Abstract

Although traumatic cervical spine injuries in older adults are commonly caused by minor traumas, such as ground-level falls, their prognosis is often unfavorable. Studies examining the clinical characteristics of cervical spine injuries in older adults according to the external cause of injury are lacking. This study included 1512 patients of ≥ 65 years of age with traumatic cervical spine injuries registered in a Japanese nationwide multicenter database. The relationship between the external causes and clinical characteristics, as well as factors causing unfavorable outcomes at the ground-level falls, were retrospectively reviewed and examined. When fall-induced cervical spine injuries were categorized and compared based on fall height, the patients’ backgrounds and injury statuses differed significantly. Of note, patients injured from ground-level falls tended to have poorer pre-injury health conditions, such as medical comorbidities and frailty, compared with those who fell from higher heights. For ground-level falls, the mortality, walking independence, and home-discharge rates at 6 months post-injury were 9%, 67%, and 80%, respectively, with preexisting medical comorbidities and frailty associated with unfavorable outcomes, independent of age or severity of neurological impairment at the time of injury.

Subject terms: Medical research, Geriatrics, Trauma

Introduction

The global percentage of individuals aged 65 years and over increased from 6% in 1990 to 9% in 2019 and is projected to rise further to 16% by 2050, with one in six people worldwide aged ≥ 65 years1. Japan has the highest aging rate worldwide, with 29% of the population aged ≥ 65 years in 2021, which is approximately one-third of the entire Japanese population2.

The number of traumatic injuries in older people has also been rising, and injuries due to falls are a serious public health concern in aging societies3,4. Approximately 30% of community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older fall at least once a year, with the frequency of falls increasing with age5,6. Approximately 10% of all falls result in serious injuries among older people, and cervical spine injury is one of the most severe injuries with high morbidity and mortality rates7,8. Fall-induced cervical spine injuries are likely to occur even with relatively minor trauma in older people, and the incidence is increasing in developed countries9–12.

The World Health Organization categorizes falls into four patterns: (1) falls from ground-level, (2) falls from heights of less than one meter, (3) falls from heights of one meter or more, and (4) being struck or crushed by a falling object13. This categorization suggests that clinical characteristics may vary depending on the fall height, even for the same fall-induced injury. There have been a few reports addressing the differences in the clinical characteristics of spinal cord injuries depending on the fall height14,15; however, there is a lack of studies on the clinical characteristics, including prognoses, in cohorts of older patients with traumatic cervical spine injury based on the external cause of injury with a focus on the fall height. Furthermore, the causes of poor prognoses with minor injuries in older people, such as due to a fall from ground level, have not been clarified.

In this study, a nationwide survey of cervical spine injuries in Japan's hyper-aging population was conducted, with the aim of answering the following questions: (1) To what extent do clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes differ by the external cause of injury, particularly by fall height? and (2) What are the unfavorable prognostic factors in cases of ground-level falls, the most common form of trauma? This nationwide survey would provide important evidence to prevent cervical spine injuries and improve their prognosis of in older adults in a rapidly aging society.

Methods

Study design

Data from patients of ≥ 65 years of age at the time of injury who had traumatic cervical spine injuries between 2010 and 2020 and had been registered in the multicenter database of the Japan Association of Spine Surgeons with Ambition were retrospectively analyzed. Cervical spine injuries included cervical fractures, dislocations, spinal cord injuries, and the combinations thereof. The criteria for enrollment in the database were patients who required in-hospital treatment and had at least 3 months of follow-up. Patient data were collected from medical records and imaging data. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University Hospital, an institutional review board of the representative facility in this multicenter study (no. 3352-1). Informed consent was obtained in the form of an opt-out procedure at each institute, and patients who declined to participate were excluded. This study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Variables, classifications, and outcomes

Variables included the external cause of injury, pre-injury patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index, residence status, walking ability, medical comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]16, number of medications, modified 5-item frailty index [mFI-5], and presence of cervical ligamentous ossification), blood tests on admission (total protein and hemoglobin), injury status (presence of cervical fracture/dislocation, neurological impairment, and associated injury), and treatment status (steroid administration and surgery). The mFI-5 is a surrogate index for frailty, which is calculated based on the number of applicable items in the five categories of activities of daily living. These include requiring assistance and the presence of hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease17,18. Neurological impairment was assessed using the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS)19. External causes of injury were classified as falling from the ground level, falling from heights below 1 m (low fall), falling from heights above 1 m (high fall), traffic accidents, and others (including those with unspecified reasons). In addition, external causes were examined by age, and patients were divided into three age groups as follows: 65–75 years, 75–85 years, and ≥ 85 years of age. The outcomes of interest were mortality, complication rate (respiratory impairment, dysphagia, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction, and delirium), walking independence rate, and home-discharge rate (returned home, admitted to a facility, or in hospital including rehabilitation hospital) at 6 months post-injury. Six months of follow-up data were available for 79% of the cases. The home-discharge rate was applicable for patients who lived at home before the injury, and the walking independence rate was applicable for patients who could walk independently before the injury. Independent walking was defined as the possibility of walking with or without a cane without any assistance from a physiotherapist.

Statistical analysis

The differences in each parameter and outcome based on the fall height were analyzed using the Cochran–Armitage test or Jonckheere–Terpstra test for trend. For patients injured from ground-level falls, multivariate analyses were performed using forward stepwise logistic regression (likelihood ratio) to identify the prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes, including mortality, walking disability, and difficulty in home discharge. The explanatory variables were the following key parameters that have been reported to impact the prognosis of cervical spine injuries20–24: age at injury, sex, preexisting medical comorbidities (CCI), frailty (mFI-5), presence of cervical fracture/dislocation, neurological impairment upon injury (AIS; E:0, D:1, C:2, B:3, A:4), and the presence of an associated injury. The variables were entered in blocks according to the dimensions of each explanatory variable. The P-value was set to < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 23; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and JMP software (Version 16.1.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

External causes of injury

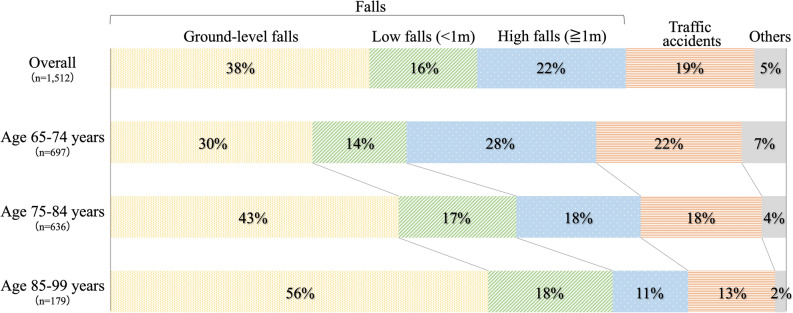

In total, 1512 patients with traumatic cervical spine injuries were identified in our database during the study period from 78 institutions throughout Japan. The most common cause of injury was ground-level falls (38%), followed by high falls (22%), traffic accidents (19%), low falls (16%), and others (5%); thus, three-quarters of all injuries were caused by falls. The proportion of ground-level falls increased with age, and more than half of the patients aged 85 years and older were injured by falls from ground level (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

External causes of injury by age group.

Patient characteristics by the external cause of injury

The mean age of the patients studied was approximately 75.8 years, and on average, patients who were injured from a fall were relatively older than others. Two-thirds of the total number of patients were men, with a higher proportion of women in patients of injuries due to traffic accidents than in others. More than 95% of patients were living at home and walking independently before the injury. Overall, most patients had some underlying health condition, and the prevalence of each condition was relatively higher in patients who had fallen, with a mean CCI > 4. The mean mFI-5 was slightly lower in the patients injured during traffic accidents. Blood test data at the time of admission, including mean serum total protein and hemoglobin, showed little difference according to the cause of injury. A radiological examination showed that 22% of patients had ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), and 13% had diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) in the cervical spine. These rates were relatively higher in patients who were injured by falls than in others. Cervical bony injuries (fractures and/or dislocations) were found in 59% of the patients, of which half had associated spinal cord injuries, and 41% had cervical spinal cord injuries without bony injuries. In patients who were injured in traffic accidents, cervical bony injuries were frequently observed; in contrast, patients who were injured from falling were likely to sustain cervical spinal cord injury without bony injuries, with the majority showing AIS grade C or D. Associated injuries were observed in a quarter of the patients, and head trauma was relatively common. Multiple injuries were more frequent with traffic accidents. Regarding treatment, surgery was performed in approximately 60% of patients, both those injured during falls and those injured in traffic accidents (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by the external cause of injury.

| Overall (n = 1512) | Falls (n = 1153) | Traffic accidents (n = 287) | Others (including unspecified) (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-injury patient demographics | ||||

| Mean age at injury (years) | 75.8 | 76.2 | 74.8 | 73.2 |

| Sex: men, n (%) | 1007 (66.6) | 782 (67.8) | 166 (57.8) | 59 (81.9) |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.1 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 22.3 |

| Residence status: home, n (%) | 1439 (97.0) | 1093 (96.3) | 276 (99.3) | 70 (100) |

| Walking capacity: walking w/ or w/o a cane, n (%) | 1431 (95.5) | 1084 (94.8) | 281 (98.6) | 66 (94.3) |

| Mean Charlson comorbidity index | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Mean number of medications | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 3.9 |

| Mean modified 5-item frailty index | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Presence of cervical ligamentous ossification | ||||

| OPLL, n (%) | 332 (22.0) | 270 (23.4) | 45 (15.7) | 17 (23.6) |

| OLF, n (%) | 25 (1.7) | 21 (1.8) | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| DISH, n (%) | 189 (12.5) | 156 (13.6) | 24 (8.4) | 9 (12.5) |

| Injury status | ||||

| Cervical vertebral fracture, n (%) | 834 (55.2) | 595 (51.6) | 198 (69.0) | 41 (56.9) |

| Cervical dislocation, n (%) | 229 (15.2) | 162 (14.1) | 59 (20.6) | 8 (11.1) |

| Spinal cord injury, n (%) | 1056 (69.8) | 835 (72.4) | 171 (59.6) | 50 (69.4) |

| w/ bony injury, n (%) | 441 (29.2) | 321 (27.8) | 97 (33.8) | 23 (31.9) |

| w/o bony injury, n (%) | 615 (40.7) | 514 (44.6) | 74 (25.8) | 27 (37.5) |

| ASIA impairment scale | ||||

| A, n (%) | 125 (8.3) | 96 (8.4) | 23 (8.0) | 6 (8.3) |

| B, n (%) | 68 (4.5) | 57 (5.0) | 8 (2.8) | 3 (4.2) |

| C, n (%) | 336 (22.3) | 266 (23.2) | 52 (18.2) | 18 (25.0) |

| D, n (%) | 519 (34.5) | 409 (35.7) | 87 (30.4) | 23 (31.9) |

| Associated injuries, n (%) | 411 (27.2) | 269 (23.3) | 134 (46.7) | 8 (11.1) |

| Treatment status | ||||

| Surgery implementation, n (%) | 903 (59.7) | 676 (58.6) | 174 (60.6) | 53 (73.6) |

Records with unknown or missing values were excluded from the analysis.

OPLL Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, OLF Ossification of the ligamentum flavum, DISH Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association.

Patient outcomes at 6 months post-injury by the external cause of injury

The overall mortality rate was 7%, with a rate of 8% for patients in fall accidents and 7% for those in traffic accidents. The overall complication rate was 36%, with relatively high incidences of respiratory impairment, dysphagia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and delirium. The overall walking independence rate and home-discharge rate were 73% and 82%, respectively, and 14% of the patients were still hospitalized after 6 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes at 6 months post-injury by the external cause of injury.

| Overall | Falls | Traffic accidents | Others (including unspecified) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality and complication rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsa | 1198 | 909 | 227 | 62 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 89 (7.4) | 70 (7.7) | 16 (7.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Complications, n (%) | 423 (36.4) | 328 (37.2) | 74 (34.1) | 21 (33.9) |

| Respiratory impairment, n (%) | 81 (6.8) | 61 (6.8) | 16 (7.1) | 4 (6.5) |

| Dysphagia, n (%) | 81 (6.8) | 64 (7.1) | 14 (6.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Deep venous thrombosis, n (%) | 20 (1.7) | 14 (1.6) | 5 (2.2) | 1 (1.6) |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 6 (0.5) | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 115 (9.7) | 93 (10.3) | 16 (7.1) | 6 (9.7) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 110 (9.2) | 83 (9.2) | 17 (7.5) | 10 (16.1) |

| Cerebral infarction, n (%) | 13 (1.1) | 10 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Delirium, n (%) | 95 (8.0) | 72 (8.0) | 19 (8.4) | 4 (6.5) |

| Walking independence rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsb | 1057 | 795 | 206 | 56 |

| Walking capacity: walking w/ or w/o a cane, n (%) | 768 (72.7) | 572 (71.9) | 155 (75.2) | 41 (73.2) |

| Home-discharge rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsc | 1,061 | 801 | 203 | 57 |

| Returned to home, n (%) | 857 (81.5) | 650 (81.1) | 159 (78.3) | 48 (84.2) |

| Admitted to a facility, n (%) | 61 (5.8) | 48 (6.0) | 11 (5.4) | 2 (3.5) |

| In hospital, n (%) | 143 (13.6) | 103 (12.9) | 33 (16.2) | 7 (12.3) |

Records with unknown or missing values were excluded from the analysis.

aPatients with a 6-month follow-up.

bPatients who were able to walk with or without a cane before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding any mortality case.

cPatients living at home before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding mortality cases.

Association between patient characteristics and fall height

The results showed a negative correlation between fall height and the following pre-injury patient demographics: age at injury, proportion of women, not living at home, assisted walking, CCI, number of medications, mFI-5, and incidence of cervical ligament ossification (OPLL and DISH). Patients who fell from ground level tended to have a significantly higher prevalence of preexisting medical comorbidities, such as dementia, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis; their mean medication number was > 4. The higher the fall height, the higher the incidence of cervical bony injuries, including vertebral fractures and/or dislocations; in contrast, the lower the fall height, the higher the incidence of cervical spinal cord injury without bony injuries. The neurological impairment (AIS) at the time of injury was not significantly associated with the fall height. The incidence of associated injuries was positively correlated with the fall height. There was no correlation between the surgical implementation rate and fall height (Table 3, Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Association between patient characteristics and fall height.

| Ground-level falls (n = 579) | Low falls (< 1 m) (n = 241) | High falls (≧1 m) (n = 333) | P-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-injury patient demographics | ||||

| Mean age at injury (years) | 77.5 | 76.5 | 73.9 | < 0.001* |

| Sex: men, n (%) | 384 (66.3) | 147 (61.0) | 251 (75.4) | 0.01* |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.0 | 21.9 | 22.4 | 0.17 |

| Residence status: home, n (%) | 534 (93.9) | 235 (97.9) | 324 (99.4) | < 0.001* |

| Walking capacity: walking w/ or w/o a cane, n (%) | 522 (90.9) | 230 (97.1) | 332 (100.0) | < 0.001* |

| Mean Charlson comorbidity index | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | < 0.001* |

| Mean number of medications | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3 | < 0.001* |

| Mean modified 5-item frailty index | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | < 0.001* |

| Presence of cervical ligamentous ossification | ||||

| OPLL, n (%) | 165 (28.5) | 43 (17.8) | 62 (18.7) | < 0.001* |

| OLF, n (%) | 11 (1.9) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (1.5) | 0.69 |

| DISH, n (%) | 104 (18.0) | 26 (10.8) | 26 (7.8) | < 0.001* |

| Injury status | ||||

| Cervical vertebral fracture, n (%) | 238 (41.1) | 139 (57.7) | 218 (65.5) | < 0.001* |

| Cervical dislocation, n (%) | 50 (8.6) | 41 (17.0) | 71 (21.3) | < 0.001* |

| Spinal cord injury, n (%) | 453 (78.2) | 158 (65.6) | 224 (67.3) | < 0.001* |

| w/ bony injury, n (%) | 127 (21.9) | 68 (28.2) | 126 (37.8) | < 0.001* |

| w/o bony injury, n (%) | 326 (56.3) | 90 (37.3) | 98 (29.4) | < 0.001* |

| ASIA impairment scale | ||||

| A, n (%) | 37 (6.4) | 24 (10.0) | 35 (10.6) | 0.12 |

| B, n (%) | 28 (4.9) | 15 (6.2) | 14 (4.3) | |

| C, n (%) | 145 (25.2) | 48 (19.9) | 73 (22.2) | |

| D, n (%) | 240 (41.7) | 71 (29.5) | 98 (29.8) | |

| Associated injuries, n (%) | 80 (13.8) | 64 (26.6) | 125 (37.5) | < 0.001* |

| Treatment status | ||||

| Surgery implementation, n (%) | 334 (57.7) | 137 (56.9) | 205 (61.6) | 0.27 |

Records with unknown or missing values were excluded from the analysis.

OPLL Ossificationof the posterior longitudinal ligament, OLF Ossification of the ligamentum flavum, DISH Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association.

*Statistically significant trend between the levels of fall height in the Cochran–Armitage test or Jonckheere–Terpstra test.

Association between outcomes at 6 months post-injury and fall height

For patients who were injured from ground-level falls, the mortality, walking independence, and home-discharge rates at 6 months post-injury were 9%, 67%, and 80%, respectively. Mortality was higher in patients who were injured at lower fall heights. Patients who fell from ground level tended to have higher complication rates, but there was no significant trend associated with the fall height. The independent walking rate was negatively correlated with the fall height. There was no significant difference in the home-discharge rates (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between outcomes at 6 months post-injury and fall height.

| Ground-level falls | Low falls (< 1 m) | High falls (≧1 m) | P-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality and complication rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsa | 449 | 198 | 262 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 40 (8.9) | 18 (9.1) | 12 (4.6) | 0.049* |

| Complications, n (%) | 176 (40.1) | 64 (33.7) | 88 (34.8) | 0.13 |

| Respiratory impairment, n (%) | 31 (7.0) | 13 (6.6) | 17 (6.5) | 0.79 |

| Dysphagia, n (%) | 35 (7.9) | 12 (6.1) | 18 (6.9) | 0.65 |

| Deep venous thrombosis, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (2.6) | 4 (1.5) | 0.57 |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0.57 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 49 (11.0) | 20 (10.2) | 24 (9.2) | 0.43 |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 42 (9.5) | 21 (10.7) | 19 (7.3) | 0.33 |

| Cerebral infarction, n (%) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.5) | 0.46 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.19 |

| Delirium, n (%) | 39 (8.8) | 18 (9.1) | 15 (5.7) | 0.18 |

| Walking independence rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsb | 371 | 175 | 249 | |

| Walking capacity: walking w/ or w/o a cane, n (%) | 248 (66.9) | 131 (74.9) | 193 (77.5) | 0.03* |

| Home-discharge rate | ||||

| Number of subjectsc | 381 | 177 | 243 | 0.40 |

| Returned to home, n (%) | 306 (80.3) | 142 (80.2) | 202 (83.1) | |

| Admitted to a facility, n (%) | 25 (6.6) | 12 (6.8) | 11 (4.5) | |

| In hospital, n (%) | 50 (13.1) | 23 (13.0) | 30 (12.3) | |

Records with unknown or missing values were excluded from the analysis.

aPatients with a 6-month follow-up.

bPatients who were able to walk with or without a cane before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding mortality cases.

cPatients living at home before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding mortality cases.

*Statistically significant trend between the levels of fall height in the Cochran–Armitage test or Jonckheere–Terpstra test.

Prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes in cases of ground-level falls

In patients of falls from ground level, the common factors for poor prognosis, including mortality, walking disability, and difficulty in home discharge, were older age and severe neurological impairment at the time of injury. As for the other independent associated factors, presence of bone injury was associated with mortality and walking disability, high CCI score was associated with mortality, and high mFI-5 was associated with walking disability and difficulty in home discharge (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes at 6 months post-injury in patients with ground-level falls.

| Prognostic factors | OR | 95% CIs | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortalitya | |||

| Age at injury | 1.13 | 1.07–1.20 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-injury Charlson comorbidity index | 1.56 | 1.18–2.07 | < 0.01 |

| Presence of cervical bony injury | 3.35 | 1.50–7.48 | < 0.01 |

| ASIA impairment scale | 3.02 | 2.20–4.14 | < 0.001 |

| Walking disabilityb | |||

| Age at injury | 1.07 | 1.03–1.12 | 0.01 |

| Pre-injury modified 5-item frailty index | 1.63 | 1.11–2.39 | 0.01 |

| Presence of cervical bony injury | 2.03 | 1.11–3.74 | 0.02 |

| ASIA impairment scale | 4.79 | 3.23–7.10 | < 0.001 |

| Difficulty in home dischargec | |||

| Age at injury | 1.05 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.03 |

| Pre-injury modified 5-item frailty index | 1.91 | 1.28–2.85 | < 0.01 |

| ASIA impairment scale | 3.72 | 2.60–5.31 | < 0.001 |

All chi-squared tests for the models showed p < 0.001, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow tests showed p = 0.16, 0.84, and 0.81, respectively.

A correlation matrix was created to confirm that there was no high correlation between each explanatory variable.

ASIA American Spinal Injury Association, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio.

an = 449 with a 6-month follow-up.

bn = 371 who were able to walk with or without a cane before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding mortality cases.

cn = 381 who were living at home before injury with a 6-month follow-up, excluding mortality cases.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine clinical characteristics including patients’ background, injury status, and prognosis of traumatic cervical spine injuries in older adults from a nationwide database according to the external cause of injury. In this study, three-quarters of cervical spine injuries in older adults were caused by falls, with ground-level falls accounting for the largest proportion. Furthermore, more than 50% of those aged 85 years and older were injured due to falling from ground level. When fall-induced cervical spine injuries were categorized and compared based on fall height, the patients’ backgrounds and injury statuses differed significantly. Patients injured from ground-level falls tended to be older, have poorer pre-injury health conditions (e.g., medical comorbidities and frailty), a higher rate of incomplete neurological impairment without cervical bony injuries, and less associated injuries compared with those who fell from higher heights. For ground-level falls, the mortality, walking independence, and home-discharge rates at 6 months post-injury were 9%, 67%, and 80%, respectively. The prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes in patients injured due to ground-level falls were older age, pre-injury medical comorbidity and progression of frailty, presence of cervical bony injuries, and severity of neurological impairment at the time of injury according to AIS.

Falls are the most common causes of traumatic cervical spine injuries in older adults, accounting for 49–70% of geriatric cervical spine injuries11,22,25,26. Injuries from ground-level falls are particularly common in older adults, with more than 50% of traumatic cervical spine injuries caused by ground-level falls9,27,28. Our findings are consistent with those in previous reports, and the fact that the proportion of ground-level falls increased with age indicates that aging and cervical spine injury from minor trauma are clearly associated. Furthermore, cervical spine injuries caused by ground-level falls made it difficult for the patients to walk independently or be discharged from the hospital. Therefore, ground-level falls not only have a considerable impact on the health and quality of life of older people but also result in a social impact due to increased medical costs and need for nursing care11,29.

Several risk factors contribute to increased falls among older people and are generally classified as intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors are individual-specific factors such as old age, chronic disease, muscle weakness, visual impairment, gait and balance disorders, cognitive impairment, and frailty. Extrinsic factors generally include medications (> 4 or psychoactive medication use), environmental and socioeconomic hazards, and hazardous activities5,30–32. Many of these factors are consistent with the characteristics of ground-level fall cases in this study. Furthermore, these factors interact with each other; thus, prevention of falls involves eliminating or modifying the risk factors whenever possible through education, optimal medical management, home care, and behavior modification5.

It is still uncertain why older people are prone to cervical spine injuries from minor traumatic falls from ground level. Degenerative changes, such as reduced flexion and extension mobility, spinal canal stenosis, and osteoporosis of the cervical spine in older people, increase the risk of cervical spinal injury after relatively minor trauma33. Moreover, the presence of ligamentous ossification diseases, such as OPLL and DISH, partly explains this phenomenon. Ligamentous ossification is common among Asian populations, and the prevalence of OPLL in patients with cervical spine injury is quite high. Additionally, most cervical spine injuries associated with OPLL are incomplete without bony injuries, and are caused predominantly by low-energy trauma34,35. In patients with DISH, minor trauma can cause spinal fractures, and OPLL has been reported to be significantly associated with neurological deterioration36. The prevalence of OPLL and DISH was also high in the present cohort, especially in patients who were injured during minor falls, which undoubtedly contributes to the occurrence of cervical spine injuries in older people.

Impacts to the head during a fall have also been considered as a causative factor in fall-induced cervical spine injuries in older adults. Compared to younger adults, older adults experienced more frequent impacts to the head during falls from ground level, and with greater acceleration37. Neck strength decreases by 35–45% between the ages of 20 and 60 years38. These age-related neuromuscular changes, resulting in an inability to control the head during a fall, are probably responsible for the greater proportion of impacts to the head in older adults39,40. Furthermore, medical care and life-prolonging treatments and medications increase the survival rate of older adults with poor health and functioning, which in turn leads to an increase in serious falls10,41. This concept is supported by the findings in the present study, since there were more cases of patients with preexisting medical comorbidities, medications, and advanced frailty in cases of ground-level falls compared to falls from a higher height.

In general, cervical spine injuries in older adults result in poor outcomes, with high rates of mortality and complications and a low rate of home discharge42. However, the mortality rate in recent years has been improving, and the rate in this study was similar to that reported in recent years11,43,44. In contrast to the increasing incidence of fall-induced cervical spine injuries, the mortality rate has been decreasing, probably due to advanced medical management of these patients43,45. However, the prognosis of cervical spine injuries in older adults remains unfavorable. Although an association between the severity of neurological injury and mortality has been reported23, this appears to be a contradictory finding, as older adults tend to have higher rates of incomplete injury caused by low falls. It has been reported that the severity of neurological impairment at the time of injury alone is not sufficient to determine the prognosis in older adults, and this apparent contradiction is best explained by the presence of confounding factors that affect mortality46. The presence of comorbidities has been shown to be a risk factor for mortality in patients with spinal cord injury, and the CCI was found to be a more reliable predictor of in-hospital mortality than age or the severity of neurological impairment20. Additionally, decreased physiological reserve, widely known as "frailty", has been demonstrated to be associated with poor outcomes related to spinal cord injury, such as adverse events, mortality, and length of hospital stay; however, this association in older adults remains controversial21,47. This study indicates that the progression of frailty, a unique feature in ground-level fall cases, is significantly related to unfavorable prognoses such as walking disability and difficulty in home discharge. Functional recovery after spinal cord injury in older adults was considered to be worse due to decreased physiological reserve, even though neurological improvement was comparable to that in younger patients48,49. Thus, the progression of frailty seems to lead to a negative chain of events that not only increases the incidence of cervical spine injury due to falls, but also worsens its prognosis.

Finally, several factors prior to a fall-induced cervical spine injury, such as aging, underlying comorbidities, and frailty, significantly affect the onset of injury and its outcomes. In addition, falling as a cause of injury has been reported to be one of the significant predictors of long-term mortality after trauma50. The findings of this study support this, with a particularly poor prognosis in the case of ground-level falls, which were associated with pre-injury factors. Thus, ground-level falls should be treated separately from other injuries, as ground-level falls can be an indicator of pre-injury poor health and have a higher risk of unfavorable outcomes. It is therefore essential to improve the general health condition of older adults as well as to implement multifaceted fall prevention programs. Both the appropriate management of underlying comorbidities and frailty would decrease not only the incidence but also the severity of cervical spine injury in older adults. In Japan, a frailty questionnaire was introduced in general health examinations in 2020, and further accumulation of data and countermeasures based on it are expected.

The strength of the present study was that it was conducted using a nationwide, multicenter investigation to examine cervical spine injuries in older adults by the external cause of injury. However, there are several limitations, including the study’s retrospective design using a heterogeneous cohort without a control group and that it was not an exhaustive survey. Furthermore, it was difficult to perfectly compare the treatment outcomes by external causes of injury since there was no standardized treatment approach, including surgical indications and rehabilitation methods, and the patients’ backgrounds and injury statuses differed significantly depending on the external causes of injury. Moreover, the survey was conducted in Japan, which has a unique background with the world's most advanced aging population. However, the entire world is moving toward a super-aging society, and cervical spine injury in older adults has become an urgent issue. We believe that the results of this study will provide valuable information as a model case for the aging society.

Conclusion

Falls were the most common cause of traumatic cervical spine injury in older adults, with ground-level falls accounting for the largest proportion. When falls were categorized and compared based on the fall height, it was found that the patients’ backgrounds and injury statuses differed markedly. Furthermore, patients injured from ground-level falls tended to have poorer pre-injury health conditions, such as medical comorbidities and frailty, compared with those who fell from higher heights. For ground-level falls, mortality, walking independence, and home-discharge rates at 6 months post-injury were 9%, 67%, and 80%, respectively, with a high CCI associated with higher mortality and a high mFI-5 associated with walking disability and difficulties during home discharge, independent of age or the severity of neurological impairment at the time of injury. Thus, it is important to treat and manage older patients who sustain cervical spine injuries due to minor trauma, such as a ground-level fall, considering that they may have relatively poor pre-injury health conditions, making them prone to unfavorable outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the members of the Japan Association of Spine Surgeons with Ambition contributing to this study. We would also like to thank Yoshitomo Saiki for his assistance with the statistical analysis.

Author contributions

N.Y., S.K., K.A., T.F., G.I., T.K., and K.W. conceived and designed the study. All authors collected the data. N.Y. and S.K. prepared the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-19789-y.

References

- 1.World population ageing 2019. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf (U.N., Dept of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019) (online). Accessed 18 Oct 2021.

- 2.Population estimates 2021. Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/tsuki/index.html (2021) (online). Accessed 18 Oct 2021.

- 3.Kannus P, et al. Fall-induced injuries and deaths among older adults. JAMA. 1999;281:1895–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.20.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz DA, Latham NK. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:734–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1903252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO global report on falls preventions in older age. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHo-Global-report-on-falls-prevention-in-older-age.pdf (World Health Organization, 2007) (online). Accessed 18 Oct 2021.

- 6.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries Among adults aged ≥ 65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kannus P, Palvanen M, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Alarming rise in the number and incidence of fall-induced cervical spine injuries among older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007;62:180–183. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bank M, et al. Age and other risk factors influencing long-term mortality in patients with traumatic cervical spine fracture. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2018;9:2151459318770882. doi: 10.1177/2151459318770882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, et al. Geriatric trauma patients with cervical spine fractures due to ground level fall: Five years experience in a level one trauma center. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2013;5:75–83. doi: 10.4021/jocmr1227w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korhonen N, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Sievänen H. Rapid increase in fall-induced cervical spine injuries among older Finnish adults between 1970 and 2011. Age Ageing. 2014;43:567–571. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asemota AO, et al. Analysis of cervical spine injuries in elderly patients from 2001 to 2010 using a nationwide database: Increasing incidence, overall mortality, and inpatient hospital charges. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:e114–e130. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyakoshi N, et al. A nationwide survey on the incidence and characteristics of traumatic spinal cord injury in Japan in 2018. Spinal Cord. 2021;59:626–634. doi: 10.1038/s41393-020-00533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bickenbach, J., Officer, A., Shakespeare, T., Von Groote, P. International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury (World Health Organization, 2013).

- 14.Zhang ZR, Wu Y, Wang FY, Wang WJ. Traumatic spinal cord injury caused by low falls and high falls: A comparative study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021;16:222. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02379-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Tang Y, Allen V, DeVivo MJ. Fall-induced spinal cord injury: External causes and implications for prevention. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:24–31. doi: 10.1179/2045772315Y.0000000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramaniam S, Aalberg JJ, Soriano RP, Divino CM. New 5-factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018;226:173–181.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalafallah AM, Huq S, Jimenez AE, Brem H, Mukherjee D. The 5-factor modified frailty index: An effective predictor of mortality in brain tumor patients. J. Neurosurg. 2020;14:1–9. doi: 10.3171/2020.5.JNS20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirshblum SC, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011) J. Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–546. doi: 10.1179/204577211X13207446293695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlan JC, Kattail D, Fehlings MG. The impact of co-morbidities on age-related differences in mortality after acute traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1361–1367. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banaszek D, et al. Effect of frailty on outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2020;37:839–845. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golob JF, Jr, Claridge JA, Yowler CJ, Como JJ, Peerless JR. Isolated cervical spine fractures in the elderly: A deadly injury. J. Trauma. 2008;64:311–315. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181627625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fassett DR, et al. Mortality rates in geriatric patients with spinal cord injuries. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2007;7:277–281. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/09/277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert JS, Burnham RS. The effect of polytrauma in persons with traumatic spine injury. A prospective database of spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik SA, Murphy M, Connolly P, O'Byrne J. Evaluation of morbidity, mortality and outcome following cervical spine injuries in elderly patients. Eur. Spine J. 2008;17:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomoschitz FM, Blackmore CC, Mirza SK, Mann FA. Cervical spine injuries in patients 65 years old and older: Epidemiologic analysis regarding the effects of age and injury mechanism on distribution, type, and stability of injuries. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002;178:573–577. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labib N, et al. Severely injured geriatric population: Morbidity, mortality, and risk factors. J. Trauma. 2011;71:1908–1914. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820989ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz DT, et al. Prevalence of falls and associated factors in elderly individuals. Rev. Saude Publica. 2012;46:138–146. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011005000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furlan JC, Craven BC, Fehlings MG. Surgical management of the elderly with traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: A cost-utility analysis. Neurosurgery. 2016;79:418–425. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It’s always a trade-off”. JAMA. 2010;303:258–266. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deandrea S, et al. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21:658–668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeiren S, et al. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016;17(1163):e1–1163.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagen EM, Aarli JA, Gronning M. The clinical significance of spinal cord injuries in patients older than 60 years of age. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2005;112:42–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chikuda H, et al. Acute cervical spinal cord injury complicated by preexisting ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a multicenter study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1453–1458. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f49718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato H, et al. Cervical spinal cord injury without bony injury: A multicenter retrospective study of emergency and critical care centers in Japan. J. Trauma. 2008;65:373–379. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817db11d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada E, et al. Spinal fractures in patients with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Clinical characteristics by fracture level. J. Orthop. Sci. 2019;24:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood TA, Moon Y, Sun R, Bishnoi A, Sosnoff JJ. Age-related differences in head impact during experimentally induced sideways falls. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019:6804614. doi: 10.1155/2019/6804614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcés GL, Medina D, Milutinovic L, Garavote P, Guerado E. Normative database of isometric cervical strength in a healthy population. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002;34:464–470. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huelke, D. F. Anatomy of the Human Cervical Spine and Associated Structures (SAE Int., 1979).

- 40.Bogduk N, Mercer S. Biomechanics of the cervical spine. I: Normal kinematics. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol Avon) 2000;15:633–648. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(00)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korhonen N, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Kannus P. Incidence of fall-related traumatic brain injuries among older Finnish adults between 1970 and 2011. JAMA. 2013;309:1891–1892. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith S, Purzner T, Fehlings M. The epidemiology of geriatric spinal cord injury. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2010;15:54–64. doi: 10.1310/sci1503-54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau D, et al. Value of aggressive surgical and intensive care unit in elderly patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurosurg. Focus. 2019;46:E3. doi: 10.3171/2018.12.FOCUS18555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menendez ME, Ring D, Harris MB, Cha TD. Predicting in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with cervical spine fractures: A comparison of the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:809–815. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kannus P, Niemi S, Sievänen H, Parkkari J. Declining incidence in fall-induced deaths of older adults: Finnish statistics during 1971–2015. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018;30:1111–1115. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-0898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engel-Haber E, Zeilig G, Haber S, Worobey L, Kirshblum S. The effect of age and injury severity on clinical prediction rules for ambulation among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spine J. 2020;20:1666–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.05.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flexman AM, Charest-Morin R, Stobart L, Street J, Ryerson CJ. Frailty and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spine disease. Spine J. 2016;16:1315–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seel RT, Huang ME, Cifu DX, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, McKinley WO. Age-related differences in length of stays, hospitalization costs, and outcomes for an injury-matched sample of adults with paraplegia. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:241–250. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2001.11753581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. The impact of age on mortality, impairment, and disability among adults with acute traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1707–1717. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davidson GH, et al. Long-term survival of adult trauma patients. JAMA. 2011;305:1001–1007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.