Abstract

Pulmonary embolism is a potentially lethal manifestation of venous thromboembolic disease. It is one of the three main causes of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in developed countries. Over the years, better diagnostic and risk stratification measures were implemented. A generous range of new treatment options is becoming available, particularly for management of massive pulmonary embolism. Nonetheless, clinicians often face uncertainty in clinical practice due to lack of scientific support for available treatment options. The aim of this article is to review management of massive pulmonary embolism.

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, massive pulmonary embolism, high-risk pulmonary embolism, reperfusion treatment, thrombolysis, embolectomy, ECMO

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening condition that is one of the three major causes of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the developed countries. 1 2 PE manifests with a wide severity scale, ranging from almost asymptomatic to lethal conditions. All-cause hospital mortality for massive PE ranges from 44 to 65%, depending on the study cited. 1 3 As majority of deaths occur during first hour of presentation an organized institution-specific approach within “golden hour” is advised. 4 An early classification based on risk stratification of patients with acute PE is obligatory for establishing therapeutic management. The mainstay of acute PE treatment is anticoagulation therapy. Patients with massive pulmonary embolism require advanced therapy for pulmonary artery reperfusion. Systemic thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy, and catheter directed therapy are the therapeutic options. In case of cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock refractory to standard treatment, mechanical hemodynamic support, such as venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO), should be initiated. Nowadays, creation of multidisciplinary Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) becomes a standard of care. 5 That stemmed from the need for establishing individually tailored care. The primary focus of this review is management of massive PE.

Definition of Massive Pulmonary Embolism

Acute PE is termed massive when associated with sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes or requiring inotropic support), pulselessness, or persistent profound bradycardia. 6 European guidelines classify acute PE as high risk when associated with hemodynamic instability, worse clinical parameters of severity, right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, and elevated cardiac troponin levels. 3

Primary Treatment Options for Massive Pulmonary Embolism

Anticoagulation

If clinical suspicion of acute PE is high, initiation of anticoagulation is recommended even before diagnosis confirmation. It is proven that early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality. 3 7 Anticoagulation impairs clot propagation and prevents recurrent PE. The choice of anticoagulant is dependent on clinical situation. In patients with hemodynamic instability when involvement of advanced therapies might be expected, intravenous unfractionated heparin is the preferred option, since it allows more flexibility. Moreover, in such situation, achieving therapeutic level of anticoagulation as soon as possible is crucial.

Respiratory Support

Oxygen supplementation should be initiated if oxygen saturation of the arterial blood is under 90%. 3 Hypoxemia is caused by mismatch between ventilation and perfusion and can be increased by right-to-left shunt. High-flow oxygen and mechanical ventilation should be considered. However, caution should be taken as mechanical ventilation induces positive intrathoracic pressure that can lower cardiac output due to right ventricular failure and reduced venous return. Inhaled nitric oxide may improve oxygenation and hemodynamics based on its selective pulmonary vasodilator activity and antiplatelet function. 8

Hemodynamic Management

Careful fluid management should be optimized by central venous pressure monitoring. Excess volume might be devastating, as right ventricle overload may impact ventricular interdependence and lower diastolic left ventricular filling reducing cardiac output. Moreover, it may increase free-wall tension resulting in elevated oxygen demand and decreased RV perfusion. 9 Use of vasopressors and inotropes, such as norepinephrine, dobutamine, levosimendan, and milrinone, is essential in cardiogenic shock. 10

Reperfusion Treatment

Systemic Thrombolysis

Management of massive PE requires implementation of advanced therapeutic options. The usual first choice of treatment escalation is systemic thrombolysis (ST). 11 ST leads to rapid resolution of embolic obstruction restoring pulmonary perfusion. Thrombolytic agents, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), alteplase, promise thrombus resolution within few hours. 12 13 There is an inverse relation between symptoms duration and response to ST treatment. Nevertheless, effect of ST can be observed even in patients who have symptoms for 6 to 14 days. 14 Recommended dose of t-PA is 100 mg over 2 hours. 3 A reduced-dose of 50 mg over 2 hours is suggested in patients with relative contraindication to ST. 5 In hemodynamic compromise, accelerated regimen of 0.6 mg/kg over 15 minutes may be used. 3

A huge disadvantage of ST is a significant increase in severe hemorrhagic complications of which intracranial bleeding is the most devastating. Large registry reported incidence of intracranial bleeding of 3%. 15

Surgical Embolectomy

Martin Kirschner performed first successful surgical pulmonary embolectomy in 1924 in Germany. 16 Since then, the mortality rate has changed and nowadays experienced centers report mortality rate of 11.6% for massive PE and 4.4% for high-risk submassive PE. 17 Another single-center study reports 1-year survival of 91%. 18 Current guidelines recommend surgical embolectomy in patients with high-risk and intermediate-risk PE with absolute contraindications to thrombolysis, failed thrombolysis, or cardiogenic shock that can lead to death before thrombolysis takes effect. 3 6 Reasonable indication for surgical embolectomy are central emboli, such as saddle PE, right atrial thrombus that are easily surgically accessed or need for foramen ovale closure. 19

Catheter Embolectomy

Several techniques are used for this purpose. Catheter-based thrombus maceration is performed with a modified pigtail catheter with a guide wire or peripheral balloons. This may establish forward flow in totally occluded proximal branches of pulmonary artery before thrombolysis takes effect. Only limited evidence is published and this technique is likely to become obsolete. Another option is rheolytic thrombectomy where a vacuum and thrombus fragmentation is created by backward saline currents. This method should not be used as initial treatment because of safety concerns. 20

Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis

Catheter-directed thrombolysis delivers low-dose thrombolytics directly into the pulmonary artery. The rationale is to lower the risk of major and intracranial bleeding by applying significantly lower dose of thrombolysis directly into the thrombus. Several regimes are reported, the dose of 24 mg over 24 hours seems to be the most common. In addition, an ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis system is available. 21 The hypothesis suggests that ultrasound waves separate fibrin and allow better penetration of the thrombolytic agent into the thrombus. 20 A randomized trial compering both methods was conducted, with similar pulmonary arterial thrombus reduction. 22 23

Mechanical Circulatory Support

Mechanical support should be considered in patients with acute PE and cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. VA ECMO provides effective hemodynamic support and oxygenation. Additionally, it reduces right ventricle distention. Several series of cases have been reported combining reperfusion and anticoagulation therapies in addition to VA ECMO with different survival rates. 24 25 26 The median duration of ECMO in this indication is reported to be between 4 to 6 days. 27 It provides time for right ventricle recovery. Suggested predictors of failure of recovery are respiratory symptoms >2 weeks, main pulmonary artery >3.4 cm, NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide) > 5,000 pg/mL and history of venous thromboembolism. 28

Several mechanical circulatory support devices for right ventricular failure are available but its use is limited to highly specialized centers. 29

Suggested Decision-Making Process

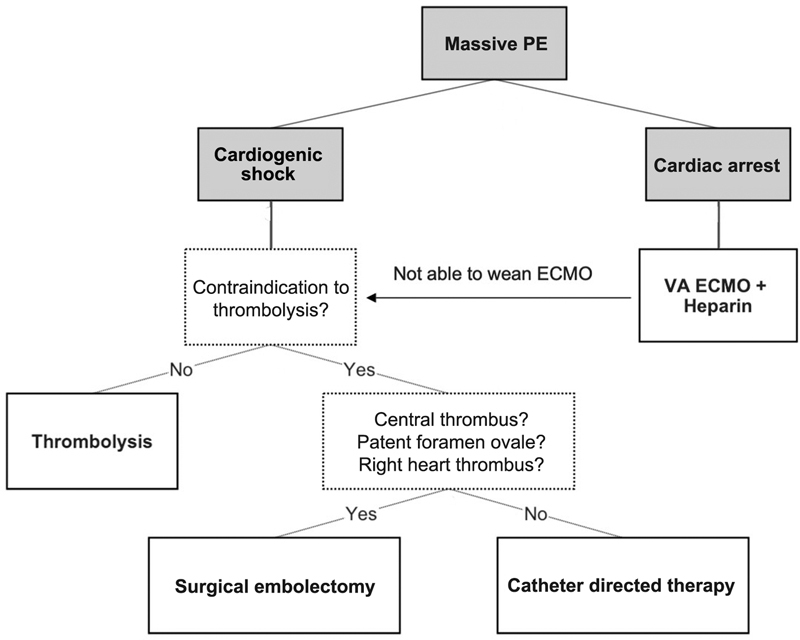

On the basis of the above-mentioned, we propose a decision tree depicting the simplified treatment strategy of massive PE ( Fig. 1 ). In cardiogenic shock, thrombolysis is a first-line treatment option. In case of contraindication to thrombolysis surgical embolectomy or catheter-directed therapy has to be performed. Furthermore, in case of cardiac arrest, implantation of VA ECMO should be considered. Given the lack of scientific support, creation of PERT is of absolute necessity. 30 First, it provides a prompt and considered decision on next management steps. Second, it produces a database for future evidence.

Fig. 1.

Simplified treatment strategy of massive PE. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PE, pulmonary embolism; VA ECMO, venoarterial ECMO.

Conclusion

Management of massive PE presents a challenge for clinicians since the evidence for treatment options is scarce and ambiguous. The main goal of massive PE treatment is to stabilize the patient in cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest and safely direct thrombus resolution. The use of reperfusion therapies is guided by the individual center experience. Since its expansion in recent decade, VA ECMO is used as bridging strategy in massive PE. There is an urgent need for further research to help clinicians better guide the treatment of massive PE.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Smith S B, Geske J B, Kathuria P. Analysis of national trends in admissions for pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2016;150(01):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raskob G E, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco A N. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(10):1580–1590. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ESC Scientific Document Group . Konstantinides S V, Meyer G, Becattini C. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41 04:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood K E.Major pulmonary embolism: review of a pathophysiologic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism Chest 2002121(3, suppl):877–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.PERT Consortium . Rivera-Lebron B, McDaniel M, Ahrar K. Diagnosis, treatment and follow up of acute pulmonary embolism: consensus practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019;25:1.076029619853037E15. doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation ; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease ; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology . Jaff M R, McMurtry M S, Archer S L. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(16):1788–1830. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith S B, Geske J B, Maguire J M, Zane N A, Carter R E, Morgenthaler T I. Early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2010;137(06):1382–1390. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat T, Neuman A, Tantary M. Inhaled nitric oxide in acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(01):1–8. doi: 10.3909/ricm0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventetuolo C E, Klinger J R. Management of acute right ventricular failure in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(05):811–822. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-446FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyhne M D, Dragsbaek S J, Hansen J V, Schultz J G, Andersen A, Nielsen-Kudsk J E.Levosimendan, milrinone, and dobutamine in experimental acute pulmonary embolismPulm Circ 2021;11(03):20458940211022977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Stevens S M, Woller S C, Kreuziger L B. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(06):e545–e608. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldhaber S Z, Haire W D, Feldstein M L.Alteplase versus heparin in acute pulmonary embolism: randomised trial assessing right-ventricular function and pulmonary perfusion Lancet 1993341(8844):507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konstantinides S, Tiede N, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Just H, Kasper W. Comparison of alteplase versus heparin for resolution of major pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(08):966–970. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00513-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels L B, Parker J A, Patel S R, Grodstein F, Goldhaber S Z. Relation of duration of symptoms with response to thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80(02):184–188. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tapson V F. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1037–1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFadden P M, Ochsner J L. Aggressive approach to pulmonary embolectomy for massive acute pulmonary embolism: a historical and contemporary perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(09):782–784. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg J B, Spevack D M, Ahsan S. Survival and right ventricular function after surgical management of acute pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(08):903–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasrija C, Kronfli A, Rouse M. Outcomes after surgical pulmonary embolectomy for acute submassive and massive pulmonary embolism: A single-center experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(03):1095–110600. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neely R C, Byrne J G, Gosev I. Surgical embolectomy for acute massive and submassive pulmonary embolism in a series of 115 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(04):1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giri J, Sista A K, Weinberg I. Interventional therapies for acute pulmonary embolism: current status and principles for the development of novel evidence: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2019;140(20):e774–e801. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teleb M, Porres-Aguilar M, Rivera-Lebron B. Ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis: a novel and promising endovascular therapeutic modality for intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Angiology. 2017;68(06):494–501. doi: 10.1177/0003319716665718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SUNSET sPE Collaborators . Avgerinos E D, Jaber W, Lacomis J. Randomized trial comparing standard versus ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis for submassive pulmonary embolism: the SUNSET sPE Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(12):1364–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sista A K. Is it time to sunset ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for submassive PE? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(12):1374–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. In-hospital mortality and successful weaning from venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of 5,263 patients using a national inpatient database in Japan. Crit Care. 2016;20(01):80. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusuff H O, Zochios V, Vuylsteke A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute massive pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Perfusion. 2015;30(08):611–616. doi: 10.1177/0267659115583377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meneveau N, Guillon B, Planquette B. Outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the treatment of high-risk pulmonary embolism: a multicentre series of 52 cases. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(47):4196–4204. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George B, Parazino M, Omar H R. A retrospective comparison of survivors and non-survivors of massive pulmonary embolism receiving veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Resuscitation. 2018;122:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghoreishi M, DiChiacchio L, Pasrija C. Predictors of recovery in patients supported with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute massive pulmonary embolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(01):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapur N K, Esposito M L, Bader Y. Mechanical circulatory support devices for acute right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2017;136(03):314–326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porres-Aguilar M, Anaya-Ayala J E, Jiménez D, Mukherjee D. Pulmonary embolism response teams: pursuing excellence in the care for venous thromboembolism. Arch Med Res. 2019;50(05):257–258. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]