnectivity for better tissue regeneration [14].

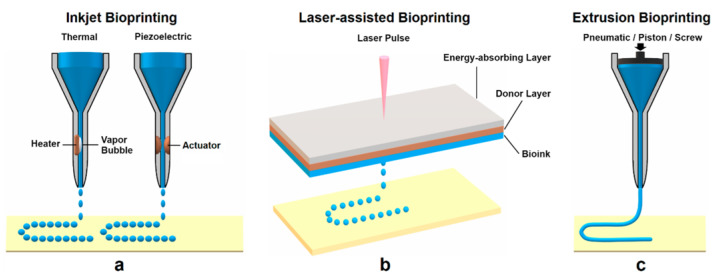

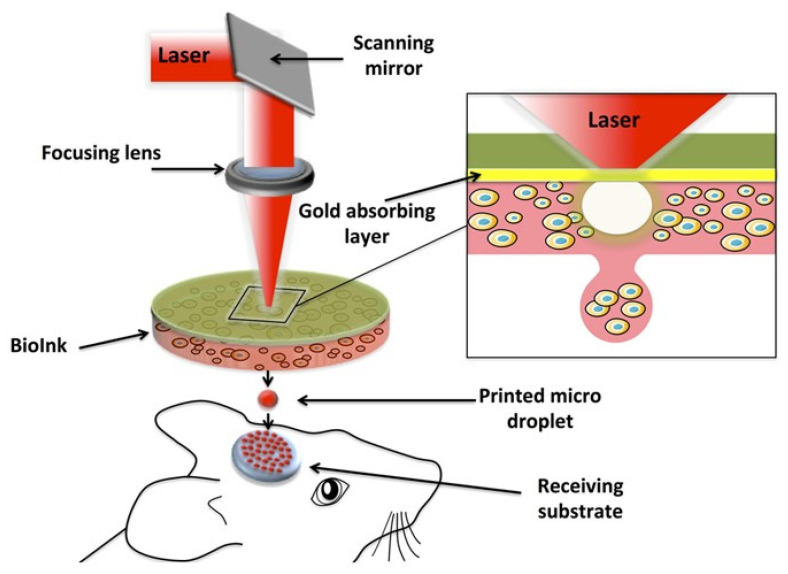

The application of 3D bioprinting techniques that are widely used includes extrusion-based [15,16], inkjet-based [17], laser-assisted [18] and stereolithography [14], as shown in Figure 1. Extrusion-based bioprinting deposits the bioink either using a pneumatic, piston or screw-based system. It is the frequently preferred strategy for the development of multilayer scaffolds in tissue engineering because of the wide range of biomaterials selected for printing, such as natural and synthetic polymers, cell-laden hydrogel and cell aggregates [19,20]. In addition, it can manage high cell density, different material viscosities and crosslinking mechanisms [21]. Meanwhile, in inkjet bioprinting or drop-on-demand technique, it utilizes heating reservoirs, piezoelectric actuators, and electrostatic or electrohydrodynamic methods in order to deposit cells and/or biomaterials in the form of droplets onto the substrates. The advantages of this technique are fast printing speed and low cost. However, nozzle clogging caused by high cell density is one of the disadvantages of this method [11]. Laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) utilizes a laser as the energy source and consists of an energy-absorbing layer, a donor ribbon and a receiving substrate [22]. This technology employs a noncontact bioprinting method and is nozzle-free, which can be used to deposit high viscosity bioink with a high resolution without nozzle clogging issues [11]. Although this approach results in high cell viability during printing, the effect of laser exposure onto the cells is still not known [23]. Stereolithography (SLA) uses ultraviolet light or an electron beam to initiate a polymerization reaction to place biomaterials onto a substrate. SLA is able to print complex architectures at extremely high resolutions. However, the drawbacks of SLA are its slow printing speed, high cost and limited selection of materials with suitable processing properties [24].

Figure 1.

Common 3D bioprinting techniques: (a) inkjet bioprinting, (b) laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) and (c) extrusion bioprinting [24].

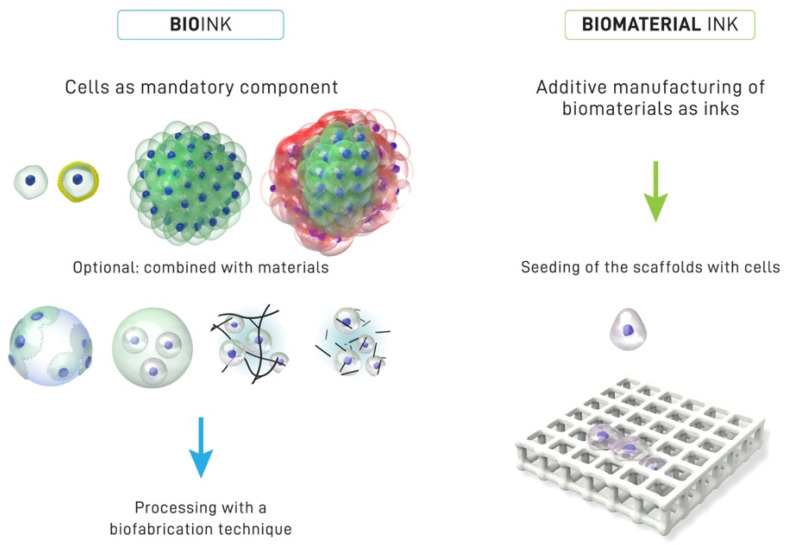

One of the important components of 3D bioprinting is the bioink because of the effect it has on the outcome of the tissue engineering technology. Bioink refers to a formulation of cells that may contain biomaterials and biologically active components suitable for processing by an automated biofabrication technology [25] (see Figure 2). The use of bioinks enables the study of the effects of geometry and spatial organization on cell behavior and function in vitro, which can later be developed into in vivo models for applications in regenerative dentistry. At present, cell printing technology has become the preferred choice for a new biofabrication approach as compared to the conventional method of seeding cells on scaffolds. Three-dimensional bioprinting techniques are now able to incorporate living cells in bioprinted scaffolds, which enhance the position of cells. However, the disadvantage of the approach using scaffolds seeded with cells is that it could cause cell loss, which leads to poor cellular performance [26].

Figure 2.

The characteristics distinction between bioink and biomaterial ink. In a bioink, cells are the mandatory component of the printing formulation, which can be in the form of single cells, coated cells and cell aggregates (one or several type of cells). The bioink may contain biomaterials and biologically active components. Meanwhile, the biomaterial ink is where the seeding cells are introduced within biomaterial scaffolds after printing. Reproduced with permission [25]. Copyright 2018 IOP publishing under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

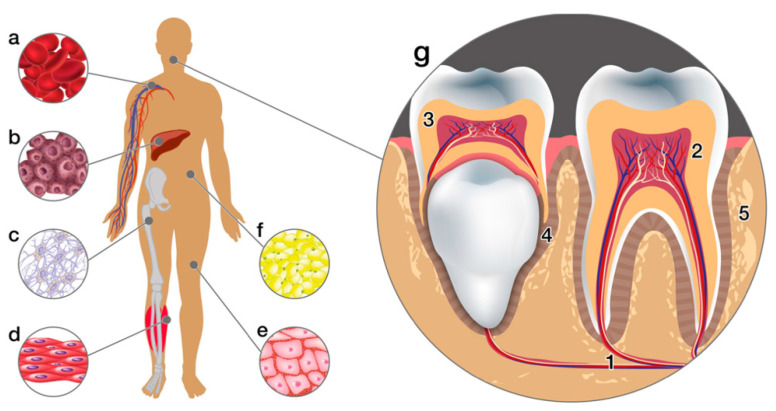

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), also known as “universal cells” are the most preferable cell source for tissue regeneration because they have self-renewal capability and can differentiate into various functional cell types under certain conditions [27,28]. MSCs can be isolated from embryonic stem cells or adult stem cells [29]. In addition, they are also easily extracted from almost all tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord and placenta), including dental tissues. Dental stem cells can be obtained from different parts of tissues such as periodontal ligaments (PDLSCs), dental pulp (DPSCs), from apical papilla (SCAPs) or exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) [28]. Rich sources of stem cells from the oral cavity have led to the great application and potential use in oral tissue engineering [28] (see Figure 3). Moreover, MSCs are also the most suitable cell source because of their immunomodulatory properties and ability to secrete protective biological factors [30,31].

Figure 3.

Sources of mesenchymal stem cells. This illustration shows human tissue sources: (a) peripheral blood, (b) liver, (c) bone marrow, (d) muscles, (e) skin, (f) adipose tissue and (g) dental tissues: (1. apical dental papilla, 2. dental pulp, 3. pulp from the exfoliated deciduous tooth, 4. periodontal ligament, 5. alveolar bone) [29].

The most common bioink materials are hydrogel-based bioprinted constructs. They have gained popularity in recent years because of similar characteristics to natural extracellular matrix (ECM), homogenous distribution of cells in the scaffolds, their ability to hold live cells, and enhancement of the cell viability in a hydrated 3D environment [32,33,34]. They can be derived from natural polymers (alginate, agarose, collagen, chitosan, gelatin, hyaluronic acid) or synthetic polymers including poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PDGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL). The advantages of natural polymers are the ability to biomimick ECM structure composition, the ability to self-assemble and also their biocompatibility [35], whereas, for synthetic polymers, they have proper degrading rate and photocrosslinking ability, which is not present in the natural polymer [36].

Three-dimensional bioprinting has emerged as a promising treatment strategy for fabricating complex biological constructs in oral tissue engineering, thus solving the issues associated with current therapies and overcoming the limitations of conventional techniques [37]. However, there is limited literature that has reported on the 3D bioprinting applications in dentistry. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to identify the gaps based on the available literature to answer the following questions: (i) How has 3D bioprinting technology been applied in dentistry? (ii) What are the types of biomaterials and cells used in 3D bioprinting?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This review implemented the methodological framework from the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews and was carried out based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) [38,39]. The research questions for this review follow: (i) How has 3D bioprinting technology been applied in dentistry? (ii) What are the types of biomaterials and cells used in 3D bioprinting?

A search of the literature published through May 2022 was performed using four databases: Ovid, PubMed, EBSCOhost and Web of Science. The following search terms were used: (“3D bioprinting” OR “3D-bioprint*” OR “3D print*” OR “3D-print*” OR “Bioprinting” OR “Three-dimensional bioprint*”) AND (“Tissue engineering” OR “Tissue regeneration” OR “Bone regeneration” OR “Regenerative medicine” OR “Periodontal regeneration” OR “Guided tissue regeneration”) AND (“Dental” OR “Dentistry”). Additional records were identified through a manual search of the references lists. The search was limited to articles in the English language and had no restriction on the time frame of publication year.

2.2. Study Selection

The initial screening of the identified studies was conducted based on the information in the titles and abstracts by two independent reviewers (N.M. and M.R.). In addition, the full text of potentially eligible studies was retrieved for further screening of their suitability determined by inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreement between reviewers on study selection was resolved by a third reviewer (N.H.A.K.) through discussion.

The inclusion criteria for the included studies were defined based on the Participant/Population (P): cell-laden 3D-bioprinted construct; Concept (C): intervention to regenerate dental tissue using bioink that incorporates living cells or also in combination with biomaterial and/or growth factors before or during printing; Context (C): application of 3D bioprinting tissue-engineered in the dental field. However, studies were excluded if they were case reports, review papers or conference abstracts. Articles that reported cell seeding of the scaffolds after printing and were not related to the dental application were also excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Extraction and synthesis of information from the included studies were summarized and presented into a table of evidence by the first reviewer (N.M.) and verified by the second reviewer (M.R.) to ensure that they were aligned with the research questions. The extracted data of the included studies were publication details (first author, year of publication and country of study), study design (in vitro and in vivo), 3D bioprinting strategy (type of 3D bioprinter and parameters of 3D printing technique), materials, type of cells, animal models characteristics (animal species, gender, age, weight and defect size), and application in dental field and outcomes of the 3D bioprinting.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

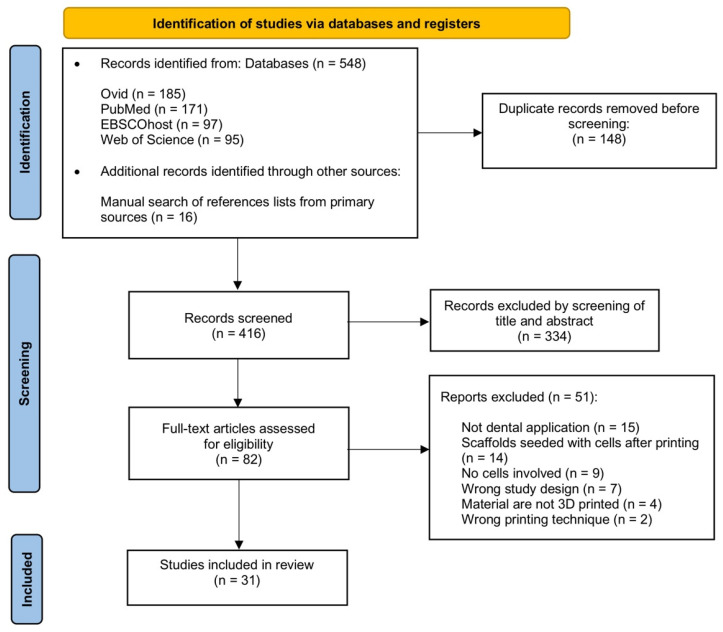

This revised search strategy generated 548 records from four databases: Ovid (n = 185), PubMed (n = 171), EBSCOhost (n = 97) and Web of Science (n = 95) through May 2022. In addition to electronic databases, a manual search of reference lists was carried out through primary sources and additional eligible studies were added (n = 16). Out of these, a total of 148 duplicates were excluded and 334 records were assessed based on their titles and abstracts. This was performed by using the online literature review application, Rayyan software (http://rayyan.qcri.org (accessed on 9 September 2022)) [40]. Moreover, full texts of the 82 articles were retrieved for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Out of those, 51 were further excluded because the articles were not for dental application (n = 15), scaffolds seeded with cells after printing (n = 14), no cells involved (n = 9), wrong study design (n = 7), materials are not 3D printed (n = 4) and wrong printing technique (n = 2). Finally, there were 31 articles included in this review, as recorded in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting the results of the search strategy.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

A third of the included articles were conducted in the USA (n = 10) [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. It was followed by Korea (n = 5) [51,52,53,54,55], France (n = 4) [56,57,58,59], Germany (n = 3) [60,61,62], China (n = 3) [63,64,65], Taiwan (n = 2) [66,67], Canada (n = 1) [68], Australia (n = 1) [69], Sweden (n = 1) [70] and Japan (n = 1) [71]. The frequency of publications showed a steady rise from 2015 to the present time, thereby reflecting a growing interest in the 3D bioprinting technology in the dental field. The main characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies based on cell-laden bioinks.

| Author | Cell-Laden Bioink | Other Biomaterial/ Growth Factor |

Cell Types | Bioprinting Strategy | Study Design |

Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2021 [53] | Collagen | FGF-2 | hPDLSCs | Extrusion | In vitro and in vivo | PDL regeneration |

| Wang et al., 2021 [66] | Collagen | SrCS | Human gingiva fibroblasts | Extrusion | In vitro and in vivo | Periodontal regeneration |

| Kérourédan et al., 2018 [57] | Collagen type 1 | - | SCAPs | LAB | In vitro and in vivo | Bone regeneration |

| Kérourédan et al., 2019 [58] | Collagen type 1 | VEGF | SCAPs and HUVECs | LAB | In vivo | Bone regeneration |

| Duarte Campos et al., 2020 [60] | Collagen type 1 + agarose | - | DPSCs and HUVECs | Inkjet | In vitro and ex vivo | Dental pulp regeneration |

| Keriquel et al., 2017 [56] | Collagen type 1 + nHAp | - | Mouse bone marrow stromal precursor D1 cell line | LAB | In vitro and in vivo | Bone regeneration |

| Moncal et al., 2021 [49] | Collagen + chitosan + β-glycerophosphate + nHAp | rhBMP-2 | Rat BMSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Moncal et al., 2022 [50] | Collagen + chitosan + β-glycerophosphate + nHAp | PDGF and BMP-2 | Rat BMSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Touya et al., 2022 [59] | Collagen type 1 + TCP (BioRoot RCS®, Septodont, Saint-Maur-des- Fossés, France) | - | SCAPs | LAB | In vitro and in vivo | Bone regeneration |

| Kim et al., 2022 [55] | Collagen type 1 or dECMs + β-TCP | - | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro and in vivo | Dental tissue regeneration |

| Kang et al., 2016 [41] | Gelatin + fibrinogen + HA + glycerol | PCL/TCP | hAFSCs | Extrusion | In vitro and in vivo | Alveolar bone/bone regeneration |

| Han et al., 2019 [51] | Gelatin + fibrinogen + HA + glycerol | - | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dentin/dental pulp regeneration |

| Han et al., 2021 [52] | Demineralized dentin matrix particles + fibrinogen + gelatin | - | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dental tissue regeneration |

| Kort-Mascort et al., 2021 [68] | Alginate + gelatin + dECMs | - | Human SCC (Cell lines: UM-SCC-12 and UM-SCC-38) | Extrusion | In vitro | Head and neck cancer in vitro model |

| Tian et al., 2021 [65] | Sodium alginate + gelatin + nHAp | - | hPDLSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Park et al., 2020 [47] | Gelatin + GelMA + HA + glycerol | BMP-mimetic peptide | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dental tissue regeneration |

| Amler et al., 2021 [62] | GelMA | - | Bone-derived MPC/Bone marrow MPC/Periosteal MPC | Stereolithography | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Raveendran et al., 2019 [69] | GelMA | - | hPDLSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Periodontal regeneration |

| Kuss et al., 2017 [42] | MeHA + GelMA + HA | PCL/HAp | Porcine stromal vascular fraction from adipose tissue | Extrusion | In vitro | Alveolar bone/bone regeneration |

| Ma et al., 2015 [63] | GelMA + PEGDA | - | hPDLSCs | Inkjet | In vitro | Periodontal regeneration |

| Ma et al., 2017 [64] | GelMA + PEGDA | - | Rat PDLSCs | Inkjet | In vitro and in vivo | Alveolar bone regeneration |

| Amler et al., 2021 [61] | GelMA + PEGDA3400 | - | JHOBs and HUVECs | Stereolithography | In vitro | Alveolar bone in vitro model |

| Lin et al., 2021 [67] | Calsium silicate + GelMA | - | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dentin regeneration |

| Chimene et al., 2020 [46] | GelMA + kCA + nSi (NICE bioink) |

- | Human primary bone marrow-derived MSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Alveolar bone regeneration |

| Athirasala et al., 2018 [43] | Alginate + dentin matrix | - | SCAPs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dentin/dental pulp regeneration |

| Walladbegi et al., 2020 [70] | Nanofibrillated cellulose + alginate (CELLINK AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) | β-TCP | hADSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Dubey et al., 2020 [48] | ECM + AMP | - | DPSCs | Extrusion | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Dutta et al., 2021 [54] | Poloxamer-407 | - | SCAPs | Extrusion | In vitro | Dental tissue regeneration |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [44] | - | - | Mice bone marrow stromal cells | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [45] | - | - | Mice bone marrow stromal cells | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) | In vitro | Bone regeneration |

| Ono et al., 2021 [71] | - | - | Human PDL cell line 1-17 | Scaffold-free (Needle array) | In vitro | PDL regeneration |

LAB, laser-assisted bioprinting; GelMA, gelatin methacryloyl; PEGDA, poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate; HA, hyaluronic acid; PCL, poly (ε-caprolactone); TCP, tricalcium phosphate; MeHA, methacrylated hyaluronic acid; kCA, kappa-carrageenan; HAp, hydroxyapatite; nHAp, nano-hydroxyapatite; AMP, amorphous magnesium phosphates; nSi, nanosilicates; Poloxamer-407, synthetic copolymer of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(propylene glycol); ECM, extracellular matrix; dECM, decellularized extracellular matrix; SrCS, strontium-doped calcium silicate; hPDLSCs, human periodontal ligament stem cells; hAFSCs, human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells; SCAPs, human stem cells from apical papilla; DPSCs, human dental pulp stem cells; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; hADSCs, human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells; JHOBs, jawbone-derived human osteoblasts; MPC, human mesenchymal progenitor cells; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; rhBMP, recombinant bone morphogenetic protein; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor

3.3. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting Strategy for Dental Application

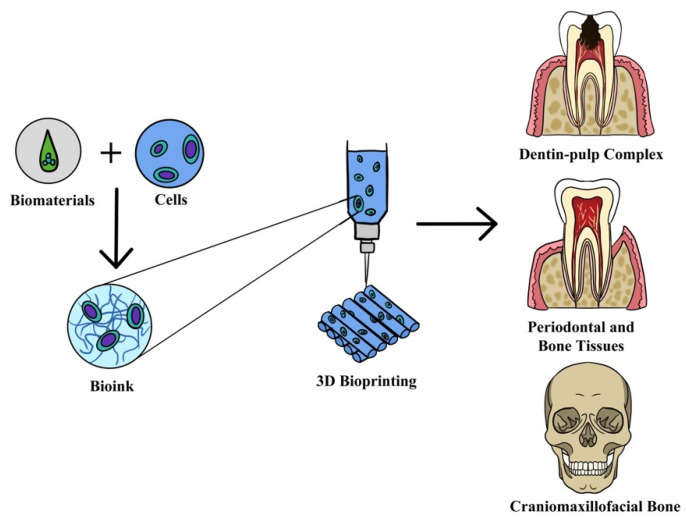

Nearly two-thirds of the research reported in this review used extrusion-based 3D bioprinting technique to fabricate scaffolds. This technique was used in eight studies for bone regeneration application [41,42,46,48,49,50,65,70], four studies used for general dental tissue regeneration [47,52,54,55], another three for periodontal ligament [53,66,69] and followed by dentin and dental pulp regeneration [43,51,67]. Apart from regeneration application, extrusion-based technique has also been used to explore the usage of scaffolds for head and neck cancer in vitro models [68]. For laser-assisted bioprinting, all the studies utilized this technology for bone regeneration [56,57,58,59]. However, for inkjet-based technique, there was various usage for regeneration of periodontal ligament [63], dental pulp [60] and bone [64]. Meanwhile, the other technique, stereolithography, has been used for bone regeneration [62] and alveolar bone in vitro modeling [61]. Another 3D bioprinting technique, which is a scaffold-free method, 3D tissue spheroids (cell aggregates) bioinks were developed by skewering individual cellular spheroids into a predetermined design onto a needle-array platform without any supporting hydrogel or matrix. This technique has been employed for periodontal ligament [71] and bone regeneration [44,45]. Overall, half of the studies used 3D bioprinting for alveolar bone/bone regeneration for dental tissue engineering application. Figure 5 shows 3D bioprinting in dental applications. The other information, such as the type of bioprinters and 3D bioprinting, is presented in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional bioprinting strategy for dental application such as regeneration of dentin–pulp complex, periodontal, alveolar bone tissues and craniomaxillofacial bone.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 3D bioprinting techniques.

| Author | Cell-Laden Bioink |

Type of Polymer | 3D Bioprinter | 3D Bioprinting Technique | Nozzle Size | Printing Speed | Printing Pressure | Crosslinking Method | Study Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2021 [53] | Collagen | Natural | 3DX Printer, T and R Biofab Co., Ltd., Siheung, Korea | Extrusion | 400 μm ~22G |

- | - | Thermal | Connective tissues interface between 3D-printed implants and calvaria bone has periodontal ligament characteristics; however, FGF-2 did not play a role in periodontal regeneration |

| Wang et al., 2021 [66] | Collagen | Natural | BioScaffolder 3.1, GeSiM, Großerkmannsdorf, Germany |

Extrusion | 400 μm ~22G | 1.5–2 mm/s | 10–20 kPa | Physical | Novel bilayer 3D printed SrCS with collagen bioink upregulate angiogenic- and osteogenic-related proteins and factors, and enhanced bone regeneration in vivo |

| Kérourédan et al., 2018 [57] | Collagen type 1 | Natural | LAB workstation (U1026, Inserm, Bordeaux, France) | LAB | - | - | - | - | Potential use of magnetic resonance imaging and bioprinted micron superparamagnetic iron oxide-labeled cells to track cell patterns in vitro and calvarium defect model in mouse |

| Kérourédan et al., 2019 [58] | Collagen type 1 | Natural | LAB workstation (U1026, Inserm, Bordeaux, France) | LAB | - | - | - | - | In situ printing of HUVECs enhance vascularization and bone regeneration in calvarial defects |

| Duarte Campos et al., 2020 [60] | Collagen type 1 + agarose | Natural | Hand-held bioprinter (DropGun, BlackDrop Biodrucker GmbH, Aachen, Germany) | Inkjet | 300 μm ~23G |

- | 25–250 kPa | Thermal | Handheld in situ bioprinting of cell-loaded collagen-based bioinks demonstrated successful vasculogenesis |

| Keriquel et al., 2017 [56] | Collagen type 1 + nHAp | Natural | LAB workstation (U1026, Inserm, Bordeaux, France) | LAB | - | 250 μm/s | - | - | 3D printed disk form of nHAp-collagen and D1 cells (bone marrow stromal precursor cells) showed the formation of mature bone in a calvarial defect model |

| Moncal et al., 2021 [49] | Collagen + chitosan + β-glycerophosphate + nHAp | Natural | In-house developed MultiArm Bioprinter, Iowa City, IA, USA | Extrusion | 22G~410 μm | 400 mm/min | 80–140 kPa | Thermal and physical | Hybrid intra-operative bioprinting induced bone regeneration with nearly 80% regenerated critical size calvarial bone defect |

| Moncal et al., 2022 [50] | Collagen + chitosan + β-glycerophosphate + nHAp | Natural | In-house developed MultiArm Bioprinter, Iowa City, IA, USA | Extrusion | 22G~410 μm | 400 mm/min | 80–140 kPa | Thermal and physical | Bioprinted bone constructs with the controlled co-delivery release of growth factors resulted in bone regeneration in critical-sized calvarial defects |

| Touya et al., 2022 [59] | Collagen type 1 + TCP (BioRoot RCS®, Septodont, France) | Natural | LAB workstation (U1026, Inserm, Bordeaux, France) | LAB | - | - | - | - | TCP-based ink demonstrated positive significance upon cell motility, and early osteogenic differentiation in vitro. However, the bioink was not successful in regenerating critical size cranial bone defects in vivo |

| Kim et al., 2022 [55] | Collagen type 1 or dECMs + β-TCP | Natural | DTR3–2210 T-SG; DASA Robot, Bucheon, Korea | Extrusion | 250 μm ~25G |

10 mm/s | 17–22 kPa | Genipin | The hDPSC-laden bone-derived dECM biocomposite enhanced both osteogenic and odontogenic differentiation in vitro and in vivo |

| Kang et al., 2016 [41] | Gelatin + fibrinogen + HA + glycerol | Natural | Integrated tissue–organ printing system | Extrusion | 300 μm ~23 G |

- | 50–80 kPa | Thrombin | 3D tissue construct provides a favorable microenvironment for osteogenic differentiation of hAFSCs in vitro and showed the formation of mature, vascularized bone tissues in the calvarial bone defect model |

| Han et al., 2019 [51] | Gelatin + fibrinogen + HA + glycerol | Natural | Integrated tissue–organ printing system | Extrusion | 250 μm ~25G | 50–90 mm/min | - | Thrombin | Fibrin-based cell-laden bioink demonstrated spatial regulation of DPSC differentiation for the construction of 3D dentin–pulp complexes |

| Han et al., 2021 [52] | Demineralized dentin matrix particles + fibrinogen + gelatin | Natural | Homemade 3D bioprinter, Ulsan, Korea | Extrusion | 300 μm ~23G |

50 mm/min | 200 kPa | Thrombin | DDMp bioink can be used to fabricate 3D cellular dental constructs and showed significantly improvement in odontogenic differentiation of DPSCs |

| Kort-Mascort et al., 2021 [68] | Alginate + gelatin + dECMs | Natural | BioScaffolder 3.1, GeSiM, Großerkmannsdorf, Germany |

Extrusion | 22G ~400 μm |

10 ± 2 mm/s | 45 ± 10 kPa | Calcium chloride | Cell-laden dECM-based bioink demonstrated tumor spheroids development by squamous cell carcinoma cells with high cell viability and proliferation |

| Tian et al., 2021 [65] | Sodium alginate + gelatin + nHAp | Natural | 3D Bioplotter (EnvisionTEC GmbH, Gladbeck, Germany) |

Extrusion | 400 μm ~22G |

6 mm/s | 200 kPa | Calcium chloride | The hPDLSCs-laden bioink demonstrated good biocompatibility, stimulation of cell survival, proliferation and osteoblast |

| Park et al., 2020 [47] | Gelatin + GelMA + HA + glycerol | Natural | Integrated tissue–organ printing system | Extrusion | 330 μm ~23G | 150 mm/min | 130–160 kPa | Photopolymerization | Novel BMP-GelMA bioink showed high viability, proliferation and odontogenic differentiation of hDPSC |

| Amler et al., 2021 [62] | GelMA | Natural | Cellbricks GmbH, Berlin, Germany | Stereolithography | - | - | - | Photopolymerization | Periosteum-derived cells showed higher mineralization of print matrix and superior osteogenic potential for 3D bone constructs |

| Raveendran et al., 2019 [69] | GelMA | Natural | BioScaffolder 3.1, GeSiM, Großerkmannsdorf, Germany |

Extrusion | ~220 μm 25G |

10–12 mm/s | 135 kPa | Photopolymerization | The best 3D bioprinting outcome of the periodontal ligament was obtained using 12.5% GelMA concentration with 0.05% LAP extruded through a 25G needle at 135kPa and crosslinking with UV-irradiation |

| Kuss et al., 2017 [42] | MeHA + GelMA + HA | Natural | 3D Bioplotter (EnvisionTEC GmbH, Gladbeck, Germany) |

Extrusion | ~400 μm 22G |

1.8–2.2 mm/s | - | Photopolymerization | Short-term hypoxia (up to 7 days) promoted microvessel formation of SVFC-laden constructs without significantly affecting the cell viability compared to long-term hypoxia (more than 14 days) |

| Ma et al., 2015 [63] | GelMA + PEGDA | Natural and synthetic | Customer-designed pressure-assisted valve-based bioprinting system | Inkjet | 150 μm ~30G | - | 40–60 kPa | Photopolymerization | Volume ratios of GelMA to PEG bioink have an impact on cell viability and spreading of hPDLSCs. The increasing ratio of PEG leads to a decrease in hPDLSCs viability and spreading area |

| Ma et al., 2017 [64] | GelMA + PEGDA | Natural and synthetic | Customer-designed pressure-assisted valve-based bioprinting system | Inkjet | 150 μm ~30G | - | 50 kPa | Photopolymerization | An increase in the volume ratio of 3D GelMA-PEGDA in vitro resulted in an increase in cell proliferation, spreading and osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs. New bone formation was observed in the alveolar defect treated with 3D bioprinted PDLSC hydrogel in a rat model |

| Amler et al., 2021 [61] | GelMA + PEGDA3400 | Natural and synthetic | Cellbricks GmbH, Berlin, Germany | Stereolithography | - | - | - | Photopolymerization | 3D bioprinted constructs containing primary JHOBs with vasculature-like channel structures comprising endothelial cells demonstrated the survival of both cells and mineralization of the bone matrix |

| Lin et al., 2021 [67] | Calsium silicate + GelMA | Natural | BioX, CELLINK, Gothenburg, Sweden |

Extrusion | 30G~150 μm | 20 mm/s | 180 kPa | Photopolymerization | Calcium silicate/GelMA scaffolds enhanced mechanical properties and odontogenesis of hDPSCs |

| Chimene et al., 2020 [46] | GelMA + kCA + nSi (NICE bioink) |

Natural | Modified ANET A8 3D printer, Shenzhen, China | Extrusion | 400 μm ~22G |

15 mm/s | - | Photopolymerization | 3D NICE cell-laden bioink demonstrated the ability to form osteo-related mineralized ECM without the growth factor |

| Athirasala et al., 2018 [43] | Alginate + dentin matrix | Natural | Hyrel 3D, Norcross, GA, USA | Extrusion | Coaxial: 26–19G | - | - | Calcium chloride | Cell-laden alginate and dentin matrix enhances odontogenic differentiation of SCAPs |

| Walladbegi et al., 2020 [70] | Nanofibrillated cellulose + alginate (CELLINK AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) | Natural | Inkredible, CELLINK AB, Gothenburg, Sweden |

Extrusion | Coaxial: 22–16G |

- | 75 kPa and 85 kPa | Calcium chloride | A coaxial needle enables the printing of a stable scaffold with viable hADSCs |

| Dubey et al., 2020 [48] | ECM + AMP | Natural | 3DDiscovery, regenHU, Villaz-St-Pierre, Switzerland |

Extrusion | - | 15–20 mm/s | 30–50 kPa | Physical | ECM/AMP-bioprinted constructs demonstrated osteogenic differentiation of DPSCs without the need for chemical inducers |

| Dutta et al., 2021 [54] | Poloxamer-407 | Synthetic | CELLINK BIO-X 3D printer, Gothenburg, Sweden |

Extrusion | 27G | 5 mm/s | 35 kPa | Photopolymerization | 3D bioprinted poloxamer hydrogels with low voltage–frequency electromagnetic fields stimulation (5V-1 Hz, 0.62 mT) enhance the SCAPs viability and osteogenic potential |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [44] | - | - | Regenova Bio 3D Printer, Cyfuse K.K, Tokyo, Japan | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) |

- | - | - | - | Centrifugation cell method generated tighter BMSC spheroid formation with the optimal technique of 40k cells aggregate under 150-300G |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [45] | - | - | Regenova Bio 3D Printer, Cyfuse K.K, Tokyo, Japan | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) |

- | - | - | - | Optimization of scaffold-free bioprinting resulted in a reduction in print times, the use of bioprinting nozzles and fabrication of more robust constructs |

| Ono et al., 2021 [71] | - | - | Regenova Bio 3D Printer, Cyfuse K.K, Tokyo, Japan | Scaffold-free (Needle array) | 240 μm ~26G |

- | - | - | 3D bioprinted tubular structures and hydroxyapatite core materials exhibited high cell viability, collagen fibers and strongly expressed factors associated with periodontal ligament tissues |

3D, three-dimensional; LAB, laser-assisted bioprinting; USA, United States of America; GelMA, gelatin methacryloyl; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); PEGDA, poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate; HA, hyaluronic acid; TCP, tricalcium phosphate; MeHA, methacrylated hyaluronic acid; kCA, kappa-carrageenan; nHAp, nano-hydroxyapatite; AMP, amorphous magnesium phosphates; nSi, nanosilicates; Poloxamer-407, synthetic copolymer of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(propylene glycol); ECM, extracellular matrix; dECM, decellularized extracellular matrix; LAP, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate; DDMp, demineralized dentin matrix particles; SrCS, strontium-doped calcium silicate; SVFC, stromal vascular fraction derived cells; hPDLSCs, human periodontal ligament stem cells; hAFSCs, human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells; SCAPs, human stem cells from apical papilla; DPSCs, human dental pulp stem cells; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; hADSCs, human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells; JHOBs, jawbone-derived human osteoblasts; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; UV, ultraviolet.

3.4. Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting

In this review, the majority of cell-laden bioinks consist of combinations of two to four polymers and/or biomaterials for 3D bioprinting applications. The commonly used materials for the fabrication of bioinks were natural polymers (collagen, gelatin, fibrin, alginate, hyaluronic acid (HA), chitosan, agarose and glycerol). Naturally derived polymers with chemical modifications such as gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) and methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) also have been used as bioinks. Only one study used synthetic polymer alone, Poloxamer-407, a synthetic copolymer of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(propylene glycol) [54]. Meanwhile, three studies used hybrid materials that are the combination of GelMA and poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDA) [61,63,64].

Decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM)-based, also termed tissue-specific bioink, was used by two studies [52,55]. In addition, some studies added bioceramics materials such as nano-hydroxyapatite [49,50,56,65], calcium phosphate [55] and calcium silicate [59,67] with composite bioinks. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) was the most commonly used growth factor reported in this review [47,49]. Other growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [58] and fibroblast growth factors (FGF) [53] have also been investigated within 3D bioprinted constructs. Meanwhile, one study utilized gene-based growth factors using a nonviral gene delivery method, which was the combination of platelet-derived growth factor-B encoded plasmid DNA (pPDGF-B) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 encoded plasmid DNA (pBMP2) [50].

In 3D bioprinting, the crosslinking approach is an important aspect to achieve the biomechanical stability of 3D constructs. Herein, the collagen-based bioinks were crosslinked either using temperature [53,60] or physical [66], or a combination of both [49,50], or genipin [55]. Eight studies used GelMA, the modified naturally derived polymer, which was crosslinked by photopolymerization [46,47,54,61,62,63,64,67,69]. Synthetic polymer, Poloxamer-407 also uses UV light for photocrosslinking [54]. Apart from that, alginate bioink used calcium chloride as its crosslinker [43,65,68,70]. Fibrin-based bioink can be made from fibrinogen by enzymatic reaction of thrombin [41,51,52].

3.5. Cells for 3D Bioprinting

Types of cells for 3D bioprinting reported in this review were mesenchymal stem cells and cell lines. Stems cells isolated from the human oral cavity have been used, such as periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) [53,63,65,69], dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) [47,48,51,52,55,60,67] and stem cells from apical papilla (SCAPs) [43,54,57,58,59]. Meanwhile, one study used gingival fibroblast in the cell-laden bioink [66]. In this review, human dental stem cells were isolated from third molar teeth of young healthy patients with an age range of 18–28 years old. Only one study isolated nonhuman periodontal ligament stem cells from rats [64].

As reported in this review, other main sources of cells used were nondental-origin stem cells from bone marrow [44,45,46,49,50,62] and adipose tissue [42,70]. Apart from this, some studies used extracted cells derived from bone [61,62], periosteum [62], amniotic fluid [41] and umbilical vein [58,60,61]. These MSCs sources were from humans and various animals such as rats, mice and porcine. Furthermore, two studies implemented a co-culture approach using SCAPs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [58], DSPCs and HUVECS [60] in their research.

Other types of cells that have been used were human squamous cell carcinoma lines from cancer larynx (UM-SCC-12) and tonsillar pillar (UM-SCC-38) [68], multipotent clonal human PDL cell line (line 1–17) [71] and mouse bone marrow stromal precursor D1 cell line [56]. Herein, 3D bioprinting produces high cell viability after printing in the range of 70% to greater than 95%. The details of the type of cells used in 3D bioprinting are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of cell types in 3D bioprinting application.

| Author | Cell Type | Cell Densities |

Max Cell Viability (%) | 3D Bioprinting Technique |

Targeted Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han et al., 2019 [51] | DPSCs | 3 × 106 cells/mL | >90 | Extrusion | Dentin/dental pulp |

| Park et al., 2020 [47] | DPSCs | - | >90 | Extrusion | Dental tissue |

| Dubey et al., 2020 [48] | DPSCs | 1 × 106 cells/mL | >90 | Extrusion | Bone |

| Han et al., 2021 [52] | DPSCs | 3 × 106 cells/mL | >95 | Extrusion | Dental tissue |

| Lin et al., 2021 [67] | DPSCs | 5 × 106 cells/mL | - | Extrusion | Dentin/pulp |

| Kim et al., 2022 [55] | DPSCs | 1 × 107 cells/mL | >95 | Extrusion | Dental tissue |

| Duarte Campos et al., 2020 [60] | DPSCs and HUVECs |

3 × 106 cells/mL (both type of cells) | - | Inkjet | Dental pulp |

| Ma et al. 2015 [63] | hPDLSCs | 1 × 106 cells/mL | 82.4 ± 4.7 | Inkjet | Periodontal ligament |

| Raveendran et al., 2019 [69] | hPDLSCs | 2.0 × 106 cells/mL | >70 | Extrusion | Periodontal ligament |

| Lee et al., 2021 [53] | hPDLSCs | 1 × 107 cells/mL | - | Extrusion | Periodontal ligament |

| Tian et al., 2021 [65] | hPDLSCs | - | - | Extrusion | Bone |

| Ma et al., 2017 [64] | Rat PDLSCs | 1 × 106 cells/mL | ~90 | Inkjet | Bone |

| Athirasala et al., 2018 [43] | SCAPs | 0.8 × 106 cells/mL | >90% | Extrusion | Dentin/dental pulp |

| Kérourédan et al., 2018 [57] | SCAPs | 7 × 107 cells/mL | LAB | Bone | |

| Dutta et al., 2021 [54] | SCAPs | 2.5 × 104 cells/mL | - | Extrusion | Dental tissue |

| Touya et al., 2022 [59] | SCAPs | 2 × 103 cells/mL | - | LAB | Bone |

| Kérourédan et al., 2019 [58] | SCAPs and HUVECs |

7 × 107 cells/mL | - | LAB | Bone |

| Wang et al., 2021 [66] | Human gingiva fibroblasts | 5 × 105 cells/mL | - | Extrusion | Periodontal ligament/Bone |

| Ono et al., 2021 [71] | Human PDL cell line 1–17 | 2.5 × 104 cells/mL | - | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) | Periodontal ligament |

| Kort-Mascort et al., 2021 [68] | Human SCC (Cell lines: UM-SCC-12 and UM-SCC-38) | 1 × 106 cells/mL | >95 | Extrusion | Dental tissue |

| Chimene et al., 2020 [46] | Human primary bone marrow-derived MSCs | - | - | Extrusion | Bone |

| Amler et al., 2021 [62] | Bone-derived MPC/Bone marrow MPC/Periosteal MPC | 20 × 106 cells/mL | - | Stereolithography | Bone |

| Moncal et al., 2021 [49] | Rat BMSCs | 5 × 106 cells/mL | >95 | Extrusion | Bone |

| Moncal et al., 2022 [50] | Rat BMSCs | 8 × 105 cells/mL | >95 | Extrusion | Bone |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [44] | Mice bone marrow stromal cells | - | - | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) | Bone |

| Aguilar et al., 2019 [45] | Mice bone marrow stromal cells | - | - | Scaffold-free (Kenzan method) | Bone |

| Keriquel et al., 2017 [56] | Mouse bone marrow stromal precursor D1 cell line | 120 × 106 cells/mL | - | LAB | Bone |

| Amler et al., 2021 [61] | JHOBs and HUVECs |

20 × 106 cells/mL | - | Stereolithography | Bone |

| Walladbegi et al., 2020 [70] | hADSCs | 4 × 106 cells/mL | ~80 | Extrusion | Bone |

| Kuss et al., 2017 [42] | Porcine stromal vascular fraction from adipose tissue | 4 × 106 cells/mL | - | Extrusion | Bone |

| Kang et al., 2016 [41] | hAFSCs | 5 × 106 cells/mL | 91 ± 2 | Extrusion | Bone |

LAB, laser-assisted bioprinting; hPDLSCs, human periodontal ligament stem cells; hAFSCs, human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells; SCAPs, human stem cells from apical papilla; DPSCs, human dental pulp stem cells; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; hADSCs, human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells; JHOBs, jawbone-derived human osteoblasts; MPC, human mesenchymal progenitor cells; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

3.6. In Vivo Application in Dental Tissue Engineering

Out of 31 studies, a total of 11 studies reported in vivo applications on animal models. However, only nine studies used cell-based scaffolds and the other three were cell-free bioprinted constructs implanted in vivo using the extrusion-based technique. Therefore, in this review, only nine studies were reported for in vivo evaluation, which involve implantation of the 3D bioprinted constructs into calvarium [41,53,56,57,58,59,66], alveolar bone [64] and subcutaneous area [55]. The calvarial bone defects were surgically created without penetration into the dura with a diameter ranging from 3.3 to 8 mm. In addition, the alveolar defect was created with a dimension of 4 mm length × 3 mm width × 2 mm height. One study reported implantation of bioprinted constructs (8 × 8 × 4 mm3) on dorsal subcutaneous pockets. Meanwhile, for animal models in this review, only one article used rabbits as osteoporotic models in their study [66], whereas the others used immunodeficient rats or mice (either athymic, balb/c, NOG or NSG mice) as their animal models [41,53,55,57,58,59,64].

Moreover, four studies reported performing in situ or intra-operative bioprinting of the 3D constructs during surgical intervention on the cranial bony defects using laser-assisted bioprinting, as shown in Figure 6 [56,57,58,59]. After implantation of the 3D printed constructs, the animals were euthanized at time points ranging from 3 to 20 weeks to harvest implanted specimens. The characteristics of the animal models are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Intra-operative bioprinting (IOB) using laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) approach in vivo application. LAB setup comprises a pulsed laser beam, a ribbon (transparent glass slide coated with a laser-absorbing layer of metal) and a receiving substrate. Reproduced with permission [56]. Copyright 2017 SpringerNature publishing under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 21 August 2022)).

Table 4.

Summary of animal model characteristics.

| Author | Animal Model | Sex | Age | Weight | Defect Area | Defect Size | In Situ Printing | Time of Sacrifice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keriquel et al., 2017 [56] | Balb/c mice | Female | 12 weeks | 19–20 g | Calvarium | 3.3 mm diameter | Yes | 8 weeks |

| Kérourédan et al., 2018 [57] | NOG mice | Female | 10 weeks | 25–26 g | Calvarium | 3.3 mm diameter | Yes | - |

| Kérourédan et al., 2019 [58] | NSG mice | Female | 10 weeks | 25–26 g | Calvarium | 3.3 mm diameter | Yes | 4 or 8 weeks |

| Touya et al., 2022 [59] | NSG mice | Female | 8 weeks | - | Calvarium | 3.3 mm diameter | Yes | 4 weeks or 8 weeks |

| Kang et al., 2016 [41] | Sprague Dawley rats | - | - | 250–300 g | Calvarium | 8 mm diameter, 1.2 mm depth | No | 20 weeks |

| Lee et al., 2021 [53] | Athymic rats | Male | 9 weeks | - | Calvarium | 8 mm diameter, 1.5 mm depth | No | 6 weeks |

| Wang et al., 2021 [66] | New Zealand white rabbit | Female | - | 2 kg | Calvarium | 7 mm diameter, 8 mm depth | No | 12 weeks |

| Ma et al., 2017 [64] | Sprague Dawley rats | - | 33 months | 230–250 g | Alveolar bone | 4 mm length × 3 mm width × 2 mm height | No | 3 and 6 weeks |

| Kim et al., 2022 [55] | Athymic nude mice | - | - | - | Dorsal subcutaneous | - | No | 8 weeks |

4. Discussion

Three-dimensional bioprinting has become an advanced tissue engineering approach to create dental tissue constructs to address the need for regenerative dentistry. The studies included in this review showed a wide range of heterogeneity in terms of different types of novel bioinks, 3D bioprinting techniques, type of cells used and applications of 3D bioprinting in dentistry.

In addition, recent 3D bioprinting development provides multiple approaches for the biofabrication of tissue constructs within scaffolds or scaffold-free environments. This approach could produce 3D structures with spatial organization of cells that facilitates the control of the shape of regenerated tissues. However, 3D bioprinting still faces significant challenges as compared to the nonbiological printing approach in terms of more complex architectural fabrication and the stability of cell behavior. In this review, the extrusion-based technique is the most common 3D bioprinting method for dental application. This technique is widely used because it is cost-effective and able to replicate complex tissue structures using a wide variety of biomaterials and cell types [19,20,72]. Moreover, the extrusion-based techniques can produce cell-laden bioinks in the form of continuous strands or fibers, which enable fabricating of large-scale 3D scaffold constructs [15,73]. Furthermore, printing parameters such as printing speed, pressure, resolution, temperature, nozzle inner diameter, scaffold design and viscosity of the bioink are important factors in determining the uniformity of continuous strands deposition of the bioprinted scaffolds [74].

Bioink is also an important component of 3D bioprinting. The ideal bioink formulation should satisfy certain biomaterial and biological requirements. Biomaterial properties include printing compatibility, mechanical properties, biodegradation, modifiable functional groups on the surface and post-printing maturation, whereas the biological requirements mainly include biocompatibility, cytocompatibility, and bioactivity of cells after printing to support and maintain cellular viability and function [36]. Therefore, the treatment outcome of the tissue regeneration depends on the bioinks used. Nonetheless, at present there is a lack of ideal 3D printable bioinks focused on dental tissue regeneration.

Natural polymers are the most common type of polymer used as bioink because they have a similar native composition as the ECM, biocompatibility and biodegradation properties, together with established interactions between natural polymers and cells [75]. Collagen type I is a hydrogel of choice for tissue engineering, which agrees with the research reported in this review. In addition, it is the most abundant component of the native ECM and provides an encouraging environment for cell adhesion and proliferation [76]. Crosslinking collagen matrices play an important role in the strength and stability of the structure. In comparison to noncrosslinked collagen, there is an increase in tensile strength and viscoelastic properties when using a crosslinker [77,78]. The crosslinked collagen constructs demonstrated different stiffness strengths based on types of oral tissue engineering. However, for dental pulp tissue application, the combination of collagen and agarose showed a storage modulus of approximately 0.03–0.3 kPa [60]. A study by Moncal et al. showed that in calvarial bone repair, the storage modulus of the collagen-based bioink was 8.2 ± 1.4 kPa [49]. In another study for dental tissue engineering application, collagen/β-TCP 20 wt% showed 27.9 ± 2.2 kPa modulus, which was higher than collagen alone because of the added bioceramics in the bioink [55]. The balance between mechanical strength and cell viability of the 3D constructs is crucial to maintaining cell structure and promoting cell growth. The natural polymer can be combined either with synthetic or another type of natural polymer to produce a more stable construct with enhanced function and properties. Another hydrogel-based bioink that shows potential in 3D bioprinting is GelMA because of its superior biocompatibility and photocrosslinking properties [79]. Herein, various GelMA-based bioinks have been developed to fabricate tissue structures for application in periodontal ligament [63,69], dentin [67], bone [42,46,62,64] and dental tissue regeneration [47], along with in vitro modeling of alveolar bone [61].

Synthetic polymers can be manufactured in large quantities and have longer shelf life as compared to natural polymers [80]. The photocrosslinking ability and controllability of mechanical properties, degradation rate, pH and temperature are among the advantages of using the polymers. However, most synthetic polymers lack the ability to promote cellular adhesion and recognition, and have limited biodegradability and biocompatibility, which restrict their usage in clinical applications [81]. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is one of the most popular synthetic polymers in tissue engineering [82]. PEG-based bioink can be modified using diacrylate (DA) or methcrylate (MA) groups to improve mechanical strength. In addition, the combination of PEGDA/GelMA has been used for periodontal ligament and bone regeneration application [63,64] and for in vitro alveolar bone models [61]. Moreover, a combination of natural and synthetic polymers can be a promising bioink material for fabricating biomimetic tissues because of their combined properties [83]. Another bioink, dECM, has been frequently used as a bioink in 3D bioprinting because of its good inductive property that can promote cell proliferation and differentiation together with the interaction between cells to cells and cells to ECM [84,85]. Herein, the various types of novel bioinks demonstrated high printability and cell viability, which have the potential in dental tissue regeneration applications. However, a few studies showed that novel bioinks need formulation adjustment for oral tissue engineering: (i) collagen-based with TCP (BioRoot RCS®, Septodont, France) bioink did not demonstrate regenerative potential in a calvaria critical bone defect model [59], (ii) combination of collagen-based with β-TCP reduced the capability of osteogenic differentiation, mineralization and vascularization compared to dECMs with β-TCP [55] and (iii) addition of FGF-2 to the collagen bioink did not play a role in periodontal ligament regeneration [53].

The use of growth factors in 3D bioprinting is not prevalent in dental applications because of the additional complexities that may arise. In general, the strategies in utilizing the growth factor in tissue engineering are still unclear mainly because of the uncertainties of the delivered dosage in vivo by the constructs [86], the effects of multiple uses of growth factors [87], and no standardization and arbitrariness of growth factor dosage from the broad range of concentrations available [88].

Three-dimensional bioprinting technology with the support of stem-cell-containing scaffolds has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to address the critical need for dental tissue regeneration [37]. This is because 3D bioprinting of the cell-laden hydrogel combines physical and biological properties to attain a 3D composite construct with homogenous cell distribution, proliferation and differentiation [89]. Adult stem cells are currently the most common cells used in the field of bone tissue engineering. The advantage of stem cells derived from dental tissues is that they are easily accessible and have interesting proliferation and differentiation abilities. Healthy tissues and young patients contain a large number of normal stem cells as compared to inflamed or traumatized tissues and aging patients, which can affect the potential for tissue repair [90].

In addition, dental pulp is highly vascularized; thus, it poses a major challenge in regenerating dental pulp tissues. DPSCs are a promising source for odontogenesis because of their excellent clonogenic efficiency [91] and proangiogenic capacity [92]. A study by Duarte Campos et al. has shown evidence of successful vascular tube formation using printable bioink that contains co-cultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with DPSCs [60]. These co-cultures not only can enhance angiogenesis but also stabilize the capillary-like structures [93]. Another study also showed promising results with DPSCs, demonstrating spatial regulation of odontogenic differentiation for 3D dentin–pulp complex formation [51]. Apart from DPSCs, SCAPs isolated from immature apical papilla could enhance odontogenic differentiation, which in the future could engineer dentin–pulp tissues [43].

Periodontium is a complex structure consisting of the periodontal ligament, cementum, gingiva and alveolar bone. Designing a scaffold for periodontal regeneration would require multilayer cementum–periodontal ligament–alveolar bone components to achieve both hard and soft tissue regeneration. The biomaterials should have a combination of polymers (i.e., collagen and gelatin) and inorganic components (i.e., hydroxyapatite, calcium phosphates and bioactive glass), given that they have different mechanical strengths [94]. However, only one study in this review used a bilayered scaffold, which consisted of collagen and strontium-doped calcium silicate for periodontal regeneration [66]. Meanwhile, the others used GelMA-based PDLSCs as their bioinks for periodontal ligament regeneration application [53,63,69]. Furthermore, PDLSCs can facilitate the formation of new alveolar bone and functional ligaments in damaged periodontal tissue under proper stimulation [95,96,97].

In craniomaxillofacial reconstruction, the patient-specific shape is the key factor for clinical application as there are no similar defects in terms of size and shape. Hence, achieving facial symmetry is a crucial outcome to prevent problems such as aesthetics, articulation and mastication. Thus, 3D bioprinting is favorable in fabricating specific dimensions of 3D constructs with targeted regeneration of complex tissue architectures to address the reconstructive challenges [98]. Meanwhile, in dental applications for bone regeneration, stem cells from dental origin are popular cell sources in this review. DPSCs have shown to have higher osteogenic potential than bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs), and can also produce vessel-integrated bone tissue structures which are imperative for large bone defect reconstruction [48]. The third molar is the best source for DPSCs and it can proliferate and differentiate into osteoblast and odontoblast lineages to form dentin and bone [99,100]. Other cell types that have been used are PDLSCs, which have shown multidirectional differentiation to form alveolar bone and cementum for bone tissue regeneration [101].

For the research reported in this review, bone marrow stem cells that have been used were mostly sourced from rats and mice. If human-sourced bone marrow were to be used for clinical translation for oral and craniofacial defect regeneration, it presents a few disadvantages, such as painful harvesting of bone marrow procedure and the issue of harvest yield [102]. Hence, human adipose tissue presents a desirable choice for tissue regeneration considering the simple harvesting process as compared to the traditional method. It also causes less morbidity in the patient and provides an abundant amount of adipose stem cells [103,104]. Another advantage is that the cells are capable to differentiate into osteoblastic lineage [103].

Furthermore, a stable printed scaffold with viable cells which can withstand the load-bearing force is one of the contributing factors to the predictable outcome of reconstructing oral and craniofacial defects. Therefore, in the research reported in this review, the crosslinking mechanism has been used to increase the stability of materials such as photocrosslinking of GelMA bioinks [42,46,62,64]. Another strategy is by combining bioceramic materials such as nano-hydroxyapatite, calcium phosphate and calcium silicate to gain improved mechanical properties of the constructs [105]. Given that hydroxyapatite exhibits the same function and composition as bones and teeth [106], the addition of hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate to form 3D osteogenic structures has been widely explored in this field because the materials mimic the inorganic component of bone tissue [76,106].

In addition, scaffold-free tissue engineering is another 3D bioprinting technology to fabricate tissue construction. As reported in this review, this approach has been utilized for periodontal ligament [71] and bone regeneration application [44,45]. This technique does not use exogenous scaffolds for support but relies on generating constructs from cell spheroids fusion because of the cell-to-cell contact behavior [107]. Moreover, it eliminates the degradation time factor of scaffold materials, which can affect the viability of the encapsulated cells caused by byproducts of fast degradation scaffolds, whereas the slow degradation time may hinder the matrix formation [108,109]. Hence, using the scaffold-free method, cells would secrete the extracellular matrix required to provide structure. Therefore, the cells are within a biologically optimized extracellular matrix (ECM) environment to which they are suited. The utilization of cell-secreted ECM also eliminates the need to rely on the degradation of synthetic scaffold materials [45].

Meanwhile, for in vivo utilization, the studies used immunodeficient rats or mice as their animal models because these models are excellent recipients for the engraftment of human cells [58]. Small animal models are a popular selection for in vivo studies because of their ease of handling and lower cost to manage [110]. The prominent dissimilarity to the human bone [111] and the healing after implantation in small tissue defects in small animals [9] indicates that the results should be interpreted with caution, and thus, it plays a small role in translating the findings into human clinical applications [112,113,114]. The critical-sized calvarial bone defect has been widely used to study the interaction between cells and biomaterial on bone regeneration [115]. In addition, in situ bioprinting or intra-operative bioprinting is an advanced technology that has been performed to repair the defect via the bioprinting process on a live subject during the surgical intervention [15,116]. This approach can eliminate the change in the morphology of the prefabricated 3D bioprinted constructs during in vitro construction process, transport during surgery or manipulation of the bioprinted scaffolds to conform to the defect shape [117]. Therefore, in situ bioprinting offers immediate printing of the bioink to the defect site in an anatomically accurate and personalized reconstruction for successful restoration of the tissues [118]. Moreover, it provides an interesting perspective for clinical practice considering that it could eliminate need for the in vitro fabrication phase, which may delay the implantation procedure. In this review, all in situ bioprinting was carried out on calvarial defects using the laser-assisted bioprinting technique. LAB was used to print bioinks containing SCAPs for bone regeneration application. Even though LAB produces high printing resolution and high throughput, this approach is currently not able to fabricate large-scale tissue constructs because of the relatively slow printing speed [18]. However, this technique could be suitable for in situ bioprinting for small defects and relatively flat bones [119].

Therefore, to summarize the current perspectives of advanced research in 3D bioprinting for dental application based on the included studies, some limitations need to be addressed. However, we must acknowledge this is a novel approach and very much in the early stage of development. Firstly, various novel bioinks report promising outcomes on the advancement of customized specific constructs. Nonetheless, there is a wide heterogeneity in bioink composition (type of biomaterials and cells), printing parameters and application in dental tissue engineering which presents a challenge in deciding which bioink is compatible with the best standard of care and restoring the physiological function of the teeth. Secondly, the current research is mostly in vitro studies, hence, they are still in preliminary steps and not yet possible to prove its effectiveness in vivo. In addition, the results from in vivo studies need to be interpreted with great caution considering that the surgically created defects are small. Therefore, fabrication of large 3D printed tissue constructs and implanted into large animal models such as dogs or monkeys would be an optimal study design to better investigate the outcomes of the clinically relevant size and architecture of regenerated tissues. Finally, the ideal research models developed should be able to simulate the dentoalveolar environment since the defect created on the calvarium might not give a true reflection of more complex conditions in the oral cavity. The future prospects of 3D bioprinting are highly promising, and the progress toward the potential development of 3D printed tissues for an individual patient using the patient’s cells needs to be considered for clinical translation. Nevertheless, the implantation of 3D bioprinted tissues in humans, which include living cells and biomaterials, will face regulatory challenges given that the long-term effects such as safety and efficacy in humans are still unknown. Therefore, the ethical, technical and legal issues need to be addressed and regulated by national guidelines to protect the health and well-being of patients before adopting the 3D bioprinting technology into human clinical applications.

5. Conclusions

Three-dimensional bioprinted novel bioinks based on natural and synthetic polymers, dECM, cell aggregates and spheroids have shown promising results in dental applications, particularly for periodontal ligament, dentin, dental pulp and bone regeneration. The increasing use of stem cells derived from dental origin can offer a good cell source in oral tissue engineering. In addition, 3D bioprinting brings significant potential in translating advanced tissue engineering into the clinical application by creating regenerative scaffolds tailored to patient-specific requirements. It is hoped that continuous research and advancement in 3D bioprinting, particularly in the techniques and materials used in dental applications, would reach a level of refinement and standard that can be fully integrated into the management and practice in addressing oral healthcare problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., M.R. and M.J.G.; methodology, N.M.; validation, N.M., M.R. and N.H.A.K.; formal analysis, N.M. and M.R.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, N.M., M.R., M.J.G. and N.H.A.K.; supervision, M.R., M.J.G. and N.H.A.K.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The work is part of a project supported by CREST (Collaborative Research in Engineering, Science and Technology) (T05C2-20), Malaysia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kassebaum N.J., Bernabe E., Dahiya M., Bhandari B., Murray C.J.L., Marcenes W. Global Burden of Severe Periodontitis in 1990–2010: A systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 2014;93:1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcenes W., Kassebaum N., Bernabe E., Flaxman A., Naghavi M., Lopez A.D., Murray C. Global Burden of Oral Conditions in 1990–2010: A systematic analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2013;92:592–597. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen F.-M., Zhang J., Zhang M., An Y., Chen F., Wu Z.-F. A review on endogenous regenerative technology in periodontal regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7892–7927. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nkenke E., Weisbach V., Winckler E., Kessler P., Schultze-Mosgau S., Wiltfang J., Neukam F.W. Morbidity of harvesting of bone grafts from the iliac crest for preprosthetic augmentation procedures: A prospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004;33:157–163. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J., Kerns D.G. Mechanisms of Guided Bone Regeneration: A Review. Open Dent. J. 2014;8:56–65. doi: 10.2174/1874210601408010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damien C.J., Parsons J.R. Bone graft and bone graft substitutes: A review of current technology and applications. J. Appl. Biomater. 1991;2:187–208. doi: 10.1002/jab.770020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannoudis P.V., Dinopoulos H., Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: An update. Injury. 2005;36((Suppl. S3)):S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young C., Terada S., Vacanti J., Honda M., Bartlett J., Yelick P. Tissue Engineering of Complex Tooth Structures on Biodegradable Polymer Scaffolds. J. Dent. Res. 2002;81:695–700. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigaux N., Pourchet L., Breton P., Brosset S., Louvrier A., Marquette C. 3D Bioprinting:principles, fantasies and prospects. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019;120:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jammalamadaka U., Tappa K. Recent Advances in Biomaterials for 3D Printing and Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018;9:22. doi: 10.3390/jfb9010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy S.V., Atala A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hölzl K., Lin S., Tytgat L., Van Vlierberghe S., Gu L., Ovsianikov A. Bioink properties before, during and after 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication. 2016;8:032002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/3/032002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moroni L., Burdick J.A., Highley C., Lee S.J., Morimoto Y., Takeuchi S., Yoo J.J. Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018;3:21–37. doi: 10.1038/s41578-018-0006-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J., Park S.A., Kim W.D., Ha T., Xin Y.-Z., Lee J., Lee D. Current Advances in 3D Bioprinting Technology and Its Applications for Tissue Engineering. Polymers. 2020;12:2958. doi: 10.3390/polym12122958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozbolat I.T., Hospodiuk M. Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2016;76:321–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Askari M., Naniz M.A., Kouhi M., Saberi A., Zolfagharian A., Bodaghi M. Recent progress in extrusion 3D bioprinting of hydrogel biomaterials for tissue regeneration: A comprehensive review with focus on advanced fabrication techniques. Biomater. Sci. 2021;9:535–573. doi: 10.1039/D0BM00973C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudapati H., Dey M., Ozbolat I. A comprehensive review on droplet-based bioprinting: Past, present and future. Biomaterials. 2016;102:20–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dou C., Perez V., Qu J., Tsin A., Xu B., Li J. A State-of-the-Art Review of Laser-Assisted Bioprinting and its Future Research Trends. ChemBioEng Rev. 2021;8:517–534. doi: 10.1002/cben.202000037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unagolla J.M., Jayasuriya A.C. Hydrogel-based 3D bioprinting: A comprehensive review on cell-laden hydrogels, bioink formulations, and future perspectives. Appl. Mater. Today. 2020;18:100479. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2019.100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y.-S., Chang S.-S., Ng H.Y., Huang Y.-X., Chen C.-C., Shie M.-Y. Additive Manufacturing of Astragaloside-Containing Polyurethane Nerve Conduits Influenced Schwann Cell Inflammation and Regeneration. Processes. 2021;9:353. doi: 10.3390/pr9020353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ning L., Chen X. A brief review of extrusion-based tissue scaffold bio-printing. Biotechnol. J. 2017;12:1600671. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derakhshanfar S., Mbeleck R., Xu K., Zhang X., Zhong W., Xing M. 3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances. Bioact. Mater. 2018;3:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandrycky C., Wang Z., Kim K., Kim D.-H. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016;34:422–434. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Z., Gao M., Lobo A.O., Webster T.J. 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Engineering for Medical Applications: The Classic and the Hybrid. Polymers. 2020;12:1717. doi: 10.3390/polym12081717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groll J., Burdick J.A., Cho D.-W., Derby B., Gelinsky M., Heilshorn S.C., Jüngst T., Malda J., Mironov V.A., Nakayama K., et al. A definition of bioinks and their distinction from biomaterial inks. Biofabrication. 2018;11:013001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aaec52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J.Y., Choi Y.-J., Shim J.-H., Park J.H., Cho D.-W. Development of a 3D cell printed structure as an alternative to autologs cartilage for auricular reconstruction. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2017;105:1016–1028. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Y., Li X., Zhang Y., Han Y., Chang F., Ding J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine. Cells. 2019;8:886. doi: 10.3390/cells8080886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai Q., Dong Z., Wang W., Li B., Jin Y. Dental stem cell and dental tissue regeneration. Front. Med. 2019;13:152–159. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0628-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernández-Monjaraz B., Santiago-Osorio E., Monroy-García A., Ledesma-Martínez E., Mendoza-Núñez V.M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells of Dental Origin for Inducing Tissue Regeneration in Periodontitis: A Mini-Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:944. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: New Directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones E., Yang X. Mesenchymal stem cells and bone regeneration: Current status. Injury. 2011;42:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyburz K.A., Anseth K.S. Synthetic Mimics of the Extracellular Matrix: How Simple is Complex Enough? Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015;43:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1297-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L., Yu F., Zheng L., Wang R., Yan W., Wang Z., Xu J., Wu J., Shi D., Zhu L., et al. Natural hydrogels for cartilage regeneration: Modification, preparation and application. J. Orthop. Transl. 2019;17:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung J.H.Y., Naficy S., Yue Z., Kapsa R., Quigley A., Moulton S.E., Wallace G.G. Bio-ink properties and printability for extrusion printing living cells. Biomater. Sci. 2013;1:763–773. doi: 10.1039/c3bm00012e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Busra M.F.M. Recent Development in the Fabrication of Collagen Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2019;20:992–1003. doi: 10.2174/1389201020666190731121016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopinathan J., Noh I. Recent trends in bioinks for 3D printing. Biomater. Res. 2018;22:11. doi: 10.1186/s40824-018-0122-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obregon F., Vaquette C., Ivanovski S., Hutmacher D.W., Bertassoni L. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting for Regenerative Dentistry and Craniofacial Tissue Engineering. J. Dent. Res. 2015;94:143S–152S. doi: 10.1177/0022034515588885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters M.D., Marnie C., Tricco A.C., Pollock D., Munn Z., Alexander L., McInerney P., Godfrey C.M., Khalil H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020;18:2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M.D.J., Horsley T., Weeks L., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang H.-W., Lee S.J., Ko I.K., Kengla C., Yoo J.J., Atala A. A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:312–319. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuss M.A., Harms R., Wu S., Wang Y., Untrauer J.B., Carlson M.A., Duan B. Short-term hypoxic preconditioning promotes prevascularization in 3D bioprinted bone constructs with stromal vascular fraction derived cells. RSC Adv. 2017;7:29312–29320. doi: 10.1039/C7RA04372D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Athirasala A., Tahayeri A., Thrivikraman G., Franca C.M., Monteiro N., Tran V., Ferracane J., Bertassoni L.E. A dentin-derived hydrogel bioink for 3D bioprinting of cell laden scaffolds for regenerative dentistry. Biofabrication. 2018;10:024101. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aa9b4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aguilar I.N., Smith L.J., Olivos D.J., 3rd, Chu T.-M.G., Kacena M.A., Wagner D.R. Scaffold-free bioprinting of mesenchymal stem cells with the regenova printer: Optimization of printing parameters. Bioprinting. 2019;15:e00048. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2019.e00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aguilar I.N., Olivos D.J., Brinker A., Alvarez M.B., Smith L.J., Chu T.-M.G., Kacena M.A., Wagner D.R. Scaffold-free bioprinting of mesenchymal stem cells using the Regenova printer: Spheroid characterization and osteogenic differentiation. Bioprinting. 2019;15:e00050. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2019.e00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chimene D., Miller L., Cross L.M., Jaiswal M.K., Singh I., Gaharwar A.K. Nanoengineered Osteoinductive Bioink for 3D Bioprinting Bone Tissue. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:15976–15988. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b19037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park J.H., Gillispie G.J., Copus J.S., Zhang W., Atala A., Yoo J.J., Yelick P.C., Lee S.J. The effect of BMP-mimetic peptide tethering bioinks on the differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in 3D bioprinted dental constructs. Biofabrication. 2020;12:035029. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab9492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubey N., Ferreira J.A., Malda J., Bhaduri S.B., Bottino M.C. Extracellular Matrix/Amorphous Magnesium Phosphate Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of Craniomaxillofacial Bone Tissue. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:23752–23763. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c05311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moncal K.K., Gudapati H., Godzik K.P., Heo D.N., Kang Y., Rizk E., Ravnic D.J., Wee H., Pepley D.F., Ozbolat V., et al. Intra-Operative Bioprinting of Hard, Soft, and Hard/Soft Composite Tissues for Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31:2010858. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202010858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moncal K.K., Aydın R.S.T., Godzik K.P., Acri T.M., Heo D.N., Rizk E., Wee H., Lewis G.S., Salem A.K., Ozbolat I.T. Controlled Co-delivery of pPDGF-B and pBMP-2 from intraoperatively bioprinted bone constructs improves the repair of calvarial defects in rats. Biomaterials. 2022;281:121333. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]