Abstract

In this work we identified the flgE gene encoding the flagellar hook protein from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Our results show that this gene is part of a flagellar cluster that includes the genes flgB, flgC, flgD, flgE, and flgF. Two different types of mutants in the flgE gene were isolated, and both showed a Fla− phenotype, indicating the functionality of this sequence. Complementation studies of these mutant strains suggest that flgE is included in a single transcriptional unit that starts in flgB and ends in flgF. In agreement with this possibility, a specific transcript of approximately 3.5 kb was identified by Northern blot. This mRNA is large enough to represent the complete flgBCDEF operon. FlgE showed a relatively high proline content; in particular, a region of 12 amino acids near the N terminus, in which four prolines were identified. Cells expressing a mutant FlgE protein lacking this region showed abnormal swimming behavior, and their hooks were curved. These results suggest that this region is involved in the characteristic quaternary structure of the hook of R. sphaeroides and also imply that a straight hook, or perhaps the rigidity associated with this feature, is important for an efficient swimming behavior in this bacterium.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium swims toward favorable environments in response to changes in the surrounding medium using its flagella; these appendages consist basically of a helical filament driven by a rotary motor. When flagella rotate in counterclockwise direction, the filaments coalesce in a bundle that functions as a propeller to push the bacterial cell body in a linear trajectory. On the contrary, when flagella reverse the sense of rotation the bundle is no longer stable, and the uncoordinated movement of each flagellum causes the cell to tumble. As revealed by early studies of electron microscopy, the flagellum consists of a filament, a curved hook, and a basal body (6). The filament and the hook are each composed of repeats of a single protein, flagellin and hook protein, respectively. These polypeptides do not share extensive similarity at the level of its primary sequence but both have the ability to self-assemble, and the resulting structures are capable of displaying polymorphic transitions; this capability has been suggested to be important in the motility of certain species of bacteria (12, 16, 22).

The structure of the filament has been the subject of extensive study during the last few decades, and various structural models have been proposed (18, 21, 33, 37). In contrast, the hook structure has been less well characterized; however, since the hook protein shares important features with flagellin, it has been suggested that hook and flagellin subunits have a similar folding pattern (20, 34, 35, 36).

The detailed knowledge about the structure and function of the flagellum in enterobacteria contrasts strongly with the limited data on these aspects that exist for other bacterial groups. However, it seems clear that as far as structure and function are concerned, a general pattern is shared by a great number of bacteria; some variations of this pattern have been introduced to allow the adaptation of certain bacteria to their particular habitat.

Rhodobacter sphaeroides, is a purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacterium that swims using a single subpolar flagellum that rotates unidirectionally. This rotation is interrupted periodically by stop events; during these periods, the flagellar helix relaxes and Brownian motion allows changes in the swimming direction (1).

The function and the structure of the flagellum of R. sphaeroides show interesting features. For instance, the motor rotates only in one direction; during the stop periods, the flagellar helix progressively relaxes into a coiled form, and the hook is actually a straight structure (1, 8, 29). As far as this last characteristic is concerned, there is no information about the importance of the straightness of the hook in the proper functioning of the flagellum; in addition, it is not known to what extent this structure is capable of suffering polymorphic interconversions. In this regard, the study of the hook of R. sphaeroides might give important information about the molecular bases that underlie the straightness of this structure.

Previously, we reported a fliK mutant from R. sphaeroides having an unusually long hook. This strain showed a similar phenotype to that of a polyhook mutant in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Purified hooks from the fliK mutant were shown to be straight and composed of a single protein, which presumably was the product of the flgE gene (8). In this work we identify the flgE gene from R. sphaeroides as part of a transcriptional unit that includes some genes encoding proteins involved in the basal body formation. Our data suggest that the flgBCDEF operon is expressed as a single mRNA, whose expression is dependent on a sigma-54 promoter identified upstream of flgB. Regarding the hook structure, we show evidence that a region near the N terminus of FlgE that has a high proline content is important in generating the characteristic straight hook as well as for normal swimming. Therefore, we propose that in this bacterium a straight hook, or perhaps its associated rigidity, is required for a proper swimming behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are described in Table 1. The plasmid pRS2000 carrying the flgE+ and flgF+ genes was constructed by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: 5′- CCAAGCTTCAATGTCGCCGCCGACACCGTC-3′, 5′-GCTCTAGACTCACTCGGGCGGACGCAGGAG-3′. The first oligonucleotide was primed 30 bp upstream of the initiation codon of flgE. A HindIII recognition site was included at the 5′ end. The second oligonucleotide carried an XbaI restriction site at the 5′ end and is complementary to the sequence located near the stop codon of flgE. The amplification product was sequenced and cloned in pRK415 under control of the plasmid promoters.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM103 | hsdR4 Δ(lac-pro) F′ traD36 proAB lacIq ZΔM15 | 3 |

| S17-1 | recA endA thi hsdR RP4-2-Tc::Mu::Tn7; Tpr Smr | 27 |

| R. sphaeroides | ||

| WS8 | Wild type; spontaneous Nalr | 30 |

| LC1 | WS8 flgE::aadA; Spcr Nalr | This work |

| TE1 | WS8 TnphoA derivative, flgE::TnphoA; Kmr Nalr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTZ19R | Cloning vector; Apr; pUC derivative | Pharmacia |

| pWM5 | Plasmid carrying the omega-Spc cassette | 17 |

| pJQ200mp18 | Suicide vector used for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria | 24 |

| pRK415 | pRK404 derivative, used for expression in R. sphaeroides | 13 |

| pU1800 | pSUP203 derivative carrying TnphoA; Cmr Tcr Kmr | 19 |

| pRS2000 | 2.0-kb fragment carrying flgE and flgE obtained by PCR, cloned into pRK415 | This work |

| pRS2001 | pRK415 carrying the flgEΔ1 allele | This work |

| pRS4300 | 4.3-kb PstI fragment from WS8 cloned into pTZ19R | This work |

| pRS4303/4303 | 4.3-kb PstI fragment from pRS4300 subcloned into pRK415/reversed direction. | This work |

| pRS5600 | 5.6-kb SalI fragment cloned into pTZ19R containing 4.6-kb of TnphoA plus 1 kb of TE1 DNA flanking the site of transposon insertion; Kmr Apr | This work |

Media and growth conditions.

R. sphaeroides cell cultures were grown photoheterotrophically in Sistrom medium (28) under continuous illumination at 30°C in either liquid or solid medium. Aerobic growth conditions were achieved in the dark with strong shaking. Motility plates were prepared using 1% tryptone, 0.7% NaCl, and 0.3% Bacto-Agar. Strains of E. coli were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (3). When needed, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: spectinomycin, 10 μg/ml; gentamicin, 30 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 1 μg/ml. For E. coli, the following antibiotics were used: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; tetracycline, 15 μg/ml; gentamicin, 30 μg/ml; and spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

The isolation of chromosomal DNA was performed as described elsewhere (3). Plasmid DNA preparations were carried out with Qiagen Mini or Midi Column Plasmid Purification Kits (Qiagen, Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.). DNA amplification was carried out with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and 0.5 μM concentrations of the appropriate oligonucleotides; the reaction was performed for 30 cycles in a GeneAmp PCR system (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing was carried out using the Thermosequenase kit (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) on single- or double-stranded clones. Southern hybridization was carried out using the PhotoGene system from Life Technologies (Rockville, Md.).

Transposon mutagenesis of R. sphaeroides.

pU1800 plasmid harboring the transposon TnphoA was mobilized into R. sphaeroides WS8 from E. coli S-17 by diparental mating (4). Transposon mutants were selected on agar plates containing kanamycin. Single independent colonies were tested for loss of motility by using swarm plate assays. Cells were also analyzed by dark-field microscopy. Ten independent mutants were selected for further characterization. The TnphoA insertion site of each mutant was cloned as a kanamycin-resistant SalI-fragment into pTZ19R. The chromosomal DNA flanking the TnphoA was sequenced.

DNA analysis.

Sequences were analyzed and compared with the protein database by using the BLAST server at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.), as well as the Genetics Computer Group software package. Predictions of secondary structure were done using the PSA server of the Biomolecular Engineering Research Center of Boston University.

Electron microscopy.

Bacterial cell suspensions were applied on Formvar-coated grids. Samples were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate and observed with a JEM-1200EXII electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan).

Motility assays.

A 5-μl sample of a stationary-phase culture was placed on the surface of swarm plates and incubated aerobically in the dark. The swarming capability was recorded as the ability of bacteria to move away from the inoculation point after 36 to 48 h. The motility of free-swimming bacteria was evaluated in an aliquot from aerobic or anaerobic cultures placed directly between a slide and a coverslip. The samples were observed with an Olympus microscope adapted for high-intensity dark-field illumination or using a Nikon microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC).

Construction of an flgE::aadA mutant.

To interrupt flgE with a selectable marker, we obtained an internal portion of the omega-Spc cassette by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GGAATTCCCTGAAGCGAGGGCAGATC-3′ and 5′-GGAATTCTCATGATATATCTCCCAAT-3′. An EcoRI recognition site was included at their 5′ ends. The PCR product obtained using these oligonucleotides excludes the transcriptional termination signals present in the flanking regions of the original cassette. The amplification product was cloned into the unique EcoRI site of pRS4303 located after amino acid 40 from the predicted FlgE sequence. The 5.5-kb PstI fragment carrying flgE::aad was subcloned into pJQ200mp18 (25). The resulting plasmid was introduced by transformation into E. coli S17-1 and subsequently transferred to R. sphaeroides by conjugation. Since pJQ200 cannot replicate in R. sphaeroides, the double recombination event was selected directly on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates in the presence of spectinomycin and 5% sucrose.

Construction of the flgEΔ1 allele.

To obtain the flgEΔ1 allele, two independent PCRs flanking the region to be deleted were carried out. The region encoding the N terminus of FlgE was amplified in one reaction using the oligonucleotide 5′-CGTCTAGAGAGCGTCACGGCCGCCTCGTC-3′, which primed at the C-terminal of flgD. This oligonucleotide also carried an XbaI recognition site at the 5′ end. The reverse oligonucleotide used in this reaction primed the sequence located immediately upstream of the deletion start point (5′-GTGACGTCCCCGACGGCGTCCTCGGTGGCGAAG-3′). At the 5′ end of this oligonucleotide, an AatII recognition site was included; the sequence of this site was designed to be in frame with the flgE open reading frame (ORF). The PCR product was cloned in pTZ19R and sequenced to confirm that no errors were introduced during the amplification reaction. The other PCR was carried out using the forward oligonucleotide 5′-GTGACGTCATCTACACCCGCGCGGGCGCC-3′, priming the sequence downstream of the end of the deletion site and carrying an AatII recognition site at the 5′ end. The reverse primer (5′-GGGGTACCTCCATGATCCGCCTCAGCTGC-3′) carried a KpnI restriction site at the 5′ end and was complementary to the sequence located near the flgE stop codon. The product of this reaction was also cloned in pTZ19R and sequenced. To join these fragments, the plasmid carrying the sequence corresponding to the 5′ end of the flgE gene was digested with XbaI and AatII, and the released insert was gel purified and subsequently cloned in the plasmid carrying the 3′ end of flgE, previously digested with XbaI and AatII. The resultant plasmid carrying the complete flgEΔ1 allele was sequenced at the junction point to confirm the correct insertion.

RNA isolation and Northern blot.

Total RNA was isolated from R. sphaeroides cells grown heterotrophically as described previously (3). For Northern blots, 20 μg of the sample was separated electrophoretically on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel. RNA was transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane with a pore size of 0.45 μm and then UV cross-linked to the filter by exposure to 120 J of UV irradiation. Filters were hybridized with denatured DNA probes for at least 18 h. The DNA probe was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by use of random primers using a commercial kit purchased to GIBCO-BRL.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequences of the R. sphaeroides flgB, flgC, flgD, flgE, and flgF genes have been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF133240.

RESULTS

Isolation of a strain carrying the allele flgE::TnphoA.

To identify the flgE gene from R. sphaeroides, we screened a bank of mutants unable to swim. This bank was obtained by transposon mutagenesis of the wild-type strain WS8. Since the transposon, TnphoA, carries the nptII gene conferring kanamycin resistance; after mutagenesis, individual colonies were selected on LB-kanamycin plates. The colonies obtained were subsequently tested for motility on swarm plates. A set of 10 independent nonmotile mutants was isolated.

In order to identify the insertion point of the transposon in each mutant, chromosomal DNA was purified and digested with SalI. A DNA fragment carrying the nptII gene from the transposon, as well as chromosomal DNA adjacent to the insertion site was cloned in pTZ19R. The sequence from these clones was determined and compared against the database from the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

The sequence obtained from the fragment derived from one of these mutants, the TE1 mutant, was found to be similar to the 3′ end of flgE and to the 5′ end of flgF from several bacterial species. This clone was named pRS5600.

Cloning of the wild-type flgE gene.

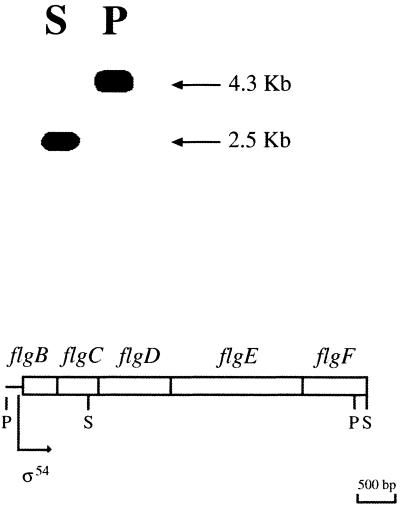

To clone a DNA fragment carrying the complete flgE gene, chromosomal DNA digested with either SalI or PstI was hybridized with a 1.2-kb DraI-SalI fragment from pRS5600. A 4.3-kb PstI fragment and a 2.5-kb SalI fragment were clearly detected (Fig. 1). The 4.3-kb PstI fragment was cloned in pTZ19R, this clone was named pRS4300. The complete sequence of this fragment revealed the presence of five ORFs that showed strong similarity to flgB, flgC, flgD, flgE, and flgF genes identified in other bacterial species (Fig. 1). Since this fragment carried the flgF gene truncated by the PstI site, the sequence was completed using an overlapping SalI fragment, carrying the flgF stop codon besides other flagellar genes in process to be characterized (B. González-Pedrajo, J. De la Mora, T. Ballado, L. Camarena, and G. Dreyfus, Genbank accession no. AF205139).

FIG. 1.

Genomic Southern blot of wild-type WS8 from R. sphaeroides. Chromosomal DNA digested with SalI (S) or PstI (P) was probed against a 1.2-kb DraI-SalI fragment derived from pRS5600 carrying the incomplete flgE and flgF genes. The organization of the flg genes identified in this work, with each ORF represented as an open box, is presented graphically below the blots. The restriction enzyme sites shown are SalI (S) and PstI (P). An arrow indicates the direction of transcription. A sequence similar to that of the sigma-54 consensus promoter located upstream the coding region of flgB is also indicated (ς54).

All of these ORFs start with the most common triplet ATG and end with TGA. The start and stop codons for these ORFs are almost contiguous, suggesting that they conform to a single transcriptional unit. In accordance with this possibility, the sequence analysis of the complete fragment does not show any potential coding region in the first 260 nucleotides; instead, a sequence similar to that of the ς54 consensus promoter was identified (TGGCAN6TTGCA).

The amino acid sequence predicted for these five ORFs was compared with their counterparts present in other bacteria. As it can be observed in Table 2, the highest degree of identity was obtained when these ORFs were compared to those from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of encoded proteins of R. sphaeroides flagellar genes with those of other bacterial species

| Gene product | % Similarity/% identitya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi | Serovar Typhimuriumb | S. meliloti | A. tumefaciens | |

| FlgB | 26.9/20.6 | 50.7/41.4 | 29.3/22.2 | 27.5/20.4 |

| FlgC | 38.6/27.7 | 46.2/37.3 | 36.7/27.2 | 33/26.4 |

| FlgD | 31.1/26 | 37.1/33 | − | − |

| FlgE | 35.9/28.9 | 38.8/32.1 | 37.0/29.1 | − |

| FlgF | − | 37.9/28.9 | 34.6/26.3 | 32.5/24.6 |

−, Not available in the data base.

S. enterica Serovar Typhimurium.

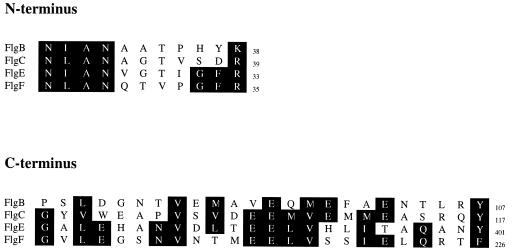

The N(I/L)AN motif was found in the N terminus from all the predicted amino acid sequences with the exception of FlgD. An additional GF(R/K) motif shared only by FlgE and FlgF was also identified (Fig. 2). In the C terminus a EE(M/L)VX8(Y/F) motif was found in FlgC, FlgE, and FlgF, which are all axial proteins (Fig. 2). A sequence that weakly resembles this consensus can also be detected in FlgB, whereas FlgD does not show any similarity to these axial proteins. Homma et al. (10, 11) have suggested that these conserved characteristics could play an important role in quaternary interactions that take place during assembly.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of axial proteins identified in this work. Conserved residues in the sequences are shaded.

The tendency to form coiled-coil structures was calculated using the algorithm of Lupas et al. (15); except for FlgD, all of these regions predicted a propensity to form coiled coils. The strongest probability to form coiled coils was predicted for the C termini of FlgB, FlgC, and FlgE.

Characterization of the mutant strain TE1.

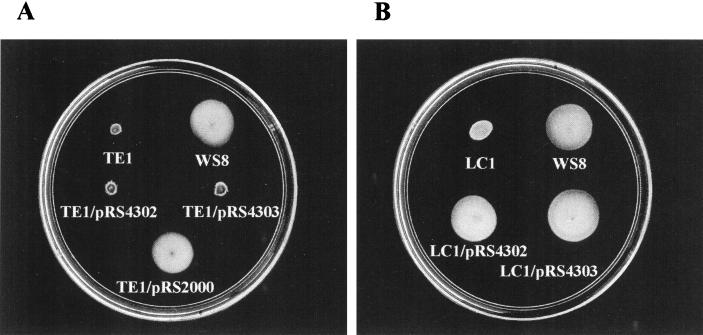

From the selection procedure used to isolate the TE1 mutant, we learned that this mutant is unable to form a swarm ring on soft agar plates (Fig. 3A). Also, according to the results obtained from the sequence analysis, we anticipated a Fla− phenotype for this mutant. The observation of TE1 cells by electron microscopy confirmed this expectation (data not shown). To recover TE1 cell motility, the 4.3-kb PstI fragment was cloned in a direct or reverse orientation from the pRK415 promoters; the resulting plasmids, pRS4302 or pRS4303, respectively, were both unable to complement TE1 cells (Fig. 3A). This result can be ascribed to the polar effect that the transposon exerts on the expression of the genes located downstream of flgE.

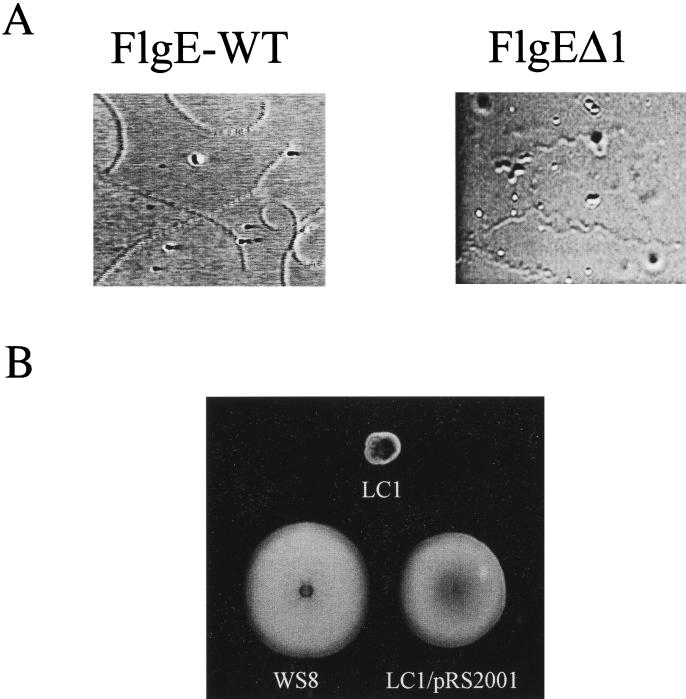

FIG. 3.

(A) Swarming assay of wild-type WS8, TE1 strain, and TE1 carrying different plasmids. (B) Swarming assay of wild-type WS8, LC1 strain, and LC1 complemented with pRS4302 and pRS4303.

Further studies showed that TE1 cells could be complemented using a DNA fragment carrying only flgE+ and flgF+ genes. This fragment was obtained from a specific PCR reaction, whose product was cloned into pRK415 (pRS2000). As expected, motility was recovered when the fragment was expressed from the promoters of pRK415 (Fig. 3A). This result supports the idea that flgF might be the last gene from the putative operon. We did not detect any possible hairpin structure corresponding with a hypothetical mRNA terminator downstream of flgF. However, the possibility remains that a ρ-dependent terminator could accomplish this function.

Isolation of a strain carrying a nonpolar mutation in flgE.

To confirm that the inability of the pRS4302 plasmid to complement the TE1 mutant was due to the polar effect of the TnphoA insertion, we decided to isolate a nonpolar flgE mutant. For this purpose, the omega cartridge was chosen to interrupt the coding region of flgE. As has been reported previously (17), this cassette carries strong terminator signals flanking the resistance marker; therefore, we removed these regions by PCR amplification. The PCR product was cloned in the EcoRI site present in the first half of flgE. The allele flgE::aadA was transferred to the chromosome of the wild-type strain by homologous recombination (see Materials and Methods). A mutant was isolated, and it was confirmed by Southern blotting that a double-recombination event occurred in this strain (data not shown). This mutant was named LC1 and, as expected, it showed Fla− phenotype (data not shown) and is unable to form a ring in swarm plates (Fig. 3B).

The pRS4302 and pRS4303 plasmids, which had failed to complement TE1 cells, were able to promote full motility in LC1 cells (Fig. 3B). The fact that the 4.3-kb PstI fragment was able to complement LC1 cells independently of the pRK415 promoters allows us to suggest that a promoter responsible for flgE expression is present in this fragment.

Characterization of the flgBCDEF operon.

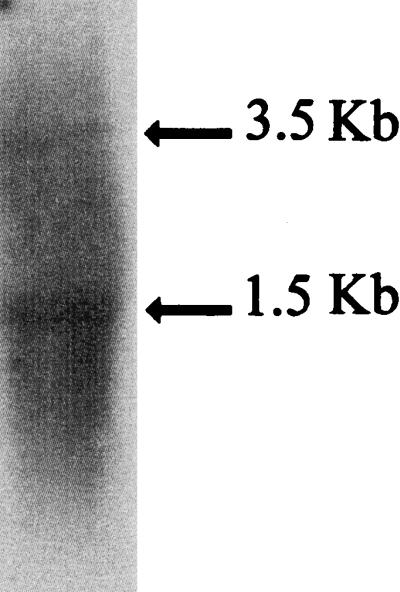

To obtain physical evidence supporting the hypothesis that the flgB, flgC, flgD, flgE, and flgF genes form an operon, we carried out a Northern blot hybridization using total RNA isolated from WS8 cells and an internal flgE fragment as a probe. Surprisingly, two different transcripts were detected (Fig. 4). The larger and less-abundant transcript (3.5 kb) is long enough to represent the complete mRNA of the flgBCDEF operon. The presence of this mRNA strongly supports the idea that flgE is expressed as a part of this operon. The smaller mRNA (1.5 kb) may represent specific cleavage of the complete transcript and/or an independent mRNA population expressed from an internal promoter within this transcriptional unit. This result will be further discussed in the next section.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of flgE transcripts. Total RNA extracted from WS8 was probed with a 32P-labeled flgE fragment as described in Materials and Methods.

Analysis of the FlgE sequence.

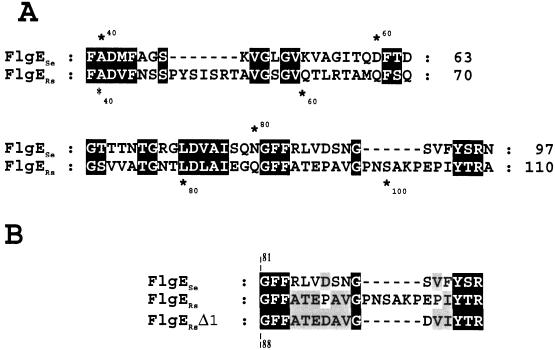

The conceptual translation of the flgE gene predicts a product of 42,660 Da. The N terminus of FlgE from R. sphaeroides (FlgERs) shows the sequences LSGL and NIANXXTXXGFR that are conserved in all of the FlgE proteins known so far (data not shown). An interesting feature of FlgERs that contrasts with FlgE from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (FlgESe) is the presence of two short insertions of 7 and 6 amino acids that are located after amino acids 46 and 90, respectively, from the sequence of Salmonella sp. (Fig. 5A). This last insertion, together with the four preceding amino acids and the two amino acids following it, presents an unusually high content of proline residues, i.e., 4 of 12 amino acids are prolines. In fact, FlgERs shows a 5.4% content of proline residues in contrast to 2.9 and 2.5% observed for FlgE proteins from Salmonella sp. and Sinorhizobium meliloti, respectively. These proline residues are distributed throughout the FlgERs sequence and are not only confined to the variable region, which is located between residues 148 to 260 from FlgESe (34).

FIG. 5.

(A) Sequence alignment of the FlgE proteins from R. sphaeroides and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium starting from residue number 39 and extending up to residue 110 from FlgERs. The residues that are similar were shaded. The sequence from R. sphaeroides shows two insertion sites that are absent in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium FlgE. (B) The region of FlgE was modified to obtain FlgERsΔ1. The residues GFF are placed in an alignment equivalent to those in panel A in order to facilitate its comparison. The amino acid sequences of FlgERs and FlgESe are included.

To investigate whether this proline-rich region located near the N terminus of FlgERs was in some way required for proper function of the hook, we deleted and modified this region, as depicted in Fig. 5B, to yield flgEΔ1. This allele was cloned in pRK415 under control of the vector promoters (pRS2001 plasmid) and then transferred to LC1 cells (flgE::aadA) by conjugation. When free-swimming cells were analyzed directly under the microscope, we observed that most of the exconjugants showed an atypical swimming behavior; illustrated in Fig. 6A. The swimming paths of the mutant cells compared with those of the wild-type cells show a corkscrew trajectory that contrasts with the slightly curved trajectory of the wild-type cells. In a swarm plate, the cells expressing FlgEΔ1 showed a slight reduction (ca. 15 to 20%) in the ring size compared with that produced by wild-type cells (Fig. 6B). To determine if the quaternary structure of the hook was conserved in the mutant cells, sheared filaments from a culture of LC1/pRS2001 cells were analyzed by electron microscopy. A large amount of filament fragments were detected, some of them had the hook still attached. We observed that in contrast with the straight structure of the wild-type hooks, most of the hooks assembled with FlgEΔ1 were curved but conserved the distinctive cross-hatched helical pattern characteristic of this structure (Fig. 7A). As a control, the same procedure was done for wild-type cells, and only straight hooks were detected (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 6.

(A) Swimming paths of mutant cells expressing FlgEΔ1 protein and of wild-type cells. The paths were obtained using Adobe Photoshop v. 4. The images were obtained from individual frames imported from videotapes. (B) Swarming assays of wild-type WS8, LC1 strain, and LC1/pRS2001 expressing FlgEΔ1 protein.

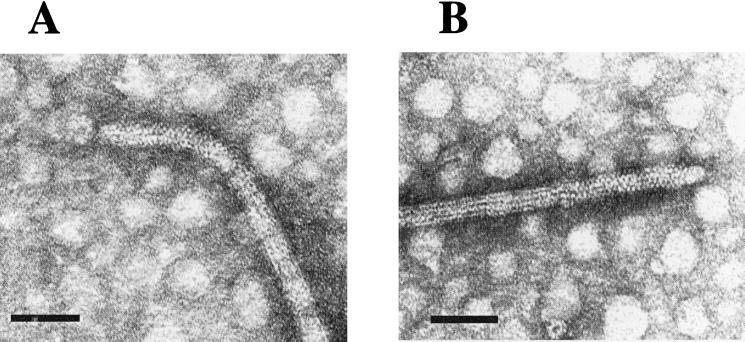

FIG. 7.

Negatively stained electron micrographs of hook structures. (A) Sample from cells expressing FlgEΔ1 protein. (B) Sample from wild-type cells. Bar, 50 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this work we identified the gene that encodes the hook protein from R. sphaeroides, as well as the genes encoding for the proximal rod proteins FlgB, FlgC, and FlgF and the scaffolding protein FlgD.

In addition, we showed three lines of evidence supporting the idea that flgE, together with the other four flg genes reported in this work, form an operon. First, the fact that TE1 cells (flgE::TnphoA) were complemented with a plasmid carrying both flgE+ and flgF+ genes, whereas LC1 cells (flgE::aadA) were complemented with only the flgE+ gene, suggests that the insertion of TnphoA in flgE exerts a polar effect on the expression of the genes located downstream. Therefore, flgF must be the last gene of this operon. Second, since LC1 cells were complemented with the 4.3-kb PstI fragment independently of the vector promoters, the presence of a promoter responsible for the expression of flgE was suggested. We ascribed this promoter function to the first 260-bp of this fragment because a sequence similar to the ς54 consensus promoter was identified. In fact, we recently showed evidence that this sequence is indeed a functional ς54 promoter (23). Finally, in a Northern blot experiment using a fragment from the flgE gene as a probe, we found a 3.5-kb mRNA. The detection of this large mRNA supports the idea that flgE is transcribed as part of a polycistronic messenger. The presence of an additional 1.5-kb mRNA on the Northern blot suggests the possibility that an internal promoter is also used to express flgE. Alternatively, this small mRNA could be produced by cleavage of the 3.4-kb transcripts; this possibility is supported by the fact that the 1.5-kb mRNA is the strongest signal on the blot; however, no evidence of a consensus promoter sequence was found within the genes located upstream of flgE (data not shown). The processing of large mRNAs has been already reported for the puc and the puf messengers in R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides. This process seems to control the stoichiometry of the structural proteins encoded by the primary transcripts of these operons (9, 14, 38). It remains to be investigated if specific mRNA cleavage might occur in the flgBCDEF transcript of R. sphaeroides.

The results summarized above allow us to propose that flgBCDEF genes are transcribed as an mRNA of 3.5 kb. This transcript seems to be synthesized from the ς54-dependent promoter located upstream of flgB and ends downstream of flgF.

As shown in Table 2, FlgB and FlgC proteins showed the highest homology value when compared with their counterparts from enteric bacteria, such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (γ subclass) In contrast, a low value was found when they were compared with their counterparts found in α subclass of Proteobacteria, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens and S. meliloti. Since R. sphaeroides also belongs to the α subclass of Proteobacteria, this result was unexpected. By the same token, we noticed that the order of the genes flgBCDEF in R. sphaeroides is similar to that found in these enteric bacteria, whereas S. meliloti and A. tumefaciens show a different gene order, which is similar between them (5, 31). We believe that an α-proteobacterium may exist that has a high degree of similarity to FlgB and FlgC from R. sphaeroides and that could perhaps show the same gene order.

We observed that, regarding the hook structure, the primary structure of FlgERs is highly similar to that of FlgESe; however, as mentioned in the previous section, FlgERs shows a high proline content, in particular in two small insertions located near the N-terminal region of this protein. Since it has been reported that proline residues are involved in the structural rigidity in some proteins (32), we removed one of these insertions in order to investigate its role in the structure of the hook.

The hook assembled with FlgEΔ1 subunits was observed as a curved structure. This result indicates that this region does not seem to be important for the export or assembly of FlgE monomers; instead, it seems to be involved in the straightness of the hook structure. The possibility that artifacts were introduced when samples were prepared was discarded since under the same conditions of temperature and pH the samples from wild-type cells showed straight hooks.

In R. sphaeroides, the filament of free-swimming cells shows polymorphic transitions; two polymorphs, coiled and helical, have been associated with periods of stop and swimming respectively (1). A third waveform has been recently reported (2), in this case, when the flagellum rotated rapidly a straight filament or perhaps a low-amplitude helix was identified. In addition, the filament also suffers polymorphic interconversions in vitro, when the pH or the ionic strength is changed (26). For E. coli, a strain carrying a point mutation in the flgL gene, encoding the HAP3 protein, is unable to form swarm rings in 0.28% agar. In this condition, the filaments undergo torque-induced transformations to straight forms that impair motility (7). Therefore, the ability to control flagellar transitions seems to be important for proper flagellar function. It will be interesting to study whether the filament of the strain expressing the FlgEΔ1 protein undergoes abnormal transitions during swimming.

A mutant strain producing straight hooks in Salmonella has been reported. In this strain, the export of FlgM was dependent on the NaCl concentration. Observation of the swimming behavior of this strain at a concentration of NaCl allowing good flagellation suggested that the function of the hook had deteriorated, since the flagellar bundles were not as tight as those of the wild-type cells (25). In the case of R. sphaeroides, a strain showing a curved hook produced normal amounts of flagellin, but the swimming behavior both in swarm plates as well as in liquid medium was altered. Although it is not possible to be certain that this anomalous behavior is directly related to the presence of a curved hook; it seems clear that this atypical swimming behavior is the consequence of the deletion of the proline-rich region from the N terminus of FlgE. This mutation, in addition to causing the assembly of a curved hook, could also affect the hook intrinsic flexibility or its capability to correctly transmit torque. We believe that the study of hook shape mutants in a uniflagellated bacterium may help clarify the role of the hook (the so-called “universal joint”) in the swimming action of this microorganism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T.B. and L.C. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Aurora V. Osorio and Francisco Javier de la Mora for technical assistance. We also thank the Molecular Biology Unit of the IFC for the synthesis of oligonucleotides and the Microscopy Unit of the IFC for technical support with electron microscopy. We thank Robert M. Macnab from Yale University for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grant IN221598 from DGAPA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage J P, Macnab R M. Unidirectional, intermittent rotation of the flagellum of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:514–518. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.514-518.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage J P, Pitta T P, Vigeant M A, Packer H L, Ford R M. Transformations in flagellar structure of Rhodobacter sphaeroides and possible relationship to changes in swimming speed. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4825–4833. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4825-4833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies J, Donohue T J, Kaplan S. Construction, characterization, and complementation of a Puf mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:320–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.320-329.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deakin W J, Parker V E, Wright E L, Ashcroft K J, Loake G J, Shaw C H. Agrobacterium tumefaciens possesses a fourth flagelin gene located in a large gene cluster concerned with flagellar structure, assembly and motility. Microbiology. 1999;145:1397–1407. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DePamphilis M, Adler J. Fine structure and isolation of the hook-basal body complex of flagella from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1971;105:384–395. doi: 10.1128/jb.105.1.384-395.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahrner K A, Block S M, Krishnaswamy S, Parkinson J S, Berg H C. A mutant hook-associated protein (HAP3) facilitates torsionally induced transformations of the flagellar filament of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:173–186. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Pedrajo B, Ballado T, Campos A, Sockett R E, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. Structural and genetic analysis of a mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8 deficient in hook length control. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6581–6588. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6581-6588.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heck C, Balzer A, Fuhrmann O, Klug G. Initial events in the degradation of the polycistronic puf mRNA in Rhodobacter capsulatus and consequences for further processing steps. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:90–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homma M, Kutsukake K, Hasebe M, Iino T, Macnab R M. FlgB, FlgC, FlgF and FlgG. A family of structurally related proteins in the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:465–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90365-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homma M, DeRosier D J, Macnab R M. Flagellar hook and hook-associated proteins of Salmonella typhimurium and their relationship to other axial components of the flagellum. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:819–832. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato S, Okamoto M, Asakura S. Polymorphic transition of the flagellar polyhook from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1984;173:463–476. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBlanc H, Lang A S, Beatty J T. Transcript cleavage, attenuation, and an internal promoter in the Rhodobacter capsulatus puc operon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4955–4960. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4955-4960.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R I, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metcalf W W, Wanner B L. Construction of new β-glucuronidase cassettes for making transcriptional fusions and their use with new methods for allele replacement. Gene. 1993;129:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90691-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimori Y, Yamashita I, Murata K, Fujiyoshi Y, Yonekura K, Toyoshima C, Namba K. The structure of the R-type straight flagellar filament of Salmonella at 9 Å resolution by electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:69–87. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore M D, Kaplan S. Construction of TnphoA gene fusions in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: isolation and characterization of a respiratory mutant unable to utilize dimethyl sulfoxide as a terminal electron acceptor during anaerobic growth in the dark on glucose. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4385–4394. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4385-4394.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan D G, Macnab R M, Francis N R, DeRosier D J. Domain organization of the subunit of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar hook. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:79–84. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan D G, Owen C, Melanson L A, DeRosier D J. Structure of bacterial flagellar filaments at 11 Å resolution: packing of the alpha-helices. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:88–110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Namba K, Vonderviszt F. Molecular architecture of bacterial flagellum. Q Rev Biophys. 1997;30:1–65. doi: 10.1017/s0033583596003319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poggio S, Aguilar C, Osorio A, González-Pedrajo B, Dreyfus G, Camarena L. ς54 promoters control expression of genes encoding the hook and basal body complex in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5787–5792. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5787-5792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quandt J, Hynes M F. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1993;127:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito T, Ueno T, Kubori T, Yamaguchi S, Iino T, Aizawa S-I. Flagellar filament elongation can be impaired by mutations in the hook protein FlgE of Salmonella typhimurium: a possible role of the hook as a passage for the anti-sigma factor FlgM. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1129–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah D S, Perehinec T, Stevens S M, Aizawa S-I, Sockett R E. The flagellar filament of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: pH-induced polymorphic transitions and analysis of the fliC gene. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5218–5224. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5218-5224.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sistrom W R. The kinetics of the synthesis of photopigments in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Gen Microbiol. 1962;28:607–616. doi: 10.1099/00221287-28-4-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sockett R E, Armitage J P. Isolation, characterization, and complementation of a paralyzed flagellar mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2786–2790. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2786-2790.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sockett R E, Foster J C A, Armitage J P. Molecular biology of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides flagellum. FEMS Symp. 1990;53:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sourjik V, Sterr W, Platzer J, Bos I, Haslbeck M, Schmitt R. Mapping of 41 chemotaxis, flagellar and motility genes to a single region of the Sinorhizobium meliloti chromosome. Gene. 1998;223:283–290. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian H, Yu L, Mather M W, Yu C A. Flexibility of the neck region of the rieske iron-sulfur protein is functionally important in the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27953–27959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trachtenberg S, DeRosier D J. A molecular switch: subunit rotations involved in the right-handed to left-handed transitions of Salmonella typhimurium flagellar filaments. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:67–77. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90381-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uedaira H, Morii H, Ishimura M, Taniguchi H, Namba K, Vonderviszt F. Domain organization of flagellar hook protein from Salmonella typhimurium. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:126–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vonderviszt F, Ishima R, Akasaka K, Aizawa S-I. Terminal disorder: a common structural feature of the axial proteins of bacterial flagellum? J Mol Biol. 1992;226:575–579. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90616-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vonderviszt F, Zavodszky P, Ishimura M, Uedaira H, Namba K. Structural organization and assembly of flagellar hook protein from Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:520–532. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamashita I, Hasegawa K, Suzuki H, Vonderviszt F, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Namba K. Structure and switching of bacterial flagellar filaments studied by X-ray fiber diffraction. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:125–132. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y S, Kiley P J, Donohue T J, Kaplan S. Origin of the mRNA stoichiometry of the puf operon in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:10366–10374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]