Abstract

An in vitro system based on Escherichia coli infected with bacteriophage T7 was used to test for involvement of host and phage recombination proteins in the repair of double strand breaks in the T7 genome. Double strand breaks were placed in a unique XhoI site located approximately 17% from the left end of the T7 genome. In one assay, repair of these breaks was followed by packaging DNA recovered from repair reactions and determining the yield of infective phage. In a second assay, the product of the reactions was visualized after electrophoresis to estimate the extent to which the double strand breaks had been closed. Earlier work demonstrated that in this system double strand break repair takes place via incorporation of a patch of DNA into a gap formed at the break site. In the present study, it was found that extracts prepared from uninfected E. coli were unable to repair broken T7 genomes in this in vitro system, thus implying that phage rather than host enzymes are the primary participants in the predominant repair mechanism. Extracts prepared from an E. coli recA mutant were as capable of double strand break repair as extracts from a wild-type host, arguing that the E. coli recombinase is not essential to the recombinational events required for double strand break repair. In T7 strand exchange during recombination is mediated by the combined action of the helicase encoded by gene 4 and the annealing function of the gene 2.5 single strand binding protein. Although a deficiency in the gene 2.5 protein blocked double strand break repair, a gene 4 deficiency had no effect. This argues that a strand transfer step is not required during recombinational repair of double strand breaks in T7 but that the ability of the gene 2.5 protein to facilitate annealing of complementary single strands of DNA is critical to repair of double strand breaks in T7.

Double strand breaks are a frequent hazard to DNA molecules. These breaks can result from a number of causes, including DNA damage, fractures at progressing replication forks, or as part of normal homologous recombination (10, 15, 26, 37, 61). Failure to repair a double strand break can be lethal. Improper repair of double strand breaks can lead to deletions or chromosome aberrations (9, 12, 52). To minimize the deleterious effects of double strand breaks, living organisms maintain an array of repair mechanisms able to correct double strand breaks or rescue partial genomes formed as a result of breaks (3, 10, 12, 21, 22, 26, 38, 39). Recombination-induced DNA replication is a major route to rescue of partial genomes formed by collapse of replication forks in prokaryotes (26). In Escherichia coli, stable DNA replication is induced by forming new replication forks at sites other than the normal origin of replication (22, 27, 32). In bacteriophage T4, recombination between partial genomes formed by double strand breaks and intact T4 DNA molecules induces new replication forks that comprise a major part of the phage's DNA replication cycle (25, 36). It has long been appreciated that recombination is enhanced by double strand breaks. In E. coli, chi sites in the DNA invite endonuclease cleavages that, in turn, allow RecA-mediated strand invasions and consequential homologous recombination (37). In yeast, the double strand break repair model has provided a highly successful explanation for gene conversion events associated with homologous recombination (53, 57). The close relationship between double strand breaks and recombination has prompted speculation that the primary functions of recombination may be repair of double strand breaks and rescue of partial genomes formed by collapsed replication forks (4).

Bacteriophage T7 presents intriguing comparison with other prokaryotic systems as regards repair of double strand breaks. An in vitro system, developed to study T7 DNA replication, is able to repair double strand breaks in the T7 genome with high efficiency (30, 33). Results with this system show interesting differences between aspects of double strand break repair in T7 and similar processes in other biological systems. As with other prokaryotic systems, direct joining of broken ends does not contribute significantly to double strand break repair in T7 (30). T7 double strand break repair is markedly enhanced by the presence of intact DNA molecules homologous to the break site. The quantity and the length of these DNA molecules, referred to as donor DNA, strongly affect repair efficiency (30). In contrast to what is found with E. coli and with bacteriophage T4 (11, 22, 25, 36), T7 double strand break repair is not associated with extensive DNA replication (28). This argues that either re-formation of new replication forks at break sites is not common in T7 or that alternative repair mechanisms are sufficiently robust to allow a high level of repair even when replicative repair mechanisms cannot operate (28).

Under conditions where DNA replication is blocked, double strand breaks in a T7 genome are repaired by insertion of a patch of donor DNA into a gap formed at the break site (29). The insertion process provides a very efficient repair mechanism, sealing about half of the double strand breaks even under conditions where every genome in the reactions has a double strand break. While it is clear that in T7 recombination provides the major pathway of double strand break repair, at least under these experimental conditions, the exact mechanism responsible for these recombinations has yet to be determined. It is not known whether the recombination mechanism responsible for double strand break repair is the same as that which carries out normal homologous recombination between T7 genomes. Also, since E. coli is proficient at double strand break repair, and since there is no a priori reason why host recombination enzymes should not act on T7 DNA, it is possible that host enzymes might be primarily (or exclusively) responsible for the double strand break repair carried out by extracts of T7-infected E. coli. In this paper we show that T7 enzymes are necessary for efficient repair of double strand breaks in the phage genome and that a recA mutation which in the host impedes homologous recombination and causes radiation sensitivity has no discernible effect on repair events in T7. We also test two T7 proteins that are part of the phage's homologous recombination process, for involvement in double strand break repair.

T7's DNA replication mechanism is relatively well understood (45), and the properties of the phage's major DNA replication enzymes have been thoroughly investigated (7, 16, 19, 35, 40, 49, 58, 59). Although the mechanism of homologous recombination in T7 has not yet been determined, it is known that many of T7's DNA replication enzymes also play a role in homologous recombination (1, 5, 17, 24, 42, 43, 47, 51, 54). Of particular interest to the T7 recombination problem is the product of gene 2.5, a single strand DNA binding protein which facilitates annealing of complementary single-stranded DNA molecules (19, 48). This protein, which is essential to phage growth (18), is required for T7 recombination (1, 24, 48, 51). The ability of the gene 2.5 protein to interact with the helicase encoded by gene 4 to carry out strand transfer reactions is particularly relevant to the mechanism of how T7 recombines homologous sequences and how it uses recombination to repair double strand breaks (23, 24). In this paper, we present evidence that mutations which inactivate the gene 2.5 protein block in vitro repair of double strand breaks in the T7 genome, but mutations in the gene 4 helicase cause no reduction in the efficiency of double strand break repair. These findings acknowledge the importance of single strand annealing in T7 recombinational repair but argue against a requirement for strand transfer during this mode of repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and bacteriophage.

Strain W3110 was used as wild-type E. coli. To grow phage with amber mutations, E. coli strains O11′ and AB1157, each of which has an amber suppressor (supE), were used. A recA derivative of W3110 (strain WM295) was constructed by conjugation between JC5088 (recA56) with a thyA derivative of W3110 followed by selection for thy+ UV radiation-sensitive colonies. A recB derivative of strain W3110 was made by P1 transduction of the recB21 mutation into a thyA mutant of W3110. Wild-type and amber mutants of bacteriophage T7 were from the collection of F. W. Studier (54, 55). The complete sequence of the 39,937-bp bacteriophage T7 genome has been published by Dunn and Studier (8). Amber mutants used in this study include am29 in gene 3 (endonuclease), am20 in gene 4 (helicase/primase), am28 in gene 5 (DNA polymerase), and am147 in gene 6 (5′→3′ exonuclease). The T7 ΔA mutation, previously described (41), is a deletion extending from the promoter of gene 1.3 (T7 ligase) to the promoter of gene 1.5 (function unknown). T7X refers to wild-type T7 with a unique XhoI site engineered at position 6663 (41). The gene 2.5 mutation used in this study is a trx insertion placed in the phage 2.5 gene and kindly provided by Kim and Richardson (18). Gene 2.5 is essential for T7 growth; to maintain phage carrying an inactivated gene 2.5, an E. coli host with gene 2.5 carried on a plasmid was employed (18). The 2.5 mutation was combined with T7 amber mutations by standard phage crosses as described by Studier (55). Phage with gene 2.5 inactivated were identified by inability to grow on an E. coli host with an amber suppressor (either O11′ or AB1157), and phage with one or more amber mutations in addition to an insertion in gene 2.5 were identified by inability to grow on suppressor-free strain W3110 that carried a plasmid which expressed wild-type T7 gene 2.5.

DNA.

DNA was purified as described by Richardson (44). DNA concentrations are reported as nucleotide phosphorous equivalents. For reference, 1 nmol of nucleotide corresponds to 7.5 × 109 double-stranded T7 genomes. For most experiments, double strand breaks were placed in the XhoI site engineered at position 6663. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs or from Boehringer Mannheim and used according to the supplier's instructions. DNA homologous to the break site and used to repair the break is referred to as donor DNA. In most cases, BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− DNA was used as donor. The amber mutation in gene 6 and the ss− missense mutation in gene 10 are incidental to these experiments. For repair of double strand breaks at the XhoI site at position 6663, the relevant BstXI fragment extends from positions 3863 to 9626. When 1.5 nmol of BstXI-digested donor DNA was incubated with 1.5 nmol of T7 genomes, each with a double strand break, there is one molecule of the relevant restriction fragment for each double strand break. The 2,136-bp PCR fragment extending from positions 5594 to 7729, which served as donor DNA for some experiments, was prepared as previously described (28). In experiments using the PCR fragment as donor DNA, the number of PCR fragments in a repair reaction was 10 times the number of T7 genomes.

In vitro double strand break repair.

Preparation of extracts for DNA replication and repair and the reaction conditions used have been previously described (14, 34). For the studies reported here, suppressor-free E. coli W3110 (without plasmids containing T7 genes) was used as a host. All T7 phage used for extract preparation contained the ΔA mutation, which avoids homology between the region of the double strand break and any contaminating endogenous DNA that might be in the extracts. Thus, as is evident from the control data shown in the tables, the ΔA mutation renders endogenous DNA a poor source of donor for repair of breaks at the XhoI site. Also, the ΔA mutation reduces the size of the T7 KpnI D fragment by 1.4 kb. This means that when electrophoresis was used to follow double strand break repair, any endogenous DNA in the reactions could not be misinterpreted as re-formation of intact genomes via repair of double strand breaks. All experiments reported here were repeated at least three times with essentially identical results.

In vitro packaging.

For some experiments, the products of the in vitro repair reactions were added to in vitro packaging reactions to convert intact T7 genomes to infective phage. The ratio of the number of phage produced from reactions beginning with broken genomes to the number recovered from identical reactions which started with intact genomes was taken as the repair efficiency. Because of the dilutions associated with buffer changes, 110 pmol of DNA was typically added to the packaging reaction in experiments that began with 1.5 nmol in the repair reactions. This amount of nucleotide could potentially form 8 × 108 infective phage. All repair reactions were evaluated in three separate packaging reactions, and the averages of these values are presented in the tables; because of variations in the extracts used for repair or for packaging, differences of a factor of 2 are not considered significant in these analyses.

Visualization of DNA after electrophoresis.

To evaluate double strand break repair by electrophoresis reaction, volumes of 0.250 ml containing 7.5 nmol of T7 genomes were used. These reaction volumes are five times those used when packaging was employed as an assay. After 15 or 30 min of incubation, the reactions were stopped by chilling in ice. The reaction mixtures were extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol, and the DNA was resuspended in 1/10 volume Tris-EDTA (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.1 mM EDTA). The DNA was treated with boiled bovine pancreas RNase a (final concentration, 1 mg/ml, Calbiochem) and digested with KpnI, and 0.014 ml was subjected to electrophoresis at 24 V for 4 h in a 0.4% agarose gel in Tris acetate-EDTA buffer (28, 29). The gel were stained with ethidium bromide to give the patterns shown in the figures.

RESULTS

T7 proteins are needed for efficient in vitro repair of double strand breaks.

To see whether E. coli enzymes were sufficient for at least some of the double strand break repair in the T7 in vitro system, we attempted repair using extracts from uninfected E. coli. A recB mutation was used to prevent degradation of the linear double-stranded T7 DNA genome in the extracts. Normally, T7 inactivates the recB enzyme soon after infection so as to prevent degradation of its DNA (62). Thus, use of the recB mutation in the uninfected cells should not cloud comparison of experiments that employed extracts from T7-infected E. coli. A double strand break was introduced into the XhoI site of T7 genomes, and these DNA molecules were incubated in repair reactions with either no extract, extracts with uninfected recB E. coli, or extracts made with T7-infected bacteria. Donor DNA was BstXI-digested T7 genomes. Table 1 shows similar recovery of intact genomes whether uninfected extracts or no extract was used. The T7-infected extract gave a significantly higher yield of phage from the intact genomes, because of replication of the genomes during the reactions and because incubation in the T7-infected extracts improves the ability of the phage genomes to be packaged (6). A double strand break reduced yield of viable phage by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude if there was no extract in the reaction or uninfected E. coli was the source of extract. In contrast, an extract made with T7-infected E. coli increased the ability of broken genomes to form infective phage by more than 4 orders of magnitude and showed a repair efficiency of nearly 50%.

TABLE 1.

Host proteins are insufficient for efficient repair of double strand breaks in T7 genomesa

| Extract | Genomic DNA | Donor DNA | Titer | Repairb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Intact | None | 5.9 × 105 | |

| Cut | None | 1.4 × 103 | 0.24 | |

| Intact | + | 5.7 × 105 | ||

| Cut | + | 1.2 × 103 | 0.21 | |

| Uninfected | Intact | + | 4.1 × 105 | |

| Cut | + | 6 × 102 | 0.15 | |

| T7-infected | Intact | + | 2.5 × 107 | |

| Cut | + | 1.2 × 107 | 48 |

T7X DNA was cut with XhoI to place a double strand break in the ligase gene (cut DNA). 1.5 nmol of T7X DNA in the form of intact or cut genomes was incubated in the in vitro repair system with 1.5 nmol of BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− DNA as the donor. The reactions were carried out without extracts, with extracts made from ΔA 3−-infected E. coli, or with extracts made from uninfected E. coli recB. The products of the reactions were packaged and plated on wild-type (suppressor-free) E. coli.

Ratio of phage counts from reactions with cut DNA to those with intact DNA.

To avoid concern that repaired genomes were disproportionately represented in the subset of T7 DNA that was packaged, visual examination was used to look for double strand break repair carried out by extracts made from an uninfected recB host. Double strand breaks were placed in the XhoI site of the T7 genome. This DNA, together with donor DNA, was incubated in the in vitro repair system. After 30 min at 37°C, the reactions were stopped, RNA was removed, and the DNA products were digested with KpnI and subjected to electrophoresis. The KpnI digestion was used to facilitate detection of the repaired band and to facilitate comparison with experiments that used extracts from T7-infected bacteria. As part of the infective cycle, T7 genomes normally form long end-to-end concatemers (50) which make repair of double strand breaks at one point in the genome difficult to detect. Digestion with KpnI separates the concatemers by cutting the T7 genome in five places, producing four detectable fragments as well as two fragments from the ends of the genome which cannot be easily detected (Fig. 1). The KpnI D fragment, which extends from positions 5613 to 9188, includes the site of the double strand break at 6663. Thus, a double strand break will eliminate the 3.6-kb KpnI D fragment and leave instead fragments that are 2.6 and 1.0 kb long. Repair of the double strand break restores the integrity of the KpnI D fragment (28). Experiments like that displayed in Table 1, which used BstXI fragments as donor DNA, proved difficult to interpret because the unused donor DNA was not extensively digested during the course of the experiment and some of the residual BstXI bands run very near the position expected for the KpnI D band. For this reason, we used donor DNA consisting of a 2.1-kb PCR fragment extending from positions 5594 to 7729. Figure 2 shows that with extract from uninfected bacteria, the KpnI D band, diagnostic of completed repair, was not detectable. The 2.6-kb fragment resulting from the XhoI cut in the midst of the KpnI fragment is, however, clearly detectable in the gel together with unused 2.1-kb PCR generated donor DNA. For comparison, we also show a parallel experiment where an extract from T7 ΔA 3−-infected E. coli was used to repair a double strand break as had been documented in our earlier study (28). A KpnI D fragment is clearly visible in lane 2 of Fig. 2, indicating that when T7 enzymes were present the double strand break was fully repaired. The gel in Fig. 2 also demonstrates that the T7 DNA was not being degraded at a higher rate in the uninfected cell extract.

FIG. 1.

Map of the 39,937-bp T7 genome showing all KpnI digestion sites and the unique XhoI site.

FIG. 2.

Visualization of unrepaired double strand breaks in T7 genomes incubated with extracts from an uninfected host. Reactions included T7 genomes with XhoI-cut and donor DNA consisting of a 2.1-kb PCR fragment extending approximately 1 kb on either side of the site of the double strand break in the phage ligase gene. Reactions were performed as detailed in Materials and Methods with extracts from uninfected bacteria or, as a positive control, from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 3− as previously reported (28). Products from the reactions were purified with phenol-chloroform, treated with RNase, cut by KpnI, and subjected to electrophoresis at 24 V for 4 h in a 0.4% agarose gel in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide. Lane M, molecular weight markers consisting of HindIII-digested lambda DNA; lane 1, reaction with uninfected extract from recB E. coli; lane 2, control experiment with an extract from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 3−.

A recA mutation does not block double strand break repair in T7.

Although it is known that T7 does not use the host RecA pathway for homologous recombination of T7 DNA (43), involvement of the host recombinase in phage double strand break repair remained a possibility. We attempted repair of a double strand break in the XhoI site of the T7 genome, using phage-infected extracts of recA E. coli. Table 2 shows experiments where T7 ΔA 3−-infected wild-type and recA E. coli cells were used to prepare extracts for in vitro repair experiments. T7 genomes were either left intact or cut with XhoI to put a double strand break at position 6663. Comparison was made with or without donor DNA, consisting of BstXI fragments of T7 genomes. As seen in the reactions without extract, the double strand break reduced the yield of infective phage by more than 2 orders of magnitude. With donor DNA present, both the wild-type and recA extracts repaired the double strand breaks with good efficiency. Thus, disruption of the major host recombination pathway has no effect on repair of double strand breaks in T7 genomes.

TABLE 2.

E. coli RecA recombinase is not required for repair of double strand breaks in the T7 genomea

| Extract | Genomic DNA | Donor DNA | Titer | Repairb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Intact | None | 1.0 × 106 | |

| Cut | None | 1.8 × 103 | 0.2 | |

| Wild type | Intact | None | 2.6 × 107 | |

| Cut | None | 2.3 × 105 | 0.9 | |

| recA | Intact | None | 2.1 × 107 | |

| Cut | None | 1.9 × 105 | 0.9 | |

| Wild type | Intact | + | 2.8 × 107 | |

| Cut | + | 1.4 × 107 | 50 | |

| recA | Intact | + | 3.2 × 107 | |

| Cut | + | 1.3 × 107 | 41 |

T7X DNA was cut with XhoI to place a double strand break in the ligase gene (cut DNA); 1.5 nmol of T7X DNA in the form of intact or cut genomes was incubated in the in vitro repair system with 1.5 nmol of BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− DNA as the donor. The reactions were carried out without extracts, with extracts made from T7 ΔA 3−-infected E. coli, or with extracts made from T7 ΔA 3−-infected E. coli recA. The products of the reactions were packaged and plated on a wild-type host.

Ratio of phage counts from reactions with cut DNA to those with intact DNA.

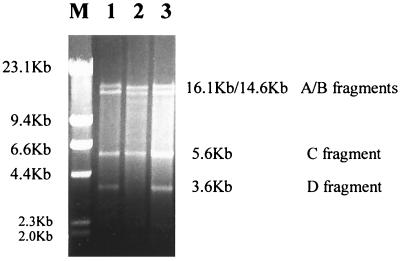

We attempted to visualize the repair of the double strand break using extracts made from T7 ΔA 3−-infected recA E. coli. Extracts were prepared from either wild-type or recA E. coli and used in reactions attempting to repair a double strand break at the XhoI site (Fig. 3). DNA recovered from these reactions was once again digested with KpnI before electrophoresis. The presence of a full-length (3.6-kb) KpnI D band is indicative of restoration of the double strand break at the XhoI site. Figure 3 shows a clear KpnI D band irrespective of whether wild-type E. coli or a recA derivative was used in the in vitro reactions. A control performed without donor DNA does not show the 3.6-kb KpnI D fragment indicating, as expected, that even in the reaction performed with the recA extract, double strand break repair depends on donor DNA.

FIG. 3.

Visualization of T7 genomes repaired without the host RecA recombinase. Both reactions included XhoI-digested T7X DNA and BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− genomes as donor DNA. Reactions were performed using extracts from T7 ΔA3−-infected E. coli recA. Lane M, molecular weight marker HindIII-digested lambda DNA; lane 1, reaction performed with extracts made from T7 ΔA 3−-infected E. coli; lane 2, reaction with extracts made from T7 ΔA3−-infected E. coli recA but with donor DNA omitted from the reaction; lane 3, complete reaction including donor DNA with extracts from T7 ΔA 3−-infected recA E. coli. The presence of a normal-sized (3.6-kb) KpnI D band is diagnostic of repair of the double strand break near position 6663.

T7's gene 2.5 protein is essential for double strand break repair.

We investigated the role of T7 gene 2.5 product, a protein of special interest to recombinational repair because of its apparent role in homologous recombination (1, 24). Properties of the gene 2.5 protein (19) also suggest potential roles in concatemer formation, maturation of T7 genomes, and modulation of DNA degradation. The in vitro packaging system gave abnormally low phage yields even when intact genomes were incubated in extracts missing the gene 2.5 protein (data not shown). Therefore, electrophoresis was used to visually assess repair carried out by extracts missing the gene 2.5 protein. T7 genomes, each with a double strand break in the XhoI site, and donor DNA in the form of T7 BstXI fragments were incubated with extracts made using phage missing the gene 2.5 protein. These reactions (data not shown) did not show extensive degradation of unused donor DNA or unrepaired partial genomes. However, this type of DNA degradation was apparent in our earlier experiments which had been performed using phage that had normal levels of gene 2.5 and gene 6 proteins (28, 29). Since the undigested BstXI fragments obscured detection of the KpnI D fragment that is diagnostic of complete repair, 2.1-kb PCR fragments extending from positions 5594 to 7729 were used in place of the BstXI fragments as donor DNA. Lane 1 in Fig. 4 shows a reaction using extracts from T7 ΔA 2.5− 3− 5− 6−-infected E. coli. Because of the unrepaired break at the XhoI site, a 2.6-kb fragment is seen in place of the normal 3.6-kb KpnI D band. Also, unused 2.1-kb PCR fragments appear in the gel. Thus, deficiencies in both the gene 2.5 and gene 6 products prevented degradation of DNA fragments. Lane 2 of Fig. 4 reveals major DNA degradation, as predicted from our earlier study (28). Lane 4 shows a reaction with all T7 gene products except the gene 2.5 product. The absence of a KpnI D band demonstrates failure to repair the double strand break when the gene 2.5 product is missing. Lanes 5 and 6 show positive controls indicating restoration of the KpnI D fragment in reactions with the gene 2.5 product present. As shown in an earlier study (28), this repair took place irrespective of the presence of T7 DNA polymerase encoded by gene 5. This figure demonstrates that the gene 2.5 protein is required for repair of double strand breaks in T7. Also, the severe DNA degradation apparent when the product of gene 2.5 is missing and the level of gene 6 protein is normal can account for the exceptionally poor phage yield observed when we attempted to measure repair using extracts from gene 2.5-deficient T7 and in vitro packaging as an assay. Apparently, both the gene 2.5 product and the gene 6 product are required for repair of double strand breaks in this in vitro system.

FIG. 4.

Effects of T7 gene 2.5 and gene 6 products on the repair of double-strand breaks. All reactions included XhoI-digested T7X DNA and 2.1-kb PCR fragments as donor. Products from the in vitro reactions were recovered, treated with RNase, digested with KpnI, and subjected to electrophoresis, and the gel was stained as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Lane M, molecular weight markers consisting of HindIII-digested lambda DNA; lane 1, reaction with extracts made from T7 ΔA 2.5− 3− 5− 6−-infected E. coli; lane 2, reaction with extracts made from T7 ΔA 2.5− 3−-infected E. coli; lane 3, reaction with T7 ΔA 3− 5− 6−-infected E. coli; lane 4, reaction with a 9:1 mixture of extracts from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 2.5− 3− 5− 6− or T7 ΔA 2.5− 3−; lane 5, a reaction with a 9:1 mixture of extracts from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 3− 5− 6− or T7 ΔA 2.5− 3−; lane 6, reaction with a 9:1 mixture of extracts from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 3− 5− 6− or T7 ΔA 3− 5−.

T7 helicase/primase is not required for double strand break repair.

As noted above, although the gene 2.5 protein can facilitate annealing between complementary single strands of DNA, efficient strand transfer depends on the unwinding activity of the helicase coupled with the annealing activity of the gene 2.5 protein (8, 23, 24). With this in mind, we examined double strand break repair using extracts deficient in the gene 4 protein. Extracts were prepared from E. coli infected with T7 ΔA 3− 4− and used in reactions with BstXI fragments as donor DNA and genomes that were intact or had a double strand break at the XhoI site. Figure 5 shows a KpnI digest of the product of reactions incubated with (lane 1) or without (lane 2) donor DNA. The reaction with donor DNA clearly shows a D band after KpnI digestion, thereby demonstrating complete repair of the genomes. In the reactions without donor DNA, the failure to detect the KpnI D band was qualified by poor recovery of the broken genomes. This same problem persisted in several repeats of this experiment, leading us to suspect that genomes that are not repaired suffer substantial degradation in this in vitro system. However, the gel displayed in Fig. 5 leaves little doubt that repair of the double strand breaks proceeded despite the deficiency in the gene 4 helicase.

FIG. 5.

Visualization of DNA repaired without T7 gene 4 helicase/primase. Both reactions included XhoI-digested T7X DNA and the extracts made from T7 ΔA 3− 4−-infected E. coli. The reaction in lane 1 included BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− DNA as donor. Reaction products were treated with RNase and KpnI and subjected to electrophoresis as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Lane M, HindIII-digested lambda DNA; lane 1, products of the complete reaction; lane 2, reaction missing donor DNA.

To obtain a more quantitative determination of repair efficiency, the product of repair reaction performed without normal levels of the gene 4 product were packaged in vitro. When neither extract nor donor DNA was present, the double strand break caused infectivity of the product to drop by nearly 3 orders of magnitude. In the presence of extract from T7 ΔA 3− 4− E. coli, the double strand break still caused a more than 300-fold reduction in phage yield if donor DNA was omitted from the reactions. With the complete reaction mixture, highly efficient repair (38%) was achieved. Thus, the data in Table 3 agree well with the results in Fig. 5 and argue that normal levels of the gene 4 helicase are not critical to repair of double strand breaks. It was possible that the RecA recombinase could mediate recombinational repair when the gene 4 protein was inactivated. Extracts were made with an E. coli recA host infected with T7 ΔA 3− 4− phage, and these extracts were compared with wild-type bacteria infected with the same T7 mutant. As seen in Table 3, a recA mutation in the host does not significantly affect the efficiency of repair (27% versus 38%), arguing that RecA-mediated strand transfer reactions do not come into play when the helicase-annealing protein pathway of the phage is inhibited by a gene 4 mutation.

TABLE 3.

T7 gene 4 product (helicase/primase) is not required for efficient double strand break repaira

| Extract | Genomic DNA | Donor DNA | Titer | Repairb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Intact | None | 1.7 × 105 | |

| Cut | None | 2.7 × 102 | 0.2 | |

| Wild type | Intact | None | 8.9 × 106 | |

| Cut | None | 2.5 × 104 | 0.3 | |

| recA | Intact | None | 7.5 × 106 | |

| Cut | None | 6.6 × 104 | 0.9 | |

| Wild type | Intact | + | 8.7 × 106 | |

| Cut | + | 3.3 × 106 | 38 | |

| recA | Intact | + | 9.4 × 106 | |

| Cut | + | 2.5 × 106 | 27 |

T7X DNA was digested with XhoI to place a double strand break in the ligase gene (cut DNA); 1.5 nmol of T7X DNA in the form of intact or cut genomes was incubated in the in vitro repair system with 1.5 nmol of BstXI-digested T7 6− ss− DNA as donor. The reactions were carried out without extracts or with extracts made from either T7 ΔA 3− 4−-infected E. coli wild-type or T7 ΔA 3− 4−-infected E. coli recA. Reaction products were packaged and plated on wild-type E. coli.

Ratio of phage counts from reactions with cut DNA to those with intact DNA.

DISCUSSION

Under conditions where the major DNA replication pathway is blocked, T7 repairs double strand breaks by inserting fragments of donor DNA into a gap created at the break site (29). Recombination in the region of overlap between the donor DNA and the partial genomes created by the double strand break could be mediated by either E. coli or T7 proteins. E. coli maintains an array of mechanisms dedicated to repair of double strand breaks (12, 21, 60), and there is no a priori reason why the host pathways should not operate equally well on T7 DNA. Therefore, we considered the possibility that some fraction of the double strand break repair events were carried out exclusively by E. coli repair pathways. But the data in Table 1 suggest that extracts prepared from uninfected E. coli, prepared in the same way as the extracts from T7-infected cells, were incapable of repairing double strand breaks in this in vitro system. No enzyme capable of strand invasion has been identified in T7-infected E. coli. RecA does not appear to play a role in T7 recombination (43). This could be because T7 infection somehow blocks RecA activity on T7 DNA or, as seems more likely, the level of phage-mediated recombinational exchange is so high that host protein contributions to this process are inconsequential. Keeping in mind the possibility that homologous recombination and recombinational repair of double strand breaks may not necessarily proceed by identical mechanisms, we tested for RecA involvement in T7 double strand break repair. Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 3 show that a recA mutation in the host does not reduce the efficiency of T7 double strand break repair. Thus, our data show that T7-encoded proteins are essential to the highly efficient double strand break repair carried out by this in vitro system.

Previous in vivo (1, 17, 31, 43) and in vitro (47, 48) studies have implicated a number of T7 proteins in homologous recombination. These include the products of gene 2.5 (single strand binding protein), gene 3 (endonuclease), gene 4 (helicase/primase), gene 5 (DNA polymerase), and gene 6 (5′→3′ exonuclease). The gene 6 product is essential to double strand break repair (28), but amber mutations in either the gene 3 endonuclease or the phage DNA polymerase encoded by gene 5 have essentially no effect on that repair mode (28, 30). In this study, we considered the roles of the products of T7 gene 2.5 and gene 4, proteins which collaborate in strand transfer reactions during homologous recombination. Given the central role of the gene 2.5 protein in T7 DNA replication and recombination, the finding (Fig. 4) that the gene 2.5 product is required for repair of double strand breaks could derive from any of several causes. Deficiencies in T7 gene 2.5 protein block DNA replication fork progression (18). However, our finding that double strand break repair proceeds normally in spite of a mutation in the structural gene for T7 DNA polymerase (28) argues against disruption of DNA replication as the primary cause of the repair defect associated with inactivation of the gene 2.5 protein. The gene 2.5 protein engages in protein-protein interactions with both the T7 gene 4 helicase/primase and the gene 5 DNA polymerase (20, 35). Moreover, interactions between the gene 2.5 protein and the gene 4 helicase permit a highly efficient strand transfer reaction which doubtlessly figures prominently in T7 homologous recombination (20, 23, 24, 35). However, these protein-protein interactions are unlikely to be responsible for the severe deficiency in double strand break repair reported here. Previously we reported that double strand break repair proceeds unabated in extracts made with T7 gene 5 mutants (28), thus arguing that one member of the gene 2.5 protein-DNA polymerase partnership is nonessential for double strand break repair. Furthermore, the finding that gene 4 is not essential to T7 double strand break repair (Table 3; Fig. 5) suggests that disruption of a strand transfer reaction is not likely to be the cause of the gene 2.5-associated failure of recombinational repair apparent in Fig. 4. In other biological systems, a critical role of single strand DNA binding protein is to protect exposed single-stranded DNA from nuclease attack (2). In T7 the single strand binding protein enhances the activity of gene 6 exonuclease so that apparent nuclease degradation is actually more pronounced with the gene 2.5 protein than without it (46). Thus, available data provide no evidence to suggest that excessive DNA degradation causes the inhibition of recombinational repair associated with gene 2.5 inactivation. Nonetheless, it is possible that the gene 2.5 protein may protect repaired genomes or intermediates generated during the repair process from degradation by nucleases. The gene 2.5 protein's ability to facilitate annealing of complementary single strands of DNA may explain that protein's critical role in recombination and double strand break repair. If so, single strand annealing alone, without strand transfer, is adequate to account for the remarkably efficient repair of double strand breaks carried out by this in vitro system.

In T7, combined action of the gene 4 helicase and gene 2.5 annealing activity provides an effective means of strand exchange (24). However, data in Table 3 and Fig. 5 do not support crucial involvement of the gene 4 protein in the recombination repair mechanism described here. T7's gene 4 produces two proteins (4A and 4B) due to an internal ribosome binding site 189 nucleotides from the beginning of full-length (1,698-nucleotide) gene 4A (8). The larger gene 4 product (63,000 Da) constitutes a primase and helicase, while the smaller protein (56,000 Da) is only the helicase (45). The amber mutation in gene 4 used in the present study is located within the coding region for both 4A and 4B proteins (56), and both the 56,000- and 63,000-Da peptides are missing after this mutant infects E. coli (13, 54). Thus, the gene 4 amber mutant is deficient in T7 both helicase and primase. As with any amber mutation, low levels of gene 4 product might persist in extracts made with T7 ΔA 3− 4−. However, even though the gene 4 mutation is severe enough to prevent phage growth in the absence of an amber suppressor, data in Table 3 show no significant reduction in double strand break repair performed by extracts made with a gene 4 mutant.

Both the exonuclease encoded by gene 6 and the single strand DNA binding protein encoded by gene 2.5 are required for repair of double strand breaks in T7. It is possible that the products of gene 2.5 and gene 6 together with host ligase might even be sufficient for some of the repair events. A single strand annealing mechanism predominates in this type of repair. The exonuclease activity could serve to produce single strand ends at the break sites and on the ends of the donor DNA. Annealing of these sequences, facilitated by the gene 2.5 protein, could then join the DNA molecules together and thereby repair the break. Although single strand annealing provides an attractive model with which to explain the data presented here, certain cautions need to be kept in mind when this model is applied to in vivo double strand break repair in T7. Both the mutation in gene 2.5 and the one in gene 4 interfere with normal DNA replication, and although double strand break repair proceeds with good efficiency without extensive DNA replication, these data do not rule out the possibility that in wild-type T7, where rapid and extensive DNA replication is the norm, a mode of recombinational repair involving DNA replication might predominate. In fact, it is possible that degradation of T7 chromosomes may be more pronounced when those DNA molecules are not actively being replicated. Also, the donor DNA molecules used in these studies are only a few kilobases long, and thus degradation or unwinding from the ends may make these DNA fragments particularly good substrates for a single strand annealing mechanism of recombination. Thus, the design of the in vitro experiments may exaggerate the contribution of a single strand annealing mechanism to T7 recombination. A mechanism requiring substantial degradation of the ends of double-stranded DNA means that shunning the host's RecA system exacts a high cost in economy for the phage since regions of existing genomes must be sacrificed to provide patches for broken genomes. Nonetheless, such a mechanism is a plausible means of generating intact T7 genomes from an array of partial genomes, especially if double strand breaks and consequential formation of arrays of overlapping partial genomes are a frequent occurrence during a T7 infection. An alternative, albeit speculative, possibility is that one of the T7 proteins whose function has not yet been identified (8) may act to promote strand invasion and associated recombination that could insert homologous DNA into a break site with need for only limited DNA replication. Moreover, the fact that host proteins are not sufficient for the high level of double strand break repair seen in these experiments does not imply that no host protein plays a role in T7 recombination. It is possible that one or more of the host helicases could help, perhaps in conjunction with the gene 2.5 protein, to mediate a strand transfer reaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. T. Kim and C. Richardson for the T7 gene 2.5 mutants and Mary Ann Crissey for construction of the ΔA 2.5− 3− 5− 6− and ΔA 2.5− 3− phage.

This work was supported by Public Health Service research grant GM-55278 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araki H, Ogawa H. The participation of T7 DNA-binding protein in genetic recombination. Virology. 1981;111:509–515. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chase J W, Williams K. Single-stranded binding proteins required for DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:103–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox M M. Recombinational DNA repair in bacteria and the RecA protein. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1999;63:311–366. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox M M, Goodman M F, Kreuzer K N, Sherratt D J, Sandler S J, Marians K J. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature. 2000;404:37–41. doi: 10.1038/35003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMassay R, Weisberg R A, Studier F W. Gene 3 endonuclease of bacteriophage T7 resolves conformationally branched structures in double stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:359–376. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodson L A, Foote R S, Mitra S, Masker W E. Mutagenesis of bacteriophage T7 in vitro by incorporation of O6-methyguanine during DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7440–7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doublie S, Tabor S, Long A M, Richardson C C, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of a bacteriophage T7 DNA replication complex at 2.2 A resolution. Nature. 1998;391:251–258. doi: 10.1038/34593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn J J, Studier F W. The complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage T7 DNA and the locations of T7 genetic elements. J Mol Biol. 1983;266:477–535. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrlich S D, Bierne H, d'Alencon E, Vilette D, Petranovic M, Noirot P, Michel B. Mechanisms of illegitimate recombination. Gene. 1993;135:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.George J W, Kreuzer K. Repair of double-strand breaks in bacteriophage T4 by a mechanism that involves extensive DNA replication. Genetics. 1996;143:1507–1520. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haber J E. DNA recombination: the replication connection. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinkle D C, Richardson C C. Bacteriophage T7 deoxyribonucleic acid replication in vitro. Purification and properties of the gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:5523–5529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinkle D C, Richardson C C. Bacteriophage T7 deoxyribonucleic acid replication in vitro. Requirements for deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and characterization of the product. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:2974–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeggo P A. DNA breakage and repair. Adv Genet. 1998;38:185–218. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson K A. Conformational coupling in DNA polymerase fidelity. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:685–713. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr C, Sadowski P D. The involvement of genes 3, 4, 5, and 6 in genetic recombination in bacteriophage T7. Virology. 1975;65:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y T, Richardson C C. Bacteriophage T7 gene 2.5 protein: an essential protein for DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10173–10177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y T, Tabor S, Bortner C, Griffith J C, Richardson C C. Purification and characterization of the bacteriophage T7 gene 2.5 protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15022–15031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y T, Tabor S, Churchich J E, Richardson C C. Interactions of gene 2.5 protein and DNA polymerase of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15032–15040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi I. Mechanisms for gene conversion and homologous recombination: the double-strand break repair model and successive half crossing-over model. Adv Biophys. 1992;28:81–133. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(92)90023-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kogoma T. Stable DNA replication: interplay between DNA replication, homologous recombination, and transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:212–238. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.212-238.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong D, Nossal N G, Richardson C C. Role of the bacteriophage T7 and T4 single-stranded DNA-binding proteins in the formation of joint molecules and DNA helicase-catalyzed polar branch migration. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8380–8387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong D, Richardson C C. Single stranded DNA binding protein and DNA helicase of bacteriophage T7 mediate homologous strand exchange. EMBO J. 1996;15:2010–2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuzer K N. Recombination-dependent DNA replication in phage T4. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzminov A. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:751–813. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.751-813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuzminov A, Stahl F W. Double-strand end repair via the RecBC pathway in Escherichia coli primes DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1999;13:345–356. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai Y, Masker W. Visualization of repair of double strand breaks in the bacteriophage T7 genome without normal DNA replication. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:327–336. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.327-336.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai Y T, Masker W. Repair of double strand breaks by incorporation of a molecule of homologous DNA. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:437–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai Y-T, Masker W. In vitro repair of gaps in bacteriophage T7 DNA. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6193–6302. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6193-6202.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M, Miller R C J, Scraba D, Paetkau V. The essential role of bacteriophage T7 endonuclease (gene3) in molecular recombination. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:883–888. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marians K J. PriA: at the crossroads of DNA replication and recombination. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2000;63:39–67. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masker W. In vitro repair of double-strand breaks accompanied by recombination in bacteriophage T7 DNA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:155–160. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.155-160.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masker W E, Kuemmerie N B, Allison D P. In vitro packaging of bacteriophage T7 DNA synthesized in vitro. J Virol. 1978;27:149–163. doi: 10.1128/jvi.27.1.149-163.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendelman L V, Notarnicola S M, Richardson C C. Roles of bacteriophage T7 gene 4 proteins in providing primase and helicase functions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10638–10642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosig G. Recombination and recombination-dependent DNA replication in bacteriophage T4. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:379–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers R C, Stahl F W. Chi and the RecBCD enzyme of Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:49–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paques F, Haber J E. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pastink A, Lohman P H M. Repair and consequences of double-strand breaks in DNA. Mutat Res. 1999;428:141–156. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel S S, Rosenberg A H, Studier F W, Johnson K A. Large scale purification and biochemical characterization of T7 primase/helicase proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15013–15021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierce J C, Masker W E. Genetic deletions between directly repeated sequences in bacteriophage T7. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:215–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02464884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powling A, Knippers R. Recombination of bacteriophage T7 in vivo. Mol Gen Genet. 1976;149:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00275961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powling A, Knippers R. Some functions involved in bacteriophage T7 genetic recombination. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;134:173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00268418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richardson C C. The 5′-terminal nucleotides of bacteriophage T7 deoxyribonucleic acid. J Mol Biol. 1966;15:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson C C. Bacteriophage T7: minimal requirements for the replication of a duplex DNA molecule. Cell. 1983;33:335–337. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts L, Sadowski P, Wong J T-F. Specific stimulation of the T7 gene 6 exonuclease by the phage T7 coded deoxyribonucleic acid binding protein. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6000–6005. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roeder G S, Sadowski P D. Pathways of recombination of bacteriophage T7 DNA in vitro. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1978;43:1023–1032. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1979.043.01.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadowski P D, Bradley W, Lee D, Roberts L. Genetic recombination of bacteriophage T7 DNA in vitro. In: Alberts B, Fox C F, editors. Molecular mechanisms of replication and genetic recombination. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 941–952. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawaya M R, Guo S, Tabor S, Richardson C C, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of the helicase domain from the replicative helicase-primase of bacteriophage T7. Cell. 1999;99:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serwer P. Fast-sedimenting DNA from T7-infected Escherichia coli. Virology. 1974;59:70–88. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimizu K, Araki H, Ogawa H. Suppression of bacteriophage T7 ssb mutation with host ssb. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:926–931. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Homologous recombination and the roles of double strand breaks. Trends Exp Biochem. 1995;20:387–391. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stahl F. Meiotic recombination in yeast: coronation of the double-strand-break repair model. Cell. 1996;87:965–968. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81791-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Studier F W. Bacteriophage T7. Science. 1972;176:367–376. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4033.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Studier F W. The genetics and physiology of bacteriophage T7. Virology. 1969;39:562–574. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H. Genetic and physical mapping of the late region of bacteriophage T7 DNA by use of cloned fragments of T7 DNA. J Mol Biol. 1981;153:503–525. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szostak J W, Orr-Waever T L, Rothstein R, Stahl F W. The double strand break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabor S, Huber H E, Richardson C C. Escherichia coli thioredoxin confers processivity on the DNA polymerase activity of the gene 5 protein of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1987;258:16212–16223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tabor S, Richardson C C. Selective inactivation of the exonuclease activity of bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase by in vitro mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6447–6458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi N, Kusano K, Yokochi T, Kitamura Y, Yoshikura H, Kobayashi I. Genetic analysis of double strand break repair in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5176–5185. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5176-5185.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thaler D S, Stahl F W. DNA double-chain breaks in recombination of phage lambda and of yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:169–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wackernagel W, Hermans U. Inhibition of exonuclease V after infection of E. coli by bacteriophage T7. Virology. 1974;65:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]