SUMMARY

Malaria and leishmaniasis are among the two most important health problems of many developing countries especially in the Middle East and North Africa. It is common for vector-borne infectious diseases to have similar hotspots which may be attributed to the overlapping ecological distribution of the vector. Hotspot analyses were conducted to simultaneously detect the location of local hotspots and test their statistical significance. Spatial scan statistics were used to detect and test hotspots of malaria and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in Afghanistan in 2009. A multivariate negative binomial model was used to simultaneously assess the effects of environmental variables on malaria and CL. In addition to the dependency between malaria and CL disease counts, spatial and temporal information were also incorporated in the model. Results indicated that malaria and CL incidence peaked at the same periods. Two hotspots were detected for malaria and three for CL. The findings in the current study show an association between the incidence of malaria and CL in the studied areas of Afghanistan. The incidence of CL disease in a given month is linked with the incidence of malaria in the previous month. Co-existence of malaria and CL within the same geographical area was supported by this study, highlighting the presence and effects of environmental variables such as temperature and precipitation. People living in areas with malaria are at increased risk for leishmaniasis infection. Local healthcare authorities should consider the co-infection problem by recommending systematic malaria screening for all CL patients.

Key words: Co-infection, cutaneous leishmaniasis, malaria, negative binomial, overdispersion, spatio-temporal

INTRODUCTION

Malaria and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) are serious, vector-borne infectious diseases, both of which are caused by parasites and co-endemic in Afghanistan. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites that are spread to people through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes which bite mainly between dusk and dawn. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that there were about 124–283 million cases of malaria in 2013 and an estimated 367000–755000 deaths [1]. Afghanistan has the fourth largest malaria burden worldwide of any country outside of Africa [2] and the second highest burden of malaria in the Eastern Mediterranean region [3] with ~60% of the population, or nearly 14 million people, living in endemic areas of Afghanistan [4]. Past evidence has shown that the use of vertical government indoor residual spraying and treatment with chloroquine had almost eradicated the disease before the military conflicts and instability [5]. The three decades of armed conflict have left the country's health sector barely functioning with many malaria programmes scrapped. With the restoration of political stability in 2001, some changes have begun to appear and more systematic studies on the disease are becoming possible. Currently the National Malaria and Leishmaniasis Control Programme (NMLCP) and partners are tasked with the routine information system to report monthly malaria cases by health facility [6].

Leishmaniasis is the third most common vector-borne disease caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania. Over 30 Leishmania species known to infect humans are transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sand flies [7]. There are three main types of leishmaniasis: (i) visceral leishmaniasis (VL), often known as kala-azar and the most serious form of the disease; (ii) CL which is the most common, and (iii) mucocutaneous [7]. The WHO's recent review shows that over 98 countries and territories are endemic for leishmaniasis. It is estimated that about 0·2–0·4 million new VL cases and 0·7–1·2 million new CL cases occur each year worldwide [8]. More than 70–75% of the global CL cases occur in ten countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Iran, Peru, Sudan and Syria [8]. In Afghanistan, the majority of leishmaniasis cases are caused by Leishmania tropica which is transmitted anthroponotically (i.e. humans are the reservoir) by the sand fly (Phlebotomus sergenti) [9–11]. Afghanistan is a CL-endemic country and the disease is of serious health concern with about 200 000 estimated new cases of CL infection reported nationwide and 67500 cases in Kabul alone [11, 12]. The burden and the psychological consequences of an infected individual can be disturbing; in some cases infected women are stigmatized and may be deemed unsuitable for marriage and motherhood [13].

It is very common for vector-borne infectious diseases to have similar hotspots; this can be due to overlapping geographical distribution of the vector. The suitability of breeding sites and environmental conditions may enhance simultaneous transmission of multiple parasites. Incidences of multi-parasite infections have been documented in many continents both in animals and humans [14–17]. Co-infection of a host by multiple parasite species is a commonly observed condition, where an individual's susceptibility and infectiousness are affected at various levels [16]. The co-existence of multiple pathogens in certain populations as well as their distribution is part of a natural selection, as a result of favourable ecological and host factors, which include the biological interactions of the parasites within the host [16, 17]. The presence of both malaria and leishmaniasis in humans could influence disease outcome and progression of diseases due to the modulation of immune response [16, 18, 19].

In Afghanistan, malaria incidence and transmission have been linked to a number of factors, including climate [4, 5] and climate change [20–22], geography [23, 24], migration [24], socioeconomic level [25], as well as control strategies [26]. However, the risks of anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) include poor housing, poor sanitary conditions (e.g. lack of waste management, open sewerage), which may increase sand-fly breeding and resting sites as well as their access to humans [27], and mass migration of infected (and infectious) Afghan refugees [28]. Moreover, household construction materials, house design, density and presence of the disease in neighbourhoods are significant risk factors for the incidence of ACL [29]. Rodents were revealed to be the natural host of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) in the outbreak around Mazar-e Sharif and the seasonality in the occurrence of ZCL in humans was attributed to seasonal activity of the rodents [30]. Furthermore, altitude was found to be a risk factor as well as excess risk of CL in the northeastern and southeastern parts of Afghanistan [31].

An important way to understand disease trends and planning prevention or eradication actions is to identify factors that might influence the incidence and transmission of the disease. A challenge in studying the vector-borne disease risk in Afghanistan is the heterogeneity of incidence, due to the high variation in the landscape and climate of the country. These diseases are sensitive to climatic changes such as rainfall, temperature and humidity. For example, some parts of Afghanistan that lie >2000 m above sea level are relatively free of malaria, while in areas of lower elevation malaria is prevalent between April and December. The impact of environmental influences on these diseases cannot be ruled out and human activity plays a significant role in the dispersion of the vectors, thereby changing the geographical distribution of the disease.

The main objective of this study is to investigate the association between the incidence of malaria and CL incidence in Afghanistan and identify the environmental risk factors associated with these two diseases. It is common to see individuals with both infections; multiple parasite infections are widespread across diverse ecosystems in the tropics and subtropics [15]. The formulated model will be used for short-term forecasting using 12-month incidence data from Afghanistan. Risk factors for multiple infections will be simultaneously analysed. As in most vector-borne diseases, geographical variations cannot be ruled out and risk factors may vary geographically [32]. Here we develop a bivariate model that allows for incorporation of spatial information as well as temporal dependency.

DATA SOURCES

Study area and data collection

Afghanistan is a malaria- and CL-endemic country located in South Asia; it is a landlocked country that is characterized by mountainous regions. The NMLCP, under the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), manages malaria and leishmaniasis surveillance. The datasets used in this study were confirmed primary malaria and CL cases reported to the Afghanistan Health Management Information System (HMIS) of the MoPH in 2009.

The malaria cases were confirmed by examining the blood slides at provincial or district hospitals; comprehensive health centres (CHC) or at basic health centres (BHC). The number of cases were noted on a weekly basis (when possible) and monthly reports were made to the district/provincial MoPH HMIS offices. A total of 390729 cases of malaria (from 521817 blood slides examined) were recorded in 2009, out of which 94% cases were Plasmodium vivax and the remaining cases were P. falciparum. The leishmaniasis infections were confirmed clinically or by examining the Leishmania parasites in the skin lesion biopsy using calibrated ocular micrometre-supported binocular light microscopy. The dataset consisted of 41072 CL cases from a total of 20 provinces in Afghanistan. In this study, the focus is on primary cases of P. vivax malaria because it is responsible for most of the malaria cases in Afghanistan. We focus here on the 20 provinces (out of 34 provinces in Afghanistan) with complete time-series cases of both malaria and CL monthly incidence data in 2009. The 2009 Afghanistan population data was obtained from the Central Statistics Organization of Afghanistan. The study area in this study represents about 75% of the entire population of Afghanistan in 2009. Figures 1–3 show the distribution of malaria and leishmaniasis cases, a map of Afghanistan giving the names and locations of the provinces included in the study and distribution of the Afghanistan population in 2009. See also Supplementary Appendices 1–4 for the time-series plots and maps of disease occurrence data.

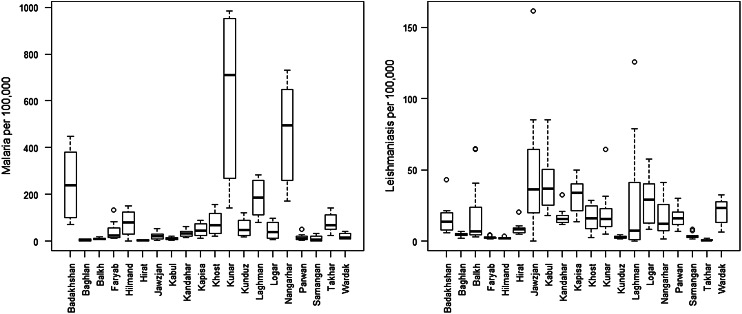

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the reported total number of cases of malaria and leishmaniasis (per 100 000) at provincial level in Afghanistan in 2009. The line in the middle of the boxplot indicates the median value.

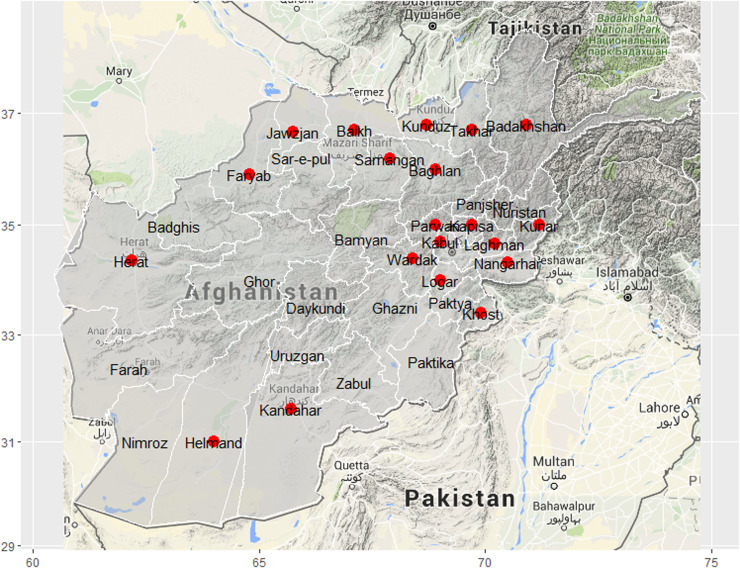

Fig. 2.

Map of Afghanistan showing the names and locations of the 20 provinces (red dots) included in the study.

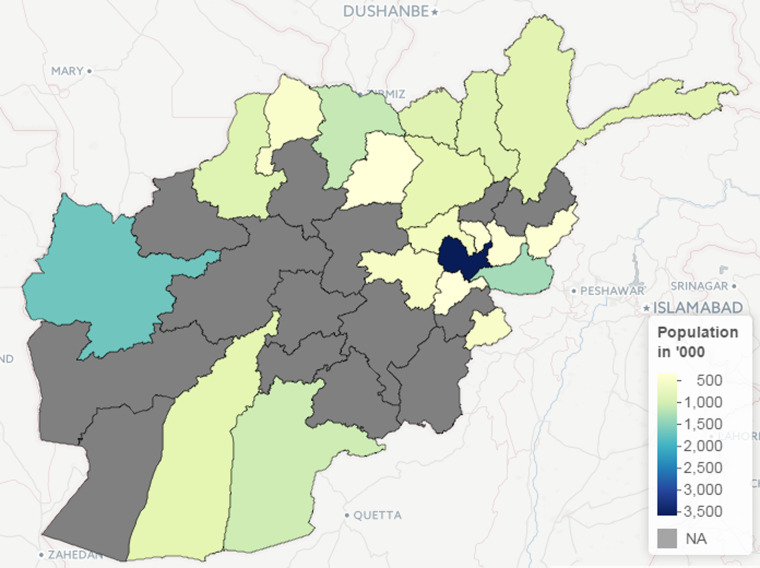

Fig. 3.

The population of the 20 provinces in Afghanistan included in the study.

Environmental data

The role played by environmental factors in the dynamics and transmission of infectious diseases and their importance have been discussed elsewhere [33–37]. The environmental covariates used in this study were altitude (metres), land surface temperature (LST) (K) and rainfall (mm). Datasets on these variables are available from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Earth Observations (NEO) (http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/) and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org). The LST satellite datasets were collected by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) at 1 km spatial resolution and temporal resolution of 1 month. Rainfall was measured by the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) (http://trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov/) jointly conducted by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) at monthly temporal resolution and 0·25° x 0·25° spatial resolution. The altitude data was extracted from the USGS ftpserver (http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org) at a 1-degree digital elevation model. The environmental datasets are depicted in Figures 4–6 while the time-series plots of the environmental data can be found in Supplementary Appendix 5.

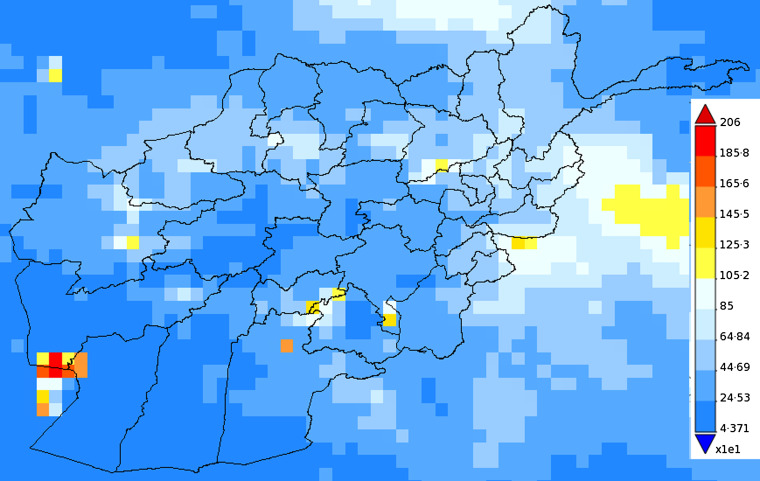

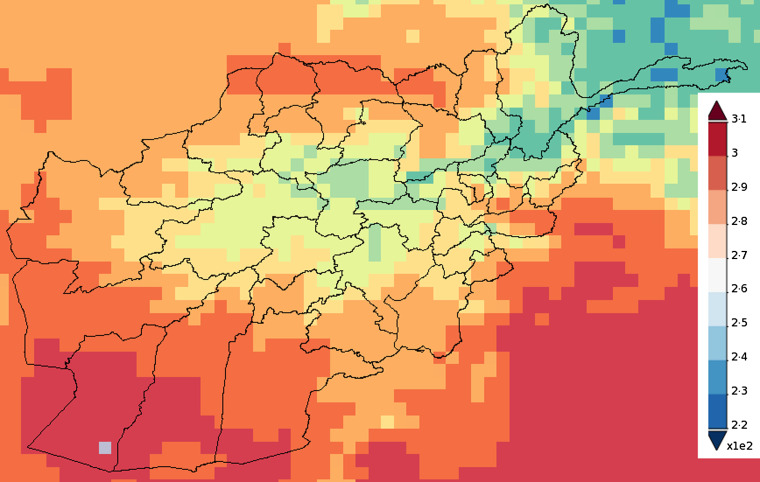

Fig. 4.

Map of Afghanistan showing the accumulated precipitation (mm) in 2009.

Fig. 5.

Map of Afghanistan showing the average temperature (K) in 2009.

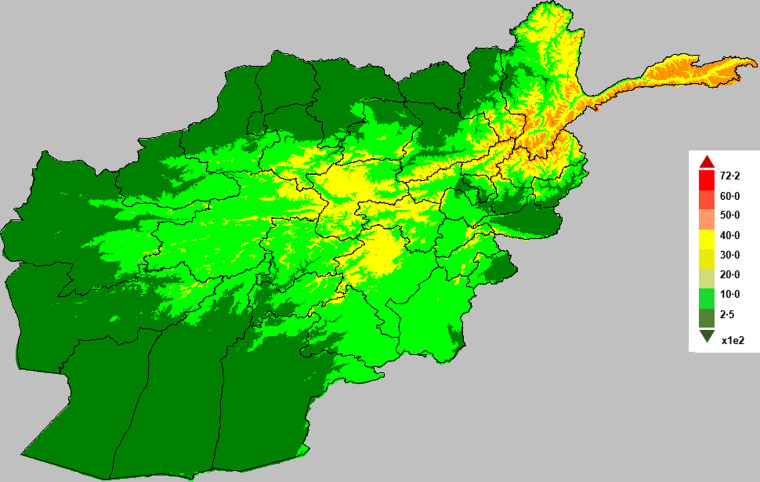

Fig. 6.

Map of Afghanistan showing altitude (in metres).

Spatial scan statistics

Spatial and space–time scan statistics are versatile tools in infectious diseases surveillance for detecting clusters in disease outbreaks. The use of spatial scan statistics under the framework of geographic information system is a growing area in disease modelling and disease epidemiology.

Our objective using scan statistics was to find significant case clusters, i.e. sets of provinces where the total case count was significantly larger than expected based on census population estimates. To find clusters of interest, we used SaTScan [38] to apply a test statistic to province-level case counts aggregated in circular windows of increasing radius centred at each province centroid, with a maximum cluster size of provinces covering 50% of the national population. Clusters with the largest test statistics were tested for statistical significance. This significance was assessed using the default 999 Monte Carlo trials drawn under the null hypothesis that the observed case count represents the census distribution [39]. If the P value derived by ranking a test statistic calculated from observed data against the 999 statistics calculated similarly for the Monte Carlo trials was below our alpha level of 5%, then the observed cluster was considered significant. For the test statistic, we used SaTScan's Poisson log likelihood ratio, and we conducted this analysis separately for malaria and leishmaniasis.

Spatial time-series models

A multivariate model was used to simultaneously assess the effects of environmental variables on malaria and leishmaniasis using province-level monthly aggregated data. Also, when the interdependency between disease cases, caused by different pathogens, is of particular interest to further understand the dynamics of such diseases, a multivariate model is appropriate [39]. Another important phenomenon in time-series analysis of infectious disease is overdispersion. It is very common to model the number of monthly cases of infectious disease incidence at each location or time as a Poisson count. However, when overdispersion is more likely, then the usual Poisson assumption does not reflect the overdispersion.

In this study, overdispersion is of particular interest because of the aggregation of data from homogeneous zones (where the data have a similar distribution) with significant differences among the zonal means. Similarly, the differences in these means may be due to non-uniform underreporting of disease incidence which may likely induce overdispersion. The Negative binomial (NegBin) model is a flexible observation model that allows for overdispersion [40]. The Poisson distribution is replaced with the negative binomial  to allow for overdispersion through the specification of the overdispersion parameter ψ, while the conditional mean and the conditional variance are given by μi,t and μi,t, (1 + ψμi,t), respectively [41, 42].

to allow for overdispersion through the specification of the overdispersion parameter ψ, while the conditional mean and the conditional variance are given by μi,t and μi,t, (1 + ψμi,t), respectively [41, 42].

Model specification

The multivariate analysis will be implemented via an adapted version of the bivariate model proposed by Paul & Held [41]. The model allows for different types of variation and the correlation will be incorporated within a single model. Let yi,t denote the number of cases of specific disease in ‘unit’ i = 1, 2, …, m, at time t = 1, …, T; the unit in this case might represent geographical regions or multiple diseases. The disease counts are assumed to be negatively binomially distributed,  with the conditional mean given by

with the conditional mean given by

| 1 |

where νi,t, λi,t, ϕi,t > 0; log(νi,t) is the endemic component, log(λi,t) is the autoregressive component, while log(ϕi,t) is the neighbour-driven component; yj,t−l denotes the disease counts in unit j at time ‘t − l’ with lag l ∈ {1, 2, …} and wj,i is the row-standardized spatial weights matrix (which define how cases in other regions j relate to cases in region i) is specified as follows: wj,i = 1/no. of neighbours of region i. The matrix ωi,j is based on contiguous neighbouring regions in which neighbours have a value of 1 and 0 otherwise.

Univariate models

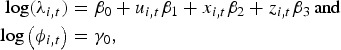

In the general model, we considered special cases of equation (1). We fitted a negative binomial model to the univariate time-series of malaria and leishmaniasis diseases separately as models 1 and 2. The three unknown quantities, endemic component (νi,t), autoregressive epidemic component (λi,t), and neighbour-driven spatio-temporal component (ϕi,t) will be decomposed additively on the log scale. We have used the following model formulations in order of complexity models #a to #d, where # is the indicator for the type of disease, i.e. 1 refers to models for the malaria disease (models 1a–1d) while 2 indicates models for the leishmaniasis disease (models 2a–2d).

Model #a. This is a baseline model which includes a trend parameter, sinusoidal wave of frequency to capture seasonality and the offset population size in the endemic term (without random effects), and neighbour driven term with no autoregressive term. The model is given as:

| 2 |

where  and log(ϕi,t) = γ0

and log(ϕi,t) = γ0

Model #b. Model b is similar to model a and, in addition, includes an autoregressive term defined as log(λi,t) = β0.

Model #c. This model is similar to model b and, in addition, includes a random-effects parameter αi in the endemic component.

Model #d. Model d is similar to model c and, in addition, includes explanatory variables in the autoregressive component.

| 3 |

|

where α0, α1, α2, α3, β0, β1, β2, β3, γ0 are the regression parameters; αi is a random effect that is normally distributed with a mean 0 and variance Σ; ui,t, xi,t, zi,t correspond to the environmental variables altitude, precipitation and temperature; ni,t the offset population size and log(ϕi,t) is the neighbour-driven component. An attempt to add a region-specific random-effects term in the neighbour-driven component proved computationally unfeasible.

The endemic component explains the baseline rate of cases that is persistent with a stable temporal pattern (in our case 1 month lag, l = 1). The trend parameter and sinusoidal wave of frequency in the endemic component are used to account for seasonal variation of disease incidence while the random effect term αi in models #c and #d is the region-specific random effect which is assumed to be an independent and identically distributed Gaussian effect with variance . The autoregressive epidemic component (λi,t) is used to capture the occasional outbreaks while the neighbour-driven spatio-temporal component (ϕi,t) enables interdependency exploration between provinces via a spatial weight matrix (wj,i).

. The autoregressive epidemic component (λi,t) is used to capture the occasional outbreaks while the neighbour-driven spatio-temporal component (ϕi,t) enables interdependency exploration between provinces via a spatial weight matrix (wj,i).

Multivariate models

Furthermore, we fitted a bivariate model (model 3) to the monthly numbers of malaria (mal) and leishmaniasis (les) simultaneously. In this case, equation (1) will be defined as follows: let yi,t represent the number of malaria (i = 1) and leishmaniasis (i = 2) cases at time-series t = 1, …, 12. The joint analysis of a malaria and leishmaniasis time-series model with random effects will be specified as equation (3). The conditional mean for the bivariate time-series model (M3) in general formulation is given as:

| 4 |

The endemic component includes single seasonal terms for both ‘mal’ and ‘les’. The interdependencies between malaria and leishmaniasis is captured by ϕmal and ϕles, which would allow us to investigate whether malaria infections predispose leishmaniasis or vice versa. For example, to investigate whether malaria infections predispose leishmaniasis in Afghanistan, the mean of the negative binomial model will be given as:

| 5 |

where ϕ quantifies the influence of past malaria cases on the leishmaniasis disease incidence [36].

All models were implemented in R using the package surveillance [39] as function hhh4 [42] which can be downloaded from the CRAN server at www.r-project.org. The inference for the regression parameters was based on penalized likelihood [41]. In all models, the statistical importance of the variables was judged at 5% level of significance and a positive coefficient implies an increased incidence of the disease when the variable increases.

Model validation

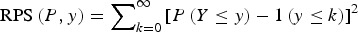

In this study, the proper scoring rules were used to assess the best model. This is because there is no suitable model choice criterion available for nonlinear random-effects models and the extension of classical model choice criteria such as Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to mixed models is challenging [41, 43]. However, Held & Paul [43] noted that asymptotically AIC and the cross-validated logarithmic score are equivalent while BIC corresponds to the logarithmic score of the one-step-ahead predictions of the complete data.

A proper scoring rule measures the differences between the actual observed value and estimated predictive values [41, 43]. A larger proper score indicates a larger discrepancy in the predictive model. For observed value, y; let P(Y = y) and P(Y ⩽ y) denote the probability mass function and cumulative probability distribution of the negative binomial distribution respectively. The logarithm score of predictions, is given as; log S(P, y) = −log[P(Y = y)] which is sensitive to extreme cases (it penalizes low probability). Similarly, a less sensitive scoring rule, the rank probability score (RPS) is given as;  .

.

We computed the mean scores over a set of predictions based on probabilistic one-step-ahead predictions (the model needs to be re-fitted at each time point). Finally, a Monte Carlo permutation test was used to evaluate mean scores between two models by testing the statistical significance of the observed difference between mean scores from two different models using 9999 random permutations. The Monte Carlo P value is calculated as:

|

RESULTS

Preliminary data analysis

In this study, we used the following environmental and climatic factors: altitude (metres), cumulative rainfall (mm) and maximum temperature (K) to simultaneously explain the incidence of malaria across the provinces of Afghanistan.

Temporal variation

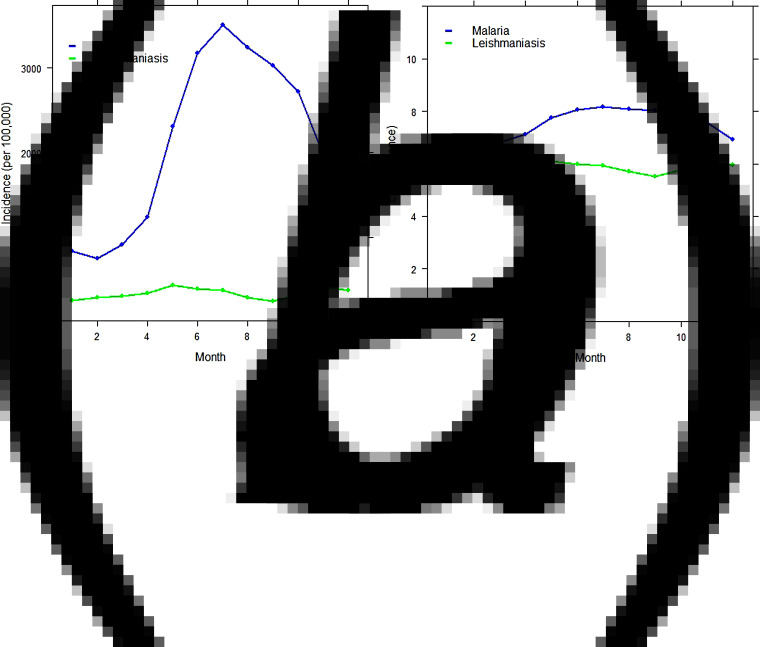

The analysis was begun by exploring the temporal pattern of the monthly cases of malaria and leishmaniasis separately. Figure 7(a, b) shows the time-series plot of the provincial-level aggregated montly incidence of malaria and leishmaniasis diseases per 100 000, as well as the plot of the log-transformed national aggregated monthly incidence of both diseases. Although the monthly profile of leishmaniasis revealed two peaks in the disease occurrence – June to July and November to January – which coincides with summer and winter, respectively, the June–July peak is more obvious and occurred in the same period as malaria. The malaria plot also showed a strong seasonal pattern with high disease incidence in the summer (June–August).

Fig. 7.

Time-series plot of (a) the provincial level and aggregated monthly incidence of malaria and leishmaniasis diseases (per 100 000), (b) log-transformed provincial level aggregated monthly incidence of malaria and leishmaniasis in Afghanistan.

Spatial variation and hotspot analysis

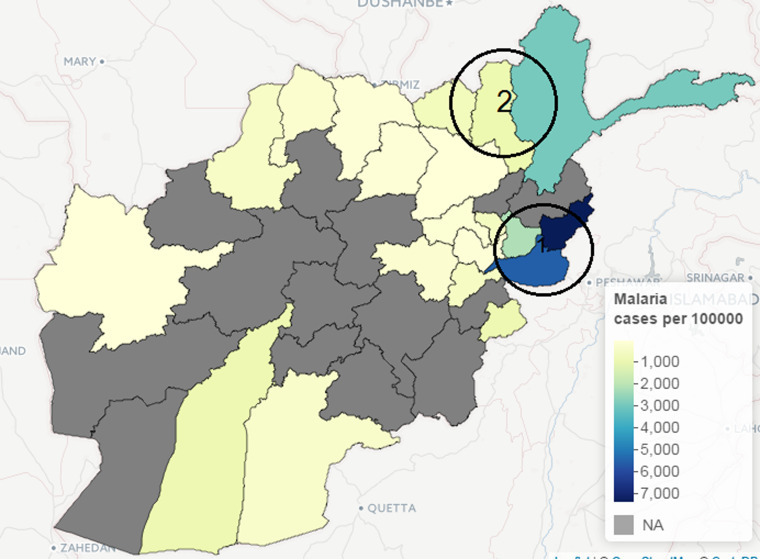

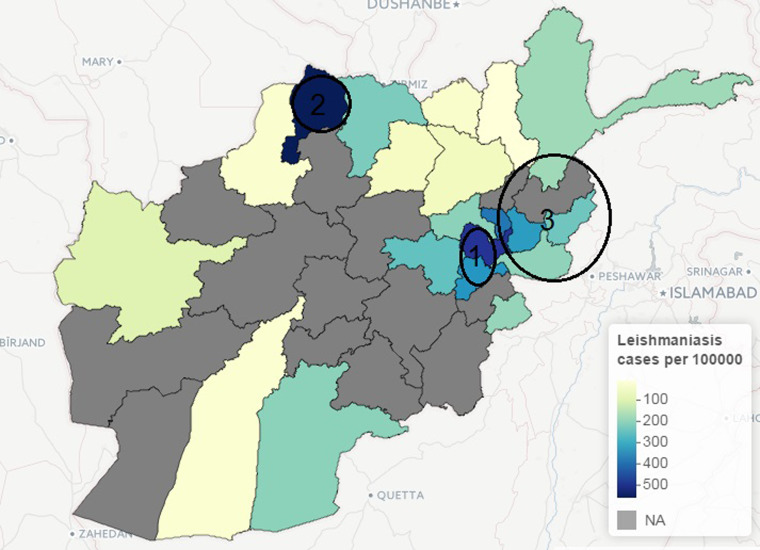

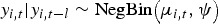

The incidence of leishmaniasis occurred in < 1% of the population except in Kabul province in 2009, with about 2% of the population infected with the disease. Kabul city accounted for >50% of the total new cases of leishmaniasis in 2009, although this may be attributed to availability of healthcare facilities, which is crucial for data gathering in public health studies. Similarly, geographical heterogeneity was observed in the crude counts of malaria across provinces; cases of P. vivax malaria are more prevalent in the province of Nangarhar (43·2% of all cases), followed by Kunar (13·8%) and Badakhshan (8·5%). (See Supplementary Appendices 1–4 for the individual time-series of province level data for both malaria and leishmaniasis.) Geographical disparity in the occurrence of malaria and leishmaniasis in Afghanistan were noted in Figures 8 and 9 (clusters were detected by SaTScan analysis). Malaria incidence shows a clear pattern and six provinces form two geographical clusters (Fig. 8). The first cluster is located in the Eastern part, with a relative risk of 10·79, which comprises Kunar, Nangarhar and Laghman province, while the second cluster is located in the northeastern region. Three geographical clusters (hotspots) were confirmed for leishmaniasis. Higher incidences of leishmaniasis were observed around Kabul area (hotspot 1), northwestern (hotspot 2) and eastern (hotspot 3) regions of Afghanistan (Fig. 9). The relative risk for Kabul and Logar was 5·013, the highest in the three hotspots. Although the hotspot analysis indicates that similar disease clusters exist for malaria and leishmaniasis, especially in the eastern part of the country, the relative risk of malaria (10·79) is higher than that of leishmaniasis (1·15) in this region.

Fig. 8.

Map of Afghanistan showing hotspots of new malaria cases (per 100 000) in 2009.

Fig. 9.

Map of Afghanistan showing hotspots of new leishmaniasis cases (per 100 000) in 2009.

Univariate analysis

It is natural to model disease incidence at each location as a Poisson count. However, as mentioned above, there is the possibility of overdispersion of malaria and leishmaniasis incidences across different locations. Therefore, we began the analysis by assessing the appropriateness of the NegBin model rather than a Poisson model by fitting a basic model with only fixed effects parameters to the malaria data and leishmaniasis data separately. The Poisson model (ψ = 0) provides a poorer fit with an AIC of 21573·29 against the NegBin model (model 1a) with AIC = 3248·06 and ψ = 1·425 (s.e. = 0·116). We then fitted models 1 and 2 to the data following the specification described in equation (2).

For the univariate analysis of the malaria, the results showed that model 1a gave poor prediction based on probability score. The inclusion of random intercept in the endemic component in model 1c improved the model fit. After adding explanatory variables to model 1c (to form model 1d), model 1d provided a better fit based on probability score and Monte Carlo P value than model 1c. Model 1d included autoregression, a seasonal random-effect term as well as environmental variables. Similarly, based on the univariate analysis of the leishmaniasis data, the best model (model 2d) according to probability score (and Monte Carlo P value) included autoregression, environmental variables and random-effect term in the endemic component. The environmental covariates, precipitation and temperature were statistically informative for the risk of transmission of malaria, while altitude and temperature were important for leishmaniasis. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the best-fitting model for the malaria data (model 1d) indicates that the seasonal variation, measured by υi,t, has significant effect on malaria incidence while the dependency on the cases in the previous month can be explained by precipitation and temperature (λi,t). Although, the  value for model 1b is lower than that of model 1d, we based our model assessment on the

value for model 1b is lower than that of model 1d, we based our model assessment on the  value which has been shown to have clear advantages over other scoring rules [44].

value which has been shown to have clear advantages over other scoring rules [44].

Table 1.

Results from univariate analysis of malaria disease in Afghanistan 2009 with standard errors

| Components | Model 1a (without autoregression) | Model 1b (with fixed parameters only) | Model 1c (with random effects) | Model 1d (with random effects + environmental data) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endemic υi,t | ||||

| α0 (s.e.) | 9·223 (0·493) | 14·532 (5·435) | ||

| Trend α1 (s.e.) | −0·045 (0·079) | 0·254 (0·571) | −0·147 (0·076) | −0·130 (0·075) |

| Sin α2 (s.e.) | 0·923 (0·207) | 6·228 (1·409) | 1·399 (0·201) | 1·330 (0·213) |

| Cos α3 (s.e.) | −1·806 (0·150) | −0·887 (0·438) | −1·621 (0·097) | −2·159 (0·082) |

|

2·152 | 2·1231 | ||

| IID random effects | 8·302 (0·485) | 8·419 (0·506) | ||

| Autoregressive λi,t | ||||

| β0 (s.e.) | −0·031 (0·037) | −0·518 (0·100) | −1·165 (0·931) | |

| Log Alt β1 (s.e.) | 0·077 (0·122) | |||

| Precip β2 (s.e.) | 0·015 (0·005) | |||

| Temp β3 (s.e.) | 1·125 (0·022) | |||

| Neighbour-driven ϕ | ||||

| γ0 (s.e.) | −6·269 (0·906) | −5·664 (0·435) | −5·488 (0·526) | −5·610 (0·660) |

| Overdispersion ψ (s.e.) | 1·425 (0·116) | 0·188 (0·019) | 0·112 (0·012) | 0·111 (0·012) |

| AIC | 3248·06 | 2740·09 | ||

(P values) (P values) |

7·169 (0·0091) | 6·653 (0·0440) | 6·815 (0·0739) | 6·763 |

(P values) (P values) |

509·359 (0·0007) | 209·019 (0·0011) | 133·606 (0·0012) | 117·505 |

IID, Independent and identically distributed; AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion.

In the rows for  and

and  measures, the Monte Carlo P values give comparisons of malaria models 1a–1c to the best model (model 1d) based on permutation tests for paired observations (9999 permutations).

measures, the Monte Carlo P values give comparisons of malaria models 1a–1c to the best model (model 1d) based on permutation tests for paired observations (9999 permutations).

Table 2.

Results from univariate analysis of leishmaniasis disease in Afghanistan 2009 with standard errors

| Model 2 | Model 2a (without autoregression) | Model 2b (with fixed parameters only) | Model 2c (with random effects) |

Model 2d (with random effects + environmental data) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endemic: υi,t | ||||

| α0 (s.e.) | −27·422 (8·962) | −23·510 (5·414) | ||

| Trend α1 (s.e.) | 2·393 (8·406) | −11·521 (3·510) | 1·142 (1·310) | −0·008 (0·001) |

| Sin α2 (s.e.) | 27·979 (5·168) | 38·552 (1·559) | 11·053 (5·301) | 1·515 (0·058) |

| Cos α3 (s.e.) | 0·580 (1·188) | −0·227 (1·169) | 0·199 (0·320) | 1·919 (0·058) |

|

4·3932 | 1·843 | ||

| IID random effects | −10·048 (7·821) | 4·863 (0·333) | ||

| Autoregressive: λi,t | ||||

| β0 (SE) | −0·025 (0·063) | 0·075 (0·051) | 2·203 (0·482) | |

| Log Alt β1 (s.e.) | −0·391 (0·068) | |||

| Precip β2 (s.e.) | −0·945 (2·709) | |||

| Temp β3 (s.e.) | 0·006 (0·003) | |||

| Neighbour-driven ϕ | ||||

| γ0 (s.e.) | −3·400 (0·321) | −3·401 (0·269) | −5·330 (0·874) | −7·269 (0·833) |

| Overdispersion ψ (s.e.) | 1·089 (0·094) | 0·370 (0·043) | 0·258 (0·032) | 0·195 (0·32) |

| AIC | 1574·19 | 1490·26 | ||

(P values) (P values) |

17·607 (0·0002) | 13·399 (0·0492) | 12·607 (0·0232) | 11·721 |

(P values) (P values) |

167·650 (0·0012) | 165·830 (0·0011) | 162·651 (0·0027) | 159·811 |

IID, Independent and identically distributed; AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion.

In the rows for  and

and  measures, the Monte Carlo P values give comparisons of leishmaniasis models 1a–1c to the best model (model 1d) based on permutation tests for paired observations (9999 permutations).

measures, the Monte Carlo P values give comparisons of leishmaniasis models 1a–1c to the best model (model 1d) based on permutation tests for paired observations (9999 permutations).

Multivariate analysis

Until now, separate univariate models have been fitted to malaria and leishmaniasis. Joint models for malaria and leishmaniasis was introduced via the bivariate time-series model. A number of candidate models are fitted based on different interdependencies structure [e.g. in equation (5)]; however, the model that includes the influence of past malaria cases (lag of 1 month) on the incidence of leishmaniasis has the best fit with the smallest AIC = 286·93. The model allows the investigation of whether malaria infections predispose leishmaniasis disease. The model consists of two fitted means μmal,t and μles,t. Table 3 shows the results from the bivariate model that indicates the effect of past malaria cases on the incidence of leishmaniasis. The mean μmal,t can be separated into two additive components: an endemic and autoregressive components for the malaria data while the mean μles,t can be separated into an endemic, an autoregressive and a malaria-driven component for the leishmaniasis data. The model suggests that there is an association between malaria disease and leishmaniasis with ϕ = 19·513 which quantifies the influence of past malaria cases on the leishmaniasis disease incidence.

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis of malaria and leshmaniasis disease in Afghanistan 2009

| Parameter | Malaria | Leishmaniasis |

|---|---|---|

| Endemic α0 (s.e.) | 7·052 (0·420) | 5·112 (0·528) |

| Trend α1 (s.e.) | −1·115 (0·102) | 0·145 (0·212) |

| Sin α2 (s.e.) | −1·115 (0·102) | 0·145 (0·212) |

| Cos α3 (s.e.) | −1·463 (0·101) | 0·870 (0·174) |

| Autoregressive β0 (s.e.) | −1·104 (0·732) | −0·608 (0·484) |

| Malaria-driven ϕ (s.e.) | 19·513 (1·056) | |

| Overdispersion ψ (s.e.) | 0·012 (0·005) | 0·016 (0·008) |

DISCUSSION

This project represents the first study to investigate the association between the incidences of malaria and leishmaniasis in Afghanistan and identify the risk factors associated with these two diseases. Three classes of flexible statistical models were presented. First, two univariate models which were fitted to malaria and leishmaniasis data separately were used. Then bivariate models for simultaneously modelling of the dependency between malaria and leishmaniasis incidence was conducted.

Often, there exist geographical and temporal variations in the incidence of vector-borne diseases; these vector pathogens are often affected by a multitude of factors, some of which are climatic variables (abiotic) and others are human activities such as farming [33, 34, 37]. The relationship between infectious disease incidence and climatic variables is complex [4, 35, 36]. Some studies have argued that the precise shape of the relationship is questionable [32, 35].

For the univariate models, the environmental covariates, precipitation and temperature, were statistically informative for the risk of malaria, while altitude and temperature were important for leishmansiasis. Failure to find effects of precipitation as significant risk factor in the transmission of leishmaniasis may be a result of data aggregation. Perhaps weekly environmental data would provide more information than monthly data in the case of short-term variations. In the best fitting model for the malaria data (model 1d), the seasonal variation, measured by υi,t, showed a significant effect, while dependency on the number of cases in the previous month was explained by precipitation and temperature. Similar to leishmaniasis disease, there was a significant effect of the influence of adjacent regions on malaria incidence. The outbreak size of leishmaniasis in the previous month is associated with altitude and temperature (model 2d).

Environmental and climate risk factors, such as temperature, precipitation and altitude, play a major role in spreading both diseases in the studied areas. Harsh environment in the studied areas may lead to over exposure of the population to these two diseases. Precipitation is an important environmental factor for the transmission of leishmaniasis and malaria because it directly affects their vectors. For example, rodents are natural hosts of ZCL and their associated activities with the sand-fly vector is directly linked to the surge in the occurrence of human ZCL [45]. The vectors flourish in areas with high annual precipitation which provide a suitable environment [46]. Precipitation has also been described to provide the greatest contribution in defining the potential distribution of the sand fly [47]. It is not surprising that areas with high precipitation are known for farming, which in turn provides shelter for rodents and hence an ideal habitat for sand flies which are natural hosts of ZCL [46]. Similarly, precipitation also means that a small body of water can easily serve as a habitat for infective mosquitoes and breeding sites, which consequently increases the transmission of malaria. In Afghanistan, the northern region is known for rice farming [48] and the same bodies of water are often used for irrigation throughout the year.

Our findings show an increase in precipitation has a positive effect on malaria; however, precipitation has no significant effect on leishmaniasis. One explanation for a non-significant effect of precipitation on leishmaniasis is that intense rainfall (>37·34 mm) can negatively affect the incidence of ZCL [49] due to flooding of rodent burrows [50].

The effect of temperature is key to the survival and lifespan of sand flies [51]. Low temperatures negatively affects their longevity [50] as well as high temperatures [51]. Poor housing and poor sanitary conditions are common risk factors for ACL because they can serve as breeding and resting sites for the disease vectors [27], thereby protecting them from extreme temperatures. Similarly, extreme temperatures (especially <24 °C and >33°C) can hinder the breeding of malaria vector [52, 53]. At that temperature level, it is unsuitable for their survival or larval and incubation duration [54]. The relationship between altitude and malaria/leishmaniasis is associated with their vectors. Altitude has been described as being closely related to temperature, rainfall and vegetation [51]. At higher altitudes, the temperature is lower, precipitation increases and vegetation changes [50].

There are a number of limitations to this study; the use of monthly provincial-level aggregated data reduced the number of time points for the data counts, thereby making it difficult to model the seasonal variation adequately. Moreover, the exact dates of infections are unknown, which may affect autocorrelation. Additionally, one of the limitations of conducting a national-level research on malaria and leishmaniasis in Afghanistan is the availability of long-term data. Despite these data limitations, our study provides extensive information that can supplement patient-specific studies to assess the effect of previous malaria cases on leishmaniasis and to understand and quantify the impact of environmental risk factors. We were able to formulate models that could be used for short-term forecasting using 12-month incidence data from Afghanistan.

The study of malaria and leishmaniasis is of paramount importance in public health study of parasitic infections. The two diseases are currently two of the major causes of mortality and morbidity among human parasitic infections, with an enormous social and economic impact [18]. The current study shows an association between the incidence of malaria and leishmaniasis incidence in the studied areas of Afghanistan. The hotspot analysis indicates that there is one hotspot in common between the two diseases (cluster 1 for malaria and cluster 3 for leishmaniasis) while the other clusters occurred in different provinces. The geographical overlap of the two diseases may be a result of the two major parasitic diseases overlapping geographically and, more importantly, it may be due to the fact that the two diseases are co-infected within the same patients [16, 17].

Findings in this study suggest that people living in areas with malaria are at increased risk for leishmaniasis infection. This is in agreement with other studies that state concomitant Plasmodium infection seems to increase the susceptibility to leishmaniasis [18]. Moreover, previous studies has found patients suffering from malaria infections exhibit the presence of Leishmania parasites in their body [55] or vice versa [16, 17]. The outcome of malaria infections can be altered according to the Leishmania species involved [19]. When both malaria and leishmaniasis are present in humans, it affects the disease outcome and progression of disease due to the modulation of the immune response [18, 19].

The adaptability of the parasitic vectors has allowed malaria and leishmaniasis to spread into new and different environments [56]. This issue will require increased efforts in the fields of urban entomology, civil engineering, disease surveillance and tropical urban ecology in order to address the continued spread of this disease. Given the geographical overlapping of endemic areas of both malaria and CL cases, the study highlights the presence and importance of environmental factors such as altitude, temperature and precipitation. Clinical concerns arise when the two diseases co-occur in the same patients or have similar transmission route. This may produce different symptoms and conditions along with increased mortality risk, possibly associated with inappropriate treatment. Local healthcare authorities should consider the co-infection problem by recommending systematic leishmaniasis screening for all malaria patients or vice versa in endemic areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Sebastian Meyer and Michael Höhle for their helpful suggestions on package surveillance. We also thank the three anonymous reviewers for suggestions and comments to improve the manuscript. Special thanks go to Sarah Campion for her editorial feedback and careful reading of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816002764.

click here to view supplementary material

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naieni KH, et al. Malaria status in economic cooperation countries; achievement and gaps toward United Nations Millennium Development Goals. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2012; 41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safi N, et al. National malaria indicators assessment, 2008. Afghanistan Annual Malaria Journal 2009; 1: 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adimi F, et al. Towards malaria risk prediction in Afghanistan using remote sensing. Malaria Journal 2010; 9: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolaczinski J, et al. Malaria control in Afghanistan: progress and challenges. Lancet 2004; 364: 1506–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alegana VA, et al. Modelling the Incidence of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum Malaria in Afghanistan 2006–2009. PLoS ONE 2014; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates PA. Transmission of Leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. International Journal for Parasitology 2007; 37: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Status of endemicity of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashford R, Kohestany K, Karimzad M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: observations on a prolonged epidemic. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 1992; 86: 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killick-Kendrick R, Killick-Kendrick M, Tang Y. Anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: the high susceptibility of Phlebotomus sergenti to Leishmania tropica. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1995; 89: 477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adegboye OA. Bayesian spatial analysis and disease mapping of leishmaniasis outbreak in Afghanistan. Proceedings of the 58th World Statistics Congress of the International Statistical Institute 2011, pp. 6332–6339. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reithinger R, et al. Anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis, Kabul, Afghanistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2003; 9: 727–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reithinger R, et al. Social impact of leishmaniasis, Afghanistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2005; 11: 634–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petney T, Andrews R. Multiparasite communities in animals and humans: frequency, structure and pathogenic significance. International Journal for Parasitology 1998; 28: 377–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raso G, et al. Multiple parasite infections and their relationship to self-reported morbidity in a community of rural Cote d'Ivoire. International journal of Epidemiology 2004; 33: 1092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Bogaart E, et al. Concomitant malaria among visceral leishmaniasis in-patients from Gedarif and Sennar States, Sudan: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Bogaart E, et al. Prevalence, features and risk factors of malaria co-infections among visceral leishmaniasis patients from Amudat Hospital Uganda. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2012; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marques CS, et al. Studies in a co-infection murine model of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi and Leishmania infantum: interferon-γ and interleukin-4 mRNA expression. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2005; 100: 889–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinna RA, et al. Malaria-cutaneous leishmaniasis co-infection: influence on disease outcomes and immune response. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016; 7: 982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhimal M, Ahrens B, Kuch U. Climate change and spatiotemporal distributions of vector-borne diseases in Nepal – a systematic synthesis of literature. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ready PD. ‘Epidemiology of Visceral Leishmaniasis.’ Clinical Epidemiology 2014; 6: 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bounoua L, et al. Linking climate to incidence of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (L. major) in pre-Saharan North Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2013; 10: 3172–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooker S, et al. Spatial epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax, Afghanistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2006; 12: 1600–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faulde M, et al. Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis outbreak in Mazar-e Sharif, northern Afghanistan: an epidemiological evaluation. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008; 298: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard N, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with the purchasing of insecticide-treated nets in Afghanistan and their implications for social marketing. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2003; 8: 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowland M, et al. Prevention of malaria in Afghanistan through social marketing of insecticide-treated nets: evaluation of coverage and effectiveness by cross-sectional surveys and passive surveillance. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2002; 7: 813–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salam N, Al-Shaqha WM, Azzi A. Leishmaniasis in the Middle East: incidence and epidemiology. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowland M, et al. An outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in an Afghan refugee settlement in North-West Pakistan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1999; 93: 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reithinger R, Mohsen M, Leslie T. Risk factors for anthroponotic cutaneous Leishamaniasis at the household level in Kabul, Afghanistan. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2010; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michael F, et al. Zoonotic cutaneous Leishmaniasis outbreak in Mazar-e Sharif, northern Afghanistan: an epidemiological evaluation. International Journal of Medical Microbiolog y. 2008; 298: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adegboye OA, Kotze D. Disease mapping of leishmaniasis outbreak in Afghanistan: spatial hierarchical Bayesian analysis. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease 2012; 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adegboye OA, Kotze D. Causes and patterns of morbidity and mortality in Afghanistan: Joint estimation of multiple causes in the neonatal period. Canadian Studies in Population 2014; 41. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hay SI, et al. Remotely sensed surrogates of meteorological data for the study of the distribution and abundance of arthropod vectors of disease. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 1996; 90: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers DJ, et al. Satellite imagery in the study and forecast of malaria. Nature 2012; 415: 710–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiang R, et al. Meteorological, environmental remote sensing and neural network analysis of the epidemiology of malaria transmission in Thailand. Geospatial Health 2006; 1: 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanford J, et al. Implications of temperature variation for malaria parasite development across Africa. Nature Scientific Reports 2013; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adegboye OA, Kotze D. Epidemiological analysis of spatially misaligned data: A case of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus outbreak in Nigeria. Epidemiology and Infection 2014; 142: 940–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulldorff M. A spatial scan statistic. Communication in Statistics – Theory Methods 1997; 26: 1481–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hohle M. Surveillance: an R package for the monitoring of infectious diseases. Computational Statistics 2007; 22: 571–582. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Held L, Hohle M, Hofmann M. A statistical framework for the analysis of multivariate infectious disease surveillance counts. Statistical Modelling 2005; 5: 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paul M, Held L. Predictive assessment of a non-linear random effects model for multivariate time series of infectious disease counts. Statistics in Medicine 2011; 30: 1118–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul M, Held L, Toschke AM. Multivariate modelling of infectious disease surveillance data. Statistics in Medicine 2008; 29: 6250–6267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Held L, Paul M. Modeling seasonality in space-time infectious disease surveillance data. Biometrical Journal 2012; 54: 824–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boero G, Smith J, Wallis KF. Scoring rules and survey density forecasts. International. Journal of Forecasting 2011; 27: 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faulde M, et al. Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis outbreak in Mazare Sharif, northern Afghanistan: an epidemiological evaluation. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008; 298: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fathy FM, El-Kasah F, El-Ahwal AM. Emerging cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sirte-Libya: epidemiology, recognition and management. Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology 2009; 39: 881–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdel-Dayem MS, et al. The potential distribution of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Libya based on ecological niche model. Journal of Medical Entomology 2012; 3: 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faulde MK, et al. Malaria reemergence in northern Afghanistan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2007; 13: 1402–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toumi A, et al. Temporal dynamics and impact of climate factors on the incidence of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Tunisia. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease 2012; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chalghaf B, et al. Ecological niche modeling for the prediction of the geographic distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2016, 4: 844–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Shazly MM, et al. Seasonal abundance, number of annual generations, and effect of an entomopathogenic fungus on Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae). Environmental Entomology 2012; 1: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mordecai EA, et al. Optimal temperature for malaria transmission is dramatically lower than previously predicted. Ecology letters 2013; 16: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilioli G, Mariani L. Sensitivity of Anopheles gambiae population dynamics to meteo-hydrological variability: a mechanistic approach. Malaria Journal 2011; 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sachs J, Malaney P. The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature 2002; 415: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ab Rahman AK, Abdullah FH. Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) and malaria coinfection in an immigrant in the state of Terengganu, Malaysia: a case report. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2011; 44: 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Claborn DM. The biology and control of leishmaniasis vectors. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases 2012; 2: 127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816002764.

click here to view supplementary material