Abstract

As an extension of our research against COVID-19, a multiphase in silico approach was applied in the selection of the three most common inhibitors (Glycyrrhizoflavone (76), Arctigenin (94), and Thiangazole (298)) against papain-like protease, PLpro (PDB ID: 4OW0), among 310 metabolites of natural origin. All compounds of the exam set were reported as antivirals. The structural similarity between the examined compound set and S88, the co-crystallized ligand of PLpro, was examined through structural similarity and fingerprint studies. The two experiments pointed to Brevicollin (28), Cryptopleurine (41), Columbamine (46), Palmatine (47), Glycyrrhizoflavone (76), Licochalcone A (87), Arctigenin (94), Termilignan (98), Anolignan B (99), 4,5-dihydroxy-6″-deoxybromotopsentin (192), Dercitin (193), Tryptanthrin (200), 6-Cyano-5-methoxy-12-methylindolo [2, 3A] carbazole (211), Thiangazole (298), and Phenoxan (300). The binding ability against PLpro was screened through molecular docking, disclosing the favorable binding modes of six metabolites. ADMET studies expected molecules 28, 76, 94, 200, and 298 as the most favorable metabolites. Then, molecules 76, 94, and 298 were chosen through in silico toxicity studies. Finally, DFT studies were carried out on glycyrrhizoflavone (76) and indicated a high level of similarity in the molecular orbital analysis. The obtained data can be used in further in vitro and in vivo studies to examine and confirm the inhibitory effect of the filtered metabolites against PLpro and SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: papain-like protease, SARS-CoV-2, natural products, structural similarity, molecular docking, ADMET, DFT

1. Introduction

As of 26 July 2022, the WHO stated the confirmation of the incidence of 57,223,945 COVID-19 infections and 6,390,401 deaths [1]. Accordingly, a constant search in the field of drug discovery should be sustained to discover a cure.

Cheminformatics (computational- in silico) labels the connection between informatics and chemistry [2]. This approach applies the software in the field of chemistry [3] and has been used effectively to predict a cure against COVID-19 [4,5,6]. The chemoinformatic approach was also employed efficiently in drug discovery [7], drug molecular design [8,9], computational chemistry [10,11], toxicity prediction [12], ADMET assessment [13], and DFT calculation [14].

Human interest in the use of natural products has been back-traced for thousands of years [15,16]. The power of natural products as antiviral medicines has been confirmed in several scientific reports [17,18,19,20].

PLpro is a crucial protein in the coronavirus that has an essential role in the processing mechanism of viral polyproteins. This step results in the generation of an efficient replicase complex [21]. PLpro has another essential role against human immunity through post-translational modifications on human proteins [22].

Against COVID-19, we employed in silico methods to disclose the potential inhibition of several types of natural compounds. For example, four isoflavonoids [23] and three alkaloids [24] were proposed to exert promising anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities. We designed and applied in silico experiments to recommend the most fitting inhibitor against certain essential enzymes of SARS-CoV-2 such as SARS-CoV-2 nsp10 [25], SARS-CoV-2 PLpro [26], SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex [27], SARS-CoV-2 MPro [28,29], and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp [30].

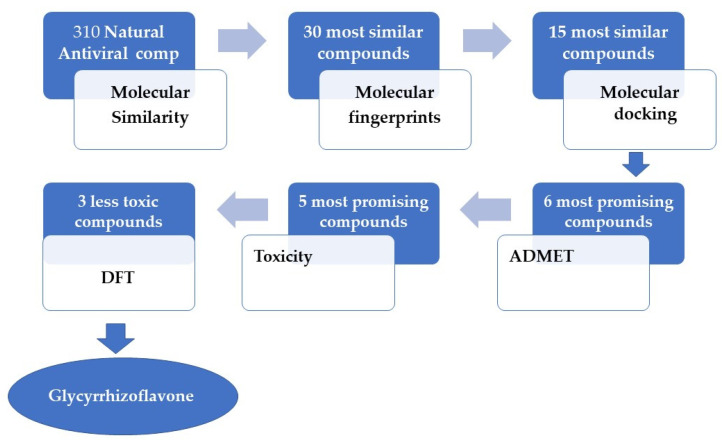

In the current study, we report the use of several computational filtration methods on 310 metabolites of natural origin that belong to diverse chemical classes and are reported as antivirals (Figure S1 and Table S1). Our experiments revealed the most expected inhibitors of human coronavirus PLpro among them. We depended on the reported similarities between the PLpro of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In silico protocol to select the most promising candidate against PLpro.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Similarity

It is worth mentioning that S88 was used as a positive control (lead molecule) in this work as S88 is the co-crystallized ligand of our target protein and has a reported binding mode. Additionally, currently, there are no FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of coronavirus targeting PLpro. Accordingly, it was found that S88 may serve as a good candidate to check the similarity of our compounds against it.

The following descriptors (H-bond donor (HBA) [31], H-bond acceptor (HBD) [32], partition coefficient (ALog p) [33], molecular weight (M. Wt) [34], rotatable bonds [35], rings, and aromatic rings [36] besides molecular fractional polar surface area (MFPSA) [37]) were examined between the 310 metabolites (Figure S1, Supplementary data) and S88 using Discovery Studio software (Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). The degree of likeness was calculated through the computation of minimum distances. The minimum distances were computed based on the variations in the aforementioned parameters and represent the computed quantitative difference in the structure between S88 and the examined compounds and are inversely proportional to the similarity degree.

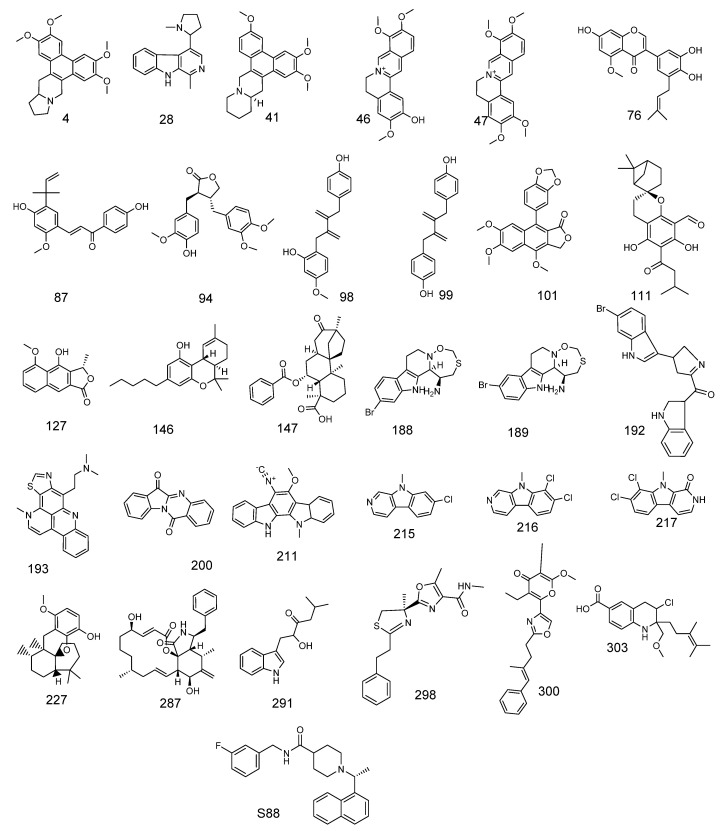

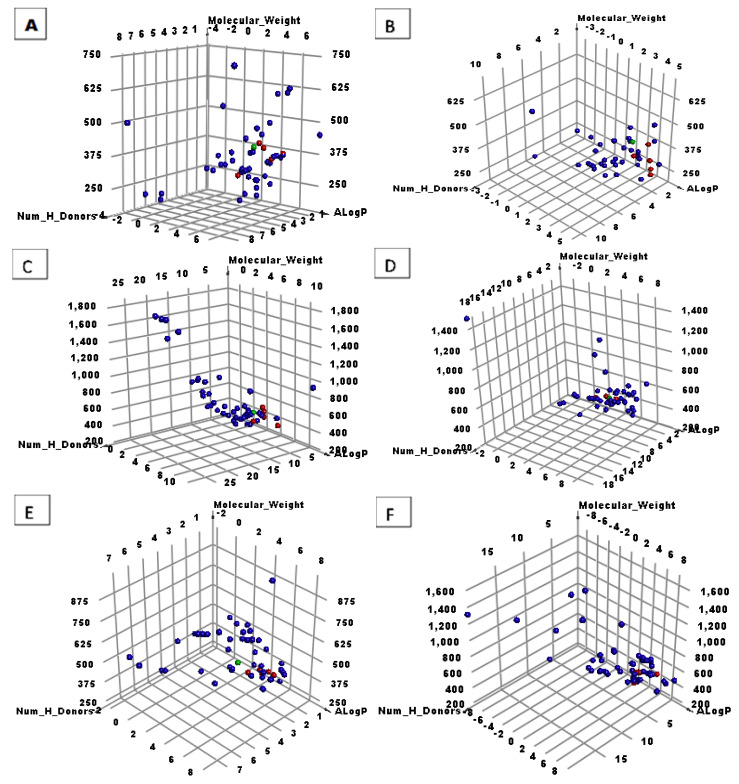

The 310 molecules were spit into five equal groups of 50 molecules each, and one (last group) that contained 60 molecules. The study determined the 30 most suitable metabolites (Figure 2 and Figure 3, and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Thirty molecules with good molecular similarity with S88.

Figure 3.

The similarity outputs of the tested compounds and S88. Green balls = S88, red balls = similar molecules, blue balls = not similar molecules. (A) First 50 molecules, (B) second 50 molecules, (C) third 50 molecules, (D) fourth 50 molecules, (E) fifth 50 molecules, and (F) last 60 molecules.

Table 1.

Structural properties of the most similar molecules to S88.

| Comp. | Molecular Formula | ALog p | M. Wt | HBA | HBD | Rotatable Bonds | Rings | Aromatic Rings | MFPSA | Minimum Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | C24H27NO4 | 2.658 | 394.483 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0.102 | 0.654 |

| 28 | C17H19N3 | 1.457 | 266.361 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0.119 | 0.693 |

| 41 | C24H27NO3 | 3.131 | 378.484 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0.083 | 0.546 |

| 46 | C20H20NO4 | 3.936 | 338.377 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0.149 | 0.709 |

| 47 | C21H22NO4 | 4.161 | 352.404 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.11 | 0.714 |

| 76 | C21H20O6 | 3.98 | 368.38 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.257 | 1.101 |

| 87 | C21H22O4 | 4.667 | 338.397 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.178 | 1.102 |

| 94 | C21H24O6 | 3.743 | 372.412 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0.192 | 1.057 |

| 98 | C19H20O3 | 4.784 | 296.36 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0.153 | 1.100 |

| 99 | C18H18O2 | 4.8 | 266.334 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.14 | 1.108 |

| 101 | C22H18O7 | 3.584 | 394.374 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0.192 | 0.356 |

| 111 | C23H30O5 | 4.65 | 386.481 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0.209 | 0.486 |

| 127 | C14H12O4 | 2.466 | 244.243 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0.235 | 0.539 |

| 146 | C21H30O2 | 6.109 | 314.462 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0.084 | 0.493 |

| 147 | C27H34O5 | 3.325 | 437.548 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0.182 | 0.412 |

| 188 | C14H16BrN3OS | 1.287 | 355.273 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.282 | 0.789 |

| 189 | C14H16BrN3OS | 1.287 | 355.273 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.282 | 0.789 |

| 192 | C21H18BrN3O | 3.919 | 408.291 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0.168 | 0.418 |

| 193 | C21H20N4S | 2.122 | 361.483 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 0.167 | 0.509 |

| 200 | C15H8N2O2 | 2.331 | 248.236 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.222 | 0.670 |

| 211 | C21H17N3O | 4.078 | 327.379 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0.176 | 0.529 |

| 215 | C12H9ClN2 | 3.043 | 216.666 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.084 | 0.582 |

| 216 | C12H8Cl2N2 | 3.707 | 251.111 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.076 | 0.558 |

| 217 | C12H8Cl2N2O | 2.846 | 267.111 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0.142 | 0.578 |

| 227 | C22H32O3 | 5.507 | 344.488 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.101 | 0.798 |

| 287 | C29H37NO5 | 4.1 | 479.608 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0.196 | 0.679 |

| 291 | C15H19NO2 | 2.932 | 245.317 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.198 | 0.524 |

| 298 | C18H21N3O2S | 2.716 | 343.443 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0.252 | 0.600 |

| 300 | C23H25NO4 | 5.22 | 379.449 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0.149 | 0.473 |

| 303 | C19H26ClNO3 | 3.006 | 350.86 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0.158 | 0.650 |

| S88 | C25H27FN2O | 3.098 | 391.501 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 0.083 |

2.2. Filter Using Fingerprints

Various computational methods that describe the similarities between different molecules have gained more interest in drug discovery [38]. One of the most helpful techniques in this approach is fingerprints [39]. The fingerprint study includes binary strings that compute the existence or absence of vital sub-structural fragments to calculate the structural similarity between molecules. This technique is currently utilized in virtual screening and detection of similarities between hit compounds and the lead one. The main difference between the fingerprints and molecular similarity studies is that the first individually calculates the presence and or absence of certain descriptors in S88 and the examined compounds, while molecular similarity calculates the degree of similarity between them as a whole structure.

The fingerprints technique was carried out using Discovery Studio software and examined the following parameters: HBA, HBD [40], charge [41], hybridization [42], positive and negative ionizable [43], halogen, aromatic, or none of them besides the ALogP category of atoms. All the mentioned parameters were converted to pits by the computer. Then, the computer calculated the bits in both S88 and the target compounds (SA), in the target compounds only (SB), or S88 only (SA). The identification of the most similar (that have the most identical molecular fingerprints) compounds to S88 is important to pick compounds with a higher degree of similarities. The most similar compounds are expected to exert greater protein binding and activity.

The study (Table 2) favored 28, 41, 46, 47, 76, 87, 94, 98, 99, 192, 193, 200, 211, 298, and 300 due to their similarity with S88.

Table 2.

Fingerprint similarity between the tested molecules and S88.

| Comp. | Similarity | SA | SB | SC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S88 | 1.000 | 565 | 0 | 0 |

| Brevicollin (28) | 0.614 | 304 | −70 | 261 |

| Cryptopleurine (41) | 0.642 | 401 | 60 | 164 |

| Columbamine (46) | 0.605 | 353 | 18 | 212 |

| Palmatine (47) | 0.584 | 363 | 57 | 202 |

| Glycyrrhizoflavone (76) | 0.561 | 329 | 21 | 236 |

| Licochalcone A (87) | 0.645 | 354 | −16 | 211 |

| Arctigenin (94) | 0.591 | 355 | 36 | 210 |

| Termilignan (98) | 0.635 | 343 | −25 | 222 |

| Anolignan B (99) | 0.615 | 346 | −2 | 219 |

| 4,5-dihydroxy-6″-deoxybromotopsentin (192) | 0.720 | 394 | −18 | 171 |

| Dercitin (193) | 0.621 | 357 | 10 | 208 |

| Tryptanthrin (200) | 0.633 | 337 | −33 | 228 |

| 6-Cyano-5-methoxy-12-methylindolo [2, 3A] carbazole (211) | 0.594 | 329 | −11 | 236 |

| Thiangazole (298) | 0.580 | 307 | −36 | 258 |

| Phenoxan (300) | 0.574 | 354 | 52 | 211 |

SA: The number of bits in S88 and target compound, SB: The number of bits in target compound but not S88, SC: The number bits in S88 but not the target.

2.3. Docking Studies

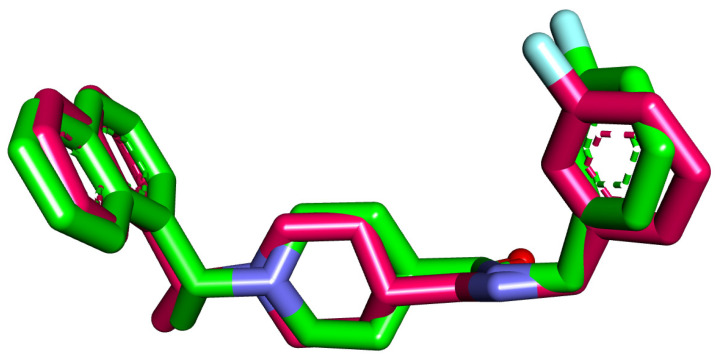

The docking analysis of 28, 41, 46, 47, 76, 87, 94, 98, 99, 192, 193, 200, 211, 298, and 300 was carried out against the coronavirus PLpro enzyme’s binding site (PDB ID: 4OW0). The crystallized ligand (S88) was used as a reference compound. For each compound, 30 run poses were carried out. The applied procedure of molecular docking was verified through the there-docking of S88 against the PLpro active site for another time. The small value of the RMSD (0.98 Å) between the two poses indicated the applicability of the applied protocol (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Superimposition of the co-crystallized pose (magenta) and the re-docking pose (turquoise) of the same ligand (S88) in the active site of the PLpro enzyme.

Differentiation between the tested compounds for their binding affinity was dependent on certain factors. (i) The first factor is the correct binding mode of a tested compound. The compound that exerted a binding mode very close to S88 was expected to have a good affinity against PLpro. The correct binding modes were determined according to the nature of the interactions (hydrogen or hydrophobic bonds) with the specific amino acid residues in the active pocket of PLpro. This factor is critical as a compound with the correct binding mode is expected to have a higher affinity than a compound with high binding energy having an incorrect binding mode. Therefore, the incorrect binding mode, resulting in incorrect affinity predictions, decreases the compound’s rate of virtual screening [44,45]. (ii) Gibbs free energy (ΔG binding) indicates the stability of the obtained conformation between the tested compound and PLpro (Table 3). According to the thermodynamic balance law, the value of ΔG is inversely proportional to the stability of the examined molecule and indicates that binding with PLpro will occur spontaneously. In other words, the increase in the negative free energy of a compound (reactant) will increase the reaction spontaneously and result in more stable conformations [46,47].

Table 3.

Binding free energies (calculated ΔG in Kcal/mol) of the examined compounds and S88 as a reference compound against PLpro.

| Comp. | ΔG [Kcal/mol] |

Comp. | ΔG [Kcal/mol] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | −40.44 | 99 | −39.43 |

| 41 | −47.34 | 192 | −30.85 |

| 46 | −44.13 | 193 | −44.02 |

| 47 | −46.06 | 200 | −41.31 |

| 76 | −51.63 | 211 | −37.33 |

| 87 | −35.48 | 298 | −48.46 |

| 94 | −50.82 | 300 | −33.61 |

| 98 | −52.21 | S88 | −59.13 |

The molecular docking energy for compounds 76, 94, and 98 exhibited final values of −51.63, −50.82, and 52.21 kcal/mol, respectively. These values of free energies are the highest score indicating the spontaneity of the interactions and the stability of these compounds in the active site. Moreover, compounds 76, 94, and 98 have correct binding modes as these compounds formed many HBs with the crucial amino acid residues in the active sites. On the other hand, compounds 193 (ΔG = −44.02), 200 (ΔG = −41.31), and 298 (ΔG = −48.46) showed less free energies than some of the other tested compounds but had correct binding modes. For this reason, such compounds were selected for further investigation.

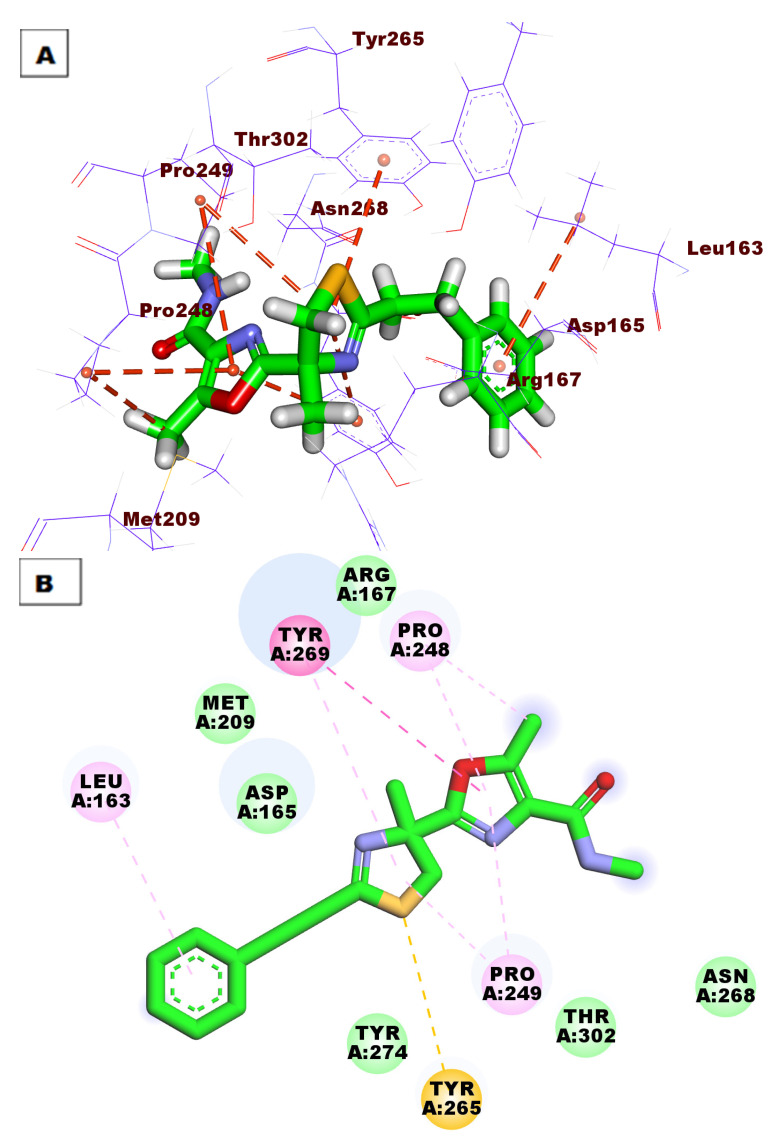

The proposed binding mode of S88 expressed a ΔG of −59.13 kcal/mol. S88 made one HB between its amide moiety and Tyr269. Additionally, the naphthyl moiety made eight hydrophobic interactions (HI) withAsp165, Met209, Arg167, Ala247, Thr302, Pro248, and Pro249. The ethyl bridge was included in two hydrophobic interactions with Pro249 and Tyr265. The piperidine moiety formed two hydrophobic bonds with Tyr265 and Tyr269. (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

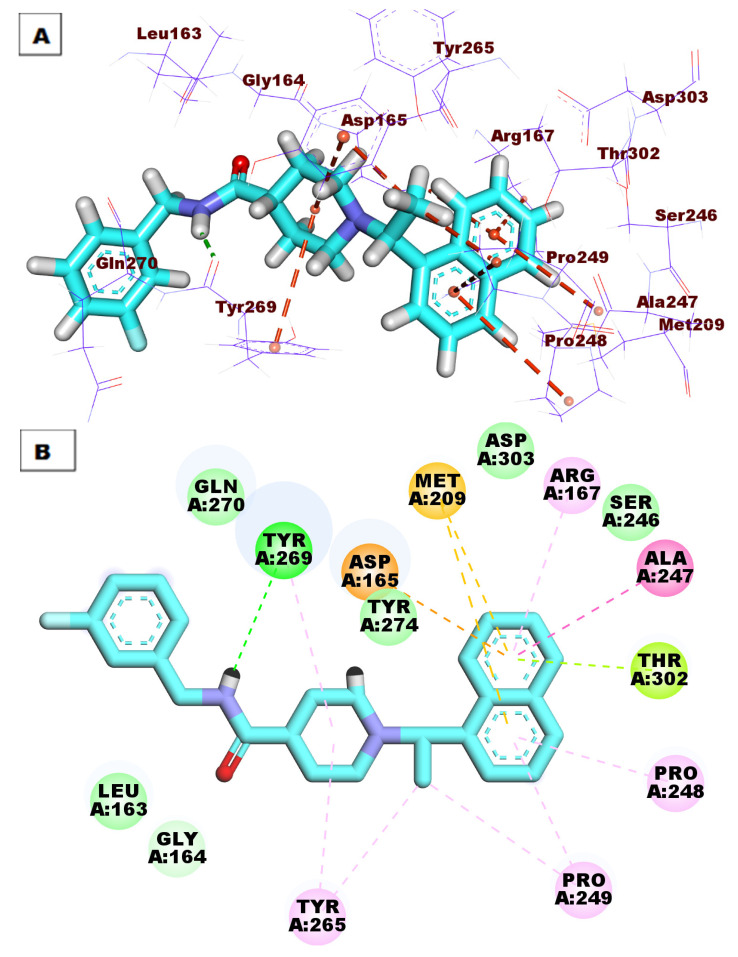

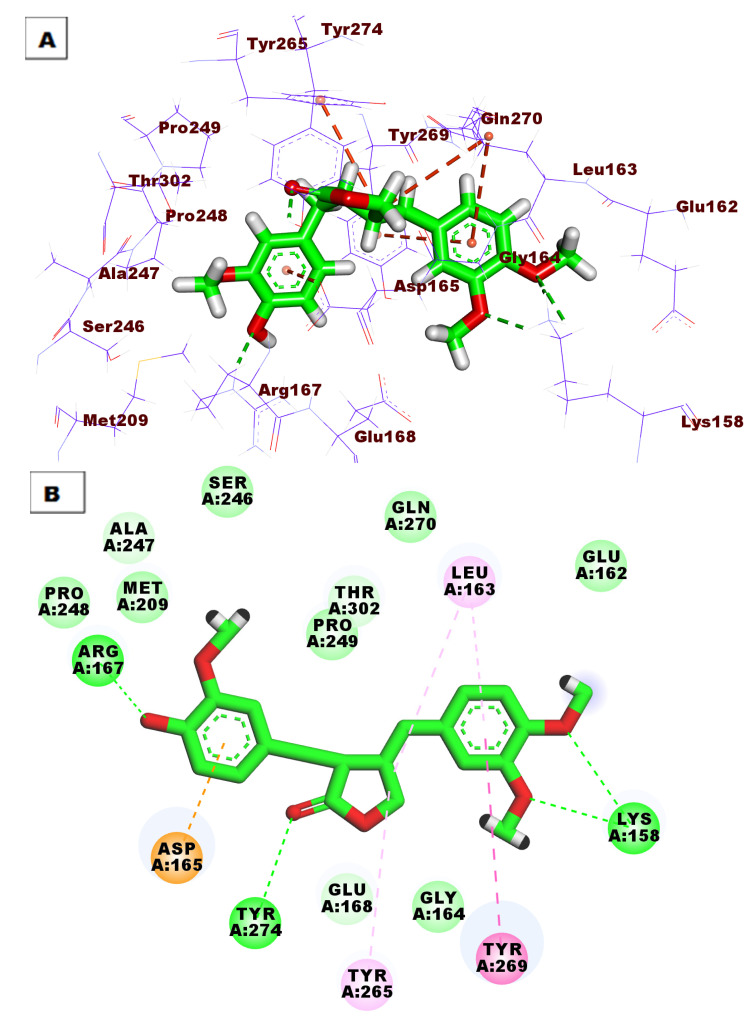

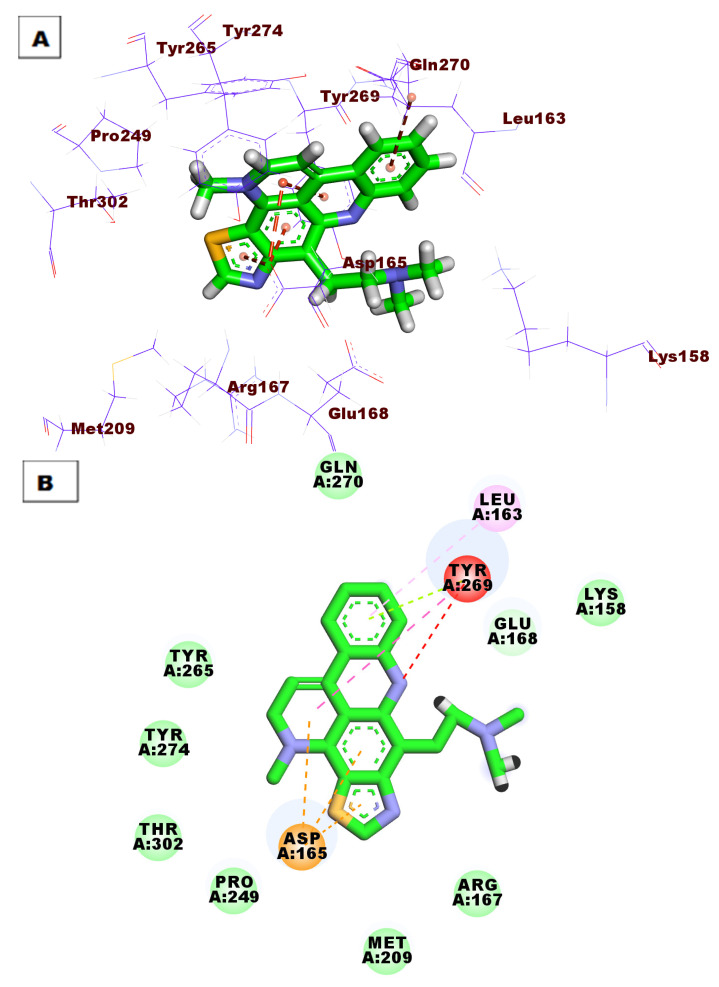

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of S88 in the active site of PLpro. As shown in Figure 6, compound 76 expressed a ΔG of −51.63 into the PLpro active site. Compound 76 made four HBs with Tyr265, Thr302, Tyr274, and Gln270. Moreover, the aromatic systems were included in many HIs with Asp165, Pro249, Tyr265, Gly164, Leu163, and Tyr269.

Figure 6.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 76 in the PLpro active site.

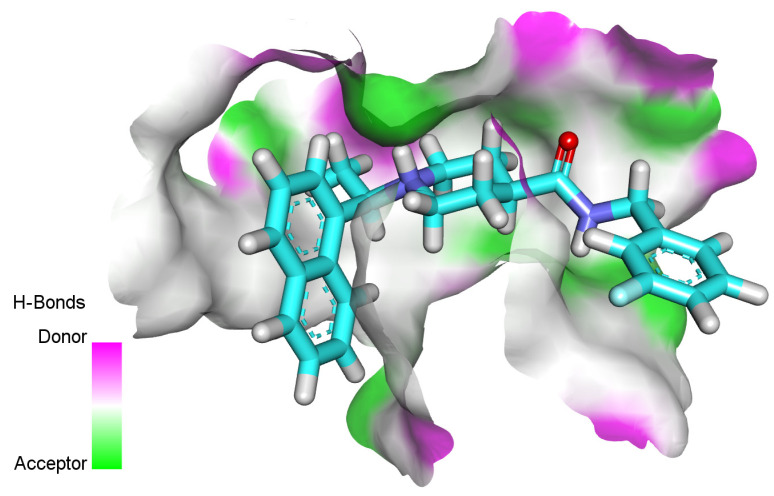

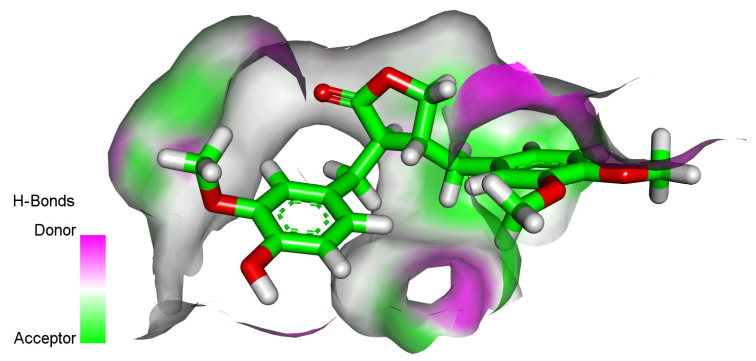

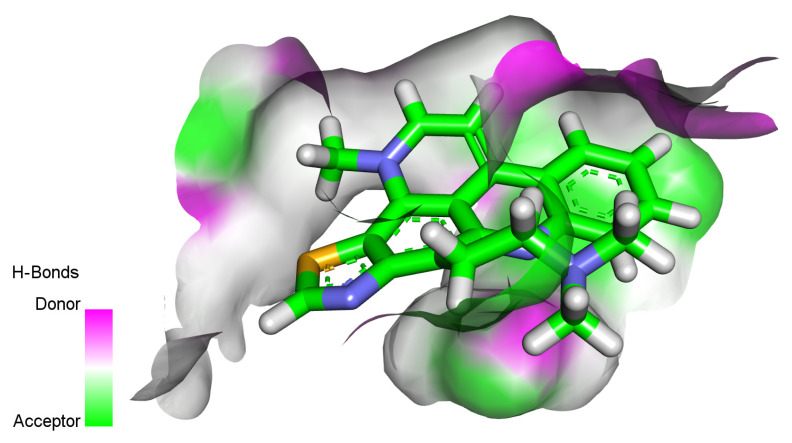

Compound 94 showed good binding energy (ΔG = −50.82) against the PLpro active site. It formed four HBs with Lys158, Tyr274, and Arg167. Additionally, the phenyl rings were involved in five HIs with Leu163, Tyr269, Tyr265, and Asp165 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 94 in the PLpro active site.

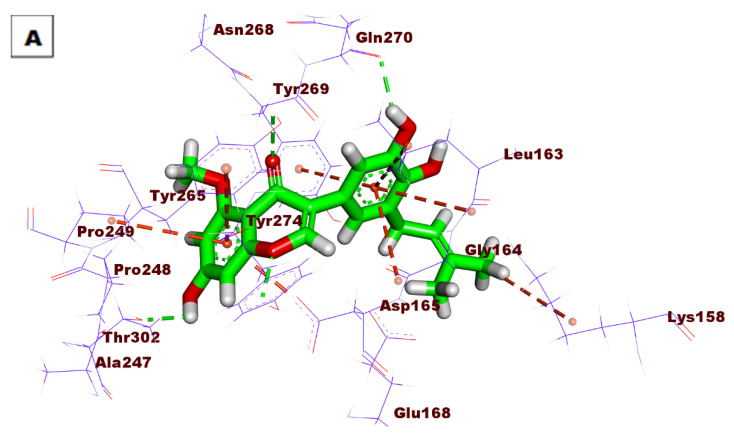

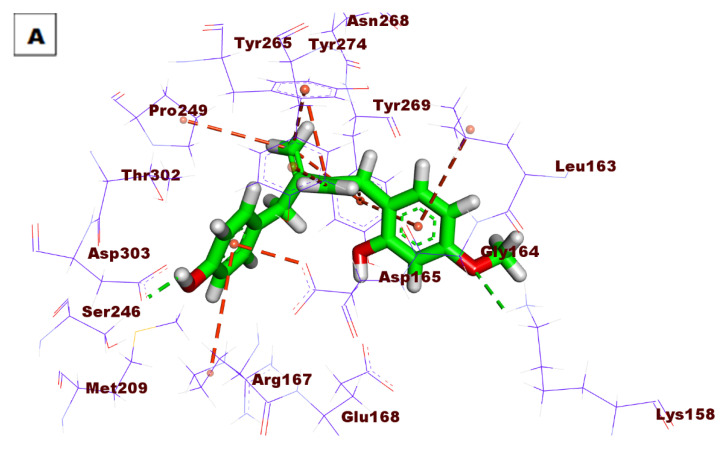

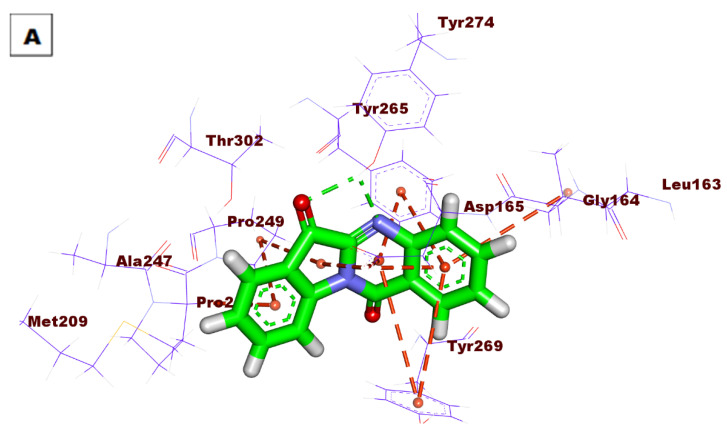

Compound 98 revealed good fitting with a docking score of −52.21 kcal/mol. The OH group formed one HB with Asp303, and the methoxy group formed another HB with Lys158. Many HIs were observed between the tested compound and Asp165, Arg167, Pro249, Tyr269, Tyr265, Leu163, and Tyr274 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 98 in the PLpro active site.

The top docking poses of compounds 193 and 200 (affinity values of −44.02 and −41.31 kcal/mol), respectively, were investigated. Compound 193 demonstrated eight HIs with Leu163, Tyr269, and Asp165 (Figure 9). The compound demonstrated two HBs with Tyr274. In addition, it formed 12 HIs, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 193 in the PLpro active site.

Figure 10.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 200 in the PLpro active site.

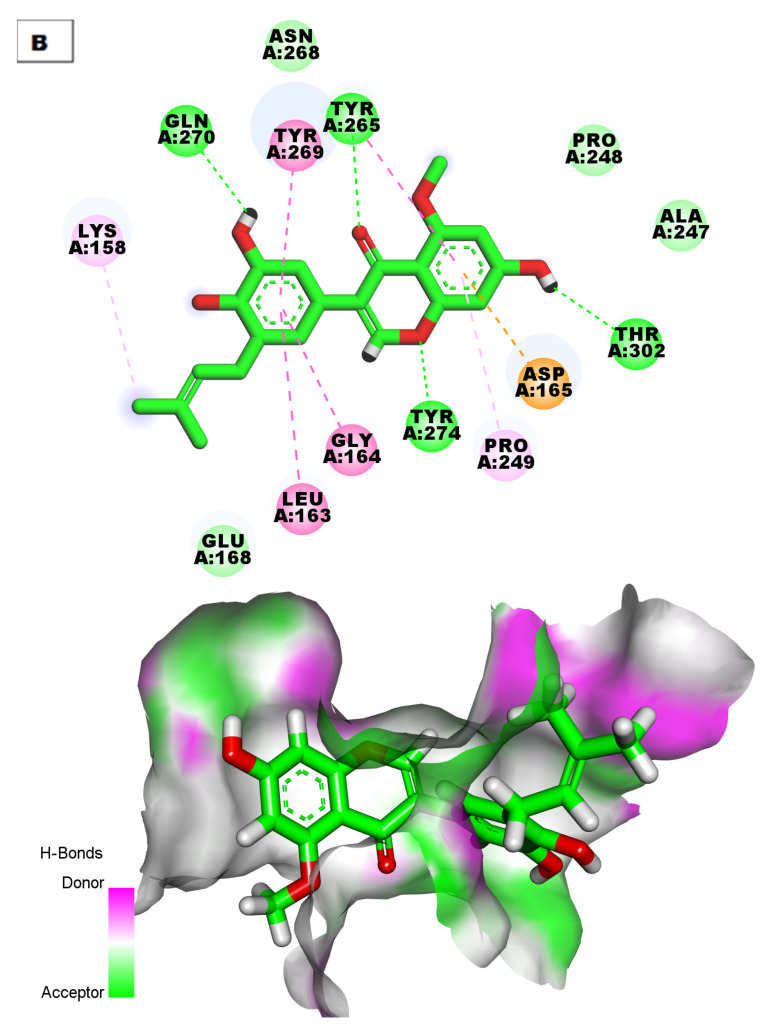

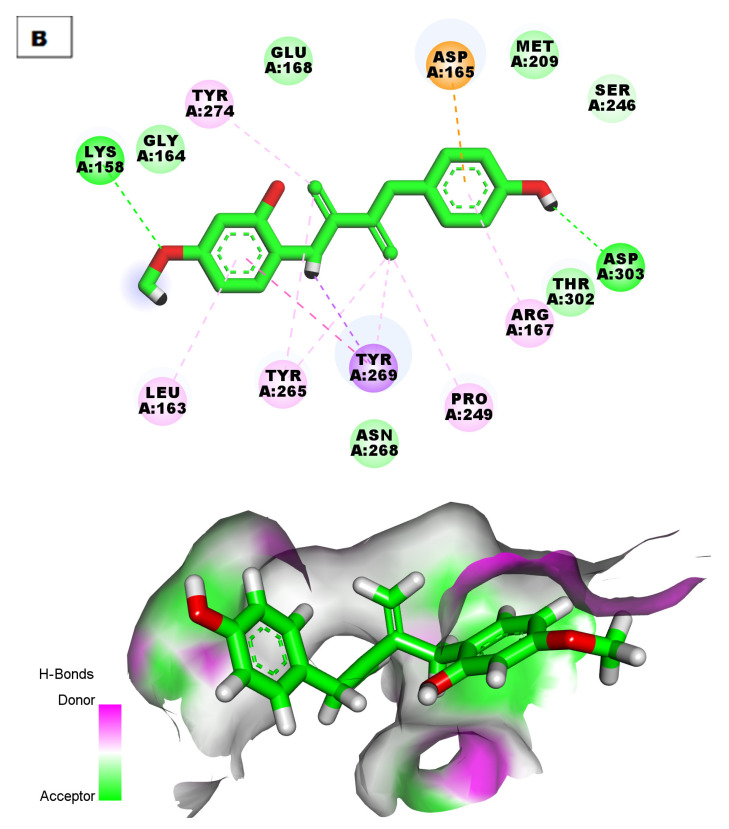

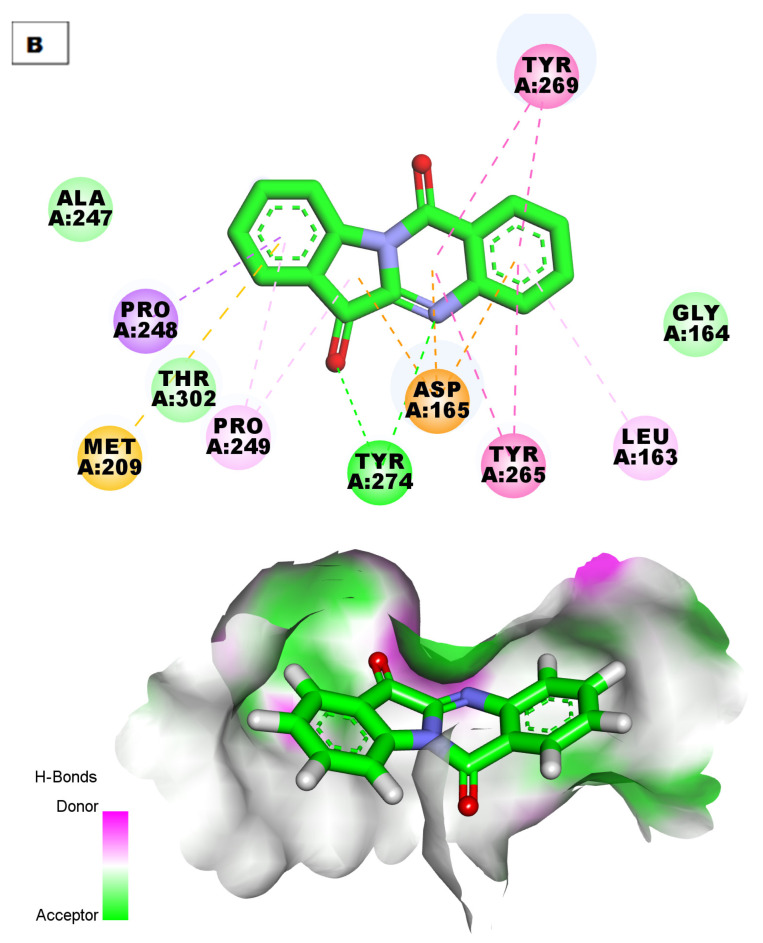

Compound 298 showed a binding mode against the PLpro active site with a binding affinity of −48.46 kcal/mol. It was incorporated in eight HIs with Pro248, Tyr265, Leu163, Tyr269, and Pro249 (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

(A) Three-dimensional and (B) two-dimensional binding modes of compound 298 in the PLpro active site.

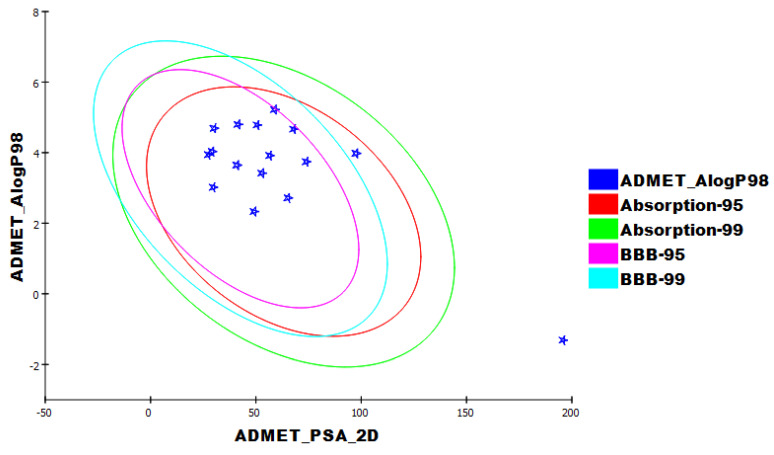

2.4. ADMET

ADMET studies were achieved using Discovery Studio 4.0, with remdesivir as a reference. The following descriptors were examined. (i) The ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier [48] (BBB), intestinal absorption [49] (HIA), aqueous solubility [50] (S), CYP2D6 binding [51], hepatotoxicity, and plasma protein binding [52] (PPB). The calculated properties are listed in (Table 4). All compounds showed high levels of BBB penetration except molecules 28, 76, 94, 200, and 298, which displayed medium to very low BBB levels. All the tested molecules showed good absorption characteristics comparable to remdesivir, which exhibited a very low level of absorption. Moreover, the solubility of the tested molecules was projected to be between low and good levels except for molecule 211, which showed a very low level. All molecules in addition to remdesivir were calculated to be inhibitors against CYP2D6 except molecules 28, 87, 94, 98, 99, 192, 200, 298 and 300. All the tested molecules were expected to have unfavorable hepatotoxic effects except molecules 28, 41, and 192, which were predicted to be non-toxic. All tested molecules and remdesivir were expected to bind to the plasma protein with a percentage of >90%, except molecule 46, which demonstrated plasma protein binding <90%. (Figure 12).

Table 4.

Predicted ADMET descriptors for the examined molecules and remdesivir.

| Comp. | BBB a | HIA b | Aq c | CYP2D6 d | Hepatotoxicity Probability e | PPB f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | c | a | d | n | 0.298 | c |

| 41 | b | a | c | i | 0.39 | b |

| 46 | b | a | c | i | 0.907 | a |

| 47 | b | a | c | i | 0.966 | c |

| 76 | e | a | c | i | 0.894 | b |

| 87 | b | a | c | n | 0.735 | b |

| 94 | c | a | c | n | 0.774 | c |

| 98 | b | a | c | n | 0.834 | c |

| 99 | b | a | c | n | 0.847 | c |

| 192 | b | a | c | n | 0.152 | c |

| 193 | b | a | c | i | 0.814 | c |

| 200 | c | a | c | n | 0.98 | c |

| 211 | b | a | b | i | 0.874 | c |

| 298 | c | a | c | n | 0.549 | c |

| 300 | b | a | c | n | 0.622 | c |

| Remdesivir | e | d | d | n | 1.777 | b |

a BBB level, b is high, c is medium, d is low, e is very low. b HIA, a is good, b is moderate, c is poor, d is very poor. c Aq. solubility level, a is extremely low, b is very low, c is low, d is good, e is optimal. d CYP2D6, n is a non-inhibitor, i is an inhibitor. e Hepatotoxicity, if >0.5 is toxic, if <0.5 is non-toxic. f PPBb is >90%, c is >95%.

Figure 12.

The expected ADMET characters.

2.5. Toxicity Studies

Toxicity predictions were made using Discovery Studio 4.0 software, which was based on validated and assembled models for the following parameters: the FDA rat carcinogenicity test [53,54], carcinogenic potentiality TD50 [55], maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in rats [56,57], oral LD50 in rats [58], chronic LOAEL in rats [59,60], ocular [61], and skin irritancies [61,62].

In silico testing revealed that the majority of molecules had expected low levels of toxicity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Toxicity properties of tested molecules and remdesivir.

| Comp. | FDA * Rat Carcinogenicity | TD50 (Rat) mg/kg Body Weight/Day |

MTD * | LD50 * | LOAEL * | Ocular Irritancy *** | Skin Irritancy *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | s | 9.571 | 0.050 | 0.939 | 0.077 | m | m |

| 41 | n | 0.219 | 0.042 | 0.202 | 0.018 | m | n |

| 46 | n | 0.730 | 0.081 | 1.248 | 0.009 | m | n |

| 47 | n | 0.169 | 0.035 | 1.446 | 0.008 | m | n |

| 76 | n | 19.216 | 0.153 | 0.362 | 0.150 | m | n |

| 87 | n | 48.173 | 0.113 | 0.364 | 0.030 | n | n |

| 94 | n | 8.907 | 0.091 | 9.209 | 0.107 | m | m |

| 98 | n | 35.370 | 0.103 | 1.133 | 0.398 | n | n |

| 99 | m | 69.077 | 0.240 | 2.040 | 0.301 | m | n |

| 192 | n | 0.857 | 1.099 | 0.348 | 0.016 | m | n |

| 193 | s | 1.587 | 0.012 | 0.352 | 0.048 | m | m |

| 200 | s | 7.568 | 0.055 | 0.689 | 0.277 | m | n |

| 211 | s | 0.604 | 0.013 | 0.245 | 0.001 | m | m |

| 298 | n | 65.542 | 0.018 | 0.118 | 0.019 | m | n |

| 300 | s | 13.502 | 0.029 | 0.405 | 0.029 | n | m |

| Remdesivir | n | 1.012 | 0.235 | 0.309 | 0.003 | m | m |

* s is single-carcinogen, m is multi-carcinogen n is non-carcinogen. *** n is nonirritant, m is mild irritant.

All compounds were expected to be non-carcinogens except molecules 28, 99, 193, 200, 211, and 300, which were predicted to be carcinogens in the FDA rat carcinogenicity model.

Molecules 41, 46, 47, 192, and 211 showed TD50 values within range of (0.16 to 0.730 mg·kg−1/day), which were less than remdesivir (1.012 mg·kg−1/day), while molecules 28, 76, 87, 94, 98, 99, 193, 200, 298, and 300 showed TD50 values within the range of (1.58 to 69.07 mg·kg−1/day), which were higher than remdesivir.

All molecules revealed an MTD within the range of 0.012 to 0.113 g·kg−1, less than remdesivir (0.235 g·kg−1), except molecules 99 and 192, which demonstrated MTD of 0.240 and 1.099 g·kg−1, respectively, which are higher than remdesivir.

All molecules showed oral LD50 values higher than remdesivir (0.309 mg·kg−1/day) except compounds 41, 211, and 298, which exhibited oral LD50 values less than remdesivir ranging from 0.118 to 0.245 mg·kg−1/day.

Excluding compound 211, all the tested molecules showed LOAEL higher than that of remdesivir (0.003 g·kg−1), ranging from 0.008 to 0.398 g·kg−1.

Additionally, all molecules and remdesivir were expected to be mild ocular irritants, except molecules 87, 98, and 300, which were non-irritant. On the other hand, the examined molecules were expected to be skin non-irritant except for molecules 28, 94, 193, 211, 300, and remdesivir, which were mild irritants.

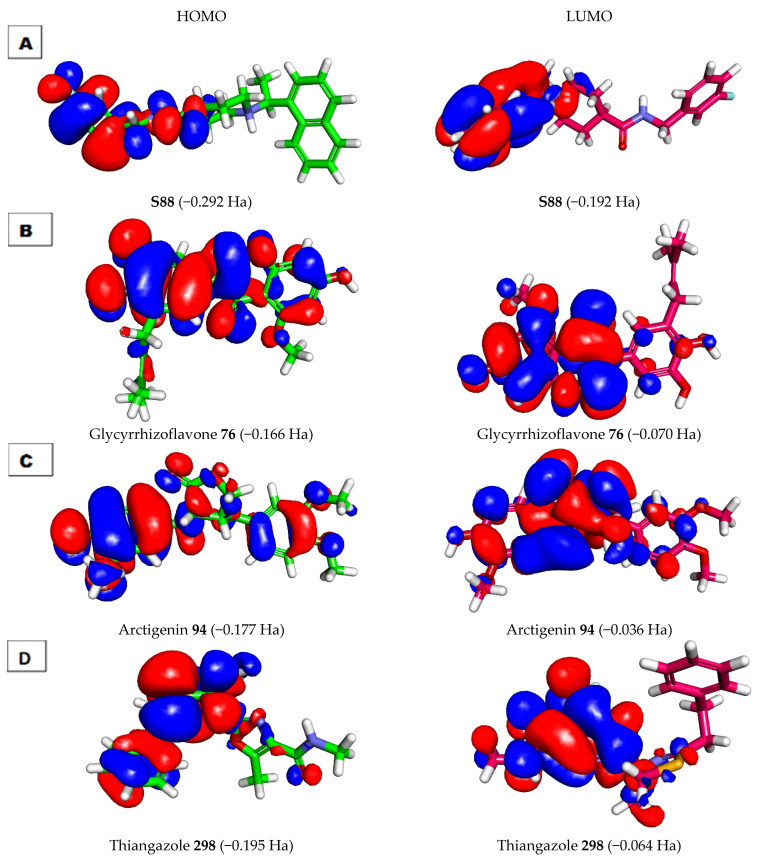

2.6. DFT Studies

DFT parameters including binding energy [63], HOMO [64], LUMO [64], gap energy [65], and dipole moment [66,67] were studied for the most promising molecules, 76, 94, and 298, using Discovery Studio software. S88 was used as a reference. The results of the DFT studies are summarized in Table 6 and Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Table 6.

Frontier molecular orbital of 76, 94, 298, and S88.

| Comp. | Total Energy (Ha) | Binding Energy (Ha) | HOMO Energy (Ha) | LUMO Energy (Ha) | Dipole Mag | Band Gap Energy (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | −1252.956 | −9.601 | −0.166 | −0.070 | 1.700 | 0.096 |

| 94 | −1255.298 | −10.037 | −0.177 | −0.036 | 3.582 | 0.141 |

| 298 | −1401.286 | −8.702 | −0.195 | −0.064 | 1.094 | 0.131 |

| S88 | −1242.952 | −11.181 | −0.292 | −0.192 | 3.621 | 0.101 |

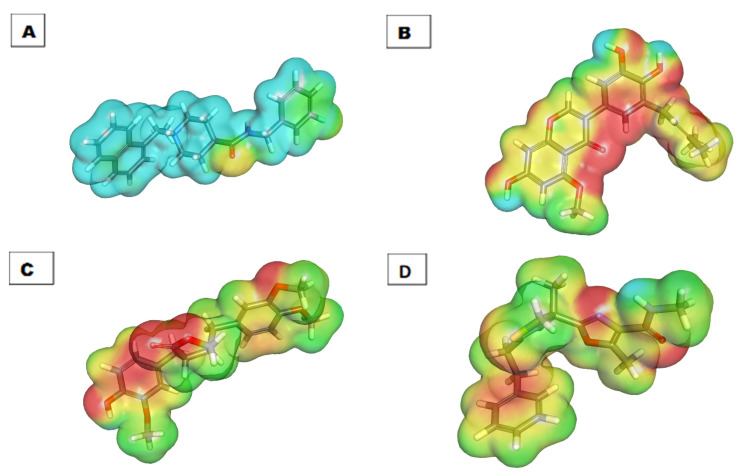

Figure 13.

Molecular orbitals spatial distribution for (A) S88, (B) 76, (C) 94, and (D) 298.

Figure 14.

Molecular electrostatic potential map of (A) S88, (B) 76, (C) 94, and (D) 298.

Molecules 76 and 94 showed higher values of dipole moment (1.700 and 3.582, respectively) than molecule 298 (1.094).

2.6.1. Frontier Molecular Orbitals Analysis

Frontier molecular orbitals analysis can efficiently demonstrate active sites in addition to determining the kinetic stability and the chemical reactivity of a molecule [68]. The EHOMO and ELUMO of the tested molecules were computed using DMol3 implemented in Discovery Studio software [69]. The LUMO may be engaged in a nucleophilic attack, while the HOMO refers to the most probable site of an electrophilic attack. The HOMO energy represents the ionization potential of a drug, while that of the LUMO describes the electron affinity.

For gap energy, it was reported that a molecule is thought to be softer and more chemically reactive when its energy gap is small. In addition, a molecule was assumed to have greater chemical hardness and to be more stable when it had a large energy gap [70]. In this study, molecule 76 was found to have a low level of gap energy of 0.096 Ha, while molecules 94 and 298 were found to have high gap energy of 0.141 and 0.131, respectively. These findings indicate that compound 76 has higher reactivity than compounds 94 and 298. On the contrary, compounds 94 and 298 may possess higher stability than compound 76.

For the dipole moment values, compound 94 had a dipole moment value of 3.582. This value is nearly equal to that of S88 (3.621). The elevated dipole moment was expected to increase HBing, and non-bonded interactions in the compound–protein complexes were predicted to increase the binding affinity during SARS-CoV-2 inhibition. Compounds 76 and 298 had fewer values of the dipole moment of 1.700 and 1.094, respectively. From these findings, it can be concluded that compounds 76 and 94 have a higher chance of interacting with the target protein than compound 298 (Table 6 and Figure 13).

As shown in Figure 13B, the HOMO spatial distributions of molecule 76 were mainly distributed on the 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) -7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one moiety, while those of LUMO were located on the 7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one moiety (the electron acceptor zones).

The specific role of the HOMO center (3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) -7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one moiety) in the binding of the receptor was previously confirmed by our docking experiments. As we noticed in Figure 13, the carbonyl group at position-4 of 4H-chromen-4-one (HOMO center) formed an H-bond acceptor with the phenolic OH group (LUMO center) of Tyr229. Furthermore, the LUMO of the accepting species (the two phenolic OH groups of catechol moiety) formed two H-bond donors with the HOMO of the donating species (OH group of Thr302 and OH group of Tyr274).

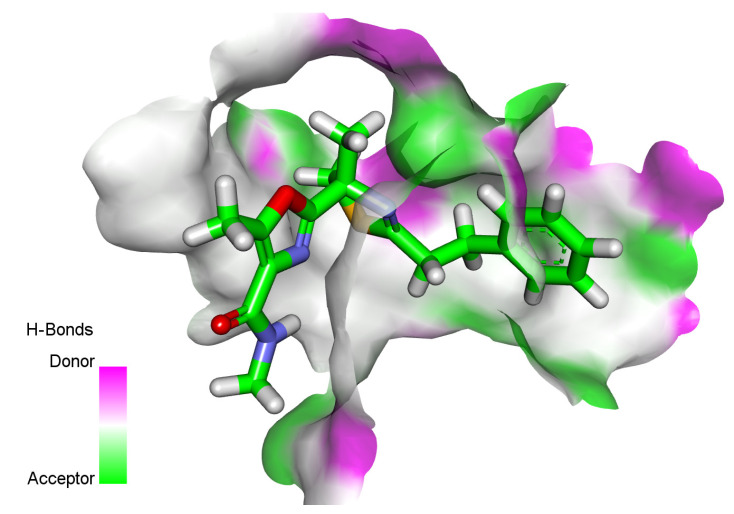

2.6.2. Molecular Electrostatic Potential Maps (MEP)

MEP is a very helpful technique for understanding the 3D charge distributions over a molecule.

In MEP, the electronegative atoms are highlighted with red and can be acceptors in H-bonding interactions. On the other hand, the electron-poor atoms are highlighted in blue and are incorporated into H-bonds as donors. Finally, the neutral atoms are highlighted from green to yellow and incorporated in HIs [71].

The MEP map of molecule 76 shows that the negative potential sites are on oxygen atoms (seven red patches) and the positive potential sites are around the hydrogen atoms (six blue patches). This indicates that molecule 76 has seven positions available for H-bonding acceptors and six positions suitable for H-bond donors. This map defines the region in which the molecule can have non-covalent interactions (Figure 14).

The presented study preferred glycyrrhizoflavone (76) as the most relevant inhibitor of human coronavirus PLpro. Glycyrrhizoflavone is a flavonoid that has been isolated from licorice and Glycyrrhiza glabra roots [72]. Glycyrrhisoflavone exhibited potent antiviral activity against the human immunodeficiency virus by inhibiting giant cell formation in the infected cells and inhibiting viral transcription [73,74].

3. Conclusions

Several computational filtration methods (similarity assessment, fingerprints check, docking, ADMET, toxicity, and DFT) were carried out on 310 metabolites of natural origin that were reported as antivirals against PLpro, (PDB ID: 4OW0) and its co-crystallized ligand S88. The experiments predicted a high degree of binding between glycyrrhizoflavone (76) and PLpro. Accordingly, the potential of glycyrrhizoflavone to be an inhibitor against human coronavirus PLpro inhibitor is highly expected. More studies must be carried out on such a promising drug to affirm its inhibitory potential against PLpro.

4. Method

4.1. Molecular Similarity Detection

Was applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail in the Supplementary data.

4.2. Fingerprint Studies

Were applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail in the Supplementary data.

4.3. Docking Studies

Were applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail in the Supplementary data.

4.4. ADMET Analysis

Was applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail in the Supplementary data.

4.5. Toxicity Studies

Were applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail in the Supplementary data.

4.6. DFT Studies

Were applied using Discovery Studio 4.0 software. Details have been discussed in detail the Supplementary data.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Research Center at AlMaarefa University for funding this work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/life12091407/s1. Chemical structures, names, molecular formulas of the examined compounds, detailed methodology and toxicity reports.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.H.E. and A.M.M.; Funding acquisition, A.A.A. and E.B.E.: Software, I.H.E., M.S.A., and A.M.S.; Writing—review & editing, all authors revised the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are enclosed in the manuscript and supplementary data.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest to be declared.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R116), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Engel T. Basic overview of chemoinformatics. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling. 2006;46:2267–2277. doi: 10.1021/ci600234z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu J., Hagler A. Chemoinformatics and drug discovery. Molecules. 2002;7:566–600. doi: 10.3390/70800566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalmakhanbetova R.I., Suleimen Y.M., Oyama M., Elkaeed E.B., Eissa I., Suleimen R.N., Metwaly A.M., Ishmuratova M.Y. Isolation and In Silico Anti-COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) Activities of Flavonoids and a Sesquiterpene Lactone from Artemisia sublessingiana. J. Chem. 2021;2021:5547013. doi: 10.1155/2021/5547013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koshak A.E., Koshak E.A. Nigella sativa L. as a potential phytotherapy for covid-19: A mini-review of in-silico studies. Curr. Ther. Res. 2020;93:100602. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2020.100602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu S., Ramaiah S., Anbarasu A. In-silico strategies to combat COVID-19: A comprehensive review. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2021;37:64–81. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2021.1966920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo Y.-C., Rensi S.E., Torng W., Altman R.B. Machine learning in chemoinformatics and drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2018;23:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W., Pei J., Lai L. Computational multitarget drug design. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling. 2017;57:403–412. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youssef M.I., Zhou Y., Eissa I.H., Wang Y., Zhang J., Jiang L., Hu W., Qi J., Chen Z. Tetradecyl 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate alleviates oligodendrocyte damage following chronic cerebral hypoperfusion through IGF-1 receptor. Neurochem. Int. 2020;138:104749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kairys V., Baranauskiene L., Kazlauskiene M., Matulis D., Kazlauskas E. Binding affinity in drug design: Experimental and computational techniques. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019;14:755–768. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2019.1623202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Warhi T., El Kerdawy A.M., Aljaeed N., Ismael O.E., Ayyad R.R., Eldehna W.M., Abdel-Aziz H.A., Al-Ansary G.H. Synthesis, biological evaluation and in silico studies of certain oxindole–indole conjugates as anticancer CDK inhibitors. Molecules. 2020;25:2031. doi: 10.3390/molecules25092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma A.K., Srivastava G.N., Roy A., Sharma V.K. ToxiM: A toxicity prediction tool for small molecules developed using machine learning and chemoinformatics approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:880. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speck-Planche A., Cordeiro M.J.D.S. Simultaneous virtual prediction of anti-Escherichia coli activities and ADMET profiles: A chemoinformatic complementary approach for high-throughput screening. ACS Comb. Sci. 2014;16:78–84. doi: 10.1021/co400115s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flores-Holguín N., Frau J., Glossman-Mitnik D. Conceptual DFT as a chemoinformatics tool for the study of the Taltobulin anticancer peptide. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:442. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metwaly A.M., Ghoneim M.M., Eissa I.H., Elsehemy I.A., Mostafa A.E., Hegazy M.M., Afifi W.M., Dou D. Traditional ancient Egyptian medicine: A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28:5823–5832. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X., Yang Y., Metwaly A.M., Xue Y., Shi Y., Dou D. The Chinese herbal formulae (Yitangkang) exerts an antidiabetic effect through the regulation of substance metabolism and energy metabolism in type 2 diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019;239:111942. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghildiyal R., Prakash V., Chaudhary V., Gupta V., Gabrani R. Plant-Derived Bioactives. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2020. Phytochemicals as antiviral agents: Recent updates; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Sayed K.A. Natural products as antiviral agents. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2000;24:473–572. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzair B., Mahmood Z., Tabassum S. Antiviral activity of natural products extracted from marine organisms. BioImpacts. 2011;1:203. doi: 10.5681/bi.2011.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen L., Laird K., Shivkumar M. Antiviral plant-derived natural products to combat RNA viruses: Targets throughout the viral life cycle. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/lam.13637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin D., Mukherjee R., Grewe D., Bojkova D., Baek K., Bhattacharya A., Schulz L., Widera M., Mehdipour A.R., Tascher G., et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature. 2020;587:657–662. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Báez-Santos Y.M., John S.E.S., Mesecar A.D. The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: Structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds. Antivir. Res. 2015;115:21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alesawy M.S., Abdallah A.E., Taghour M.S., Elkaeed E.B., Eissa I.H., Metwaly A.M. In Silico Studies of Some Isoflavonoids as Potential Candidates against COVID-19 Targeting Human ACE2 (hACE2) and Viral Main Protease (Mpro) Molecules. 2021;26:2806. doi: 10.3390/molecules26092806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Demerdash A., Metwaly A.M., Hassan A., El-Aziz A., Mohamed T., Elkaeed E.B., Eissa I.H., Arafa R.K., Stockand J.D. Comprehensive virtual screening of the antiviral potentialities of marine polycyclic guanidine alkaloids against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Biomolecules. 2021;11:460. doi: 10.3390/biom11030460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eissa I.H., Khalifa M.M., Elkaeed E.B., Hafez E.E., Alsfouk A.A., Metwaly A.M. In Silico Exploration of Potential Natural Inhibitors against SARS-Cov-2 nsp10. Molecules. 2021;26:6151. doi: 10.3390/molecules26206151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alesawy M.S., Elkaeed E.B., Alsfouk A.A., Metwaly A.M., Eissa I. In Silico Screening of Semi-Synthesized Compounds as Potential Inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Papain-Like Protease: Pharmacophoric Features, Molecular Docking, ADMET, Toxicity and DFT Studies. Molecules. 2021;26:6593. doi: 10.3390/molecules26216593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eissa I.H., Alesawy M.S., Saleh A.M., Elkaeed E.B., Alsfouk B.A., El-Attar A.-A.M., Metwaly A.M. Ligand and structure-based in silico determination of the most promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase complex inhibitors among 3009 FDA approved drugs. Molecules. 2022;27:2287. doi: 10.3390/molecules27072287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkaeed E.B., Eissa I.H., Elkady H., Abdelalim A., Alqaisi A.M., Alsfouk A.A., Elwan A., Metwaly A.M. A Multistage In Silico Study of Natural Potential Inhibitors Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:8407. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elkaeed E.B., Youssef F.S., Eissa I.H., Elkady H., Alsfouk A.A., Ashour M.L., El Hassab M.A., Abou-Seri S.M., Metwaly A.M. Multi-step in silico discovery of natural drugs against COVID-19 targeting main protease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:6912. doi: 10.3390/ijms23136912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elkaeed E.B., Elkady H., Belal A., Alsfouk B.A., Ibrahim T.H., Abdelmoaty M., Arafa R.K., Metwaly A.M., Eissa I.H. Multi-Phase In Silico Discovery of Potential SARS-CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Inhibitors among 3009 Clinical and FDA-Approved Related Drugs. Processes. 2022;10:530. doi: 10.3390/pr10030530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altamash T., Amhamed A., Aparicio S., Atilhan M. Effect of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors on CO2 absorption by deep eutectic solvents. Processes. 2020;8:1533. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan Y., Tian Y., Wang W., Gu S., Ju X., Liu G. In silico studies of diarylpyridine derivatives as novel HIV-1 NNRTIs using docking-based 3D-QSAR, molecular dynamics, and pharmacophore modeling approaches. RSC Adv. 2018;8:40529–40543. doi: 10.1039/C8RA06475J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turchi M., Cai Q., Lian G. An evaluation of in-silico methods for predicting solute partition in multiphase complex fluids–A case study of octanol/water partition coefficient. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019;197:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2018.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan K.M., Enoch S.J., Ezendam J., Sewald K., Roggen E.L., Cochrane S. An adverse outcome pathway for sensitization of the respiratory tract by low-molecular-weight chemicals: Building evidence to support the utility of in vitro and in silico methods in a regulatory context. Appl. Vitr. Toxicol. 2017;3:213–226. doi: 10.1089/aivt.2017.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escamilla-Gutiérrez A., Ribas-Aparicio R.M., Córdova-Espinoza M.G., Castelán-Vega J.A. In silico strategies for modeling RNA aptamers and predicting binding sites of their molecular targets. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2021;40:798–807. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2021.1951754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaushik A.C., Kumar A., Bharadwaj S., Chaudhary R., Sahi S. Bioinformatics Techniques for Drug Discovery. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2018. Ligand-Based Approach for In-silico Drug Designing; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H., Ren J.-X., Ma J.-X., Ding L. Development of an in silico prediction model for chemical-induced urinary tract toxicity by using naïve Bayes classifier. Mol. Divers. 2019;23:381–392. doi: 10.1007/s11030-018-9882-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke B.J. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center; Chicago, IL, USA: 1993. Developments in Molecular Shape Analysis to Establish Spatial Similarity among Flexible Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briem H., Kuntz I.D. Molecular similarity based on DOCK-generated fingerprints. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:3401–3408. doi: 10.1021/jm950800y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu H., He Q.-X., Wang J., Hu Y., Wang Y.-Q., Lin Z.-H. In silico design of novel benzohydroxamate-based compounds as inhibitors of histone deacetylase 6 based on 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. New J. Chem. 2020;44:21201–21210. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ04704J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ieritano C., Campbell J.L., Hopkins W.S. Predicting differential ion mobility behaviour in silico using machine learning. Analyst. 2021;146:4737–4743. doi: 10.1039/D1AN00557J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taha M., Ismail N.H., Ali M., Rashid U., Imran S., Uddin N., Khan K.M. Molecular hybridization conceded exceptionally potent quinolinyl-oxadiazole hybrids through phenyl linked thiosemicarbazide antileishmanial scaffolds: In silico validation and SAR studies. Bioorganic Chem. 2017;71:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opo F.A.D.M., Rahman M.M., Ahammad F., Ahmed I., Bhuiyan M.A., Asiri A.M. Structure based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking and ADMET approaches for identification of natural anti-cancer agents targeting XIAP protein. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4049. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J., Morin P., Wang W., Kollman P.A. Use of MM-PBSA in reproducing the binding free energies to HIV-1 RT of TIBO derivatives and predicting the binding mode to HIV-1 RT of efavirenz by docking and MM-PBSA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5221–5230. doi: 10.1021/ja003834q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houston D.R., Walkinshaw M.D. Consensus docking: Improving the reliability of docking in a virtual screening context. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling. 2013;53:384–390. doi: 10.1021/ci300399w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson D., Cox M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 5th ed. WH Freeman and Company; New York, NY, USA: 2008. G protein-coupled receptors and second messengers; pp. 423–439. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malau N.D., Azzahra S.F. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing; Bristol, UK: 2020. Molecular Docking Studies of Potential Quercetin 3,4′-dimethyl ether 7-alpha-LArabinofuranosyl-(1-6)-glucoside as Inhibitor antimalaria; p. 012057. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel H., Dhangar K., Sonawane Y., Surana S., Karpoormath R., Thapliyal N., Shaikh M., Noolvi M., Jagtap R. In search of selective 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitors without nephrotoxicity: An approach to resolve the metabolic syndrome by virtual based screening. Arab. J. Chem. 2018;11:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mannhold R., Kubinyi H., Folkers G. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism in Drug Design. Volume 51 John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klopman G., Stefan L.R., Saiakhov R.D. ADME evaluation: 2. A computer model for the prediction of intestinal absorption in humans. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002;17:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(02)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roy P.P., Roy K. QSAR studies of CYP2D6 inhibitor aryloxypropanolamines using 2D and 3D descriptors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2009;73:442–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghafourian T., Amin Z. QSAR models for the prediction of plasma protein binding. BioImpacts BI. 2013;3:21. doi: 10.5681/bi.2013.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia X., Maliski E.G., Gallant P., Rogers D. Classification of kinase inhibitors using a Bayesian model. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:4463–4470. doi: 10.1021/jm0303195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.BIOVIA QSAR, ADMET and Predictive Toxicology. [(accessed on 1 May 2020)]. Available online: https://www.3dsbiovia.com/products/collaborative-science/biovia-discovery-studio/qsar-admet-and-predictive-toxicology.html.

- 55.Venkatapathy R., Wang N.C.Y., Martin T.M., Harten P.F., Young D. Structure–Activity Relationships for Carcinogenic Potential. Gen. Appl. Syst. Toxicol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/9780470744307.gat079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodrnan G., Wilson R. Comparison of the dependence of the TD50 on maximum tolerated dose for mutagens and nonmutagens. Risk Anal. 1992;12:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1992.tb00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Council N.R. Issues in Risk Assessment. National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC, USA: 1993. Correlation between Carcinogenic Potency and the Maximum Tolerated Dose: Implications for Risk Assessment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonella Diaza R., Manganelli S., Esposito A., Roncaglioni A., Manganaro A., Benfenati E. Comparison of in silico tools for evaluating rat oral acute toxicity. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2015;26:1–27. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2014.977819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pizzo F., Benfenati E. In Silico Methods for Predicting Drug Toxicity. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2016. In silico models for repeated-dose toxicity (RDT): Prediction of the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) and lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) for drugs; pp. 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Venkatapathy R., Moudgal C.J., Bruce R.M. Assessment of the oral rat chronic lowest observed adverse effect level model in TOPKAT, a QSAR software package for toxicity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004;44:1623–1629. doi: 10.1021/ci049903s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilhelmus K.R. The Draize eye test. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001;45:493–515. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdallah A.E., Alesawy M.S., Eissa S.I., El-Fakharany E.M., Kalaba M.H., Sharaf M.H., Abo Shama N.M., Mahmoud S.H., Mostafa A., Al-Karmalawy A.A., et al. Design and synthesis of new 4-(2-nitrophenoxy)benzamide derivatives as potential antiviral agents: Molecular modeling and in vitro antiviral screening. New J. Chem. 2021;45:16557–16571. doi: 10.1039/D1NJ02710G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Subashchandrabose S., Saleem H., Erdogdu Y., Rajarajan G., Thanikachalam V. FT-Raman, FT-IR spectra and total energy distribution of 3-pentyl-2,6-diphenylpiperidin-4-one: DFT method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011;82:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bazeera A.Z., Selvaraj S., Mohamed A.S. Spectroscopic analysis (Raman, FT-IR, UV, NMR), HUMO, LUMO and first order hyper polarizability calculations of Nor Leucine Maleate (DLNM) using DFT methods. Wutan Huatan Jisuan Jishu. 2020;16:266–277. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohammed H.S., Tripathi V.D., Darghouth A.A. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing; Bristol, UK: 2019. Synthesis, Characterization, DFT calculation and Antimicrobial Activity of Co (II) and Cu (II) complexes with azo dye; p. 052051. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fleming I. Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions. Wiley; New York, NY, USA: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Nahass M., Kamel M., El-Deeb A., Atta A., Huthaily S. Ab initio HF, DFT and experimental (FT-IR) investigation of vibrational spectroscopy of PN, N-dimethylaminobenzylidenemalononitrile (DBM) Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011;79:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parambil S.H.K., Parambil H.A.T., Hamza S.P., Parameswaran A.T., Thayyil M.S., Karuvanthodi M. Density Functional Theory Calculations. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2020. DFT and Molecular Docking Studies of a Set of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Propionic Acid Derivatives. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Discovery Studio . Accelrys. BIOVIA; San Diego, CA, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pegu D., Deb J., Van Alsenoy C., Sarkar U. Theoretical investigation of electronic, vibrational, and nonlinear optical properties of 4-fluoro-4-hydroxybenzophenone. Spectrosc. Lett. 2017;50:232–243. doi: 10.1080/00387010.2017.1308381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matin M.M., Hasan M.S., Uzzaman M., Bhuiyan M.M.H., Kibria S.M., Hossain M.E., Roshid M.H. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, molecular docking, and ADMET studies of mannopyranoside esters as antimicrobial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1222:128821. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hatano T., Eerdunbayaer C., Kuroda T., Shimozu Y. Biological Activities and Action Mechanisms of Licorice Ingredients. InTech; Rijeka, Croatia: 2017. Licorice as a resource for pharmacologically active phenolic substances: Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uchiumi F., Hatano T., Ito H., Yoshida T., Tanuma S.-I. Transcriptional suppression of the HIV promoter by natural compounds. Antivir. Res. 2003;58:89–98. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vlietinck A., De Bruyne T., Apers S., Pieters L. Plant-derived leading compounds for chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Planta Med. 1998;64:97–109. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are enclosed in the manuscript and supplementary data.