Abstract

Currently, the identification of stroke patients with an increased suicide risk is mainly based on self‐report questionnaires, and this method suffers from a lack of objectivity. This study developed and validated a suicide ideation (SI) prediction model using clinical data and identified SI predictors. Significant variables were selected through traditional statistical analysis based on retrospective data of 385 stroke patients; the data were collected from October 2012 to March 2014. The data were then applied to three boosting models (Xgboost, CatBoost, and LGBM) to identify the comparative and best performing models. Demographic variables that showed significant differences between the two groups were age, onset, type, socioeconomic, and education level. Additionally, functional variables also showed a significant difference with regard to ADL and emotion (p < 0.05). The CatBoost model (0.900) showed higher performance than the other two models; and depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, and rehabilitation motivation were found to have high importance. Negative emotions such as depression and anxiety showed a positive relationship with SI and rehabilitation motivation and self-efficacy displayed an inverse relationship with SI. Machine learning-based SI models could augment SI prevention by helping rehabilitation and medical professionals identify high-risk stroke patients in need of SI prevention intervention.

Subject terms: Psychology, Diseases, Health care, Risk factors

Stroke is a cerebrovascular disease characterized by neurological deficits, including hemiplegia, sensory dysfunction, aphasia, neglect, and intellectual and mental disabilities1. Post-stroke depression (PSD) is considered the most frequent and important sequela of stroke2, and is the largest indicator of the occurrence of suicidal ideation (SI)3. COVID-19 pandemic may increase the prevalence of psychiatric disorder and suicide rates during and after the pandemic and this increase in suicides can be attributed to fears of contracting the illness, fears of being a burden to the family, anxiety, social isolation and psychological distress4. Such mental health issues may increase SI risk, especially in patients with PSD5,6.

SI precedes suicidal attempts or suicidal behaviors, and understanding the effect of SI contributes to understanding and preventing the risk of suicidal behavior7. SI is more prevalent among those with persistent physical and cognitive impairments resulting from stroke8. The prevalence of suicidal ideation among stroke patients was 13.99%9. In this way suffering a stroke was significantly associated with suicidal ideation10. In other words, given the high prevalence of suicidal ideation in stroke patients, there is a need to evaluation related factors and performance thorough screenings in this population9. Previous studies have reported that the occurrence of depression and mood disorders increases SI in stroke patients, and that there is a significant positive correlation between depression and SI in stroke patients11,12. Therefore, a clinical data prediction model is necessary to reduce SI in patients after a stroke.

Most of the developed stroke prediction models are reported in studies on diagnosis, sequela, mortality, and physical function, and cannot be conveniently used practically owing to the associated invasive measurements and analyses13–16. Additionally, while studies on predictive model development for stroke-related emotional disorders, such as post-stroke anxiety and PSD have been conducted17,18, the predictors used in these models were assessed at one-month post-stroke, at which point full depressive symptoms may not be present. Additionally, procedures need to be devised for the comparison of different machine learning models to select the best among them.

This study presents a stroke patient SI prediction model independent of biochemical data that are not routinely collected and aims to differentiate SI. For this purpose, we used the data collected from a specialized hospital in Daegu Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea, to predict high or low levels of SI outcomes in patients with stroke. To date, there have been no similar studies, and most of the developed models require image data and invasive test data, which are difficult to collect. This study is also the first to apply the best model selected after comparing the performance of three boosting models using medical history, demographic and psychological factors, cognitive and activities of daily living (ADL) function data collected from a sample of subacute and chronic stroke patients in an attempt to create an SI prediction tool.

Methods

Setting, data description, and pre-processing

A total of 385 stroke patients were screened for eligibility between October 2012 and March 2014. The eligibility criteria were as follows: diagnoses confirmed based on the results of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography images evaluated by a physician; patients in the age range of 18–80 years; a diagnosis of ischemic and hemorrhage stroke type; and patients with an onset of subacute stroke between one and six months and chronic stroke over six months. The collected anonymized sample data included information on demographics, hospital admission, cognitive function, motor function, ADL, and emotion assessment results. The ethics committee of our Institutional Review Board reviewed this study. This is a retrospective study using anonymized data obtained with written consent from all patients. This study has been the ethics committee of Daegu University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study (1040621-202111-HR-079) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

The features obtained from pre-processing were then divided into five domains based on the assessment for which they were collected. All the potential predictors, including sociodemographic factors, cognitive function, motor function, ADL, and emotional parameters, were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records and experimental data. Assessments included the Scale for SI19–21, the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-K)22, the Manual Function Test (MFT)23, the Korean version of the Modified Bathel Index (K-MBI)24, Self-Efficacy Scale25, the Rehabilitation Motivation Scale (RMS)26, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)27, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)28. The study data indicated that the assessment outcome had high reliability and validity.

Demographic features included sex, age, phase, type, affected side, dominant hand, socioeconomic level, marital status, hypertension, diabetes, family/past history, smoking and drinking, education, and transfer. Cognitive function was measured using the MMSE-K, motor function using the MFT, and ADL using the K-MBI. Finally, positive emotions were measured using the Self-Efficacy scale and the RMS, and negative emotions were measured using the BAI and BDI.

Variables for demographic features, cognitive function, motor function, and ADL, as well as numerical variables for emotion were included in the dataset. The target variable was the SI Scale score. To transform the problem into a binary classification one and to compare our results directly with those obtained by existing methods, we discretized the SI into two classes: high SI group ( 14) and low SI group ( 14)19–21. This particular discretization is medically relevant because it helps to distinguish between stroke patients who will be able to live an independent life from those with a significant suicide risk.

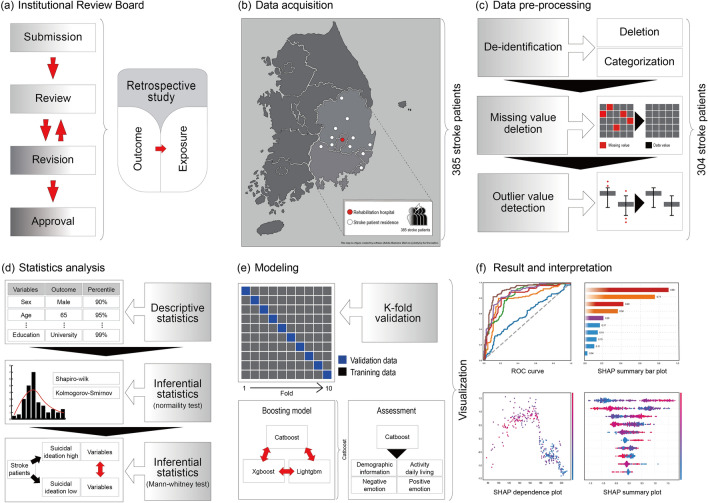

The age variables were transformed into categorical variables. Two pre-processing methods were used to eliminate the outliers and missing values. For patient data containing missing values, the deletion technique was used29. Outliers were selected as results outside the upper and lower limits based on the quartile and were deleted30. After data cleaning, the resulting dataset contained 23 features, and the data of 304 patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the datasets, which were then used for model training and validation (Fig. 1). All the stroke patients included in the study were screened, and anonymized data were used for a retrospective study comprising two groups: high SI group (n = 165) and low SI group (n = 139).

Figure 1.

Stroke suicidal ideation prediction model.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. Frequency analysis and chi-square test were performed, and a normality test was performed to determine normality of the distributions. The age variable was collected into a categorical variable for anonymization. The study data does not contain a continuous age variable. However, it does have a categorical age variable, which is composed of multiple age groups of varying widths31; it was converted into a 10-year interval based on the original data. Two groups (high and low SI) were divided based on a score of 14 based on cut-off points in three SI studies19–21 and consultations with two psychiatric and rehabilitation experts. And the Mann–Whitney U (two tailed) test was conducted to determine statistically significant difference in the variables (demographic information, cognitive, motor, ADL, emotional function) between the two groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (Fig. 1). Three models (Xgboost, CatBoost, LGBM) were compared and the one with the best performance, that is the CatBoost model, was selected.

SI prediction model

We used an ML approach to develop the SI prediction models for stroke patients. The three boosting models (Xgboost, CatBoost, and Light GBM [gradient booting model]) apply an algorithm based on gradient boosted decision trees. Xgboost implements the gradient boosting algorithm, which combines numerous decision trees for elaborate classification, in a fast and generalized manner32. XGBoost also applies a sparsity-aware algorithm to find the best split faster than the other methods. Light GBM (LGBM) is an advanced implementation of gradient boosting. This algorithm differs from the other algorithms in the growth of the tree in-depth or by leaves. LGBM handles large amounts of data with the lowest memory requirements33,34. Almost all the modern gradient-based methods work well with numerical attributes. If the dataset contains both numerical and categorical variables, then the categorical ones must be converted to numerical ones; this however leads to a potential decrease in the model’s accuracy. CatBoost is a gradient enhancement library whose main advantage lies in that it works well with categorical features35. One-hot encoding is used for processing categorical features, but this method incurs more computational complexity and memory owing to its high cardinalities. Therefore, an effective way to process categorical features is to use the CatBoost algorithm based on modified target statistics.

Model performance evaluation

In the previous section, the variables that showed a significant difference between the two groups were selected through a traditional statistical analysis. The stroke SI model was tested using the ten-fold cross validation dataset36. The values of the hyperparameters were optimized and the optimization was performed and the tested values (Supplementary 1). The overall model predictive performance was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The performance characteristics of the stroke SI model indicate sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) results. A sub-assessment was performed by selecting the model with the highest performance. For each assessment, a separate ROC curve was generated using the predictions obtained from the highest-performance model and the outcomes within each assessment. The importance and relationship of stroke SI variables were derived through Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) values. The red and blue dots indicate that the variables at that point had positive and negative effects on the SI occurrence, respectively. The data were analyzed using Python 3.7.12 (Python Software Foundation).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Daegu University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study (1040621-202111-HR-079). This is a retrospective study using anonymized data obtained with written informed consent from all patients. This study has been independently reviewed and approved by an IRB.

Results

The demographic data of the stroke patients are presented in Table 1. The variables that showed a significant difference between the two groups based on the SI outcome criterion were age, onset, type, socioeconomic level, and education level (p < 0.05). The high SI group had a higher frequency of older adults over 65 years of age than the low SI group. The onset group had a higher frequency of older adults when the stroke onset was less than 6 months, the socioeconomic level was poor, and the education level was low.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics based on suicidal ideation.

| Variables | Total (n = 304) | SI low (n = 165) | SI High (n = 139) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Sex | .090 | ||||||

| Male | 220 | 72.4 | 126 | 76.4 | 94 | 67.6 | |

| Female | 84 | 27.6 | 39 | 23.6 | 45 | 32.4 | |

| Age | .016 | ||||||

| Under 45 | 76 | 25.0 | 49 | 29.7 | 27 | 19.4 | |

| 45–54 | 131 | 43.1 | 67 | 40.6 | 64 | 46.0 | |

| 55–64 | 66 | 21.7 | 39 | 23.6 | 27 | 19.4 | |

| 65 over | 31 | 10.2 | 10 | 6.1 | 21 | 15.1 | |

| Onset | .015 | ||||||

| Subacute | 174 | 57.2 | 84 | 50.9 | 90 | 64.7 | |

| Chronic | 130 | 42.8 | 81 | 49.1 | 49 | 35.3 | |

| Type | .009 | ||||||

| Ischemic | 235 | 77.3 | 137 | 83.0 | 98 | 70.5 | |

| Hemorrhage | 69 | 22.7 | 28 | 17.0 | 41 | 29.5 | |

| Affected side | .084 | ||||||

| Right | 178 | 58.6 | 104 | 63.0 | 74 | 53.2 | |

| Left | 126 | 41.4 | 61 | 37.0 | 65 | 46.8 | |

| Dominant hand | .242 | ||||||

| Right | 291 | 95.7 | 160 | 97.0 | 131 | 94.2 | |

| Left | 13 | 4.3 | 5 | 3.0 | 8 | 5.8 | |

| Socioeconomic level | .001 | ||||||

| High (Health insurance) | 267 | 87.8 | 154 | 93.3 | 113 | 81.3 | |

| Low (Medical care) | 37 | 12.2 | 11 | 6.7 | 26 | 18.7 | |

| Hypertension | .870 | ||||||

| Yes | 180 | 59.2 | 97 | 58.8 | 83 | 59.7 | |

| No | 124 | 40.8 | 68 | 41.2 | 56 | 40.3 | |

| Diabetes | .295 | ||||||

| Yes | 90 | 29.6 | 53 | 32.1 | 37 | 26.6 | |

| No | 214 | 70.4 | 112 | 67.9 | 102 | 73.4 | |

| Marital status | .056 | ||||||

| Married | 222 | 73.0 | 124 | 75.2 | 98 | 70.5 | |

| Unmarried | 59 | 19.4 | 34 | 20.6 | 25 | 18.0 | |

| Divorced/widowed | 23 | 7.6 | 7 | 4.2 | 16 | 11.5 | |

| Family history | .092 | ||||||

| Yes | 170 | 55.9 | 85 | 51.5 | 85 | 61.2 | |

| No | 134 | 44.1 | 80 | 48.5 | 54 | 38.8 | |

| Past history | .421 | ||||||

| Yes | 119 | 39.1 | 68 | 41.2 | 51 | 36.7 | |

| No | 185 | 60.9 | 97 | 58.8 | 88 | 63.3 | |

| Smoking | .408 | ||||||

| Yes | 174 | 57.2 | 98 | 59.4 | 76 | 54.7 | |

| No | 130 | 42.8 | 67 | 40.6 | 63 | 45.3 | |

| Drinking | .791 | ||||||

| Yes | 262 | 86.2 | 143 | 86.7 | 119 | 85.6 | |

| No | 42 | 13.8 | 22 | 13.3 | 20 | 14.4 | |

| Education | .017 | ||||||

| Uneducated | 12 | 3.9% | 1 | 0.6 | 11 | 7.9 | |

| Elementary | 7 | 2.3% | 4 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.2 | |

| Middle School | 18 | 5.9% | 8 | 4.8 | 10 | 7.2 | |

| High School | 216 | 71.1% | 125 | 75.8 | 91 | 65.5 | |

| University | 51 | 16.8% | 27 | 16.4 | 139 | 17.3 | |

| Transfer | .108 | ||||||

| Wheelchair | 91 | 29.9 | 43 | 26.1 | 48 | 34.5 | |

| Ambulation | 213 | 70.1 | 122 | 73.9 | 91 | 65.5 | |

Abbreviation: SI, suicidal ideation.

The results presented in Table 2 indicate a significant difference in ADL and emotions in both the groups (p < 0.05). In particular, there was a significant difference between the two groups in the emotional domain (p < 0.001). Cognition and motor functions, on the other hand, did not differ between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of cognitive functions, motor functions, ADL, emotional functions between both groups.

| Domain | SI low (n = 165) | SI High (n = 139) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | IQR | Mean (SD) | IQR | p | ||

| Cognition | ||||||

| MMSE | 23.99 (1.54) | 23–25 | 23.91 (1.70) | 23–25 | .784 | |

| Motor | ||||||

| MFT | 22.28 (2.04) | 21–24 | 22.03 (1.78) | 21–23 | .207 | |

| ADL | ||||||

| MBI | 72.45 (5.99) | 69–77 | 71.00 (6.59) | 66–77 | .023 | |

| Emotion | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | 189.18 (30.61) | 181–216 | 154.24 (30.89) | 131–156 | .001 | |

| Rehabilitation motivation | 90.77 (14.61) | 81–100 | 73.14 (14.37) | 63–82 | .001 | |

| BAI | 15.53 (4.04) | 12–17 | 21.83 (5.22) | 18–23 | .001 | |

| BDI | 14.35 (4.47) | 13–18 | 20.08 (4.62) | 19–24 | .001 | |

Abbreviations: SI, suicidal ideation; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; MFT, manual function test; MBI, modified Bathel index; BAI, beck anxiety inventory; BDI, beck depression inventory.

Table 3 shows the combined analysis of one evaluation tool indicating a significant difference between the two groups and all demographic information variables indicating a significant difference between the two groups. As shown in Table 3, emotional features such as BDI (depression), BAI (anxiety), self-efficacy, and rehabilitation motivation showed generally better results than MBI in the CatBoost model. Sensitivity and NPV were rehabilitation motivation, specificity was MBI, and PPV was self-efficacy, with BDI having the highest accuracy. Additionally, as for the cut-off points, BDI showed a mild depressive state, and MBI showed a cut-off point of moderate dependence, whereas BAI showed a normal level cut-off point. Supplementary information 2 shows the measure value analyzed by combining the demographic information and the entire evaluation tool that showed a significant difference between the two groups. Among the three models, the area under the AUC value was higher for the CatBoost model than the other two models, and most values (sensitivity, NPV) outperformed the XGBoost and LGBM scores (Supplementary information 2).

Table 3.

Result of the CatBoost model based on emotion and ADL data.

| Variables | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | Cut off value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBI | .317 | .861 | .656 | .599 | .612 | 68 |

| Self-efficacy | .799 | .824 | .792 | .829 | .812 | 177 |

| Rehabilitation motivation | .899 | .636 | .675 | .882 | .757 | 86 |

| BAI | .791 | .794 | .763 | .818 | .793 | 18 |

| BDI | .813 | .794 | .768 | .834 | .803 | 19 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activity daily living; PPV, positive predict value; NPV, negative predict value; MBI, modified bathel index; BAI, beck anxiety inventory; BDI, beck depression inventory.

Supplementary information 3 shows the ROC curve of the analysis results in Table 3 and the ROC curve analyzed by combining the demographic information and the entire evaluation tool that showed a significant difference between the two groups. Supplementary information 3 shows the ROC curves of the CatBoost classifier for the five functional assessments. The AUC values were ordered as per the order presented in Table 3: first, negative emotion evaluation, such as evaluation of depression and anxiety; second, positive emotion evaluation; and third, ADL assessment. Furthermore, the AUC value, which includes the demographic variables that indicated a significant difference between the two groups, as well as the exercise and emotion evaluation, showed the highest result.

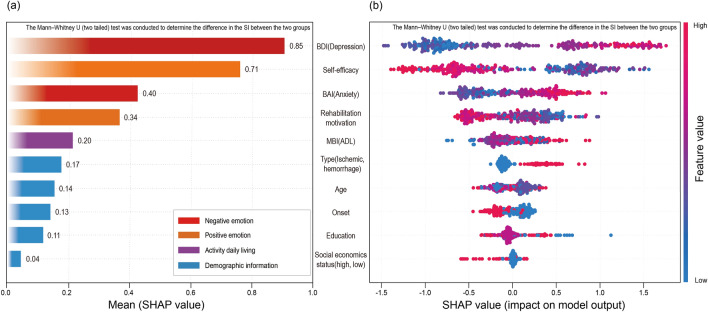

Regarding SHAP, depression was found to be the most important predictor for SI in stroke patients, followed by emotional variables such as self-efficacy, anxiety, and rehabilitation motivation. In the SHAP summary plot result (Fig. 2), it was seen that the higher the negative emotions such as depression and anxiety, the higher the SI. Conversely, the lower the positive emotions such as self-efficacy and rehabilitation motivation, the higher the SI.

Figure 2.

Feature importance based on SHAP values (The red and blue dots indicate that the variables at that point had positive and negative effects on the SI occurrence, respectively): (a) Mean absolute SHAP values (b) Summary.

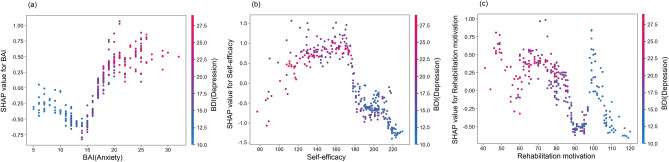

Using the SHAP dependence plot, the results of the interaction relationship between anxiety, rehabilitation motivation, self-efficacy, and ADL that exhibited significant differences were derived based on depression, which demonstrated the greatest importance for SI in stroke patients. Negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, showed a positive relationship, and positive emotions, such as rehabilitation motivation and self-efficacy, exhibited an inverse relationship with SI. There was no evident association between depression and ADL function (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Partial dependence plot by SHAP value. Relationship between (a) self-efficacy and depression (b) rehabilitation motivation and depression (c) anxiety and depression.

Discussion

In this study, using stroke patients’ data from a rehabilitation hospital, we developed and validated a model for SI prediction in stroke patients within a post-onset period. Using the statistically significant predictors that a stroke patient can report in a direct interview and survey, performance was compared for the three boosting models.

Using the chi-square test for the demographic variables used in this study, statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups divided on the basis of age, onset, stroke type, and economic and education level. Among them, the high SI group had a high proportion of participants aged 65 years, an onset of less than six months, hemorrhagic stroke, and low economic, and education levels. This suggested that risk factors for SI in stroke patients increased in various pathologies due to rapid changes that take place associated with old age, loss and maladaptation immediately after onset11, hemorrhagic stroke, severe pain, poor prognosis37, low socioeconomic level, and low educational level. This can be seen as a low-income group38,39. Additionally, there was a significant difference for widowed or divorced patients, which showed an approximate result (Table 1). This finding was consistent with a previous study that indicated a large difference depending on whether the support of the family or spouse was present40.

Based on the study results, a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the variables of ADL and emotional function was noted. In previous studies, cognitive dysfunction was found to be associated with suicide39,41, which was not observed in the results of the current study. The cognitive function evaluation tool used in this study, the MMSE, is simple and efficient; however, we believe that it may have been affected by low sensitivity, as it is a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment42. In the case of MFT, lower extremity functions, such as gait function43,44, that affect depression in stroke patients were not included, and so, there was no significant difference between the two groups. In contrast, depression can be viewed as the biggest risk factor for SI according to previous studies’ results43, and has previously showed a strong correlation with ADL, anxiety, self-efficacy, and Rehabilitation motivation45,46. Therefore, it is thought that there was a significant difference between the two groups in ADL and emotional variables.

Only statistically significant demographic and functional domain variables were applied to the three boosting models to derive their respective performances47,48. After comparing the performance of the three models, it was found that LGBM had the most inferior performance, whereas Xgboost showed the best performance in terms of specificity, PPV, and accuracy. Further, CatBoost showed the best performance in terms of sensitivity, NPV, and AUC (Supplementary information 2). While XGBoost and LightGBM offer several advantages, it must be noted that 16 out of the 23 variables of the stroke data used in this study were categorical. When a large number of categorical features are present in the dataset, then CatBoost may offer a more efficient performance49. In addition, LGBM is disadvantageous in that its application to small datasets (i.e., fewer than 10,000 cases) leads to leaf-wise growth, which, in turn, causes significant overfitting, whereas XGBoost cannot handle categorical features on its own50,51. Additionally, the classification performance improved when more features were added to the classifiers (Supplementary information 3). The predicted results can be used to take the necessary precautions and improve the function of stroke patients. Further, the AUC of the best classifiers was approximately 0.900. This value can be said to be sufficient for the reliable prediction of patients’ functional outcomes52.

Figure 2a shows the absolute influence of each variable of CatBoost through SHAP on the model. Notably, it is crucial for physicians to understand the effect of various factors on the SI of stroke patients. The variable that showed the greatest influence on stroke occurrence in patient SI was “depression,” followed by “self-efficacy,” “anxiety,” “rehabilitation motivation,” and so forth. The emotion function level had a significant influence on the occurrence of SI in stroke patients. Figure 2b is a SHAP summary showing the degree of influence of each variable on stroke patient SI prediction. Thus, higher levels of “depression” and “anxiety” meant that the probability of SI occurrence increased53. Therefore, the higher the “self-efficacy” and “rehabilitation motivation,” the lower the probability of SI occurrence, thereby exhibiting an inverse relationship with each other. Figure 3 is a SHAP partial dependent plot showing the correlation between depression, the most influential SI predictor in stroke patients, and other important predictive factors. Positive emotions, such as rehabilitation motivation, and self-efficacy, are observed to have a negative correlation (Fig. 3 b, c). The results thus obtained were identical to those reported in previous studies on depression, anxiety, rehabilitation motivation, and self-efficacy in stroke patients; negative and positive emotions were found to be the main factors affecting the SI of stroke patients; further, it was found that the two had opposite effects on each other54–56.

The stroke SI prediction model developed in this study can therefore be used to classify stroke patients into low- and high-risk SI groups based on routinely collected medical data and self-report questions. Furthermore, improved characterization of low and high risk for stroke-related SI can be achieved by analyzing the importance and correlation of the model’s prediction features. The implementation of a stroke SI prediction model in public health systems may facilitate early stroke SI detection and intervention programs, thereby reducing suicidal ideation. Additionally, it should be noted that a prediction model is only a tool to support the clinician and therefore cannot be used to replace personal judgment.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, prospective clinical trials are needed to demonstrate a clear clinical benefit of the addition of a stroke SI prediction model to the clinical intervention system. Clearer information about risk predictors can be provided by collecting additional data. Second, the study results cannot be generalized for all stroke features, such as biochemical indices and lesion location, which are also considered risk factors. Future studies should combine these to reveal the interactions of pathophysiological risk factors17. In a follow-up study, the model may benefit from the inclusion of as yet unavailable contributing predictors, such as invasive test data like quantitative brain structural and functional imaging data of stroke patients.

Conclusion

We constructed a comprehensive risk prediction model for SI in stroke patients based on clinical and psychological features. The model indicated that psychological factors were important for identifying SI risk in subacute and chronic stroke patients and contributed to post-stroke rehabilitation and mental health. Furthermore, the prediction model ultimately works as a decision tool to help clinicians identify the SI risk early, which will allow the optimization of stroke patients’ suicide prevention strategies in personalized medicine.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Prof. Eui kyu Chie and Prof. Hwan Kim for their support. Furthermore, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- PSD

Post-stroke depression

- SI

Suicidal ideation

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- MMSE-K

Mini-mental state examination-Korea

- MFT

Manual function test

- RMS

Rehabilitation motivation scale

- K-MBI

Modified bathel index

- BAI

Beck anxiety inventory

- BDI

Beck depression inventory

- LGBM

Light GBM

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SHAP

Shapley additive explanation

Author contributions

S.I.S., S.B.L. contributed to design the study, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. S.I.S., H.T.H. collected and pre-processing the stroke patient data regarding the rehabilitation. S.I.S., S.B.L, C.L. analyzed and interpreted the stroke patient data regarding the rehabilitation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea [Grant No.: HI21C1074]. The funding source had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

Due to privacy/ethical restriction, data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-19828-8.

References

- 1.Umphred, D. A., & Lazaro, R. T. Neurological Rehabilitation. Elsevier (2012).

- 2.De Ryck A, Brouns R, Geurden M, Elseviers M, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S. Risk factors for poststroke depression: Identification of inconsistencies based on a systematic review. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2014;27:147–158. doi: 10.1177/0891988714527514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohjasvaara T, Vataja R, Leppävuori A, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T. Suicidal ideas in stroke patients 3 and 15 months after stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2001;12:21–26. doi: 10.1159/000047676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020;113(10):707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller-Thomson E, Tulipano MJ, Song M. The association between depression, suicidal ideation, and stroke in a population-based sample. Int. J. Stroke. 2012;7:188–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poudel K, Subedi P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socioeconomic and mental health aspects in Nepal. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66:748–755. doi: 10.1177/0020764020942247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mash HBH, Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, Fullerton CS, Aliaga PA, et al. Predictors of suicide attempt within 30 days after first medically documented suicidal ideation in US Army soldiers. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021;178:1050–1059. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.20111570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faber RA. Suicide in neurological disorders. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:103–105. doi: 10.1159/000068751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park EY. Kim, JH/ Factors related to suicidal ideation in stroke patients in South Korea. J. Ment. Health. 2016;25(2):109–113. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1101412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SM. Health status and suicidal ideation in Korean elderly: the role of living arrangement. J. Ment. Health. 2014;23(2):94–98. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.869569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pompili M, Venturini P, Campi S, Seretti ME, Montebovi F, Lamis DA, et al. Do stroke patients have an increased risk of developing suicidal ideation or dying by suicide? An overview of the current literature. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012;18:711–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin KM, Cho SM, Hong CH, Park KS, Shin YM, Lim KY, et al. Suicide among the elderly and associated factors in South Korea. Aging Ment. Health. 2013;17:109–114. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.702732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brugnara G, Neuberger U, Mahmutoglu MA, Foltyn M, Herweh C, Nagel S, et al. Multimodal predictive modeling of endovascular treatment outcome for acute ischemic stroke using machine-learning. Stroke. 2020;51:3541–3551. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo J, Yoon JG, Park H, Kim YD, Nam HS, Heo JH. Machine learning–based model for prediction of outcomes in acute stroke. Stroke. 2019;50:1263–1265. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scrutinio D, Ricciardi C, Donisi L, Losavio E, Battista P, Guida P, et al. Machine learning to predict mortality after rehabilitation among patients with severe stroke. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:20127. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tozlu C, Edwards D, Boes A, Labar D, Tsagaris KZ, Silverstein J, et al. Machine learning methods predict individual upper-limb motor impairment following therapy in chronic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural. Repair. 2020;34:428–439. doi: 10.1177/1545968320909796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R, Yue Y, Jiang H, Lu J, Wu A, Geng D, et al. A risk prediction model for post-stroke depression in Chinese stroke survivors based on clinical and socio-psychological features. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62891–62899. doi: 10.1832/oncotarget.16907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Zhao D, Lin M, Huang X, Shang X. Post-stroke anxiety analysis via machine learning methods. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:657937. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.657937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin MS, Park KB, Oh KJ, Kim ZS. A study of suicidal ideation among high school students: the structural relation among depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. Kor. J. Clin. Psychol. 1990;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefansson J, Peter N, Jussi J. Suicide Intent Scale in the prediction of suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;136(1–2):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto S, Kondo T, Suzukamo Y, Michimata A, Izumi S-I. Reliability and validity of the Manual Function Test in patients with stroke. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009;88:247–255. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181951133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel index for stroke rehabilitation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychol. Rep. 1982;51:663–671. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H, Hwang Y, Yu J, Jung J, Woo H, Jung H. The correlation between depression, motivation for rehabilitation, activities of daily living, and quality of life in stroke patients. J. Kor. Soc. Occup. Ther. 2009;17:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer R. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Überblick Reliabilitäts Validitätsbefunde Klin Außerklinischen Selbst Fremdbeurteilungsverfahren. 1988;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aljuaid, T., & Sreela, S. Proper imputation techniques for missing values in data sets. In 2016 International Conference on Data Science and Engineering (ICDSE) (2016).

- 30.Tukey, J. W. Exploratory Data Analysis, vol. 2 (1977).

- 31.Arya S, Zuber DM, Sanja KP. Outcomes of women delivering at very advanced maternal age. J. Womens Health. 2018;27(11):1378–1384. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, T., & Xgboost, G. C. A scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (2016).

- 33.Habib, A.-Z. S. B., Tasnim, T., Billah, M. M. A study on coronary disease prediction using boosting-based ensemble machine learning approaches. In Paper presented at the 2019 2nd International Conference on Innovation in Engineering and Technology (ICIET) (2019).

- 34.Saber M, Boulmaiz T, Guermoui M, Abdrado KI, Kantoush SA, Sumi T, et al. Examining LightGBM and CatBoost models for wadi flash flood susceptibility prediction. Geocarto Int. 2021;1:1–26. doi: 10.1080/10106049.2021.1974959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorogush, A. V., Ershov, V., Gulin, A. CatBoost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support [Internet]. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv:1810.11363.

- 36.Chekroud AM, Bondar J, Delgadillo J, Doherty G, Wasil A, Fokkema M, et al. The promise of machine learning in predicting treatment outcomes in psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:154–170. doi: 10.1002/wps.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Vive-Larsen J, Støier M, Olsen TS. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part I: Outcome. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995;76:399–405. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J-Y, Lee D-H, Hwang J-W, Lee K-U. Factors influencing suicidal ideation among lower-income group participating self-sufficiency Program in Gangwon Province, Korea. J. Kor. Contents Assoc. 2016;16:91–101. doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2016.16.12.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park E. Suicide ideation and the related factors among Korean adults by gender. J. Agric. Med. Commun. Health. 2014;39:161–175. doi: 10.5393/JAMCH.2014.39.3.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris PL, Robinson RG, Raphael B, Bishop D. The relationship between the perception of social support and post-stroke depression in hospitalized patients. Psychiatry. 1991;54:306–316. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1991.11024559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi R, Moon H-J, Hwang B-D. The influence of chronic disease on the stress cognition, depression experience and suicide thoughts of the elderly. Kor. Health Serv. Manag. 2010;4:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J. Kor. Neurol. Assoc. 1997;15:300–308. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carod-Artal FJ, Egido JA. Quality of life after stroke: the importance of a good recovery. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):204–214. doi: 10.1159/000200461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim C, Koo K. The effects of physical activities of disabled men with stroke on depression and suicidal ideation. Kahperd. 2017;56:657–664. doi: 10.23949/kjpe.2017.05.56.3.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S-J, Kim H-S, Kim K-S, Baik H-G. The effects of community-based self-help management program by strengthening self-efficacy of post stroke elderly patients. Kor. J. Rehabil. Nurs. 2001;4:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diekstra RF. The epidemiology of suicide and parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr. Scand Suppl. 1993;371:9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb05368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi J, Yang H, Oh H. Store sales prediction using gradient boosting model. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Commun. Eng. 2021;1:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh H-R, Son A-L, Lee Z. Occupational accident prediction modeling and analysis using SHAP. DCS. 2021;22:1115–11123. doi: 10.9728/dcs.2021.22.7.1115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prokhorenkova L, Gusev G, Vorobev A, Dorogush AV, Gulin A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018;31:1. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu Y, Knell G, Brayton RP, Burkhart SO, Jiang X, Shams S. Machine learning to predict sports-related concussion recovery using clinical data. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022;65:101626. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ge X, Sun J, Lu B, Chen Q, Xun W, Jin Y. Classification of oolong tea varieties based on hyperspectral imaging technology and BOSS-LightGBM model. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019;42:e13289. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swalin A. CatBoost vs. Light GBM vs. XGBoost. Towards Data Sci. 2018;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller MP, Tomlinson G, Marrie TJ, Tang P, McGeer A, Low DE, et al. Can routine laboratory tests discriminate between severe acute respiratory syndrome and other causes of community-acquired pneumonia? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:1079–1086. doi: 10.1086/428577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forkmann T, Brähler E, Gauggel S, Glaesmer H. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and related risk factors in the German general population. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012;200:401–405. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31825322cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almhdawi KA, Alazrai A, Kanaan S, Shyyab AA, Oteir AO, Mansour ZM, et al. Post-stroke depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2021;31:1091–1104. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2020.1760893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-stroke depression: a review. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2016;173:221–231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy/ethical restriction, data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.